Abstract

Cilia and flagella are complex structures emanating from the surface of most eukaroytic cells and serve important functions including motility, signaling, and sensory reception. A process called intraflagellar transport (IFT) is of central importance to ciliary assembly and maintenance. The IFT complex is required for this transport and consists of two distinct multisubunit subcomplexes, IFT-A and IFT-B. Despite the importance of the IFT complex, little is known about its overall architecture. This paper presents a biochemical dissection of the molecular interactions within the IFT-B core complex. Two stable subcomplexes consisting of IFT88/70/52/46 and IFT81/74/27/25 were recombinantly co-expressed and purified. We identify a novel interaction between IFT70/52 and map the interaction domains between IFT52 and the other subunits within the IFT88/70/52/46 complex. Additionally, we show that IFT52 binds directly to the IFT81/74/27/25 complex, indicating that it could mediate the interaction between the two subcomplexes. Our data lead to an improved architectural map for the IFT-B core complex with new interactions as well as domain resolution mapping for several subunits.

Keywords: Intracellular Trafficking, Protein Chemistry, Protein Domains, Protein Motifs, Protein Purification, Protein-Protein Interactions, IFT Complex, Cilium, Domain Mapping, Intraflagellar Transport

Introduction

Cilia and flagella (interchangeable terms) are tail-like projections that protrude from the surface of most eukaryotic cells with the exception of fungi and higher plants (1). They consist of a microtubule-based axoneme that grows from a basal body anchored in the cell and is surrounded by the ciliary membrane, which contains a distinct composition of lipids and membrane proteins (2). In agreement with important functions of the cilium in sensory reception and signal transduction (3–5), defects in the assembly and maintenance of cilia have been identified as the cause of a large number of human syndromes, now commonly referred to as “ciliopathies,” with phenotypes including blindness, deafness, respiratory defects, kidney defects, obesity, developmental abnormalities, and infertility (6).

Of central importance for the assembly and maintenance of cilia is a process called intraflagellar transport (IFT),3 the bidirectional movement of proteins from the base to the tip of the cilium (anterograde transport) and from the tip back to the base (retrograde transport) (7). This process was first identified microscopically in the flagella of the single-celled green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (8), and it was later shown by electron microscopy that “trains” of IFT particles move between the ciliary membrane and the underlying axonemal outer doublet microtubules (9). The driving force for this movement is provided by motor proteins that were identified as heterotrimeric kinesin II for anterograde transport (9–11) and cytoplasmic dynein 1b for retrograde transport (12–15).

The IFT particles contain arrays of the so-called IFT complex that consists of two distinct subcomplexes, IFT-A and IFT-B, containing at least 6 and 14 subunits, respectively (10, 16–22). A more detailed analysis of the IFT-B complex in Chlamydomonas showed that it can be further reduced to an IFT-B “core” complex containing IFT88/81/74/52/46/27 (23) and most likely also IFT70 (19) and IFT25 (17, 18) which were identified later. The importance of the IFT-B core components is highlighted by numerous examples showing that these proteins are absolutely required for the formation of cilia/flagella in Chlamydomonas as well as higher eukaryotes (24–27).

Within the IFT-B core complex, a number of direct interactions between individual subunits have been identified and include IFT81/74 (23), IFT88/52/46 (28), IFT70/46 (19), and IFT27/25 (18). However, much less is known about the individual regions of the proteins that mediate these interactions. Very little is also known at the structural level where IFT27/25 currently represents the only subcomplex with an available high resolution structure (29).

In this study we provide insights into the overall IFT-B core architecture by recombinant expression and purification of novel IFT subcomplexes consisting of pentameric IFT81/74/52/27/25, tetrameric IFT88/70/52/46 and IFT81/74/27/25, trimeric IFT70/52/46, or dimeric IFT70/52. Using limited proteolysis followed by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC), we identify minimal domains required for complex formation. These data show that IFT52 is central to the IFT-B core because it interacts directly with at least four other proteins within the complex. The mapping of the regions responsible for these contacts allows us to propose a refined interaction map for the IFT-B core complex that will serve as a starting point for high resolution structural studies.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cloning and Protein Expression in Escherichia coli

Full-length IFT genes and corresponding fragments were cloned into pEC vectors containing various N-terminal tags and genes conferring resistance to either kanamycin (pEC-K-His, pEC-K-GST, and pEC-K-CBP), ampicillin (pEC-A-His and pEC-A-SUMO), or streptomycin (pEC-S-His) using ligation-independent cloning. These pEC vectors were created at the Department for Structural Cell Biology at the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry (details available upon request). Untagged IFT46 and IFT81 were cloned into the pET-MCN vector containing a chloramphenicol-resistance gene (30). Recombinant proteins were expressed using E. coli BL21(DE3) (Invitrogen) grown in terrific broth medium and induced overnight at 18 °C with 0.5 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside. 50-ml culture volumes were used for small scale expression tests and pulldowns. 6-liter cultures were grown for large scale purifications.

Cloning and Protein Expression in Insect Cells

Full-length IFT genes were cloned either with or without N-terminal tags (His6/tobacco etch virus) into the pFastBac1 vector (Invitrogen). Recombinant viral DNA was produced by transformation of this plasmid into DH10Bac cells (Invitrogen) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. The obtained viral genome was used to transfect Sf21 insect cells, which were also subsequently used to produce large amounts of recombinant viruses. Expression of protein complexes was carried out in High Five cells (Invitrogen) by co-infection of 3 liters of cell suspension (106 cells/ml) with a combination of viruses (appropriate viral ratios were first determined empirically in small scale experiments).

Protein Purification

6-liter cultures of E. coli typically yielded a cell pellet volume of 100 ml, whereas 3-liter insect cell cultures yielded 30 ml. The pellets were resuspended in either the same volume (for E. coli; 100 ml) of lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, supplemented with 1 mg of DNase I (1 ml of a 1 mg/ml stock solution) and 1 mm PMSF), or 5 volumes (for insect cells, 150 ml) of the same buffer, and cells were lysed by sonication (total energy typically 27 kJ for E. coli or 15 kJ for insect cells). From this step onward, all procedures were the same for purifications from both E. coli and insect cells. The lysate was cleared by centrifugation for 1 h at 25,000 rpm using a JA-25.50 rotor (BeckmanCoulter), and His-tagged proteins were purified by binding to a Ni2+-NTA column and elution with lysis buffer containing imidazole. In cases where GST-tagged proteins were present in the complex, the obtained imidazole elutions were loaded on a GSH column in lysis buffer, and the bound material was eluted with lysis buffer containing 20 mm glutathione. Fractions containing the protein(s) of interest were dialyzed overnight at room temperature against buffer A (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mm DTT) either in the presence or absence of tobacco etch virus protease. In the case of tag cleavage, the resulting solution was put back on a Ni2+-NTA column to remove the tag. For both heparin and ion-exchange chromatography the protein was loaded on the column in buffer A and then eluted with a linear gradient from buffer A to buffer B (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 m NaCl, 10% glycerol), and the resulting protein-containing fractions were concentrated and loaded on a size-exclusion column (HiLoad Superdex75, HiLoad Superdex200, Superdex200, or Superose6) in gel-filtration buffer (10 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, and 1 mm DTT). Proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and the identities of the proteins confirmed by MS.

Limited Proteolysis

For small scale tests with various proteases (trypsin, elastase, subtilisin, Glu-C, chymotrypsin), serial dilutions (1/10, 1/100, 1/1000) of the protease stocks (1 mg/ml) were prepared using protease dilution buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, 10 mm MgSO4). 10 μl of a dilution of the protein complex to be examined (0.6 mg/ml in protease dilution buffer) was incubated with 3 μl of protease dilution for 30 min (either on ice or at room temperature), and the resulting fragments were examined by SDS-PAGE. Promising conditions (those that led to the appearance of proteolysis-resistant fragments) were chosen for large scale time course studies. Based on this time course, a suitable time point was chosen at which the proteolyzed complex was subjected to SEC. Fragments that co-purified were identified by SDS-PAGE and determination of the intact mass by MS (carried out by the Max Planck Institute core facility), followed by bioinformatic analysis using the FindPept tool on the ExPASy website.

GST Pulldown Experiments

Proteins were co-expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells overnight at 18 °C with 0.5 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside. The culture volume was 50 ml, typically yielding 1 ml of cell pellet. These pellets were resuspended in 2 ml of lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol) and opened by sonication. The supernatants after centrifugation were incubated with GSH beads to pull down GST-tagged proteins and interaction partners. Beads were washed using the lysis buffer, and the remaining protein was eluted with lysis buffer containing 30 mm glutathione. Analysis of the pulldowns was carried out using SDS-PAGE.

RESULTS

Purification of Tetrameric IFT88/70/52/46, Trimeric IFT70/52/46, and Dimeric IFT70/52 Complexes

We initially overexpressed all eight subunits of the Chlamydomonas IFT-B core complex as individual proteins in E. coli, but because of low solubility and degradation problems only two subunits could be purified (IFT46 and IFT25; data not shown). We thus turned to co-expression of IFT subunits in E. coli using plasmids with different antibiotic resistance genes. Given the previously published interactions between IFT88/52/46 (28) and IFT70/46 (19), it follows that a tetrameric IFT88/70/52/46 complex is likely to exist. Co-expression in E. coli from four different plasmids with various N-terminal tags (GST-IFT88, His-IFT70, His-IFT52, and untagged IFT46) allowed for the soluble expression of all four components. Purification was carried out using a combination of affinity, ion-exchange, and SEC (as outlined in Fig. 1a). This procedure led to the purification of a tetrameric complex containing all four proteins (Fig. 1b) as confirmed by MS. As the proteins co-eluted in several chromatographic steps, including SEC, they form a stable complex. The subunits appear to be present in stoichiometric amounts judging from SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1b).

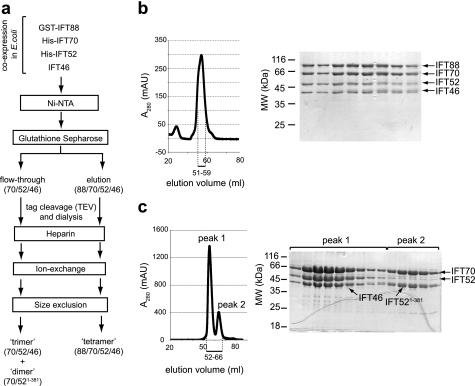

FIGURE 1.

Co-expression and purification of recombinant IFT88/70/52/46, IFT70/52/46, and IFT70/52(1–381) complexes. a, overview of the purification procedure including Ni2+-NTA, glutathione-Sepharose, heparin, ion-exchange (Mono Q), and size-exclusion chromatography. The vectors used for co-expression of these proteins were pEC-K-GST-IFT88, pEC-S-His-IFT70, pEC-A-His-IFT52, and pETMCN-IFT46. TEV, tobacco etch virus. b, HiLoad Superdex200 chromatogram and Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel of the peak fractions, showing a tetrameric IFT88/70/52/46 complex obtained from the GSH elution. Elution volumes analyzed by SDS-PAGE are indicated with a bar below the chromatogram. c, HiLoad Superdex200 chromatogram and Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel of the peak fractions showing a trimeric IFT70/52/46 and dimeric IFT70/IFT52(1–381) complex obtained from the GSH flow-through. Elution volumes analyzed by SDS-PAGE are indicated with a bar below the chromatogram.

GST-IFT88 proved to be expressed to a much lower degree than the other three proteins, resulting in a mixture of lower order complexes in the lysate. Consequently, by including a GSH-affinity step (to capture GST-tagged IFT88) in the IFT88/70/52/46 purification, the large excess of IFT46, IFT52, and IFT70 was found in the flow-through. After further purification of this fraction, two peaks eluted from SEC (Fig. 1c). The first peak contained full-length components of all three proteins as confirmed by MS, and the complex appeared stoichiometric as judged from SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1c). The second peak contained only two proteins (Fig. 1c). MS total mass analysis showed that this subcomplex contained full-length IFT70 and a degradation product of IFT52 (IFT52(1–381)), demonstrating that IFT70 not only binds directly to IFT46 (19) but also to IFT52. To investigate this interaction further, IFT70 and IFT52 were co-expressed in E. coli and purified in large scale. IFT52 and IFT70 were seen to co-elute in four different purification steps, indicating a stable complex. From the last SEC purification step, two distinct peaks were obtained (Fig. 2a). Although MS showed that the first and minor peak contained mainly the full-length proteins, the second, major peak again contained full-length IFT70 in complex with the IFT52(1–381) fragment. We were never able to purify full-length IFT52 or IFT70 alone, mainly because of the low solubility of IFT70 and a pronounced tendency of IFT52 to degrade. The fact that co-expression of IFT70 and IFT52 protected a region of residues 1–381 of IFT52 from degradation indicated that this region of IFT52 could be responsible for the IFT70 interaction. In conclusion, IFT88/70/52/46 and IFT70/52/46 form stable tetrameric and trimeric complexes, respectively, that can be recombinantly expressed and purified, and IFT52 interacts directly with IFT70.

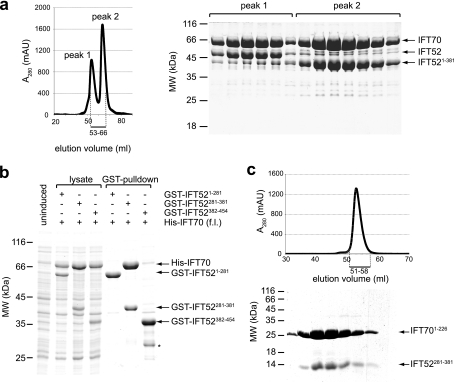

FIGURE 2.

Co-expression and purification of dimeric IFT70/52 complexes and mapping of the interaction domains. a, HiLoad Superdex200 chromatogram and Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel of the peak fractions, showing the purification of IFT70/52 and IFT70/IFT52(1–381) complexes. Elution volumes analyzed by SDS-PAGE are indicated with a bar below the chromatogram. The vectors used for co-expression were pEC-S-His-IFT70 and pEC-A-His-IFT52. b, GST pulldowns showing a direct interaction between GST-IFT52(281–381) and full-length (f.l.) His-IFT70 after co-expression in E. coli. The first four lanes show total bacterial lysate, and the last three lanes show the GST-pulldowns between GST-IFT52(1–281), GST-IFT52(281–381), and GST-IFT52(382–454) with His-IFT70. c, HiLoad Superdex75 chromatogram and Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel of the peak fractions showing the purification of a “minimal” IFT70(1–226)/IFT52(281–381) complex. Elution volumes analyzed by SDS-PAGE are indicated with a bar below the chromatogram. In both b and c, IFT70 (either full-length or fragment) was expressed from the pEC-S-His vector, whereas the IFT52 fragment was expressed from the pEC-K-GST vector.

IFT52(281–381) and IFT70(1–226) Fragments Form a Stable Complex

To identify the regions of IFT52 and IFT70 necessary for the interaction between these two proteins more precisely, the IFT52(1–381)/70 complex (Fig. 2a) was subjected to limited proteolysis followed by SEC. Proteolysis with elastase at 0 °C left IFT70 intact, whereas IFT52 was degraded to an ∼100-amino acid fragment that co-eluted with full-length IFT70 in SEC (data not shown). This 100-amino acid fragment of IFT52 was identified by MS total mass analysis as residues 281–381, suggesting that IFT52(281–381) could constitute a minimal IFT52 region for the interaction with IFT70. To confirm that the central region of IFT52 but not the N-terminal or C-terminal parts are responsible for the binding to IFT70, we cloned three N-terminally GST-tagged versions of IFT52 based on the results from limited proteolysis (see Fig. 3a). Each of these three fragments (GST-IFT52(1–281), GST-IFT52(281–381), and GST-IFT52(382–454)) was co-expressed with His-IFT70 in E. coli and the GST tag used to pull down proteins from the extract (Fig. 2b). This experiment confirmed that only the central IFT52 region (IFT52(281–381)) and not the N- or C-terminal parts of IFT52 could efficiently solubilize and pull down IFT70 (Fig. 2b). Large scale expression and purification of IFT70/52(281–381) confirmed that this fragment of IFT52 binds strongly to IFT70 and co-eluted as a complex in SEC (supplemental Fig. S1). We therefore conclude that IFT52(281–381) represents the IFT70-interacting region of the IFT52 protein.

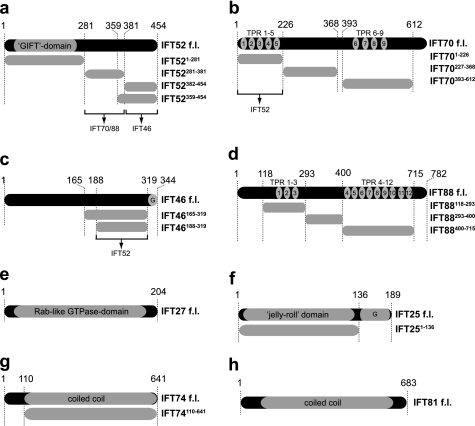

FIGURE 3.

Schematic representation of the IFT proteins and truncations used in this study. Cloned truncations are shown below the respective full-length (f.l.) protein. a, IFT52 contains a GIFT domain in the N-terminal half. The IFT52(281–381) fragment was found to bind to both IFT88 and IFT70, the IFT52(382–454) fragment was found to interact with IFT46 (for details, see “Results”). b, IFT70 contains nine predicted TPRs. The IFT70(1–226) fragment was found to interact with IFT52 (for details, see “Results”) c, the IFT46 protein does not contain any recognizable domains. The IFT46(188–319) fragment was found to bind to IFT52 (for details, see “Results”). A glycine-rich C-terminal stretch is denoted with G. d, IFT88 contains 12 predicted TPRs. e, IFT27 is a Rab-like GTPase. f, IFT25 contains a jelly roll domain and a glycine-rich C-terminal extension denoted with G. g and h, IFT74 (g) and IFT81 (h) are predicted to be coiled-coil proteins.

With a minimal IFT70-interacting fragment of IFT52 mapped, we proceeded to map the region(s) of IFT70 responsible for IFT52 interaction. According to the program TPRPRED (31), IFT70 is predicted to contain 9 α-helical tetratricopeptide repeats (TPRs) (Fig. 3b) often found to mediate protein-protein interactions. To map the region on IFT70 responsible for the interaction with IFT52, limited proteolysis was carried out on the purified IFT70/52(281–381) complex. As previously mentioned, IFT70 was resistant to proteolysis with elastase at 0 °C, but further experiments at room temperature allowed us to identify three fragments (for MS identification of IFT52 and IFT70 fragments, see supplemental Fig. S2) spanning most of the IFT70 sequence. Because the IFT52(281–381) fragment could not be identified to co-elute in SEC with any of the IFT70 fragments after proteolysis at room temperature, all three IFT70 fragments (IFT70(1–226), IFT70(227–368), and IFT70(393–612); see Fig. 3b) were cloned and tested individually for binding to IFT52(281–381). Each of these His-tagged IFT70 fragments proved to be insoluble when expressed alone in E. coli as observed for full-length His-IFT70. However, co-expression of each of the fragments with IFT52(281–381) revealed that only the N-terminal region became soluble, suggesting an IFT70(1–226)/IFT52(281–381) interaction (not shown). Additionally, neither IFT52(1–281) nor IFT52(382–454) was able to solubilize any of the IFT70 fragments, indicating that they do not interact (data not shown). To verify the IFT70(1–226)/IFT52(281–381) interaction, large scale purification of His-IFT70(1–226)/GST-IFT52(281–381) was carried out and showed that the two fragments co-purified during five chromatographic steps, demonstrating a strong interaction (Fig. 2c). These results suggest that the IFT70/52 interaction can be recapitulated by a minimal complex consisting of IFT70(1–226) and IFT52(281–381).

The C-terminal IFT52(382–454) and IFT46(188–319) Fragments Interact Directly

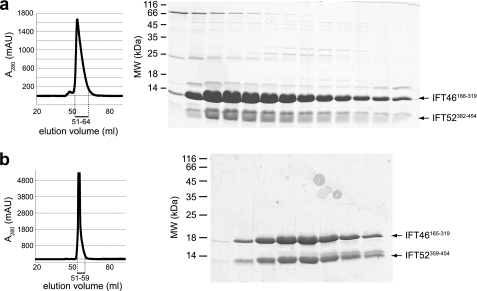

IFT46 and IFT52 were previously shown to interact in two-hybrid screens, and the interaction was confirmed with recombinantly co-expressed proteins (28). Additional co-purifications with truncated IFT46 and IFT52 proteins successfully mapped the interaction to the C-terminal region of both binding partners (28). More specifically, an IFT52(258–454) fragment still bound to IFT46, whereas an IFT46(198–344) fragment showed binding to IFT52 (28). Another study identified a direct interaction between IFT46 and IFT70, but the interaction regions were not mapped further (19). To gain insights into the interactions within the IFT70/52/46 trimer, the purified complex (see Fig. 1c) was subjected to limited proteolysis and SEC to identify a minimal IFT70/52/46 core (supplemental Fig. S3). MS total mass analyses on the co-purified, proteolyzed IFT70/52/46 complex revealed the presence of full-length IFT70, an IFT52 fragment comprising residues 281–454, and an IFT46 fragment spanning residues 154–319. IFT46 thus appears to protect the C-terminal region of IFT52 that was proteolyzed in the case of the IFT70/52 complex (see above), indicating that IFT52(382–454) could be responsible for the interaction with IFT46 in agreement with previously published data (28). To explore this further, the C-terminal GST-IFT52(382–454) fragment (see Fig. 3a) was co-expressed with an IFT46 fragment containing residues 188–319 (Fig. 3c). This IFT46(188–319) fragment is similar to the IFT46 fragment shown to bind IFT52 in a previous study (28) but contains 10 residues more on the N terminus and lacks a glycine-rich region at the C terminus that is predicted to be disordered by the DISOPRED server (32). IFT46(188–319) and IFT52(382–454) co-purified as a complex (Fig. 4a) in large scale preparations, but relatively low protein expression and a tendency to aggregate during purification procedures indicated that the complex is not completely stable and might be missing parts of the domain structures. Bioinformatic analysis, including secondary structure prediction and homology to proteins of known structure, indicated that slightly longer versions of IFT46 and IFT52 are needed to include complete domains. IFT46(165–319) (Fig. 3c) and IFT52(359–454) (Fig. 3a) constructs were subsequently cloned and the two fragments co-expressed and purified. The resulting IFT46(165–319)/IFT52(359–454) complex was highly soluble and purified as a stable complex (Fig. 4b). These results demonstrate, in agreement with previously published data (28), that the C-terminal domains of IFT46 and IFT52 are responsible for the interaction between the two proteins within the IFT-B core complex. Although this interaction can be recapitulated by the shorter IFT46(188–319) and IFT52(382–454) truncations, our data indicate that the longer IFT46(165–319) and IFT52(359–454) truncations form a much more stable complex and may constitute proper domains of the proteins.

FIGURE 4.

Co-expression and purification of minimal IFT52/IFT46 complexes. a, HiLoad Superdex75 chromatogram and Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel of the peak fractions showing the purification of a minimal IFT52(382–454)/IFT46(188–319) complex. Elution volumes analyzed by SDS-PAGE are indicated with a bar below the chromatogram. The proteins form a stable complex, but the relatively low yield; the asymmetry of the elution peak and the presence of many contaminants suggest that these fragments do not represent stable domains. b, HiLoad Superdex75 chromatogram and Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel of the peak fractions showing the purification of a minimal IFT52(359–454)/IFT46(165–319) complex. Elution volumes analyzed by SDS-PAGE are indicated with a bar below the chromatogram. This complex containing slightly longer fragments than the ones shown in a leads to the purification of a much cleaner complex at higher yield, suggesting that these fragments represent stable domains of the proteins. In both a and b the IFT52 fragment was expressed from the pEC-A-His vector, and the IFT46 fragment was expressed from the pEC-K-His vector.

IFT52(281–381) Interacts Directly with IFT88

IFT88 was previously shown to interact directly with both IFT46 and IFT52, but the interactions have not been mapped further (28). It is currently not known if IFT88, in addition to these interactions, also binds directly to IFT70. As for IFT70, IFT88 is predicted to be a TPR protein and contains 12 potential TPRs between residues 185–710 (Fig. 3d). To map the region of IFT52 that interacts with IFT88, we co-expressed each of the three GST-tagged fragments of IFT52 used for analysis of the interaction with IFT70 (see Figs. 3a and Fig. 2b) with SUMO-tagged full-length IFT88. The pulldown showed that the central IFT52(281–381), but not the other two fragments of IFT52, solubilized and pulled down IFT88 (Fig. 5a). To confirm this interaction we attempted to purify a SUMO-IFT88(full-length)/GST-IFT52(281–381) complex. As shown in Fig. 5b, a stoichiometric complex was obtained after three chromatographic steps, including SEC. We next asked which region of IFT88 was responsible for IFT52 binding. Attempts to perform limited proteolysis on any IFT88-containing complex failed due to heavy precipitation of putative IFT88 fragments (data not shown). Three fragments spanning most of the IFT88 protein were thus constructed based purely on secondary structure prediction as depicted in Fig. 3d. None of these fragments could, however, be solubilized or pulled down by any of the IFT52 fragments (Fig. 3a) (data not shown), and we were thus unable to refine the IFT52-interacting region of IFT88 further. The results from Fig. 5, however, demonstrate that the central region of IFT52 appears to have a dual role in binding directly to both IFT70 and IFT88. Further studies are needed to obtain information on which part of IFT88 binds directly to IFT52.

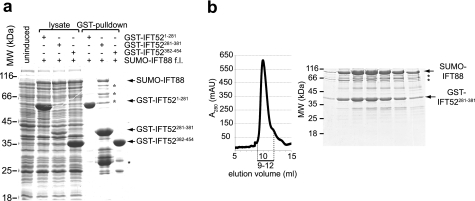

FIGURE 5.

IFT52(281–381) binds to IFT88. a, GST pulldowns showing a direct interaction between GST-IFT52(281–381) and full-length (f.l.) SUMO-IFT88 after co-expression in E. coli. The first four lanes show total bacterial lysate, and the last three lanes show the GST pulldowns between GST-IFT52(1–281), GST-IFT52(281–381), and GST-IFT52(382–454) with SUMO-IFT88. Degradation fragments are marked with asterisks. b, Superdex200 chromatogram and Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel of the peak fractions showing the purification of a SUMO-88/GST-IFT52(281–381) complex. Elution volumes analyzed by SDS-PAGE are indicated with a bar below the chromatogram. Degradation fragments of SUMO-88 are marked with asterisks. In both a and b IFT88 was expressed from the pEC-A-SUMO vector, and the IFT52 fragment was expressed from the pEC-K-GST vector.

Direct Interaction between IFT81/74 and IFT52, a Bridge between Tetrameric Subcomplexes of the IFT-B Core?

The salt-stable IFT-B core complex contains, in addition to the IFT46, IFT52, IFT70, and IFT88 proteins discussed above, the subunits IFT25, IFT27, IFT(74/72), IFT81, and possibly IFT22. IFT72 is a truncated version of IFT74 that may represent a degradation product and will be referred to as IFT74. IFT25 is known to interact directly with IFT27 (17, 18, 33), and the recently determined crystal structure revealed a heterodimeric IFT27/25 complex with a conserved interaction interface (29). IFT74 and IFT81 are also known to interact in yeast two-hybrid experiments and have been suggested to form an (IFT74)2(IFT81)2 heterotetramer (23), although the quaternary state of these proteins in the context of the entire IFT complex remains to be verified. This IFT81/74 complex was successfully purified using maltose-binding protein-tagged IFT81 and His-tagged IFT74 by Cole and co-workers (34). IFT74 and IFT81 are both predicted to be coiled-coil proteins (using the program COILS) (35) with a stretch of ∼120 residues at the N termini not predicted as coiled-coils (Fig. 3, g and h). The binding domains between the two proteins have been mapped to these coiled-coil regions (23). Additionally, a possible interaction between IFT27 and IFT81 was suggested based on chemical cross-linking and MS analysis (28), but this interaction has not been further confirmed. To test whether IFT27/25 and IFT81/74 form a stable complex, we attempted to assemble it from recombinant subcomplexes. Whereas IFT27/25 could be readily produced in large amounts (29), the full-length IFT81/74 subcomplex was insoluble in our hands, preventing its purification. We thus co-expressed all four proteins (His-IFT74(110–641), untagged full-length IFT81, full-length calmodulin-binding protein (CBP)-IFT27, His-IFT25(1–136)) in E. coli using four different plasmids. The N-terminal part of IFT74 is predicted to be disordered (32) and was consequently removed. Similarly, the IFT25(1–136) construct is lacking the glycine-rich C terminus that is not conserved, is predicted to be disordered, and is not required for the interaction with IFT27 (29). Large scale purification by Ni-NTA affinity, Q-Sepharose ion-exchange, and SEC resulted in the isolation of this IFT81/74(110–641)/27/25(1–136) complex (Fig. 6a). SDS-PAGE of the elution fraction from SEC showed that IFT74 tends to proteolyze, which gave rise to a broad elution profile in SEC (Fig. 6a). The elution profile furthermore displays a pronounced shoulder, which may indicate a mixture of oligomeric states of this complex. The results from this purification demonstrate that IFT27/25 interacts directly with IFT81/74 and that the interaction does not depend on the C-terminal extension of Chlamydomonas IFT25 or the N-terminal 109 residues of IFT74.

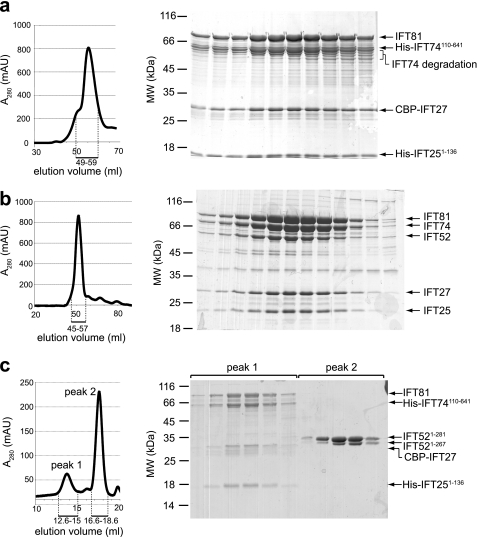

FIGURE 6.

Purification of tetrameric IFT81/74/27/25 and pentameric IFT81/74/52/27/25 complexes. a, HiLoad Superdex200 chromatogram and Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel of the peak fractions showing an IFT81/74(110–641)/27/25(1–136) complex purified from E. coli, confirming that the IFT81/74 and IFT27/25 subcomplexes can bind to each other. Elution volumes analyzed by SDS-PAGE are indicated with a bar below the chromatogram. The vectors used were pETMCN-IFT81 (chloramphenicol resistance), pEC-A-His-IFT74(110–641), pEC-K-CBP-IFT27, and pEC-S-His-IFT25(1–136). b, HiLoad Superdex200 chromatogram and Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel of the peak fractions showing an IFT81/74/52/27/25 complex (all full-length proteins) purified from insect cells, confirming that IFT52 can bind to the IFT81/74/27/25 tetramer. Elution volumes analyzed by SDS-PAGE are indicated with a bar below the chromatogram. c, Superose6 chromatogram and Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel of the peak fractions, showing that a purified IFT52(1–281) cannot bind to recombinant IFT81/74(110–641)/27/25(1–136) purified from E. coli. Elution volumes analyzed by SDS-PAGE are indicated with a bar below the chromatogram.

To investigate whether IFT52 binds directly to IFT81/74/27/25, we tested whether all five proteins can form a stable complex. Because we were unable to co-express more than four proteins using our E. coli expression setup, we turned to baculovirus-infected insect cells to co-express full-length versions of all five His-IFT81/74/His-52/His-27/25 proteins. Large scale purification clearly produced a stable pentameric complex (Fig. 6b), showing that IFT52 interacts directly with the IFT81/74/25/27 tetramer and could thus serve to bridge the two tetrameric complexes of the octameric IFT-B core. It should be noted that IFT52 was expressed to a lower degree than the other four proteins and may not be present in stoichiometric amounts (see Fig. 6b). Because both purified IFT27/25 and IFT88/70/52/46 were available, we incubated these two subcomplexes and carried out SEC, which resulted in two clearly separated peaks, demonstrating that IFT27/25 and IFT88/70/52/46 do not form a stable complex (supplemental Fig. S4). From these experiments we conclude that IFT52 most likely interacts with IFT81/74, although we are currently unable to verify this in direct protein-protein interaction experiments because of the lack of purified IFT81/74 complex. Additionally, we sought to map the region of IFT52 responsible for the interaction with the IFT81/74/27/25 tetramer. Full-length IFT52 or C-terminal parts of the protein were insoluble or prone to degradation in our hands and could thus not be purified. The N-terminal part of IFT52 (residues 1–281), however, was highly soluble and could be purified. To test whether this IFT52(1–281) fragment can still bind to IFT81/74/27/25, the proteins were mixed and subjected to SEC (Fig. 6c). The result from this experiment showed that IFT52(1–281) does not bind to IFT81/74/27/25, even though this fragment was added in excess. Because we observed strong binding of full-length IFT52, but no binding of IFT52(1–281), we conclude that the C-terminal IFT52(282–454) region mediates the binding of IFT52 to the IFT81/74/27/25 tetramer. It is currently not known whether this interaction between IFT81/74 and IFT52 represents the only bridge between the IFT88/70/52/46 and IFT81/74/27/25 tetrameric complexes within the IFT-B core or whether other subunits may form additional interactions. However, the numerous stable interactions between IFT52 and the other subunits of the IFT88/70/52/46 subcomplex as well as the strong interaction between IFT52 and IFT81/74/27/25 tetramer suggests that IFT52 could have a key role in IFT-B core complex stability.

DISCUSSION

The C-terminal Half of IFT52 Mediates the Interaction with at Least Four Different IFT-B Subunits

IFT52 was originally identified as part of the IFT-B complex (36) and later shown to belong to a salt-stable IFT-B core complex (23). IFT52 localizes to the basal body transition fibers in Chlamydomonas (24), and its knock-out (bld1 mutant) results in “bald cells” unable to assemble flagella (37), highlighting the importance of IFT52 in ciliogenesis. In a similar manner, mutation of IFT52 in C. elegans (osm-6 mutant) disrupts the function of sensory cilia (38, 39). In this paper, we show that IFT52 is at the heart of the IFT-B core complex formation as it interacts with at least four other core subunits. The biochemical mapping of the interacting regions allows us to propose a significantly improved interaction map for the IFT-B core complex including the novel interactions between IFT70/52 and IFT81/74/52 (Fig. 7). The numerous interactions between IFT52 and other core subunits provide a rationale for the severe phenotype observed in the bld1 mutant. In the absence of IFT52 the entire IFT-B core may fail to assemble correctly. Any attempts to produce a trimeric IFT88/70/46 complex lacking IFT52 failed to deliver soluble complex, suggesting that IFT52 is indeed needed for complex formation (data not shown). Curiously, all of the interactions of IFT52 with other IFT proteins mapped to the C-terminal half of IFT52 (residues 281–454). High resolution structural studies will be needed to unravel how this region is able to mediate the direct binding to the IFT46, IFT70, and IFT88 subunits, as well as to the IFT81/74 subcomplex. The N-terminal 281 residues of IFT52 do not appear to be crucial for the interactions within the IFT-B core, and their function is currently unknown. Because the mapping of protein interactions within the IFT complex presented here is by no means exhaustive, there is of course the possibility that the IFT52 N-terminal part participates in the binding to other IFT subunits. A bioinformatics study predicts that this region contains a GIFT (flavobacterial gliding protein GldG+IFT52) domain (residues 25–250; see Fig. 3a) (40). This IFT52 GIFT domain displays low but significant sequence homology to a number of sugar-binding proteins such as the eukaryotic oligosaccharyl-transferase complex and the subtilisin kexin isoenzyme-1 (40). However, the putative sugar binding properties of IFT52 have not been experimentally investigated. To this end we purified IFT52(1–281) and tested for sugar binding in a glycan microarray screen containing 511 different glycans (Consortium for Functional Glycomics; data not shown). Because none of the glycans displayed any significant binding to the IFT52 GIFT domain, we were unable to confirm sugar binding by IFT52 experimentally, and the function of the N-terminal part of IFT52 is yet to be established.

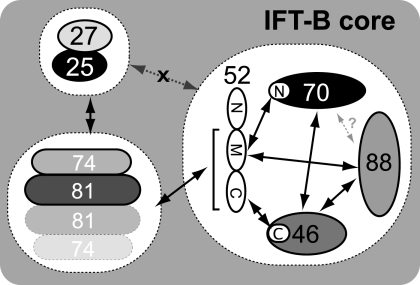

FIGURE 7.

Improved interaction map of the IFT-B core complex. IFT27/25 form a stable heterodimer that interacts directly with another subcomplex containing IFT81/74. IFT88/70/52/46 form a stable heterotetramer in which the central part of IFT52 (IFT52(281–381), M) binds to both IFT70 and IFT88, and the C-terminal part of IFT52 (IFT52(382–454), C) binds to IFT46. IFT52 also binds to the IFT81/74/27/25 tetramer thus providing a physical link between the IFT88/70/52/46 and IFT81/74/27/25 subcomplexes. Because the N-terminal 281 residues of IFT52 do not bind IFT81/74/27/25, the C-terminal half (M plus C) of IFT52 is shown to bind IFT81/74 in the figure. Other known but still unmapped interactions within the IFT88/70/52/46 tetramer are shown with black arrows, and a potential interaction between IFT88 and IFT70 is shown with a gray, dashed arrow. No direct interaction was observed between the IFT88/70/52/46 and IFT27/25 subcomplexes.

An understanding of the IFT mechanism at the molecular level will ultimately require high resolution structures of IFT complexes bound to cargo and motor proteins. However, given the large size and the large number of subunits of the IFT complex, reconstitution and purification of samples suitable for structural studies is a daunting task. In this study we presented a biochemical mapping of some of the interactions within the IFT-B core, which will hopefully pave the way for high resolution structural studies to unravel the molecular details of the IFT complex architecture.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Hongmin Qin for providing an IFT70-containing plasmid and Elisabeth Weyer from the Max Planck Institute Core Facility for analyzing proteins by mass spectrometry.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4.

- IFT

- intraflagellar transport

- CBP

- calmodulin-binding protein

- NTA

- nitrilotriacetic acid

- SEC

- size-exclusion chromatography

- TPR

- tetratricopeptide repeat.

REFERENCES

- 1. Goodenough U. W. (1989) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1, 58–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Emmer B. T., Maric D., Engman D. M. (2010) J. Cell Sci. 123, 529–536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Davis E. E., Brueckner M., Katsanis N. (2006) Dev. Cell 11, 9–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gerdes J. M., Davis E. E., Katsanis N. (2009) Cell 137, 32–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pozsgai E., Gomori E., Szigeti A., Boronkai A., Gallyas F., Jr., Sumegi B., Bellyei S. (2007) BMC Cancer 7, 233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baker K., Beales P. L. (2009) Am. J. Med. Genet. 151C, 281–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rosenbaum J. L., Witman G. B. (2002) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 3, 813–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kozminski K. G., Johnson K. A., Forscher P., Rosenbaum J. L. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 5519–5523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kozminski K. G., Beech P. L., Rosenbaum J. L. (1995) J. Cell Biol. 131, 1517–1527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cole D. G., Diener D. R., Himelblau A. L., Beech P. L., Fuster J. C., Rosenbaum J. L. (1998) J. Cell Biol. 141, 993–1008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Walther Z., Vashishtha M., Hall J. L. (1994) J. Cell Biol. 126, 175–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pazour G. J., Dickert B. L., Witman G. B. (1999) J. Cell Biol. 144, 473–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Porter M. E., Bower R., Knott J. A., Byrd P., Dentler W. (1999) Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 693–712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Perrone C. A., Tritschler D., Taulman P., Bower R., Yoder B. K., Porter M. E. (2003) Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 2041–2056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hou Y., Pazour G. J., Witman G. B. (2004) Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 4382–4394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Follit J. A., Tuft R. A., Fogarty K. E., Pazour G. J. (2006) Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 3781–3792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lechtreck K. F., Luro S., Awata J., Witman G. B. (2009) Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 66, 469–482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang Z., Fan Z. C., Williamson S. M., Qin H. (2009) PloS One 4, e5384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fan Z. C., Behal R. H., Geimer S., Wang Z., Williamson S. M., Zhang H., Cole D. G., Qin H. (2010) Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 2696–2706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Piperno G., Siuda E., Henderson S., Segil M., Vaananen H., Sassaroli M. (1998) J. Cell Biol. 143, 1591–1601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schafer J. C., Winkelbauer M. E., Williams C. L., Haycraft C. J., Desmond R. A., Yoder B. K. (2006) J. Cell Sci. 119, 4088–4100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cole D. G. (2003) Traffic 4, 435–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lucker B. F., Behal R. H., Qin H., Siron L. C., Taggart W. D., Rosenbaum J. L., Cole D. G. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 27688–27696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Deane J. A., Cole D. G., Seeley E. S., Diener D. R., Rosenbaum J. L. (2001) Curr. Biol. 11, 1586–1590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pazour G. J., Dickert B. L., Vucica Y., Seeley E. S., Rosenbaum J. L., Witman G. B., Cole D. G. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 151, 709–718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huangfu D., Liu A., Rakeman A. S., Murcia N. S., Niswander L., Anderson K. V. (2003) Nature 426, 83–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Murcia N. S., Richards W. G., Yoder B. K., Mucenski M. L., Dunlap J. R., Woychik R. P. (2000) Development 127, 2347–2355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lucker B. F., Miller M. S., Dziedzic S. A., Blackmarr P. T., Cole D. G. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 21508–21518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bhogaraju S., Taschner M., Morawetz M., Basquin C., Lorentzen E. (2011) EMBO J. 30, 1907–1918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fribourg S., Romier C., Werten S., Gangloff Y. G., Poterszman A., Moras D. (2001) J. Mol. Biol. 306, 363–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Karpenahalli M. R., Lupas A. N., Söding J. (2007) BMC Bioinformatics 8, 2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ward J. J., McGuffin L. J., Bryson K., Buxton B. F., Jones D. T. (2004) Bioinformatics 20, 2138–2139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Follit J. A., Xu F., Keady B. T., Pazour G. J. (2009) Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 66, 457–468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Behal R. H., Betleja E., Cole D. G. (2009) Methods Cell Biol. 93, 179–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lupas A., Van Dyke M., Stock J. (1991) Science 252, 1162–1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Piperno G., Mead K. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 4457–4462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Brazelton W. J., Amundsen C. D., Silflow C. D., Lefebvre P. A. (2001) Curr. Biol. 11, 1591–1594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Collet J., Spike C. A., Lundquist E. A., Shaw J. E., Herman R. K. (1998) Genetics 148, 187–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Perkins L. A., Hedgecock E. M., Thomson J. N., Culotti J. G. (1986) Dev. Biol. 117, 456–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Beatson S., Ponting C. P. (2004) Trends Biochem. Sci. 29, 396–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.