Abstract

Rac1 activity, polarity, lamellipodial dynamics, and directed motility are defective in keratinocytes exhibiting deficiency in β4 integrin or knockdown of the plakin protein Bullous Pemphigoid Antigen 1e (BPAG1e). The activity of Rac, formation of stable lamellipodia, and directed migration are restored in β4 integrin-deficient cells by inducing expression of a truncated form of β4 integrin, which lacks binding sites for BPAG1e and plectin. In these same cells, BPAG1e, the truncated β4 integrin, and type XVII collagen (Col XVII), a transmembrane BPAG1e-binding protein, but not plectin, colocalize along the substratum-attached surface. This finding suggested to us that Col XVII mediates the association of BPAG1e and α6β4 integrin containing the truncated β4 subunit and supports directed migration. To test these possibilities, we knocked down Col XVII expression in keratinocytes expressing both full-length and truncated β4 integrin proteins. Col XVII-knockdown keratinocytes exhibit a loss in BPAG1e-α6β4 integrin interaction, a reduction in lamellipodial stability, an impairment in directional motility, and a decrease in Rac1 activity. These defects are rescued by a mutant Col XVII protein truncated at its carboxyl terminus. In summary, our results suggest that in motile cells Col XVII recruits BPAG1e to α6β4 integrin and is necessary for activation of signaling pathways, motile behavior, and lamellipodial stability.

Keywords: Actin, Cell Migration, Cell Motility, Collagen, Integrin, Lamellipodia

Introduction

Re-epithelialization, the process by which epidermal cells undergo directed migration and move over an exposed wound bed, is a critical aspect in the closure of epithelial wounds. Factors that impact the ability of a cell to migrate can be roughly grouped into those involved in the basic mechanism of motility and those involved in the steering mechanism (1). To migrate efficiently, in a directed manner, cells must establish and maintain an asymmetric morphology with defined leading and trailing edges (2). This leading edge is characterized by a sheet-like extension termed a lamellipodium (1). Moreover, the rates of extension, the stability of the formed lamellipodium, and the size of the extension are the determining factors in defining the migration characteristics of a cell (3, 4). Indeed, the rate of lamellipodium extension correlates with migration rate, whereas lamellipodium stability (persistence) correlates with processivity or turning frequency (1).

Lamellipodium formation requires localized rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton, which involves signaling mediated by Rac1 (a small GTPase of the Rho family) to the actin severing protein cofilin (5). Through severing of actin filaments, cofilin increases the number of free actin barbed ends from which actin filaments extend while simultaneously increasing the depolymerization rate of older actin filaments, thereby increasing the local pool of free actin monomers (6). Spatial control of Rac1 and cofilin activity can therefore drive localized extension of the actin-rich lamellipodium. In addition to rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton, lamellipodium stability is also dependent upon adhesion to the underlying substratum, with cell to matrix adhesion being a prerequisite for generation of sufficient traction forces to drive forward cell motility (1, 7).

Keratinocytes in culture assemble two major matrix adhesion devices, hemidesmosomes (also known as stable adhesion complexes) and focal adhesions. Focal adhesions are understood to be dynamic attachment points with roles in cell spreading and motility (8). In contrast, hemidesmosomes have classically been likened to spot welds due to their appearance and apparent functionality (9). At the core of the hemidesmosome are two transmembrane components, the α6β4 integrin heterodimer and type XVII collagen (Col XVII),3 also known as bullous pemphigoid antigen 2 (BPAG2) or BP180 (10). Both of these components associate with the extracellular ligand laminin 332 (formerly laminin 5) (11–13). Intracellularly, the β4 integrin cytoplasmic tail contains binding sites for two plakin molecules, termed the bullous pemphigoid antigen 1e (BPAG1e) and plectin (14, 15). Col XVII also possesses a BPAG1e binding site (14, 15). Plectin and BPAG1e mediate the anchorage of the keratin intermediate filament cytoskeleton to the cell surface (9). Thus, the keratin cytoskeleton is linked to laminin 332 in the extracellular matrix through the hemidesmosome.

Although hemidesmosomes play an essential role in adhesion of the epidermal layers to the dermis of the skin, there is mounting evidence that their protein components are also involved in the regulation of directed motility (16–19). For example, following epidermal wounding, α6β4 integrin relocates from within hemidesmosomal structures to the leading front of the migrating epithelial cells where it regulates cell polarity and directed migration through activation of the small GTPase Rac1 and the actin-remodeling protein cofilin (16, 17, 20). These data are consistent with a number of other studies where it has been demonstrated that β4 integrin is involved in directed migration in response to an electric field and that α6β4 integrin supports migration of cancer cells in an actin-dependent fashion (16, 18, 19, 21). Moreover, our recent study presented evidence indicating that BPAG1e, one of the two bullous pemphigoid antigens that interact with α6β4 integrin, is also required for signaling to Rac and, hence, plays a role in directed skin cell migration (17). In contrast, the role of Col XVII, the second bullous pemphigoid antigen, in regulating cell migration is quite controversial with contradictory reports in the literature (11, 22).

In our current studies, we present evidence that, in cells expressing a truncated β4 integrin subunit that lacks binding sites for BPAG1e, Col XVII mediates the interaction of BPAG1e with α6β4 integrin. Furthermore, by knocking down Col XVII in keratinocytes expressing either full-length or truncated β4 integrin, we demonstrate that Col XVII is required for Rac activity, lamellipodial dynamics, and processive migration. Our findings provide novel insight into the mechanisms that determine keratinocyte motile behavior.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture, shRNA, Antibodies, and Other Reagents

Immortalized human epidermal keratinocytes (HEKs), β4 integrin-deficient keratinocytes derived from a patient with junctional epidermolysis bullosa with pyloric atresia (JEB cells), and JEB cells stably expressing either full-length (JEBβ4FL) or truncated β4 integrin (JEBβ4Trun) have been described previously (16, 23). BPAG1e-knockdown human keratinocytes were prepared as previously detailed (17). The cells were maintained in defined keratinocyte serum-free medium supplemented with a 1% penicillin/streptomycin mixture (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA) and grown at 37 °C. Col XVII-knockdown human keratinocytes were generated using MISSION shRNA lentiviruses (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 5 × 105 HEK, JEBβ4Fl, or JEBβ4Trun cells were seeded overnight in six-well dishes, then infected with lentivirus encoding Col XVII-specific shRNAs or scrambled shRNAs at a multiplicity of infection of 0.5 in culture medium supplemented with Polybrene (8 μg/ml). The following day, the medium of the infected cells was aspirated and replaced with fresh medium containing puromycin (0.5 μg/ml) for selection of stable transfectants. Col XVII knockdown was confirmed by SDS-PAGE/immunoblotting. In the case of the infected HEKs, multiple individual clones using shRNAs targeting different regions of the Col XVII message were isolated and expanded. Specifically, Cn1CXVIIkd and Cn3CXVIIkd were generated using NM_00049.2–5374s1c1 targeting the 3′UTR of COLXVIIA1, and Cn2CXVIIkd was generated with NM_000494.2-2992s1c1 targeting the coding sequence nucleotides 1216-1237.

Mouse monoclonal antibodies against β4 integrin (3E1) and α3 integrin (P1B5) were purchased from Chemicon International (Temecula, CA). Hybridoma cells producing 9E10, a mouse monoclonal against the Myc epitope, were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). Rabbit monoclonal antibodies against plectin and actin were obtained from Epitomics, Inc. (Burlingame, CA). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against lamin A/C and mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase were obtained from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). Antibodies against β4 integrin (CD104) were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). 5E, a human mAb against BPAG1e, was a gift from Dr. Takashi Hashimoto (Keio University, Tokyo, Japan) (24). A mouse monoclonal antibody against BPAG1e (10C5) was characterized previously (25). A mixture of mouse monoclonal antibodies (clones 7.1 and 13.1) against GFP was purchased from Roche Applied Science (Indianapolis, IN). The mouse IgM mAb preparation (1804b) and rabbit polyclonal antibody (J17) against the amino-terminal domain of Col XVII were described previously (26–28). Secondary antibodies conjugated with various fluorochromes or horseradish peroxidase were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc. (West Grove, PA).

The Rac1 inhibitor NSC23766 was obtained from the Drug Synthesis and Chemistry Branch, Developmental Therapeutics Program, Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, NCI, National Institutes of Health. It was added to keratinocyte growth medium at 50 μm 24 h prior to cell analysis.

Adenoviruses expressing Myc-tagged constitutively active forms of Rac1, RhoA, and cdc42 (CA Rac1, CA RhoA, and CA cdc42) were generously provided by Dr. James Bamburg (University of Colorado, Boulder, CO). RT-PCR-mediated amplification of Col XVII Nt1–517 and its cloning into pEGFP were described previously (15). The green fluorescent protein-tagged construct was subcloned into the polylinker of pENTR4 vector (Invitrogen Corp.), and the expression cassette was transferred into the pAD/CMV/V5-DEST vector using LR recombination according to the manufacturer's protocol. Constructs were verified by DNA sequencing. Following amplification, the adenoviral expression clone was introduced into 293A cells by Lipofectamine-mediated transfection. After 10–12 days, the crude viral lysate was harvested and used to amplify the adenovirus as previously described (16). The amplified viral stocks were titered, and keratinocytes were infected at a multiplicity of infection of 1:50 in cell medium. In all adenoviral studies, expression of the induced protein was confirmed by immunoblotting and immunofluorescence.

SDS-PAGE and Western Immunoblotting

Cell extracts were prepared as described previously (29, 30). Protein samples were processed for SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting as detailed elsewhere (29, 31). Western immunoblots were scanned and quantified using a MetaMorph Imaging System as we detailed elsewhere (Universal Imaging Corp., Molecular Devices, Downingtown, PA) (16).

Immunoprecipitation

JEBβ4FL, JEBβ4Trun, or HEKs expressing GFP were extracted in (0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1 mm EGTA, 1 mm EDTA, 150 mm NaCl in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5) containing a mixture of protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich). The cell extracts were clarified by centrifugation, and a 50% slurry of beads conjugated with either rat anti-GFP (Medical and Biological Laboratories Co, Nagoya, Japan) or rat IgG in lysis buffer was added to the supernatant. The bead/supernatant mixture was incubated for 2 h at 4 °C. The beads were washed, collected by centrifugation, and boiled in SDS-PAGE sample buffer prior to immunoblotting as above.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Cells on glass coverslips were processed as detailed elsewhere (16). All preparations were viewed with a confocal laser scanning microscope (UV LSM 510, Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY). Images were exported as TIFF files, and figures were prepared using Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator software. Colocalization was quantified by merging thresholded pseudocolored red and green images, isolating the yellow, green, and red pixels from the merged image. Pixel areas were quantified using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). Percentage pixel colocalization was determined by calculating the ratio of yellow (colocalized) pixel area to either yellow plus green pixel area or the yellow plus red pixel area as appropriate.

Observations of Live Cells, Motility Assays, and Kymography

Single cell motility was measured as detailed by us previously (16). Briefly, cells were plated onto uncoated 35-mm glass-bottomed culture dishes (MatTek Corp., Ashland, MA) 18–24 h prior to cell motility assays. Cells were viewed on a TE2000 inverted microscope (Nikon Inc., Melville, NY). Images were taken at 2-min intervals over 2 h, and cell motility behavior was analyzed by a MetaMorph Imaging System (Universal Imaging Corp., Molecular Devices, Downingtown, PA). For each cell line, means of total distance migrated (speed), maximum net displacement from the origin, and processivity (maximum distance from origin/total distance) were calculated. For kymography, cells were plated as above and images taken using a 60× objective every 5 s for 15 min. From the resultant stack of images a composite from each of the frames beneath a single pixel wide line in the direction of migration was constructed using MetaMorph software. Measurements of lamellipodia extension distance and persistence were measured from the resultant composite (3). For cells expressing GFP proteins, expression was determined prior to live cell imaging or confirmed retrospectively by fluorescence optics.

FRAP

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) studies were performed as described elsewhere (32, 33). Time-lapse observations were made using an LSM 510 confocal microscope (Zeiss Inc.) under the following conditions: 100×, 1.4 numerical aperture oil immersion objective, maximum power 25 milliwatts, tube current 5.1 A (31% laser power), and pinhole 1.33 airy units (optical slice, 1.0 μm). GFP images were acquired by excitation at 488 nm and emission at 515–545 nm. Cell regions were bleached at the plane of the membrane at 488 nm, 100% laser power using the minimum number of iterations to cause complete bleaching (20–40 iterations). Recovery was monitored at 31% laser power at 1-min intervals. For quantitative analyses, the fluorescence intensity of 1) the photobleached region, 2) the extracellular background intensity, and 3) intracellular brightest intensity were determined using Metamorph 4.0 (Universal Imaging) software. All data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel. Data were adjusted for sample fading as detailed elsewhere (32, 33).

Rac G-LISA

Quantitative analysis of Rac1 activation was performed using a G-LISA Rac activation assay (Cytoskeleton, Inc., Denver, CO) as described previously (34, 35). Briefly, cell lysates were prepared as per the manufacturer's protocol from subconfluent cultures, and protein concentrations were determined using Precision RedTM Advanced Protein Assay Reagent (Cytoskeleton). Samples at a concentration of 1 mg/ml in 96-well plate format were used for determination of Rac activity according to the manufacturer's instructions using an ELx808 ultramicroplate spectrophotometer (Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, Vermont). Data analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel. Where cells expressing GFP-tagged proteins were analyzed, cells were FACS-sorted based upon GFP signal on the day prior to analysis.

Statistical Analyses

Experiments were performed at minimum in triplicate, and results represent mean ± S.D. or S.E. as indicated. Analysis of variance and Student's t-tests were performed on data sets using Prism (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA), and differences between samples were deemed significant if p was <0.05.

RESULTS

β4 Integrin-deficient or BPAG1e-knockdown Keratinocytes Exhibit Reduced Lamellipodial Persistence and Extension Length

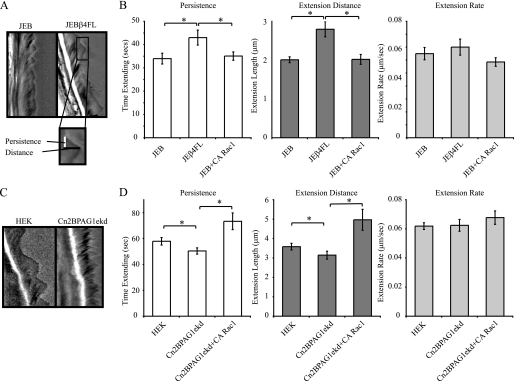

Our previous studies and those of others indicate that β4 integrin-deficient keratinocytes from patients with junctional epidermolysis bullosa (JEB) exhibit aberrant motility behavior and a loss of front-back polarity (16, 18). Moreover, we recently demonstrated that the β4 integrin-binding plakin molecule, BPAG1e, is required for polarized motility of keratinocytes via its ability to regulate activation of Rac1 and cofilin (17). Because it has been demonstrated that Rac1 and cofilin activities are reduced in JEB and BPAG1e-knockdown cells and that the action of these proteins is known to be involved in the generation of polarized lamellipodial protrusions in migrating cells, we tested the hypothesis that the polarization and motility defects in these cell lines are a reflection of aberrant lamellipodia extension and/or stability (16, 36). To do so, we first compared lamellipodial dynamics in JEB cells with those in JEBβ4FL cells, in which β4 integrin expression has been rescued through retroviral introduction of a GFP-tagged full-length β4 integrin construct, using a kymography approach (16). This approach involves rapid image acquisition (every 5 s) over a short time course and creating a montage of the pixels beneath a line drawn in the direction of migration (Fig. 1A) (3). From the generated kymographs, we have derived measurements for each protrusion event, i.e. time spent elongating (persistence, which equates to stability), and extension distance (Fig. 1B). The ratio of these values gives the rate of extension, which correlates approximately with migration speed (3). Our kymographic analyses indicate that both the persistence and the extension distance of lamellipodia generated by JEB cells are significantly less than that of JEBβ4FL cells, whereas there is no significant difference between the cell lines with regards to the rate of lamellipod extension (Fig. 1B). Likewise, the lamellipodial dynamics of two HEK lines exhibiting BPAG1e knockdown, Cn2BPAG1ekd and Cn12BPAG1ekd, displays a significant reduction in both lamellipodium persistence and extension distance but not extension rate, relative to HEKs or HEKs stably infected with a scrambled shRNA (Fig. 1: representative kymographs from one HEK cell and one Cn2BPAG1ekd cell (Fig. 1C); results for Cn12BPAG1e are shown in supplemental Fig. S1A) (17).

FIGURE 1.

Keratinocytes deficient in β4 integrin or exhibiting BPAG1e knockdown show reduced lamellipodial persistence and extension length. A, representative kymographs of JEB cells and JEB cells induced to express full-length β4 integrin (JEBFLβ4). Phase-contrast images of individual keratinocytes were acquired every 5 s over 15 min. Kymographs were generated as a montage of the images beneath a single pixel-wide line drawn in the direction of migration with time on the vertical axes. The inset displays the measurements taken for each protrusion event. In B, persistence, extension distance, and extension rate measurements of the lamellipodia of JEB, JEBFLβ4, and JEB cells infected with CA Rac1 are presented. C, representative kymographs of HEK and a BPAG1e-knockdown line (Cn2BPAG1ekd, exhibiting a 75% knockdown in BPAG1e expression). In D, persistence, extension distance, and extension rate measurements of the lamellipodia of HEKs, Cn2BPAG1ekd, and Cn2BPAG1ekd cells infected with CA Rac1 are presented graphically. Values in B and D are plotted as mean ± S.E. from >20 cells per treatment, >3 protrusion events per cell. *, significance of p < 0.01.

Lamellipodial persistence and extension distance were unaffected by infection of JEB cells with adenovirus encoding active (CA) Rac1, RhoA, or cdc42 (Fig. 1B, supplemental Fig. S1B). Expression and function of these virally expressed proteins was confirmed in HEKs (supplemental Fig. S1, C and D). In contrast to JEB cells, infection of Cn2BPAG1ekd or Cn12BPAG1ekd (not shown) with virus encoding CA Rac1 induced an increase in both persistence and distance values to levels above those of HEKs (Fig. 1D and supplemental Fig. S1A). A similar increase was not observed following infection with virus encoding CA RhoA or CA cdc42 (supplemental Fig. S1A). Conversely, inhibition of Rac1 activity in HEKs, through use of the Rac inhibitor NSC23766, led to a significant decrease in both lamellipodium persistence and distance values but not in extension rate (supplemental Fig. S1E).

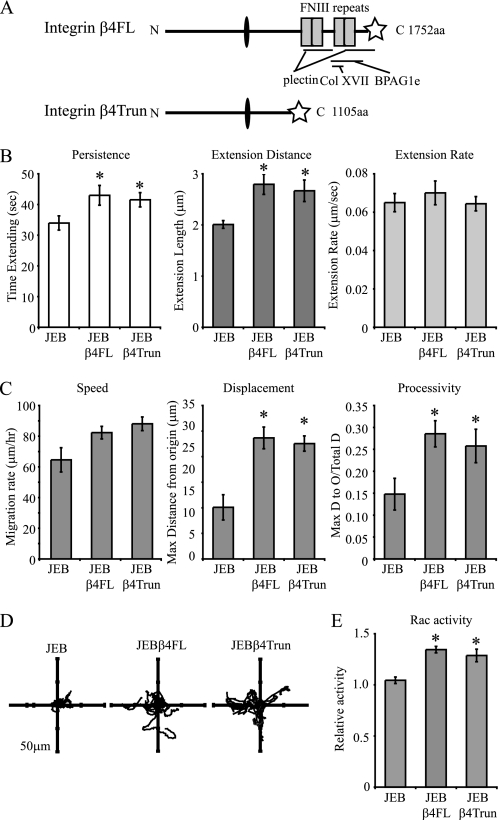

Expression of a Carboxyl-terminally Truncated β4 Integrin Is Sufficient to Rescue JEB Lamellipodia and Motility Defects

The above data indicate that both β4 integrin and BPAG1e were involved in the regulation of lamellipodial protrusion. This led us to test whether the direct binding of β4 integrin to BPAG1e is necessary for proper lamellipodia dynamics and keratinocyte motility. To do so, we analyzed previously described JEB cells expressing a β4 integrin mutant truncated at amino acid 1109 (JEBβ4Trun cells) (23). This truncation removes the β4 integrin binding sites for plectin, BPAG1e, and Col XVII (Fig. 2A) (14, 37, 38). Surprisingly, lamellipodia persistence and distance values in these JEBβ4Trun cells were rescued relative to JEB cells (Fig. 2B). We also analyzed the motility behavior of JEBβ4Trun cells in single cell motility assays. Whereas JEB cells moved in tight circles, never migrating far from their origin, JEBβ4Trun and JEBβ4FL cells exhibited significantly increased net displacement and processivity values (Fig. 2, C and D). Furthermore, Rac activity levels in the JEBβ4Trun cells were significantly higher than in the JEB cells and were similar to the activity levels in JEBβ4FL cells (Fig. 2E).

FIGURE 2.

A truncated β4 integrin rescues JEB lamellipodial dynamics. A, schematic depiction of full-length β4 integrin (β4FL) and a truncated protein (β4Trun), with a star denoting a carboxyl-terminal GFP tag in each. Binding sites for plectin, Col XVII, and BPAG1e are indicated. In B, lamellipodial persistence, extension distance, and extension rate values for the lamellipodia of JEB cells, JEB cells expressing either full-length β4 integrin (JEBβ4FL), or JEB cells expressing the carboxyl-terminally truncated β4 integrin (JEBβ4Trun) are shown graphically. Values are plotted as mean ± S.E. from >20 cells per treatment, >3 protrusion events per cell. In C, JEB, JEBβ4FL, or JEBβ4Trun cells were imaged every 2 min over 2 h, migration paths were tracked, and mean total migration/time (speed), maximum displacement from the origin, and processivity (net displacement/total displacement) were plotted from >20 cells per assay, at least three assays per line. In D representative vector diagrams of JEB, JEBβ4FL, or JEBβ4Trun cells are presented with each line representing the migration path of a single cell. In E, protein extracts of subconfluent JEB, JEBβ4FL, and JEBβ4Trun cells were normalized for total protein levels and relative Rac activity levels determined by G-LISA. The asterisk in B, C, and E denotes significance, p < 0.01, relative to JEBs.

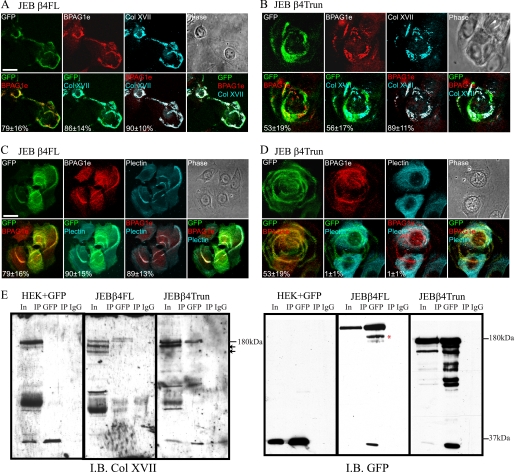

The above results reveal that a direct interaction between β4 integrin and BPAG1e is not required for regulation of keratinocyte lamellipodia dynamics and cell motility. This raises the question, where is BPAG1e in JEBβ4Trun cells? Thus, we processed both JEBβ4FL and the JEBβ4Trun cells for immunofluorescence microscopy using antibodies against BPAG1e. In both cell types, BPAG1e is found in association with clustered α6β4 integrin complexes along the substrate-binding surface of the cells (Fig. 3, A–D). However, quantification of pixel overlap revealed that the colocalization in JEBβ4Trun cells occurred at lower frequency than in the JEBβ4FL (53 ± 17% of GFP pixels colocalized with BPAG1e signal in JEBβ4Trun versus 79 ± 16% in JEBβ4FL). In contrast, staining with antibodies against plectin revealed that plectin only colocalized with full-length GFP-tagged β4 integrin and exhibited no association with the truncated β4 integrin (Fig. 3, C and D, 90 ± 15% JEBβ4FL versus 1 ± 1% JEBβ4Trun). This suggests that BPAG1e interaction with α6β4 integrin containing a truncated β4 subunit involves another molecule. The obvious candidate is Col XVII, because it can interact with both α6β4 integrin and BPAG1e (15, 39). A number of pieces of data support this possibility. First, although Col XVII colocalized with α6β4 integrin complexes in both JEBβ4FL and the JEBβ4Trun cells, the association in the later was incomplete (Fig. 3, A and B, 86 ± 14% versus 56 ± 17%). However, BPAG1e and Col XVII almost exactly colocalized (89 ± 12% in JEBβ4Trun). In other words, BPAG1e colocalization with JEBβ4Trun occurred predominantly at sites where Col XVII was also found. Secondly, Col XVII was present in immunoprecipitates of full-length and truncated β4 integrin generated from the JEBβ4FL and the JEBβ4Trun cells, confirming their interaction (Fig. 3E). The relatively inefficient co-precipitation of Col XVII with full-length β4 integrin compared with the truncated protein may reflect differences in solubility of β4 integrin/Col XVII complexes in the two different cell types.

FIGURE 3.

Truncated β4 integrin colocalizes and coprecipitates with Col XVII. JEBβ4FL (A and C) and JEBβ4Trun cells (B and D) were plated onto glass coverslips and, 48 h later, were fixed and imaged by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy following staining with antibodies against GFP (pseudocolored green) to visualize tagged β4 integrin protein, BPAG1e (pseudocolored red) and either Col XVII (A and B) or plectin (C and D) (pseudocolored cyan), as indicated. Overlays of green/red, green/cyan, and cyan/red images are shown in panels 5, 6, and 7 along with quantification of pixel colocalization (± S.D.) from >50 cells per overlay. Overlay of the three colors is shown in panel 8. Bars, 20 μm. In E, GFP and GFP-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated from keratinocytes infected with GFP, JEBβ4FL, and JEBβ4Trun keratinocytes as indicated. Input lysates (In) and immunoprecipitates derived using anti-GFP- or IgG-conjugated beads (IP GFP and IP IgG, respectively) were immunoblotted (IB) with antibodies against Col XVII and GFP as indicated. Molecular mass standards are shown at right of blots. The red asterisks indicate a previously reported degradation product of the β4FL construct. We speculate that the lower molecular weight species in the Col XVII antibody blot (small arrows) represent Col XVII proteolytic products.

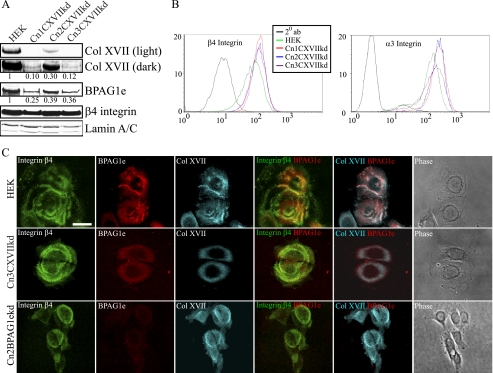

Lentiviral-mediated shRNA Knockdown of Col XVII in Epidermal Keratinocytes

Because our previous work and the results mentioned above have suggested that BPAG1e and α6β4 integrin are required for activation of Rac, development of cell polarity, lamellipodial stabilization, and directed migration, we wondered whether Col XVII might also play a role in these phenomena (16, 17). Because there are conflicting reports in the literature on this issue, to resolve these contradictions, we used lentivirus to deliver two different Col XVII shRNA to HEKs (11, 22). We generated three clonal cell populations displaying efficient Col XVII knockdown. Specifically, clone Cn1CXVIIkd displayed 10%, Cn2CXVIIkd 30%, and Cn3CXVIIkd 12% of parental HEK Col XVII expression levels (Fig. 4A). Col XVII knockdown also resulted in a decrease in BPAG1e but not β4 integrin expression, as assessed by immunoblotting (Fig. 4A). Moreover, Col XVII knockdown did not impact surface expression of β4 and α3 integrin as determined by FACS (Fig. 4B). Loss of BPAG1e expression was also observed in Col XVII-knockdown cells prepared for immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig. 4C). In contrast, Col XVII localization with α6β4 integrin was unaffected by BPAG1e knockdown (Fig. 4C, 76 ± 10% Col XVII/β4 integrin pixel overlap in Cn2BPAG1eshRNA versus 87 ± 6% in HEKs).

FIGURE 4.

Col XVII knockdown leads to mislocalization of BPAG1e. HEKs were infected with a lentivirus encoding shRNA targeting Col XVII and clonal lines established through antibiotic resistance selection. In A, lysates from control HEKs and three stable clones (Cn1CXVIIkd, Cn2CXVIIkd, and Cn3CXVIIkd) were prepared for immunoblotting and probed with antibodies against Col XVII, BPAG1e, β4 integrin, and lamin A/C as indicated. The expression of Col XVII and BPAG1e relative to that in HEKs was calculated following densitometric scanning of the blots and is indicated underneath each lane. In B, cell surface expression of β4 integrin and α3 integrin was compared between HEKs and Col XVII shRNA clones by FACS as indicated (black tracing; secondary antibody alone). In C, HEKs, Cn3CXVIIkd (Col XVII-knockdown cells), and Cn2BPAG1ekd (BPAG1e-knockdown cells) were plated onto glass coverslips and, 48 h later, were fixed and then imaged by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy following staining with antibodies against β4 integrin (pseudocolored in green), BPAG1e (pseudocolored in red), and Col XVII (pseudocolored in cyan), as indicated. Green and red images are shown overlaid in the fourth column with colocalization appearing yellow. Red and cyan images are shown overlaid in the fifth column with colocalization appearing white. Phase-contrast images of the fixed and stained cells are shown in the column at the right. Bar, 20 μm.

Col XVII Knockdown Keratinocytes Display Impaired Lamellipodia Dynamics, Loss of Directed Migration, and Reduced Rac Activity Levels

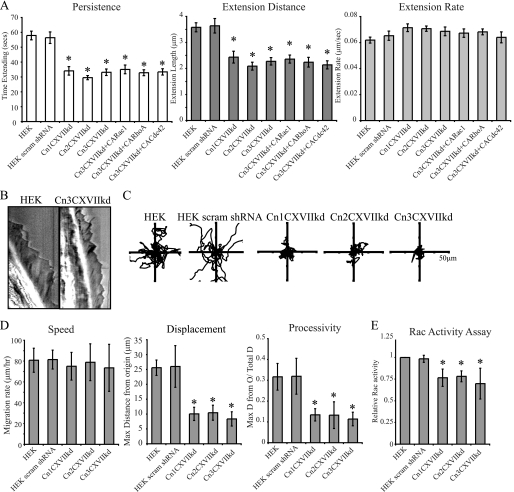

There was a significant reduction in lamellipodia persistence and extension distance in Col XVII-knockdown keratinocytes compared with HEKs and HEKs expressing a scrambled shRNA (values graphed in Fig. 5A; representative kymographs of HEK and Cn3CXVIIkd cells are shown in Fig. 5B). The rate of lamellipodial extension was slightly increased relative to controls, although this increase was below significance (Fig. 5A). Intriguingly, the observed reductions in lamellipodia persistence and extension distances in all three lines exhibiting Col XVII knockdown were more pronounced than those seen in BPAG1e-knockdown cells (compare Figs. 1 and 5).

FIGURE 5.

Col XVII-knockdown keratinocytes show reduced lamellipodia persistence and extension length. In A, persistence, extension distance, and extension rate measurements of the lamellipodia of HEKs, scrambled shRNA-infected HEKs (HEK scram shRNA), three Col XVII-knockdown cell lines (Cn1CXVIIkd, Cn2CXVIIkd, and Cn3CXVIIkd), and Cn3CXVIIkd cells infected with CA Rac1, CA RhoA, or CA cdc42 are depicted. Values are plotted as mean ± S.E. from >20 cells per treatment, >3 protrusion events per cell. B, representative kymographs of a HEK and a Cn3CXVIIkd (Col XVII-knockdown) cell. In C and D, cells were imaged every 2 min over 2 h, and the migration paths of single cells were tracked. In C, representative vector diagrams of HEKs, scrambled shRNA-infected HEKs, and Col XVII-knockdown clones are presented. In D, total distance migrated/time (speed), maximum net displacement, and net displacement/total displacement (processivity) are presented from >20 cells per assay, at least 3 assays per cell line. In C, protein lysates from subconfluent HEKs, scrambled shRNA-infected HEKs, and Col XVII-knockdown cells were normalized to total protein levels, and relative Rac activity was determined by G-LISA. The graph represents relative mean ± S.D. from three independent assays. The asterisks in A, D, and E denote significance, p < 0.01, relative to HEKs.

We also assessed the ability of Col XVII-knockdown keratinocytes to migrate in a directed fashion in a single cell motility assay (Fig. 5, C and D). Consistent with our lamellipodia dynamics data, knockdown cells displayed significant reductions in their net displacement and processivity values relative to controls (Fig. 5D). Also consistent with these findings, the Col XVII-knockdown cells displayed significantly reduced Rac activity (Fig. 5E). However, in contrast to the BPAG1e-knockdown cells, adenoviral-induced expression of CA Rac1 failed to rescue the lamellipodia dynamics of Col XVII-knockdown clones (Fig. 5A).

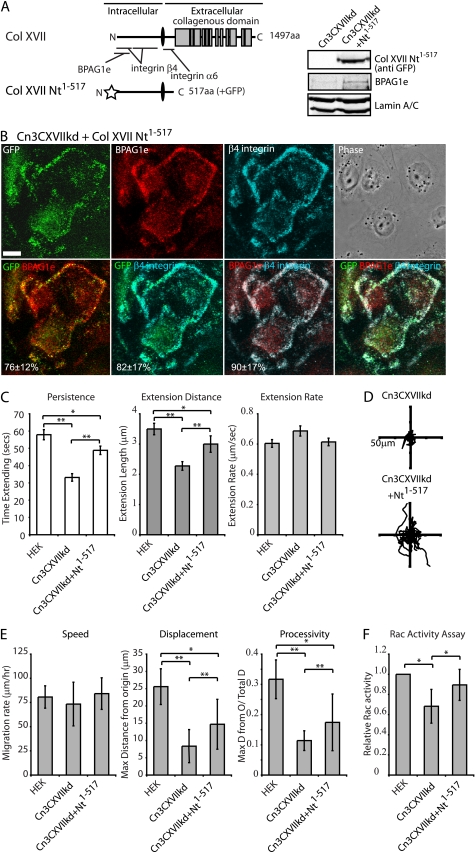

Expression of the Amino-terminal Region of Col XVII in Col XVII-knockdown Keratinocytes Rescues Lamellipod Dynamics and Motile Behavior

To ensure that the results we obtained with our cloned Col XVII-knockdown cell lines are not due to off-target effects, we undertook rescue experiments. For these studies we infected the Col XVII knockdown cells with adenovirus encoding a fragment of Col XVII, consisting of its cytoplasmic, transmembrane, and extracellular juxtamembrane domains (Col XVII Nt1–517, Fig. 6A). This fragment lacks the laminin binding motifs of the intact Col XVII molecule (11). Expression of the fragment in Col XVII-knockdown cells was confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 6A). BPAG1e expression was increased in infected cells (Fig. 6A). Moreover, in Col XVII-knockdown cells infected with virus encoding Col XVII Nt1–517, the tagged Col XVII fragment colocalized with BPAG1e and β4 integrin, consistent with previous observations (15) (Fig. 6B, 76 ± 12% GFP/BPAG1e pixel overlap, 82 ± 17% GFP/β4 integrin overlap). The Col XVII-knockdown keratinocytes expressing Col XVII Nt1–517 show significantly higher rates of lamellipodial persistence and extension distance relative to uninfected controls, although the rescued values are still below that of wild-type HEKs (Fig. 6C). Moreover, the Col XVII Nt1–517-expressing Cn3CXVIIkd cells displayed significantly increased net displacement and persistence values in single cell motility assays, and their Rac activity levels were restored to near wild-type levels (Fig. 6, D–F).

FIGURE 6.

Expression of a Col XVII fragment rescues the motility defects of Col XVII-knockdown keratinocytes. Diagrammatic representations of Col XVII and the Col XVII fragment (Col XVII Nt1–517), comprising the Col XVII cytoplasmic, transmembrane, and juxtamembrane domains, used in these studies are shown in A. Binding sites for α6 integrin, β4 integrin, and BPAG1e are marked. Cn2CXVIIkd cells were adenovirally infected to induce expression of the GFP-tagged Col XVII Nt1–517. Total protein lysates from uninfected and Col XVII Nt1–517-infected Cn3CXVIIkd cells were immunoblotted with antibodies against GFP, BPAG1e, and lamin A/C. In B, 2 days following infection, cells were plated overnight onto glass coverslips, fixed, and processed for indirect immunofluorescence microscopy for GFP (pseudocolored green), and with antibodies against BPAG1e (pseudocolored red), and β4 integrin (pseudocolored cyan). Red/green, green/cyan, and red/cyan images are shown overlaid in panels 4–6. Percentage colocalization of the GFP signal with BPAG1e or β4 integrin staining is indicated in panels 5 and 6. Percentage colocalization of BPAG1e staining with β4 integrin is indicated in panel 7. Values presented as mean ± S.D. from three experiments, >20 cells/experiment. Bar in B, 20 μm. In C, persistence, extension distance, and extension rate measurements of the lamellipodia of HEKs, Cn3CXVIIkd cells, and Cn3CXVIIkd cells expressing Col XVII Nt1–517 were determined by kymography. Values plotted in C are the mean ± S.E. from >15 cells per treatment, >3 protrusion events per cell. In D and E, the motility of the indicated cells was tracked over 2 h with images being taken every 2 min. In D, the migration paths of at least 10 individual cells are plotted relative to their start position (origin) in each vector diagram. In E, total distance migrated/time (speed), maximum net displacement, and net displacement/total migration (processivity) are plotted from >20 cells per assay at least three assays per cell line. In F, protein lysates of subconfluent HEKs, Cn3CXVIIkd cells, and Cn3CXVIIkd cells expressing Col XVII were normalized to total protein levels, and relative Rac activity determined by GLISA. The graph represents relative mean ± S.D. from three independent assays. The asterisks in C, E, and F denote significance; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

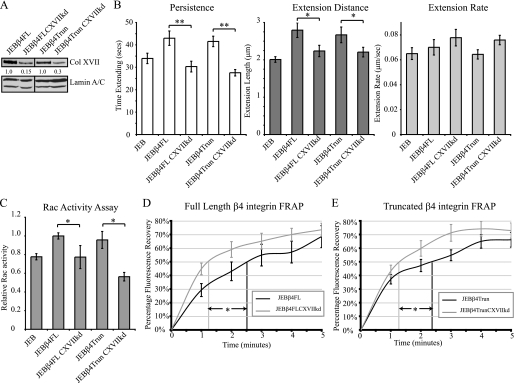

β4 Integrin Displays Enhanced Dynamics in Col XVII-knockdown Keratinocytes

The dynamics of α6β4 integrin in the plane of the membrane in BPAG1e-knockdown cells is inhibited (17). To assess whether loss of Col XVII also impacts α6β4 integrin dynamics, we used the same lentiviral shRNA delivery strategy as above to stably knockdown Col XVII expression in JEBβ4FL and JEBβ4Trun lines (Fig. 7A). Knockdown lines exhibited 15% to 30% of the level of Col XVII expression of their respective parental cells (Fig. 7A). We next confirmed that knockdown in these cells results in the same lamellipodial defects that we detail above in HEKs. Kymographic analyses of lamellipod dynamics in both knockdown lines revealed reductions in lamellipod persistence and extension distance, but with no significant difference in extension rate in both Col XVII-knockdown lines (Fig. 7B). Rac activity levels were also reduced in both Col XVII-knockdown lines relative to their respective parental lines (Fig. 7C). To analyze the impact of Col XVII knockdown upon the motility of GFP-tagged full-length and truncated β4 integrin in the plane of the membrane the rate of FRAP was determined. Time to 50% recovery of pre-bleach fluorescence intensity level, internally normalized to sample fading, was significantly faster in JEBβ4FL cells exhibiting Col XVII knockdown than their parental JEBβ4FL cells (73 ± 21 s in JEBβ4FL ColXVIIshRNA versus 152 ± 39 s in JEBβ4FL, p < 0.05, Fig. 7D). Similarly, fluorescence recovery rates were significantly faster in Col XVII-knockdown JEBβ4Trun cells than their JEBβ4Trun parents (77 ± 16 versus 136 ± 44 s, respectively, p < 0.05, Fig. 7E). These defects were not observed in JEBβ4FL or JEBβ4Trun cells infected with scrambled shRNA (supplemental Fig. S2).

FIGURE 7.

Col XVII-knockdown keratinocytes display enhanced β4 integrin dynamics. In A, immunoblots of total protein extracts of JEBβ4FL and JEBβ4Trun as well as JEBβ4FL and JEBβ4Trun cells stably infected with shRNA targeting Col XVII probed with antibodies against Col XVII and Lamin A/C are shown. Expression of Col XVII relative to parental lines is shown beneath each lane. In B, persistence, extension distance, and extension rate measurements of the lamellipodia of JEB, JEBβ4FL, JEBβ4Trun along with JEBβ4FL and JEBβ4Trun exhibiting Col XVII knockdown are presented. Values are plotted as mean ± S.E. from >20 cells per treatment, >3 protrusion events per cell. In C, protein lysates from the indicated lines were normalized to total protein levels and relative Rac activity determined by G-LISA. The graph represents relative mean ± S.D. from three independent assays. Bracketed asterisks denote significant differences between columns; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01. D and E depict rates of FRAP of GFP-tagged full-length β4 integrin (D) or truncated β4 integrin (E) in JEB cells (black lines) or JEB cells exhibiting Col XVII knockdown (gray lines). Lines represent mean ± S.E. of >10 cells per cell line. Vertical lines indicate time to 50% recovery; * denotes significance, p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

In these studies, we have demonstrated that the absence of any one of the components of the complex comprising α6β4 integrin, BPAG1e, and Col XVII inhibits Rac activity, reduces the dynamics of lamellipodia, and perturbs directed motile behavior of keratinocytes. The notion that any of these proteins are determinants of cell motility has been controversial. They are all essential components of the hemidesmosome, which functions as a stable anchor in the intact skin by tethering keratinocytes to the dermis (9). Thus, it would appear contrary to suggest that they regulate key aspects of cell migration. Indeed, some have argued that they only indirectly modulate motility, their loss being a prerequisite to the development of a motile phenotype (40). However, it is becoming increasingly clear that hemidesmosome proteins are multifunctional, playing a role in stable adhesion and actively participating in migration. For example, we and others have demonstrated that α6β4 integrin is directly involved in regulating signals that control motile phenomena (16, 18, 19, 21, 41). Moreover, the up-regulation of α6β4 integrin, BPAG1e, and Col XVII in aggressive tumor cells, their presence in lamellipodia in cultured cells, and the observation that they are found in the leading edge of cells populating wounds point to a more direct role in migration (17, 20, 42–45).

A focus of the current study was to assess the role of Col XVII in migration and compare the motility phenotype of keratinocytes in which we have induced a knockdown in Col XVII expression with those of BPAG1e- and β4 integrin-deficient cells. Our data reveal that Col XVII-knockdown cells exhibit the same motility and lamellipodial defects as the latter cells, although the mechanism is subtly different. In this regard, the role of Col XVII in migration is somewhat controversial. For example, evidence has been presented that the extracellular domain of Col XVII that is proteolytically shed impairs keratinocytes ability to close scratch wounds (46). Conversely, the shed ectodomain of Col XVII has been demonstrated to promote squamous cell carcinoma cell transmigration (49, 53). Moreover, one group has shown that GABEB cells lacking apparent Col XVII expression demonstrate a migratory phenotype, whereas another has provided data indicating that Col XVII knockdown inhibits migration via reduced signaling to p38 MAPK (11, 22). Our data are consistent with the latter report because they indicate that Col XVII loss induces motility and signaling defects in keratinocytes. Intriguingly, our data also provide key insight into the mechanism via which Col XVII might regulate signaling to p38 MAPK. It likely does so by mediating both the localization and activation of Rac, a critical regulator of the p38 MAPK pathway (47).

Knockdown of Col XVII in keratinocytes also results in decreased BPAG1e expression. Moreover, the immunochemical and localization data we present led us to suggest that a primary function of Col XVII in motile keratinocyte is to mediate the interaction of BPAG1e with α6β4 integrin. Evidence for this comes from our Col XVII-knockdown cells, where we observed little or no BPAG1e association with α6β4 integrin complexes. This is consistent with a previous study indicating lack of BPAG1e/β4 integrin interaction in a GABEB cell line, which is deficient in Col XVII (14). Together these data indicate that the β4 integrin binding site for BPAG1e is insufficient for the recruitment of BPAG1e to the α6β4 integrin complex. In addition, in the current study, we also provide evidence that BPAG1e associates with α6β4 integrin containing a truncated β4 integrin lacking the BPAG1e binding domain. Most likely this association is mediated by Col XVII. Intriguingly, the same truncated β4 integrin also does not possess a Col XVII binding site. We assume that the Col XVII associates with the α6 subunit of α6β4 integrin under these circumstances, because α6 integrin can bind Col XVII directly (10, 26). Alternatively, Col XVII may associate with α6β4 integrin containing the truncated β4 subunit by binding to their common ligand (laminin-332) in the extracellular matrix (11, 12, 48). We are currently attempting to resolve this issue.

One further interesting aspect of this study is that activation of Rac1 rescued lamellipodial dynamics in BPAG1e-knockdown keratinocytes. This is consistent with our previous study indicating that motility defects of BPAG1e-knockdown cells are also rescued by activating Rac1 (17). In contrast, activation of Rac1 in β4 integrin- or Col XVII-knockdown cells fails to rescue their motility defects or lamellipodial dynamics (16). These results suggest the possibility that both β4 integrin and Col XVII have additional regulatory/structural functions in determining motility behavior in addition to their roles in transduction of signals, via BPAG1e, to the Rac1 pathway. We have suggested previously that one additional role for β4 integrin is related to matrix binding and/or deposition of laminin-332 into tracks (16). We base this on the finding that expression of a mutant form of β4 integrin (K150A), which is incapable of binding to its extracellular ligand laminin-332, restores Rac1 activity in JEB cells but is incapable of rescuing their motility defect (16, 50). In contrast, a matrix binding-deficient Col XVII fragment is capable of a partial rescue of the lamellipodial stability of Col XVII-knockdown cells. Indeed, our FRAP data indicate that Col XVII influences α6β4 integrin dynamics in the plane of the membrane. We observed enhanced β4 integrin motility in Col XVII-knockdown cells. This is the opposite consequence of BPAG1e deficiency, which results in an inhibition of β4 integrin mobility as determined by FRAP (17). One potential explanation for this apparently conflicting result is that knockdown of Col XVII removes a structural impediment to β4 integrin movement in the plane of the membrane. Based on our previously reported observation that β4 integrin dynamics are enhanced in cells in which the actin cytoskeleton has been disrupted, we suggest that Col XVII is involved in tethering α6β4 integrin containing complexes to the actin cytoskeleton (33, 48). In this scenario, Col XVII knockdown would remove this actin mediated “brake” upon β4 integrin dynamics. There is indirect evidence to support this, because Col XVII is known to bind the actin-linker proteins actinin-1 and -4 and hence can mediate integrin-actin cytoskeleton connection (51). In this regard, we should also point out that in a prior publication we speculated that plectin regulates α6β4 integrin dynamics by linking α6β4 integrin interaction to the actin cytoskeleton (16). However, we can now rule out this possibility, because α6β4 integrins containing a truncated β4 lacking a plectin binding site exhibit normal dynamics. This result is consistent with other studies indicating that plectin loss does not inhibit keratinocyte migration (52).

In summary, we have provided new insight into the mechanisms that regulate skin cell motility, an essential component of re-epithelialization in epidermal wound closure and invasion of epidermal tumor cells. Surprisingly these mechanisms involve the active participation of proteins previously deemed to play roles exclusively in stabilizing cell-matrix adhesion sites in keratinocytes. Here, we have provided evidence that Col XVII, by mediating the association of BPAG1e and α6β4 integrin, is an important regulator of the keratinocyte lamellipodium, the key organelle that generates the force necessary for directional protrusion at the cell periphery (49, 53). Thus, our results now provide a critical new understanding of the consequences of up-regulation of Col XVII, α6β4 integrin, and BPAG1e in aggressive tumors and the presence of these proteins at the leading front of migrating tumor and epidermal cells covering wounds (17, 20, 42–45). They are clearly key players in the regulation of motility. Moreover, although our studies have focused on skin cells, Col XVII, like α6β4 integrin and BPAG1e, is also expressed in a variety of epithelia, including those of the breast, bladder, and lung (9). Thus, our data have potential relevance to the mechanisms that underlie the motility of more than just skin cells and implicate Col XVII in the regulation of migration of diverse epithelial cell types during wound healing and tumorigenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the faculty and staff of the Cell Imaging and Flow Cytometry core facilities at Northwestern University for their technical support and expertise.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 AR054184 (to J. C. R. J.). This work was also supported by a Dermatology Foundation research grant (to K. J. H.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

- Col XVII

- collagen XVII

- BPAG1e

- bullous pemphigoid antigen 1e

- BPAG2

- bullous pemphigoid antigen 2

- CA

- constitutively active

- GABEB

- generalized atrophic benign epidermolysis bullosa

- JEB

- junctional epidermolysis bullosa

- HEK

- human epidermal keratinocyte

- FRAP

- fluorescence recovery after photobleaching

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Petrie R. J., Doyle A. D., Yamada K. M. (2009) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 538–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lauffenburger D. A., Horwitz A. F. (1996) Cell. 84, 359–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hinz B., Alt W., Johnen C., Herzog V., Kaiser H. W. (1999) Exp. Cell Res. 251, 234–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chodniewicz D., Klemke R. L. (2004) Exp. Cell Res. 301, 31–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yang N., Higuchi O., Ohashi K., Nagata K., Wada A., Kangawa K., Nishida E., Mizuno K. (1998) Nature. 393, 809–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pollard T. D., Borisy G. G. (2003) Cell. 112, 453–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kaverina I., Krylyshkina O., Small J. V. (2002) Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 34, 746–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wozniak M. A., Modzelewska K., Kwong L., Keely P. J. (2004) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1692, 103–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jones J. C., Hopkinson S. B., Goldfinger L. E. (1998) BioEssays. 20, 488–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hopkinson S. B., Findlay K., Jones J. C. (1998) J. Invest. Derm. 111, 1015–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tasanen K., Tunggal L., Chometon G., Bruckner-Tuderman L., Aumailley M. (2004) Am. J. Pathol. 164, 2027–2038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Niessen C. M., Hogervorst F., Jaspars L. H., de Melker A. A., Delwel G. O., Hulsman E. H., Kuikman I., Sonnenberg A. (1994) Exp. Cell Res. 211, 360–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rousselle P., Lunstrum G. P., Keene D. R., Burgeson R. E. (1991) J. Cell Biol. 114, 567–576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Koster J., Geerts D., Favre B., Borradori L., Sonnenberg A. (2003) J. Cell Sci. 116, 387–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hopkinson S. B., Jones J. C. (2000) Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 277–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sehgal B. U., DeBiase P. J., Matzno S., Chew T. L., Claiborne J. N., Hopkinson S. B., Russell A., Marinkovich M. P., Jones J. C. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 35487–35498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hamill K. J., Hopkinson S. B., DeBiase P., Jones J. C. (2009) Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 2954–2962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pullar C. E., Baier B. S., Kariya Y., Russell A. J., Horst B. A., Marinkovich M. P., Isseroff R. R. (2006) Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 4925–4935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rabinovitz I., Mercurio A. M. (1997) J. Cell Biol. 139, 1873–1884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lotz M. M., Rabinovitz I., Mercurio A. M. (2000) Am. J. Pathol. 156, 985–996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mercurio A. M., Rabinovitz I., Shaw L. M. (2001) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13, 541–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Qiao H., Shibaki A., Long H. A., Wang G., Li Q., Nishie W., Abe R., Akiyama M., Shimizu H., McMillan J. R. (2009) J. Invest. Dermatol. 129, 2288–2295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Werner M. E., Chen F., Moyano J. V., Yehiely F., Jones J. C., Cryns V. L. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 5560–5569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hashimoto T., Amagai M., Ebihara T., Gamou S., Shimizu N., Tsubata T., Hasegawa A., Miki K., Nishikawa T. (1993) J. Invest. Dermatol. 100, 310–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Klatte D. H., Jones J. C. (1994) J. Invest Dermatol. 102, 39–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hopkinson S. B., Baker S. E., Jones J. C. R. (1995) J. Cell Biol. 130, 117–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gonzales M., Haan K., Baker S. E., Fitchmun M. I., Todorov I., Weitzman S., Jones J. C. R. (1999) Mol. Bio. Cell. 10, 259–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goldfinger L. E., Stack M. S., Jones J. C. (1998) J. Cell Biol. 141, 255–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Riddelle K. S., Green K. J., Jones J. C. (1991) J. Cell Biol. 112, 159–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Langhofer M., Hopkinson S. B., Jones J. C. (1993) J. Cell Sci. 105, 753–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Harlow E., Lane D. (1988) Antibodies: A Laboratory Manual, CSHL Press, Woodbury, NY [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tsuruta D., Gonzales M., Hopkinson S. B., Otey C., Khuon S., Goldman R. D., Jones J. C. (2002) Faseb J. 16, 866–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tsuruta D., Hopkinson S. B., Jones J. C. (2003) Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 54, 122–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhou X., Tian F., Sandzén J., Cao R., Flaberg E., Szekely L., Cao Y., Ohlsson C., Bergo M. O., Boren J., Akyürek L. M. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 3919–3924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schlegel N., Burger S., Golenhofen N., Walter U., Drenckhahn D., Waschke J. (2008) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 294, C178–C188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dawe H. R., Minamide L. S., Bamburg J. R., Cramer L. P. (2003) Curr. Biol. 13, 252–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Niessen C. M., Hulsman E. H., Oomen L. C., Kuikman I., Sonnenberg A. (1997) J. Cell Sci. 110, 1705–1716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schaapveld R. Q., Borradori L., Geerts D., van Leusden M. R., Kuikman I., Nievers M. G., Niessen C. M., Steenbergen R. D., Snijders P. J., Sonnenberg A. (1998) J. Cell Biol. 142, 271–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jonkman M. F., Pas H. H., Nijenhuis M., Kloosterhuis G., Steege G. (2002) J. Invest. Dermatol. 119, 1275–1281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Litjens S. H., de Pereda J. M., Sonnenberg A. (2006) Trends Cell Biol. 16, 376–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Russell A. J., Fincher E. F., Millman L., Smith R., Vela V., Waterman E. A., Dey C. N., Guide S., Weaver V. M., Marinkovich M. P. (2003) J. Cell Sci. 116, 3543–3556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gipson I. K., Spurr-Michaud S., Tisdale A., Elwell J., Stepp M. A. (1993) Exp. Cell Res. 207, 86–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Herold-Mende C., Kartenbeck J., Tomakidi P., Bosch F. X. (2001) Cell Tissue Res. 306, 399–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Parikka M., Nissinen L., Kainulainen T., Bruckner-Tuderman L., Salo T., Heino J., Tasanen K. (2006) Exp. Cell Res. 312, 1431–1438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Parikka M., Kainulainen T., Tasanen K., Väänänen A., Bruckner-Tuderman L., Salo T. (2003) J. Histochem. Cytochem. 51, 921–929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Franzke C. W., Tasanen K., Schäcke H., Zhou Z., Tryggvason K., Mauch C., Zigrino P., Sunnarborg S., Lee D. C., Fahrenholz F., Bruckner-Tuderman L. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 5026–5035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mainiero F., Soriani A., Strippoli R., Jacobelli J., Gismondi A., Piccoli M., Frati L., Santoni A. (2000) Immunity 12, 7–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tsuruta D., Hopkinson S. B., Lane K. D., Werner M. E., Cryns V. L., Jones J. C. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 38707–38714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pollard T. D. (2007) Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 36, 451–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hamill K. J., Kligys K., Hopkinson S. B., Jones J. C. (2009) J. Cell Sci. 122, 4409–4417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gonzalez A. M., Otey C., Edlund M., Jones J. C. (2001) J. Cell Sci. 114, 4197–4206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Osmanagic-Myers S., Gregor M., Walko G., Burgstaller G., Reipert S., Wiche G. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 174, 557–568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Small J. V., Stradal T., Vignal E., Rottner K. (2002) Trends Cell Biol. 12, 112–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.