Abstract

The definitions of tolerogenic vs. immunogenic dendritic cells (DC) remain controversial. Immature DC have been shown to induce T regulatory cells (Treg) specific for foreign and allo-antigens. However, we have previously reported that mature DC (G4DC) prevented the onset of autoimmune diabetes whereas immature DC (GMDC) were therapeutically ineffective. In this study, islet-specific CD4+ T cells from BDC2.5 TCR Tg mice were stimulated, in the absence of exogenous cytokine, with GMDC or G4DC pulsed with high- or low-affinity antigenic peptides and examined for Treg induction. Both GMDC and G4DC presenting low peptide doses induced weak TCR signaling via the Akt/mTOR pathway, resulting in significant expansion of Foxp3+ Treg. Furthermore, unpulsed G4DC, but not GMDC, also induced Treg. High peptide doses induced strong Akt/mTOR signaling and favored the expansion of Foxp3neg Th cells. The inverse correlation of Foxp3 and Akt/mTOR signaling was also observed in DO11.10 and OT-II TCR-Tg T cells and was recapitulated with anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation in the absence of DC. IL-6 production in these cultures correlated positively with antigen dose and inversely with Treg expansion. Studies with T cells or DC from IL-6−/− mice revealed that IL-6 production by T cells was more important in the inhibition of Treg induction at low antigen doses. These studies indicate that strength of Akt/mTOR signaling, a critical T cell intrinsic determinant for Treg vs Th induction, can be controlled by adjusting the dose of antigenic peptide. Furthermore, this operates in a dominant fashion over DC phenotype and cytokine production.

INTRODUCTION

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is an autoimmune disease characterized by the destruction of insulin-producing β cells of the islets of Langerhans (1). The non obese diabetic (NOD) mouse provides a useful model for human T1D, since it shares many of the genetic and immunological features of the human disease (2). Recent studies in NOD mice have revealed an age-related progressive decrease in the number and/or function of CD4+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Treg) that is associated with onset of diabetes (3, 4). Treg play an important role in the maintenance of self-tolerance and therapeutic strategies aimed at increasing the number and/or function of Treg have proven effective in preventing autoimmune disease (5–7). The induction and maintenance of Tregs in vivo is dependent on a variety of factors that include co-stimulatory molecules such as CD80 and CD86 (8–11) and cytokines such as TGFβ (6) and IL-2 (12).

Dendritic cells (DC) play an important role both in initiating immunity and in maintaining self tolerance. DC subsets specifically stimulate the activation and differentiation of regulatory T cell types (9, 10, 13, 14). Recent reports have suggested that immature DC can induce the development of functional suppressor cells that express CD4 and CD25 (13) and it has been proposed that immature DC might be a useful therapeutic option in the case of autoimmunity (9, 10). However, the requirement for high levels of costimulatory molecules for the differentiation of Th2 cells (15) as well as suppressor CD4+ CD25+ T cells (8) suggests that immature DC might not effectively generate these populations of regulatory T cells in vivo. Indeed, we have previously shown that immature DC, grown in GM-CSF alone (GMDC), are ineffective at preventing diabetes in NOD mice (16), whereas mature DC, grown in GM-CSF + IL-4 (G4DC), can reproducibly protect these mice (16–18). In addition, we have observed that G4DC therapy causes an increase in CD25+ CD4+ T cells (19). More recently, it was shown that mature DC populations phenotypically similar to therapeutic G4DC were able to induce expansion of sorted CD4+ CD25+ T cells from NOD and BDC2.5 TCR transgenic mice (20, 21). These DC-expanded CD4+CD25+ T cells expressed Foxp3 and were able to prevent diabetes development in vivo.

In this report, we have further examined this phenomenon in the BDC2.5 TCR transgenic system using GMDC and G4DC. We found that both DC populations induced the expansion of CD4+ Foxp3+ Treg in the absence of exogenous TGF-β and that this expansion was antigen dose-dependent. Low doses of cognate antigen preferentially expanded Treg and this was observed for two different peptide mimetopes known to stimulate BDC2.5 T cells (22). Furthermore, we provide evidence that G4DC may naturally present low doses of self antigens to self-reactive T cells in a manner that favors Treg development. The induction of Treg in this in vitro culture system was inversely correlated with the level of signaling via the Akt/mTOR pathway. Analysis of the cytokine requirement of this phenomenon revealed that IL-6 production by T cells, but not DC, inhibited the induction of Treg at low antigen doses. These results suggest that it is possible to enhance Treg development and function in vivo by manipulating both the dose of specific antigen and the type of DC that is targeted.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Mice

NOD, C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). BDC2.5 and BDC 2.5 Foxp3-GFP TCR transgenic mice were obtained from Dr. Christophe Benoist (Joslin Diabetes Center, Boston MA). DO11.10 mice were obtained from Dr. Marc Jenkins (University of Minnesota). OT-II mice and IL-6−/− mice were obtained from Dr. Louis Falo and Dr. Anthony J. Demetris, respectively (University of Pittsburgh). All mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free facility at the University of Pittsburgh and were treated under IACUC-approved guidelines in accordance with approved protocols.

Generation of BMDC

DC were generated as previously described (16, 23), by growing bone marrow precursors for four (NOD) or six (C57BL/6 & BALB/c) days in RPMI containing 5ng/ml GM-CSF (GMDC), or 5ng/ml GM-CSF and 2ng/ml IL-4 (G4DC). GM-CSF was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). IL-4 was from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ). GMDC were purified using CD11c magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotech), yielding a population of largely immature cells. G4DC were purified using a 13.5% Histodenz gradient (Sigma), as previously described (16, 23), to enrich for the mature population. Mature DC derived from these cultures expressed high levels of CD86, CD80, CD40 and MHC class II as previously described (16) (Suppl. Fig. 1).

CD4+ T cell purification and CFSE labeling

CD4+ T cells were purified from dissociated spleens and LN of NOD or BDC2.5 mice by negative selection, using a CD4+ T cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotech). For naïve T cells, MACS-purified CD4+ T cells were stained with anti-CD4-PerCP, anti-CD45RB-FITC, anti-CD62L-PE (BD Bioscience) and anti-CD25-APC (eBioscience) and sorted on a FACSAria (BD Biosciences) to yield the CD4+CD62L+CD45RBhiCD25neg naïve fraction. Prior to stimulation, 5–50 × 106 CD4+ T cells were labeled with 2.5μM CFSE (Invitrogen/Molecular Probes,) diluted in PBS containing 1% FBS, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

In vitro stimulation of T cells

DC and T cells were co-cultured in 96-well U-bottom plates (BD Falcon). DC were seeded at 2 × 104 cells/well and peptides added at least two hours prior to the addition of CFSE-labeled CD4+ T cells (1 × 105/well). Cultures were maintained in complete DMEM, containing Penicillin & Streptomycin, L-Glutamine, Sodium Pyruvate, Non-Essential Amino Acids, Hepes Buffer, β-Mercaptoethanol and 10% FBS. Cells were fed on days 3, 4, 5, and 6 by replacing half of the medium. Cells were harvested at the indicated times for flow cytometric analysis.

Cell staining and flow cytometry

Cell surface staining was performed in PBS containing 2% FBS, with the following antibodies: anti-CD11c-PE, anti-CD25-APC (eBioscience) and anti-CD4-PerCP (BD Bioscience). Intracellular Foxp3 was stained with anti-Foxp3-PacificBlue antibody and staining buffers from eBioscience, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Staining with antibodies against phospho-S6 and phospho-Akt (Cell Signaling Technologies) was performed in conjunction with the Foxp3 antibody and staining buffers. Stained cells were analyzed on an LSR II (BD Bioscience) using FACSDiva software (BD Bioscience).

In vitro suppression assay

CD4+ T cells from TCR-Tg BDC2.5Foxp3GFP reporter mice were stimulated with G4DC and low dose (10pg/ml) AV10 peptide for 5 days to induce Treg proliferation. After 5 days, T cells were stained with PerCP-anti-CD4 and APC-anti-CD25 mAbs (BD). GFP-Foxp3+CD25hi Treg were then sorted on a FACSAria (BD Biosciences). CD4+GFPFoxp3+CD25hi T cells were also isolated from the spleen of BDC2.5 Foxp3GFP reporter mice to serve as a freshly-isolated Treg control. Treg purified from fresh spleen or in vitro DC:T cell cultures were added at various ratios to freshly isolated, PKH26-labeled (24) CD4+ BDC2.5 responder T cells. The mixed T cells were then stimulated with G4DC plus 1ng/ml AV10 for another 5 days, then stained with a PacificBlue-anti-CD4 mAb (eBioscience) and analysed on an LSR II flow cytometer (BD). Proliferation of responders was measured by recording PKH MFI in gated CD4+GFPNeg T cells.

Analysis of cytokine production

Culture supernatants were harvested after 48 hours of DC/T cell co-culture and assayed for the presence of seventeen cytokines/chemokines (IL-1β, IL-1α, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12p40, IL-2p70, IL-13, IL-17, TNF-α, IFN-γ, KC, MIP-1β, MCP-1 and RANTES) using a Milliplex Luminex kit (Millipore), according to the kit instructions. TGF-β concentrations were measured by ELISA, using a Ready-Set-Go Human/Mouse TGF-β ELISA kit (eBioscience). IL-6 production by purified DC was determined by ELISA, using supernatants from DC cultured for 24 hours +/− LPS.

RESULTS

Mature and immature DC presenting low-dose antigen induce proliferation of Foxp3+ Treg

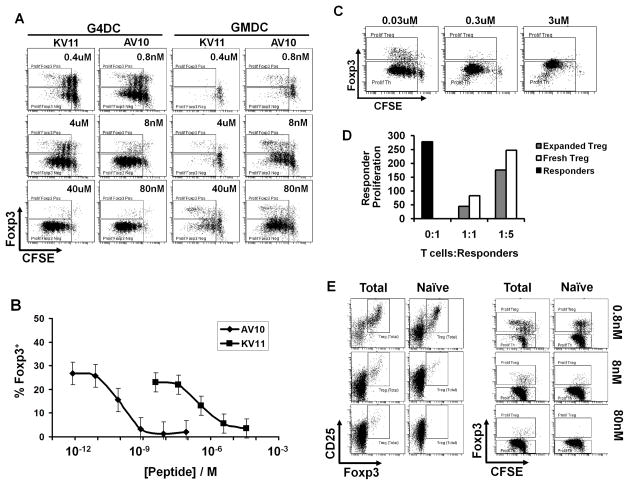

We have previously established that diabetes can be effectively prevented in NOD mice with a single I.V. injection of mature bone marrow-derived G4DC, whereas immature GMDC failed to prevent diabetes (16, 18, 23). As previously shown (16) G4DC and GMDC show marked differences in phenotype, consistent with their differing degree of maturity (Suppl. Fig 1). In this study, we compared the ability of therapeutic G4DC and non-therapeutic GMDC to induce or expand islet-specific Foxp3+ Treg. To do this, we used CD4+ T cells from BDC2.5 TCR-Tg mice. Although the specific antigen recognized by BDC2.5 T cells has not yet been identified, several peptide mimetopes have been described (22). We chose two of the peptides that differ in their apparent affinity for the BDC2.5 TCR: The low-affinity KV11 peptide (KVAPVWVRMME), which has an intermediate EC50 of 75nM; and the high-affinity AV10 peptide (AVRPLWVRME) that has a much lower EC50 of 0.7nM (22) (Suppl. Fig. 1B). We tested the ability of therapeutic G4DC and non-therapeutic GMDC, presenting these two peptides, to induce proliferation and Foxp3 expression in CD4+ T cells purified from BDC2.5 TCR transgenic mice. After 7 days of stimulation with G4DC or GMDC and increasing doses of KV11 or AV10 peptides, CD4+ BDC2.5 T cells were stained for expression of Foxp3 and analyzed for proliferation by CFSE dilution. G4DC loaded with high doses (40μM) of the low-affinity KV11 peptide induced robust proliferation of islet-specific BDC2.5 CD4+ T cells, which were almost exclusively Foxp3− (Fig. 1A, left panels). The same G4DC loaded with a low dose (0.4μM) of KV11 induced less CD4+ T cell proliferation overall, but a substantial number of Foxp3+ Tregs were observed within the proliferating T cell population. A similar antigen dose-dependent pattern was observed with the high-affinity AV10 peptide, with maximal Treg proliferation being observed at low antigen doses and Th proliferation being favored at high antigen doses. However, ~500-fold lower doses of AV10 were required to induce the same Treg expansion that was obtained with KV11 (0.8nM vs 0.4μM, respectively) (Fig. 1B). The shift in the dose-response curves for KV11 and AV10 peptides is consistent with the reported difference in the EC50 of these two peptide mimetopes (22). Interestingly, non-therapeutic GMDC also induced the proliferation of Foxp3+ Treg at low antigen doses and Foxp3− T cells at high peptide doses. Reflecting their lower expression of MHC II (16), GMDC required higher doses of AV10 and KV11 peptides (Fig. 1A, right panels) to elicit the same relative proliferation of Th and Treg obtained with G4DC (Fig. 1A, left panels).

FIGURE 1.

DC presenting low doses of antigen induce and expand suppressive Foxp3+ Treg. A, CFSE-labeled BDC2.5 CD4+ T cells were stimulated for 7d with G4DC or GMDC, plus low-affinity (KV11) or high-affinity (AV10) antigenic peptides at the indicated doses, then stained for CD4 and Foxp3. FACS plots show CFSE and Foxp3 in gated CD4+ T cells. B, Percentage of Foxp3+ CD4+ T cells induced by AV10 and KV11 peptides presented by G4DC. Graph shows mean and standard deviation from three independent experiments. C, CFSE-labelled DO11.10 CD4+ T cells were stimulated for 7d with G4DC plus OVA323 peptide at the indicated doses, then stained for CD4 and Foxp3. D, PKH26-labeled BDC2.5 CD4+ responder T cells were co-cultured for 5 days with CD4+CD25+Foxp3GFP+ BDC2.5 Treg at the indicated ratios. Treg were either freshly isolated or expanded in vitro with G4DC plus low dose AV10. Proliferation of responders was measured by recording PKH26 dilution. Y-axis shows proliferation of gated CD4+GFPNeg responders, represented as 1/MFI PKH26. E, Total or naïve CD4+ BDC2.5 T cells were stimulated for 7 days with G4DC plus AV10 peptide at the indicated doses, then stained for CD4, CD25 and Foxp3. All FACS plots show Foxp3, CD25 and/or CFSE content in gated CD4+ T cells. Data are representative of >3 independent experiments.

Low-dose expansion of OVA-specific DO11.10 T cells

To determine whether expansion of Treg at low antigen doses is a unique feature of autoantigen-specific T cells, we examined the response of CD4+ T cells from DO11.10 (OVA-specific) mice when stimulated with autologous DC presenting their cognate peptide antigens (OVA323). As seen with BDC2.5 T cells, DO11.10 T cells responded in an antigen-dose dependent fashion, with Treg proliferation being favored at low antigen doses (Fig. 1C). This suggests that proliferation of Treg in response to low level stimulation is a general feature of CD4+ T cells, regardless of their specificity for self- or non-self antigens.

Functional suppression by low-dose expanded Treg

It was important to show that the Foxp3+CD4+ T cells expanded in these cultures were functionally suppressive. To this end, CD4+ T cells from BDC2.5 Foxp3GFP reporter mice were stimulated for 7 days with G4DC plus low dose AV10 peptide and the expanded CD25hiFoxp3+ Treg were FACSorted and tested in an in vitro suppression assay. The in vitro expanded CD4+CD25hiFoxp3+ Treg had suppressor activity that was equivalent to, if not better than, that of CD4+CD25hiFoxp3+ Treg sorted from fresh spleen (Fig. 1D). As expected, control CD4+CD25−Foxp3− T cells, either in vitro-cultured or freshly-isolated, did not suppress responder T cell proliferation (not shown).

Conversion of naïve T cells into Treg

It was possible that DC presenting low antigen doses may have (i) expanded pre-existing Treg present in the starting CD4+ population and/or (ii) induced de novo Foxp3 expression in naïve CD4+ T cells. To address these possibilities, naïve CD4+CD25negCD62L+CD45RBHi T cells were sorted to >99.5% purity from BDC2.5 splenocytes and stimulated by G4DC loaded with varying doses of AV10 peptide, as described above. After 7 days of stimulation by G4DC and low dose peptide (0.8nM AV10), Foxp3 expression was induced in 14.7% of the sorted naïve CD4+ T cells, compared to 20.4% Foxp3+ expression when total CD4+ T cells were similarly stimulated (Fig. 1E). Thus, DC presenting low levels of antigen can induce de novo expression of Foxp3 in naïve CD4 T cells.

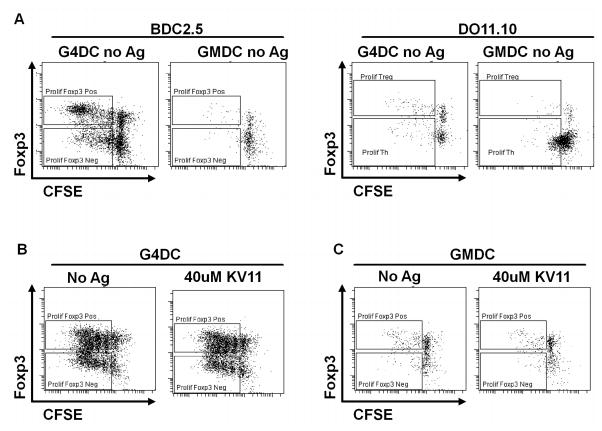

Expansion of autoreactive Treg by unloaded G4DC, but not GMDC

During the course of these experiments we noticed that NOD G4DC were able to induce expansion of BDC2.5 Treg in the absence of any exogenous peptide (Fig. 2A). This phenomenon was more prominent when stimulating whole as compared to naïve CD4+ BDC2.5 T cell (not shown) and was also observed when using unloaded C57BL/6 DC (suppl. fig. 2), which can also present the AV10 peptide and stimulate BDC2.5 Th proliferation. In contrast, OVA-specific CD4+ T cells from DO11.10 or OT-II mice failed to proliferate in response to unloaded BALB/c or C57BL/6 G4DC respectively (Fig. 2A, and Suppl. Fig. 2). Unloaded GMDC did not induce significant proliferation of either BDC2.5 or DO11.10 CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2A). These results suggest that autoreactive BDC2.5 T cells can recognize low levels of endogenous autoantigens presented by mature G4DC, whereas the DO11.10 or OT-II T cells, which are specific for the foreign antigen OVA, do not cross-react with any self antigens expressed by unloaded DC.

FIGURE 2. Unloaded G4DC expand BDC2.5 Treg in the absence of exogenous antigenic peptide.

A, CFSE-labeled CD4+ T cells from BDC2.5 or DO.11.10 mice were stimulated for 7 days with unloaded GMDC or G4DC from NOD or BALB/c mice, respectively, then stained for intracellular Foxp3. B&C, CFSE-labeled CD4+ T cells from NOD mice were stimulated for 7 days with G4DC (B) or GMDC (C) from NOD mice, +/− KV11 peptide, then stained for Foxp3 expression. The figures shown are representative of three similar experiments.

Since unloaded G4DC were able to present endogenous autoantigen to islet-specific BDC2.5 CD4+ T cells, it was possible that they could also present peptides from other endogenous autoantigens and expand autoreactive Treg from the polyclonal NOD T cell repertoire. When CD4+ T cells from NOD mice were stimulated with G4DC, robust expansion of Treg was observed, whether or not the DC were loaded with the BDC-specific antigenic peptides (Fig. 2B). However, unloaded GMDC failed to elicit a significant response from either BDC2.5 or NOD T cells (Fig. 2A & C). When GMDC were loaded with KV11 peptide, proliferation of BDC2.5 T cells was observed (Fig 1A), but NOD T cells failed to respond to peptide-pulsed GMDC (Fig. 2C). These results are consistent with our previous reports that G4DC, but not GMDC, can prevent diabetes in NOD mice, whether or not they are pre-loaded with islet autoantigens (16). The robust proliferation of polyclonal Treg from NOD mice in response to unloaded G4DC but not GMDC is possibly related to the previously-described increased frequency of autoreactive T cells in NOD mice, which has been related to defects in negative selection (25).

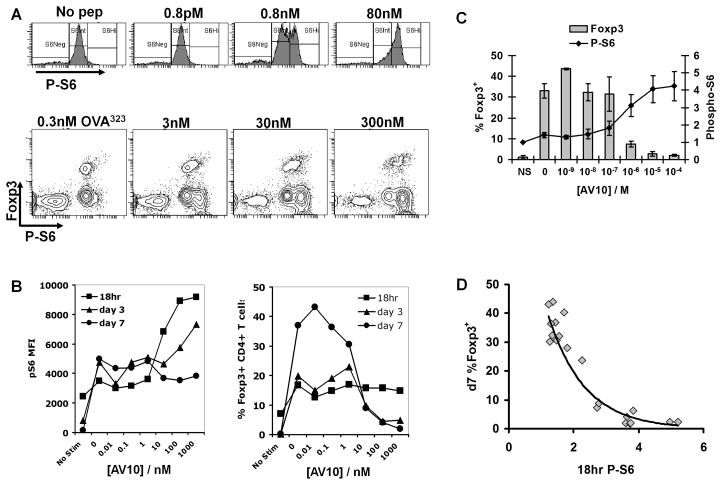

Low dose Treg induction by DC correlates inversely with TCR signaling via Akt/mTOR/S6

The antigen dose response curves in both BDC2.5 and DO11.10 T cells suggested that Treg vs Th expansion is related to the strength of signaling via the TCR, such that strong TCR signaling favors Th expansion and low TCR signaling allows Treg expansion. Indeed, two recent reports described a role for the Akt/mTOR pathway in suppressing Foxp3 expression in CD4+ T cells (26, 27). To examine the role of Akt/mTOR signaling in our system, we measured intracellular levels of phosphorylated S6 ribosomal protein (pS6), a direct target of p70 S6 kinase that is regulated by mTOR (28). BDC2.5 or DO11.10 CD4+ T cells were stimulated with G4DC, as before, and levels of intracellular Foxp3 and pS6 were analyzed by flow cytometry at 18h, 3d and 7d. After 18 hours of stimulation with G4DC presenting high antigen doses, BDC2.5 T cells displayed high levels of intracellular pS6 that decreased as the antigen dose was lowered (Fig. 3A, upper panels). A similar pattern was observed in DO11.10 T cells, with a distinct population of Foxp3neg cells expressing high levels of pS6 emerging as the antigen dose increased (Fig. 3A, lower panels).

FIGURE 3. Expansion of Foxp3+ Treg correlates inversely with TCR signaling via Akt/mTOR/S6.

A, upper panels, CD4+ BDC2.5 T cells were stained for expression of phosphorylated S6 ribosomal protein (pS6) after 18hrs stimulation with G4DC plus indicated dose of AV10 peptide. A, lower panels, pS6 and Foxp3 in CD4+ DO11.10 T cells at 18hrs stimulation with G4DC plus OVA323. B, pS6 MFI (left) and % CD4+ Foxp3+ T cells (right) expression, measured by flow cytometry, in BDC2.5 T cells after 18hr, 3d and 7d stimulation with AV10-loaded G4DC. A and B are representative of ≥3 similar experiments. C, pS6 at 18hrs and Foxp3 at 7 days in BDC2.5 T cells stimulated with G4DC and varying doses of AV10. Graph shows the mean and standard deviation from three independent experiments. D, Inverse relationship of 18hr P-S6 and 7d Foxp3. C&D, Data points derive from three separate experiments. 18 hr pS6 levels were normalized within each experiment to unstimulated control T cells.

We examined the time course of pS6 and Foxp3 expression in BDC2.5 T cells activated with increasing doses of AV10 peptide presented by G4DC (Fig. 3B). The highest levels of pS6 (Fig. 3B, left panel) were seen at 18 hrs and there was a marked drop in pS6 levels once the antigen dose fell below 10 nM. The levels of pS6 diminished over time and, by day 7, no longer correlated with antigen dose. Examination of Foxp3 expression at these same time points (Fig. 3B, right panel) revealed a transient increase, across the whole antigen dose range, in the percentage of Foxp3+CD4+ T cells after 18 hours of co-culture with G4DC. In T cells stimulated with high antigen dose, the frequency of Foxp3+ T cells was reduced at day 3 and Foxp3 expression was completely absent by day 7. Under low antigen stimulation conditions, the percentage of Foxp3+ CD4+ T cells was increased by day 3 and this population was further expanded by the seventh day. The inverse correlation between pS6 expression at 18h and Foxp3 expression at day 7 (Fig. 3C), suggests that differences in the strength of TCR signaling detected after 18 hrs of DC/T cell co-culture result in sustained differences in Foxp3 expression. Results from three independent experiments, plotted on the same graph, show that this inverse correlation of pS6 and Treg frequency is remarkably consistent (Fig. 3D).

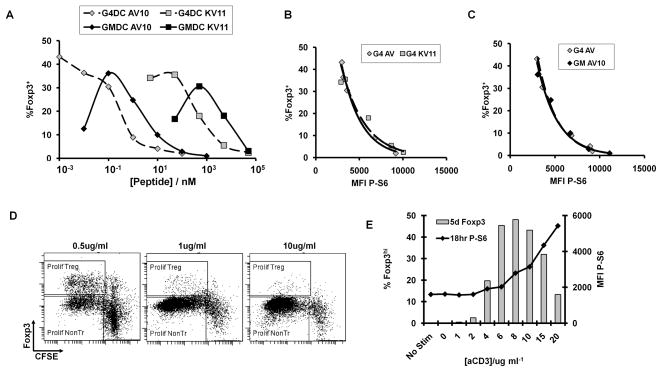

We examined this same relationship through experiments in which the high-affinity (AV10) or low- affinity (KV11) peptide was presented by either GMDC or G4DC. Strikingly, despite the two log difference in the AV10 or KV11 dose required to induce maximal numbers of BDC2.5 Foxp3+ Treg by G4DCs (Fig. 4A), the inverse relationship between pS6 MFI and frequency of Foxp3+ T cells was the same (Fig. 4B). A similarly consistent relationship between pS6 and Treg frequency was observed in the stimulation of BDC2.5 T cells by either G4DC or GMDC presenting the AV10 peptide (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that a threshold level of signaling via the Akt/mTOR pathway may be required to inhibit Foxp3 expression, and this can be achieved with either G4DC or GMDC.

FIGURE 4. Correlation between Ag dose, pS6 and Foxp3 expression.

A–C, CD4+ BDC2.5 T cells were stimulated with G4DC or GMDC, plus high-affinity (AV10) or low-affinity (KV11) peptides, at the indicated doses. T cells were stained at 18hrs for CD4 and intracellular pS6, and at d7 for CD4 and intracellular Foxp3. A, % Foxp3+ cells in CD4+ gate at d7. B and C, pS6 MFI at 18hrs (x-axis) and % Foxp3+ at d7 (y-axis). D and E, CD4+ BDC2.5 T cells were stimulated for with plate-bound anti-CD3 at indicated doses, plus soluble anti-CD28 at 1ug/ml. T cells were stained at 18hrs for CD4 and intracellular Phospho-S6, and at d5 for CD4 and intracellular Foxp3. D, Proliferation and Foxp3 expression in T cells after 5 days of stimulation. E, P-S6 levels at 18hr and % Foxp3 at day5. Data shown in all panels are representative of ≥3 independent experiments.

Expansion of Treg with low dose anti-CD3

From the results described above, the strength of signal 1 delivered via the TCR appears to be critical for controlling the relative expansion of Treg and Th. To test whether Treg induction by weak TCR stimulation could be recapitulated in the absence of antigen presenting cells, purified CD4+ BDC2.5 T cells were stimulated in vitro with anti-CD28 mAb and decreasing doses of anti-CD3. Similar to the antigen dose response observed with the DC-stimulated T cells, expansion of Foxp3+ CD4+ T cells was favored at low anti-CD3 doses, whereas high concentrations of anti-CD3 led to robust Th proliferation (Fig. 4D). At very low concentrations of anti-CD3, no stimulation was observed. Consistent with our results using DC stimulation (Fig. 3C), the dose of anti-CD3 stimulation correlated positively with pS6 levels at 18 hours and inversely with the frequency and proliferation of Foxp3+ Treg after 5 days of culture (Fig. 4E). The results from these experiments indicate that the level of TCR signaling via the Akt/mTOR pathway is a primary determinant of Treg vs Th commitment.

Cytokine production in DC/T cell cocultures

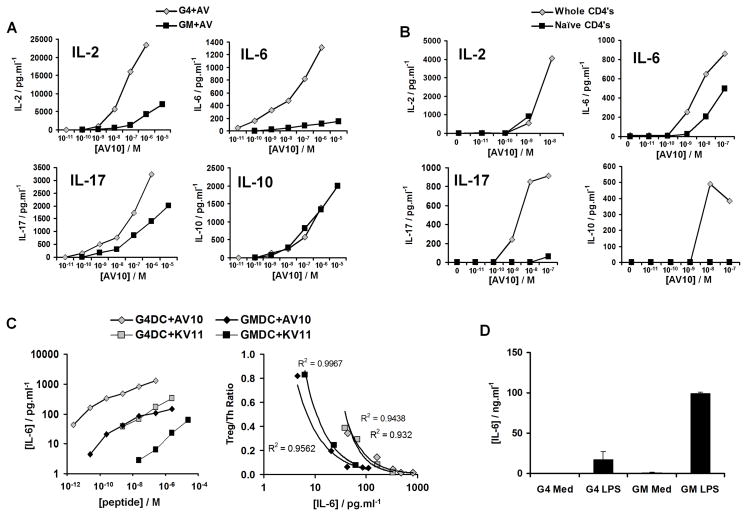

Recent reports have suggested that inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, produced by DC can inhibit TGF-β-mediated Treg induction (29–31). However, our culture system did not include exogenous TGF-β and it could not be detected in the cultures by ELISA (not shown). Nonetheless, cytokines such as IL-2 and IL-6 are known to affect Akt signaling (32–34), which could potentially modulate low-dose Treg induction. CD4+ BDC2.5 T cells were stimulated by G4DC or GMDC, in the presence of AV10 peptide, and the levels of various cytokines in the supernatants were examined after 48 hours by multiplex Luminex assay. Consistent with our previously published results (16, 23), G4DC induced higher levels of type 2 cytokines than GM DC (not shown). IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, IL-17 (Fig. 5A), IL-13, IFN-γ and TNFα (not shown) increased in an antigen-dose dependent fashion. IL-2, IL-6, IL-13 and IL-17 concentrations were higher in cultures with the more mature G4DC, compared to the less mature GMDC, whereas IL-10, TNFα and IFN-γ production levels were similar regardless of the maturation state of the DC used in these cultures (Fig. 5A, & not shown). IL-2, IL-6 and TNFα were the only cytokines observed in cultures of naïve T cells stimulated with G4DC and the AV10 peptide, and the pattern of secretion was similar to that seen with cultures of total CD4+ T cells (Fig. 5B, & not shown). In contrast, no IL-13, IL-17, IL-10 or IFN-γ was detected in cultures of naïve T cells (Fig. 5B, & not shown). Since we observed dose-dependent induction of Foxp3+ T cells in cultures of naïve T cells (Fig. 1E), we conclude that IL-13, IL-17, IFN-γ and IL-10 do not influence the induction of Treg by low antigen doses.

FIGURE 5. Cytokine production in cultures of DC and BDC2.5 CD4+ T cells.

A, Cytokines produced in co-cultures of whole CD4+ BDC2.5 T cells and G4DC or GMDC with the indicated amounts of AV10 peptide. Supernatants were collected after 48 hours of culture. Cytokine levels were determined by multiplex Luminex analysis. B, Cytokines produced in cultures of whole or naïve (CD25−CD62L+CD45RBHi) BDC2.5 CD4+ T cells, stimulated by G4DC plus the indicated concentrations of AV10 peptide. C, Inverse correlation of IL-6 production and Treg induction in co-cultures of whole BDC2.5 CD4+ T cells and GM or G4 DC plus AV10 or KV11 peptides. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. D, IL-6 produced by purified G4 or GMDC in the presence or absence of 1ug/ml LPS. Graph shows the mean ± standard deviation of 2–8 independent experiments.

Previous studies have suggested that IL-6 production by DCs in response to TLR ligands inhibits Treg induction (30, 31). We observed an inverse correlation between IL-6 production and the induction of Foxp3+ T cells (Fig. 5C, right panel), and IL-6 levels were highly sensitive to the maturation level of the DC and the dose of peptide, with the highest levels being produced in cultures with G4DC and AV10 peptide (Fig. 5C, left panel). Therefore, we sought to rule out the possibility of LPS contamination in our system. Examination of cytokine production in DC/T cell co-cultures revealed that no IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-12p40 or IL-12p70 was produced at any dose of peptide used (data not shown). In addition, exposure of DC to peptide alone failed to induce increased expression of CD86 or CD40 (not shown). Furthermore, exposure of GMDC and G4DC to LPS revealed that GMDC produce significantly higher levels of IL-6 than G4DC (Fig. 5D). This is in contrast to the higher IL-6 levels seen in T cell co-cultures with G4DC, versus GMDC (Fig. 5C). These data indicate that the peptides and other solutions used in these cultures were not contaminated with LPS and that the levels of IL-6 detected in the supernatants are due to antigen-specific DC:T cell interactions.

T cell derived IL-6 inhibits low dose Treg induction

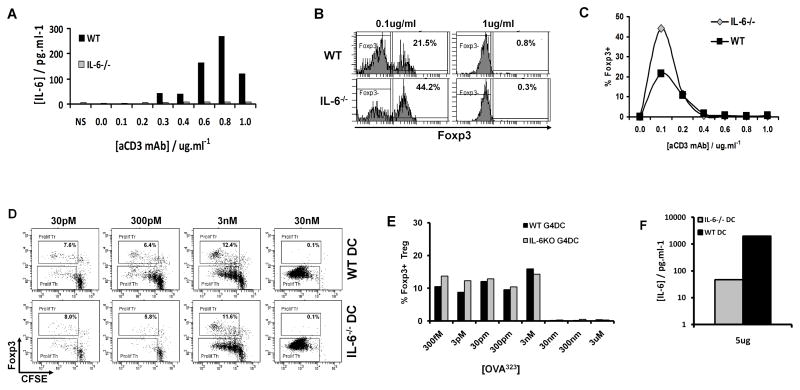

The inverse correlation between IL-6 levels and Foxp3 induction was intriguing and warranted further investigation. In order to determine whether IL-6 in these cultures was produced by DC, T cells or both, and whether this may affect Treg induction, we performed experiments using DC or T cells isolated from IL-6 KO mice. WT CD4+ T cells stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 produced low, but detectable, amounts of IL-6, which increased in a dose-dependent fashion relative to the concentration of stimulatory plate-bound anti-CD3 (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, the frequency of Foxp3+ Treg induced by low doses of anti-CD3 was enhanced in T cells lacking IL-6 (Fig. 6B, left panels & 6C). As seen earlier (Fig. 4D), high doses of anti-CD3 stimulation prevented Treg induction and also abrogated any differences between WT and IL-6−/− T cells (Fig. 6B, right panels, & 6C).

FIGURE 6. IL-6 partially antagonizes low-dose Treg expansion but strong TCR stimulation blocks Foxp3 expression independently of IL-6.

A–C, CFSE-labeled CD4+ T cells from IL-6−/− or WT C57BL/6 mice were stimulated for 5 days with plate-bound anti-CD3 at the indicated doses plus soluble anti-CD28 at 1ug/ml, then stained for CD4 and Foxp3. A, IL-6 production by purified CD4+ T cells from WT or IL-6−/− mice after 48 hours of culture, detected by Luminex. B, Foxp3 expression in gated WT or IL-6−/− CD4+ cells after 5 days stimulation with indicated doses of anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28. C, Induction of Foxp3+ Treg from WT or IL-6−/− CD4+ T cells after 5 days culture with the indicated concentrations of anti-CD3 mAb.

D–F, CFSE-labeled CD4+ T cells from OT-II mice, stimulated for 7 days with G4DC from WT or IL-6−/− mice and the indicated concentrations of OVA323 peptide. D, CFSE and Foxp3 expression in gated CD4+ OT-II T cells after 7 days stimulation. E, Percentage of Foxp3+ OT-II Treg at 7 days. F, IL-6 production, detected in supernatants from co-cultures of OT-II and WT or IL-6−/− DC. All data shown are representative of two independent experiments.

To determine the contribution of IL-6 from DC, CD4+ T cells from OT-II mice were stimulated with OVA323–339 peptide presented by G4DC from WT or IL-6−/− mice. Consistent with our observations in the BDC2.5 and DO11.10 TCR-Tg systems, Foxp3+ OT-II Treg were induced by G4DC presenting low doses of cognate peptide (Fig. 6D&E). However, the efficiency of low-dose Treg induction by G4DC from IL-6−/− mice was similar to WT G4DC (Fig. 6D&E). Thus, low dose Treg induction by G4DC does not appear to be affected by IL-6 from DC. In addition we observed low levels of IL-6 production in cultures of IL-6−/− DC with OT-II T cells (Fig. 6F), demonstrating that T cells can be a source of IL-6 in this system.

DISCUSSION

The experiments presented here demonstrate that Tregs can be induced and expanded by DC that present low doses of cognate antigen and initiate a program of weak TCR signaling via the Akt/mTOR pathway. This phenomenon was observed in three different TCR transgenic systems; NOD-BDC2.5, BALB/c-DO11.10 and C57BL/6-OT-II. The induction of Treg by DC at low antigen doses did not require the addition of exogenous TGF-β or IL-2. We have also shown that low-level antigen presentation by DC can drive both the expansion of pre-existing Treg and the conversion of naïve T cells into de novo Treg. In addition, our results show that unloaded G4DC, but not GMDC, can expand Treg from BDC2.5 mice and from the polyclonal NOD T cell repertoire, suggesting that G4DC may present low levels of endogenous autoantigens, thus bypassing the need for exogenous delivery of autoantigens.

Despite very different phenotypes in terms of expression of maturation markers and cytokine production, both GMDC and G4DC could expand either Treg or Th, provided that an appropriate dose of antigen was applied. Comparison of these two distinct DC populations in combination with two peptides with different affinities for the TCR suggested that the strength of the TCR signal is a critical factor in determining the balance between Th and Treg. This was supported by our ability to induce Treg expansion by stimulating purified CD4+ T cells with low doses of anti-CD3, plus CD28, in the absence of any DC. Our data suggest that there is a low level of TCR stimulation that favors Treg development and this can be achieved when DC present low doses of antigen. Below this threshold, no stimulation occurs. In the context of strong TCR stimulation, full T effector cell activation and differentiation occur.

We observed a strong inverse correlation between pS6 levels induced after 18 hours of stimulation and the resulting development and proliferation of Foxp3+ Treg. Furthermore, the inverse relationship between Akt/mTOR and Foxp3 remained constant, even though the antigen dose required for maximal Treg expansion varied depending on peptide affinity and the phenotype of the stimulating DC. Our results are consistent with recent reports that Akt/mTOR signaling negatively regulates Foxp3 expression in CD4+ T cells (26, 27). In studies by Sauer et al., interruption of the TCR signaling after 18 hours and blockade of the Akt/mTOR pathway, using rapamycin, resulted in increased Treg induction. In addition, this group reported an increase in Foxp3 expression at 18 hours in around 10% of T cells, suggesting that early TCR signaling leads to enhanced Foxp3 expression in a sub-population of T cells. Similarly, in our studies, an increased percentage of Foxp3+ cells was observed after 18hrs of stimulation with all doses of antigen stimulation. Over time, the number of Foxp3+ T cells decreased at the higher antigen doses and increased at lower antigen dose. It has been suggested that a second round of Akt/mTOR signaling via cytokine receptors such as IL-2R regulates the expression of Foxp3 in Treg and effector T cells (35). In our study, the expansion of Treg was inversely correlated with the levels of IL-2 produced and we are exploring the role of STAT5 in this system.

It is now well established that TGF-β can drive the de novo induction of antigen-specific Treg by DC presenting high antigen doses (6, 36, 37) and that this is antagonized by IL-6, which instead promotes Th17 development (29, 38). However, we observed conversion of naïve T cells into Foxp3+ Treg by low antigen doses without the addition of exogenous TGF-β and found no evidence of TGF-β production in these cultures. We conclude that induction of Treg by low antigen dose and weak TCR/Akt/mTOR signaling occurs independently of soluble TGFβ. This is consistent with a recent report that TCRLow BDC2.5 T cells mediate long-term protection from diabetes in NOD.SCID mice independently of TGF-β, whereas TCRHi BDC2.5 T cells induce diabetes (39). Nonetheless, we observed a negative correlation between IL-6 production and Foxp3 expression. As IL-6 is known to signal via the Akt/mTOR pathway (34, 40, 41), this cytokine could also antagonize Treg induction by increasing Akt/mTOR signaling. We therefore examined the ability of IL-6, produced by either T cells or DC, to inhibit Treg induction. These studies revealed that T cell-derived IL-6 could inhibit Treg induction at the very lowest antigen dose. Thus we observed increased low-dose Treg expansion in IL-6−/− T cells. At higher doses the absence of IL-6 did not prevent the expansion of Th cells. In addition, we did not observe a significant difference in pS6 expression at the high doses but IL-6−/− T cells expressed lower levels of pS6 at the lowest dose (data not shown). Interestingly, stimulating WT T cells with IL-6−/− DC did not alter the dose-dependent induction of Treg. This would suggest that the amount of IL-6 produced by T cells in these cultures was sufficient to inhibit Treg induction at the higher antigen doses, or that other signals delivered by DC compensated for the lack of IL-6. Thus, in the absence of any TLR ligand-mediated DC activation, IL-6 production by T cells may play a more important role than DC-derived IL-6 in the inhibition of Treg expansion.

DC can function in apparently contradictory ways; either to induce strong Th responses, to induce deletional tolerance or to activate regulatory T cells. The challenge is to identify a population of DC with the desired function (42–45). Work in recent years suggests that these diverse functions are not the property of defined lineages of DC, but rather that the same DC can function in diverse ways depending on surrounding stimuli. In the absence of pathogen-derived stimuli, resident steady state DC, present in lymphoid organs and the periphery, function to maintain self-tolerance (42, 46). Furthermore, evidence of increased levels of TCR phosphorylation in CD4+ CD25+ T cells suggests that Treg recognize self-antigens in vivo (47). Thus DC may function to induce/maintain Treg populations in vivo by presenting low levels of endogenous autoantigens. This is consistent with our observation that unloaded NOD G4DC could induce low level Akt/mTOR signaling and expand Treg from BDC2.5 mice in the absence of any exogenous peptide antigen, TGFβ or IL-2. Interestingly, immature GMDC, reflecting their lower expression of MHC class II, could only expand BDC2.5 Treg if loaded with peptide. This result correlates with a previous report from our group that loaded or unloaded G4DC, but not GMDC, can prevent diabetes when adoptively transferred to NOD mice (16).

Our results show a T cell-intrinsic correlation between weak TCR signaling and expansion of Foxp3+ Treg. Previous studies have shown that administration of low dose peptide antigen in vivo expands Treg in a DC-dependent manner (48, 49), and this successfully induces tolerance in mouse models of autoimmunity (50, 51). Hence, administration of peptide autoantigens presents an attractive method of inducing antigen-specific tolerance. However, it has been shown that repeated administration of self peptides derived from insulin or GAD65 can induce fatal anaphylaxis in NOD mice (52, 53) and a similar phenomenon was observed in EAE models (54). The insulin study draws parallels with our own studies, as anaphylaxis was observed when a higher dose (100μg/mouse) was used, whereas the lower dose (10 μg/mouse) instead protected NOD mice from diabetes (52). In order for such therapies to be effective, it will be important to establish accurate protocols for the delivery of specific antigens to the appropriate DC at the correct dose and under optimal conditions for the generation of antigen-specific Treg.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dewayne Falkner for assistance with flow cytometry and cell sorting, and Ee Wern Su for assistance with cell signaling studies.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the American Diabetes Association: #1-06-RA-94 (to PM.). MT is supported by a training grant from the National Institutes of Health: #5T32 CA82084-10

References

- 1.Castano L, Eisenbarth GS. Type-I diabetes: a chronic autoimmune disease of human, mouse and rat. Annu Rev Immunol. 1990;8:647–679. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.003243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leiter EL, Prochazka M, Coleman DL. Animal model of human disease, the nonobese diabetic (NOD) mouse. Am J Pathol. 1987;128:380. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tritt M, Sgouroudis E, d’Hennezel E, Albanese A, Piccirillo CA. Functional waning of naturally occurring CD4+ regulatory T-cells contributes to the onset of autoimmune diabetes. Diabetes. 2008;57:113–123. doi: 10.2337/db06-1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gregori S, Giarratana N, Smiroldo S, Adorini L. Dynamics of pathogenic and suppressor T cells in autoimmune diabetes development. J Immunol. 2003;171:4040–4047. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.8.4040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chai JG, Coe D, Chen D, Simpson E, Dyson J, Scott D. In Vitro Expansion Improves In Vivo Regulation by CD4+CD25+ Regulatory T Cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:858–869. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.2.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen W, Jin W, Hardegen N, Lei KJ, Li L, Marinos N, McGrady G, Wahl SM. Conversion of peripheral CD4+CD25− naive T cells to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by TGF-beta induction of transcription factor Foxp3. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1875–1886. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masteller EL, Warner MR, Tang Q, Tarbell KV, McDevitt H, Bluestone JA. Expansion of functional endogenous antigen-specific CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells from nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol. 2005;175:3053–3059. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bour-Jordan H, Salomon BL, Thompson HL, Szot GL, Bernhard MR, Bluestone JA. Costimulation controls diabetes by altering the balance of pathogenic and regulatory T cells. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:979–987. doi: 10.1172/JCI20483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jonuleit H, Schmitt E, Steinbrink K, Enk AH. Dendritic cells as a tool to induce anergic and regulatory T cells. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:394–400. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)01952-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roncarolo MG, Levings MK, Traversari C. Differentiation of T regulatory cells by immature dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2001;193:F5–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.2.f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salomon B, Lenschow DJ, Rhee L, Ashourian N, Singh B, Sharpe A, Bluestone JA. B7/CD28 costimulation is essential for the homeostasis of the CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells that control autoimmune diabetes. Immunity. 2000;12:431–440. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu A, Malek TR. Selective Availability of IL-2 Is a Major Determinant Controlling the Production of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T Regulatory Cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:5115–5121. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jonuleit H, Schmitt E, Schuler G, Knop J, Enk AH. Induction of interleukin 10-producing, nonproliferating CD4(+) T cells with regulatory properties by repetitive stimulation with allogeneic immature human dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1213–1222. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.9.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wakkach A, Fournier N, Brun V, Breittmayer JP, Cottrez F, Groux H. Characterization of dendritic cells that induce tolerance and T regulatory 1 cell differentiation in vivo. Immunity. 2003;18:605–617. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00113-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rulifson IC, Sperling AI, Fields PE, Fitch FW, Bluestone JA. CD28 costimulation promotes the production of Th2 cytokines. J Immunol. 1997;158:658–665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feili-Hariri M, Dong X, Alber SM, Watkins SC, Salter RD, Morel PA. Immunotherapy of NOD mice with bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. Diabetes. 1999;48:2300–2308. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.12.2300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feili-Hariri M, Falkner DH, Gambotto A, Papworth GD, Watkins SC, Robbins PD, Morel PA. Dendritic cells transduced to express interleukin-4 prevent diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice with advanced insulitis. Hum Gene Ther. 2003;14:13–23. doi: 10.1089/10430340360464679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feili-Hariri M, Falkner DH, Morel PA. Regulatory Th2 response induced following adoptive transfer of dendritic cells in prediabetic NOD mice. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:2021–2030. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200207)32:7<2021::AID-IMMU2021>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feili-Hariri M, Flores RR, Vasquez AC, Morel PA. Dendritic cell immunotherapy for autoimmune diabetes. Immunol Res. 2006;36:167–173. doi: 10.1385/IR:36:1:167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tarbell KV, Petit L, Zuo X, Toy P, Luo X, Mqadmi A, Yang H, Suthanthiran M, Mojsov S, Steinman RM. Dendritic cell-expanded, islet-specific CD4+ CD25+ CD62L+ regulatory T cells restore normoglycemia in diabetic NOD mice. J Exp Med. 2007;204:191–201. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tarbell KV, Yamazaki S, Olson K, Toy P, Steinman RM. CD25+ CD4+ T cells, expanded with dendritic cells presenting a single autoantigenic peptide, suppress autoimmune diabetes. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1467–1477. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Judkowski V, Pinilla C, Schroder K, Tucker L, Sarvetnick N, Wilson DB. Identification of MHC class II-restricted peptide ligands, including a glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 sequence, that stimulate diabetogenic T cells from transgenic BDC2.5 nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol. 2001;166:908–917. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feili-Hariri M, Falkner DH, Morel PA. Polarization of naive T cells into Th1 or Th2 by distinct cytokine-driven murine dendritic cell populations: implications for immunotherapy. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:656–664. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1104631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wallace PK, JDT, Fisher JL, Wallace SS, Ernstoff MS, Muirhead KA. Tracking antigen-driven responses by flow cytometry: Monitoring proliferation by dye dilution. Cytometry Part A. 2008;73A:1019–1034. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kishimoto H, Sprent J. A defect in central tolerance in NOD mice. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:1025–1031. doi: 10.1038/ni726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haxhinasto S, Mathis D, Benoist C. The AKT-mTOR axis regulates de novo differentiation of CD4+Foxp3+ cells. J Exp Med. 2008;205:565–574. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sauer S, Bruno L, Hertweck A, Finlay D, Leleu M, Spivakov M, Knight ZA, Cobb BS, Cantrell D, O’Connor E, Shokat KM, Fisher AG, Merkenschlager M. T cell receptor signaling controls Foxp3 expression via PI3K, Akt, and mTOR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:7797–7802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800928105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruvinsky I, Sharon N, Lerer T, Cohen H, Stolovich-Rain M, Nir T, Dor Y, Zisman P, Meyuhas O. Ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation is a determinant of cell size and glucose homeostasis. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2199–2211. doi: 10.1101/gad.351605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, Korn T, Strom TB, Oukka M, Weiner HL, Kuchroo VK. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature. 2006;441:235–238. doi: 10.1038/nature04753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Korn T, Mitsdoerffer M, Croxford AL, Awasthi A, Dardalhon VrA, Galileos G, Vollmar P, Stritesky GL, Kaplan MH, Waisman A, Kuchroo VK, Oukka M. IL-6 controls Th17 immunity in vivo by inhibiting the conversion of conventional T cells into Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18460–18465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809850105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Veldhoen M, Hocking RJ, Atkins CJ, Locksley RM, Stockinger B. TGF[beta] in the Context of an Inflammatory Cytokine Milieu Supports De Novo Differentiation of IL-17-Producing T Cells. Immunity. 2006;24:179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang K, Zhong B, Ritchey C, Gilvary DL, Hong-Geller E, Wei S, Djeu JY. Regulation of Akt-dependent cell survival by Syk and Rac. Blood. 2003;101:236–244. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin SJ, Chang C, Ng AK, Wang SH, Li JJ, Hu CP. Prevention of TGF-beta-induced apoptosis by interlukin-4 through Akt activation and p70S6K survival signaling pathways. Apoptosis. 2007;12:1659–1670. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tu Y, Gardner A, Lichtenstein A. The Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/AKT Kinase Pathway in Multiple Myeloma Plasma Cells: Roles in Cytokine-dependent Survival and Proliferative Responses. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6763–6770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Passerini L, Allan SE, Battaglia M, Di Nunzio S, Alstad AN, Levings MK, Roncarolo MG, Bacchetta R. STAT5-signaling cytokines regulate the expression of FOXP3 in CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells and CD4+CD25− effector T cells. Int Immunol. 2008;20:421–431. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luo X, Tarbell KV, Yang H, Pothoven K, Bailey SL, Ding R, Steinman RM, Suthanthiran M. Dendritic cells with TGF-beta1 differentiate naive CD4+CD25− T cells into islet-protective Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:2821–2826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611646104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamazaki S, Bonito AJ, Spisek R, Dhodapkar M, Inaba K, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells are specialized accessory cells along with TGF-{beta} for the differentiation of Foxp3+ CD4+ regulatory T cells from peripheral Foxp3− precursors. Blood. 2007 doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-088831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dominitzki S, Fantini MC, Neufert C, Nikolaev A, Galle PR, Scheller J, Monteleone G, Rose-John S, Neurath MF, Becker C. Cutting edge: trans-signaling via the soluble IL-6R abrogates the induction of FoxP3 in naive CD4+CD25 T cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:2041–2045. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Calderon B, Suri A, Pan XO, Mills JC, Unanue ER. IFN-gamma-dependent regulatory circuits in immune inflammation highlighted in diabetes. J Immunol. 2008;181:6964–6974. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.6964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hideshima T, Nakamura N, Chauhan D, Anderson KC. Biologic sequelae of interleukin-6 induced PI3-K/Akt signaling in multiple myeloma. Oncogene. 2001;20:5991–6000. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim JH, Kim JE, Liu HY, Cao W, Chen J. Regulation of Interleukin-6-induced Hepatic Insulin Resistance by Mammalian Target of Rapamycin through the STAT3-SOCS3 Pathway. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:708–715. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708568200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lutz MB, Schuler G. Immature, semi-mature and fully mature dendritic cells: which signals induce tolerance or immunity? Trends Immunol. 2002;23:445–449. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02281-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morel PA, Feili-Hariri M, Coates PT, Thomson AW. Dendritic cells, T cell tolerance and therapy of adverse immune reactions. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;133:1–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02161.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morelli AE, Thomson AW. Tolerogenic dendritic cells and the quest for transplant tolerance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:610–621. doi: 10.1038/nri2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Szeles L, Keresztes G, Torocsik D, Balajthy Z, Krenacs L, Poliska S, Steinmeyer A, Zuegel U, Pruenster M, Rot A, Nagy L. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Is an Autonomous Regulator of the Transcriptional Changes Leading to a Tolerogenic Dendritic Cell Phenotype. J Immunol. 2009;182:2074–2083. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steinman RM, Nussenzweig MC. Avoiding horror autotoxicus: the importance of dendritic cells in peripheral T cell tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:351–358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231606698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Andersson J, Stefanova I, Stephens GL, Shevach EM. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells are activated in vivo by recognition of self. Int Immunol. 2007;19:557–566. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Apostolou I, von Boehmer H. In vivo instruction of suppressor commitment in naive T cells. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1401–1408. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kretschmer K, Apostolou I, Hawiger D, Khazaie K, Nussenzweig MC, von Boehmer H. Inducing and expanding regulatory T cell populations by foreign antigen. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1219–1227. doi: 10.1038/ni1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kang HK, Liu M, Datta SK. Low-dose peptide tolerance therapy of lupus generates plasmacytoid dendritic cells that cause expansion of autoantigen-specific regulatory T cells and contraction of inflammatory Th17 cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:7849–7858. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kang HK, Michaels MA, Berner BR, Datta SK. Very low-dose tolerance with nucleosomal peptides controls lupus and induces potent regulatory T cell subsets. J Immunol. 2005;174:3247–3255. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu E, Moriyama H, Abiru N, Miao D, Yu L, Taylor RM, Finkelman FD, Eisenbarth GS. Anti-peptide autoantibodies and fatal anaphylaxis in NOD mice in response to insulin self-peptides B:9-23 and B:13-23. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1021–1027. doi: 10.1172/JCI15488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pedotti R, Sanna M, Tsai M, DeVoss J, Steinman L, McDevitt H, Galli SJ. Severe anaphylactic reactions to glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) self peptides in NOD mice that spontaneously develop autoimmune type 1 diabetes mellitus. BMC Immunol. 2003;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pedotti R, Mitchell D, Wedemeyer J, Karpuj M, Chabas D, Hattab EM, Tsai M, Galli SJ, Steinman L. An unexpected version of horror autotoxicus: anaphylactic shock to a self-peptide. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:216–222. doi: 10.1038/85266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.