Abstract

This study examined masculine gender role stress (MGRS) as a mediator of the relation between adherence to dimensions of a hegemonic masculinity and hostility toward women (HTW). Among a sample of 338 heterosexual men, results indicated that MGRS mediated the relation between adherence to the status and antifemininity norms, but not the toughness norm, and HTW. Adherence to the toughness norm maintained a positive association with HTW. These findings suggest that men's HTW develops via multiple pathways that are associated with different norms of hegemonic masculinity. Implications for the prediction of men's aggression against women are discussed.

Keywords: Masculinities, Sex Roles, Gender Role Stress, Hostility Toward Women

A great deal of research during the past 30 years has focused on identifying determinants of male perpetrated violence against women and developing interventions to reduce it. Despite these efforts, men's use of aggression against women remains prevalent. In a recent community sample of unmarried heterosexual men, Abbey, Parkhill, BeShears, Clinton-Sherrod, and Zawacki (2006) found that nearly 25% of participants reportedly perpetrated at least one act of attempted or completed rape. Likewise, research indicates that 10% of college men reported that they had physically aggressed against their most recent female dating partner at least once during their relationship (Luthra & Gidycz, 2006). Furthermore, estimates from national samples indicate that over 20% of heterosexual women report being physically assaulted by a husband or male cohabitating partner at some point in their lifetime (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2000).

One risk factor pertinent to male-perpetrated aggression against women is hostility toward women (Lonsway & Fitzgerald, 1995; Malamuth, 1983). Past literature suggests that hostility toward women is an attitudinal construct that subsumes a number of empirically supported risk factors for sexual aggression (Abbey, McAuslan, & Ross, 1998; Bookwala, Frieze, Smith, & Ryan, 1992; Holtzworth-Munroe, Bates, Smutzler, & Sandin, 1997). However, Check (1988) and others (e.g., Clark & Lewis, 1977) contend that hostility toward women may be related to both men's physical and sexual aggression toward women. Indeed, pertinent theory posits that common factors may facilitate different forms of aggression against women (Clark & Lewis, 1977; Frieze, 1983; Malamuth, 1983; Marshall & Holtzworth-Munroe, 2002). In support of this view, numerous studies have established that men's hostility toward women is positively associated with men's perpetration of sexual aggression (e.g., Abbey & McAuslan, 2004; Calhoun, Bernat, Clum, & Frame, 1997; Christopher, Owens, & Stecker, 1993; Malamuth & Check, 1986; Malamuth, Linz, Heavey, Barnes, & Acker, 1995) and physical aggression (Parrott & Zeichner, 2003; Robertson & Murachver, 2007) against women. Importantly, research has shown that men's hostility toward women is the strongest predictor of sexual (Forbes, Adams-Curtis, & White, 2004) and physical aggression (Robertson & Murachver, 2007) after controlling for more specific attitudinal risk factors (e.g., rape myth acceptance, sexist perceptions, attitudes condoning violence).

Yet, despite the clear link that exists between hostility toward women and subsequent aggression toward women, it is surprising that little research has examined the factors that promote the development of this misogynistic attitudinal set. Thus, rather than directly assessing aggression toward women, the present study sought to elucidate the influence of two variables, hegemonic masculine gender role norms and masculine gender role stress, on hostile attitudes toward women. Because extant literature has examined the relation between these constructs and aggression, but not hostility, toward women, theory pertinent to the link between these risk factors and aggression toward women is reviewed.

Masculine Socialization, Hegemonic Masculinity, and Violence Against Women

Feminist sociocultural models posit a socially constructed path to men's aggression toward women (Baron & Straus, 1987; Brownmiller, 1975; Martin, Vieraitis, & Britto, 2006; Russell, 1975; Whaley & Messner, 2002). Specifically, rape is a product of men's extreme adherence to a masculine gender role that encourages men to be dominant and “manly” and women to be passive and “feminine” (for a review, see Murnen, Wright, & Kaluzny, 2002). Indeed, this view has been recognized for decades and is well articulated by Burt's (1980) conclusion that “rape is the logical and psychological extension of a dominant-submissive, competitive, sex role stereotyped culture” (p. 299). Accordingly, pertinent theory suggests that male-perpetrated aggression against women is, in many cases, a product of socialization pressures to adhere to hegemonic masculinity (O'Neil, Helms, Gable, David, & Wrightsman, 1986). Hegemonic masculinity is a kind of masculinity that promotes male dominance over women (Connell, 2005; Smith & Kimmel, 2005). Specifically, Connell (2005) defines hegemonic masculinity as “the configuration of gender practice which embodies the currently accepted answer to the problem of the legitimacy of patriarchy, which guarantees (or is taken to guarantee) the dominant position of men and the subordination of women” (p. 77). Indeed, prior research has explicitly suggested that the masculine gender role is not monolithic; rather that multiple “masculinities” and dimensions of those masculinities exist. Hence, it is not a unidimensional masculine gender role that is linked to violence, but rather specific types of masculinity (for a review, see Connell, 2005).

However, not all research has found the association between a hegemonic masculine gender role and violence against women to be particularly strong. In fact, counter to their predictions, Jakupcak, Lisak, and Roemer (2002) found that traditional beliefs about the male gender role accounted for only a small percentage of the variance of men's self-reported physical aggression within romantic relationships. This finding suggests that other factors, perhaps more proximal predictors of aggression toward women, may better explain this association. Moreover, whereas Jakupcak and colleagues (2002) examined hegemonic beliefs about the male gender role as a unidimensional construct, a substantial literature has described masculinity as a set of underlying “ideologies” that define masculine behavior (for a review, see Smiler, 2004). Again, even particular types of masculinity (e.g., hegemonic masculinity) are multifaceted and should be conceptualized in terms of specific dimensions rather than as a unidimensional construct (Fischer, Tokar, Good, & Snell, 1998). Specifically, Thompson and Pleck (1986) argue that hegemonic masculine gender role beliefs reflect adherence to theoretically distinct norms, including: (a) Status, which reflects the belief that men must gain personal status and the respect of others, (b) Toughness, which reflects the expectation that men are emotionally and physically tough and willing to be aggressive, and (c) Antifemininity, which reflects the belief that men should not engage in stereotypically feminine activities (Thompson & Pleck, 1986).

In sum, future research on the link between hegemonic masculinity and violence against women can benefit from investigating more proximal determinants of aggression toward women as well as examining theoretically distinct norms of this hegemonic form of the masculinities.

Masculine Gender Role Stress and Violence Against Women

A growing body of evidence suggests that men who hold traditional beliefs about the male gender role are at risk to experience a great deal of stress in situations where this role is challenged (Cosenzo, Franchina, Eisler, & Krebs, 2004; Eisler, Franchina, Moore, Honeycutt, & Rhatigan, 2000; Franchina, Eisler, & Moore, 2001; Good et al., 1995). This tendency to experience gender-relevant stress is commonly referred to as masculine gender role stress (Eisler & Skidmore, 1987; Eisler, Skidmore, & Ward, 1988). More specifically, masculine gender role stress refers to men's tendency to experience negative psychological (e.g., insecurity, low self-esteem, increased anger) and physiological effects (e.g., increased cardiovascular reactivity and skin conductance) from their attempts to meet societally-based standards of the male role. Not surprisingly, masculine gender role stress has been directly associated with men's aggression against women (Copenhaver, Lash, & Eisler, 2000; Eisler et al., 2000; Franchina et al., 2001; Jakupcak et al., 2002; Moore et al., 2008). Importantly, evidence suggests that masculine gender role stress is a more direct predictor of men's behavior than specific norms of masculine ideologies (Thompson, Pleck, & Ferrera, 1992). As such, it should follow that masculine gender role stress influences or accounts for the relation between pertinent norms of hegemonic masculinity and aggression toward women. Indeed, research has found that endorsement of hegemonic male gender role beliefs only predicted aggression against women among men who also reported high levels of masculine gender role stress (Jakupcak et al., 2002). This finding suggests that endorsement of hegemonic male norms does not invariably lead to aggression toward women.

These data are supported by relevant theories in the violence against women literature. For instance, men who manifest insecure and defensive feelings in their relationships with women may use sexual aggression to regain their sense of power and control (Malamuth, Sockloskie, Koss, & Tanaka, 1991; Malamuth et al., 1995). Accordingly, it has been argued that sexual aggression may act to offset any perceived masculinity threat (e.g., personal inferiority) these men may feel. Similarly, men may develop hostile attitudes toward women and aggress against them as a way to attenuate feelings of personal weakness and uncertainty and, ultimately, to displace their state of stressful discontent (Cowan & Mills, 2004). From this, it is reasonable to contend that masculine gender role stress reflects men's tendency to experience the insecurity, defensiveness, personal weakness, and stressful discontent that may be a central motivation for hostility and aggression toward women.

The Present Study

The overarching aim of the present investigation was to examine factors that may contribute to men's hostility toward women. Extant literature based on samples of young adult males (e.g., ages generally ranging from 18-35) indicates (a) that rigid adherence to hegemonic masculinity is linked to men's aggression against women (O'Neil et al., 1986), (b) that men who rigidly adhere to hegemonic masculinity are prone to experience masculine gender role stress, an attitudinal construct that is more directly associated with men's aggression against women (Thompson et al., 1992), and (c) a well-established connection between men's hostility toward women and subsequent aggression against women (e.g., Abbey & McAuslan, 2004; Calhoun et al., 1997; Forbes et al., 2004).

Nevertheless, it remains unclear how adherence to hegemonic masculine gender norms and the experience of masculine gender role stress contribute to the development of men's hostility toward women. One potential explanation is that adherence to hegemonic masculine gender norms facilitates stable tendencies among men to experience insecurity, defensiveness, personal weakness, and stressful discontent (i.e., masculine gender role stress) in relation to their personal masculine gender role that, in turn, increase the likelihood of harboring hostile attitudes toward women. Unfortunately, research to date has yet to examine collectively the association between these risk factors and men's hostility toward women. Based on this literature, we hypothesized that adherence to three male role norms (i.e., status, toughness, and antifemininity) of hegemonic masculinity would be significantly and positively associated with hostility toward women. It was predicted further that masculine gender role stress would mediate the relation between adherence to these three male role norms and hostility toward women.

Method

Participants

Self-identified heterosexual men (n = 376) were recruited from the Department of Psychology research participant pool at a large southeastern university. Participants responded to an announcement titled “Cultural Differences and Social Attitudes.” Inasmuch as heterosexual men are the most common perpetrators of sexual and physical aggression against women, it was necessary to confirm an exclusive heterosexual orientation. Thus, only men who identified as heterosexual in both arousal and behavioral experiences on the Kinsey Heterosexual-Homosexual Rating Scale (Kinsey, Pomeroy, & Martin, 1948) were included in the sample. As recommended by Savin-Williams (2006), sexual orientation is most reliably assessed when multiple components of sexual orientation are congruent. Moreover, it is suggested that the highest priority be given to indices of sexual arousal rather than self-identification and reports of sexual behavior. Indeed, these latter components of sexual orientation are more susceptible to social context effects, self-report biases, and variable meanings. Thus, among self-identified heterosexual participants, a heterosexual orientation was confirmed by endorsement of exclusive sexual arousal to females (i.e., no reported sexual arousal to males) and sexual experiences that occurred predominately with women. Using these criteria, 38 subjects were removed from subsequent analyses, which left a final sample of 338 heterosexual men. All participants received partial course credit for their participation. This study was approved by the university's Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Kinsey Heterosexual-Homosexual Rating Scale

(Kinsey et al., 1948). A modified version of this scale was used to assess prior sexual arousal and experiences. On this 7-item scale, participants rate their sexual arousal and behavioral experiences from “exclusively heterosexual” to “exclusively homosexual.” In accordance with the recommendations of Savin-Williams (2006) noted previously, only participants who endorsed exclusive heterosexual arousal and that “all” or “most” of their behavioral experiences occurred with women were included in the analyses.

Male Role Norms Scale

(Thompson & Pleck, 1986). This 26-item Likert-type scale measures men's endorsement of three dimensions of hegemonic masculine ideology: Status (e.g., “A man must stand on his own two feet and never depend on other people to help him do things”), Toughness (e.g., “A good motto for a man would be ‘When the going gets tough, the tough get going’”), and Antifemininity (e.g., “It bothers me when a man does something that I consider ‘feminine’”). Responses may range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicate greater adherence to the Status, Toughness, and Antifemininity dimensions of this masculinity. This tri-dimensional factor structure has been supported by both exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses (Sinn, 1997; Thompson & Pleck, 1986). Internal consistency coefficients for these subscales range between .74 and .81 in standardization samples (Thompson & Pleck, 1986), which was consistent with the present sample (Status: α = .81, Toughness: α = .80, Antifemininity: α = .81).

Masculine Gender Role Stress Scale

(Eisler & Skidmore, 1987). This 40-item Likert-type scale measures the extent to which gender relevant situations (e.g., “Being outperformed at work by a woman”) are cognitively appraised as stressful or threatening. Responses may range from 0 (not at all stressful) to 5 (extremely stressful). Higher scores reflect more dispositional gender role stress. Although masculine gender role stress is related to the masculine ideologies (McCreary, Newcomb, & Sadava, 1998; Walker, Tokar, & Fischer, 2000), this construct is a “unique and cohesive construct that can be measured globally” (Walker et al., 2000, p. 105). Indeed, this scale has been shown to identify situations that are cognitively more stressful for men than women and has good psychometric properties. Research with collegiate samples showed Cronbach alpha coefficients in the low .90s (Eisler et al., 1988), which was consistent with the present sample (α = .92).

Hostility Toward Women Scale

(Check, 1985). This 30-item true-false scale measures men's endorsement of hostile attitudes toward women. Higher scores indicate more hostile attitudes toward women. Sample items include “Women irritate me a great deal more than they are aware of” and “I feel that many times women flirt with men just to tease them.” Check (1985) reported an internal consistency coefficient of .80 and a test-retest reliability of .83. A Cronbach alpha coefficient of .78 was obtained in the present sample.

Procedure

Upon arrival to the laboratory, participants were greeted by an experimenter and led to a private experimental room. Participants provided informed consent and were told that the purpose of the experiment was to assess the relation between cultural differences and social attitudes. Participants were asked to complete a demographic form, the Male Role Norms scale, the Masculine Gender Role Stress scale, and the Hostility Toward Women scale. Participants completed these measures on a computer using MediaLab 2000 software (Empirisoft Research Software, Philadelphia, PA). Additional questionnaires were also completed, but are unrelated to the current study and are thus not reported here. The experimenter provided instructions on how to operate the computer program that administered the questionnaire battery and was available to answer any questions during the session. After completing the test battery, participants were debriefed, given participation credit, and thanked.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Means, standard deviations, and ranges for the key variables are reported in Table 2 along with their correlations. It was determined that multicollinearity was not an issue in these data (i.e., VIF < 10; Tolerance >.10). Furthermore, the unmediated effects of status, toughness, and antifemininity on hostility toward women (i.e., zero-order correlations) were all significant at p < .05 (.19, .32, and .20, respectively).

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for Key Variables

| Descriptives | Correlations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M | SD | range | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. |

| 1. Status | 53 | 11 | 11-77 | ||||

| 2. Toughness | 36 | 9 | 12-56 | .65 | -- | ||

| 3. Antifemininity | 26 | 9 | 7-49 | .57 | .61 | -- | |

| 4. MGRS | 114 | 34 | 0-181 | .43 | .40 | .46 | -- |

| 5. HTW | 11 | 5 | 0-25 | .19 | .32 | .20 | .36 |

Note. n = 338. MGRS = masculine gender role stress; HTW = hostility toward women. All correlations are significant, p < .001.

Mediation Analyses

The principal aim of the present investigation was to evaluate the influence of hegemonic masculine role norms and masculine gender role stress on hostile attitudes toward women. As reviewed above, it was predicted that adherence to all three norms would be significantly and positively associated with hostility toward women. In addition, it was predicted that masculine gender role stress would mediate these associations.

The Preacher and Hayes (2008) multiple mediator macro was used to test the proposed hypotheses. This macro was run three separate times to analyze the effects of each norm (status, toughness, antifemininity) while controlling for the remaining two norms. Foremost, this technique allowed us to obtain estimates of indirect effects with bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals. Bootstrapping the mediated effects is a powerful nonparametric statistical technique that accounts for the sampling distribution of the mediated effects to be non-normally distributed. Even when direct effects are normally distributed in the sample, indirect effects are usually not normally distributed. As such, many other commonly employed tests of mediation (e.g., product of coefficient's “Sobel” method) are underpowered. Consequently, these methods often engender incorrect standard errors, confidence intervals, and reported p values (Neal & Simons, 2007). Since the bootstrapping method draws random samples from sample n of the data set (with replacement), this technique is said to be equivalent to an estimation achieved from a random sample of the population. Thus, this technique increases the power of the mediational test because it is not reliant on the assumption of normality. Furthermore, though past mediational methods (e.g., Baron & Kenny, 1986) have stipulated that the direct effects of path c (i.e., total effects) must be significant in order to suggest mediation, recent advances have discounted the need for this criterion (e.g., MacKinnon, 2008). Leading researchers in the field of mediational analysis (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004; Preacher & Hayes, 2004; Shrout & Bolger, 2002) support the use of bootstrapping to obtain the most accurate confidence intervals for indirect effects in mediation.

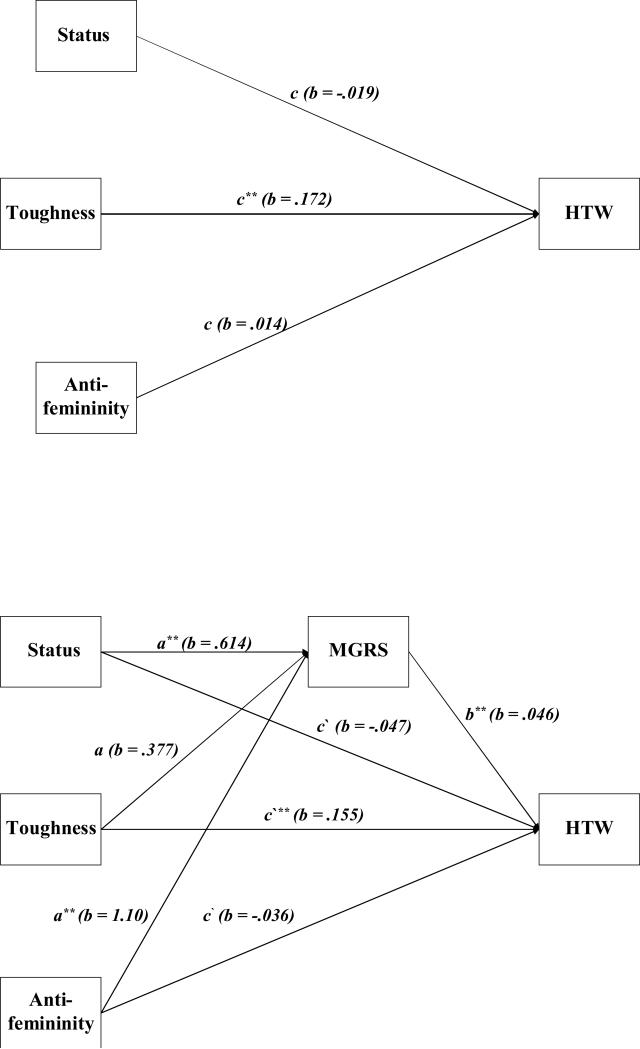

To examine total effects, hostility toward women was regressed onto each male role norm independently, while controlling for the other norms (paths c in Figure 1). In this step, only adherence to the toughness norm evidenced a statistically significant positive total effect, b = .172, SE = .039, t(336) = 4.45, p < .001 (status, b = -.019 p = .548; antifemininity, b = .014 p = .711). This indicated that adherence to the toughness norm, but not the status or antifemininity norms, was associated with greater hostility toward women.

Figure 1. Top panel.

Unmediated effect of male gender beliefs status, toughness, and antifemininity on hostility toward women. Bottom panel: Effect of male gender beliefs status, toughness, and antifemininity on hostility toward women mediated by masculine gender role stress; HTW = hostility toward women; MGRS = masculine gender role stress; * p < .05, ** p < .01

Next, masculine gender role stress was regressed onto each male role norm independently while controlling for the other norms (paths a in Figure 1). This effect was statistically significant for adherence to the status norm (b = .614, SE = .200, t(336) = 3.06, p < .01) and the antifemininity norm (b = 1.10, SE = .244, t(336) = 4.51, p < .001) but not the toughness norm (b = .377, SE = .245, t(336) = 1.54, p = .125). This result indicated that adherence to the status and antifemininity norms, but not the toughness norm, were associated with higher levels of masculine gender role stress.

Finally, the relation between masculine gender role stress and hostility toward women was tested while controlling for each male role norm. Specifically, hostility toward women was regressed simultaneously onto masculine gender role stress as well as each male role norm while controlling for the other norms (path b in Figure 1). This effect was statistically significant and indicated that higher masculine gender role stress was associated with greater hostility toward women after controlling for traditional beliefs about the male gender role, b = .046, SE = .008, t(335) = 5.54, p < .001. This step also tested the direct effects of status, toughness, and antifemininity on hostility toward women while controlling for masculine gender role stress (paths c' in Figure 1). Consistent with an effect of mediation, this path was not statistically significant for adherence to the status norm (b = -.047, SE = .031, t(335) = -1.53, p = .126) or adherence to the antifemininity norm (b = -.036, SE = .038, t(335) = -.950, p = .343). However, this path was statistically significant for adherence to the toughness norm (b = .155, SE = .037, t(335) = 4.16, p < .001). Overall, these data indicate that masculine gender role stress mediated the relation between adherence to the status and antifemininity norms, but not the toughness norm, and hostility toward women.

Analyses of indirect effects were conducted to confirm the significance of the mediational effects. To examine the indirect effects, 5,000 bootstrap samples were generated. Again, this analytic approach allowed us to obtain unbiased confidence intervals and test the significance of the indirect effects (i.e., population value ab) of adherence to the status, toughness, and antifemininity norms on hostility toward women through masculine gender role stress. As can be seen in Table 3, the 95% confidence intervals for the indirect effects of adherence to the status and antifemininity norms did not overlap with zero. This finding indicated that these indirect effects were significantly different from zero at p < .05 (two tailed). In contrast, the 95% confidence interval for the indirect effect of adherence to the toughness norm did overlap with zero. This result indicated that the indirect effect of adherence to the toughness norm was not significantly different from zero at p < .05 (two tailed).

Table 3.

Indirect Effects of Status, Toughness, and Antifemininity on Hostility Toward Women as Mediated by Masculine Gender Role Stress

| BCa 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point Estimate | Standard Error | Lower | Upper | |

| Status | .028 | .010 | .0106 | .0524 |

| Toughness | .017 | .012 | -.0031 | .0449 |

| Antifemininity | .024 | .016 | .0244 | .0882 |

Note. BCa = bias corrected and accelerated; 5,000 bootstrap samples.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to investigate the influence of two variables, adherence to hegemonic masculine gender role norms and masculine gender role stress, on men's hostile attitudes toward women. Despite the fact that endorsement of hegemonic masculine gender role norms have been linked to men's physical and sexual aggression against women (Copenhaver et al., 2000; Eisler et al., 2000; Franchina et al., 2001; Jakupcak et al., 2002; Moore et al., 2008; O'Neil et al., 1986), research to date has yet to examine how these norms collectively relate to hostility toward women — a widely accepted attitudinal risk factor for men's aggression toward women (Abbey & McAuslan, 2004; Calhoun et al., 1997; Christopher et al., 1993; Malamuth & Check, 1986; Malamuth et al., 1995; Parrott & Zeichner, 2003; Robertson & Murachver, 2007). Specifically, it was predicted that adherence to three norms of hegemonic masculinity (i.e., status, toughness, antifemininity) would be positively associated with men's hostility toward women. It was predicted further that masculine gender role stress would mediate the relation between adherence to these norms and hostility toward women. These hypotheses were partially supported.

Consistent with hypotheses, zero-order correlations indicated that adherence to these three hegemonic norms was positively associated with hostility toward women. Interestingly, when these three norms were accounted for, adherence to the status and antifemininity norms was not directly associated with men's hostility toward women. However, adherence to these two norms was indirectly related to hostility toward women through masculine gender role stress. These findings are congruent with pertinent literature on masculine gender role stress. For example, past research has found that the stress men feel when they encounter violations of the traditional male role contributes to the development of hostile and domineering attitudes toward women (Malamuth et al., 1995). Contrary to hypotheses, however, masculine gender role stress did not mediate the relation between adherence to the toughness norm and hostility toward women. Rather, adherence to the toughness norm maintained a direct effect on hostility toward women after accounting for masculine gender role stress.

Collectively, the present findings are generally consistent with pertinent theory. For instance, feminist sociocultural models (e.g., Baron & Straus, 1987; Brownmiller, 1975) posit that men's aggression toward women is associated with socialization pressure to adhere to hegemonic masculine gender role guidelines (for a review, see Murnen et al., 2002). Furthermore, in addition to men enacting these roles themselves, men who adhere to hegemonic masculine gender role guidelines expect others (e.g., women) to submit to these roles as well. Much progress has been made to foster egalitarian relationships between men and women; consequently, men who still believe in the dominance of the male gender may harbor hostile attitudes toward women because they feel their control over women is declining.

In addition, the present study suggests that men who adhere to the status and antifemininity norms of this masculinity may develop hostile attitudes toward women as a result of their tendency to experience gender-relevant stress. In other words, when these subgroups of men experience gender-relevant stress, attitudinally “lashing out” toward women may function to manage or reduce this stress. This finding is consistent with pertinent literature indicating that men's hostility and aggression toward women functions to reaffirm their sense of dominance and power (Cowan & Mills, 2004; Malamuth et al., 1991; Malamuth, et al., 1995). Thus, hostility and aggression toward women presumably alleviates feelings (e.g., insecurity, defensiveness, personal weakness, stressful discontent) that are posited to comprise state gender role stress (Cowan & Mills, 2004; Malamuth et al., 1991; Malamuth et al., 1995). It should be noted, however, that all men, regardless of the extent to which they subscribe to different masculinities, may encounter gender-relevant situations and experience gender-relevant stress in these situations. Nevertheless, the present findings suggest that men who subscribe to these norms of hegemonic masculinity are more prone to experience state gender role stress, to experience a greater intensity of gender role stress, and to cope with that stress in ways that reassert male dominance over women (e.g., hostile attitudes toward women).

Although the present findings are consistent with the reviewed literature, the fact that endorsement of the toughness norm exerted a direct effect on hostility toward women that was not mediated by masculine gender role stress is perplexing. One explanation for this effect, however, is predicated on the notion that rigid adherence to the toughness, relative to the status and antifemininity, norm is especially reflective of men's proneness toward aggressive behavior. Indeed, endorsement of the toughness norm reflects the expectation that men are emotionally and physically tough and willing to be aggressive. As such, adherence to this norm (a) may be directly associated with attitudinal variables that also reflect one's proneness toward aggression (i.e., general hostility, hostility toward women), and (b) may be less contingent upon heightened sensitivity to gender-relevant situational cues (i.e., masculine gender role stress) to cultivate hostile attitudes toward women. Put another way, men who espouse a “tough” persona likely endorse hostile attitudes toward women, and hostile attitudes toward other men for that matter, regardless of their sensitivity to gender-relevant threats. On the other hand, adherence to the status and antifemininity norms reflects masculine concepts relatively independent of men's proneness to aggression. Thus, endorsement of these hegemonic norms only fosters hostile attitudes toward women to the extent that such adherence to this form of masculinity is associated with increased masculine gender role stress. Clearly, future research is needed to investigate this possibility.

The present findings reinforce the importance of examining separately men's adherence to different norms of masculinity (Fischer et al., 1998). Indeed, the most important implication of the present study is that extreme endorsement of different norms of hegemonic masculinity appears to influence hostility toward women via different pathways. It is clearly important for future research to corroborate these pathways to men's hostility toward women. However, it is even more important for research to investigate how these pathways ultimately lead to aggression toward women.

Although the present findings provide new insight into the development of men's hostile beliefs toward women, this study is not without limitations. First, due to the correlational, cross-sectional design of the study, temporal or causal conclusions about the relations between the predictor, mediating, and criterion variables in this study should be considered tentative. Thus, future research would benefit from employing experimental or longitudinal methods that are better able to identify causal and temporal relationships, respectively, among these variables. Second, this study only measured three dimensions of hegemonic masculinity. Since a great deal of research has indicated that masculinity should be conceptualized as multiple multifaceted “masculinities” (for a review, see Connell, 2005), interpretations garnered from these results should only be applied to this particular subset of the masculinities. Third, the present study only assessed men's self-reported hostile attitudes toward women; men's perpetration of aggression was not assessed. Thus, any conclusions regarding the extension of the present findings to the prediction of aggression against women should be made with caution. However, this limitation is tempered by numerous studies linking hostility toward women to subsequent aggression toward women (Abbey & McAuslan, 2004; Calhoun et al., 1997; Check, 1988; Malamuth et al., 1995; Parrott & Zeichner, 2003; Robertson & Murachver, 2007). Nevertheless, as previously noted, future research is needed to investigate how endorsement of hegemonic masculinity and masculine gender role stress lead to hostility, and ultimately aggression, toward women. As research continues to identify factors that contribute to men's hostility toward women and link this hostility to men's aggression against women, additional points of intervention will be elucidated that may enhance efforts to prevent violence against women.

Table 1.

Sample Demographics

| Variable | M (SD) or % |

|---|---|

| Age | 20.36 (3.6) |

| Education (in years) | 14.33 (1.7) |

| Race | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 50% |

| African-American | 24% |

| Asian-American | 17% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 2% |

| Other | 7% |

| Relationship Status | |

| Single, never married | 93% |

| Married | 4% |

| Not married, but living with intimate partner | 2% |

| Divorced | 1% |

Note. n = 338.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant R01-AA-015445 from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Biographical Statement

Kathryn E. Gallagher, B.A., is a doctoral student in Clinical Psychology at Georgia State University. Her research interests primarily focus on identifying risk factors (e.g., hegemonic masculine ideology, alcohol) for men's physical aggression against underrepresented populations (e.g., women, sexual minorities). Additionally, she is interested in examining mindfulness as an intervention for aggression.

Dominic J. Parrott, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor of Psychology at Georgia State University. His research program examines determinants of violent behavior and is primarily focused on the interface between substance use, particularly alcohol, and aggression as well as risk factors for aggression toward sexual minorities and women.

Contributor Information

Kathryn E. Gallagher, Department of Psychology, Georgia State University kgallagher34@gmail.com

Dominic J. Parrott, Department of Psychology, Georgia State University P.O. Box 5010, Atlanta, Georgia 30302-5010 Phone: 404-413-6287, Fax: 404-413-6207, parrott@gsu.edu

References

- Abbey A, McAuslan P. A longitudinal examination of male college students’ perpetration of sexual assault. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:747–756. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, McAuslan P, Ross LT. Sexual assault perpetration by college men: The role of alcohol, misperception of sexual intent, and sexual beliefs and experiences. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1998;17:167–196. [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Parkhill MR, BeShears R, Clinton-Sherrod AM, Zawacki T. Cross-sectional predictors of sexual assault perpetration in a community sample of single African American and Caucasian men. Aggressive Behavior. 2006;32:54–67. doi: 10.1002/ab.20107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron L, Straus MA. Four theories of rape: A macrosociological analysis. Social Problems. 1987;34:467–489. [Google Scholar]

- Bookwala J, Frieze IH, Smith C, Ryan K. Predictors of dating violence: A multivariate analysis. Violence and Victims. 1992;7:297–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt MR. Cultural myths and supports for rape. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980;38:217–230. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.38.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownmiller S. Against our will: Men, women, and rape. Fawcett-Columbine; New York: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun KS, Bernat JA, Clum GA, Frame CL. Sexual coercion and attraction to sexual aggression in a community sample of young men. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1997;12:392–406. [Google Scholar]

- Check JV. The Hostility Toward Women scale. Dissertation Abstracts International. 1985;45:3993. [Google Scholar]

- Check JVP. In: Hostility towards women: Some theoretical considerations. Violence in intimate relationships. Russell GW, editor. PMA; New York: 1988. pp. 43–65. [Google Scholar]

- Christopher FS, Owens LA, Stecker HL. Exploring the darkside of courtship: A test of a model of male premarital sexual aggressiveness. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1993;55:469–479. [Google Scholar]

- Clark L, Lewis D. Rape: The price of coercive sexuality. Women's Press; Toronto, Canada: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Copenhaver MM, Lash SJ, Eisler RM. Masculine gender-role stress, anger, and male intimate abusiveness: Implications for men's relationships. Sex Roles. 2000;42:405–414. [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW. Masculinities. 2nd ed. University of California Press; Los Angeles: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cosenzo KA, Franchina JJ, Eisler RM, Krebs D. Effects of masculine gender-relevant task instructions on men's cardiovascular reactivity and mental arithmetic performance. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2004;5:103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan G, Mills RD. Personal inadequacy and intimacy predictors of men's hostility toward women. Sex Roles. 2004;51:67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Eisler RM, Franchina JJ, Moore TM, Honeycutt HG, Rhatigan DL. Masculine gender role stress and intimate abuse: Effects of gender relevance of conflict situations on men's attributions and affective responses. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2000;1:30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Eisler RM, Skidmore JR. Masculine gender role stress: Scale development and component factors in the appraisal of stressful situations. Behavior Modification. 1987;11:123–136. doi: 10.1177/01454455870112001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisler RM, Skidmore JR, Ward CH. Masculine gender-role stress: Predictor of anger, anxiety, and health-risk behaviors. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1988;52:133–141. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AR, Tokar DM, Good GE, Snell AF. More on the structure of male role norms. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1998;22:135–155. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes GB, Adams-Curtis LE, White KB. First-and second-generation measures of sexism, rape myths, and related beliefs, and hostility toward women: Their interrelationships and association with college students’ experiences with dating aggression and sexual coercion. Violence Against Women. 2004;10:236–261. [Google Scholar]

- Franchina JJ, Eisler RM, Moore TM. Masculine gender role stress and intimate abuse: Effects of masculine gender relevance of dating situations and female threat on men's attributions and affective responses. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2001;2:34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Frieze IH. Investigating the causes and consequences of marital rape. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 1983;8:532–553. [Google Scholar]

- Good GE, Robertson JM, O'Neil JM, Fitzgerald LF, Stevens M, DeBord KA, Bartels KM, Braverman DG. Male gender role conflict: Psychometric issues and relations to psychological distress. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1995;42:3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Holtzworth-Munroe A, Bates A, Smutzler N, Sandin E. A brief review of the research of husband violence. Part I: Maritally violent versus nonviolent men. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 1997;2:65–99. [Google Scholar]

- Jakupcak M, Lisak D, Roemer L. The role of masculine ideology and masculine gender role stress in men's perpetration of relationship violence. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2002;3:97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsey AC, Pomeroy WB, Martin CE. Sexual behavior in the human male. W.B. Saunders; Philadelphia: 1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonsway KA, Fitzgerald LF. Attitudinal antecedents of rape myth acceptance: A theoretical and empirical reexamination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;68:704–711. [Google Scholar]

- Luthra R, Gidycz CA. Dating violence among college men and women: Evaluation of a theoretical model. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21:717–731. doi: 10.1177/0886260506287312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis. Taylor & Francis Group; New York: [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamuth NM. Factors associated with rape as predictors of laboratory aggression against women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983;45:432–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamuth NM, Check JVP. Sexual arousal in response to aggression: Ideological, aggressive, and sexual correlates. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;50:330–340. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.50.2.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamuth NM, Linz D, Heavey CL, Barnes G, Acker M. Using the confluence model of sexual aggression to predict men's conflict with women: A 10-year follow-up study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:353–369. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.2.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamuth NM, Sockloskie R, Koss MP, Tanaka J. The characteristics of aggressors against women: Testing a model using a national sample of college students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:670–681. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.5.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall AD, Holtzworth-Munroe A. Varying forms of husband sexual aggression: Predictors and subgroup differences. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16:286–296. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin K, Vieraitis LM, Britto S. Gender equality and women's absolute status: A test of the feminist models of rape. Violence Against Women. 2006;12:321–339. doi: 10.1177/1077801206286311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreary DR, Newcomb MD, Sadava SW. Dimensions of the male gender role: A confirmatory factor analysis in men and women. Sex Roles. 1998;39:81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Moore TM, Stuart GL, McNulty JK, Addis ME, Cordova JV, Temple JR. Domains of masculine gender role stress and intimate partner violence in a clinical sample of violent men. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2008;9:82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Murnen SK, Wright C, Kaluzny G. If “boys will be boys,” then girls will be victims? A meta-analytic review of the research that relates masculine ideology to sexual aggression. Sex Roles. 2002;46:359–375. [Google Scholar]

- Neal DJ, Simons JS. Inference in regression models of heavily skewed alcohol use data: A comparison of ordinary least squares, generalized linear models, and bootstrap resampling. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:441–452. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.4.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neil JM, Helms BJ, Gable RK, David L, Wrightsman LS. Gender-role conflict scale: College men's fear of femininity. Sex Roles. 1986;14:335–350. [Google Scholar]

- Parrott DJ, Zeichner A. Effects of trait anger and negative attitudes towards women on physical assault in dating relationships. Journal of Family Violence. 2003;18:301–307. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson K, Murachver T. Correlates of partner violence for incarcerated women and men. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2007;22:639–655. doi: 10.1177/0886260506298835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell DEH. The politics of rape. Stein and Day; New York: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC. Who's gay? Does it matter? Psychological Science. 2006;15:40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinn JS. The predictive and discriminant validity of masculinity ideology. Journal of Research in Personality. 1997;31:117–135. [Google Scholar]

- Smiler AP. Thirty years after the discovery of gender: Psychological concepts and measures of masculinity. Sex Roles. 2004;50:15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Smith T, Kimmel M. The hidden discourse of masculinity in gender discrimination law. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 2005;30:1827–1849. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson EH, Pleck JH. The structure of male role norms. American Behavioral Scientist. 1986;29:531–543. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson EH, Pleck JH, Ferrera DL. Men and masculinities: Scales for masculinity ideology and masculinity-related constructs. Sex Roles. 1992;27:573–604. doi: 10.1007/BF02651094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Prevalence and consequences of male-to-female and female-to-male intimate partner violence as measured by the national violence against women survey. Violence Against Women. 2000;6:142–161. [Google Scholar]

- Walker DF, Tokar DM, Fischer AR. What are eight masculinity-related instruments measuring? Underlying dimensions and their relations to sociosexuality. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2000;2:98–108. [Google Scholar]

- Whaley RB, Messner SF. Gender equality and gendered homicides. Homicide Studies: An Interdisciplinary & International Journal. 2002;6:188–210. [Google Scholar]