Abstract

Dentin collagen is a major component of the hybrid layer, and its stability may have a great impact on the properties of adhesive interfaces. We tested the hypothesis that the use of tannic acid (TA), a collagen cross-linking agent, may affect the mechanical properties and stability of the dentin matrix. The present study evaluated the effects of different concentrations of TA on the modulus of elasticity and enzymatic degradation of dentin matrix. Hence, the effect of TA pre-treatment on resin-dentin bond strength was assessed with the use of two bonding systems. Sound human molars were used and prepared according to each experimental design. The use of TA affected the properties of demineralized dentin by increasing its stiffness. TA treatment inhibited the effect of collagenase digestion on dentin matrix, particularly for 10%TA and 20%TA. The TA-dentin matrix complex resulted in improved bond strength for both adhesive systems.

Keywords: collagen, dentin, tannic acid, biomimetics, bond strength

Introduction

Even with all the advances in the development of restorative systems with superior mechanical properties, a composite resin restoration lasts an average of 7 yrs in posterior teeth (Mjör, 1997; Burke et al., 1999; Mjör et al., 2000; Bogacki et al., 2002; Sarrett, 2005). Clinical studies have reported that approximately 50% of all restorations placed by dentists replace existing restorations (Burke et al., 1999; Mjör et al., 2000; Bogacki et al., 2002; Sarrett, 2005). Failure at the material-tooth interface (secondary caries) is the primary reason given for the replacement of composite restorations and accounts for 30-60% of all restorations placed (Burke et al., 1999; Mjör et al., 2000; Sarrett, 2005). Therefore, there is a necessity to improve the restoration interface to minimize the replacement of restorations and consequently improve health care and reduce health care costs.

The mechanical properties of dentin are a fundamental aspect of restorative procedures, since dentin constitutes the greatest volume of tooth structure. Dentin is a complex mineralized tissue arranged in an elaborate three-dimensional framework composed of tubules extending from the pulp to the dentino-enamel junction, and inter-tubular and peri-tubular dentin. It presents an intricate composition comprised of 70% (by weight) mineral, 20% organic components, and 10% water (Linde, 1989). As the major component of the dentin organic matrix, fibrillar type I collagen plays a number of structural roles, such as to provide the tissue with viscoelasticity, forming a rigid, strong space-filling biomaterial (Butler, 1995; Scott, 1995; Cheng et al., 1996). Type I collagen is a heterotrimeric molecule composed of two α1 chains and one α2 chain that is comprised of 3 domains: the NH2-terminal non-triple helical (N-telopeptide), the central triple helical, and the COOH-terminal non-triple helical (C-telopeptide) domains. Intermolecular cross-links are the basis for the stability, tensile strength, and viscoelasticity of the collagen fibrils (Yamauchi, 2000). Several synthetic and natural chemicals have the ability to increase the number of covalent inter- and intra-molecular collagen cross-links (Sung et al., 1999; Han et al., 2003) and affect its properties. Tannic acid, a commercial form of condensed tannin, is a naturally occurring polyphenol with weak acidity that has the ability to modify collagen chemically (Jastrzebska et al., 2006).

Alterations to the collagen, mostly by modification in the number of cross-links, provide the collagen matrix with enhanced mechanical properties and lower rates of enzymatic degradation. These two properties are desirable for dentin collagen as a component of tooth restorations. The purpose of this study was to assess the effect of tannic acid on the mechanical properties of dentin matrix and the resin-dentin bonded interface. The null hypotheses tested were that tannic acid has no affect on the stiffness or ultimate tensile strength of the dentin matrix or on resin-dentin bond strength.

Materials & Methods

After informed consent was obtained, 46 extracted human teeth were collected under a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board committee from the University of Illinois at Chicago (protocol #2006-0229). Tannic acid was obtained from Fisher Biotech (Fair Lawn, NJ, USA). Bacterial collagenase from Clostridium histolyticum (type I, > 125 CDU/mg solid) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Modulus of Elasticity of Demineralized Dentin

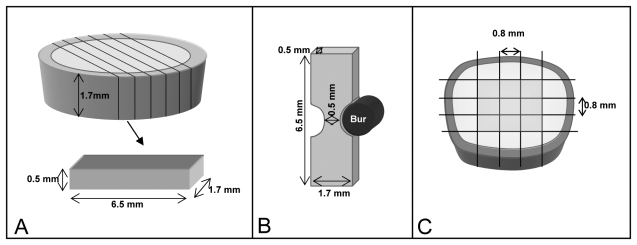

We obtained thick disks (1.7 ± 0.1 mm) from middle coronal dentin by sectioning the occlusal and cervical portions of each crown using a diamond wafering blade (Buehler-Series 15LC Diamond, Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL, USA). The disks were then sectioned into 0.5 ± 0.1-mm-thick beams (n = 5 beams per tooth) in the mesio-buccal direction and further trimmed by means of a cylindrical diamond bur (#557D, Brasseler, Savannah, GA, USA) to a final rectangular dimension of 0.5 mm thickness x 1.7 mm width x 6.5 mm length (Fig. A). A dimple was made at one end of each surface to allow for repeated measurements to be performed on the same surface. Samples were fully demineralized in a 10% phosphoric acid solution (LabChem Inc., Pittsburgh, PA, USA) for 5 hrs, which was verified by x-ray. [For complete method details, refer to Bedran-Russo et al. (2008).] Demineralized specimens (n = 36) were treated with 3 tannic acid (TA) concentrations [1, 10, and 20 w/v%] dissolved in distilled water. Specimens were immersed in water for baseline measurements and then in their respective TA solutions for 10 min, 30 min, 1 hr, 2 hrs, 24 hrs, and 48 hrs of cumulative exposure time.

Figure.

Sample preparation. (A) 1.7-mm disks of dentin were sectioned from the mid-coronal dentin. The disks were further sectioned occlusal-gingivally to obtain 0.5-mm dentin slices for evaluation of the ‘modulus of elasticity’ method of demineralized dentin. (B) The ultimate tensile strength test was performed with dentin slices obtained in the same manner as described for A, and specimens were further trimmed into an hour-glass-shaped sample. (C) Resin-dentin beams were obtained from the center of the occlusal surface to avoid enamel and extremes of the edge of dentin for microtensile bond strength.

An aluminum alloy fixture with a 2.5-mm span between supports was glued to the bottom of a glass Petri dish. Specimens were tested in compression, while immersed in distilled water, by means of a testing machine (EZ Graph, Shimadzu Co., Kyoto, Japan), with a 100-gram load cell at a crosshead speed of 0.5 mm/min. Load-displacement curves were converted to stress-strain curves, and the apparent modulus of elasticity was calculated at 3% strain (Bedran-Russo et al., 2008).

Resistance against Enzymatic Degradation—Ultimate Tensile Strength (UTS)

Dentin beams described above (Fig. A), but with dimensions of 0.5 x 1.7 x 6.5 mm, were made into hour-glass-shaped samples with a neck area of 0.5 ± 0.1 x 0.5 ± 0.1mm at middle dentin, with the use of a cylindrical diamond bur (Fig. B). These samples were fully demineralized in 10% phosphoric acid solution (LabChem, Inc.) for 5 hrs. Samples (n = 12) were randomly divided into 4 treatment groups: control (distilled water), 1% TA, 10% TA, and 20% TA. Specimens were kept in their solutions for 1 hr, thoroughly rinsed, and either subjected or not to enzymatic challenge for 24 hrs in 0.2 M ammonium bicarbonate buffer (pH = 9.5) or 24 hrs in the same buffer with bacterial collagenase (100 µg/mL). For UTS evaluation, the specimens were glued with a cyanoacrylate adhesive (Zapit; Dental Ventures of America Inc., Corona, CA, USA) to a jig, which was mounted on a microtensile tester machine (Bisco, Schaumburg, IL, USA) and tested at a crosshead speed of 1 mm/min.

Resin-Dentin Properties—Microtensile Bond Strength Test (µTBS)

The occlusal surfaces of 30 molars were ground flat with #180- and 320-grit silicon carbide paper for enamel removal, and with 600-grit silicon carbide paper under running water to expose middle crown dentin. The prepared dentin surfaces were randomly divided into 3 groups (n = 10): 20%TA (pH 2.8), 20%TA (pH 7.2), and control (distilled water). Each group was then subdivided according to the bonding systems used, Adper Single Bond Plus (3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA) or One Step Plus (Bisco). First, dentin was etched with the respective bonding system etchant and then treated for 1 hr with the respective test solutions. After 1 hr, samples were thoroughly rinsed for 4 min, and bonding procedures were resumed following the manufacturers’ instructions. We used Filtek supreme (3M ESPE) composite resin to build a 5-mm crown incrementally to allow for the testing. Specimens were stored in distilled water at 37°C for 24 hrs.

The bonded samples were then sectioned into 0.8 ± 0.1 by 0.8 ± 0.1-mm-thick beams, glued with a cyanoacrylate adhesive (Zapit) to a jig, which was mounted on a microtensile testing machine (Bisco) and subjected to tensile testing at a crosshead speed of 1 mm/min. Only 8 beams with the most dentin were tested (Fig. C).

The data from the 3 analyses were collected and statistically analyzed by two-way ANOVA and Fisher’s PLSD test at a 95% confidence interval.

Results

The moduli of elasticity of dentin matrices, as a function of tannic acid concentration treatment and exposure time, are listed in Table 1. No statistically significant interaction was observed between the two factors (treatment vs. time, p = 0.145). The different TA concentrations and exposure times significantly affected the stiffness values (p < 0.0001).

Table 1.

Changes in the Modulus of Elasticity of Human Demineralized Dentin Matrix over Time after the Use of Different Concentrations of Tannic Acid (TA)

| Modulus of Elasticity (MPa) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time |

|||||||

| Treatment | Baseline | 10 min | 30 min | 1 hr | 2 hrs | 24 hrs | 48 hrs |

| 1%TA | 6.53a | 26.32b | 48.32b | 66.79b | 90.06b | 159.76c | 192.18c |

| (1.64) | (9.67) | (18.98) | (32.07) | (40.05) | (54.44) | (85.99) | |

| 10%TA | 5.97a | 47.15b | 70.12b | 89.70b | 109.92b | 156.89c | 159.98c |

| (1.30) | (13.17) | (21.90) | (29.24) | (40.17) | (66.55) | (68.68) | |

| 20%TA | 6.65a | 63.69b | 98.00b | 124.70b | 144.99c | 182.31c | 174.55c |

| (1.65) | (23.39) | (30.06) | (45.09) | (51.94) | (69.03) | (63.92) | |

For each row, groups identified by different superscript letters are significantly different (p < 0.05). Results are means (± 1 SD), MPa, n = 12.

When demineralized dentin matrices were pre-treated with TA for 1 hr, the treatment significantly increased (p < 0.001) the UTS (Table 2). When specimens were incubated with bacterial collagenase for 24 hrs, the UTS of the untreated controls fell to zero, while the UTS values of the TA-treated specimens were not significantly different from those of control specimens incubated in buffer without collagenase (Table 2).

Table 2.

Resistance of Dentin Matrix to Collagenase Attack after 24-hour Treatment with Various Tannic Acid (TA) Concentrations with Ultimate Tensile Strength as a Measure of Matrix Degradation

| Ultimate Tensile Strength (MPa) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dentin Treatment for 1 hr |

||||

| Enzymatic Treatment | Control | 1% TA | 10% TA | 20% TA |

| Buffer (no treatment), 24 hrs | 8.94 (4.03)a | 13.87 (4.26)b | 14.87 (4.87)bc | 16.93 (5.79)c |

| Collagenase in buffer, 24 hrs | 0 (0) | 10.85 (4.36)b | 14.26 (4.65)bc | 15.64 (3.61)c |

For each row, groups identified by different superscript letters are significantly different (p < 0.05). Values are mean (± 1 SD), n = 12.

To determine if the carboxylic acid group of tannic acid contributed to increases in µTBS, we prepared two 20% solutions of TA (pH 2.8 vs. 7.2) to be far below and far above the pKa of TA (4.4). The resin-dentin bond strength data are given in Table 3. Two-way ANOVA revealed that there was no statistically significant interaction between the factors evaluated (surface treatment vs. adhesive system, p = 0.5717). Treatment of the surface with 20% tannic acid resulted in a statistically significant increase in the µTBS values when compared with those of a control group (p < 0.0001). The two formulations of TA with different pH were equal at increasing the bond strength (p = 0.2167), while the adhesive system (p = 0.0203) significantly affected the µTBS values.

Table 3.

Changes in the Microtensile Bond Strength of Adhesive Systems following Dentin Treatment with Tannic Acid (TA)

| Microtensile Bond Strength (MPa) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Adhesive Systems |

||

| Surface Treatment | Adper Single Bond Plus | One Step Plus |

| Control | 56.3 (21.7)a | 54.1 (14.2)a |

| 20% TA (pH 2.8) | 74.7 (14.9)c | 66.7 (8.1)b |

| 20% TA (pH 7.2) | 71.0 (14.5)c | 63.2 (9.4)b |

Same letters indicate no statistically significant differences between groups (p < 0.05). Values are mean (± SD), n = 40/cell.

Discussion

Reports of tannic acid use in dentistry as a desensitizing agent, astringent, and surface treatment for smear layer removal have been previously described (Bitter, 1989; Prati et al., 1992; Sabbak and Hassanin, 1998; Natsir et al., 1999; Okamoto et al., 1991; Tomiyama et al., 2004), but no information exists regarding its effect on the mechanical properties of dentin and adhesive-dentin interfaces. The present study showed that tannic acid significantly affected dentin matrix properties and resin-dentin bond strength; therefore, the null hypotheses must be rejected. While most efforts to improve the mechanical properties of dentin-bonded interfaces rely on improvement of restorative materials and techniques, the present study explored the potential effects of biochemical modifications to tooth structures on the behavior of dentin and dentin-bonded interfaces.

Analysis of the present data showed that the use of TA increased the modulus of elasticity of demineralized dentin matrix, where the effect was concentration- and time-dependant. Twenty percent TA resulted in the highest E values, and extended time exposure increased the dentin stiffness. Tannic acid is a naturally occurring collagen cross-linking agent consisting of a complex mixture of polygalloylglucose esters. Increased mechanical properties of collagen films and aortic wall after the use of TA have been reported (Koide and Daito, 1997; Isenburg et al., 2006). Structural and dynamic changes in TA-collagen interactions have been characterized by infra-red spectroscopy in TA-stabilized pericardial tissue (Jastrzebska et al., 2006). Hydrogen bonds are formed between amide NH groups from collagen and hydroxyl groups from TA (Jastrzebska et al., 2006). It can be expected that changes to dentin matrix would be similar to other type I collagen-based tissues; therefore, the formation of hydrogen bonds by TA is most likely accountable for the changes to dentin modulus of elasticity.

The assessment of collagen stability can be performed by subjecting dentin matrix to proteolytic challenge. The use of a traditional ‘ultimate tensile strength’ protocol revealed that dentin matrix samples that were treated with different concentrations of TA maintained their tensile strength values. In contrast, untreated samples (control) were fully digested by collagenase treatment after 24 hrs. Resistance to collagenase digestion is a crucial property of a TA-collagen matrix, since it indicates an increase in stability and possibly a protection mechanism against degradation over a long period of time. Analysis of the data indicates that TA treatment inhibited the action of collagenase, either by masking the cleavage sites or decreasing the enzymatic activity. Bacterial collagenase is a potent enzyme that has the ability to cleave collagen molecules at different sites. We speculated that the TA hydrogen-bonded to multiple sites on collagen molecules, and reduced possible cleavage sites and stabilized the TA-dentin matrix complex. In all demineralized dentin matrices, collagenolytic matrix metalloproteinases are bound to collagen. These endogenous MMPs may also be inhibited by TA (Pashley, unpublished observations). Hence, clinically exposed collagen would be subjected to degradation by endogenous MMPs (Hebling et al., 2005; Carrilho et al., 2007), which act in specific sites of the collagen molecule. The use of high concentrations of soluble bacterial collagenase represents a more aggressive bacterial challenge than could be expected by bound endogenous MMPs in 24 hrs.

Analysis of the bond strength data demonstrated that TA can increase the dentin-resin bond strength, regardless of the pH used. The results suggest that the degree of ionization of the carboxylic acid of TA has no influence on µTBS. In the µTBS studies, acid-etched dentin was treated with 20%TA for 1 hr, a treatment time that is not clinically appropriate. However, 20%TA treatment for 10 min produced an almost 6-fold increase in the modulus of elasticity of dentin matrices in this study. Future work will determine if shorter (e.g., 1-5 min) applications of 20%TA can result in higher µTBS. The effect of TA treatment on resin-enamel bond strengths must also be evaluated prior to recommended clinical use. It has been observed that 20% and 25%TA did not completely remove the smear layer on prepared dentin and left the orifices of dentinal tubules partially occluded when applied for 10 and 15 min to undemineralized dentin disks (Sabbak and Hassanin, 1998). Those results reinforce the weak acidity of TA (pKa = 4.4), which would probably have low impact on further demineralization of the dentin surface and consequently may partially explain the lack of difference in the bond strengths between pH 2.8 and 7.4 TA-treated groups. The use of 20% TA at pH 7.4 followed previous studies (Bedran-Russo et al., 2007) in which cross-linking solutions had their pH adjusted to a neutral level. Such a pH is more desirable, since it would have low impact on the undemineralized dentin and also on the mechanism of TA-collagen interaction (Ku et al., 2007). It has been reported that the interaction of proanthocyanidin (also a condensed tannin) with proline-rich proteins is pH-dependent, in which the greatest precipitation was found to be near the isoelectric point of protein (Bennick, 2002). Therefore, the use of pH 7.4 may be indicated during restorative procedures involving TA.

The ability of TA-dentin matrix complexes to increase the mechanical properties of dentin, reduce enzymatic degradation, and increase resin-dentin bond strength demonstrate the utility of incorporating tissue-engineering/biomimetic approaches into restorative dentistry. The use of biologically inspired mechanisms such as increased collagen stiffness by the presence of collagen cross-links and hydrogen bonds is possible by the use of naturally occurring products, such as tannic acid.

Footnotes

This investigation was supported by USPHS Research Grants DE017740 and DE015306 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA

A preliminary report was presented at the 37th AADR Annual Meeting in Dallas, TX, in 2008.

References

- Bedran-Russo AK, Pereira PN, Duarte WR, Drummond JL, Yamauchi M. (2007). Application of crosslinkers to dentin collagen enhances the ultimate tensile strength. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 80:268-272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedran-Russo AK, Pashley DH, Agee K, Drummond JL, Miescke KJ. (2008). Changes in stiffness of demineralized dentin following application of collagen crosslinkers. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 86:330-334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennick A. (2002). Interaction of plant polyphenols with salivary proteins. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 13:184-196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitter NC. (1989). Tannic acid for smear layer removal: pilot study with scanning electron microscope. J Prosthet Dent 61:503-507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogacki RE, Hunt RJ, del Aguila M, Smith WR. (2002). Survival analysis of posterior restorations using an insurance claims database. Oper Dent 27:488-492 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke FJ, Cheung SW, Mjör IA, Wilson NH. (1999). Restoration longevity and analysis of reasons for the placement and replacement of restorations provided by vocational dental practitioners and their trainers in the United Kingdom. Quintessence Int 30:234-242 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler WT. (1995). Dentin matrix proteins and dentinogenesis. Connect Tissue Res 33:59-65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrilho MR, Geraldeli S, Tay F, de Goes MF, Carvalho RM, Tjäderhane L, et al. (2007). In vivo preservation of the hybrid layer by chlorhexidine. J Dent Res 86:529-533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Caterson B, Neame PJ, Lester GE, Yamauchi M. (1996). Differential distribution of lumican and fibromodulin in tooth cementum. Connect Tissue Res 34:87-96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han B, Jaurequi J, Tang BW, Nimni ME. (2003). Proanthocyanidin: a natural crosslinking reagent for stabilizing collagen matrices. J Biomed Mater Res A 65:118-124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebling J, Pashley DH, Tjäderhane L, Tay FR. (2005). Chlorhexidine arrests subclinical degradation of dentin hybrid layers in vivo. J Dent Res 84:741-746; erratum in J Dent Res 85:384, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isenburg JC, Karamchandani NV, Simionescu DT, Vyavahare NR. (2006). Structural requirements for stabilization of vascular elastin by polyphenolic tannins. Biomaterials 27:3645-3651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jastrzebska M, Zalewska-Rejdak J, Wrzalik R, Kocot A, Mroz I, Barwinski B, et al. (2006). Tannic acid-stabilized pericardium tissue: IR spectroscopy, atomic force microscopy, and dielectric spectroscopy investigations. J Biomed Mater Res A 78:148-156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koide T, Daito M. (1997). Effects of various collagen crosslinking techniques on mechanical properties of collagen film. Dent Mater J 16:1-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku CS, Sathishkumar M, Mun SP. (2007). Binding affinity of proanthocyanidin from waste Pinus radiata bark onto proline-rich bovine Achilles tendon collagen type I. Chemosphere 67:1618-1627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linde A. (1989). Dentin matrix proteins: composition and possible functions in calcification. Anat Rec 224:154-166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mjör IA. (1997). The reasons for replacement and the age of failed restorations in general dental practice. Acta Odontol Scand 55:58-63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mjör IA, Moorhead JE, Dahl JE. (2000). Reasons for replacement of restorations in permanent teeth in general dental practice. Int Dent J 50:361-366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natsir N, Wakasa K, Yoshida Y, Satou N, Shintani H. (1999). Effect of tannic acid solution on collagen structures for dental restoration. J Mater Sci Mater Med 10:489-492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto Y, Heeley JD, Dogon IL, Shintani H. (1991). Effects of phosphoric acid and tannic acid on dentine collagen. J Oral Rehabil 18:507-512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prati C, Montanari G, Biagini G, Fava F, Pashley DH. (1992). Effects of dentin surface treatments on the shear bond strength of Vitrabond. Dent Mater 8:21-26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbak SA, Hassanin MB. (1998). A scanning electron microscopic study of tooth surface changes induced by tannic acid. J Prosthet Dent 79:169-174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarrett DC. (2005). Clinical challenges and the relevance of materials testing for posterior composite restorations. Dent Mater 21:9-20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JE. (1995). Extracellular matrix, supramolecular organisation and shape. J Anat 187(Pt 2):259-269 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung HW, Chang Y, Chiu CT, Chen CN, Liang HC. (1999). Crosslinking characteristics and mechanical properties of a bovine pericardium fixed with a naturally occurring crosslinking agent. J Biomed Mater Res 47:116-126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomiyama K, Mukai Y, Okada S, Negishi H, Fujihara T, Kawase T, et al. (2004). Durability of FTLA treatment as a medicament for dentin hypersensitivity—abrasion resistance and profiles of fluoride release. Dent Mater J 23:585-592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi M. (2000). Collagen biochemistry: an overview. Advances in tissue banking. Vol. 6 Phillips GO, editor. New Jersey: World Scientific Publishing Co, pp. 455-500 [Google Scholar]