Abstract

The Akt substrate AS160 (TCB1D4) regulates Glut4 exocytosis; shRNA knockdown of AS160 increases surface Glut4 in basal adipocytes. AS160 knockdown is only partially insulin-mimetic; insulin further stimulates Glut4 translocation in these cells. Insulin regulates translocation as follows: 1) by releasing Glut4 from retention in a slowly cycling/noncycling storage pool, increasing the actively cycling Glut4 pool, and 2) by increasing the intrinsic rate constant for exocytosis of the actively cycling pool (kex). Kinetic studies were performed in 3T3-L1 adipocytes to measure the effects of AS160 knockdown on the rate constants of exocytosis (kex), endocytosis (ken), and release from retention into the cycling pool. AS160 knockdown released Glut4 into the actively cycling pool without affecting kex or ken. Insulin increased kex in the knockdown cells, further increasing cell surface Glut4. Inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase or Akt affected both kex and release from retention in control cells but only kex in AS160 knockdown cells. Glut4 vesicles accumulate in a primed pre-fusion pool in basal AS160 knockdown cells. Akt regulates the rate of exocytosis of the primed vesicles through an AS160-independent mechanism. Therefore, there is an additional Akt substrate that regulates the fusion of Glut4 vesicles that remain to be identified. Mathematical modeling was used to test the hypothesis that this substrate regulates vesicle priming (release from retention), whereas AS160 regulates the reverse step by stimulating GTP turnover of a Rab protein required for vesicle tethering/docking/fusion. Our analysis indicates that fusion of the primed vesicles with the plasma membrane is an additional non-Akt-dependent insulin-regulated step.

Keywords: Adipocyte, Exocytosis, Glucose Transport, Insulin, Kinetics, Trafficking

Introduction

Glucose uptake in muscle and adipose tissue is rate-limited by the number of facilitative glucose transport proteins present in the plasma membrane (1). In adipocytes, the majority of glucose uptake occurs via the insulin-responsive glucose transporter 4 (Glut4). Insulin regulates glucose uptake by changing the steady state distribution of Glut4 from predominantly an intracellular, perinuclear localization to the plasma membrane, a process known as Glut4 translocation. Under basal conditions, less than 5% of the total Glut4 is found at the PM,2 whereas after insulin stimulation 30–50% is localized to the PM. In basal cells, most of the Glut4 is sequestered into a noncycling/slowly cycling pool in specialized Glut4 storage vesicles (GSVs). A small fraction of the Glut4 is found in a more rapidly cycling pool that is distributed between the PM and endosomal compartments. Insulin increases cell surface Glut4 by two main mechanisms as follows: insulin releases Glut4 from retention in the sequestered GSVs into the actively cycling pool (2–5), and insulin also increases the rate constant of exocytosis, resulting in a further increase in surface Glut4 (2–6).

Although the trafficking pathways followed by Glut4 are well characterized, the mechanism of regulation of Glut4 trafficking by insulin remains incompletely understood. In the canonical insulin signaling pathway, activation of the insulin receptor leads to phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrates 1–4 and activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI 3-kinase) (7, 8). PI 3-kinase activation leads to activation of Akt (protein kinase B), which then phosphorylates many substrates. Activation of both PI 3-kinase and Akt is necessary for stimulation of Glut4 translocation by insulin, and activation of either PI 3-kinase or Akt is sufficient to trigger the redistribution of Glut4 (9, 10). The precise downstream targets of these kinases linking activation of the insulin receptor to translocation of Glut4 have remained elusive.

Identification of the Akt substrate of 160 kDa (AS160, TCB1D4) was an important breakthrough, linking insulin signal transduction directly to Glut4-containing intracellular vesicles (11, 12). To date, AS160 (and its paralog TBC1D1) is the only Akt substrate identified that shows a phosphorylation-dependent effect on Glut4 trafficking. It is also the only substrate of Akt identified that is found on Glut4 vesicles. AS160 is phosphorylated by Akt on at least six sites after insulin stimulation (12). Mutation of four of these sites to alanine results in a mutant form of the protein termed “AS160–4P” (12). Expression of AS160–4P in 3T3-L1 adipocytes inhibits insulin-stimulated translocation of Glut4 (12, 13). Underscoring the importance of AS160 in metabolic regulation, a truncation mutant of AS160 was identified in humans with dominant inherited insulin resistance (14).

Consistent with a role for AS160 in basal retention of Glut4, knockdown of AS160 expression using shRNA increases Glut4 at the plasma membrane 3–6-fold under basal conditions (15, 16). Although many treatments and protein constructs have been identified that inhibit Glut4 translocation, AS160 knockdown is one of a limited number of treatments that increases cell surface Glut4 in basal cells. Others include expression of an activated form of Rab10 (17) and knockdown/expression of dominant negative forms of IRAP (18), TUG (19, 20), synapsin (21), and syntaxins 6 and 16 (22, 23). However, all of these treatments are only partially insulin-mimetic. For example, stimulation of AS160 knockdown (AS160 KD) cells with insulin leads to a 3–5-fold further increase in cell surface Glut4 (15, 16).

It had been suggested that the partial translocation of Glut4 is due to the fact that AS160 knockdown is incomplete or that it is not uniform in all cells in the population. We hypothesized that the explanation for this partial effect on Glut4 exocytosis is that AS160 is involved in only one of the insulin-regulated steps that affect Glut4 exocytic trafficking kinetics. To test this hypothesis, the effects of AS160 knockdown on Glut4 exocytosis were determined under experimental conditions where the effects on the release of Glut4 from the storage compartments could be distinguished kinetically from the effects on the intrinsic rate of cycling, kex (2–5), where kex indicates the rate constant for exocytosis. Differential effects of AS160 knockdown on these processes would not have been resolved in the previous experiments. In addition, Glut4 traffics through multiple compartments in its cycling itinerary, and thus the observed kex is actually a function of the rate constants for the transfer of Glut4 between various compartments and not simply a measure of the rate of fusion of Glut4 vesicles to the plasma membrane. Therefore, the effects of AS160 knockdown on transition kinetics were also measured to more accurately assess which steps in Glut4 trafficking are regulated through AS160.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Tissue Culture

3T3-L1 cells were obtained from ATCC. Cells were maintained as fibroblasts and differentiated into adipocytes as described previously (4, 5).

Viral Infections

The HA-Glut4/GFP reporter protein was prepared and transduced into 3T3-L1 pre-adipocytes using lentivirus as described previously (4). Approximately 80% of the cells expressed the HA-Glut4/GFP reporter construct. Therefore, very few cells were infected with more than one virion. Under these culture conditions, there was no detectable cytopathic effect of the viral infection. The doubling time of the infected fibroblasts was not different from the uninfected cells; there were no morphological changes in the fibroblasts; the cells differentiated as well as the uninfected cells (as detected by visual inspection), and the cells were both highly insulin-sensitive and -responsive (4, 5). The uninfected cells serve as internal controls for nonspecific binding and autofluorescence in each sample. Adipocytes expressing HA-Glut4/GFP have the same total level of Glut4 labeling as the uninfected adipocytes, indicating that the reporter is expressed at low levels relative to endogenous Glut4 (less than 10% of the endogenous levels). This was confirmed by Western blotting. The trafficking of this reporter has been very carefully characterized; when expressed at low levels, the HA-Glut4/GFP reporter traffics with the endogenous Glut4 (2, 3, 6, 21, 24).

After recovery from lentiviral infection, cells were further infected with retroviruses encoding either an shRNA sequence targeting AS160 or a control nontargeting sequence (15). These shRNA sequences were in the pSiren RetroQ backbone and were a gift from Dr. Gustav Lienhard. Briefly, Phoenix-Ampho packaging cells (Orbigen) were transfected with the retroviral shRNA constructs using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Media containing retrovirus were harvested three times between 24 and 48 h post-transfection, mixed with an equal volume of 10% calf serum in DMEM complete media (high glucose DMEM supplemented with 2 mm l-glutamine, 50 units/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin), supplemented with 4 μg/ml Polybrene, filtered through a 0.45-micron filter, and applied to subconfluent pre-adipocytes. Cells were allowed to recover in DMEM complete media, 10% calf serum for 12 h after the third infection with virus before selection in 2.5 μg/ml puromycin (Sigma). Cells were carried in the selection media until the start of differentiation. Retroviral infections were repeated multiple times and were monitored carefully for cytopathic effects as described above. To assess whether the observed phenotypes of AS160 knockdown were due to off-target effects, cells were infected with commercially prepared lentivirus expressing unrelated shRNA sequences that target AS160 (Sigma). All of the phenotypes observed with the retrovirus-induced knockdown of AS160 were reproduced with the lentivirus.

Antibodies

HA.11 anti-HA monoclonal antibody was purchased from Covance as ascites and purified using protein A-Sepharose as described previously (4). The purified antibody was then labeled with AlexaFluor647 monoclonal antibody labeling kit (Invitrogen) for 2 h at room temperature and then overnight at 4 °C, according to the manufacturer's recommended protocol. Free dye was removed by desalting twice into PBS using 2 ml of Zeba desalting spin columns (7000 molecular weight cutoff, Pierce) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Antibody concentration and labeling efficiency were determined by absorbance spectroscopy as described previously (4).

Glut4 Translocation Assay/Surface Labeling

Adipocytes expressing HA-Glut4/GFP were serum-starved for 2 h in 50 μl of low serum media (LSM), consisting of DMEM complete media and 0.5% FBS. In some experiments, cells were pretreated with LY294002 (LYi, EMD Chemicals) or Akt inhibitor VIII/Akti-1/2 (Akti, EMD Chemicals) at the indicated concentrations for the 2nd h of serum starvation. After starvation, media was removed and replaced with LSM containing the indicated concentrations of insulin and inhibitors for 45 min. To label surface Glut4, cells were placed on ice, and media was replaced with LSM containing 50 μg/ml AlexaFluor647-anti-HA. After surface labeling for 1 h, antibody was removed, and cells were washed three times with 200 μl of ice-cold PBS, collagenase-digested, and analyzed by flow cytometry as described previously (4, 5).

Steady State Anti-HA-uptake Experiments

Adipocytes were serum-starved as described above. For insulin-stimulated uptake, LSM was replaced after 1 h with LSM containing 100 nm insulin. In some experiments, cells were treated with LYi or Akti for 1 h before insulin was added. At various times, the stimulation media were removed and replaced with LSM containing insulin and inhibitors and 50 μg/ml AlexaFluor647-anti-HA. After uptake was completed, cells were placed on ice and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Transition Experiments

Adipocytes were serum-starved in LSM. In the basal to insulin-stimulated transition, insulin was added, and cells were incubated for increasing times. In some experiments, 20 μm Akti was added for 1 h before insulin addition. For the transition from the insulin-stimulated to PI3K-inhibited state, LSM was replaced with LSM containing 100 nm insulin for the last 45 min of starvation, and 50 μm LYi was added to the insulin-stimulated cells, and the cells were incubated for increasing times. After the time course was completed, cells were placed on ice; surface Glut4 was labeled, and cells were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometry and gating were performed essentially as described previously (4, 5). Briefly, cells in 96-well plates were chilled on ice and washed three times with 200 μl of PBS. Cells were collagenase-digested and gently resuspended in a final volume of 200 μl in PBS. Cell suspensions were filtered through a 100-μm cell strainer and analyzed by flow cytometry on a FACScan cytometer (BD Biosciences). Log intensities of scattered light (forward scatter and side scatter; 488 nm excitation) and fluorescence (FL1, 488 nm excitation/525 nm emission; FL2, 488 nm excitation/595 nm emission; FL3, 488 nm excitation/>640 nm emission; FL4, 633 nm excitation/>670 nm emission) were collected. Adipocytes were gated from cellular debris and residual fibroblasts in the sample cell population using FlowJo software (Tree Star) as described previously (4). Briefly, high scatter cells (adipocytes and debris) were selected by gating on two-dimensional histograms of side scatter versus forward scatter to eliminate the low scatter fibroblasts, and then adipocytes were selected by gating on side scatter versus FL3 (autofluorescence) to eliminate dead cells/debris, which is highly autofluorescent. Elliptical gates on two-dimensional histograms of side scatter versus FL1 (GFP) were used to distinguish lentivirus-infected cells expressing the HA-Glut4/GFP reporter from uninfected cells. AS160 knockdown caused a significant decrease in the expression of the HA-Glut4/GFP reporter compared with control cells (supplemental Fig. 1). Expression of Glut4-GFP was uniform in the AS160 KD cells, as was anti-HA labeling both at the cell surface and in uptake experiments. Multiple populations of cells were not observed. Thus, the effect of shRNA expression was uniform in the population of cells stably transfected by retroviral infection. Nonspecific binding and background autofluorescence were corrected for by subtracting the geometric mean FL4 and FL1 fluorescence values of uninfected cells from those of infected cells. Mean fluorescence ratios (MFRs) were calculated as the ratio of the background-corrected geometric mean of FL4 (AlexaFluor647-anti-HA labeling) to the background-corrected geometric mean of FL1 (total HA-Glut4/GFP expression).

Modeling and Simulations

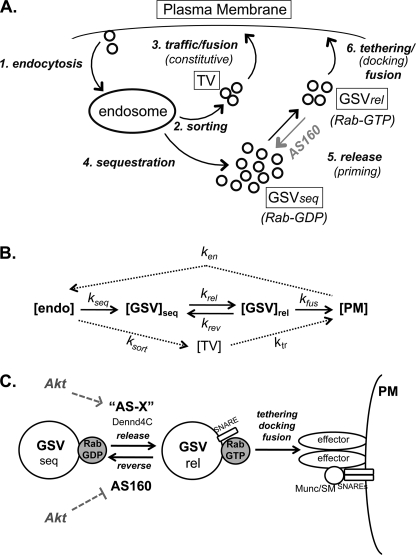

The Glut4 trafficking itinerary depicted in Fig. 6 was modeled mathematically as a series of simple differential equations that describe the transfer of Glut4 between five compartments as follows: PM, endosomes (endo), transport vesicles (TV), sequestered Glut4 storage vesicles (GSVseq), and primed (pre-fusion) GSVs (GSVrel) with a single rate constant for each of seven steps. These seven steps include endocytosis from PM to endosomes (ken), sorting from endosomes to the transport vesicles in the constitutive exocytic pathway (ksort), traffic/priming/fusion of the TVs (ktr), sorting from endosomes into the sequestered GSVs (kseq), release/priming of sequestered GSVs into the active pre-fusion pool (krel, this step includes activation of a Rab protein bound to the GSVs), reversal of priming by AS160-Ras GTPase-activating protein (krev), and the tethering/docking/fusion of the primed GSVs (kfus). The rate of change of Glut4 in any given compartment (A) at time t equals the rate of entry of Glut4 into A minus the rate of exit out of A. The rate of entry into A equals the concentration of Glut4 in any prior compartment (C) at time t that feeds directly into A times the rate constant for delivery from C to A (kC→A [C]t). The rate of exit out of A equals the concentration of Glut4 in A times the rate constants for the movement of Glut4 from A into a subsequent compartment(s) (B; kA→B [A]t). Thus, the model is described by Equations 1–5.

Equations 1–5 were used to simulate the movement of Glut4 by solving them numerically using computing software (Mathematica 7) as described previously (4). The rate constants used in the simulations (Table 1) were selected based on the following criteria.

FIGURE 6.

Models. A and B, Glut4 trafficking can be modeled as six kinetically distinct steps with seven rate constants. Step 1, endocytosis, removal of Glut4 from the PM and delivery to endosomes, ken. Step 2, sorting, packaging into constitutive TV, ksort. Step 3, trafficking/fusion of the constitutive vesicles, ktr. Step 4, sequestration, the Glut4 in endosomes (endo) is also packaged into specialized Glut4 storage vesicles (GSVseq), kseq. Step 5, release, in response to insulin, GSVs are released from the retention mechanism, and the vesicles become competent to fuse (in part through GTP loading of a bound Rab, krel); AS160 regulates this step by reversing the activation of the Rab (by activating the Rab-GTPase; krev). Step 6, tethering/docking/fusion, primed GSVs bind to the plasma membrane via specific tethering and docking proteins (including Munc/SMs and SNAREs) and the vesicles fuse, kfus. Effects on any of these steps will affect the levels of Glut4 at the cell surface. C, Akt regulates the release of GSVs from retention by both increasing the rate of priming (through an unknown substrate, AS-X) and through the inhibition of AS160, which reverses the priming. Insulin also regulates vesicle tethering/docking/fusion through an additional mechanism that is Akt-independent.

TABLE 1.

Summary of rate constants and steady state distributions of Glut4 used in the simulations (Fig. 7)

| Rate constants |

Steady state distribution |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ken | ksort | ktr | kseq | krel | krev | kfus | [PM] | [Endosome] | [TV] | [GSVseq] | [GSVrel] | |

| min−1 | % | |||||||||||

| Control | ||||||||||||

| Basal | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 1.1 | 6.7 | 0.5 | 85.0 | 6.7 |

| Insulin | 0.12 | 0.026 | 0.20 | 0.026 | 0.04 | 0.007 | 0.12 | 18.0 | 40.0 | 5.0 | 28.0 | 9.0 |

| AS160 KD | ||||||||||||

| Basal | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.007 | 0.01 | 4.2 | 25.3 | 2.0 | 43.0 | 25.5 |

| Insulin | 0.12 | 0.022 | 0.20 | 0.022 | 0.04 | 0.007 | 0.12 | 16.0 | 45.0 | 5.0 | 26.0 | 8.0 |

ken was measured in the insulin + LYi transitions for control and AS160 KD cells (0.12 min−1; Fig. 5B). Insulin does not affect ken in 3T3-L1 adipocytes (5).

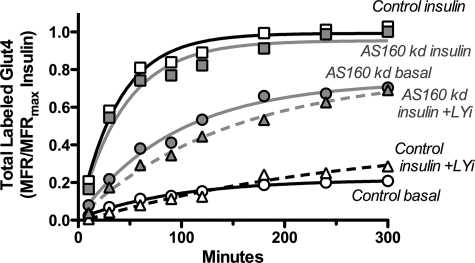

FIGURE 5.

Glut4 vesicles accumulate in a primed, pre-fusion pool in basal AS160 KD cells. Surface Glut4 transition kinetics are shown. A, insulin (100 nm) was added to basal cells, and incubation was continued at 37 °C for increasing times. B, cells were stimulated with insulin for 45 min and then LYi (50 μm) was added, and incubation was continued at 37 °C for increasing times. C, cells were preincubated with 20 μm Akti for 1 h prior to stimulation with insulin for increasing times. After incubation, the cells were placed on ice, and cell surface Glut4 was measured. Data are standardized to control or AS160 KD insulin for each experiment and are the average MFR ± S.D. of n = 5 experiments. Lines are single exponential fits of the average data. Control: +insulin, kobs = 0.13 ± 0.01 min−1 and Ymax = 1; Akti +insulin, kobs = 0.13 ± 0.02 min−1 and Ymax = 0.24; insulin +LYi, kobs = 0.12 ± 0.01 min−1 and Ymin = 0.04. AS160 KD: +insulin, kobs = 0.24 ± 0.03 min−1 and Ymax = 1; Akti +insulin, kobs = 0.13 ± 0.02 min−1, Ymax = 0.54; insulin +LYi kobs = 0.12 ± 0.01 min−1 and Ymin = 0.24.

ksort and kseq were set equal to the kex measured in the uptake experiments determined by single exponential fits of the data (basal, 0.01 min−1; insulin, 0.027 min−1 in control cells and 0.022 min−1 in AS160 KD cells; Figs. 2 and 3). The overall observed kex will be approximately equal to the rate-limiting step(s) in the fastest cycle. In the absence of additional information, this yields a reasonable approximation of the data. The increase in these rates with insulin is consistent with the general increase in cycling through the endocytic pathway that has been observed for many proteins (5, 25–27).

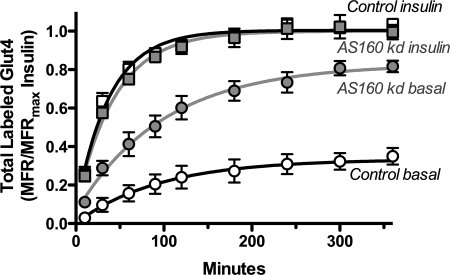

FIGURE 2.

AS160 knockdown increases the actively cycling pool size (Ymax) but not the intrinsic rate constant for trafficking (kex). α-HA uptake kinetics are shown. Cells were pretreated ± insulin for 45 min and then incubated at 37 °C for increasing times with AlexaFluor647-α-HA ± insulin. Data are standardized to Ymax control or AS160 KD insulin for each experiment (Ymax AS160 KD was 0.93× Ymax control) and are the average MFR ± S.D. of n = 5 experiments. Lines are single exponential fits of the average data. Control: basal, Ymax = 0.33 ± 0.05 and kex = 0.01 ± 0.005 min−1; insulin, Ymax = 1.0 ± 0.01 and kex = 0.026 ± 0.003 min−1; AS160 KD: basal, Ymax = 0.83 ± 0.04 and kex = 0.01 ± 0.002 min−1; insulin, Ymax = 1.0 ± 0.02 and kex = 0.022 ± 0.003 min−1.

FIGURE 3.

Glut4 translocation requires Akt and PI 3-kinase activity in AS160 KD cells. Inhibitor dose response and surface Glut4 labeling are shown. Cells were preincubated with the indicated concentrations of PI 3-kinase inhibitor (A and B), LY294002 (LYi) or Akt inhibitor, Akt1/2 (Akti) (C and D) for 1 h. Insulin (0 or 100 nm) was added, and incubation was continued for 45 min and then cell surface Glut4 measured. Data are standardized to control insulin for each experiment and are the average MFR ± S.E. of n = 2 (Akti) or n = 3 (LYi) experiments. Bas, basal; Ins, insulin.

For ktr, the rate of fusion of the Glut4 in the TVs in the constitutive pathway was set equal to the measured rate constant for exocytosis (kex) of the transferrin receptor (0.12 min−1 basal; 0.2 min−1 insulin) (5). Glut4 co-localizes with the transferrin receptor in the recycling endosomes; thus, this seems a reasonable approximation of the rate constants. This rate constant affects the steady state level of Glut4 in the plasma membrane, but it has little effect on the overall trafficking kinetics in our model, and these values give a reasonable approximation of our data.

kfus in basal simulations was set equal to the measured basal kex (0.01 min−1). Our transition data indicate that this is the rate-limiting step in basal cells (Fig. 5). In simulations of insulin stimulation, it was set equal to the initial exocytic rate constant (kout) measured in the basal to insulin transitions in AS160 KD cells (∼0.12 min−1; Fig. 5A). This value is close to the kfusion that can be calculated from total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy-based analysis of docking and fusion in insulin-stimulated cells (kfus = 0.08 min−1) (28, 29). In Scheme 1, kfusion = k1/k−1 × k2.

|

krel in basal simulations was set equal to the measured basal kex (0.01 min−1). In simulations of insulin stimulation, it was determined by fitting the simulated basal to insulin transitions to the transition data measured in control cells (0.04 min−1; Fig. 5A).

krev in basal simulations was determined by fitting the simulated steady state distributions to the distributions indicated by two exponential fits of the uptake data (see under “Discussion”), setting all other rate constants to the indicated basal values (0.12 min−1; Figs. 2 and 3). This results in a steady state distribution of 85% of the Glut4 in the very slowly cycling sequestered GSVs (kex = 0.0007 min−1, t½ >16 h), and the remaining was distributed between the plasma membrane (1.1%) and the more rapidly cycling pool. In simulations of insulin stimulation, it was determined by fitting the simulated basal to insulin transitions to the transition data measured in control cells (0.007 min−1; Fig. 5A). This is the step we hypothesize is regulated by AS160; AS160 knockdown was simulated by setting krev in basal AS160 KD cells to the insulin-stimulated value in control cells, leaving all other rate constants at the basal levels.

The steady state distributions in the simulations (Table 1) were determined by setting the rate constants to the values indicated, setting the concentrations in each compartment to 20%, and letting the simulation run until a new stable distribution was reached. Anti-HA uptake was simulated as described previously (4). Insulin transitions were simulated by setting the initial distributions of Glut4 among the compartments to the basal values and the rate constants to the insulin values and calculating the changes in [PM] with time. Insulin + LYi transitions were modeled by setting the distributions to the insulin values, and the rate constants to the basal values.

RESULTS

AS160 Regulates the Release of Glut4 from Retention in the Noncycling/Slowly Cycling GSV Storage Compartment into the Actively Cycling Pool

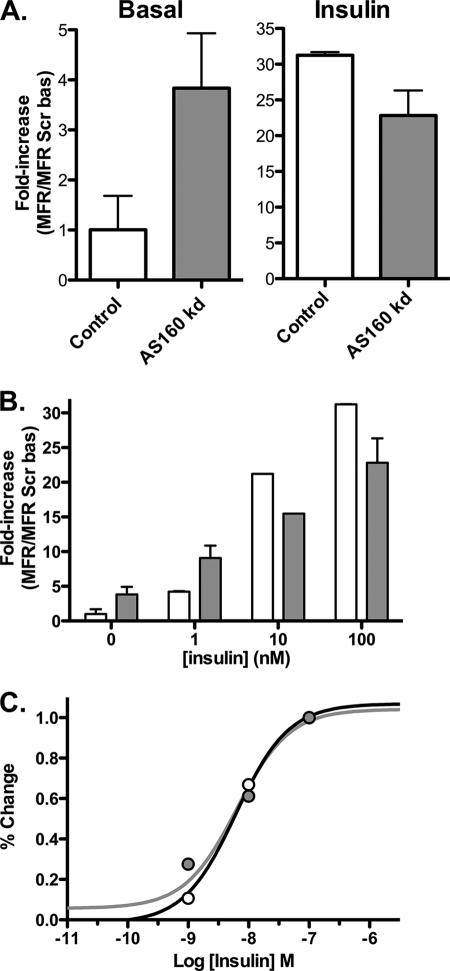

AS160 knockdown caused a 3.8-fold increase in surface Glut4 in basal cells (Fig. 1A) (15, 16). This effect was only partially insulin-mimetic, as insulin promoted a further 6-fold increase in surface Glut4. The anti-HA labeling was uniform in the AS160 KD samples; there was no evidence of multiple populations of cells (supplemental Fig. 1). The levels of labeling in AS160 KD cells looked very similar to control cells that were stimulated with nonsaturating concentrations of insulin (data not shown). Therefore, the effect of expression of the AS160 shRNA was relatively uniform across the population when it was stably expressed using retrovirus; the partial effect of AS160 KD was not due to heterogeneity in the responses of the cells to shRNA expression. Although AS160 knockdown increased basal surface Glut4, it inhibited insulin-stimulated translocation of Glut4 by 27%. This inhibition was due to a decrease in the maximal level of Glut4 observed on the cell surface and not due to a decrease in insulin sensitivity (after correcting for the difference in maximal effect, the insulin dose-response curves for cells expressing a control shRNA or the AS160-specific shRNA were similar; Fig. 1, B and C).

FIGURE 1.

AS160 knockdown is partially insulin-mimetic. Surface Glut4 labeling is shown. 3T3-L1 adipocytes expressing a Glut4 reporter construct (HA-Glut4/GFP) and either a scrambled shRNA (control; white) or an shRNA directed against AS160 (AS160 KD; gray) were incubated ± insulin (100 nm or as indicated) for 45 min and placed on ice, and surface-exposed Glut4 was labeled with AlexaFluor647-conjugated anti-HA antibody (AlexaFluor647-α-HA). Data are standardized to control basal (A and B) or percentage of difference between basal and fully insulin-stimulated cells (C) and are the average mean fluorescence ratio (AlexaFluor647/GFP) ± S.D. (MFR ± S.D.) of n = 9 independent experiments. Control: basal, 1 ± 0.7, and insulin, 31 ± 0.5; AS160 KD: basal, 3.8 ± 1.0, and insulin, 23 ± 0.35.

To determine which steps in Glut4 exocytosis are regulated by AS160, anti-HA uptake experiments were performed (Fig. 2). In our experimental system, two separate effects of insulin on Glut4 exocytosis kinetics can be distinguished (4, 5) as follows: 1) insulin redistributes Glut4 from a very slowly cycling/noncycling pool into the actively cycling pool (increases Ymax); and 2) insulin increases the rate constant for exocytosis (kex) for the cycling pool. Under basal conditions, the measured kex values in the AS160 KD cells and control cells were the same (0.01 ± 0.005 min−1, control versus 0.01 ± 0.002 min−1, AS160 KD). However, the cycling pool size in basal AS160 KD cells was 2.5-fold higher than in control cells and was 85% of the maximal value observed in insulin-stimulated cells. An increase in cycling pool size directly increases the amount of Glut4 on the cell surface. Insulin increased kex in both cell types, further increasing the amount of Glut4 in the plasma membrane in AS160 KD cells. However, both kex and the maximum cycling pool size were slightly lower in the AS160 KD cells than in control cells after insulin stimulation (kex = 0.026 ± 0.003 min−1, Ymax = 1, control versus 0.022 ± 0.003 min−1, Ymax = 0.93 ± 0.07, AS160 KD). It is likely that together these account for the inhibition of maximal Glut4 translocation observed in AS160 KD cells. Therefore, the effect of AS160 knockdown was to release Glut4 from the GSV storage compartment to the cycling pool, with no effect on the intrinsic rate of trafficking in the cycling pool. These data are consistent with previous reports characterizing the effects of AS160 knockdown on Glut4 trafficking kinetics (15, 16). However, the two separate processes we observe would not have been distinguished kinetically in those experiments.

A Second Akt- and PI3 Kinase-dependent/AS160-independent Pathway Regulates the Rate of Glut4 Exocytosis from the Cycling Pool

Previous work had shown that AS160 KD cells are still sensitive to an inhibitor of Akt (27). This suggested that there was a second Akt-dependent substrate required for the regulation of Glut4 translocation by insulin. To characterize this in more detail, AS160 KD and control adipocytes were pretreated with increasing doses of the PI 3-kinase inhibitor LY294002 (LYi) or the Akt inhibitor Akt1/2 (Akti), stimulated with insulin, and the amount of Glut4 present at the cell surface was measured (Fig. 3). As doses of either inhibitor were increased, the levels of surface Glut4 decreased in both cell types. AS160 KD cells were partially resistant to the inhibitors; the dose-response curves for both compounds were shifted to the right. In both cell types, the maximal dose of LYi reduced the level of surface Glut4 in insulin-stimulated cells to its basal level; the surface levels of Glut4 remained elevated in the AS160 KD cells compared with the control cells. Akti also significantly reduced surface Glut4 in both cell types, but the reduction did not reach basal levels for either cell type, despite the fact that saturating concentrations of Akti were used. The inhibitors had little effect on surface levels of Glut4 in basal cells of either cell type.

Inhibition of PI 3-kinase completely blocks Glut4 translocation. AS160, which lies downstream of PI 3-kinase activation of Akt, releases Glut4 from retention in GSVs but does not affect kex. If AS160 inactivation is the only PI 3-kinase-dependent step controlling sequestration in GSVs, then it is expected that inhibition of PI 3-kinase should affect both kex and release from GSVs in control cells. In contrast, it should only affect kex in the AS160 KD cells, and it should not be able to reverse the release of Glut4 from the GSVs. This is what was observed (Fig. 4). In control cells, both cycling pool size and kex values decreased in insulin-stimulated cells with increasing concentrations of LYi, until basal levels were reached for both (supplemental Fig. 2). The inhibitor had little effect in basal cells. Similar results were also observed in adipocytes treated with Akti (supplemental Fig. 3). In contrast, in the AS160 KD cells, treatment with LYi decreased kex to approximately basal levels but had little effect on the amount of Glut4 in the cycling pool. These data strongly support the conclusion that AS160 controls the retention of Glut4 in GSVs and that other unidentified PI 3-kinase/Akt-dependent processes regulate the kinetics of trafficking of the cycling Glut4.

FIGURE 4.

Inhibition of PI 3-kinase affects both kex and Ymax in control cells but only kex in AS160 KD cells. α-HA uptake kinetics are shown. Cells were preincubated ± LYi (50 μm) ± insulin (100 nm) and then α-HA uptake kinetics were measured. Data are standardized to Ymax control or AS160 KD insulin for each experiment (Ymax AS160 KD was 0.95× Ymax control) and are the average MFR ± S.D. of n = 2 experiments. Lines are single exponential fits of the averages. Control: basal, Ymax = 0.21 ± 0.01 and kex = 0.01 ± 0.001 min−1; insulin, Ymax = 1.0 ± 0.03 and kex = 0.026 ± 0.004 min−1; insulin + LYi, Ymax = 0.34 ± 0.13 and kex = 0.004 ± 0.002 min−1. AS160 KD: basal, Ymax = 0.75 ± 0.03 and kex = 0.01 ± 0.001 min−1; insulin, Ymax = 1.0 ± 0.04 and kex = 0.022 ± 0.005 min−1; insulin + LYi, Ymax = 0.78 ± 0.05 and kex = 0.007 ± 0.001 min−1.

AS160 Knockdown Primes Vesicles for Rapid Fusion after Insulin Stimulation

In basal cells, most of the Glut4 resides in noncycling/slowly cycling GSVs. Insulin stimulates the redistribution of Glut4 from the GSVs into an actively cycling endosomal pool. Our data show that AS160 regulates the release of Glut4 into the cycling pool and not the rate of trafficking of the cycling pool itself. At steady state, the kinetics of Glut4 cycling measure the trafficking of the actively cycling pool but not the rate of release from retention because the redistribution has already occurred. Therefore, to measure the effect of AS160 knockdown on trafficking under conditions where AS160 is hypothesized to function, the kinetics of the transition of cells from the basal to the fully insulin-stimulated state were determined (Fig. 5A). The observed relaxation rate constant (kobs) in this transition experiment is a function of the rate constant for initial insertion of Glut4 into the plasma membrane, “kout,” and the rate constant of endocytosis, ken (kobs ≈ kout + ken) (5). Importantly, in this experiment, kout is a function of the rate of release of Glut4 from static GSVs into the cycling pool, as well as the rate of trafficking and fusion to the plasma membrane after release. The rate of recycling of Glut4 through endosomes after internalization affects the steady state levels of Glut4 at the cell surface, and the steady state trafficking kinetics of Glut4 but not the initial rate of insertion into the plasma membrane (30). In parallel samples, the kinetics of loss of Glut4 from the cell surface of insulin-stimulated cells after blocking exocytosis with LYi were also measured (Fig. 5B). This second relaxation rate is approximately equal to ken (5).

In both cell types, ken was the same, 0.12 ± 0.01 min−1. Therefore, AS160 does not affect Glut4 endocytosis. In contrast, the basal to insulin transition was much faster in the AS160 KD cells than in the control cells (kobs = ∼0.24 ± 0.01 min−1, AS160 KD versus 0.13 ± .01 min−1, control). Thus, kout was ∼10 times faster in the AS160 KD cells than in the control cells (kout = ∼0.12 min−1 AS160 KD versus 0.01 min−1 control). These data show that AS160 is regulating a rate-limiting step in the transition from the basal to the insulin-stimulated state in control cells. In addition, kout in the AS160 KD cells was significantly faster than the kex measured in uptake experiments after the steady state had been reached (∼0.12 min−1, transition, versus 0.022 min−1, steady state). Therefore, the initial rate of exocytosis was much faster than the steady state rate after insulin stimulation. Together, these data indicate that the rate-limiting step in the kinetics of Glut4 traffic in the cycling pool lies downstream of AS160 in basal cells (i.e. docking and fusion) but upstream of AS160 after insulin stimulation (i.e. in recycling/trafficking). In the absence of AS160, the Glut4 accumulates in compartments behind the rate-limiting step in the actively cycling pool (prior to docking and fusion), rather than in the noncycling/slowly cycling GSVs. Insulin stimulates the rapid fusion of these primed pre-fusion compartments, causing the initial rapid burst in Glut4 at the plasma membrane in the transition assay. After the initial exocytosis, the recycling of Glut4 back into the pre-fusion compartments after internalization is rate-limiting. Consistent with this, an overshoot was observed in the AS160 KD cells, with higher plasma membrane Glut4 levels seen during the transition from the basal to insulin-stimulated state than after the steady state had been reached (Fig. 7B).

FIGURE 7.

Simulations. A series of differential equations describing the model depicted in Fig. 6 (Equations 1–5) were solved numerically using computing software (Mathematica) to simulate α-HA uptake (A) or transition kinetics (B). Four hypotheses were tested: AS160 regulates krev (solid lines); AS160 regulates kfus (dashed lines); AS160 regulates ksort and ktr (alternating lines); AS160 regulates kseq (dotted lines). Symbols: measured data (white, control; gray, AS160 KD). C, simulating the effect of Akti on transition kinetics. Two hypotheses were tested: Akt regulates krev and krel (solid line); Akt regulates krev and kfus (dotted line). Symbols: measured data, standardized to final steady state levels for each cell type.

The transition data indicate that insulin regulates a rate-limiting step downstream of release of Glut4 from retention in the storage pool. To determine whether this step is regulated by Akt, insulin transition kinetics were done in cells that had been pretreated with Akti (Fig. 5C). Treatment of basal cells had little effect on cell surface Glut4 levels in either control or AS160 KD cells (control, 0.08 versus 0.06; AS160 KD, 0.24 versus 0.2). In contrast, Akti significantly decreased the final steady state cell surface Glut4 levels after insulin stimulation in both cell types (control, 0.21 versus 1.0; AS160 KD, 0.54 versus 1.0). When these two data sets are standardized to the maximal insulin-stimulated levels for each cell type, the data from the two cell types are super-imposable (Fig. 7C). There is no longer a rapid burst of exocytosis of primed vesicles in the AS160 KD cells after insulin stimulation. Thus, inhibition of Akt affects a step downstream of release from retention (the step regulated by AS160).

DISCUSSION

Glucose transport in fat and muscle is regulated by controlling the relative rates of insertion of Glut4 into the plasma membrane of cells and retrieval of Glut4 from the cell surface. Glut4 trafficking includes at least six processes (Fig. 6A) (31, 32). 1) 1) Glut4 at the plasma membrane is recycled and enters the cell through clathrin-dependent and clathrin-independent mechanisms (endocytosis). 2) Once Glut4 is internalized, it enters endosomes, where it is sorted into small transport vesicles co-localized with markers of the constitutive endocytic pathway (sorting). 3) The constitutive transport vesicles bind to and fuse with the plasma membrane (traffic/fusion). 4) The Glut4 in endosomes is also sorted from the general endocytic markers and packaged into specialized GSVs (sequestration). In basal cells, GSVs do not readily fuse to the plasma membrane. This could be because they are not in proximity to the membrane (i.e. bound to cytoskeletal elements) or because the vesicles are not competent to fuse (i.e. they lack a necessary activated Rab protein or a specific phosphatidylinositol phosphate). 5) In response to insulin, GSVs are released from the retention mechanism, and the vesicles become competent to fuse (are primed for fusion; release). 6) The fusion-competent (primed) GSVs bind to the plasma membrane via specific tethering proteins (tethering/docking/fusion). After tethering, the SNARE proteins are activated by Sec-1/Munc18-like proteins (docking) and the vesicles fuse. Additional steps include biosynthesis and delivery of new Glut4 from the Golgi, and targeting of Glut4 for degradation in lysosomes. Steps 1–3 occur in fibroblasts as well as in adipocytes and likely involve trafficking of Glut4 through the general endocytic pathways. Steps 4–6 are the specialized steps in Glut4 trafficking and are observed only after adipocyte differentiation (2–4).

Each of these steps in Glut4 trafficking is complex and may involve multiple processes and compartments. Despite this, the schematic depicted in Fig. 6A can be modeled mathematically as a series of simple differential equations (see Equations 1–5 under the “Experimental Procedures”). These equations were used to simulate the movement of Glut4 among the compartments by solving them numerically using computing software (Fig. 7). The values for the rate constants used in the simulations (Fig. 6B and Table 1) were selected based on the criteria described (see “Experimental Procedures”). The rate constants for steps 1–4 and 6 were set to experimentally measured values. The rate constants for the release/priming of GSVs and for the reversal of this priming (which we hypothesize is the step regulated by AS160) were determined by fitting the simulations to the measured kinetics data from control cells. The values for the rate constants listed in Table 1 yielded simulated data that were very close to our measured uptake and transition data in control cells (Fig. 7, A and B). Modeling allows the testing of hypotheses about which step(s) in the Glut4 trafficking itinerary are affected by specific treatments (i.e. knockdown or inhibitors). This approach can be used to simulate and test any trafficking diagrams that are drawn, with each arrow in the pathway described by a separate rate constant (30).

Our data are best fit by a “static retention” model, with a single actively cycling pool and a second noncycling pool (2–4). Single exponential fits of the data yield a value for the overall observed exocytic rate constant, kex, and the size of the actively cycling pool. However, if the fits are constrained so that all of the Glut4 must eventually cycle (Ymax = 1.0), our data can also be fit with two exponentials, with a small actively cycling pool (16% of total, kex = 0.016 min−1) and a large pool that is cycling very slowly (84% of total, kex = 0.0007 min−1; t½ >16 h). Our data can be simulated with a “dynamic equilibrium” model (with very slow flux through the sequestration/release pathway under basal conditions instead of no flux through this pathway) if the model includes a bypass route where a small amount of Glut4 can cycle relatively quickly in basal cells (Fig. 6, steps 1–3), although the majority of the Glut4 cycles very slowly (through the sequestered GSVs, steps 4–5) (20). Using the rate constants listed in Table 1, the basal simulations include a small more rapidly cycling pool (15%, kex = 0.01 min−1) and a larger slowly cycling pool (85%, kex = 0.0007 min−1), consistent with the two exponential fits of our measured data.

We hypothesize that the role of AS160 is to reverse the priming of the sequestered GSVs (Fig. 6C). All membrane fusion events require a GTP-loaded Rab protein on the vesicles to initiate the formation of the necessary tethering-docking-fusion complexes (33). Activated Rabs are required to recruit tethering proteins and Sec-1/Munc18-like proteins to fusing vesicles (33). GTP loading is initiated by a guanine nucleotide exchange factor present on the vesicles (the guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Glut4 trafficking is Dennd4C) (34). AS160 contains a Rab GTPase-activating protein domain as well as two phosphotyrosine binding domains (11). The Rab-GAP activity of AS160 is required for its function. If the GTPase-activating protein activity of AS160 is eliminated by mutation of its catalytic arginine 73 to lysine, the dominant negative effect of AS160–4P is relieved (12). In basal cells, AS160 associates with Glut4 vesicles, and targeting of the AS160 GTPase-activating protein domain to Glut4 vesicles (through fusion to Glut4) is sufficient to inhibit Glut4 translocation (35). These data suggest the model that AS160 present on the GSVs inhibits the accumulation of a GTP-loaded Rab required to make the GSVs competent for fusion to the plasma membrane (36). Candidates for this Rab include Rab8, -10, and -14 (17, 37–39). These proteins are found on Glut4 vesicles and are AS160 substrates in vitro (16, 40).

We tested whether the effects of AS160 knockdown on Glut4 trafficking kinetics and steady state distributions could be accounted for by an effect on a single step in the Glut4 trafficking itinerary, reversal of vesicle priming, through reversal of the GTP loading of a required Rab. AS160 knockdown was simulated by decreasing krev from the basal value in the simulations of the control cells (0.12 min−1) to the insulin-stimulated value in control cells (0.007 min−1), leaving all other rate constants unchanged. This decrease in krev would increase cell surface Glut4 3.8-fold (from 1.1 to 4.2% of total), as was observed (Fig. 1). The effect of insulin on AS160 KD cells was simulated by increasing all other rate constants to approximately the insulin-stimulated values in the control simulations (ksort and kseq values were set equal to the slightly slower kex value measured in the AS160 KD cells). This yielded simulated data that very closely matched the measured data for anti-HA uptake (Fig. 7A, solid gray line). Importantly, it very closely matched the measured data in the basal to insulin transition experiments in AS160 KD cells, including the overshoot observed in these cells (Fig. 7B, solid gray line). Thus, decreasing krev in basal cells is sufficient to account for the observed effects of AS160 knockdown on both Glut4 trafficking kinetics at steady state and the transition kinetics. These simulations support the idea that AS160 regulates the sequestration of Glut4 in the storage compartments by reversing the conversion to a primed pre-fusion intermediate. Consistent with this, AS160-4P decreases the rate of Glut4 vesicle tethering/docking but has little effect on vesicle fusion once the vesicles are docked (28, 29).

Several alternative models for AS160 function were considered. Increasing kfus (from 0.01 to 0.08 min−1) increased basal cell surface Glut4 3.9-fold (to 4.3%). It was also sufficient to recapitulate the effect of AS160 knockdown on anti-HA uptake kinetics (Fig. 7A, gray dashed line). However, it could not account for the rapid burst of Glut4 exocytosis observed after insulin stimulation (Fig. 7B). Likewise, increasing cycling through the constitutive pathway by increasing ksort and ktr (to 0.06 and 0.2 min−1) also increased basal cell surface Glut4 (to 3.7%). However, this was not sufficient to account for either the change in uptake kinetics or transition kinetics observed in the AS160 KD cells (Fig. 7A, gray alternating line, and data not shown). In contrast, inhibiting the packaging of Glut4 into the sequestered GSVs (modeled by decreasing kseq from 0.01 to 0.00075 min−1) also resulted in a good fit to our data (Fig. 7, A and B, gray dotted line). In this simulation, we included an effect of insulin on kseq in control cells as well. However, this simulation required including a 4-fold change in ktr, the rate constant of fusion of the constitutive transport vesicles (0.05 min−1 basal to 0.2 min−1 insulin), which is greater than the increases observed for endocytic markers such as the transferrin or α2-macroglobulin receptors (5). One prediction of this model would be a complete shift in Glut4 out of the specialized GSVs into the constitutive endocytic pathway. We see no obvious change in the morphology or distribution of Glut4 vesicles in the AS160 KD cells by fluorescence microscopy (supplemental Fig. 4). There are clearly functional differences, however. The small vesicles distributed throughout the cells are accessible to labeling from the cell surface in basal AS160 KD cells, but they are not labeled in control cells. This suggests that the major difference between knockdown cells and the wild type cells is not where the Glut4 is localized (i.e. GSV versus endosomes) but whether the compartments containing Glut4 are fusion-competent, as would be expected if AS160 inhibited vesicle priming. However, no effect on the distribution or morphology of Glut4-containing vesicles has been described in cells in which other proteins required for sorting and/or retention of Glut4 have been knocked down, including TUG, sortilin, LRP-1, and IRAP (18, 19, 41, 42). Additional work will be required to distinguish whether AS160 regulates release of Glut4 from retention or packaging of Glut4 into the GSVs in the first place. It will be interesting to carefully compare the effect on Glut4 kinetics between knockdown of AS160 and these other proteins to identify whether there are distinguishable phenotypes between proteins that affect packaging and those that affect release.

Inhibitors of PI 3-kinase and Akt affect both the increase of Glut4 in the actively cycling pool and the rate of trafficking of this pool in control cells but only the rate of trafficking in AS160 KD cells. This indicates that there are additional insulin-stimulated PI 3-kinase/Akt substrates involved in Glut4 translocation that regulate the intrinsic rate of trafficking of the vesicles independently of the effects on AS160 (krev). The apparent rate of cycling (kex) at steady state is dependent on the rate of release/priming of the GSVs (krel), and the rate of tethering/docking/fusion of the primed GSVs (kfus). It is also dependent on the rates of movement of Glut4 through the endosomes (sorting and sequestration, ksort and kseq) and on the rate of traffic/fusion of the constitutive TVs (ktr). Accumulating evidence indicates that insulin affects most or all of these rate constants, as is reflected in our choice of rate constants for the simulations (Table 1 and see under “Experimental Procedures”). Previous work has shown that both Akt activity and AS160 phosphorylation are required for the tethering/docking of Glut4 vesicles to the plasma membrane (13, 27, 43). Inhibition of tethering/docking by Akti is due in part to an inhibition of the phosphorylation of AS160, which prevents release of GSVs from retention. However, Akti also prevents the burst of Glut4 exocytosis and overshoot observed after insulin stimulation in the basal to insulin transition experiments in AS160 KD cells (Fig. 5C). Thus, Akti is inhibiting tethering/docking/fusion independently of its effect on AS160 phosphorylation.

The AS160-independent effect of Akti could be through an effect on GSV priming/release (krel) or on the intrinsic rate of tethering/fusion of the vesicles after priming (kfus). Mathematical simulations were used to test these two hypotheses (Fig. 7C). Inhibition of either krel (to 0.006 min−1) or kfus (to 0.012 min−1) is sufficient to account for the ∼50% decrease in steady state surface Glut4 in AS160 cells after insulin stimulation. Combined with an inhibition of the phosphorylation of AS160, which keeps krev high (0.12 min−1), either can account for the 80% decrease seen in surface Glut4 in control cells (an inhibition of either alone is insufficient to account for this 80% decrease). However, an inhibition of the intrinsic rate of fusion by Akti would be expected to significantly slow the kinetics of the basal to insulin transition (Fig. 7C, dotted line), although an inhibition of priming would not (Fig. 7C, solid line). This inhibition was not observed in the transition experiments. Inhibition of kseq, ksort, and/or ktr will decrease cell surface Glut4, but not to the extent observed with Akti unless they are reduced to values that would affect basal surface Glut4, which was not observed (data not shown). Therefore, an effect of Akti on vesicle priming (both through krel and krev) is the only condition in our simulations that completely recapitulates our measured data.

Our simulations indicate that Akt regulates the rate of vesicle tethering/fusion by regulating the concentration of primed, fusion-competent GSVs (36), but not through direct effects on the intrinsic rate constant for tethering/fusion of the primed vesicles with the plasma membrane. In our model, Akt regulates the size of the fusion-competent pool through stimulation of the intrinsic rate of vesicle priming through phosphorylation of an unidentified substrate (a process that includes GTP loading of a Rab). Akt also regulates this pool through inactivation of the Rab-GAP AS160 (decrease in krev) allowing vesicle priming. Several lines of evidence support the idea that the tethering/fusion machinery is also regulated directly by insulin. Our analysis indicates that this is through an Akt-independent process. Identification of both the unidentified Akt-dependent protein that regulates vesicle priming and the Akt-independent insulin-responsive machinery that regulates vesicle tethering and fusion remain important questions in the Glut4 trafficking field.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Joseph Muretta for helpful discussions and for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant DK56197. This work was also supported by grants from the American Diabetes Association.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–4 and mathematical scripts.

- PM

- plasma membrane

- GSV

- Glut4 storage vesicle

- LSM

- low serum media

- LYi

- PI 3-kinase inhibitor LY294002

- MFR

- mean fluorescence ratio

- TV

- constitutive transport vesicle

- PI

- phosphatidylinositol

- SNARE

- soluble NSF attachment protein receptor.

REFERENCES

- 1. Muretta J. M., Mastick C. C. (2009) Vitam. Horm. 80, 245–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Coster A. C., Govers R., James D. E. (2004) Traffic 5, 763–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Govers R., Coster A. C., James D. E. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 6456–6466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Muretta J. M., Romenskaia I., Mastick C. C. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 311–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Habtemichael E. N., Brewer P. D., Romenskaia I., Mastick C. C. (2011) J. Biol. Chem. 286, 10115–10125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Martin O. J., Lee A., McGraw T. E. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 484–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Saltiel A. R., Kahn C. R. (2001) Nature 414, 799–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhou L., Chen H., Xu P., Cong L. N., Sciacchitano S., Li Y., Graham D., Jacobs A. R., Taylor S. I., Quon M. J. (1999) Mol. Endocrinol. 13, 505–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ng Y., Ramm G., Lopez J. A., James D. E. (2008) Cell Metab. 7, 348–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Martin S. S., Haruta T., Morris A. J., Klippel A., Williams L. T., Olefsky J. M. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 17605–17608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kane S., Sano H., Liu S. C., Asara J. M., Lane W. S., Garner C. C., Lienhard G. E. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 22115–22118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sano H., Kane S., Sano E., Mîinea C. P., Asara J. M., Lane W. S., Garner C. W., Lienhard G. E. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 14599–14602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zeigerer A., McBrayer M. K., McGraw T. E. (2004) Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 4406–4415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dash S., Sano H., Rochford J. J., Semple R. K., Yeo G., Hyden C. S., Soos M. A., Clark J., Rodin A., Langenberg C., Druet C., Fawcett K. A., Tung Y. C., Wareham N. J., Barroso I., Lienhard G. E., O'Rahilly S., Savage D. B. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 9350–9355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eguez L., Lee A., Chavez J. A., Miinea C. P., Kane S., Lienhard G. E., McGraw T. E. (2005) Cell Metab. 2, 263–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Larance M., Ramm G., Stöckli J., van Dam E. M., Winata S., Wasinger V., Simpson F., Graham M., Junutula J. R., Guilhaus M., James D. E. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 37803–37813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sano H., Eguez L., Teruel M. N., Fukuda M., Chuang T. D., Chavez J. A., Lienhard G. E., McGraw T. E. (2007) Cell Metab. 5, 293–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jordens I., Molle D., Xiong W., Keller S. R., McGraw T. E. (2010) Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 2034–2044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yu C., Cresswell J., Löffler M. G., Bogan J. S. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 7710–7722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Xu Y., Rubin B. R., Orme C. M., Karpikov A., Yu C., Bogan J. S., Toomre D. K. (2011) J. Cell Biol. 193, 643–653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Muretta J. M., Romenskaia I., Cassiday P. A., Mastick C. C. (2007) J. Cell Sci. 120, 1168–1177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Perera H. K., Clarke M., Morris N. J., Hong W., Chamberlain L. H., Gould G. W. (2003) Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 2946–2958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Proctor K. M., Miller S. C., Bryant N. J., Gould G. W. (2006) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 347, 433–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dawson K., Aviles-Hernandez A., Cushman S. W., Malide D. (2001) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 287, 445–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yang J., Holman G. D. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 4600–4603 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lampson M. A., Schmoranzer J., Zeigerer A., Simon S. M., McGraw T. E. (2001) Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 3489–3501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gonzalez E., McGraw T. E. (2006) Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 4484–4493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jiang L., Fan J., Bai L., Wang Y., Chen Y., Yang L., Chen L., Xu T. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 8508–8516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bai L., Wang Y., Fan J., Chen Y., Ji W., Qu A., Xu P., James D. E., Xu T. (2007) Cell Metab. 5, 47–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Holman G. D., Lo Leggio L., Cushman S. W. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 17516–17524 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Slot J. W., Geuze H. J., Gigengack S., Lienhard G. E., James D. E. (1991) J. Cell Biol. 113, 123–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ramm G., Slot J. W., James D. E., Stoorvogel W. (2000) Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 4079–4091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ohya T., Miaczynska M., Coskun U., Lommer B., Runge A., Drechsel D., Kalaidzidis Y., Zerial M. (2009) Nature 459, 1091–1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sano H., Peck G. R., Kettenbach A. N., Gerber S. A., Lienhard G. E. (2011) J. Biol. Chem. 286, 16541–16545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stöckli J., Davey J. R., Hohnen-Behrens C., Xu A., James D. E., Ramm G. (2008) Mol. Endocrinol. 22, 2703–2715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Koumanov F., Richardson J. D., Murrow B. A., Holman G. D. (2011) J. Biol. Chem. 286, 16574–16582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ishikura S., Klip A. (2008) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 295, C1016–C1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sano H., Roach W. G., Peck G. R., Fukuda M., Lienhard G. E. (2008) Biochem. J. 411, 89–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ishikura S., Bilan P. J., Klip A. (2007) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 353, 1074–1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mîinea C. P., Sano H., Kane S., Sano E., Fukuda M., Peränen J., Lane W. S., Lienhard G. E. (2005) Biochem. J. 391, 87–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jedrychowski M. P., Gartner C. A., Gygi S. P., Zhou L., Herz J., Kandror K. V., Pilch P. F. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 104–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shi J., Kandror K. V. (2005) Dev. Cell 9, 99–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lopez J. A., Burchfield J. G., Blair D. H., Mele K., Ng Y., Vallotton P., James D. E., Hughes W. E. (2009) Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 3918–3929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.