Abstract

Anti-cholinergic agents are used in the treatment of several pathological conditions. Therapy regimens aimed at up-regulating cholinergic functions, such as treatment with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, are also currently prescribed. It is now known that not only is there a neuronal cholinergic system but also a non-neuronal cholinergic system in various parts of the body. Therefore, interference with the effects of acetylcholine (ACh) brought about by the local production and release of ACh should also be considered. Locally produced ACh may have proliferative, angiogenic, wound-healing, and immunomodulatory functions. Interestingly, cholinergic stimulation may lead to anti-inflammatory effects. Within this review, new findings for the locomotor system of a more widespread non-neuronal cholinergic system than previously expected will be discussed in relation to possible new treatment strategies. The conditions discussed are painful and degenerative tendon disease (tendinopathy/tendinosis), rheumatoid arthritis, and osteoarthritis.

Key words: acetylcholine, tendinosis, tendinopathy, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis.

New aspects on the usefulness of interference with acetylcholine effects: basis for the present review

Medications interfering with the effects of acetylcholine (ACh) are frequently used today. Anti-cholinergic agents are widely used in the management of overactive urinary bladder and of obstructive lung disease. However, treatments leading to the upregulation of cholinergic activity are increasingly applied. New possibilities for interference with cholinergic effects are currently discussed. This is related to the existence of a widespread non-neuronal cholinergic system.

The present review summarizes hitherto known aspects of possible treatment strategies concerning interference with cholinergic effects. That includes inflammation in general, cancer, and pain conditions. However, major focus is devoted to discussions concerning conditions afflicting the locomotor system and for which a non-neuronal cholinergic system has been recently shown to exist. More specifically, the conditions discussed are rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and osteoarthritis (OA), and chronically painful tendons (tendinopathy) with degenerative-like tissue changes (tendinosis). Tendinopathy is a condition in which there is chronic pain in a tender portion of the tendon. The tendons most frequently affected are the Achilles and patellar tendons. When, in addition to chronic pain, there are structural tissue changes of a degenerative-like nature, as seen by ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or by histological examination, the condition is called tendinosis. In the following text, our recent observations concerning Achilles and patellar tendinosis will be discussed. Nothing at all has been previously known concerning the existence of a non-neuronal cholinergic system in tendinosis or the synovial tissue of patients with RA or OA. The current review will, therefore, give new directions concerning the cholinergic system in these conditions.

Acetylcholine production and acetylcholine receptors

ACh was the first neurotransmitter to be identified. It is synthesized from choline and acetyl-CoA via the activity of choline acetyltransferase (ChAT).1,2 In addition to production via ChAT, ACh can be produced by carnitine acetyltransferase (CarAT). ACh is then transferred to synpatic vesicles by vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT).3 ACh is degraded by cholinesterases.4 It is converted into the inactive metabolites choline and acetate by acetylcholinesterase (AChE). It is well known that the effects of ACh are mediated via muscarinic (G-protein coupled) and nicotinic (ligand-gated ion channels) ACh receptors.5 The muscarinic ACh receptors (mAChRs) are metabotrophic, and are stimulated by muscarine and ACh, whilst the nicotinic ACh receptors are ionotrophic receptors stimulated by nicotine and ACh. Muscarine is an alkaloid extracted from certain mushrooms, and nicotine is an alkaloid substance found in tobacco. Five subtypes of mAChRs have been identified (M1–M5), each with different functions and properties.6 Certain features regarding the expression patterns of the mAChRs in regions outside the central nervous system are well known, including the fact that the M2 receptor subtype comprises more than 90% of the mAChRs in the heart.7 The main ACh receptor in the smooth muscle of the gastrointestinal tract is the M2 receptor.8 The mAChRs associated with smooth muscle cells are predominantly of the M2 and M3 subtypes. The nicotinic receptors (nAChRs) are pentameric complexes consisting of a large number of different alpha-and beta-subunits.9 The various nAChRs have different physiological functions. The best-characterized nAChR, which, due to its relationship to immune functions, is further discussed below, is the α7nAChR.

There are both neuronal and non-neuronal cholinergic systems

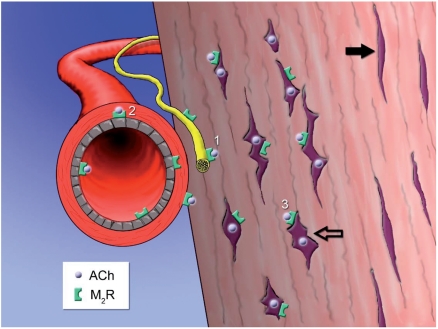

ACh is a neurotransmitter in the central, as well as in the peripheral, nervous system. It is a major transmitter in the autonomic nervous system, the principal transmitter of the parasympathetic part of this system, and a neurotransmitter in all autonomic ganglia. On the other hand, nerve-related reactions for ChAT or CarAT have, to the best of our knowledge, not been shown in synovial tissues of joints or for tendon tissue. It is well known that ACh synthesis is not only restricted to neurons; there is also a non-neuronal cholinergic system. Accordingly, ACh is produced in surface epithelia, such as those of the airways10 and the intestine.11,12 Furthermore, the keratinocytes of the skin13 and cells in the urothelium14,15 are also ACh-producing. Additionally, cells in blood vessel walls,16,17 as well as fibroblasts in various locations,18 show production of ACh. An occurrence of expression of non-neuronal ACh and ACh-synthesizing activity has also previously been shown for a variety of plants and organisms including fungi, algae and bacteria.19,20 The occurrence of a non-neuronal ACh production includes the situation for certain cancer cells and for inflammatory cells. It has been shown that ACh is synthesized by cells of small lung cell carcinoma,21,22 colon cancer,23,24 and breast cancer.25 Furthermore, inflammatory cells have been shown to produce ACh.26 The effects of ACh on the functions of inflammatory cells do occur principally via effects on the α7nAChR. Recently we found that the tendon cells (tenocytes) in patellar27,28 and Achilles29 tendons showed evidence of ACh production. This was observed by analysis of ChAT and VAChT reactions at both protein and mRNA level. We have furthermore observed that mononuclear- and fibroblast-like cells of the synovium of patients with severe RA and OA show ChAT expression.30 We have also made original findings regarding the colon of patients with ulcerative colitis (UC). In the colon from patients with UC, cells, including inflammatory cells in the lamina propria, cells of the blood vessel walls, and cells of the epithelial layer, were identified as being capable of ACh synthesis.31 In the following text, the aspects of the non-cholinergic effects in the locomotor system are focused upon. In our recent studies on the synovium of joints, and tendons of man we found a marked occurrence of the M2 type of mAChRs. Immunoreactions for the M2 receptor were observed for the tenocytes, nerves, and blood vessel walls of Achilles and patellar tendons,27–29 and were also noted in the synovial tissue from patients with RA as well as from those with OA. An interesting aspect noted is the fact that the evidence for a non-neuronal cholinergic system in tendon and synovial tissues is particularly apparent in pathological situations. Thus, the levels of expression of enzymes catalyzing ACh production, as well as the levels of expressions of mAChRs, were much more evidently seen in deranged and chronically painful tendinosis tendons than in normal tendons.27–29 A schematic drawing summarizing the non-neuronal cholinergic system of human tendinosis tendons is shown in Figure 1. Furthermore, expression of enzyme related to ACh production was marked in specimens of the synovial tissue of knee joints of RA patients exhibiting pronounced invasion of mononuclear-like cells, as well as showing the occurrence of numerous fibroblast-like cells.30 Such an expression was also noted for mononuclear-like and fibroblast-like cells in specimens of the synovial tissue of OA patients.30 Concerning the synovial specimens of both RA and OA patients, these corresponded to specimens of biopsies taken during prosthesis operations.

Figure 1.

Schematic drawing of human tendon tissue showing the occurrence of a non-neuronal cholinergic system in tendinosis. Violet dots represent acetylcholine (ACh) that is locally produced in tenocytes of pathological appearance (unfilled arrow). Normal looking tenocytes (filled arrow) do not produce ACh. 27–29 ACh can influence 1) nerves, 2) cells of blood vessel walls, and 3) the tenocytes themselves. These structures have been shown to be supplied with muscarinic ACh receptors of subtype M2 (M2R).27–29 Image by Gustav Andersson.

The functions of the neuronal and non-neuronal cholinergic systems

Effects in general

The responses in the effector organs to impulses leading to release and effects of ACh from the autonomic nervous system are well described in textbooks. Typical features are a decrease in heart rate, contraction of the sphincter muscle of the iris, contraction of bronchial muscles, and increased exocrine secretion from the pancreas. These are effects of ACh released from postganglionic parasympathetic nerve fibres. In the intestine, for example, it is well known that stimulation by ACh leads to an increase in smooth muscle contraction and a stimulation of secretion.

Based on results of studies on experimental animals, it has been theorized that ACh released from cholinergic nerves is involved in vasoregulation in joints.32 However, as described above, it has not yet been proven whether cholinergic nerves are present in the synovial tissues. There are no reports of effects of neuronally-released ACh within tendons.

The function of non-neuronal ACh is in principle related to autocrine/paracrine actions.10,20 Thus, the cells types producing ACh are also equipped with receptors for this substance. That includes, for example, the situation for the non-neuronal cholinergic system of the granulose cells in the human ovary.33 More precisely, the functions of the non-neuronal cholinergic system are mainly related to effects on differentiation and growth, secretion, barrier functions, and immuno-modulation (for reviews, see Kawashima and Fujii34 and Wessler and Kirkpatrick20). Important ACh effects are those on angiogenesis,35,36 proliferation rates,13,37,38 and wound healing.13,39

It is frequently emphasized that the ACh that is produced by the inflammatory cells has effects on those cells, suggesting that ACh modulates the activity of inflammatory cells via autocrine and paracrine loops.40 The influences of ACh on the inflammatory cells may be related to the time scale with acute stimulation leading to proinflammatory effects whilst chronic stimulation, on the other hand, has anti-inflammatory effects.40 The overwhelming majority of studies on ACh effects in relation to inflammation do, nevertheless, support the view that ACh has anti-inflammatory effects (see further below).

The cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway

Based on findings by several groups, the existence of a so-called ‘cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway’ has been proposed.41–44 This implies that ACh, released in response to activation of nerve fibres like those of the vagal nerve, has effects on local inflammation.45 Electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve leads to inhibition in the synthesis of TNFα, and attenuates the release of different pro-inflammatory cytokines.41,42 The vagal anti-inflammatory effects are known to be mediated by the Jak2/STAT3 signaling on macrophages42 or via inhibition of the transcription factor NF-kappaB.46 It should be remembered that there are variations between different organs concerning the occurrence of anti-inflammatory effects via stimulation of the vagus nerve. Such a stimulation has a marked anti-inflammatory effect within the gastrointestinal tract,42 but a limited anti-inflammatory effect in the lungs.41

The spleen has been shown to be important in mediating the antiinflammatory effects that occur in response to electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve.47

The cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway is shown to regulate the production of TNFα by macrophages via effects on preganglionic neurons related to the vagus nerve and via effects on postganglionic neurons originating in the celiac-superior mesenteric plexus and projecting within the splenic nerve.48 The findings that muscarinic receptor antagonists mediate anti-inflammatory actions favor the suggestion that there is a cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway.49 Nevertheless, it is the α7nAChR that is the ACh receptor, that is the essential receptor for the inhibition of cytokine synthesis via the cholinergic anti-inflammmatory pathway.50,51 One structure that may be a target for anti-inflammatory cholinergic mediators is the endothelium, as the endothelium is a key regulator of leukocyte trafficking during inflammation.52

The occurrence of anti-inflammatory effects of the parasympathetic nervous system has been shown in different ways. The anti-inflammatory effects that cholecystokinin is known to have are thus mediated by the vagus nerve53 and activation of the vagus nerve prevents manipulation-induced inflammation of the smooth muscle layers.42 Interestingly, it is suggested that anti-inflammatory effects not only occur via the neuronal but also the non-neuronal cholinergic system,40 and furthermore, that the release of non-neuronal ACh from local cells, such as inflammatory cells, is triggered by neuronally-released ACh.20

Changes in magnitude of the non-neuronal cholinergic system: occurrence of up- and downregulations

The new information obtained in our laboratory shows that there is a more clearly marked non-neuronal cholinergic system in tendinosis tendons than in normal tendons.27–29 Further-more, there is an extensive expression of M2 receptors in tendinosis tendons, but clearly less so in normal tendons. It is also a fact that the non-neuronal cholinergic system is represented to a large extent in the synovial tissue in RA if the tissue is heavily infiltrated with inflammatory cells and fibroblasts.30 Many of these cells show expression for the ACh-synthesizing enzyme ChAT. Upregulation of the cholinergic system also occurs in other situations, for example such an upregulation has been reported for cancer cells.22 It has also been shown that the cholinergic system is up-regulated in the superficial skin in atopic dermatitis.54 However, the situation is apparently different in certain acute situations. Thus, there is a decrease in non-neuronal ACh synthesis in an acute model of allergic airway inflammation.55 Whether upregulation of ACh production in non-neuronal cells is of positive or negative character for the tissue is only partly known. Obtaining a reduction in pulmonary ACh content in experimental studies of lung injury was considered to be of positive character, protecting the lung tissue.56 Further aspects on this question are discussed below. For many conditions it seems as if an increased ACh effect would be welcome. Cancer is a major exception (see further below).

Treatments leading to interference with cholinergic effects

General aspects

Anti-cholinergics are useful in certain clinical situations. However, treatments leading to cholinergic upregulation may also have a positive outcome. Thus, as will be further discussed below, treatment with AChE inhibitors, leading to increased ACh levels, has been found to be a treatment of choice in Alzheimer's disease. Furthermore, the concept of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway implies that inducing increased ACh effects may be favorable for inflammatory situations.

There are also other reports suggesting that increased ACh effects may be helpful clinically. The results of recent studies on cystic fibrosis suggest that treatment with muscarinic receptor agonists may be beneficial.57 Furthermore, in a recent experimental study on acute allergic airway inflammation, the occurrence of a downregulations of non-neuronal ACh synthesis and release machinery was furthermore suggested to contribute to epithelial shedding and ciliated dysfunction.55

Treatment with AChE inhibitors

Over recent decades, a number of therapies aimed at up-regulating cholinergic function have been tested as treatment for Alzheimer's disease, with AChE inhibitors being the group of substances that are best developed (for a review, see Shah et al.58). Thus, compounds frequently used nowadays for the treatment of mild forms of this disease are blockers of AChE activity59. The basis for this is the well-known fact that there is a loss of cholinergic function in Alzheimer's disease and that AChE is the enzyme that degrades ACh. AChE inhibitors are also used in myasthenia gravis.60 Cholinergic agonism, via administration of an AChE inhibitor, has also been tested for multiple sclerosis (MS) patients, and this agonism was hereby shown to alter cognitive processing and to enhance brain functional connectivity.61 In studies on experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, which is a model for the pathology of MS, it was found that treatment with an AChE inhibitor suppressed neuroinflammation and showed immunomodulatory activity.62 A scheme of the anti-inflammatory outcome that is achieved using AChE inhibitors during experimental neuroinflammation has recently been depicted by Brenner and collaborators.63 These authors found that the AChE inhibitors induced cholinergic upregulation and effects on the neuroinflammation via α7nAChR expressing cells.63

It has been shown that treatment of mice with AChE inhibitors attenuates the production of interleukin-1beta in both the hippocampus and blood, showing that cholinergic enhancement produces both central and peripheral anti-inflammatory effects.64 The results of studies on endotoxemia also suggest that centrally acting cholinergic enhancers may have anti-inflammatory properties.43 Inhibition of brain AChE via treatment with AChE inhibitors has recently been shown to suppress systemic inflammation, suggesting that the brain's cholinergic muscarinic networks communicate with the anti-inflammatory pathway thereby suppressing peripheral inflammation.65

Obtaining of cholinergic anti-inflammatory effects via the nicotinic pathway

Nicotine is more active than ACh in inhibiting the production of pro-inflammatory mediators by macrophages.51 The anti-inflammatory effects of nicotine on these cells can be counteracted by selective α7-antagonists.45 Influences on the nAChRs via nicotine have been tested in clinical situations, especially in UC. The therapeutic benefit is, however, limited, and troublesome side-effects of nicotine occur.66

The effects of ACh stimulation on the α7nAChR may, due to the known relationship between this receptor and inflammation, be of importance in inflammatory conditions. Accordingly, it is suggested that α7nAChRs play a critical role in the protection against the development of neurodegenerative diseases.67 The use of selective α7nAChR agonists has, furthermore, been shown to be of value in order to diminish cytokine production by macrophages and inflammation in several animal models of inflammation (for a review, see de Jonge and Ulloa68).

Possible usefulness of interference with cholinergic effects in certain conditions

Cancer

It is well-known that ACh receptors, including both mAChRs and nAChRs, are functionally present on certain cancer cells (for reviews, see Paleari et al. 200869 and Song and Spindel 200822). This includes the cancer cells in small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC), in which the cells have been shown to synthesize and secrete ACh, and to be equipped with mAChRs and nAChRs.21 The M3 mAChR is over-expressed in tumor cells of colon cancer.70 In recent studies it was shown that cells of the human colon cancer cell line HT-29 express the α7nAChR subtype.24

It is known that the level of cholinergic signaling is up-regulated in squamous cell carcinoma,22 and that stimulation of cells of mammary adenocarcinoma cell lines with carbacol increases their proliferation via M3 mAChR-mediated pathways.71 It is suggested that mAChR antagonists may be useful adjuncts for SCLC treatment,21 and that blocking cholinergic signaling can limit the growth of squamous lung carcinoma.22 In accordance with the latter suggestion, α7nAChR antagonists are anticipated to be a useful adjunct to the treatment of such lung cancer.72 The potential implications of mAChRs in tumor progression and the possible use of muscarinic ligands in cancer therapy have been recently reviewed.73 The fact that cholinergic signaling is increased in certain cancers may reinforce the usefulness of ACh blockade in these situations. It should be stressed that stimulation of ACh leads to an increase in cell proliferation13,38 and to angiogenesis.36 The fact that ACh stimulation leads to these features indeed favors the proposal that blocking the effects of ACh may be beneficial in cancers showing an upregulation of cholinergic features. The fact that ACh inhibits long-term hypoxia-induced apoptosis in mouse stem cells,74 and that nicotine increases cell growth of a human colon cancer cell line, the effect being depressed by an antagonist to the α7nAChR,24,75 also supports such a suggestion.

Pain conditions

Interference with cholinergic effects may have some relevance in relation to pain.76,77 ACh has been shown to induce pain when applied to human skin.78 However, cholinergic effects have mainly been found to be of an analgesic nature. Administration of mucarinic agonists with effects on the central nervous system can thus induce pronounced analgesic effects.77 Inflammatory joint pain can be partly modulated via muscarinic cholinergic receptors as shown in animal model studies,79 e.g., analgesia induced by an AChE inhibitor has been shown in a rat model.80 The possible usefulness of targeting the mAChRs in antinociception has been recently discussed.73

Chronic pain is the major symptomatic feature of tendinosis, and the pain mechanisms for this disease are still largely unknown and frequently discussed.81 The aspects of tendon pain in relation to the non-neuronal cholinergic system in tendon tissue are discussed below.

Tendinosis

In tendinosis, a non-inflammatory degenerative-like condition in which an increase in tissue cells (tenocytes) and a hypervascularity/ neovascularization are typical phenomena,82–84 it is likely that the proliferation of tenocytes and the angiogenesis are related to an initial tissue healing process in response to mechanically induced micro-trauma. The tenocytes are the cells that produce not only the collagen but also various signal substances that are likely to have important roles in the turnover of the extracellular matrix.85 However, the blood vessel changes may in the long run be a drawback. Thus, hypervascularity and neovascularization have been correlated with the chronic pain experienced in tendinosis,86 and new treatment methods focusing on destroying the region with hypervascularity/neovascularization by injection of the sclerosing substance polidocanol have not only led to pain relief but in the long-term perspective also to tendon remodeling.87–89

Given the information that tenocytes of tendinosis tendons produce ACh, and that there are mAChRs on the tenocytes and on the cells of the blood vessel walls,27,29 it is possible that the non-neuronal ACh might have effects on cell proliferation, collagen production, and blood vessel regulation in tendinosis. It is already known that ACh can increase the proliferation of myofibroblastic cells,90 and that stimulation of ACh receptors on certain fibroblasts may augment collagen accumulation.91 Also, as previously discussed, agonists of ACh receptors are known to promote angiogenesis.36 It might be that treatments that lead to increased cholinergic effects on the tenocytes and the blood vessels might be attractive in early stages of tendinosis. At these stages, an increased tenocyte population and an increased vascularity are likely to be of value for the tendon. On the other hand, less cholinergic influences on the blood vessels may be desirable in chronic stages. It may also be that an excess of tenocytes is a drawback for tendon function in the long run. The functional importance of the ACh production in the tenocytes, and the marked existence of mAChRs on these cells, as well as on blood vessel walls in tendinosis tendons, should be further explored.

One should bear in mind that signal substances other than ACh, e.g., catecholamines,92–94 and glutamate,95 are produced by tenocytes in tendinosis tendons and that the tenocytes are equipped with receptors for various signal substances. Furthermore, there is a production of neurotrophins in the tenocytes and the existence of the p75 neurotrophin receptor in these cells.96 This means that interactions between a number of substances that are delivered locally have to be considered. Some of the substances produced, such as glutamate, are likely to be toxic rather than related to wound healing. It may be that interference with cholinergic effects should be combined with interference with the effects of other type(s) of signal substances.

To further understand the pain mechanisms in tendinosis, the newly developed treatments for this condition should be considered. The sclerosing injection treatment, mentioned above, targets the regions of tendinosis Achilles and patellar tendons showing pathologically high blood flow.87,88 These regions conform to outer parts of the tendons (the paratendinous connective tissue). Our findings of an abundance of mAChRs in blood vessel walls in tendinosis tendons27,29 show that these vessels are under marked cholinergic influence. Nevertheless, it is probable that the pain-relief is not primarily related to effects on the vasculature but to effects on the nerves located close to the blood vessels. Consequently, it is interesting to note that we have also found mAChRs on nerve fascicles in the tendinosis tendons.27 To what extent the ACh effects, and those of other nerve signal substances such as substance P in the sensory innervation, are related to the pain symptoms in tendinosis must, however, await further studies.

Rheumatoid arthritis

It is evident that the infiltrating inflammatory cells, as well as the proliferating fibroblast-like cells, in the synovium become part of a non-neuronal cholinergic system in advanced RA, as verified by the expression of enzyme related to ACh production (ChAT). Such cells in synovial specimens of OA patients also show this feature. In both conditions, the existence of ChAT production was noted in specimens obtained after prosthesis operations. It may be that the existence of ACh production in these cells is related to trophic/modulatory and anti-inflammatory, rather than damaging, effects in the chronic stages of RA and OA. This could be seen as an attempt to balance the production of pro-inflammatory substances.

A favorable outcome in arthritis via cholinergic agonism has recently been shown experimentally in mice. Based on evaluating the effect of adding nicotine to the drinking water of mice with collagen-induced arthritis (CIA), the effects of vagotomy and the effects of treatment with an α7nAChR agonist, the authors concluded that there exists a cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway in the murine CIA model of RA.97 An existence of α7nAChRs on the fibroblast-like synoviocytes in human synovium has also been shown and ACh was found to inhibit cytokine expression through a post-transcriptional mechanism in these cells.98 In the study by Waldburger and collaborators,98 it was suggested that the α7nAChR is a potential therapeutic target for RA. In studies on a rat model of knee joint inflammation published as early as 1998, it was shown that a centrally administered AChE inhibitor, neostigmine, led to enhanced levels of endogenous ACh, which in turn functioned as an analgesia-modulating compound at both central and peripheral sites of inflammatory pain.80

It can be speculated that treatments that contribute to additional ACh effects could be useful in order to prevent the establishment of a marked derangement and damage of synovial tissues in advanced stages of RA and OA. Such interference would, thus, possibly lead to anti-inflammatory features. In accordance with such a suggestion are the recent findings by Goldstein and collaborators.99 In their studies it was shown that the occurrence of a diminished cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway activity is associated with increased levels of high mobility group box-1, a cytokine that is implicated in the pathogenesis of arthritis,100 in patients with RA.99

Conclusions

In summary, the basis for the present review is the fact that new indications for interference with cholinergic effects should be considered. The reason is that there exists a widespread local production of ACh in various tissues; a non-neuronal cholinergic system. ACh receptors are present in parallel. The effects of non-neuronal ACh are related to autocrine/ paracrine effects and effects on angiogenesis, cell proliferation, wound-healing, and inflammation. Our recent observations on the situation in tendinosis, RA, and OA show that there is an unexpected presence of a non-neuronal cholinergic system in these conditions. This means that new ideas for interference with cholinergic effects are indeed welcome for these situations.

What should be the focus for further studies evaluating the usefulness of interfering with cholinergic effects in various parts of the body? One field that should be further examined is the development of selective nicotinic agonists for man. The fact that selective α7nAChR agonists have been found to have positive effects in a dextran sulphate-induced colitis model for mice101 supports a suggestion that such agonists may be useful in inflammatory disorders. The idea that the α7nAChR is a target of importance in RA is discussed in the present review.

Another field that should be further concentrated on is research on the possible usefulness of AChE inhibitors in peripheral inflammatory disorders.64,65 Questions related to selectivity and specificity are, however, also warranted in this case.

In conclusion, knowledge of the occurrence of a marked local signal substance production within a diseased tissue, and the occurrence of receptors for the substances within the tissue, is on the whole of great importance for establishing new possible treatment strategies. It is obvious that it is not necessary that cholinergic nerves are present in order to make ACh available for the tissue; the substances can be locally produced. This means that not only should the neuronal but also the non-neuronal cholinergic system be taken into consideration when considering new treatments interfering with cholinergic effects. This includes disorders related to orthopedics, namely tendinosis, RA and OA.

Acknowledgments:

the authors thank Ms. U. Hedlund for excellent technical services, Drs. O. Grimsholm and M. Jönsson, and Mr. G. Andersson, for scientific co-operation on cholinergic research. Mr. Andersson is also acknowledged for the digital artwork of Figure 1. We finally thank Dr. A Scott for valuable collaboration on tendon research. The studies which are the bases for this review have been financially supported by the Faculty of Medicine at Umeå University, the Swedish National Centre for Research in Sports, the County Council of Västerbotten, the Arnerska Research Foundation, Lions Cancer Research Foundation, Dagmar Ferb's Memorial Foundation, the J.C. Kempe Memorial Foundation Scholarship Fund, the Magn. Bergvall Foundation, Muscle Fund North, and the J.C. Kempe and Seth M. Kempe Memorial Foundations, Örnsköldsvik.

References

- 1.Tuček S. The synthesis of acetylcholine in skeletal muscles of the rat. J Physiol. 1982;322:53–69. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tuček S. Choline acetyltransferase and the synthesis of acetylcholine. In: Whittaker VP, editor. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, 86, The Cholinergic Synapse. Berlin: Springer Verlag: 1988. pp. 125–65. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eiden LE. The cholinergic gene locus. J Neurochem. 1998;70:2227–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70062227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffman BB, Taylor P. Neurotransmission:the autonomic and somatic motor systems. In: Hardman JG, Limbird LE, editors. Goodman & Gilmnan's The Pharmalogical Basis of Therapeutics. 10th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 115–53. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miyazawa A, Fujiyoshi Y, Unwin N. Structure and gating mechanism of the acetylcholine receptor pore. Nature. 2003;423:949–55. doi: 10.1038/nature01748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Felder CC. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors: signal transduction through multiple effectors. FASEB J. 1995;9:619–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li M, Yasuda RP, Wall SJ, Wellstein A, Wolfe BB. Distribution of M2 muscarinic receptors in rat brain using antisera selective for M2 receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 1991;40:28–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iino S, Nojyo Y. Muscarinic M2 acetylcholine receptor distribution in the guinea-pig gastrointestinal tract. Neuroscience. 2006;138:549–59. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lloyd GK, Williams M. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors as novel drug targets. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;292:461–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wessler I, Kilbinger H, Bittinger F, Kirkpatrick CJ. The biological role of non-neuronal acetylcholine in plants and humans. Jpn J Pharmacol. 2001;85:2–10. doi: 10.1254/jjp.85.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klapproth H, Reinheimer T, Metzen J, et al. Non-neuronal acetylcholine, a signalling molecule synthezised by surface cells of rat and man. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1997;355:515–23. doi: 10.1007/pl00004977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ratcliffe EM, deSa DJ, Dixon MF, Stead RH. Choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) immunoreactivity in paraffin sections of normal and diseased intestines. J Histochem Cytochem. 1998;46:1223–31. doi: 10.1177/002215549804601102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grando SA, Pittelkow MR, Schallreuter KU. Adrenergic and cholinergic control in the biology of epidermis: physiological and clinical significance. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:1948–65. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lips KS, Wunsch J, Zarghooni S, et al. Acetylcholine and molecular components of its synthesis and release machinery in the urothelium. Eur Urol. 2007;51:1042–53. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshida M, Masunaga K, Satoji Y, et al. Basic and clinical aspects of non-neuronal acetylcholine: expression of non-neuronal acetylcholine in urothelium and its clinical significance. J Pharmacol Sci. 2008;106:193–8. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fm0070115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haberberger RV, Bodenbenner M, Kummer W. Expression of the cholinergic gene locus in pulmonary arterial endothelial cells. Histochem Cell Biol. 2000;113:379–87. doi: 10.1007/s004180000153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ikeda C, Morita I, Mori A, et al. Phorbol ester stimulates acetylcholine synthesis in cultured endothelial cells isolated from porcine cerebral microvessels. Brain Res. 1994;655:147–52. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91608-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lips KS, Pfeil U, Reiners K, et al. Expression of the high-affinity choline transporter CHT1 in rat and human arteries. J Histochem Cytochem. 2003;51:1645–54. doi: 10.1177/002215540305101208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horiuchi Y, Kimura R, Kato N, et al. Evolutional study on acetylcholine expression. Life Sci. 2003;72:1745–56. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)02478-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wessler I, Kirkpatrick CJ. Acetylcholine beyond neurons: the non-neuronal cholinergic system in humans. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:1558–71. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song P, Sekhon HS, Lu A, et al. M3 muscarinic receptor antagonists inhibit small cell lung carcinoma growth and mitogenactivated protein kinase phosphorylation induced by acetylcholine secretion. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3936–44. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song P, Spindel ER. Basic and clinical aspects of non-neuronal acetylcholine: expression of non-neuronal acetylcholine in lung cancer provides a new target for cancer therapy. J Pharmacol Sci. 2008;106:180–5. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fm0070091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng K, Samimi R, Xie G, et al. Acetylcholine release by human colon cancer cells mediates autocrine stimulation of cell proliferation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;295:G591–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00055.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pettersson A, Nilsson L, Nylund G, et al. Is acetylcholine an autocrine/paracrine growth factor via the nicotinic α7-receptor subtype in the human colon cancer cell line HT-29? Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;609:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Espanol AJ, de la Torre E, Fiszman GL, Sales ME. Role of non-neuronal cholinergic system in breast cancer progression. Life Sci. 2007;80:2281–5. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawashima K, Fujii T. Expression of non-neuronal acetylcholine in lymphocytes and its contribution to the regulation of immune function. Front Biosci. 2004;9:2063–85. doi: 10.2741/1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Danielson P, Alfredson H, Forsgren S. Immunohistochemical and histochemical findings favoring the occurrence of autocrine/paracrine as well as nerve-related cholinergic effects in chronic painful patellar tendon tendinosis. Microsc Res Tech. 2006;69:808–19. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Danielson P, Andersson G, Alfredson H, Forsgren S. Extensive expression of markers for acetylcholine synthesis and of M2 receptors in tenocytes in therapy-resistant chronic painful patellar tendon tendinosis - a pilot study. Life Sci. 2007;80:2235–8. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bjur D, Danielson P, Alfredson H, Forsgren S. Presence of a non-neuronal cholinergic system and occurrence of up- and down- regulation in expression of M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors: new aspects of importance regarding Achilles tendon tendinosis (tendinopathy) Cell Tissue Res. 2008;331:385–400. doi: 10.1007/s00441-007-0524-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grimsholm O, Rantapaa-Dahlqvist S, Dalen T, Forsgren S. Unexpected finding of a marked non-neuronal cholinergic system in human knee joint synovial tissue. Neurosci Lett. 2008;442:128–33. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.06.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jonsson M, Norrgard O, Forsgren S. Presence of a marked nonneuronal cholinergic system in human colon: study of normal colon and colon in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:1347–56. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDougall JJ, Elenko RD, Bray RC. Cholinergic vasoregulation in normal and adjuvant monoarthritic rat knee joints. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1998;72:55–60. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1838(98)00087-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fritz S, Fohr KJ, Boddien S, et al. Functional and molecular characterization of a muscarinic receptor type and evidence for expression of choline-acetyltransferase and vesicular acetylcholine transporter in human granulosa-luteal cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:1744–50. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.5.5648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawashima K, Fujii T. Basic and clinical aspects of non-neuronal acetylcholine: overview of non-neuronal cholinergic systems and their biological significance. J Pharmacol Sci. 2008;106:167–73. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fm0070073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cooke JP. Angiogenesis and the role of the endothelial nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Life Sci. 2007;80:2347–51. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.01.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jacobi J, Jang JJ, Sundram U, et al. Nicotine accelerates angiogenesis and wound healing in genetically diabetic mice. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:97–104. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64161-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grando SA, Crosby AM, Zelickson BD, Dahl MV. Agarose gel keratinocyte outgrowth system as a model of skin re-epithelization: requirement of endogenous acetylcholine for outgrowth initiation. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;101:804–10. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12371699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Metzen J, Bittinger F, Kirkpatrick CJ, et al. Proliferative effect of acetylcholine on rat trachea epithelial cells is mediated by nicotinic receptors and muscarinic receptors of the M1-subtype. Life Sci. 2003;72:2075–80. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00086-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tournier JM, Maouche K, Coraux C, et al. α3α5beta2-Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor contributes to the wound repair of the respiratory epithelium by modulating intracellular calcium in migrating cells. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:55–68. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kawashima K, Fujii T. The lymphocytic cholinergic system and its contribution to the regulation of immune activity. Life Sci. 2003;74:675–96. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Borovikova LV, Ivanova S, Zhang M, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation attenuates the systemic inflammatory response to endotoxin. Nature. 2000;405:458–62. doi: 10.1038/35013070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Jonge WJ, van der Zanden EP, The FO, et al. Stimulation of the vagus nerve attenuates macrophage activation by activating the Jak2-STAT3 signaling pathway. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:844–51. doi: 10.1038/ni1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pavlov VA, Ochani M, Gallowitsch-Puerta M, et al. Central muscarinic cholinergic regulation of the systemic inflammatory response during endotoxemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:5219–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600506103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tracey KJ. Physiology and immunology of the cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:289–96. doi: 10.1172/JCI30555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tracey KJ. The inflammatory reflex. Nature. 2002;420:853–9. doi: 10.1038/nature01321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang H, Liao H, Ochani M, et al. Cholinergic agonists inhibit HMGB1 release and improve survival in experimental sepsis. Nat Med. 2004;10:1216–21. doi: 10.1038/nm1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huston JM, Ochani M, Rosas-Ballina M, et al. Splenectomy inactivates the cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway during lethal endotoxemia and polymicrobial sepsis. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1623–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosas-Ballina M, Ochani M, Parrish WR, et al. Splenic nerve is required for cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway control of TNF in endotoxemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:11008–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803237105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Profita M, Giorgi RD, Sala A, et al. Muscarinic receptors, leukotriene B4 production and neutrophilic inflammation in COPD patients. Allergy. 2005;60:1361–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ben-Horin S, Chowers Y. Neuroimmunology of the gut: physiology, pathology, and pharmacology. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8:490–5. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang H, Yu M, Ochani M, et al. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α7 subunit is an essential regulator of inflammation. Nature. 2003;421:384–8. doi: 10.1038/nature01339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saeed RW, Varma S, Peng-Nemeroff T, et al. Cholinergic stimulation blocks endothelial cell activation and leukocyte recruitment during inflammation. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1113–23. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Luyer MD, Greve JW, Hadfoune M, et al. Nutritional stimulation of cholecystokinin receptors inhibits inflammation via the vagus nerve. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1023–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wessler I, Reinheimer T, Kilbinger H, et al. Increased acetylcholine levels in skin biopsies of patients with atopic dermatitis. Life Sci. 2003;72:2169–72. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lips KS, Luhrmann A, Tschernig T, et al. Downregulation of the non-neuronal acetylcholine synthesis and release machinery in acute allergic airway inflammation of rat and mouse. Life Sci. 2007;80:2263–9. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grau V, Wilker S, Lips KS, et al. Administration of keratinocyte growth factor down-regulates the pulmonary capacity of acetylcholine production. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:1955–63. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wessler I, Bittinger F, Kamin W, et al. Dysfunction of the non-neuronal cholinergic system in the airways and blood cells of patients with cystic fibrosis. Life Sci. 2007;80:2253–8. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shah RS, Lee HG, Xiongwei Z, et al. Current approaches in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Biomed Pharmacother. 2008;62:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Desai AK, Grossberg GT. Diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 2005;64:S34–9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.64.12_suppl_3.s34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Conti-Fine BM, Milani M, Kaminski HJ. Myasthenia gravis: past, present, and future. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2843–54. doi: 10.1172/JCI29894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cader S, Palace J, Matthews PM. Cholinergic agonism alters cognitive processing and enhances brain functional connectivity in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Psychopharmacol 2008 E-pub ahead of print. doi: 10.1177/0269881108093271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nizri E, Irony-Tur-Sinai M, Faranesh N, et al. Suppression of neuroinflammation and immunomodulation by the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor rivastigmine. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;203:12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brenner T, Nizri E, Irony-Tur-Sinai M, et al. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and cholinergic modulation in Myasthenia Gravis and neuroinflammation. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;201–202:121–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pollak Y, Gilboa A, Ben-Menachem O, et al. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors reduce brain and blood interleukin-1beta production. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:741–5. doi: 10.1002/ana.20454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pavlov VA, Parrish WR, Rosas-Ballina M, et al. Brain acetylcholinesterase activity controls systemic cytokine levels through the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23:41–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thomas GA, Rhodes J, Ingram JR. Mechanisms of disease: nicotine--a review of its actions in the context of gastrointestinal disease. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;2:536–44. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Streit WJ. Microglia as neuroprotective, immunocompetent cells of the CNS. Glia. 2002;40:133–9. doi: 10.1002/glia.10154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.de Jonge WJ, Ulloa L. The α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor as a pharmacological target for inflammation. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;151:915–29. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Paleari L, Grozio A, Cesario A, Russo P. The cholinergic system and cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2008;18:211–7. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang WL, Frucht H. Cholinergic receptor up-regulates COX-2 expression and prostaglandin E(2) production in colon cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1789–93. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.10.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Espanol AJ, Sales ME. Different muscarinc receptors are involved in the proliferation of murine mammary adenocarcinoma cell lines. Int J Mol Med. 2004;13:311–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Grozio A, Paleari L, Catassi A, et al. Natural agents targeting the α7-nicotinic-receptor in NSCLC: a promising prospective in anti-cancer drug development. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:1911–5. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tata AM. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors: new potential therapeutic targets in antinociception and in cancer therapy. Recent Pat CNS Drug Discov. 2008;3:94–103. doi: 10.2174/157488908784534621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim MH, Kim MO, Heo JS, et al. Acetylcholine inhibits long-term hypoxia-induced apoptosis by suppressing the oxidative stress-mediated MAPKs activation as well as regulation of Bcl-2, c-IAPs, and caspase-3 in mouse embryonic stem cells. Apoptosis. 2008;13:295–304. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0160-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wong HP, Yu L, Lam EK, et al. Nicotine promotes cell proliferation via α7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and catecholaminesynthesizing enzymes-mediated pathway in human colon adenocarcinoma HT-29 cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;221:261–7. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dussor GO, Helesic G, Hargreaves KM, Flores CM. Cholinergic modulation of nociceptive responses in vivo and neuropeptide release in vitro at the level of the primary sensory neuron. Pain. 2004;107:22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wess J, Duttaroy A, Gomeza J, et al. Muscarinic receptor subtypes mediating central and peripheral antinociception studied with muscarinic receptor knockout mice: a review. Life Sci. 2003;72:2047–54. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00082-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vogelsang M, Heyer G, Hornstein OP. Acetylcholine induces different cutaneous sensations in atopic and non-atopic subjects. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:434–6. doi: 10.2340/0001555575434436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Baek YH, Choi DY, Yang HI, Park DS. Analgesic effect of electroacupuncture on inflammatory pain in the rat model of collagen-induced arthritis: mediation by cholinergic and serotonergic receptors. Brain Res. 2005;1057:181–5. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Buerkle H, Boschin M, Marcus MA, et al. Central and peripheral analgesia mediated by the acetylcholinesterase-inhibitor neostigmine in the rat inflamed knee joint model. Anesth Analg. 1998;86:1027–32. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199805000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Khan KM, Cook JL, Maffulli N, Kannus P. Where is the pain coming from in tendinopathy? It may be biochemical, not only structural, in origin. Br J Sports Med. 2000;34:81–3. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.34.2.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cook JL, Malliaras P, De Luca J, et al. Neovascularization and pain in abnormal patellar tendons of active jumping athletes. Clin J Sport Med. 2004;14:296–9. doi: 10.1097/00042752-200409000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Khan KM, Cook JL, Bonar F, et al. Histopathology of common tendinopathies. Update and implications for clinical management. Sports Med. 1999;27:393–408. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199927060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Movin T, Gad A, Reinholt FP, Rolf C. Tendon pathology in long-standing achillodynia. Biopsy findings in 40 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1997;68:170–5. doi: 10.3109/17453679709004002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Riley G. Chronic tendon pathology: molecular basis and therapeutic implications. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2005;7:1–25. doi: 10.1017/S1462399405008963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cook JL, Malliaras P, De Luca J, Ptasznik R, Morris M. Vascularity and pain in the patellar tendon of adult jumping athletes: a 5 month longitudinal study. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:458–61. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2004.014530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Alfredson H, Ohberg L. Sclerosing injections to areas of neo-vascularisation reduce pain in chronic Achilles tendinopathy: a double-blind randomised controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2005;13:338–44. doi: 10.1007/s00167-004-0585-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hoksrud A, Ohberg L, Alfredson H, Bahr R. Ultrasound-guided sclerosis of neovessels in painful chronic patellar tendinopathy: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:1738–46. doi: 10.1177/0363546506289168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Willberg L, Sunding K, Ohberg L, et al. Treatment of Jumper's knee: promising short-term results in a pilot study using a new arthroscopic approach based on imaging findings. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:676–81. doi: 10.1007/s00167-006-0223-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Oben JA, Yang S, Lin H, et al. Acetylcholine promotes the proliferation and collagen gene expression of myofibroblastic hepatic stellate cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;300:172–7. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02773-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sekhon HS, Keller JA, Proskocil BJ, et al. Maternal nicotine exposure upregulates collagen gene expression in fetal monkey lung. Association with α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;26:31–41. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.1.4170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bjur D, Danielson P, Alfredson H, Forsgren S. Immunohistochemical and in situ hybridization observations favor a local catecholamine production in the human Achilles tendon. Histol Histopathol. 2008;23:197–208. doi: 10.14670/HH-23.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Danielson P, Alfredson H, Forsgren S. Studies on the importance of sympathetic innervation, adrenergic receptors, and a possible local catecholamine production in the development of patellar tendinopathy (tendinosis) in man. Microsc Res Tech. 2007;70:310–24. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Danielson P, Alfredson H, Forsgren S. In situ hybridization studies confirming recent findings of the existence of a local nonneuronal catecholamine production in human patellar tendinosis. Microsc Res Tech. 2007;70:908–11. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Scott A, Alfredson H, Forsgren S. VGluT2 expression in painful Achilles and patellar tendinosis: evidence of local glutamate release by tenocytes. J Orthop Res. 2008;26:685–92. doi: 10.1002/jor.20536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bagge J, Lorentzon R, Alfredson H, Forsgren S. Unexpected presence of the neurotrophins NGF and BDNF and the neurotrophin receptor p75 in the tendon cells of the human Achilles tendon. Histol Histopathol. 2009;24:839–48. doi: 10.14670/HH-24.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.van Maanen MA, Lebre MC, van der Poll T, et al. Stimulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors attenuates collagen-induced arthritis in mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:114–22. doi: 10.1002/art.24177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Waldburger JM, Boyle DL, Pavlov VA, et al. Acetylcholine regulation of synoviocyte cytokine expression by the α7 nicotinic receptor. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3439–49. doi: 10.1002/art.23987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Goldstein RS, Bruchfeld A, Yang L, et al. Cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway activity and High Mobility Group Box-1 (HMGB1) serum levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Mol Med. 2007;13:210–5. doi: 10.2119/2006-00108.Goldstein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pullerits R, Jonsson IM, Verdrengh M, et al. High mobility group box chromosomal protein 1, a DNA binding cytokine, induces arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:1693–700. doi: 10.1002/art.11028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ghia JE, Blennerhassett P, Kumar-Ondiveeran H, et al. The vagus nerve: a tonic inhibitory influence associated with inflammatory bowel disease in a murine model. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1122–30. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]