Abstract

Objectives:

This pilot study explored the relationship between parental therapeutic alliance, maternal attachment style and child and family functioning in a sample of families with a child aged five to twelve years receiving child psychiatry day hospital treatment for complex co-morbid disorders.

Method:

Self-report measures of therapeutic alliance, maternal attachment style, child behaviour and family functioning were administered to parents at the end of the assessment period (T1) and at discharge (T2). The original study cohort included 90 families, and 44 families completed all the study measures at T2. Correlational analysis was conducted on these 44 families measuring parental alliance, maternal attachment style with child and family functioning scores. Comparisons were made between participants that completed T1 and T2 of the study with participants that only completed T1.

Results:

For the 44 families who completed both T1 and T2 measures, the combination of secure maternal attachment style and positive therapeutic alliance at T1 was associated with positive child outcomes, that is, improved scores on both the internalizing and externalizing dimensions as measured by the CBCL between T1 and T2. Significant changes were identified in family functioning with improvement on cohesion and expressiveness, enhanced intellectual-cultural orientation and improved family organization as measured by the FES.

Conclusions:

Capacity for secure attachment and positive alliance are associated with improved child and family systems outcomes in a high risk cohort of children with co-morbid disorders from a day and evening multimodal family treatment program.

Keywords: high risk children, family factors, attachment style, child multimodal treatment

Résumé

Objectifs:

Étudier la relation qui existe entre l’alliance thérapeutique parentale, le style d’attachement maternel et le fonctionnement de l’enfant et de la famille. L’échantillon était composé de familles ayant un enfant âgé de 5 à 12 ans qui suivait un traitement de jour en psychiatrie pour comorbidités complexes.

Méthodologie:

Les parents ont rempli un formulaire d’auto-évaluation portant sur l’alliance thérapeutique, sur le style d’attachement maternel et sur le fonctionnement familial, à la fin de l’évaluation (T1) et au moment du congé (T2). La cohorte initiale comptait 90 familles, mais seulement 44 d’entre elles ont terminé l’étude. Les scores relatifs à l’alliance parentale, au style d’attachement maternel et au fonctionnement de la famille et de l’enfant ont été mis en corrélation. Les auteurs ont comparé les mesures obtenues à la fin de l’évaluation et au moment du congé (T1 et T2) à celles obtenues à la fin de l’évaluation seulement (T1).

Résultats:

Les mesures recueillies en T1 et T2 auprès des 44 familles montrent qu’un attachement maternel sécurisant associé à une alliance thérapeutique positive en T1 donne des résultats positifs, c’est-à-dire que l’enfant a un score plus élevé aux échelles d’intériorisation et d’extériorisation lorsque le CBCL est administré entre T1 et T2. On constate une amélioration significative du fonctionnement de la famille au niveau de la cohésion, de l’expression, de l’orientation intellectuelle et culturelle, et de l’organisation familiale lorsque ces variables sont mesurées par le FES (Family Environmental Scale).

Conclusion:

Un attachement sécurisant et une alliance parents-enfant positive améliorent les résultats de l’enfant et de la famille lorsque l’enfant est suivi pour comorbidités complexes dans un programme de traitement familial mutimodal de jour et de soir.

Keywords: enfants à risque élevé, facteurs familiaux, style d’attachement, traitement multimodal, enfant

Introduction

Although there is recognition of the family’s crucial role in child development, there is little research on family-focussed approaches and indeed few intensive child treatment programs that integrate a multi-modal, family-focussed treatment. While psychiatric day hospital programs have been shown to be efficacious for high risk children with comorbid diagnoses (Grizenko, Sayegh, & Papineau, 1994; Northey, Wells, Silverman, & Bailey, 2003) there is little research exploring the specific family factors that may affect treatment outcomes. Family adversity has been linked to long term risk for psychiatric disorders (Green et al., 2010; McLaughlin et al., 2010; Raine, Brennan, Mednick, & Mednick, 1996). There is an urgent need for research to understand the specific family and individual variables that contribute to better outcomes in treatment of high risk children with comorbid psychiatric disorders (Pinsof & Wynne, 2007; Muran & Barber, 2010; Pinsof, Zinbarg, & Knobloch-Fedders, 2008).

Toupan and colleagues’ (Toupan, Yergeau, Dery, & Mercier, 2003) research with a day hospital cohort suggested that children with disruptive disorders have distinct family characteristics compared with same age children without these disorders. They found that children with disruptive disorders often are from less stable and cohesive families of lower socioeconomic status, with less social capital and under-developed social networks, change schools more often, and employ more punitive parental practices associated with less positive family relationships. Studying a similar child day hospital cohort, Guzder and colleagues (Guzder, Paris, Zelkowitz, & Feldman, 1999) identified the significant association of family factors such as physical and sexual abuse, parental neglect and severe parental pathology with the emergence of complex co-morbidity in childhood (including borderline pathology of childhood and neuro-psychological deficits). Some studies have highlighted how children with disruptive disorders may receive less affectionate family care (Cottrell & Boston, 2002; Kazdin & Wassell, 1999; Kazdin, 1997).

Parental or systemic interventions have been shown to have positive effects in reducing disruptive behaviour (Bell & McBride, 2010) and these effects are maintained and increase with time, in contrast to cognitive behavioural treatment that requires “booster sessions” to maintain change (Fonagy, Target, Cottrell, Phillips, & Kurtz, 2002). While systemic therapies have been widely used for high risk children and families (Cottrell & Boston, 2002), it is not clear from the literature what elements of treatment are essential for stable change of child behaviour, nor is it clear which shifts in family functioning are correlated with stable behavioural gains.

There is evidence to suggest that different modalities of successful treatment share similar mechanisms to effect change (Henggeler & Sheidow, 2002; Sprenkle & Blow, 2004). As a result, there has been a shift towards therapeutic integration with a focus on the therapeutic alliance as a key component of treatment technique and a determinant of therapeutic outcome (Lebow, 2003; Muran & Barber, 2010). While there is solid evidence supporting therapeutic alliance as a strong predictor of positive psychotherapeutic outcome in both individual and couple therapy (Cottrell & Boston, 2002; Estrada & Pinsof, 1995; Horvath & Bedi, 2002; Kazdin, 1997; Keller, Zoeller, & Feeny, 2010; Pinsof & Wynne, 1995, 2000; Pinsof et al., 2008), there is limited research on alliance formation as a predictor of child and family outcome in family-focussed child psychiatric treatment.

Bowlby (1988) conceptualized the therapeutic relationship as an attachment relationship and there is increasing evidence that understanding parental attachment capacity can increase our knowledge of alliance formation (Johnson, Ketering, Rohacs, & Brewer, 2006). Attachment theory (e.g., Ainsworth & Wittig, 1969; Ainsworth, Bell, & Stayton, 1974; Bowlby, 1958, 1969) has long been an essential construct for understanding the development of risk for child psychopathology. Insecure attachment between child and parent has been found to be associated with a wide range of negative child outcomes (Cicchetti, Toth, & Lynch, 1995; Solomon & George, 1999).

Although research in the last decade has examined client attachment and the working alliance in a variety of different settings (Diamond, Diamond, & Liddle, 2000; Eames & Roth, 2000; Satterfield & Lyddon, 1998; Marvin, 2003), only a handful of studies have explored the relationship between attachment security, therapeutic alliance, and therapeutic outcome in child and family therapy (Diamond, Siqueland, & Diamond, 2003; DiGiuseppe, Linscott, & Jilton, 1996; Johnson et al., 2006). Johnson and colleagues (2006) explored the link between attachment security and alliance formation in family therapy with an “at risk” cohort of mothers, fathers and their adolescent offspring showing that “mothers’ reports of trust in their oldest child predicted the alliance, while adolescent ratings of trust in parents moderated the relationship between therapy alliance and symptom distress” (p. 205). Diamond and colleagues (2003) developed an “attachment-based family therapy” for depressed adolescents that integrated an attachment framework for enhancing relational ruptures in alliance formation. DiGiuseppe and colleagues’ (1996) psychotherapy process research has explored multimodal strategies for alliance building in child and adolescent psychotherapy. These few studies highlight the complexity of alliance formation when treating families and their children with co-morbid disorders.

This pilot study examining the relationship between parental therapeutic alliance, maternal attachment style and child and family functioning, was based on the hypothesis that greater parental therapeutic alliance and secure maternal attachment style at the beginning of multimodal child psychiatry day or evening hospital treatment for children aged five to twelve, would be associated with more positive child and family outcomes. The first objective was to compare changes in child and family functioning from the outset of the treatment period (after the initial six-week assessment) (T1) to the end of treatment for participants who completed treatment and questionnaires (T2). A secondary objective was to explore the association of parental therapeutic alliance and maternal attachment styles with child and family outcomes.

Method

Participants

The child psychiatry family-oriented day and evening hospital programs offer a tertiary care service incorporating neuropsychological and psychoeducational testing in diagnostic and therapeutic planning. The day hospital setting provides a six-week global assessment by the multidisciplinary team of clinicians (psychiatrists, psychologists, occupational therapists, family therapists and special educators) prior to undertaking a commitment for longer-term treatment. Treatment averages an eight-month period. Children and their families were recruited from three Child Psychiatry Day or Evening Hospital programs. A total of 44 families completed all study measures at study intake (T1) and at treatment completion (T2).

Measures

The Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL) (Achenbach, Howell, Quay, & Connors, 1991) was used to assess externalizing (aggressive, undercontrolled, antisocial) and internalizing (fearful, inhibited, over controlled) symptoms. Studies have shown that the CBCL is able to discriminate clinical from non-clinical samples, has a test-retest reliability greater than 0.99 and an inter-rater reliability of 0.80 (Achenbach & McConaughy, 1997; Webster-Stratton & Lindsay, 1999).

The Family Environment Scale (FES) (Moos & Moos, 1976). This self-report measure assesses family interactions by assessing the family’s social environment. The short form consists of 40 true or false items that measure three dimensions: relationship, personal growth, and system maintenance. The internal consistency for the subscales ranges from 0.64 to 0.79 and the measure shows good stability over time. There is extensive evidence of the construct, concurrent, and predictive validity of FES subscales. In general, the FES subscales are associated with adjustment among family members of psychiatric patients, children’s cognitive and social development and other psychiatric and medical disorders (Moos, 1990).

The Working Alliance Scale-Short form (WAI) (Horvath & Greenberg, 1989; Tracey & Kokotovic, 1989) is a 12-item Likert scale that assesses three aspects of the working alliance: goal, task and bond. In initial validation studies, Horvath and Greenberg (1989) found that the WAI had excellent overall internal consistency estimates, good internal consistency estimates for the three subscales and good construct validity. Tracey and Kokotovic (1989) found that the measure assessed three separate aspects of the working alliance, as well as a secondary general construct of alliance which was used in this study.

The Relationship Questionnaire (RQ) (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991) was used to assess maternal attachment styles. Mothers were more available to complete study questionnaires, thus for study consistency only maternal attachment styles were collected. The RQ is a measure of attachment patterns, rated in terms of four styles as they apply to close adult peer relationships: secure, dismissing, preoccupied and fearful. Subjects are presented with four prototypical descriptions of the attachment styles and are asked to rate each prototype (on a 7-point Likert scale) in terms of how well each item fits their characteristic style in close relationships and to determine a categorical subject style or to obtain continuous ratings of attachment styles. Test re-test reliability (over an eight-month period) for each subscale varied from 0.49 to 0.71 (Scharfe & Bartholomew, 1994).

Procedures

Prior to study initiation ethics approval was received from the Hospital Ethics Committee. A research assistant explained the study, and obtained written informed consent. Treatment followed a multi-modal child psychiatry family-oriented treatment approach (Guzder et al., 1999) which includes weekly family therapy sessions, daily parental management input, child social skills training, occupational therapy, consultation on psychopharmacology and school-based interventions. At the end of a six-week global assessment period (T1), self-report measures of therapeutic alliance (WAI), maternal attachment style (RQ), child behaviour (CBCL) and family functioning (FES) were administered to the families. The same study measures were distributed at the end of treatment (T2) which varied between six months to one year following the initial assessment period.

Data analysis

To compare changes in child and family functioning from the beginning to the end of treatment, paired-sample t-tests were used to examine change on the measures between T1 and T2. To examine our hypothesis that stronger parental alliance and attachment security was associated with positive child and family outcomes at T2, we examined the correlations among these variables.

In order to further explore the association between maternal therapeutic alliance and maternal attachment styles, we decided to compare participants who completed questionnaires at T2 and participants who did not. Our assumption was that parents who completed the study measures endorsed a stronger therapeutic alliance, therefore had higher study compliance.

Chi-square statistics and Fisher’s exact test were used to determine whether any demographic variables distinguished between participants who completed both sets of study questionnaires (completers) and those who only completed T1 questionnaires (non-completers).

Results

Participants were 90 children (78 boys and 12 girls) and their families. The children ranged in age from 5 to 12 years (M=8.51, SD=1.50). Approximately half of the total sample were from two-parent families (48, [53%]) with the remainder in either single-parent families (28, [31%]) or other family forms, i.e., two-parent divorced (shared custody) (3.3%), foster families (1%) and a variety of other family structures. Complete results on all tests were available at T2 for 44 children and their families. The statistical analysis of results is based on this sample with a comparison of study completers and non-completers.

Child Outcomes

There was a significant improvement in child outcomes including both internalizing symptoms from (M=61.84 to 55.84), t (44) = 3.24, p = .002 and externalizing symptoms from (M +69.59 to 60.77), t (44) = 4.47, p < .001) between T1 and T2 (see Table 1).

Table 1.

CBCL internalizing and externalizing symptom scores for study completers (N=44)

| Time 1

|

Time 2

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Internalizing scores | 61.84 | 10.15 | 55.84 | 13.64 |

| Externalizing scores | 69.59 | 8.02 | 60.77 | 12.67 |

Family Functioning Outcomes

At treatment termination there was significant improvement of family functioning for participants who completed the study measures on a number of variables measured by the FES. Specifically, these families improved on Cohesion t (44) = − 2.2, p = .026, Expressiveness t (44) = − 2.48, p = .009, Intellectual-Cultural Orientation, t (44) = − 2.26, p = .004, and Organization t (44) = − 2.15, p = .054 (see Table 2). Results for the Conflict, Independence, Moral-religious emphasis and Control scales were non-significant.

Table 2.

FES subscale scores for study completers (N=44)

| Time 1

|

Time 2

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| FES Cohesion | 48.72 | 16.56 | 52.54 | 15.89 |

| FES Expressiveness | 46.97 | 13.39 | 51.25 | 13.42 |

| FES Conflict | 53.56 | 14.27 | 51.54 | 13.06 |

| FES Independence | 42.15 | 10.64 | 45.06 | 13.45 |

| FES Achiev orient | 47.06 | 11.47 | 46.18 | 11.03 |

| FES I-C Orient | 49.31 | 12.88 | 51.84 | 13.78 |

| FES Moral religious | 52.43 | 13.51 | 52.84 | 13.08 |

| FES Organization | 50.34 | 13.90 | 52.63 | 13.73 |

| FES Control | 56.81 | 11.88 | 57.09 | 12.74 |

Association between Parental, Maternal Attachment and Child and Family Outcomes

Our hypothesis that stronger parental alliance and attachment security was associated with positive child and family outcomes at T2 was not supported: All correlations between parental alliance, attachment and child and family outcomes were non-significant.

Attachment and Therapeutic Alliance

Findings revealed that the study completers had more secure attachments at T1 than non-completers t (74) = 2.25, p < .05. Results for the Relationship Questionnaire indicated that 70.5% of the mothers in our sample endorsed secure attachment style with their children compared with 45.5% of non-completers. Study completers endorsed more positive therapeutic alliances as reported on the WAI t (73) = 2.08, p < .05. In particular, study completers were more likely to agree to the statement on the WAI, “I believe the way we are working with my problem is correct.”

Study Completers by Family Income and Demographics

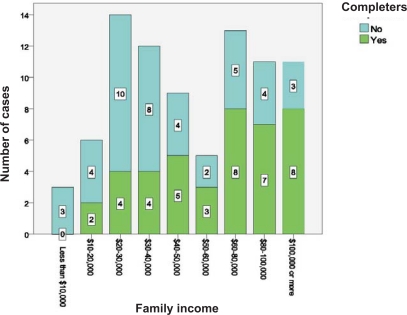

Several highly significant findings emerged. Completers were more likely to come from families with higher family income, χ2 (8, N = 84) = 11.62, p = .001. It was also found that completers were more likely to be in two-parent families (p < .02, Fisher’s exact test). This relationship is shown graphically in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study completers by family income

Discussion

We hypothesized that therapeutic alliance and secure attachment was associated with positive child and family outcomes as confirmed by the improvement in child and family functioning of our completed study cohort. However there was clearly significant attrition of our initial sample which is common in high risk sample cohorts (Johnson et al., 2006). Boyle et al. (Boyle, Offord, Racine, & Catlin, 1991), for similar reasoning, identified the greatest sample attrition among children with psychiatric disorders living in adverse family circumstances.

Our findings were consistent with the conclusions of Escudero and colleagues (Escudero, Friedlander, Varela, & Abascal, 2008) that identified a “shared sense of purpose was consistently associated with clients’ and therapists’ perceptions of therapeutic progress” (p. 194). Despite the lack of full support for our original hypothesis, this study was an attempt to redress a void in the literature on high-risk children and evaluation of family-based day treatment intervention through the exploration of alliance and attachment as mediating factors in child and family functioning. The families who completed the full set of measurements at T1 and T2 were more likely to be two-parent families with higher income. This finding is consistent with other child developmental studies where study completion was a key variable in improved outcome (Davidov & Grusec, 2006; Johnson et al., 2006). A similar finding was identified in Riekert & Drotar’s (1999) study of diabetic adolescents and their families where study non-completers had lower treatment adherence scores.

There are several limitations to consider when interpreting the results. First, the sample size is relatively small, and as a result there may not have been adequate power to test the hypotheses. There were missing data with over half the sample failing to complete study measures at T2 and impeding our capacity to draw definitive conclusions. This finding is consistent with many clinical studies where study attrition is an issue (Boyle et al., 1991; Johnson et al., 2006; Riekert & Drotar, 1999). Examining study completion is important as previous studies have indicated that study completion is correlated with better mental health outcomes at the end of treatment (Johnson et al., 2006; Miller & Wright, 1995). In Johnson and colleagues’ study (2006) of a similar high risk comorbid sample with multiple complex family stressors and family disorganization, 55% of mothers, 58% of fathers and 39% of adolescents dropped out of the study. A limitation of this study and this type of research in general is the fact that non-responders often score lower on most measures than responders. The T2 sample may therefore be skewed in favor of participants who tend to have a more secure attachment style and who are able to establish better therapeutic alliances. It is possible that therapeutic alliance (which has been shown to be related to attachment in previous studies) may be reflected in the willingness to complete the study. This bias in the data may be reducing our variance in terms of attachment and alliance, therefore hindering our chances of finding associations in an already limited sample.

For this pilot study we only investigated maternal attachment and therapeutic alliance at two points in time. To fully understand the impact of all family members on therapeutic outcome, it would be important to further explore the interaction of their attachment styles with alliance formation at different stages in the treatment process. This would allow for further investigation of the convergence between family member attachment styles, the capacity to sustain a therapeutic alliance over time and how this is associated with clinical outcome. Pinsof and colleagues’ (2008) seminal research on alliance formation in family therapy identified how split alliances can form when family members are differentially engaged in the treatment process, that is, when family members do not agree on their perceptions of the therapeutic alliance.

Conclusion

In this pilot study of a high-risk day and evening hospital sample, child outcomes revealed improved CBCL scores on both the internalizing and externalizing dimensions between T1 and T2. Significant changes were identified in family functioning of the completer cohort between T1 and T2 with improvement on specific scores of cohesion, expressiveness, enhanced intellectual-cultural orientation and improved family organization. Our results suggest that mothers with a secure attachment style, intact families and those with higher socioeconomic status, as well as those who develop a therapeutic alliance with the treating team, were more likely to complete the study measures. The complex interaction of attachment capacity, therapeutic alliance and child and family variables requires further study to distinguish the contribution of these factors to treatment outcome.

Table 3.

WAI subscale scores for study completers

| Time 1

|

N | Time 2

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||

| WAI Task | 22.54 | 4.97 | 44 | 21.84 | 6.00 |

| WAI Bond | 21.95 | 5.62 | 44 | 22.50 | 5.87 |

| WAI Goal | 6.42 | 4.06 | 44 | 6.74 | 4.42 |

Table 4.

Maternal Attachment Style based on RQ for study completers (N=44)

| Time 1

|

Time 2

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| 0 | 1 | 2.3 | 1 | 2.3 |

| Secure | 30 | 68.2 | 24 | 54.5 |

| Fearful | 7 | 15.9 | 9 | 20.5 |

| Preoccupied | 3 | 6.8 | 3 | 6.8 |

| Dismissing | 3 | 6.8 | 7 | 15.9 |

Acknowledgements / Conflicts of interest

Funded by Department of Psychiatry, Director’s Fund, Jewish General Hospital. Special acknowledgement to Dr. Sydney Duder for her assistance with statistical analysis. The authors have no financial relationship or conflicts to disclose.

References

- Achenbach TM, Howell CT, Quay HC, Conners CK. National survey of problems and competencies among four- to sixteen-year-olds: Parents’ reports for normative and clinical samples. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1991;56(3):1–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH. Empirically based assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology: Practical applications. 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS, Bell SM, Stayton D. Infant-mother attachment and social development. In: Richards MP, editor. The introduction of the child into a social world. London: Cambridge University Press; 1974. pp. 99–135. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS, Wittig BA. Attachment and the exploratory behaviour of one-year-olds in a strange situation. In: Foss BM, editor. Determinants of infant behaviour. Vol. 4. London: Methuen; 1969. pp. 113–136. [Google Scholar]

- Azima Cramer FJ, LaRoche C, Engelsmann F, Azima Heller R. Variables related to improvement in children in a therapeutic day center. International Journal of Therapeutic Communities. 1989;10:91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM. Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:226–244. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell C, McBride DF. Affect Regulation and Prevention of Risky Behaviors. Journal of American Medical Association. 2010;304(5):565–566. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle MH, Offord DR, Racine YA, Catlin G. Ontario child health follow-up study: Evaluation of sample loss. Journal of Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1991;30:449–456. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199105000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. The nature of the child’s tie to his mother. International Journal of Psychoanalysis. 1958;39:350–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Attachment. New York: Basic Books; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. New York: Basic Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL, Lynch M. Bowlby’s dream comes full circle: The application of attachment theory to risk and psychopathology. Advances in Child Psychology. 1995;17:1–75. [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell D, Boston P. Practitioner review: The effectiveness of systemic family therapy for children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;43(5):573–586. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidov M, Grusec JE. Untangling the links of parental responsiveness to distress and warmth to child outcomes. Child development. 2006;77:44–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond GM, Diamond GS, Liddle HA. The therapist-parent alliance in family-based intervention for adolescents. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2000;56:1037–1050. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(200008)56:8<1037::AID-JCLP4>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond G, Josephson A. Family-based treatment research: A 10-year update. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44:872–887. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000169010.96783.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond G, Siqueland L, Diamond GM. Attachment-based family therapy for depressed adolescents: Programmatic treatment development. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2003;6(2):107–127. doi: 10.1023/a:1023782510786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGiuseppe R, Linscott J, Jilton R. Developing the therapeutic alliance in child-adolescent psychotherapy. Applied and Preventative Psychology. 1996;5(2):85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Eames V, Roth A. Patient attachment orientation and early working alliance: A study of patient and therapist reports of alliance quality and ruptures. Journal of Psychotherapy Research. 2000;10:421–434. doi: 10.1093/ptr/10.4.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdman P, Caffery T. Attachment and Family Systems: Conceptual, Empirical, and Therapeutic Relatedness. New York: Brunner-Routledge; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Escudero V, Friedlander ML, Varela N, Abascal A. Observing the therapeutic alliance in family therapy: Associations with participant perceptions and therapeutic outcomes. The Journal of Family Therapy. 2008;30:194–214. [Google Scholar]

- Estrada A, Pinsof WM. The effectiveness of family therapies for selective behavioral disorders of childhood. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1995;21:403–440. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P, Target M, Cottrell D, Phillips J, Kurtz P. What works for whom: A clinical review of treatments for children and adolescents. New York: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Green JG, McLaughlin KA, Berglund PA, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication 1: Associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67(2):113–123. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grizenko N, Sayegh L, Papineau D. Predicting outcome in a multimodal treatment program for children with severe behavior problems. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;39:557–562. doi: 10.1177/070674379403900908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzder J, Paris J, Zelkowitz P, Feldman R. Psychological risk factors for borderline pathology in school aged children. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:206–212. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199902000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler S, Sheidow A. Conduct disorder and delinquency. In: Sprenkle D, editor. Effectiveness research in marriage and family therapy. Alexandria, VA: American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy; 2002. pp. 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath AO, Bedi RP. The alliance. In: Norcross JC, editor. Psychotherapy relationships that work: Therapists contributions and responsiveness to patients. New York: Oxford; 2002. pp. 37–69. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath AO, Greenberg L. Development and validation of the Working Alliance Inventory. Journal of Counselling Psychology. 1989;3:223–233. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson LN, Ketering SA, Rohacs J, Brewer AL. Attachment and therapeutic alliance in family therapy. The American Journal of Family Therapy. 2006;34:205–218. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Practitioner Review: Psychosocial treatments for conduct disorder in children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38:161–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Wassell G. Barriers to Treatment participation and therapeutic change among children referred for conduct disorder. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28(2):160–172. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2802_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Wassell G. Therapeutic changes in children, parents and families resulting from treatment of children with conduct problems. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:414–420. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200004000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Whitley MK. Treatment of parental stress to enhance therapeutic change amongst children referred for aggressive and antisocial behaviour. Journal of Counselling and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(3):504–515. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.3.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller SM, Zoeller LA, Feeny NC. Understanding factors associated with early therapeutic alliance in PTSD treatment: Adherence, childhood sexual abuse history, and social support. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010 doi: 10.1037/a0020758. Online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebow JL. Integrative approaches to couple and family therapy. In: Sexton T, Weeks G, Robbins M, editors. Handbook of family therapy: The science and practice of working with families and couples. New York: Brunner-Routledge; 2003. pp. 201–225. [Google Scholar]

- Marvin RS. Implications of attachment research for the field of family therapy. In: Erdman P, Caffery T, editors. Attachment and family systems: Conceptual, empirical, and therapeutic relatedness. New York: Brunner-Routledge; 2003. pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication II: Associations with persistence of DSM-IV disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67(2):124–132. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RB, Wright DW. Detecting and correcting attrition bias in longitudinal family research. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:921–929. [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH. Conceptual and empirical approaches to developing family-based assessment procedures: Resolving the case of the Family Environment Scale. Family Process. 1990;29:199–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1990.00199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Moos BS. A typology of family social environments. Family Process. 1976;15:357–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1976.00357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muran JC, Barber JP. Therapeutic alliance: An evidence-based guide to practice. New York: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Northey W, Wells K, Silverman W, Bailey C. Childhood behavioural and emotional disorders. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2003;29(4):523–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2003.tb01693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsof WM, Wynne LC. The efficacy of marital and family therapy: An empirical overview, conclusions, and recommendations. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1995;21(4):585–613. [Google Scholar]

- Pinsof WM, Wynne LC. Toward progress research: Closing the gap between family therapy research and practice. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2000;26(1):1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2000.tb00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsof WM, Wynne LC. The Efficacy of Marital and Family Therapy: An empirical overview, conclusions and recommendations. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2007;21(4):585–613. [Google Scholar]

- Pinsof WM, Zinbarg R, Knobloch-Fedders L. Factorial and construct validity of the revised short form integrative psychotherapy alliance scales for family, couple, and individual therapy. Family Process. 2008;47(3):281–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2008.00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine A, Brennan P, Mednick B, Mednick S. High rates of violence, crime, academic problems and behavioural problems in males with both early neuromotor deficits and unstable family environments. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:544–549. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830060090012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riekert KA, Drotar D. Who participates in research on adherence to treatment in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus? Implications and recommendations for research. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1999;24:253–258. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/24.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satterfield WA, Lyddon WJ. Client attachment and the working alliance. Counseling Psychology Quarterly. 1998;11:407–415. [Google Scholar]

- Scharfe E, Bartholomew K. Reliability and stability of adult attachment patterns. Personal Relationships. 1994;1:23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon J, George C. Attachment disorganisation. New York and London: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sprenkle DH, Blow AJ. Common factors and our sacred models. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2004;30(2):113–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2004.tb01228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toupan P, Yergeau D, Dery F, Mercier J. Enfants manifestant un trouble des conduits et utilisant des services psychoeducatifs: Un portrait social, familial et psychologique. Santé Mentale au Québec. 2003;28(1):232–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracey TJ, Kokotovic AM. Factor structure of the Working Alliance Inventory. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;1:207–210. [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C, Lindsay DW. Social competence and conduct problems in young children: Issues in assessment. Journal of Clinical and Child Psychology. 1999;28:25–43. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2801_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]