Abstract

Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor (CDKN1A), often referred to as p21Waf1/Cip1 (p21), is induced by a variety of environmental stresses. Transcription factor ELK-1 is a member of the ETS oncogene superfamily. Here, we show that ELK-1 directly trans-activates the p21 gene, independently of p53 and EGR-1, in sodium arsenite (NaASO2)-exposed HaCaT cells. Promoter deletion analysis and site-directed mutagenesis identified the presence of an ELK-1-binding core motif between −190 and −170 bp of the p21 promoter that confers inducibility by NaASO2. Chromatin immunoprecipitation and electrophoretic mobility shift analyses confirmed the specific binding of ELK-1 to its putative binding sequence within the p21 promoter. In addition, NaASO2-induced p21 promoter activity was enhanced by exogenous expression of ELK-1 and reduced by expression of siRNA targeted to ELK-1 mRNA. The importance of ELK-1 in response to NaASO2 was further confirmed by the observation that stable expression of ELK-1 siRNA in HaCaT cells resulted in the attenuation of NaASO2-induced p21 expression. Although ELK-1 was activated by ERK, JNK, and p38 MAPK in response to NaASO2, ELK-1-mediated activation of the p21 promoter was largely dependent on ERK. In addition, EGR-1 induced by ELK-1 seemed to be involved in NaASO2-induced expression of BAX. This supports the view that the ERK/ELK-1 cascade is involved in p53-independent induction of p21 and BAX gene expression.

Keywords: Cell Cycle, Cell Death, ETS Family Transcription Factor, Transcription Promoter, Transcription Target Genes, BAX, EGR-1, ELK-1, p21/Waf1/Cip1, Sodium Arsenite

Introduction

Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (CDKN1A), also known as p21, WAF1, or CIP1, plays important roles in p53-dependent cell cycle arrest in response to DNA damage (1). In addition to cell cycle inhibition, it has also been implicated in various other cellular responses, including transcriptional regulation, nuclear import, cell motility, apoptosis, DNA repair, and aging (in cellular context- and extracellular signal-dependent manners) (2, 3). Aberrant up-regulation of p21 is strongly associated with cell cycle arrest, which may occur at multiple stages during the cell cycle (4–6) and which is mediated through inhibition of the activity of cyclin E-CDK2 or -CDK4 complexes (7) or cyclin B-CDK1 (5, 8–10) or through the degradation of cyclin B1 (11). Although p21 was initially identified as a p53 target gene, a variety of other transcription factors, including STATs, E1AF, AP-2, C/EBP, ETS-1, p150 (Sal2), Spalt, SP1, sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP)-1a, and hepatocyte nuclear factor (HNF)-4α, bind to specific cis-acting elements in the p21 promoter in response to different extracellular signals and regulate p21 expression independently of p53 (12).

Inorganic arsenic predominantly occurs in the form of either arsenite (trivalent arsenic) or arsenate (pentavalent arsenic), the two of which may be interconverted in vivo. Arsenic produces various toxic effects, including carcinogenesis, neurotoxicity, and immunotoxicity (13). A growing body of evidence suggests that chronic exposure to low levels of arsenic may be linked to the modulation of intracellular signaling pathways and gene expression profiles responsible for cell cycle progression, resulting in promotion of cell transformation (14–16). Interestingly, cell transformation occurs only in cells exposed to low concentrations of arsenite (i.e. <5 μm), whereas higher concentrations (i.e. ≥50 μm) lead to apoptosis and cytotoxicity (17–19). Arsenic is a well known carcinogen in humans but has also been shown to be an effective chemotherapeutic agent (depending on cell type, arsenic species and dose, and duration of exposure) (19). Sodium arsenite (NaASO2) inhibits cell cycle progression in NIH3T3 cells (20), human umbilical vein endothelial cells (21), and rat neuroepithelial cells (22) as well as in certain types of cancer cell, including SiHa cervical carcinoma (23) and A431 epidermoid carcinoma (24) cells, in all cases by up-regulating p21 expression. However, it is unclear how arsenite regulates p21 expression.

Mammals have at least five major MAPK subfamilies, of which the best known are the ERK, JNK, and p38 kinase. These major kinases play important roles in transmitting extracellular signals to cells and modulate the expression of multiple genes (25–27). Moreover, deregulation of MAPKs is associated with the pathogenesis of several human diseases (28). In general, JNK and p38 kinase are activated by growth-inhibitory signals and cellular stress, whereas ERK responds to mitogenic and cell survival signals. However, the roles of individual MAPK signaling pathways are complex. Although many studies support a role for ERK signaling in cell proliferation and survival, it has also been implicated in the transduction of antiproliferative signals in certain circumstances. For example, ERK contributes to the induction of neuronal differentiation by nerve growth factor (29) and to growth arrest and the induction of apoptosis through phosphoactivation of p53 (30, 31). Elsewhere, several studies have demonstrated that ERK signaling is associated with up-regulation of p21 expression in a variety of cell types (32–38). However, despite the emerging recognition that MAPKs inhibit cell proliferation by affecting p21 expression, little is yet known about the mechanisms by which these kinases regulate p21 transcription.

ELK-1, a member of the ETS subfamily of transcription factors, is a well known substrate of ERK, JNK, and p38 kinase (39–42). It regulates the transcription of immediate early response genes, including c-FOS and EGR-1, through serum response elements within their promoters (39–43). Sodium arsenite (NaASO2) induces the transcription of RTP801/REDD1/Dig2, a stress response gene, in HaCaT cells by activating ELK-1 (44), suggesting that ELK-1 may contribute to the responses of HaCaT cells to NaASO2. Because MAPK signaling induces p21 expression in a p53-independent fashion to negatively regulate cell cycle progression and ELK-1 is a known substrate of three major MAPKs, it is possible that MAPK-mediated activation of ELK-1 may contribute to NaASO2-induced p21 expression. However, the functional role of ELK-1 in trans-activation of the p21 gene has not been studied. We investigated the potential role of MAPK/ELK-1 signaling in the p53-independent regulation of p21 transcription using NaASO2-exposed human HaCaT keratinocytes carrying mutations in both p53 alleles (45).

Here, we identified cis-acting ELK-1 response elements in the human p21 gene promoter and assessed whether ELK-1 regulates transcription of the p21 gene in HaCaT keratinocytes. We found that ELK-1 directly trans-activates the p21 gene promoter independently of p53 and EGR-1 in NaASO2-exposed HaCaT cells. Furthermore, we showed that the induction of EGR-1 expression by ELK-1 contributes to NaASO2-induced BAX expression. Based on these data, we propose an additional role of ELK-1 in mediating NaASO2-induced p21 and BAX expression in p53-mutated HaCaT cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Reagents

HaCaT cells were obtained from the Cell Lines Service (Eppelheim, Germany). Wild-type (p53+/+) and p53-deficient (p53−/−) HCT116 human colon cancer cells (46) were kindly provided by Dr. Do Youn Jun (School of Life Science, Kyungpook National University, Korea). Cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone, Logan, UT). Sodium (meta)arsenite (NaAsO2) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Antibodies specific for phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr-202/Tyr-204), phospho-JNK1/2 (Thr-183/Tyr-185), and phospho-p38 MAP kinase (Thr-180/Tyr-182) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Antibodies raised against EGR-1, GAPDH, and ERK2 were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). The Dual-Glo® luciferase assay system for firefly and Renilla luciferase activities was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI).

Plasmid DNAs

A luciferase reporter plasmid carrying 2.4 kb of the human p21 promoter (pGL-2.4) was obtained from Dr. Jae-Yong Lee (Department of Biochemistry, College of Medicine, Hallym University, Korea). A full-length EGR-1 promoter reporter plasmid, pEgr1-Luc(−780/+1), was provided by Dr. H. Eibel (Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Research Laboratory University of Tubingen Medical Center, Germany) and is described elsewhere (47). A pRL-null plasmid carrying a Renilla luciferase reporter was purchased from Promega. An ELK-1 trans-activator plasmid, pFA2-Elk1(307–427), and its reporter plasmid, pFR-Luc, were purchased from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). A p53 cis-acting reporter (13×p53-Luc) was obtained from Addgene (Cambridge, MA). An ELK-1 expression plasmid (pCMV/flagElk-1) was a kind gift from Dr. Andrew Sharrocks (Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Manchester, UK). Dominant negative (DN)3-MEK1 (pCGN1/DN-MEK1), DN-ERK2 (pHA-ERK2 K52R), DN-JNK1 (pSRα/HA-JNK T183A/Y185F), and kinase-dead (KD)-p38 kinase (pCDNA3/flag-p38 T180A/Y182F) plasmids were donated by Dr. Do-Sik Min (Department of Molecular Biology, College of Natural Science, Pusan National University, Korea). The pT&A cloning vector was obtained from Real Biotech Corp. (Taipei, Taiwan).

Cell Proliferation Assay

HaCaT cells were seeded onto 96-well plates (2 × 103 cells/well) and then treated with increasing concentrations of NaASO2 for various periods of time. Proliferation rates were determined by using Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cell Cycle Analysis

Cellular DNA content was analyzed by flow cytometry as described previously (48). Briefly, HaCaT cells were harvested after exposure to increasing concentrations of NaASO2 for 24 h, fixed in 70% ethanol, washed twice with PBS, and stained with a 50 μg/ml propidium iodide solution containing 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.1 mm EDTA, and 50 μg/ml RNase A. Fluorescence was measured and analyzed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Western Blot Analysis

Cells were lysed in a buffer containing 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.2), 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 150 mm NaCl, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, and 1 mm PMSF. The resulting protein samples (20 μg each) were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose filters. The blots were then incubated with the appropriate primary antibodies. Signals were developed using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (GE Healthcare).

Northern Blot Analysis

For each sample, 10 μg of total RNA were electrophoresed on a formaldehyde/agarose gel and transferred to a Hybond N+ nylon membrane (Amersham Biosciences). Northern blotting was performed with a [α-32P]dCTP-labeled p21 or EGR-1 cDNA probe, followed by hybridization with a GAPDH cDNA probe as described previously (48).

Transient Transfection and Promoter Reporter Assays

HaCaT cells were seeded onto 12-well plates and then transfected with the p21 or BAX promoter construct (0.2 μg), using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. To monitor transfection efficiency, pRL-null plasmid (50 ng), which carries a Renilla luciferase reporter, was included in all samples. Where indicated, mammalian expression vectors were also included. Then, 48 h post-transfection, cells were starved in medium containing 0.5% serum for 12 h and treated with NaASO2. After 6–12 h, firefly and Renilla luciferase activities in each sample were sequentially measured using the Dual-Glo® luciferase assay system. Luciferase activity in untreated cells was arbitrarily given a value of 1 (after normalization to the Renilla luciferase signal). Luminescence was measured using a Centro LB960 luminometer (Berthold Technologies, Bad Wildbad, Germany).

cis- and trans-Activation Assays

cis- and trans-activation by transcription factors was measured using the luciferase reporter assay system. To measure p53-dependent transcriptional activity, HaCaT cells were transfected with 0.2 μg of cis-acting reporter plasmid (13×p53-Luc) containing 13 tandem p53-binding sites. To measure trans-activation by ELK-1, HaCaT cells were transfected with 50 ng of trans-activator plasmid (pFA2/Gal4 DBD-Elk1), which encodes a fusion protein comprising the DNA-binding domain of yeast Gal4 (amino acid residues 1–147) and the activation domain of ELK-1 (amino acid residues 307–427), along with 0.5 μg of luciferase reporter plasmid (pFR/5×Gal4-Luc) containing five Gal4 binding elements upstream of a luciferase gene. pRL-null plasmid (50 ng) was included in all samples to allow transfection efficiency to be monitored. Following transfection, cells were treated with or without NaASO2 and assayed for firefly and Renilla luciferase activities, using the Dual-Glo® luciferase assay system.

Site-directed Mutagenesis within the Promoters

Generation of serial deletion constructs of the p21 promoter is described elsewhere (49). Disruption of the ELK-1 core binding sequence in the p21 promoter by mutagenesis was performed by replacing a cytosine base with a guanine (TTCC → TTGG), as described previously (50). The primers used to generate point mutations in the ELK-1 core motif were as follows: forward, 5′-tgcagcacgcgaggttGGgggaccggctggcct-3′; reverse, 5′-aggccagccggtcccCCaacctcgcgtgctgca-3′ (−296/−264; capital letters represent mutated bases). The resulting construct was named p21-Luc(−235/+39mtElk1). A series of deletion constructs of BAX promoter fragments were synthesized by PCR. The primer sequences were 5′-gcggtagctcatgcctgtaa-3′ (forward, −478/−458), 5′-ggcctctgagcttttgcact-3′ (forward, −297/−278), and 5′-gtgagagccccgctgaac-3′ (common reverse, −14/+4). The PCR products were ligated into the pT&A vector, followed by ligation into the pGL3-basic vector using KpnI and BglII sites. The resulting constructs were named pBax-Luc(−478/+4) and pBax-Luc(−297/+4). The primers used to generate point mutations in the EGR-1 core motif were as follows: forward, 5′-cacaagttagagacaagcctTTTcgtgggctatattgctagatc-3′; reverse, 5′-gatctagcaatatagcccacgAAAaggcttgtctctaacttgtg-3′ (−465/−372; capital letters are mutated bases). The resulting construct was named pBax-Luc(−478/+4mtEgr1). The specific identities of all plasmid constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

EMSA was performed using nuclear extracts (10 μg) prepared from untreated HaCaT cells and cells treated with 50 μm NaASO2 and 32P-labeled oligonucleotide probes, as described previously (51). The sequences of the oligonucleotide probes and competitors for the ELK-1-binding site (−190/−170) used were 5′-cacgcgaggTTCCgggaccgg-3′ (ELK-1 wild-type) and 5′-cacgcgaggTTGGgggaccgg-3′ (ELK-1 mutant). Samples were separated on non-denaturing 6% polyacrylamide gels and visualized by autoradiography.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay

HaCaT cells were treated with 50 μm NaASO2 for 15 min. The cross-linking of protein to DNA and chromatin immunoprecipitation were performed as described previously (52). The following promoter-specific primers were used to PCR-amplify p21 gene promoter sequences: 5′-gaaatgtgtccagcgcacca-3′ (target region forward primer, −255/−236), 5′-ggctcctggctgcccagcgc-3′ (target region reverse primer, −133/−114), 5′-gtcaggaacatgtcccaacat-3′ (off-target region forward primer, −2235/−2215), 5′-gctgggatctgatgcatgtgt-3′ (off-target region reverse primer, −2046/−2026).

Expression of siRNA

Short hairpin RNA (shRNA) plasmids expressing ELK-1 siRNA or scrambled control siRNA were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. HaCaT cells were transfected with shRNA plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) or a Nucleofector device (AMAXA Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) for transient and stable expression of ELK-1 siRNA, respectively. Two days after transfection, stable transfectants were selected using G418 (400 μg/ml). Knockdown of ELK-1 protein expression was verified by Western blot analysis. Generation of an expression plasmid carrying an siRNA targeted to EGR-1 mRNA (pSilencer/siEgr-1) is described elsewhere (48).

Statistical Analysis

Each experiment was repeated at least three times. Data are presented as the mean ± S.D. Statistical comparisons were performed using Student's t test. A p value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The Growth of HaCaT Cells Is Inhibited by Exposure to NaASO2

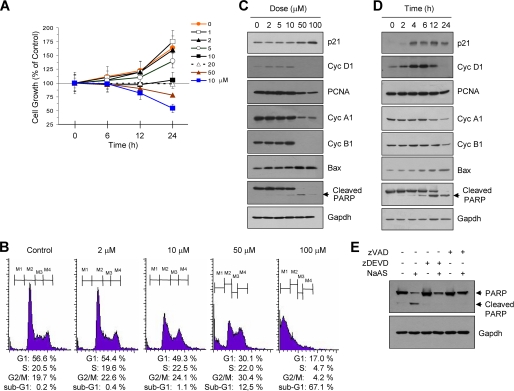

Exponentially growing HaCaT cells were treated with various concentrations of NaASO2 for different periods of time, and the cell proliferation rate was measured. The rate of growth of HaCaT cells was markedly reduced by NaASO2 treatment in a concentration- and time-dependent manner (Fig. 1A). A significant decrease in cell proliferation was observed in cells treated for 24 h with high concentrations of NaASO2 (≥50 μm). Next, we analyzed cell cycle profiles in cells treated with NaASO2 for 24 h (Fig. 1B). NaASO2 treatment caused a slight but significant dose-dependent decrease in the G1 population, which was accompanied by the accumulation of G2/M phase cells. Numbers of sub-G1 cells, typically associated with apoptosis, also increased dose-dependently. Somewhat higher rates of cell death were observed in cells treated with 100 μm NaASO2. Thus, treatment with NaASO2 modulated cell cycle progression and apoptotic cell death in HaCaT cells in a dose-dependent manner.

FIGURE 1.

Cellular response of HaCaT cells to NaASO2 treatment. A, HaCaT cells were seeded onto 96-well culture plates and treated with various concentrations of NaASO2 for the indicated periods of time. The cellular proliferation rate was measured using Cell Counting Kit-8. Data represent the mean ± S.D. (error bars) of one experiment performed in triplicate. Similar results were obtained from two other independent experiments. B, HaCaT cells were treated with different concentrations of NaASO2 for 24 h. Cells were harvested, fixed with ethanol, and stained with propidium iodide. Their DNA content was analyzed by flow cytometry. The percentages of the cell population in each of the following cell cycle phases were calculated: sub-G1 (M1), G1 (M2), S (M3), and G2/M (M4). C and D, HaCaT cells were cultured in the presence or absence of different concentrations of NaASO2 (C) or 50 μm NaASO2 for different periods of time (D). Cells were harvested and analyzed by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. Gapdh was used as an internal control for protein loading. E, HaCaT cells were treated with 50 μm NaASO2 for 24 h in the absence or presence of 20 μm benzyloxycarbonyl-DEVD-fluoromethyl ketone (zDEVD) or 20 μm benzyloxycarbonyl-VAD-fluoromethyl ketone (zVAD) as indicated, and whole cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting using antibodies against PARP. Gapdh antibody was used as an internal control for protein loading.

p21 and BAX Are Up-regulated in NaASO2-exposed HaCaT Cells

Aberrant expression of p21 is associated with growth inhibition and the induction of apoptosis in many cell types. To investigate whether NaASO2 alters the expression of p21, HaCaT cells were treated with different concentrations of NaASO2, and levels of p21 protein were measured. As shown in Fig. 1C, levels of p21 increased in cells treated with NaASO2 at concentrations of ≥50 μm. In contrast, levels of cyclin D1 in cells treated with low (≤10 μm) and high (≥50 μm) concentrations of NaASO2 increased and decreased compared with basal levels, respectively. Levels of other cell cycle-regulatory proteins, including PCNA, cyclin A1, and cyclin B1, decreased in cells treated with high doses (≥50 μm) of NaASO2. We further observed that NaASO2 induced remarkable increases in the levels of BAX and cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), two representative markers of apoptosis, in a dose-dependent manner. When HaCaT cells were exposed to 50 μm NaASO2 for different periods of time (Fig. 1D), p21 levels increased as early as 4 h and remained elevated 24 h later. In contrast, cyclin D1 protein levels increased transiently but declined below basal levels 24 h later. Levels of cyclin A1 and cyclin B1 decreased slightly after 24 h, whereas the expression levels of BAX and cleaved PARP were detected within 6 h and thereafter gradually increased.

The cleavage of native 113-kDa PARP, yielding 89- and 24-kDa fragments could be catalyzed in a caspase-dependent or -independent pathway (53). Because NaASO2 induces the cleavage of caspase-2 and caspase-7 in HaCaT cells (supplemental Fig. 1A), we next examined the effect of caspase inhibitors on the cleavage of PARP. NaASO2-induced PARP cleavage is prevented by pretreatment with benzyloxycarbonyl-VAD-fluoromethyl ketone, a pancaspase inhibitor, or benzyloxycarbonyl-DEVD-fluoromethyl ketone, a caspase-3/-7 inhibitor (Fig. 1E). Thus, it seems likely that exposure of HaCaT cells to high doses of NaASO2 (≥50 μm) inhibits cell cycle progression and promotes cell death via a caspase-dependent pathway. These data suggest that NaASO2 causes cell death by up-regulating the expression of proapoptotic proteins.

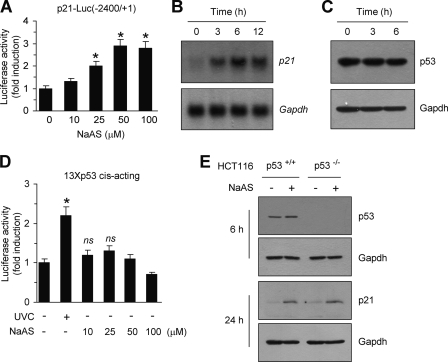

p53 Is Not Involved in NaASO2-induced Expression of p21

To determine whether NaASO2 activates the transcription of the p21 gene, HaCaT cells were transiently transfected with a full-length p21 promoter reporter (p21-Luc(−2400/+1)), and the effects of NaASO2 on luciferase reporter activity were assessed. NaASO2 dose-dependently increased luciferase reporter activity (Fig. 2A). An ∼2.9-fold increase in reporter activity was observed in cells treated with 50 μm NaASO2 (p < 0.01 versus mock-treated control). We confirmed the time-dependent induction of p21 mRNA expression by NaASO2 using Northern blot analysis (Fig. 2B). To identify mechanisms responsible for NaASO2-induced p21 expression, we first investigated the role of p53. Expression of p53 protein (Fig. 2C) and p53-dependent transcriptional activity (Fig. 2D) were not significantly altered in HaCaT cells exposed to NaASO2. Furthermore, NaASO2 induced p21 protein expression in p53-null HCT116 cells (Fig. 2E). Thus, p53 does not appear to be necessary for NaASO2 to induce p21 expression.

FIGURE 2.

p53 is not involved in NaASO2-induced p21 expression. A, HaCaT cells were transfected with 0.2 μg of p21-Luc(−2400/+1). After 48 h, cells were either left untreated or treated with increasing concentrations of NaASO2 for 8 h. Their luciferase activities were then measured. Data represent the mean ± S.D. (error bars) of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate (*, p < 0.01 versus untreated cells). B, HaCaT cells were treated with 50 μm NaAsO2 for the indicated periods of time. Total RNA was extracted and assessed for p21 mRNA expression by Northern blot analysis. Equal loading was verified by subsequently hybridizing the blot with a cDNA probe for Gapdh. C, HaCaT cells were treated with 50 μm NaAsO2 for the indicated periods of time. Levels of p53 protein in whole cell lysates (15 μg/lane) were measured by Western blotting using a mouse anti-p53 (DO-1) antibody. Gapdh was used as an internal control. D, HaCaT cells were transfected with 13×p53-Luc cis-acting reporter plasmid (0.5 μg). After 48 h, cells were either left untreated or treated with increasing concentrations of NaASO2 for 8 h. Their luciferase activities were then measured. Irradiation with UVC (40 J/m2) was used as a positive control for p53 activation. Data represent the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate (*, p < 0.01 versus untreated cells; ns, not significant). E, HCT116 cells, containing wild-type (p53+/+) or p53 null (p53−/−), were treated with 50 μm NaASO2 for 6 h (p53) or 24 h (p21). Whole cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. Gapdh was used as an internal control for protein loading.

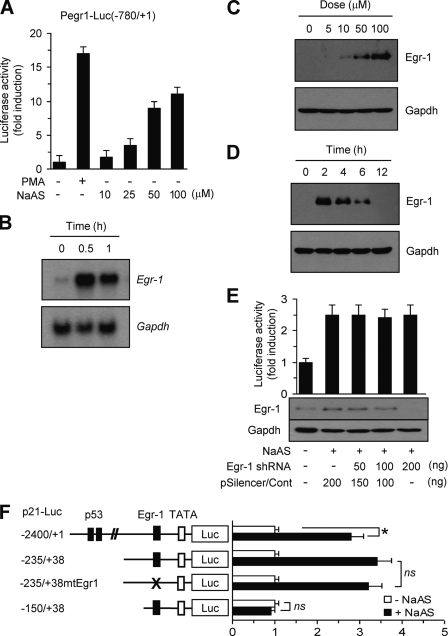

EGR-1 Is Not Involved in NaASO2-induced p21 Expression

It has been reported that arsenite induces EGR-1 expression in HaCaT cells (54). However, the consequences of this response are unknown. We confirmed that exposing HaCaT cells to NaASO2 activates the EGR-1 promoter (Fig. 3A). We also confirmed time-dependent induction of EGR-1 mRNA by NaASO2 using Northern blot analysis (Fig. 3B). Treatment with NaASO2 also causes EGR-1 protein to accumulate in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3C). The level of EGR-1 protein reached a peaked within 2 h after adding NaASO2, which gradually declined to basal levels by 12 h of stimulation (Fig. 3D). We and others have shown that EGR-1 binds directly to the proximal p21 promoter and activates p21 gene transcription (48, 49, 55). We used an RNA interference approach to investigate whether EGR-1 is involved in NaASO2-induced p21 promoter activation. HaCaT cells were transfected with an shRNA plasmid targeting specific sequence of the EGR-1 mRNA (pSilencer/siEgr-1), along with a full-length p21 promoter reporter (p21-Luc(−2400/+1)). Transient transfection of EGR-1 shRNA clearly attenuated NaASO2-induced EGR-1 expression; however, it had no effect on NaASO2-induced p21 promoter activity (Fig. 3E). Furthermore, when a series of deletion mutants of the p21 promoter-driven reporter were transfected into HaCaT cells, we found that luciferase activity remained high unless the region −235 to −150 was deleted (Fig. 3F). Given that a putative EGR-1 binding sequence is present in the region −150 to +38 of the p21 promoter (48–49, 55), we suggest that EGR-1 may not be essential for NaASO2-induced p21 promoter activation. To further assess the involvement of EGR-1, we made point mutations in the EGR-1-binding site (gggg to tttt); these mutations had no effect on NaASO2-induced luciferase reporter activity (Fig. 3F). Thus, it seems likely that a NaASO2 response element is present somewhere in the region between −235 and −150 of the p21 promoter.

FIGURE 3.

EGR-1 is not involved in NaASO2-induced p21 expression. A, HaCaT cells were transfected with 0.2 μg of the full-length EGR-1 promoter construct Pegr1-Luc(−780/+1) and 50 ng of pRL-null vector. After 48 h, cells were treated with different concentrations of NaASO2 (10, 25, 50, and 100 μm) for 8 h. Their luciferase activities were then measured. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; 20 nm) was used as a positive control for EGR-1 promoter activation. Data represent the mean ± S.D. (error bars) of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. B, HaCaT cells were treated with 50 μm NaAsO2 for the indicated periods of time. Total RNA was extracted and assessed for EGR-1 mRNA expression by Northern blot analysis. Equal loading was verified by subsequently hybridizing the blot with a cDNA probe for Gapdh. C and D, HaCaT cells starved in medium containing 0.5% serum for 24 h were cultured in the presence or absence of different concentrations of NaASO2 (C) or 50 μm NaASO2 for different periods of time (D). Cells were harvested and analyzed by Western blotting using anti-EGR-1 antibody. Gapdh was used as an internal control. E, HaCaT cells were transfected with 0.2 μg of p21-Luc(−2400/+1), along with different concentrations of scrambled (pSilencer/Cont) or EGR-1 shRNA plasmid (pSilencer/siEgr-1), as indicated. Knockdown of EGR-1 expression by transient transfection of EGR-1 shRNA was verified by Western blot analysis (bottom panels). F, HaCaT cells were co-transfected with 0.2 μg of p21 promoter construct (p21-Luc(−2400/+1), p21-Luc(−235/+38), p21-Luc(−235/+38)mtEgr1, or p21-Luc(−150/+38)), as indicated. Then, 48 h post-transfection, cells were treated with 50 μm NaASO2 for 8 h, and their luciferase activities were measured. Data represent the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate (*, p < 0.01 versus untreated cells; ns, not significant).

An ELK-1-binding Element in the p21 Promoter Is Necessary for NaASO2-induced p21 Promoter Activation

We next sought to identify the cis-acting element in the p21 gene responsible for NaASO2-induced activation. Putative transcription factor-binding sites were analyzed using the Web-based program MatInspector (Genomatix). We identified a consensus ETS-like protein-1 (ELK-1) core binding motif (TTCC; reverse complement of the commonly reported GGAA motif) between nucleotides −190 and −170 of the p21 promoter (Fig. 4A). To evaluate the role of this putative ELK-1-binding element, we introduced site-directed mutations (TTCC → TTGG) into the core ELK-1-binding motif of the p21-Luc(−235/+38) plasmid, yielding p21-Luc(−235/+38)mtElk1. The results of a promoter activity assay revealed that disruption of this core element significantly reduced NaASO2-induced promoter activity (Fig. 4B). This suggests that the putative reverse ELK-1-binding element located in the region −235 to −150 is necessary for transcriptional activation of the p21 promoter in response to NaASO2.

FIGURE 4.

Identification of an ELK-1-binding site within the p21 promoter. A, nucleotide sequence of the human p21 gene promoter region flanking the putative ELK-1 binding motif (−235 to −151). The core ELK-1-binding motif is enclosed in a box. B, HaCaT cells were transiently transfected with 0.2 μg of WT p21-Luc(−235/+38) construct or a derivative carrying a mutation in the ELK-1-binding site (mtElk1). Mutated nucleotides are highlighted by a box. Then, 48 h after transfection, cells were either left untreated or treated with 50 μm NaASO2 for 8 h and analyzed for luciferase activity. Data represent the mean ± S.D. (error bars) of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate (*, p < 0.01). C, nuclear extracts from HaCaT cells treated with 50 μm NaASO2 for 15 min were probed with 32P-labeled oligonucleotides with sequences corresponding to the region of the p21 promoter containing the ELK-1-binding site (−235 to −151 bp) in wild type or mutant (mtElk-1). To compete out labeled probes, unlabeled wild-type oligonucleotide (Competitor) was added in 10- and 100-fold excess. Arrow, DNA-ELK-1 complexes; arrowheads, nonspecific bindings. D, HeLa cells treated with NaASO2 for 15 min were cross-linked, lysed, and immunoprecipitated with anti-phospho-ELK-1 (Ser-383) antibody or normal rabbit IgG (negative control). Precipitated DNA was analyzed by standard PCR using primers specific for the target region (−255 to −114) or off-target region (−2235 to −2026). One aliquot of input DNA was used as a positive control.

ELK-1 Directly Binds to the p21 Promoter

To determine whether ELK-1 binds to the p21 promoter, an EMSA was performed. Nuclear extracts from HaCaT cells were incubated with the radiolabeled oligonucleotides whose sequences corresponded to the ELK-1-binding sequence found between nucleotides −190 and −170 of the p21 promoter. As shown in Fig. 4C, oligonucleotides containing this ELK-1-binding motif formed protein-DNA complexes, which were competed out by the addition of unlabeled oligonucleotide probe. The specificity of ELK-1 binding was confirmed by the failure of a radiolabeled probe carrying a mutation in the ELK-1-binding site core sequence (TTCC → TTGG) to form protein-DNA complexes. To verify the binding of ELK-1 to the p21 promoter at the chromatin level, we cross-linked DNA and bound proteins in NaASO2-treated HaCaT cells using formaldehyde. Cross-linked DNA-protein complexes were subjected to chromatin immunoprecipitation using a rabbit anti-phospho-ELK-1 antibody or normal rabbit IgG. The resulting immunoprecipitated DNA was amplified by PCR using primers designed to the promoter region (−255 to −89) of the p21 gene. Input genomic DNA was used as a positive control. As shown in Fig. 4D, a noticeable increase in the amount of protein-bound DNA in NaASO2-treated cells was detected using the anti-phospho-ELK-1 antibody but not normal rabbit IgG. The off-target region (−2235 to −2026) was not amplified, although positive results were obtained from input genomic DNA. These data indicate that ELK-1 physically interacts with the p21 promoter in vivo.

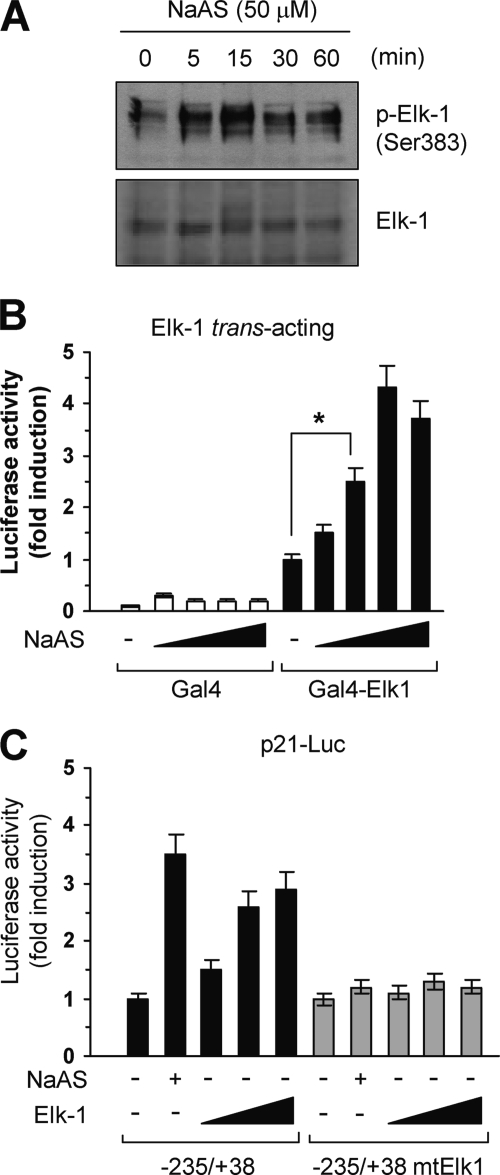

ELK-1 trans-Activates the p21 Promoter in Response to NaASO2

To assess whether ELK-1 is activated by NaASO2 in HaCaT cells, its phosphorylation was examined by Western blotting. NaASO2 treatment increased the levels of ELK-1 phosphorylated on Ser-383 but not overall ELK-1 levels. Phospho-ELK-1 levels peaked at 15 min and thereafter gradually decreased (Fig. 5A). To determine whether NaASO2 stimulates ELK-1-dependent transcriptional activity, we used a trans-acting reporter assay system. HaCaT cells were transfected with a Gal4-Elk-1 plasmid, which encodes a fusion protein comprising the ELK-1 activation domain (residues 387–427) and the DNA-binding domain (DBD) of the yeast transcription factor Gal4. Transfected Gal4-Elk-1 was phosphorylated on Ser-383 following NaASO2 treatment (supplemental Fig. 2). When HacaT cells were co-transfected with Gal4-Elk-1 and a luciferase reporter plasmid (pFR-Luc) containing a Gal4-responsive element, NaASO2 dose-dependently stimulated transcriptional activation mediated by Gal4-Elk-1 but not the Gal4 DBD lacking an activation domain (Fig. 5B). To investigate whether ELK-1 activates the p21 promoter, HaCaT cells were transfected with wild-type (p21-Luc(−235/+38)) or ELK-1 site mutant (p21-Luc(−235/+38)mtElk1) constructs, along with an ELK-1 expression plasmid. Exogenous ELK-1 trans-activated the wild-type −235/+38 construct (even in cells not treated with NaASO2) but not the ELK-1 mutant construct (Fig. 5C). These results suggest that NaASO2 stimulates ELK-1-mediated trans-activation of the p21 promoter via an ELK-1 response element.

FIGURE 5.

ELK-1 trans-activation of the p21 promoter. A, HaCaT cells starved in medium containing 0.5% serum for 24 h were treated with 50 μm NaASO2 for the indicated periods of time. Levels of total ELK-1 and ELK-1 phosphorylated on Ser-383 (p-Elk-1) in whole cell lysates (15 μg/lane) were measured by Western blotting. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. B, HaCaT cells were transiently co-transfected with 50 ng of trans-activator plasmid (pFA2/Gal4 DBD or pFA2/Gal4 DBD-Elk1) and 0.5 μg of luciferase reporter plasmid (pFR/5×Gal4-Luc). After 48 h, cells were serum-starved for 12 h and treated with different concentrations of NaASO2 (10, 25, 50, and 100 μm). After 8 h, luciferase activities were measured. C, HaCaT cells were co-transfected with 0.2 μg of p21 promoter construct p21-Luc(−235/+38) or p21-Luc(−235/+38)mtElk1 and/or 0.1, 0.2, or 0.5 μg of ELK-1 expression plasmid (pCMV/flagElk-1), as indicated. As a positive control, cells were treated with 50 μm NaASO2 for 8 h before being harvested. Then, 48 h after transfection, luciferase activities were measured. Data represent the mean ± S.D. (error bars) of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate (*, p < 0.01).

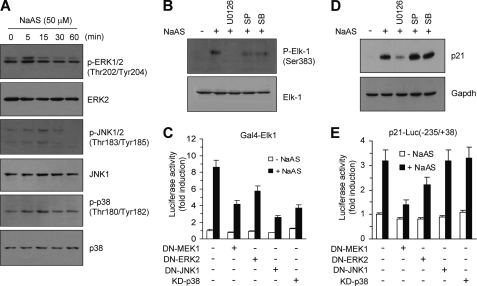

ERK Mediates NaASO2-induced Activation of ELK-1

ELK-1 is phosphoactivated following the activation of multiple MAPK pathways in response to various extracellular stimuli (39–43). To determine the involvement of MAPK pathways in NaASO2-induced p21 expression, serum-starved HaCaT cells were treated with NaASO2 for various periods of time, and the activation of three major MAPKs was measured using phosphospecific antibodies. Levels of phosphorylated ERK1/2, JNK1/2, and p38 MAPK increased rapidly but transiently in response to NaASO2 treatment, whereas the overall levels of these proteins remained unchanged (Fig. 6A), suggesting the activation of these MAPK pathways by NaASO2. To identify the MAPK pathway responsible for NaASO2-induced activation of ELK-1 in HaCaT cells, the effects of chemical inhibitors of MAPK signaling on NaASO2-induced ELK-1 phosphorylation were studied. All three MAPK inhibitors tested (the MEK1 inhibitor U0126, the p38 inhibitor SB203280, and the JNK inhibitor SP600125) strongly inhibited the ability of NaASO2 to induce phosphorylation of ELK-1 on Ser-383 (Fig. 6B). To further determine the contribution of NaASO2-stimulated MAPK signaling to ELK-1 trans-activation, HaCaT cells were transfected with Gal4-Elk1/pFR-Luc trans-acting reporter constructs, along with constructs encoding mutant forms of MAPK signaling molecules. In line with the results obtained using chemical inhibitors, transient expression of DN-MEK1, DN-ERK2, DN-JNK1, or KD-p38 kinase markedly inhibited NaASO2-induced trans-activation by ELK-1 (Fig. 6C). These data indicate that NaASO2 activates ELK-1 through all three MAPK pathways studied.

FIGURE 6.

Involvement of ERK in NaASO2-induced p21 expression. A, HaCaT cells starved in medium containing 0.5% serum for 24 h were treated with 50 μm NaASO2 for the indicated periods of time. Total protein extracts were analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies raised against phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr-202/Tyr-204), phospho-JNK1/2 (Thr-183/Tyr-185), and phospho-p38 kinase (Thr-180/Tyr-182). Antibodies that detect both the unphosphorylated and phosphorylated forms of these MAPK proteins were used as internal controls. B, serum-starved HaCaT cells were pretreated with 5 μm U0126, 10 μm SP600125, or 10 μm SB203580 for 30 min and treated with 50 μm NaASO2. Then, 15 min later, cells were harvested, and total protein extracts were analyzed by Western blotting using antibody raised against phospho-ELK-1 (Ser-383). An antibody that detects both unphosphorylated and phosphorylated ELK-1 was used as an internal control. C, HaCaT cells were co-transfected with 50 ng of ELK-1 trans-activator plasmid pFA/Gal4-Elk1 and 0.5 μg of pFR-Luc and plasmids encoding DN-MEK1, DN-ERK2, DN-JNK1, or KD-p38 (0.2 μg each), as indicated. Then, 48 h later, cells were treated with 50 μm NaASO2 for 8 h, and their luciferase activities were measured. Data represent the mean ± S.D. (error bars) of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. D, serum-starved HaCaT cells were treated with kinase inhibitors and NaASO2 for 24 h (as in B). Then cells were harvested and analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-p21 antibody. Gapdh was used as an internal control. E, HaCaT cells were co-transfected with 0.2 μg of p21-Luc(−235/+38) and DN-MEK1, DN-ERK2, DN-JNK1, or KD-p38 (0.2 μg each), as indicated. Then, 48 h after transfection, cells were treated with 50 μm NaASO2 for 8 h, and their luciferase activities were measured. Data represent the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate.

To determine whether these MAPKs are functionally linked to NaASO2-induced p21 expression, we used Western blotting to examine the effects of chemical inhibitors on the accumulation of p21 protein. Interestingly, pretreatment with the MEK inhibitor U0126, but not the JNK inhibitor SP600125 or the p38 kinase inhibitor SB203580, abrogated the ability of NaASO2 to induce the accumulation of p21 protein (Fig. 6D). Furthermore, transient expression of either DN-MEK1 or DN-ERK2 efficiently attenuated NaASO2-induced activation of the −235/+38 construct of the p21 promoter (Fig. 6E). Collectively, although all three MAPK pathways can activate ELK-1, it seems that only the ERK pathway is critical for NaASO2-induced activation of p21 transcription.

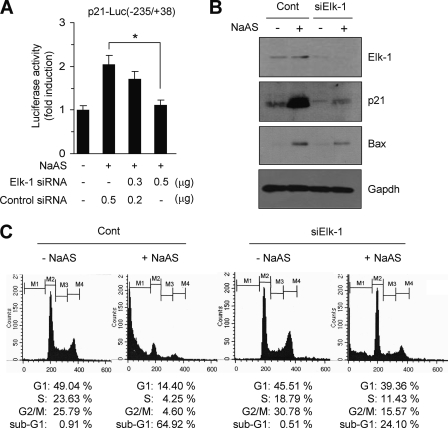

Expression of ELK-1 siRNA Attenuates NaASO2-induced Expression of p21 and Apoptosis

We used RNA interference to test whether silencing endogenous ELK-1 expression reduces p21 expression. When HaCaT cells were transiently transfected with ELK-1 siRNA, along with the −235/+38 construct of the p21 promoter, NaASO2-induced reporter activity was significantly attenuated (Fig. 7A). To further probe the involvement of ELK-1 in NaASO2-induced p21 expression, we established cell lines stably expressing ELK-1 siRNA (HaCaT/siElk-1) or scrambled siRNA (HaCaT/Cont). Stable knockdown of ELK-1 by siRNA was evaluated by Western blotting (Fig. 7B). Silencing endogenous ELK-1 substantially attenuated the ability of NaASO2 to induce p21 expression. Interestingly, we found that NaASO2-induced BAX expression was also reduced in HaCaT/siElk-1 cells. In addition, HaCaT/siElk-1 cells displayed resistance to NaASO2-induced apoptosis and a decline in the G1 population (as compared with control cells; Fig. 7C). These data identify ELK-1 as the transcription factor responsible for NaASO2-induced up-regulation of p21 gene expression and BAX expression.

FIGURE 7.

Effect of ELK-1 silencing on the expression of p21 and BAX. A, HaCaT cells were co-transfected with 0.2 μg each of p21-Luc(−235/+38) and an shRNA plasmid expressing either scrambled control (pSilencer/Cont) or ELK-1 siRNA (pSilencer/siElk-1), as indicated. Then, 48 h later, cells were left untreated or treated with 50 μm NaASO2 for 8 h, and their luciferase activities were measured. Data represent the mean ± S.D. (error bars) of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate (*, p < 0.01). B, silencing of ELK-1 expression in stably transfected HaCaT cells expressing scrambled control (HaCaT/Cont) or ELK-1 siRNA (HaCaT/siElk-1) was verified by Western blotting (top). Exponentially growing HaCaT/Cont and HaCaTsiElk-1 cells were cultured in the presence of absence of 50 μm NaASO2 for 24 h. Then cells were harvested and analyzed by Western blotting using anti-p21 and anti-BAX antibodies. Gapdh was used as an internal control. C, exponentially growing HaCaT/Cont and HaCaT/siElk-1 cells were treated with 50 μm NaASO2 for 24 h. Then cells were harvested, fixed with ethanol, and stained with propidium iodide. Their DNA content was analyzed by flow cytometry. Sub-G1 (M1), G1 (M2), S (M3), and G2/M (M4) cells were identified. The percentage of the cell population at each phase of the cell cycle is indicated.

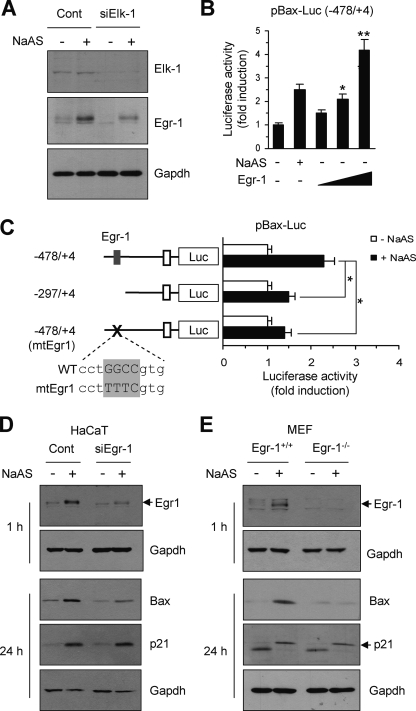

EGR-1 Functions Downstream of ELK-1 to Activate BAX Expression

EGR-1 can directly trans-activate the BAX promoter (56). EGR-1 is a known ELK-1 target and strongly induced by NaASO2. Because no ELK-1-binding elements have been identified in the BAX gene promoter region, we hypothesized that suppression of BAX expression in HaCaT/siElk-1 cells might be mediated by EGR-1. To test this possibility, we investigated the possible involvement of EGR-1 in NaASO2-induced BAX expression. As expected, the ability of NaASO2 to induce EGR-1 expression was substantially attenuated in HaCaT/siElk-1 cells compared with HaCaT/Cont cells (Fig. 8A), indicating that EGR-1 expression is regulated by ELK-1. Forced expression of EGR-1 in HaCaT cells activated the BAX promoter in a plasmid concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 8B). Next, we examined whether the EGR-1-binding sequence in the BAX gene promoter is necessary for NaASO2-induced trans-activation. We showed that site-directed mutation of the EGR-1-binding core sequence within the BAX promoter (acaagcctGGGcgtggg → acaagcctTTTcgtggg) significantly attenuated luciferase reporter activation by NaASO2 (Fig. 8C). These data suggest that activation of the BAX promoter by NaASO2 in HaCaT cells involves ELK-1-mediated EGR-1 expression.

FIGURE 8.

Role of EGR-1 in NaASO2-induced BAX expression. A, serum-starved HaCaT/Cont and HaCaT/siElk-1 cells were treated with 50 μm NaASO2 for 1 h, and their expression of EGR-1 was then measured by Western blot using an anti-EGR-1 antibody. Gapdh was used as an internal control. B, HaCaT cells were co-transfected with 0.2 μg of BAX promoter-reporter plasmid pBax-Luc(−478/+4) and various amounts of the EGR-1 expression plasmid pcDNA3.1zeo/Egr1 (0.1, 0.2, and 0.5 μg). As a positive control, cells were treated with 50 μm NaASO2 for 8 h. Then, 48 h after transfection, luciferase activities were measured. Data represent the mean ± S.D. (error bars) of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate (*, p < 0.01 versus untreated cells). C, HaCaT cells were co-transfected with 0.2 μg of BAX promoter construct (pBax-Luc(−478/+4), -Luc(−297/+4), or -Luc(−478/+4)mtEgr1). The core EGR-1-binding motif is enclosed in a box. After 48 h, cells were treated with 50 μm NaASO2 for 8 h, and luciferase activities were measured. Values for firefly luciferase were normalized to those for Renilla luciferase. Data represent the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate (*, p < 0.01 versus untreated cells). D–E, HaCaT cells expressing scrambled control (Cont) or EGR-1 siRNA (siEgr-1) (D) and Egr-1+/+ or Egr-1−/− MEFs (E) were treated with 50 μm NaASO2 for 1 or 24 h. Then total cell lysates were prepared and tested for the expression of EGR-1, BAX, and p21 by Western blotting. GAPDH was used as an internal control.

To confirm the functional role of EGR-1 in BAX expression, we generated HaCaT/siEgr-1 cells, which stably express EGR-1 siRNA, and determined the effect of stable knockdown of endogenous EGR-1 protein on BAX expression. As shown in Fig. 8D, stable knockdown of EGR-1 expression prevented the ability of NaASO2 to induce BAX, whereas p21 expression was not affected. To further probe the involvement of EGR-1 in NaASO2-induced BAX expression, we prepared primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from Egr-1 wild-type (+/+) and Egr-1 knock-out (−/−) mice. The induction of BAX expression by NaASO2 was greatly reduced in Egr-1−/− MEFs, whereas p21 expression was not affected as compared with Egr-1+/+ cells (Fig. 8E). Given that MEFs contain wild-type p53, it is likely that EGR-1 mediates NaASO2-induced BAX expression in a variety of cell types, regardless of their p53 expression.

DISCUSSION

Epidemiological studies have shown that long term exposure to low concentrations of arsenite is associated with an increased risk of human cancers, including those of the skin, respiratory tract, hematopoietic system, and urinary bladder (57). Based on this information, the International Agency for Research on Cancer and the United States Environmental Protection Agency classified arsenite as a human carcinogen. The general population is exposed to arsenic through the air, soil, drinking water, food, and beverages. The amount of ingested arsenic appears to be dependent upon living environment, life style, and dietary patterns. However, the relationship between the dose of ingested arsenite and the cumulative concentrations in the body is currently unknown. The effect of low arsenite concentrations on the transformation of cells has been well studied (14–16); however, the cytotoxic mechanism induced by high arsenite doses is unclear.

In this work, we investigated the effect of high NaAsO2 concentration on cytotoxicity using a p53-mutated HaCaT model cell system. Herein, we provide evidence that, in response to NaASO2 treatment, ERK activates ELK-1, an ETS family transcription factor, which in turn trans-activates a putative cis-acting response element within the p21 promoter to induce p21 expression (p53- and EGR-1-independently). Furthermore, we show that an ERK/ELK-1 cascade indirectly activates the BAX promoter via induction of EGR-1. We suggest that NaASO2-induced p21 and BAX expression is highly dependent on ERK/ELK-1 signaling in p53-mutated HaCaT keratinocytes.

Our data show that exposing HaCaT cells to high concentrations of NaASO2 (≥50 μm) inhibits the cell cycle and induces apoptosis. These responses may stem from up-regulation of p21 and BAX expression as well as down-regulation of cyclins D1, A1, and B. Because the induction of p21 by NaASO2 in HaCaT cells preceded the down-regulation of other cell cycle-regulatory proteins, we suggest that up-regulation of p21 and BAX expression may represent an important mechanism by which NaASO2 causes cytotoxicity. Thus, this study focused on the mechanisms behind p53-independent p21 and BAX gene expression in NaASO2-exposed HaCaT cells.

UVB increases the expression of p53, as well as p21 and BAX, leading to apoptosis even in cells carrying mutations in both p53 alleles (45). We thus tested whether NaASO2 activates p53 in HaCaT cells. We showed that neither the expression nor transcriptional activity of p53 was affected by NaASO2 treatment. In addition, a p21 promoter construct lacking a p53-binding site was not activated by NaASO2. We therefore concluded that p53 was inessential to NaASO2-induced p21 expression, at least in HaCaT cells. Because NaASO2 up-regulates EGR-1 expression in HaCaT cells (54), and EGR-1 stimulates transcription of the p21 gene by binding to specific sequences within its promoter (48–49, 55), we examined the possible involvement of EGR-1 in NaASO2-induced up-regulation of p21 gene expression. Unexpectedly, we found no evidence for the involvement of EGR-1 in the regulation of NaASO2-induced p21 expression in HaCaT cells; the −150/+38 p21 promoter construct, which contains the EGR-1 site, did not respond to NaASO2, whereas transient transfection of EGR-1 siRNA had no effect on NaASO2-induced p21 promoter activity.

To identify the cis-acting response element that mediates NaASO2-induced p21 gene expression, we performed 5′-deletion analysis of the p21 promoter. We found that the promoter region spanning positions −235 to −150 is indispensable to the regulation of NaASO2-stimulated p21 promoter activity in HaCaT cells. Inspection of this region revealed the presence of a putative ELK-1-binding core motif, 5′-TTCC-3′, complementary to the core motif, 5′-GGAA-3′, in the antisense strand. Through mutational analysis of the p21 promoter, we demonstrated that disruption of this core ELK-1 binding motif (TTCC → TTGG) completely abrogated NaASO2-induced activation of the p21 promoter. Furthermore, we showed that forced expression of ELK-1 itself enhanced p21 promoter activity and that the introduction of ELK-1-specific siRNA into HaCaT cells efficiently attenuated NaASO2-induced p21 promoter activity. Direct binding of ELK-1 to the p21 promoter was confirmed by EMSA and ChIP assay. These results strongly suggest that ELK-1 participates directly in NaASO2-induced activation of the p21 promoter. Our data also show that NaASO2 activated three major MAPKs (ERK, JNK, and p38 kinase) in HaCaT cells. However, only the ERK pathway was critical to NaASO2-induced p21 expression in HaCaT cells, as revealed using chemical inhibitors and dominant negative MAPK mutant constructs. NaASO2 induces p21 expression via p38 MAPK in NIH3T3 cells (20) and via JNK in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (21). Because ELK-1 is a well known target of three major MAPKs (39–41), it may separately contribute to ERK-, JNK-, or p38-induced p21 expression, depending on the cellular context.

The ternary complex factor subfamily of ETS transcription factors, whose members include ELK-1, SAP-1, and SAP-2/ERP/Net, has been implicated in the regulation of gene expression, including that of immediate early response genes, such as FOS and EGR-1, in response to a variety of extracellular signals, through cooperative interactions with serum response element-bound SRF (39–41, 43). However, ELK-1 can trans-activate its binding elements in the absence of SRF, for example within the mouse cytosolic chaperonin θ subunit (Cctq) gene promoter (58). Indeed, a whole group of ELK-1 target genes are largely regulated in an SRF-independent manner (59). Because no serum response element site has been identified in the p21 promoter, the binding of ELK-1 to the p21 promoter provides a further example of ELK-1 controlling target gene expression without associating with SRF.

The transcription factor SP1 plays a role in ERK-mediated p21 transcription in various cell types, including nerve growth factor-treated PC12 cells (60), Ras-transformed NIH3T3 cells (61), alkylphospholipid-treated HaCaT cells (33), and arsenic trioxide-exposed A431 epidermoid carcinoma cells (62). ETS and C/EBPβ (63) are also involved in ERK-dependent, p53-independent expression of p21 expression in primary hepatocytes. Therefore, it is possible that the induction of p21 expression by ERK involves multiple cis-acting elements. However, it should be noted that NaASO2 also trans-activated a −235/+38 construct lacking two ETS-binding sites at −1574 and −1347 (64) and a C/EBPβ-binding site at −1924 (63), but not a −150/+38 construct containing multiple SP1 sites (−119/−77) and an AP2 site at −102 (65). Furthermore, the −235/+38mtElk1 construct, which carries a mutated ELK-1-binding sequence, but intact SP1 sites, was barely activated by NaASO2. Thus, we suggest that the ETS, C/EBPβ, and SP1 sites, which can be activated by ERK signaling, might not be essential for NaASO2 activation of the p21 promoter in HaCaT cells. Nonetheless, we do not preclude the possibility that these transcription factors do contribute to full activation of the p21 promoter by NaASO2. Because the tumor suppressor BRCA1 activates the p21 promoter in a p53-independent fashion via the proximal region between −143 and −93 (66–67), and the interaction of ELK-1 with BRCA1 enhances growth suppression in breast cancer cells (68), ELK-1 may interact with multiple nuclear proteins to enhance transcriptional activity in the proximal region of the p21 promoter.

Silencing of ELK-1 expression by RNAi in HaCaT cells resulted in reduced p21 and BAX expression in response to NaASO2 exposure and conferred resistance to NaASO2-induced apoptosis. Given that (i) no consensus ELK-1-binding motif has been identified in the BAX promoter (69), EGR-1 can directly trans-activate the BAX promoter (56), and (iii) both EGR-1 and BAX levels were reduced by ELK-1 silencing, it is likely that EGR-1 plays a role in the induction of BAX by NaASO2. To test this idea, we transiently transfected HaCaT cells with EGR-1 siRNA. We found that NaASO2-induced BAX promoter activity was dose-dependently abrogated by transfection with EGR-1 siRNA. Our observation that NaASO2-induced BAX expression was largely abolished in MEFs from Egr-1 knock-out mice and in HaCaT cells expressing EGR-1 siRNA (HaCaT/siEgr-1) further supports a role for EGR-1 in NaASO2-induced BAX expression. Because MEFs express wild-type p53 and HaCaT cells contain the p53 mutation, it seems likely that EGR-1 activates BAX expression irrespective of p53 status. Because EGR-1 is up-regulated by the ERK/ELK-1 pathway, it appears that ELK-1 indirectly regulates BAX expression via EGR-1 in p53-mutated HaCaT cells.

Previous studies have shown that EGR-1 mediates radiation-induced apoptosis. For example, direct trans-activation of the BAX promoter in irradiated prostate cancer cells has been reported (56), suggesting that EGR-1 is proapoptotic under certain cellular conditions. However, although BAX expression was significantly reduced in HaCaT/siEgr-1 cells compared with HaCaT/Cont cells, the cleavage of caspase-2 and -7 (supplemental Fig. 1A) and apoptosis (supplemental Fig. 1B) were similarly induced by NaASO2 treatment in both cell types. These findings suggest that EGR-1-mediated BAX induction is insufficient to induce NaASO2-induced apoptosis in HaCaT cells. Although the mechanisms of p21 apoptotic regulation are poorly understood, p21 can promote apoptosis under certain circumstances (70, 71). For example, p21 overexpression enhances cisplatin-induced cell death in ovarian carcinoma cells (72), and the silencing of p21 by RNAi in HaCaT cells indicates that p21 functions in UVA-induced apoptosis and the G1/S phase cell cycle arrest (73). Thus, we suggest that the accumulation of p21 may play an important role in NaASO2-induced cytotoxicity through cell cycle dysregulation and apoptosis in HaCaT cells. Further study is required to determine the mechanism of p21-induced apoptosis.

In summary, our present study reveals that NaASO2-induced up-regulation of p21 and BAX expression was mediated by an ERK/ELK-1 cascade in p53-mutated HaCaT cells. ELK-1 directly transactivates the p21 gene promoter via a specific cis-acting element and indirectly stimulates the BAX gene via induction of EGR-1. We conclude that NaASO2-induced cytotoxicity in p53-mutated HacaT cells is highly dependent on ERK/ELK-1 signaling, further extending our understanding of the regulatory mechanism by which MAPK signaling contributes to cellular cytotoxicity.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by Disease Network Research Program Grant 20090084181 and Basic Research Promotion Fund Grants KRF-2008-314-C00290 and NRF-2010-0014208 from the National Research Foundation of Korea, funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, Republic of Korea. This work was also supported by the SMART Research Professor Program of Konkuk University.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1 and 2.

- DN

- dominant negative

- KD

- kinase-dead

- PARP

- poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

- DBD

- DNA-binding domain

- MEF

- mouse embryo fibroblast.

REFERENCES

- 1. el-Deiry W. S., Tokino T., Velculescu V. E., Levy D. B., Parsons R., Trent J. M., Lin D., Mercer W. E., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B. (1993) Cell 75, 817–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gartel A. L., Tyner A. L. (2002) Mol. Cancer Ther. 1, 639–649 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coqueret O. (2003) Trends Cell Biol. 13, 65–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. el-Deiry W. S., Harper J. W., O'Connor P. M., Velculescu V. E., Canman C. E., Jackman J., Pietenpol J. A., Burrell M., Hill D. E., Wang Y. (1994) Cancer Res. 54, 1169–1174 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chan T. A., Hwang P. M., Hermeking H., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B. (2000) Genes Dev. 14, 1584–1588 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Waldman T., Lengauer C., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B. (1996) Nature 381, 713–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Harper J. W., Adami G. R., Wei N., Keyomarsi K., Elledge S. J. (1993) Cell 75, 805–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Charrier-Savournin F. B., Château M. T., Gire V., Sedivy J., Piette J., Dulic V. (2004) Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 3965–3976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Baus F., Gire V., Fisher D., Piette J., Dulić V. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 3992–4002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bunz F., Dutriaux A., Lengauer C., Waldman T., Zhou S., Brown J. P., Sedivy J. M., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B. (1998) Science 282, 1497–1501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gillis L. D., Leidal A. M., Hill R., Lee P. W. (2009) Cell Cycle 8, 253–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gartel A. L., Tyner A. L. (1999) Exp. Cell Res. 246, 280–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Qian Y., Castranova V., Shi X. (2003) J. Inorg. Biochem. 96, 271–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tchounwou P. B., Yedjou C. G., Dorsey W. C. (2003) Cell Mol. Biol. 49, 1071–1079 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huang C., Ke Q., Costa M., Shi X. (2004) Mol. Cell Biochem. 255, 57–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ouyang W., Ma Q., Li J., Zhang D., Liu Z. G., Rustgi A. K., Huang C. (2005) Cancer Res. 65, 9287–9293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Huang C., Ma W. Y., Li J., Goranson A., Dong Z. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 14595–14601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dong Z. (2002) Environ. Health Perspect. 110, 757–759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bode A. M., Dong Z. (2002) Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 42, 5–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim J. Y., Choi J. A., Kim T. H., Yoo Y. D., Kim J. I., Lee Y. J., Yoo S. Y., Cho C. K., Lee Y. S., Lee S. J. (2002) J. Cell. Physiol. 190, 29–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nuntharatanapong N., Chen K., Sinhaseni P., Keaney J. F., Jr. (2005) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 289, H99–H107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sidhu J. S., Ponce R. A., Vredevoogd M. A., Yu X., Gribble E., Hong S. W., Schneider E., Faustman E. M. (2006) Toxicol. Sci. 89, 475–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chou R. H., Huang H. (2002) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 293, 298–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Huang H. S., Chang W. C., Chen C. J. (2002) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 33, 864–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liebmann C. (2001) Cell. Signal. 13, 777–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Treisman R. (1996) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 8, 205–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Whitmarsh A. J., Davis R. J. (1996) J. Mol. Med. 74, 589–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kim E. K., Choi E. J. (2010) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1802, 396–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cowley S., Paterson H., Kemp P., Marshall C. J. (1994) Cell 77, 841–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wu G. S. (2004) Cancer Biol. Ther. 3, 156–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Persons D. L., Yazlovitskaya E. M., Pelling J. C. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 35778–35785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ciccarelli C., Marampon F., Scoglio A., Mauro A., Giacinti C., De Cesaris P., Zani B. M. (2005) Mol. Cancer 4, 41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. De Siervi A., Marinissen M., Diggs J., Wang X. F., Pages G., Senderowicz A. (2004) Cancer Res. 64, 743–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Facchinetti M. M., De Siervi A., Toskos D., Senderowicz A. M. (2004) Cancer Res. 64, 3629–3637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pumiglia K. M., Decker S. J. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 448–452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tu Y., Wu W., Wu T., Cao Z., Wilkins R., Toh B. H., Cooper M. E., Chai Z. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 11722–11731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Beier F., Taylor A. C., LuValle P. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 30273–30279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Datto M. B., Li Y., Panus J. F., Howe D. J., Xiong Y., Wang X. F. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 5545–5549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Buchwalter G., Gross C., Wasylyk B. (2004) Gene 324, 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sharrocks A. D. (2002) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 30, 1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shaw P. E., Saxton J. (2003) Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 35, 1210–1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yang S. H., Sharrocks A. D. (2006) Biochem. Soc. Symp. 73, 121–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shore P., Sharrocks A. D. (1994) Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 3283–3291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lin L., Stringfield T. M., Shi X., Chen Y. (2005) Biochem. J. 392, 93–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lehman T. A., Modali R., Boukamp P., Stanek J., Bennett W. P., Welsh J. A., Metcalf R. A., Stampfer M. R., Fusenig N., Rogan E. M. (1993) Carcinogenesis 14, 833–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bunz F., Hwang P. M., Torrance C., Waldman T., Zhang Y., Dillehay L., Williams J., Lengauer C., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B. (1999) J. Clin. Invest. 104, 263–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Aicher W. K., Sakamoto K. M., Hack A., Eibel H. (1999) Rheumatol. Int. 18, 207–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Choi B. H., Kim C. G., Bae Y. S., Lim Y., Lee Y. H., Shin S. Y. (2008) Cancer Res. 68, 1369–1377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kim C. G., Choi B. H., Son S. W., Yi S. J., Shin S. Y., Lee Y. H. (2007) Cell. Signal. 19, 1290–1300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Goueli B. S., Janknecht R. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 25–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shin S. Y., Kim J. H., Baker A., Lim Y., Lee Y. H. (2010) Mol. Cancer Res. 8, 507–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yang S. H., Sharrocks A. D. (2005) EMBO J. 24, 2161–2171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lazebnik Y. A., Kaufmann S. H., Desnoyers S., Poirier G. G., Earnshaw W. C. (1994) Nature 371, 346–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Al-Sarraj A., Thiel G. (2004) J. Mol. Med. 82, 530–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ragione F. D., Cucciolla V., Criniti V., Indaco S., Borriello A., Zappia V. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 23360–23368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zagurovskaya M., Shareef M. M., Das A., Reeves A., Gupta S., Sudol M., Bedford M. T., Prichard J., Mohiuddin M., Ahmed M. M. (2009) Oncogene 28, 1121–1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bettley F. R., O'Shea J. A. (1975) Br. J. Dermatol. 92, 563–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yamazaki Y., Kubota H., Nozaki M., Nagata K. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 30642–30651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Boros J., O'Donnell A., Donaldson I. J., Kasza A., Zeef L., Sharrocks A. D. (2009) Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 7368–7380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yan G. Z., Ziff E. B. (1997) J. Neurosci. 17, 6122–6132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kivinen L., Tsubari M., Haapajärvi T., Datto M. B., Wang X. F., Laiho M. (1999) Oncogene 18, 6252–6261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Liu Z. M., Huang H. S. (2006) Cell. Signal. 18, 244–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Park J. S., Qiao L., Gilfor D., Yang M. Y., Hylemon P. B., Benz C., Darlington G., Firestone G., Fisher P. B., Dent P. (2000) Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 2915–2932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zhang C., Kavurma M. M., Lai A., Khachigian L. M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 27903–27909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zeng Y. X., Somasundaram K., el-Deiry W. S. (1997) Nat. Genet. 15, 78–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Somasundaram K., Zhang H., Zeng Y. X., Houvras Y., Peng Y., Zhang H., Wu G. S., Licht J. D., Weber B. L., El-Deiry W. S. (1997) Nature 389, 187–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lu M., Arrick B. A. (2000) Oncogene 19, 6351–6360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Chai Y., Chipitsyna G., Cui J., Liao B., Liu S., Aysola K., Yezdani M., Reddy E. S., Rao V. N. (2001) Oncogene 20, 1357–1367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Aono J., Yanagawa T., Itoh K., Li B., Yoshida H., Kumagai Y., Yamamoto M., Ishii T. (2003) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 305, 271–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Gartel A. L. (2005) Leuk. Res. 29, 1237–1238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Cazzalini O., Scovassi A. I., Savio M., Stivala L. A., Prosperi E. (2010) Mutat. Res. 704, 12–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lincet H., Poulain L., Remy J. S., Deslandes E., Duigou F., Gauduchon P., Staedel C. (2000) Cancer Lett. 161, 17–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kweon M. H., Afaq F., Bhat K. M., Setaluri V., Mukhtar H. (2007) Oncogene 26, 3559–3571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.