SUMMARY

Macroautophagy mediates the degradation of long-lived proteins and organelles via the de novo formation of double-membrane autophagosomes that sequester cytoplasm and deliver it to the vacuole/lysosome; however, relatively little is known about autophagosome biogenesis. Atg8, a phosphatidylethanolamine-conjugated protein, was previously proposed to function in autophagosome membrane expansion, based on the observation that it mediates liposome tethering and hemifusion in vitro. We show here that with physiological concentrations of phosphatidylethanolamine, Atg8 does not act as a fusogen. Rather, we provide evidence for the involvement of exocytic Q/t-SNAREs in autophagosome formation, acting in the recruitment of key autophagy components to the site of autophagosome formation, and in regulating the organization of Atg9 into tubulovesicular clusters. Additionally, we found that the endosomal Q/t-SNARE Tlg2 and the R/v-SNAREs Sec22 and Ykt6 interact with Sso1-Sec9, and are required for normal Atg9 transport. Thus, multiple SNARE-mediated fusion events are likely to be involved in autophagosome biogenesis.

Keywords: Atg9, fusion, lysosome, membrane biogenesis, protein targeting, secretory pathway, stress, tubulovesicular clusters, vacuole, yeast

INTRODUCTION

Macroautophagy, hereafter autophagy, is an intracellular degradation pathway conserved among all eukaryotes. In this pathway, membranous compartments, phagophores, initiate the sequestration of cytoplasm; the phagophores expand and mature into double-membrane vesicles, termed autophagosomes. The outer membrane of completed autophagosomes fuses with the vacuole, and the inner membrane vesicles and cargo are released into the vacuolar lumen for degradation. Although there are various models to describe the vesicle formation process, most involve membrane fusion for phagophore expansion, yet our knowledge of the membrane fusion mechanism during autophagosome formation is limited.

Atg8/LC3, a phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) conjugated, ubiquitin-like protein that determines autophagosome size (Xie et al., 2008), is proposed to mediate membrane tethering and hemifusion, and thereby facilitate the expansion of the phagophore (Nakatogawa et al., 2007). The experiments demonstrating hemifusion, however, were performed with non-physiological concentrations of this lipid. We reexamined the role of PE-conjugated Atg8/LC3 in hemifusion, and found that this conjugate was not sufficient to stimulate membrane hemifusion in vitro in the presence of physiological PE concentrations.

Atg9 is the only transmembrane protein in yeast that is essential for autophagosome formation (Reggiori et al., 2004a). This protein shuttles between several peripheral membrane sites in the cytoplasm and the phagophore assembly site (PAS), the presumed site of autophagosome formation (Mari et al., 2010; Reggiori et al., 2005); and recent experimental evidence suggests that translocation of Atg9-containing tubules and vesicles to the perivacuolar region leads to phagophore formation (Mari et al., 2010). We found that the exocytic Q/t-SNAREs Sso1/2 and Sec9 are required for organizing Atg9 into tubulovesicular clusters, and are therefore required for autophagosome formation. These SNAREs may function together with the endosomal Q/t-SNARE, Tlg2, and the R/v-SNAREs Sec22 and Ykt6. Thus, autophagosome membrane expansion/closure appears to proceed via a SNARE-dependent mechanism.

RESULTS

Atg8/LC3–PE Is Not Sufficient to Drive Membrane Hemifusion in Physiological Conditions

Previously, Atg8–PE was shown to drive the hemifusion of membranes, a function implicated in the expansion of the phagophore (Nakatogawa et al., 2007). Those data, however, relied on in vitro fusion reactions using liposomes containing 55% phosphatidylethanolamine. PE plays a critical role in membrane dynamics; it is a cone-shaped “non-bilayer preferring” lipid with a strongly negative spontaneous curvature that facilitates hemifusion (Chernomordik and Kozlov, 2003). As such, liposomes having 50% or more PE are inherently unstable and prone to fusion by a variety of factors not associated with membrane dynamics or vesicle trafficking (Brugger et al., 2000). Therefore, we sought to examine the putative role of Atg8–PE in membrane hemifusion using liposomes with physiological concentrations of PE.

The concentration of PE at the phagophore is not known; however, the concentration in organelles implicated as possible sources of the autophagosome membrane (Hailey et al., 2010; Lynch-Day et al., 2010; Ravikumar et al., 2010; Yen et al., 2010) ranges from 15-20% at the yeast ER and Golgi, to as much as 25% at the plasma membrane and mitochondria (van Meer et al., 2008). In order to establish lipidation conditions at these PE surface densities, we expressed and purified Atg8G116 (hereafter Atg8ΔR), Atg7, and Atg3 and incubated all three with liposomes comprised of varying amounts of PE. When ATP was included to drive the reaction, Atg8ΔR was efficiently lipidated in a PE-concentration-dependent manner (Figure 1A).

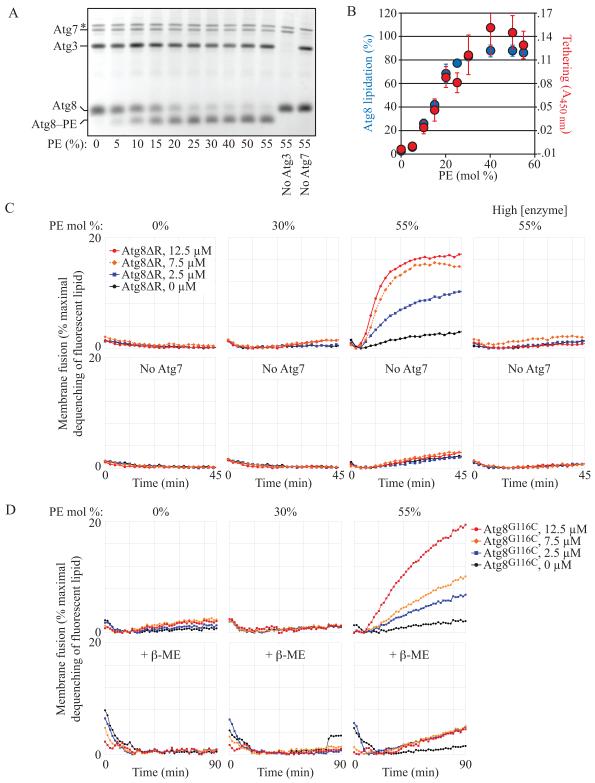

Fig. 1. Physiological Levels of Atg8–PE Are not Sufficient to Drive Membrane Hemifusion.

(A) Atg8ΔR conjugation reactions (1 μM Atg7, 1 μM Atg3, 3 μM Atg8ΔR, 1 mM ATP, 30°C for 90 min) were run with liposomes (2.4 mM lipid) comprised of varying PE surface densities (indicated) as described in the Supplement.

(B) Tethering is PE concentration dependent and closely parallels lipidation. Tethering (red) is measured as the absorbance at 450 nm of aggregating liposomes (as in Figure S1A; n = 7). Lipidation (blue) is the fraction of total Atg8 in lipidated form determined by densitometry of gels as in (A) (n = 5).

(C) Lipid-mixing assays. To follow fusion, donor liposomes (carrying small amounts of NBD and rhodamine-conjugated lipids) were mixed 1:4 with acceptor liposomes (carrying no fluorophore-associated lipids). Fusion results in dilution of the fluorophores and a decrease in rhodamine-dependent quenching of NBD. The increase in NBD fluorescence is plotted as a percentage of the total NBD fluorescence achieved after detergent solubilization of the liposomes. Atg8 coupling reactions are run as in (A) but with 0.5 μM Atg7, 0.5 μM Atg3, 1 mM total lipid and the indicated concentrations of Atg8ΔR. Lower panels are negative controls missing Atg7. The liposomes have the indicated amounts of PE. Panels labeled “high [enzyme]” were run with 7.4 μM Atg7 and 5.6 μM Atg3.

(D) Fusion remains highly PE-concentration dependent even when Atg8 lipidation is independent of Atg7/Atg3 activity. Atg8 with a C-terminal cysteine (Atg8G116C) was conjugated to maleimide-PE as described in the Supplement, so that conjugation was independent of PE concentration. Fusion reactions were initiated by the addition of varying concentrations of Atg8G116C as indicated. Lower panels: the maleimide reaction was blocked with 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol. See also Figure S1.

As in the Nakatogawa et al. paper, Atg8–PE could mediate tethering of liposomes. For example, reactions run with 55 mole % PE liposomes produced robust light scattering, consistent with liposome aggregation, while negative controls (-ATP, -Atg3, -Atg8) did not (Figure S1A). Reduction of the PE mole % had very little impact on this aggregation all the way down to 30%. In fact, the ability to cluster liposomes is well correlated with the capacity for lipidation, and both readouts were close to maximal at physiologically-relevant PE concentrations (25-30%; Figure 1B). Thus, tethering requires lipidated Atg8, but is not dependent upon unusually high PE surface densities.

Using a fluorescence dequenching assay, we tested whether these aggregated liposomes had fused. Atg8–PE mediated fusion in a protein (Atg8ΔR) concentration-dependent manner when liposomes contained 55% PE (Figure 1C). Negative controls—reactions lacking Atg7—also exhibited a modest level of membrane fusion independent of Atg8ΔR protein concentration, and illustrated the inherent fusogenicity of liposomes with high PE. As previously noted (Nakatogawa et al., 2007), high concentrations of Atg7 and Atg3 inhibited fusion even as lipidation continued, confirming that we were measuring the same phenomenon previously described. When liposomes containing physiological levels of PE (30%) were tested for fusion, however, only a negligible increase in NBD fluorescence was recorded, compared to negative controls (Figure 1C) although Atg8ΔR was conjugated to PE with efficiencies similar to those obtained using liposomes containing 55% PE (Figure 1A, 1B). Indeed, the rate of fusion of the “negative control” 55% PE liposomes (measurements in the absence of Atg7) was always higher than any experimental condition utilizing lower surface densities of PE regardless of coupling or Atg8ΔR levels (Figure S1B).

The high concentration of PE (55%) used in the initial report (Nakatogawa et al., 2007) was perhaps necessitated in part because the efficiency with which Atg8 couples to liposomes depends on the surface density of PE (Figure 1A, 1B). As a result, in this system it is very difficult to separate the contribution of PE to membrane fusion from the critical role of PE in coupling the putative fusogen. Furthermore, high concentrations of Atg7and Atg3 tend to inhibit fusion (Figure 1C; (Nakatogawa et al., 2007). All told, factors that maximize conjugation (high concentrations of substrate lipid, and coupling enzymes) are each confounding factors in interpreting the fusogenicity of Atg8. Thus, we designed a novel lipidation strategy that is independent of PE surface densities and that does not require Atg7, Atg3 or ATP (Figure S1C). We engineered Atg8 with a C-terminal cysteine that can be covalently bonded to a phospholipid carrying a maleimide reactive site on its headgroup. In this way, the total number of membrane reactive sites is a function of the maleimide density, and the liposome PE surface density can be varied independently.

Maleimide-coupled Atg8 also promoted lipid mixing on liposomes with a composition similar to that shown previously (Nakatogawa et al., 2007); i.e., 55% PE, Figure 1D). This suggests that Atg3 and Atg7 are not necessary to drive fusion, nor is a particular Atg8 conformation that might be brought on by the physiologically relevant coupling machinery. When the reaction was quenched, fusion was much lower and independent of protein concentration (Figure 1D), analogous to the “no Atg7” controls (Figure 1C). Elimination of PE or a reduction to 30% PE eliminated the fusogenic potential of this protein, despite the fact that coupling of Atg8 to maleimide was efficient across all liposome compositions. Thus, we can conclude that fusion mediated by Atg8 is only possible on membranes carrying a very high surface density of the cone-shaped lipid, PE.

Similar results were obtained when we examined the mammalian Atg8 homologue LC3. Using the maleimide-coupling strategy, only LC3-conjugated liposomes containing 55% PE were able to drive hemifusion (Figure S1D, S1E), even though the level of chemically-conjugated LC3–malPE was essentially identical across all PE concentrations tested. Taken together, liposomes with physiological PE concentrations were not able to undergo Atg8–PE or LC3–PE-dependent hemifusion.

SNARE Proteins Are Required for Autophagy

Our data indicated that Atg8/LC3 was not a self-sufficient fusogen able to direct phagophore expansion; accordingly, we were interested in identifying another component(s) that might act in this capacity. We recently reported that two proteins required for exocytosis, Sec2 and Sec4, are essential for autophagy (Geng et al., 2010). The docking and fusion of post-Golgi secretory vesicles at the cell surface is brought about by the Q/t-SNAREs Sso1/2 and Sec9, and the R/v-SNAREs Snc1/2 (Aalto et al., 1993; Brennwald et al., 1994; Protopopov et al., 1993). Given the essential role of Sec2 and Sec4 in autophagy, we investigated whether Sso1/2 and Sec9 are also required for this pathway.

We began our analysis with the GFP-Atg8 processing assay, in which this fluorescent autophagy marker is degraded in the vacuole to yield free GFP. In wild-type cells, at both permissive (PT, 24°C) and nonpermissive (NPT, 34°C) temperatures, there was no detectable free GFP in rich conditions, but a clear GFP band after starvation (Figure 2A). At the PT in nitrogen-starvation medium, the cleavage of GFP-Atg8 in sso1Δ/2ts or sec9-4 cells was similar to that in wild-type cells; however, when these cells were starved at the NPT, there was no detectable free GFP, suggesting a severe defect in autophagy (Figure 2A). When we shifted the sso1Δ/2ts or sec9-4 mutants back to PT, free GFP bands were observed in the mutants (Figure 2A; recovery, R), demonstrating that they had not lost their viability and that the block of autophagy was reversible. The expression of SSO1 or SEC9 genes from CEN plasmids restored the autophagy activity at the NPT in the sso1Δ/2ts and sec9-4 mutants, respectively (Figure S2A).

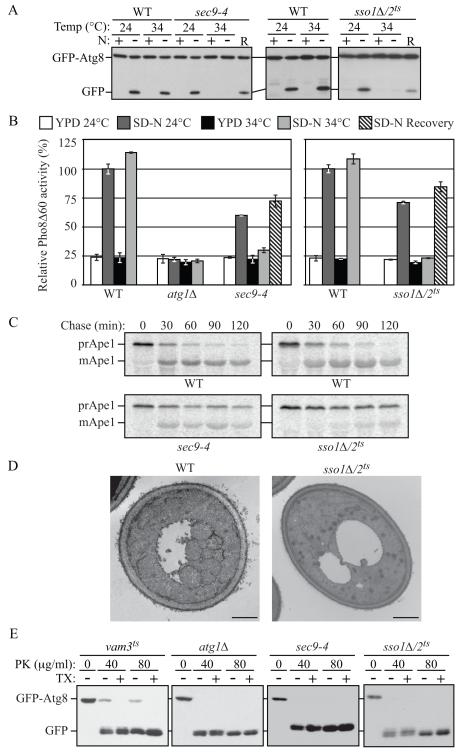

Fig. 2. Both Autophagy and the Cvt Pathway Are Defective in sec9-4 and sso1Δ/2ts Mutants.

(A) The sec9-4 and sso1Δ/2ts (H603) strains and the corresponding wild type (BY4742 and W303) were analyzed with the GFP-Atg8 processing assay at the indicated temperature by nitrogen starvation for 2 h. R, recovery; cells were returned to 24°C after the 34°C incubation for an additional 2 h.

(B) The sec9-4 (JGY236), and sso1Δ/2ts (JGY247) strains and the corresponding wild-type (YTS158 and ZFY202) cells were analyzed for Pho8Δ60 activity before and after starvation for 2 h. The atg1Δ (TYY127) strain was used as a negative control. Error bar, SD from three independent experiments.

(C) The strains from (A) were examined by pulse-chase at NPT and immunoprecipitated with anti-Ape1 antiserum.

(D) Wild-type (pep4Δ vps4Δ; UNY148) or sso1Δ/2ts pep4Δ vps4Δ (UNY142) cells were analyzed by electron microscopy after 1.5 h starvation. Scale bar, 500 nm.

(E) Cultures of vam3ts (UNY162), atg1Δ (TYY164), sec9-4 and sso1Δ/2ts (H603) cells were pre-incubated at 34°C for 30 min, shifted to starvation conditions for 1 h at the NPT and analyzed for sensitivity to proteinase K (PK) with or without 0.2% Triton X-100 (TX) as described in the Supplement. See also Figure S2.

Next, we performed the Pho8Δ60 assay that quantitatively measures the magnitude of autophagy. Wild-type cells showed a clear induction in Pho8Δ60 activity after incubation in starvation medium at both 24°C and 34°C (Figure 2B). In contrast, in the atg1Δ mutant where autophagy is completely blocked, the Pho8Δ60 activity did not increase. In the sso1Δ/2ts and sec9-4 strains, the Pho8Δ60 activity was somewhat lower than that of the wild type at the PT, indicating some defect even under these conditions, whereas at the NPT both mutants displayed essentially a complete block in autophagy (Figure 2B). The autophagy activities of sso1Δ/2ts or sec9-4 mutants again recovered when the cells were shifted back to PT (SD-N Recovery). Although we found that the exocytic Q/t-SNAREs were required for autophagy, deletion of the R/v-SNAREs Snc1/2 had no effect on this process, suggesting that a subset, but not all, of the exocytic SNARE complex is involved in autophagy (Figure S2B).

In S. cerevisiae, the cytoplasm to vacuole targeting (Cvt) pathway is a constitutive biosynthetic route that shares most of its molecular components with nonspecific autophagy, and is used for the delivery of certain resident vacuolar hydrolases such as precursor aminopeptidase I (prApe1). We investigated whether the aforementioned SNARE proteins are involved in the Cvt pathway by examining the maturation kinetics of prApe1 by a pulse-chase experiment. When examined at the NPT, the SNARE mutants showed a significant delay in prApe1 maturation kinetics compared with wild-type cells; however, the block in prApe1 maturation was more severe in the sso1Δ/2ts mutant (Figure 2C).

The sso1Δ/sso2ts Mutant Is Defective in Autophagosome Formation

To understand the nature of the autophagic defect in the SNARE mutants, we examined the ultrastructure of autophagic bodies that are formed in the sso1Δ/2ts mutant by electron microscopy. In a wild-type strain carrying a deletion of PEP4 (the gene encoding vacuolar proteinase A) and VPS4 (required for the multivesicular body pathway), after 1.5 h starvation at NPT, there were 7.25 ± 0.49 autophagic bodies per vacuole (mean ± SEM, n = 48; Figure 2D). In contrast, under the same conditions, autophagic bodies were hardly visible in the sso1Δ/2ts pep4Δ vps4Δ strain; the average number of autophagic bodies was 0.69 ± 0.22 (mean ± SEM, n = 53; Figure 2D).

Next, we examined whether Sso1/2 and Sec9 function at the stage of autophagosome biogenesis by examining the ability of the sso1Δ/2ts or sec9-4 mutants to sequester GFP-Atg8 in completed autophagosomes, rendering this chimeric protein insensitive to exogenously added proteinase K. Spheroplasts generated from cells shifted to starvation conditions for 1 h at NPT, were osmotically lysed, and treated with proteinase K either in the presence or absence of detergent. The vam3Δ strain accumulates completed autophagosomes; the population of GFP-Atg8 that is enclosed within autophagosomes was insensitive to treatment with proteinase K alone in this strain (Figure 2E). Consistent with a block in autophagosome formation in the atg1Δ mutant, all of the GFP-Atg8 was accessible to proteinase K in the absence or presence of detergent. The protease protection pattern in the sec9-4 and sso1Δ/2ts strain was similar to that seen in atg1Δ cells, indicating that the Q/t-SNAREs Sso1/2 and Sec9 are required for sequestering vesicle completion (Figure 2E). We independently confirmed this result by examining the ability of the sso1Δ/2ts mutant to sequester prApe1 at the NPT by monitoring its sensitivity to exogenously added proteinase K; the data again suggested that Sso1/2 are required for sequestering vesicle completion (Figure S2C).

Sso1/2 and Sec9 Are Required for Efficient Atg9 Cycling and Atg8 Recruitment

Atg9 is a critical component that affects autophagosome biogenesis and localizes to several peripheral cytoplasmic sites and the PAS (Mari et al., 2010; Noda et al., 2000; Reggiori et al., 2005). The anterograde movement of Atg9 from peripheral sites to the PAS is diminished in a sec2 mutant (Geng et al., 2010). Thus, we hypothesized that Atg9 localization would be affected in the sso1Δ/2ts and sec9 mutants. Wild-type or sso1Δ/2ts cells expressing Atg9-3xGFP, and the PAS marker RFP-Ape1, were incubated in nitrogen starvation medium at NPT, then observed by fluorescence microscopy. In wild-type cells, Atg9-3xGFP localized as multiple puncta; in approximately 56% of the cells, one of the Atg9-3xGFP puncta colocalized with RFP-Ape1 (Figure 3A and 3B). In contrast, in the sso1Δ/2ts mutant, Atg9-3xGFP was observed at the PAS in only 13% of the cells (Figure 3A and 3B), suggesting that efficient anterograde movement of peripheral pools of Atg9-containing vesicles to the PAS may require a SNARE-mediated membrane fusion event. Similar results were seen in the sec9-4 mutant; Atg9 colocalized with the PAS marker in approximately 20% of the cells (Figure S3A and S3B).

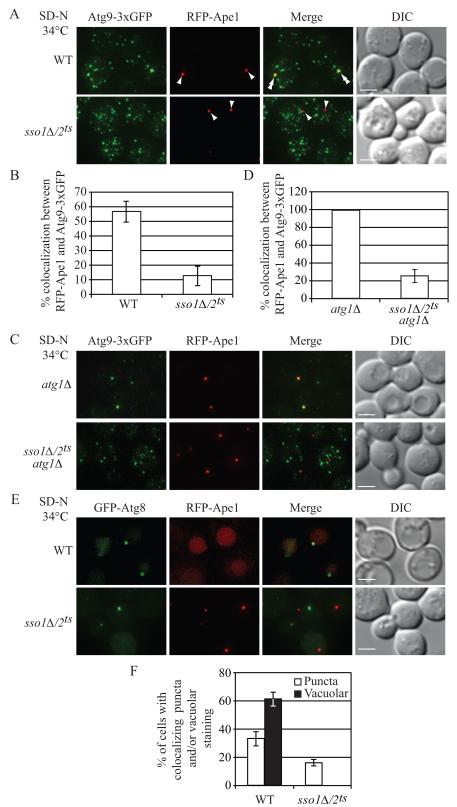

Fig. 3. Atg9 Anterograde Movement and Atg8 Localization Are Impaired in the sso1Δ/2ts Mutant.

Wild-type (WT, UNY145) or sso1Δ/2ts (UNY138) cells expressing Atg9-3xGFP and RFP-Ape1 were grown in rich medium to mid-log phase and shifted to NPT for 0.5 h. Incubation was continued for 0.5 h in nitrogen-starvation medium. The cells were fixed, and examined by fluorescence microscopy. For each picture, sixteen Z-section images were captured and projected. Arrowheads mark the position of RFP-Ape1 at the PAS, and double arrowheads mark overlaps of Atg9-3xGFP and RFP-Ape1. (A) Representative projected images.

(B) Quantification of colocalization. Error bars, standard error of the mean (SEM) from three independent experiments; n = 218 for the wild type, and 447 for the mutant.

(C) Representative projected images showing the transport of Atg9 after knocking out ATG1 in wild-type (UNY149) or sso1Δ/2ts (UNY140) cells.

(D) Quantification of colocalization. Error bars are SEM from three independent experiments; n = 150 for the wild type and the mutant. Scale bar, 2.5 μm.

(E) WT (UNY146) or sso1Δ/2ts (UNY147) cells expressing RFP-Ape1 and transformed with a plasmid encoding GFP-Atg8, were grown in SMD-Ura medium, shifted to NPT for 30 min, and incubated in nitrogen-starvation medium at the NPT for 1 h. Cells were fixed and fluorescence microscopy was performed.

(F) Quantification of colocalization. The error bars indicate the SEM; n = 256 for wild type, and 310 for the mutant. Scale bar, 2.5 μm. DIC, differential interference contrast. See also Figure S3.

To confirm these results, we used an epistasis assay in which we deleted ATG1 in the sso1Δ/2ts mutant. In an atg1Δ strain, the retrograde transport of Atg9-3xGFP from the PAS is blocked (Reggiori et al., 2004a), and the fluorescent protein is restricted to the PAS unless a secondary mutation interferes with its anterograde transport. In the atg1Δ mutant, at the NPT under starvation conditions, Atg9-3xGFP was present as a single PAS punctum (Figure 3C and 3D). Under the same conditions, in the atg1Δ sso1Δ/2ts mutant, Atg9 was present in multiple puncta, consistent with a defect in the anterograde movement of Atg9. Furthermore, colocalization between Atg9-3xGFP and RFP-Ape1 could only be observed in approximately 25% of these cells (Figure 3C and 3D).

We extended our analysis of autophagosome formation to include GFP-Atg8. In wild-type cells, after incubation at the NPT in nitrogen starvation medium, two different categories of GFP-Atg8 fluorescence signals could be visualized: In approximately 35% of the cells, GFP-Atg8 clearly colocalized with RFP-Ape1 puncta at the PAS, and in approximately 60% of the cells, GFP-Atg8 was present in the vacuole (Figure 3E and 3F). In the sso1Δ/2ts mutant, the targeting of GFP-Atg8 to the PAS was drastically affected; approximately 85% of the cells showed both GFP-Atg8 and RFP-Ape1 puncta, with no colocalization between the two marker proteins. Consistent with a complete block in autophagy (Figure 2A and 2B), vacuolar GFP-Atg8 staining was not observed in the sso1Δ/2ts mutant (Figure 3E and 3F). Finally, there was a much higher level of RFP-Ape1 detected in the vacuole in the wild type compared to the sso1Δ/2ts strain (Figure 3E) in agreement with the defect in prApe1 import in the mutant strain (Figure 2C).

To determine the stage at which vesicle formation is defective, we examined the localization of two early markers of vesicle formation, Atg11 or Atg1, in the sso1Δ/2ts mutant. In wild-type or sso1Δ/2ts cells incubated in rich or starvation media at NPT, there was no difference in the localization pattern of GFP-Atg11 or GFP-Atg1 respectively, which colocalized with RFP-Ape1 (Figure S3C, S3D, S3E and S3F). Taken together, these results underscore the requirement of Sso1 and Sso2 in the movement of Atg9 containing reservoirs to the PAS, but not for the colocalization between early Atg markers and RFP-Ape1.

The Formation of the Atg9-Containing Tubulovesicular Clusters Is Disrupted in the sso1Δ/2ts Mutant

Next, in order to gain mechanistic insight into the role of the exocytic Q/t-SNAREs in autophagosome formation, in particular on the membrane dynamics during this event, we analyzed the ultrastructure of the Atg9-containing compartments by immuno-EM as described previously (Mari et al., 2010). Wild-type (pep4Δ) or pep4Δ sso1Δ/2ts cells expressing Atg9-GFP were grown at 24°C in YPD medium and then shifted to 34°C in either YPD or SD-N and examined by immuno-EM. In a wild-type strain grown in rich medium or starved, Atg9-GFP-positive structures appear as a cluster of vesicles and tubules (Mari et al., 2010). Similar clusters could infrequently be observed in the sso1/2ts mutant at the PT (Figure 4A). As previously published, the sso1Δ/2ts cells accumulated clusters of secretory vesicles even at the PT (Jantti et al., 2002), and Atg9 labeling was more prominent and principally localized to these structures (Figure 4B), which often were also associated with one electron-dense circular structure (Figure 4B, asterisk). Certain secretory mutants such as sec4 accumulate two different populations of vesicles, both 100 nm in diameter: One population carries cell wall and plasma membrane components, and the second carries periplasmic enzymes (Harsay and Bretscher, 1995). In the sso1Δ/2ts mutant, we observed at least two different sizes of vesicles; large (80-100 nm) and small (30-40 nm), and Atg9 appeared to be preferentially associated with the small vesicles. After 1.5 h at the NPT in rich medium, the Atg9-positive vesicles were not clustered but were more dispersed, being located among the huge number of secretory vesicles accumulated by the sso1Δ/2ts mutant (Figure 4C), often with an electron dense circular structure close by (Figure 4C, asterisk). Secretion is reduced under starvation conditions (Geng et al., 2010) and accordingly the sso1Δ/2ts mutant did not accumulate large numbers of vesicles after starvation at the NPT; instead, smaller and more circumscribed clusters of secretory vesicles were observed (Figure 4D). In this case also, Atg9 was frequently found to be associated with the smaller vesicles, but neither the tubules nor the tubulovesicular clusters positive for Atg9 were observed.

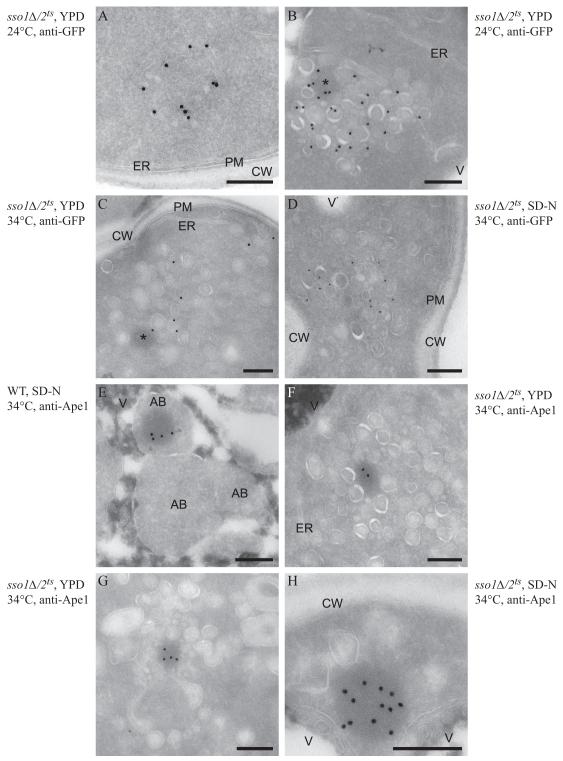

Figure 4. Ultrastructural Analysis of the Atg9-Containing Membranes and of the prApe1 Oligomer.

Wild-type (WT, UNY151, panel E) and sso1Δ/2ts (UNY141, panels A-D and F-H) cells were grown to exponential phase at PT (panels A and B) before being shifted to NPT (panels C-H) in either rich (YPD, panels A-C, F and G) or nitrogen starvation medium (SD-N, panels D, E and H) for 1.5 h. Cells were processed for immuno-EM as described in the Supplement before and after the temperature and the medium changes. Cryo-sections shown in panels A to D were immuno-labelled for GFP to detect Atg9-GFP, while those presented in panels E to H were immuno-labelled for Ape1. (A) A tubulovesicular cluster detected infrequently in the mutant strain.

(B) Overview of a cluster of secretory vesicles that also contain Atg9-positive carriers.

(C, D) The Atg9-containing vesicles are more dispersed throughout the cytoplasm in the sso1Δ/2ts mutant shifted to NPT.

(E) Autophagic bodies accumulated in the vacuole of nitrogen-deprived wild-type cells, and some of them contain the electron-dense prApe1 oligomer.

(F and G) The prApe1 oligomer is associated with vesicular structures in the sso1Δ/2ts mutant shifted to NPT in rich medium.

(H) In the sso1Δ/2ts cells nitrogen starved at NPT, the prApe1 oligomer is associated with 1-3 large vesicles. The asterisks mark the circular electron-dense structures that correspond to prApe1 oligomers, often observed in proximity to Atg9-positive membranes. Scale bar, 200 nm. AB, autophagic body; CW, cell wall; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; PM, plasma membrane; V, vacuole. See also Figure S4.

To better understand the ultrastructure of the PAS in the sso1Δ/2ts mutant, we carried out immuno-labeling with anti-Ape1 antibody to localize prApe1 oligomers, which are typically associated with this site. In the wild-type strain grown in rich medium at 24°C, the prApe1 oligomer was rarely observed, but when detected, it was associated with a cluster of vesicles and tubules as expected, which represents the PAS or the Atg9 reservoirs (data not shown; (Mari et al., 2010). In the same cells starved at 34°C, the cytoplasmic prApe1 complex was seldom observed, due to the increase of the autophagic flux that transports this complex to the vacuole more efficiently, and, as a result, the prApe1 oligomer was often found in the interior of autophagic bodies (Figure 4E). This proteinaceous structure was much more easily detected in the cytoplasm of the sso1Δ/2ts mutant shifted to NPT in either rich or starvation medium as a direct consequence of the block in the Cvt pathway and autophagy. In the presence of nutrients, the prApe1 oligomer was found embedded within the clusters of secretory vesicles, and it appeared to be preferentially associated with small vesicles, but again no tubules were observed (Figures 4F and 4G). The distinct morphological appearance of the prApe1-containing complex suggested that the circular electron dense structures observed in the labeling for Atg9-GFP (Figures 4B and 4C, asterisks) were prApe1 oligomers. Under starvation conditions, the prApe1 oligomer in the sso1Δ/2ts mutant was in most cases exclusively associated with 1 to 3 large vesicles, and not with small vesicles or tubules (Figures 4H).

To further visualize the nature of the phagophore membrane in the sso1Δ/2ts mutant, we extended this analysis by immuno-localizing GFP-Atg8. In contrast to the wild type, GFP-Atg8 appeared to be primarily dispersed throughout the cytosol, or associated with certain vesicular structures, although occasionally we could detect this protein decorating the phagophore membrane in the mutant strain (Figure S4). Taken together, the results of our immuno-EM experiments suggest that the exocytic Q/t-SNARES appear to be primarily involved in the organization of the Atg9-positive membranes into tubulovesicular clusters, which are key in the generation of the PAS, and therefore autophagosome biogenesis and normal autophagy progression.

The Defect in Autophagy Is Not Due to the Accumulation of Exocytic Vesicles

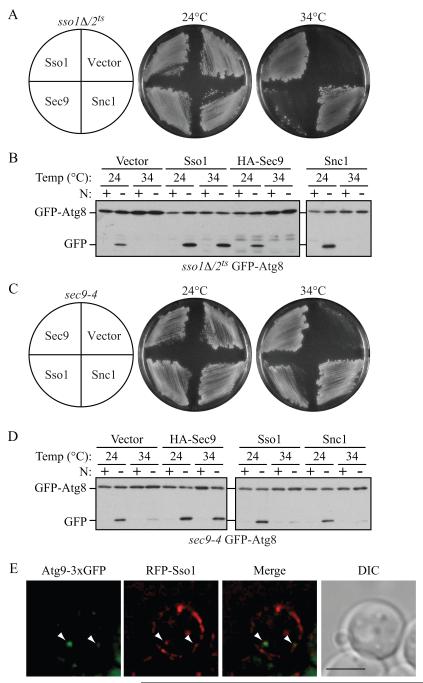

We wanted to examine whether the autophagy defect in the SNARE mutants could be an indirect effect caused by a paucity of membrane for autophagosome biogenesis, due to the accumulation of exocytic vesicles. The overexpression of SNC1 in the sso1Δ/2ts mutant strongly suppresses the temperature sensitive growth defect (Jantti et al., 2002). We found that the overexpression of Snc1 was indeed able to rescue the growth defect, but not the block in autophagy in the sso1Δ/2ts mutant at 34°C (Figure 5A and 5B). The overexpression of Sso1 was able to complement the defects in both growth and autophagy in the sso1Δ/2ts mutant, whereas transformation with a plasmid that overexpresses SEC9 poorly suppressed the growth defect, but was unable to rescue the block in autophagy. Similarly, we found that the overexpression of Snc1 or Sso1 in the sec9-4 mutant restored the growth but not the autophagy defect at 34°C (Figure 5C and 5D). These results suggest that the alleviation of the secretion defects in the sec9-4 or sso1Δ/2ts mutants is not sufficient for restoring normal levels of autophagy. Furthermore, they also suggest that each of these SNARE proteins has a specific role in autophagy that cannot be compensated by simply overexpressing another SNARE protein.

Fig. 5. The Overexpression of SNAREs Involved in Secretion Cannot Suppress the Autophagy Defect in the sso1Δ/2ts or sec9-4 Mutants.

(A and C) sso1Δ/2ts (H603) or sec9-4 cells expressing GFP-Atg8 were transformed with a plasmid expressing the indicated protein. The cells were streaked on two plates; one was incubated at 24°C and the other at 34°C, and growth was monitored after 72 h.

(B and D) The sso1Δ/2ts (H603) and sec9-4 strains above were cultured in rich medium at 24°C to mid-log phase. For each strain, half of the culture was shifted to the restrictive temperature (34°C) for 30 min, whereas the rest remained at permissive temperature (24°C). Cells were starved for 2 h at the same temperatures, and samples were collected before and after starvation. Autophagy activity was determined by examining GFP-Atg8 processing.

(E) Representative image showing the colocalization between a cytosolic RFP-Sso1 punctum and Atg9-3xGFP. Wild-type (UNY108) cells were transformed with a plasmid expressing CUP1 promoter-driven RFP-Sso1. Overnight cultures of cells grown in SMD medium at 30°C were diluted to an OD600 = 0.2 in the same medium and grown until OD600 = 0.6. The cells were then observed by fluorescence microscopy. The arrowheads mark examples of overlapping puncta. DIC, differential interference contrast. Scale bar, 5 μm. See also Figure S5.

Consistent with a recent mammalian study, temperature-sensitive mutations in several exocyst components in yeast result in a block in autophagy (Figure S5A), presumably because their inactivation blocks SNARE assembly (Grote et al., 2000). In mammalian cells, clathrin-mediated endocytosis of the plasma membrane is involved in the formation of pre-autophagic structures (Ravikumar et al., 2010); however, we found that endocytosis is dispensible for autophagy in yeast (Figure S5B; Reggiori et al., 2004b), suggesting that in this organism if the plasma membrane is one of the sources for autophagosome formation, it is transported to the PAS by a mechanism that is independent of endocytosis.

Thus far, our results show that the exocytic SNAREs are involved in the formation of the tubulovesicular clusters of Atg9. One prediction from this result is that we would be able to observe colocalization between Sso1 and Atg9. To test this prediction, we transformed wild-type cells expressing Atg9-3xGFP with a plasmid bearing RFP-Sso1, and examined the localization of these chimeric proteins both under rich conditions and in starvation medium. Consistent with previous observations (Scott et al., 2004), Sso1 predominantly showed patchy plasma membrane localization (Figure 5E). In addition, RFP-Sso1 showed cytosolic puncta; these puncta were also observed in experiments localizing endogenous Sso1 by immunofluorescence (Scott et al., 2004). We observed colocalization between Atg9-3xGFP and cytosolic RFP-Sso1 puncta in cells exhibiting both fluorophores when grown in rich medium (Figure 5E), as well as in cells shifted to starvation medium (data not shown). In contrast, we rarely observed any colocalization between GFP-Sso1 and the PAS marker RFP-Ape1 (data not shown).

Tlg2 Is required for Atg9 Cycling and Forms a Novel Complex with Sso1 and Sec9

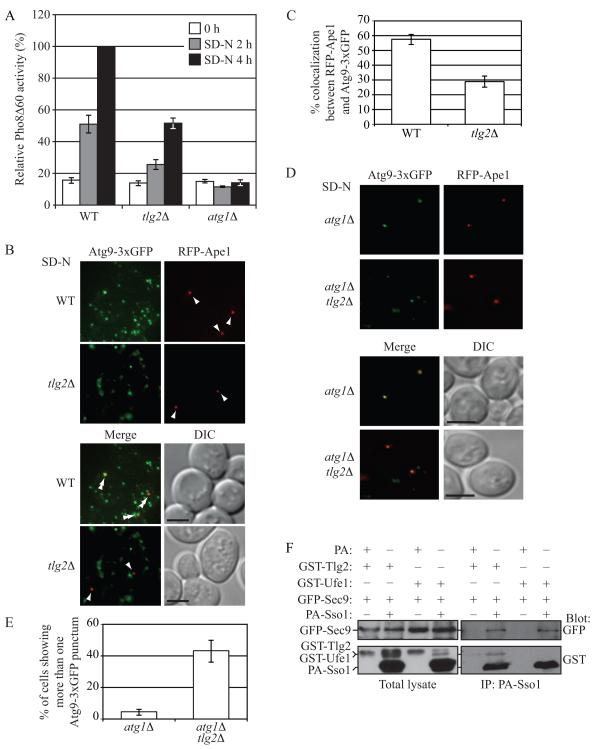

In order to understand how the function of the exocytic Q/t-SNARES in autophagosome formation is regulated, we examined the role of additional SNARE proteins in this process. The Q/t-SNARE Tlg2 localizes to the early endosome, and is required for efficient endocytosis and maintenance of normal levels of TGN proteins (Holthuis et al., 1998). It was previously shown to be required for the Cvt pathway, but not for nonspecific autophagy (Abeliovich et al., 1999). Tlg2 is not required for anterograde traffic through the Golgi complex or vacuolar protein delivery (Abeliovich et al., 1999; Holthuis et al., 1998); therefore, the defect in the Cvt pathway in the tlg2Δ mutant is not likely to be due to a block in the trafficking of an essential Cvt component through the secretory pathway, or due to a block in the delivery of vacuolar proteases. When we examined the role of Tlg2 using the quantitative Pho8Δ60 assay, tlg2Δ mutant cells displayed a significant reduction in activity (Figure 6A), although not as severe as the sso1Δ/2ts mutant (Figure 2A and 2B) that showed an essentially complete block in autophagy.

Fig. 6. Tlg2 Determines the Magnitude of Autophagy, Affects Atg9 Anterograde Transport, and Interacts with Sso1 and Sec9.

(A) Wild-type (WT; BY4742), tlg2Δ (KWY76) or atg1Δ (UNY5) cells were grown in rich medium to mid-log phase, then shifted to nitrogen-starvation medium for the indicated time points, and Pho8Δ60 activity was determined. The activity measured from wild-type cells was set to 100%, and the other values were normalized. Error bars are SD from three independent experiments.

(B) Wild-type (JGY191) or tlg2Δ (UNY159) cells expressing Atg9-3xGFP and RFP-Ape1 were grown in rich medium to mid-log phase and shifted to nitrogen-starvation medium for 0.5 h after which cells were examined by fluorescence microscopy. Arrowheads indicate the position of RFP-Ape1 at the PAS, and double arrowheads show overlaps between Atg9-3xGFP and RFP-Ape1.

(C) Quantification of colocalization. The error bars represent SEM from three independent experiments; n = 102 for the wild type, and 116 for the mutant.

(D) Representative images showing the transport of Atg9 after knocking out ATG1 in wild-type (UNY171) or tlg2Δ (UNY170) cells.

(E) The average percentage of cells showing more than one Atg9-3xGFP punctum. The error bars are SEM from three independent experiments; n = 114 for the wild type, and 121 for the mutant. Scale bar, 5 μm.

(F) Cells expressing GST-Tlg2 or GST-Ufe1 under the control of the GAL1 promoter (UNY168 and UNY180, respectively) were transformed with the indicated plasmids; CUP1 promoter-driven PA-Sso1 and GFP-Sec9 in the case of the experimental strain, or CUP1 promoter-driven PA alone and empty vector for the control strain. Cells were grown in SMG medium to OD600 = 1.0 and shifted to SG-N for 1 h. Spheroplasts prepared from these cells were subjected to DSP cross linking as described in the Supplement. Cell lysates were prepared and subjected to affinity isolation with IgG sepharose. See also Figure S6.

Furthermore, the frequency of colocalization of Atg9-3xGFP with RFP-Ape1 dropped from approximately 55% in the wild-type strain to less than 30% in the tlg2Δ strain (Figure 6B and 6C). To confirm that the defect in Atg9-3xGFP localization to the PAS was due to a defect in its anterograde transport, we additionally deleted ATG1 in the tlg2Δ strain, and performed an epistasis analysis as described in Figure 3. In the atg1Δ mutant under starvation conditions, in cells expressing both chimeric proteins, Atg9-3xGFP and RFP-Ape1 colocalized in 100% of the cells examined (Figure 6D and data not shown); in contrast, in the atg1Δ tlg2Δ mutant, colocalization was approximately 84% (Figure 6D and data not shown). Furthermore, in atg1Δ cells under starvation conditions, Atg9-3xGFP was predominantly present as a single PAS punctum, whereas in the atg1Δ tlg2Δ mutant, Atg9 was present in multiple puncta in approximately 43% of the cells examined, consistent with a defect in the anterograde movement of this protein (Figure 6D and 6E).

To extend our analysis, we examined the interaction between protein A (PA) tagged Sso1, GFP-Sec9 and GST-Tlg2 from cross-linked extracts prepared from wild-type cells that were starved for 1 h. Both GST-Tlg2 and GFP-Sec9 co-isolated with PA-Sso1, but not PA alone, indicating the existence of a complex in vivo (Figure 6F). Furthermore, under the same conditions, PA-Sso1 could not co-isolate another t-SNARE, GST-Ufe1, suggesting a specific interaction between PA-Sso1 and GST-Tlg2. Previous work examining SNARE interactions in vitro found that Sso1 and Sec9 functionally interacted with four R/v-SNARE proteins, Snc1, Snc2, Sec22 and Nyv1 (McNew et al., 2000). However, the possibility that Sso1-Sec9 may interact with other SNAREs like Tlg2 was not explored. Considering that Tlg2 is found in a complex with PA-Sso1, we asked if Tlg2 was capable of driving fusion with Sso1-Sec9 in vitro. Recombinant Sso1-Sec9, Snc1 and Tlg2 were reconstituted into proteoliposomes and their ability to drive membrane fusion was determined. Whereas the cognate SNARE pair Sso1-Sec9-Snc2 displayed robust lipid mixing, Sso1-Sec9-Tlg2 was unable to do so, even when the regulatory Habc domain of Tlg2 was removed (H3-Tlg2) (Figure S6). We also examined the possibility that Tlg2 requires activation, as it does with its known t-SNARE partners Tlg1 and Vti1 (Paumet et al., 2001); nevertheless, no fusion was seen in the presence of the C-terminal Snc2 peptide. Thus, it is possible that an additional factor or some type of posttranslational modification is needed to reconstitute this fusion activity in vitro.

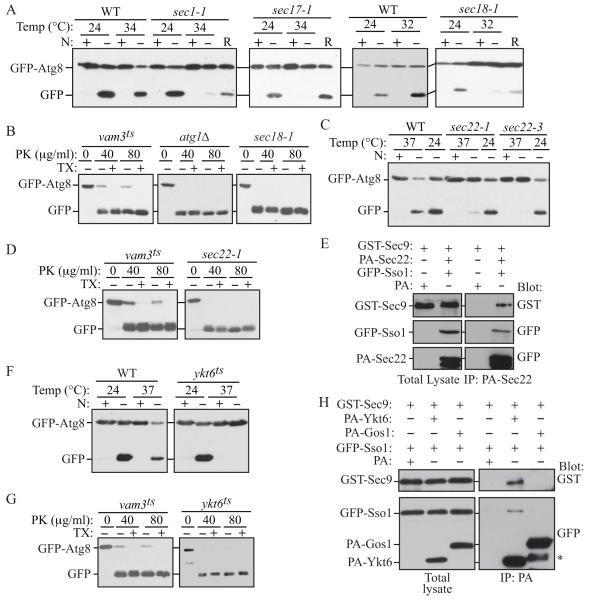

The SM family protein Sec1, N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein (NSF) Sec18, and the R/v-SNAREs Sec22 and Ykt6 are required for autophagy

Proteins of the Sec1/Munc18 family interact with SNAREs to regulate SNARE complex assembly and play complementary roles in fusion. There are four SM family proteins in yeast: Sec1, Vps45, Sly1, and Vps33. Of these proteins, Vps45, which associates with Tlg2, has previously been shown to be required for the Cvt pathway (Abeliovich et al., 1999). Sec1 is required for exocytosis and forms a complex with the exocytic SNAREs (Carr et al., 1999). Because of the role of Sso1/2 and Sec9 in autophagy, we asked if Sec1 was also required for this process. Indeed, the temperature sensitive sec1-1 mutant showed a block in autophagy (Figure 7A).

Fig. 7. Autophagy Is Impaired in the Absence of Sec1, Sec18, and the R/v-SNAREs Sec22 and Ykt6.

(A, C and F) The indicated mutant and the corresponding wild-type (BY4742) strains were analyzed with the GFP-Atg8 processing assay in rich or nitrogen starvation conditions. R, recovery.

(B, D and G) vam3ts (UNY162), atg1Δ (TYY164), sec18-1, sec22-1 and ykt6ts cells expressing GFP-Atg8 were pre-incubated at 34°C for 30 min, shifted to starvation conditions for 1 h at the NPT and examined for sensitivity to proteinase K (PK) with or without 0.2% Triton X-100 (TX) as described in the Supplement.

(E and H) Cells expressing GST-Sec9 under the control of the GAL1 promoter (UNY172) were transformed with the indicated plasmids; CUP1 promoter-driven PA-Sec22, PA-Ykt6 or PA-Gos1, and GFP-Sso1, or CUP1 promoter-driven PA alone and GFP-Sso1. Cells were grown in SMG medium medium to OD600 = 1.0 and shifted to SG-N for 1 h. Spheroplasts prepared from these cells were subjected to DSP cross linking as described in the Supplement. Cell lysates were prepared and subjected to affinity isolation with IgG sepharose. The asterisk indicates a non-specific band. See also Figure S7.

Previously, both the α-SNAP protein Sec17 and the NSF protein Sec18, which mediate the disassembly of SNARE complexes (Mayer et al., 1996), were shown to be required for autophagy; temperature sensitive sec17-1 and sec18-1 mutants show no induction in Pho8Δ60 activity under starvation conditions at NPT (Isahara et al., 1999; Ishihara et al., 2001). However, that study reported that Sec18 is not required for autophagosome formation, but for the fusion of completed autophagosomes with the vacuole. We observed a strong block in autophagy as assayed by the GFP-Atg8 processing assay in both the SEC17 and SEC18 mutants (Figure 7A) and a significant delay, but not a complete block, in prApe1 maturation kinetics compared with wild-type cells at NPT in rich conditions (Figure S7A). In the previous study that concluded that sec18 was not required for autophagosome biogenesis, the authors examined the protection accessibility of steady state levels of membrane-associated prApe1 in sec18-1 cells shifted to starvation conditions at NPT. The results show that prApe1 is partially insensitive to proteinase K alone under those conditions; however, since prApe1 maturation is not completely blocked in this mutant at the time the assay was performed, a population of this oligomer was already transported to the vacuole, rendering it insensitive to exogenous proteinase K. We repeated the protease protection assay in which we examined the ability of the sec18-1 mutant to sequester GFP-Atg8 in completed autophagosomes by monitoring the sensitivity of this chimeric protein to exogenously added proteinase. In the vam3ts mutant, a portion of GFP-Atg8 was insensitive to proteinase K treatment alone (Figure 7B). In contrast, the protease protection pattern in the sec18-1 mutant was similar to that seen in the atg1Δ mutant, indicating that Sec18 is required for autophagosome biogenesis (Figure 7B).

Of the four R/v-SNAREs that were shown to interact with Sso1 and Sec9 in vitro (McNew et al., 2000); we found that the inactivation of Snc1, Snc2, and Nyv1 have no affect on autophagy (Figure S2B and data not shown). However, two separate temperature sensitive alleles of sec22, sec22-1 and sec22-3, showed severe blocks in autophagy and a kinetic delay in the Cvt pathway at the NPT in starvation conditions (Figure 7C and Figure S7B). Similarly, we found that Sec22 is required for autophagosome biogenesis as determined by a GFP-Atg8 protease protection assay (Figure 7D). We next tested whether a complex between Sec22, Sso1 and Sec9 could be detected in vivo, and were able to isolate a complex between PA-Sec22, GST-Sec9 and GFP-Sso1 from cross-linked extracts prepared from wild-type cells that were starved for 1 h (Figure 7E).

Sec22 localizes to both the ER and the Golgi, and functions in ER-Golgi anterograde and retrograde transport (Liu and Barlowe, 2002; Liu et al., 2004). Both sec22-1 and sec22-3 mutants showed defects in the anterograde transport of Atg9 to the PAS, when grown at the NPT in both rich medium and starvation conditions (Figure S7C and data not shown). We were able to observe some colocalization between Atg9-3xGFP and RFP-Sec22 (Figure S7D), although at present we do not know whether this is because of a disruption of the trafficking route of Atg9 through the ER, or whether a small amount of Sec22 colocalizes with Sso1/2 at the Atg9 peripheral sites to facilitate the formation of Atg9 tubulovesicular structures that then translocate to the PAS.

The R/v-SNARE Ykt6 is very versatile in that it participates in the secretory pathway at the early Golgi stage, and in three separate vacuole targeted vesicular routes, the ALP, CPY and Cvt pathways. Additionally, the overexpression of Ykt6 can overcome the growth defects of the sec22 temperature sensitive mutants at the NPT, and in ER-to-Golgi transport (Liu and Barlowe, 2002; McNew et al., 1997). Accordingly, we tested the role of the ykt6 temperature sensitive mutant in autophagy, and observed a severe block in GFP-Atg8 processing at the NPT under nitrogen-deprivation conditions (Figure 7F). Furthermore, GFP-Atg8 protease protection results suggested that Ykt6 is required for autophagosome formation (Figure 7G). This result was unexpected because Ykt6 is known to have a role in homotypic vacuole fusion where it forms a complex with the t-SNAREs Vam3 and Vam7 (Ungermann et al., 1999), which are also required for the fusion of completed autophagosomes with the vacuole; consequently Ykt6 was assumed to function in autophagosome-vacuole fusion. Our results therefore suggest that Ykt6 may function at more than one step in autophagy. We found that RFP-Ykt6 colocalized with Atg9-3xGFP (Figure S7E), and that PA-Ykt6, but not another v-SNARE, PA-Gos1, could bind GST-Sec9 and GFP-Sso1 in vivo (Figure 7H). Previously it was shown that Ykt6 can function as a v-SNARE with Sso1 and Sec9 in vitro, when it is artificially attached to a membrane through a trans-membrane peptide anchor, but not when it is anchored to the membrane via its native C20 lipid chain (McNew et al., 2000), leading to the conclusion that Ykt6 lipid-anchoring prevents it from functioning as a v-SNARE, thus imparting specificity in SNARE pairing. However, it is also possible that the membrane anchored Ykt6 may require other factors or may need to be palmitoylated (Fukasawa et al., 2004) in order to drive liposome fusion in vitro. Taken together, we have found roles for two v-SNAREs, Sec22 and Ykt6, which can be found in a complex with Sso1-Sec9 in vivo, in autophagosome formation.

DISCUSSION

One of the central questions in autophagy concerns the mechanism of phagophore and autophagosome formation. In membrane trafficking in the secretory pathway, cargo-containing vesicles are formed from a preexisting organelle by budding. In contrast, vesicle formation in autophagy is considered to occur de novo, where different organelles donate membrane for phagophore expansion. This is critical for autophagic function, where sequestering vesicles of varying sizes (between 300 and 900 nm in diameter) have to be formed to accommodate different cargo. Our results suggest that Atg8–PE is not likely to drive phagophore membrane expansion through membrane hemifusion at physiological concentrations of PE (Figure 1). Recently, the mammalian homologues of Atg8 were shown to possess membrane fusing activity in in vitro liposome assays using a maleimide-linkage strategy that is conceptually similar to our own (Figure 1 and S1) except for the inclusion of a higher amount of maleimide lipid (15% of the total lipid in the system) and a greater proportion of unsaturated acyl chains (>75%) (Weidberg et al., 2011). We are actively exploring how these changes in lipid composition might facilitate fusion. However, in light of these intriguing results, it now becomes important to establish whether mammalian Atg8 homologues can fuse physiologically relevant liposomes when coupled directly to PE via Atg7-Atg3 enzymatic reactions.

It has recently been proposed that the only transmembrane protein required for autophagy, Atg9, localizes to novel compartments made up of vesicles and tubules which undergo fusion, and translocate as a group to a perivacuolar site where they form the PAS (Mari et al., 2010). The observations from our work indicate that loss-of-function mutations in the exocytic Q/t-SNAREs result in the absence of tubules in the Atg9 membrane clusters (Figure 4), and suggest a role for these SNAREs in a very early event in autophagosome biogenesis. At present, although we have no direct evidence, our results suggest that SNAREs play a role in fusion events generating tubulovesicular structures of Atg9 that serve as PAS precursors. Further, from our work it appears that although the exocytic Q/t-SNAREs may be the principal SNAREs in Atg9 tubulovesicular clustering, the endosomal Q/t-SNARE Tlg2 could also play a similar role (Figure 6).

The role for the previously known SNAREs in autophagy further exemplifies a recurring theme in yeast in the use of common components that act at multiple locations along with specificity factors to drive particular reactions. For example, TRAPP functions as a vesicle tether and GEF in at least three locations—TRAPPI acts in ER-to-Golgi trafficking, TRAPPII at the trans-Golgi-endosome, and TRAPPIII in autophagy (Lynch-Day et al., 2010). Specificity factors dictate the pathway that each TRAPP complex participates in; for example, Trs85 directs TRAPP to function in autophagy. The same situation appears to hold true for at least some SNAREs. Future research will focus on identifying components downstream of Sec4 that communicate with these SNAREs to ensure their specificity during autophagosome biogenesis, and additional work will be needed to clarify the sources of membrane and the mechanism of expansion of the phagophore.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strains and Plasmids

The strains used in this study are listed in Supplemental Table S1. The construction of plasmids is described in the Supplement.

In Vitro Fusion Reactions

Details of the methods used for lipid preparation, Atg8 conjugation to PE and the lipid fusion assay are described in the Supplement. In brief, labeled liposomes were generated containing NBD and rhodamine. Unlabeled liposomes were mixed with the labeled liposomes at a ratio of 4:1, incubated at 30°C, and the NBD fluorescence was monitored continuously; fusion results in dilution of the fluorophores such that rhodamine no longer quenches NBD. This dequenching is measured as an increase in fluorescence.

Turbidity Tethering Assay

The liposome sample absorbance was monitored following Atg8ΔR coupling reactions; increased tethering results in a higher turbidity reading. Details are described in the Supplement.

Protein A Affinity Isolation

Spheroplasts were treated with cross-linker, and PA-tagged proteins were affinity purified with IgG Sepharose. After reversal of the cross-link, recovered proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and detected by western blot. Details are described in the Supplement.

Assays for Autophagic Flux

Pho8Δ60-dependent alkaline phosphatase activity was monitored in strains lacking PHO13 and in which the PHO8 gene was replaced with pho8Δ60, encoding a cytosolic variant of the zymogen alkaline phosphatase. This altered form of the protein is not able to enter the endoplasmic reticulum and remains in the cytosol; vacuolar delivery results in activation of the enzyme, which is measured by an increase in fluorescence. See the Supplement for additional details.

A population of GFP-Atg8, which initially lines both sides of the phagophore becomes trapped within the completed autophagosome. The GFP-Atg8 processing assay is based on the delivery of the chimera to the vacuole; GFP is liberated from Atg8 by the action of vacuolar hydrolases, such that the generation of free GFP is a measure of nonspecific autophagy. Autophagic flux is also monitored through microscopy by the appearance of GFP fluorescence in the vacuole.

Fluorescence Microscopy

For fluorescence microscopy, cells were grown to mid-log phase in YPD or SMD selective media, or shifted to SD-N before imaging. Cells were viewed with a DeltaVision Spectris microscope (Applied Precision, Issaquah, WA) fitted with differential interference contrast optics and Photometrics CoolSNAP HQ camera (Roper Scientific, Tucson, AZ), utilizing softWoRx software (Applied Precision).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Hans Ronne (Uppsala University) for providing strain H603, Dr. Charlie Boone and Zhijian Li for providing the sec mutants, Dr. Phil Hieter for providing the ykt6 mutant, Dr. Zhifen Yang for the pCUP1-PA-SEC22 and pCUP1-PA-YKT6 constructs, Dr. Midori Umekawa for pMU1 (pATG8 under the control of its endogenous promoter, with the hygromycin resistance marker) and Drs. Clinton Bartholomew (University of Michigan), and Ai Yamamoto (Columbia University) for helpful discussions. This work was supported by NIH grants GM53396 (to DJK), NS063973 (to TJM), GM071832 (to JAM) and the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development and the Utrecht University High Potential grant (to FR).

Abbreviations

- Ape1

aminopeptidase I

- Atg

autophagy-related

- Cvt

cytoplasm-to-vacuole targeting

- PAS

phagophore assembly site

- prApe1

precursor aminopeptidase I

- mApe1

mature aminopeptidase I

- PT

permissive temperature

- NPT

non-permissive temperature

- SD

standard deviation

- SEM

standard error of the mean

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Summary sentence: SNARE proteins, but not Atg8/LC3–PE, are needed for fusion in autophagy.

REFERENCES

- Aalto MK, Ronne H, Keranen S. Yeast syntaxins Sso1p and Sso2p belong to a family of related membrane proteins that function in vesicular transport. EMBO J. 1993;12:4095–4104. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06093.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abeliovich H, Darsow T, Emr SD. Cytoplasm to vacuole trafficking of aminopeptidase I requires a t-SNARE-Sec1p complex composed of Tlg2p and Vps45p. EMBO J. 1999;18:6005–6016. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.21.6005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennwald P, Kearns B, Champion K, Keranen S, Bankaitis V, Novick P. Sec9 is a SNAP-25-like component of a yeast SNARE complex that may be the effector of Sec4 function in exocytosis. Cell. 1994;79:245–258. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugger B, Nickel W, Weber T, Parlati F, McNew JA, Rothman JE, Sollner T. Putative fusogenic activity of NSF is restricted to a lipid mixture whose coalescence is also triggered by other factors. EMBO J. 2000;19:1272–1278. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.6.1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr CM, Grote E, Munson M, Hughson FM, Novick PJ. Sec1p binds to SNARE complexes and concentrates at sites of secretion. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:333–344. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.2.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernomordik LV, Kozlov MM. Protein-lipid interplay in fusion and fission of biological membranes. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:175–207. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukasawa M, Varlamov O, Eng WS, Sollner TH, Rothman JE. Localization and activity of the SNARE Ykt6 determined by its regulatory domain and palmitoylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4815–4820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401183101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng J, Nair U, Yasumura-Yorimitsu K, Klionsky DJ. Post-Golgi sec proteins are required for autophagy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:2257–2269. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-11-0969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grote E, Carr CM, Novick PJ. Ordering the final events in yeast exocytosis. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:439–452. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.2.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hailey DW, Rambold AS, Satpute-Krishnan P, Mitra K, Sougrat R, Kim PK, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Mitochondria supply membranes for autophagosome biogenesis during starvation. Cell. 2010;141:656–667. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harsay E, Bretscher A. Parallel secretory pathways to the cell surface in yeast. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:297–310. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.2.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holthuis JC, Nichols BJ, Dhruvakumar S, Pelham HRB. Two syntaxin homologues in the TGN/endosomal system of yeast. EMBO J. 1998;17:113–126. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isahara K, Ohsawa Y, Kanamori S, Shibata M, Waguri S, Sato N, Gotow T, Watanabe T, Momoi T, Urase K, et al. Regulation of a novel pathway for cell death by lysosomal aspartic and cysteine proteinases. Neuroscience. 1999;91:233–249. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00566-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara N, Hamasaki M, Yokota S, Suzuki K, Kamada Y, Kihara A, Yoshimori T, Noda T, Ohsumi Y. Autophagosome requires specific early Sec proteins for its formation and NSF/SNARE for vacuolar fusion. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:3690–3702. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.11.3690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jantti J, Aalto MK, Oyen M, Sundqvist L, Keranen S, Ronne H. Characterization of temperature-sensitive mutations in the yeast syntaxin 1 homologues Sso1p and Sso2p, and evidence of a distinct function for Sso1p in sporulation. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:409–420. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.2.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Barlowe C. Analysis of Sec22p in endoplasmic reticulum/Golgi transport reveals cellular redundancy in SNARE protein function. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:3314–3324. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-04-0204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Flanagan JJ, Barlowe C. Sec22p export from the endoplasmic reticulum is independent of SNARE pairing. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:27225–27232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312122200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch-Day MA, Bhandari D, Menon S, Huang J, Cai H, Bartholomew CR, Brumell JH, Ferro-Novick S, Klionsky DJ. Trs85 directs a Ypt1 GEF, TRAPPIII, to the phagophore to promote autophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:7811–7816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000063107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mari M, Griffith J, Rieter E, Krishnappa L, Klionsky DJ, Reggiori F. An Atg9-containing compartment that functions in the early steps of autophagosome biogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:1005–1022. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200912089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer A, Wickner W, Haas A. Sec18p (NSF)-driven release of Sec17p (α-SNAP) can precede docking and fusion of yeast vacuoles. Cell. 1996;85:83–94. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNew JA, Parlati F, Fukuda R, Johnston RJ, Paz K, Paumet F, Sollner TH, Rothman JE. Compartmental specificity of cellular membrane fusion encoded in SNARE proteins. Nature. 2000;407:153–159. doi: 10.1038/35025000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNew JA, Sogaard M, Lampen NM, Machida S, Ye RR, Lacomis L, Tempst P, Rothman JE, Sollner TH. Ykt6p, a prenylated SNARE essential for endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi transport. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17776–17783. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatogawa H, Ichimura Y, Ohsumi Y. Atg8, a ubiquitin-like protein required for autophagosome formation, mediates membrane tethering and hemifusion. Cell. 2007;130:165–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda T, Kim J, Huang W-P, Baba M, Tokunaga C, Ohsumi Y, Klionsky DJ. Apg9p/Cvt7p is an integral membrane protein required for transport vesicle formation in the Cvt and autophagy pathways. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:465–480. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.3.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paumet F, Brugger B, Parlati F, McNew JA, Sollner TH, Rothman JE. A t-SNARE of the endocytic pathway must be activated for fusion. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:961–968. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200104092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Protopopov V, Govindan B, Novick P, Gerst JE. Homologs of the synaptobrevin/VAMP family of synaptic vesicle proteins function on the late secretory pathway in S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1993;74:855–861. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90465-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar B, Moreau K, Jahreiss L, Puri C, Rubinsztein DC. Plasma membrane contributes to the formation of pre-autophagosomal structures. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:747–757. doi: 10.1038/ncb2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reggiori F, Shintani T, Nair U, Klionsky DJ. Atg9 cycles between mitochondria and the pre-autophagosomal structure in yeasts. Autophagy. 2005;1:101–109. doi: 10.4161/auto.1.2.1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reggiori F, Tucker KA, Stromhaug PE, Klionsky DJ. The Atg1-Atg13 complex regulates Atg9 and Atg23 retrieval transport from the pre-autophagosomal structure. Dev Cell. 2004a;6:79–90. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00402-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reggiori F, Wang C-W, Nair U, Shintani T, Abeliovich H, Klionsky DJ. Early stages of the secretory pathway, but not endosomes, are required for Cvt vesicle and autophagosome assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 2004b;15:2189–2204. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-07-0479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott BL, Van Komen JS, Irshad H, Liu S, Wilson KA, McNew JA. Sec1p directly stimulates SNARE-mediated membrane fusion in vitro. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:75–85. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200405018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungermann C, von Mollard GF, Jensen ON, Margolis N, Stevens TH, Wickner W. Three v-SNAREs and two t-SNAREs, present in a pentameric cis-SNARE complex on isolated vacuoles, are essential for homotypic fusion. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:1435–1442. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.7.1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Meer G, Voelker DR, Feigenson GW. Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:112–124. doi: 10.1038/nrm2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidberg H, Shpilka T, Shvets E, Abada A, Shimron F, Elazar Z. LC3 and GATE-16 N termini mediate membrane fusion processes required for autophagosome biogenesis. Dev Cell. 2011;20:444–454. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z, Nair U, Klionsky DJ. Atg8 controls phagophore expansion during autophagosome formation. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:3290–3298. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-12-1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen W-L, Shintani T, Nair U, Cao Y, Richardson BC, Li Z, Hughson FM, Baba M, Klionsky DJ. The conserved oligomeric Golgi complex is involved in double-membrane vesicle formation during autophagy. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:101–114. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200904075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.