Abstract

Although the structure of the molecular chaperone Hsp90 has been extensively characterized by X-ray crystallography, the nature of the interactions between Hsp90 and its client proteins remains unclear. We present results from a series of spectroscopic studies that strongly suggest that these interactions are highly dynamic in solution. Extensive NMR assignments have been made for human Hsp90, through the use of specific isotopic labeling of one- and two-domain constructs. Sites of interaction of a client protein, the p53 DNA-binding domain (DBD) were then probed both by chemical shift mapping and by saturation transfer NMR spectroscopy. Specific spectroscopic changes were small and difficult to observe, but were reproducibly measured for residues over a wide area of the Hsp90 surface, in the N-terminal, middle and C-terminal domains. A somewhat greater specificity, for the area close to the interface between the N-terminal and middle domains of Hsp90, was identified in saturation transfer experiments. These results are consistent with a highly dynamic and non-specific interaction between Hsp90 and p53 DBD in this chaperone-client system, which results in changes in the client protein structure that are detectable by spectroscopic and other methods.

Keywords: chaperone, NMR, isotopic labeling

INTRODUCTION

All living cells employ a complex machinery to ensure that proteins are protected from aggregating or misfolding, and are ultimately either correctly folded in the cytoplasm, targeted to specific cellular locations such as mitochondria, or targeted for degradation. Although many proteins are capable of folding under favorable conditions in vitro, the presence of chaperones during and after ribosomal protein synthesis is required to ensure primarily that the nascent polypeptide chain does not become misfolded before the entire polypeptide has been synthesized.1 Some chaperone molecules actively promote folding of client proteins, while others appear to serve as sequestering sites where exposed hydrophobic side chains in unfolded proteins are prevented from promoting aggregation or misfolding. Although chaperones in eukaryotic cells have multiple overlapping functions, and can substitute for each other in many cases, the present picture of chaperone-protein interactions follows a relatively defined pathway.1,2 Upon extrusion from the ribosome, a nascent polypeptide interacts with ribosome-associated chaperones,3 including the 70 kDa Hsc70 and its co-chaperone Hsp40. The client protein may be folded directly at this stage, or it may be passed on to other systems, including the chaperonin TRiC or, for certain client proteins, the 90 kDa heat-shock protein Hsp90 and its co-chaperones.

Hsp90 is highly conserved among higher eukaryotes, and shows considerable homology with bacterial and yeast versions.4–6 Hsp90-mediated cellular processes appear to be primarily related to interactions with a specific set of client proteins, which include steroid hormone receptors, kinases and polymerases. Specificity and turnover of Hsp90 in its interaction with client proteins is thought to be mediated through the interactions of co-chaperones such as p23 and Cdc37, and is generally dependent on ATP. Hydrolysis of ATP does occur during the chaperone cycle, but the ATP and co-chaperone interactions ultimately appear to act more as a conformational switch than in promoting an ATP-dependent folding reaction such as is seen in other systems such as GroEL. The Hsp90 system is of central importance in the cell, not only when it is up-regulated as part of the heat-shock response, but in the function of normal cells in the absence of stress. Its involvement in signal transduction and transcriptional activation is only just beginning to be elucidated. A number of pharmacological agents targeting Hsp90 have recently been developed for use in cancer therapy.7,8 Other disease states have also been linked with Hsp90, for example cystic fibrosis.9

Hsp90 is a homodimer with three relatively structurally independent domains in each monomer, an N-terminal domain (N), a middle domain (M) and a C-terminal dimerization domain (C) (Figure 1). N is the major site of the weak ATPase activity of Hsp90. M also influences the ATPase activity and has been thought to be the major site of client protein binding. A popular model for Hsp90 action is that the binding of ATP or inhibitors causes conformational changes that may influence binding of clients and co-chaperones and may10 or may not11 promote transient dimerization of N. C domain may also contain a substrate binding site,12,13 and has a sequence at the C-terminus that is specific for binding of tetratricopeptide-repeat (TPR) proteins such as the co-chaperone HOP. M and C are implicated in discrimination between different types of client proteins.14 The backbone fold of dimeric Hsp82, the yeast homolog of Hsp90, is shown in Figure 1B.

Figure 1.

A. Domain structure of human Hsp90α showing domain boundaries used to design the constructs used in this study. B. Ribbon diagram of the X-ray crystal structure of dimeric yeast Hsp82, from the complex with Sba1.24 Ribbon colors correspond to the domain boundaries delineated in part A, and one monomer unit is shown in light colors, the other in darker shades of the same colors. The Sba1 backbone has been omitted for clarity. The figure was prepared using Molmol.54

The interactions of Hsp90 with client proteins vary with the particular client protein, and are mediated by co-chaperones and ATP. The conformations of the client proteins when bound to Hsp90 are unknown, and there are indications that at least some client proteins are present in the complex in conformations different from those present in the free protein.15 High-resolution structures of Hsp90-client protein complexes have not been reported previously, although an electron microscopic reconstruction of a complex between Hsp90, a co-chaperone Cdc37 and a client kinase Cdk4 was decsribed.16 The complexes between Hsp90 and different clients are likely to be quite different, involving different sites on the chaperone.14

One prominent Hsp90 client protein is the tumor suppressor p53, a 393-amino acid transcription factor that is mutated in over 50% of human cancers.17,18 The interaction of the p53 DNA-binding domain (DBD) with Hsp90 has been studied by NMR;19 these authors concluded that the p53 domain was bound to Hsp90 in an unfolded form. Another study has indicated that the p53 DBD interacts with Hsp90 (M and C) in a folded form.20 Our recent data are not completely consistent with either of these studies; we have presented evidence that the p53 DBD takes on a molten globule-like structure in the presence of Hsp90 and its domains.15 Here we show by NMR analysis that Hsp90 interacts with the p53 DBD in a highly dynamic manner, exhibiting evidence of contact between all three domains and the client protein.

RESULTS

Design and Preparation of Hsp90 Domain Constructs for NMR

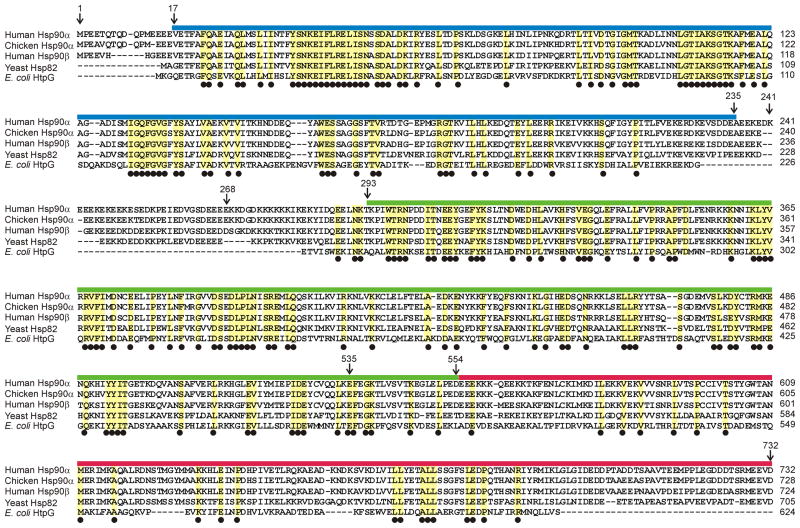

Although Hsp90 and its analogs are quite similar in amino acid sequence between different species, there are significant differences between the sequences of the evolutionarily widely spaced organisms whose Hsp90s have been studied. This is illustrated in Figure 2. The majority of structural work has been reported on the E. coli and yeast proteins. As can be seen from Figure 2, the sequences are highly conserved between human (as used in the present study) and E. coli, for N (36% identical, an additional 34% conserved) and M (32%, 44%) and somewhat less for C domain (11%, 29%). Eukaryotic sequences include a long non-conserved, highly-charged linker sequence between N and M that is absent from the E. coli protein. The DNA sequence for full length human Hsp90α (kindly provided by Dr. David Toft) was engineered to yield smaller constructs to be used in the solution NMR studies of interactions with the p53 DBD. Single-domain constructs were prepared: N (residues 17–235), M (293–554) and C (535–732 and 552–732). We also prepared two-domain constructs, of N and M, including the charged linker sequence between them (termed NM; residues 1–554), and of M and C (MC; residues 293–732), and a full-length protein with part of the charged linker between N and M removed (Hsp90Δ, 1–732, with residues 241–268 removed). According to size-exclusion chromatography, N, M, and NM are present at the concentrations used in the NMR experiments as monomers, and MC and Hsp90Δ as homodimers.

Figure 2.

Amino acid sequence alignment of Homo sapiens Hsp90α, Gallus gallus Hsp90α, Homo sapiens Hsp90β, Saccharomyces cerevisiae Hsp82 and Escherichia coli HtpG. The location of the N-terminal (N), middle (M) and C-terminal (C) domains are indicated by colored bars corresponding to those of Figure 1A. Residues identical among the four species are outlined in yellow and have a black dot beneath. Residue numbers at the boundaries of the domains correspond to the human Hsp90α sequence used in the present study.

The p53 sequence can be divided into 5 domains, the activation domain (AD, 1–62), the proline-rich domain (PRD, 62–94), the DNA-binding domain (DBD, 94–292), the tetramerization domain (TD, 325–356), and the basic domain (BD, 356–393). Since it has been established that the DBD binds Hsp90 with an affinity similar to that of the full-length protein,20 this domain (residues 94–312) was used in our studies of interactions with Hsp90.

Resonance Assignment of Hsp90

Backbone resonance assignments for N and M were made using standard NMR methods with 15N/13C double- and 15N/13C/2H triple-labeled protein. Resonance assignments had previously been published for the N-terminal domain of yeast Hsp82;21 these were used as a general guide for the assignment of the human N construct, but the significant differences in parts of the sequence necessitated fully independent determination of the assignments. Assignments for M or C have not been published. We determined resonance assignments for the isolated M domain, but both constructs of the isolated C were prone to proteolysis and/or aggregation after purification, and the NMR spectrum of C was therefore not assigned.

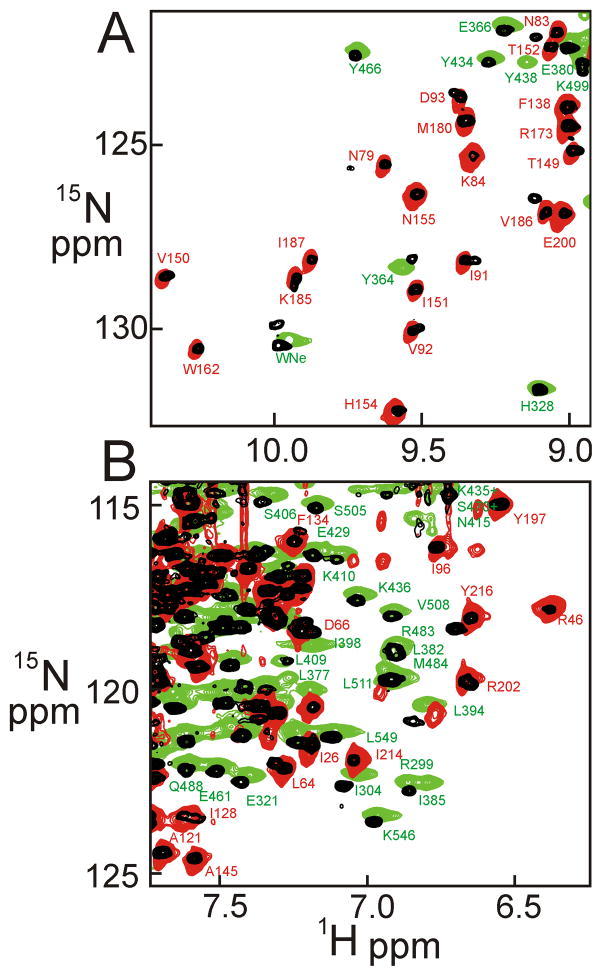

Portions of a superposition of the 15N TROSY-HSQC spectra of N (red), M (green) and NM (black) are shown in Figure 3 (separate spectra are shown in Figure S1). A significant proportion of the well-resolved cross peaks in the spectra of N and M occur at the same positions in the spectrum of the 2-domain NM, indicating that N and M are folded independently in the 2-domain construct, although several well-resolved cross peaks of M do not appear in the spectrum of NM. These cross peaks generally correspond to residues at the end of β-strands, which suggests that they are missing due to differential solvent exchange in the larger construct. It appears likely that the structures of the individual domains are essentially the same in the 1- and 2-domain constructs as in the full length protein. This similarity argues that the domains behave independently, like “beads on a string”, with limited contact between domains, at least in the absence of co-chaperones and client proteins. The similarity between the spectra of the 1- and 2-domain constructs permitted the assignment by juxtaposition of many of the resonances in the 1H-15N TROSY-HSQC spectrum of NM. The isolated C domain gave spectra that were very broad, indicating that this construct is likely multimeric or aggregated in solution. Nevertheless, this portion of the protein can be characterized within the two-domain MC construct and the full-length protein. We therefore conclude that the aggregation of the isolated C domain construct is an artifact.

Figure 3.

A and B. Two regions of a superposition of the 1H-15N TROSY-HSQC spectra of the single-domain constructs N (red; 800 MHz) and M (green; 900 MHz), with that of the two-domain construct NM (black; 900 MHz), showing the correspondence of many of the cross peaks. Selected assigned cross peaks are labeled.

Assignment of Methyl-Labeled Hsp90 Using Domain Constructs

The size of full-length, dimeric Hsp90 mandates the use of specifically-labeled and deuterated samples for NMR characterization. The methyl labeling methods introduced by the Kay lab,22,23 where specifically-labeled samples are prepared by addition of metabolic precursors for Leu, Val and Ile that are labeled with 13C and 2H at specific atoms, have proved as useful in the Hsp90 system as they have in many other systems of comparable size. The 49 Ile residues are well distributed throughout the Hsp90 sequence, with 20 in N, 16 in M, and 11 in C. The two remaining Ile residues are in the charged linker between N and M.

Traditional triple-resonance techniques could not be used to assign the methyl resonances of full length Hsp90 or Hsp90Δ: the 15N-1H TROSY or CRINEPT spectra of full-length protein or Hsp90Δ are too overlapped for sequence-specific assignments to be made, and the high molecular weight causes rapid signal decay during the acquisition of 3D spectra, ruling out this option as a means for resonance assignment. We therefore followed a domain-based assignment strategy, where the resonances of the specifically labeled isoleucine CδH3 methyl groups were assigned by first assigning the residues in single domain constructs. To assign the methyl resonances in the HMQC spectra of N and M (Figure S2), 15N- and 13C- NOESY spectra using U-[2H, 15N] Ileδ1-[13CH3] protein samples were employed. We used the yeast Hsp82 structure (Figure 1) to model structures of human N and M, which allowed us to estimate expected NOEs and assign the methyl resonances accordingly.

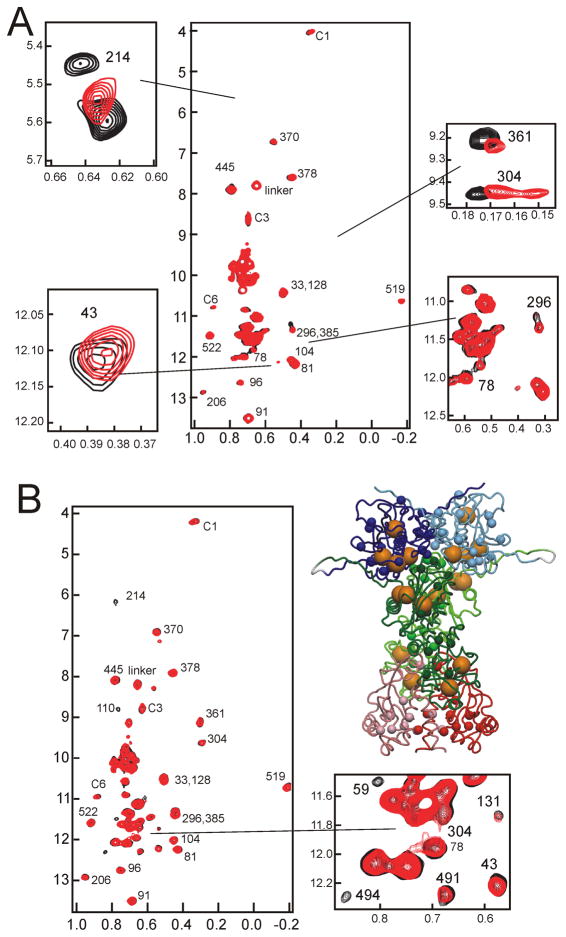

A comparison of the methyl-TROSY spectra of the individual domains and two-domain constructs with that of Hsp90Δ (Figure 4) shows a very good correspondence between cross peak positions, except for some residues in linker and contact regions; the majority of the methyl resonances of the N and M domains of the full-length protein could therefore be assigned by juxtaposition. Cross peaks corresponding to residues at the N-M and M-C interfaces were identified by comparing the methyl-TROSY spectra of each 2-domain construct with those of its constituent single domains. As expected based on the predicted structural similarity between the human Hsp90 dimer and the yeast protein shown in Figure 1, resonances of residues such as Ile214 and Ile370, which are located in the interface between N and M, show a significant difference between the constructs that contain both N and M domains (NM, Hsp90Δ) and those where the N-M interface is exposed (N, M or MC). We infer that the N and M domains of Hsp90 contact each other in solution in a manner similar to that observed in the crystal structure of the yeast Hsp82 dimer.24

Figure 4.

Assignment of methyl spectra of Hsp90 from those of the constituent domains. A. Superposition of the 900 MHz 1H-13C TROSY-HMQC spectra of Hsp90Δ (black) with that of N (blue). B. Superposition of the 900 MHz 1H-13C TROSY-HMQC spectra of Hsp90Δ (black) with that of M (green). C. Superposition of the 900 MHz 1H-13C TROSY-HMQC spectra of Hsp90Δ (black) with that of C (red). The Ile CδH3 cross peaks for C are unassigned, but are labeled to show that there are 11 present, as expected from the amino acid sequence. D. Superposition of the 900 MHz 1H-13C TROSY-HMQC spectra of Hsp90Δ (black) with that of NM (turquoise). Cross peaks are labeled with residue numbers corresponding to those of the N and M spectra of parts A and B. Cross peaks in the NM spectrum that appear in neither the N nor M spectra are presumed to correspond with the 3 Ile residues in the linker between N and M. (Inset) superposition of spectra of NM (black), N (blue) and Hsp90Δ (red), plotted at a lower contour level than for the main spectrum, showing the two positions for the I214 cross peak. E. Superposition of the 900 MHz 1H-13C TROSY-HMQC spectra of Hsp90Δ (black) with that of M (orange). Cross peaks corresponding to assigned resonances of M are labeled with residue numbers, while the 11 unassigned cross peaks of the C domain are numbered as in part C.

The isolated C domain specifically-labeled at the isoleucine CδH3 gave broadened cross peaks in methyl-TROSY-HMQC spectra (Figure 4C), consistent with the 15N-1H TROSY spectra that indicated aggregation for this domain in isolation. Nevertheless, cross peaks are visible, and they correspond to those of the full-length protein, specifically to cross peaks that had not been identified either in N or M. Due to the broad resonances of the isolated C, and the complexity of the spectra of MC, as well as the considerable degree of overlap for the majority of the cross peaks (Figure 4C, 4E), sequence specific assignments of the isoleucine CδH3 resonances have not been made for this domain.

Evidence for Two Conformational States in Free Hsp90

Figure 4A indicates that there are two possible positions for the cross peak of the Ile214 methyl group. In the spectrum of N, the cross peak is at position A (0.7 ppm in 1H and 7.3 ppm in 13C), while in Hsp90Δ it is at position B (0.75 ppm in 1H and 6.0 ppm in 13C). Interestingly, the cross peak is present in both A and B positions in the spectrum of NM (inset to Figure 4D). The two environments for the Ile214 methyl group most likely arise due to the presence of a long charged linker (residues 225–282) between N and M. The presence of two local conformers in slow exchange on the NMR time scale most probably arises from differences in the interactions between N and M. Since N alone shows the cross peak in position A, while for Hsp90Δ the cross peak occurs at position B, we suggest that the A cross peak represents a conformer where N and M are separate, while B represents a conformer where the domains are in closer proximity.

Effect of Nucleotide Binding on the Methyl Spectra

Hsp90 has a weak ATPase activity that appears to be associated with the binding and release of co-chaperones and client proteins.25,26 The ATP-binding site has been localized to the N-terminal domain, and the X-ray structure of the yeast N shows the position of a bound ADP molecule.27 As a test case to determine whether the methyl spectra of Hsp90 were capable of demonstrating the location of binding sites, we performed a titration experiment adding the ATP analog AMP-PNP to methyl-labeled samples of the single and dual-domain constructs of Hsp90. Only the constructs containing N showed changes in the TOCSY-HMQC spectrum upon addition of the ATP analog, and the effects were strongly pH-dependent, with effects more obvious at the higher pH of 7.4. At pH 7.0, there was very little effect of the addition of AMP-PNP on the spectrum of N. The changes observed at pH 7.4 are illustrated in Figure 5. Of the 20 Ile resonances in the N domain, 5 (residues 33, 104, 110, 128 and 131) show relatively large changes, 8 (residues 26, 34, 43, 49, 78, 96, 151 and 218) show smaller changes, 3 (residues 81, 91 and 214) show slight shifts, and 4 (59, 187, 203 and 206) show no change. These changes and their magnitudes are mapped onto the structure of the N domain-ADP complex27 in Figure 5B. Upon addition of AMP-PNP to Hsp90Δ, similar changes were observed for the cross peaks corresponding to N (Figure 5C), confirming that the binding site is the same in the full-length protein as it is in the isolated N.

Figure 5.

Addition of the ATP analog AMP-PNP to N. A. Superposition of 500 MHz 1H-13C TROSY-HMQC spectra of N (black) with added mole ratios of AMP-PMP of 1:2 (red), 1:6 (green), 1:9 (magenta), 1:16 (blue). Residues with significant change are numbered in red, with smaller change in orange, and little or no change in black, with arrows denoting the direction of the change. B. Ribbon diagram of the structure of the N-terminal domain of yeast Hsp90 in complex with ADP 27, showing the ADP in blue. The locations of the isoleucine residues are indicated by spheres centered on the backbone nitrogen atom for clarity, and the residues are labeled according to the data shown in part A. Green and yellow spheres represent residues with small (yellow) or no (green) shifts upon addition of AMP-PNP. C. Superposition of 800 MHz 1H-13C TROSY-HMQC spectra of Hsp90Δ (100 μM, pH 6.7) (black) and in the presence of 3.6 mM AMP-PNP (red). Cross peaks corresponding to the resonances that move significantly in the N-terminal domain are labeled by analogy with the results shown in part A.

Effect of p53 Binding on the NMR Spectra of Hsp90 and its Domains

No information is currently available on the sites of binding of most client proteins on Hsp90. In order to localize the binding site for the p53 DBD domain, at least at a domain level, on Hsp90, we added unlabeled p53 DBD to 15N-labeled samples of N, M, NM and MC. Very little change was observed in the 1H-15N HSQC spectra of these proteins upon addition of up to 6x the molar ratio of p53 DBD (Figure S3). This is puzzling, since the addition of any of the Hsp90 domains to labeled p53 DBD causes profound cross peak attenuation at quite low mole ratios of added Hsp90.15 The cross peaks of some isolated amides in various parts of Hsp90 are affected upon addition of high molar ratios of p53 DBD (Figure S3). This is consistent with the picture obtained from analysis of the p53 spectra,15 that the interaction between Hsp90 and the p53 DBD is a dynamic one, where Hsp90 induces a molten-globule-like conformation in p53.

The effects of addition of p53 DBD to NM and MC were monitored by observing the methyl HMQC spectra of specifically-labeled samples. The small changes that occurred are shown in Figure 6. For NM (Figure 6A), the most noticeable changes were seen in the weak cross peak of Ile110, and in changes in the relative proportions of the double cross peaks of Iles 214 and 218. For MC (Figure 6B) more changes, still small, were observed, several belonging to the (unassigned) methyl residues of the C-terminal domain. The cross peak for residue 491 disappears in the presence of p53 DBD; this resonance was unchanged in the spectrum of NM with p53 DBD. Small changes were also evident for residues 304 and 361, which did not show any observable changes in the NM spectrum. The positions of the analogous residues of the yeast Hsp82 crystal structure are indicated in the insets.

Figure 6.

Superposition of 900 MHz 1H-13C TROSY-HMQC spectra of Ile methyl resonances upon addition of p53 DBD. A. NM (black, 70 μM) and after addition of p53 DBD (red, 210 μM) at 10°C. Small surrounding panels show enlarged portions of the spectrum at lower contour levels. The inset structure shows a portion of the of the X-ray crystal structure of dimeric yeast Hsp8224, identified with the equivalent residues of yeast Hsp82 using the sequence alignment in Figure 2. The small colored spheres show the location of the isoleucine Cδ atoms, color coded according to their position in the N and M domains, with the locations of the residues identified in the three enlarged spectra shown in orange. B. MC (black, 50 μM) and after addition of p53 DBD (red, 150 μM) at 10°C. Small surrounding panels show enlarged portions of the spectrum at lower contour levels. The inset structure shows a portion of the of the X-ray crystal structure of dimeric yeast Hsp8224, identified with the equivalent residues of yeast Hsp82 using the sequence alignment in Figure 2. The small colored spheres show the location of the isoleucine Cδ atoms, color coded according to their position in the M and C domains, with lighter colors for one monomeric unit and darker colors for the other. The locations of the residues identified in the enlarged spectra are shown in orange.

Changes in the methyl HMQC spectra of Hsp90Δ at two temperatures, 10°C and 25°C, were monitored on addition of increasing amounts of p53 (Figure 7). Again, small changes are observed, mainly in the form of attenuation of cross peaks belonging to isolated residues. Indeed, the residues that appear to be affected upon addition of p53 are mainly located in the interfaces between domains, and are the same ones that show spectral differences between single- and two-domain constructs (Figure 4). In particular, the cross peak for Ile214, which shows two conformations in the NM construct, appears to show a small shift, and small shifts and resonance broadening or attenuation are seen for several of the weaker peaks, such as Ile43, Ile59, Ile110, Ile296, Ile361 and Ile304, which include residues located near the ATP lid of the N domain and in the N/M and M/C domain interfaces.

Figure 7.

Superposition of 900 MHz 1H-13C TROSY-HMQC spectra of Ile methyl resonances of Hsp90Δ upon addition of p53 DBD at two temperatures. A. Hsp90Δ (black, 52 μM) and after addition of p53 DBD (red, 100 μM) at 10°C. Small surrounding panels show enlarged portions of the spectrum at lower contour levels. B. Hsp90Δ (black, 40 μM) and after addition of p53 DBD (red, 120 μM) at 25°C. The small panel shows an enlarged portion of the spectrum at the same contour level. The inset structure shows a portion of the of the X-ray crystal structure of dimeric yeast Hsp8224, orange spheres show the residues affected by p53 addition, identified with the equivalent residues of yeast Hsp82 using the sequence alignment in Figure 2. The small colored spheres show the location of the isoleucine Cδ atoms, color coded according to their position in the N, M and C domains, with lighter colors for one monomeric unit and darker colors for the other. The locations of the residues identified in the enlarged spectra of both parts A and B shown in orange.

These changes may indicate that the addition of the p53 DBD to Hsp90 causes changes in the spatial relationship between domains. These observations are also consistent with a weak, non-specific and dynamic interaction between the N and M domains of Hsp90 and the client protein, and suggest the need for a different approach to determining the primary sites of contact.

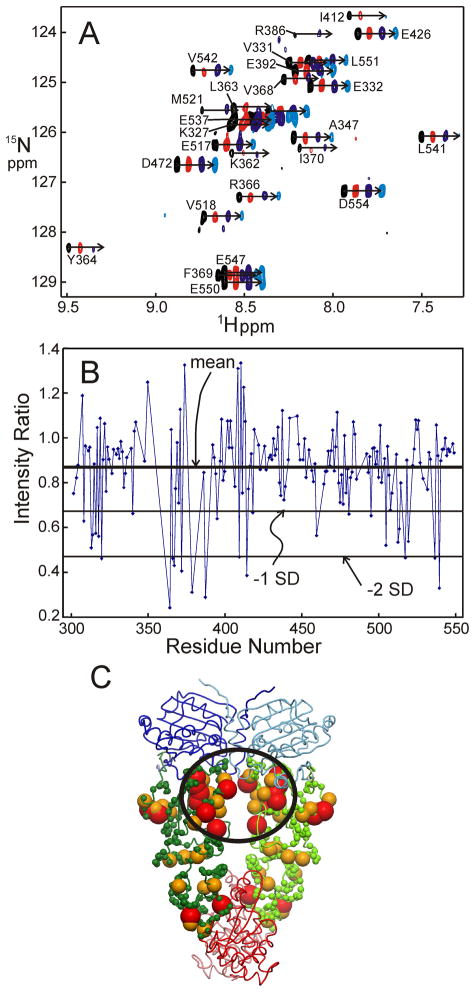

Elucidation of Contact Sites using Saturation Transfer Measurements

To determine the primary contact site(s) of p53 on the M domain of Hsp90, cross-saturation transfer experiments28 were performed. We infer from the titration experiments that the dissociation rates of p53 from the Hsp90 domains are fast. A molar ratio of [2H, 15N]-M: p53 DBD = 1: 0.05 was therefore used in order to maximize the saturation transfer efficiency. Portions of the resulting spectra are shown in Figure 8A. The saturation transfer experiment gives information on the contact sites in a complex where one component is highly if not uniformly deuterated and labeled with 15N, and the other component is unlabeled.28 Back-exchange of the amide protons of the deuterated component allows detection of saturation transfer from the protons of the unlabeled partner to the 15N-1H groups of the deuterated component. The effect is strongly distance-dependent (r−6)and is manifested as a loss of intensity in those cross peaks of the HSQC or TROSY spectrum belonging to the residues that are nearest (within about ~7Å) to the contact site of the protonated partner. Irradiation of the aliphatic region of p53 resulted in different intensity losses for each 1H-15N cross peak in the TROSY spectrum of M. In order to account for the effects of residual protonation in the highly deuterated M domain, comparison was made of the spectra obtained with and without saturation, both in the absence and presence of the p53 DBD. Reduction ratios of the peak intensities were calculated for each residue of the M domain (Figure 8B). The mean value of intensity reduction was 0.86 and the standard deviation was ± 0.2. Regions of M that are most affected by saturation of the protonated p53 are mapped onto the structure of yeast Hsp82 in Figure 8C. The most affected residues are distributed all over M, but there is a concentration of affected residues at the dimer interface of M in the region closest to N. The residues circled in Figure 8C are located on strands 3 and 4 of M and correspond to the group of lowered intensity ratios around residues 350–380 of Figure 8B. Other regions that show saturation transfer effects include the surface helix that connects M and N, and isolated sites near the interface with the C-terminal domain. A long loop containing many charged residues connects strands 2 and 3 of M. Although this loop might be involved in binding to p53, since it is adjacent to the site on strands 3 and 4 that we identified in the saturation transfer experiments, the resonances of residues in the loop could not be detected in the spectrum, presumably due to conformational fluctuation on an intermediate time scale.

Figure 8.

A. Overlay of four HSQC spectra (portion) showing the results of the saturation transfer experiments. For each residue, cross peaks for the free M domain with no saturation (black), free M domain with saturation in the aliphatic region (red), M domain in complex with p53 with no saturation (dark blue) and M domain in complex with p53 with saturation of the aliphatic protons (light blue) are shown offset for clarity. The scale at the bottom of the figure refers to the 1H chemical shifts of the black spectrum. B. Attenuation of measured peak volume by saturation transfer plotted per residue according to the sequence of human Hsp90 M domain. The values are obtained from the calculation: [volume(M+p53)sat/volume(M+p53)unsat]/[volume(M)sat/volume(M)unsat] for each cross peak that could be adequately resolved in the spectrum. The cutoff for the red and orange colored spheres in part C are shown for residues with volume ratios < (mean − 2 × SD) (red) and with volume ratios < (mean − 1 × SD) (orange). The mean value of the volume ratio calculated from a total of 174 resolved cross peaks was 0.86, with a standard deviation of 0.20. C. Mapping of contact points on the M domain identified by the saturation transfer data onto the structure of yeast Hsp82.24 Positions of backbone nitrogen atoms of residues where the N-H cross peak was significantly more attenuated for the complex, compared with the free protein are shown as spheres. The residues attenuated by saturation in the M domain of human Hsp90 (as measured in this work) were identified with the equivalent residues of yeast Hsp82 using the sequence alignment in Figure 2. The figure was prepared using Molmol.54

DISCUSSION

Structures of Hsp90 are Relatively Dynamic

X-ray structure determination of the entire Hsp90 dimer has been difficult, due to its three flexibly linked domains. A number of X-ray crystal structures have been published of individual domains: the N domain27,29–33 and M domain34,35 of eukaryotic Hsp90s, and the C domain36 and N plus M domains37 of HtpG, the E. coli analog of Hsp90. Additionally, X-ray structures of full length Hsp90 are now available: the complete dimer of yeast Hsp82, the yeast homolog of Hsp90, in complex with the ATP analog AMP-PNP and with Sba1, the yeast homolog of p2324, the dimer of E. coli HtpG38, and the dimer of Grp94, the Hsp90 analog specific to the endoplasmic reticulum.39 The yeast structure (Figure 1B) represents a “closed” form of the protein, with ATP bound in the N domain, and with the M domain catalytic loop in close proximity to the γ-phosphate of the ATP analog, as predicted by previous studies.34 The C domain is dimerized very similarly to the published structure of the isolated E. coli dimer.36 The central cavity of the Hsp90 dimer in this “closed” state, formed primarily by the M domains, is thought to be too small to accommodate client proteins: the question of the likely location of client binding site(s) was thus unresolved by the crystal structure of the intact dimer. In the yeast Hsp82 structure,24 an Sba1 (= yeast p23) molecule is bound between the N and M domains of each protomer, apparently mediating a close interaction between the N domains of the two protomers and a change in the so-called “lid domain” (residues 94–125) from an “open” position in the isolated N domain to a “closed” position over the nucleotide binding pocket.

It is hard to argue from X-ray crystal structures for the presence of dynamics in proteins, although crystallographic disorder can be used as a measure of potential disorder in the free proteins in solution. More telling is the difficulty that has been experienced in crystallizing the full-length protein for structure determination: in general, those proteins that cannot be readily crystallized may be assumed to participate in dynamic movements of the domains relative to each other, perhaps of the type that we observe in the 2-domain constructs studied here. Conformational flexibility of Hsp90 has been invoked to explain other observations related to its slow ATP hydrolysis reaction. Comparison of the crystal structures of Hsp90 in the presence and absence of nucleotide (ATP, ADP and the analog AMP-PNP) showed major differences in the disposition of the N and M domains in the homodimer.38 The apoprotein of eukaryotic Hsp90 was shown to take up multiple conformations by small-angle X-ray scattering and single-particle cryo-EM,40 and multiple conformations were identified for the E. coli HtpG using single-particle reconstruction,41 hydrogen exchange mass spectrometry42 and small-angle X-ray scattering.43 The consensus in these studies is that under most conditions Hsp90 can take up at least two conformations, and potentially more when present alone in solution. We note that we have also observed the presence of two distinct conformations of Hsp90 by NMR in the present work (Figure 5). However, we would argue on the basis of our observations of the interaction of Hsp90 with p53 (Figure 6–8) for a considerably more flexible and heterogeneous conformational ensemble for the Hsp90 dimer in the absence of ATP and co-chaperone. The fact that the NMR spectra of the 2-domain constructs (and of the full-length dimeric protein) are superimposable to a large degree on the spectra of the individual domains (Figures 3, 4) argues for considerable independence of motion between the individual domains, even in the full-length dimer, with the exception of the C-terminal dimerization domain.

Interactions with the p53 Client Protein Are Dynamic

One of the most puzzling features of the NMR data on the interactions of Hsp90 with p53 is that the spectra of p53 show a discernible change when Hsp90 domains are added,15 but the Hsp90 spectra appear very little changed even at high mole ratios of added p53 (this work). If the complex between the two proteins was tight and specific, we would expect to see defined changes in the 2D NMR spectra, either as movements of cross peaks (“fast exchange”) or disappearance of the cross peaks and their reappearance at other positions (“slow exchange”). Instead, for the p53 spectra we see a gradual disappearance of some cross peaks while others are unchanged.15 This behavior is not consistent with any well-known mechanism of complex formation: we concluded that the NMR data, together with other biophysical data, indicated that the p53 was adopting a molten globule-like state in the presence of the Hsp90. Further, similar behavior was observed for all of the Hsp90 constructs containing the N and/or M domains, whether single-domain, 2-domain or full-length. This implied that both the N and M domain participate in the interaction, and that the interaction is dynamic and not site-specific.15

The fact that the NMR spectra of the Hsp90 domains are virtually unchanged upon addition of p53, as described here, supports this conclusion. If Hsp90 makes contact with the client protein at a multitude of sites, the resonances of residues at any particular site should not be perturbed any more than those at any other site. Certainly, the system is capable of reporting on the site-specific binding of ligands, as is shown by the results for the binding of the ATP analog to the N domain and to the full-length protein (Figure 5).

The only indication of any site-specificity in the interaction is given by the saturation-transfer experiments (Figure 8). Although the M domain cross peaks showing the influence of the added p53 DBD are distributed over the entire domain, there is a relatively uniform concentration of affected residues at one end of the domain. In the full-length protein, this region of the M domain would be located in the dimer interface of the “closed” structure depicted in Figure 8C. Interestingly, this same region is also the location of a number of the small changes observed in the methyl HMQC spectra of NM, MC and Hsp90Δ (Figures 6 and 7). Although the weak and heterogeneous nature of the interaction of p53 with Hsp90 in the absence of co-chaperones and ATP is evident from the data we have presented here, a close examination of the data suggests that the primary interaction site on Hsp90 for p53 likely involves the region of the interface between the N and M domains and that interaction of Hsp90 with p53 is accompanied by changes in the contacts between Hsp90 domains.

Physiological Consequences of the Model

The physiological relevance of the p53-Hsp90 interaction is still incompletely understood. Both wild type and mutant p53s interact specifically with Hsp90 in vivo.44,45 Inhibition of the tight binding between Hsp90 and mutant p53 accelerates mutant p53 degradation,46 forming the basis for part of the therapeutic action of anti-cancer agents such as geldanamycin that inhibit Hsp90 activity.45 Using purified proteins, Müller et al.20 showed that the core domain of p53 interacts with the M and C domains of Hsp90, an interaction that is essential to stabilize p53 at physiological temperatures and to prevent it from undergoing irreversible thermal inactivation. Yet it also appears that the p53 DBD is, in a sense, destabilized by the presence of Hsp90 and its domains, since it appears to form a molten globule-like state.15 A molten globule state has also been observed for p53 at low pH.47 The explanation for these apparent contradictions may lie in the dynamic nature of the primary interaction between the Hsp90 and its client, as well as the over-simplified system that we have used to study this interaction. The interactions of Hsp90 and client proteins in vivo are modulated by a host of other protein factors, including other chaperones such as Hsp70 and Hsp40, co-chaperones such as p23 and Aha1 and small molecules such as ATP. What we may be monitoring in our NMR experiments is the primary interaction of Hsp90 with a client protein, independent of the modulation imposed by the presence of other factors. If indeed the primary interaction of Hsp90 and clients is dynamic, the other factors would be necessary to guide the interaction in the direction needed for the health of the cell. On the other hand, on a more fundamental level, it is important to recognize that the function of a chaperone such as Hsp90 may not be to stabilize the folds of proteins, but rather to hold them in states that are conducive to their subsequent function. For example, the nuclear hormone receptor ligand binding domains are prominent clients of Hsp90, and are well known to require Hsp90 in order to remain in a stable hormone-receptive state in the resting cytoplasm. It is intuitively attractive to visualize that state as some form of a molten globule-like state, similar to what we observe in our experiments with p53.15

Why the interaction with the Hsp90 domains needs to be so dynamic is perhaps harder to rationalize. Clearly such a dynamic interaction may be modulated in the presence of other factors such as co-chaperones, but the dynamic and non-specific nature of the interaction in the absence of these factors may also provide an explanation for the observed rather wide range of structure and sequence types in the client proteins of Hsp90. A relatively non-specific interaction, with multiple possible binding sites throughout the molecule, might lend itself at the same time to a wide client specificity and a low enough affinity that the client could readily dissociate from the chaperone under the right circumstances.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Preparation of Hsp90 Constructs and p53 DBD domain

The constructs of human Hsp90α (residues 1–732) used in this study are the N-terminal domain (1–235), the Middle domain (293–554), the C-terminal domain (2 constructs, 535–732 and 552–732), the NM 2-domain construct (1–554), the MC 2-domain construct (293–732), and the full-length protein where part of the linker between N and M (residues 241–268) was deleted (Hsp90Δ). As mentioned previously,15 the full-length protein with part of the linker removed was used because the full length protein wash more difficult to express and purify from bacterial cell culture in quantities suitable for NMR spectroscopy.

Proteins were expressed in M9 minimal medium in the E. coli host BL21 (DE3) [DNAY] with induction at 15 °C for 12–20 h. Cells were lysed by sonication in 25 mM Tris buffer, pH 8.0, supplemented with 5 mM DTT, a tablet of Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche) and 4 mM EDTA. The soluble fraction of the cell lysate was applied to a 60 ml Sepharose Q FF column equilibrated with 25 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT and proteins eluted with a linear gradient to 1 M NaCl, concentrated using Centriprep10 (Amicon) and purified by gel filtration chromatography on a 350 ml Sephacryl S100HR (2.6 × 65 cm) (or Sephacryl S300HR for NM, MC, and ΔHsp90 preparation) in 20 mM Tris, pH 7.2, 0.1 M KCl, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT.

Expression of [70% 2H, 13C, 15N]-labeled proteins was carried out in M9 minimal medium in D2O supplemented with 15NH4Cl (0.5 g/L), 15NH4SO4 (0.5 g/L) and 13C-labeled glucose (2 g/L), and [2H, 15N]-labeled proteins was obtained using 12C-deuterated glucose (2 g/L). The culture was induced by 1 mM IPTG at 15 °C with 16-h incubation.

The specific protonation of 13C-labeled methyl groups of Ile was followed as described previously.22,23 U-[2H] Ileδ1-[13CH3] protein samples were prepared in D2O M9 media supplemented with 2 g/L of U-[12C,2H]-glucose as the main carbon source and 1 g/L of 15NH4Cl as the nitrogen source. One hour prior to induction, 120 mg of 2-keto-3,3-d2-1,2,3,4-13C-butyrate were added to the growth medium. The growth was continued for 7 h at 37 °C.

The DNA-binding domain of human p53 (94–312) was prepared by expression in M9 minimal medium in the E. coli host BL21 (DE3) [DNAY] with induction at 15°C for 12 20 h. Cells were lysed by sonication in 25 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.0, supplemented with 5 mM DTT, a tablet of Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche), 10 μM ZnSO4 and 40 mM NaCl. The soluble fraction of the cell lysate was applied to a 10 ml Hitrap Q column equilibrated with 25 mM Tris, pH 7.0, 10 μM ZnSO4, 5 mM DTT and proteins eluted with a linear gradient to 1 M NaCl, and purified by Heparin column in 25 mM Tris, pH 7.0, 40 mM NaCl, and 5mM DTT.

NMR spectroscopy

Protein concentrations for NMR spectroscopy were typically 100–300 μM. Backbone resonance assignments for the N(1–235) and M(293–554) proteins were made using triply labeled [70% 2H, 13C, 15N] proteins. For most samples, HNCA48,49, HN(CO)CA48,49, HN(CA)CB48,50, HN(COCA)CB48, and HNCO50 spectra, or their TROSY equivalents51 were acquired.

NMR spectra were acquired at 25°C on a Bruker DRX800 or Avance900 spectrometer equipped with a cryoprobe. The sample was exchanged for NMR into 25 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.2)/100 mM NaCl/1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)/4 mM DTT in 90% H2O and 10% D2O. The following parameters were used in the 3D experiments: for TrHNCA, data size = 2048 (t3) × 48 (t2) × 96 (t1) complex points, number of scans = 16; for TrHN(CO)CA, data size = 2048 (t3) × 40 (t2) × 96 (t1) complex points, number of scans = 16; for TrHN(CA)CB, data size = 2048 (t3) × 48 (t2) × 90 (t1) complex points, number of scans = 32; for TrHN(COCA)CB, data size = 2048 (t3) × 48 (t2) × 90 (t1) complex points, number of scans = 32; for TrHNCO, data size = 2048 (t3) × 48 (t2) × 64 (t1) complex points, number of scans = 4. The delay time between each scan is 1.5 s.

The Ile δ1 methyl resonances of the N- and M-domains were assigned using U-[2H, 15N] Ileδ1-[13CH3] protein samples, with a series of 15N- and 13C-NOESY spectra with mixing times varying from 50 ms to 200 ms. The assignments were checked with reference to X-ray structure of the yeast Hsp82.24

NMR spectroscopy for protein-protein interaction

NMR titration experiments were performed at 10°C on a Bruker DRX800 or Avance900 spectrometer. 15N labeled N, M and NM proteins were titrated with unlabeled p53 DBD(93–312) using concentration ratios that included 1:0, 1:0.5, 1:1, 1:2, 1:3 and 1:6. Assignments were transferred from the spectra at 25°C to 10°C by acquiring a series of HSQC spectra at increments of 5°C and following the temperature-dependent shift of each cross peak.

Cross-saturation transfer experiments (CST) were performed using published pulse schemes28,52 at 900 MHz and 10°C with 64 scans. The aliphatic protons of the p53 DBD were saturated using the WURST-2 decoupling scheme.53 The maximum RF amplitude was 0.17 kHz for WURST-2 (the adiabatic factor Q 0 = 1). The saturation frequencies were set at 0.9 p.p.m for amide resonance detection. The recycle delay was 3.2 s (2.0 s for the T1 delay and 1.2 s for the saturation time). Spectra where the aliphatic region of the 1H spectrum was saturated were compared with unsaturated controls for free M(2H, 15N) and for the complex of M (2H, 15N) and p53 DBD (unlabeled) were recorded in 20% H2O buffer (25 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0)/100 mM NaCl/5 mM deuterated DTT). The concentrations of M and p53 DBD were 500 μM and 25 μM, respectively.

Saturation transfer data were analyzed by comparing the intensities and volumes of each cross peak under the 4 recorded conditions: (1) M alone, no saturation; (2) M alone, with saturation; (3) M-p53 complex, no saturation; (4) M-p53 complex, with saturation. For each cross peak, the volume (or intensity) under condition (2) was divided by the corresponding quantity for the same cross peak under condition (1). Similarly, the volume (or intensity) for the cross peak under condition (4) was divided by the quantity under condition (3). These two quotients, which represent (A) the intensity lost upon proton saturation in the absence of protonated ligand (and which thus corrects for any residual protons present in the deuterated M domain) and (B) the intensity lost in the presence of protonated p53 DBD, are then compared by dividing the quotient (B) by the quotient (A) for each cross peak. This should yield a number between 0 and 1; values greater than 1 are an indication that the process has significant inherent errors. Numbers close to 1 indicate that there is no effect of cross-saturation and therefore these residues are far from the binding site of the p53 DBD. Lower numbers indicate a progressively closer approach of these sites to the p53 ligand in the complex. The data were analyzed by computing a mean and standard deviation. Residues with values of the volume ratio lower than (mean − 2 × SD) are plotted onto the structure of the yeast protein in Figure 8C as red balls at the position of the backbone N. Residues with values between 1 and 2 × SD lower than the mean are shown as orange balls in Figure 8C.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: GM57374, This work was supported by the Korea Research Foundation Grant funded by the Korean Government (MOEHRD), (KRF-214-2006-1-E00009).

We thank Peter Wright, Maria Yamout and members of the Wright and Dyson groups for helpful discussions, Linda Tennant and Euvel Manlapaz for technical assistance and Gerard Kroon for assistance with NMR experiments. This work was supported by grant GM57374 from the National Institutes of Health, and by a grant from the Korea Research Foundation, funded by the Korean Government (MOEHRD), (KRF-214-2006-1-E00009).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Young JC, Agashe VR, Siegers K, Hartl FU. Pathways of chaperone-mediated protein folding in the cytosol. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:781–791. doi: 10.1038/nrm1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wegele H, Muller L, Buchner J. Hsp70 and Hsp90--a relay team for protein folding. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;151:1–44. doi: 10.1007/s10254-003-0021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hundley HA, Walter W, Bairstow S, Craig EA. Human Mpp11 J protein: ribosome-tethered molecular chaperones are ubiquitous. Science. 2005;308:1032–1034. doi: 10.1126/science.1109247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pratt WB, Toft DO. Steroid receptor interactions with heat shock protein and immunophilin chaperones. Endocr Rev. 1997;18:306–360. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.3.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richter K, Buchner J. Hsp90: chaperoning signal transduction. J Cell Physiol. 2001;188:281–290. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terasawa K, Minami M, Minami Y. Constantly updated knowledge of Hsp90. J Biochem (Tokyo) 2005;137:443–447. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvi056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharp S, Workman P. Inhibitors of the HSP90 molecular chaperone: current status. Adv Cancer Res. 2006;95:323–348. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(06)95009-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Powers MV, Workman P. Targeting of multiple signalling pathways by heat shock protein 90 molecular chaperone inhibitors. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2006;13(Suppl 1):S125–S135. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang X, Venable J, LaPointe P, Hutt DM, Koulov AV, Coppinger J, Gurkan C, Kellner W, Matteson J, Plutner H, Riordan JR, Kelly JW, Yates JR, III, Balch WE. Hsp90 cochaperone Aha1 downregulation rescues misfolding of CFTR in cystic fibrosis. Cell. 2006;127:803–815. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prodromou C, Panaretou B, Chohan S, Siligardi G, O’Brien R, Ladbury JE, Roe SM, Piper PW, Pearl LH. The ATPase cycle of Hsp90 drives a molecular ‘clamp’ via transient dimerization of the N-terminal domains. EMBO J. 2000;19:4383–4392. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.16.4383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLaughlin SH, Ventouras LA, Lobbezoo B, Jackson SE. Independent ATPase activity of Hsp90 subunits creates a flexible assembly platform. J Mol Biol. 2004;344:813–826. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young JC, Schneider C, Hartl FU. In vitro evidence that hsp90 contains two independent chaperone sites. FEBS Lett. 1997;418:139–143. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01363-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scheibel T, Weikl T, Buchner J. Two chaperone sites in Hsp90 differing in substrate specificity and ATP dependence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1495–1499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hawle P, Siepmann M, Harst A, Siderius M, Reusch HP, Obermann WMJ. The middle domain of Hsp90 acts as a discriminator between different types of client proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:8385–8395. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02188-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park SJ, Borin BN, Martinez-Yamout MA, Dyson HJ. The client protein p53 forms a molten globule-like state in the presence of Hsp90. Nature Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:537–541. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vaughan CK, Gohlke U, Sobott F, Good VM, Ali MM, Prodromou C, Robinson CV, Saibil HR, Pearl LH. Structure of an Hsp90-Cdc37-Cdk4 complex. Mol Cell. 2006;23:697–707. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soussi T, Legros Y, Lubin R, Ory K, Schlichtholz B. Multifactorial analysis of p53 alteration in human cancer: a review. Int J Cancer. 1994;57:1–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910570102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vogelstein B, Lane D, Levine AJ. Surfing the p53 network. Nature. 2000;408:307–310. doi: 10.1038/35042675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rüdiger S, Freund SM, Veprintsev DB, Fersht AR. CRINEPT-TROSY NMR reveals p53 core domain bound in an unfolded form to the chaperone Hsp90. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11085–11090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132393699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Müller L, Schaupp A, Walerych D, Wegele H, Büchner J. Hsp90 regulates the activity of wild type p53 under physiological and elevated temperatures. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48846–48854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407687200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dehner A, Furrer J, Richter K, Schuster I, Buchner J, Kessler H. NMR chemical shift perturbation study of the N-terminal domain of Hsp90 upon binding of ADP, AMP-PNP, geldanamycin, and radicicol. Chembiochem. 2003;4:870–877. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tugarinov V, Kanelis V, Kay LE. Isotope labeling strategies for the study of high-molecular-weight proteins by solution NMR spectroscopy. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:749–754. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tugarinov V, Kay LE. Methyl groups as probes of structure and dynamics in NMR studies of high-molecular-weight proteins. Chembiochem. 2005;6:1567–1577. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ali MM, Roe SM, Vaughan CK, Meyer P, Panaretou B, Piper PW, Prodromou C, Pearl LH. Crystal structure of an Hsp90-nucleotide-p23/Sba1 closed chaperone complex. Nature. 2006;440:1013–1017. doi: 10.1038/nature04716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hessling M, Richter K, Buchner J. Dissection of the ATP-induced conformational cycle of the molecular chaperone Hsp90. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:287–293. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mickler M, Hessling M, Ratzke C, Buchner J, Hugel T. The large conformational changes of Hsp90 are only weakly coupled to ATP hydrolysis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:281–286. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prodromou C, Roe SM, O’Brien R, Ladbury JE, Piper PW, Pearl LH. Identification and structural characterization of the ATP/ADP-binding site in the Hsp90 molecular chaperone. Cell. 1997;90:65–75. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takahashi H, Nakanishi T, Kami K, Arata Y, Shimada I. A novel NMR method for determining the interfaces of large protein-protein complexes. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:220–223. doi: 10.1038/73331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stebbins CE, Russo AA, Schneider C, Rosen N, Hartl FU, Pavletich NP. Crystal structure of an Hsp90-geldanamycin complex: Targeting of a protein chaperone by an antitumor agent. Cell. 1997;89:239–250. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80203-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Obermann WM, Sondermann H, Russo AA, Pavletich NP, Hartl FU. In vivo function of Hsp90 is dependent on ATP binding and ATP hydrolysis. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:901–910. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.4.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roe SM, Prodromou C, O’Brien R, Ladbury JE, Piper PW, Pearl LH. Structural basis for inhibition of the Hsp90 molecular chaperone by the antitumor antibiotics radicicol and geldanamycin. J Med Chem. 1999;42:260–266. doi: 10.1021/jm980403y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jez JM, Chen JC, Rastelli G, Stroud RM, Santi DV. Crystal structure and molecular modeling of 17-DMAG in complex with human Hsp90. Chem Biol. 2003;10:361–368. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(03)00075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roe SM, Ali MM, Meyer P, Vaughan CK, Panaretou B, Piper PW, Prodromou C, Pearl LH. The mechanism of Hsp90 regulation by the protein kinase-specific cochaperone p50(cdc37) Cell. 2004;116:87–98. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meyer P, Prodromou C, Hu B, Vaughan C, Roe SM, Panaretou B, Piper PW, Pearl LH. Structural and functional analysis of the middle segment of hsp90: implications for ATP hydrolysis and client protein and cochaperone interactions. Mol Cell. 2003;11:647–658. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meyer P, Prodromou C, Liao C, Hu B, Roe SM, Vaughan CK, Vlasic I, Panaretou B, Piper PW, Pearl LH. Structural basis for recruitment of the ATPase activator Aha1 to the Hsp90 chaperone machinery. EMBO J. 2004;23:511–519. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harris SF, Shiau AK, Agard DA. The crystal structure of the carboxy-terminal dimerization domain of htpG, the Escherichia coli Hsp90, reveals a potential substrate binding site. Structure. 2004;12:1087–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huai Q, Wang H, Liu Y, Kim HY, Toft D, Ke H. Structures of the N-terminal and middle domains of E. coli Hsp90 and conformation changes upon ADP binding. Structure. 2005;13:579–590. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shiau AK, Harris SF, Southworth DR, Agard DA. Structural analysis of E. coli hsp90 reveals dramatic nucleotide-dependent conformational rearrangements. Cell. 2006;127:329–340. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dollins DE, Warren JJ, Immormino RM, Gewirth DT. Structures of GRP94-nucleotide complexes reveal mechanistic differences between the hsp90 chaperones. Mol Cell. 2007;28:41–56. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bron P, Giudice E, Rolland JP, Buey RM, Barbier P, Diaz JF, Peyrot V, Thomas D, Garnier C. Apo-Hsp90 coexists in two open conformational states in solution. Biol Cell. 2008;100:413–425. doi: 10.1042/BC20070149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Southworth DR, Agard DA. Species-dependent ensembles of conserved conformational states define the Hsp90 chaperone ATPase cycle. Mol Cell. 2008;32:631–640. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Graf C, Stankiewicz M, Kramer G, Mayer MP. Spatially and kinetically resolved changes in the conformational dynamics of the Hsp90 chaperone machine. EMBO J. 2009;28:602–613. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krukenberg KA, Forster F, Rice LM, Sali A, Agard DA. Multiple conformations of E. coli Hsp90 in solution: insights into the conformational dynamics of Hsp90. Structure. 2008;16:755–765. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blagosklonny MV, Toretsky J, Bohen S, Neckers L. Mutant conformation of p53 translated in vitro or in vivo requires functional HSP90. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8379–8383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whitesell L, Sutphin PD, Pulcini EJ, Martinez JD, Cook PH. The physical association of multiple molecular chaperone proteins with mutant p53 is altered by geldanamycin, an hsp90-binding agent. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1517–1524. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.3.1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peng Y, Chen L, Li C, Lu W, Chen J. Inhibition of MDM2 by hsp90 contributes to mutant p53 stabilization. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:40583–40590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102817200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ano Bom AP, Freitas MS, Moreira FS, Ferraz D, Sanches D, Gomes AM, Valente AP, Cordeiro Y, Silva JL. The p53 core domain is a molten globule at low pH: Functional implications of a partially unfolded structure. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:2857–2866. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.075861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamazaki T, Lee W, Arrowsmith CH, Muhandiram DR, Kay LE. A suite of triple-resonance NMR experiments for the backbone assignment of 15N, 13C, 2H labeled proteins with high sensitivity. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:11655–11666. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grzesiek S, Bax A. Improved 3D triple-resonance NMR techniques applied to a 31 kDa protein. J Magn Reson. 1992;96:432–440. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wittekind M, Mueller L. HNCACB, a high-sensitivity 3D NMR experiment to correlate amide-proton and nitrogen resonances with the alpha- and beta-carbon resonances in proteins. J Magn Reson. 1993;101:201–205. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salzmann M, Wider G, Pervushin K, Senn H, Wüthrich K. TROSY-type triple-resonance experiments for sequential NMR assignments of large proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:844–848. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takahashi H, Miyazawa M, Ina Y, Fukunishi Y, Mizukoshi Y, Nakamura H, Shimada I. Utilization of methyl proton resonances in cross-saturation measurement for determining the interfaces of large protein-protein complexes. J Biomol NMR. 2006;34:167–177. doi: 10.1007/s10858-006-0008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kupce E, Freeman R. Adiabatic pulses for wideband inversion and broadband decoupling. J Magn Reson Series A. 1995;115:273–276. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koradi R, Billeter M, Wüthrich K. MOLMOL: A program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J Mol Graphics. 1996;14:51–55. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.