Abstract

Reaction methods for selective C–H amination are finding ever-increasing utility for the preparation of nitrogen-derived fine chemicals. This brief account highlights the remarkable versatility of dirhodium-based catalysts for promoting oxidation of aliphatic C–H centers in both intra- and intermolecular reaction processes.

1. Introduction

In the past decade, a wave of new reaction technologies has been unveiled that make possible the selective modification of aliphatic and arene C–H bonds.1,2 The availability of such methods begets an addendum to the Logic of Chemical Synthesis, as the C–H bond may now be considered a synthon for other functional groups.3 Our lab has been engaged in this problem area for some time now, focusing primarily on the development of selective reactions for the oxidation of aliphatic C–H bonds to generate alcohol and amine products.4 As amines and amine derivatives are ubiquitous in designed molecules and natural products, the problem of C–H amination has large application potential and has been a particularly fruitful area of research (Figure 1). This highlight provides an overview of our studies to elucidate both intra- and intermolecular processes for C–H bond amination. We are by no means the only research group interested in this problem area and, while this review is meant to be a personal account, acknowledgement to others’ work will be made where relevant.5 The general subject of C–H to C–N bond conversion has been reviewed in a number of comprehensive treatises to which interested readers are referred.6

Figure 1.

Heterocycle synthesis through intramolecular C–H amination.

2. Initial Discoveries

The literature is replete with chemical oxidants that have the thermodynamic capacity to react with aliphatic C–H bonds of all types. For example, the enthalpic energy for the reaction between a simple hydrocarbon such as cyclohexane and cyclohexylazide to generate dicyclohexylamine and dinitrogen is estimated to be ≤ −40 kcal/mol.7 Despite such a favorable thermodynamic driving force, this transformation does not occur at any measurable rate under normal reaction conditions. Accordingly, the problem of C–H oxidation is, in its essence, a problem of kinetics, underscored by the challenge to identify catalyst systems that reduce the activation barrier for the C–H oxidation event while maintaining some ability to discriminate between C–H bonds in different steric and electronic environments. The countless examples of selective diazoalkane (i.e., carbenoid) C–H insertion processes with dimeric rhodium(II) tetracarboxylate and tetraamidate complexes are exceptional in this regard.8 As originally noted by Breslow and, later, elaborated by Müller, these same catalysts can perform analogous C–H amination reactions using hypervalent iminoiodinanes as nitrenoid precursors (Figure 2).9,10 These collective works marked the starting point for our investigations.

Figure 2.

Early examples of C–H amination using iminoiodinane reagents.

A select few hypervalent iminoiodinane reagents, the most notable of which is TsN=IPh, have enjoyed great utility as electrophilic N-atom donors, particularly for the generation of aziridine products from alkenes. Preparation of iminoiodinanes, however, has been limited to a small subset of sulfonamide derivatives, thus restricting the ability to expand further the use of this class of iodine(III) oxidants.11 Both Che and we realized that in situ preparation of an iminoiodinane species might be possible by simply mixing an amide starting material with PhI(OAc)2, PhI=O, or a related iodine(III) reagent.12,13 This idea has proven successful and has enabled the application of carbamate, urea, guanidine, alkylsulfonamide, sulfamate, sulfamide, and phosphoramide starting materials in electrophilic N-atom transfer reactions (Figure 1). To our knowledge, the equivalent iminoiodinanes have not been described for any of these materials, save for a single trichloroethylsulfamate derivative.

Initial discoveries from our lab highlighted the value of carbamate and sulfamate ester derivatives as substrates for intramolecular C–H amination reactions (Figure 3).14 Commercial Rh2(OAc)4 or Rh2(oct)4 proved generally effective for many of these reactions, and that remains true today (catalyst loading typically range from 2–5 mol%, TONs ~20–50). Reactions of carbamates occasionally call for application of the Ikegami/Hashimoto Rh2(O2CCPh3)4, a complex easily generated from Rh2(OAc)4.15 Despite efforts to optimize further the carbamate insertion reaction, this substrate type has been the most limited. Reactions of 2° alcohol-derived carbamates generally yield ketone products rather than the desired oxazolidinones.14,16 Oxidation of 3°, benzylic, and allylic C–H bonds can afford oxazolidinone products in modest to high yields; by contrast, amination of 2° methylene centers has always been difficult. A report by He describes the application of a Ag(I)•terpyridine catalyst (thought to be dimeric) for intramolecular carbamate C–H insertion reactions.17 The performance of this catalyst system is as good and in some cases exceeds that of any dimeric rhodium catalyst tested in our hands.

Figure 3.

Nitrenoid C–H insertion through in situ iodoimine formation.

Current limitations of the carbamate process notwithstanding, a number of examples demonstrate the utility of carbamate activation and intramolecular C–H insertion for oxazolidinone synthesis. Oxidation of stereogenic 3° C–H centers occurs with complete retention of stereochemistry (as measured by GC), thus making accessible optically pure tetrasubstituted amine derivatives. Reactions are generally tolerant of common functional groups (acetals, silyl ethers, esters, 2° and 3° amides) and oxazolidinone formation is strongly favored over the larger six-membered ring. Indeed, we have only noted the formation of larger heterocyclic ring products in one or two rare instances. In this vein, cyclization reactions with sulfamate esters are nicely complementary to those of carbamate esters, the former class of substrates showing a strong predilection towards the six-membered ring [1,2,3]-oxathiazinane-2,2-dioxide (Figure 4).18 These cyclic sulfamate heterocycles have added value as electrophilic azetidine equivalents and can be made to react with a number of common nucleophiles to generate 1,3-difunctionalized amine derivatives.19

Figure 4.

Stereospecific and stereoselective C–H amination with sulfamate ester substrates.

3. Method Development

We have found sulfamate esters to be optimal substrates for both intra- and intermolecular (vide infra) C–H amination reactions.18 Most of our mechanistic insights have come from studies with this family of reagents, as will be highlighted in the subsequent section. The strong bias for six-membered ring formation can sometimes be overridden by appropriate substrate design to form both five- and seven-membered ring products, though in competition, the larger seven-membered ring is generally preferred. A report by Che indicates that a Ru(II)-porphyrin catalyst will engage phenethyl alcohol-derived sulfamates to give the five-membered heterocycles in modest to high yields.20 In our hands, dirhodium catalysts have typically underperformed with these same phenylethyl alcohol substrates. Six-and, in some cases, seven-membered ring formation can be highly diastereoselective using either chiral 2° alcohol- or branched 1° alcohol-derived substrates. A transition state model that has proven highly predictive for these diastereoselective transformations posits a chair-like arrangement in the stereochemical-defining C–H insertion event (Figure 5).21

Figure 5.

Diastereoselective Rh-catalyzed C–H insertion through a putative chair-like transition structure.

Sulfamate esters and alkylsulfonamides have been examined as substrates in reactions with optically active Rh, Ru, and Cu catalysts for enantioselective C–H amination reactions. Examples of intermolecular C–H amination with simple hydrocarbons such as indane and tetralin are many and are reported to give high enantiomeric product ratios using catalysts derived from chiral α-amino acids.22 It is worth noting here the impressive achievements of Dauban and Dodd, who have described a truly differential process for diastereoselective intermolecular C–H amination of benzylic hydrocarbons (Figure 6).23 The combination of an optically active dirhodium tetracarboxylate catalyst and a chiral sulfonimidamide nitrogen source efficiently produces benzylic and allylic amination products with exceptional levels of diastereoinduction.

Figure 6.

Highly selective intermolecular C–H amination reactions, as described by Dauban and Dodd; DCE = 1,2-dichloroethane.

Recent reports describe, for the first time, asymmetric intramolecular oxidations with 3-arylpropanol sulfamates. Such transformations are exacted using a Ru(II)-pybox pre-catalyst or a tetralactamate-based rhodium dimer (Figure 7).24,25 While the substrate scope is not extensive with either of these catalyst systems, product enantiomeric excesses can exceed 90%.

Figure 7.

A chiral tetra-lactamate dirhodium catalyst for enantioselective C–H amination with arylpropyl-derived sulfamates.

The advent of a strapped carboxylate dirhodium catalyst, Rh2(esp)2, marks an important advance for C–H amination chemistry.26 This particular catalyst is unmatched in performance by other, more common tetracarboxylate systems (i.e., Rh2(oct)4, Rh2(O2CCPh3)4). Intramolecular sulfamate ester insertion reactions can be effected in high yield with catalyst loadings as low as 0.1 mol% (Figure 8). In addition, C–H amination reactions with sulfamide, urea, and guanidine substrates are efficiently promoted using Rh2(esp)2.27,28 Others dirhodium complexes manifestly under-perform with these types of starting materials.

Figure 8.

Optimal catalyst performance with a strapped carboxylate ligand design.

Extensive mechanistic studies have been conducted to determine the factors that influence catalyst stability and turnover numbers in sulfamate C–H amination reactions.29 It appears that Rh2(esp)2 does not suffer, in the way that other dirhodium catalysts do, from rapid carboxylate ligand exchange under the reaction conditions. Nuclear magnetic resonance experiments with 13C-labeled Rh2(OAc)4 have shown that 13AcOH is produced within 60 s of initiating an amination reaction. Control experiments indicate that the hypervalent iodine oxidant, PhI(OAc)2, reacts with Rh2(OAc)4 to induce carboxylate exchange; the analogous reaction is not observed with Rh2(esp)2.30 We speculate that carboxylate metathesis somehow renders the catalyst susceptible to oxidative decomposition through a pathway(s) that is still undetermined at this time.

We have gained additional insight into the differential performance of Rh2(esp)4 by following changes in the reaction solution color and by identifying a one-electron oxidized form of the catalyst, [Rh2(esp)2]+.30 Generation of this bright red species appears to be correlated with the ability of the substrate to rapidly intercept the putative nitrenoid oxidant. That is to say, if the nitrenoid does not react quickly with the substrate C–H bond, the mixed-valent [Rh2(esp)2]+ is formed. Fortuitously, certain carboxylic acids, including tBuCO2H – the byproduct of using PhI(O2CtBu)2 as a terminal oxidant – are capable of reducing [Rh2(esp)2]+ back to the neutral, bright green Rh(II)/(II) dimer. We believe that one of the principal reasons why Rh2(esp)2 is so successful for amination reactions is due to the stability of its one-electron oxidized form. Other tetracarboxylate rhodium dimers appear to quickly decompose when oxidized to the Rh(II)/(III) level, as evidence by the fast bleaching of the solution color to a pale yellow. Under the reaction conditions, the stability of [Rh2(esp)2]+ is such that it can re-enter the catalytic cycle as opposed to simply decomposing to inactive Rh(III) species. We have found that the addition of different carboxylic additives to the reaction medium can improve overall turnover numbers and product yields, a result that we ascribe to the ability of certain carboxylic acids to reduce rapidly the Rh(II)/(III) dimer.30,31

Catalyst development and mechanistic studies have enabled us to advance an effective method for intermolecular C–H amination (Figure 10).32 This process utilizes Rh2(esp)2, PhI(O2CtBu)2 as oxidant, and Cl3CCH2OSO2NH2 (TcesNH2) as the nitrogen source. Slow addition of oxidant to a solution of catalyst, oxidant, and one equivalent of substrate can result in moderate to high isolated yields of benzylic amine products. In general, benzylic hydrocarbons display optimal performance as substrates for this reaction. This finding is somewhat surprising given earlier mechanistic data that show 3° C–H bonds to be slightly more reactive (~2–3 times) than benzylic C–H centers.18,32 Investigations are ongoing to determine the origin of these reactivity/selectivity differences and to improve further this intermolecular oxidation method with the ultimate goal of identifying conditions that allow for the high yielding, selective and stereospecific modification of 3° C–H bonds.

Figure 10.

Intermolecular benzylic C–H amination promoted efficiently by Rh2(esp)2.

4. Applications in Synthesis

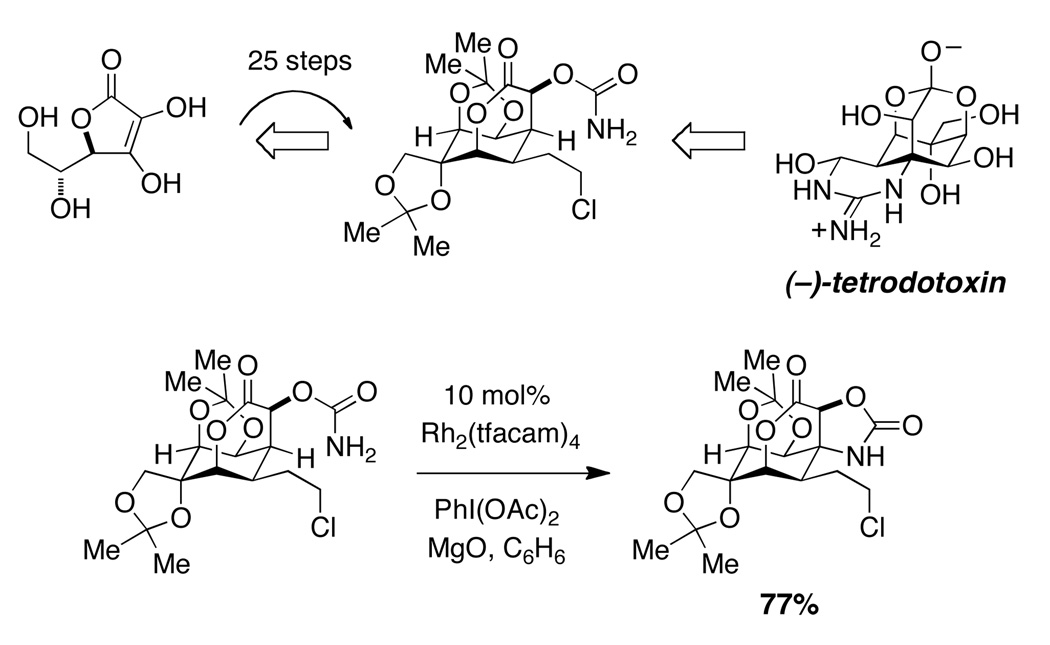

Natural products synthesis provides an optimal forum for demonstrating the potential of C–H amination technologies to transform the practice of small molecule assembly. De novo synthesis of the toxin synonymous with the Japanes fugu, (−)-tetrodotoxin, is exemplary in this regard (Figure 11).33 The application of a selective carbamate insertion reaction at step twenty-five in the synthetic sequence occurs in high yield and with exquisite selectivity for the bridgehead 3° C–H bond. The compatibility of the insertion reaction with common functional groups is a general feature of this method and related reactions with other nitrogen derivatives (i.e., sulfamates, sulfonamides, sulfamides, guanidines, ureas). The application of carbamate C–H amination has also found utility in the preparation of amino acid derivatives and amino sugars.34

Figure 11.

Carbamate C–H insertion highlighted in the synthesis of the fugu toxin.

Sulfamate ester C–H insertion has been used to synthesize β-amino and diamino acids, the latter of which is embedded in the structure of the manzacidins (Figure 12).35 Stereospecific 3° C–H amination offers a direct method for crafting the stereogenic tetrasubstituted amine moiety common to this small family of natural products. The synthesis of such structural elements is one of the signature features of the Rh-catalyzed amination process.

Figure 12.

Sulfamate ester oxidation en route to complex amino acids.

Ethereal C–H bonds are competent substrates for metal-mediated C–H amination. The heightened reactivity of such centers vis-à-vis benzylic and 2° C–H bonds can be exploited for the purpose of biasing the positional selectivity of the oxidation event in substrates of increasing complexity.36 The corresponding N,O-acetals have value as latent electrophiles to which a number of different nucleophiles may be added under Lewis acid catalysis. We have used this technology in a first-generation synthesis of the paralytic shellfish poison, (+)-saxitoxin (Figure 13).37 Others have found application of the ethereal C–H bond amination for the purpose of modifying sugar derivatives.38

Figure 13.

Unique N,O-acetal electrophiles derived from sulfamate ester C–H amination.

5. Conclusion

The past decade has witnessed a large upsurge in methods development aimed at the general problem of selective C–H functionalization. Through the invention of intramolecular reaction processes involving carbamate and sulfamate esters, and later sulfamides, sulfonamides, hydroxylamine sulfamates, guanidines, and ureas, C–H amination is beginning to take root as a mainstream technology for heterocycle and amine assembly. These discoveries have inspired collateral efforts to develop intermolecular amination reactions and to demonstrate the strategic value of such methods in complex chemical synthesis. Such advances notwithstanding, controlling chemoselectivity through reagent design in substrates possessing multiple C–H bond-types and other reactive functional groups (e.g., alkenes) remains a grand challenge for tomorrow’s research.

Figure 9.

Rh2(esp)2-catalyzed intramolecular C–H amination to prepare 1,3-diamines.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the many coworkers whose intellectual contributions and tireless efforts have brought our ideas in catalytic C–H functionalization to fruition. Support for our program has been made available from the National Science Foundation and the NSF Center for Stereoselective C–H Functionalization, the National Institutes of Health, and Stanford University. Generous research support has also been provided to our lab from Pfizer.

References

- 1.(a) Yu J-Q, Shi Z, editors. “C–H Activation”, Topics in Current Chemistry. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2010. pp. 1–384. [Google Scholar]; (b) Dyker G, editor. “Handbook of C–H Transformations: Applications in Organic Synthesis”. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2005. pp. 1–688. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Yeung CS, Dong VM. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1215. doi: 10.1021/cr100280d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Crabtree RH. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:575. doi: 10.1021/cr900388d. and references therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Giri R, Shi B-F, Engle KM, Maugel N, Yu J-Q. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:3242. doi: 10.1039/b816707a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Hartwig JF. Nature. 2008;455:314. doi: 10.1038/nature07369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Murahashi S-I, Zhang D. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008;37:1490. doi: 10.1039/b706709g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Dick AR, Sanford MS. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:2439. [Google Scholar]; (g) Godula K, Sammes D. Science. 2006;312:67. doi: 10.1126/science.1114731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Labinger JA, Bercaw JE. Nature. 2002;417:507. doi: 10.1038/417507a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corey EJ, Cheng X-M. The Logic of Chemical Synthesis. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Du Bois J. CHEMTRACTS – Org. Chem. 2005;18:1. Also, see: McNeill E, Du Bois J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:10202. doi: 10.1021/ja1046999. Litvinas ND, Brodsky BH, Du Bois J. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:4513. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901353. Brodsky BH, Du Bois J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:15391. doi: 10.1021/ja055549i.

- 5.For some leading references, see: Liu Y, Wei J, Che C-M. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:6926. doi: 10.1039/c0cc01825b. Lu H-J, Subbarayan V, Tai J-R, Zhang PX. Organometallics. 2010;29:389. Badiei YM, Dinescu A, Dai X, Palomino RM, Heinemann FW, Cundari TR, Warren TH. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:9961. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804304. Shen M, Leslie BE, Driver TG. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:5056. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800689. Li Z, Capretto DA, Rahaman R, He C. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:5184. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700760. Lebel H, Huard K, Lectard S. Org. Lett. 2007;9:639. doi: 10.1021/ol062953t. Liang C, Robert-Pedlard F, Fruit C, Müller P, Dodd RH, Dauban P. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:4641. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601248.

- 6.(a) Lebel H. In: Catalyzed Carbon-Heteroatom Bond Formation. Yudin A, editor. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2011. pp. 137–156. [Google Scholar]; (b) Collet F, Dodd RH, Dauban P. Chem. Commun. 2009:5061. doi: 10.1039/b905820f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Davies HML, Manning JR. Nature. 2008;451:417. doi: 10.1038/nature06485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Díaz-Requejo MM, Pérez PJ. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:3379. doi: 10.1021/cr078364y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Values for ΔHf° were taken from the National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST) Chemistry Webbook, http://webbook.nist.gov/chemistry. The following values (kcal/mol) were used: cyclohexane(l) = −37.5; cyclohexylazide(l) = 25.9; dicyclohexylamine(l) = −54.2.

- 8.(a) Doyle MP, McKervey MA, Ye T. Modern Catalytic Methods for Organic Synthesis with Diazo Compounds. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 1998. [Google Scholar]; (b) Davies HML, Dick AR. Top. Curr.Chem. 2010;292:303. doi: 10.1007/128_2009_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Doyle MP, Duffy R, Ratnikov M, Zhoi L. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:704. doi: 10.1021/cr900239n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Doyle MP, Ren T. Prog. Inorg. Chem. 2001;49:113. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Breslow R, Gellman SH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;105:6728. Also, see: Breslow R, Gellman SH. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Comm. 1982:1400.

- 10.(a) Müller P. Adv. Catal. Processes. 1997;2:113. [Google Scholar]; (b) Nägeli I, Baud C, Bernardinelli G, Jacquier Y, Moran M, Müller P. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1997;80:1087. [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Dauban P, Dodd RH. Synlett. 2003:1571. [Google Scholar]; (b) Evans DA, Faul MM, Bilodeau MT, Anderson BA, Barnes DM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:5328. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu X-Q, Huang J-S, Zhou X-G, Che C-M. Org. Lett. 2000;2:2233. doi: 10.1021/ol000107r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Espino CG, Du Bois J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2001;40:598. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010202)40:3<598::AID-ANIE598>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Espino CG, Du Bois J. In: Modern Rhodium-Catalyzed Organic Reactions. Evans PA, editor. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2005. pp. 379–416. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hashimoto S-i, Watanabe N, Ikegami S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:2709. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Espino CG. Ph.D. Thesis. Stanford, CA: Stanford University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cui Y, He C. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:4210. doi: 10.1002/anie.200454243. Also, see reference 5e.

- 18.Williams Fiori K, Espino CG, Brodsky BH, Du Bois J. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:3042. [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Bower JF, Rujirawanicha J, Gallagher T. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010;8:1505. doi: 10.1039/b921842d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Moss TA, Alonso B, Fenwick DR, Dixon DJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:568. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Meléndez RE, Lubell WD. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:2581. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liang J-L, Yuan S-X, Huang J-S, Yu W-Y, Che C-M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:3465. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020916)41:18<3465::AID-ANIE3465>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wehn PM, Lee J, Du Bois J. Org. Lett. 2003;5:4823. doi: 10.1021/ol035776u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Reddy RP, Davies HML. Org. Lett. 2006;8:5013. doi: 10.1021/ol061742l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yamawaki M, Kitagaki S, Anada M, Hashimoto S. Heterocycles. 2006;69:527. [Google Scholar]; (c) Fruit C, Müller P. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2004;15:1019. [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Collet F, Lescot C, Liang C, Dauban P. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:10401. doi: 10.1039/c0dt00283f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Liang C, Fruit C, Robert-Peillard F, Müller P, Dodd RH, Dauban P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:343. doi: 10.1021/ja076519d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milczek E, Boudet N, Blakey S. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:6825. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zalatan DN, Du Bois J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:9220. doi: 10.1021/ja8031955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Espino CG, Fiori Williams K, Kim M, Du Bois J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:15378. doi: 10.1021/ja0446294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurokawa T, Kim M, Du Bois J. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:2777. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim M, Mulcahy JV, Espino CG, Du Bois J. Org. Lett. 2006;8:1073. doi: 10.1021/ol052920y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.(a) Huard K, Lebel H. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:6222. doi: 10.1002/chem.200702027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Müller P, Baud C, Nägeli I. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 1998;11:597. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zalatan DN, Du Bois J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:7558. doi: 10.1021/ja902893u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.(a) Zalatan DN. Ph.D. Thesis. Stanford, CA: Stanford University; 2009. [Google Scholar]; (b) Roizen JL, Zalatan DN, Du Bois J. unpublished results [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fiori Williams K, Du Bois J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:562. doi: 10.1021/ja0650450. Also see reference 23 and Norder A, Herrmann P, Herdtweck E, Bach T. Org. Lett. 2010;12:3690. doi: 10.1021/ol101517v. Fan R, Li W, Pu D, Zhang L. Org. Lett. 2009;11:1425. doi: 10.1021/ol900090f.

- 33.Hinman A, Du Bois J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:11510. doi: 10.1021/ja0368305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.(a) Parker KA, Chang W. Org. Lett. 2003;5:3891. doi: 10.1021/ol035479p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Huang H, Panek JS. Org. Lett. 2003;5:1991. doi: 10.1021/ol034582b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Trost BM, Gunzner JL, Dirat O, Rhee YH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:10396. doi: 10.1021/ja0205232. Also, see: Yakura T, Yoshimoto Y, Ishida C, Mabuchi S. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:4429.

- 35.Wehn PM, Du Bois J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:12950. doi: 10.1021/ja028139s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.(a) Williams Fiori K, Fleming JJ, Du Bois J. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:4349. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fleming JJ, Williams Fiori K, Du Bois J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:2028. doi: 10.1021/ja028916o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fleming JJ, McReynolds MD, Du Bois J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:9964. doi: 10.1021/ja071501o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wyszynski FJ, Thompson AL, Davis BG. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010;8:4246. doi: 10.1039/c0ob00113a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Toumieux S, Compain P, Martin OR, Selkti M. Org. Lett. 2006;8:4493. doi: 10.1021/ol061649x. Also, see: Toumieux S, Compain P, Martin OR. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:2155. doi: 10.1021/jo702350u.