Abstract

Aims

We sought to determine the association between living at high altitudes and the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and also to determine the prevalence of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) at various altitudes.

Methods

In the first part of the study, we used data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III to examine the association between altitude of residence and eGFR. In the second part, we used the United States Renal Data System to study the association between altitude and prevalence of ESRD. The query revealed an ESRD prevalence of 485 012 for the year 2005. The prevalence rates were merged with the zip codes dataset.

Results

The mean eGFR was significantly increased at higher altitudes (78.4 ± 21.6 vs 85.4 ± 26.8 mL/min for categories 1 and 5, respectively; P < 0.05). In the analysis of the United States Renal Data System data for prevalence of ESRD, we found a significantly lower prevalence at the altitude of 523 feet and higher.

Conclusion

Using a population-based approach, our study demonstrates an association between altitude and renal function. This association is independent of all factors studied and is reached at approximately 250 feet. There is also a negative association between the prevalence of ESRD and altitude of residence. Further studies are needed to elucidate the pathophysiological basis of these epidemiological findings.

Keywords: altitude, chronic kidney disease, erythropoietin, kidney, NHANES, USRDS

Erythropoietin (EPO) exerts multiple positive functions, including possible slowing the progression of renal disease. It significantly attenuates interstitial fibrosis and reduces apoptotic cell death.1 As apoptotic cell death is a major contributor to chronic kidney disease (CKD) progression,2 it is plausible that, by reducing cell death, EPO might lead to slowing of the progression of CKD. Randomized studies in humans have shown that administration of EPO leads to slowing of CKD progression, and improves cumulative renal survival rate;3 a retrospective study has demonstrated that EPO administration is associated with significant delay in the need for dialysis.4

Furthermore, there is a well-defined relationship between altitude and EPO, which increases in response to low O2 at high altitudes. After 12 h of exposure to 2200 m, there is a significant increase (72%) of EPO above baseline.5 According to a study of 16 participants before and after 4 h of exposure to normobaric hypoxia during a 3-week altitude training (2100–2300 m), there is a wide inter-individual variability in erythropoietic response to altitude (10–185%).6 We hypothesize that residence at high altitude reduces the risk of CKD. The study consists of two objectives. Our first objective was to estimate the association between altitude of residence and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Our second objective was to quantify the association between altitude and prevalence of end-stage renal disease (ESRD).

METHODS

The association between altitude of residence and eGFR

For this part of the study, we used individual-level data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III (NHANES III: 1988–1994). NHANES III contains data for 33 994 persons 2 months and older who participated in the survey,7 oversampling infants, children, those over 60 years of age and racial/ethnic minorities. In order to obtain a nationally representative sample of US residents, a nationwide probability sample of the population is selected, dividing the country into primary sampling units. The altitudes for these sampling units range from 9 to 3695 feet. We initially sorted and merged the three components of the NHANES dataset (demographic, laboratory and physical exam) according to subject SEQUENCE variable. We then merged the NHANES III data, according to county of residence, with the Datasheer dataset (Zip-Codes.Com, Datasheer, Hopewell Jct., NY, USA), which contains county altitudes. This dataset is licensed by the United States Postal Service and has been used extensively by academic institutions, business and industry.8 It contains 65 unique fields of information including latitude, longitude, elevation, population, and socioeconomic and demographic composition for each zip code and is updated monthly. The eGFR variable was calculated using the equation derived from the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study population (eGFR = 186.3 × SerumCr−1.154 * age−0.203 * 1.212 (if black) * 0.742 (if female)).9 The MDRD equation is among the most commonly used formulae for estimation of GFR10 in adults, but has never been recommended in the population under 18 years of age.11 We excluded subjects below the age of 18 and those with insufficient data for calculation of eGFR. As NHANES is not a simple random sample, survey weights were used to estimate nationwide prevalence. Following distribution analysis, we stratified subjects according to altitude of residence (9–39, 40–119, 200–299, 300–599 and 600–3695 feet) into five groups with approximately equal number of subjects. We used Pearson’s correlation coefficient and a multiple regression model with stepwise selection to study the association between eGFR and altitude. Other variables in the model included age, gender, race/ethnicity, body mass index, urban versus rural residence, poverty index, education (highest grade completed), diabetes status and hypertension status. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

The association between altitude of residence and prevalence of ESRD

We used the United States Renal Data System (USRDS) Renal Data Extraction and Referencing (RenDER version 2.0) online data querying application to obtain prevalence data for ESRD according to US counties.12 The ESRD prevalence according to county of residence was merged with the Datasheer dataset. Analysis was done using county level altitudes. Counties were grouped into five groups with approximately equal number of subjects according to altitude (0–131, 132–522, 523–801, 802–1223 and 1225–10190 feet, respectively). Mean ESRD prevalence was calculated for individual altitude categories and the association between the two was tested with t-test and linear regression. Statistic tests were two-sided and significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Our study included 4844 subjects. Demographic characteristics, other than racial/ethnic composition, were similar across the five altitude categories (Table 1). There were disproportionate number of African–American subjects in categories 2 and 4. This is attributed to inclusion of several metropolitan areas within these categories with large African–American populations (Brooklyn, NY; Cleveland, OH; Dallas, TX; Detroit, MI; St. Louis, MO). Similarly, there was a larger proportion of Mexican Americans in category 3, attributable to inclusion of two metropolitan areas in California, both with large Mexican–American population (Fresno and Los Angeles).

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic characteristics of the study population according to altitude category

| Altitude category

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | All | |

| Altitude (feet) | 9–39 | 40–119 | 200–299 | 300–599 | 600–3695 | 9–3695 |

| Number | 1013 | 1020 | 1118 | 884 | 809 | 4844 |

| Age | ||||||

| Mean (years) | 47 | 48 | 46 | 47 | 45 | 47 |

| 95% CI | 45.8, 48.2 | 46.8, 49.2 | 44.9, 47.1 | 45.8, 48.3 | 43.7, 46.3 | 46.5, 47.5 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 503 (50%) | 455 (45%) | 526 (47%) | 437 (49%) | 403 (50%) | 2322 (48%) |

| Female | 510 (50%) | 565 (55%) | 592 (53%) | 447 (51%) | 406 (50%) | 2522 (52%) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 443 (44%) | 409 (40%) | 227 (20%)* | 268 (30%)* | 300 (37%) | 1647 (34%) |

| Black | 223 (22%) | 302 (30%)* | 200 (18%) | 321 (36%)* | 244 (30%) | 1289 (27%) |

| Mexican American | 279 (28%) | 192 (19%)* | 619 (55%)* | 275 (31%) | 251 (31%) | 1616 (33%) |

| Other | 68 (7%) | 117 (11%)* | 72 (6%) | 21 (2%)* | 14 (2%)* | 291 (6%) |

| Co-morbidities | ||||||

| Hypertensive | 253 (25%) | 292 (29%) | 263 (24%) | 257 (29%) | 189 (23%) | 1254 (26%) |

| Diabetic | 81 (8%) | 74 (7%) | 84 (8%) | 76 (9%) | 49 (6%) | 364 (8%) |

P < 0.05 compared with category 1.

The mean eGFR was significantly higher at altitudes above 200 feet (Table 2, vsFig. 1) when compared with lower altitude categories (78.4 ± 21.6 85.4 ± 26.8 feet for categories 1 and 5, respectively; P < 0.05). In addition, the relative risk of eGFR < 60 was lower at altitudes above 200 feet (0.94 vs 1, for altitude category 3 compared with category 1; P < 0.05). We found a significant positive association between eGFR and altitude (Fig. 2). Excluding the values relating to the outlying altitude (3695 feet) from the model resulted in a more statistically significant association (intercept: 80.9 (95% CI: 77–84.7); slope: 0.006 (95% CI: 0.0058–0.0061); Pearson’s correlation coefficient: 0.33 (95% CI: 0.31–0.34)).

Table 2.

Altitude category, mean haemoglobin, eGFR (mL/min) and RR of low eGFR

| Altitude category

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Mean altitude ± SD (feet) | 19 ± 11 | 64 ± 29 | 253 ± 26 | 497 ± 115 | 908 ± 171 |

| Mean haemoglobin ± SD (g/dL) | 13.8 ± 1.4 | 13.9 ± 1.5 | 14 ± 1.5* | 14 ± 1.4* | 14.2 ± 1.5* |

| Mean eGFR ± SD (mL/min) | 78.4 ± 21.6 | 80.0 ± 26.2 | 83.2 ± 21.2* | 84.6 ± 24.3* | 85.4 ± 26.8* |

| % with eGFR < 60 | 16% | 16% | 10% | 12% | 11% |

| RR of eGFR < 60 (95% CI) | 1 | 1.01 (0.96–1.06) | 0.94 (0.89–0.97)* | 0.95 (0.91–0.99)* | 0.95 (0.91–0.99)* |

P < 0.05 versus category 1. eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; RR, relative risk; SD, standard deviation.

Fig. 1.

Mean estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) (mL/min) of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III subjects at the five mean altitude levels (feet). Compared with lower altitudes, mean eGFR is significantly higher at altitudes at or higher than 253 feet. *P < 0.05 versus category 1.

Fig. 2.

Linear regression model of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and altitude of residence (feet) of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III subjects. Factors included in the model include age, gender, race/ethnicity, body mass index, urban versus rural residence, poverty index, education, diabetes status and hypertension status. Intercept: 80.9 (95% CI: 78–86); slope: 0.0018 (95% CI: 0.0018–0.0019); Pearson’s correlation coefficient: 0.22 (95% CI: 0.21–0.23).

The query of the USRDS data for the year 2005 revealed 485 012 people with ESRD in the USA. We found a significantly lower prevalence of ESRD at the altitude of 523 feet and higher. The prevalence of ESRD was 3990 per million population for altitude of 523–801 feet compared with 4172 per million population for altitude of 132–522 feet (P < 0.05) (Table 3 and Fig. 3). The prevalence further decreased to 3841 per million population for altitude of 801–1223 feet. In a linear regression model (Fig. 4), there was a significant negative association between altitude category and prevalence of ESRD (Intercept: 4174 (95% CI: 4138–4210); slope: −74 (95% CI: −59 to −89)).

Table 3.

Altitude category and prevalence of ESRD (per million population)

| Altitude category

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Number | 4981 | 4990 | 5224 | 5386 | 4889 |

| Altitude (feet) | 0–131 | 132–522 | 523–801 | 802–1223 | 1225–10190 |

| Prevalence of ESRD (95% CI) | 4121–4217 | 4124–4220 | 3946–4036* | 3798–3884* | 3922–4018* |

P < 0.05 versus category 1. ESRD, end-stage renal disease.

Fig. 3.

Prevalence of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) according to the five altitude categories among the United States Renal Data System registrants. Compared with lower altitudes, there is a higher prevalence of ESRD at altitudes equal to or higher than 523 feet. *P < 0.05 versus category 1.

Fig. 4.

Linear regression model of altitude category versus prevalence of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) among the United States Renal Data System registrants. Intercept: 4174 (95% CI: 4138–4210); slope: −74 (95% CI: −59 to −89). *Significantly different compared with category 1.

DISCUSSION

Using a population-based approach, our study demonstrates an association between altitude and renal function. We found that eGFR increased with altitude of residence and that the prevalence of ESRD was lower in areas with a higher altitude. These findings are consistent with our hypothesis that residence at high altitude reduces the risk of CKD, independent of all factors studied.

The association between altitude and eGFR was evident at relatively low altitude levels, reaching threshold at approximately 250 feet. We also found a negative association between the prevalence of ESRD and altitude, beginning at the altitude of 500 feet. However, our finding, particularly in the NHANES data may be affected by the sample selection because the sample for NHANES is not selected based upon altitude of residence. Consequently, uncontrolled confounding from sample selection cannot be ruled out.

Delaying the progression of CKD to ESRD is a major challenge in nephrology. In recent years, a significant amount of interest has focused on the role of interstitial fibrosis on progression to ESRD.13,14 Furthermore, hypoxia is associated with tubular damage and with the development of interstitial fibrosis.15 In contrast, EPO increases oxygen supply to tissues which partially corrects the hypoxia and therefore reduces tubular cells damage.13 It also protects against oxidative stress and apoptosis.16,17 Prospective and retrospective studies have shown that correcting anaemia by EPO slows the progression of CKD.3,4,18 Erythropoiesis is a main component of the response to a hypoxic environment such as high altitude19 and increases in EPO of up to 300% over baseline have been reported at altitude of 4500 m.20 Our results suggest that the protective effect of altitude occurs at altitudes of 250–500 feet (750–1500 m). This implies that if the protective effect of altitude is related to EPO, increases smaller than 300% may be protective. It also suggests that factors other than or in addition to EPO may be associated with renal protection at higher altitudes.

For a given altitude, serum EPO increases within hours after arrival at the altitude and peaks on days 1–3, then gradually decreases back towards basal value.21,22 This decrease in EPO levels is a relative change.20 In a study conducted over a 1-year period, the increase in red cell production continued for up to 8 months and resulted in an increase in red cell mass of 50%.23 A similar long-lasting effect of EPO, in response to hypoxia, is also likely to be responsible for the protective effect of residence at high altitude on renal function. Among patients with ESRD, resistance to EPO and EPO requirement for anaemia management are known to decrease at higher altitudes.24 Our study suggests that patients with anaemia of CKD residing at lower altitudes might have increased requirement for exogenous EPO not only for the correction of their anaemia, but also for possible renal protective effect.

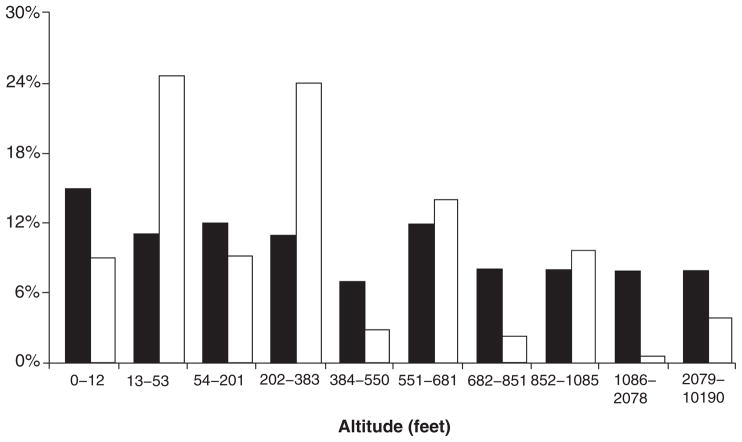

Our study has several limitations. With respect to altitude, the NHANES sample, although a comprehensive population-based survey, has limited data from a limited number of elevations and is not representative of the US population with respect to altitude of residence (Fig. 5). Furthermore, this study does not take into account the duration of residence (i.e. extent of exposure to ‘risk factor’). Although we have attempted to include as many possible confounding variables in the analysis, there may have been uncontrolled confounding. It is possible that those who choose to live close to sea level may be a group with more physical limitations (such as early retirees); this can be a potential source of selection bias and may skew the prevalence of renal disease towards lower altitudes. The association between climatic variables and alterations in blood pressure among patients with ESRD has been previously examined;25,26 it is possible that there is an interaction between altitude, annual mean atmospheric temperature and CKD. Because of the limitations of the datasets, we were not able to incorporate mean temperature as a variable factor in our multiple regression analysis.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of the proportion of the US population (black bars) and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III participants (white bars) at various altitude levels.

Finally, we must emphasize that the current study illustrates an association between altitude and CKD, and that it does not indicate causation.

CONCLUSIONS

We conclude that residence at lower altitude may be a risk factor for lower eGFR and for increased prevalence of ESRD. Therefore, as part of a tailored approach to prevention of CKD in high-risk populations, more stringent risk factor modification may be required for at-risk persons living at lower altitudes. We envision that as the USRDS database becomes more comprehensive, future studies will examine the effect of altitude on progression of kidney disease. In particular, the pathophysiological basis of our epidemiological findings should be elucidated. We recommend exploration of the relationship between endogenous EPO levels at various altitudes and renal function; longitudinal measurements of EPO, altitude and renal function; and epidemiological studies of an altitude-representative population while controlling for length of residence.

Acknowledgments

The data reported here have been supplied by the USRDS. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the US Government. Dr Nasrollah Ghahramani is supported by the Penn State College of Medicine Physician Scientist Award. This publication was made possible by grant number D1BTH06321-01 from the Office for the Advancement of Telehealth, Health Resources and Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services. The Association of Faculty and Friends of Hershey Medical Center and Penn State College of Medicine provided partial funding for this research project.

References

- 1.Nishiya D, Omura T, Shimada K, et al. Effects of erythropoietin on cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction. J Pharmacol Sci. 2006;101:31–9. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fp0050966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanz AB, Santamaria B, Ruiz-Ortega M, Egido J, Ortiz A. Mechanisms of renal apoptosis in health and disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1634–42. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007121336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuriyama S, Tomonari H, Yoshida H, Hashimoto T, Kawaguchi Y, Sakai O. Reversal of anemia by erythropoietin therapy retards the progression of chronic renal failure, especially in nondiabetic patients. Nephron. 1997;77:176–85. doi: 10.1159/000190270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jungers P, Choukroun G, Oualim Z, Robino C, Nguyen AT, Man NK. Beneficial influence of recombinant human erythropoietin therapy on the rate of progression of chronic renal failure in predialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16:307–12. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.2.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonzalez AJ, Hernandez D, De Vera A, et al. ACE gene polymorphism and erythropoietin in endurance athletes at moderate altitude. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38:688–93. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000210187.62672.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedmann B, Frese F, Menold E, Kauper F, Jost J, Bartsch P. Individual variation in the erythropoietic response to altitude training in elite junior swimmers. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:148–53. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2003.011387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ezzati TM, Massey JT, Wakesberg J, Chu A, Maurer KR. Sample Design: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Vital Health Stat 2. 1992;113:1–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Datasheeer, LLC. ZIP Code Database List. 2010 [Cited 16 Mar 2010.] Available from URL: http://www.zip-codes.com/zip-code-database.asp?tab=7.

- 9.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: A new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:461–70. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Botev R, Mallie JP, Couchoud C, et al. Estimating glomerular filtration rate: Cockcroft-Gault and Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formulas compared to renal inulin clearance. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:899–906. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05371008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mattman A, Eintracht S, Mock T, et al. Estimating pediatric glomerular filtration rates in the era of chronic kidney disease staging. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:487–96. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005010034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.USRDS. Researcher’s Guide to the USRDS Database. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rossert J, McClellan WM, Roger SD, Verbeelen DL. Epoetin treatment: What are the arguments to expect a beneficial effect on renal disease progression? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:359–62. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.3.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Heer E, Sijpkens YW, Verkade M, et al. Morphometry of interstitial fibrosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15 (Suppl 6):72–3. doi: 10.1093/ndt/15.suppl_6.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norman JT, Clark IM, Garcia PL. Hypoxia promotes fibrogenesis in human renal fibroblasts. Kidney Int. 2000;58:2351–66. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasap B, Soylu A, Kuralay F, et al. Protective effect of Epo on oxidative renal injury in rats with cyclosporine nephrotoxicity. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23:1991–99. doi: 10.1007/s00467-008-0903-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katavetin P, Tungsanga K, Eiam-Ong S, Nangaku M. Antioxidative effects of erythropoietin. Kidney Int Suppl. 2007:S10–S15. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roth D, Smith RD, Schulman G, et al. Effects of recombinant human erythropoietin on renal function in chronic renal failure predialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 1994;24:777–84. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80671-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robach P, Fulla Y, Westerterp KR, Richalet JP. Comparative response of EPO and soluble transferrin receptor at high altitude. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:1493–8. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000139889.56481.e0. discussion 92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Windsor JS, Rodway GW. Heights and haematology: The story of haemoglobin at altitude. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:148–51. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2006.049734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abbrecht PH, Littell JK. Plasma erythropoietin in men and mice during acclimatization to different altitudes. J Appl Physiol. 1972;32:54–8. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1972.32.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eckardt KU, Dittmer J, Neumann R, Bauer C, Kurtz A. Decline of erythropoietin formation at continuous hypoxia is not due to feedback inhibition. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:F1432–F1437. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1990.258.5.F1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reynafarje C, Lozano R, Valdivieso J. The polycythemia of high altitudes: Iron metabolism and related aspects. Blood. 1959;14:433–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brookhart MA, Schneeweiss S, Avorn J, et al. The effect of altitude on dosing and response to erythropoietin in ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1389–95. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007111181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wystrychowski G, Wystrychowski W, Zukowska-Szczechowska E, Tomaszewski M, Grzeszczak W. Selected climatic variables and blood pressure in Central European patients with chronic renal failure on haemodialysis treatment. Blood Press. 2005;14:86–92. doi: 10.1080/08037050510008850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Argiles A, Mourad G, Mion C. Seasonal changes in blood pressure in patients with end-stage renal disease treated with hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1364–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811053391904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]