Abstract

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have been used in cell-based therapy in various disease conditions such as graft-versus-host and heart diseases, osteogenesis imperfecta, and spinal cord injuries, and the results have been encouraging. However, as MSC therapy gains popularity among practitioners and researchers, there have been reports on the adverse effects of MSCs especially in the context of tumour modulation and malignant transformation. These cells have been found to enhance tumour growth and metastasis in some studies and have been related to anticancer-drug resistance in other instances. In addition, various studies have also reported spontaneous malignant transformation of MSCs. The mechanism of the modulatory behaviour and the tumorigenic potential of MSCs, warrant urgent exploration, and the use of MSCs in patients with cancer awaits further evaluation. However, if MSCs truly play a role in tumour modulation, they can also be potential targets of cancer treatment.

1. Introduction

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are a group of heterogeneous multipotent cells which can be isolated from many tissues throughout the body. The discovery of mesenchymal stem cells can be dated back to the 1960s [1]. In recent years, MSCs have gained popularity among stem cell researchers due to their ability to self-renew and differentiate into many different cell types particularly cells of mesodermal origin such as osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes in culture [2–4]. MSCs have also been reported to transdifferentiate into cells of ectodermal [5] and endodermal [6, 7] origins. Besides, MSCs have been applied clinically in patients with severe dilated cardiomyopathy, cartilage disorders, stroke, and autoimmune diseases with very encouraging results [8–11]. However, despite the many potential therapeutic benefits of MSCs, the use of these cells has been reported to bring adverse effects such as an increased recurrence rate of cancer, particularly haematological malignancies. There has been increasing evidence regarding the tumour modulatory effect of MSCs, and it has been shown that MSCs may enhance tumour growth in several studies [12–14]. Besides, MSCs have also been demonstrated to undergo spontaneous malignant transformation in vitro [15]. This review therefore gives an overview of the benefits as well as the harmful effects of MSCs with an emphasis on the clinical implications of the use of these cells.

2. What Are Mesenchymal Stem Cells?

The discovery of MSCs can be credited to the work done by A. J. Friedenstein as early as the 1960s during which he observed that the bone marrow is a source of stem cells for mesenchymal tissues in postnatal life [16]. After harvesting bone marrow samples from the iliac crest, Friedenstein and his coworkers plated the suspension on plastic culture dishes. They observed that upon gradual removal of the haematopoeitic counterpart, there existed a population of plastic-adherent, fibroblast-like cells that could differentiate into chondrocytes and osteoblasts and named them colony-forming unit fibroblasts [1, 17]. They were later renamed mesenchymal stem cells due to their ability to differentiate into cells of mesodermal origin [18].

However, it is worth mentioning that A. J. Friedenstein was not the first to propose the existence of stem cells. Prior to his discovery of MSCs, works of several other scientists have marked important milestones in stem cell research and contributed to our current understanding of the important concepts of stem cells and differentiation. For instance, Alexander A. Maximow was one of the first to introduce the idea of stem cells and their ability to differentiate into other cell types in the context of haematopoiesis. Today, much of our knowledge regarding haematopoiesis originated from Maximow's proposal of the unitarian theory of haematopoiesis in 1906 [19] which he confirmed and updated in his later works and proved that all blood cells originated from a common mother cell [20].

On the other hand, two other scientists, Ernest A. McCulloch and James E. Till were among the first to demonstrate the clonal nature of bone marrow cells through a series of experiments involving bone marrow cell injection into irradiated mice, during which they noticed the spleen of these mice developed lumps or “spleen colonies” in proportion to the number of marrow cells injected. They then linked the observation to the possibility that these colonies originated from a single marrow cell [21, 22].

It is now clear that there are at least two main types of stem cells in the bone marrow—the haemopoietic stem cells and the nonhaematopoietic MSCs. The latter has been shown to be important in the proliferation, differentiation and survival of haematopoietic stem cells in vitro [23]. Traditionally MSCs have been isolated from the bone marrow even though bone marrow MSCs (BM-MSCs) have been shown to represent 0.001% of the whole marrow. Isolation of MSCs from the bone marrow is primarily by adhesion to plastic but these cells can also be concentrated by Percoll gradient centrifugation [24]. While some evidence suggests that BM-MSCs give rise to all mesenchymal lineages in distant tissues [25, 26], these cells have been found to reside in marrow-distant mesenchymal tissues such as skeletal muscles [27] and adipose tissues [28]. Adipose-derived MSCs are found to be similar to BM-MSCs but are easier to produce. These cells have been reported to show a broader therapeutic capacity as compared to BM-MSCs [29]. MSCs have also been located in umbilical cord blood [30], dental tissues [31], synovial fluid [32], palatine tonsil [33], parathyroid gland [34] and fallopian tube [35].

MSCs demonstrate heterogeneity in their morphology. Various terms have been used to describe the appearance of these cells, these include (1) fibroblastoid cells, (2) giant fat cells and blanket cells, (3) spindle shaped, flattened cells, and (4) very small round cells [36]. The morphology of these cells also varies greatly with their seeding density, changing dramatically especially when confluence is reached in cell culture condition. To this end, the relation between the morphology and their cell functions remains unclear.

MSCs express a number of markers phenotypically. However, none of them are specific to these cells. According to the International Society for Cellular Therapy, human MSCs under standard culture conditions must satisfy at least three criteria: (1) they must be plastic-adherent; (2) they must express C105, CD73 and CD90 and not CD45, CD34, CD14, CD11b, CD79 or CD19 and HLA-DR surface molecules by flow cytometry; (3) they must be capable of differentiating into osteoblasts, adipocytes and chondroblasts [37]. However, this set of criteria is not definitive as the expression of cell surface markers can be influenced by extrinsic factors such as those secreted by accessory cells in the initial passages and it is important to note that in vitro expression of cell surface markers may not correlate with in vivo expression [38]. Other markers that are generally accepted include CD44, CD71, Stro-1, and adhesion molecules such as CD 106, CD166, and CD29 [39].

3. The “Angelic” Side of Mesenchymal Stem Cells

The multilineage differentiation potential is the hallmark of MSCs. One of the criteria a cell has to satisfy before being regarded as an MSC would be its ability to differentiate into bone, cartilage, and fat cells [37]. However, studies have shown that MSCs can be differentiated into other cells such as skeletal cells, cardiomyocytes, endothelial, smooth muscle, and neural cells [40]. There have also been several studies on the transdifferentiation of MSCs into pancreatic beta cells [6, 41]. However, the ability of MSCs to differentiate into cells of all three germ layers must be carefully examined as they have been reported to spontaneously express neural markers even in the undifferentiated state [42].

MSCs are immune privileged cells. The fact that MSCs from children can persist in mothers for decades suggests that these cells can escape immune surveillance for a long period of time [43]. The immune phenotype of MSCs is generally described as major histocompatibility (MHC) I positive and MHC II negative. They also lack the costimulatory molecules CD40, CD80, and CD86. Although expressing low levels of MHC I antigens can activate T cells, the absence of costimulatory molecules cannot initiate secondary signals, thus leaving the T cells anergic [44]. Besides, the expression of low levels of MHC I is important in protecting MSCs from natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity. On the other hand, cells that do not express MHC I are targeted and destroyed [45].

Today, a search of clinical trials at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov (a registry of federally and privately supported clinical trials conducted in the United States and around the world) using the key words “mesenchymal stem cells” returns more than a hundred results. The many potential therapeutic uses of MSCs have been related to their multipotent differentiation capacity and unique immunological properties mentioned. However, there are many other reasons why MSCs have gained the interest of researchers in cell-based therapy and tissue engineering. Firstly, MSCs are relatively easy to obtain and maintain compared to other types of stem cells such as embryonic stem cells. BM-MSCs can be readily harvested from the iliac crest, cryopreserved, and expanded many times in vitro to increase the number of transplantable cells. It has been shown that these cells could be extensively expanded in vitro up to 15 population doublings [46] with minor spontaneous differentiation during ex vivo expansion [4]. Other than their ability to differentiate into cells of both mesodermal and nonmesodermal origins, these cells are also immunosuppressive [47]. Besides, MSCs also demonstrate trophic effects via the production of various growth factors and cytokines [48]. Therefore, they have been used for the purposes of cell replacement, repair and regeneration, immunomodulation, and disease modeling.

Many investigations on the feasibility of the clinical use of MSCs have mushroomed in the 1990s. However, Lazarus and colleagues were among the first to inject autologous cultured MSCs into human subjects intravenously and assessed their safety for cell-based therapy. It was demonstrated that the infusion of autologous MSCs into 15 human subjects with haematological malignancies was a safe treatment with complete remission [49]. Subsequently, MSCs were used in many other clinical trials to treat various diseases. For examples, Horwitz et al. had used MSCs in the treatment of children suffering from osteogenesis imperfecta. The study showed engraftment of MSCs and improvement in these children with a reduced frequency of bone breakages [50].

Besides, MSCs have also been used in clinical trials for the treatment of inflammatory and heart diseases, as well as spinal cord injuries. In 2004, Le Blanc et al. reported successful treatment of steroid-refractory grade IV acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD) in a 9-year-old boy [51]. Later in a more recent clinical trial, Le Blanc et al. demonstrated that 6 out of 8 patients with steroid-refractory grade III-IV acute GVHD had complete disappearance of GVHD with the infusion of MSCs [52]. MSCs have also been used in ischaemic cardiomyopathy with promising results [53]. However, the benefits of MSC treatment may be due to paracrine effects of MSCs instead of their capacity to differentiate into cardiomyocytes after injection. It has also been demonstrated that the use of BM-MSCs together with granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factors (GM-CSF) improved acute and subacute spinal cord injuries. However, such improvement was not observed in chronic cases of spinal cord injuries [54].

Of particular interest, adipose tissue-derived MSCs or adipose tissue-derived stem cells, ASDCs have gained much popularity lately. Like MSCs of other origins, ASDCs, have been shown to differentiate into various cell types such as adipogenic, chondrogenic, osteogenic, myogenic cells, and cells that adopt a pancreatic phenotype [55, 56]. The list of potential clinical applications using ADSCs is exhaustive. To name a few, disease conditions in which these cells may be useful or potentially useful include intervertebral disc repair, spinal cord injury, stroke, diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, and wound healing and repair [57]. ADSCs have also been used in several clinical trials. For example, in a phase II clinical trial by Garcia-Olmo et al., expanded ADSCs were used in the treatment of complex perianal fistula either of crytoglandular origin or associated with Crohn's disease. The study concluded that the use of ADSCs in combination with intralesional fibrin glue treatment achieved higher healing rates than using fibrin glue alone [58]. On the other hand, Fang et al. demonstrated that the use of adipose tissue-derived MSCs successfully suppressed hepatic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) in a 43-year-old woman after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation [59] and the successful treatment of two children with acute GVHD due to allogeneic stem cell transplantation from HLA-mismatched unrelated donors [60]. Other published human trials include the use of adipose tissue-derived MSCs in the treatment of traumatic calvarial defect [61] and urinary incontinence [62].

Another type of MSCs, the muscle-derived MSCs (or muscle-derived stem cells, MDSCs), has also gained much attention recently. Although MSCs can be obtained from the bone marrow, the biopsy procedure is more painful and invasive in comparison to skeletal muscle biopsy, which can be done using a small caliber needle under local anesthesia. Therefore, MDSCs are preferred over BM-MSCs in several studies. Some clinical applications or potential applications include the use of MDSCs in musculoskeletal muscle diseases [63] and urinary incontinence [64].

4. The “Demonic” Side of Mesenchymal Stem Cells

Despite the many potential therapeutic benefits of MSCs, these cells have been found to have various adverse effects, especially in the context of their direct and indirect involvement in cancer. Basically, the role of MSCs in cancer can be divided into (1) indirect involvement via the tumour modulatory effect of MSCs and (2) direct involvement via malignant transformation of the MSCs themselves.

4.1. Tumour Modulatory Effect of Mesenchymal Stem Cells

There has been a constant debate on the role of MSCs in tumour modulation. A few studies have supported that MSCs may suppress tumour growth [65–67] while others believe that MSCs may contribute to tumour protection via antiapoptotic effect, tumour progression, metastasis, and drug-resistance of cancer cells [12–14, 68–75]. Although many have demonstrated an antiproliferative effect exerted by MSCs in cancer cells, the set back is that such effect is often accompanied by an antiapoptotic effect. For instance, Ramasamy et al. reported that MSCs inhibited proliferation and apoptosis of tumour cells of haemopoeitic and nonhaemopoeitic origins, which was related to a transient arrest of the tumour cells in G1 phase of the cell cycle in vitro. On the other hand, when tumour cells were injected with MSCs in vivo, the former demonstrated a faster growth when compared to injection of tumour cells alone [12]. The finding was supported by another study by Wei et al. who reported that BM-MSCs from leukaemia patients inhibited growth and apoptosis in serum-deprived K562 cells in vitro [69]. Interestingly, Li et al. reported that human MSCs played a dual role in tumour cell growth in vitro and in vivo. It was found that human MSCs inhibited the proliferation of A549 (lung cancer) and Eca-109 (esophageal cancer) cell lines and caused G1 phase cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in vitro. However, human MSCs were also found to enhance tumour formation and growth in vivo [70]. The tumour protective effect of MSCs was also observed in melanoma A375 cells but was absent in glioblastoma 8MGGBA cells as described by Kucerova et al. [71]. Moreover, MSCs have also been found to protect breast cancer cells through regulatory T cells [14], prevent apoptosis of acute myeloid leukaemia cells by upregulation of antiapoptotic proteins [68], and exert antiapoptotic effect in U266 and H929 melanoma cells mediated by upregulation of survivin [13].

Besides preventing apoptosis and enhancing tumour growth, MSCs have also been related to the promotion of metastasis. Recent evidence suggests that MSCs could migrate towards primary tumours and metastatic sites [76]. Chemokines secreted by MSCs have been shown to enhance the emergence of pulmonary metastases and such secretion has a strong interaction between breast cancer cells and MSCs [72]. In addition, MSCs have also been found to play a role in drug resistance in various cancer cells. Kurtova et al. showed that MSCs protect chronic lymphocytic leukaemic cells from fludarabine-, dexamethosone-, and cyclophosphamide-induced apoptosis [74]. Lin et al. demonstrated that BM-MSCs not only modulated the proliferation of U937 but also the response of U937 cells to daunoblastina and that Bcl-XL apoptosis inhibiting gene may be important in determining the sensitivity of leukaemic cells to treatment [73]. In another study, Vianello et al. showed that BM-MSCs nonselectively protected chronic myeloid leukaemia cells from imatinib-induced apoptosis. It was proposed that the effect was mediated via the CXCR4/CXCL12 axis and that the disruption of this axis could restore the leukaemic cells' sensitivity to imatinib [75].

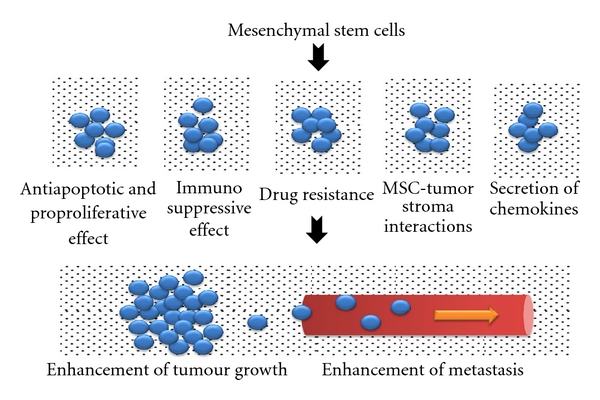

Another tumour enhancing property of MSCs is their ability to suppress the immune system [47]. While this immunosuppressive property of MSCs is good news to patients with immune disorders, it is indeed a double-edged sword, causing harm to those with cancer, as a suppressed immune system may encourage tumour growth. In addition, MSCs have been shown to migrate to the tumour stroma and resulted in enhanced tumour growth and metastasis. For example, Shinagawa et al. reported that MSCs moved toward and interacted with tumour stroma of colon cancer cells. They also differentiated into carcinoma-associated fibroblasts and promoted angiogenesis, tumour growth, migration, invasion, and metastasis [77]. Figure 1 gives a summary of the indirect involvement of MSCs in cancer via their tumour modulatory and other effects.

Figure 1.

Indirect involvement of mesenchymal stem cells in cancer through tumour modulatory and other effects.

4.2. Malignant Transformation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells

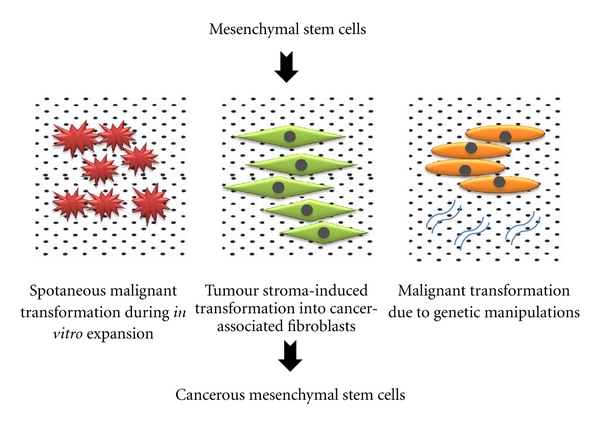

The involvement of MSCs in cancer is not restricted to their ability to enhance proliferation of cancer cells and to cause drug-resistance in various cancer cell types via antiapoptotic and other mechanisms. The MSCs themselves have also been reported to contribute to malignant transformation in several studies. Malignant transformation of MSCs used in cell-based therapy can take place under three conditions: (1) during in vitro expansion of MSCs, (2) malignant transformation as a result of MSC interaction with the tumour stroma, and (3) genetic manipulation of MSCs which turn these cells cancerous (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Direct involvement of mesenchymal stem cells in cancer through malignant transformation.

In order to produce enough MSCs for clinical use, massive in vitro expansion is often necessary. This in turn renders MSCs susceptible to malignant transformation. In 2005, Rubio et al. first reported that adipose tissue-derived MSCs could immortalize and transform spontaneously as a result of long-term in vitro expansion [15]. This was followed by the demonstration of chromosomal instability in long-term cultures of MSCs in later studies [78, 79]. Subsequent molecular characterization of MSC malignant transformation by Rubio et al. demonstrated that these cells were able to bypass senescence by upregulating c-myc and repressing p16 levels. These cells were also shown to bypass cell crisis through acquisition of telomerase activity, InK4a/Arf locus deletion, and Rb hyperphosphorylation. In addition, modulation of mitochondrial metabolism, DNA damage-repair proteins, and cell cycle regulators were also found to play a role in malignant transformation [80]. Besides, it was also reported that alterations in the p21/p53 pathway resulted in MSCs bypassing senescence in vitro with the generation of tumours resembling mesenchymal sarcomas in vivo. The study concluded that a single mutation was insufficient to cause malignant transformation and that such transformation was a result of multiple genetic alterations [81]. In addition, malignant transformation of MSCs has also been demonstrated in vitro by indirect evidence of the derivation of malignant populations from in vitro culture of MSCs, suggesting that MSCs could be the origins of various cancers [82, 83].

The homing effect allows MSCs to migrate towards tumour cells. This migration not only allows MSCs to interact with the tumour stroma and enhance tumour growth as mentioned in Section 4.1, it also leads to malignant transformation of MSCs at the tumour site [77]. Exposure of MSC to local stroma environment of a tumour can lead to differentiation of these cells into cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAF) or tumour-associated fibroblasts (TAF) [84]. This transformation of MSCs into CAF or TAF becomes an important part of the tumour, contributing to fibrovascular network expansion and tumour progression as described by Spaeth et al. [85].

Other than in vitro spontaneous transformation and stroma-induced transformation, a third possible way MSCs can also undergo malignant transformation is by genetic manipulations. Genetic manipulations of MSCs either by viral or nonviral transgene delivery methods have been extensively explored in many studies for the purpose of immortalizing MSCs for long-term cultures and maintenance as well as for the treatment of various diseases such as neurological, blood, vascular, musculoskeletal disorders, and cancer (reviewed by Resier et al., [86]). However, such genetic manipulations are not without risks and disadvantages—either the transgene may be tumorigenic or the insertion of transgenes causes disruption to MSC's genome and lead to malignant transformation. Lessons from spontaneous malignant transformation of MSCs in long-term cultures show that immortalizing MSCs by genetic manipulations may increase the oncogenic potential of these cells as MSCs tend to accumulate chromosomal instability during long-term cultures [79, 82]. Literature on the potential dangers and tumorigenic capacity of genetically manipulated MSCs is scarce and further exploration is necessary.

5. Clinical Implications and Future Directions

In conclusion, the implications of the clinical use of MSCs are at least five-fold.

The use of MSCs for disease treatment in general: the vast number of clinical trials and the abundance of published literature suggest that MSC treatment is feasible. Ongoing translational research may bring new hopes to sufferers of many diseases which can lead to improvement or cure.

The use of MSCs in noncancer patients: there should be long-term followups of patients in this category with respect to the incidence of cancer. While MSCs have been shown to be useful or potentially beneficial in many pathological conditions, care must be taken not to introduce cancer to patients who receive MSC therapy years down the line.

The use of MSCs in cancer patients: further exploration of the use of MSCs in cancer patients, especially those with haematological malignancies and those requiring MSCs for GVHD, is necessary. The benefits of treatment should outweigh the adverse effects that these cells could bring to the patient. This is especially true if the patient is on chemotherapy and the interactions between anticancer-drug-treated cancer cells and MSCs need to be established.

MSCs as vehicles of targeted therapy: if MSCs truly play a role in tumour modulation, the mechanisms by which they exert their modulatory effect should be well elucidated. This includes investigations on the signaling pathways or regulatory proteins involved in the tumour modulatory behaviour of MSCs. On the other hand, such tumour modulatory effect of MSCs can be viewed as a double-edged sword, that is, if they are the cause of the problem, they could also be the solution for being vehicles of targeted delivery of anticancer drugs.

Stricter control and safety measures in the production of MSCs for cell-based therapy: taking into consideration that MSCs can turn malignant as a result of long-term culture and genetic manipulation, there is a need for stricter control in cell handling procedures to minimize the risk of malignant transformation.

Conflict of Interests

The author declares that there are no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge the International Medical University (Malaysia) and Malaysia Toray Science Foundation for funding research that led to the understanding and writing of this paper.

References

- 1.Friedenstein AJ, Piatetzky-Shapiro II, Petrakova KV. Osteogenesis in transplants of bone marrow cells. Journal of Embryology and Experimental Morphology. 1966;16(3):381–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruder SP, Jaiswal N, Haynesworth SE. Growth kinetics, self-renewal, and the osteogenic potential of purified human mesenchymal stem cells during extensive subcultivation and following cryopreservation. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 1997;64(2):278–294. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(199702)64:2<278::aid-jcb11>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haynesworth SE, Goshima J, Goldberg VM, Caplan AI. Characterization of cells with osteogenic potential from human marrow. Bone. 1992;13(1):81–88. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(92)90364-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284(5411):143–147. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kopen GC, Prockop DJ, Phinney DG. Marrow stromal cells migrate throughout forebrain and cerebellum, and they differentiate into astrocytes after injection into neonatal mouse brains. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(19):10711–10716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun Y, Chen L, Hou XG, et al. Differentiation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells from diabetic patients into insulin-producing cells in vitro. Chinese Medical Journal. 2007;120(9):771–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ju S, Teng GJ, Lu H, et al. In vivo differentiation of magnetically labeled mesenchymal stem cells into hepatocytes for cell therapy to repair damaged liver. Investigative Radiology. 2010;45(10):625–633. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181ed55f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta ED, Nayyer N, Chin SP, Cheok CY, Cheong SK. Clinical safety and efficacy of autologous bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell injection for the treatment of severe osteoarthritis. International Journal of Rheumatic Disease. 2010;13, supplement 1:40–43. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chin SP, Poey A, Wong CY, et al. Cryopreserved mesenchymal stromal cell treatment is safe and feasible for severe dilated ischemic cardiomyopathy. Cytotherapy. 2010;12(1):31–37. doi: 10.3109/14653240903313966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bang OY, Lee JS, Lee PH, Lee G. Autologous mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in stroke patients. Annals of Neurology. 2005;58(4):653–654. doi: 10.1002/ana.20612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karussis D, Kassis I, Kurkalli BGS, Slavin S. Immunomodulation and neuroprotection with mesenchymal bone marrow stem cells (MSCs): a proposed treatment for multiple sclerosis and other neuroimmunological/neurodegenerative diseases. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2008;265(1-2):131–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramasamy R, EWF EWF, Sooiro I, Tisato V, Bonnet D, Dazzi F. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit proliferation and apoptosis of tumour cells: impact on in vivo tumour growth. Leukaemia. 2007;21(2):304–310. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang XF, Zhang ZQ, Yao C. Survivin is upregulated in myeloma cell lines cocultured with mesenchymal stem cells. Leukemia Research. 2010;34(10):1325–1329. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel SA, Meyer JR, Greco SJ, Corcoran KE, Bryan R, Rameshwar P. Mesenchymal stem cells protect breast cancer cells through regulatory T cells: role of mesenchymal stem cell-derived TGF-β. Journal of Immunology. 2010;184(10):5885–5894. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rubio D, Garcia-Castro J, Martín MC, et al. Spontaneous human adult stem cell transformation. Cancer Research. 2005;65(8):3035–3039. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Afanasyev BV, Elstner EE, Zander AR. A. J. friedenstein, founder of the mesenchymal stem cell concept. Cellular Therapy and Transplantation. 2009;1(3):35–38. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freidenstein AJ, Deriglasova UF, Kulagina NN, et al. Precursors for fibroblasts in different populations of haematopoietic cells as detected by the in vitro colony assay method. Experimental Haematology. 1974;2:83–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caplan AI. Mesenchymal stem cells. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 1991;9(5):641–650. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100090504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maximow AA. Über experimentelle erzeugung von knochenmarks-gewebe. Anatomischer Anzeiger. 1906;28:24–38. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Novik AA, Ionova TI, Gorodokin G, Smoljaninov A, Afanasyev BV. The maximow 1909 centenary: a reappraisal. Cellular Therapy and Transplantation. 2009;1(3):31–34. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Becker AJ, McCulloch EA, Till JE. Cytological demonstration of the clonal nature of spleen colonies derived from transplanted mouse marrow cells. Nature. 1963;197(4866):452–454. doi: 10.1038/197452a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siminovitch L, McCulloch EA, Till JE. The distribution of colony-forming cells among spleen colonies. Journal of Cellular and Comparative Physiology. 1963;62(3):327–336. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1030620313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dexter TM, Allen TD, Lajtha LG. Conditions controlling the proliferation of haemopoietic stem cells in vitro. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 1977;91(3):335–344. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1040910303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barry FP, Murphy JM. Mesenchymal stem cells: clinical applications and biological characterization. International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 2004;36(4):568–584. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prockop DJ. Marrow stromal cells as stem cells for nonhematopoietic tissues. Science. 1997;276(5309):71–74. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caplan AI. The mesengenic process. Clinics in Plastic Surgery. 1994;21(3):429–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jackson WM, Nesti LJ, Tuan RS. Potential therapeutic applications of muscle-derived mesenchymal stem and progenitor cells. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy. 2010;10(2):505–517. doi: 10.1517/14712591003610606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zuk PA, Zhu M, Mizuno H, et al. Multilineage cells from human adipose tissue: implications for cell-based therapies. Tissue Engineering. 2001;7(2):211–228. doi: 10.1089/107632701300062859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gimble JM, Katz AJ, Bunnell BA. Adipose-derived stem cells for regenerative medicine. Circulation Research. 2007;100(9):1249–1260. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000265074.83288.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee OK, Kuo TK, Chen WM, Lee KD, Hsieh SL, Chen TH. Isolation of multipotent mesenchymal stem cells from umbilical cord blood. Blood. 2004;103(50):1669–1675. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang GT, Gronthos S, Shi S. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from dental tissues vs. those from other sources: their biology and role in regenerative medicine. Journal of Dental Research. 2009;88(9):792–806. doi: 10.1177/0022034509340867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones EA, English A, Henshaw K, et al. Enumeration and phenotypic characterisation of synovial fluid multipotential mesenchymal progenitor cells in inflammatory and degenerative arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2004;50(3):817–827. doi: 10.1002/art.20203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Janjanin S, Djouad F, Shanti RM, et al. Human palatine tonsil: a new potential tissue source of multipotent mesenchymal progenitor cells. Arthritis Research and Therapy. 2008;10(4, article R83) doi: 10.1186/ar2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shih YR, Kuo TK, Yang AH, Lee OK, Lee CH. Isolation and characterization of stem cells from the human parathyroid gland. Cell Proliferation. 2009;42(4):461–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2009.00614.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jazedje T, Perin PM, Czeresnia CE, et al. Human fallopian tube: a new source of multipotent adult mesenchymal stem cells discarded in surgical procedures. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2009;7, article 46 doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-7-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pevsner-Fischer M, Levin S, Zipori D. The origins of mesenchymal stromal cell heterogeneity. Stem Cell Reviews and Reports. 2011;7(3):560–568. doi: 10.1007/s12015-011-9229-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells: the International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8(4):315–317. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gronthos S, Simmons PJ, Graves SE, Robey PG. Integrin-mediated interactions between human bone marrow stromal precursor cells and the extracellular matrix. Bone. 2001;28(2):178–181. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(00)00424-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chamberlain G, Fox J, Ashton B, Middleton J. Concise review: mesenchymal stem cells: their phenotype, differentiation capacity, immunological features, and potential for homing. Stem Cells. 2007;25(11):2739–2749. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang YH, Jahagirdar BN, Reinhardt RL, et al. Pluripotency of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult marrow. Nature. 2002;418(6893):41–49. doi: 10.1038/nature00870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gao F, Wu DQ, Hu YH, Jin GX. Extracellular matrix gel is necessary for in vitro cultivation of insulin producing cells from human umbilical cord blood derived mesenchymal stem cells. Chinese Medical Journal. 2008;121(9):811–818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deng J, Petersen BE, Steindler DA, Jorgensen ML, Laywell ED. Mesenchymal stem cells spontaneously express neural proteins in culture and are neurogenic after transplantation. Stem Cells. 2006;24(4):1054–1064. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O'Donoghue K, Chan J, de la Fuente J, et al. Microchimerism in female bone marrow and bone decades after fetal mesenchymal stem-cell trafficking in pregnancy. Lancet. 2004;364(9429):179–182. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16631-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Javazon EH, Beggs KJ, Flake AW. Mesenchymal stem cells: paradoxes of passaging. Experimental Hematology. 2004;32(5):414–425. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moretta A, Bottino C, Vitale M, et al. Activating receptors and coreceptors involved in human natural killer cell-mediated cytolysis. Annual Review of Immunology. 2001;19:197–223. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Digirolamo CM, Stokes D, Colter D, Phinney DG, Class R, Prockop DJ. Propagation and senescence of human marrow stromal cells in culture: a simple colony-forming assay identifies samples with the greatest potential to propagate and differentiate. British Journal of Haematology. 1999;107(2):275–281. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Le Blanc K, Ringdén O. Immunobiology of human mesenchymal stem cells and future use in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2005;11(5):321–334. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Caplan AI, Dennis JE. Mesenchymal stem cells as trophic mediators. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2006;98(5):1076–1084. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lazarus HM, Haynesworth SE, Gerson SL, Rosenthal NS, Caplan AI. Ex vivo expansion and subsequent infusion of human bone marrow-derived stromal progenitor cells (mesenchymal progenitor cells): implications for therapeutic use. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 1995;16(4):557–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Horwitz EM, Prockop DJ, Lorraine A, et al. Transplantability and therapeutic effects of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. Nature Medicine. 1999;5(3):309–313. doi: 10.1038/6529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Le Blanc K, Rasmusson I, Sundberg B, et al. Treatment of severe acute graft-versus-host disease with third party haploidentical mesenchymal stem cells. Lancet. 2004;363(9419):1439–1441. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Le Blanc K, Frassoni F, Ball L, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of steroid-resistant, severe, acute graft-versus-host disease: a phase II study. The Lancet. 2008;371(9624):1579–1586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60690-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen S, Liu Z, Tian N, et al. Intracoronary transplantation of autologous bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells for ischemic cardiomyopathy due to isolated chronic occluded left anterior descending artery. Journal of Invasive Cardiology. 2006;18(11):552–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yoon SH, Shim YS, Park YH, et al. Complete spinal cord injury treatment using autologous bone marrow cell transplantation and bone marrow stimulation with granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor: phase I/II clinical trial. Stem Cells. 2007;25(8):2066–2073. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hass R, Kasper C, Bohm S, Jacobs R. Different populations and sources of human mesenchymal stem cells (MSC): a comparison of adult and neonatal tissue-derived MSC. Cell Communication and Signaling. 2011;9, article 12 doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-9-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Timper K, Seboek D, Eberhardt M, et al. Human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells differentiate into insulin, somatostatin, and glucagon expressing cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2006;341(4):1135–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zuk PA. Adipose tissue-derived cell: looking back and looking ahead. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2010;21(11):1783–1787. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-07-0589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Garcia-Olmo D, Herreros D, Pascual I, et al. Expanded adipose-derived stem cells for the treatment of complex perianal fistula: a phase II clinical trial. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 2009;52(1):79–86. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181973487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fang B, Song Y, Zhao RC, Han Q, Lin Q. Using human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells as salvage therapy for hepatic graft-versus-host disease resembling acute hepatitis. Transplantation Proceedings. 2007;39(5):1710–1713. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.02.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fang B, Song Y, Lin Q, et al. Human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stromal cells as salvage therapy for treatment of severe refractory acute graft-vs.-host disease in two children. Pediatric Transplantation. 2007;11(7):814–817. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2007.00780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lendeckel S, Jödicke A, Christophis P, et al. Autologous stem cells (adipose) and fibrin glue used to treat widespread traumatic calvarial defects: case report. Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery. 2004;32(6):370–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yamamoto T, Gotoh M, Hattori R, et al. Periurethral injection of autologous adipose-derived stem cells for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence in patients undergoing radical prostatectomy: report of two initial cases. International Journal of Urology. 2010;17(1):75–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2009.02429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gates CB, Karthikeyan T, Fu F, Huard J. Regenerative medicine for the musculoskeletal system based on muscle-derived stem cells. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2008;16(2):68–76. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200802000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Carr LK, Steele D, Steele S, et al. 1-year follow-up of autologous muscle-derived stem cell injection pilot study to treat stress urinary incontinence. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2008;19(6):881–883. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0553-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ohlsson LB, Varas L, Kjellman C, Edvardsen K, Lindvall M. Mesenchymal progenitor cell-mediated inhibition of tumor growth in vivo and in vitro in gelatin matrix. Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 2003;75(3):248–255. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhu Y, Sun Q, Liao L, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells inhibit cancer cell proliferation by secreting DKK-1. Leukemia. 2009;23(5):925–933. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tian K, Yang S, Ren Q, et al. p38 MAPK contributes to the growth inhibition of leukaemic tumor cells mediated by human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 2010;26(6):799–808. doi: 10.1159/000323973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Konopleva M, Konopleva S, Hu W, Zaritskey AY, Afanasiev BV, Andreeff M. Stromal cells prevent apoptosis of AML cells by up-regulation of anti-apoptotic proteins. Leukemia. 2002;16(9):1713–1724. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wei ZH, Chen NY, Guo HX, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells from leukemia patients inhibit growth and apoptosis in serum-deprived K562 cells. Journal of Experimental and Clinical Cancer Research. 2009;28(1, article 141) doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-28-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li L, Tian H, Yue WM, Zhu F, Li SH, Li WJ. Human mesenchymal stem cells play a dual role on tumor cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2011;226(7):1860–1867. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kucerova L, Matuskova M, Hlubinova K, Altanerova V, Altaner C. Tumor cell behaviour modulation by mesenchymal stromal cells. Molecular Cancer. 2010;9, article 129 doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Karnoub AE, Dash AB, Vo AP, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells within tumour stroma promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2007;449(7162):557–563. doi: 10.1038/nature06188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lin YM, Zhang GZ, Leng ZX, et al. Study on the bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells induced drug resistance in the U937 cells and its mechanism. Chinese Medical Journal. 2006;119(11):905–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kurtova AV, Balakrishnan K, Chen R, et al. Diverse marrow stromal cells protect CLL cells from spontaneous and drug-induced apoptosis: development of a reliable and reproducible system to assess stromal cell adhesion-mediated drug resistance. Blood. 2009;114(20):4441–4450. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-233718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vianello F, Villanova F, Tisato V, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells non-selectively protect chronic myeloid leukemia cells from imatinib-induced apoptosis via the CXCR4/CXCL12 axis. Haematologica. 2010;95(7):1081–1089. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.017178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lazennec G, Jorgensen C. Concise review: adult multipotent stromal cells and cancer: risk or benefit? Stem Cells. 2008;26(6):1387–1394. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shinagawa K, Kitadai Y, Tanaka M, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells enhance growth and metastasis of colon cancer. International Journal of Cancer. 2010;127(10):2323–2333. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Miura M, Miura Y, Padilla-Nash HM, et al. Accumulated chromosomal instability in murine bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells leads to malignant transformation. Stem Cells. 2006;24(4):1095–1103. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Takeuchi M, Takeuchi K, Kohara A, et al. Chromosomal instability in human mesenchymal stem cells immortalized with human papilloma virus E6, E7, and hTERT genes. In Vitro Cellular and Developmental Biology—Animal. 2007;43(3-4):129–138. doi: 10.1007/s11626-007-9021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rubio D, Garcia S, Paz MF, et al. Molecular characterization of spontaneous mesenchymal stem cell transformation. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(1, article e1398) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rodriguez R, Rubio R, Masip M, et al. Loss of p53 induces tumorigenesis in p21-deficient mesenchymal stem cells. Neoplasia. 2009;11(4):397–407. doi: 10.1593/neo.81620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liu CF, Chen ZW, Chen ZH, Zhang ZT, Lu Y. Multiple tumor types may originate from bone marrow-derived cells. Neoplasia. 2006;8(9):716–724. doi: 10.1593/neo.06253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tolar J, Nauta AJ, Osborn MJ, et al. Sarcoma derived from cultured mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25(2):371–379. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mishra PJ, Mishra PJ, Humeniuk R, et al. Carcinoma-associated fibroblast-like differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Cancer Research. 2008;68(11):4331–4339. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Spaeth EL, Dembinski JL, Sasser AK, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell transition to tumor-associated fibroblasts contributes to fibrovascular network expansion and tumor progression. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(4, article e4992) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Reiser J, Zhang XY, Hemenway CS, Mondal D, Pradhan L, La Russa VF. Potential of mesenchymal stem cells in gene therapy approaches for inherited and acquired diseases. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy. 2005;5(12):1571–1584. doi: 10.1517/14712598.5.12.1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]