Abstract

Systemic treatment with the tetracycline derivative, minocycline, attenuates neurological deficits in animal models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, hypoxic-ischemic brain injury, and multiple sclerosis. Inhibition of microglial activation within the CNS is one mechanism proposed to underlie the drug's beneficial effects in these systems. Given the widening scope of acute viral encephalitis caused by mosquito-borne pathogens, we investigated the therapeutic effects of minocycline in a murine model of fatal alphavirus encephalomyelitis where widespread microglial activation is known to occur. We found that minocycline conferred significant protection against both paralysis and death, even when started after viral challenge and despite having no effect on CNS virus replication or spread. Further studies demonstrated that minocycline inhibited early virus-induced microglial activation, and that diminished CNS production of the inflammatory mediator, interleukin (IL)-1β, contributed to its protective effect. Therapeutic blockade of IL-1 receptors also conferred significant protection in our model, validating the importance of the IL-1 pathway in disease pathogenesis. We propose that interventions targeting detrimental host immune responses arising from activated microglia may be of benefit in humans with acute viral encephalitis caused by related mosquito-borne pathogens. Such treatments could conceivably act through neuroprotective rather than antiviral mechanisms to generate these clinical effects.

Keywords: viral encephalitis, minocycline, neuroprotection, interleukin-1β, microglia

INTRODUCTION

Viruses of the alphavirus and flavivirus families are important causes of fatal encephalitis in humans worldwide. Most of these infections are transmitted to mammalian hosts via the bite of infected mosquito vectors. One flavivirus, West Nile virus (WNV), is newly arrived in the Western hemisphere where it has caused hundreds of cases of fatal human encephalitis over the past few years. Neurological disease caused by this pathogen occurs with a wide array of clinical features that sometimes delays a specific diagnosis. Even when recognized promptly, however, antiviral therapies have proven ineffective and treatment is supportive. Development and widespread use of an effective vaccine also remains an uncertain prospect given questions regarding the scope of this infection in coming years. Thus, unresolved issues related to WNV infection raise a number of public health concerns.

Several closely related alphaviruses also cause epidemic, mosquito-borne encephalitis in humans, and some of these pathogens can also be spread as aerosols raising concern about their use in bioterrorism. Fortunately, several alphaviruses are amenable to study in convenient and reproducible animal models. One of these viruses, Sindbis virus (SV), causes an acute encephalomyelitis in adult mice that closely reproduces many features of alphavirus infections in humans. A neuroadapted strain of SV (NSV) causes a lethal infection in susceptible hosts that evolves over a period of 7-10 days (1-3). Following direct intracerebral inoculation, NSV spreads rapidly throughout the brain and into the spinal cord where it causes a progressive lower motor neuron paralysis similar to WNV (3-5). Like other alphaviruses and flaviviruses, NSV selectively targets neurons of the CNS with no infection of glial cells (6). Neuronal fate determines outcome, with the neurovirulence of each viral strain related directly to the extent of neuronal destruction it produces (7). As an added layer of complexity, different populations of neurons undergo different types of cell death following NSV infection (4, 7), and importantly, many non-infected neurons may also be damaged via bystander mechanisms (8). This latter finding has led to the suggestion that host responses somehow contribute to the pathogenesis of NSV encephalomyelitis (9, 10), although the degree to which neuronal damage is mediated by host factors rather than by direct viral infection remains poorly understood. Still, the possibility that anti-inflammatory interventions targeting this bystander injury might be of therapeutic benefit in our model could help clarify experimental alphavirus pathogenesis and thus shed more light on related infections in humans.

The tetracycline derivative, minocycline, has been shown to attenuate disease in animal models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, hypoxic-ischemic brain injury, and multiple sclerosis (11-13). A pathological feature shared among these diverse conditions is activation of microglial cells within the CNS, and the protection conferred by minocycline against neuronal injury in some of these experimental paradigms has been linked to its capacity to block this activation process (14, 15). Previous studies have shown evidence of microglial activation in the brains of SV-infected mice (16), leading us to investigate the effects of minocycline in our lethal NSV encephalomyelitis model. Here, we report that the drug exerts substantial clinical benefit in a measurable therapeutic window, and that its mechanism of action involves blockade of local IL-1β production within the CNS. A similar form of protection is conferred by the administration of an IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra) into the CNS of NSV-infected animals, reinforcing the importance of the IL-1 pathway in disease pathogenesis. The fact that host protection can be achieved without any direct effect on CNS virus replication or spread also clarifies an important therapeutic concept in this disease. Indeed, we propose our demonstration that indirect cellular injury pathways influence disease morbidity and mortality should be explored as a pathogenic mechanism in humans with related viral infections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal Manipulations

All animal procedures had received prior approval from our institutional animal care and use committee and were performed under isoflurane anesthesia. Five to 6 week-old C57BL/6 mice were obtained from commercial suppliers (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME). To induce encephalomyelitis, animals received intracerebral inoculations of 1000 plaque-forming units of NSV into the right cerebral hemisphere in a total volume of 20 μl of PBS. For those experiments where tissue samples were not being collected for ex vivo analysis, each infected animal was scored daily by a blinded examiner into one of the following categories: a) normal or minimally affected, b) mild paralysis (some weakness of one or both hind limbs), c) moderate paralysis (weakness of one hind limb, paralysis of the other hind limb), d) severe paralysis (complete paralysis of both hind limbs), or e) dead. Animals (n=20 per group) were treated with minocycline (Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, MO) or saline given in varying doses as an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection every 12 hours starting at varying times after viral challenge. For those mice treated with intranasal (i.n.) cytokines, the methods of Liu et al. (17) and Thorne et al. (18) were adopted with minor modifications. Each animal was given 10 μg of purified recombinant murine IL-1β (n=20) (Abazyme, Needham, MA) or purified recombinant human IL-1ra (n=6) (Abazyme) in a total volume of 10 μl on a daily basis for the first 10 days of infection. Individual doses were delivered gradually into anesthetized, supine mice via a fine-tipped pipette over 1-2 minutes. These doses and dosing regimens were optimized in pilot studies using small numbers of minocycline-treated animals. The significance of survival differences between treatment groups was calculated by Kaplan-Meier analysis where noted.

Tissue Viral Titrations

To measure the amount of infectious virus present in CNS tissues, animals were perfused with PBS and brains and spinal cords were extracted, weighed, snap frozen on dry ice, and stored at –80°C until viral titration assays were performed. At the time of these assays, 10% (w/v) homogenates of each sample were prepared in PBS, and serial 10-fold dilutions of each homogenate were assayed for plaque formation on monolayers of BHK-21 cells according to a standard protocol used in our laboratory (2). The results presented are the means ± SEM of the log10 of viral plaque-forming units per gram of tissue derived from 4 animals at each time point.

Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry

Animals designated for histological analyses were sequentially perfused with chilled PBS and 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS via a transcardial approach. All tissues were post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, after which they were either cryoprotected in 30% sucrose before freezing, or embedded in paraffin for sectioning. To quantify both infected and uninfected hippocampal neurons, 25-μm coronal sections taken at –0.5 mm relative to bregma were immunostained with polyclonal rabbit anti-SV antisera to identify infected cells as described (2). Similar sections were prepared from the L4-L5 spinal level and immunostained for viral antigens to identify infected motor neurons in the lumbar spinal cord as previously reported (2, 4, 19). A blinded examiner counted the total number of infected neurons as well as the number of intact uninfected neurons at each site in each section. Brain and spinal cord sections from 3 different mice at each time point with or without minocycline treatment were examined. All cells within visualized area of the hippocampus (CA1, CA2, CA3, dentate) were counted manually in each section, and regional variability within this structure was not distinguished. Motor neurons (infected and uninfected) were defined by their location in the grey matter of the spinal cord ventral to the central canal. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of the number of infected or uninfected neurons per region. Differences in neuronal counts were analyzed using Student's t test. Significance was defined as having a p value <0.05 (noted with an *).

Apoptotic hippocampal neurons were identified by terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated nick end-labeling (TUNEL) according to a protocol established in our laboratory (7). Reagents used in these assays were obtained from Roche Applied Science (Indianapolis, IN) unless otherwise specified. Briefly, tissue sections were permeabilized in 10 μg/ml proteinase K and 0.1% Triton X-100, washed, and incubated in labeling mix (25 mM Tris-HCl, 0.2 M potassium cacodylate, 5 mM cobalt chloride, 30 U of terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase, 0.6 nmol of digoxigenin-11-dUTP, and 0.15 mM dATP) at 37°C for 60 min. The reaction was terminated by incubation in 2x SSC for 15 min at room temperature, and alkaline phosphataseconjugated anti-digoxigenin antibody (1:500) in 2% normal lamb serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) was added for an additional 30 min. The final color reaction was developed with 4-nitroblue tetrazolium chloride, 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate, and levamisole for 20-30 min, and slides were washed, dehydrated in graded alcohol washes, and mounted for histological analysis. The number of TUNEL-positive hippocampal neurons was quantified from 3 animals at each time point without or with minocycline treatment. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of the number of TUNEL-positive neurons per hippocampus.

Cryosectioned tissues were used for most other immunohistochemical staining. Brain and spinal cord sections were blocked and stained in a solution containing 2% normal goat serum (Vector) or 2% normal rabbit serum (Vector) in PBS. Polyclonal rabbit anti-SV antisera (1:100), rat anti-mouse CD45 (1:200, Serotec, Raleigh, NC), or rabbit anti-glial fibrillary acific protein (GFAP, 1:250, DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA) was then applied for 1 hour at room temperature. Control staining was performed using isotype-matched reagents of an irrelevant specificity. Staining with biotin-conjugated Lycopersicon esculentum (tomato) lectin (5 μg/ml, Sigma) was also performed to identify tissue microglial cells as described (20). After washing, biotin-labeled goat anti-rat immunoglobulin or biotin-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin secondary antibodies (1:100, Vector) were applied to the anti-SV, anti-CD45, and anti-GFAP labeled sections, and all slides were then treated with 1% hydrogen peroxide in methanol to block endogenous peroxidase. This step was followed by sequential incubations with avidin-DH-biotin complex (Vector) in PBS, and then 0.5mg/ml diaminobenzidine (Sigma) in PBS containing 0.01% hydrogen peroxide. All slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated in graded alcohol washes, mounted with glass coverslips, and counted under light microscopy. In no case did any of the control antibodies used as a primary detection reagent produce any detectable signal. The number of CD45+ microglial cells or lymphocytes or tomato lectin-positive microglial cells per cross section of lumbar spinal cord was counted from 3 animals at each time point with or without drug treatment. Differences were analyzed using Student's t test with significance again defined as having a p value <0.05 (noted with an *). Hippocampal GFAP staining was not quantified, but sections were photographed at the time points described.

Gene Array Analysis

Individual spinal cords were snap frozen and stored at –80°C until use. Tissue RNA was extracted from each sample by homogenization in TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The quality of each extract was determined by RNA Nano LabChip analysis on an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100. Processing of RNA templates for gene array analysis was then performed according to the Affymetrix GeneChip™ Expression Manual (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). First, equivalent amounts of RNA were pooled from 3 animals in each experimental group, and 7.5 μg of pooled RNA was reverse transcribed into double stranded cDNA and purified by phenol/chloroform extraction followed by ethanol precipitation. Linearly amplified complementary mRNA (cmRNA) was then synthesized from one half of this double stranded cDNA by in vitro transcription using the BioArray High Yield RNA Transcript Labeling Kit. Resultant cmRNAs were purified using the GeneChip™ Sample Cleanup Module (Affymetrix) and quantified by spectrophotometry. Fifteen μg of each cmRNA was then fragmented by metal-induced hydrolysis. Aliquots of pre- and post-fragmentation cmRNAs were again quality assessed by RNA Nano LabChip analysis on an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100. Hybridization cocktails of each sample were prepared as recommended for “standard format” arrays, including incubation at 94°C for 5 min, and then 45°C for 5 min, in a pre-programmed thermal cycler. Following centrifugation for 5 min at maximal speed, each sample was pipetted onto murine U74Av2 GeneChips™ (Affymetrix) and hybridized at 45°C for 16 hours at 60 rpm using a rotating-type hybridization oven. A signal amplification protocol for washing and staining was performed using an automated fluidics station (Affymetrix FS450) as described in the instrument's technical manual (Affymetrix). Arrays were then scanned with the GCS3000 laser scanner (Affymetrix) at an emission wavelength of 570 nm at 2.5μm resolution. The intensity of hybridization for each probe pair was computed by GCOS 1.1 software. More details surrounding these methods can be found online (http://www.malaria.mr4.org).

Primary analysis consisted of an assessment of the hybridization quality for each sample. Ratios of signal for probe sets at 5’ and 3’ regions of housekeeping genes were calculated and monitored as an indication of transcript quality. The hybridization intensity at each array site was analyzed through an expression algorithm that designated each transcript as present (P), absent (A), or marginal (M). Gene expression ratios were first calculated in extracts prepared from spinal cords derived from uninfected mice (Pool 1) versus NSV-infected/vehicle-treated animals (Pool 2). For each array site where gene expression was scored as present in both pools, we found 1,234 genes that were regulated by at least 2.5-fold during infection (909 increased, 325 decreased). Fold change values were then calculated between uninfected mice (Pool 1) and NSV-infected/minocycline-treated animals (Pool 3). Differential expression of each gene in drug-treated versus vehicle-treated samples was then calculated by dividing the individual fold change values. Using a 2.5-fold cutoff difference between the 2 groups, 456 candidate targets of minocycline were identified. A 5.0-fold cutoff difference lowered this to 109 genes, while a 10.0-fold cutoff difference left only 49 genes regulated by the drug. These 49 genes are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Genes differentially expressed more than 10-fold in the spinal cords of NSV-infected mice four days after viral challenge without or with daily minocycline treatment

| GenBank Accession Number | Fold Induction (Infection + Vehicle)* | Fold Induction (Infection + Minocycline)* | Fold Expression Difference† | Gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M20878 | 128.67 | 1.00 | 128.67 | T-cell receptor beta-chain, VDJ region |

| U56819 | 20.47 | 0.36 | 56.86 | chemokine (C-C) receptor-2 |

| AF039391 | 71.44 | 1.42 | 50.31 | mu-crystallin |

| AA647799 | 1.04 | 37.50 | 36.06 | osteoglycin |

| AJ007376 | 0.03 | 0.91 | 30.33 | DBY RNA helicase |

| M83219 | 0.14 | 4.09 | 29.21 | calgranulin B |

| AJ006584 | 0.04 | 1.16 | 29.04 | translation initiation factor eIF2 gamma Y |

| M15131 | 13.82 | 0.50 | 27.64 | interleukin-1 beta |

| AW060549 | 44.90 | 1.69 | 26.56 | NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase, MWFE subunit |

| X52643 | 56.27 | 2.12 | 26.54 | histocompatability 2, class II antigen A, alpha |

| D88899 | 38.22 | 1.48 | 25.82 | kidney-derived aspartic protease-like protein |

| X51547 | 78.51 | 3.14 | 25.01 | P lysozyme |

| AF099974 | 385.00 | 15.74 | 24.46 | schlafen 3 |

| U63146 | 0.30 | 7.16 | 23.87 | retinol binding protein 4 |

| AW047643 | 11.67 | 0.49 | 23.82 | EST†† |

| X16834 | 80.78 | 3.60 | 22.44 | Mac-2 antigen |

| AF030311 | 32.64 | 1.49 | 21.91 | killer cell lectin-like receptor, subfamily D1 |

| AI324972 | 2.33 | 46.08 | 19.78 | trans-acting transcription factor 4 |

| L13171 | 0.16 | 3.15 | 19.69 | myocyte enhancing factor 2C |

| Z22216 | 11.83 | 0.68 | 17.41 | apolipoprotein C-II |

| M83218 | 0.23 | 3.97 | 17.26 | calgranulin A |

| AF058798 | 0.13 | 2.07 | 15.92 | stratifin |

| X01973 | 0.50 | 7.93 | 15.86 | interferon alpha family, gene 4 |

| AJ009862 | 18.94 | 1.26 | 15.03 | transforming growth factor-beta 1 |

| M23158 | 23.70 | 1.58 | 15.01 | leukocyte common antigen (CD45) |

| AF068748 | 18.07 | 1.24 | 14.57 | sphingosine kinase SPHK1a |

| L38281 | 30.25 | 2.11 | 14.34 | immune-response gene 1 |

| X83106 | 13.99 | 1.00 | 13.99 | Max dimerization protein |

| X01972 | 1.19 | 16.35 | 13.74 | interferon alpha family, gene 6 |

| U51805 | 16.40 | 1.23 | 13.33 | liver arginase |

| AF011567 | 0.51 | 6.29 | 12.33 | hyaluronoglucosaminidase |

| M83649 | 33.27 | 2.73 | 12.19 | Fas antigen |

| AF067180 | 0.34 | 4.12 | 12.12 | kinesin family member 5C |

| U89906 | 0.11 | 1.24 | 11.27 | alpha-methylacyl-CoA racemase |

| AI853899 | 0.08 | 0.90 | 11.25 | placenta specific 9 |

| X04418 | 0.34 | 3.77 | 11.09 | prolactin |

| AF010405 | 0.12 | 1.28 | 10.67 | forkhead box Q1 |

| AW050185 | 0.17 | 1.81 | 10.65 | zinc finger protein 313 |

| AF087644 | 7.73 | 0.73 | 10.59 | coagulation factor X |

| D49691 | 28.16 | 2.68 | 10.51 | p50b (identical to LSP1 and pp52) |

| AA759910 | 0.08 | 0.84 | 10.51 | enhancer of yellow 2 homolog |

| M13710 | 1.10 | 11.45 | 10.41 | interferon alpha family, gene 7 |

| AA710132 | 11.51 | 3.72 | 10.40 | EST†† |

| X79003 | 38.56 | 3.72 | 10.37 | integrin alpha 5 subunit |

| AW121179 | 0.36 | 3.73 | 10.36 | microfibrillar associated protein 5 |

| M12302 | 88.87 | 8.68 | 10.24 | granzyme B |

| AF110818 | 0.13 | 1.33 | 10.23 | orphan G protein-coupled receptor FEX |

| AL078630 | 10.93 | 1.08 | 10.12 | ubiquitin B |

| AF014941 | 16.16 | 1.61 | 10.04 | lymphopain |

Relative gene expression was surveyed in tissue extracts prepared from triplicate spinal cords derived from uninfected mice (Pool 1), NSV-infected/vehicle-treated animals (Pool 2), and NSV-infected/minocycline-treated animals (Pool 3). Fold induction values (Pool 2/Pool 1, Pool 3/Pool 1) were determined for each array site where the gene was detectable in all three pools.

Differential expression of each gene in drug-treated versus vehicle-treated samples was calculated by dividing the individual fold induction values. GenBank accession numbers and gene names are shown. The genes listed in bold font are ones most likely to be expressed in cells of macrophage/microglial lineage.

EST, expressed sequence tag.

RESULTS

Minocycline Protects Susceptible Mice From Otherwise Fatal NSV Encephalomyelitis in a Defined Therapeutic Window

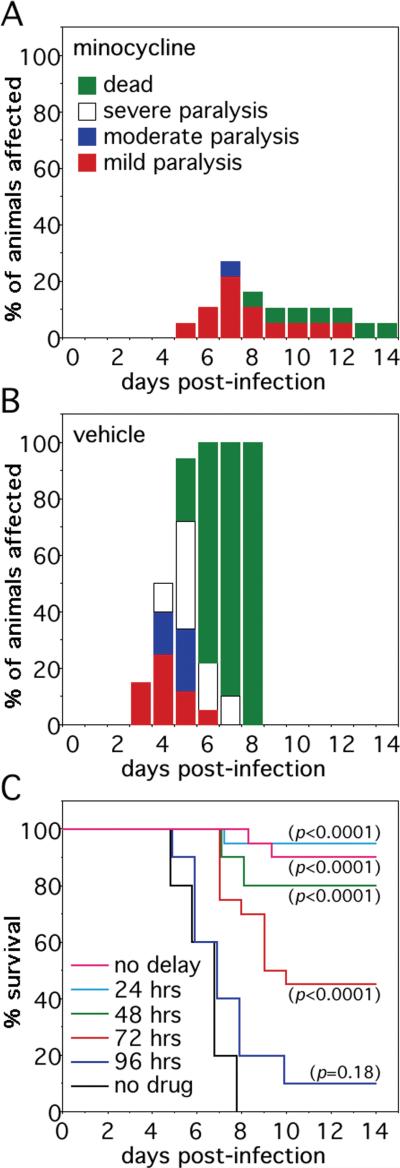

Minocycline has been shown to attenuate neuronal injury via blockade of microglial activation and to be clinically protective in animal models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, hypoxic-ischemic brain injury, and multiple sclerosis (11-15). Since histochemical evidence of microglial activation has been observed in the CNS of SV-infected animals (16), we sought to determine the effects of minocycline in our NSV model using treatment paradigms that resemble how they might be used in human alphavirus encephalomyelitis. When an optimized dose was given i.p. from the time of viral challenge, minocycline potently protected otherwise highly susceptible mice against NSV-induced disease (Fig. 1A, B). More importantly, however, partial clinical benefit was still observed even when the start of treatment was delayed following the onset of infection (Fig. 1C). Although significant protection ultimately failed when treatment was withheld more that 3 days after viral challenge, these findings demonstrate the existence of a measurable therapeutic window in which animals can be protected from what is an otherwise uniformly fatal disease.

Figure 1.

Systemic minocycline treatment protects mice from otherwise lethal NSV encephalomyelitis in a measurable therapeutic window. (A, B) Intraperitoneal minocycline (25 mg/kg/every 12 hours, n=20 per group) started at the time of viral challenge potently protected animals from both paralysis and death compared to parallel mice treated with a saline vehicle control. (C) This protective minocycline regimen exerted partial clinical protection even when the start of therapy was delayed up to 72 hours after the onset of infection (n=20 per group). The significance of survival differences between the various treatment groups and untreated controls in (C) was calculated by Kaplan-Meier analysis.

Minocycline Treatment Does Not Affect Local Virus Replication or Clearance From the CNS Even Though it Reduces the Destruction of Neurons in Defined Regions of Both the Brain and Spinal Cord

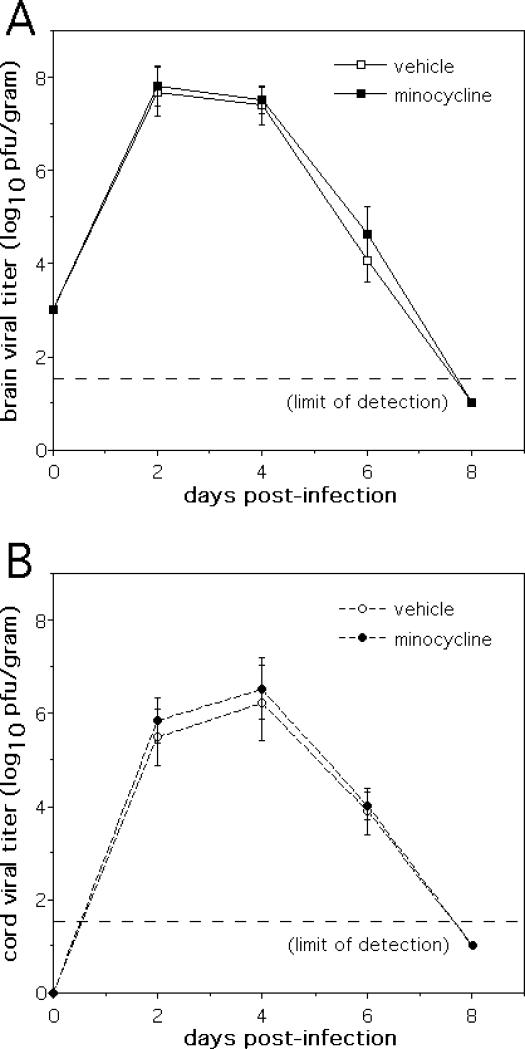

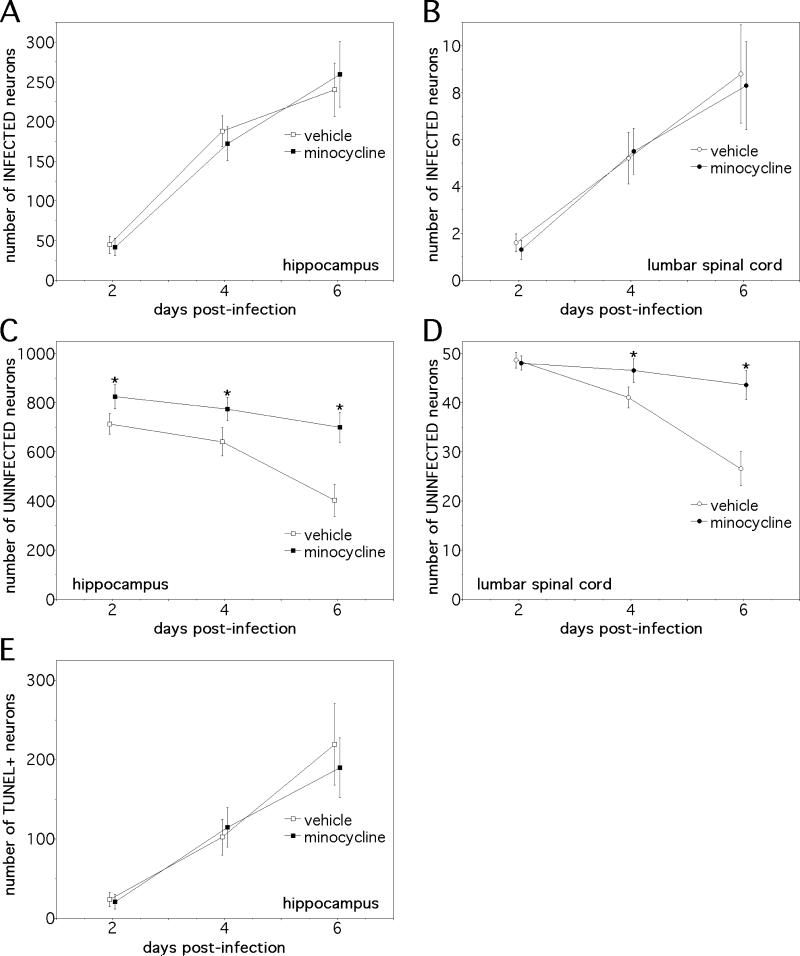

Controlled replication and clearance of virus from the CNS of SV-infected animals is mediated by the local actions of interferon and by the anti-viral antibody response (21-23). From an immunotherapeutic standpoint, the adoptive transfer of antibodies against viral glycoproteins can protect mice from the lethal effects of NSV infection by eradicating virus from the CNS (24). Given the similar clinical protection conferred by minocycline against NSV-induced paralysis and death, it was somewhat surprising to find that drug treatment had no effect on peak virus replication in the CNS, spread throughout the brain and spinal cord, or clearance from either site (Fig. 2). Furthermore, minocycline- and vehicle-treated animals had similar numbers of virus-positive neurons detected in both the hippocampus and the lumbar spinal cord (Fig. 3A, B), sites where many cells become infected (1-4, 7). No attempt to distinguish differences at the level of individual subregions within the hippocampus was made. On the other hand, consistent with its clinical protection, drug treatment reduced the destruction of uninfected neurons in both of these regions (Fig. 3C, D). Infected hippocampal neurons die primarily via apoptosis (7), and drug treatment did not alter the amount of TUNEL staining seen among these cells (Fig. 3E). Spinal motor neurons die through a non-apoptotic mechanism (2, 4), so TUNEL staining was not undertaken in spinal cord sections. Together, these data support the idea that minocycline selectively mitigates a bystander process triggered by infection that causes the non-apoptotic death of uninfected cells without having any effect on direct virus-induced cell death.

Figure 2.

Treatment of mice with a protective dose of minocycline (25 mg/kg/every 12 hours) has no effect on the replication, spread, or clearance of NSV from the CNS of infected animals. (A) Identical viral titers were found in the brains of NSV-infected mice over time without or with minocycline treatment (n=4 animals at each time point). (B) Similarly, the amount of infectious virus present in the spinal cords of NSV-infected mice showed no differences between the two treatment groups (n=4 animals at each time point).

Figure 3.

The clinical protection conferred by minocycline in NSV-infected mice is associated with reduced destruction of uninfected neurons in regions of both the brain and spinal cord where many cells become infected. (A, B) Minocycline had no effect on the numbers of infected neurons identified in either the hippocampus or the lumbar spinal cord (n=3 animals at each time point). (C, D) Drug treatment, however, reduced the loss of uninfected neurons at both of these sites (n=3 animals at each time point) (*p<0.05). (E) The same therapeutic regimen did not alter the number of TUNEL-positive hippocampal neurons over time (n=3 animals at each time point).

Minocycline Inhibits Both the Early Activation of Microglial Cells and the Later Influx of Circulating Inflammatory Cells into the CNS of NSV-Infected Animals

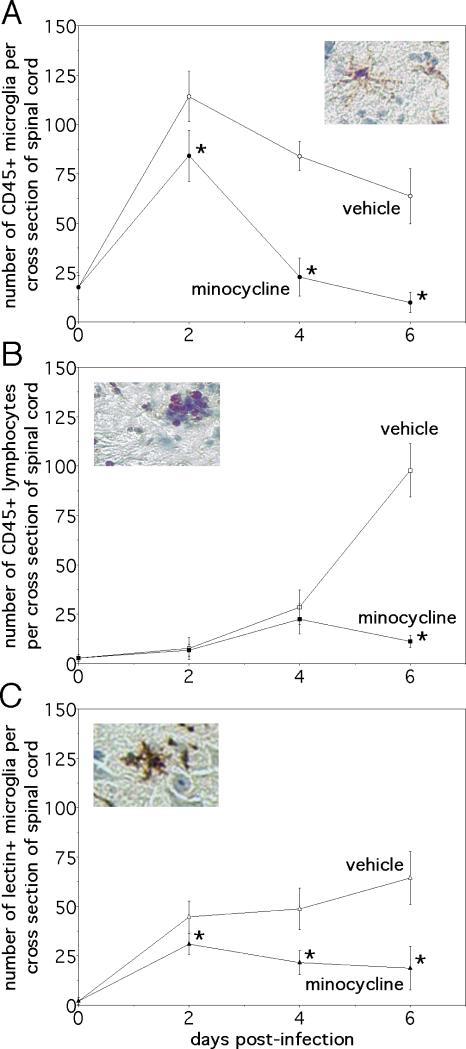

Given its known capacity to inhibit microglial activation in excitotoxicity paradigms (14, 15), immunostaining experiments sought to determine whether minocycline treatment had any effect on the phenotype of glial cells during NSV infection. CD45 (leukocyte common antigen) is a transmembrane protein tyrosine phosphatase expressed at low levels on resting microglia but rapidly induced on the surface of activated cells and implicated as a negative regulator of cytokine-receptor signaling (25, 26). In lumbar spinal cord tissue sections, daily drug treatment started at the onset of infection caused the number of CD45-positive microglial cells (Fig. 4A, insert) to revert back to baseline over a period of 4 days (Fig. 4A, graph). In contrast, equivalent numbers of round densely staining CD45-positive lymphocytes (Fig. 4B, insert) were found in the lumbar spinal cords of both vehicle- and minocycline-treated animals over this same interval (Fig. 4B, graph). Still, recruited inflammatory cells then largely disappeared from spinal cord tissue after a somewhat longer duration of treatment (Fig. 4B, graph). Immunostaining with a microglial-specific lectin that does not cross react with other leukocytes confirmed the effect of minocycline on this cell population (Fig. 4C), and staining with more specific T and B cell markers confirmed that treatment with minocycline reduced the influx of lymphocytes into the CNS, but only at later stages of infection when clinical disease was already apparent (data not shown). The drug did not alter induction of GFAP immunoreactivity in astrocytes, implying that minocycline had no direct effect on this glial cell population during NSV infection (Fig. 5A, B). Taken together, these data suggest that minocycline's primary effect is to inhibit early microglial activation in the CNS of NSV-infected animals. The drug also exerts a more delayed action on inflammatory cell recruitment, but it has no apparent impact on the reactive astrocytosis that occurs with the disease.

Figure 4.

Minocycline treatment reduces the number of CD45+ microglia and lymphocytes found in the spinal cords of mice with NSV encephalomyelitis, albeit with different kinetics. It also inhibits microglial expression of tomato lectin binding epitopes, another indicator of activation (20). (A) Fewer CD45+ microglia (identified by their morphology, see insert) were found in tissue after 2 days of drug treatment, and their numbers returned back to baseline by day 4 of infection (n=3 animals at each time point) (*p<0.05). (B) Conversely, CD45+ lymphocytes (also identified by their staining pattern, see insert) infiltrated the spinal cords of vehicle- and minocycline-treated mice over the first 4 days of infection to the same degree. By day 6, however, the total number of lymphocytes was reduced in tissue from drug-treated animals compared to vehicle-treated controls (n=3 animals at each time point) (*p<0.05). (C) Tomato lectin immunostaining (see insert) confirmed an inhibitory effect of minocycline on microglial cell activation (n=3 animals at each time point). Insert magnifications: (A) 125x; (B) 125x; (C) 125x.

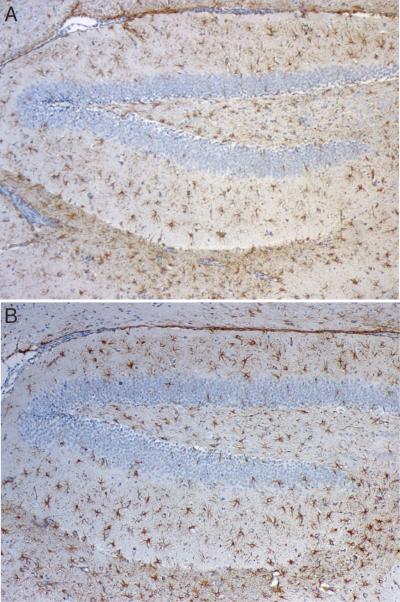

Figure 5.

Minocycline has no effect on the reactivity of astrocytes in the brain following NSV infection. (A, B) Extensive GFAP immunoreactivity is seen in the hippocampus of animals on day 6 of NSV infection; similar numbers and intensity of positive cells are seen either without (A) or with (B) daily minocycline treatment (100x).

Gene Arrays Identify Multiple Molecular Targets of Minocycline in Nervous System Tissue of NSV-Infected Animals

To characterize the local effects of minocycline at a transcriptional level, cDNA microarrays were used to survey gene expression changes directly in infected tissue samples. Lumbar spinal cord was again chosen because this anatomically defined region contains the ventral motor neurons that mediate paralysis (2-4), and because minocycline clearly has both anti-inflammatory (Fig. 4) and neuroprotective (Fig. 3D) effects at that site. Based on the highly reproducible timing of paralysis onset as well as our observed microglial staining patterns, spinal cords from vehicle- and minocycline-treated mice were collected 4 days after infection to profile against tissue samples taken from uninfected controls. Whole tissue extracts were analyzed using a commercial gene expression platform containing 12,488 individual array sites. In the absence of drug treatment, NSV infection itself caused the expression of 909 genes to increase more that 2.5-fold above baseline, while 325 genes went down more than 2.5-fold, and the remaining 11,254 genes were either not expressed in the spinal cord or changed less than 2.5-fold in either direction. When gene expression differences were compared between vehicle- and minocycline-treated animals, 49 genes were found to be differentially expressed by more than 10-fold between the two groups (Table 1). Twenty-nine of these 49 minocycline-regulated genes seemed most conceivable as products of activated microglia (Table 1, bold font), and two in particular, IL-1β and Fas, have known roles in cellular injury. As both of these potentially pathogenic genes were highly induced with infection and dampened with drug treatment (Table 1), their protein products were identified as both logical mediators of NSV pathogenesis and as the most relevant targets of minocycline in our model. These gene expression data also support our CD45 immunostaining results, as drug treatment caused a 15-fold decrease in levels of the transcripts encoding this antigen (Table 1).

Delivery of Exogenous IL-1β Directly into the CNS Overcomes the Protection Conferred by Minocycline Against NSV-Induced Paralysis and Death

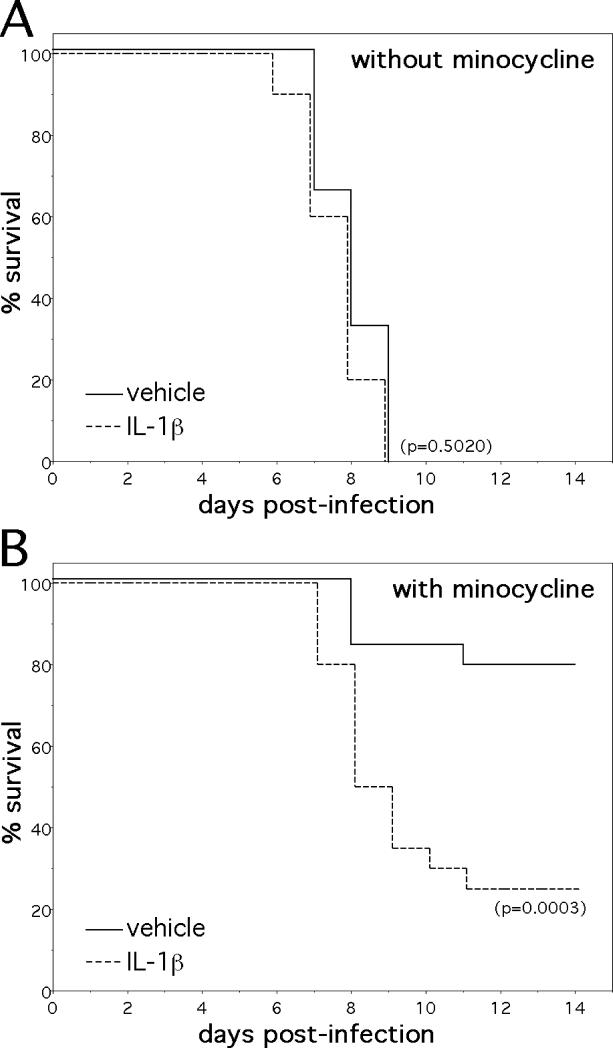

The inflammatory cytokine, IL-1β, has been implicated as a central mediator of NSV pathogenesis in an earlier study showing that IL-1β-deficient mice were highly resistant to both NSV-induced paralysis and death (9). In contrast, Fas-deficient animals were previously shown to become paralyzed and die following NSV infection to the same degree as strain-matched controls (27). Since levels of IL-1β mRNA were reduced more than 27-fold in minocycline-treated mice (Table 1), subsequent experiments sought to determine if modulated IL-1β production was an actual mechanism through which the drug conferred protection by replacing this mediator and determining the degree to which disease protection could be overcome. To accomplish such a replacement task, we adopted an i.n. administration approach used previously by others to bypass the blood-brain barrier and deliver neuroprotective growth factors to the injured CNS (17, 18). Pilot studies tested several i.n. dosing regimens in drug-treated animals until a final protocol was established. An optimized dose of 10μg/animal/day did not render NSV infection in non-minocycline-treated animals significantly more lethal (Fig. 6A), even though cerebrospinal fluid levels of this cytokine were increased more than 3-fold (data not shown). With drug treatment, however, daily i.n. IL-1β overcame much of the clinical protection previously observed (Fig. 6B). These data support our hypothesis that suppressed IL-1β production is one mechanism by which minocycline confers protection to mice from the injurious effects of NSV encephalomyelitis. They do not exclude that other neuroprotective mechanisms may be operative as well, since there are many molecular targets of minocycline in the CNS of NSV-infected animals (Table 1). While they also do not directly prove that microglia are the source of this pathogenic IL-1β, such a conclusion seems logical given the effects of minocycline on microglial activation (Fig. 4A, C), and the known capacity of these cells to be main producers of this mediator in the CNS (28, 29).

Figure 6.

The i.n. administration of recombinant IL-1β overcomes much of the protection conferred by minocycline against NSV infection. (A) Exogenous IL-1β (10 μg i.n./animal/day, n=20 animals) started at the time of infection had little effect on the survival of otherwise untreated mice (n=24 animals) infected with NSV. (B) This same i.n. IL-1β dosing regimen, however, significantly reversed the clinical protection conferred by systemic minocycline treatment. The significance of survival differences between groups was calculated by Kaplan-Meier analysis.

Intranasal Administration of IL-1ra Confirms a Role for the IL-1 Pathway in NSV Pathogenesis

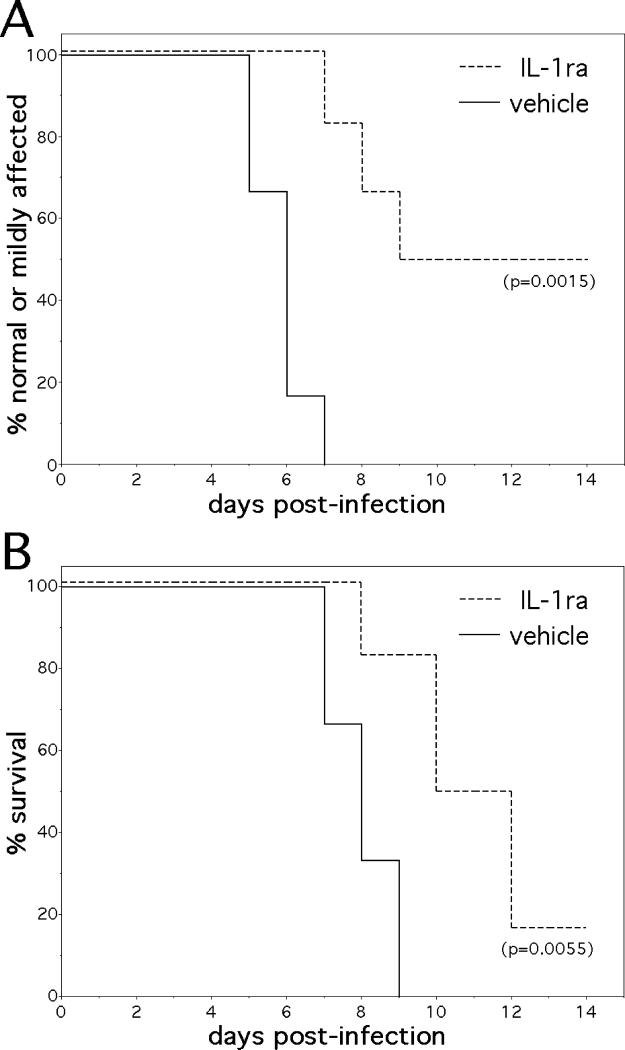

Since IL-1β-deficient mice were already known to be resistant to NSV-induced paralysis and death (9), we sought a more therapeutically relevant strategy to confirm a central role for the IL-1 pathway in this experimental model. To accomplish this task, the same i.n. approach was used in experiments where mice were treated with recombinant IL-1ra. This protein is known to reduce IL-1 activity during local and systemic inflammation in vivo (30), and it has proven clinical efficacy in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in humans (31). We found that when given on a daily basis starting at the time of viral challenge, mice treated with i.n. IL-1ra had delayed clinical disease, were less likely to develop moderate or severe paralysis, and survived longer and at a higher rate than vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 7A, B). We propose that the beneficial effects of IL-1ra in these experiments confirm a central role for the IL-1 pathway in NSV pathogenesis. They also validate the i.n. route for the delivery of therapeutic proteins into the murine CNS in a relevant alphavirus encephalitis model. Overall, we argue that such anti-inflammatory approaches elucidate neuroprotective pathways that deserve further investigation in related animal models where the virus is also a human pathogen.

Figure 7.

The exogenous administration of a specific IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra) protects mice from otherwise lethal NSV encephalomyelitis. Parallel groups of mice were treated with IL-1ra (10 μg i.n./animal/day, n=6 animals) or a saline vehicle control (n=6 animals) starting at the time of viral challenge. (A) Hind limb paralysis and (B) Survival was monitored on a daily basis over a 14-day study interval, and the significance of paralysis and survival differences between the two groups was calculated by Kaplan-Meier analysis.

DISCUSSION

The pathogenesis of SV encephalitis in mice is complex, with virus and host factors both contributing to disease outcome. Although a unifying theme in this experimental model is that virulence relates directly to the extent of neuronal destruction produced by each viral strain (7), different populations of infected cells die through multiple pathways (4, 8), and many non-infected neurons are also damaged via bystander mechanisms (8, 10). Since host responses have now been implicated in disease pathogenesis (9, 10), this raises the intriguing possibility that an appropriately targeted anti-inflammatory strategy might protect animals and their vulnerable neuronal populations regardless of whether they harbor virus or not. Here, we report that not only does minocycline protect mice from otherwise fatal NSV encephalomyelitis, but also that the inflammatory cytokine, IL-1β, is further implicated in disease pathogenesis. Our strategy of using neuroprotective agents to effectively treat these infections, even though they lack any direct antiviral effect, is also validated. Our goal is to extend these observations into other animal models of alphavirus and flavivirus infections with an eye towards eventual clinical testing in humans.

The semi-synthetic tetracycline analog, minocycline, now has a mature track record as an experimental therapeutic in neurological disease. Multiple studies have shown that the drug can protect the nervous system in animal models of stroke, multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury, Parkinson's disease, Huntington's disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (reviewed in 32). While its applicability in human neurological disease may be limited by its long-term toxicity, it has been a useful tool to study disease pathogenesis. A number of relevant mechanisms of action have been proposed, although many groups highlight the capacity of minocycline to block microglial activation as being central to its neuroprotective effect (32). While some in vivo treatment paradigms make it difficult to discriminate between a primary effect of the drug to inhibit microglial activation versus the possibility that it reduces neuronal injury via another mechanism thus causing less secondary activation of these cells, minocycline can directly inhibit the activation and proliferation of microglia in vitro (14). We have now shown that minocycline does not alter the survival of virus-infected neurons (Fig. 3A, B), and that replacement of a single inflammatory mediator whose production is inhibited by minocycline (IL-1β) largely overcomes its neuroprotective effect (Fig. 6). These findings both strengthen the idea that the drug exerts a direct anti-inflammatory action on microglial cells in our model.

We are aware of two published reports where minocycline has been shown to protect animals in experimental models of CNS viral infection. When neonatal mice were challenged with a neurotropic strain of reovirus, minocycline delayed disease onset and mortality (33). In this situation, however, it is unlikely that inflammation contributes to disease outcome in these very young hosts; rather, the data presented support the idea that the drug acts directly on neurons to inhibit their destruction (33). In a SIV-macaque model of CNS HIV infection, minocycline potently inhibited the development of CNS inflammation and to a somewhat lesser degree reduced viral load in the CNS (34). An important consideration in this paradigm is that the pathogen itself is harbored within CNS macrophages and microglia; the authors of this study hypothesized that instead of having a direct antiretroviral effect, minocycline actually altered the intracellular environment of these cells in a way that made them less permissive for viral replication (34). As NSV does not infect microglial cells, we believe our findings are most consistent with the idea that the drug acts directly on microglia to block IL-1β production that is an important effector of disease.

Other studies have shown that systemic minocycline treatment can effectively block the development of pathogenic CNS inflammation in vivo (11, 35), and we also find significantly reduced parenchymal accumulation of mononuclear cells in the CNS of infected animals treated with this drug (Fig. 4B). Although this particular anti-inflammatory effect did not obviously impact on disease symptoms (paralysis was already well underway by the time tissue inflammation was reduced), it could be of relevance to animals treated with immune serum that survive the acute disease but who undergo delayed hippocampal injury that clearly is immune-mediated (36). A similar delayed phase of disease could become apparent in humans who survive acute alphavirus or flavivirus encephalitis, given the increasing use of immunoglobulin derived from immune donors as a therapeutic approach in these diseases (37). If minocycline is capable of suppressing this pathogenic inflammation, then it could become an important adjunct to immune immunoglobulin therapy in humans. Studies to investigate the effects of minocycline in this delayed phase of NSV infection are presently underway.

Several of our most recent studies have implicated glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity in NSV pathogenesis, likely as a final common pathway of neuronal injury (19, 38). While it remains unclear what upstream events trigger such a disruption of glutamate homeostasis, there is reason to believe that host immune responses are involved (9, 10). We have found an important defect that develops in the spinal cords of NSV-infected animals relates to a focal loss of a critical glutamate reuptake protein (38), thereby predisposing local tissues to higher local extracellular glutamate levels and subsequent excitotoxic neuronal injury. Other groups have identified a similar loss of glutamate transporter expression in active multiple sclerosis lesions, a finding that correlates with both oligodendrocyte and axonal damage (39). Here, a soluble inflammatory mediator was hypothesized to be driving this glutamate transporter loss (39), and we have now observed that IL-1β-deficient mice do not develop this loss of glutamate transporter expression in the spinal cord following NSV challenge (N. Prow and D. Irani, unpublished observations). Importantly, treatment with minocycline also blocks this loss of glutamate transporters in the spinal cords of NSV-infected animals (38), and given the effects of the drug on local IL-1β expression (Table 1), these findings together strongly implicate this mediator in disrupting glutamate homeostasis. If more consistent experimental links between local innate immune responses and glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity are established in this and other models, then new therapeutic avenues could be opened for the treatment of other neurodegenerative disorders believed to involve disrupted glutamate homeostasis. Ironically, other antimicrobial agents have recently been shown to offer neuroprotection by actually increasing glutamate transporter expression (40).

In conclusion, we find that minocycline confers potent protection against both paralysis and death in a murine model of mosquito-borne viral encephalomyelitis, even when started well after viral challenge and despite having no effect on CNS viral replication or spread. Further studies demonstrate that virus-induced microglial activation is inhibited by the drug, and that diminished production of the pro-inflammatory mediator, IL-1β, appears to be responsible for its protective effect. We propose neuroprotective interventions such as minocycline that target these detrimental host responses arising from activated microglia could be of therapeutic benefit in humans with encephalitis caused by related mosquito-borne viruses. We also suggest these innate host responses activate a cascade of neurodegenerative events that clarifies the pathogenesis of these life-threatening infections.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are indebted to Alan Scott and Anne Jedlicka in the Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute Gene Array Core Facility for assistance in performing and analyzing our microarray experiments.

This work was supported by grants from the Robert Packard Center for ALS Research at Johns Hopkins (DNI), from the Charles A. Dana Foundation (DNI), and by NIH grant AI057505 (DNI).

REFERENCES

- 1.Jackson AC, Moench TR, Trapp BD, et al. Basis of neurovirulence in Sindbis virus encephalomyelitis of mice. Lab Invest. 1988;58:503–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kerr DA, Larsen T, Cook SH, et al. BCL-2 and BAX protect adult mice from lethal neuroadapted Sindbis virus infection but do not protect spinal cord motor neurons or prevent paralysis. J Virol. 2002;76:10393–10400. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.20.10393-10400.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson AC, Moench TR, Griffin DE, et al. The pathogenesis of spinal cord involvement in the encephalomyelitis of mice caused by neuroadapted Sindbis virus infection. Lab Invest. 1987;56:418–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Havert MB, Schofield B, Griffin DE, et al. Activation of divergent neuronal cell death pathways in different target cell populations during neuroadapted Sindbis virus infection of mice. J Virol. 2000;74:5352–5356. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.11.5352-5356.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelley TW, Prayson RA, Isada CM. Spinal cord disease in West Nile Virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:564–566. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200302063480618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson RT, McFarland HF, Levy SE. Age-dependent resistance to viral encephalitis: studies of infections due to Sindbis virus in mice. J Infect Dis. 1972;125:257–262. doi: 10.1093/infdis/125.3.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis J, Wesselingh SL, Griffin DE, et al. Alphavirus-induced apoptosis in mouse brains correlates with neurovirulence. J Virol. 1996;70:1828–1835. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1828-1835.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nargi-Aizenman JL, Griffin DE. Sindbis virus-induced neuronal cell death is both necrotic and apoptotic and is ameliorated by N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists. J Virol. 2001;75:7114–7121. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.15.7114-7121.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liang XH, Goldman JE, Jiang HH, et al. Resistance of interleukin-1ß-deficient mice to fatal Sindbis virus encephalitis. J Virol. 1999;73:2563–2567. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.2563-2567.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimura T, Griffin DE. The role of CD8+ T cells and major histocompatibility complex class I expression in the central nervous system of mice infected with neurovirulent Sindbis virus. J Virol. 2000;74:6117–6125. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.13.6117-6125.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Popovic N, Schubart A, Goetz BD, et al. Inhibition of autoimmune encephalomyelitis by a tetracycline. Ann Neurol. 2002;51:215–223. doi: 10.1002/ana.10092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu S, Stavrovskaya IG, Drozda M, et al. Minocycline inhibits cytochrome C release and delays progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in mice. Nature. 2002;417:74–78. doi: 10.1038/417074a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arvin KL, Han BH, Du Y, et al. Minocycline markedly protects the neonatal brain against hypoxic-ischemic injury. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:54–61. doi: 10.1002/ana.10242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tikka T, Fiebich BL, Goldsteins G, et al. Minocycline, a tetracycline derivative, is neuroprotective against excitotoxicity by inhibiting the activation and proliferation of microglia. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2580–2588. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-08-02580.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tikka TM, Koistinaho JE. Minocycline provides neuroprotection against N-methyl-D-aspartate neurotoxicity by inhibiting microglia. J Immunol. 2001;166:7527–7533. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tyor WR, Stoll G, Griffin DE. The characterization of Ia expression during Sindbis virus encephalitis in normal and atymic nude mice. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1990;49:21–30. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199001000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu XF, Fawcett JR, Thorne RG, et al. Intranasal administration of insulin-like growth factor-1 bypasses the blood-brain barrier and protects against focal cerebral ischemic damage. J Neurol Sci. 2001;187:91–97. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(01)00532-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thorne RG, Pronk GJ, Padmanabhan V, et al. Delivery of insulin-like growth factor-1 to the rat brain and spinal cord along olfactory and trigeminal pathways following intranasal administration. Neuroscience. 2004;127:481–496. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nargi-Aizenman JL, Havert MB, Zhang M, et al. Neural degeneration, paralysis and death due to acute viral encephalomyelitis are prevented by glutamate receptor antagonists. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:541–549. doi: 10.1002/ana.20033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Acarin L, Vela JM, Gonzalez B, et al. Demonstration of poly-N-acetyl lactosamine residues in ameboid and ramified microglial cells in rat brain by tomato lectin binding. J Histochem Cytochem. 1994;42:1033–1041. doi: 10.1177/42.8.8027523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levine B, Hardwick JM, Trapp BD, et al. Antibody-mediated clearance of alphavirus infection from neurons. Science. 1991;254:856–860. doi: 10.1126/science.1658936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Byrnes AP, Durbin JE, Griffin DE. Control of Sindbis virus infection by antibody in interferon-deficient animals. J Virol. 2000;74:3905–3908. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.8.3905-3908.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Binder GK, Griffin DE. Interferon-gamma-mediated site-specific clearance of alphavirus from CNS neurons. Science. 2001;293:303–306. doi: 10.1126/science.1059742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stanley J, Cooper SJ, Griffin DE. Monoclonal antibody cure and prophylaxis of lethal Sindbis virus encephalitis in mice. J Virol. 1986;58:107–115. doi: 10.1128/jvi.58.1.107-115.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan J, Town T, Mullan M. CD45 inhibits CD40L-induced microglial activation via negative regulation of the Src/p44/42 MAPK pathway. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37224–37231. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002006200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Penninger JM, Irie-Sasaki J, Sasaki T, et al. CD45: new jobs for an old acquaintance. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:389–396. doi: 10.1038/87687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rowell JF, Griffin DE. Contribution of T cells to mortality in neurovirulent Sindbis virus encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol. 2002;127:106–114. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00108-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woodroofe MN, Sarna GS, Wadhwa M, et al. Detection of interleukin-1 and interleukin-6 in adult rat brain following mechanical injury by in vivo microdialysis: evidence of a role for microglia in cytokine production. J Neuroimmunol. 1991;33:227–236. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(91)90110-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murphy GM, Yang L, Cordell B. Macrophage colony-stimulating factor augments beta-amyloid-induced interleukin-1, interleukin-6, and nitric oxide production by microglial cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20967–20971. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.20967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dinarello CA. Therapeutic strategies to reduce IL-1 activity in treating local and systemic inflammation. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2004;4:378–385. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Furst DE. Anakinra: a review of recombinant human interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Ther. 2004;26:1960–1975. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2004.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yong VW, Wells J, Giuliani F, et al. The promise of minocycline in neurology. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:744–751. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00937-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richardson-Burns S, Tyler KL. Minocycline delays disease onset and mortality in reovirus encephalitis. Exp Neurol. 2005;192:331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zink MC, Uhrlaub J, DeWitt J, et al. Neuroprotective and anti-human immunodeficiency virus activity of minocycline. JAMA. 2005;293:2003–2011. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.16.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brundala V, Rewcastle NB, Metz LM, et al. Targeting leukocyte MMPs and transmigration: Minocycline as a potential therapy for multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2002;125:1297–1308. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kimura T, Griffin DE. Extensive immune-mediated hippocampal damage in mice surviving infection with neuroadapted Sindbis virus. Virology. 2003;311:28–39. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Granwehr BP, Lillibridge KM, Higgs S, et al. West Nile virus: where are we now? Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4:547–556. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Darman JS, Backovic S, Dike S, et al. Viral-induced spinal motor neuron death is non cell-autonomous and involves glutamate excitoxicity. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7566–7575. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2002-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Werner P, Pitt D, Raine CS. Multiple sclerosis: altered glutamate homeostasis in lesions correlates with oligodendrocyte and axonal damage. Ann Neurol. 2001;50:169–180. doi: 10.1002/ana.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rothstein JD, Patel S, Regan MR, et al. Beta-lactam antibiotics offer neuroprotection by increasing glutamate transporter expression. Nature. 2005;433:73–77. doi: 10.1038/nature03180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]