Abstract

Background

In Brazil coronary heart disease (CHD) constitutes the most important cause of death in both sexes in all the regions of the country and interestingly, the difference between the sexes in the CHD mortality rates is one of the smallest in the world because of high rates among women. Since a question has been raised about whether or how the incidence of several CHD risk factors differs between the sexes in Brazil the prevalence of various risk factors for CHD such as high blood cholesterol, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity, sedentary lifestyle and cigarette smoking was compared between the sexes in a Brazilian population; also the relationships between blood cholesterol and the other risk factors were evaluated.

Results

The population presented high frequencies of all the risk factors evaluated. High blood cholesterol (CHOL) and hypertension were more prevalent among women as compared to men. Hypertension, diabetes and smoking showed equal or higher prevalence in women in pre-menopausal ages as compared to men. Obesity and physical inactivity were equally prevalent in both sexes respectively in the postmenopausal age group and at all ages. CHOL was associated with BMI, sex, age, hypertension and physical inactivity.

Conclusions

In this population the high prevalence of the CHD risk factors indicated that there is an urgent need for its control; the higher or equal prevalences of several risk factors in women could in part explain the high rates of mortality from CHD in females as compared to males.

Background

Men and women share some coronary heart disease (CHD) risk factors such as age, dyslipidemia, hypertension, smoking, diabetes, obesity and physical inactivity. Besides that, women have additional risk factors, such as the use of contraceptives and the reduction of ovarian function with age [1].

There are important differences in the clinical manifestations of CHD between the sexes [1-7]. Besides that CHD was always considered a male problem, partly because of the 7-10 years time lag before its clinical appearance in women due to hormone differences and partly because of its higher incidence in men (although the difference decreases in postmenopausal women). After the sixties, with the entry of women into the labor market and exposure to stress, habitual smoking and fast food diets, their CHD mortality rates quickly increased. Recent studies have emphasized this increase and the fact that CHD is the leading cause of death among women [1-8]. Besides this, in the last 2 to 3 decades, the decrease in cardiovascular mortality rates as well as in the incidence of risk factors has been shown to be larger in men than in women [9].

In Brazil, the CHD mortality rate in women jumped from 10 to 25% from the sixties to the seventies [10-12] and now CHD constitutes the most important cause of death in both sexes and in all the regions of the country.

Interestingly, in Brazil the difference between the sexes in the CHD mortality rates is one of the smallest in the world because of high rates among women [13]. Since a question has been raised about whether or how the incidence of several CHD risk factors differs between the sexes in Brazil, we evaluated data on the occurrence of these risk factors in a population from the city of Campinas, State of São Paulo. We also measured the influence of the CHD risk factors on blood cholesterol.

Materials and Methods

The study comprised eight hundred and seventy-three individuals who volunteered to have their total blood cholesterol (CHOL) measured and to fill in a questionnaire with information on anthropometric data and on the presence of the following risk factors for the development of CHD: diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension (HY), obesity (OBES), sedentary lifestyle (SEDEN) and cigarette smoking (SMOK). The data were collected in four different places of the city of Campinas, São Paulo, representing different social-economic populations - the City Government building, a branch of the Bank of Brazil, the State University of Campinas and a large Shopping Center - over a seven-day period, in november 1997. The volunteers were adults, from 20 to 82 years of age (y), 53% males (M) and 47% females (W), 6% blacks and 94% non-blacks mainly "Hispanics", similar frequencies described for the country and the state of São Paulo according to the 1998 census data. Their CHOL was measured in fingertip capillary blood by an enzymatic method (CHOD-PAP) through reflectance photometry utilizing the Reflotron (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Body mass indexes (BMI) were calculated from the informed height and weight (kg)/height(m2) and used as a marker of excessive weight and obesity when equal to or above 25 kg/m2.

The data were analyzed by the SAS statistical package utilizing the tests Student's "t", Chi-Square with or without Fleiss's method [14] and Fisher's exact, all at the significance level of 5%. Comparisons were made between the sexes in the total population and at different age groups and between the age sub-groups in each sex. The cut off ages for CHD risk were established as: ≥ 45 versus <45 y for men, and ≥ 55 versus <55 y for women, according to the United States National Cholesterol Expert Panel" (NCEP) [15] recommendations followed by the "2° Consenso Brasileiro de Dislipidemias" (Brazilian Consensus on Dyslipidemia) [16].

A multiple logistic regression analysis was used to assess the influence of CHD risk factors on blood cholesterol concentration. The independent predictors of blood cholesterol were sex (men/women); age - all ages and the age group: ≥ 50 versus <50 y; BMI ≥ 25 versus <25 kg/m2; race (blacks versus non-blacks) and the binary criteria (yes/no) of diabetes, hypertension, sedentary lifestyle and cigarette smoking. The dependable variable was defined as CHOL<5.18-desirable levels, 5.18-6.19-borderline risk for CHD and ≥ 6.22 mmol/L- high risk for CHD, according to NCEP recommendations followed by the "2° Consenso Brasileiro de Dislipidemias" (Brazilian Consensus on Dyslipidemia) [15,16]. In this case, since we have three levels of cholesterol, a proportional odds model was used in the logistic regression.

Results

In this population women had a trend toward higher ages than men did (p = 0.052), as seen in Table 1. The BMI for the whole population is in the limit range for obesity grade I (24.97 ± 3.80 Kg/m2). In men it was significantly higher than in women but the average difference between the sexes was only 3% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Blood cholesterol and anthropometric data among men and women and in the total population. Data presented as mean ±SD, interval, (n = number of subjects)

| VARIABLE | MEN | WOMEN | TOTAL |

| CHOL | 4.92 ± 1.09 a | 5.10 ± 1.22 a | 5.00+1.22 |

| (mmol/L) | 2.33-9.04 | 2.67-9.14 | 2.33-9.14 |

| (459) | (410) | (869) | |

| AGE | 46 ± 15 | 50 ± 15 | 47+15 |

| (y) | 20-82 | 20-81 | 20-82 |

| (462) | (411) | (873) | |

| BMI | 25.31 + 3.50b | 24.59 ± 4.00 b | 24.97+3.80 |

| (kg/m2) | 15.6-41.1 | 16.7-38.9 | 15.6-41.1 |

| (454) | (403) | (857) |

Student's "t" test; axa: p = 0.033, bxb: p = 0.005

The population average CHOL (mean ± SD) was 5.00 ± 1.22 mmol/L. Women showed statistically significant higher CHOL when compared to men, although the difference was small, around 3.5% (Table 1). This sex difference was found in the CHD risk age groups: 5.75 ± 1.14 (age ≥ 55 y, women) versus 5.23 ± 1.19 mmol/L (age ≥ 45 y, men, "t" test, p = 0.001). There was no difference in the younger age groups: 4.66 ± 1.09 (age 20-54 y, women) versus 4.64 ± 1.11 mmol/L (age 20-44 y, men, "t" test, p = 0.630). Postmenopausal women presented higher CHOL levels when compared with younger women: 5.75 ± 1.14 versus 4.66 ± 1.09 mmol/L (p = 0.001) and in men CHOL also increased with age: 5.23 ± 1.19 versus 4.64 ± 1.11 mmol/L (p = 0.001) as expected.

Table 2 shows that CHOL was higher than the recommended values for adults in 41% of the population. We found fewer women with CHOL in the reference range than men (54 versus 63%). This statistically significant difference was due to the sub-population of women in the age group equal to and above 55 y (p= 0.001, Chi-square as expected [4,7,17].

Table 2.

Percentage distribution of different levels of total blood cholesterol between the sexes by age

| GROUP | AGE | <5.18 | 5.18-6.19 | ≥ 6.22 | |

| (years) | (mmol/L) | (mmol/L) | (mmol/L) | ||

| MEN | (462) | 63 (290)a | 23 (106) | 14 (66) | |

| <45 | 61 | 40 | 32 | ||

| ≥ 45 | 39 b | 60 | 68 | ||

| WOMEN | (411) | 54 (222)a | 28(114) | 18 (15) | |

| <55 | 80 | 45 | 31 | ||

| ≥ 55 | 20 b | 55 | 69 | ||

| TOTAL | (873) | 59 (512) | 25 (220) | 16 (141) |

()=number of subjects; Chi-square and Fleiss tests : axa: p = 0.030; bxb: p = 0.001

As seen in Table 3, obesity (44%) and sedentary lifestyle (48%) were the most common risk factors in this population and diabetes the least common (4%, as expected), but the data do not differ from those found in developed countries. Hypertension and smoking habit had practically the same frequencies around 20%. Among men, in decreasing order of frequencies, the data showed: obesity, sedentary lifestyle, smoking, hypertension and diabetes. Among women, however, the decreasing sequence was different: sedentary lifestyle, obesity, hypertension, smoking and diabetes.

Table 3.

Prevalence (%) of risk factors for coronary heart disease among men and women and in the total population

| GROUP | DM | HY | OBES | SEDEN | SMOK |

| MEN | 3 (460) | 19a(456) | 48 b(462) | 46 (461) | 24 c(461) |

| WOMEN | 4 (411) | 27a(410) | 39 b(411) | 52 (410) | 18 c(410) |

| TOTAL | 4 (871) | 23 (866) | 44 (873) | 49 (871) | 21 (871) |

()=number of subjects; Chi-Square test; axa: p = 0.003,bxb: p = 0.009; cxc: p = 0.029 DM-diabetes; HY- hypertension; OBES- obesity; SEDEN- physical inactivity; SMOK- smoking

The comparison between the sexes showed that there were significant statistical differences in the frequencies of hypertension (1.4 times higher in women), obesity and smoking (respectively 1.2 and 1.3 times higher in men). Physical inactivity, the most frequent risk factor in this population, and diabetes were similar in the sexes.

Table 4 shows age distribution of risk factors in both sexes. Diabetes was not present in younger men. Its prevalence did not differ between the group ages in women. In the older groups, no differences were found between the sexes. Women presented higher frequencies of hypertension than men did in both age groups, indeed twice as high in the younger group (8X18%). In both sexes the prevalence of hypertension was 2 to 3.5 times higher in the older ages as compared to the younger. The distribution of obesity between the age groups was not different in men, but in women the frequency was higher in older ages. In men the prevalence was higher than in women only in the younger group and no differences were found among the older groups. Physical inactivity was the only risk factor similar between the sexes in both age groups and equally frequent in the two age groups. The higher prevalence of smoking in men was found only in the older group. It was high in the younger groups and there were no differences between the sexes in those age groups (29 versus 26%). Younger women smoked 4 times more than the older ones and younger men 1.6 times more.

Table 4.

Prevalence (%) of risk factors for coronary heart disease according to sex and age

| GROUP | AGE(y) | DM | HY | OBES | SEDEN | SMOK |

| MEN | <45 | 0 a | 8 b | 46c | 42 | 29 d |

| (239) | (238) | (241) | (240) | (240) | ||

| ≥ 45 | 7e | 30f | 51 | 50 | 18 g | |

| (221) | (218) | (221) | (221) | (221) | ||

| WOMEN | <55 | 3 h | 18 i | 33 j | 50 | 26 k |

| (251) | (251) | (251) | (250) | (250) | ||

| ≥ 55 | 6l | 41m | 50n | 56 | 6° | |

| (160) | (159) | (160) | (160) | (160) |

Statistical comparisons by the Fischer test; axe: p = 0.001, axh: p = 0.007; by the Chi-Square test; bxf, ixm,jxn, kxo, gxo: p = 0.001; dxg: p = 0.005; bxi, cxj: p = 0.020; fxm = 0.019 DM-diabetes; HY-hypertension; OBES-obesity; SEDEN-physical inactivity; SMOK-smoking

Race, presence of diabetes and smoking habit did not have any significant effects in CHOL in this population as shown by the logistic univariate regression analysis. According to the multiple regression analysis, sex, age and BMI, the most significant effects to the model, did influence CHOL and were associated with hypertension and physical inactivity; because of the high association with BMI, they were not significant to the model in the presence of this variable. In the final model, age and sex presented a very significant interaction at all ages. Also BMI and sex interacted significantly at and after age 50 y. Table 5 presents the results of the logistic regression analysis with the selected test variables associated with CHOL-sex, age, BMI- and their respective logistic coefficients, SE, p-value, odds ratios and confidence intervals in the total population. In Table 6 the same associations between variables for the cut off age of 50 y are shown.

Table 5.

Influence of coronary heart disease risk factors on blood cholesterol in the total population

| VARIABLE | LOGISTIC | SE | p-VALUE | ODDS RATIO a | 95% CI |

| COEFFICIENT | |||||

| SEX | 1.655 | 0.534 | 0.002 | 5.232 | 1.839; 14.885 |

| AGEb,c | 0.075 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 1.078 | 1.061; 1.095 |

| BMI | 0.208 | 0.141 | 0.141 | 1.231 | 0.933; 1.624 |

| AGE*SEX | -0.039 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.962 | 0.943; 0.981 |

a = odds ratio = esum of logistic coefficients X age; CHOL above 6.22 mmol/L; b = all ages; c = <25 and ≥ 25 kg/m2; CI = confidence interval

Table 6.

Influence of coronary heart disease risk factors on blood cholesterol by age

| VARIABLES | LOGISTIC | SE | p-VALUE | ODDS RATIO a | 95% CI |

| COEFFICIENT | |||||

| SEX | 0.195 | 0.211 | 0.355 | 1.215 | 0.804; 1.836 |

| AGE 50 b | 2.074 | 0.243 | 0.009 | 7.961 | 4.946; 12.813 |

| BMI c | 0.576 | 0.207 | 0.005 | 1.778 | 1.185; 2.668 |

| AGE 50*SEX | - 0.953 | 0.285 | 0.001 | 0.386 | 0.221; 0.674 |

| AGE 50*BMI | -0.551 | 0.281 | 0.050 | 0.576 | 0.332; 1.000 |

a = odds ratio = esum of logistic coefficients; CHOL above 6.22 mmol/L; b = by age group (<50 and ≥ 50 y); c = <25 and ≥ 25 kg/m2; CI = confidence interval

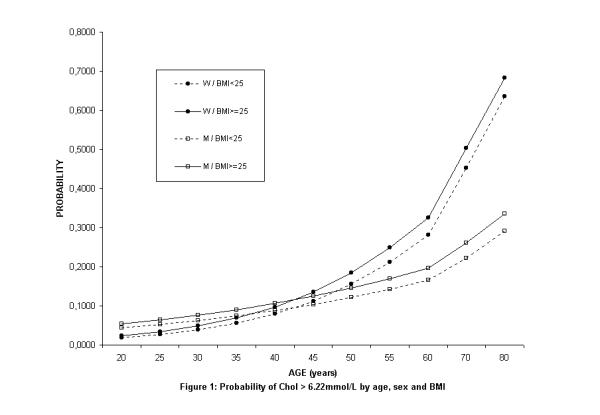

Figure 1 summarizes the changes of prevalence of CHOL above 6.22 mmol/L according to sex, age (all ages up to 80 y) and BMI.

Figure 1.

Probability of CHOL > 6.22 mmol/dL by age, sex and BMI.

Discussion

The literature shows that there are differences between the sexes in the prevalence and impact of CHD risk factors [2,9,18]. In the U.S.A. for example, some risk factors have high prevalence among women in the 20 to 74 year age group [19]: more than 1/3 have hypertension, more than 1/4 are hypercholesterolemic, more than 1/4 present excessive weight and more than 1/4 are sedentary. Furthermore, 51% of white women and 79% of black women above 45 y have hypertension. The same is true for 71% of all women over 65 y [3]. Hypertension is more frequent among women over 65 y than among men at that age [20]. Diabetes has a prevalence of 7.7% [21].

In Brazil, the studies indicate the following prevalence [12]: hypercholesterolemia not determined [21], but more recently described in one study as 41% [22]; hypertension equal to 20-30% [23], excessive weight and obesity, 53% [21], physical inactivity, 74% [21], diabetes, 7% [21] and smoking habit, 63% [21].

The data presented here confirm the fact that the presence of CHD risk factors is a major health problem in women in Brazil (Table 3). Our findings of a lower prevalence of diabetes (4%), excessive weight and obesity (44%), physical inactivity (49%) and smoking (21%) in this study can be partially related to the fact that the information was self-reported although high CHOL and hypertension frequencies are the same as the ones described in the literature [22,23].

It is important to emphasize that two of the major risk factors for CHD, high CHOL (Table 2) and hypertension (Table 3) were more prevalent among women as compared to men. High CHOL was present in the sub-population of women in the postmenopausal age, as expected, but pre-menopausal women in this population presented equal levels of CHOL when compared to men suggesting an additional risk at pre-menopausal ages.

Several studies demonstrate that the HDL-cholesterol level is a better predictor of mortality from CHD in women while the LDL-cholesterol level is a better predictive in men [2,3]. We did not fractionate lipoproteins in this study, but since hypercholesterolemia is one of the major well established risk factors for CHD in both sexes [1,4], we can speculate that this could account for a possible higher risk for CHD in women in this population. Postmenopausal women tend to present a much higher chance of hypercholesterolemia due to elevated LDL- cholesterol levels [17].

In Table 4 it is seen that the higher frequency of hypertension was present in both age groups. The higher frequency in postmenopausal women is in accord with the literature [24] but hypertension was also two times higher in younger women as compared to men from ages 20 to 44 y. Again, younger women in this population are more exposed to this major risk factor.

Hypertension is a well-established risk factor in both sexes. On the other hand, women have more complications from hypertension than men do. A more recent work has shown a strong association between CHD and hypertension in women [20].

The prevalence of diabetes was not different between the sexes (Table 3), but diabetes was not present in the younger group of men in this study, only in the women's group, indicating the presence of another very relevant risk factor in younger women. No differences were found between the sexes in the older groups (Table 4).

Diabetic women lose their "relative immunity" to CHD in relation to men: female diabetics are two times as likely to die from CHD than are male diabetics, so the same or a higher prevalence of diabetes among the sexes found in this study is quite unfavorable to women [7].

The prevalence of sedentary lifestyle was not different between men and women, but showed a small trend to higher frequencies in women (Table 4).

Physical inactivity increases CHD in both sexes [8]. Regular physical exercise favors women more than men, with respect to CHD [25].

Men presented a higher prevalence of obesity than women did only in the younger group, but there were no differences in the older age groups. The prevalence increased with age only in women aggregating another risk factor to the postmenopausal period.

Obesity was found to be an independent predictor of CHD in both men and women [26,27]. The distribution of fat is considered to be more important in both sexes than the overall degree of obesity, the centripetal distribution being a component of the atherogenic syndrome X [9,24,28].

Smoking, very prevalent in the younger groups, had higher incidence in men (Tables. 3, 4). There were no differences between the sexes in the younger age groups leading to another undesirable risk at younger ages in women.

Tobacco use triples the risk of heart attacks among women, even during the pre-menopause period [3]; also, smoking women who are diabetic double their risk of death in relation to diabetic non-smokers [2]. Men are giving up tobacco at an increasing rate, which is not the case among women [21]. Also smokers have their first heart attack earlier than non-smokers: women 19 and men 7 years earlier [2].

The logistic analysis indicates that race, presence of diabetes and smoking habit did not contribute to CHOL in this population. It is probable that these risk factors do not operate through high CHOL. On the other hand, sex, age, BMI, as described earlier in other studies [4,29], hypertension and physical inactivity were the risk factors that influenced CHOL. Since sex and age are not modifiable, the control of obesity should be seriously implemented in Brazil.

Women had a higher risk than men of having CHOL >6.22 mmol/L as their age increased (Table 5). These findings are in accord with the literature [4,7] and in fact the population CHOL seemed similar to data obtained from an N.I.H. report [31]. From Table 5 it can be observed that the chance of having CHOL ≥ 6.22 mmol/L was 23% higher in individuals presenting overweight and obesity. A more detailed analysis of these effects of sex, age and BMI on CHOL is seen in Figure 1. The prevalence of high CHOL was higher in post-menopausal women as compared to men, and it increased for both with age. The sex difference was present at all ages (up to 80 y), men having a higher prevalence in younger ages. After age 60 y, women presented a much higher frequency than men. The curves crossed around the age of 42.5 y (close to the age of menopause, 47.5 y as determined in the State of São Paulo [31]) for either overweight and obese individuals or not. The higher BMI is associated with a higher prevalence of CHOL.

Analyzing Table 6, in women at and above 50 y the risk of having CHOL >6.22 mmol/L was 2 times higher than for men; before 50 y men had a 20% higher chance than women; at and above age 50 y the chance of high CHOL for BMI<25 is 1.02 as compared to BMI ≥ 25; below 50 y the chance of high CHOL for BMI ≥ 25 is 1.8 higher than for BMI below 25, showing that factors related to obesity are much less influential in older ages, a period when the interaction age/sex predominated.

The results of this study demonstrate the need for the prevention of atherosclerosis by controlling the CHD risk factors in Brazil. This is shown by the high frequencies of a conglomerate of these risk factors such as high CHOL, obesity, sedentary lifestyle, hypertension, diabetes and smoking in this population. Very important also is the fact that hypertension, diabetes and smoking were highly prevalent among younger women, the two first having higher frequencies than among men. These results could partially explain the small difference in the mortality rates from CHD between the sexes in Brazil [12].

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/backmatter/1471-2458-1-3-b1.pdf

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Merck Sharp & Dohme, Brazil, for their technical support to carry out this study.

Contributor Information

Vera S Castanho, Email: vera@hotmail.com.

Letícia S Oliveira, Email: evillady@hotmail.com.

Hildete P Pinheiro, Email: ildete@ime.unicamp.br.

Helena CF Oliveira, Email: ho98@unicamp.br.

Eliana C de Faria, Email: cotta@fcm.unicamp.br.

References

- Bush TL, Fried LP, Connor-Barret E. Cholesterol, lipoproteins, and coronary heart disease in women, Clin Chem. 1988;34(8B):B60–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judelson DR. Coronary heart disease in women: risk factors and prevention. J Am Med Women Assoc. 1994;49(6):186–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger NK. Hypertension and other cardiovascular risk factors in women. Am J Hyperten. 1995;8:94S–99S. doi: 10.1016/0895-7061(95)99306-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelli WP. Lipids, risk factors and ischaemic heart disease. Atherosclerosis. 1996;124 Suppl:Sl–S9. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(96)05851-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass KM, Newschaffer JC, Klag MJ, Bush TL. Plasma lipoprotein levels as predictors of cardiovascular death in women. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:2209–2216. doi: 10.1001/archinte.153.19.2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crook D, Seed M. Endocrine control of plasma lipoprotein metabolism: effects of gonadal steroids. Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. Edited by Betteridge DJ. USA: Bailliere's. 1996. pp. 851–875. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kannel WB. Metabolic risk factors for coronary heart disease in women: perspective from the Framinghan study. Am Heart J. 1987;114(2):413–419. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(87)90511-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crook D, Stevenson JC. CHD in women - are serum lipids and lipoproteins important? Lipids: Current Perspectives . Edited by Betteridge & Mosby . London: Mosby, 1996. pp. 171–186.

- Wingard DL. Sex differences and coronary heart disease. Circulation. 1990;81:1710–1712. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.5.1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortalidade em Campinas - Informe trimestral do projeto de monitorização dos óbitos no município de Campinas, Secretaria Municipal de Saúde/ Prefeitura do Município de Campinas e Laboratório de Aplicação em Epidemiologia/DMPS/FCM/UNICAMP, São Paulo, Brasil Boletim. 1994;15 [Google Scholar]

- Mortalidade geral pelos cinco principais grupos de causas (CID 10) segundo região de saúde (DIR) - Secretaria de Estado da Saúde São Paulo Boletim. 1997.

- Lotufo PA, Lolio CA. Tendência da mortalidade por doença isquêmica do coração no Estado de São Paulo:1970 a 1989. Arq Bras Cardiol. 1993;61:149–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotufo PA. Epidemiologia das doenças isquêmicas do coração no Brasil. O Adulto Brasileiro e as Doenças da Modernidade Edited by Lessa I. São Paulo: Hucitec/Abrasco, 1998. pp. 115–122.

- Fleiss JL. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc, 1981.

- Expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults: summary of the second report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adults Treatment Panel II). JAMA. 1993;269:3015–3023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2° Consenso Brasileiro sobre Dislipidemias: avaliação, detecção, tratamento. Arq Bras Cardiol. 1996;67:109–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colditz GA, Willett WC, Stampfer MH, Rosner B, Speizer FE, Hennekens CH. Menopause and the risk of coronary heart disease in women. N Engl J Med. 1987;316(18):1105–1110. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198704303161801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brochier ML, Arwidson P. Coronary heart disease risk factors in women. Eur Heart J. 1998;Suppl A:A45–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco LJ. Epidemiologia do Diabetes Mellitus. In 0 Adulto brasileiro e as doenças da modernidade Epidemiologia das doenças crônicas não-transmissíveis Edited by Lessa l São Paulo: Hucitec/Abrasco. 1998. pp. 123–137.

- Hsia AJ. Cardiovascular disease in women. Med Clin North Am. 1998;82(1):1–19. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70592-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch KV. Fatores de Risco Cardiovasculares e para o Diabetes Mellitus. In O Adulto brasileiro e as doenças da modernidade Epidemiologia das doenças crônicas não-transmissíveis Edited by Lessa I São Paulo: Hucitec/Abrasco. 1998. pp. 43–72.

- Guimarães AC, Lima A, Mota E, Lima JC, Martinez T, Conti AF, et al. The cholesterol level of a selected Brazilian salaried population: biological and socioeconomic influences. CVD Prevention. 1998;1:306–317. [Google Scholar]

- Lessa I. Epidemiologia da Hipertensão Arterial. In O Adulto brasileiro e as doenças da modernidade Epidemiologia das doenças crônicas não-transmissíveis Edited by Lessa I São Paulo: Hucitec/Abrasco; 1998. pp. 77–96.

- Fetters JK, Peterson ED, Shaw JL, Newby LJ, Durham NC. Sex-specific differences in coronary arthery disease risk factors, evaluation, and treatment: have they been adequately evaluated? Am Heart J. 1996;131:796–813. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(96)90289-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair SN, Kohl HW, III, Paffenbarger RS, Jr, dark DG, Cooper KH, Gibbons LW. Physical fitness and all-cause mortality, a prospective study of healthy men and women. JAMA. 1989;262:2395–2401. doi: 10.1001/jama.262.17.2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris BT, Ballard-Barbach R, Makuc DM, Feldman JJ, Madans J. Overweight, weight loss, and risk of coronary heart disease in older women. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137:1319–1327. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenck-Gustafsson K. Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in women: assessment and management. Eur Heart J. 1996;17:1–8. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/17.suppl_d.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman DS, Jacobsen SJ, Barboriak JJ, Sobocinski KA, Anderson AJ, Kissebah AH, et al. Body fat distribution and male/female differences in lipids and lipoproteins. Circulation. 1990;81(5):1498–1506. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.5.1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willett WC, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Rosner B, Speizer FE, et al. Weight, weight change, and coronary heart disease in women, risk within the 'normal' weight range. JAMA. 1995;273(6):461–465. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03520300035033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipid Research Clinics Program Prevalence Study and Lipid Metabolism Branch, Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institute of Health, publication No80-1527, In Tietz Textbook of Clinical Chemistry Edited by Burtis C and Ashwood E: Phyladelphia: Saunders; 1999. p. 826.

- Lima J, Jr, Costa-Paiva L, Pedro AO, Pinto Neto AM. Effects of hormonal replacement therapy on blood pressure, body weight, and lipidic profile of post-menopause women. Schiff I, Utian WH, Graham DK, eds. Proceedings of the Ninth Annual Meeting of the North American Menopause Society. Baltimore: J North Am Menopause Soc. 1998. pp. 268–269.