Abstract

Filamins are scaffold proteins that bind to various proteins, including the actin cytoskeleton, integrin adhesion receptors, and adaptor proteins such as migfilin. Alternative splicing of filamin, largely constructed from 24 Ig-like domains, is thought to have a role in regulating its interactions with other proteins. The filamin A splice variant-1 (FLNa var-1) lacks 41 amino acids, including the last β-strand of domain 19, FLNa(19), and the first β-strand of FLNa(20) that was previously shown to mask a key binding site on FLNa(21). Here, we present a structural characterization of domains 18–21, FLNa(18–21), in the FLNa var-1 as well as its nonspliced counterpart. A model of nonspliced FLNa(18–21), obtained from small angle x-ray scattering data, shows that these four domains form an L-shaped structure, with one arm composed of a pair of domains. NMR spectroscopy reveals that in the splice variant, FLNa(19) is unstructured whereas the other domains retain the same fold as in their canonical counterparts. The maximum dimensions predicted by small angle x-ray scattering data are increased upon migfilin binding in the FLNa(18–21) but not in the splice variant, suggesting that migfilin binding is able to displace the masking β-strand and cause a rearrangement of the structure. Possible function roles for the spliced variants are discussed.

Keywords: Actin, Integrin, NMR, Protein Domains, Protein Folding, Filamin, SAXS, Migfilin, Spliced Variant

Introduction

Filamins are large actin-binding proteins that stabilize three-dimensional F-actin networks and link them to the cell membrane by binding to transmembrane receptors, e.g. integrins or ion channels. In addition, filamins bind to various other proteins with diverse function, including signaling and adaptor proteins, such as migfilin (1–6). Accordingly, filamins are considered as scaffolding proteins that integrate multiple cellular functions. Filamins are also associated with various human genetic diseases including malformations of the skeleton, brain, and heart (5).

The filamin family has three members; filamins (FLNs)4 A, B and C. The FLN genes are highly conserved, and the encoded proteins share about 70% overall sequence identity (6). FLNA is located on the X chromosome, whereas FLNB and FLNC are on autosomal chromosomes 3 and 7 (6). All three FLN genes are widely expressed during development, but in adults the most abundant isoform is FLNA. FLNC expression is predominantly restricted to skeletal and cardiac muscle cells (3). FLN proteins are homodimers of two 280-kDa polypeptide chains consisting of an N-terminal actin binding domain followed by 24 immunoglobulin (Ig)-like domains (FLN(1–24)) (6). The last domain, FLN(24), mediates dimerization (Fig. 1A) (7, 8). A flexible hinge region (H1) between domains 15 and 16 divides the chain of 24 Ig-like domains into rod 1 (FLN(1–15)) and rod 2 (FLN(16–24)) (Fig. 1A) (9). A second hinge (H2) is found between domains 23 and 24. The rod 2 domains FLN(16–21) form domain pairs of which 18–19 and 20–21 have unusual interrepeat interaction, where the first strand of even numbered domains (18 and 20) is folded with the preceding odd numbered domain (Fig. 1) (10, 11). A similar intertwined interaction is, however, not seen with the domain pair FLNa(16–17) (10).

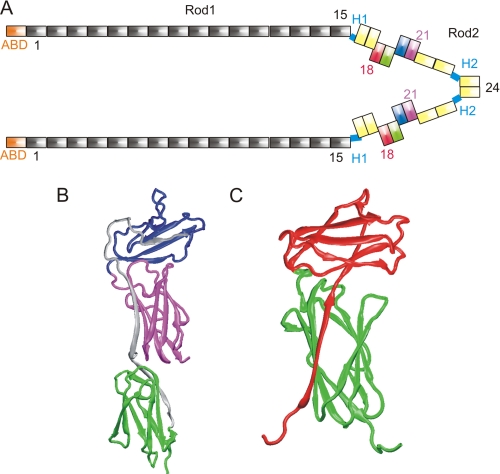

FIGURE 1.

Location and the structures of the domains studied. A, schematic representation of human FLNa. The N-terminal actin binding domains (ABDs) are shown in orange. The Ig-like FLN domains, here termed FLNa(1–24), are shown in rod 1 (FLNa(1–15)) in gray; FLNa(16–17) and FLNa(22–24) in rod 2 are in yellow. The domains in FLNa(18–21), which are studied here, are colored as follows: FLNa(18), red; FLNa(19), green; FLNa(20), blue; and FLNa(21), magenta. The C-terminal domains, FLNa(24), are the dimerization domains. B, crystal structure of FLNa(19–21) (Protein Data Bank ID code 2J3S) (11). Domains are colored as in A. Amino acids that are missing from var-1 are shown in gray. C, solution structure of human FLNa(18–19) (Protein Data Bank ID code 2K7Q) (10) domain pair shown as scheme. Domains are colored as in A.

The diversity of the filamin family is increased by alternative splicing of FLN mRNA. These changes in amino acid sequence can affect the binding of other interacting partners. FLNa and FLNb splice variants (var-1), which are widely expressed at low levels, lack 41 amino acids including the C-terminal part of FLNa(19) and the N-terminal part of FLNa(20) (residues 2127–2167) (6, 12). This includes the first β-strand of FLNa(20) (Fig. 1B) that masks the integrin and migfilin binding site at the CD face of FLNa(21) (11, 13–16) (Fig. 1B). FLN var-1 binding to various integrins is increased compared with nonspliced filamins (11, 12), implying that alternative splicing could be a possible regulatory mechanism for binding to integrin and other interaction partners. Other possible mechanisms include mechanical force-induced exposure of the cryptic binding site on the CD face (17, 18) and/or the binding of other binding partners.

Other splice variants are also found in FLNb and FLNc. The hinge region H1, which is responsible for the flexibility of FLN dimers, is missing in some FLNb and FLNc splice variants (12). Its absence might therefore affect the orthogonal cross-linking patterns made by FLN. The expression of different FLN splice variants appears to differ according to tissue type. The predominant isoforms in thyroid are FLNb containing H1 and FLNc lacking H1 (ΔH1) (19, 20). In some cases, localization of FLN is dependent on the alternative splicing, e.g. FLNb ΔH1 is localized at the tips of actin stress fibers in myotubes. This deletion has also been shown to accelerate the differentiation of myoblast cells in myotubes compared with the canonical isoform (12). There are also two other splice variants found in FLNb, var-2 and var-3, which lack the four C-terminal domains, including the 24th dimerization domain (12). These FLNB-specific transcripts were shown to be cardiac-specific (12).

Here, we obtain structural models of the FLNa fragment containing domains 18–21 and its splice variant-1. The FLNa(18–21) model, constructed using small angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) data, shows that the two domain pairs are roughly perpendicular to each others. Structural characterization with NMR shows that FLNa(19) var-1 is largely unstructured. The binding site located in FLNa(19) is abolished in the splice variant. SAXS analysis of the splice variant FLNa(18–21) var-1 shows that it mainly exists as a rather compact form with average dimensions similar to the corresponding nonspliced isoform. Our results also reveal that migfilin binding induces a conformational change in FLNa(18–21) but not in the splice variant.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Recombinant Proteins

FLNa fragments were amplified by PCR and cloned into modified pGEX vector (GE Healthcare) with a tobacco etch virus protease cleavage site. The domain boundaries were based on the publication of Ref. 6. The I2092C and I2283C mutations were introduced by QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene). GST fusion proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21 GOLD and purified as previously described (10).

NMR

15N uniform labeling for the FLNa protein samples (FLNa(18–21), FLNa(18–21) var-1, FLNa(19–21), FLNa(19–21) var-1, FLNa(19–20) var-1, and FLNa(20) var-1) was achieved by using E. coli expression in standard M9 minimal medium. The purification was done as published previously (11, 13). All the filamin fragments were further purified and analyzed by passing down a Superdex 75 column on an Äkta FPLC system. The identity and purity of the products were confirmed by SDS-PAGE and size exclusion chromatography. The β7 integrin (776PLYKSAITTTINP788)-derived peptide for NMR-based binding studies was the non-isotope-labeled Pro776–Pro788 as described previously (21).

All NMR samples were buffered with 50 mm sodium phosphate (pH 6.10 or 7.00) containing 100 mm NaCl, 5 mm DTT (only for proteins with cysteine), and 0.02% sodium azide in 90% H2O and 10% D2O. A water flip-back gradient enhanced heteronuclear single quantum correlation spectroscopy (HSQC) pulse sequence was used for protein characterization and protein-ligand studies. The protein backbone dynamics were measured with heteronuclear NOE experiments as described previously (21). All spectra were recorded at 1H frequencies of 600-, 750-, and 950-MHz instruments. All spectra were referenced to the water proton shift. NMR data processing was carried out with NMRPipe (22) and Sparky.

ThermoFluor Assays

Protein thermal stability was determined using Bio-Rad C1000 Thermal cycler, CFx96 Real-Time system. Protein unfolding was monitored by measuring the fluorescence of environment sensitive fluorescent dye SYPRO Orange (Invitrogen). A temperature increment 0.5 °C/30 s from 20 °C to 95 °C was applied. Samples contained 10 μm protein and 5× SYPRO Orange dye in total volume of 25 μl.

Limited Proteolysis

FLNa(18–21) wild-type and variant-1 constructs were analyzed by limited proteolysis with α-chymotrypsin (Sigma). Protease was added to protein in a 1:1000 ratio. Proteolysis reactions were performed in 20 mm Tris (pH 8.0), 100 mm NaCl, 1 mm DTT at room temperature. Samples were taken after various incubation time intervals and analyzed in 12% SDS-PAGE.

N-terminal Sequencing

For N-terminal sequencing the protein fragments were run on 12.5% SDS-PAGE (23), electroblotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (24) and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. The protein bands of interest were then cut out and subjected to N-terminal sequencing using a Procise 494A Sequencer (PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

Binding Assays

The migfilin peptide (5PEKRVASSVFITLAP19) and the mutant peptide I15E (5PEKRVASSVFETLAP19), used as a negative control, were ordered from EZBiolab (Westfield, IN). The peptides were coupled to NHS-activated SepharoseTM 4 Fast-Flow (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The Sepharose was centrifuged at 2000 × g for 2 min and washed three times with 500 μl of the binding buffer. Proteins were then eluted with 10 μl of SDS-electrophoresis sample buffer and run on a SDS-PAGE. The intensities of Coomassie-stained protein bands were evaluated by ImageJ. The affinity constant were estimated as in Ref. 15.

SAXS

SAXS data were collected at the EMBL beamline X33 at the DORIS III storage ring, DESY (Hamburg, Germany) (25). The measurements were carried out at 288 K in 20 mm Tris (pH 8.0), 100 mm NaCl, 10 mm DTT. The concentrations of FLNa fragments were adjusted to 3–6 mg/ml, and fragments and peptides were used in the molar ratio of 1:10. A MAR345 image plate was used, at a sample-detector distance of 2.7 m and wavelength λ = 0.15 nm, covering the momentum transfer range 0.08 < s < 4.9 nm−1 (s = 4π sin(θ)/λ where 2θ is the scattering angle). The data were processed using standard procedures by the program package PRIMUS (43). The radius of gyration (Rg) and maximum dimension (Dmax) of the FLNa(18–21) fragment were evaluated using the programs GUNIER and GNOM (26). The degree of compactness of both fragments was analyzed using Kratky plots (s2 I(s) versus s).

To assess the conformational variability of FLNa splicing variant-1, the ensemble optimization method (EOM) method (27) was used; this allows for the coexistence of multiple conformations is solution. 10,000 randomized models of the FLNa(18–21) var-1 with different conformations of the unstructured polypeptide chain (residues 2045–2126) were generated using both random coil and native options in RanCh. The scattering profiles of these randomly generated conformations were compared using program RanCh of the EOM package. The EOM program employs a genetic algorithm to select a small number of representative structures (here we used 20) from the pool such that the average scattering from the selected ensemble fits the experimental data. Multiple runs of EOM were performed, and the results were averaged to provide quantitative information about the flexibility of the protein in solution (in particular, the Rg and Dmax distributions in the selected ensembles).

The conformational variability of FLNa(18–21) in the presence of the migfilin peptide was also calculated using the EOM method (27) in a similar way to FLNa(18–21) var-1. Residues 2140–2167, which includes the first β-strand of FLNa(20), were assumed to be unstructured.

The ab initio envelopes were obtained by averaging 20 independent runs from the bead modeling program GASBOR (34) by the program DAMAVER (28). The rigid-body modeling of FLNa(19–21) and FLNa(18–21) were performed with the program SASREF (29). As rigid bodies for FLNa(19–21) solution model a single domain FLNa(19) and a domain pair FLNa(20–21) (Protein Data Bank ID code 2J3S) (11) were used, and for FLNa(18–21) solution model FLNa domain pairs 18–19 (Protein Data Bank ID code 2K7Q) (10) and 20–21 (2J3S) (11) were used. The rigid-body models were fitted into the ab initio envelopes using the SITUS program package (30). Figs. 1, 5, 7, and 9 were generated with VMD (31) and rendered with Raster3D (32).

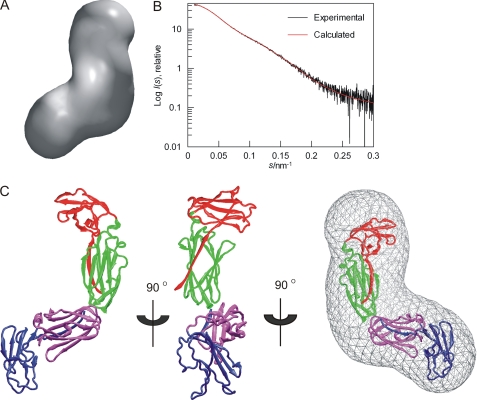

FIGURE 5.

SAXS-based models of FLNa(18–21). A, averaged ab initio envelope of FLNa(18–21) obtained by GASBOR and averaged by DAMAVER. B, fit of rigid body model (red) to experimental scattering curve (black). C, rigid-body model of FLNa(18–21) based on the experimental scattering data presented as a scheme. Domains are colored as following: FLNa(18), red; FLNa(19), green; FLNa(20), blue; and FLNa(21), magenta. The model is shown in three different views rotated by 90° around the y axis. The last view displays the model fitted into the ab initio envelope shown in A.

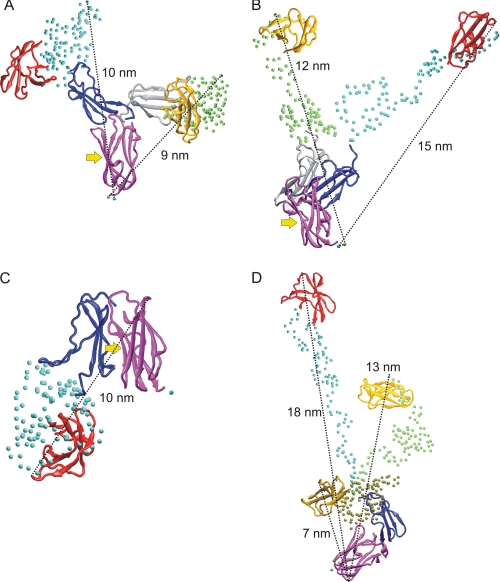

FIGURE 7.

Examples of FLNa(18–21) var-1 conformers selected by EOM. Three separate rigid bodies were used in A–C and two in D. A and B, two compact conformers, which are the most frequently found (A) and two extended conformers (B) are shown. C, a conformer, where the integrin and migfilin binding site on FLNa(21) is masked by the FLNa(20) is shown. A–C, the integrin and migfilin binding site is marked with an arrow. In all panels the domains are colored as follows: FLNa(18), red/yellow/ochre; FLNa(20), blue/gray; and FLNa(21), magenta. Cα atoms of unstructured regions are shown as spheres (cyan, green, or tan). Approximate maximum distances in all structures are shown. All conformers are superimposed on FLNa(21).

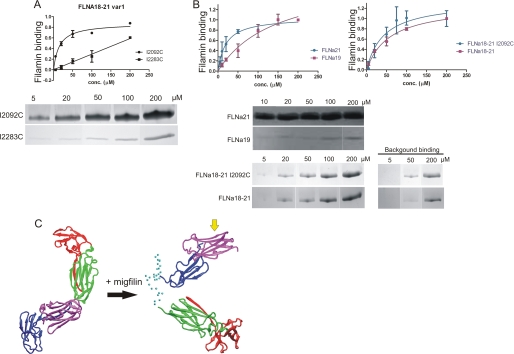

FIGURE 9.

Migfilin binding to FLNa(19), FLNa(21), FLNa(18–21), and FLNa(18–21) var-1. A, binding assays show that in FLNa(18–21) var-1 the binding site at FLNa(19) is lost. Migfilin peptide (5–19) binding to FLNa(18–21) var-1 I2092C and I2203C mutants in 5, 20, 50, 100, and 200 μm concentrations is shown. FLNa(18–21) var-1 I2092C and I2203C mutants binding to migfilin was quantified by protein staining and expressed as filamin binding (in arbitrary units) calculated as the ratio of filamin bound to filamin in the loading control, normalized to maximal filamin binding in each experiment (mean ± S.E. (error bars); n ≥ 4). Background binding is subtracted from the picture. B, binding assays show that the both binding sites at FLNa(19) and FLNa(21) are masked in FLNa(18–21), but migfilin can displace the masking β-strands and bind to FLNa(18–21). Binding is quantified as in A. C, SAXS-based model of FLNa(18–21) with migfilin bound. Right shows FLNa(18–21) before migfilin binding, and left is when migfilin is bound. FLNa(18) is shown in red, FLNa(19) in green, FLNa(20) in blue, and FLNa(21) in magenta. Cα atoms of unstructured regions are shown as cyan spheres. The migfilin binding site at the CD-face of FLNa(21) is shown with a yellow arrow.

RESULTS

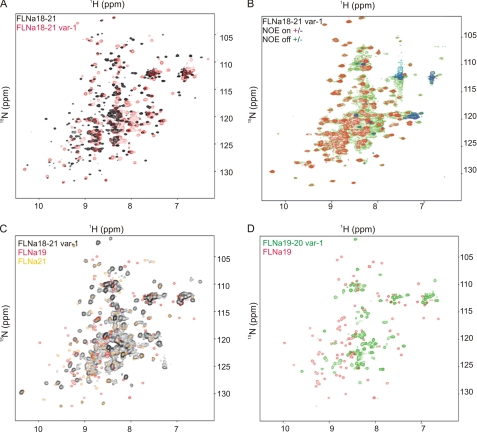

NMR Reveals that FLNa(19) Is Well Folded in FLNa(18–21) but Is Intrinsically Unfolded in FLNa Var-1

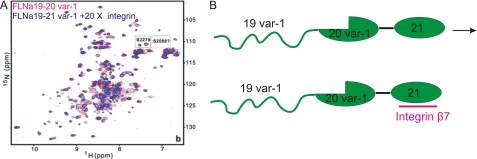

The solution behavior of FLNa(18–21) and FLNa(18–21) var-1 fragments was first studied by NMR. The HSQC spectrum of FLNa(18–21) var-1 is very different from that of the canonical isoform (Fig. 2A). The NMR HSQC spectra of domain pairs and the four-domain 18–21 fragment are very similar (Fig. 2), whereas many peaks are missing in the splice variant, even when the 41 deleted residues are taken into account. Some peaks in spectra from the variant were broadened and clustered in the middle of spectrum. Spectra from shorter FLNa fragments, FLNa(19–20) var-1 FLNa(19–21) var-1, and FLNa(20) var-1, were also collected (Fig. 2D and supplemental Fig. S1). Comparison of the spectrum of FLNa(18–21) var-1 with those of the individual domains and FLNa(18–21) showed that peaks from FLNa(19) are missing or changed, whereas those of FLNa(21) mostly retain their positions (Fig. 2C). A heteronuclear 1H-15N NOE experiment further revealed that many residues had increased backbone dynamics (Fig. 2B), suggesting that they arise from largely unstructured regions of the protein.

FIGURE 2.

The superposition of NMR spectra reveals the fold of FLNa(19). A, HSQC spectrum of FLNa(18–21) var-1 (red) overlaid on that of wild-type FLNa(18–21) (black) exhibits large differences between the two species. B, 1H-15N HSQC spectra with heteronuclear NOE applied (NOE “on” spectrum (+, red; −, blue) on top of NOE “off” spectrum (+, green; −, cyan)) show that the splicing variant of FLNa(18–21) contains many flexible regions. C, HSQC spectra of FLNa(19) (red) and FLNa(21) (yellow) are overlaid on the spectrum of FLNa(18–21) var-1 (black). D, there is no similarity at all between the HSQC of FLNa(19–20) var-1 (green) and that of FLNa(19) (red). The above experiments were carried out at pH 7.00, 37 °C, on a 950-MHz instrument (A), at pH 6.10, 25 °C, on a 600-MHz instrument (C and D), as well as pH 6.10, 25 °C, on a 750-MHz machine (B).

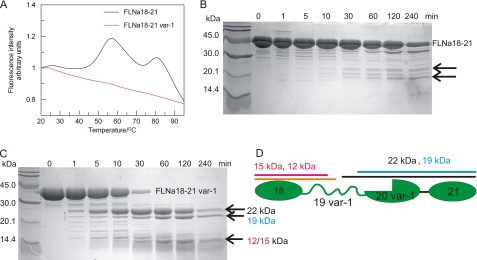

To complement the NMR analysis, biochemical tools were also used to assess the presence of unfolded parts in FLNa(18–21) var-1. Protein thermal stability assays were done using the ThermoFluor method (33), which can distinguish between folded and unfolded states of protein through the binding of a hydrophobic fluoroprobe. The probe is quenched in aqueous solution but preferentially binds to the exposed hydrophobic interior of a thermally unfolded protein. The binding is detected as fluorescence emission. The results showed that the melting curve of the canonical isoform FLNa(18–21) had two distinct peaks, whereas that of the corresponding var-1 was largely featureless (Fig. 3A), suggesting that var-1 is able to bind some dye even at ambient temperatures. This implies the presence of unfolded polypeptide segments in the variant isoform. Comparison of the melting curve of FLNa(18–21) with that of the domain pairs FLNa(18–19) and FLNa(20–21) allows assignment of the first peak at 55 °C to the unfolding of FLNa(20–21) and the second peak to the unfolding of FLNa(18–19) (supplemental Fig. S2). Single domains give featureless similar to variant isoform. The partially unstable nature of FLNa(21) has been reported earlier (21).

FIGURE 3.

Thermal stability and limited proteolysis assays of FLNa(18–21) and FLNa(18–21) var-1 support the unfolded nature of one domain. A, temperature denaturation profiles of FLNa(18–21) (black) and FLNa(18–21) var-1 (red) isoforms. B and C, limited proteolysis analysis of FLNa(18–21) (B) and FLNa(18–21) var-1 (C). Fragments that appeared upon α-chymotrypsin digestions are marked with arrows. D, schematic diagram of FLNa(18–21) var-1. The positions and approximate lengths of fragments formed in the limited proteolysis based on N-terminal sequencing analysis of FLNa(18–21) var-1 are marked.

The unfolded part was further mapped by limited proteolysis. Chymotrypsin readily digested FLNa(18–21) var-1 isoform to three fragments (22, 19, and 15 or 12 kDa), whereas FLNa(18–21) was only slowly digested to two fragments of different size (∼23 and 20 kDa; Fig. 3, B and C). The fragments formed upon digestion of the splice variant were analyzed using N-terminal sequencing. The largest fragment of 22 kDa corresponds to an amino acid sequence extending from the middle of unstructured FLNa(19) (from Thr2108) to the C terminus of FLNa(21) (Fig. 3, C and D). The next largest fragment of 19 kDa corresponds to a fragment extending from Tyr2081 to the C terminus of FLNa(21) (Fig. 3, C and D). The smallest band in the gel (Fig. 3C) is a fragment that extends from the N terminus of FLNa(18) approximately to the middle of FLNa(19). The exact position of the C terminus could not be determined. These results show that regions of FLNa(19) are more readily accessible to chymotrypsin in the var-1 isoform.

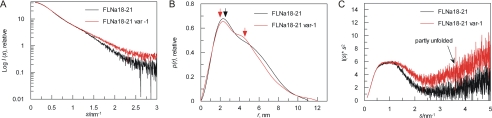

Model-independent Analysis of SAXS Data from FLNa(18–21) and FLNa(18–21) Var-1

To obtain more structural information about FLNa(18–21) and its spliced variant-1, SAXS data were collected. Both FLNa(18–21) and FLNa(18–21) var-1 behaved well in the experimental conditions used, with no detectable aggregation. The shapes of the scattering profiles (Fig. 4A) indicate that both fragments adopt an extended shape. Distance distribution functions p(r) of both nonspliced and spliced isoforms are highly asymmetric with maxima near 2 nm and tails extending to longer distances (Fig. 4B). The shape of the p(r) function of the splicing variant has an additional shoulder near 4.5 nm, giving the p(r) function a bimodal character, whereas the p(r) function of the canonical isoform is closer to a monomodal shape (Fig. 4B). The degree of compactness of both fragments was analyzed using Kratky plots (Fig. 4C). This shows that the splicing variant is partly flexible as the tail of the curve is upturned, consistent with NMR data. The Rg and Dmax for the FLNa(18–21) canonical isoform were calculated in a conventional way using Guinier and Gnom analyses. For the FLNa(18–21) fragment, Rg is 3.2 (±0.01) nm, and Dmax is 11 (±0.5) nm (Table 1), suggesting an almost linear organization of domains, because individual domain pairs had previously been shown to have values of Rg = 1.9–2.1 nm and Dmax = 6.1–6.5 nm (10).

FIGURE 4.

Model independent analysis of SAXS data. A, experimental scattering pattern of FLNa(18–21) (black) and FLNa(18–21) var-1 (red). The plot displays the logarithm of the scattering intensity I (arbitrary units) as a function of momentum transfer (s · nm−1). Same color convention is used for B and C. B, distance distribution function p(r) (arbitrary units) of FLNa(18–21) and FLNa(18–21) var-1 computed from x-ray scattering pattern with GNOM. The maxima in the p(r) functions are marked with arrows with similar colors as curves. C, Kratky plots (I(s)*s2) of FLNa(18–21) and FLNa(18–21) var-1. Curves are scaled to the same forward scattering intensity, I(0).

TABLE 1.

SAXS parameters of FLNa(18–21) and FLNa(18–21) var-1 with and without peptide

| FLN isoform | Peptide | Rg/nm | Dmax/nm |

|---|---|---|---|

| FLNa(18–21) | 3.2 ± 0.01a | 11 ± 0.5b | |

| FLNa(18–21) var-1 | 3.6c | 11c | |

| FLNa(18–21) | Migfilin 5–19 | 3.5c | 11c |

| FLNa(18–21) var-1 | Migfilin 5–19 | 3.6c | 11c |

a Calculated from Guinier analysis.

b Calculated from Gnom analysis.

c Average Rg/Dmax obtained from EOM analysis.

Model of FLNa(18–21) Based on SAXS and High Resolution Structures

Both ab initio shape reconstruction and rigid body modeling were employed to determine independently the overall low-resolution structures of the FLNa(18–21) isoform. The shape of FLNa(18–21) was first reconstructed from the experimental scattering curves alone using the program GASBOR (34), which represents the protein structure as a chain-like ensemble of dummy residues. The ab initio shape was obtained by calculating 20 independent models, which were then aligned, averaged, and filtered based on occupancy using DAMAVER (28). The individual models fitted the experimental data well with a discrepancy χ = 1.0–1.2. All independent models were similar because the mean normalized spatial discrepancy between the models was 1.0. The average of the most populated ab initio envelope demonstrates a planar, bent shape (Fig. 5A). The structural model was then build with SASREF (29) using the high resolution domain pair structures available for FLNa(18–21) (10, 11). The assumption that the domain pairs FLNa(18–19) and FLNa(20–21) are rigid bodies is supported by the known high resolution structures of FLNa(18–19) and FLNa(20–21) and the observation that the NMR HSQC spectra of domain pairs and the four-domain fragments are very similar (Fig. 2). The structural model obtained fitted the experimental scattering data very well (χ = 0.87, Fig. 5B). The model for FLNa(18–21) obtained in this way demonstrates that domain pairs are organized in an L shape with two arms at 90° to each other. Both arms consist of a domain pair (Fig. 5C). Apart from the covalent linkers between the domains, the model does not indicate any other stabilizing interactions between domains. The ab initio shape and structural model can also be superimposed nicely, revealing the excellent convergence of the two independent approaches (Fig. 5C, right). A similar L-shaped structure is seen in the solution structure of FLNa(19–21), where the domain 19 is, on average, at a 90° angle to domain 21 (supplemental Fig. S3). No significant flexibility was observed in the FLNa(18–21) fragment because when 30 rigid body models were calculated using SASREF (29), the root mean square deviation between Cα atoms only varied from 0 to 0.011 Å.

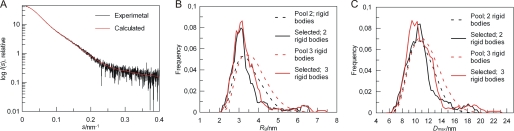

Ensemble Modeling of FLNa(18–21) Var-1 Based on SAXS and High Resolution Structures of Folded Domains

The lack of a defined three-dimensional structure for spliced FLNa(19) made analysis of the splicing variant less straightforward than that of nonspliced isoform. For a flexible protein like the splice variant, the Rg and Dmax values, determined from Guinier and Gnom analyses, do not correspond to a specific configuration but rather result from an average over different coexisting conformations in solution. Therefore, we used a recently developed EOM approach (27) to analyze the Rg and Dmax of the ensemble of splice variant conformers to produce an ensemble of structural models for FLNa(18–21) var-1. EOM treats the folded domains as rigid bodies and uses a genetic algorithm to select an ensemble of conformers that best agrees with the data from a large pool of models where the conformations of the flexible linkers are randomly varied. High resolution structures are available for FLNa(18–20) (with the first β-strand missing in the FLNa var-1 isoform), and FLNa(21) (10, 11). These can therefore be used as rigid bodies in EOM calculations. Two different combinations of rigid bodies were used: (i) three separate domains, FLNa(18), FLNa(20) splicing variant and FLNa(21) (referred to hereafter as three rigid bodies); or (ii) two separate rigid bodies, FLNa(18) and FLNa(20–21) splicing variant covalently linked and orientated as in FLNa(19–21) crystal structure (11) (referred to hereafter as two rigid bodies). The unfolded polypeptide chain, i.e. that corresponding the spliced FLNa(19), was modeled using both random-coil-like and native-like options, of which native-like models gave systematically better fit to experimental data. Using native-like modeling of unfolded polypeptide chain, several EOM runs yielded reproducible ensembles neatly fitting the experimental data with a discrepancy, χ, of approximately 0.80, with both two and three rigid body fits. A typical fit of the ensemble selected by EOM is shown in Fig. 6A. All the fits from different EOM runs were graphically indistinguishable. Reducing the number of conformers in the ensemble from 20 conformers to 1 changed the fit to experimental data; from χ = 0.8 to χ = 1.7, suggesting that FLNa(18–21) var-1 is flexible.

FIGURE 6.

EOM analysis of FLNa(18–21) var-1 SAXS data reveals weak interactions within FLNa(18–21) var-1 domain 19. A, typical fit obtained from the selected ensemble of structures (red) to experimental scattering curve (black). The logarithm of the scattering intensity I (arbitrary units) is plotted against to momentum transfer (s · nm−1). B and C, Rg (B) and Dmax (C) of the pools (dashed lines) versus selected structures (continuous lines). Three rigid bodies (three separate domains: FLNa(18), FLNa(20) var-1, and FLNa(21), red) and two rigid bodies (one domain, FLNa(18), and one domain pair FLNa(20) var-1-FLNa(21) orientated as in FLNa(19–21) crystal structure, black) are shown. The integral of the area defined by the histograms equals 1.

For the FLNa(18–21) var-1, the EOM method of analysis produced a skewed Rg distribution for the selected structural ensemble (Fig. 6B). A very similar Rg distribution was obtained with both sets of rigid bodies. The initial pool of FLNa(18–21) var-1 conformers with randomly generated intermolecular angles, gives a slightly broader range of Rg, extending to larger distances (Fig. 6B). Comparison of the Rg distribution of the initial pool and selected conformers shows that the selected distributions are biased toward a more compact structure, with a large peak at 3.6 nm and small bump near 6.5 nm, giving an average Rg of 3.6 nm (Table 1). The Dmax distribution shows similar trends, as the selected conformations are biased toward a more compact structure compared with the Dmax distribution seen with the initial pool, especially when 3 separate rigid bodies were used (Fig. 6C). The Dmax distributions of selected conformations have a large peaks near 10 nm (three rigid bodies) and 11 nm (two rigid bodies) and small bumps near 18 nm (Fig. 5C), resulting in an average Dmax values of 11 nm (Table 1). The bias toward compact structures suggests that weak interactions between amino acids in FLNa(19) exist although it lacks defined three-dimensional structure.

Although it is not possible to infer specific conformations from ensemble analysis, some conformers selected by EOM, when three separate rigid bodies were used, are shown in Fig. 7. Dmax and Rg distribution analyses (Fig. 6, B and C) show that the majority of conformers have Rg of approximately 3 nm and Dmax of approximately 9–11 nm. Fig. 7A shows two compact conformers (Dmax ∼9–10 nm), which, based on frequency analysis, are the most favored. Two less frequent conformers having extended conformations with Dmax ∼12–15 nm are shown in Fig. 7B. In the conformers shown in Fig. 7, A and B, the integrin and migfilin binding site at FLNa(21) is exposed. Because the first β-strand is missing in the spliced FLNa(20), it might also affect the relative orientation of spliced FLNa(20) and FLNa(21). One possibility, based on EOM modeling, is that CD face of FLNa(21) becomes masked by the spliced FLNa(20) (Fig. 7C). Very similar conformers with three rigid bodies was obtained when two separate rigid bodies were used (Fig. 7D).

Filamin Variant-1 Has Only One Integrin/Migfilin Binding Site

The major integrin and migfilin binding site is at FLNa(21). A secondary binding site is found in FLNa(19) (13, 15, 16, 35), which is unstructured in var-1. However, many intrinsically unfolded proteins undergo a transition to more ordered states or fold into stable secondary structures on binding to their targets, i.e. they undergo coupled folding and binding processes (36–38). Therefore, we wished to investigate whether this is also the case with spliced FLNa(19) in FLNa(18–21) var-1 when it binds to its binding partners, integrin or migfilin.

As demonstrated in our previous work (15), there are some characteristic and highly sensitive NMR peaks from a conserved serine in each domain (i.e. Ser2088 in FLNa(19) and Ser2279 in FLNa(21)) that can be used as indicators of the folding status of the domain and binding events. Focusing on these peaks (Fig. 8A), we found that the addition of cytoplasmic tail of β7 integrin did not induce folding of the spliced FLNa(19), because the characteristic Ser2088 peak from a folded form is not observed; in contrast, FLNa(21) in the splicing variant bound the cytoplasmic tail of β7 integrin in a similar way as observed previously in the nonsplice variant form of FLNa(21) (13, 21). This is consistent with FLNa(19) being unfolded in the var-1 form with a permanent loss of the secondary binding site for integrins in FLNa(19) (Fig. 8B).

FIGURE 8.

Presence of integrin ligand does not assist refolding of FLNa(19) var-1 in the splice variant. A, for 100 μm FLNa(19–21) var-1, 20-fold integrin peptide induced peak shifts in FLNa(21) but did not cause FLNa(19) to refold (free FLNa(19–21) var-1, red; integrin-bound, blue). The small spectral regions containing Ser2088 and Ser2279 are shown in expanded boxes to indicate of binding and folding (15, 21). The NMR experiments were performed at 25 °C, pH 6.10, on a 600-MHz instrument. B, the experiments suggest that FLNa(19) in FLNa(18–21) var1 loses its secondary integrin binding site and does not refold even with large excess of integrin ligands.

Binding assays were performed with the N-terminal fragment of migfilin (residues 5–19) to investigate whether FLNa(19) is able to bind migfilin. Migfilin was used as a binding partner instead of integrin because it is known to bind with higher affinity to FLNa(21) than the cytoplasmic tails of integrin (13–15, 35). Two mutations, I2092C and I2283C, which are known to block integrin binding to FLNa(19) (I2092C) and FLNa(21) (I2283C) (13, 15) were introduced to FLNa(18–21) var-1. Binding assays clearly show that migfilin binds only to FLNa(21) because migfilin binding to FLNa(18–21) var-1 mutant I2283C is notably much lower than to FLNa(18–21) var-1 I2092C (Fig. 9A). The Kd for migfilin binding to FLNa(18–21) var-1 I2092C is 13 ± 4 μm, which is very similar to the Kd for migfilin binding to isolated FLNa(21) (20 ± 7 μm; Fig. 9B). Reliable calculation of the binding affinity for migfilin interaction with FLNa(18–21) I2283C was not possible because saturation of binding could not be achieved.

Migfilin Binding Induces a Conformational Change in the FLNa(18–21) Structure

Previous structural and binding studies of isolated domain pairs (10, 11) showed that the migfilin and integrin binding sites in FLNa(19) and FLNa(21) are masked by the first β-strand from the preceding domain. Interestingly, despite the masking, migfilin is still able to bind to FLNa(18–21). The binding assays performed for FLNa(21), FLNa(18–21) WT and I2092C mutant show that the migfilin binding to an isolated FLNa(21) is only slightly stronger than in the context of four-domain fragment FLNa(18–21) WT or I2092C (Fig. 9B). The apparent Kd for migfilin binding to FLNa(21) is 20 ± 7 μm, whereas for FLNa(18–21) WT and for I2092C mutant Kd values are ∼40–60 μm. The binding seen with FLNa(18–21) WT can be assumed to result solely from binding to FLNa(21) because migfilin binding to isolated FLNa(19) is very weak (Fig. 9B). In other words, migfilin binds to FLNa(18–21) with strength similar to FLNa(21), suggesting that migfilin is able displace the masking β-strand. This was further studied by comparing the migfilin-induced chemical shift changes in Ser2279 and Trp2262 (supplemental Fig. S5). The spectra show that both of these peaks are in a similar position in FLNa(21) and FLNa(20–21) upon migfilin binding, whereas the original position was different in FLNa(20–21) because of interdomain masking. This kind of unmasking is expected to cause a detectable conformation change in the FLNa(18–21) fragment. This is consistent with the SAXS data for both FLNa(18–21) and FLNa(18–21) var-1 in the presence of the N-terminal fragment (residues 5–19) of migfilin. Analysis using the EOM method indicates that migfilin induces a small increase in the Rg value of FLNa(18–21) but not in the splice variant (Table 1 and supplemental Fig. S4). This suggests that the migflin peptide can displace the masking β-strand and bind to FLNa(21). No change in the Dmax values was observed within the accuracy limits of Dmax evaluation (Table 1 and supplementary Fig. S4). The Rg and Dmax values obtained from EOM analysis can be considered to be reliable because several EOM runs yielded reproducible ensembles that fitted the experimental data well, with discrepancy χ around 0.77 (FLNa(18–21)) and 0.80 (FLNa(18–21) var-1). Both Rg and Dmax distributions for FLNa(18–21) with migfilin peptide are broad, indicating some flexibility in the system (supplemental Fig. S4). Because the peptide-bound conformation of FLNa(18–21) is flexible, it is not possible to build one single model. In Fig. 9C, one member of the ensemble obtained for the peptide-bound from of FLNa(18–21) is shown. Whether the orientation of FLNa(20) and FLNa(21) with respect to each other is similar to the high resolution structure (11) is beyond the resolution of SAXS.

DISCUSSION

Here, we present the first structural characterization of the four-domain filamin fragment FLNa(18–21) and its splicing variant-1, which lacks the last β-strand of FLNa(19) and the first β-strand of FLNa(20) (41 residues in 2127–2167) (6). Our results show that in solution the domain pairs 18–19 and 20–21 are arranged roughly perpendicularly to each other. No interactions are seen between the domain pairs in the model. A similar perpendicular arrangement is seen in FLNa(19–21) solution structure. Interestingly, the solution conformations of FLNa(19–21) and FLNa(18–21) and the crystal conformation of FLNa(19–21) (11) seem to be different: in the x-ray structure FLNa(19) and FLNa(20) are in concatenated rather than perpendicular orientations to each other. Molecular dynamics simulations based on the crystal structure showed that these two domains can move in relation to each other (11), thus the FLNa(19–21) x-ray conformation may have been influenced by crystal contacts. An averaged conformation is observed in SAXS measurements, rather than a single conformation, so it is likely that, in solution, domains FLNa(19) and FLNA(18–19) can change their positions relative to FLNa(21). Although the FLNa(18–21) seems to form a rather compact structure, it is able to change its conformation upon binding to an interaction partner as seen in SAXS measurements with migfilin. Migfilin binding to FLNa(21) can displace the masking β-strand of FLNa(20). It is also possible that some unmasking of FLNa(19) can occur, although the binding assays suggest that this contributes less to overall migfilin binding. Based on these in vitro results, migfilin binding to FLN is possible without prior displacement of the masking β-strand. Whether a force-induced conformational change is needed in cells to expose the binding site (18) is not known. Potent migfilin binding sites other than domains 19 and 21 exists in whole length filamin, including domains 4, 9, 12, 17, and 23 (35). Of these, the binding sites at FLNa(17), FLNa(12), and FLNa(23) are not masked (10), but for domains 4 and 9 no structural information exists. In cells migfilin may bind to several filamin domains simultaneously, either by displacing the masking β-strand or by binding to the unmasked binding site. Despite the interesting ability of migfilin to bind to filamin and act as a regulator of integrins (15, 16), migfilin seems not to be essential for mouse development or for tissue homeostasis (39).

Alternative mRNA splicing causes significant changes of the FLNa var-1 structure compared with the nonspliced isoform. The spectral dispersion and the inversion of NMR peaks in a heteronuclear NOE experiment on FLNa(18–21) var-1 show that FLNa(19) is largely unfolded and flexible whereas other domains maintain the folds observed in the nonspliced variant. Thermal stability assays and limited chymotrypsin proteolysis, followed by N-terminal sequencing analysis, also confirmed the presence of unfolded regions in FLNa(19). Unfolding of one domain complicates structural studies due to the heterogeneity and rapid interconversion of different conformers. Useful structural methods are thus limited to those applicable in solution, such as SAXS and NMR. Here, we have applied SAXS to model FLNa(18–21) var-1 with an ensemble of conformers using the recently developed EOM method (27). Because FLNa(19) is flexible, FLNa(18–21) var-1 was represented by an ensemble of conformers. EOM analysis shows that both Dmax and Rg distributions of FLNa(18–21) var-1 are biased toward a more compact structure than would be estimated from randomly generated initial conformers. Thus, spliced FLNa(19) seems to mostly adopt conformations with some weak attractive interactions between amino acids. However, both Dmax and Rg distributions are rather broad extending from 2 to 4 nm (Rg) and from 7 to 14 nm (Dmax), implying that FLNa(18–21) var-1 can adopt various different conformers in solution. This is further supported by the fact that when the number of conformers in the ensemble was reduced from 20 to 1, the fit to experimental data deteriorated. The most highly populated conformers are, however, those having Rg of 3 nm and Dmax of 10–11 nm. A small population of extended conformations also exists, with Rg and Dmax of 6.5 nm and 18–19 nm, respectively. Comparison of the ensembles for the FLNa(18–21) splice variant-1 with the nonsplice variant shows that some compact conformers of FLNa(18–21) var-1 closely resemble the FLNa(18–21) structural model.

The biological function of FLNa var-1 form and the role of the unstructured FLNa(19) in that form remain to be clarified. More than 30% of proteins in eukaryotes have sequences of at least 50 residues long that encode unfolded proteins with a diverse range of functions (40–42). In the case of FLNa var-1 some functionality of FNLa19, e.g. interactions with binding partners integrin and migfilin, are lost because of the splice variant, but the interactions with some filamin ligands, such as integrin to FLNa(21), are enhanced probably because intramolecular masking effects are reduced when the 41 residues are deleted (11). Thus, it is possible that FLNa var-1 is expressed in situations where interactions of FLNa(21) need not be regulated e.g. by mechanical force. Although there are no data on the reduced stability of FLNa var-1 in vivo, we showed that in vitro it is more assessable to proteolysis. Thus, it is possible that in some cellular conditions the unstructured FLNa(19) would have shorter life time than the unspliced filamin isoform, thus providing a mechanism for regulating the abundance of var-1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Arja Mansikkaviita for excellent technical assistance and EMBL/DESY Hamburg for access to the beamline X-33.

This work was supported by Academy of Finland Grants 121393 (to U. P.) and 114713 (to J. Y.) and by the National Doctoral Programme in Informational and Structural Biology (to S. R.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S5.

- FLN

- filamin

- Dmax

- maximum dimension

- EOM

- ensemble optimization method

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single quantum correlation spectroscopy

- p(r)

- linear distance distribution function

- Rg

- radius of gyration

- SAXS

- small angle x-ray scattering.

REFERENCES

- 1. Feng Y., Walsh C. A. (2004) Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 1034–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Popowicz G. M., Schleicher M., Noegel A. A., Holak T. A. (2006) Trends Biochem. Sci. 31, 411–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stossel T. P., Condeelis J., Cooley L., Hartwig J. H., Noegel A., Schleicher M., Shapiro S. S. (2001) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 138–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhou X., Tian F., Sandzén J., Cao R., Flaberg E., Szekely L., Cao Y., Ohlsson C., Bergo M. O., Borén J., Akyürek L. M. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 3919–3924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhou A. X., Hartwig J. H., Akyürek L. M. (2010) Trends Cell Biol. 20, 113–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van der Flier A., Sonnenberg A. (2001) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1538, 99–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gorlin J. B., Yamin R., Egan S., Stewart M., Stossel T. P., Kwiatkowski D. J., Hartwig J. H. (1990) J. Cell Biol. 111, 1089–1105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pudas R., Kiema T. R., Butler P. J., Stewart M., Ylänne J. (2005) Structure 13, 111–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nakamura F., Osborn T. M., Hartemink C. A., Hartwig J. H., Stossel T. P. (2007) J. Cell Biol. 179, 1011–1025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Heikkinen O. K., Ruskamo S., Konarev P. V., Svergun D. I., Iivanainen T., Heikkinen S. M., Permi P., Koskela H., Kilpeläinen I., Ylänne J. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 25450–25458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lad Y., Kiema T., Jiang P., Pentikäinen O. T., Coles C. H., Campbell I. D., Calderwood D. A., Ylänne J. (2007) EMBO J. 26, 3993–4004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van der Flier A., Kuikman I., Kramer D., Geerts D., Kreft M., Takafuta T., Shapiro S. S., Sonnenberg A. (2002) J. Cell Biol. 156, 361–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kiema T., Lad Y., Jiang P., Oxley C. L., Baldassarre M., Wegener K. L., Campbell I. D., Ylänne J., Calderwood D. A. (2006) Mol. Cell 21, 337–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Takala H., Nurminen E., Nurmi S. M., Aatonen M., Strandin T., Takatalo M., Kiema T., Gahmberg C. G., Ylänne J., Fagerholm S. C. (2008) Blood 112, 1853–1862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lad Y., Jiang P., Ruskamo S., Harburger D. S., Ylänne J., Campbell I. D., Calderwood D. A. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 35154–35163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ithychanda S. S., Das M., Ma Y. Q., Ding K., Wang X., Gupta S., Wu C., Plow E. F., Qin J. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 4713–4722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen H. S., Kolahi K. S., Mofrad M. R. K. (2009) Biophys. J. 97, 3095–3104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pentikäinen U., Ylänne J. (2009) J. Mol. Biol. 393, 644–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xu W., Xie Z., Chung D. W., Davie E. W. (1998) Blood 92, 1268–1276 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Xie Z., Xu W., Davie E. W., Chung D. W. (1998) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 251, 914–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jiang P., Campbell I. D. (2008) Biochemistry 47, 11055–11061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G. W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., Bax A. (1995) J. Biomol. NMR 6, 277–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Laemmli U. K. (1970) Nature 227, 680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Matsudaira P. (1987) J. Biol. Chem. 262, 10035–10038 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roessle M. W., Klaering R., Ristau U., Robrahn B., Jahn D., Gehrmann T., Konarev P., Round A., Fiedler S., Hermes C., Svergun D. (2007) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, S190–194 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Svergun D. I. (1992) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 25, 495–503 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bernadó P., Mylonas E., Petoukhov M. V., Blackledge M., Svergun D. I. (2007) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 5656–5664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Volkov V. V., Svergun D. I. (2003) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 36, 860–864 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Petoukhov M. V., Svergun D. I. (2005) Biophys. J. 89, 1237–1250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wriggers W. (2010) Biophys. Rev. 2, 21–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. (1996) J. Mol. Graph. 14, 33–38, 27–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Merritt E. A., Bacon D. J. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 277, 505–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pantoliano M. W., Petrella E. C., Kwasnoski J. D., Lobanov V. S., Myslik J., Graf E., Carver T., Asel E., Springer B. A., Lane P., Salemme F. R. (2001) J. Biomol. Screen. 6, 429–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Svergun D. I., Petoukhov M. V., Koch M. H. (2001) Biophys. J. 80, 2946–2953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ithychanda S. S., Hsu D., Li H., Yan L., Liu D. D., Liu D., Das M., Plow E. F., Qin J. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 35113–35121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wright P. E., Dyson H. J. (1999) J. Mol. Biol. 293, 321–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Demchenko A. P. (2001) J. Mol. Recognit. 14, 42–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dyson H. J., Wright P. E. (2002) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 12, 54–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Moik D. V., Janbandhu V. C., Fässler R. (2011) J. Cell Sci. 124, 414–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dunker A. K., Lawson J. D., Brown C. J., Williams R. M., Romero P., Oh J. S., Oldfield C. J., Campen A. M., Ratliff C. M., Hipps K. W., Ausio J., Nissen M. S., Reeves R., Kang C., Kissinger C. R., Bailey R. W., Griswold M. D., Chiu W., Garner E. C., Obradovic Z. (2001) J. Mol. Graph. Model. 19, 26–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Uversky V. N. (2002) Protein Sci. 11, 739–756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Uversky V. N. (2002) Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 2–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Konarev P. V., Volkov V. V., Sokolova A. V., Koch M. H. J., Svergun D. I. (2003) J. Appl. Cryst. 36, 1277–1282 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.