Abstract

As present antibiotics therapy becomes increasingly ineffectual, new technologies are required to identify and develop novel classes of antibacterial agents. An attractive alternative to the classical target-based approach is the use of promoter-inducible reporter assays for high-throughput screening. The wide usage of these assays is, however, limited by the small number of specifically responding promoters that are known at present. This work describes a novel approach for identifying genetic regulators that are suitable for the design of pathway-specific assays. The basis for the proposed strategy is a large set of antibiotics-triggered expression profiles (“Reference Compendium”). Pattern recognition algorithms applied to the expression data pinpoint the relevant transcription-factor-binding sites in whole-genome sequences. Using this technique, we constructed a fatty-acid-pathway-specific reporter assay that is based on a novel stress-inducible promoter. In a proof-of-principle experiment, this assay was shown to enable screening for new small-molecule inhibitors of bacterial growth.

The ever-increasing prevalence of infections caused by multidrug-resistant bacteria represent a growing threat to public health. Presently available antibiotics are becoming increasingly ineffective, resulting in an expected significant growth of the number of untreatable infections within the coming years (Gray and Keck 1999). Because conventional antibiotics are known to interfere with only a small number of targets, there is little doubt that novel structural classes of antibiotics are urgently needed (Breithaupt 1999).

There are two major complementary strategies for finding novel drug candidates: the “target-based” screening approach and the “whole-cell” screening approach (Rosamond and Allsop 2000). The target-based approach aims to identify inhibitors of a specific biochemical reaction or intermolecular interaction. It is considered to be very sensitive and relatively easy to implement from a technological perspective. Turning the in vitro inhibitor into an antibacterial drug is very often, however, complicated by penetration, efflux, and metabolic issues. A further limitation is the underlying one-compound-one-target concept, which makes it very difficult to find a drug that works on multiple targets at the same time (so-called multimodal inhibitors, such as penicillin, for instance; Goffin and Ghuysen 1998). In contrast, the whole-cell screening approach uses bacterial cells to identify compounds that inhibit bacterial growth. This approach has the advantage that it selects by definition only compounds with established antibacterial properties. However, several issues make this historically successful approach difficult to pursue. The targeted pathway is typically unknown, resulting in a lack of a rational basis for compound optimization. The most difficult obstacle when following this strategy is that a significant proportion of the active compounds are generally toxic and cannot be distinguished from specific inhibitors.

Whole-cell assays that use genetically modified strains have recently been recognized as a very attractive alternative to avoid these difficulties. Besides the construction of target-gene under-expression systems (Ji et al. 2001; DeVito et al. 2002; Forsyth et al. 2002), a very promising strategy is presented by so-called promoter-inducible assays. These assay systems are based on cells that carry reporters such as β-galactosidase or luciferase genes fused to promoters that specifically respond to certain types of antibiotic stress (Bianchi and Baneyx 1999; Alksne et al. 2000; Shapiro and Baneyx 2002; Sun et al. 2002). Those engineered strains are especially convenient for high-throughput assay systems because of the short incubation times and the low (sublethal) compound concentrations they require. The selective induction of the reporter fusion indicates that a compound is perturbing the pathway of interest at some point, even if the actually inhibited targets are not known. The main advantage of these reporter assays is that they provide a way to systematically screen chemical libraries for compounds with a defined mechanism-of-action (MOA), that is, compounds interfering with a defined pathway. However, the major bottlenecks in designing these pathway-specific reporter strains are the limited number of suitable promoters presently known and the lack of a deeper understanding of the nature of the promoters to be used (Fischer 2001; Freiberg and Brunner 2002). A strategy to identify suitable marker promoters requires a thorough understanding of the transcription regulation mechanisms of the pathways to be screened.

Here, we report a novel strategy to systematically identify suitable marker promoters whose induction indicates distinct cellular stress types. The starting point is a “Reference Compendium,” a large set of microarray experiments that represent expression profiles triggered by classical antibiotics. The profiles used to build the Reference Compendium correspond to a large number of cellular responses to a variety of compounds with different MOAs, thus affecting a broad range of different pathways. The analysis of transcript abundance correlations across all Reference Compendium experiments for a given pathway enables an in silico reconstruction of the regulon that composes the pathway of interest. The availability of whole genome sequences, together with sequence pattern recognition algorithms, enables the identification of conserved putative transcription-factor-binding sites (TFBS) in the genomic upstream DNA sequences of the coregulated genes. Using a random genome model, the specificity of the regulation mechanisms of the pathway of interest can be assessed. Promoters harboring pathway-specific TFBS are considered as a suitable means to construct MOA-specific reporter assays.

To exemplify the proposed approach, we present an analysis of the bacterial type II fatty acid biosynthesis pathway (in the following referred to as FAS). Here, we focus on the FAS pathway, because (1) it is absolutely necessary for bacterial viability; (2) it is broadly conserved across many clinically relevant pathogens; (3) the corresponding human fatty acid biosynthesis pathway is a distinct “type I” system, significantly different from the FAS type II system; and (4) several antibiotic compounds working on enzymes involved in the type II FAS pathway, such as isoniazid, triclosan, or cerulenin, are already known (Payne et al. 2001; Schujman et al. 2001). It is believed that the FAS pathway is so far mostly unexploited, thus providing excellent opportunities to identify novel antibiotic lead compounds (Campbell and Cronan Jr. 2001; Heath et al. 2001).

By applying our proposed strategy to Bacillus subtilis, we were able to identify a novel, as yet uncharacterized regulatory element that seems to be responsible for the regulation of the FAS pathway. This putative transcription-factor-binding site pinpointed stress-inducible promoters that are eligible for the construction of FAS-pathway-specific B. subtilis reporter strains. As a proof of principle, a FAS-specific reporter assay was constructed using one of the in silico identified promoters. Testing several diverse antibiotics with this assay resulted in the selective identification of FAS inhibitors. This case study demonstrates how pathway-specific stress promoters can be systematically identified, thereby overcoming the bottleneck in constructing MOA-specific assay systems that facilitate high-throughput screening for novel small-molecule inhibitors.

RESULTS

Expression Profile Reference Compendium

A whole-genome, two-channel microarray technology was used to monitor the transcriptional response of virtually all ∼4100 B. subtilis genes (Kunst et al. 1997). This technology enables the parallel measurement of the induction or repression of all genes when exposing cultures to substances with antibacterial potential (Wilson et al. 1999; Gmuender et al. 2001; Whiteley et al. 2001; Freiberg and Brunner 2002). Here, a set of eight well-investigated antibiotics was used, belonging to four different broad MOA classes, as listed in Table 1 (Chopra et al. 2002). Moreover, profiles representing the effect of cationic peptide polymyxin B and the polyether monensin were included in the Reference Compendium (Table 1). Because these antibiotics are known to cause broad effects on the bacterial cell membrane, we call them “unspecifically” acting antibiotics (Scott et al. 1999; Riddell 2002). Bacterial cultures were treated with two different concentrations for each compound, and mRNA was harvested after 10 and 40 min exposure time (see Methods for further details). The biological reproducibility of the applied methodology was representatively examined. Three different cultures were grown under cerulenin stress (3 μg/mL) for 40 min, equally processed, and each cDNA was hybridized on three microarrays. Less than 0.5% of the hybridization signals were scattered by more than a factor of 2 (average culture–culture correlation of the fluorescence ratios R = 0.932).

Table 1.

Reference Compendium Compounds and Their Underlying Mechanisms of Action (MOA)

| Compound | MOA | MIC (μg/mL) | Applied concentrations (μg/mL) (L; H) | Treatment times (min) (1; 2) | No. of replicates (condition L1/L2/H1/H2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Novobiocin | DNA synthesis | 2.000 | 0.40; 4.00 | 10; 40 | 3/3/3/3 |

| Trimethoprim | DNA synthesis | 0.500 | 0.05; 0.50 | 10; 40 | 3/2/3/3 |

| Actinonin | Translation | 16.000 | 3.20; 32.00 | 10; 40 | 3/3/3/3 |

| Azithromycin | Translation | 1.000 | 0.20; 2.00 | 10; 40 | 3/3/3/3 |

| Vancomycin | Cell wall synthesis | 0.250 | 0.05; 0.50 | 10; 40 | 3/3/3/3 |

| Methicillin | Cell wall synthesis | 0.125 | 0.13; 0.25 | 10; 40 | 3/3/3/3 |

| Triclosan | Fatty acid synthesis | 1.000 | 0.10; 1.00 | 10; 40 | 3/0/3/2 |

| Cerulenin | Fatty acid synthesis | 16.000 | 3.20; 32.00 | 10; 40 | 2/11/0/3 |

| Polymyxin B | Unspecific | 16.000 | 1.60; 16.00 | 10; 40 | 3/2/2/3 |

| Monensin | Unspecific | 4.300 | 0.43; 4.30 | 10; 40 | 2/3/3/3 |

Overall, 10 different compounds were used in this study, eight antibiotics belonging to four major MOA classes and two “unspecific” compounds acting on the cell membrane (see text). The last column provides the number of replicate experiments for the combinations of high versus low dosage together with short versus long time exposure (low-early/low-late/high-early/high-late; see Methods).

To account for the hybridization variability for all antibiotics tested, each cDNA sample was split and hybridized separately to three different microarrays (“technology replicates,” average hybridization–hybridization correlation of the fluorescence ratios R = 0.983). Only experiments that passed the strict quality criteria were used for the subsequent biostatistical analysis. Finally, 116 individual hybridization experiments were included in the Reference Compendium of diverse stress states of B. subtilis.

Genome Context Analysis of Transcript Correlations

We focused on the regulation of the B. subtilis fatty acid biosynthesis pathway; therefore, a well-characterized representative of the FAS pathway, the gene yjaX (also called fabHA), was chosen as the reference gene. This gene encodes the 3-oxoacyl-acyl-carrier protein synthase III (Choi et al. 2000), representing a central enzyme of the FAS pathway. The correlation coefficients RyjaX were calculated for all genes with respect to the yjaX expression activity pattern across all Compendium experiments. Table 2 lists the 20 most correlated genes (the full list of correlations is provided in Supplemental Table S1 available online at www.genome.org). Most of the functionally characterized genes in Table 2 are known to be involved in the FAS system (Heath et al. 2001; Payne et al. 2001). These findings confirmed prior knowledge about the FAS pathway, corroborating the idea that coregulation of genes is often related to functional coupling. About one-third of the highly correlated genes are not, or are only poorly, functionally characterized thus far. It is tempting to speculate about the role of these genes in the B. subtilis FAS. However, one should be aware that the conclusions drawn in this work are not dependent on this assumption.

Table 2.

Genes That Are Most Correlated With yjaX's Expression Pattern Across All 116 Experiments

| Genea | Gene descriptionb | Pathwayc | RyjaXd | Se | Locationf | Operong |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| yjaX | fabHA: 3-oxoacyl-acyl-carrier protein synthase III A | FAS | 1 | 21.2 | — 70 | 1 |

| yjaY | fabF: 3-oxoacyl-acyl-carrier protein synthase II | FAS | 0.8481 | 21.2 | 1 | |

| yhfB | fabHB: 3-oxoacyl-acyl-carrier protein synthase III B | FAS | 0.7798 | 17.2 | — 51 | 2* |

| gltT | H+/Na+-glutamate symport protein | 0.7405 | 3 | |||

| fabD | Malonyl CoA-acyl carrier protein transacylase | FAS | 0.7253 | 16.7 | 4 | |

| accB | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (biotin carboxyl carrier subunit) | FAS | 0.7147 | 5 | ||

| yhdO | plsC: 1-acylglycerol-3-phosphate O-acyltransferase | PLS | 0.7007 | 15.5 | — 72 | 6* |

| ylpC | Unknown; similar to unknown proteins | 0.6731 | 16.7 | — 34 | 4 | |

| fabG | β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein reductase | FAS | 0.6624 | 16.7 | 4 | |

| yxlF | Similar to ABC transporter (ATP-binding protein) | 0.6601 | 7* | |||

| panD | Aspartate 1-decarboxylase | PAN | 0.6412 | 8 | ||

| yjbW | fabl: enoyl-acyl-carrier protein reductase | FAS | 0.6360 | 17.9 | — 17 | 9* |

| panB | Ketopantoate hydroxymethyltransferase | PAN | 0.6356 | 8 | ||

| ylmB | Similar to acetylornithine deacetylase | 0.6318 | 10 | |||

| plsX | Involved in fatty acid/phospholipid synthesis | PLS | 0.6279 | 16.7 | 4 | |

| yraK | Predicted hydrolase/acyl-transferase | 0.6277 | ||||

| azlD | Branched-chain amino acid transport | 0.6271 | ||||

| ykoK | Similar to Mg2+ transporter | 0.6224 | ||||

| yobL | Unknown; similar to unknown proteins from B. subtilis | 0.6214 | ||||

| yrhI | Unknown; similar to transcriptional regulator (TetR/AcrR family) | 0.6188 |

The commonly used gene name

A description of the gene product's function

The genes already known to be involved in type II FAS and connected pathways (PAN, pantothenate biosynthesis; PLS, phospholipid biosynthesis)

The correlation coefficient RyjaX

The similarity score S for possible transcription-factor-binding sites in upstream sequences of the coregulated transcriptional units (averages of the scores S arising from matches with the palindromic motif on both DNA strands, see Methods), bold numbers indicating the operon head genes

The genomic location of the those motifs, counted in base pairs upstream from the translation-start codon of the operon head gene

The references to corresponding transcription units, with same numbers indicating the same operons (see text). A superscript star indicates isolated genes, without neighboring genes being coexpressed

Identification of Coregulated Operons Involved in Fatty Acid Biosynthesis

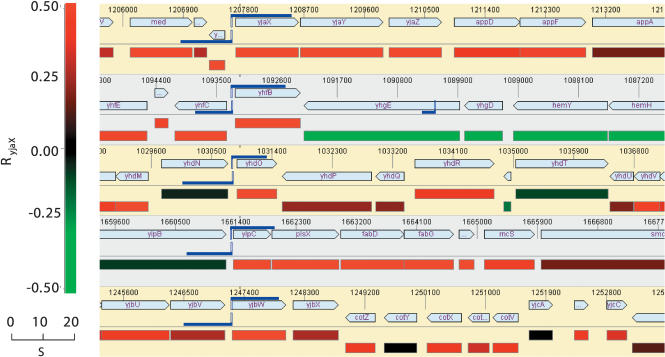

Next, we sought to determine the regulatory genomic regions that control the responsive genes. If a gene lies within an operon generating polycistronic transcripts, its promoter can lie several genes upstream (McGuire et al. 2000). Hence, it is essential to first determine possible operon structures among the most yjaX-correlated genes. To identify the “operon heads,” the yjaX-correlated genes were mapped onto the B. subtilis genome. Figure 1 shows different regions of the B. subtilis genome, with the color-coded expression correlations RyjaX shown underneath each segment. Highly correlated genes (red rectangles), located next to each other and transcribed in the same direction, most likely represent operon structures (Sabatti et al. 2002). In summary, the following 10 most yjaX-correlated transcriptional units were identified: (1) yjaX (=fabHA)–yjaY (=fabF)–yjaZ; (2) yhfB (=fabHB); (3) gltT; (4) ylpC–plsX–fabD–fabG–acpA; (5) accB–accC–yqhY; (6) yhdO (=plsC); (7) yxlF; (8) panB–panC-panD; (9) yjbW (=fabI); (10) ylmB. The genes and operons (1) through (10) are sorted in descending order with respect to their overall yjaX correlation (see Table 2). Almost all known enzymes that make up the FAS pathway, as well as genes from connected pathways such as the pantothenate biosynthesis (necessary for the production of functional acyl-carrier protein) and the phospholipid biosynthesis (using fatty acids), have been identified. In addition, several genes are organized in coexpressed transcriptional units whose roles in FAS and lipid biosynthesis await a more detailed functional characterization.

Figure 1.

Genome expression correlation map of Bacillus subtilis. Five different regions of the complete genome sequence are displayed, together with color-coded mRNA expression correlations RyjaX (see the color scale; correlations R > 0.5 are displayed in the brightest red and green, respectively). Moreover, the locations of the conserved putative TFBS are shown (blue double-flags). The flag length indicates the score S reflecting the similarity to the TFBS consensus (see text), and the vertical blue lines indicate the position of the 21-bp-wide motif on the genome sequence (Phylosopher 4.0; Genedata). Note the appropriate locations of these motifs with respect to the operon head genes, consistent with their possible function as cis-regulatory elements, as well as the clearly correlated expression behavior of the genes located downstream, some of them representing larger operon structures (see Methods).

Searching Genomic Upstream Regions for Genetic Regulators

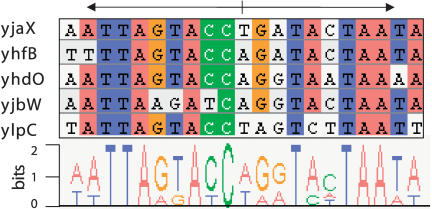

One of the most commonly used mechanisms in nature to control the expression activity of genes and operons is through DNA binding of transcription factors (TF). We have undertaken a computational search for such cis-regulatory elements that coordinate the transcriptional activity of the coexpressed FAS relevant genes. In most cases, the TF bind to regulatory DNA motifs located in the noncoding DNA upstream regions of the regulated genes (Mironov et al. 1999; McCue et al. 2001). In the following, we therefore focus on the upstream regions from -400 bp to the translation-start codon of the first genes in the predicted transcriptional units. To capture only primary regulatory effects that are based on the direct effect of only one (or very few) regulatory proteins, the upstream regions of only the top 10 transcriptional units were searched for regulatory motifs. For this, a stochastic optimization algorithm was used to identify conserved DNA motifs (see Methods). An alignment of the most significantly conserved motifs that were identified is shown in Figure 2. The consensus motif WTTARKAYCWRRTMHTAAW (with W = A or T, R = G or A, K = T or G, Y = C or T, M = A or C, and H = C or A or T) representing a putative TFBS is found upstream of yjaX, yhfB, yhdO, yjbW, and ylpC, but it is lacking for the other transcriptional units. The clear palindromic symmetry of the motif indicates that it is a binding site for a dimeric transcription factor (Huffman and Brennan 2002). In this context, it has to be emphasized that the (annotation-based) knowledge of all fatty acid biosynthesis relevant genes in B. subtilis, of which all upstream regions have also been compared, did not enable us to identify the putative TFBS motif (see Methods). Only the expression data revealed the genes that are transcription-correlated with yjaX, and allowed the reliable prediction of the corresponding transcription control regions. Thus, the results of this work are critically dependent on the expression profiling data that were necessary to restrict the number of candidate regulatory regions.

Figure 2.

Alignment of the conserved putative transcription factor binding sites present in the genomic upstream sequences of five yjaX-coregulated transcriptional units. Nucleotide-specific coloring of the aligned residues was applied for sites with >80% conservation. Underneath, a sequence logo representation displays the information content per aligned site. Note the clear palindromic symmetry of the motif, indicating that a dimeric transcription factor binds to these DNA sites, which implies a role as cis-acting recognition motifs for the regulation of the Bacillus subtilis type II fatty acid biosynthesis pathway.

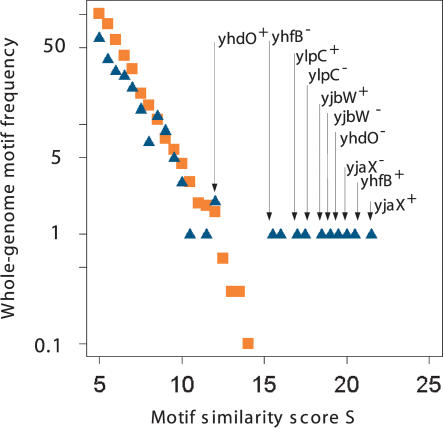

Assessing the Genome-Wide TFBS Specificity

To confirm that we have, indeed, identified a pathway-specific TFBS, a position weight matrix model of the conserved regulatory sequences was used to search the B. subtilis whole-genome sequence for additional instances of the TFBS motif. For this, a pattern search algorithm was used that identifies TFBS-similar motifs that possibly act as cis-regulatory elements. A comparison of the similarity score distribution of the motifs found in the B. subtilis whole-genome sequence as well as the results obtained from a random genome analysis are shown in Figure 3. The results readily suggest that a similarity score threshold of approximately S ≥ 12 is suitable to separate random from nonrandom motif occurrences. Motifs exceeding this similarity cutoff score can be considered to occur not merely by chance, thus indicating that such sites have functional consequences in representing biologically relevant TFBS. Table 2 provides information on which of the most yjaX-correlated genes are equipped with such a putative regulator, together with information about the exact location of the predicted binding sites. Figure 1 provides a graphical view of the five most significant TFBS hits. Remarkably, only the genes of the central enzymes of the FAS pathway are equipped with significant TFBS motifs. These findings corroborate our notion that the identified TFBS are highly specific for the FAS path-way.

Figure 3.

Whole-genome transcription-factor-binding site specificity. The position weight matrix of the TFBS motifs (see Fig. 2) has been used to search for similar motifs in the Bacillus subtilis whole-genome sequence. The plot displays the similarity score distribution (blue triangles), together with a score distribution derived from a random genome model (orange squares). Whereas the random hits obey a clear exponentially decaying distribution function even for higher scores, the B. subtilis genome-based results bend off at ∼S > 10. The genome-based results appear to be systematically underrepresented for lower scores, indicating a high genome-wide specificity of the identified TFBS motif. The arrows indicate the genes located downstream of the high scoring hits. Note that because of the palindromic nature of the motif, each gene appears twice, once for each DNA strand; (superscript +) orientation in transcription direction; (superscript -) opposite direction.

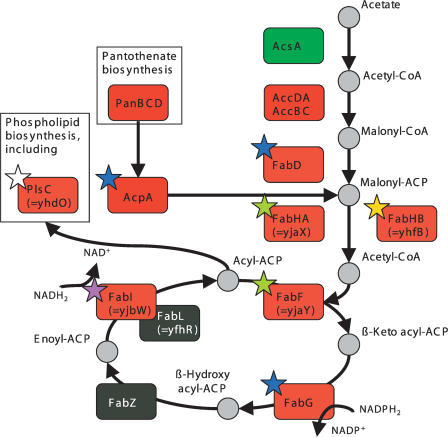

Pathway Mapping

To elucidate the parts of the pathway that may be susceptible to perturbations induced in chemical screening, it is extremely useful to analyze the relationship of the biochemical reactions, the transcription control mechanisms, and the actual mRNA correlations in the context of the pathway that is under investigation. Figure 4 shows the B. subtilis FAS and connected pathways, including the pantothenate and phospholipid biosynthesis, together with the yjaX-mRNA correlations and the identified TFBS. Clearly, the central part of the FAS pathway is made up of enzymes, most of which are encoded by only a few transcriptional units that all possess a common upstream TFBS. Only a few genes (panBCD, accDA, and accBC) are coexpressed, but lack the binding motif in their upstream regions, indicating secondary regulation effects. Remarkably, some genes known to play an important role in FAS lack an upstream TFBS motif, such as the genes encoding the acetyl-CoA synthetase AcsA, the second enoyl-ACP reductase FabL and the β-hydroxyacyl-ACP dehydratase FabZ, indicating that other transcriptional or posttranscriptional control mechanisms may play a role. Taken together, these findings indicate that the nature of the acsA, fabL, and fabZ promoters is distinct from the other FAS-relevant promoters. This reasoning suggests that these promoters are most likely not eligible for FAS-specific assays.

Figure 4.

The type II fatty acid biosynthesis pathway of Bacillus subtilis with mapped transcript correlations RyjaX (same color scale as Fig. 1). The stars indicate the genes that are apparently controlled by the transcription-factor-binding site. The coloring of the stars reflects the different transcription units: (green) operon (1), (yellow) (2), (blue) (4), (white) (6), and (violet) (9); see text.

Cellular Assay Development and HTS Results

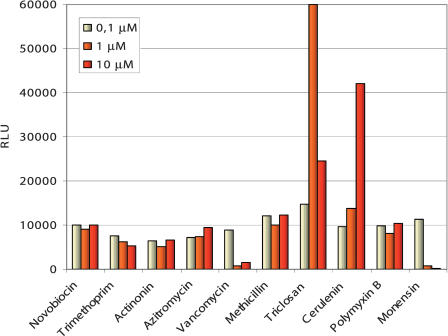

The actual transcription factor could be identified using classical affinity assays (McCue et al. 2001) based on cell extracts. However, it should be emphasized that from a drug discovery standpoint, knowledge of the regulatory protein is not required. A reporter assay based on one of the identified FAS promoters that harbor a TFBS should represent a suitable measurement device for the effective cellular concentration of the (unknown) TF. The previously discussed evidence, such as mRNA correlations, conserved nonrandom upstream motifs, as well as the motif's genome-wide specificity indicate that the identified promoters are susceptible to FAS-specific stress conditions. Thus, our reasoning was that the transcriptional activity of promoters holding the identified TFBS could be used as a reliable indicator for FAS-pathway-specific perturbations. To test this hypothesis, we constructed a reporter strain based on one of the five promoters harboring a significant representative of the TFBS. For this, we fused the firefly luciferase gene with the promoter of yhfB (=fabHB). As shown in Figure 5, this assay enabled us to measure promoter induction that is highly selective for the commonly known FAS inhibitors, such as triclosan and cerulenin. Non-FAS inhibitors such as DNA replication, protein biosynthesis, and cell wall biosynthesis inhibitors did not induce the reporter system.

Figure 5.

Compound MOA specificity of the fatty acid biosynthesis-specific reporter assay. Antibiotic compounds with diverse MOAs were tested for induction of luminescence in Bacillus subtilis 168 carrying the reporter plasmid pNS2. This plasmid carries the upstream region of the gene yhfB (=fabHB), including the identified FAS-specific transcription-factor-binding site (see text). Whereas known FAS inhibitors such as triclosan and cerulenin cause reporter induction, antibiotics with a different MOA do not induce the reporter, corroborating the pathway specificity of the assay system at hand. Note that the 10 μM concentration of triclosan lies above the MIC for this compound, indicating that the reduced signal at this concentration is caused by a reduced number of viable cells.

The assay was applied in high-throughput screening of large compound libraries. The standard deviation of the noninduced and the 1μM triclosan-induced reference signal was below 12%. The data were normalized with respect to the noninduced signal. The cutoff limits for hit identification were set based on the distribution of normalized signals (190% and 280% of the noninduced signals in case of the primary screen and the secondary hit confirmation screen, respectively). Among the ∼900,000 compounds tested, 573 hits could be identified (hit rate of 0.06%). Among 60 confirmed hits, four novel chemically interesting types of hit clusters were further evaluated (data to be published elsewhere). Three hit clusters showed selective inhibition of [3H]acetate incorporation into phospholipids in Staphylococcus aureus between 35% and 70% at 100 μM concentrations, but no inhibition of incorporation of other metabolites measuring DNA, RNA, protein, and cell wall biosynthesis. The hit compounds showed reduced growth rates of S. aureus and B. subtilis, but did not exhibit MICs up to 100 μM (G. Schiffer, pers. comm.).

These data indicate that the FAS inhibitors identified by the B. subtilis promoter induction assay also target the FAS pathway in related pathogens such as S. aureus, although their inhibitory potency still needs to be improved in order to reach antibacterial activity. Our findings corroborate the notion that small-molecule inhibitors of defined pathways can, in fact, be systematically identified by monitoring the activity of appropriately selected stress-inducible promoters.

DISCUSSION

FAS Pathway as Proof of Concept

The aim of this study was to exemplify a systematic approach for identifying novel regulatory elements that can be used for constructing new types of pathway-specific assay systems for antibacterial discovery. In this study, we present a data analysis strategy applied to a Reference Compendium of expression profiling experiments. This Reference Compendium database holds a large set of mRNA profiling data, representing the transcriptional responses to a wide variety of different stress conditions. Our study focused on B. subtilis, a preferred model organism that is phylogenetically related to major clinically relevant pathogens such as S. aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Based on this model organism, we showed how stress-specific promoters could be identified using sequence pattern recognition algorithms. To provide a proof of concept, we focused on the essential bacterial fatty acid biosynthesis pathway. The suggested approach enabled us to identify a suitable stress-inducible promoter that was used to construct an engineered reporter strain. Using a promoter-inducible assay system based on this strain, we were able to show that this assay could be used to identify the two known FAS inhibitors, cerulenin and triclosan, which inhibit the β-oxoacyl-ACP synthases of the FabF class and the enoyl-ACP reductase FabI in B. subtilis, respectively (Kauppinen et al. 1988; Heath et al. 1998; Moche et al. 1999). In addition, we found novel compounds that selectively inhibit fatty acid biosynthesis in high-throughput screening of a compound library. The dependence of most FAS genes on the stress-inducible promoter indicates that such compounds could also target FAS enzymes other than FabF and FabI. It remains to be seen whether inhibition of enzymes encoded by noncoregulated genes such as fabZ and fabL can also be detected by this reporter assay.

Because FAS genes are broadly conserved among bacteria, B. subtilis-specific FAS inhibitors are generally considered relevant for pathogens of pharmaceutical interest (Campbell and Cronan Jr. 2001; Heath et al. 2001; Payne et al. 2001). In this study, the identified screening hits were shown to selectively inhibit fatty acid/phospholipid biosynthesis in the pathogen S. aureus. Note that although cerulenin and triclosan are antibacterials targeting important pathogens such as staphylococci, cerulenin is also effective against mammalian FAS. Moreover, the triclosan target FabI is not the only enoyl-ACP reductase known in bacteria: S. pneumoniae, which does not harbor fabI, and Enterococcus faecalis, which even carries the fabI allele, possess an analogous enzyme FabK, which is completely refractory to triclosan action (Payne et al. 2002). Nevertheless, many FAS enzymes are considered to represent important broad-spectrum targets; such as the acyl group condensing enzymes of the FabF and FabH families.

It is well known that whole-cell-based reporter assays also have limitations. An essential prerequisite for any effective compound is that it penetrates the bacterial cell to have a measurable effect. Another difficulty is the typically limited effective compound concentration window that enables induction of a reporter system. Compounds that are too potent will reduce or even switch off the reporter signal (due to killing reporter cells), whereas very weak inhibitors will not induce a significant signal. Therefore, screening at different compound concentrations and time points for signal detection is optimal to increase the chances for FAS inhibitor identification. In the case of our FAS inhibitor reporter assay, sublethal inhibitors were already identified at a screening concentration of 10 μM, causing a twofold to threefold signal induction. Typically, such compounds will require several chemical optimization cycles to result in antibacterial drug candidates.

General Concept

A prerequisite for the proposed approach to identify novel regulatory elements for the development of pathway screens is a set of comprehensive mRNA profiles (Reference Compendium). These should encompass a large collection of diverse mRNA profiles that represent different cellular stress states. The expression profiles need to be of sufficient diversity; that is, the pathways of interest need to be deregulated in at least some experiments. The establishment of extensive Reference Compendia for a variety of pathogens will thus be a first step toward a better characterization of stress-specific promoters. A second necessary precondition is the availability of the complete genome sequence of the bacterium of interest.

A very important point is that the proposed strategy can be applied to virtually any essential functional system of a bacterial cell. For instance, we identified a novel common regulatory site for a group of predominantly unknown genes in B. subtilis, which are strongly and selectively induced by cell wall biosynthesis inhibitors such as β-lactams and glycopeptides (data not shown). These results show that our strategy can be readily applied to the “classical” antibacterial target pathways (protein biosynthesis, cell envelope biogenesis, transcription, or DNA synthesis), but also that new areas of biology are equally amenable. Of particular interest are the pathways that have been recognized to harbor promising, but as yet unexploited targets, such as isoprenoid biosynthesis, coenzyme metabolism, cell division, or signal transduction systems (Gerdes et al. 2002; McDevitt et al. 2002).

In such cases, where no promoter-inducing reference compounds exist, reducing the expression of appropriate target genes by genetic manipulation can mimic target inhibition by chemical entities and trigger promoter induction. A proof-of-concept example is the down-regulation of the cerulenin target FabF in B. subtilis, which leads to the induction of FAS promoters as cerulenin does (data not shown). Also, the opportunity to revisit targets that have failed to provide promising lead compounds in previous target-based screening projects becomes feasible.

So far, the bottleneck in the design of pathway-specific reporter assays was caused by the lack of knowledge about suitable promoters that respond specifically to defined antibiotic stress types. However, the strategy outlined in this work represents a systematic approach to overcome this hurdle. Thus, inducible-promoter assay technologies are likely to become a widely used tool for rational drug design campaigns aiming at the identification and development of novel antibiotic agents.

METHODS

Transcription Profiling Experiments

Cultures of B. subtilis 168 were grown in Belitzki minimal medium (Stulke et al. 1993) to O.D.600 = 0.4 at 37°C. After removal of an aliquot (time point 0, untreated sample), the remaining culture was subjected to compound stress by addition of antibiotics and incubated for a further 10 and 40 min to obtain aliquots of treated cells (time points 1 and 2). Each compound was examined in two concentrations [(L) low; (H) high], where concentration L represented 1/10 of concentration H. Twofold MIC was chosen as the high compound concentration. In the case that the applied concentration already caused >25% growth reduction compared with the control at time point 2, the maximal concentration was reduced to onefold MIC (Table 1). The culture aliquots were directly poured into 0.5 volumes of ice-cold sodium azide buffer consisting of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM NaN3, and 5 mM MgCl2, and were harvested for 5 min at 8.000g and 4°C. The resulting pellets were shock-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C. RNA was isolated according to standard protocols using QIAGEN RNeasy Midi Columns (QIAGEN). Fluorescence-labeled cDNA was prepared from 25 μg of total RNA by reverse transcription with a specific primer set representing all 4100 open reading frames of B. subtilis (Eurogentec) using Super-Script II (Life Technologies), 100 pmoles of primer set and nucleotides at the final concentration of 0.27 mM dATP/dGTP/dTTP, 0.08 mM dCTP, and 0.04 mM Cy3-dCTP or Cy5-dCTP (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), respectively. For each hybridization, 2.5 μL of Cy5-labeled cDNA obtained from untreated samples was mixed with 2.5 μL of Cy3-labeled cDNA obtained from treated samples. The labeled material was added to 20 μL of hybridization solution (Eurogentec) and hybridized to B. subtilis whole-genome arrays (Eurogentec). After incubation for 4 h at 37°C, slides were washed for 5 min at room temperature in 0.1× SSC, 0.1% SDS, 0.1× SSC, and distilled water, respectively. The fluorescence intensities of the two dyes were detected via the Axon GenePix 4000A confocal laser scanner using the image analysis software GenePix Pro (Axon Instruments).

We also performed control experiments to check how the different labeling efficiencies might affect the calculated expression fold factors. In our test experiments, we found that the fold factor correlation between probes labeled with Cy3/Cy5 as compared with the fold factors derived from the same probes reversely labeled resulted in an average correlation factor of R = 0.98, indicating that this effect is only of minor importance in our experimental setup.

Expression Data Analysis

To check for the quality of the expression profiling experiments, the hybridization signals detected by the scanner were further processed by Genedata Expressionist Refiner 1.0 (Genedata) using the default settings. This processing included featurewise as well as global chip quality checks, such as chip defect identification, associated feature masking, and background subtraction. The corrected signals of all features were used for a global microarray normalization, with the scaling factor being calculated, which required the sum of all logarithmized values in the Cy3 channel to equal all logarithmized values in the Cy5 channel. Lastly, average fold factors of replicate features were calculated, following the data processing strategy described previously (Goryachev et al. 2001). Only microarray hybridizations with valid expression values for >75% of all the B. subtilis genes were considered in the subsequent analyses.

This approach has been chosen to eliminate experimental artifacts, such as heterogeneous hybridizations, self-fluorescence of the microarrays, different labeling efficiencies of the dyes, and inhomogeneities arising from DNA chip defects. Details are available on request. The final biostatistical analysis, including the correlation analysis, was performed using Genedata Expressionist Analyst 3.1 (Genedata).

Identification of Operon Structures

The whole-genome sequence of B. subtilis was taken from the latest genome release at the NCBI (Kunst et al. 1997). As cotranscription onto a polycistronic mRNA molecule implies approximate equimolarity of the amplified cDNA, neighboring genes in an operon are expected to show similar hybridization signals. Thus, we compared the correlation coefficients RyjaX of consecutive genes. Similar RyjaX values indicate correlated cellular transcript abundances, hence indicating likely candidates for operon structures (Sabatti et al. 2002). The following operational definition of operons was used in this work: If two neighboring protein coding genes that are transcribed on the same DNA strand both have values RyjaX > 0.5, they are considered as part of an operon structure. By iterating this procedure, larger operon structures can be reconstructed. This method automatically prioritizes the most prominently regulated promoters, whereas less-regulated promoters will be considered to be of comparably minor importance (including possible internal promoters). This approach reproduces most known B. subtilis operons (data not shown).

Because we only listed the 20 most yjaX-correlated transcripts in Table 2, some operons appear incompletely represented. We find it necessary to discuss this seeming inconsistency for the panBCD operon. The correlation coefficient for panC is RpanC = 0.5507, and the correlation rank with regard to yjaX is 33 (out of ∼4100 genes), whereas the correlation of the neighboring operon genes are RpanB = 0.6356 (rank = 13) and RpanD = 0.6412 (rank = 11). As a result, all three pan genes are highly correlated with the expression profile of yjaX. The observed minor variations in the correlation coefficients (as in the case of panB, panC, and panD) can be explained by the experimental noise and possibly also by preferential degradation effects of polycistronic mRNA (Selinger et al. 2003). Details are provided in Supplemental Table S1.

Motif Discovery Strategy

If a gene lies within an operon, its promoter and regulatory elements can lie several genes upstream (McGuire et al. 2000). To identify the genomic sequence regions most likely holding genetic regulators, we used the 5′ sequences upstream of the first gene in the predicted transcriptional units, the so-called operon head gene. The motif search was restricted to the region spanning from 400 nt upstream to the translation-start codon of the operon head gene, as most known prokaryotic TF-binding sites can be found in this region (Mironov et al. 1999; McGuire et al. 2000). The regulatory elements in these sequences were identified with Genedata Phylosopher 4.0 (Genedata). Here, the upstream sequences of the top 10 yjaX-correlated transcriptional units were searched for conserved DNA motifs with a maximum width of 25 nt. In brief, common DNA patterns were identified by stochastically maximizing the information content per aligned site in a given sequence window of width W = 25 nt or, equivalently, to minimize the sequence alignment entropy Σi = 1,..., W Σj = A,T,G,C ci, j log(ci, j), where the numbers ci, j are the relative fractions of a defined nucleotide type (j being A, T, G, or C) at a relative position i within the alignment window i = 1,..., W (Lawrence et al. 1993).

We have performed independent controls using all the upstream regions of the known fatty acid biosynthesis genes, including acsA, accA, accB, accC, accD, fabD, yjaX, acpA, yjbW, yfhR, fabZ, yjaY, fabG, and yhfB. It could be shown that the inclusion of all upstream sequences did not enable us to identify significant TFBS motifs, as there is too much noise in the sequences (data not shown; for a detailed discussion of this problem see, e.g., McGuire et al. 2000). These controls demonstrated that the microarray data were necessary to identify a set of upstream regions that is sufficiently enriched with the TFBS motifs. This was accomplished by the expression data, which helped in (1) identifying genes that are as yet functionally uncharacterized, but show a characteristic coexpression behavior, for example, ylpC; (2) including genes that are involved in connecting pathways only, but which are seemingly dependent on the same regulatory mechanism, for example, yhdO; (3) characterizing the operon organization, as the regulator can lie several genes upstream, for example, as it was shown to be the case for fabD and fabG; and (4) identifying genes that play a role in the pathway of interest, but are differently regulated, for example, fabZ or fabL (=yfhR), both of which are known to play a role in FAS, but whose upstream regions were not included for the motif identification search as both genes were shown to not be coexpressed. The information derived from the microarray experiments led to a significant reduction of upstream sequences that needed to be searched for conserved TFBS motifs. The controls performed on the full set of FAS relevant genes indicate that transcription profiling experiments can be critical in identifying and characterizing the regulators of a given pathway.

Whole-Genome TFBS Specificity

To find additional instances of conserved regulatory motifs in the wholegenome sequence of B. subtilis, we developed a model of the identified TFBS by calculating a nucleotide position weight matrix (PWM). Then, the probability PM = Pmotif was calculated, reflecting the likelihood to draw a given DNA sequence from the motif PWM. At the same time, the probability PB = Pbackground was calculated, representing the likelihood to generate the same sequence from the background nucleotide frequencies of the whole B. subtilis genome (Mironov et al. 1999). The similarity score S is defined as S = -log[PM/PB]. Both B. subtilis DNA strands were searched independently. The same analysis was applied to virtual “random genomes”, characterized by the same nucleotide composition as B. subtilis. This procedure was repeated for N = 20 independently randomized genomes, and from the obtained score distributions, the average frequency that a motif of a given similarity score S occurs by chance has been calculated.

Reporter Assay

Standard cloning techniques were applied using Escherichia coli XL1 Blue (Stratagene). Firefly luciferase from pBestluc (Promega) was cloned into the shuttle vector pHT315 (resistance markers: ampicillin in E. coli and erythromycin in B. subtilis; Arantes and Lereclus 1991) via PstI and BamHI after amplification with the primers A (5′-ATCGGATCCAAGGAGATTCCTAGGATGGA AGACGCCAAAAACATAAAG-3′) and B (5′-ATCCTGCAGAGA TCTTTACAATTTGGACTTTCCGCCC-3′). The obtained plasmid pNS 1 was used for integration of the yhfB (=fabHB) upstream region in front of the luciferase gene via the EcoRI restriction site. The upstream region had been amplified from B. subtilis 168 chromosomal DNA using Primers C (5′-GGAATTCCCGGATGGT CAGATTATAACACTA-3′) and D (5′-GGAATTCCCGGGATTGC AAATGCGTATACAA-3′). The resulting construct pNS2 was transformed into B. subtilis 168. The cellular promoter induction assay was performed as follows: The pNS2 carrying B. subtilis strain was grown in LB medium with 5 μg/mL erythromycin to an O.D.600 of 0.25 at 37°C. Then 50 μL of the cell culture was incubated for 3 h at 37°C with various concentrations of antibiotic compounds (vol = 1μL). Luminescence was measured after addition of 25 μL of 0.25 M citrate buffer (pH 5) with 0.8 mM luciferin.

Acknowledgments

We thank U. Reimann, N. Saunders, and S. Doerlemann for technical assistance and D. Talibi for technical advice. We are grateful to C. Shepherd, M. Weirich, and J. Koenig for critically reading the manuscript.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.1275704.

Footnotes

[Supplemental material is available online at www.genome.org.]

References

- Alksne, L.E., Burgio, P., Hu, W., Feld, B., Singh, M.P., Tuckman, M., Petersen, P.J., Labthavikul, P., McGlynn, M., Barbieri, L., et al. 2000. Identification and analysis of bacterial protein secretion inhibitors utilizing a SecA-LacZ reporter fusion system. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44: 1418-1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arantes, O. and Lereclus, D. 1991. Construction of cloning vectors for Bacillus thuringiensis. Gene 108: 115-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, A.A. and Baneyx, F. 1999. Stress responses as a tool to detect and characterize the mode of action of antibacterial agents. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65: 5023-5027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breithaupt, H. 1999. The new antibiotics. Nat. Biotechnol. 17: 1165-1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J.W. and Cronan Jr., J.E. 2001. Bacterial fatty acid biosynthesis: Targets for antibacterial drug discovery. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55: 305-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, K.H., Heath, R.J., and Rock, C.O. 2000. β-Ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase III (FabH) is a determining factor in branched-chain fatty acid biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 182: 365-370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra, I., Hesse, L., and O'Neill, A.J. 2002. Exploiting current understanding of antibiotic action for discovery of new drugs. J. Appl. Microbiol. 92 Suppl: 4S-15S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVito, J.A., Mills, J.A., Liu, V.G., Agarwal, A., Sizemore, C.F., Yao, Z., Stoughton, D.M., Cappiello, M.G., Barbosa, M.D., Foster, L.A., et al. 2002. An array of target-specific screening strains for antibacterial discovery. Nat. Biotechnol. 20: 478-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, H.P. 2001. The impact of expression profiling technologies on antimicrobial target identification and validation. Drug Discov. Today 6: 1149-1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth, R.A., Haselbeck, R.J., Ohlsen, K.L., Yamamoto, R.T., Xu, H., Trawick, J.D., Wall, D., Wang, L., Brown-Driver, V., Froelich, J.M., et al. 2002. A genome-wide strategy for the identification of essential genes in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 43: 1387-1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freiberg, C. and Brunner, N.A. 2002. Genome-wide mRNA profiling: Impact on compound evaluation and target identification in anti-bacterial research. Targets 1: 20-29. [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes, S.Y., Scholle, M.D., D'Souza, M., Bernal, A., Baev, M.V., Farrell, M., Kurnasov, O.V., Daugherty, M.D., Mseeh, F., Polanuyer, B.M., et al. 2002. From genetic footprinting to antimicrobial drug targets: Examples in cofactor biosynthetic pathways. J. Bacteriol. 184: 4555-4572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gmuender, H., Kuratli, K., Di Padova, K., Gray, C.P., Keck, W., and Evers, S. 2001. Gene expression changes triggered by exposure of Haemophilus influenzae to novobiocin or ciprofloxacin: Combined transcription and translation analysis. Genome Res. 11: 28-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffin, C. and Ghuysen, J.M. 1998. Multimodular penicillin-binding proteins: An enigmatic family of orthologs and paralogs. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62: 1079-1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goryachev, A.B., Macgregor, P.F., and Edwards, A.M. 2001. Unfolding of microarray data. J. Comput. Biol. 8: 443-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray, C.P. and Keck, W. 1999. Bacterial targets and antibiotics: Genome-based drug discovery. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 56: 779-787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath, R.J., Yu, Y.T., Shapiro, M.A., Olson, E., and Rock, C.O. 1998. Broad spectrum antimicrobial biocides target the FabI component of fatty acid synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 30316-30320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath, R.J., White, S.W., and Rock, C.O. 2001. Lipid biosynthesis as a target for antibacterial agents. Prog. Lipid Res. 40: 467-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman, J.L. and Brennan, R.G. 2002. Prokaryotic transcription regulators: More than just the helix–turn–helix motif. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 12: 98-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Y., Zhang, B., Van Horn, S.F., Warren, P., Woodnutt, G., Burnham, M.K., and Rosenberg, M. 2001. Identification of critical staphylococcal genes using conditional phenotypes generated by antisense RNA. Science 293: 2266-2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauppinen, S., Siggaard-Andersen, M., and von Wettstein-Knowles, P. 1988. β-Ketoacyl-ACP synthase I of Escherichia coli: Nucleotide sequence of the fabB gene and identification of the cerulenin binding residue. Carlsberg Res. Commun. 53: 357-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunst, F., Ogasawara, N., Moszer, I., Albertini, A.M., Alloni, G., Azevedo, V., Bertero, M.G., Bessieres, P., Bolotin, A., Borchert, S., et al. 1997. The complete genome sequence of the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature 390: 249-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, C.E., Altschul, S.F., Boguski, M.S., Liu, J.S., Neuwald, A.F., and Wootton, J.C. 1993. Detecting subtle sequence signals: A Gibbs sampling strategy for multiple alignment. Science 262: 208-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCue, L., Thompson, W., Carmack, C., Ryan, M.P., Liu, J.S., Derbyshire, V., and Lawrence, C.E. 2001. Phylogenetic footprinting of transcription factor binding sites in proteobacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 29: 774-782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDevitt, D., Payne, D.J., Holmes, D.J., and Rosenberg, M. 2002. Novel targets for the future development of antibacterial agents. J. Appl. Microbiol. 92 Suppl: 28S-34S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, A.M., Hughes, J.D., and Church, G.M. 2000. Conservation of DNA regulatory motifs and discovery of new motifs in microbial genomes. Genome Res. 10: 744-757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mironov, A.A., Koonin, E.V., Roytberg, M.A., and Gelfand, M.S. 1999. Computer analysis of transcription regulatory patterns in completely sequenced bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 27: 2981-2989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moche, M., Schneider, G., Edwards, P., Dehesh, K., and Lindqvist, Y. 1999. Structure of the complex between the antibiotic cerulenin and its target, β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 6031-6034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne, D.J., Warren, P.V., Holmes, D.J., Ji, Y., and Lonsdale, J.T. 2001. Bacterial fatty-acid biosynthesis: A genomics-driven target for antibacterial drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today 6: 537-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne, D.J., Miller, W.H., Berry, V., Brosky, J., Burgess, W.J., Chen, E., DeWolf Jr., W.E., Fosberry, A.P., Greenwood, R., Head, M.S., et al. 2002. Discovery of a novel and potent class of FabI-directed antibacterial agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46: 3118-3124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddell, F.G. 2002. Structure, conformation, and mechanism in the membrane transport of alkali metal ions by ionophoric antibiotics. Chirality 14: 121-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosamond, J. and Allsop, A. 2000. Harnessing the power of the genome in the search for new antibiotics. Science 287: 1973-1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatti, C., Rohlin, L., Oh, M.K., and Liao, J.C. 2002. Co-expression pattern from DNA microarray experiments as a tool for operon prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 30: 2886-2893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schujman, G.E., Choi, K.H., Altabe, S., Rock, C.O., and de Mendoza, D. 2001. Response of Bacillus subtilis to cerulenin and acquisition of resistance. J. Bacteriol. 183: 3032-3040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott, M.G., Gold, M.R., and Hancock, R.E. 1999. Interaction of cationic peptides with lipoteichoic acid and gram-positive bacteria. Infect. Immun. 67: 6445-6453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selinger, D.W., Saxena, R.M., Cheung, K.J., Church, G.M., and Rosenow, C. 2003. Global RNA half-life analysis in Escherichia coli reveals positional patterns of transcript degradation. Genome Res. 13: 216-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, E. and Baneyx, F. 2002. Stress-based identification and classification of antibacterial agents: Second-generation Escherichia coli reporter strains and optimization of detection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46: 2490-2497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stulke, J., Hanschke, R., and Hecker, M. 1993. Temporal activation of β-glucanase synthesis in Bacillus subtilis is mediated by the GTP pool. J. Gen. Microbiol. 139 (Pt 9): 2041-2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, D., Cohen, S., Mani, N., Murphy, C., and Rothstein, D.M. 2002. A pathway-specific cell based screening system to detect bacterial cell wall inhibitors. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 55: 279-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteley, M., Bangera, M.G., Bumgarner, R.E., Parsek, M.R., Teitzel, G.M., Lory, S., and Greenberg, E.P. 2001. Gene expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Nature 413: 860-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, M., DeRisi, J., Kristensen, H.H., Imboden, P., Rane, S., Brown, P.O., and Schoolnik, G.K. 1999. Exploring drug-induced alterations in gene expression in Mycobacterium tuberculosis by microarray hybridisation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96: 12833-12838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]