Abstract

Gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST) in pregnancy is rare. There have been only three previously reported cases, all of which have been diagnosed on postoperative histology. The authors present the first case of a preoperatively diagnosed GIST arising in a 31-year-old pregnant woman. With a suspected diagnosis, the patient was managed through a combined obstetric and upper gastrointestinal multidisciplinary team meeting, resulting in planned early caesarean section and surgical removal of the tumour. This case emphasises the fact that early and effective multidisciplinary discussion allows for proper treatment planning and more informed patient decisions.

Background

Gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs) are rare tumours of mesenchymal origin that can arise anywhere along the length of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Reported incidence ranges from 11 to14.5 per million, with approximately 800 cases in the UK per year.1–3 They are most commonly diagnosed between the fourth and eighth decades of life and are therefore rarely diagnosed in pregnancy. There have been three previously reported cases in the literature, all of which have been diagnosed on postoperative histology.4–6 We report a case of GIST in pregnancy diagnosed preoperatively and describe the multidisciplinary management of this unusual presentation.

Case presentation

A 31-year-old female, gravida 1 para 1, presented in the 16th week of gestation to her general practitioner with lethargy, dizziness and a sensation of an abdominal mass. She was otherwise well with no significant medical history. Physical examination revealed a solid mobile abdominal mass and laboratory investigations revealed anaemia (haemoglobin 7.3 g/dl).

Investigations

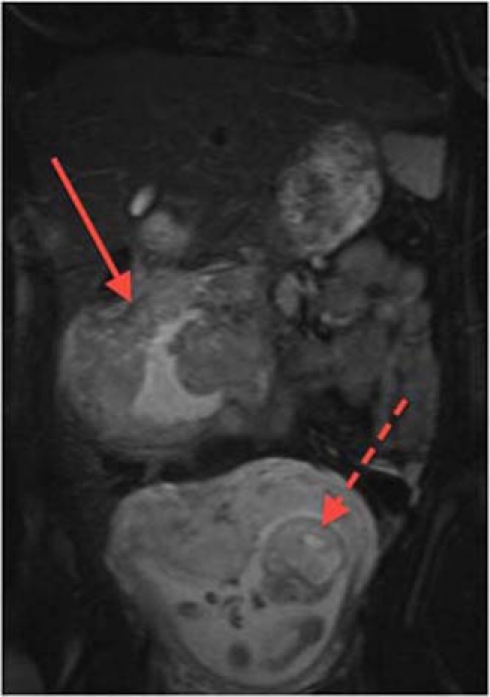

Abdominal ultrasound revealed a 12 cm bulky mass just right of the midline in the lower abdomen. An MRI scan was subsequently performed which demonstrated a large 12 cm soft tissue mass with central necrosis that was confined to the transverse mesocolon and the mesentery of the small intestine (figure 1). Due to a degree of diagnostic uncertainty, an ultrasound-guided biopsy was performed at 19 weeks gestation. Histology confirmed a GIST.

Figure 1.

Abdominal MRI of the patient with the GIST visible superiorly (solid arrow) and the fetus inferiorly (dotted arrow).

Differential diagnosis

-

▶

Bowel cancer

-

▶

Bleeding into a mesenteric cyst

-

▶

Ovarian cancer.

Treatment

The case was discussed at the upper GI multidisciplinary meeting with the obstetrician present. The balance between the need for urgent treatment to resect the bowel tumour and the mother’s wish to continue with the pregnancy without the risk of spontaneous abortion or neonatal complication was considered. It was decided that the safest option would be an elective caesarean section with immediate laparotomy to resect the GIST. A decision was made to perform surgery at 36 weeks gestation. The patient underwent an uncomplicated caesarean section and a 2.15 kg baby girl was born. The operation was continued whereby a 2.5 kg (17 cm × 14 cm × 12 cm) mass was found to be arising from the transverse mesocolon, attached to the wall of the colon, and was removed en bloc with a right hemicolectomy and small bowel resection.

Outcome and follow-up

Final histology confirmed a spindle cell GIST with frequent mitoses (22 mitoses per 50 high power fields). Immunohistochemistry showed strong positivity CD117, focal positivity for CD 34, occasional positivity for smooth muscle actin and negative for desmin. The tumour was assessed to be of high risk of recurrence, with a risk of recurrence of approximately 90% on the basis of tumour size, site and mitotic activity.7 Both the patient and her child made an uneventful postoperative recovery. On discharge, a staging CT showed no signs of distant metastases, and the patient was referred to a specialist soft tissue sarcoma oncologist to consider adjuvant imatinib (Glivec) therapy. After discussion, she decided to take adjuvant imatinib in view of her high risk of relapse, but elected not to breast feed.

Discussion

GISTs were first identified as a separate clinicopathological entity in 19838 having previously been classified as a range of other smooth muscle tumours arising from the GI tract, including leiomyomas, leiomyosarcomas and schwanomas. They are now recognised to arise from the same mesenchymal stem cell precursor as interstitial cells of Cajal, the autonomic pacemaker cells of the GI tract. GISTs express the KIT protein (CD117), which is a trans-membrane cell surface receptor with tyrosine kinase activity, encoded by the c-KIT gene. Activating mutations in c-KIT leads to the KIT receptor being ‘always on’, resulting in persistent downstream signalling conferring a growth and survival advantage to the cell. The KIT protein is detectable on immunostaining in >95% of cases, which is used diagnostically.

Population-based studies have shown a roughly equal gender distribution,1–3 with the median age at diagnosis between 66 and 69 years. GIST is rare under the age of 21 years, with this age group accounting for fewer than 3% of tumours. The commonest presentation is bleeding either into the GI tract or anaemia. However, patients may also present with pain or abdominal discomfort, or an asymptomatic abdominal mass. Other symptoms at presentation may be due to bowel obstruction or non-specific abdominal symptoms such as pain, bloating and weight loss.9 10 The symptoms of presentation during pregnancy are in keeping with these previous studies (table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of three previously reported cases (cases 1–3) of GIST in pregnancy with the current case (case 4)

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 32 | 29 | 25 | 31 |

| Gestation | 28 | 22 | 10 | 36 |

| Fundal height | 36 | N/A | 24 | 36 |

| Separate abdominal mass | No | No | No | Yes |

| Presenting symptom | Pain | Pain | Asymptomatic | Symptomatic anaemia |

| USS findings | Ascites and mass | Ascites | Mass | Mass |

GISTs are resistant to chemotherapy and radiotherapy and until recently local recurrence or distant metastases were associated with poor outcome. The best chance of cure at initial presentation is complete surgical resection of disease. It is therefore important that there is no rupture of the tumour at operation, and any adjacent involved organs are removed en bloc with the primary tumour to achieve clear margins. Metastases may occur via local spread to the peritoneum or via the haematogenous route to the liver, but spread to lymph nodes is rare and therefore nodal clearance is unnecessary. Various other histopathological factors have been associated with increased risk of recurrence, the most important being mitotic index and tumour size.7 11 Small tumours with a low mitotic index have the best prognosis. Gastric GISTs also have a better outcome than tumours found elsewhere in the GI tract.

Preoperative diagnosis allows for better treatment planning using a multidisciplinary approach. Unlike the previous case reports a provisional diagnosis of GIST had been made preoperatively and the patient had been discussed at the local upper GI multidisciplinary team meeting (MDT) with involvement of the obstetricians. Trans-abdominal trucut biopsy of the mass under image guidance had been performed. This is controversial as there is a small theoretical risk of tumour seeding the abdominal cavity or causing haemorrhage. In cases where GIST is suspected, primary resection of the mass en bloc is recommended.12 Biopsy is reserved for cases of unresectable or metastatic tumour where histology is needed to confirm the diagnosis before consideration of chemotherapy, or for cases where there is diagnostic uncertainty (eg, suspected lymphoma). Where biopsy is indicated recommendation has been made that this be undertaken endoscopically, as this possibly decreases the risk of abdominal cavity dissemination, and with the use of endoscopic ultrasound guidance, as this increases the chances of an adequate biopsy. In this case there was diagnostic uncertainty, and given the fact that she presented in the 16th week of gestation, the management would have changed if this was another tumour type. Percutaneous Trucut biopsy was probably safer than endoscopic examination, which would have required full bowel preparation and colonoscopy. In two of the previously reported cases an attempt at preoperative diagnosis had been made. Ascitic fluid was sent for cytology but in both cases this was negative despite one of the cases having peritoneal metastases. In our case, preoperative diagnosis enabled careful planning of a surgical procedure that combined a caesarean section with definitive primary resection of the tumour, the latter offering the patient the best opportunity of an optimal outcome. With regards to timing of delivery and surgery, the authors accept that there is no definitive evidence to quantify the risk of tumour progression over time or predict potential tumour complications, such as bleeding. This was balanced against the increased risks of neonatal complications of a preterm birth, which decreases with gestational age.13 It was the feeling of the MDT that it was unwise to allow a spontaneous delivery and therefore elective section at 36 weeks was agreed.

Imatinib is a selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor of the mutant KIT receptor. It has been used with great success in the treatment of recurrent/metastatic GIST, with patients responding on average for 24 months.14 15 It has also been investigated in the neo-adjuvant setting with advanced primary and metastatic/recurrent disease and early results are available.16 This approach would not have been suitable in this case, however, due to pregnancy and the potential teratogenic effects of imatinib, and the disease was in any case primarily resectable. The recent ACOSOG 9001 randomised controlled trial has shown a reduction in recurrence rates with 1 year of adjuvant imatinib in KIT positive GIST >3 cm in size started within 12 weeks of surgery, although it is not known yet whether adjuvant treatment confers a survival benefit.17 Results of two completed European studies are awaited (European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer study 62024 and Scandinavian Sarcoma Group Trial XVIII) and will hopefully provide additional evidence as to the precise nature of benefit of imatinib in the adjuvant setting and optimal duration of therapy. Our patient had a tumour that was judged, despite a complete surgical resection, to have a risk of recurrence of approximately 90%. After discussion with her oncologist, she elected to be treated with adjuvant imatinib for 2 years, accepting the uncertainties of overall survival benefit. The use of imatinib in the adjuvant setting has recently been evaluated by NICE, and was not approved. However, this decision came after our patient required treatment, and her imatinib is funded by her primary care trust following a successful high cost drug funding application. She decided not to breast feed because of the possibility of drug-related toxicity to her baby, and because she was also unwilling to defer imatinib treatment until after she had finished breast feeding. Novartis, the manufacturer of imatinib recommends that women should not breast feed while taking imatinib. A case report in which imatinib levels where checked in maternal plasma and breast milk in a woman who did breast feed while taking imatinib, indicated that in fact the breast milk levels were approximately 10% of the therapeutic dose.18 However, while the authors suggest that breast feeding may be safe in the short term, they highlight the uncertainties of chronic expose in newborn babies.

Learning points.

-

▶

GIST in pregnancy is very rare.

-

▶

Confirmed histological diagnosis in previous case reports has only been made postresection.

-

▶

Early diagnosis with appropriate multidisciplinary management is essential to ensure optimal surgical management and outcome.

-

▶

Prompt referral to a specialist oncologist allows for consideration of adjuvant imatinib.

Footnotes

Competing interests None.

Patient consent Obtained.

References

- 1.Nilsson B, Bümming P, Meis-Kindblom JM, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: the incidence, prevalence, clinical course, and prognostication in the preimatinib mesylate era–a population-based study in western Sweden. Cancer 2005;103:821–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tryggvason G, Gíslason HG, Magnússon MK, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors in Iceland, 1990-2003: the icelandic GIST study, a population-based incidence and pathologic risk stratification study. Int J Cancer 2005;117:289–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goettsch WG, Bos SD, Breekveldt-Postma N, et al. Incidence of gastrointestinal stromal tumours is underestimated: results of a nation-wide study. Eur J Cancer 2005;41:2868–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valente PT, Fine BA, Parra C, et al. Gastric stromal tumor with peritoneal nodules in pregnancy: tumor spread or rare variant of diffuse leiomyomatosis. Gynecol Oncol 1996;63:392–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lanzafame S, Minutolo V, Caltabiano R, et al. About a case of GIST occurring during pregnancy with immunohistochemical expression of epidermal growth factor receptor and progesterone receptor. Pathol Res Pract 2006;202:119–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scherjon S, Lam WF, Gelderblom H, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor in pregnancy: a case report. Case Report Med 2009;2009:456402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: pathology and prognosis at different sites. Semin Diagn Pathol 2006;23:70–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazur MT, Clark HB. Gastric stromal tumors. Reappraisal of histogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol 1983;7:507–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miettinen M, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 1765 cases with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:52–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miettinen M, Makhlouf H, Sobin LH, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the jejunum and ileum: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 906 cases before imatinib with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol 2006;30:477–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A consensus approach. Hum Pathol 2002;33:459–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demetri GD, Benjamin RS, Blanke CD, et al. NCCN Task Force report: management of patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST)—update of the NCCN clinical practice guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2007;5(Suppl 2):S1–29;quiz S30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Copper RL, Goldenberg RL, Creasy RK, et al. A multicenter study of preterm birth weight and gestational age-specific neonatal mortality. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1993;168(1 Pt 1):78–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Glabbeke MM, Owzar K, Rankin C, et al. GIST Meta-analysis Group (MetaGIST). Comparison of two doses of imatinib for the treatment of unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST): a meta-analysis based on 1,640 patients (pts). J Clin Oncol (Meeting Abstracts) 2007;25:10004 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blanke CD, Demetri GD, von Mehren M, et al. Long-term results from a randomized phase ii trial of standard- versus higher-dose imatinib mesylate for patients with unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors expressing KIT. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:620–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisenberg BL, Harris J, Blanke CD, et al. Phase II trial of neoadjuvant/adjuvant imatinib mesylate (IM) for advanced primary and metastatic/recurrent operable gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST): early results of RTOG 0132/ACRIN 6665. J Surg Oncol 2009;99:42–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dematteo RP, Ballman KV, Antonescu CR, et al. Adjuvant imatinib mesylate after resection of localised, primary gastrointestinal stromal tumour: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2009;373:1097–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gambacorti-Passerini CB, Tornaghi L, Marangon E, et al. Imatinib concentrations in human milk. Blood 2007;109:1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]