Abstract

Objective

Social support may be associated with improved diet and physical activity—determinants of overweight and obesity. Wellness programs increasingly target worksites. The aim was to evaluate the relationship between worksite social support and dietary behaviors, physical activity, and body mass index (BMI).

Method

Baseline data were obtained on 2,878 employees from 2005 to 2007 from 34 worksites through Promoting Activity and Changes in Eating, a group-randomized weight reduction intervention in Greater Seattle. Worksite social support, diet, physical activity, and BMI were assessed via self-reported questionnaire. Principal components analysis was applied to workgroup questions. To adjust for design effects, random effects models were employed.

Results

No associations were found with worksite social support and BMI, or with many obesogenic behaviors. However, individuals with higher worksite social support had 14.3% higher (95% CI: 5.6%-23.7%) mean physical activity score and 4% higher (95% CI: 1%–7%) mean fruit and vegetable intake compared to individuals with one-unit lower support.

Conclusion

Our findings do not support a conclusive relationship between higher worksite social support and obesogenic behaviors, with the exception of physical activity and fruit and vegetable intake. Future studies are needed to confirm these relationships and evaluate how worksite social support impacts trial outcomes.

Introduction

Social support is associated with nutritious diets and physical activity—determinants of overweight and obesity (Fuemmeler et al., 2006; Hemmingsson et al., 2008; Quintiliani et al., 2007). Studies have examined the impact that friend and familial support have on health outcomes (Untas et al., 2010); yet, few have also assessed the role of co-worker social support (Beresford et al., 2007; Elliot et al., 2004). The social context in which individuals make lifestyle choices has become increasingly important at the worksite. Still, few worksite wellness programs include a social support component (Quintiliani et al., 2007). Hence, little is known about the influence that worksite social support may have on lifestyle factors. In addition, earlier studies have examined the relationship between aspects of the worksite social context and health behaviors (Elliot et al., 2004; Sorensen et al., 2007); but, to our knowledge, none has studied the association between this precise measure capturing a general sense of co-worker support and similar outcomes. Thus, this study aims to inform the development of more successful obesity prevention interventions at the worksite by evaluating the relationship between general worksite social support and dietary and physical activity behaviors, and body mass index (BMI).

Methods

We analyzed baseline data obtained on 2,878 employees from 2005 to 2007 from 34 worksites through Promoting Activity and Changes in Eating (PACE), a group randomized weight reduction intervention in the Greater Seattle area (Beresford et al., 2007). The PACE study is described elsewhere (Beresford et al., 2007).

Our independent variable was worksite social support—created using five adapted employee-workgroup questions focused on perceived general support (Elliot et al., 2004). The social support score was developed using principal components analysis, which loaded highly on three of the five questions (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.77). Our dependent variables included diet, physical activity, and BMI. Diet was assessed using validated indices of obesogenic behaviors (Liebman et al., 2003); questions included servings of fruits and vegetables (single question and summary food frequency questions) (Thompson and Byers, 1994), fast food restaurant meals (Pereira et al., 2005), regular soft drink consumption (French et al., 2000), and eating while doing other activities (Liebman et al., 2003). Physical activity measurements included a computed metabolic equivalent score, and a question measuring workout intensity (Godin and Shephard, 1985). BMI was computed using self-reported weight (kg) and height (meters).

The study design included individuals clustered within worksites, and the continuous outcomes were highly right-skewed; thus, we employed Linear Mixed Models using log-transformed dependent variables. For categorical outcomes, we used Logistic Mixed Models. All analyses were performed in STATA version 10. Individuals were the unit of analysis. Worksites were used as the random effect and fixed effects included worksite social support, gender, age, education, and race/ethnicity. We report model mean ratios (continuous outcomes) or odds ratios (categorical outcomes) and 95% confidence intervals. All p-values reported are from Wald tests.

Results

Descriptive results (not shown) indicate that the sample had a mean age of 42 years and 51% were female (Beresford et al., 2007). Forty-two percent of participants were high school graduates or General Educational Development recipients. Finally, 77% of participants self-identified as White. A majority of employees agreed or strongly agreed with each of the questions included in the worksite social support measure, indicating a high level of worksite social support. Nonetheless, 9–13% of participants reported low levels of support.

Table 1 summarizes outcome measures and displays the regression model results for worksite social support. Mean BMI was 27.4 kg/m2. Individuals were more likely to engage in mild intensity leisure time exercise (73%), compared to vigorous or moderate (not shown). The continuous physical activity score had a mean of 31.1 (s.d. 30.5)—the equivalent of engaging in strenuous physical activity for 10 minutes, 3.4 times/week. Thirty percent of participants never/rarely engaged in sweat producing exercise. The average intake of fruits and vegetables via both questions was approximately 3 servings per day. On average, participants ate fast food meals 2.3 times per month. The mean intake of soda was 3.5 cans per week. Only 21% of participants never/seldom ate while doing other activities.

Table 1.

Outcome summaries and estimated effect of worksite social support on body mass index, physical activity, and dietary behaviors of employees at PACE worksites (Greater Seattle, WA, 2005–2007)

| (N = 34 Worksites) (n = 2,568 Individuals)a |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression Results |

|||||||

| Outcome Summaries | Worksite Adjusted Resultsb | Fully Adjusted Resultsc | |||||

| Mean (s.d.) | Mean Ratio/ (Odds Ratio)d |

95% C.I. | Pe | Mean Ratio/ (Odds Ratio)d |

95% C.I. | Pe | |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 27.4 (6.2) | 0.99 | (0.98, 1.01) | 0.24 | 0.990 | (0.98, 1.00) | 0.14 |

| Physical Activity | |||||||

| Leisure time exercise f | 31.1(30.5) | 1.14 | (1.05, 1.23) | 0.00 | 1.140 | (1.06, 1.24) | 0.001 |

| Sometimes/often engaging in sweat producing exercise |

70% | (1.03)d | (0.84, 1.26) | 0.80 | (1.01)d | (0.85, 1.20) | 0.90 |

| Dietary Behaviors | |||||||

| Fruits and vegetables g | 3 (1.7) | 1.03 | (0.99, 1.06) | 0.09 | 1.020 | (0.99, 1.05) | 0.19 |

| Fruits and vegetables h | 3.1 (2.2) | 1.05 | (1.01, 1.09) | 0.02 | 1.040 | (1.01, 1.07) | 0.046 |

| Fast food restaurant meals i | 2.3 (3.2) | 0.98 | (0.94, 1.03) | 0.48 | 1.000 | (0.96, 1.05) | 0.93 |

| Soft drink consumption j | 3.5 (4.9) | 0.98 | (0.92, 1.05) | 0.59 | 0.990 | (0.92, 1.06) | 0.72 |

| Sometimes/most times/always eating while doing other activities |

79% | (0.92)d | (0.81, 1.05) | 0.22 | (0.89)d | (0.74, 1.07) | 0.22 |

Study location: Greater Seattle area; time of data collection: 2005–2007

Note. For continuous outcomes, mean ratio is interpreted as a ratio of outcomes comparing two individuals, one unit apart in worksite social support.

The social support score ranges from 1 to 4, where 1 = low social support and 4 = high social support.

"n" = 2,568 is the number of individuals who are a complete case for at least one regression model, "n" varies per outcome (range 2,436–2,568).

Linear Mixed Models with log-transformed dependent variable or Logistic Mixed Models used, adjusted for worksites.

Linear Mixed Models with log-transformed dependent variable or Logistic Mixed Models used, adjusted for worksites, gender, age, education, and race/ethnicity.

These results reflect odds ratios from a logistic random effects model.

P-value for test of no association between worksite social support and each outcome.

Leisure time exercise assessed using Godin MET score, representing the physical activity score.

Single question; per day

Summary food frequency questions; per day

Per month

Per week

Adjusted analyses revealed no significant relationships between worksite social support and BMI, or many of the obesogenic behaviors. However, physical activity score (p = 0.001) and fruit and vegetable intake-summary food frequency questions (p = 0.046) were significantly associated with worksite social support.

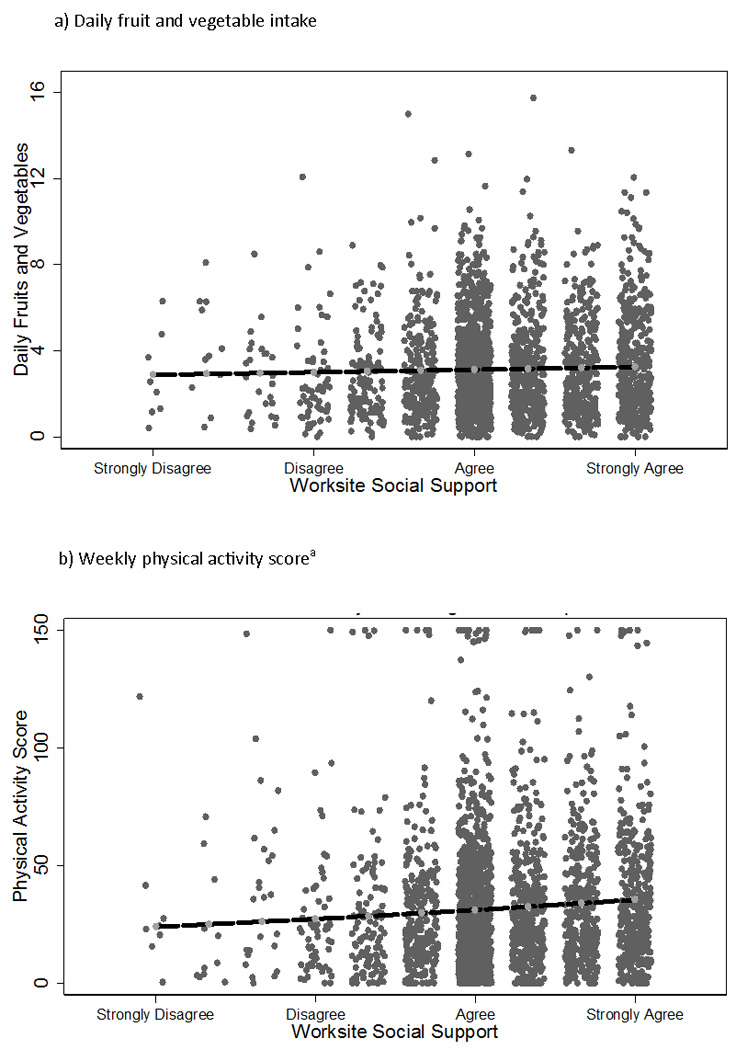

Figure 1 shows scatter plots for fruit and vegetable intake and physical activity score across the worksite social support spectrum, with the adjusted regression slope overlaid. An individual with the highest worksite social support ate 0.36 more servings of fruits and vegetables daily and reported one extra 10-minute session each of strenuous and light physical activity weekly.

Figure 1.

Association between worksite social support and (a) fruit and vegetable intake and (b) physical activity score in Greater Seattle area 2005–2007, with adjusted regression slope overlaid.

Footnotes: Worksite social support scale ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree); regression slope is pegged to the crude mean for persons with a worksite social support score of 3 (the mode response). We adjusted for skewness by using a log transformation, which dampens the impact of outliers, and deletion diagnostics showed that the strength and site of the associations increased when the top three values were deleted. "Physical activity score represents a computed metabolic equivalent score (higher scores represent greater levels of physical activity), which encompasses regularity of free-time physical activity.

Discussion

In this study, we created a general, non-behavior specific support measure to assess whether an overall feeling of co-worker support was associated with healthier dietary behaviors, physical activity, and BMI. Though all relationships analyzed were in the direction hypothesized, we observed mostly null findings, with the exception of fruit and vegetable intake and physical activity score, which were significantly associated with higher worksite social support. This may suggest that, like behavior specific support, a generally supportive work environment may have potential to marginally impact select health behaviors (Quintiliani et al., 2007; Sorensen et al., 2004).

Despite two statistically significant findings, the effect sizes attributable to social support in this study are not overwhelming, so positing clinical significance is debatable (Jacobson and Truax, 1991). We argue, however, that these findings suggest that worksite social support may be a meaningful determinant of fruit and vegetable intake and physical activity. Similar to our results, several studies contend that effect sizes close to 0.36 daily fruits and vegetables and small differences in physical activity are clinically meaningful (Bodor et al., 2008; Cheadle et al., 2010; Hill et al., 2003; Langenberg et al., 2000; Sorensen et al., 2007; Stables et al., 2005; Yancey et al., 2006). At baseline, disparities in fruit and vegetable intake and physical activity scores existed across the worksite social support spectrum. These disparities may suggest opportunities for interventions to improve specific health behaviors by targeting the social context (Quintiliani et al., 2007; Sorensen et al., 2007), and may have implications for population-level public health (Cheadle et al., 2010; Hill et al., 2003).

Since achieving energy balance through healthier physical activity and diet is critical in maintaining or reducing BMI, if evaluated longitudinally, worksite social support may foster small improvements in individual health behaviors and, in turn, BMI. Our baseline results show that participants reporting lower levels of support have, on average, poorer fruit and vegetable intake and physical activity scores compared to those reporting higher social support. Thus, worksite wellness programs might consider targeting individuals with lower co-worker support, thereby creating prospects for even greater improvements in health behavior change.

A first limitation of this study is the difficulty in making a causal inference between worksite social support and health-related outcomes using a cross-sectional study design. Additionally, the results may have limited generalizability due to the worksites’ geographic location, size, and participant socio-demographics. Given that the data were derived by way of self-report, social desirability may have played a role. One of the major strengths of this study is that, to our knowledge, this is the first study examining the association between a general sense of co-worker support and diet, physical activity, and BMI. Moreover, by engendering an innovative general worksite social support score that is non-behavior specific, we provided a novel perspective on worksite social support.

Conclusion

Further studies, ideally longitudinal ones that study changes in outcomes and behaviors, are needed to clarify the relationship and magnitude of association between worksite social support and health behaviors associated with obesity. Qualitative studies may be useful adjuncts to quantitative studies, in enhancing our understanding of the complex relationships between personal and worksite characteristics and how they influence social support and its impact on select behaviors. Such studies may have modest implications for the design and implementation of more successful worksite obesity prevention trials.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to acknowledge the training and support of the University of Washington’s Department of Health Services as well as the NCI’s Biobehavioral Cancer Prevention and Control Fellowship Grant (R25 CA92408; PI: Donald Patrick, PhD) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant (R01 HL079491; PI: Shirley Beresford, PhD).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors confirm that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Beresford S, Locke E, Bishop S, West B, McGregor B, Bruemmer B, Duncan G, Thompson B. Worksite Study Promoting Activity and Changes in Eating (PACE): Design and Baseline Results. Obesity. 2007;15:4S–15S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodor JN, Rose D, Farley TA, Swalm C, Scott SK. Neighbourhood fruit and vegetable availability and consumption: the role of small food stores in an urban environment. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11:413–420. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007000493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheadle A, Samuels SE, Rauzon S, Yoshida SC, Schwartz PM, Boyle M, Beery WL, Craypo L, Solomon L. Approaches to measuring the extent and impact of environmental change in three California community-level obesity prevention initiatives. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:2129–2136. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot DL, Goldberg L, Duncan TE, Kuehl KS, Moe EL, Breger RK, DeFrancesco CL, Ernst DB, Stevens VJ. The PHLAME firefighters' study: feasibility and findings. Am J Health Behav. 2004;28:13–23. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.28.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French SA, Harnack L, Jeffery RW. Fast food restaurant use among women in the Pound of Prevention study: dietary, behavioral and demographic correlates. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:1353–1359. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuemmeler B, Masse L, Yaroch A, Resnicow K, Campbell M, Carr C, Wang T, Williams A. Psychosocial mediation of fruit and vegetable consumption in the body and soul effectiveness trial. Health Psychol. 2006;25:474–483. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.4.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godin G, Shephard RJ. A simple method to assess exercise behavior in the community. Can J Appl Sport Sci. 1985;10:141–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmingsson E, Hellenius M, Ekelund U, Bergstrom J, Rossner S. Impact of social support intensity on walking in the severely obese: a randomized clinical trial. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:1308–1313. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JO, Wyatt HR, Reed GW, Peters JC. Obesity and the environment: where do we go from here? Science. 2003;299:853–855. doi: 10.1126/science.1079857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:12–19. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenberg P, Ballesteros M, Feldman R, Damron D, Anliker J, Havas S. Psychosocial factors and intervention-associated changes in those factors as correlates of change in fruit and vegetable consumption in the Maryland WIC 5 A Day Promotion Program. Ann Behav Med. 2000;22:307–315. doi: 10.1007/BF02895667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebman M, Pelican S, Moore SA, Holmes B, Wardlaw MK, Melcher LM, Liddil AC, Paul LC, Dunnagan T, Haynes GW. Dietary intake, eating behavior, and physical activity-related determinants of high body mass index in rural communities in Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:684–692. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira MA, Kartashov AI, Ebbeling CB, Van Horn L, Slattery ML, Jacobs DR, Jr., Ludwig DS. Fast-food habits, weight gain, and insulin resistance (the CARDIA study): 15-year prospective analysis. Lancet. 2005;365:36–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17663-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintiliani L, Sattelmair J, Sorensen G. The workplace as a setting for interventions to improve diet and promote physical activity, Dalian/China. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen G, Linnan L, Hunt MK. Worksite-based research and initiatives to increase fruit and vegetable consumption. Prev Med. 2004;39 Suppl 2:S94–S100. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen G, Stoddard AM, Dubowitz T, Barbeau EM, Bigby J, Emmons KM, Berkman LF, Peterson KE. The influence of social context on changes in fruit and vegetable consumption: results of the healthy directions studies. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1216–1227. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.088120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stables GJ, Young EM, Howerton MW, Yaroch AL, Kuester S, Solera MK, Cobb K, Nebeling L. Small school-based effectiveness trials increase vegetable and fruit consumption among youth. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:252–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson FE, Byers T. Dietary assessment resource manual. J Nutr. 1994;124:2245S–2317S. doi: 10.1093/jn/124.suppl_11.2245s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Untas A, Thumma J, Rascle N, Rayner H, Mapes D, Lopes AA, Fukuhara S, Akizawa T, Morgenstern H, Robinson BM, Pisoni RL, Combe C. The Associations of Social Support and Other Psychosocial Factors with Mortality and Quality of Life in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010 doi: 10.2215/CJN.02340310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancey AK, Lewis LB, Guinyard JJ, Sloane DC, Nascimento LM, Galloway-Gilliam L, Diamant AL, McCarthy WJ. Putting promotion into practice: the African Americans building a legacy of health organizational wellness program. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7:233S–246S. doi: 10.1177/1524839906288696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]