Abstract

Nitric oxide gas acts as a short-range signaling molecule in a vast array of important physiological processes, many of which include major changes in gene expression. How these genomic responses are induced, however, is poorly understood. Here, using genetic and chemical manipulations, we show that nitric oxide is produced in the Drosophila prothoracic gland, where it acts via the nuclear receptor ecdysone-induced protein 75 (E75), reversing its ability to interfere with its heterodimer partner, Drosophila hormone receptor 3 (DHR3). Manipulation of these interactions leads to gross alterations in feeding behavior, fat deposition, and developmental timing. These neuroendocrine interactions and consequences appear to be conserved in vertebrates.

Keywords: E75, DHR3, nitric oxide, Drosophila, metamorphosis, ecdysone, metabolism

In previous work, we showed that ecdysone-induced protein 75 (E75, also known as Eip75B; NR1D3) (Tweedie et al. 2009) contains heme constitutively bound to its ligand-binding domain (LBD), and that amino acids coordinately bound to the heme iron can be displaced in vitro by changes in redox state or the presence of nitric oxide (NO) gas (Pardee et al. 2004; Reinking et al. 2005; Marvin et al. 2009). In turn, these structural changes negate the ability of E75 to repress transcription and to reverse the positive transcriptional activity of its heterodimer partner, Drosophila hormone receptor 3 (DHR3; also known as DHR46, NR1F4) (Tweedie et al. 2009). Here, we look to see whether these interactions are relevant in vivo and, if so, what their roles are.

One of the best-characterized roles of E75 and DHR3 in vivo is within the nuclear receptor (NR) transcriptional hierarchy that controls, and responds to, the production of the metamorphosis-inducing hormone ecdysone (diagrammed in Supplemental Fig. 1A). Upon binding ecdysone, the ecdysone receptor (EcR) acts as a heterodimer with a second NR, ultraspiracle (USP), to activate transcription of DHR3 and the E75 isoform E75A (Koelle et al. 1991; Lam et al. 1997, 1999; White et al. 1997; Bialecki et al. 2002). DHR3 then promotes its own continued expression as well as that of the E75 splice variant E75B and the downstream NR gene βFtz-F1. βFTZ-F1, in turn, activates the expression of ecdysone synthetic enzyme genes (Lavorgna et al. 1993; Woodard et al. 1994; Broadus et al. 1999), resulting in another round of ecdysone production. The major site of larval ecdysone production is the prothoracic gland (PG) (diagrammed in Supplemental Fig. 1B). The PG is also a major site of NO synthase (Nos) expression (Wildemann and Bicker 1999). Hence, we looked to see whether E75 and NO are present and interactive in this tissue, with the hypothesis that activation of βFtz-F1 transcription by DHR3 requires inactivation of E75 isoforms by NO. As predicted, all of the above-listed genes are expressed in the PG toward the end of third instar development, and disruption of their expression or activity leads to molecular outcomes that are consistent with those previously found in vitro. These interactions in the PG result in systemic reprogramming of behavioral, metabolic, and chronobiological processes.

Results

NOS expression in the PG is required for βFTZ-F1 expression

To confirm that E75, DHR3, Nos, and Ftz-F1 are all coexpressed in the PG, we analyzed their mRNA and protein expression patterns. Supplemental Figure 1C shows that all four genes are highly up-regulated in the PG toward the end of third instar development, as is the production of NO. This is consistent with their proposed role in producing the late larval pulse of ecdysone (Supplemental Fig 1A).

As mutations in Nos are embryonic-lethal (Regulski et al. 2004), we initiated our analysis of NO function using a targeted RNAi approach to remove NO specifically within the PG. Transgenic flies carrying one of several different Nos RNAi knockdown constructs (UAS-Nos-RNAi) (Fig. 1A; Materials and Methods) were crossed to flies that express GAL4 in the PG (phantom-GAL4, Amnesiac-GAL4). All of the RNAi lines tested resulted in knockdown of the major NOS isoform expressed in the PG, although with varying efficiency (Fig. 1A,B). Likewise, they all resulted in similar phenotypic defects, with the severity of these phenotypes proportional to their effectiveness on NOS knockdown (data not shown). The Nos-RNAi line that results in >95% knockdown of NOS protein and NO product (UAS-Nos-RNAiIR-X) (Fig. 1A–C) was used for the majority of subsequent assays.

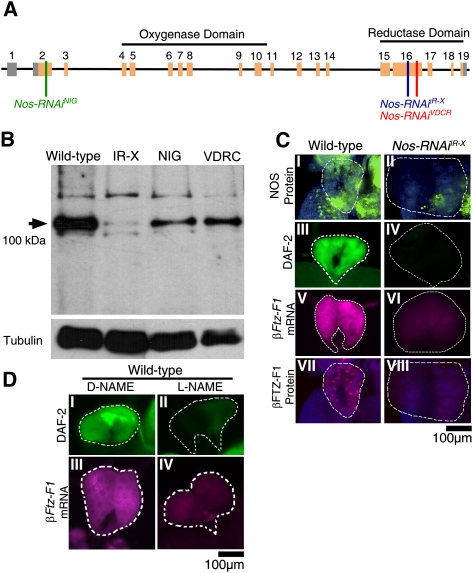

Figure 1.

NOS is required in the PG for NO production and Ftz-F1 expression. (A) Schematic diagram of Nos gene organization. Introns are depicted by horizontal black lines, and coding and noncoding exons are depicted by orange and gray boxes, respectively. The regions targeted by RNAi knockdown constructs are depicted by vertical lines. Constructs used include Nos-RNAiNIG (green), Nos-RNAiIR-X (blue), and Nos-RNAiVDRC (red) transgenes. (B) Western blot for NOS protein levels in Ring glands dissected from wild-type, Tub-GAL4>Nos-RNAiIR-X, phm-GAL4>NosVDRC, and phm-GAL4>NosNIG knockdown larvae. The arrowhead indicates the ∼100-kDa PG-specific NOS protein isoform. Tubulin loading controls are shown below. All phenotypic effects caused by these RNAi constructs were similar, but proportional in severity to their effectiveness on NOS protein knockdown. (C) Immunofluorescent detection of NOS protein (panels I,II), NO gas (depicted by DAF-2 DA fluorescence; panels III,IV), Ftz-F1 mRNA (panels V,VI), or FTZ-F1 protein staining (panels VII,VIII) shows that NO is required for expression in wild-type (left column) and Nos-RNAiIR-X (right column) PGs of clear gut larval. PGs are outlined by dashed white lines. (D) NO gas (depicted by DAF-2 DA fluorescence; panels I,II) or Ftz-F1 mRNA (panels III,IV) show Nos knockdown by the chemical inhibitor L-NAME (shown in the right column). Treatment with the L-NAME isomer D-NAME (shown in the left column) had no effect on NO or Ftz-F1 mRNA expression.

As predicted, Nos knockdown results in failure of the PGs to express the DHR3 target gene βFtz-F1 (Fig. 1C, panels V,VIII). The same result was achieved by disrupting NO production using the NOS enzymatic inhibitor L-NAME (Fig. 1D, panels II,IV). It is worth noting that these and all other genetic and chemical manipulations of the PG described below had no observed effects on PG cell viability or on nontarget gene expression over the course of treatments, observation, and subsequent differentiation.

Ectopic NOS reverses E75-mediated βFtz-F1 gene repression

In a reciprocal approach, we attempted to induce βFtz-F1 expression prematurely (8–12 h before pupariation) using a heat-inducible DHR3 transgene in the absence or presence of E75 and/or NOS. A constitutively active NOS isoform (mouse macrophage Nos [Nosmac]) was used to circumvent the need for NOS activation. Boosting the levels of DHR3 expression prematurely in the PGs of feeding larvae does indeed result in premature initiation of βFtz-F1 expression (Fig. 2A [panels II,IV], B). Conversely, premature expression of E75B (or E75A) (data not shown), either alone or together with DHR3, reverts levels of βFtz-F1 expression to below background levels (Fig. 2A [panels V,VI], B). As predicted, this repression is reversed by coexpression of Nosmac (Fig. 2A [panel VII], B). Thus, the overall levels of βFtz-F1 expression in the PG depend on the relative stoichiometries of DHR3, E75, and active NOS proteins. These responses observed in vivo are consistent with the direct interactions observed previously in vitro (Reinking et al. 2005).

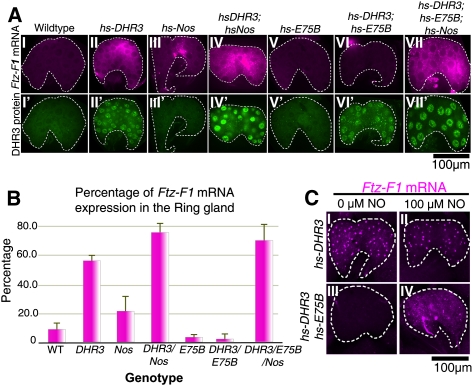

Figure 2.

NO reverses E75-mediated repression. (A) Wild-type (panel I), hs-DHR3 (panel II), hs-Nos (panel III), hs-DHR3; hs-Nos (panel IV), hs-E75B (panel V), hs-DHR3; hs-E75B (panel VI), and hs-DHR3; hs-E75B; hs-Nos (panel VII) PGs from blue gut larvae stained for Ftz-F1 mRNA (fuschia; top row) or DHR3 protein (green; bottom row) (see Supplemental Fig. 2 for E75 protein expression). PGs are outlined by dashed white lines. (B) Levels of Ftz-F1 mRNA detected by in situ hybridization in A were measured using NIH ImageJ (see the Materials and Methods), averaged, and plotted. Values are representative of several experiments. (C) Dissected PGs, cultured with (panels II,IV) or without (panels I,III) DETA-NO and expressing either DHR3 (panels I,II) or DHR3 and E75 (panels III,IV), show that NO blocks the repressive action of E75 on DHR3-mediated Ftz-F1 expression (shown in panel IV). Ftz-F1 mRNA in these PGs is largely nuclear (nascent at the sites of transcription) due to the short recovery time following induction, and possible effects of dissection and culturing.

E75-mediated βFtz-F1 repression can be reversed by NO gas

As an alternative means of providing NO, a variation of the experiment above was conducted using PGs dissected from larvae in which expression of DHR3 and E75B had again been induced prematurely, followed by treatment of these tissues in culture with the NO donor compounds DETA-NO or SNAP (data not shown). As seen in the previous experiment, PGs with prematurely expressed DHR3 also express βFtz-F1 prematurely (Fig. 2C, panels I,II), and coexpression of E75B reverses this induction (Fig. 2C, panel III). In the presence of NO donor, however, this E75-mediated repression is reversed (Fig. 2C, panel IV).

E75B-mediated repression of DHR3 activity is reversed by NO

Although the effects observed above on βFtz-F1 expression via modulation of E75, DHR3, and NO correspond with the direct interactions previously observed in vitro (Reinking et al. 2005), it could still be argued that the effects observed on βFtz-F1 in vivo may involve or require additional intermediary components. To address this, we visualized DHR3 activity in vivo using a fusion protein comprised of the LBD of DHR3 and the DNA-binding domain of GAL4, expressed together with a UAS-GFP reporter transgene (Fig. 3A). In previous work, we showed that GFP production induced by this fusion protein is repressed by E75 (Palanker et al. 2006). To see whether this E75-repressed activity can be restored by NO, we expressed Nosmac in larvae containing the DHR3 activity reporter system. As expected, the DHR3 fusion protein is active in PGs of wandering and prepupal larvae (Fig. 3B [panels I,II], C), and this activity is repressed by coexpression of E75B (Fig. 3B [panel III], C). As predicted, the E75-repressed activity is once again restored by coexpressing Nosmac (Fig. 3B [panel IV], C), consistent with NO affecting the ability of E75 to block DHR3 activity on target gene promoters.

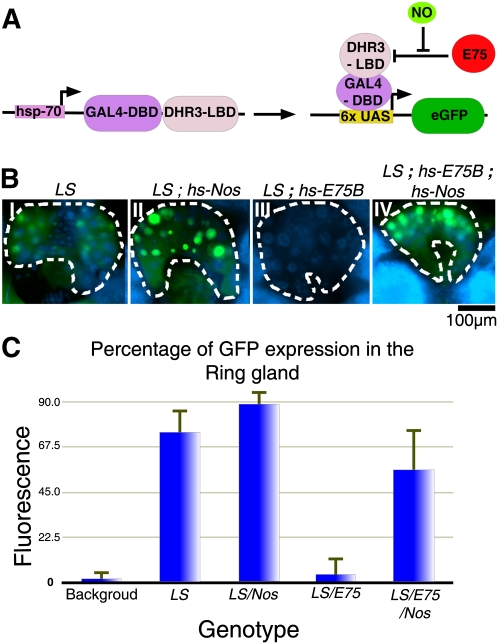

Figure 3.

Repression of DHR3 activity is reversed by NO. (A) Diagrammatic representation of the DHR3 “ligand sensor” (LS) system. The DHR3 LBD fused to the DNA-binding domain of yeast GAL4 (hs-GAL4::DHR3) is expressed together with a reporter expressing nuclear GFP under control of a UASGAL4 promoter. (B) GFP fluorescence (green) in the PGs of LS (panel I), LS; hs-Nos (panel II), LS; hsE75B (panel III), and LS; hs-E75B; hs-Nos (panel IV) transgenic larvae. Nuclei are costained with DAPI (blue). (C) Quantification of average fluorescence intensities measured using NIH ImageJ (see the Materials and Methods).

Down-regulation of NOS in the PG prevents the onset of metamorphosis

As these manipulations are expected to alter the efficacy and timing of ecdysone production, we monitored the sizes and numbers of manipulated larvae, pupae, and adults over their course of development. Wild-type larvae normally enter metamorphosis on the fifth day after egg laying (AEL), and begin to eclose as flies on the ninth day AEL (Fig. 4A). However, when NOS activity was knocked down, >80% of larvae failed to pupariate on time, continuing instead to feed until reaching a maximum size and weight 5–7 d after the normal time of metamorphosis (Figs. 4B, 5A, panel II). Some larvae continued to feed and wander for as long as 30–40 d. The relatively few larvae that initiated metamorphosis after day 5 exhibited obvious defects and failed to eclose. Similar results were obtained by feeding larvae with the NOS-specific chemical inhibitor L-NAME (Supplemental Fig. 3).

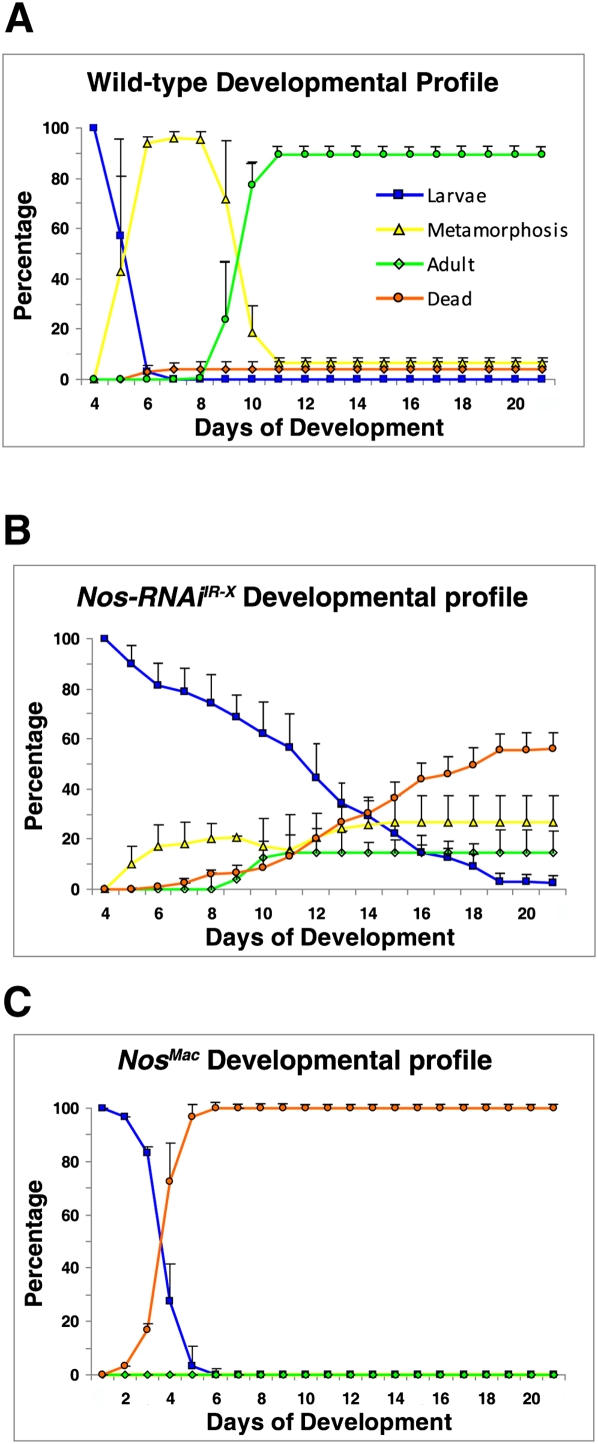

Figure 4.

NOS is required for the onset of pupariation. Developmental profiles for wild-type (A), phm-GAL4>Nos-RNAiIR-X (B), and phm-GAL4>Nosmac (C) animals followed for 21 d. Line colors (see inlay code in A) depict the relative numbers of larvae, pupae, flies, and dead animals on each day. Results are the average of triplicate data sets. Error bars depict standard deviation.

Figure 5.

DHR3 and E75 act epistatically to NOS. (A) Panel I shows a 5-d-old wild-type larva, and panels II–IV show 7- to 10-d-old UAS transgene larvae. phm-GAL4 was used to drive Nos-RNAiIR-X (panel II), E75A (panel III), DHR3-RNAi (panel IV), Nosmac (panel V), E75-RNAi (panel VI), or DHR3 (panel VII) expression. (B) Larvae carrying double transgenes: Nos-RNAiIR-X; DHR3-RNAi (panel I), Nos-RNAiIR-X; E75A (panel II), Nos-RNAiIR-X; DHR3 (panel III), and Nos-RNAiIR-X; E75-RNAi (panel IV).

Larvae in which constitutively active NOS was expressed prematurely in the PG under phm-GAL4 control exhibited the opposite phenotype, eating less, growing slowly, and failing to pass beyond the second instar (Figs. 4C, 5A, panel V), as determined by mouth–hook teeth numbers (Supplemental Fig. 4B). The majority of these larvae died by 5 d AEL.

These results are consistent with previous studies showing that the Nos gene is required for viability. A recent report, however, has suggested that the NOS gene can be deleted with no effects on viability (Yakubovich et al. 2010). In Supplemental Figure 6, we show that the deficiency produced in that study, which was intended to remove the N-terminal oxygenase domain, continues to produce normal levels of NOS and NO in the PG. Hence, the nature of the rearrangement produced in that study requires further investigation.

Ecdysone feeding rescues the developmental arrest of Nos-RNAi larvae

In past studies where ecdysone production was compromised (by alternate means), metamorphosis could be rescued by placing ecdysone in the food (Bialecki et al. 2002; Ono et al. 2006). Likewise, the majority of phm-GAL4>Nos-RNAiIR-X larvae initiated metamorphosis when their food was supplemented with ecdysone (Supplemental Fig. 5A,B), consistent with the Nos knockdown phenotype arising largely or wholly due to loss of ecdysone production.

NOS phenotypes are phenocopied by E75 and DHR3

To test whether NOS and NO act largely or exclusively via E75 and DHR3 in the PG, we looked to see whether genetic manipulations of E75 and DHR3 yield phenotypes similar to those produced by Nos manipulations. As predicted, larvae overexpressing E75A in the PG failed to pupariate on time, continuing to feed and grow (Fig. 5A, panel III). The same effect was achieved by reducing DHR3 in the PG via RNAi (Fig. 5A, panel IV). Conversely, decreasing the levels of E75 (A or B) or increasing the levels of DHR3 (Fig. 5A, panels VI,VII) yielded slow-growing larvae that did not pass the second instar, as observed with Nosmac larvae (Fig. 5A, panel V).

Another way to test whether the effects of NOS are mediated via E75—and, in turn, DHR3—is to test for genetic epistasis. Indeed, reducing PG expression of DHR3 or overexpressing E75A, in the Nos-RNAiIR-X background, leads to prolonged larval growth, as observed for each manipulation on its own (Fig. 5B, panels I,II). Conversely, DHR3 overexpression or E75 knockdown both suppress the Nos RNAi phenotype, producing small larvae (Fig. 5B, panels III,IV) as seen with the latter manipulations on their own. Together, these results indicate that E75 and DHR3 are the primary mediators of NO function in the PG.

Nos-RNAi larval overgrowth is not proportional

GAL4>Nos-RNAiIR-X larvae generally grow to ∼1.5 times their normal length, while GAL4>Nosmac larvae fail to grow beyond second instar size. To see whether these altered sizes are reflected by a general increase or decrease in the growth of all tissues, or in just a subset of tissues, we measured relative tissue sizes. Strikingly, the PGs of phm>Nos-RNAiIR-X larvae grow as much as six times their normal size, while the adjacent brain hemispheres show no relative change (Fig. 6A, panels I,II; Supplemental Fig. 7A,B). This growth is due to an increase in PG cell size (both cytoplasm and nuclei), not number. Also striking is the bright-red color that accumulates in proportion to final PG size (oxidizing to brown upon dissection) (Fig. 6A, panel II). The size of Nosmac PGs, on the other hand, was comparable with the size of wild-type second instar larval PGs, as were the ratios between PG and brain lobe diameters (Fig. 6A, panel III; Supplemental Fig. 7A,B). These results suggest that NOS activity is required to stop PG growth at the end of larval development, but has little effect before then.

Figure 6.

Effects of Nos manipulation on larval organs. (A) Brain–ring gland complexes of 5-d-old wild-type (panel I), 10-d-old Nos-RNAiIR-X (panel II), and Nosmac larvae (panel III). Ring glands are circled by black dashed lines. Bars, 100 μm. (B) Imaginal disc sizes from 5-d-old wild type (left) and 10-d-old Nos-RNAiIR-X (right). Bars, 50 μm. (C) Representative cells from fat body. White lines outline individual cells. Intracellular lipids are stained by Oil-Red-O (red). Wild-type (panel I), Nos-RNAiIR-X (panel II), and Nosmac (panel III) fat body tissue. Note that some vesicles are devoid of lipid (black arrow). Bars, 10 mm. (D) Average number of lipid droplets per fat cell (red bars). Error bars depict standard deviation. (E) Levels of total triacylglyceride larvae (red bar) and total protein (green bar) per larva in wild-type, Nos-RNAiIR-X, and Nosmac larvae. Error bars depict standard deviation.

Despite the fact that phm>Nos-RNAiIR-X larvae grow considerably larger than their wild-type counterparts, their CNS and imaginal discs remain the same size, with the same approximate numbers of cells (Fig. 6B; Supplemental Fig. 7B,C). However, fat bodies, which extend throughout most of the larva, are nearly two times their normal size (Fig. 6C, panel II; Supplemental Fig. 7D). Thus, much of the overall size change of Nos-RNAiIR-X larvae appears to be attributable to fat body, which already accounts for a significant amount of late third instar larval volume.

Conversely, the small size of phm>Nosmac larvae appears to be attributed to a decrease in the size of all tissues. As seen with the PG, other tissues in 5-d-old phm>Nosmac larvae are similar in size to those of 3-d-old wild-type second instar larvae (Supplemental Fig. 7A,B,D).

Reduction in NO results in a dramatic overaccumulation of lipids

Given the major changes observed in fat body size in Nos-RNAiIR-X larvae, we tested to see whether overall lipid content was affected. Consistent with the observed increase in fat body cell size, the number of cytoplasmic lipid vesicles is approximately sixfold higher, vesicle diameters are more than twofold higher, and Oil-Red-O staining is much stronger than wild-type controls (Fig. 6C, panel II). Remarkably, the levels of larval triacylgycerol (TAG), which is representative of overall lipid content, are ∼14-fold higher in Nos-RNAiIR-X 10-d-old larvae as compared with wild-type 5-d-old larvae. At the same time points, protein levels show no significant difference (Fig. 6E). Thus, it appears that the majority of the weight and size increase of Nos-RNAiIR-X larvae is due to increased storage of fat.

The opposite was observed in phm>Nosmac larvae. Although fat body size, in proportion to other tissues, does not appear to be much different, lipid vesicles are notably depleted of Oil-Red-O stain, and although protein levels are similar to second instar wild-type larvae, TAG levels are fourfold lower (Fig. 6C [panel III], E). Thus, NOS activity in the PG has major systemic effects on lipid metabolism and storage

Discussion

The E75 family of NRs function as nuclear NO targets in vivo

Although previously documented effects of NO on cells and tissues are numerous, and many of the cytoplasmic mechanisms of action are well documented, this is the first demonstration of a direct effect via a transcription factor in vivo. In the PG, our findings indicate that E75 is the major nuclear mediator of NO function, as evidenced by the similarity and epistatic nature of E75, DHR3, and NOS phenotypes. A review of the literature also shows that these genes tend to be coexpressed in many other Drosophila tissues, where limited analyses also suggest shared functions (Regulski and Tully 1995; Lam et al. 1997, 1999; White et al. 1997; Yamada et al. 2000; Bialecki et al. 2002; Regulski et al. 2004; Parvy et al. 2005; Reinking et al. 2005; Palanker et al. 2006; http://fly-fish.ccbr.utoronto.ca). Thus, the interactions described here are likely to be relevant to numerous other tissues and processes.

This overlap in expression and functions is also true for the vertebrate NOS and Rev-erb/ROR orthologs (Raspe et al. 2002a,b; Sato et al. 2004; Pardee et al. 2009; Jobgen et al. 2006; Kang et al. 2007; Hasegawa 2008; Duez and Staels 2009; Hollenberg and Cinel 2009; Jetten 2009; Mustafa et al. 2009). Examples of overlapping functions in vertebrates include their similar roles in lipid metabolism, gluconeogenesis, muscle differentiation, inflammation, circadian rhythm, PGC1α regulation, hypertension, and atherosclerosis. Strikingly, Nos triple-knockout mice that survive gestation are morbidly obese, exhibiting all aspects of metabolic syndrome (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, atherosclerosis), resulting in a maximum life span of 10 mo (Tsutsui et al. 2006, 2009). Conversely, NO up-regulation via arginine supplementation yields a reciprocal phenotype, which includes increased lipolysis, fatty acid oxidation, mitochondrial biogenesis, glucose metabolism, and life span (Jobgen et al. 2006; Ahmed et al. 2009; Mustafa et al. 2009). These effects are similar to those seen upon genetic manipulation of the Rev-erbs and RORs (Duez and Staels 2009; Duez et al. 2009).

In the case of E75, NO appears to act in two ways. As shown here and previously (Reinking et al. 2005), NO blocks the ability of E75 to interfere directly with DHR3-mediated transcriptional activation. However, it also appears to block the ability of E75 to repress target genes independently of DHR3 (Reinking et al. 2005). In vertebrates, no direct interaction has yet been observed between Rev-erbs and RORs. NO does, however, block the ability of the Rev-erbs to repress target genes by preventing the recruitment of coactivators (Pardee et al. 2009). We expect that this aspect of NO action is conserved in flies.

Activation of NOS activity

The achievement of critical weight at the end of the third larval instar coincides with a reduction in circulating levels of insulin-like peptides (ILPs) (Brogiolo et al. 2001; Rulifson et al. 2002) and consequential production of prothoracicotropic hormone (PTTH) peptide by neurons located within the larval brain (McBrayer et al. 2007). The axons of these PTTH-producing neurons extend to the surface of the PG, where binding of the secreted PTTH peptide to Torso receptor results in intracellular signaling (Rewitz et al. 2009). Intracellular outcomes include activation of Ras/Raf, MEK/Erk, and PKA (Rybczynski et al. 2001; Rybczynski and Gilbert 2006; Rewitz et al. 2009), and, notably, the production of Calmodulin, NADH, and cytoplasmic Ca2+ influx (Meller et al. 1988; Chen et al. 2001; Rybczynski and Gilbert 2003). The latter three molecules are required cofactors for dNOS enzymatic activity (Muller 1994; Regulski and Tully 1995; Stevens-Truss et al. 1997; Gribovskaja et al. 2005; Ray et al. 2007). Hence, we propose that PTTH acts, in large part, through NOS activation.

Autonomous effects of NO on PG size

The remarkable endoreduplication and growth of the PG due to loss of NOS expression is consistent with previous studies showing that NO has negative effects on cell growth (for reviews, see Villalobo 2006; Contestabile 2008). This activity has important implications and potential use in the control of oncogenic growth.

Interestingly, these effects of NO on PG size and the timing of metamorphosis contradict previous studies that had suggested that PG size is a key determinant of metamorphosis timing (Caldwell et al. 2005; Mirth et al. 2005). In these studies, metamorphosis appeared to occur when full PG size was achieved. Here, PG size was up to six times larger than normal, with no metamorphosis. Similarly, Colombani et al. (2005) found that altering PG size by manipulation of DMyc or Cyclin D expression could also increase PG size without triggering premature ecdysone production. Furthermore, metamorphosis can be induced prematurely by down-regulation of DHR4 without affecting PG size (Caldwell et al. 2005; Colombani et al. 2005; King-Jones et al. 2005). These seemingly contradictory results are likely due to cross-talk within the insulin and ecdysone signaling pathways.

The bright-red color of these enlarged PGs is consistent with previous studies suggesting that E75 and the Rev-erbs also function as heme sensors (Reinking et al. 2005; Yin et al. 2007).

Nonautonomous actions on lipid metabolism

NOS manipulation in the PG had major effects on lipid uptake and storage, leading to a nearly 20-fold increase in larval lipid content in the case of knockdown, or a nearly fivefold decrease when expressed prematurely. As disruption of EcR activity within fat body cells can also result in lipid overaccumulation (Colombani et al. 2005), the nonautonomous effects of PG NOS manipulation appear to be ecdysone-mediated. However, it is quite possible that the nearly 100-fold overall changes observed in lipid content may also be due to additional effects on feeding behavior, nutrient uptake, and other aspects of lipid metabolism.

The extended eating and fat deposition phenotype, caused by failure to produce ecdysone, may equate on many levels to processes underlying obesity and diabetes. Indeed, much as seen with Nos up-regulation, ecdysone supplementation in vertebrates results in decreased appetite, cholesterol synthesis, and weight gain, while at the same time increasing muscle mass and endurance (Lafont and Dinan 2003; Dinan and Lafont 2006; Kizelsztein et al. 2009). Given these apparent abilities to switch fat cell activity from lipid storage to lipid mobilization, a better understanding of the signals and mechanisms underlying NO and ecdysone-mediated effects should provide new insights and possible uses in metabolism based disorders.

Other conserved roles for NO and Rev-erbs in vertebrates

Given the previously demonstrated roles for NO, Rev-erbs, and RORs in the control of circadian clocks (Marletta 1993; Preitner et al. 2002; Golombek et al. 2004; Sato et al. 2004; Yin et al. 2006, 2007; Pardee et al. 2009; Rogers et al. 2008; Ahmed et al. 2009), and those shown here for developmental timing, it is quite possible that NO, Rev-erbs, and RORs also serve general roles in the matching of diurnal, lunar, and seasonal inputs (i.e., light, temperature, and food availability) with appropriate feeding behaviors, metabolism, and developmental progression. Disruption of these functions leads to metabolic, sleep, stress, immune, and hypertension disorders (Bose et al. 2009). Hence, further elucidation of ROR, Rev-erb, and NOS interactions in neuroendocrine tissues should provide new insights into how these temporal and metabolic processes are linked and coordinated, and new ways to prevent or treat their related disorders.

Materials and methods

Drosophila stocks

Wild-type flies used were Oregon-R. phantom-GAL4,UAS-mCD::GFP flies were provided by L. Riddiford; Amnc651-GAL4 were provided by M. Stern; hs-mouse-macrophage Nos (hs-Nosmac) was provided by G. Enikolopov; TubP-Gal4 were provided by the Bloomington Stock Center; UAS-DHR3, UAS-E75A, hs-DHR3, and hs-E75B lines were provided by C. Thummel; UAS-DHR3-RNAi and UAS-Nos-RNAiNIG were provided by the National Institute of Genetics in Japan; and UAS-E75A-RNAi and UAS-Nos-RNAiVDRC were provided by the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center.

Larval staging

Larvae were raised in standard food supplemented with 0.05% bromophenol blue, and were allowed to develop at 25°C under noncrowded conditions. The level and color of bromophenol blue inside the larval intestine on the morning of the fifth day of development was used for timing. Large feeding larvae with blue guts were deemed to be >8 h before puparium formation (BPF) (Andres and Thummel 1994). Wandering larvae with clear intestines were deemed to be 6–2 h BPF.

Developmental profiling

Eggs were collected in yeasted apple juice plates for 8 h at 25°C, transferred into aerated boxes containing standard food supplemented with 0.05% bromophenol blue, and allowed to develop to the third instar at 25°C. Four-day AEL wandering larvae with dark-blue guts were collected and transferred into smaller boxes containing standard food supplemented with 0.05% bromophenol blue, and their developmental profiles were recorded over 21 d at 25°C. For each cross, experiments were performed in triplicate.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry

Larvae were dissected in ice-cold Grace's insect medium (GIBCO) and fixed at room temperature for 20 min with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Larval samples were permeabilized with ice-cold acetone for 10 min at −20°C. Samples were washed twice for 5 min with PBS containing 0.02% Triton X-100 (PBST). Endogenous hydrogen peroxidase was inactivated by incubating samples with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min at 25°C. The rest of the larval in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry were performed according to Lecuyer et al. (2008).

DIG-UTP (Roche)-labeled antisense βFtz-F1 RNA probes were transcribed from a Ftz-F1 cDNA using multiple primers containing T7 or T3 promoter overhangs. Primers were designed to generate multiple short RNA probes to increase signal strength. Samples were incubated with peroxidase-IgG fraction monoclonal mouse anti-digoxygenin (1:500; Jackson Immunoresearch) and rabbit anti-DHR3 (1:100) (Lam et al. 1997) primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, and with Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (1:1000; Invitrogen) and TSA cyanine 3 tyramide (1:50; Perkin Elmer) secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. Samples were imaged using a Leica DMI6000B inverted-laser spinning-disk confocal microscope running Volocity 4.2 software (Improvision), and the Ftz-F1 mRNA signal was quantified using the quantitate function of NIH ImageJ to assess average pixel numbers and intensities within several equivalent-sized areas of imaged PGs.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed according to Lecuyer et al. (2008). Primary antibodies used were rabbit anti-E75A (1:100) (Hill et al. 1993), mouse anti-E75B MAb10E11 (1:20) (Schubiger and Truman 2000), rabbit anti-DHR3 (1:100) (Lam et al. 1997), mouse anti-dNOS1 MAb 6/57 (1:400) (Regulski et al. 2004), rabbit anti-βFTZ-F1 (1:10,000) (Murata et al. 1996), and rabbit anti-GFP Ab6556 (1:1000; Abcam). Secondary antibodies used were Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (1:1000; Invitrogen), Alexa Fluor 488 tyramide (1:50; Invitrogen), or TSA cyanine 3 tyramide (1:50; Perkin Elmer). Samples were imaged using a Leica DMI6000B inverted-laser spinning-disk confocal microscope running Volocity 4.2 software (Improvision).

DAF2-DA staining

Ring glands were dissected in PBS and incubated with 10 μM 4,5-diaminofluorescein diacetate (DAF2-DA, Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h at 25°C and either visualized immediately or fixed for 20 min in 1× PBS containing 5% paraformaldehyde and 0.2% Triton X-100 for later analysis. Stained tissues were imaged using a Leica DMRA2 upright stereomicroscope running Openlab 3.1.7 imaging software (Improvision).

Ectopic expression of DHR3, E75B, NOS2, and organ culture

Larvae carrying heat-inducible transgenes for DHR3, E75B, and/or Nos were heat-treated within sealed, yeasted, apple juice agar plates submerged for 40 min in a 37°C water bath. Larvae were allow to recover at 25°C for either 20 min for treatment with DETA-NO, SNAP, or DAF2-DA, or 60–120 min for whole-mount in situ hybridization or immunohistochemistry. For organ culture, dissected larval CNS and ring glands were cultured for 2 h at 25°C in Schneider's medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen), and 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin, and 0.25 mg/mL amphotericin B. NO production was achieved by adding freshly prepared DETA-NO (100 μM; Sigma Aldrich), L-NAME (10 μM; Sigma Aldrich), or SNAP (10 μM; Calbiochem) to the culture medium at the beginning of the incubation.

DHR3 ligand sensor activity

Five-day-old blue gut larvae carrying hs-GAL4-DHR3-LBD; UAS-EGFPnls (Palanker et al. 2006) and either hs-Nosmac, hs-E75B, or hs-E75B/hs-Nosmac transgenes were heat-treated for 35 min at 37°C and allowed to recover for 9 h at 25°C prior to ring gland dissection and GFP visualization. Average fluorescence intensities were quantified using the quantitate function of NIH ImageJ to assess average pixel numbers and intensities within several equivalent-sized areas of imaged PGs.

Triacylglyceride (TAG) and protein assays

Ten wandering third instar larvae per sample were homogenized in 250 μL of ice-cold PBS. Homogenates were heated for 5 min at 70°C and then centrifuged for 5 min at room temperature at 14,000 rpm. Supernatant was collected and stored at −20°C until needed or was used immediately. For determining total protein, 5 μL of supernatant was added to a 96-well flat-bottom tissue culture plate (Sarstedt) along with 200 μL of Bio-Rad protein reagent assay (catalog no. 500-0006). For determining total TAG levels, a LiquidColor Triglyceride kit (StandBio Laboratories) was used. Thirty microliters of supernatant or standard, along with 120 μL of TAG reagent, was loaded into each well. Once all samples were loaded, the 96-well plates were incubated for 5 min at 37°C, and readings at 500 nm (for TAG levels) and 595 nm (for protein levels) were taken in a spectrophotometer. Triplicates of each sample were averaged. Three independent assays were performed.

Lipid staining and analysis

Oil-Red-O staining was performed as described (Gutierrez et al. 2007), with minor modifications. Samples were fixed, stained with 0.01% Oil-Red-O in isopropanol, and rinsed in 1.5-mL Eppendorf tubes, and DAPI (1:1000; Molecular Probes) was added as a counterstain to the 1:1 glycerol:PBS mounting medium prior to mounting. Samples were visualized by DIC microscopy.

Protein extracts and Western blot analysis

Protein extracts for Western blot analyses were prepared from ring glands of 5-d-old third instar wandering larvae. Dissected ring glands were added immediately to 10 μL of cold protein loading buffer (5 M urea, 0.125 M Tris at pH 6.8, 4% SDS, 10% β-mercaptoethanol, 20% glycerol, 0.1% bromophenol blue) (Van Buskirk and Schupbach 2002). Five microliters of the lysate was loaded per lane onto an 8% SDS-PAGE gel. The blot was incubated with anti-DNOS1 primary MAb 6/57 (1:2000) (Regulski et al. 2004) overnight at 4°C, and then goat anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:10,000; Thermo Scientific) for 1 h at room temperature. Bands were visualized with Supersignal West Dura Extended Duration substrate (Thermo Scientific) and quantified using Adobe Photoshop CS2.

Detailed descriptions of probe synthesis, ecdysone feeding, L-NAME feeding experiments, and associated references are provided in the Supplemental Material.

Acknowledgments

We thank Louis Barbier for help in organ culture experiments; Helen McNeill, Meryl Nelson, and Ronit Wilk for helpful comments on the manuscript; Carl Thummel, Patrick O'Farrell, Lynn Riddiford, Michael Stern, Grigori Enikolopov, Michael Regulski, and Hitoshi Ueda for essential fly lines and antibodies; and Utpal Bannerjee for providing D-NAME. This work was funded by the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute. L.C. carried out the vast majority of the work shown and had substantial input in manuscript preparation. A.S.N. generated most of the lines, developed many of the assays, and obtained the first rounds of data. C.S. carried out the first analyses of NOS effects on life cycle and metabolic changes. S.K. generated the Nos-RNAiIR and Nosmac lines used in this study and noted the subsequent effects on life cycle and size. I.J.R. guided and supported the work of S.K. and provided the above-generated reagents and insight. H.M.K. conceptualized the majority of experiments undertaken and the writing of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available for this article.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.2064111.

References

- Ahmed ML, Ong KK, Dunger DB 2009. Childhood obesity and the timing of puberty. Trends Endocrinol Metab TEM 20: 237–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres AJ, Thummel CS 1994. Methods for quantitative analysis of transcription in larvae and prepupae. Methods Cell Biol 44: 565–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialecki M, Shilton A, Fichtenberg C, Segraves WA, Thummel CS 2002. Loss of the ecdysteroid-inducible E75A orphan nuclear receptor uncouples molting from metamorphosis in Drosophila. Dev Cell 3: 209–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose M, Olivan B, Laferrere B 2009. Stress and obesity: the role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in metabolic disease. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 16: 340–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadus J, McCabe JR, Endrizzi B, Thummel CS, Woodard CT 1999. The Drosophila βFTZ-F1 orphan nuclear receptor provides competence for stage-specific responses to the steroid hormone ecdysone. Mol Cell 3: 143–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brogiolo W, Stocker H, Ikeya T, Rintelen F, Fernandez R, Hafen E 2001. An evolutionarily conserved function of the Drosophila insulin receptor and insulin-like peptides in growth control. Curr Biol 11: 213–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell PE, Walkiewicz M, Stern M 2005. Ras activity in the Drosophila prothoracic gland regulates body size and developmental rate via ecdysone release. Curr Biol 15: 1785–1795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CH, Gu SH, Chow YS 2001. Adenylate cyclase in prothoracic glands during the last larval instar of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 31: 659–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombani J, Bianchini L, Layalle S, Pondeville E, Dauphin-Villemant C, Antoniewski C, Carre C, Noselli S, Leopold P 2005. Antagonistic actions of ecdysone and insulins determine final size in Drosophila. Science 310: 667–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contestabile A 2008. Regulation of transcription factors by nitric oxide in neurons and in neural-derived tumor cells. Prog Neurobiol 84: 317–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinan L, Lafont R 2006. Effects and applications of arthropod steroid hormones (ecdysteroids) in mammals. J Endocrinol 191: 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duez H, Staels B 2009. Rev-erb-α: an integrator of circadian rhythms and metabolism. J Appl Physiol 107: 1972–1980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duez H, Duhem C, Laitinen S, Patole PS, Abdelkarim M, Bois-Joyeux B, Danan JL, Staels B 2009. Inhibition of adipocyte differentiation by RORα. FEBS Lett 583: 2031–2036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golombek DA, Agostino PV, Plano SA, Ferreyra GA 2004. Signaling in the mammalian circadian clock: the NO/cGMP pathway. Neurochem Int 45: 929–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribovskaja I, Brownlow KC, Dennis SJ, Rosko AJ, Marletta MA, Stevens-Truss R 2005. Calcium-binding sites of calmodulin and electron transfer by inducible nitric oxide synthase. Biochemistry 44: 7593–7601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez E, Wiggins D, Fielding B, Gould AP 2007. Specialized hepatocyte-like cells regulate Drosophila lipid metabolism. Nature 445: 275–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa T 2008. SF1 mutation in humans. Growth Genet Horm 24: 1–5 [Google Scholar]

- Hill RJ, Segraves WA, Choi D, Underwood PA, Macavoy E 1993. The reaction with polytene chromosomes of antibodies raised against Drosophila E75A protein. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 23: 99–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenberg SM, Cinel I 2009. Bench-to-bedside review: nitric oxide in critical illness–update 2008. Crit Care 13: 218 doi: 10.1186/cc7706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jetten AM 2009. Retinoid-related orphan receptors (RORs): critical roles in development, immunity, circadian rhythm, and cellular metabolism. Nucl Recept Signal 7: e003 doi: 10.1621/nrs.07003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobgen WS, Fried SK, Fu WJ, Meininger CJ, Wu G 2006. Regulatory role for the arginine-nitric oxide pathway in metabolism of energy substrates. J Nutr Biochem 17: 571–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HS, Angers M, Beak JY, Wu X, Gimble JM, Wada T, Xie W, Collins JB, Grissom SF, Jetten AM 2007. Gene expression profiling reveals a regulatory role for RORα and RORγ in phase I and phase II metabolism. Physiol Genomics 31: 281–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King-Jones K, Charles JP, Lam G, Thummel CS 2005. The ecdysone-induced DHR4 orphan nuclear receptor coordinates growth and maturation in Drosophila. Cell 121: 773–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kizelsztein P, Govorko D, Komarnytsky S, Evans A, Wang Z, Cefalu WT, Raskin I 2009. 20-Hydroxyecdysone decreases weight and hyperglycemia in a diet-induced obesity mice model. Am J Physiol 296: E433–E439 doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90772.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelle MR, Talbot WS, Segraves WA, Bender MT, Cherbas P, Hogness DS 1991. The Drosophila EcR gene encodes an ecdysone receptor, a new member of the steroid receptor superfamily. Cell 67: 59–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafont R, Dinan L 2003. Practical uses for ecdysteroids in mammals including humans: an update. J Insect Sci 3: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam GT, Jiang C, Thummel CS 1997. Coordination of larval and prepupal gene expression by the DHR3 orphan receptor during Drosophila metamorphosis. Development 124: 1757–1769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam G, Hall BL, Bender M, Thummel CS 1999. DHR3 is required for the prepupal-pupal transition and differentiation of adult structures during Drosophila metamorphosis. Dev Biol 212: 204–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavorgna G, Karim FD, Thummel CS, Wu C 1993. Potential role for a FTZ-F1 steroid receptor superfamily member in the control of Drosophila metamorphosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 90: 3004–3008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecuyer E, Parthasarathy N, Krause HM 2008. Fluorescent in situ hybridization protocols in Drosophila embryos and tissues. Methods Mol Biol 420: 289–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marletta MA 1993. Nitric oxide synthase: function and mechanism. Adv Exp Med Biol 338: 281–284 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvin KA, Reinking JL, Lee AJ, Pardee K, Krause HM, Burstyn JN 2009. Nuclear receptors Homo sapiens Rev-erbβ and Drosophila melanogaster E75 are thiolate-ligated heme proteins which undergo redox-mediated ligand switching and bind CO and NO. Biochemistry 48: 7056–7071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBrayer Z, Ono H, Shimell M, Parvy JP, Beckstead RB, Warren JT, Thummel CS, Dauphin-Villemant C, Gilbert LI, O'Connor MB 2007. Prothoracicotropic hormone regulates developmental timing and body size in Drosophila. Dev Cell 13: 857–871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meller VH, Combest WL, Smith WA, Gilbert LI 1988. A calmodulin-sensitive adenylate cyclase in the prothoracic glands of the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta. Mol Cell Endocrinol 59: 67–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirth C, Truman JW, Riddiford LM 2005. The role of the prothoracic gland in determining critical weight for metamorphosis in Drosophila melanogaster. Curr Biol 15: 1796–1807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller U 1994. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent nitric oxide synthase in Apis mellifera and Drosophila melanogaster. Eur J Neurosci 6: 1362–1370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata T, Kageyama Y, Hirose S, Ueda H 1996. Regulation of the EDG84A gene by FTZ-F1 during metamorphosis in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Biol 16: 6509–6515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa AK, Gadalla MM, Snyder SH 2009. Signaling by gasotransmitters. Sci Signal 2: re2 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.268re2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono H, Rewitz KF, Shinoda T, Itoyama K, Petryk A, Rybczynski R, Jarcho M, Warren JT, Marques G, Shimell MJ, et al. 2006. Spook and Spookier code for stage-specific components of the ecdysone biosynthetic pathway in Diptera. Dev Biol 298: 555–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palanker L, Necakov AS, Sampson HM, Ni R, Hu C, Thummel CS, Krause HM 2006. Dynamic regulation of Drosophila nuclear receptor activity in vivo. Development 133: 3549–3562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardee K, Reinking J, Krause H 2004. Nuclear hormone receptors, metabolism, and aging: what goes around comes around.Transcription factors link lipid metabolism and aging-related processes. Sci Aging Knowledge Environ 2004: re8 doi: 10.1126/sageke.2004.47.re8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardee KI, Xu X, Reinking J, Schuetz A, Dong A, Liu S, Zhang R, Tiefenbach J, Lajoie G, Plotnikov AN, et al. 2009. The structural basis of gas-responsive transcription by the human nuclear hormone receptor REV-ERBβ. PLoS Biol 7: e1000043 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvy JP, Blais C, Bernard F, Warren JT, Petryk A, Gilbert LI, O'Connor MB, Dauphin-Villemant C 2005. A role for βFTZ-F1 in regulating ecdysteroid titers during post-embryonic development in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol 282: 84–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preitner N, Damiola F, Lopez-Molina L, Zakany J, Duboule D, Albrecht U, Schibler U 2002. The orphan nuclear receptor REV-ERBα controls circadian transcription within the positive limb of the mammalian circadian oscillator. Cell 110: 251–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raspe E, Duez H, Mansen A, Fontaine C, Fievet C, Fruchart JC, Vennstrom B, Staels B 2002a. Identification of Rev-erbα as a physiological repressor of apoC-III gene transcription. J Lipid Res 43: 2172–2179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raspe E, Mautino G, Duval C, Fontaine C, Duez H, Barbier O, Monte D, Fruchart J, Fruchart JC, Staels B 2002b. Transcriptional regulation of human Rev-erbα gene expression by the orphan nuclear receptor retinoic acid-related orphan receptor α. J Biol Chem 277: 49275–49281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray SS, Sengupta R, Tiso M, Haque MM, Sahoo R, Konas DW, Aulak K, Regulski M, Tully T, Stuehr DJ, et al. 2007. Reductase domain of Drosophila melanogaster nitric-oxide synthase: redox transformations, regulation, and similarity to mammalian homologues. Biochemistry 46: 11865–11873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regulski M, Tully T 1995. Molecular and biochemical characterization of dNOS: a Drosophila Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent nitric oxide synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci 92: 9072–9076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regulski M, Stasiv Y, Tully T, Enikolopov G 2004. Essential function of nitric oxide synthase in Drosophila. Curr Biol 14: R881–R882 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinking J, Lam MM, Pardee K, Sampson HM, Liu S, Yang P, Williams S, White W, Lajoie G, Edwards A, et al. 2005. The Drosophila nuclear receptor e75 contains heme and is gas responsive. Cell 122: 195–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rewitz KF, Yamanaka N, Gilbert LI, O'Connor MB 2009. The insect neuropeptide PTTH activates receptor tyrosine kinase torso to initiate metamorphosis. Science 326: 1403–1405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers PM, Ying L, Burris TP 2008. Relationship between circadian oscillations of Rev-erbα expression and intracellular levels of its ligand, heme. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 368: 955–958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rulifson EJ, Kim SK, Nusse R 2002. Ablation of insulin-producing neurons in flies: growth and diabetic phenotypes. Science 296: 1118–1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybczynski R, Gilbert LI 2003. Prothoracicotropic hormone stimulated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) activity: the changing roles of Ca2+- and cAMP-dependent mechanisms in the insect prothoracic glands during metamorphosis. Mol Cell Endocrinol 205: 159–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybczynski R, Gilbert LI 2006. Protein kinase C modulates ecdysteroidogenesis in the prothoracic gland of the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta. Mol Cell Endocrinol 251: 78–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybczynski R, Bell SC, Gilbert LI 2001. Activation of an extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) by the insect prothoracicotropic hormone. Mol Cell Endocrinol 184: 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato TK, Panda S, Miraglia LJ, Reyes TM, Rudic RD, McNamara P, Naik KA, FitzGerald GA, Kay SA, Hogenesch JB 2004. A functional genomics strategy reveals Rora as a component of the mammalian circadian clock. Neuron 43: 527–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubiger M, Truman JW 2000. The RXR ortholog USP suppresses early metamorphic processes in Drosophila in the absence of ecdysteroids. Development 127: 1151–1159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens-Truss R, Beckingham K, Marletta MA 1997. Calcium binding sites of calmodulin and electron transfer by neuronal nitric oxide synthase. Biochemistry 36: 12337–12345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsui M, Shimokawa H, Morishita T, Nakashima Y, Yanagihara N 2006. Development of genetically engineered mice lacking all three nitric oxide synthases. J Pharmacol Sci 102: 147–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsui M, Shimokawa H, Otsuji Y, Ueta Y, Sasaguri Y, Yanagihara N 2009. Nitric oxide synthases and cardiovascular diseases: insights from genetically modified mice. Circ J 73: 986–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tweedie S, Ashburner M, Falls K, Leyland P, McQuilton P, Marygold S, Millburn G, Osumi-Sutherland D, Schroeder A, Seal R, et al. 2009. FlyBase: enhancing Drosophila Gene Ontology annotations. Nucleic Acids Res 37: D555–D559 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Buskirk C, Schupbach T 2002. Half pint regulates alternative splice site selection in Drosophila. Dev Cell 2: 343–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villalobo A 2006. Nitric oxide and cell proliferation. FEBS J 273: 2329–2344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White KP, Hurban P, Watanabe T, Hogness DS 1997. Coordination of Drosophila metamorphosis by two ecdysone-induced nuclear receptors. Science 276: 114–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildemann B, Bicker G 1999. Developmental expression of nitric oxide/cyclic GMP synthesizing cells in the nervous system of Drosophila melanogaster. J Neurobiol 38: 1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodard CT, Baehrecke EH, Thummel CS 1994. A molecular mechanism for the stage specificity of the Drosophila prepupal genetic response to ecdysone. Cell 79: 607–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakubovich N, Silva EA, O'Farrell PH 2010. Nitric oxide synthase is not essential for Drosophila development. Curr Biol 20: R141–R142 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada M, Murata T, Hirose S, Lavorgna G, Suzuki E, Ueda H 2000. Temporally restricted expression of transcription factor βFTZ-F1: significance for embryogenesis, molting and metamorphosis in Drosophila melanogaster. Development 127: 5083–5092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin L, Wang J, Klein PS, Lazar MA 2006. Nuclear receptor Rev-erbα is a critical lithium-sensitive component of the circadian clock. Science 311: 1002–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin L, Wu N, Curtin JC, Qatanani M, Szwergold NR, Reid RA, Waitt GM, Parks DJ, Pearce KH, Wisely GB, et al. 2007. Rev-erbα, a heme sensor that coordinates metabolic and circadian pathways. Science 318: 1786–1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]