Abstract

For over three decades, the scientific community has expressed concern over the paucity of African American, Latino and Native American researchers in the biomedical training pipeline. Concern has been expressed regarding what is forecasted as a shortage of these underrepresented minority (URM) scientists given the demographic shifts occurring worldwide and particularly in the United States. Increased access to graduate education has made a positive contribution in addressing this disparity. This article describes the multiple pathway approaches that have been employed by a school of medicine at an urban Midwest research institution to increase the number of URM students enrolled in, and graduating from, doctoral programs within basic science departments, through the combination of R25 grants and other grant programs funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This article outlines the process of implementing a strong synergistic approach to the training of URM students through linkages between the NIH-funded “Bridges to the Doctorate (BRIDGES)” and “Initiative for Maximizing Graduate Student Diversity (IMGSD)” programs. The article documents the specific gains witnessed by this particular institution and identifies key components of the interventions that may prove useful for institutions seeking to increment the biomedical pipeline with scientists from diverse backgrounds.

Keywords: minorities, pipeline, biomedical, education, training

INTRODUCTION

In the 21st century, the scientific community continues to grapple with the problem of representational diversity in training of future scientists. Underrepresentation on the doctoral level, the pathway to scientific careers, is most severe. According to the 2004 Sullivan Report, “in 2002, only 122 African Americans and 178 Latinos received doctorates in biological sciences compared to 3,114 Whites and 580 Asians” (Chang et al., 2008). More generally, according to 2003 statistics from the American Council on Education, African Americans (190) lagged behind Latinos (213) in terms of underrepresentation of doctoral graduates in comparison to whites overall (4,416) (Ricks 2004). More recently, as noted by Landefeld (2009) “of the 9,329 Ph.D.s awarded in 2006 in the fields of science, only 6% were to Blacks, 4.2% to Hispanics, and 0.2% to Native Americans, for a total of 10.4%,” despite the fact that “these groups currently comprise more than 30% of the population.”

Public health concerns reflect an impending shortage of minority researchers representative of the demographic shifts occurring in the United States (e.g., Latinos surpassing African Americans as the largest minority group) (Millet and Nettles, 2006; Rochin and Mello, 2007). There is an increased need for minority researchers, many of whom conduct research related to health disparities experienced by their racial/ethnic communities of origin (Claudio, 1997; Mitchell and Lassiter, 2006). There are few studies in the literature which focus specifically on Ph.D. attainment for URM students in the biomedical sciences, particularly in departments within medical schools, or which evaluate effectiveness of intervention programs geared toward training URMs in the sciences at both masters and doctoral levels (Capomacchia and Garner, 2004; Fagen and Labov 2007; Hill, et.. al, 1999; Maton and Hrabowski 2004; Pasick, et. al., 2003; Stassun, Burger and Lange, 2008).

The purpose of this article is to describe the intervention programs implemented by the Indiana University School of Medicine (“IUSM”), an urban Midwest research institution, which has garnered relative success to date in addressing the matter of underrepresentation of URM students in the biomedical sciences. The IUSM has received NIH funding over the years that has been instrumental in enhancing the training pipeline. This includes the Bridges to the Doctorate (NIH-NIGMS R25 GM065792-07) and the Initiative for Maximizing Graduate Student Diversity (NIH-NIGMS R25 GM79657-04), as well as T32 research training grants (DK007519-24; AI060519-05; HL 007910-11; CA111198-04; CA111198-04S1), F31 Individual NRSAs (CA106215-05; CA130115), and a T35 short term training grants for minority students (HL007802). We detail here the IUSM's philosophy with regards to recruitment and retention of URM students as well as gains related to the implementation of the BRIDGES and IMGSD programs specifically, and we suggest insights for future efficacy and replication of such programs.

DESCRIPTION OF INTERVENTION PROGRAMS

In order to enhance recruitment and retention of URM students, the IUSM focused sequentially on first partnering with Jackson State University (JSU), an historically black college/university (HBCU) located in Mississippi, applied for a Bridges to the Doctorate (BRIDGES) grant from the NIH with JSU and then applied for an NIH IMGSD grant, also noted above.

Bridges to the Doctorate

Since its inception in 1993, and inclusive of time up to a 2006 report, NIH's Bridges to the Future program, under which the Bridges to the Doctorate program falls, has funded 250 M.S. students, 72 of which began Ph.D. programs; 12 received the Ph.D. in the biomedical or health sciences, across 75 institutions (Henly et al., 2006). The proposed purpose of the Bridges to the Doctorate program is to facilitate a seamless bridge between the Master's Degree at a minority serving institution (MSI) and the Doctoral Degree at a major university, in order to increase the number of URM Ph.D. faculty members and scientists at academic research institutions and in the private sector. IUSM's BRIDGES program commenced in June of 2003 with a three-year award and has since obtained ongoing support through two successful competitive renewals, the first renewal for 3 years, and the most recent one for 5 years of funding.

The program provides summer and regular semester research training in the biomedical sciences to URM students who intend to pursue doctoral degrees. HBCUs produce a greater number of URM students who go on to earn a doctoral degree than more than 95 percent of all predominantly white 4-year colleges and universities (Solorzano 1995; Syverson and Bagley 1999). In a study that examined the B.A. origins of 1,465 African American women between 1975 and 1992, 3 in 4 students obtained their B.A.s in biological sciences from HBCUs (Leggon and Pearson 1997). The BRIDGES program provides an opportunity for students to engage in exploratory research in state-of-the-art facilities that are not readily accessible at their home institutions, due in part to the budgetary constraints traditionally felt by HBCUs. Due to the initial successes of the BRIDGES program witnessed by the IUSM (discussion to follow), the program expanded in the summer of 2008, with a 5 year competitive renewal, to include California State University, Dominguez Hills, a west coast Hispanic-serving institution (which also has a large African American and Native American population) as a second partner.

In terms of financial support, the program provides a 12 month stipend and fee remission for all BRIDGES students; this is a critical component for those students who are economically disadvantaged. In addition to financial support, the program is designed to offer students multi-tiered mentoring through interaction with research intensive faculty, post-doctoral students, other graduate students, trained technicians and Research Associates. Other opportunities offered include interaction with accomplished minority researchers through departmental and school seminars and luncheons, regular meetings with their primary mentors, and tutoring and other training as needed. The BRIDGES program allows students to attend workshops and lectures, network with other scientists, and enter into mentoring relationships that span institutions, with the hope that these interactions will carry forward throughout the student's career. Most important, students have the opportunity during the summer to acquire a mentor at the host institution (IUSM) who would thereafter be engaged along with faculty from JSU in monitoring their progress toward the Master's degree awarded by JSU. The hope, thereafter, would be that students would pursue their doctorate at the host, or another qualified, institution. Although student admission is not guaranteed at the host institution, there is strong incentive by the Graduate School to seriously consider the application of former BRIDGES scholars. The training as part of the BRIDGES program serves to make the student more desirable for admission to this and other Ph.D. programs, offering the student a greater opportunity and flexibility to find the appropriate university to pursue a Ph.D. degree in the student's area of greatest interest.

History of BRIDGES

The concept of partnering with an HBCU and applying together for an NIH BRIDGES grant was initiated in the early 2000's by an Assistant Dean in the Graduate Office of the IUSM's home institution, Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI). A potential relationship was identified with JSU through personal contacts at national education meetings. The Assistant Dean then called together a meeting of interested chairs and faculty of IUSM basic science departments to discuss the possibility of an IUSM/JSU partnership to go forward with a BRIDGES grant application. All in attendance agreed in principle to the concept, but it was necessary to choose a PI and co-PI(s) to initiate this grant proposal. It was decided, and then voted on, to have a PI and co-PI(s) who were nationally and internationally known for their research activities, success in competing for NIH grant support, and who had a track record of training graduate students who subsequently went on to successful careers in academia and health-related areas. The Business Administrator of the faculty member chosen to proceed with the application as PI worked in concert with the PI, co-PI, Assistant Dean and a member of her staff who first initiated the connection with the faculty member from JSU to submit what would become a funded application.

It is important to note that the IUSM had no illusion as to the difficulty of the task ahead. Not the least of concerns was attracting the best students to be part of the program once it was funded. IUSM did not have a long track record with attracting and retaining URM students, and we knew the best students would have their choice of acceptance into more recognizable and “elite” schools. We also knew many of the better students might choose the option of medical, in contrast to graduate, school. All applicants for the BRIDGES program must provide a transcript of courses, a written profile of the student's future aspirations and why they wish to be considered for the award, letters of reference from three faculty members knowledgeable of student progress at the school, and from the coordinator at their school. The applications are then voted on by an Advisory Committee composed of chairs of the basic science departments of the IUSM, other leaders within the IUSM, including those from the Dean's Office and Graduate Program, and select administrators of IUPUI. The committee then assesses fit with a BRIDGES mentor at the IUSM based on a best match for the area the student expresses an interest in, and the desire of the prospective mentor to take such student on in their laboratory. If the student expresses a desire to work in an area that the IUSM does not have activity in, this is discussed with the student to see if the student can identify another area of interest, or decide if our program is not the best for them.

The Advisory Committee took to task the effort to recruit those students who were deemed to have the potential to perform well, as assessed by “desire and hunger” to succeed, good grades, and strong letters of reference from JSU faculty members and our partner coordinator from the school, but who had not definitively shown as yet truly outstanding grades or GRE scores. We knew that this effort entailed substantial risk, but we all felt this was a worthwhile endeavor, and offered the IUSM a potential, perhaps unique, niche from which to proceed and grow in programmatic form. What was clear was that the IUSM and JSU, and faculty associated with these efforts, were willing and dedicated to do their best to make this program succeed.

In short, the concept of the NIH BRIDGES program is to get students who might not traditionally go past the M.S. degree, to do well in the BRIDGES M.S. program, transition into a Ph.D. program at another school, successfully defend their Ph.D. dissertation, and move on to post-doctoral training, with the ultimate goal of tracking students through to positions in academia in a health related area, and successful careers. It takes time for this complete transition, and we are just beginning to see the rewards of this effort. Of 17 students recruited up to 2009 since funding began in 2003 for the BRIDGES program, 13 (72%) have transitioned into Ph.D. programs, with 7 (39%) entering our IUSM, and 6 going to other universities. The IUSM just received its second competitive renewal of the BRIDGES grant, and two of the first three students admitted to the initially funded BRIDGES program have received their Ph.D. from the IUSM, and have begun post-doctoral training at other major universities. Moreover, a third initial student in this program is on track to shortly defend the Ph.D. degree at the IUSM. Four additional BRIDGES students have entered our program since the second competitive renewal was funded.

While we are not completely satisfied, these initial successes are certainly gratifying. However, they were not without the trials and tribulations of normal graduate training, compounded by problems perhaps specific to these students that included lack of confidence, and being placed into an environment that was very foreign to them. The summer(s) spent in the BRIDGES program by the students certainly helped somewhat with addressing the latter concern of a different environment, and seeing what it was like working in a research intensive laboratory, but it did not help them much with addressing the pace and rigor of the academic program at the IUSM compared to JSU, and their initial lack of confidence. This concern and subsequent increase in self-esteem did not come easily for the BRIDGES students, but was helped in part by the faculty members and other non-URM students at the IUSM. With gradual success in the classroom and the laboratory came increased self-esteem. Finding the right mentors for performing the Ph.D. Dissertation laboratory research was crucial, and the first mentor was not always the right one. One of the students had to change mentors half-way through the program and after having passed the Ph.D. Qualifying Exam. This required a complete change in research area. This problem is not only confined to URM students. It is clear that we have not found the perfect formula yet, as one of the BRIDGES students who received an M.S. degree at JSU and transitioned into the IUSM graduate program struggled through course-work more than the others, and then after completing the requested course work, failed the Ph.D. Qualifying Exam twice, and had to leave the program. However, the program as a whole is working in large part because of the dedication of the mentors, the tenacity and desire of the students, and the overall buy-in of the higher echelon of the school, faculty and other students at the IUSM.

Keys to the continued progress and success of this program are our Advisory Board Members. As mentioned above, the entire Advisory Board assesses and votes on the submitted applications. This Advisory Committee also meets twice a year and more often on a need-to-meet basis to discuss the students, and program successes and problems. These meetings are usually scheduled so that the coordinators from our partner MSI institutions can attend and be directly active in all decisions. We have found that the summer research experience is crucial to the success of the student, and the desire of the student to apply to our IUSM graduate program. While the majority of our BRIDGES students have chosen to apply and accept the invitation from our IUSM graduate office to enter the Ph.D. program, some BRIDGES students applied and went to other schools because these other schools had programs of more interest to their particular career aspirations. In one case, a BRIDGES student was not happy with the summer experience here because the mentor did not spend enough time with the student. This mentor is no longer considered as a preceptor for our BRIDGES, or other graduate, students.

Goals and Objectives of the BRIDGES Program

The present and future long-term goals of the BRIDGES Program articulate IUSM's aim to increase the number of URM Ph.D. faculty members and scientists at academic research institutions and in the private sector. These goals are as follows:

Increase the number of URMs who matriculate in and graduate from Ph.D. programs in the basic medical sciences at IUSM or other doctoral granting institutions after completing their master's degrees at partnering minority-serving institutions

Increase the number of URMs, in general, who pursue careers as independent research scientists and faculty members

Institutional Mechanisms to Attain Goals

The interest in meeting the stated goals and objectives and thus ensuring the success of the selected URM students is found throughout the levels of leadership at both IUSM and partner institutions. As such, to help ensure that the appropriate measures are in place for the scholars, the following institutional mechanisms are in place:

Executive Advisory Committee: comprised of senior leaders (e.g., grant PI and co-PI's, Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education, IUSM Department Chairs, Executive Associate Dean for Research, Associate Dean of Graduate Program)

Internal Advisory Committee: comprised of outstanding investigators and senior leaders with successful research careers and proven track records of training highly successful students that receive their Ph.D.s in a timely fashion, go on for post-doctoral training, and secure faculty positions in academia and other health-related areas, BRIDGES mentors, and a non-voting BRIDGES student representative

External evaluator: a nationally-recognized evaluator providing independent formative and summative evaluations based on data we provide the evaluator, and personal interviews in person or by phone that the evaluator conducts with students and mentors of students

Programmatic guidelines have been developed in order to help achieve the expected outcomes:

IUSM and partner faculty periodically discuss ways to link the M.S. and first year Ph.D. curricula: To enhance the ability of the partnering institutions to train promising graduate students, both institutions collaborate on developing master's degree curricula that introduce students to material covered in first-year doctoral courses and prepare them for the rigors of graduate study

IUSM faculty mentoring scholars from the partner institutions: To help strengthen the research capabilities of the master's granting schools, graduate faculty members from IUSM seek to establish collaborative research projects with each student's partner M.S. mentor.

Bringing URM students from the partner institutions to IUSM for a summer research experience as part of their M.S. thesis: Institutional support to ensure a seamless transfer of students from M.S. to doctoral programs, by paying for BRIDGES students’ apartments in the summer, and providing state-of-the art facilities and programs. IUSM faculty members serve as mentors for the BRIDGES students in their master's program and also serve on Master's Committees at the partnering institutions

Competitive admission to IUSM

Provide training and multi-tiered mentorship to enhance the student's readiness for doctoral work: IUSM faculty seek to learn from the partner faculty their experience and expertise in mentoring URM students and provide a supportive network that will encourage and help mentor the students to apply for admission to IUSM graduate program.

Progress of the BRIDGES Program

The relative success of the program thus far can be measured in fulfillment of its purpose; to “bridge” masters students into and through doctoral programs. The BRIDGES program has grown significantly from 3 students in 2003 to a cumulative total of 21 in 2010 as noted above.

IMGSD/Harper Scholars Program

During the first transition of BRIDGES students at JSU to the Ph.D. program at IUSM, it became apparent that additional funds would be needed to support these students during their Ph.D. thesis research. The available pool of research mentors willing to take on these students needed to know they did not have to use their scarce financial resources in this time of dwindling peer-reviewed research funding to support these BRIDGES students, at least at the beginning of the tenure of these students in the mentor's laboratory. This was understandable as the faculty were dependent on the success of their laboratory efforts for promotion and tenure, and the BRIDGES students were novice entities at this time. Hence, as a direct result of this, it was felt necessary to apply for funds from the NIH that would help support these and other URM students in the IUSM.

The IUSM faculty successfully competed for NIH funding for the Initiative for Maximizing Graduate Student Diversity Program (later known as The Harper Scholars Program). This grant, initially funded in March 2007, provides two years of graduate school funding (i.e., stipend, tuition, health/dental insurance, and fees) for URM students in the ten biomedical science Ph.D. programs at the IUSM. In addition, it provides funding for some laboratory supplies and the opportunity to present their research at a national meeting. The students can be supported by Harper funds for 2-3 years; each scholar is expected to seek extramural grant funding to cover their education following their Harper support. The goal of the program is to recruit four students per year into the program. Like the BRIDGES program, the Harper Scholars program offers students multi-tiered mentoring, exposure to accomplished minority researchers through a visiting seminar program, and regular meetings with their mentors. Harper Scholars are also paired with BRIDGES students in the summer, thereby reinforcing the “pipeline.” The program also provides academic support such as preparatory courses and lab technique training for incoming Ph.D. students and tutoring for those who need it, particularly for the first two years of required coursework. In many ways, the program has served as a continuation of the BRIDGES program; half of the current eight participants are BRIDGES alumni. The program is guided by an advisory committee consisting of department chairs, faculty mentors, campus administrators, and usually contains the same members as that for the BRIDGES Advisory Committee. This allows consistency and continuity between the BRIDGES and Harper Scholars programs. As needed, additional members are added or deleted, the latter usually because the advisory members have either left the IUSM or moved on to other roles within the school that occupy their time.

History of The Harper Scholars Program

It was determined during the preparations of the IMGSD grant that naming the grant for someone at the IUSM who had over the years shown high commitment to diversity would provide more visibility for the program, reward the namesake for their efforts, and afford more recognition for the students who would eventually be supported by this program. Towards this end, the grant was named for Dr. Edwin T. Harper, an emeritus faculty member who had been a pioneer in diversity programming at the IUSM. At the beginning of the Harper Scholars program, the Advisory Committee members for the grant determined, after discussion and vote, to place the BRIDGES students who had successfully transitioned to the IUSM Ph.D. program on the grant. The remaining slots were then used to fund other URM students through competitive assessment. The program has evolved since to fill all Harper slots (BRIDGES and non-BRIDGES URM students) by competition.

Goals and Objectives of the Harper Scholars Program

The long-term goal of the Harper Scholars Program is to increase the number of URMs graduating from the ten biomedical science Ph.D. programs at the IUSM. Therefore, the objectives are to:

Prepare Harper Scholars for graduate school through summer instruction (i.e., course entitled, “Elements of a Successful Basic Scientist”);

Provide Harper Scholars with adequate tutoring, mentoring and interaction with role models within their departments or the school at large;

Provide Harper Scholars with the opportunity to engage with and learn from URM scholars from academic research institutions and the private sector, through invited seminar speakers and workshops

Provide funding for two years of study, and a third year if necessary, so students focus on lab work, and for organizing grant writing workshops to assist students in pursuing extramural funding for their remaining graduate school years

Recruitment to the Harper Scholars Program and Ph.D. Training Experience

Students are chosen for this program through a competitive process. At the beginning, students from the BRIDGES program accepted into the IUSM graduate program were given first consideration for these student slots, with the rest of the slots going to other URM students. This worked well, as two of the first BRIDGES students funded by the Harper Scholar award have now received their Ph.D. degree and are in post-doc positions, and a third is expected to defend shortly. However, the combination of the BRIDGES and Harper grant successes have acted as an impetus for the new open enrollment graduate program of the IUSM to recruit and accept more URM students. Indeed, as a result of new IUSM diversity initiatives, the 2009-2010 class had 9 URM students out of a total of 47 (19.1%). We therefore find ourselves in the significantly improved position of now having many more qualified students for the number of Harper slots available, making this a much more competitive program. Being a former BRIDGES Scholar is no longer an automatic qualification for a slot on the Harper grant. Harper Scholars are chosen by the Advisory Committee based on the students’ credentials and recommendation letters, and how well they do while in the IUSM program.

In their first year in graduate training, all IUSM biomedical science Ph.D. students are in a common “open enrollment” scheme. During the year, they do three research rotations as well as coursework. This enables students to have extensive choices in their training and they can choose to focus their interest in topics such as cancer biology, for example, doing rotations with three faculty members with cancer research interests who may be in different programs and departments. Alternately, students can pursue a more traditional path and focus on one traditional discipline (such as biochemistry or microbiology, etc.). The open enrollment mechanism therefore provides an extended, supportive student community, and significant choice. It encourages research collaborations, and it reflects the interdisciplinary nature of modern biomedical research. At the end of the year, the students select a mentor in one of the ten biomedical science Ph.D. programs. At this time, they become the financial responsibility of the Ph.D. program and are typically supported by faculty mentor grants, or NIH training programs, or Department funds. Students are only placed in funded and research productive laboratories. Most faculty must have external peer-reviewed support for their laboratories in order to take a student into the laboratory. This is needed as departments do not have the funds to support all students, and this guarantees the student of being in a laboratory in which the mentors have passed rigorous peer-review themselves. The IUSM strives to give their Ph.D. students the best opportunity to succeed, and having funded and still research-productive mentors is important to this goal. Because the IUSM Dean's Office covers costs of the first year of all Ph.D. students, Harper Scholars are typically chosen to start at the end of their first year in graduate school.

Progress of the Harper Scholars Program

During the first year of support, eight Harper Scholars were selected; six in spring 2007 and two in summer 2007. Of those selected, seven women and one man, five matriculated into the Microbiology and Immunology program (one was co-enrolled in Medical Genetics), two into Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, and one in a combined Cellular & Integrative Physiology Ph.D./M.D. program. In terms of their educational preparation, the students came from a variety of backgrounds, with four receiving their baccalaureates from JSU, one from another HBCU in the South, and three others from large Research I universities in the Midwest and East. The Harper Scholars who came to IUSM from HBCUs were more disadvantaged from a socio-economic and academic perspective, with fewer academic role models within their families and less experience with the rigorous science courses and lab techniques taught at Research I institutions. Of the Harper Scholars, two were the first in their family to graduate from college; four were the first to enter graduate or professional programs. The two who have family members dependent on them are from HBCUs. The Harper Scholars Program provides summer preparatory courses and tutoring to incoming Ph.D. students to help address discrepancies in their academic preparation. Six of the original eight Harper Scholars had summer research experiences at IUSM as undergraduates or Master's students, prior to enrolling in the Ph.D. program. Since the initiation of grant funding for the Harper Scholars Program at the IUSM, there have been 10 Harper Scholars. Six, including two original BRIDGES students have received a Ph.D. degree, with four doing post-doctoral work and one completing the MSTP physician program award. Four new Harper Scholars were chosen by competition to replace those who rotated off the program, including one student who subsequently failed to pass the Qualifying Exam and had to leave the program.

While it is often difficult for schools to attract new URM students until they have reached a critical mass of existing URM students (Hung et al., 2007), the positive outcomes of both the Harper Scholars and BRIDGES programs to date have catalyzed increased efforts and funding to hire underrepresented faculty members at the IUSM: two faculty in Anatomy and Cell Biology, one in Microbiology and Immunology, and one in Cellular & Integrative Physiology.

KEY INTERVENTION STRATEGIES

Literature on broadening the participation of URMs in graduate school science programs identifies several factors that act as barriers, including the level of access to high quality education, a general lack of URM mentors, lack of peer support, insufficient academic preparation, unsuccessful recruitment strategies, and lack of professional development opportunities (Davidson and Foster-Johnson 2001; Summers and Hrabowski 2006). Other studies have been conducted on faculty/student interactions, academic performance, and student perceptions of implicit bias (Beagan 2003; Powell, 2007). To counter such barriers, funding, mentorship, summer research programs, improvement of institutional climate, and access to professional networks are all cited as proven solutions to the successful recruitment, retention, and graduation of URM students in the sciences on both the masters and doctorate levels (Hung et. al. 2007; Pasick et. al, 2003). Major government granting institutions such as the NIH and the National Science Foundation (NSF) have been instrumental in providing several U.S. institutions with the means through which to implement such strategies. Several components of the BRIDGES and Harper Scholars intervention programs in place at IUSM contribute to the progress made to date in the recruitment and retention of URM graduate students. The following is a discussion of these essential elements, which are in line with best practices outlined in the existing literature and which the IUSM has used to adopt a more successful program in which URM students and the school are mutually benefited.

Multi-tiered Mentoring

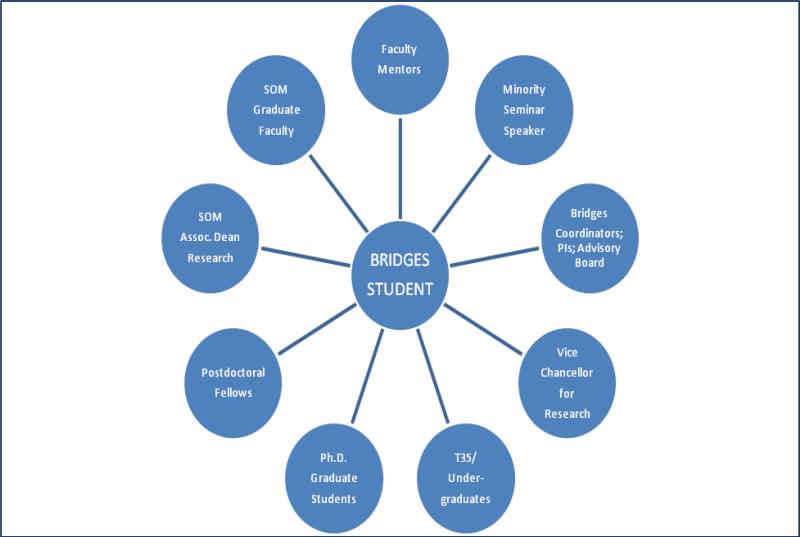

Mentoring is a critical component of any program whose goal is to ensure the persistence of URMs in scientific fields (NSF, 1991). In addition to providing funding for students to gain access to quality education and training, the BRIDGES and Harper programs utilize a multi-tiered approach to mentoring (FIGURE 1). In general, the BRIDGES program serves as a model of “scientific integration,” whereby people from differing institutions (i.e., minority-serving and major institutions) have the opportunity to enter into collaborative relationships (e.g., faculty exchanges; student summer courses) as a means of ensuring quality education (Ricks, 2004). The multi-tiered mentorship model embedded in the IUSM training programs ensures extensive interaction among peer mentors, external role models, faculty preceptors, program administrators, and advisory board members. Meaningful interaction between experienced and aspiring scientists through mentorship, as well as networking and collaboration, is critical for retention of URM students in the sciences (NSF, 1991; Alexander et al., 1998; Davidson and Foster-Johnson 2001). Multi-tiered mentoring also consists of contact among URM students at various levels (i.e., high school, college, medical school students, post-docs).

FIGURE 1.

Example of Multi-Tiered Mentoring for BRIDGES students

External Role Models

URM graduate students at IUSM have also benefited from interactions with nationally- and internally-renowned URM scientists. These scientists of various biomedical career tracks have come to IUSM courtesy of invited lectures and workshops and an annual mentoring symposium. The Harper Scholars program has sponsored five scholars per year, hosted by a range of basic science departments. Harper Scholars participate in graduate student luncheons with these visiting scientists, though all URM students in IUSM are invited. Access to minority mentors is particularly important for students who have come from HBCUs into predominantly white institutions (PWIs) and into programs in which there is underrepresentation of minority students and faculty. Likewise, the Minority Mentoring Symposium sponsored by the BRIDGES program every summer serves as a networking mechanism among URM scholars at all levels (i.e., staff, students, postdoctoral fellows, faculty), within IUSM departments and among undergraduate and other professional schools at the university. External review of the programs illustrate that participating students have consistently rated these mentoring opportunities highly (Foertsch, 2008). These programs are revisited and revised as needed as we receive continue to receive feedback collected by the external reviewer (one of the authors), through her annual evaluation and participation on the Advisory Committees of the grant programs.

Professional Development

The intervention programs at IUSM enable students to have mentorship opportunities not only by inviting outstanding scholars to campus but also by sending students to national and regional conferences. Increased participation at national conferences geared toward URM students has been identified as an important strategy to increase URM retention, graduation, and eventual entry into academic science careers (Davidson and Foster-Johnson 2001; Summers and Hrabowski 2006). Harper Scholars have engaged in recruitment efforts, and have attended annual conferences, national and regional, geared toward URM students which serve as professional development and networking opportunities. Conference participation allows students the opportunity to network and enter into mentoring relationships with senior researchers beyond their campus confines, to ensure their eventual entry into academic science careers (Powell, 2007).

Multiple Funding Paths

The synergy that is created through the combination of mentorship, professional development and the various funding paths at IUSM (i.e., BRIDGES, Harper's T32, T35) lies at the heart of attaining our overall goals of attracting, recruiting, retaining and graduating URM students. Students in these programs interact with one another in classrooms, laboratories, and workshops, while having ongoing contact with research and clinical fellows, and faculty. This facilitates continuity of training and mentoring. Through the long-standing T35 program, IUSM has trained six fellows, two of whom have gone on to pursue careers in academic medicine. In addition, four former T35 students have achieved the Ph.D. (3 from IUSM); while 11 others are currently in doctoral programs (8 of these at IUSM). The T35 program, in existence at IUSM since 1994, has trained on average 15 students per year. It has served as an entry point of the pipeline in biomedical research for URM students and as a foundation for all subsequent programs, thus contributing to the overall collective effort made by the IUSM training programs toward enhancing and diversifying the future scientific workforce.

A well-established metric of student success in biomedical research is authorship on research papers in peer-reviewed scientific or clinical journals. By that criterion, our Harper Scholars have done well; to date, they have co-authored or first authored over 23 peer-reviewed articles with 3 scholars in the process of preparing manuscripts for submission.

Interactions in these programs of URM students at various educational levels (i.e., high school, college, medical school students, postdoctoral fellows) with students currently pursuing the Ph.D. facilitate an environment where expectations of the Ph.D. as a career goal become more explicit. Similarly, Ph.D. students serving as informal mentors and role models for the T35 and other pre-doctoral students, have their own confidence reinforced in terms of their career development.

CHALLENGES AND IMPLICATIONS FOR FUTURE STUDY

Despite the best efforts of institutions like IUSM who are implementing intervention strategies, underrepresentation in the biomedical sciences continues to exist. One concern is the matter of URM scientists not entering into professional positions despite an apparent rise in acquisition of the Ph.D. (Nelson 2007; Powell 2007). Moreover, many of the brightest students seem to gravitate towards medical school. While this is clearly a noteworthy endeavor, we must find ways to entice and recruit the best and most motivated students into healthcare-related graduate programs. These and other challenges remain and should guide further study of the efficacy of intervention programs whose aims are to ultimately increment and diversify the biomedical scientific workforce.

There are several factors that explain why the efforts undertaken by IUSM have been successful thus far. Implementation elsewhere may or may not yield similar results. While none of these components of intervention are particularly novel, it is important to present them here as a means of sharing best practices. There needs to be more scholarly conversations had on “what does or does not work” in the efforts put forth to redress the apparent disparity in URMs in the biomedical training pipeline.

Recruitment

Aggressive and intentional recruitment efforts alongside increased funding support are critical in attracting and matriculating qualified URM graduate students (Hung et. al. 2007). The IUSM has found that the intentional recruitment of URM students is most successful when responsibility is shared between partnering institutions. However, even when institutional partnerships have been established, the pool of potential participants should be broadened; institutions should still seek out URM students who may be already participating in other initiatives or programs on their campuses, or nationally in programs that have enjoyed notable success (e.g., Myerhoff Scholars Program; Maton and Hrabowski, 2004). Aggressive recruitment also calls for a stronger faculty presence at recruitment fairs; the task of recruiting potential URM students should not fall solely on one administrative office.

Efforts by our IUSM include a dedicated staff member for recruitment with specific goals in URM recruitment and diversity, annual attendance at conferences such as Annual Biomedical Research Conference for Minority Students (ABRCMS) and the Society for the Advancement of Chicanos and Native Americans (SACNAS) with extensive follow up and communications, targeted mailings to HBCU students and URM students who have taken the GRE, describing our graduate and diversity programming, a visiting seminar speaker series for HBCUs, an ambassador program whereby our URM students return to their alma maters to describe our programs, dedicated diversity web pages, and application fee waivers for URM students. In recent years, the IUSM has developed a Diversity Office and an Office of Multicultural Affairs. Further, IUPUI has developed an Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. Our IUSM diversity graduate recruitment efforts have been in productive synergy with these offices. Students who are selected for interview specifically meet with our URM students and faculty and those who have been made an offer are invited back for a “second look” program with other URM applicants. Several IUSM faculty also are on the Minority Affairs Committees of national US research societies.

Recruitment of URMs into the biomedical sciences pipeline must also occur earlier, at the undergraduate level (and some would argue earlier). Institutions providing increased undergraduate research opportunities have produced positive outcomes to that end (Hung et al., 2007). For example, in a 2007 survey of over 7800 undergraduates, Russell, Hancock and McCullough concluded that those undergraduates who had exposure to undergraduate research reported the following: increased understanding of how to conduct a research project; increased confidence in research skills; increased awareness of what graduate school is like; clarified interests in Science, Technology, Engineering or Mathematics (STEM) careers; and increased anticipation of acquiring a Ph.D. These positive student outcomes for undergraduates who had access to hands-on research opportunities and professional development activities (e.g., conference presentations; publications) are multiple, and yield important considerations for graduate studies.

Finally, there is the issue of institutions trying to attract high-ability URM students into their programs. The challenge is not simply a matter of multiple institutions competing for the most high performing, driven and career-focused students; it is the need for institutions to reconsider an alternative framework, one where they would consider admitting students who are not as “qualified” in terms of their previous academic preparation, but who exhibited a strong desire and commitment to complete the Ph.D. This is where we believe the IUSM has carved out a niche for itself. These are the students who IUSM have targeted and who continue to matriculate into and graduate from our programs. Institutions must be more open to the idea of “developing” URM scientists, which inevitably takes more time, may present greater risk, but which may yield positive results in the end.

Competition for students at predominately URM-training institutions

One problem we came across in our efforts to recruit the best students at JSU is that the BRIDGES program sponsored by the NIH paid about $7000 less per year than a comparable program at our partner institute funded by the National Sciences Foundation (NSF). This discrepancy made it extremely difficult in recruiting the best students at this institute into the BRIDGES program. It is not clear how to deal with this problem, which is specific to an HBCU that has both an NIH and an NSF BRIDGES program, other than extensive recruitment efforts to best describe our supportive and collaborative environment to applicants, as noted above.

Mentors

Even when institutions develop programs to address underrepresentation, they may still encounter difficulty in identifying experienced and willing mentors. In the Executive Summary of a 1991 National Science Foundation (NSF) report, workshop participants stated the following: “Mentorship is more than just teaching. It combines personal involvement, commitment, attainment of goals, and follow-up.” It continues by stating that “[e]ffective mentoring, however, demands both time and energy. Unfortunately, because success in academic science is often measured by grant dollars and numbers of published papers, the incentive to engage in mentorship activities has been substantially reduced” (NSF 1991). The culture of science is often implicated in this dilemma. URM graduate students often face an environment in which research agendas may take precedence over interventions that require greater time and flexibility (e.g., more mentoring time).

Increased government funding for URM graduate students has helped to address this dilemma, with faculty acquiring protégés who in turn facilitate their research productivity. In our experience, the Harper grant has been instrumental in convincing high level research investigators to recruit URMs into their laboratory, with subsequent realization that these students have contributed productively to the success of the lab. In addition, mentorship can be enhanced through financial support to URM faculty, who could free up some of their time needed to engage in the process of developing URM scholars more aggressively (NSF 1991).

With increases in graduation rates over time and the active promotion of positive outcomes, programs receiving funding for URM students will have a greater ability to attract more experienced and willing mentors (Reichert, 2006). In addition, it is the role of the campus administrators and department chairs to highlight the positive contributions made by URM graduate students to their faculty's laboratories. Providing this type of feedback illustrates “working examples” for faculty who may be resistant or reluctant to participate in such initiatives, often perceived as taking more time and effort away from their research (Reichert 2006). An effective means at dispelling such a myth is to highlight the laboratory accomplishments at a yearly symposium. Here, the students present their work in poster sessions and have the opportunity to interact with a number of faculty members. These activities are also effective at enhancing the students’ self-confidence.

Institutional Climate

Programs seeking to retain URM graduate students must also consider the overall institutional climate. Differences in perception among majority and minority students regarding institutional climate for diversity must figure into program design and implementation (Hung et al., 2007). Understanding the differences between institutions considers the shift of URM students from the nurturing environment of an HBCU, for example, to one of individualism and intense competition at a PWI (Louis, et. al. 2007). URM students at PWIs may encounter isolation or feel “singled out” as a representative of an entire racial/ethnic group which could lead to performance vulnerability related to low expectations, lack of peer support, and discrimination (Beagan 2003; Hung et al., 2007; Nettles, 1990; Summers and Hrabowski, 2006). In our experience, a “critical mass” of URM students can serve as peer mentors, helping to reduce (or even prevent) such isolation. Even with that, an institution needs to demonstrate its commitment to diversity by who it brings into their leadership roles. IUPUI has an Assistant Chancellor for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, and IUSM recently recruited an Associate Dean for Diversity Affairs. Both of these administrators are African-American, as is the new IUSM Executive Associate Dean for Research.

The creation of campus initiatives to support equity and diversity has become a key element in providing students with institutional support for their success. The IUSM Graduate Office, in close collaboration with the IUPUI Graduate Office, the IUSM Diversity Office, the IUSM Office of Multicultural Affairs, and the IUPUI Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, has developed a series of events to promote cohort building, community reinforcement, and to facilitate the self-selection of optimal mentors. These include an annual off campus retreat, The Graduate and Postdoctoral Fellow Workshop. The purpose of this event is to: a) to provide URM students, and thus majority students, with an increased level of satisfaction at the IUSM during graduate studies; b) to gain from students knowledge of what improvements can be made and an assessment of IUSM strengths and weaknesses with regard to diversity issues amongst graduate students; c) to identify ways work together to address challenges and opportunities. The overall objective of this event is to create a diversity survey to baseline graduate student perception (via survey evaluation) of the IUSM environment as it pertains to diversity, to identify strengths and weaknesses that can be utilized to create strategies and programming that will increase URM recruitment, retention, and alumni engagement. The Graduate and Postdoctoral Fellow Workshop rotates annually with another event entitled Getting You Through, a workshop designed to provide helpful hints, tools, and resources to underrepresented minorities pursing a doctoral degree at the IUSM.

Industry

Financial matters related to the cost of education are compounded for URM students who may experience economic disadvantage and/or if they are having to contend with assuming financial responsibility for immediate and extended family in the midst of acquiring their education. As mentioned earlier, this is certainly the case for many of our BRIDGES and Harper students. In the end, many URM graduate students may pursue industry positions for financial security, in the wake of having to pay back large student loans (Powell 2007:98). This can even lead students away from the entry levels of academia, the post docs. Industry becomes a lure for students because of higher starting salaries and a more regular work week (i.e., 40 hours) (Powell 2007). One solution to increase retention and entry into academia instead of industry is increased participation at national conferences geared toward URM students, particularly in specific fields. This allows students the opportunity to network and enter into mentoring relationships with senior researchers beyond their campus confines (Powell 2007). Recruitment at these venues is critical. In our experience in the IUSM, the substantial number of opportunities for students to present their work at national (and even international) scientific conferences provides great incentive to pursue postdoctoral training. The majority of our URM graduate students have travelled down that path.

Other solutions include matching industry offers, better spousal hire incentives and cluster hiring. At collaborative programs for URM students, such as the Graduate and Postdoctoral Fellow Workshop and Getting You Through programs described above, many of the key speakers are senior URM students and postdoctoral fellows who are pursuing the academic track. The campus also has a very active Preparing Future Faculty program that has a strong record of diversity and all IUSM graduate students are encouraged to participate in this program.

CONCLUSION

The information presented here is intended to provide a baseline account of the progress of the IUSM intervention programs; the authors contend that it is still too early to adequately access the relative successes of such interventions. However, the programs have made significant strides towards achieving their stated goals and those of the NIGMS and NCMHD to increase the numbers of URM students in the biomedical training pipeline. The success of BRIDGES is based upon the theory that many URM students who pursue terminal masters degrees have the potential to complete Ph.D. degrees in the biomedical sciences. With sufficient financial support, rigorous curricula, extensive research experiences, and committed mentors, these students will transition successfully to doctoral study. The success of the Harper Scholars program is conjoined by the goals of the BRIDGES, in bringing the process of transition to fruition.

Simply having a program in place does not guarantee success. Current assessments of intervention programs like BRIDGES and the Harper Scholars Program have tended to measure success based on academic performance, graduation rates, and the acquisition of postdoctoral and professional/independent research positions upon completion of training. Beyond program assessment and evaluation, however, there is a critical need for more studies that would determine which components of a given program are more successful than others in achieving the goal of increased training of URM graduate students in the biomedical sciences. Dynamic strategies need to be employed in dynamic ways in order to enhance the potential for success. The current progress of the IUSM intervention programs suggests the following as key strategies that should be considered in the development of any program targeting URM students:

Summer research opportunities

Multiple funding paths (Peer-reviewed through NIH and other funding agencies, combined with that from departments and the school)

Multi-tiered mentoring and peer support

Strong and committed Advisory Committee

Educational and professional development opportunities

Strong institutional partnerships

The intentional and synergistic effort of targeting underrepresented and economically disadvantaged individuals to specific training programs in IUSM have benefited more students than just those receiving NIH funding. The individual elements combining financial support, a critical mass of students, pre-graduate school research preparation, multi-tiered mentoring, and tutoring have resulted in increased enrollment, retention and graduation among all URM students in IUSM. These interventions have also resulted in increased efforts and funding to recruit URM faculty members at the institutional level.

Our goal is to establish productive partnerships with institutions who share the same commitment to providing outstanding educational opportunities to promising young URM scientists, and to work together to increase diversity in science. While the IUSM is happy with the successes, it is not satisfied. Improvement in the recruitment, retention and graduation of URM students is an ongoing effort. In the end, it is not just the students, IUSM or the partner institutions who win—it is all of us.

We and our students have benefited immensely from the vision of the NIH to fund programs for URM students. Funding in the current economic atmosphere is challenging, but we suggest that the NIH and other peer-review granting agencies not only resist reducing their funding for training URM students, but work to increase this funding which is critical to addressing underrepresentation in the biomedical sciences.

Acknowledgments

The Bridges to the Doctorate (NIH-NIGMS R25 GM065792) and the Initiative for Maximizing Graduate Student Diversity (NIH-NIGMS R25 GM79657-01) programs described here were supported by the National Institute of General Medicine Sciences. The T32 research training programs (DK007519-24; AI060519-05; CA111198-04; CA111198-04S1; HL07910-09) were supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, and the National Cancer Institute. The F31 NRSAs (CA106215-05; CA130115) were supported by the National Cancer Institute. The T35 short term training program for minority students (HL007802) was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Contributions from the administrative staff and faculty from participating departments are acknowledged with appreciation.

References

- Alexander BB, Foertsch J, Daffinrud S. The Spend a Summer with a Scientist Program: An Evaluation of Program Outcomes and the Essential Elements for Success. LEAD Center; UW-Madison: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Beagan BL. ‘Is this Worth Getting into a Big Fuss Over?’ Everyday Racism in Medical School. Medical Education. 2003;37:852–860. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capomacchia AC, Garner ST. Challenges of Recruiting American Minority Graduate Students: The Coach Model. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 2004;68(4):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Chang MJ, Cerna O, Han J, Sàenz V. The Contradictory Roles of Institutional Status in Retaining Underrepresented Minorities in Biomedical and Behavioral Science Majors. The Review of Higher Education. 2008;31(4):433–464. [Google Scholar]

- Claudio L. NIEHS News: Making More Minority Scientists. Environmental Health Perspectives. 1997;105(2):174–176. doi: 10.1289/ehp.97105174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson MN, Foster-Johnson L. Mentoring in the Preparation of Graduate Researchers of Color. Review of Educational Research. 2001;71(4):549–574. [Google Scholar]

- Fagen AP, Labov JB. Understanding Interventions that Encourage Minorities to Pursue Research Careers: Major Questions and Appropriate Methods. CBE—Life Sciences Education. 2007;6:187–189. doi: 10.1187/cbe.07-06-0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foertsch J. Year One of the Harper Scholars Program: The Evaluator's Annual Update on Student Progress, Satisfaction, and Factors in Persistence: March 2008. 2008 Unpublished report. [Google Scholar]

- Henly SJ, Struthers R, Dahlen BK, Ide B, Patchell B, Holtzclaw BJ. Research Careers for American Indian/Alaska Native Nurses: Pathway to Elimination of Health Disparities. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(4):606–611. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.054239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill RD, Castillo LG, Ngu LQ, Pepion K. Mentoring Ethnic Minority Students for Careers in Academia: The WICHE Doctoral Scholars Program. The Counseling Psychologist. 1999;27:827–845. [Google Scholar]

- Hung R, McClendon J, Henderson A, Evans Y, Colquitt R, Saha S. Student Perspectives on Diversity and the Cultural Climate at a U.S. Medical School. Acad. Med. 2007;82(2):184–192. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31802d936a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landefeld T. Minorities in Science. Mentoring and Diversity: Tips for Students and Professionals for Developing and Maintaining a Diverse Scientific Community. (1st Ed.) New York: Springer. (1st Ed.) 2009:19–43. [Google Scholar]

- Leggon CB, Pearson W. BA Origins of African American Female Ph.D. Scientists. Journal of Women and Minorities in Science and Engineering. 1997;3:213–224. [Google Scholar]

- Louis KS, Holdsworth JM, Anderson MS, Campbell EG. Becoming a Scientist: The Effects of Work-Group Size and Organizational Climate. The Journal of Higher Education. 2007;78(3):311–336. [Google Scholar]

- Maton KI, Hrabowski FA., III Increasing the Number of African American Ph.D.s in the Sciences and Engineering: A Strengths-Based Approach. American Psychologist. 2004;59(6):547–556. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.6.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millett CM, Nettles MT. Expanding and Cultivating the Hispanic STEM Doctoral Workforce: Research on Doctoral Student Experiences. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education. 2006;5(3):258–287. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell DA, Lassiter SL. Addressing Health Care Disparities and Increasing Workforce Diversity: The Next Step for the Dental, Medical, and Public Health Professions. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(12):2093–2097. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.082818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Science Foundation . Diversity in Biological Research: NSF Workshop Report. National Science Foundation; Washington, D.C.: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DJ. [June 2, 2008];A National Analysis of Minorities in Science and Engineering Faculties at Research Universities. 2007 from http://chem.ou.edu/~djn/diversity/Faculty_Tables_FY07/Final Report07.html.

- Nettles MT. Success in Doctoral Programs: Experiences of Minority and White Students. American Journal of Education. 1990;98(4):494–522. [Google Scholar]

- Pasick RJ, Otero-Sabogal R, Nacionales MCB, Banks PJ. Increasing Ethnic Diversity in Cancer Control Research: Description and Impact of a Model Training Program. J. Cancer Ed. 2003;18(2):73–77. doi: 10.1207/S15430154JCE1802_07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell K. Special Report: Beyond the Glass Ceiling. Nature. 2007;448:98–100. [Google Scholar]

- Reichert WM. A Success Story: Recruiting & Retaining Underrepresented Minority Doctoral Students in Biomedical Engineering. [July 17, 2008];Liberal Education, 92. 2006 from http://eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_01/0000019b/80/2a/cd/ac.pdf.

- Ricks I. The 50th Anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education: Continued Impacts on Minority Life Science Education. Cell Biol. Educ. 2004;3(3):146–149. doi: 10.1187/cbe.04-05-0044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochin RI, Mello SF. Latinos in Science: Trends and Opportunities. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education. 2007;6(4):305–355. [Google Scholar]

- Russell SH, Hancock MP, McCullough J. The Pipeline: Benefits of Undergraduate Education. Science. 2007;316:548–549. doi: 10.1126/science.1140384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solorzano DG. The Doctorate Production and Baccalaureate Origins of African Americans in the Sciences and Engineering. The Journal of Negro Education. 1995;64(1):15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Stassun KG, Burger A, Lange SE. The Fisk-Vanderbilt Masters-to-Ph.D. Bridge Program: A Model for Broadening Participation of Underrepresented Groups in the Physical Sciences through Effective Partnerships with Minority-Serving Institutions. [August 14, 2009];Journal Geophysical Education. 2008 (in press). from http://people.vanderbilt.edu/~keivan.stassun/pubs.htm.

- Summers MF, Hrabowski FA., III Preparing Minority Scientists and Engineers. Science. 2006;311:1870–1871. doi: 10.1126/science.1125257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syverson PD, Bagley LR. Graduate Enrollment and Degrees, 1986-1997. Council of Graduate Schools; Washington, D.C.: 1999. [Google Scholar]