Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) have emerged as important regulators in human physiological and pathological processes. Recent investigations implicated the involvement of miRNAs in the immune system development and function and demonstrated an unexpected new regulatory level. We summarize the current knowledge about miRNA control in the development of the immune system and discuss their role in the immune and inflammatory responses with a special focus on eicosanoid signaling.

Keywords: microRNA, immune system, eicosanoids, arachidonic acid cascade, inflammation

Introduction

MiRNAs are small non-coding RNAs that control gene expression in many cellular processes (He and Hannon, 2004; Grosshans and Filipowicz, 2008). In 1993, lin-4 was the first miRNA that was discovered in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans and was found to regulate the gene lin-14 on posttranscriptional level during C. elegans development (Wightman et al., 1993). Shortly after, a second small miRNA involved in worm development, let-7, was identified. However, at this time it was assumed that these RNAs are rare exceptions and only present in nematodes. In 2001, three independent publications reported the existence of several hundreds of these small non-coding RNAs not only in nematodes but also in murine and human cells. In the meantime, more than 1000 miRNAs have been identified (http://www.mirbase.org) and have emerged as important regulators of gene expression. They play a key role in many physiological processes such as hematopoiesis, cell proliferation, tissue differentiation, cell type maintenance, apoptosis, signal transduction, organ development (Carissimi et al., 2009) but also in tumorigenesis (Farazi et al., 2010).

Recent reports showed that miRNAs are important control elements in the mammalian immune system. Distinct expression patterns in various hematopoietic organs and cell types points to an important role in immune system development, homeostasis and response, and dysregulation can result in pathological inflammatory responses and cancer (Baltimore et al., 2008; Liang and Qin, 2009; Sonkoly and Pivarcsi, 2009). Here, we will give a short overview about miRNAs important in the development of the immune system and immune and inflammatory responses with a special focus on eicosanoids as important mediators of the inflammatory reactions.

Biogenesis Pathway of miRNAs

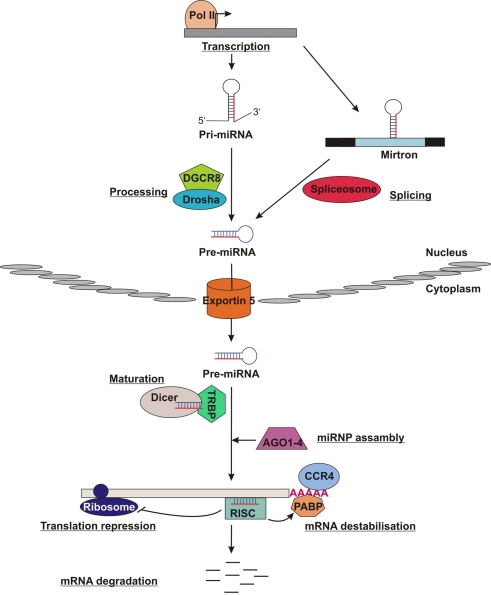

MiRNAs are transcribed as long primary transcripts by RNA polymerase II to produce pri-miRNAs (Figure 1). Canonical miRNAs are subsequently cleaved by Drosha, a member of the RNase-III enzyme family, together with DGCR8, a double-stranded RNA-binding protein (dsRBP). It results in ∼70-nucleotide precursors (pre-miRNAs) containing imperfect stem loop structures (Lee et al., 2003; He and Hannon, 2004; Carissimi et al., 2009). About 40% of the currently known miRNAs are located within introns (mirtrons) which are processed by the spliceosome. Pre-miRNAs are exported from the nucleus to the cytosol by a RanGTP-dependent export complex containing Exportin 5 (Lund et al., 2004; Du and Zamore, 2005). In the cytosol, pre-miRNAs are subsequently processed by Dicer, another member of the RNase-III enzyme family, together with the dsRBP TRBP to short 21–23 nucleotide miRNA duplexes (Hutvagner et al., 2001). Only one strand of the miRNA duplex is being incorporated into a ribonucleoprotein complex (miRNP), also known as RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) whose core components are the Argonaute family proteins (Ago1–4). The other strand is rapidly degraded (Khvorova et al., 2003; Schwarz et al., 2003). MiRNPs are then directed to their binding sites in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of the target mRNA and mediate either translational repression by interaction with the translational machinery or mRNA destabilization through interaction with CCR4. In contrast, miRNAs direct mRNA cleavage when their sequences perfectly match the target mRNA (Lewis et al., 2005; Baek et al., 2008).

Figure 1.

MiRNAs pathway. MiRNAs are transcribed as precursors (pri-miRNA) by RNA polymerase II. The pri-miRNA are cleavaged by Drosha together with DGCR8 into 70-nucleotide stem loop known as pre-miRNA, in contrast mirtrons are processed by the spliceosome. The pre-miRNAs are transported to the cytosol by Exportin 5, where they are further processed by Dicer together with TRBP to mature miRNA. The mature miRNA, indicated in red, is incorporated into a ribonucleoprotein complex (miRNP), also known as RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) whose core components are the Argonaute family proteins (Ago1–4). miRNPs either mediate mRNA destabilization, translational repression, or mRNA cleavage.

miRNAs Involved in Immune System Development

Recently, various miRNAs involved in the regulation of the mammalian immune system have been identified. First evidence came from the overexpression of miRNAs in hematopoietic stem cells which strongly affected B cell development after transplantation in mice (Chen et al., 2004). This observation was further supported by inactivation of components of the miRNA machinery which severely compromises lymphocyte development (Xiao and Rajewsky, 2009). Conditional inactivation of Dicer in T and B lymphocytes resulted in an up to 10-fold reduction in total lymphocyte amount where regulatory T cells were mostly affected (Cobb et al., 2005). A conditional deletion of Ago2 compromises the development of B and erythroid cells (O’Carroll et al., 2007) whereas Dicer knockout seems to completely block the pro- to pre-B cell transition (Koralov et al., 2008). Subsequently, expression profiling combined with bioinformatic analyses attempted to identify individual miRNAs responsible for these phenotypes to explain the effect of miRNAs on B and T cell homeostasis and response.

One prominent example is miR-150. The miRNA shows significant changes in the expression levels during lymphoid development. It is highly expressed in mature B and T cells, but not in their progenitors (Monticelli et al., 2005; Zhou et al., 2007). One of the predicted targets of miR-150 was c-Myb, which is a transcription factor controlling multiple steps of lymphocyte development. Rajewsky and coworkers have demonstrated that miR-150 controls c-Myb expression in vivo. They further showed that the partial block of B cell development through miR-150 expression was indeed due to downregulation of c-Myb (Xiao et al., 2007). These findings highlight that miR-150 is responsible for the transition to the pro-B to the pre-B cell stage during B cell differentiation (Xiao et al., 2007). In addition, miR-150 overexpression can restore correct T cell differentiation in Dicer deficient T cells.

MiR-155 is a further example of a miRNA with a specific function in lymphoid differentiation. Its expression is increased during activation of B and T cells as well as in activated monocytes (Vasilatou et al., 2010). Rajewsky and coworkers analyzed the role of miR-155 in regulating T helper cell differentiation into T helper cell 1 (TH1) and TH2. Furthermore, miR-155 knockout mice indicated that miR-155 is required for an optimal T cell-dependent antibody response. MiR-155 exerts this control by regulation of cytokine production, e.g., interleukin-4 (IL-4) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ; Thai et al., 2007). Bradley and coworkers performed a transcriptome analysis of mice deficient for B cell integration cluster/miR-155 (bic/miR-155) and identified miR-155 regulated genes, including various cytokines, chemokines, and transcription factors (Rodriguez et al., 2007).

MiR-181a has also been identified as a positive regulator of B lymphocyte differentiation. Furthermore, it is involved in thymic T cell differentiation by activation of the T cell receptors (Chen et al., 2004; Li et al., 2007).

A regulatory circuit involving miR-17-5p, miR-20a, miR-106a, and the transcription factors AML1 and M-CSF have been shown to control monocytopoiesis. The miRNAs are downregulated in unilineage monocytic cultured cells, whereas AML1 is upregulated at protein level but not on mRNA level. Overexpression of miR-17-5p, miR-20a, and miR-106a downregulates AML1 protein expression, leading to downregulation of the M-CSF receptor, enhanced blast proliferation, inhibition of monocytic differentiation, and maturation. Additionally, AML1 inhibits transcription of the miR-17-5p-92 and the miR-106a-92 cluster as a negative feedback (Fontana et al., 2007).

The number of miRNAs with specific function in immune system constantly increases and is comprehensively reviewed elsewhere (Baltimore et al., 2008; Sonkoly and Pivarcsi, 2009). It demonstrates impressively that miRNAs display a highly important, but previously unrecognized level of control of gene expression in the immune system.

miRNAs and Eicosanoids

Beyond their crucial role in immune system development, miRNAs are also involved in immune and inflammatory responses. It became apparent that several miRNAs are induced by inflammatory stimuli (reviewed in Sheedy and O’Neill, 2008). Of note, miR-146 and miR-155 induce pro-inflammatory stimuli like interleukin-1 (IL-1), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and toll like receptor (TLR) and have been involved in the onset of several inflammatory diseases like psoriasis or rheumatic arthritis (Sheedy and O’Neill, 2008).

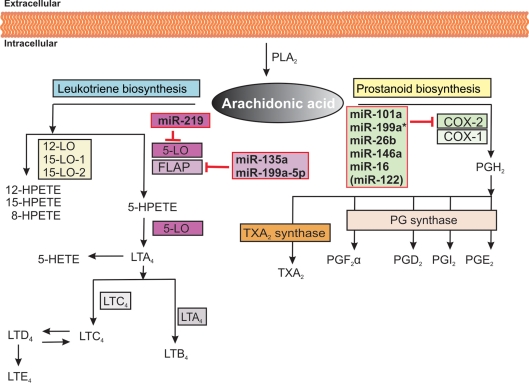

Eicosanoids like leukotrienes and prostaglandins are biologically active lipids and important pro-inflammatory mediators involved in pathological processes such as chronic inflammation and carcinogenesis. Biosynthesis of eicosanoids starts with the release of arachidonic acid from membranes by phospholipases followed by the metabolism of the released arachidonic acid by cyclooxygenases, lipoxygenases, and P450 epoxygenase pathways (Figure 2; Wang and Dubois, 2010). Recent findings indicate that several miRNAs are also involved in the control of key enzymes of the eicosanoid production.

Figure 2.

Overview of arachidonic acid cascade and miRNAs involved in regulation. Arachidonic acid is released from cellular membranes by cytosolic phospholipase A2 (PLA2). The free arachidonic acid can further be converted to eicosanoids by three different pathways involving lipoxygenases (LO), cyclooxygenases (COX), and the cytochrome P450 monooxygenase pathway (not shown), respectively. COX enzymes catalyze the conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandin G2, which is reduced to prostaglandin H2 (PGH2). By specific prostaglandin (PG) and thromboxane (TXA2) synthases, PGH2 is subsequently converted to different prostaglandins and thromboxane A2. Different LO enzymes convert the arachidonic acid to biologically active metabolites such as leukotrienes and hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HPETEs). In the leukotriene pathway, arachidonic acid is converted to 5-HPETE, which is further metabolized to the unstable leukotriene A4 (LTA4). LTA4 is converted to LTB4 or the cysteinyl-containing LTC4, LTD4, and LTE4. The red boxes highlight which miRNAs are involved in the regulation of key enzymes of the arachidonic acid cascade.

miRNAs regulation in prostanoid biosynthesis

Cyclooxygenases (COX) exist in two isoforms, COX-1 and COX-2, both of which catalyze the conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandin H2 which is further metabolized to the various prostaglandins and thromboxane A2. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes exert their biological effects in an autocrine or paracrine manner by binding to their cognate cell surface receptors (Wang and Dubois, 2010). COX-1 was thought to be a housekeeping enzyme responsible for maintaining basal prostanoid levels that are important for tissue homeostasis. By contrast, COX-2 is undetectable in most tissues, but is strongly induced in response to hypoxia, inflammatory cytokines, and other stressors.

COX-2 expression is regulated at various levels (Harper and Tyson-Capper, 2008; Mbonye and Song, 2009). Numerous transcription factors such as nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), activator protein-1 (AP-1), or cAMP-responsive element binding protein (CREP) are involved in the transcriptional regulation (Yamamoto et al., 1995; Kang et al., 2007). Moreover, COX-2 expression is influenced by chromatin remodeling (Deng et al., 2003). An additional level of regulation is the COX-2 mRNA stability and translation efficiency. Several cis-acting sequences, like AU-rich elements (ARE), have been identified within the ∼2000 nt long 3′ UTR. Trans-acting proteins, like HuR or the CUG triplet repeat-RNA-binding protein 2 (CUGBP2), recognize these cis-acting sequences and influence the stability of the COX-2 mRNA (Mukhopadhyay et al., 2003; Subbaramaiah et al., 2003). The use of an alternative polyadenylation signal has also be shown to affect mRNA stability and translation (Hall-Pogar et al., 2005).

Recent studies identified miRNAs as additional players in the posttranscriptional control of COX-2 expression. Chakrabarty et al. (2007) observed that miR-199a* and miR-101a share similar temporal and spatial expression profiles like COX-2 in the mouse uterus during implantation. Further studies revealed that COX-2 expression is post-transcriptionally regulated by a direct interaction of miR-101a and miR-199a* with COX-2 3′ UTR in mice (Chakrabarty et al., 2007). The authors showed a similar dependency during endometrial carcinogenesis. An elevated COX-2 level correlated with a decreased expression of miR-101a and miR-199a* suggesting that these two miRNAs are involved in the regulation COX-2 expression in endometrial cancer in mice (Daikoku et al., 2008).

An inverse correlation between COX-2 and miR-101a expression has also been observed in human colon cancer cells. Strillacci et al. (2009) showed that miR-101 decreases COX-2 protein levels in HT-29 cells by translational repression. This coincides with the observation that reduced miR-101 expression correlates with high levels of COX-2 protein expression in colon cancer tissues and liver metastases derived from colorectal cancer patients (Strillacci et al., 2009). Hiroki et al. (2010) found a similar relationship between COX-2 expression and miR-101. They identified a strong positive immunoreactivity of COX-2 which significantly correlated with the downregulation of miR-101 in patients with endometrial serous carcinoma (Hiroki et al., 2010). A similar inverse relationship between COX-2 and miR-101a expression have been observed in mammary gland indicating that miR-101 regulates cell proliferation via COX-2 expression (Tanaka et al., 2009).

The expression pattern of the miR-26b is also inversely correlated with COX-2 expression in desferrioxamine (DFOM)-treated carcinoma cells of the nasopharyngeal epithelium. Here, a feedback of COX-2 expression on the miRNA level has been demonstrated (Ji et al., 2010).

Lukiw and coworkers reported that herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) infection of human brain cells induces miR-146a that is associated with pro-inflammatory signaling in stressed brain cells and Alzheimer’s disease. It has been shown that HSV-1 infection leads to the upregulation of pro-inflammatory markers such as cytosolic phospholipase A2, COX-2, and IL-1β, but also of miR-146a, coupled to a decreased expression of the immune system repressor complement factor H (CFH). The authors suggest that the miR-146a mediated downregulation of CFH and the subsequent upregulation of key members of the arachidonic acid cascade contribute to Alzheimer-type neuropathological changes (Hill et al., 2009). Recent studies demonstrate that fibroblasts from patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) produce increased amounts of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) in response to the inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α. The decreased expression level of miR-146a leads to reduced degradation of COX-2 mRNA and overproduction of PGE2. This specific miR-146a overexpression in COPD fibroblast is a new pathophysiologic mechanism contributing to the abnormal inflammatory response in COPD patients (Sato et al., 2010).

Jing et al. (2005) have shown that miR-16 induces TNF-α and COX-2 mRNA degradation. Interestingly, this regulation is not only dependent on the enzymes of miRNA dependent decay but also on tristetraproline (TPP) which binds ARE and directs rapid mRNA decay (Jing et al., 2005). A direct interaction for miR-16-1 with its binding site on the target mRNA as well as an influence on ARE-mediated mRNA stability has been demonstrated. MiR-16 contains an 8-nt-sequence (UAAAUAUU) that is complementary to the ARE. MiR-16 is required for ARE-mediated decay in a sequence specific manner and requires the ARE-binding protein TTP which is involved in the formation of the decay complex. This shows that miRNAs which target ARE appear to be an essential step in ARE-mediated regulation (Jing et al., 2005; Calin et al., 2008; von Roretz and Gallouzi, 2008).

Another miRNA involved in ARE-mediated decay was recently identified by Filipowicz and coworkers. They showed that HuR was able to rescue translation of repressed cationic amino acid transporter-1 (CAT-1) mRNA, probably by interfering with the association of miR-122 with AREs within the 3′ UTR of CAT-1 mRNA (Bhattacharyya et al., 2006). Since the stability of COX-2 mRNA is also dependent on HuR (Subbaramaiah et al., 2003) it can be speculated that miR-122 can also be involved in COX-2 regulation.

A further interesting aspect is if and how miRNAs itself are controlled by prostanoids. In a recent report, Ruan and coworkers found that prostacyclin (PGIe) influence expression of several miRNAs (upregulation of miRNA-711, miRNA-744, and miRNA-148b, downregulation of miR-466f-3p, miR-148a, miR-7a, miR-374). The regulation was mediated via the PGI2 receptor and was found to inhibit insulin-mediated lipid deposition in a mouse adipose tissue derived primary culture cell line (Mohite et al., 2011). This study indicates that miRNA regulation may be involved in a wide range of pathophysiological processes.

miRNA regulation in leukotriene biosynthesis

The 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO) enzyme interacts with a 5-LO activating protein (FLAP) to convert arachidonic acid to the unstable leukotriene A4 (LTA4). FLAP is essential for cellular leukotriene biosynthesis since it binds arachidonic acid and presents it to 5-LO. LTA4 is subsequently converted into biologically active leukotriene B4 (LTB4) by LTA4 hydrolase or to leukotriene C4 (LTC4) by LTC4 synthase. LTC4 can be enzymatically converted to leukotriene D4 which is metabolized to leukotriene E4 (Figure 2; Wang and Dubois, 2010).

Gonsalves and Kalra examined the effect of hypoxia on FLAP expression in human pulmonary vascular endothelial cells and in a transformed human brain endothelial cell line. They could demonstrate that hypoxia-mediated FLAP expression is regulated at the level of transcription. Furthermore, FLAP expression is negatively regulated by miR-135a and miR-199a-5p which provides a novel mechanism for the fine tuning of leukotriene production (Gonsalves and Kalra, 2010).

Recchiuti et al. (2011) identified a set of miRNAs that were temporally regulated in a self-limited acute inflammatory response and influenced by the lipid mediator resolving D1 (RvD1) which is involved in the resolution of inflammation. MiR-21, miR-146b, and miR-219 were upregulated by RvD1. They analyzed the effect of miRNA overexpression on genes involved in inflammatory and immune response and identified a plethora of candidates including cytokines and proteins involved in immune reactions like NF-κB. Based on these data the authors create networks of target genes of RvD1-regulated miRNAs (Recchiuti et al., 2011). 5-LO was among the identified targets of miR-219. Overexpression of miR-219 gave a reduction of 5-LO protein by 20% and a reduced leukotriene production. However, since no direct binding site for miR-219 is predicted within the 5-LO 3′ UTR the effect may be indirect (Recchiuti et al., 2011).

An interesting report by Dincbas-Renqvist et al. (2009) showed that 5-LO can interact with the C-terminal domain of human Dicer. The interaction between the 5-LO binding domain with a dicer fragment was shown to enhance 5-LO enzymatic activity in vitro, whereas 5-LO modified the processing activity of Dicer. These results suggest that the processing of specific miRNAs by Dicer might be regulated by 5-LO/Dicer interaction in inflammatory and cancer cells (Dincbas-Renqvist et al., 2009).

Conclusion and Perspectives

Eicosanoids including leukotrienes and prostaglandins are important biologically active lipids regulating immune responses in the body (Wang and Dubois, 2010). Recent evidence suggests that miRNAs are indeed involved in inflammatory signaling, yet research is clearly still at the beginning and the extent and importance of miRNA mediated regulation remains to be discovered. The number of identified miRNAs involved in eicosanoid pathway continues to grow and the examples reviewed here may just be the tip of an iceberg with the complexity of their possible role in the inflammatory processes not yet been clarified. Many questions are still open like how many miRNAs are involved in eicosanoid signaling, how these RNAs are regulated, which steps in the signaling cascade are targeted, are they associated with acute, chronic, or resolving inflammation, are they key regulators or just involved in fine tuning? A better understanding of the regulation of lipid mediator formation by miRNAs will be of interest not only for the further elucidation of lipid signaling but may open a new avenue in the development of new therapeutic concepts for treatment of inflammation and cancer.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (GRK757, CEF EXC115) and the Aventis Foundation.

References

- Baek D., Villen J., Shin C., Camargo F. D., Gygi S. P., Bartel D. P. (2008). The impact of microRNAs on protein output. Nature 455, 64–71 10.1038/nature07242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltimore D., Boldin M. P., O’Connell R. M., Rao D. S., Taganov K. D. (2008). MicroRNAs: new regulators of immune cell development and function. Nat. Immunol. 9, 839–845 10.1038/ni.f.209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya S. N., Habermacher R., Martine U., Closs E. I., Filipowicz W. (2006). Relief of microRNA-mediated translational repression in human cells subjected to stress. Cell 125, 1111–1124 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calin G. A., Cimmino A., Fabbri M., Ferracin M., Wojcik S. E., Shimizu M., Taccioli C., Zanesi N., Garzon R., Aqeilan R. I., Alder H., Volinia S., Rassenti L., Liu X., Liu C. G., Kipps T. J., Negrini M., Croce C. M. (2008). MiR-15a and miR-16-1 cluster functions in human leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 5166–5171 10.1073/pnas.0800121105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carissimi C., Fulci V., Macino G. (2009). MicroRNAs: novel regulators of immunity. Autoimmun. Rev. 8, 520–524 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarty A., Tranguch S., Daikoku T., Jensen K., Furneaux H., Dey S. K. (2007). MicroRNA regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 during embryo implantation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 15144–15149 10.1073/pnas.0705917104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. Z., Li L., Lodish H. F., Bartel D. P. (2004). MicroRNAs modulate hematopoietic lineage differentiation. Science 303, 83–86 10.1126/science.1094226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb B. S., Nesterova T. B., Thompson E., Hertweck A., O’Connor E., Godwin J., Wilson C. B., Brockdorff N., Fisher A. G., Smale S. T., Merkenschlager M. (2005). T cell lineage choice and differentiation in the absence of the RNase III enzyme Dicer. J. Exp. Med. 201, 1367–1373 10.1084/jem.20050572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daikoku T., Hirota Y., Tranguch S., Joshi A. R., DeMayo F. J., Lydon J. P., Ellenson L. H., Dey S. K. (2008). Conditional loss of uterine Pten unfailingly and rapidly induces endometrial cancer in mice. Cancer Res. 68, 5619–5627 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng W. G., Zhu Y., Wu K. K. (2003). Up-regulation of p300 binding and p50 acetylation in tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced cyclooxygenase-2 promoter activation. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 4770–4777 10.1074/jbc.M209286200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dincbas-Renqvist V., Pepin G., Rakonjac M., Plante I., Ouellet D. L., Hermansson A., Goulet I., Doucet J., Samuelsson B., Rådmark O., Provost P. (2009). Human dicer C-terminus functions as a 5-lipoxygenase binding domain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1789, 99–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du T., Zamore P. D. (2005). MicroPrimer: the biogenesis and function of microRNA. Development 132, 4645–4652 10.1242/dev.02070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farazi T. A., Spitzer J. I., Morozov P., Tuschl T. (2010). miRNAs in human cancer. J. Pathol. 223, 102–115 10.1002/path.2806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana L., Pelosi E., Greco P., Racanicchi S., Testa U., Liuzzi F., Croce C. M., Brunetti E., Grignani F., Peschle C. (2007). MicroRNAs 17-5p-20a-106a control monocytopoiesis through AML1 targeting and M-CSF receptor upregulation. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 775–787 10.1038/ncb1613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilroy D. W. (2010). Eicosanoids and the endogenous control of acute inflammatory resolution. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 42, 524–528 10.4049/jimmunol.0902594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonsalves C. S., Kalra V. K. (2010). Hypoxia-mediated expression of 5-lipoxygenase-activating protein involves HIF-1alpha and NF-kappaB and microRNAs 135a and 199a-5p. J. Immunol. 184, 3878–3888 10.1038/451414a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosshans H., Filipowicz W. (2008). Molecular biology: the expanding world of small RNAs. Nature 451, 414–416 10.1093/nar/gki544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall-Pogar T., Zhang H., Tian B., Lutz C. S. (2005). Alternative polyadenylation of cyclooxygenase-2. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 2565–2579 10.1042/BST0360543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper K. A., Tyson-Capper A. J. (2008). Complexity of COX-2 gene regulation. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 36(Pt 3), 543–545 10.1038/nrg1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L., Hannon G. J. (2004). MicroRNAs: small RNAs with a big role in gene regulation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 5, 522–531 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3283329c05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill J. M., Zhao Y., Clement C., Neumann D. M., Lukiw W. J. (2009). HSV-1 infection of human brain cells induces miRNA-146a and Alzheimer-type inflammatory signaling. Neuroreport 20, 1500–1505 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01385.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiroki E., Akahira J., Suzuki F., Nagase S., Ito K., Suzuki T., Sasano H., Yaegashi N. (2010). Changes in microRNA expression levels correlate with clinicopathological features and prognoses in endometrial serous adenocarcinomas. Cancer Sci. 101, 241–249 10.1126/science.1062961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutvagner G., McLachlan J., Pasquinelli A. E., Bálint E., Tuschl T., Zamore P. D. (2001). A cellular function for the RNA-interference enzyme Dicer in the maturation of the let-7 small temporal RNA. Science 293, 834–838 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.01.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Y., He Y., Liu L., Zhong X. (2010). MiRNA-26b regulates the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in desferrioxamine-treated CNE cells. FEBS Lett. 584, 961–967 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing Q., Huang S., Guth S., Zarubin T., Motoyama A., Chen J., Di Padova F., Lin S. C., Gram H., Han J. (2005). Involvement of microRNA in AU-rich element-mediated mRNA instability. Cell 120, 623–634 10.1016/j.plipres.2007.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y. J., Mbonye U. R., DeLong C. J., Wada M., Smith W. L. (2007). Regulation of intracellular cyclooxygenase levels by gene transcription and protein degradation. Prog. Lipid Res. 46, 108–125 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00801-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khvorova A., Reynolds A., Jayasena S. D. (2003). Functional siRNAs and miRNAs exhibit strand bias. Cell 115, 209–216 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koralov S. B., Muljo S. A., Galler G. R., Krek A., Chakraborty T., Kanellopoulou C., Jensen K., Cobb B. S., Merkenschlager M., Rajewsky N., Rajewsky K. (2008). Dicer ablation affects antibody diversity and cell survival in the B lymphocyte lineage. Cell 132, 860–874 10.1038/nature01916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y., Ahn C., Han J., Choi H., Kim J., Yim J., Lee J., Provost P., Rådmark O., Kim S., Kim V. N. (2003). The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. Nature 425, 415–419 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis B. P., Burge C. B., Bartel D. P. (2005). Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell 120, 15–20 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q. J., Chau J., Ebert P. J., Sylvester G., Min H., Liu G., Braich R., Manoharan M., Soutschek J., Skare P., Klein L. O., Davis M. M., Chen C. Z. (2007). MiR-181a is an intrinsic modulator of T cell sensitivity and selection. Cell 129, 147–161 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2009.02520.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang T. J., Qin C. Y. (2009). The emerging role of microRNAs in immune cell development and differentiation. APMIS 117, 635–643 10.1126/science.1090599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund E., Guttinger S., Calado A., Dahlberg J. E., Kutay U. (2004). Nuclear export of microRNA precursors. Science 303, 95–98 10.5483/BMBRep.2009.42.9.552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbonye U. R., Song I. (2009). Posttranscriptional and posttranslational determinants of cyclooxygenase expression. BMB Rep. 42, 552–560 10.1021/bi101654w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohite A., Chillar A., So S. P., Cervantes V., Ruan K. H. (2011). Novel mechanism of the vascular protector prostacyclin: regulating microRNA expression. Biochemistry 50, 1691–1699 10.1186/gb-2005-6-8-r71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monticelli S., Ansel K. M., Xiao C., Socci N. D., Krichevsky A. M., Thai T. H., Rajewsky N., Marks D. S., Sander C., Rajewsky K., Rao A., Kosik K. S. (2005). MicroRNA profiling of the murine hematopoietic system. Genome Biol. 6, R71. 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00012-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay D., Houchen C. W., Kennedy S., Dieckgraefe B. K., Anant S. (2003). Coupled mRNA stabilization and translational silencing of cyclooxygenase-2 by a novel RNA binding protein, CUGBP2. Mol. Cell 11, 113–126 10.1101/gad.1565607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Carroll D., Mecklenbrauker I., Das P. P., Santana A., Koenig U., Enright A. J., Miska E. A., Tarakhovsky A. (2007). A Slicer-independent role for Argonaute 2 in hematopoiesis and the microRNA pathway. Genes Dev. 21, 1999–2004 10.1096/fj.10-169599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recchiuti A., Krishnamoorthy S., Fredman G., Chiang N., Serhan C. N. (2011). MicroRNAs in resolution of acute inflammation: identification of novel resolvin D1-miRNA circuits. FASEB J. 25, 544–560 10.1126/science.1139253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez A., Vigorito E., Clare S., Warren M. V., Couttet P., Soond D. R., van Dongen S., Grocock R. J., Das P. P., Miska E. A., Vetrie D., Okkenhaug K., Enright A. J., Dougan G., Turner M., Bradley A. (2007). Requirement of bic/microRNA-155 for normal immune function. Science 316, 608–611 10.1164/rccm.201001-0055OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T., Liu X., Nelson A., Nakanishi M., Kanaji N., Wang X., Kim M., Li Y., Sun J., Michalski J., Patil A., Basma H., Holz O., Magnussen H., Rennard S. I. (2010). Reduced miR-146a increases prostaglandin E2 in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease fibroblasts. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 182, 1020–1029 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00759-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz D. S., Hutvagner G., Du T., Xu Z., Aronin N., Zamore P. D. (2003). Asymmetry in the assembly of the RNAi enzyme complex. Cell 115, 199–208 10.1136/ard.2008.100289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheedy F. J., O’Neill L. A. (2008). Adding fuel to fire: microRNAs as a new class of mediators of inflammation. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 67(Suppl. 3), iii50–iii55 10.3109/08830180903208303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonkoly E., Pivarcsi A. (2009). microRNAs in inflammation. Int. Rev. Immunol. 28, 535–561 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strillacci A., Griffoni C., Sansone P., Paterini P., Piazzi G., Lazzarini G., Spisni E., Pantaleo M. A., Biasco G., Tomasi V. (2009). MiR-101 downregulation is involved in cyclooxygenase-2 overexpression in human colon cancer cells. Exp. Cell Res. 315, 1439–1447 10.1074/jbc.M301481200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbaramaiah K., Marmo T. P., Dixon D. A., Dannenberg A. J. (2003). Regulation of cyclooxgenase-2 mRNA stability by taxanes: evidence for involvement of p38, MAPKAPK-2, and HuR. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 37637–37647 10.1016/j.diff.2008.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T., Haneda S., Imakawa K., Sakai S., Nagaoka K. (2009). A microRNA, miR-101a, controls mammary gland development by regulating cyclooxygenase-2 expression. Differentiation 77, 181–187 10.1126/science.1141229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thai T. H., Calado D. P., Casola S., Ansel K. M., Xiao C., Xue Y., Murphy A., Frendewey D., Valenzuela D., Kutok J. L., Schmidt-Supprian M., Rajewsky N., Yancopoulos G., Rao A., Rajewsky K. (2007). Regulation of the germinal center response by microRNA-155. Science 316, 604–608 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2009.01348.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilatou D., Papageorgiou S., Pappa V., Papageorgiou E., Dervenoulas J. (2010). The role of microRNAs in normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Eur. J. Haematol. 84, 1–16 10.1083/jcb.200712054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Roretz C., Gallouzi I. E. (2008). Decoding ARE-mediated decay: is microRNA part of the equation? J. Cell Biol. 181, 189–194 10.1038/nrc2809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Dubois R. N. (2010). Eicosanoids and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 181–193 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90530-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wightman B., Ha I., Ruvkun G. (1993). Posttranscriptional regulation of the heterochronic gene lin-14 by lin-4 mediates temporal pattern formation in C. elegans. Cell 75, 855–862 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao C., Calado D. P., Galler G., Thai T. H., Patterson H. C., Wang J., Rajewsky N., Bender T. P., Rajewsky K. (2007). MiR-150 controls B cell differentiation by targeting the transcription factor c-Myb. Cell 131, 146–159 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao C., Rajewsky K. (2009). MicroRNA control in the immune system: basic principles. Cell 136, 26–36 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K., Arakawa T., Ueda N., Yamamoto S. (1995). Transcriptional roles of nuclear factor kappa B and nuclear factor-interleukin-6 in the tumor necrosis factor alpha-dependent induction of cyclooxygenase-2 in MC3T3-E1 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 31315–31320 10.1073/pnas.0704039104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B., Wang S., Mayr C., Bartel D. P., Lodish H. F. (2007). MiR-150, a microRNA expressed in mature B and T cells, blocks early B cell development when expressed prematurely. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 7080–7085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]