Abstract

Background:

Various adverse health effects associated with shift work have been documented in the medical literature. These include increased risk of cardiovascular disorders, cerebrovascular disorders, and mortality. Sleep deprivation has been shown to be associated with an elevation in inflammatory makers such as interleukin 6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and C-reactive protein (CRP). It is hypothesized that the increased risk of many disorders associated with shift work may be due to inflammatory processes resulting from sleep deprivation. The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between night work and inflammatory markers.

Materials and Methods:

Fifty workers were selected according to the specified inclusion and exclusion criteria and randomly assigned to one of two groups in a cross over study. The 25 workers in group 1 were scheduled to work the following consecutive shifts: three day shifts, one day off, and three night shifts. Group 2 were scheduled to work the following consecutive shifts: three night shifts, one day off, and three day shifts. Blood samples were obtained between 7:A.M. and 8:A.M. after the periods of day work and night work and tested for inflammatory markers.

Statistical Analyses:

SPSS 11.5 and S-data were used to analyze data using the Student's t-test and paired t-test.

Results:

There was a statistically significant increase in IL-6, CRP, white blood cells, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and platelets following night work compared with day work. TNF-α was increased but it was not statistically significant, and also the change in monocyte counts was not significant.

Conclusion:

This study demonstrated an increase in inflammatory markers following night work, as reported in several pervious studies on sleep deprivation. No significant changes in monocyte count can be justified by the results of a study which showed that the elevation in blood levels of inflammatory markers is due to increase in gene expression, not in monocyte counts.

Keywords: C-reactive protein, IL-6, inflammatory markers, platelet, shift work, tumor necrosis factor-α, white blood cells

INTRODUCTION

Shift work is defined as work at times other than the daytime hours of 7:00 A.M. to 6:00 P.M. It is estimated that almost 15% of full-time workers in the United States (i.e., 15 million Americans) are shift workers who work evening, night, or rotating shifts. Social needs and economic factors promote the use of shift work. Shift workers provide critical services, including police and fire protection, health care, transportation, communications, public utilities, military service, and services in industries that require continuous processing.[1,2]

Shift work has been documented to cause adverse health effects, by disturbing three factors: circadian rhythms, sleep, and personal (i.e., family and social) life.[1]

In the long term, because of disturbance of circadian rhythms such as the sleep-wake cycle, morbidity and mortality rates in shift workers will be increased.[3–6]

Some previous studies have demonstrated an increased risk of medical conditions, including cardiovascular disease, arthritis, diabetes mellitus, and certain cancers in association with sleep deprivation.[6–12]

A number of studies have suggested that sleep disorders such as sleep loss, narcolepsy, and sleep apnea are associated with elevated inflammatory markers such as interleukin 6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), C-reactive protein (CRP), and white blood cells (WBC).[12–19]

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the relationship between night work and elevation of inflammatory markers.

Regards to the side effects of shift work and circadian rhythms and sleep disturbance as one of the important cause of these side effects and on the other hand the elevation of inflammatory markers after sleep deprivation, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the relationship between night work shifts and elevation of inflammatory markers.

The relationship between increased inflammatory markers and medical conditions, which is the same as side effects of shift work, has been observed in some studies. If further studies support the results of this study, we can use inflammatory markers for early detection of long-term health side effects of shift work in future for prevention of them.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

The subjects included 50 healthy workers who gave consent and were paid for participation in this study. Inclusion criteria required the healthy workers. Workers were excluded from the study if they had any history of inflammatory disease, cancer, chronic disease, psychotic disorder, drug or alcohol abuse, body mass index (BMI) >30, or smoking history (as determined by review of pre-employment and annual employment medical records). Workers who were determined to have sleep disorders according to their score on the Epworth sleepiness scale (ESS) and insomnia questionnaires were also excluded. Cutoff point for ESS questionnaire was 13 and for insomnia questionnaire was 8. They were also excluded if they developed any acute disease or reported poor sleep during the study period.

Protocol

We designed a randomized clinical cross over trial study with a specific shift work schedule.

Group 1 (25 workers): they were scheduled on three days of day shift work, followed by one day off (wash out period), and then three nights of night shift work.

Group 2 (25 workers): they were scheduled on three days of night shift work, followed by one day off (wash out period), and then three days of day shift work.

Blood samples were obtained via indwelling catheter between 7:A.M. and 8:A.M. after the periods of day work and night work in both groups.

Assay

Blood samples were divided into two parts; one part was transferred to a clot tube and centrifuged as soon as possible. The serum was frozen at –25°C until the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was performed. IL-6 and TNF-α were measured by ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The lower detection limit was 0.09 pg/mL. High-sensitive CRP was also measured by ELISA (IBL-International, Hamburg, Germany). The lower detection limit was 0.01 mg/mL.

The second part of the sample was mixed with EDTA (anti-coagulant) for complete blood count and differential and analysis by a cell counter H1 device.

Statistical analyses

SPSS 11.5 and S-data were used to analyze data using the Student's t-test and paired t-test.

RESULTS

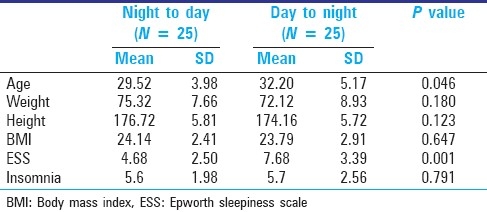

Descriptions of age, weight, height, BMI, ESS, and Insomnia questionnaires scores of workers are shown in Table 1. Despite random allocation of workers between the two groups, there were significant differences in age and ESS between the two groups. For omission of confounder effects of these variables, we used multivariant regression.

Table 1.

Description of age, weight, height, body mass index, Epworth sleepiness scale, and insomnia questionnaire scores of workers

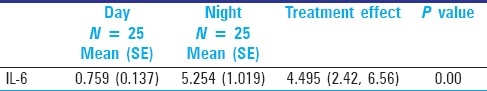

There were no carry over effects in the two periods of study on outcomes except IL-6. So we just used data of period 1 for IL-6.

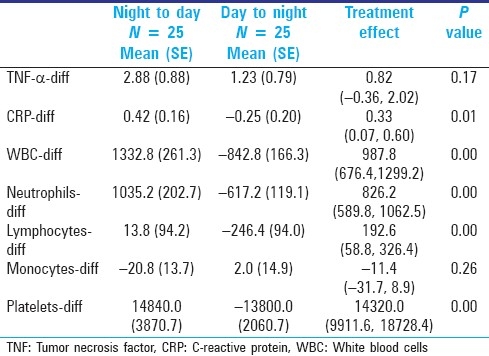

Compared with day work shifts, night work shifts were associated with increased levels of IL-6, TNF-α, CRP, WBC, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and platelets, but for TNF-α was not statistically significant. There was no significant change in monocytes [Tables 2 and 3].

Table 2.

IL6 after day work and night work shifts

Table 3.

Difference between night to day and day to night groups for out comes

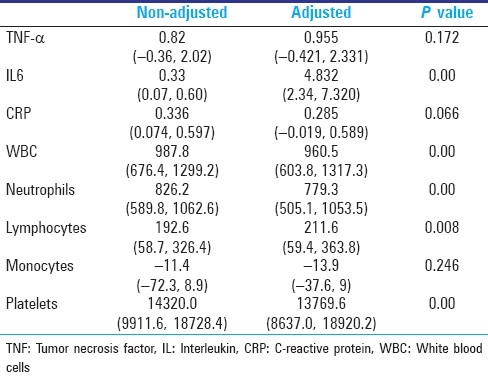

Multivariant regression analysis was done for omitting the confounder effects of age and ESS between two groups [Table 4].

Table 4.

Adjusted data after multivariant regression analysis

To determine the best model for eliminating the confounder effects of age BMI, ESS, and insomnia questionnaire score, Lr-test was done and none of these variables had significant effect.

DISCUSSION

Association of elevation of inflammatory factors and sleep deprivation has been demonstrated in some studies, and we have demonstrated this association with night work shifts. In this study, statistically significant increased levels of IL-6, CRP, WBC, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and platelets were shown. The change in TNF-α was not statistically significant. There was no significant change in monocytes.

Cytokines are secreted in a biphasic circadian pattern.[20,21] Hence, to limit the diurnal variation of secretion of cytokines, we measured the outcomes between 7:A.M. and 8:A.M.

The half-life of cytokines has been suggested to be about 60 min.[22] So a one day wash out period was considered to be sufficient. However, in our study a carry over effect for IL-6 was observed with no precise description, so it may be prudent to further investigate the relationship between night shift work and IL-6.

The study by Irwin et al. suggested that elevation of IL-6 and TNF-α is due to gene expression of inflammatory markers in each monocyte rather than overall increase in monocyte counts.[12] There were no significant changes in monocyte levels in this study.

CONCLUSION

This study showed an increase in inflammatory markers after night shift work. Mounting evidence has demonstrated an association between elevation of inflammatory markers and the risk of medical conditions, including cardiovascular disease, arthritis, diabetes mellitus, and certain cancers, which are reported in shift workers too. Thereby these results favor the hypothesis that the side effects of shift work may be related to elevation of inflammatory markers.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Further studies are necessary to support our findings and if so, inflammatory markers can be used for early detection of health effects of shift work.

If this hypothesis is proven, new studies need to be done to evaluate the effects of work place interventions such as bright light or rest breaks on inflammatory markers. If these markers decrease after these interventions, side effects of shift work may be preventable.

If further studies support the results of this study, we can use inflammatory markers for early detection of long-term health side effects of shift work in future for prevention of them.

At present, it is premature to extend this speculation into clinical decision making other than to consider a modification of work place.

LIMITATIONS

Because of limitations in financial sources and workers cooperation, it was not possible to measure the inflammatory markers in every night and day work, and so the trend of changes could not be detected.

This trial is registered with Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials. (registration ID: IRCT138811133265n1).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Roohi Qureshi, MD, MEng, FRCPC, for correction in English and edition, and Chodan sazan factory (Isfahan, Iran); Hoseyn Ansari (manager of the factory), Maryam Farhang (health, safety and environment unit) for cooperation.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Tehran University of Medical Sciences,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Caruso C, Rosa RR. Shift work and long work hours. In: Rom WN, editor. Environmental and Occupational Medicine. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Willams and Wilkins; 2007. pp. 1359–64. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seward JP, Larsen RC. Occupational stress. In: Ladou J, editor. Current Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 4th ed. New York: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2007. pp. 608–11. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barton J, Spelten E, Totterdell P. The standard shift work index-a battery of questionnaires for assessing shift work-related problems. Work Stress. 1995;9:4–30. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monk TH. Shift work. In: Kupfer DJ, Roth T, Dent WC, editors. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000. pp. 600–5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akerstedt T. Adjustment of physiological and circadian rhythms and the sleep-wake cycle to shift work. In: Folkard S, Monk TH, editors. Hours of Work: Temporal Factors in Work Scheduling. Chichester United Kingdom: John Wiley; 1985. pp. 185–98. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sparks K, Cooper CL, Fried Y. The effects of hours of work on health: A meta-analytic review. J Occup Organ Psychol. 1997;70:391–408. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spurgeon A, Harrington JM, Cooper CL. Health and safety problems associated with long working hours: A review of the current position. Occup Environ Med. 1997;54:367–75. doi: 10.1136/oem.54.6.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van der Hulst M. Long workhours and health. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2003;29:171–88. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Volpato S, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Balfour J, Chaves P, Fried LP, et al. Cardiovascular disease, interleukin-6, and risk of mortality in older women, the Women's Health and Aging Study. Circulation. 2001;103:947–53. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.7.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrucci L, Harris TB, Guralnik JM. Serum IL-6 level and the development of disability in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:639–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lange T, Dimitrov S, Born J. Effects of sleep and circadian rhythm on human circulating immune cells. J Immunol. 1997;158:4454–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Irwin MR, Wang M, Campomayor CO, Collado-Hidalgo A, Cole S. Sleep deprivation and activation of morning levels of cellular and genomic markers of inflammation. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1756–62. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.16.1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hohjoh H, Nakayama T, Ohashi J, Miyagawa T, Tanaka H, Akaza T, et al. Significant association of a single nucleotide polymorphism in the tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF - α) gene promoter with human narcolepsy. Tissue Antigens. 1999;54:138–45. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.1999.540204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alberti A, Sarchielli P, Gallinella E, Floridi A, Floridi A, Mazzotta G, et al. Plasma cytokine levels in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: A preliminary study. J Sleep Res. 2003;12:305–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2003.00361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Irwin M, McClintick J, Costlow C, Fortner M, White J, Gillin JC. Partial night sleep deprivation reduces natural killer and cellular immune responses in humans. FASEB J. 1996;10:643–53. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.5.8621064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishitani N, Sakakibara H. Subjective poor sleep and WBC in male Japanese workers. Ind Health. 2007;45:296–300. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.45.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hohjoh H, Terada N, Kawashima M, Honda Y, Tokunaga K. Significant association of the tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 (TNFR2) gene with human narcolepsy. Tissue Antigens. 2000;56:446–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2000.560508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wieczorek S, Dahmen N, Jagiello P, Epplen JT, Gencik M. Polymorphisms of the tumor necrosis factor receptors: No association with narcolepsy in German patients. J Mol Med. 2003;81:87–90. doi: 10.1007/s00109-002-0405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vgontzas AN, Zoumakis M, Bixler EO, Lin HM, Prolo P, Vela-Bueno A, et al. Impaired nighttime sleep in healthy old versus young adults is associated with elevated plasma interleukin-6 and cortisol levels: Physiologic and therapeutic implications. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:2087–95. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bredow S, Guha-Thakurta N, Taishi P, Obál F, Jr, Krueger JM. Diurnal variations of tumor necrosis factor alpha mRNA and alpha-tubulin mRNA in rat brain. Neuroimmunomodulation. 1997;4:84–90. doi: 10.1159/000097325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haack M, Pollmächer T, Mullington JM. Diurnal and sleep-wake dependent variations of soluble TNF- and IL-2 receptors in healthy volunteers. Brain Behav Immun. 2004;18:361–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nathan Wei. Plasma cytokines half-life. [last cited on 2010 Nov 25]. Available from: http://www.atthritis-treatmrnt-and-relief.com/