Abstract

Levels of serum cytokines are important markers for a broad range of human health conditions, ranging from infectious disease and cancer, to pollutant exposure and stress. In the interest of developing new rapid label-free methods for profiling serum cytokines, we have examined the utility of Arrayed Imaging Reflectometry (AIR) microarrays for this application. We find that AIR is readily able to profile 14 cytokines and other inflammatory biomarker proteins in a background of buffered bovine serum albumin or 1% bovine serum with performance metrics comparable to singleplex ELISA, but in a multiplex, chip-based, reagentless format. Further experiments with interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) demonstrated that the concentration of bovine serum could be increased to at least 20% without changing the overall analytical profile or limit of detection (< 10 pg/mL).

1. Introduction

Serum cytokine levels are generally recognized as important markers for a broad range of human diseases, and efforts are under way in many laboratories to establish relationships between particular patterns of expression and specific disease states. Multiplex serum cytokine measurements have been studied in health applications as diverse as melanoma prognosis (Yukovetsky et al., 2007), environmental pollutant exposure (Haarmann-Stemman et al., 2009; Tal et al., 2010), infections disease (Woehrle et al., 2008), pulmonary inflammatory diseases (Groneburg and Chung, 2004), and stress (Carboni et al., 2010). In turn, these studies have driven development of new methods for cytokine detection, including microsphere-based arrays (Blicharz et al., 2009), fluorescence-detected antibody arrays (Wang et al., 2002), carbon nanotubes (Malhotra et al. 2010), and others. Commercial cytokine assay panels and systems are also available from a number of companies, augmenting the “traditional” lower-throughput methods such as ELISA commonly available in diagnostic laboratories. Despite the already significant level of existing and new technologies available, there remains a continuing need for multiplex sensor technologies able to detect cytokines and other inflammatory biomarkers simply, rapidly, and with high sensitivity.

We have been engaged in examining the utility of Arrayed Imaging Reflectometry (AIR) in the context of a project designed to examine serum levels of inflammatory biomarkers in particular as a function of human exposure to environmental (particulate) pollutants. AIR is a label-free optical detection platform, in which binding of a target analyte to a capture (probe) spot on a silicon chip causes a strong perturbation of a near-perfect antireflective condition (Lu et al., 2004; Mace et al., 2006). This is visible as an increase in reflective signal, the magnitude of which is a highly predictable function of the concentration of analyte in the sample, and the dissociation constant of the probe-analyte pair.

In preliminary work, the ability of AIR to serve as a detection method for cytokines in the complex analytical milieu of serum was demonstrated (Mace et al., 2008). While an important milestone, that work relied on manually spotted (“macro” scale) arrays and an early breadboard-level optical system, limiting the multiplex capability of the sensors under study. We now report the expansion of these preliminary efforts to the development of antibody microarrays suitable for detection of a broad range of cytokines and other inflammatory markers by AIR. Of particular importance, we find that the AIR microarray technique provides limits of detection (LODs) and coefficients of variance (CVs) comparable to ELISA assays for the majority of analytes tested, but with all of the advantages inherent to AIR as a multiplex, label-free technique.

2. Materials and Methods

Materials

6” silicon wafers diced into 10 mm × 10 mm chips and coated with approximately 1450 Å thermal oxide were supplied by the Infotonics Technology Center (Canandaigua, NY). Recombinant human antigens and monoclonal antibodies were obtained from RnD Systems (Minneapolis, MN), Biolegend (San Diego, CA), and Abnova (Taipei City, TW). Adult bovine Serum and control probe constituents, monoclonal anti-fluorescein and human serum albumin (IgG free, ≥ 99% purity) were supplied by Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). A 99% pure 3-aminopropyltriethoxy silane was acquired from Gelest Inc. (Morrisville, PA) for use in functionalizing the thermal oxide surface. EM-grade glutaraldehyde, used for crosslinking the antibody to the immobilized silane, was supplied by EMS Diasum (Hatfield, PA). Additional ACS grade chemicals employed during the sensor preparation process were acquired from Mallinckrodt Baker (Phillipsburg, PA), EMD Chemicals Inc. (Gibbstown, NJ) and BDH (West Chester, PA).

Chip preparation and surface functionalization

A precision HF etch process (500:1 18-MΩH2O:HF; CAUTION: HF is highly toxic and should be used with care) was employed to reduce the thermal oxide thickness for each chip to 1390.5 ± 0.39 Å; this final oxide thickness was verified by spectroscopic ellipsometry (J.A. Woollam α-SE). Chemical preparation of the chips for antibody immobilization subsequently proceeded via a two-step process. After cleaning each etched chip with Piranha solution (3:1 conc. H2SO4: 30% H2O2; CAUTION: piranha solution is caustic, and can react vigorously with organic materials), chips were silanized (500:1 CH3OH: 50% aminopropyl triethoxy silane, 47.5% CH3OH, 2.5% H2O); 15 minutes at room temperature with shaking), rinsed thoroughly with absolute methanol, and baked at 120 °C for 15 minutes. This was followed by a 10-minute buffer rinse in PBS (pH 7.2) to remove non-bonded silane derivatives. Glutaraldehyde deposition was then carried out, using a solution of 1.25% glutaraldehyde in PBS, pH 7.2, 60 minutes at room temperature. Chips were then rinsed with additional PBS, then briefly with 18M∧H2O, and dried under a stream of N2.

Microarray preparation

All experiments were conducted in at least duplicate. The activity of purchased antibodies was verified immediately prior to use by dot blot. Antibody arrays for all experiments except those involving detection in 20% serum were fabricated using a ChipWriter Pro microarray printer (Virtek, Waterloo, Ontario CA), with probes spotted using stealth 2.5XB slotted pins (TeleChem International, Sunnyvale, CA) in a 70% RH atmosphere. Each antibody was arrayed in a spotting solution augmented with either 0.1% DMSO or 0.1% 12-crown-4 (12-C-4), additives used to improve spot morphology (discussed further in the “results” section below). Following a brief immobilization (30 minutes) the sensors were blocked with 10 mg/mL BSA in HEPES Buffered Saline (HBS), pH 7.2 for 40 minutes, after which each sensor was exposed to a target solution. Target solutions consisted of positive (recombinant human protein at a concentration of 1 µg/mL to 1 pg/mL, diluted using 1:10 serial dilutions in 10 mg/mL (1%) BSA in PBS with 3 mM EDTA and 0.005% Tween-20 (PBS-ET), or negative (1% BSA in PBS-ET) solutions. Following target exposure, sensors were rinsed briefly in PBS, then in 18 MΩH2O. Each sensor was then dried under a stream of N2 and imaged on an AIR Microarray Reader (Adarza Biosystems, Inc.). During the course of this work we acquired an S3 sciFLEXARRAYER (Scienion AG, Dortmund Germany) piezo electric arrayer, and this system was employed for the preparation of sensors used with 20% serum solutions. Using this system, arrays were fabricated via ejection of a single 200 pl droplet of each probe solution per spot onto AIR sensor substrates functionalized as discussed above in an 85% RH atmosphere.

Image acquisition

All images were acquired in TIFF format on a commercially available AIR Microarray Reader (Adarza BioSystems) operating with 632.8 nm illumination at an incident angle of 70.75 degrees. Integration times ranged from 100 ms to 500 ms. This system has an imaging resolution of <10 µm, allowing each 100 µm probe spot on the fabricated arrays to be sharply resolved.

Image analysis

All spot intensities for each microarray sensor were determined using NIH-ImageJ v. 1.41 (Abramoff et al., 2004). Spot intensities (R) within each column of replicate spots were first averaged, and then corrected for the signal obtained from the negative control solution-exposed sensor, yielding the change in reflectance (ΔRRaw) for the probe exposed to the analyte at a given concentration. These ΔRRaw values were then normalized to a reference nonreactive spot (either anti-FITC or 1% Human Serum Albumin (HSA)) to correct for small variations in the final chip thicknesses, to yield normalized ΔR for each analyte, using the equation:

Normalized ΔR values were then plotted as a function of analyte concentration.

ELISA assays

In order to validate the use of the AIR microarray sensor against a “gold standard” technique, Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays (ELISA) were carried out for each protein as a comparison. In brief, ELISA kits were procured from commercial suppliers (Macrophage Inflammatory Protein-2: Immuno-Biological Laboratories America; Tissue Factor: American Diagnostica, Inc.; all others: R&D Systems, Inc.) and prepared as per the protocol provided. To parallel AIR sensor performance measurements, target proteins were spiked in a 1% dilution of bovine serum in PBS-ET at the identical concentration as the stock standard protein provided with the ELISA kit and subsequently run simultaneously with the standard protein (both in duplicate). Detection curves were generated from the measured optical density (OD) of the resulting dye at 450 nm for each protein dilution. Correction via subtraction of OD of the diluent and subsequent plotting of absorption values as a function of concentration yielded the statistically significant detection limit (after applying error bars equivalent to 1σ).

3. Results and Discussion

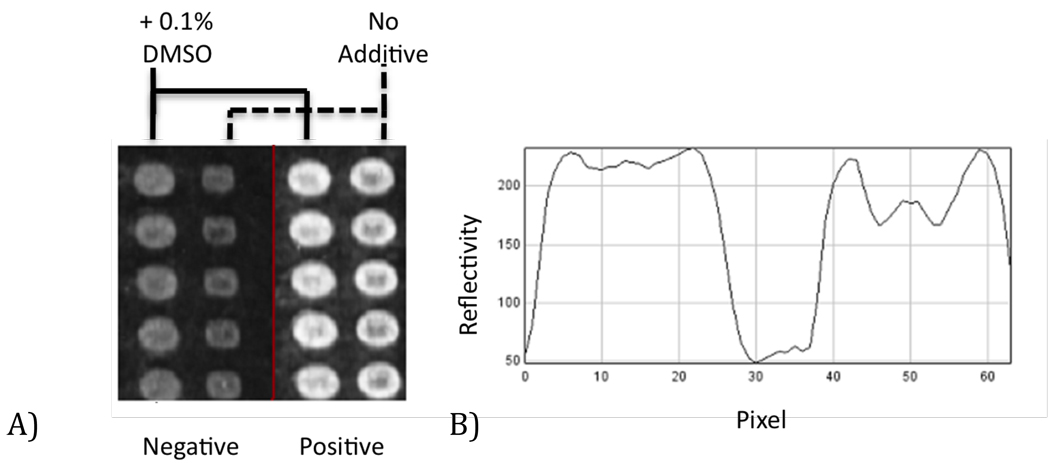

Previous experiments have shown the utility of non-nucleophilic additives in improving spot morphology in the context of “macro” AIR arrays (Mace et al., 2008). To evaluate if this held true for AIR microarrays, we printed parallel columns of anti IL-6 with and without 0.1% DMSO, shown below in Figure 1. Inclusion of DMSO in the spotting solution significantly improves overall microarray spot morphology, reducing “coffee stain” (Deng et al., 2006; Deegan et al., 1997) artifacts. Similar results were obtained with 0.1% 12-C-4 as an additive.

Figure 1.

A) An array excerpt highlighting the morphology of columns of anti IL-6 antibody spots (approximately 100 µm diameter), with and without inclusion of 0.1% DMSO in the spotting solution. The morphology of both the negative control (buffer exposed) and positive (1 µg/mL IL-6 in 1% BSA exposed) spots are greatly improved by inclusion of the additive. B) Cross section of two spots from the target exposed sensor, indicating that the “coffee stain” morphology (right portion of the profile) is significantly reduced via addition of 0.1% DMSO (left portion of the profile).

When exposed to 1.0 µg/mL target, as demonstrated above in Figure 1, an increase in spot reflectivity indicated that antibodies survived the arraying process and retained activity when covalently attached to the glutaraldehyde surface. While immobilization of antibodies via nonselective imine formation has several undesirable characteristics (most notably, a lack of control over antibody orientation), thus far we have not found more complex and site-directed immobilization schemes such as protein A, G, or A/G to provide any performance benefit on the AIR platform, in contrast to results reported for other sensor systems (Kausaite-Minkstimiene et al., 2010).

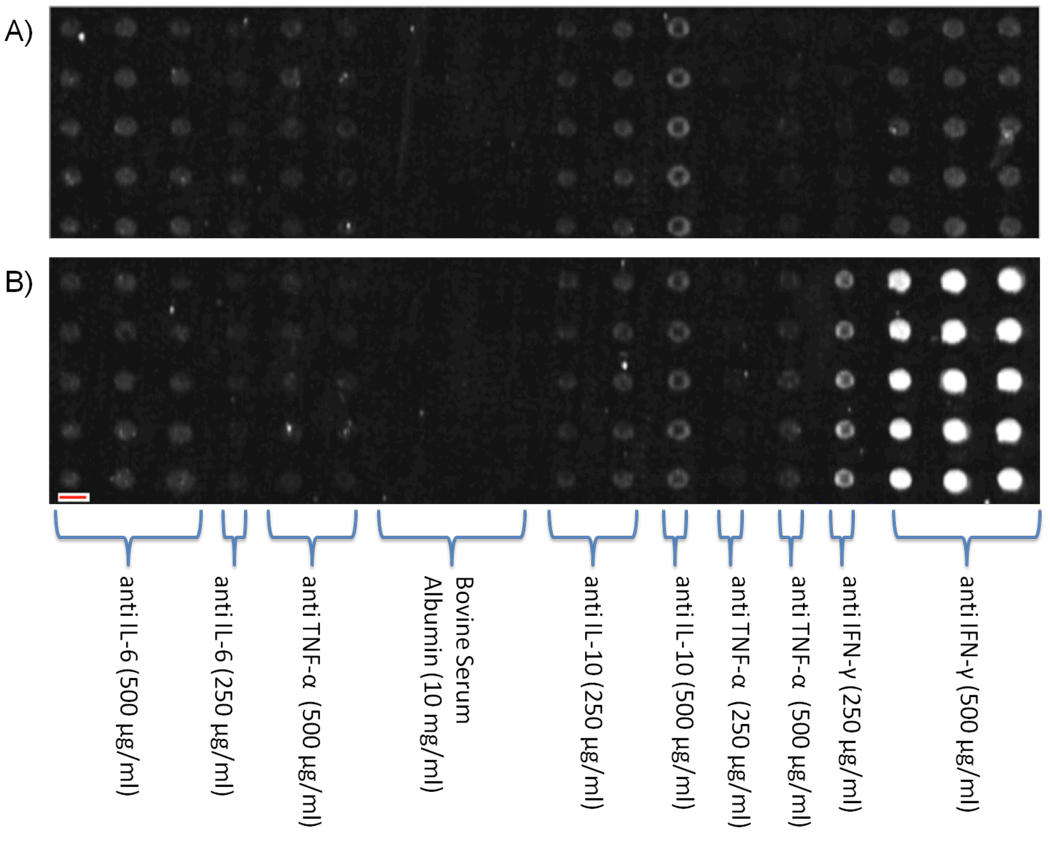

For any antibody microarray, the printed antibody density is an important experimental variable to optimize. This is particularly true in label-free techniques such as AIR: one wants as much active antibody on the surface as possible so as to maximize the amount of potential signal (binding sites for the target analyte), but avoiding steric crowding effects is also essential. Therefore, we next printed a series of arrays with varying antibody concentration, on the assumption that a saturating antibody level would be reached, beyond which no further improvements (or perhaps even decreases) in detection capability would be observed. Surprisingly, we found that chip activity continued to increase up to a concentration of 500 µg/mL antibody in the spotting solution. Higher concentrations were deemed uneconomical and were not explored. A representative example of these experiments is shown in Figure 2, with corresponding array geometry consisting of 5 replicate probes arranged in columns as identified within the figure. The top array (Figure 2a) shows 18 columns of various antibodies and concentrations printed with 5 duplicate rows after exposure to a negative control solution (10 mg/mL BSA). An identical array (Figure 2b) was exposed to a solution containing 1.0 µg/mL IFN-γ in 10 mg/mL BSA; this concentration provides a saturating response by the columns of anti IFN-γ antibodies. Two additional observations immediately apparent from the results of this experiment include the fact that the nonselective immobilization protocol nevertheless yields strong detection (consistent with prior results on “macro” spotted AIR sensors), and that essentially no cross-reactivity is observed (confirmed in a similar manner for all 14 antibodies included on the sensor). The latter confirms the multiplex capability of AIR, as long as sufficiently selective antibodies are chosen. Based on these results, the 500 µg/mL antibody spotting concentration was used for all remaining experiments.

Figure 2.

A) Negative control solution (10 mg/mL BSA) exposed sensor excerpt, showing 18 columns of 5 replicate spots (totaling 90 spots) of either monoclonal antibodies or purified proteins. B) An identical sensor excerpt exposed to 1.0 µg/mL IFN-γ in 1% BSA. Note, the red bar overlaid on the lower-left region of the sensor represents 100 µm in length; thus, each chip image corresponds to an area approximately 5 mm × 1 mm.

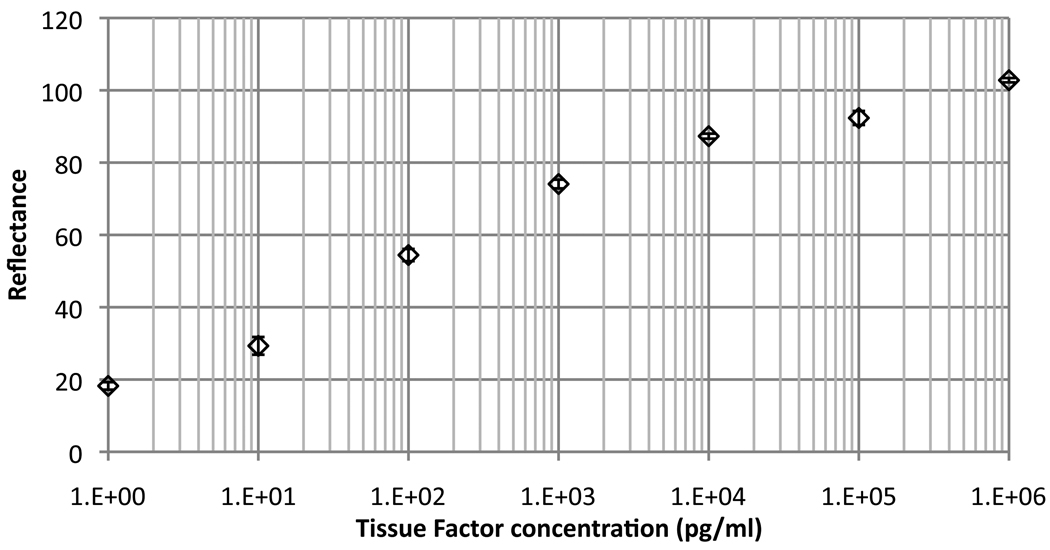

With a set of optimized conditions in hand for preparing arrays, we next turned to determining the detection capabilities of the AIR cytokine microarrays. Initial experiments were conducted in a background of 10 mg/mL BSA. Titration experiments for the majority of analytes examined showed lower limits of detection in the low pg/mL range, with most analytes giving useful detection over five logs in concentration. A representative plot for detection of Tissue Factor (TF, or CD142) is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

A representative concentration profile showing the response of an AIR microarray to varying concentrations of Tissue Factor (TF) in buffer containing a background of 10 mg/mL BSA. The lower limit of detection (LOD) for this analyte was determined to be below 1 pg/mL, as our unexposed control chip has zero normalized reflectance on this scale.

Applying this method to 14 cytokines and other immune system markers yielded a pool of sensitivity limits, summarized in Table 1. To assess intra-assay (spot-to-spot within a chip) variability, we calculated the mean Coefficient of Variation (CV) for each normalized ΔR value. This method is frequently applied to determine assay precision with data dimensionality spanning several log10 (Reed et al., 2002).

Table 1.

AIR Sensor dynamic range (expressed as upper and lower detection limit in units of pg/mL) and mean coefficient of variation (unoptimized) describing intra-assay variability.

| Protein Type | Protein | Demonstrated Detectable Range (pg/mL) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Limit |

Lower Limit |

||||

| Pro / anti – inflammatory mediators | Interleukin 1α | 1×106 | 10 | 4.61 | |

| Interleukin 1β | 1×106 | 10 | 6.44 | ||

| Interleukin 6 | 1×106 | 1 | 9.84 | ||

| Interleukin 8 | 1×106 | 1 | 3.66 | ||

| Interleukin 10 | 1×106 | 10 | 11.36 | ||

| Macrophage | 1×106 | 1 | 11.6 | ||

| Inflammatory Protein-2 | |||||

| Intracellular Adhesion | 1×106 | 10 | 15.35 | ||

| Molecule-1 | |||||

| Tumor Necrosis Factor α | 1×106 | 100 | 16.37 | ||

| Interferon γ | 1×106 | 1 | 4.30 | ||

| Oxidative Stress Related | Heme Oxygenase-1 | 1×106 | 2.5 | 8.90 | |

| Matrix | 1×106 | 100 | 16.3 | ||

| Metalloproteinase 7 | |||||

| Matrix | 1×106 | 100 | 4.06 | ||

| Metalloproteinase 10 | |||||

| Acute Phase/Coagulation | Plasminogen Activator | 1×106 | 7.6 | 9.09 | |

| Inhibitor-1 | |||||

| Tissue Factor | 1×106 | 1 | 4.76 | ||

Likewise, AIR microarrays could be employed in a multiplex detection format without significant loss of performance. In these experiments, sensors were exposed to mixtures of at least two analytes spiked into the same target solution. Applying this method to all of the protein markers shown in Table 1 yielded generally excellent congruence between ΔR values recorded for most “singleplex” and multiplex detection. We determined the congruence between sensors exposed to a specific target in a singleplex and multiplex hybridization format using a simple comparison between both reflectance values:

Applying this method to all 14 analytes yielded congruencies ranging between 85.2% (Interleukin 1α, the worst case) and 97.1% (Heme Oxygenase-1, the best case). We anticipate that further optimization will improve multiplex performance of those few analytes not performing at ideal levels; these differences primarily appear to result from chip-to-chip experimental error rather than issues with multiplexing per se.

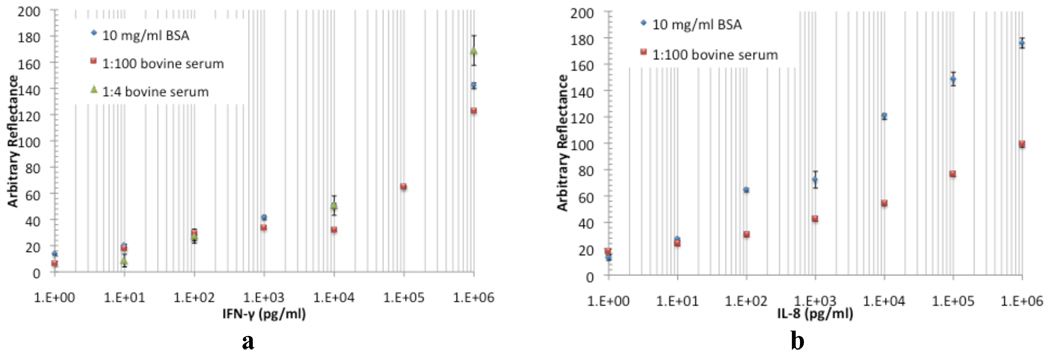

While sensor performance in buffered solutions is important, an obviously more challenging and biomedically relevant detection environment is that provided by the complex milieu of human serum. As a model for this, we therefore next examined the response of AIR microarrays in the context of protein-spiked samples in 1:100 diluted bovine serum. Bovine serum was chosen in part because of its ready commercial availability, and more importantly in order to avoid complications from the presence of endogenously-expressed proteins (as would be the case with human serum). Representative results for these experiments are shown in Figure 4. For the majority of analytes (such as IFN-γ, Figure 4a), the shape and intensity of the titration curves in low-complexity (10 mg/mL BSA) and serum backgrounds are virtually identical. A few (for example, IL-8, Figure 4b) show a decrease in overall intensity, particularly at higher concentrations. This latter result potentially reflects a greater sensitivity to nonspecific binding and/or cross-reactive binding of serum constituents to the immobilized anti IL-8 antibody. Since this may be corrected in unknown samples via the use of a calibration curve, we do not anticipate that it will be a significant barrier to effective use of the technique with these targets. Nevertheless, we are currently exploring other antibodies and washing procedures to reduce the effect.

Figure 4.

Representative comparisons of sensor performance for detection of IFN-γ (a) and IL-8 (b) in backgrounds of 10 mg/mL BSA, in 1:100 bovine serum, and in (for IFN-γ) 1:4 bovine serum. All reflectance values are corrected relative to the background reflectance value at zero concentration.

In previous work (Mace et al, 2008), Mace et al. demonstrated detection of IFN-γ in undiluted human serum using hand-spotted AIR arrays. To verify that microarray-format AIR was capable of effective protein detection in higher serum concentrations, we repeated the IFN-γ experiment in 20% bovine serum. Incorporating a small amount of detergent (0.1% Tween-20) into the 15 minute post-exposure wash procedure was found to be essential to reduce nonspecific binding. Doing so yielded a binding curve similar to that obtained in 1% serum, and an LOD of 10 pg/mL (Figure 4a).

The “gold standard” for protein detection in most laboratories is, of course, the ELISA assay. To examine the question of how microarray AIR performance compares to singleplex ELISA, we compared data acquired using microarray AIR with results from commercial ELISA kits on identical samples. In the majority of cases, microarray AIR performed as well or better than the singleplex ELISA kit with regard to LOD; ELISA performance in our hands was consistent with manufacturer-reported limits (Table 2). While these results must be viewed as somewhat anecdotal rather than a full validation (as differences in antibodies used in the commercial kits vs. those employed in our microarray AIR experiments preclude a thorough head to head comparison), they nonetheless show the functional potential of microarray AIR to serve as an effective method for multiplex, quantitative cytokine detection.

Table 2.

ELISA detection limits of marker proteins as compared to the observed detection limit via AIR. Both the ELISA kit stated dynamic range of detection and experimentally verified lower detection limit is provided in units of pg/mL

| Protein Type | Protein | Elisa Performance (pg/mL) |

AIR Detection Limit (pg/mL) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range of Detection (Stated) |

Detection Limit (Experimental) |

|||

| Pro / Anti – Inflammatory Mediators | Interleukin 1α | 250–3.9 | 3.9 | 10 |

| Interleukin 1β | 1000–12.5 | 62.5 | 10 | |

| Interleukin 6 | 1000–12.5 | 7.8 | 1 | |

| Interleukin 8 | 1000–3.9 | 3.9 | 1 | |

| Interleukin 10 | 250–3.9 | 3.9 | 10 | |

| Intracellular | 50000–1560 | 1560 | 10 | |

| Adhesion Molecule-1 | ||||

| Tumor Necrosis | 5000–7.8 | 15.6 | 100 | |

| Factor α | ||||

| Interferon γ | 1000–7.8 | 7.8 | 1 | |

| Heme Oxygenase-1 | 25000–780 | 1560 | 2.5 | |

| Matrix | 10000–312 | 312 | 100 | |

| Metalloproteinase 7 | ||||

| Oxidative Stress Related | Matrix | 5000–78.1 | 156 | 100 |

| Metalloproteinase 10 | ||||

| Plasminogen | 20000–312 | 625 | 7.6 | |

| Activator Inhibitor-1 | ||||

| Tissue Factor | 250–3.9 | 1.56 | 1 | |

4. Conclusions

We have demonstrated that Arrayed Imaging Reflectometry can serve as a robust platform for the detection of cytokines and other inflammatory biomarkers in buffered BSA solutions and in 1:100 dilutions of serum. Microarray-based detection of IFN-γ in 20% serum was likewise successful, with similar limits of detection to those seen for higher serum dilutions. Performance metrics are comparable to or better than common “singleplex” ELISA assays, while providing the advantages inherent in a multiplex, low volume, label-free format. Like all label-free technologies, control over nonspecific binding becomes critical as higher concentrations of serum are used. Efforts to further examine sensor performance in the context of patient samples as well as expand upon assay content are in progress.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Günter Oberdörster (University of Rochester) for helpful discussions regarding biomarker target selection, and the NIH (Grant#1R43ES016406-01 and Grant R24-AL054953, the latter via the Human Immunology Center at the University of Rochester) for support of this work. Additionally, we acknowledge Jessica Katolik (Adarza Biosystems) for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abramoff MD, Magelhaes PJ, Ram SJ. Biophotonics Int. 2004;11:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Blicharz TM, Siqueira WL, Helmerhorst EJ, Oppenheim FG, Wexler PJ, Little FF, Walt DR. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:2106–2114. doi: 10.1021/ac802181j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carboni L, Becchi S, Piubelli C, Mallei A, Giambelli R, Razzoli M, Mathé AA, Popoli M, Domenici E. Prog. Neuropsych. Biol. Psych. 2010;34:1037–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deegan RD, Bakajin O, Dupont TF, Huber G, Nagel SR, Witten TA. Nature. 1997;389:827–829. doi: 10.1103/physreve.62.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y, Zhu X-Y, Kienlen T, Guo A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:2768–2769. doi: 10.1021/ja057669w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groneberg DA, Chung KF. Respir. Res. 2004;5:18. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-5-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haarmann-Stemmann T, Bothe H, Abel J. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2009;77:508–520. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kausaite-Minkstimiene A, Ramanaviciene A, Kirlyte J, Ramanavicius A. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:6401–6408. doi: 10.1021/ac100468k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Strohsahl CM, Miller BL, Rothberg LJ. Anal. Chem. 2004;76:4416–4420. doi: 10.1021/ac0499165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mace CR, Striemer CC, Miller BL. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:5578–5583. doi: 10.1021/ac060473+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mace CR, Striemer CC, Miller BL. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2008;24:334–337. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mace CR, Yadav AS, Miller BL. Langmuir. 2008;24:12754–12757. doi: 10.1021/la801712m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra R, Patel V, Vaqué JP, Gutkind JS, Rusling JF. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:3118–3123. doi: 10.1021/ac902802b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed RF, Lynn F, Meade BD. Clin. Diag. Lab. Immunol. 2002;9:1235–1239. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.9.6.1235-1239.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tal TL, Simmons SO, Silbajoris R, Dailey L, Cho S-H, Ramabhadran R, Linak W, Reed W, Bromberg PA, Samet JM. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2010;243:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CC, Huang R-P, Sommer M, Lisoukov H, Huang R, Lin Y, Miller T, Burke J. J. Proteome Res. 2002;1:337–343. doi: 10.1021/pr0255203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woehrle T, Du W, Goetz A, Hsu H-Y, Joos TO, Weiss M, Bauer U, Brueckner UB, Schneider EM. Cytokine. 2008;41:322–329. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurkovetsky ZR, Kirkwood JM, Edington HD, Marrangoni AM, Velikokhatnaya L, Winans MT, Gorelik E, Lokshin AE. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007;13:2422–2428. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.