Abstract

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has become the gold standard for imaging neurological tissues including the spinal cord. The use of MRI for imaging in the acute management of patients with spinal cord injury has increased significantly. This paper used a vigorous literature review with Downs and Black scoring, followed by a Delphi vote on the main conclusions. MRI is strongly recommended for the prognostication of acute spinal cord injury. The sagittal T2 sequence was particularly found to be of value. Four prognostication patterns were found to be predictive of neurological outcome (normal, single-level edema, multi-level edema, and mixed hemorrhage and edema). It is recommended that MRI be used to direct clinical decision making. MRI has a role in clearance, the ruling out of injury, of the cervical spine in the obtunded patient only if there is abnormality of the neurological exam. Patients with cervical spinal cord injuries have an increased risk of vertebral artery injuries but the literature does not allow for recommendation of magnetic resonance angiography as part of the routine protocol. Finally, time repetition (TR) and time echo (TE) values used to evaluate patients with acute spinal cord injury vary significantly. All publications with MRI should specify the TR and TE values used.

Key words: magnetic resonance imaging, MRI sequences, prognostication, spinal cord injury

Introduction

Before the advent of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), imaging of the injured spinal cord was indirect and limited. MRI allows better visualization of the spinal cord, ligaments, discs, vessels, and others soft tissues than computerized tomography (CT) scans or radiographs. Different MRI sequences have been developed to visualize optimally various aspects of the injured spine and spinal cord.

Kulkarni and associates (1988) were the first to characterize three MRI signal patterns for the prognostication of acute spinal cord injury (SCI): (1) hemorrhage in the cord; (2) edema of the cord; and (3) a combination of hemorrhage and edema. Prognostication patterns used today are variations of these original patterns.

MRI evaluation of anatomic structures can help determine the cause and extent of the neurological deficit, the probable mechanism of injury, and the presence of spinal instability (Provenzale, 2007).

The main reason that limits why MRI is not used frequently in trauma is the logistics of patient transport and monitoring (Sliker et al., 2005). Clinicians are also confronted with a multitude of available MRI sequences. Adequate selection of MRI sequences for diagnosis and prognostication can simplify imaging while limiting costs.

It is therefore imperative that the literature be reviewed to guide clinicians regarding the utility of MRI in acute care settings.

The purpose of this review was to answer three specific questions: (1) What is the recommended protocol for MRI in acute spinal cord injury? (2) Does MRI affect the initial management? (3) Does MRI predict a patient's long-term neurological outcome?

Methods

Article assessment

We systematically reviewed the literature on MRI for SCI between 1988 and 2009. We conducted an initial systematic search using multiple databases (Ovid Medline, PubMed, and EMBASE). The keywords were: “MRI” or “magnetic resonance imaging” (and any variant endings), combined with “SCI,” “spinal cord injury,” or “spinal cord trauma” (and any variant endings). The search was limited to human subjects and articles published in English.

The total number of references from all databases was 1090. Two investigators independently reviewed both the title of the citation and the abstracts of all references to determine their eligibility for inclusion. Case-report studies of one or two patients were excluded. Publications that used a magnet strength of less than 1.5 Tesla, as well as those on chronic stages of spinal cord injury, were excluded. From the initial pool of 1090 references, 158 publications were selected; 75 were reviews and only 83 were original papers.

After reading the 83 original articles, a further 30 original articles were obtained from references. These were included due to their quality and relevance, thus bringing the total of original papers to 113. Of these 30 new papers, 19 were published between 1988 and 1996, while the remaining 11 were published between 1997 and 2009.

There were no randomized control trials in the entire group of publications. Each article's level of evidence was classified according to Straus and associates (2005). The methodological quality of the selected publications was assessed using the Downs and Black (1998) scoring system based on 27 questions. The maximum possible score is 44. Each publication was scored twice. One reviewer rated all 113 papers, and two other reviewers rated 56 or 57 papers each, divided randomly. Every study rated differently between two investigators was reviewed to reach a consensus score.

Statistical analysis

Data was extracted into spreadsheet tables and analyzed with JMPstat (version 8.0; SAS, Carey, NC). Demographics, study design, MRI protocols, outcome measures, and results were recorded with a particular focus on quantifiable data. Means, mode, and standard deviations are presented in the tables. Downs and Black (DB) scores were compared with analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests and the Student's t test for each topic. The ANOVA and Student's t test were also used to compare the number of MRI sequences between categories of studies.

Delphi process

After completing the analysis, our results were presented to a group of seven clinicians from across Canada familiar with spinal cord injury. In order to formulate recommendations, this group evaluated the strength of the data supporting our answers to the three questions representing the goals of our research.

Results

These 113 articles were divided into seven topics: prognostication (n = 24), spinal cord injury without radiological abnormality (SCIWORA, n = 9), vertebral artery injury (VAI, n = 8), spinal clearance (n = 15), soft tissue injury (n = 12), other specific topics (n = 27), and descriptive MRI findings (n = 18). The category called “Others” included 15 different topics. The papers are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Papers

| Topic | Year of publication ± SD | Country (US/total) | # Patients/age (years) | # MRI sequences | Time to MRI (hours) | Downs and Black Score (±SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prognostication | 1999 ± 1.3 | 14/24 (58%) | 59 ± 10/35 ± 3 | 3.3 ± 0.3 | 79 ± 12 | 21.7 ± 4.1 |

| SCIWORA | 2003 ± 1.3 | 3/9 (33%) | 56 ± 24/38 ± 8 | 3.8 ± 0.7 | 66 ± 21 | 21.6 ± 3.8 |

| Vertebral artery injury | 2002 ± 1.5 | 2/8 (25%) | 118 ± 74/41 ± 6 | 4.0 ± 0.8 | 42 ± 9 | 20.8 ± 3.8 |

| Clearance | 2005 ± 1.0 | 11/15 (73%) | 570 ± 249/35 ± 4.5 | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 147 ± 40 | 19.8 ± 2.3 |

| Soft tissue injury | 2000 ± 1.4 | 11/12 (92%) | 53 ± 12/35 ± 3 | 3.5 ± 0.4 | 106 ± 41 | 19.5 ± 3.3 |

| Others | 2001 ± 1.1 | 15/27 (52%) | 24 ± 6/38 ± 4 | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 64 ± 11 | 18.9 ± 4.7 |

| Descriptive | 2000 ± 1.5 | 9/18 (50%) | 64 ± 18/39 ± 3 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 122 ± 32 | 16.5 ± 3.4 |

SCIWORA, spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormality.

A high proportion of articles dealing with soft-tissue injuries were written by authors from the United States, while some topics, such as VAIs, were published in many countries. Clearance papers and VAI papers had larger subject pools due to their screening purpose. Clearance papers had the highest number of MRI sequences performed. A Student's t test showed a significant difference (p = 0.038) in the number of MRI sequences performed between clearance and descriptive papers. An ANOVA test showed no significant difference (p = 0.35) between all categories of papers for the number of sequences. There was also no significant difference in time to perform MRI after injury between all topics (p = 0.26).

There was a significant difference in DB scores between categories (p = 0.0001). Descriptive articles had a significantly lower score than all other article categories when analyzed with the Student's t test (p < 0.02). The most significant difference was between prognostication papers (21.7/44) and descriptive papers (16.5/44) (p < 0.0001). The category of others is a heterogeneous category and therefore was not included in the statistics.

All articles had a level of evidence of four (case series) as rated by Straus and associates (2005).

Prognostication

A good estimate of the short- and long-term neurological prognosis is important for the patient, the family, the health care team, and the physician.

In the literature, sagittal T2 sequences had the highest correlation with patient prognosis (Andreoli et al., 2005; Ramon et al., 1997; Shimada and Tokioka, 1999). T2-weighted sequences can identify and measure the extent of both edema and hemorrhage within the spinal cord. Edema is seen on T2 MRI sequences as a hyperintensity of the signal within the cord. Hemorrhage is seen on T2 MRI as hypointensity. Hemorrhage is almost always present concurrently with edema (Flanders et al., 1999), and on an MRI it is surrounded by a hyperintensity normally associated with edema.

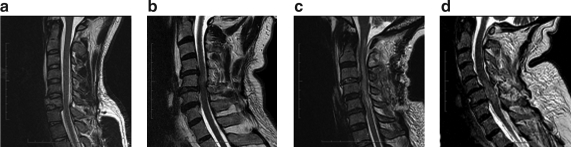

Presently, four signal patterns based on sagittal T2-weighted sequences are commonly used in the literature (Table 2). Bondurant and associates (1990) described this classification in 1990 as a modification of Kulkarni and associates' (1988) classification. Pattern 1 shows a normal MRI signal in the cord; pattern 2 represents single-level edema; pattern 3 is multi-level edema; and pattern 4 is mixed hemorrhage and edema (Fig. 1). Neither T1 sequences nor T2 axial images have been shown to have prognostic value. More recent sequences, such as gradient echo images (GRE), which are the best for visualizing hemorrhage, have not yet been incorporated into classification systems.

Table 2.

Summary of Select Prognostication Papers

| Year, Authors | # Patients/age (years) | Cervical spine | Time to MRI (hours) | ASIA A at admission | Normal cord | Single-level edema | Diffuse edema | Hemorrhagic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005, Andreoli et al. | 38/38 | 100% | 8 | 16/38 (42%) | 0 | 10/38 (26%) | 16/38 (42%) | 12/38 (32%) |

| 1999, Shimada and Tokioka | 75/55 | 100% | <48 | 22/75 (29%) | 10 (13%) | 25/75 (33%) | 30/75 (40%) | 10/75 (13%) |

| 1997, Ramon et al. | 55/32 | 18/55 (33%) | 192 | 28/55 (51%) | 4/55 (7%) | NSt | NSt | 14/55 (25%) |

| 1990, Bondurant et al. | 37/30 | 21/37 (57%) | 115 | 16/37 (43%) | 8/37 (22%) | 16/37 (43%) | 3/37 (8%) | 10/37 (27%) |

| Total | 205/40 | 152/205 (74%) | N/A | 82/205 (40%) | 22/205 (11%) | 51/150 (34%) | 49/150 (33%) | 46/205 (22%) |

FIG. 1.

Four injury signal patterns using Sagittal T2 MRI. (a) Burst fracture of C6 and retrolisthesis of C6 on C7 by 4 mm with normal cord (pattern 1). (b) Single-level edema severe central stenosis C5–6 and C5 fracture (pattern 2). (c) Multi-level edema C1 to C5 with C3–C4 disk herniation (pattern 3). (d) Hemorrhage and surrounding edema centered at C6 (pattern 4) in patient with bilateral C5 lamina fractures, inferior facet fractures, and grade 1 anterolisthesis of C5 on C6.

Only four prognostication studies classified patients by both MRI signal patterns and improvement on neurological exam (American Spinal Injury Association [ASIA]/Frankel). Of a total of 205 patients from these studies, 11% had a normal spinal cord, 34% had single-level edema, 33% had diffuse edema, and 22% had hemorrhage. Eighty-two patients were ASIA A at admission (40%). Ramon and associates (1997) reported 15 patients (27%) where the edema was not differentiated between single and multiple levels. They also had an additional classification group called contusion (central isointensity and thick peripheral hyperintensity ring) that could probably be included in the edema group. It is worth noting that the time to the initial MRI varied greatly, perhaps altering the MRI signal pattern found in the patients.

Figure 2 summarizes graphically the degree of neurological improvement as measured by ASIA/Frankel (Andreoli et al., 2005; Ramon et al., 1997; Shimada and Tokioka, 1999). Regardless of their initial neurological status, all patients with a normal cord on MRI recovered fully to ASIA E. The most severe neurological outcomes are associated with hemorrhagic pattern. Of all patients presenting with ASIA A, 43/66 (65%) had a hemorrhagic pattern (Fig. 2). Of these, 41 (95%) remained ASIA A at follow up. The remaining two patients (5%) improved by one grade to ASIA B. Conversely, patients with single-level or diffuse edema showed improvements in ASIA grade. For single-level edema, the average improvement was 1.9 ASIA grades, excluding the five patients initially ASIA E, and all patients initially ASIA D improved fully to ASIA E. Patients with diffuse edema showed an average improvement of 0.9 grades. However, 13/18 (72%) patients with diffuse edema who were initially ASIA A did not improve.

FIG. 2.

Change of neurological status by sagittal T2-weighted MRI patterns.

Many positive correlations were described within the prognostication articles. Hemorrhage (p = 0.002), higher rostro-caudal edema (p = 0.036), lesion length (p = 0.005), greater degree of cord compression (p = 0.002), greater degree of canal compromise (p = 0.005), and the severity of soft tissue injuries (p = 0.03) were all associated with poorer neurological outcomes (Dai and Jia, 2000; Flanders et al., 1996; Miyanji et al., 2007; Selden et al., 1999; Song et al., 2008). In contrast, Selden and associates (1999) found no correlation between neurological outcome and the length of intramedullary hemorrhage or the length of spinal cord swelling.

MRI sequences

Out of the 113 original papers using a magnet strength of 1.5 Tesla, 91 (81%) described their MRI protocol. On average, 3.5 sequences were used (mode 4.0, range 1–7). Sagittal T2-weighted images and sagittal T1-weighted images were acquired 100% and 93% of the time respectively. Sagittal GRE images were used in 15% of papers only. Axial T2, axial T1, and GRE were used 37, 35, and 20% of the time respectively.

There was a great variability in repetition time (TR) and echo time (TE) amongst papers. For sagittal T2-weighted images, the modal TR and TE values were 2000 msec and 80 msec respectively. The modal TR was used by 13/34 (38%) of authors (mean 2525 ± 176, range 1500–4800). The modal TE was used by 7/33 (21%) of authors (mean 76 ± 6.4, range 15–150).

For sagittal T1-weighted images and sagittal GRE, the modal TR/TE values were quite similar: 600/20 and 636/15 msec respectively (Table 3). The distribution for sagittal T1 TR values is almost bimodal, however: while 38% used a TR of 600 msec, 27% of authors reported using a TR of 500 msec.

Table 3.

TR and TE Values for Different MRI Sequences

| Sequence | Modal TR (msec) | Percent of authors | Modal TE (msec) | Percent of authors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sag T2 | 2000 | 24% | 80 | 17% |

| Sag T1 | 600 | 38% | 20 | 26% |

| Sag GRE | 636 | 28% | 15 | 43% |

| Axial T2 | 2000 | 23% | 80 | 31% |

| Axial T1 | 600 | 31% | 15 | 20% |

| Axial GRE | 500 | 20% | 15 | 30% |

Other MRI sequences used include short-tau inversion recovery (STIR) and gradient recall acquisition steady state (GRASS). STIR and GRASS sequences were used by 11/114 (10%) and 4/114 (4%) of authors respectively. The STIR sequence was significantly more likely to be used in clearance articles (4/15, 27%, p = 0.0458), while the GRASS sequence was not significantly associated with any topic (p = 0.28). In papers whose primary purpose was to assess ligamentous injury (n = 12), no authors used STIR sequences while one performed GRASS sequences. Authors did not report that these sequences yielded additional information leading to changes in patient care. One author concluded that Gadolinium MRI is not useful for early evaluation, since the enhancement is visible only 1 week post injury (Terae et al., 1997).

Thirty-nine authors also specified the MRI machine brand used: GE (n = 24), Siemens (n = 10), Philips (n = 4), and Toshiba (n = 1). The 1.5 T GE MRI machines were used in 15/42 (36%) of publications from North American authors. The 1.5 T Siemens MRI machines were used by 100% (5/5) of German authors. We found no significant difference in number of MRI sequences performed between authors using either GE or Siemens machines (p = 0.812).

Diffusion-weighted MR did not yield significant additional prognostic information (Shen et al., 2007; Tsuchiya et al., 2006). The diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) studied in 20 patients reflecting the severity of cord injury was not studied with respect to neurological outcome (Shanmuganathan et al., 2008).

MRI for non-spinal cord structures

Vertebral artery injury

The rationale for early detection of a VAI would be to prevent its ischemic and/or hemorrhagic complications by offering an appropriate treatment.

The eight studies included a total of 942 patients (Table 4). Patients included in these studies were considered to be at high risk of a VAI due to the mechanism of trauma and/or their bony or spinal cord pathology. A unilateral VAI was found in 140 patients (15%), and another seven (0.7%) had bilateral occlusions.

Table 4.

Summary of Papers Using MRI/MRA To Detect Vertebral Artery Injury

| Year, Author | Tesla technique TR/TE | # of patients (age) | Total VAI (MRA) | Bilateral Injury (MRA) | Total VAI (DSA) | Neurological manifestations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007, Yokota et al. | NSt MRI only | 36 (35) | 11/36 (31%) | 0/11 | (13/26) 50% | 2 cerebellar/brainstem infarct/no death |

| 2005b, Torina et al. | 1.5 2D TOF 40/8.7 | 632 (NSt) | 83/632 (13%) | 4/83 (5%) | N/A | NSt |

| 2005, Taneichi et al. | 1.5 2D TOF 27/9 | 64 (52) | 11/64 (17%) | 1/11 (9%) | N/A | 1 transient blurred vision (bilateral) |

| 2002, Kral et al. | NSt | 7 (NA) | 1/7 (14%) | 0/7 | 2/7 (28%) | NSt |

| 2001, Parbhoo et al. | 1.5 2D TOF NSt | 47 (35) | 12/47 (26%) | 1/12 (8%) | N/A | 0 |

| 2000, Veras et al. | 1.5 2D TOF 45/8.7 | 59 (NSt) | 8/59 6 occl (14%) | 0/8 | N/A | 1 locked-in 1 transient blurred vision |

| 1997, Giacobetti et al. | 1.5 NSt | 61 (40) | 12/61 (20%) | 0/12 | N/A | 3 transient symptoms |

| 1995b, Friedman | 1.5 2D TOF 40/8.7 | 37 (42) | 9/37 (24%) | 1/9 (11%) | N/A | 1 death (bilateral injury) |

| Total | 942 | 147/942 (16%) | 7/147 VAI (5%) 7/943 screened patients (.7%) | 15/33 (45%) | 9/63 VAI (14%) 9/304 screened patients (3%) |

DSA, digital subtraction angiography; N/A, not applicable; NSt, not stated.

The type of VAI was described in 151 cases (Friedman et al., 1995; Kral et al., 2002; Parbhoo et al., 2001; Veras et al., 2000): occlusion (n = 133, 88%), stenosis (n = 8, 5%), intimal irregularities or flap (n = 5, 3%), dissection (n = 4, 3%), and vertebral artery displacement (n = 1, 1%). Whenever there was a discontinuation in vertebral artery flow, it was diagnosed as an occlusion.

The laterality of the injury was described in 41 cases (Taneichi et al., 2005; Torina et al., 2005b; Veras et al., 2000). There was a slight preponderance of right VAI (n = 23, 56%) compared to the left (n = 18, 44%).

The presence or absence of neurological manifestations related to VAI was reported in 63 patients. Nine patients (14%) had neurological manifestations related to their VAI, with four (1%) patients having poor outcomes. The single patient who died had a bilateral VAI, but the one patient with locked-in syndrome had a unilateral injury. Of the two other patients with a bilateral VAI and a description of symptoms, one had transient blurred vision, while the other was normal.

The ASIA/Frankel score was reported in 139/942 (15%) patients undergoing magnetic resonance angiography (MRA). Spinal cord injury was found in 91/139 (65%) patients: ASIA A = 45, ASIA B = 13, ASIA C = 17, ASIA D = 12, and ASIA E = 4. Two papers found a positive correlation between the severity of the ASIA score and the incidence of VAI (p < 0.02) (Friedman et al., 1995; Torina et al., 2005a, 2005b).

One study found that unilateral facet dislocation was significantly more likely if vertebral artery occlusion occurred (p = 0.02) (Taneichi et al., 2005), and another trended toward the same conclusion (p = 0.19) (Vaccaro et al., 1998). Furthermore, foramen transversarium fractures were not found to be statistically correlated with vertebral artery occlusion (Taneichi et al., 2005).

Ligaments

Determination of the integrity of the ligaments will help to categorize an injury as stable or unstable. This knowledge can help direct initial management.

The sensitivity of MRI in detecting soft tissue injuries varies between authors: ALL: 46–71%, Disk 93%, posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL) 43–93%, ligamentum flavum (LF) 67%, interspinous ligament (ISL) 36–100%, supraspinous ligament (SSL) 89% (Emery et al., 1989; Goradia et al., 2007; Haba et al., 2003; Katzberg et al., 1999; Keiper et al., 1998; Kliewer et al., 1993).

In a series of 81 patients with extension injury, it was found that the severity of PLL injury, rather than ALL injury, was correlated more with greater spinal cord injury (Song et al., 2008) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Summary of Papers Using MRI To Detect Soft Tissue Injury

| Year, Author | # of patients/age (years) | Injuries on MRI/total injuries | Injuries CT | Radiography ligamentous | Sensitivity/specificity (gold standard) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007, Goradia et al. | 31/NSt | NSt | N/A | N/A | ISL = 100%/NSt |

| PLL = 93%/NSt | |||||

| ALL = 71%/NSt | |||||

| LF = 67%/NSt | |||||

| Disc = 93%/NSt(surgery) | |||||

| 2003, Haba et al. | 35/37 | NSt | N/A | N/A | SSL = 89.4%/92.3% |

| ISL = 98.5%/87.2% (surgery) | |||||

| 1999, Katzberg et al. | 199/38 | 136/172 (79%) | NSt | 38/172 (23%) | PLL = 43%/NSt |

| ALL = 46%/NSt | |||||

| ISL = 36%/NSt (combined MRI/CT/radiography) | |||||

| 1998, Keiper et al. | 52/NSt | 16/52 (31%) | 6/6 suspicious patients | 17/48 | NSt |

| 1993, Kliewer et al. | 28/NSt | 41/52 (79%) | N/A | N/A | 79%/NSt (post-mortem) |

| 1987, Emery et al. | 37/33 | 17/37 | N/A | N/A | 90%/100% (surgery) |

N/A, not applicable; NSt, not stated.

Bone

The integrity of the bony structures is usually assessed by plain x-rays and a CT scan. However, some papers measured the utility of MRI in detecting bony injuries (Table 6).

Table 6.

Summary of Papers Using MRI To Detect Bony Structure Integrity

| Year, Author | # Patients/age | Structure | Gold standard | Radiograph sensitivity/specificity | MRI sensitivity/specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007, Goradia et al. | 31/NSt | (1)Vertebral body | Surgery | N/A | (1) 100%/NSt |

| (2) Posterior bony elements | (2) 45%/NSt | ||||

| 1999, Katzber et al. | 199/38 | (1) Vertebral body fracture | Combined MRI, CT and X-ray | (1) 48%/NSt | (1) 43%/NSt |

| (3) Facet subluxation | (3) 72%/NSt | (3) 59%/NSt | |||

| (4) Vertebral body subluxation | (4) 40%/NSt | (4) 45%/NSt | |||

| 1999, Klein et al. | 42/46 | (1) Vertebral body | CT scan | N/A | (1) 37%/98% |

| (2) Posterior bony elements | (2) 12%/97% | ||||

| 1998, Keiper et al. | 52/NSt | (1) Vertebral body | Cadavers | (1) 100%/100% | (1) 100%/100% |

| (2) Posterior bony elements | (2) 75%/100% | (2) 33%/90% | |||

| Range | (1) Vertebral body | (1) 48–100% | (1) 37–100%/98%–100% | ||

| (2) Posterior bony elements | (2) 12–45%/90–97% |

N/A, not applicable; NSt, not stated.

Four studies described the sensitivity and two described the specificity of MRI when comparing to CT-scan findings (n = 2), cadavers (n = 1), and surgical findings (n = 1).

The sensitivity of MRI for detecting a bony injury is better for the vertebral body (37–100%) than for posterior bony elements (12–45%) (Goradia et al., 2007; Keiper et al., 1998; Klein et al., 1999). MRI sensitivity for acute vertebral subluxation and acute facet subluxation were 45% and 59% respectively (Katzberg et al., 1999).

Disk

Within the series of articles describing patients with injuries to the cervical spine, there was high rate of disk herniation or injury (36%) on initial MRI. There was a higher proportion of posterior ligament complex (PLC) injuries compared to ALL injuries (64% vs. 37%). Labattaglia and associates (2007) reported that 18/134 (13%) of his patients had concurrent ligamentous injury but did not indicate the specific ligaments. The majority of authors did not state if the patients' neurological deficit could be attributed to the disk herniation (Table 7).

Table 7.

Summary of Papers Using MRI To Detect Disk Injury in C-Spine Patients

| Year, Author | # Patients/age | Pre-reduction hernia or disk injury | Concurrent ALL injury | Concurrent PLC injury |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008, Kasimatis et al. | 6/56 | 4/6 (67%) | NSt | 6/6 |

| 2007, Labattaglia et al. | 134/NSt | 27/134 (20%)** | NSt | NSt |

| 2007, Goradia et al. | 31/NSt | 15/31 (48%) | 14/31 (45%) | 15/31 (45%) |

| 2005, Shin et al. | 30/39 | 7/30 (23%) | NSt | 9/30 (30%) |

| 2004, Choi et al. | 7/NSt | 3/7 (43%) | 2/7 (28%) | 1/7 (14%) |

| 2002, Regnicolo et al. | 19/NSt | 17/19 (90%) | 19/19 (100%) | 19/19 (100%) |

| 2001, Vaccaro et al. | 48/NSt | 33/48 (69%) | 26/48 (54%) | 48/48 (100%) |

| 1999, Vaccaro et al. | 11/46 | 2/11 (18%) | 3/11 (27%) | 7/11 (65%) |

| 1998, Keiper et al. | 52/NSt | 3/52 (6%) | 2/52 (4%) | 13/52 (25%) |

| 1997, Leite et al. | 8/28 | 3/8 (38%) | NSt | NSt |

| 1996, Benzel et al. | 62/35 | 27/62 (44%)* | 20/62 (33%) | 52/62 (84%) |

| 1993, Hall et al. | 6/35 | 4/7 (57%) | NSt | 1/7 (14%) |

| 1988, Mirvis et al. | 21/43 | 11/21 (52%) | NSt | NSt |

| Total | 435 | 157/435 (36%) | 86/230 (37%) | 171/267 (64%) |

Benzel et al. (1996) is only disk injury.

Labattaglia et al. (2007) did not specify between hernias or disk injuries.

NSt, not stated.

Clearance

While the incidence of abnormal findings on MRI after a normal CT scan is 15%, most are described as clinically insignificant and only 3/989 (0.3%) patients had positive MRIs indicating the need for surgical management. In the 865 screened patients without neurological deficit, only one patient's surgical management was changed by a positive MRI (0.1%). In patients with a neurological deficit, 2/11 (18%) had their course of management changed.

The small number of significant findings and the lack of resulting changes in surgical management have led some authors to question the value of MRI as a part of standard clearance protocol (Como et al., 2007; Schuster et al., 2005; Vaccaro et al., 1998). However, Labattaglia and associates (2007) suggest that MRI can change the non-operative management at discharge: patients were more likely to be discharged with a cervical collar if they had an abnormal MRI (p < 0.0001).

Discussion and Recommendations

The DB scoring only awards full marks to randomized control studies. While there are no RCTs in our series, the articles earning higher DB score share some similar properties. The highest scoring articles tend to have clearly described and non-selected patient populations, follow ups, and meaningful statistics with reported p values. Prognostication papers rated highest overall because they included these factors.

Prognostication

Emerging from the literature were four signal patterns on sagittal T2 images, which can describe nearly the entire spectrum of spinal cord injuries. They are: normal cord, single-level edema, multi-level edema, and mixed hemorrhage and edema (Andreoli et al., 2005; Bondurant et al., 1990; Ramon et al., 1997; Shimada and Tokioka, 1999). Complete cord transections and penetrating injuries do not fall within this classification due to their different and easily differentiated patterns on MRI. Those injuries are also associated with quite different prognoses. No prognosticative signal patterns were established on axial images. This is possibly due to insufficient definition of the spinal cord on axial images. The correlation of these four patterns with final neurological status has been done in studies comprising a total of 205 patients.

Patients with single-level edema had better initial neurological status than patients with diffuse edema. Single-level edema patients showed an improvement of about two grades in ASIA score compared to an improvement of one grade for patients with diffuse edema. Furthermore, 10/46 (22%) of single-level edema patients with initial neurological deficit recovered to ASIA E compared to only 1/49 (2%) of patients with diffuse edema. The prognosis of patients with edema is significantly better than for those with hemorrhage. Patients with hemorrhage are initially ASIA A about 95% of the time and improved one ASIA grade about 5% of the time.

Evidence in the literature supports the expectation that more severe abnormalities on MRI are associated with a more severe neurological status. In particular, hemorrhage, the number of levels of edema, greater degree of cord compression, greater degree of canal compromise, and severity of soft tissue injury were shown to be associated with a worse neurological outcome (Dai and Jia, 2000; Flanders et al., 1996; Miyanji et al., 2007; Selden et al., 1999; Song et al., 2008). Interestingly, the length of hemorrhage is not correlated with the severity of injury. Single-level hemorrhage alone often indicates a complete lesion (ASIA A).

Animal studies have shown that all injuries may have some amount of hemorrhage not necessarily detected on imaging (Nout et al., 2009). We have to accept that the four-pattern classification cannot represent the full continuum of acute spinal cord injuries.

It has been recommended that the first MRI be performed 24–72 h post trauma (Bondurant et al., 1990). There was no evidence supporting a more precise guideline. However, an important consideration is that the length of edema on T2-weighted sagittal MRI is proportional to the time of imaging after the trauma (Leypold et al., 2007). Within the first 5 days post injury, each 1.2-day delay to MRI increased the length of edema by one vertebral level (Leypold et al., 2007). Future research could focus on defining the best time for both first and second prognostic MRIs, as well as defining the progression of edema.

It has been shown that while single-level edema will resolve by 3 weeks, the signal from multi-level edema will persist beyond this time (Shimada and Tokioka, 1999). Future studies could assess if the speed of the resolution of edematous signal is associated with patient prognosis. Similarly, the initial hypointensity of signal associated with hemorrhage has been shown to change into a hyperintensity of signal at 2 weeks (Shimada and Tokioka, 1999). There are considerable variations in the improvement of patients with either single or multi-level edema. Use of other sequences may shed light on the variable outcomes seen within these categories.

MRI sequences

Authors described the MRI sequences used in 70% of the articles. However, the respective TR/TE values were only described in 40% of articles. Typically reported TR/TE values for sagittal T2 images were 2000 msec and 80 msec respectively. The T1 uses a TR of 600 msec and TE of 15–20 msec. The GRE uses similar TR and TE values of 636 msec and 15 msec respectively. However, as these modal values are only used by approximately 25% of authors, establishing guidelines is difficult. All future authors should describe their actual TR and TE values in order to accumulate the amount of data required to begin standardizing MRI techniques worldwide.

Sagittal T2 images are the only sequences shown to have prognostic value. As the presence of hemorrhage is the most important factor tied to final neurological status, we recommend with reserve the inclusion of the sagittal GRE sequence. Use of the GRE sequence is debated, as it is very sensitive to motion, especially with breathing. It might miss smaller amount of blood or hemosiderin (Gillams et al., 1997; Katz et al., 1989).

Axial T2 sequences were not found to be of use in prognostication but do have value in identifying clinically relevant lesions such as disk herniation and spinal cord compression that may alter management.

Other sequences were of neither prognostic value nor significant contributors to changes in patient management. The use of these sequences should be at the discretion of the treating team (Miranda et al., 2007).

The recommended protocol seeks to be both sufficiently informative yet not time-consuming. Limiting the required sequences facilitates the goal of allowing clinicians access to MRI at all times. It reduces the time needed to perform the exams in patients who can be medically unstable. Using a standardized protocol simplifies the work of MRI technicians working in emergency settings (Table 8).

Table 8.

MRI Sequences Recommendation

| Sequences | Visualization | Rationale | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recommended sequences | Sagittal T2 | Cord compression, edema, hemorrhage | Management, prognostication |

| Sagittal GRE | Cord hemorrhage | Prognostication | |

| Axial T2 | Disc herniation, cord compression | Management | |

| Optional sequences | Sagittal and axial T1 | Ligaments, cysts | Mechanism of injury |

| Axial GRE | Hemorrhage | ||

| STIR/GRASS | lLgaments | ||

| MRA | VAI | ||

| DTI | White matter tracts | Investigational |

Soft tissue injury

A limited series of articles exists that describe the sensitivity and specificity of MRI in identifying soft tissue injuries in the subset of patients with spinal cord injuries. Our search was limited to patients with spinal cord injury, and therefore our conclusions apply to this subset of patients.

The more recent literature tended to report sensitivity values of about 95% for ligamentous structures posterior to the vertebral bodies compared to about 71% for the ALL. While both the ALL and PLL adhere to the disk, only the ALL's inner layer adheres to the vertebra (Grenier et al., 1989) The PLL is therefore looser and may be easier to identify.

Some MRI sequences have been specialized for the imaging of ligaments. One study not focusing on spinal cord injury found a high correlation of STIR (fat-suppressed T2 images) with operative findings (p = 0.0001) (Lee et al., 2000). However, not enough evidence exists in our literature search to support the routine use of STIR or GRASS sequences in assessing the integrity of soft tissue structures.

Comparing MRI results to intra-operative findings can inflate the MRI sensitivity, as only injuries known to require fixation would be taken to the operating room. Possibly, subtler ligamentous injuries would have a lower rate of detection, although failure to recognize them might not have clinical consequences.

Bony injury

The sensitivity of MRI for detecting bony injury is better for the vertebral body than for posterior bony elements due to the lesser amount of cancellous bone in the laminae (Klein et al., 1999). Fractures are seen as a zone of edema on T2 images. While the sensitivity of MRI for bony injury remains too low to replace the CT-scan, its specificity is reported at around 95%.

Disk

We found a high rate of disk herniation or injury in the population of patients with cervical spine injuries (36%). There was also a high rate of concomitant injuries to the ligaments posterior to vertebral body (PLC) and the anterior longitudinal ligament (ALL), 64% and 37% respectively. It is likely that the disks and the ligamentous structures should be evaluated with MRI preferentially in patients with neurological deficits, although the lack of association of these injuries with patient neurological status prevents the formulation of specific guidelines.

Vertebral artery injuries

The true incidence of VAI in spinal cord injury patients is unknown. Most studies had a bias in their recruitment (only high risk patients included) and some studies included only arterial occlusion, as discontinuation of flow is the easiest type of abnormality seen on MRA.

To detect a VAI, 2D time-of-flight was the most commonly used sequence and is thought to be superior to 3D due to fewer false positives from no signal drop-out in small arteries (Veras et al., 2000). It allows good visualization of the V2 segment; the V3 segment may have flow-related artifact and the visualization of V1 and V4 is variable.

The overall rate of VAI was 16% including 0.7% bilateral injuries. The neurological consequences of unilateral or bilateral injuries are rare but can be severe, especially in cases with bilateral occlusion. Our literature review yielded only four lasting and serious complications arising from 943 cases of high-risk patients. Therefore, the necessity of performing MRA for general screening purposes is questioned.

Clearance

Ample evidence exists in the literature in support of MRI free protocols used for clearing the cervical spine in patients who are awake and have no distracting injuries (injuries from which pain may mask pain from cervical injuries) (Patton et al., 2000). However, there remains clinical equipoise on how best to treat obtunded patients. Many authors maintain that a CT scan alone can be enough to clear obtunded patients (Como et al., 2007; Schuster et al., 2005; Vaccaro et al., 1998). Yet some authors believe in the constitutive use of MRI (Ghanta et al., 2002).

Following our review, 15% of injuries seen on MRI were missed on CT scans. Only a minor proportion of obtunded patients without neurological deficits and abnormal MRI findings missed on a CT scan merited surgical attention (0.1%). However, a larger proportion of obtunded patients (18%) with neurological deficit (≤ASIA D) and abnormal MRI but clean CT scans had surgical interventions. We therefore only recommend the use of MRI for clearance of obtunded patients in the subset having neurological impairment in the extremities.

Future applications

Imaging technology is rapidly evolving. Four main fields of research emerged from our review: the development of new MRI techniques to visualize better spinal cord lesions, the tracking of transplanted cells, the visualization of an eventual repair, and the detection of adverse effects of therapy.

The 1.5 Tesla MRI has limited capacity to detect subtle volume changes in the cord after transplantation (Feron et al., 2005a, 2005b). Stronger magnets could better define the lesions. One study performed on rats describes the use of 11.7 Tesla MRI (Lepore et al., 2006).

DTI is gaining in popularity due to its unique ability to track white-matter disease and changes. One study using DTI in 20 patients with spinal cord injury showed a correlation between abnormality in DTI parameters and severity of cervical cord injury. However, standard DTI remains limited for the spinal cord due to its small diameter, cord motion artifacts due to breathing, and its close relationship to the spine bony structures (Clark and Werring, 2002). One recent study describes a new technique to improve the resolution of diffusion tensor imaging of the spinal cord, thus allowing for detection of abnormalities not seen on regular MRI (Ellingson et al., 2006).

New MRI sequences such as fast imaging employing steady state acquisition (FIESTA) or spoiled gradient recalled (SPGR; has gradient echo properties) have signals free of artifacts due to products of degradation of hemoglobin (Dunn et al., 2005).

Some clinical trials have employed MRI in visualizing the effects of therapy. One study looked at the effects of olfactory mucosa transplantation into the spinal cord lesion (Lima et al., 2006). MRI done at 6 months showed filling of the lesion site. MRI was also used to rule out any neoplastic growth (Feron et al., 2005b). A larger clinical trial involving 35 complete and acute spinal cord injury patients looked at bone marrow cell transplant after 4 months and showed some increase in the spinal cord volume in 42.9% of the patients, while 33.3% showed atrophic changes (Yoon et al., 2007).

Conclusion and Recommendations

Following the Delphi discussion and voting process, these three key statements were unanimously accepted:

1. It is weakly recommended, based on weak evidence, that MRI be done in all patients with acute SCI, when feasible, to direct management.

2. It is strongly recommended, based on moderate evidence, that an MRI be done in the acute period following a spinal cord injury for prognostication.

3. It is strongly recommended, based on moderate evidence, that the sagittal T2 MRI sequence be included in all MRI protocols to prognosticate neurological outcome in the acute SCI setting.

Based on the literature, the exact time to perform an MRI within the acute period cannot be determined. However, authors most often performed MRI within the first 72 h post injury. Sequences other than sagittal T2 were not found to be useful for prognosticative purposes. Rapidly improving software and the increasing magnet strength may render other sequences more useful for prognostication in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Maria Cortes, MD, neuroradiologist, for reviewing the article and Ioli Makriyianni for project coordination.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Andreoli C. Colaiacomo M.C. Rojas Beccaglia M. Di Biasi C. Casciani E. Gualdi G. MRI in the acute phase of spinal cord traumatic lesions: Relationship between MRI findings and neurological outcome. Radiol. Med. 2005;110:636–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondurant F.J. Cotler H.B. Kulkarni M.V. Mcardle C.B. Harris J.H., Jr. Acute spinal cord injury. A study using physical examination and magnetic resonance imaging. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1990;15:161–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark C.A. Werring D.J. Diffusion tensor imaging in spinal cord: Methods and applications – A review. NMR Biomed. 2002;15:578–586. doi: 10.1002/nbm.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Como J.J. Thompson M.A. Anderson J.S. Shah R.R. Claridge J.A. Yowler C.J. Malangoni M.A. Is magnetic resonance imaging essential in clearing the cervical spine in obtunded patients with blunt trauma? J. Trauma. 2007;63:544–549. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31812e51ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai L. Jia L. Central cord injury complicating acute cervical disc herniation in trauma. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:331–335. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200002010-00012. discussion, 336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs S.H. Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 1998;52:377–384. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn E.A. Weaver L.C. Dekaban G.A. Foster P.J. Cellular imaging of inflammation after experimental spinal cord injury. Mol Imaging. 2005;4:53–62. doi: 10.1162/15353500200504175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellingson B.M. Ulmer J.L. Schmit B.D. A new technique for imaging the human spinal cord in vivo. Biomed. Sci. Instrum. 2006;42:255–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery S.E. Pathria M.N. Wilber R.G. Masaryk T. Bohlman H.H. Magnetic resonance imaging of posttraumatic spinal ligament injury. J. Spinal Disord. 1989;2:229–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feron F. Perry C. Cochrane J. Licina P. Nowitzke A. Urquhart S. Geraghty T. Kay-Sim A. Autologous olfactory ensheathing cell transplantation in human spinal cord injury. Brain. 2005a;128:12–60. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feron F. Perry C. Cochrane J. Licina P. Nowitzke A. Urquhart S. Geraghty T. Mackay-Sim A. Autologous olfactory ensheathing cell transplantation in human spinal cord injury. Brain. 2005b;128:2951–2960. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh657. [TITLE AS ABOVE – OKAY] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanders A.E. Spettell C.M. Friedman D.P. Marino R.J. Herbison G.J. The relationship between the functional abilities of patients with cervical spinal cord injury and the severity of damage revealed by MR imaging. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1999;20:926–934. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanders A.E. Spettell C.M. Tartaglino L.M. Friedman D.P. Herbison G.J. Forecasting motor recovery after cervical spinal cord injury: Value of MR imaging. Radiology. 1996;201:649–655. doi: 10.1148/radiology.201.3.8939210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman D. Flanders A. Thomas C. Millar W. Vertebral artery injury after acute cervical spine trauma: rate of occurrence as detected by MR angiography and assessment of clinical consequences. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1995;164:443–447. doi: 10.2214/ajr.164.2.7839986. discussion, 448–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanta M.K. Smith L.M. Polin R.S. Marr A.B. Spires W.V. An analysis of Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma practice guidelines for cervical spine evaluation in a series of patients with multiple imaging techniques. Am. Surg. 2002;68:563–567. discussion, 567–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillams A.R. Soto J.A. Carter A.P. Fast spin echo vs conventional spin echo in cervical spine imaging. Eur. Radiol. 1997;7:1211–1214. doi: 10.1007/s003300050276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goradia D. Linnau K.F. Cohen W.A. Mirza S. Hallam D.K. Blackmore C.C. Correlation of MR imaging findings with intraoperative findings after cervical spine trauma. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2007;28:209–215. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenier N. Greselle J.F. Vital J.M. Kien P. Baulny D. Broussin J. Senegas J. Caille J.M. Normal and disrupted lumbar longitudinal ligaments: Correlative MR and anatomic study. Radiology. 1989;171:197–205. doi: 10.1148/radiology.171.1.2928526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haba H. Taneichi H. Kotani Y. Terae S. Abe S. Yoshikawa H. Abumi K. Minami A. Kaneda K. Diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging for detecting posterior ligamentous complex injury associated with thoracic and lumbar fractures. J. Neurosurg. 2003;99:20–26. doi: 10.3171/spi.2003.99.1.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B.H. Quencer R.M. Hinks R.S. Comparison of gradient-recalled-echo and T2-weighted spin-echo pulse sequences in intramedullary spinal lesions. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1989;10:815–822. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzberg R.W. Benedetti P.F. Drake C.M. Ivanovic M. Levine R.A. Beatty C.S. Nemzek W.R. McFall R.A. Ontell F.K. Bishop D.M. Poirier V.C. Chong B.W. Acute cervical spine injuries: Prospective MR imaging assessment at a level 1 trauma center. Radiology. 1999;213:203–212. doi: 10.1148/radiology.213.1.r99oc40203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiper M.D. Zimmerman R.A. Bilaniuk L.T. MRI in the assessment of the supportive soft tissues of the cervical spine in acute trauma in children. Neuroradiology. 1998;40:359–363. doi: 10.1007/s002340050599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein G.R. Vaccaro A.R. Albert T.J. Schweitzer M. Deely D. Karasick D. Cotler J.M. Efficacy of magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of posterior cervical spine fractures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1999;24:771–774. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199904150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer M.A. Gray L. Paver J. Richardson W.D. Vogler J.B. McElhaney J.H. Myers B.S. Acute spinal ligament disruption: MR imaging with anatomic correlation. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 1993;3:855–861. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880030611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kral T. Schaller C. Urbach H. Schramm J. Vertebral artery injury after cervical spine trauma: A prospective study. Zentralbl. Neurochir. 2002;63:153–158. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-36433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni M.V. Bondurant F.J. Rose S.L. Narayana P.A. 1.5 tesla magnetic resonance imaging of acute spinal trauma. Radiographics. 1988;8:1059–1082. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.8.6.3205929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labattaglia M.P. Cameron P.A. Santamaria M. Varma D. Thomson K. Bailey M. Kossmann T. Clinical outcomes of magnetic resonance imaging in blunt cervical trauma. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2007;19:253–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2007.00960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.M. Kim H.S. Kim D.J. Suk K.S. Park J.O. Kim N.H. Reliability of magnetic resonance imaging in detecting posterior ligament complex injury in thoracolumbar spinal fractures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:2079–2084. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200008150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepore A.C. Walczak P. Rao M.S. Fischer I. Bulte J.W. MR imaging of lineage-restricted neural precursors following transplantation into the adult spinal cord. Exp. Neurol. 2006;201:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leypold B.G. Flanders A.E. Schwartz E.D. Burns A.S. The impact of methylprednisolone on lesion severity following spinal cord injury. Spine. 2007;32:373–378. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000253964.10701.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima C. Pratas-Vital J. Escada P. Hasse-Ferreira A. Capucho C. Peduzzi J.D. Olfactory mucosa autografts in human spinal cord injury: A pilot clinical study. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2006;29:191–203. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2006.11753874. discussion, 204–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda P. Gomez P. Alday R. Kaen A. Ramos A. Brown–Sequard syndrome after blunt cervical spine trauma: Clinical and radiological correlations. Eur. Spine J. 2007;16:1165–1170. doi: 10.1007/s00586-007-0345-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyanji F. Furlan J.C. Aarabi B. Arnold P.M. Fehlings M.G. Acute cervical traumatic spinal cord injury: MR imaging findings correlated with neurologic outcome – Prospective study with 100 consecutive patients. Radiology. 2007;243:820–827. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2433060583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nout Y.S. Mihai G. Tovar C.A. Schmalbrock P. Bresnahan J.C. Beattie M.S. Hypertonic saline attenuates cord swelling and edema in experimental spinal cord injury: a study utilizing magnetic resonance imaging. Crit. Care Med. 2009;37:2160–2166. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a05d41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parbhoo A.H. Govender S. Corr P. Vertebral artery injury in cervical spine trauma. Injury. 2001;32:565–568. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(00)00232-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton J.H. Kralovich K.A. Cuschieri J. Gasparri M. Clearing the cervical spine in victims of blunt assault to the head and neck: What is necessary? Am. Surg. 2000;66:326–30. discussion, 330–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provenzale J. MR imaging of spinal trauma. Emerg. Radiol. 2007;13:289–297. doi: 10.1007/s10140-006-0568-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramon S. Dominguez R. Ramirez L. Paraira M. Olona M. Castello T. Garcia Fernandez L. Clinical and magnetic resonance imaging correlation in acute spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 1997;35:664–673. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster R. Waxman K. Sanchez B. Becerra S. Chung R. Conner S. Jones T. Magnetic resonance imaging is not needed to clear cervical spines in blunt trauma patients with normal computed tomographic results and no motor deficits. Arch. Surg. 2005;140:762–766. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.8.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selden N.R. Quint D.J. Patel N. D'Arcy H.S. Papadopoulos S.M. Emergency magnetic resonance imaging of cervical spinal cord injuries: Clinical correlation and prognosis. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:785–792. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199904000-00057. discussion, 792–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanmuganathan K. Gullapalli R.P. Zhuo J. Mirvis S.E. Diffusion tensor MR imaging in cervical spine trauma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:655–659. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H. Tang Y. Huang L. Yang R. Wu Y. Wang P. Shi Y. He X. Liu H. Ye J. Applications of diffusion-weighted MRI in thoracic spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormality. Int. Orthop. 2007;31:375–383. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0175-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada K. Tokioka T. Sequential MR studies of cervical cord injury: correlation with neurological damage and clinical outcome. Spinal Cord. 1999;37:410–415. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sliker C.W. Mirvis S.E. Shanmuganathan K. Assessing cervical spine stability in obtunded blunt trauma patients: Review of medical literature. Radiology. 2005;234:733–739. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2343031768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song K.J. Kim G.H. Lee K.B. The efficacy of the modified classification system of soft tissue injury in extension injury of the lower cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33:E488–493. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31817b6191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus S.E. Richardson W.S. Glasziou P. Haynes R.B. Evidence-based medicine: How to practice and teach EBM. Elsevier; London: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Taneichi H. Suda K. Kajino T. Kaneda K. Traumatically induced vertebral artery occlusion associated with cervical spine injuries: Prospective study using magnetic resonance angiography. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:1955–1962. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000176186.64276.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terae S. Takahashi C. Abe S. Kikuchi Y. Miyasaka K. Gd-DTPA-enhanced MR imaging of injured spinal cord. Clin. Imaging. 1997;21:82–89. doi: 10.1016/0899-7071(95)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torina P. J. Flanders A.E. Carrino J.A. Burns A.S. Friedman D.P. Harrop J.S. Vacarro A.R. Incidence of vertebral artery thrombosis in cervical spine trauma: correlation with severity of spinal cord injury. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2005a;26:2645–2651. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torina P.J. Flanders A.E. Carrino J.A. Burns A.S. Friedman D.P. Harrop J.S. Vacarro A.R. Incidence of vertebral artery thrombosis in cervical spine trauma: Correlation with severity of spinal cord injury. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2005b;26:2645–2651. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya K. Fujikawa A. Honya K. Tateishi H. Nitatori T. Value of diffusion-weighted MR imaging in acute cervical cord injury as a predictor of outcome. Neuroradiology. 2006;48:803–808. doi: 10.1007/s00234-006-0133-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaccaro A.R. Klein G.R. Flanders A.E. Albert T.J. Balderston R.A. Cotler J.M. Long-term evaluation of vertebral artery injuries following cervical spine trauma using magnetic resonance angiography. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998;23:789–794. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199804010-00009. discussion, 795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veras L.M. Pedraza-Gutierrez S. Castellanos J. Capellades J. Casamitjana J. Rovira-Canellas A. Vertebral artery occlusion after acute cervical spine trauma. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:1171–1177. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200005010-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S.H. Shim Y.S. Park Y.H. Chung J.K. Nam J.H. Kim M.O. Park H.C. Park S.R. Min B.H. Kim E.Y. Choi B.H. Park H. Ha Y. Complete spinal cord injury treatment using autologous bone marrow cell transplantation and bone marrow stimulation with granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor: Phase I/II clinical trial. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2066–2073. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]