Abstract

Salmonella are successful pathogens that infect millions of people every year. During infection, Salmonella typhimurium changes the structure of its lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in response to the host environment, rendering bacteria resistant to cationic peptide lysis in vitro. However, the role of these structural changes in LPS as in vivo virulence factors and their effects on immune responses and the generation of immunity are largely unknown. We report that modified LPS are less efficient than wild-type LPS at inducing pro-inflammatory responses. The impact of this LPS-mediated subversion of innate immune responses was demonstrated by increased mortality in mice infected with a non-lethal dose of an attenuated S. typhimurium strain mixed with the modified LPS moieties. Up-regulation of co-stimulatory molecules on antigen-presenting cells and CD4+ T-cell activation were affected by these modified LPS. Strains of S. typhimurium carrying structurally modified LPS are markedly less efficient at inducing specific antibody responses. Immunization with modified LPS moiety preparations combined with experimental antigens, induced an impaired Toll-like receptor 4-mediated adjuvant effect. Strains of S. typhimurium carrying structurally modified LPS are markedly less efficient at inducing immunity against challenge with virulent S. typhimurium. Hence, changes in S. typhimurium LPS structure impact not only on innate immune responses but also on both humoral and cellular adaptive immune responses.

Keywords: antibody response, innate immunity, lipopolysaccharide, Salmonella, Toll-like receptor 4

Introduction

In developed countries, non-typhoidal Salmonella are a major cause of food-borne infection outbreaks. In non-industrialized countries, non-typhoidal Salmonella have a staggering impact on public health and on the economy. It is therefore important to understand the mechanisms that Salmonella uses to avoid immune responses, thereby making it a successful and widespread pathogen.1,2

Immunity to pathogens such as Salmonella requires the early induction of an innate immune response that efficiently induces the activation of T-cell-mediated and B-cell-mediated immune responses.3 Initial recognition of pathogens is mediated by pattern recognition receptors including Toll-like receptors (TLRs). The TLR signalling is also important for the induction, maintenance and fine-tuning of the adaptive immune response.3,4 In particular, the heterodimer TLR4/MD-2 recognizes the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) Lipid A that represents the conserved molecular pattern of LPS and is the main inducer of immunological responses such as the release of inflammatory mediators, endotoxin activity and adjuvant properties.5–7 Lipid A structures vary among microorganisms, and are sensed by host cells, generating differential cytokine production by distinct dendritic cell (DC) subsets as well as diverse types of T-cell responses. In vitro, hexa-acylated but not penta-acylated LPS from Pseudomonas aeruginosa triggers a robust pro-inflammatory response in human cells that is mediated by TLR4.8,9 Additionally, differential responses are observed when chemically synthesized lipid A is used.10

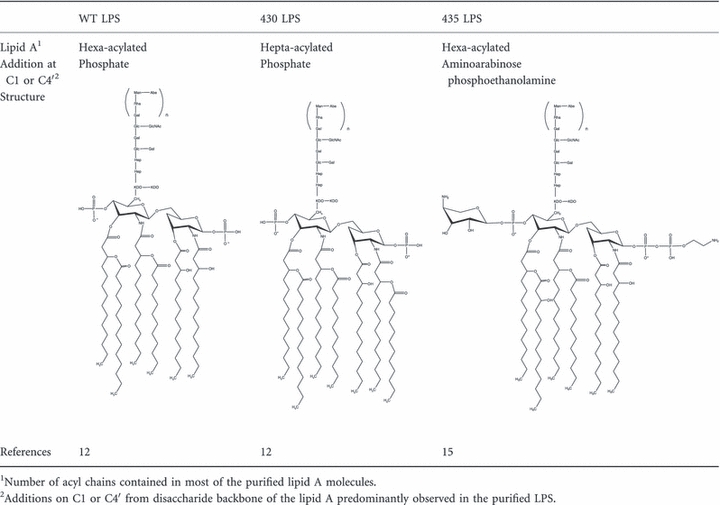

To survive the host response, Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium (S. typhimurium), activate the co-ordinated expression of virulence factors such as the PhoP/PhoQ-PmrA/PmrB two-component systems (PhoPQ-PmrAB TCS) which responds to low concentrations of divalent cations, low pH and the presence of anti-microbial peptides.11 Among the effects mediated by PhoPQ-PmrAB activation are changes in the structure of LPS lipid A. Table 1 summarizes the main modifications and chemical structures of the different S. typhimurium purified LPS moieties regulated by PhoPQ-PmrAB TCS, here referred as wild-type (WT) LPS (from S. typhimurium 14028s strain), 430 LPS (from S. typhimurium PhoPc strain) and 435 LPS (from S. typhimurium PmrAc strain). The 430 LPS induces lower expression of E-selectin in human umbilical vein endothelial cells and reduced tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) expression in murine monocytes.12 The 435 strain is resistant to polymyxin and other cationic peptides whereas the 430 strain is more susceptible to polymyxin but still resistant to several other cationic peptides.13 Microvesicles derived from a PhoPc strain can diminish the specific T-cell response against multiple Salmonella antigens, indicating that LPS modifications can also affect the adaptive immune response to the bacteria.14 However, the role of these LPS structural changes in the promotion of bacterial infection in vivo and their effects on host immune responses and generation of immunity have not been addressed. Here we demonstrate that PhoPQ-PmrAB TCS-modified LPS lipid A favours S. typhimurium infections by a TLR4-dependent subversion of host innate and adaptive responses and that this hampers generation of immunity in the host.

Table 1.

Main structural modifications in the different lipopolysaccharide (LPS) lipid as observed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry

|

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

The project was approved by the Mexican Social Security Institute National Scientific Research Commission (composed by Scientific, Ethics and Bio-security Committees, Project No. 2003-716-0133 and 2004-3601-0126), and animal experiments in Switzerland were approved by the Veterinary Office of the Canton of St Gallen, under the permission numbers SG07/62 and SG07/63.

Mice

BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Harlan Mexico (Mexico D.F.) and kept at the animal facilities of the Experimental Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine, National Autonomous University of Mexico. The TLR4−/− mice on a C57BL/6 background and the control C57BL/6 mice were bred in the Institute of Immunobiology, Cantonal Hospital, St Gallen (St Gallen, Switzerland). B10.BR and 3A9 [hen egg lysozyme (HEL) transgenic mice] were bred in the Experimental Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine, National Autonomous University of Mexico.

Bacteria and growth conditions

The strains used were: S. typhimurium WT ATCC 14028s (STWT), green fluorescent protein (GFP)-STWT (kindly provided by Dr Celia Alpuche-Aranda), S. typhimurium JSG430 (ST430) CS022 pmrA::Tn10d12, S. typhimurium JSG435 (ST435) ATCC 14028s pmrA505 zjd::Tn10d-cam15 and S. typhimurium 14028s phoP102::Tn10dCam (STPhoP−).16 All the cultures were grown to log phase in Luria–Bertani broth. For mutant strains ST430 and ST435 tetracycline (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) 50 μg/ml and chloramphenicol (Boehringer Mannheim, GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) 25 μg/ml were added to the respective cultures. Bacterial inactivation was performed at 65° for 1 hr.

LPS purification

The LPS used in this work was produced using the hot phenol procedure, and the same batches (corresponding to the different strains) of purified LPS were used for all of the experiments in this study. Preparations of LPS were subjected to Folch extraction to remove residual lipid contamination. The purity of LPS was assessed by a colloidal gold stain test for protein and a biological assay was performed using HEK293 cells constitutively expressing TLR4/MD2/CD14 or TLR2/6 or TLR5 (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA) stimulated with 10 μg/ml structurally modified LPS for 24 hr. The TLR-induced activation was measured by CXCL8/interleukin-8 (IL-8) production. Supernatants of stimulated cells were analysed by ELISA using the OptEIA human IL-8 ELISA kit (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). The LPS preparations used in this work were able to signal through TLR4/MD2/CD14 but not through TLR2/6 or TLR5.

The chemical structures of the LPS used in this work were previously reported by Gunn et al.,15 and Guo et al.12 Lyophilized LPS was weighed and diluted to the concentration required using pyrogen-free water.

Immunogens

Ovalbumin (OVA) grade VI was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO). Absence of LPS was confirmed using HEK293 cells transfected with TLR4/MD2/CD14, TLR2/6 or TLR5 and by the method reported by McSorley et al.17Salmonella enterica serovar typhi (S. typhi) porins were purified from the S. typhi (ATCC 9993), as previously described.18

Survival assay and tissue colony-forming unit determination

BALB/c mice were infected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 1 × 104 colony-forming units (CFU) of PhoP−S. typhimurium alone or mixed with 5 μg/ml of WT, 430 LPS or 435 LPS moieties. Survival was assessed 5 days after infection. Bacterial CFU in the spleen were determined by direct culturing.

Stimulation of bone-marrow-derived macrophages and determination of cytokine and NO production

Bone-marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) were obtained as described previously19 and the BMDM (1 × 106 cells) were stimulated for 6 hr with 10, 100 or 1000 ng/ml LPS from S. typhimurium WT, 430 or 435 strains. Unstimulated cells were used as controls. The TNF, IL-6, interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1)/CCL2 were quantified in culture supernatants by BD Cytometric Bead Array (BD Biosciences), following the manufacturer's instructions. The same supernatant was used to evaluate NO production by the method described by Green et al.20

Chemotaxis analysis

Peritoneal macrophages were exposed for 6 hr to 100 ng/ml WT, 430 and 435 LPS moieties. Chemotaxis assays were carried out using modified Boyden chambers (NeuroProbe Inc., Cabin John, MD) as described previously.21

In vivo DC maturation

C57BL/6 or TLR4−/− mice were injected subcutaneously with a solution containing 25 μg/100 μl WT, 430 or 435 LPS moieties or with LPS-free sterile isotonic saline solution (Saline). Six hours after injection, single-cell suspensions were prepared from spleens and stained with 1 : 100 dilution of phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD40, CD80, CD69, CD86, I-A/I-E, 1 : 500 dilution of allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-CD11c and 1 : 100 dilution of FITC-conjugated anti-B220, for 30 min. All monoclonal antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences. The cells were analysed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) using Winmdi 2.8 software (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA). Results are expressed as the mean fluorescence index that was calculated as the ratio between treated mice and mice that received saline.

In vivo T-cell proliferation assay

B10.BR mice were injected intravenously with 5 × 106 carboxyfluorosuccinimidyl ester-labelled CD4+ T cells from 3A9 mice that express a transgenic T-cell receptor restricted to HEL(46–61). One day after transfer, mice were immunized subcutaneously in the footpad with 3 μg HEL alone or co-administered with 5 μg WT, 430 or 435 LPS moieties. Three days after immunization, popliteal lymph nodes were harvested. Lymph node cells were processed for FACS analysis by staining with biotinylated anti-Vβ 8.2 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) and allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-CD4 antibodies (BD Biosciences) to assess in vivo proliferation. Lymph node cells were co-cultured for 5 hr at a ratio of 3 : 1 T cells per DC alone or loaded with HEL(46–61) peptide (Research Genetics, Huntsville, AL). Cytokines in the supernatants were quantified using T helper type 1 (Th1)/Th2 cytometric bead array assay following the manufacturer's instructions (BD Biosciences). Proliferation data were acquired on a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) and data were analysed using Flow jo 7.5 software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR).

Cytokine quantification

BALB/c mice received i.p. 5 μg WT, 430 or 435 LPS moieties alone or mixed with 1 × 104 CFU PhoP−S. typhimurium. Six hours after administration, serum samples were obtained. Cytokine levels were determined using a mouse inflammation cytometric bead array kit (BD Biosciences) and evaluated using a CyAn ADC flow cytometer (Dako, Cambridgeshire, UK). Data were analysed using Flow jo 7.5 software.

Immunizations

C57BL/6 or TLR4−/− mice were immunized i.p. on day 0 with 0·5 ml of 4 mg/ml OVA alone or mixed with 5 μg WT, 430 or 435 LPS moieties. BALB/c mice were immunized i.p. on day 0 with 0·5 ml of 20 μg/ml of porins from S. typhi alone or mixed with 5 μg WT, or 430 or 435 LPS moieties. Boosting was performed using the same antigen preparations 15 days after the first immunization. To study the antibody response to intact bacteria, groups of BALB/c mice were immunized i.p. on day 0 with 5 × 105 heat-inactivated bacteria from WT, 430 or 435 S. typhimurium strains (HISTWT, HIST430 or HIST435). Boosting was performed at day 15 using the same conditions. All control mice were injected with saline only.

Determination of antibody titres and high-affinity antibodies by ELISA

High-binding 96-well polystyrene plates (Corning, New York, NY) were coated with 10 μg/ml porins, 150 μg/ml OVA or 1 × 107 HISTWT cells suspended in 100 μl of 0·1 m carbonate–bicarbonate buffer (pH 9·5). ELISA was performed according to the procedure described previously.22

To assess the presence of high-affinity antibody responses, a 7 m urea wash was used as reported by Delgado et al.23 Antibody titres are given as −log2 dilution × 40. A positive titre was defined as 3 SD above the mean value of the negative control. Titres are expressed in the graphs as the inverse of the dilution.

Opsonophagocytic assay

J774A.1 macrophages (1 × 106 cells) were infected with 5 × 107CFU of S. typhimurium GFP either untreated or opsonized with day-30 sera from mice immunized with HISTWT, HIST430 or HIST435. After 30 min of incubation, 1 μg/ml gentamicin (Sigma-Aldrich) was added. Non-phagocytosed bacteria were removed by two washes with saline solution and the percentage of GFP-positive cells was determined using a flow cytometer (CyAn ADP; Dako). Data were analysed using Summit software v4.3 (Dako, Fort Collins, CO).

Protection assay

BALB/c mice were immunized i.p. at day 0 with 5 × 105 CFU of STPhoP− strain mixed with 5 μg WT, or 430 or 435 LPS moieties. At day 15 mice were boosted using the same preparations. At day 30 mice were challenged i.p. with 5 × 106 CFU of STWT. Mouse survival was assessed over 5 days after challenge.

Statistics

One-way analysis of variance test with Bonferroni's multiple comparison correction or Tukey test were applied. The difference in survival rates was evaluated by the log rank test (Mantel–Cox). Significant differences are indicated by asterisks and P-values < 0·05 were considered significant.

Results

Compared with WT LPS, LPS expressing lipid A structural modifications induce a dampened macrophage activation and migration

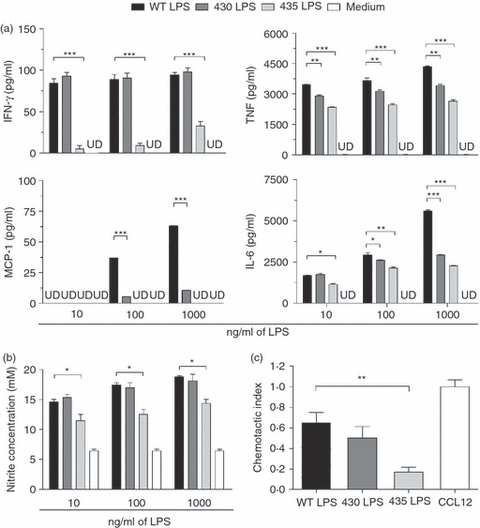

Macrophages are critically important phagocytes that recognize microbes, initiate innate inflammatory responses and participate in the clearance of bacteria during Salmonella infection.24 To evaluate the effect of structurally modified LPS moieties on these cells, BMDM were stimulated in vitro with WT or 430 or 435 LPS moieties, and TNF, IL-6, IFN-γ and MCP-1 production was quantified from cell culture supernatants. When compared with WT LPS, we observed that both 430 LPS and 435 LPS induced less production of TNF, MCP-1 and IL-6 in all doses tested. WT and 430 LPS induced similar amounts of IFN-γ whereas the 435 LPS moiety induced the lowest production of this cytokine (Fig. 1a). These results indicate that structurally modified LPS are in general less efficient than WT LPS in generating a pro-inflammatory environment.

Figure 1.

Compared with wild-type (WT), structurally modified lipopolysaccharides (LPS) induce lower macrophage activation and migration. (a) Bone-marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) were stimulated with 10, 100 or 1000 ng/ml WT, 430 or 435 LPS. Tumour necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1) production was analysed in the supernatants after 6 hr by flow cytometry using a cytokine bead array kit. (b) BMDM were stimulated with 10, 100 or 1000 ng/ml WT, 430 or 435 LPS moieties. NO was determined in the supernatant. (c) Peritoneal macrophages were exposed for 6 hr to 100 ng/ml WT, 430 or 435 LPS moieties, and subjected to a chemotaxis assay using modified Boyden chambers, with 100 ng/ml CCL12 as control. Migrating cells were quantified by fluorescence. One-way analysis of variance test with Bonferroni's multiple comparison correction was applied. Significant differences are indicated by asterisks: *P<0·05, **P<0·01 and ***P<0·001. Data are representative of three independent experiments. UD = under detection limit.

It has been shown that macrophage anti-microbial activities are related to the generation of nitrogen intermediates.25 We evaluated the capacity of the different LPS moieties to induce NO production in BMDM. WT and 430 LPS induced similar levels of NO while 435 LPS induced a significantly lower level of NO (Fig. 1b).

Cell migration is induced after infection and represents an important mechanism for coping with invading pathogens.26 To test the capacity of structurally modified LPS to affect cell migration, chemotaxis of peritoneal macrophages was analysed after exposure to WT, 430 or 435 LPS moieties. We observed that both 430 and 435 LPS induced lower macrophage chemotaxis in response to the chemokine CCL-12. Compared with WT, 435 LPS showed the lowest chemotactic activity (Fig. 1c).

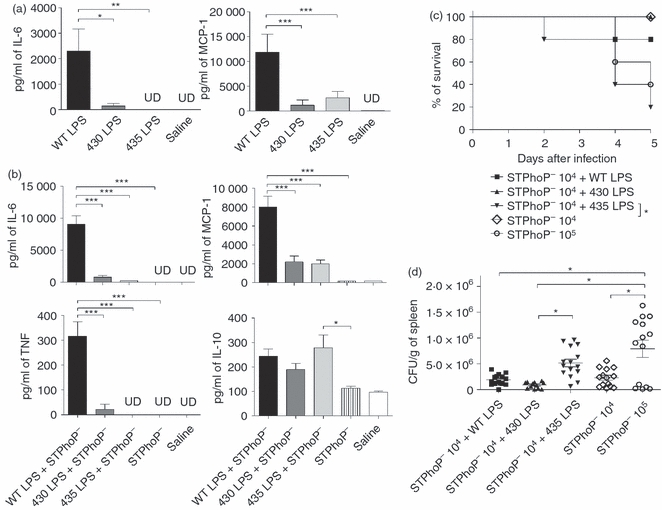

Compared with WT LPS, 430 and 435 LPS moieties induce lower in vivo cytokine production

To study the in vivo effects of structurally modified LPS on innate immune responses, we administered WT, 430 or 435 LPS moieties i.p. to BALB/c mice. After 6 hr, of stimulation we found that WT LPS induced a cytokine production profile mainly characterized by IL-6 and MCP-1 production. TNF and IL-10 were not detected. 430 and 435 LPS moieties showed a 10-fold less IL-6 and MCP-1 production compared with WT LPS (Fig. 2a). As TNF production peaks at 90 min, we evaluated the cytokine profile also at this time. 435 LPS but not 430 LPS showed less TNF, IL-6 and MCP-1 production compared with WT LPS (data not shown). Our results indicate that 430 and 435 LPS are weaker inducers of cytokine production compared with WT LPS. To evaluate whether modified LPS moieties play a role in the impairment of the inflammatory response during infection, we infected mice with the attenuated PhoP−S. typhimurium strain (which is unable to modify its LPS via the direct PhoP-regulated pathway and has severely diminished capacity for PmrA-mediated modifications).16 A sub-lethal dose of bacteria was administered alone or mixed with 5 μg of the different LPS moieties. Serum cytokine levels were measured 6 hr after infection (Fig. 2b). We found that the PhoP−S. typhimurium strain did not induce the production of any other measured cytokine. However, WT LPS co-administration induced the production of high levels of MCP-1, IL-6 and TNF (Fig. 2b). Co-administration of 430 or 435 LPS moieties resulted in more than 10-fold less IL-6 and fourfold less MCP-1 production than WT LPS co-administration. Moreover, compared with WT LPS, a 10-fold lower production of TNF was observed when 430 LPS was co-administered and 435 LPS co-administration did not induce TNF production. Finally, compared with PhoP−, only slight differences in the production of IL-10 were observed with co-administration of the WT and 430 LPS moieties, in contrast, significant difference was observed when 435 LPS was co-administered (Fig. 2b). These results indicate that structurally modified LPS present on S. typhimurium are weak inducers of inflammatory responses in vivo, not only when administered alone, but also when administered together with the bacteria.

Figure 2.

Compared with wild-type (WT), structurally modified lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induce less cytokine production in vivo and favours lethal infection by an avirulent Salmonella typhimurium strain. (a) Groups of four BALB/c mice received intraperitoneally 5 μg WT, 430 or 435 LPS moieties or (b) were infected with 1 × 104 colony-forming units (CFU) S. typhimurium PhoP− strain alone (STPhoP−) or mixed with 5 μg WT, 430 or 435 LPS moieties. Serum samples were obtained at 6 hr after LPS administration or after infection. Samples were analysed for inflammatory cytokine presence using a mouse inflammatory cytokine bead array kit. Representative data of three independent experiments are shown. One-way analysis of variance test with Bonferroni's multiple comparison correction was applied. Significant differences are indicated by asterisks: *P<0·05, **P<0·01 and ***P<0·001. UD = under detection limit. (c) Groups of 10 BALB/c mice were infected with 1 × 104 CFU S. typhimurium PhoP− strain alone (STPhoP−) or mixed with 5 μg WT, 430 or 435 LPS moieties. Survival of mice was assessed 5 days after infection. Data are representative of three independent experiments. The difference in survival rates was evaluated by the log rank test (Mantel-Cox). Significant differences are indicated by asterisks: *P<0·05. (d) Bacterial load was determined in the spleen at day 2 of infection (n = 15). Merged data of two independent experiments are shown. Differences were analysed using one-way anaysis of variance test and the Tukey multiple comparison test. Significant differences are indicated by asterisks: *P<0·05.

435 LPS but not 430 LPS moiety predisposes mice to lethal infection with an avirulent S. typhimurium strain

The findings presented above suggest that LPS structural modifications could play an important role in favouring S. typhimurium infection. To address this, BALB/c mice were infected with sub-lethal doses of PhoP−S. typhimurium strain co-administered with 5 μg of WT, 430 or 435 LPS moieties. The administration of these LPS doses alone did not show any toxic or lethal effect on the mice. Survival and bacterial numbers in tissues were evaluated for 5 days after infection (Fig. 2c). Mice that received bacteria together with WT or 430 LPS moieties were able to control infection; in contrast, mice that received bacteria and 435 LPS moiety succumbed to the infection and showed mortality and higher bacterial counts in their spleens (Fig. 2d). The effect induced by 435 LPS was comparable with the infection with a 10-fold higher bacterial dose (Fig. 2c,d), suggesting that co-administration of bacteria with 435 LPS allows bacterial replication. The 430 LPS did not increase the death rate in mice or increase the bacterial load in tissues.

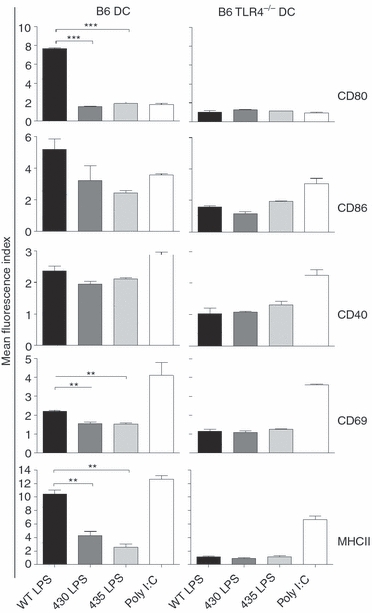

Compared with WT LPS, 430 and 435 LPS moieties induce less TLR4-dependent expression of co-stimulatory molecules on DC and less antigen-specific T-cell activation.

To evaluate the ability of structurally modified LPS moieties to activate APC, the expression of co-stimulatory molecules on DC was determined in C57BL/6 and TLR4−/− mice. Compared with WT LPS, 430 and 435 LPS moieties induced lower expression of CD80, CD69 and MHC II. A sixfold less induction of CD80 was observed when 430 and 435 LPS were administered. A fourfold less induction of MHC II was observed when 430 LPS was administered and a sevenfold when using 435 LPS compared with WT LPS. Non-significant differences among the groups were observed in the expression of CD86 and CD40. This effect was abolished in DC from TLR4−/− mice, indicating that the differences in DC activation are dependent on this receptor (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Structurally modified lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induce Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) -dependent differential activation of dendritic cells (DC). Groups of three wild-type (WT) or TLR4−/− mice were injected subcutaneously with 25 μg WT, 430 or 435 LPS moieties. Six hours later the spleen was obtained and the expression of CD80, CD86, CD69, CD40 and MHCII on CD11c+ B220– cells (DC) was measured by flow cytometry. Saline and poly I:C (a TLR4-independent stimulus) were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. Levels of co-stimulatory and activation molecules are expressed as mean fluorescence index. Mean fluorescence index is defined as the ratio between treated mice versus mice receiving saline. One-way analysis of variance test with Bonferroni's multiple comparison correction was applied. Significant differences are indicated by asterisks: **P<0·01 and ***P<0·001. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

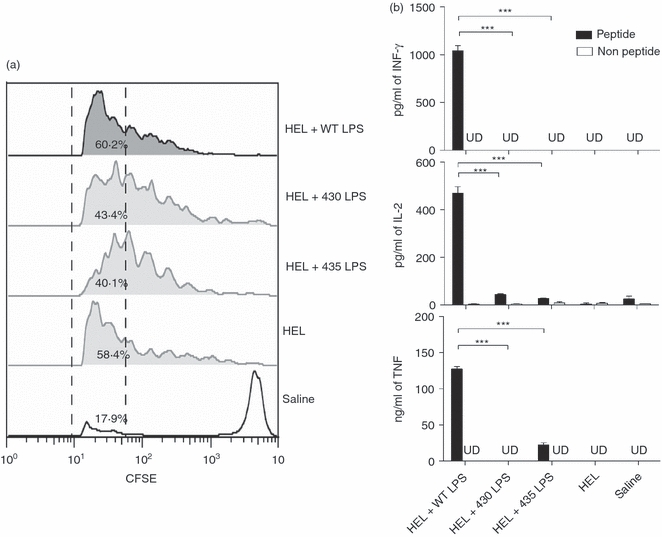

To assess whether the reduction in activation and in expression of co-stimulatory molecules on DCs induced by the 430 and 435 LPS moieties can lead to inefficient T-cell activation, HEL(46–61)-specific CD4+ T cells were adoptively transferred to congenic B10.BR WT mice. Mice were immunized with HEL alone or mixed with the different LPS moieties, and after 3 days, cytokine production and proliferation of T cells were assessed. Mice that received HEL + 430 LPS or HEL + 435 LPS showed slight reduction in the percentage of cells in the last proliferation cycles compared with WT LPS + HEL stimulation or HEL alone (Fig. 4a). Although 430 or 435 LPS induced a significant T-cell proliferation, the T-cell cytokine expression was similar to HEL alone and clearly different to the Th1 cytokine profile induced by WT LPS. Addition of 430 or 435 LPS did not affect the T-cell cytokine profile induced by HEL administration composed by low levels of IL-2 but no detectable IFN-γ, TNF, IL-4 or IL-5 (Fig. 4b) suggesting that the lower expression of co-stimulatory molecules observed on DC, translated to a non-effective CD4 T-cell activation. Proliferation 2 days after immunization was also measured, in these conditions we observed that HEL induced a very discrete proliferation, in contrast, all LPS induced HEL-specific T-cell proliferation, however, among them, 435 LPS showed the lowest induction of proliferation (data not shown). These data indicate that 430 and 435 LPS are less efficient than WT LPS to adjuvant antigen-specific T-cell responses.

Figure 4.

Compared with wild-type (WT), 430 and 435 lipopolysaccharide (LPS) moieties are less efficient at inducing antigen-specific T-cell activation. Groups of three B10BR mice were adoptively transferred with 5 × 106 carboxyfluorosuccinimidyl ester (CFSE) -labelled CD4+ T hen egg lysozyme (HEL) -specific cells, and subcutaneously immunized with 3 μg HEL alone or mixed with 5 μg of the different LPS moieties. Three days after immunization, popliteal lymph node cells were obtained and (a) proliferation was assessed by CFSE staining and flow cytometric analysis. The percentages of cells in the last proliferation cycles are indicated between the dashed lines. (b) Lymph node cells (3 × 105) were co-cultured with 1 × 105 purified splenic DCs loaded or not loaded with HEL(46–61) peptide. Five hours later, culture supernatants were harvested and the T helper type 1 (Th1)/Th2 cytokine profile was measured by cytokine bead array assay. Representative data from two independent experiments are shown. UD = under detection limit. One-way analysis of variance test with Bonferroni's multiple comparison correction was applied. Significant differences are indicated by asterisks: ***P<0·001.

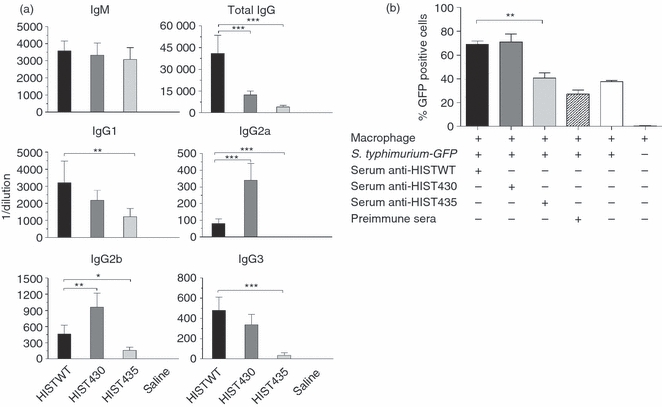

S. typhimurium expressing structural LPS modifications subvert specific antibody responses

Because S. typhimurium structurally modified LPS were able to induce lower innate immune responses and antigen-specific T-cell activation, which are important collaborators in the induction of efficient antibody responses, we investigated the effect of these LPS modifications on the anti-Salmonella antibody response. The S. typhimurium expressing structurally modified LPS moieties were heat-inactivated and injected i.p. into BALB/c mice. Bacteria were heat-inactivated (HI) because the strains have different capacities to replicate within the host, so HI S. typhimurium (HIST) were used to produce comparable amounts of antigenic challenge. No differences in the ELISA titre of specific IgM antibodies were observed after immunization with WT and mutant S. typhimurium strains (Fig. 5a). In contrast, total IgG (tIgG) anti-S. typhimurium antibody titres induced by HIST430 and HIST435 were markedly lower when compared with the titres induced by HISTWT. HIST430 induced lower titres of specific IgG1 and IgG3 antibody than HISTWT, whereas the titres of IgG2a and IgG2b antibody induced by HIST430 were higher than the titres induced by the HISTWT (Fig. 5a). HIST435 induced the lowest titres of specific IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b and IgG3 antibodies. Sera was also tested by ELISA in plates coated with HIST430 or HIST435, similar results were observed indicating that differences in antibody titres reported were not the result of a different set of antigens expressd by HISTWT bacteria (data not shown). In addition, the opsonophagocytic capacity of these antibodies was tested. Sera from mice immunized with HISTWT and HIST430 mediated a similar bacterial uptake by these macrophages, whereas the serum from mice immunized with HIST435 was less effective (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5.

Compared with wild-type (WT) Salmonella typhimurium, 430 and 435 S. typhimurium induce lower specific-secondary IgG antibody titres and serum opsonophagocytic activity. (a) Groups of five BALB/c mice were immunized intraperitoneally with 5 × 105 colony-forming units of heat-inactivated S. typhimurium strains WT, 430 or 435 (HISTWT, HIST430 or HIST435). Mice were boosted on day 15 with the same number of bacteria. Specific anti-S. typhimurium antibody titres were determined using ELISA in mouse sera taken 30 days after the first immunization and the results are presented as the mean of individual measurements ± SD. (b) S. typhimurium GFP bacteria were opsonized with the sera taken from mice at day 30 after immunization and a phagocytosis assay was performed with J774A.1 macrophages. The percentage of bacterial internalization was measured by flow cytometry. One-way analysis of variance test with Bonferroni's multiple comparison correction was applied. Significant differences are indicated by asterisks: *P<0·05, **P<0·01 and ***P<0·001. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

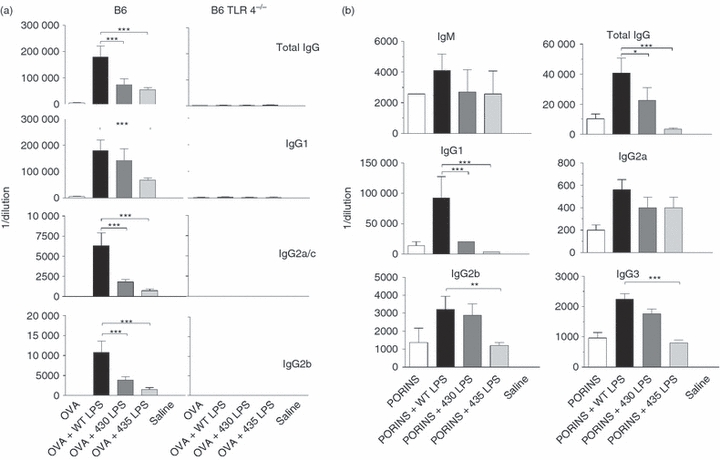

Structurally modified S. typhimurium LPS exhibit low TLR4-dependent adjuvant effect on the antigen-specific antibody responses

To test whether the lower induction of specific antibody titres observed after immunization with S. typhimurium expressing the 430 or the 435 LPS moieties was caused by LPS and not by other antigens or pathogen-associated molecular patterns differentially expressed by STWT, ST430 or ST435 strains, the adjuvanticity of purified LPS from these strains was analysed. WT, 430 or 435 LPS moieties were mixed with OVA, and these preparations were used to immunize C57BL/6 mice on days 0 and 15. On day 21, anti-OVA antibody titres present in the sera were measured by ELISA (Fig. 6). Control mice immunized only with OVA demonstrated low titres of total IgG and IgG1 antibodies. WT LPS mixed with OVA induced the highest OVA-specific tIgG, IgG1, IgG2a/c and IgG2b antibody titres (Fig. 6a). This adjuvant effect was reduced for all these classes of OVA-specific antibodies when the 430 LPS moiety was used (Fig. 6a). OVA + 435 LPS moiety induced the lowest OVA-specific IgG antibody titres in all cases (Fig. 6a). However, all types of LPS induced the production of IgG2a/c and IgG2b, which were not induced by immunization with OVA alone. To test whether this phenomenon is dependent on TLR4, TLR4−/− mice were immunized using the protocol described above. For all groups, only total IgG and IgG1 antibody titres were barely detected, indicating that the adjuvant effect of LPS moieties is mediated by TLR4 (Fig. 6a).

Figure 6.

Compared with wild-type lipopolysaccharide (WT LPS), structurally modified LPS induces lower Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) -dependent adjuvant effect on the specific antibody responses. (a) Groups of six C57BL/6 or TLR4−/− mice were immunized with ovalbumin (OVA) alone or in combination with the different LPS moieties as adjuvant at day 0 and boosted on day 15. (b) Groups of six BALB/c mice were immunized with Salmonella typhi porins alone or in combination with the different LPS moieties as adjuvant at day 0 and boosted on day 15. OVA-specific or porin-specific IgM, total IgG, IgG1, IgG2a/c, IgG2b and IgG3 titres were evaluated by ELISA on day 30 after first immunization. One-way analysis of variance test with Bonferroni's multiple comparison correction was applied. Significant differences are indicated by asterisks: *P<0·05, **P<0·01 and ***P<0·001. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

We also tested the adjuvant effect of structurally modified LPS on the antibody responses against an experimental vaccine composed by S. typhi porins.18 Porins + WT LPS induced the highest titres of porin-specific IgM, tIgG, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b and IgG3 antibodies during the secondary response (Fig. 6b). Porins + 430 LPS induced a lower adjuvant effect on the porin-specific IgG1 compared with that induced by WT LPS (Fig. 6b). Interestingly, there was no demonstrable adjuvant effect of the 435 LPS moiety mixed with porins. (Fig. 6b). Taken together, these results indicate that, compared with WT LPS, structurally modified LPS moieties are less efficient adjuvants for the induction of the B-cell-specific responses to non-microbial and to Salmonella antigens.

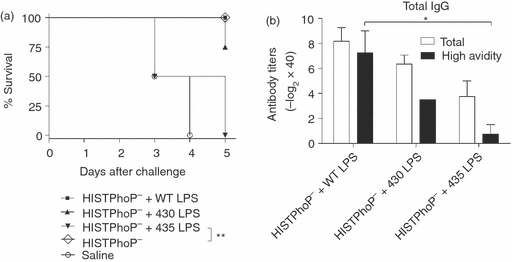

Structurally modified LPS subvert generation of immunity by an experimental anti-S. typhimurium live attenuated vaccine

Heat-inactivated S. typhimurium carrying modified LPS generated an impaired specific antibody response, but the effect of these LPS on the generation of immunity to virulent S. typhimurium was unknown. To address this question, mice were immunized with an S. typhimurium PhoP− strain co-administered with WT, 430 or 435 LPS moieties. This strain has been used as experimental vaccine candidate for salmonellosis16 and expresses homogeneous hexa-acylated lipid A, which is useful to evaluate the contribution of the different LPS to the generation of immunity to virulent S. typhimurium. Thirty days after immunization, mice were challenged with 5 × 106 CFU of S. typhimurium 14028s virulent strain. We found that all mice that received HISTPhoP− + 435 LPS died within 5 days after challenge (Fig. 7a). In contrast, 75% of the mice immunized with HISTPhoP− + 430 LPS survived. Co-administration of WT LPS induced protection in all mice after challenge. We found that the tIgG antibody response from mice that received HISTPhoP− + 435 LPS was composed mainly of low-affinity antibodies (Fig. 7b). Around 50% of the total IgG antibody response induced by HISTPhoP− + 430 LPS was of high affinity, whereas mice that received HISTPhoP− + WT LPS generated mainly high-avidity antibodies. The reduction of protection induced by PhoP− + 430 or 435 LPS correlated with the lower avidity of the antibodies generated. These results strongly suggest that structurally modified LPS subvert the generation of protective B-cell responses to S. typhimurium.

Figure 7.

Structurally modified but not wild-type lipopolysaccharide (WT LPS), subvert immunity generation induced by an anti-Salmonella typhimurium experimental live attenuated vaccine. (a) Groups of four BALB/c mice were immunized intraperitoneally at day 0 and 15 with 5 × 105 colony-forming units (CFU) of heat-inactivated PhoP−S. typhimurium vaccine strain (HISTPhoP−), co-administered with 5 μg WT or 430 or 435 LPS moieties. Thirty days after immunization, mice were challenged with 5 × 106 CFU 14028s S. typhimurium strain. Per cent survival was assessed over 5 days after challenge. The difference in survival rates was evaluated by the log rank test (Mantel–Cox). Significant differences are indicated by asterisks: **P<0·01. (b) Two days before the challenge, blood samples were collected and the avidity of anti-S. typhimurium total IgG antibodies was determined by a modified ELISA method. One-way analysis of variance test with Bonferroni's multiple comparison correction was applied. Significant differences are indicated by asterisks: *P<0·05. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

Discussion

Salmonella typhimurium is an extremely successful microorganism able to infect a wide range of hosts and cause different pathologies.1 Mortality is high in non-industrialized countries, particularly in patients suffering from HIV infection.2 It is therefore important to uncover the mechanisms used by Salmonella to avoid or subvert host defences. Our study analysed three different LPS moieties, products of the PhoPQ-PmrAB TCS (Table 1), which are expressed by S. typhimurium in response to environmental signals. Our results show that structurally modified LPS decrease important mediators of the innate immune response both in vivo and in vitro (Figs 1 and 2). This could be explained by a deficient TLR4 signalling induced by modified LPS, because the crystal structure of the TLR4–MD-2–LPS complex shows that the 1 and 4′ phosphate groups of LPS interact with a cluster of positively charged residues from TLR4 and MD-2. Therefore, deletion of these phosphate groups should have a profound effect on the receptor–ligand interaction.5 Similarly, the l-Ara4N groups that are attached to the phosphate groups of lipid A in the 435 LPS moiety could favour TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing IFN-β (TRIF)-mediated signalling, so reducing the secretion of classical inflammatory cytokines.27 Impairing or delaying signalling through TLR4 can decrease innate immune activation, and may allow bacterial replication to lethal levels in mice.28

A low production of inflammatory mediators in the early stages of infection could open a window for the bacteria to replicate until they reach levels that cannot be controlled by the immune system. This could explain why co-administration of the 435 LPS moiety with an attenuated strain accelerated and increased the rate of death compared with mice that received bacteria with WT or 430 LPS moieties (Fig. 2c,d). The lack of mortality in the 430 LPS group suggests that some LPS structural changes may be produced after successful infection to reduce bacterial virulence and avoid the death of the host, thereby maintaining the ecological niche. Structural modifications of LPS are used by Salmonella to subvert early innate responses and are important to facilitate in vivo bacterial infection.

Salmonella infection can induce the selective culling of antigen-specific CD4 T cells in a mechanism dependent on Salmonella pathogenicity islands 1 and 2 (SPI-1 or -229). PhoP/Q is an important regulator of SPI-1 expression.30 The observation that structurally modified LPS are weak inducers of co-stimulatory molecules on DCs (Fig. 3) and drive an inefficient antigen-specific CD4 T-cell response (Fig. 4), indicates that, in contrast to the efficient activation of T-cell and B-cell responses reported for other pathogen-associated molecular patterns used as adjuvants;31,32 these modified LPS hamper the translation of the innate responses into adaptive immune responses. Hence, modified LPS could also impair the activation of Salmonella-specific T cells, rendering mice infected or vaccinated with PhoP− + 435 LPS unable to generate a protective response (Figs 4a and 7a).

Induction of an antibody response against S. typhimurium is an important mechanism to control the dissemination of the bacteria in the host and has been proposed as the principal mediator of protection after vaccination.2,18,33 Deficient T-cell activation could lead to reduced T-cell-dependent antibody responses, which could in turn explain the depressed anti-Salmonella antibody titres (Fig. 5a) that result in reduced capacity to mediate bacterial uptake by macrophages (Fig. 5b) when mice are immunized with heat-inactivated S. typhimurium expressing modified LPS. In addition, it has been reported that S. typhimurium disrupts lymph node architecture by TLR4-mediated suppression of homeostatic chemokines, suggesting that LPS is an important factor in the subversion of antibody responses by targeting the central organ responsible for the development of the humoral immune response.34 Diminished opsonophagocytic capacity of the antibodies generated by HIST435 (Fig. 5b) could also be a result of the reduction in antibody titres and the low affinity of these antibodies. Paradoxically, sera from mice immunized with HIST430 showed the same opsonophagocytic capacity as the sera from mice immunized with HISTWT, despite inducing lower titres of specific total IgG. A possible explanation is that the major Fc receptor mediating Salmonella phagocytosis is FcγRI, which binds monomeric IgG2a.35 HIST430 induced the highest titre of IgG2a, which could compensate for lower tIgG titres induced.

The LPS TLR4-dependent adjuvanticity for antibody responses to OVA and porins was decreased on modified LPS (Fig. 6). In addition to reduced T-cell help, a direct regulatory effect of LPS on B-cell TLR4 signalling could explain the decrease in specific antibody titres. We previously reported that TLR2/4 signals in B cells influence antibody responses against these Salmonella antigens.4 Immunization with 435 LPS mixed with porins induced lower antibody titres than porins alone, hence 435 LPS was not only failing as an adjuvant but actively inhibited the anti-porin antibody response (Fig. 6b). These data could be relevant to understanding the immunomodulatory effects exerted by different molecular structures such as monophosphoryl lipid A that have been used as adjuvants in some vaccine preparations.27 This information could be useful for adjuvant design and vaccine development.

The LPS-mediated induction of decreased T-cell and B-cell responses could also explain the correlation between the increased susceptibility of mice to S. typhimurium challenge and the low affinity of anti-Salmonella antibody response induced by structurally modified LPS (Fig. 7b). As affinity maturation of antibody responses is one of the mechanisms of the antibody memory response,36 the reduction in high avidity anti-Salmonella antibody titres (Fig. 7b) could reflect an impact of LPS on the formation of the B-cell memory compartment. Blocking the formation of this compartment could explain the reduction of protection induced by the HISTPhoP− vaccination (Fig. 7a).

In conclusion, S. typhimurium exploits lipid A structural modifications as a strategy to subvert innate and adaptive immune activation hampering the establishment of protective immunity. These general effects on the immune system could shape Salmonella's niche by permitting bacterial infection and avoiding or reducing the generation of immunity that could lead to host susceptibility to a chronic infection, bacterial reinfection or to development of a carrier state. All these factors are important contributors to the great success of Salmonella in infecting its host.

Acknowledgments

We want to acknowledge to Ms María Ramírez-Aguilar for the technical assistance in Salmonella infection experiments. This work was funded by the Fondo para el Fomento de la Investigación (FOFOI) of the Coordinación de Investigación en Salud del Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (IMSS), grants FP 2005/I/039 and FIS/IMSS/PROT/C2007/049, and by grants 33137-M, 45261-M and SALUD-2007-C01-69779 from the Mexican Council for Science and Technology (CONACyT), awarded to C.L-M. R.P.-P. was supported by grant 43911-M from CONACyT and the General Direction of Academic Personnel Affairs National Autonomous University of Mexico (DGAPA-UNAM) Support Program for Research and Technology Innovation Projects (PAPIIT) grants IN214302-2 and IN224907. C.G.C., C.I.P.S. and M.A.M.E. acknowledge the fellowship from CONACyT and IMSS. Eduardo García Zepeda was supported by CONACyT grant 52498, and John S. Gunn by grant AI043521 from the National Institutes of Health, USA. CLM acknowledge the support for travelling to meetings received from ‘Red de desarrollo de fármacos y métodos de diagnóstico (FARMED)’ CONACyT.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- HIST430

heat-inactivated Salmonella typhimurium 430

- HIST435

heat-inactivated Salmonella typhimurium 435

- HISTWT

heat-inactivated Salmonella typhimurium wild-type

- ST430

Salmonella typhimurium 430

- ST435

Salmonella typhimurium 435, STPhoP−, Salmonella typhimurium PhoP−

- STWT

Salmonella typhimurium wild-type

- WT LPS

wild-type lipopolysaccharide

- 430 LPS

430 lipopolysaccharide

- 435 LPS

435 lipopolysaccharide

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.de JB, Ekdahl K. The comparative burden of salmonellosis in the European Union member states, associated and candidate countries. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacLennan CA, Gilchrist JJ, Gordon MA, et al. Dysregulated humoral immunity to nontyphoidal Salmonella in HIV-infected African adults. Science. 2010;328:508–12. doi: 10.1126/science.1180346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:987–95. doi: 10.1038/ni1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cervantes-Barragan L, Gil-Cruz C, Pastelin-Palacios R, et al. TLR2 and TLR4 signaling shapes specific antibody responses to Salmonella typhi antigens. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:126–35. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park BS, Song DH, Kim HM, Choi BS, Lee H, Lee JO. The structural basis of lipopolysaccharide recognition by the TLR4-MD-2 complex. Nature. 2009;458:1191–5. doi: 10.1038/nature07830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galanos C, Lehmann V, Luderitz O, et al. Endotoxic properties of chemically synthesized lipid A part structures. Comparison of synthetic lipid A precursor and synthetic analogues with biosynthetic lipid A precursor and free lipid A. Eur J Biochem. 1984;140:221–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb08090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kido N, Ohta M, Ito H, et al. Potent adjuvant action of lipopolysaccharides possessing the O-specific polysaccharide moieties consisting of mannans in antibody response against protein antigen. Cell Immunol. 1985;91:52–9. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(85)90031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hajjar AM, Ernst RK, Tsai JH, Wilson CB, Miller SI. Human Toll-like receptor 4 recognizes host-specific LPS modifications. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:354–9. doi: 10.1038/ni777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pulendran B, Kumar P, Cutler CW, Mohamadzadeh M, van DT, Banchereau J. Lipopolysaccharides from distinct pathogens induce different classes of immune responses in vivo. J Immunol. 2001;167:5067–76. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.5067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rietschel ET, Brade H, Holst O, et al. Bacterial endotoxin: chemical constitution, biological recognition, host response, and immunological detoxification. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;216:39–81. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-80186-0_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller SI, Kukral AM, Mekalanos JJ. A two-component regulatory system (phoP phoQ) controls Salmonella typhimurium virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:5054–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.13.5054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo L, Lim KB, Gunn JS, et al. Regulation of lipid A modifications by Salmonella typhimurium virulence genes phoP-phoQ. Science. 1997;276:250–3. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5310.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gunn JS, Miller SI. PhoP-PhoQ activates transcription of pmrAB, encoding a two-component regulatory system involved in Salmonella typhimurium antimicrobial peptide resistance. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6857–64. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6857-6864.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bergman MA, Cummings LA, Barrett SL, et al. CD4+ T cells and toll-like receptors recognize Salmonella antigens expressed in bacterial surface organelles. Infect Immun. 2005;73:1350–6. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1350-1356.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gunn JS, Lim KB, Krueger J, et al. PmrA-PmrB-regulated genes necessary for 4-aminoarabinose lipid A modification and polymyxin resistance. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:1171–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galan JE, Curtiss R., III Virulence and vaccine potential of phoP mutants of Salmonella typhimurium. Microb Pathog. 1989;6:433–43. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(89)90085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McSorley SJ, Ehst BD, Yu Y, Gewirtz AT. Bacterial flagellin is an effective adjuvant for CD4+ T cells in vivo. J Immunol. 2002;169:3914–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salazar-Gonzalez RM, Maldonado-Bernal C, Ramirez-Cruz NE, et al. Induction of cellular immune response and anti-Salmonella enterica serovar typhi bactericidal antibodies in healthy volunteers by immunization with a vaccine candidate against typhoid fever. Immunol Lett. 2004;93:115–22. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swanson JA. Phorbol esters stimulate macropinocytosis and solutes flow through macrophages. J Cell Sci. 1989;94:135–42. doi: 10.1242/jcs.94.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green SJ, Aniagolu J, Raney JJ. Oxidative metabolism of murine macrophages. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2001 doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im1405s12. Chapter 14:Unit 14.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcia-Zepeda EA, Combadiere C, Rothenberg ME, et al. Human monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-4 is a novel CC chemokine with activities on monocytes, eosinophils, and basophils induced in allergic and nonallergic inflammation that signals through the CC chemokine receptors (CCR)-2 and -3. J Immunol. 1996;157:5613–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Secundino I, Lopez-Macias C, Cervantes-Barragan L, et al. Salmonella porins induce a sustained, lifelong specific bactericidal antibody memory response. Immunology. 2006;117:59–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delgado MF, Coviello S, Monsalvo AC, et al. Lack of antibody affinity maturation due to poor Toll-like receptor stimulation leads to enhanced respiratory syncytial virus disease. Nat Med. 2009;15:34–41. doi: 10.1038/nm.1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tam MA, Rydstrom A, Sundquist M, Wick MJ. Early cellular responses to Salmonella infection: dendritic cells, monocytes, and more. Immunol Rev. 2008;225:140–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vazquez-Torres A, Jones-Carson J, Mastroeni P, Ischiropoulos H, Fang FC. Antimicrobial actions of the NADPH phagocyte oxidase and inducible nitric oxide synthase in experimental salmonellosis. I. Effects on microbial killing by activated peritoneal macrophages in vitro. J Exp Med. 2000;192:227–36. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao C, Wood MW, Galyov EE, et al. Salmonella typhimurium infection triggers dendritic cells and macrophages to adopt distinct migration patterns in vivo. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:2939–50. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mata-Haro V, Cekic C, Martin M, Chilton PM, Casella CR, Mitchell TC. The vaccine adjuvant monophosphoryl lipid A as a TRIF-biased agonist of TLR4. Science. 2007;316:1628–32. doi: 10.1126/science.1138963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Montminy SW, Khan N, McGrath S, et al. Virulence factors of Yersinia pestis are overcome by a strong lipopolysaccharide response. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1066–73. doi: 10.1038/ni1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Srinivasan A, Nanton M, Griffin A, McSorley SJ. Culling of activated CD4 T cells during typhoid is driven by Salmonella virulence genes. J Immunol. 2009;182:7838–45. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Main-Hester KL, Colpitts KM, Thomas GA, Fang FC, Libby SJ. Coordinate regulation of Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI1) and SPI4 in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Infect Immun. 2008;76:1024–35. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01224-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Acosta-Ramirez E, Perez-Flores R, Majeau N, et al. Translating innate response into long-lasting antibody response by the intrinsic antigen-adjuvant properties of papaya mosaic virus. Immunology. 2008;124:186–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02753.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pulendran B, Ahmed R. Translating innate immunity into immunological memory: implications for vaccine development. Cell. 2006;124:849–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gil-Cruz C, Bobat S, Marshall JL, et al. The porin OmpD from non-typhoidal Salmonella is a key target for a protective B1b cell antibody response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:9803–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812431106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.St John AL, Abraham SN. Salmonella disrupts lymph node architecture by TLR4-mediated suppression of homeostatic chemokines. Nat Med. 2009;15:1259–65. doi: 10.1038/nm.2036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uppington H, Menager N, Boross P, et al. Effect of immune serum and role of individual Fcgamma receptors on the intracellular distribution and survival of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium in murine macrophages. Immunology. 2006;119:147–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02416.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shivarov V, Shinkura R, Doi T, et al. Molecular mechanism for generation of antibody memory. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009;364:569–75. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]