Abstract

Background

Obesity management requires understanding of the mortality risks associated with different adiposity measures.

Study Design

Prospective cohort

Setting and Participants

5,805 adults with BMI ≥ 18.5 and stage 1–4 CKD defined by a spot urine albumin-creatinine ratio ≥ 30 mg/g and/or an estimated glomerular filtration rate < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 enrolled in the REasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study

Predictor

Body mass index (BMI) in kg/m2 categorized as 18.5–24.9, 25.0–29.9, 30.0–34.9, 35.0–39.9 and ≥ 40 kg/m2 and waist circumference categorized as < 80, 80–87.9, 88–97.9, 98–107.9, and ≥ 108 cm in women and < 94, 94–101.9, 102–111.9, 112–121.9, and ≥122 cm in men.

Outcomes

All cause mortality

Measurements

BMI and WC were measured using a standardized protocol during the home visit.

Results

A total of 686 deaths (11.8%) occurred during a median follow-up of 4 years. Compared to the referent BMI category 25–29.9 kg/m2, hazard ratios for mortality were 1.27 (95% CI, 0.96–1.69) for BMI < 25 kg/m2, and 0.84 (95% CI, 0.62–1.13), 0.81 (0.52–1.26) and 0.95 (95% CI, 0.54–1.65) for BMI categories 30–34.9, 35–39.9 and ≥ 40 kg/m2, respectively, after adjustment for covariates including waist circumference. In contrast, after adjustment for covariates including BMI, higher mortality rates were noted for all waist circumference categories compared to the referent (< 80 cm in women and < 94 cm in men) with hazard ratios 1.04 (95% CI, 0.77–1.41) for waist circumference 80–87.9 in women and 94–101.9 in men, 1.29 (95% CI, 0.92–1.81) for waist circumference 88–97.9 in women and 102–111.9 in men, 1.72 (95% CI, 1.12–2.62) for waist circumference 98–107.9 in women and 112–121.9 in men, and 2.09 (95% CI, 1.26–3.46) for waist circumference ≥ 108 in women and ≥ 122 in men.

Limitations

BMI and waist circumference measured at baseline only.

Conclusions

waist circumference should be considered in conjunction with BMI when assessing mortality risk associated with obesity in adults with CKD.

Keywords: Obesity, waist circumference, mortality, chronic kidney disease

Overweight and obesity are associated with excess mortality from diabetes and kidney disease in the U.S. population.1 Studies which examined the association between body mass index (BMI) and cardiovascular events or mortality in adults with stages 1–4 CKD have found either null or inverse associations, similar to most studies which focused on adults receiving dialysis.2–4 However, these investigations did not examine abdominal adiposity and recent data suggest an interaction between BMI and waist circumference on mortality risk among adults receiving dialysis.5, 6 Obesity may be measured several ways such as weight per unit of height (body mass index or BMI), waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio or with direct measures of total body fat. The standard for diagnosing and staging of obesity in the general population remains defined by BMI. However, BMI is a function of both muscle mass and peripheral and abdominal adipose tissue yet the abdominal adipose tissue appears to be the main mediator of cardiovascular risk while peripheral adipose tissue and higher muscle mass appears protective. Waist circumference correlates highly with abdominal adiposity7 and may be a better predictor of mortality compared to BMI in adults with CKD who are not receiving dialysis.

Weight reduction may have a role in the management of obese individuals with CKD.8, 9 However, interventions to reduce adiposity require an understanding of the mortality risk associated with different weight-related measures. This study examines the association between measures of adiposity, based on BMI and waist circumference, and mortality among adults with CKD prior to the need for dialysis.

Methods

Participants

The REasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study is a population-based cohort of individuals aged 45 years and older and is designed to identify factors that contribute to the excess stroke mortality in the Southeastern United States and among African Americans.10, 11 The REGARDS cohort is a national sample of community-dwelling individuals, 20.9% of whom reside in the coastal plain of North Carolina (NC), South Carolina (SC), and Georgia (GA), 34.5% in the remainder of NC, SC, and GA and the southeastern states of Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana and Arkansas, and 44.5% in the other 42 contiguous states. There were 30,232 participants recruited into the cohort between January, 2003 and October, 2007.

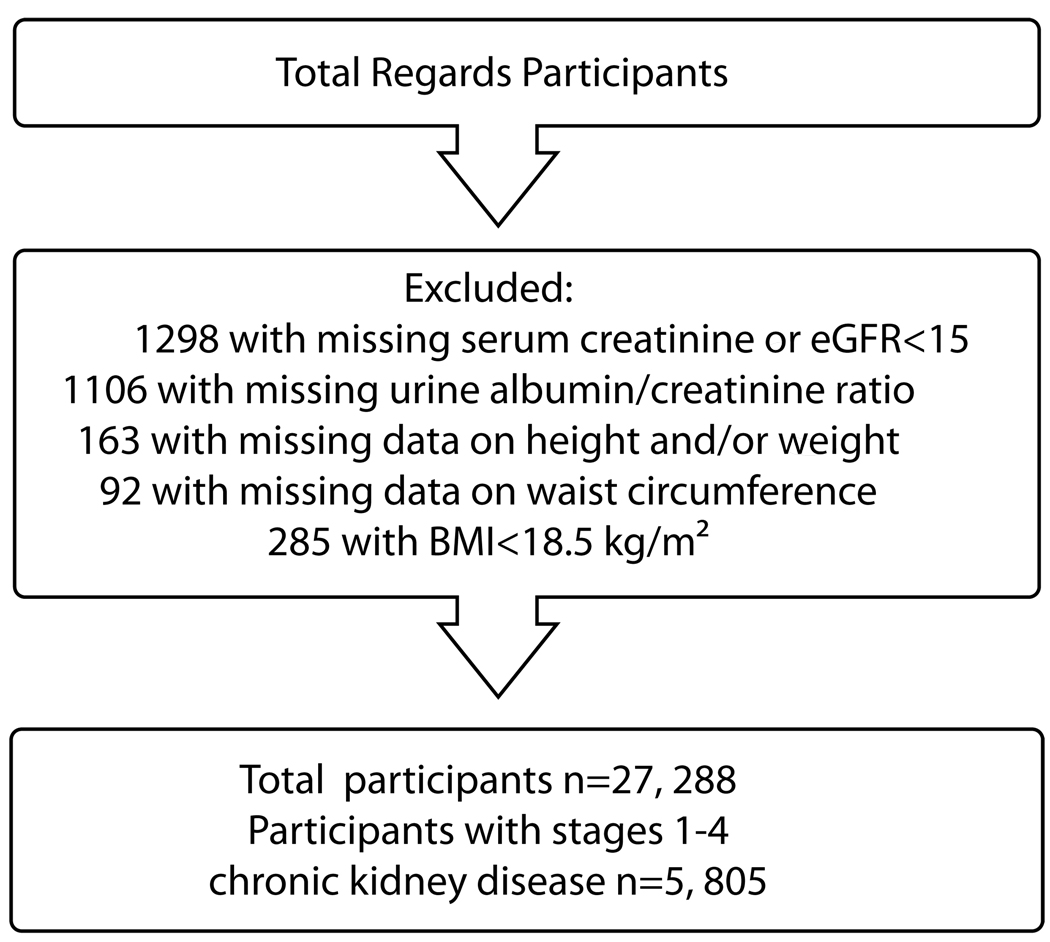

Baseline information on REGARDS participants were collected by trained staff during a preliminary phone interview followed by an in-home physical examination. The physical exam included blood pressure and anthropomorphic measures and collection of a spot urine specimen and phlebotomy. Participants were instructed to fast 10–12 hours prior to the in-home visit. Figure 1 shows the ordered selection of REGARDS participants included in the analyses. We sequentially excluded 1,298 participants with missing serum creatinine or with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <15 ml/min/1.73m2 or who reported treatment for end-stage kidney disease. Further, we excluded 1,106 persons with missing albumin-creatinine ratio measurements, 163 with missing BMI measurements, and 92 with missing waist circumference measurements. Finally, because we were interested in the association between CKD and obesity, we excluded 285 individuals with a BMI < 18.5 kg/m2, defined by the World Health Organization as underweight.12 Among these participants, a total of 5805 participants had CKD as defined below.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of REGARDS Participants for Analyses

Kidney Function

A single serum creatinine, calibrated to an international isotope dilution mass spectroscopic (IDMS)-traceable standard, was measured on each participant by colorimetric reflectance spectrophotometry (Ortho Vitros Clinical Chemistry System 950IRC, Johnson & Johnson Clinical Diagnostics, www.orthochemical.com). Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation.13 Albumin and creatinine were measured in a random spot urine specimen by nephelometry (BN ProSpec Nephelometer, Dade Behring, www.medical.siemens.com) and Modular-P chemistry analyzer (Roche/Hitachi, labsystems.roche.com), respectively. Urine albumin-creatinine ratios (ACR) were calculated in mg/g. Presence of kidney disease was defined according to the NKF's KDOQI CKD stages: stages 1–2 (eGFR ≥ 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 and ACR ≥ 30mg/g) and stages 3–4 (eGFR of 15–59 ml/min/1.73 m2).14

Obesity measures and mortality

Weight, height and waist circumference (in cm) were measured during the in-home visit following a standardized protocol. BMI was calculated as weight (kg)/height(m2). Waist circumference was measured mid-way between the lowest rib and the iliac crest with the subject standing using a tape measure. At six month intervals following enrollment, vital status was ascertained by telephone contact with participants or with contacts provided at recruitment and by online searches of the Social Security Administrations’ Death Master File (ssdi.rootsweb.ancestry.com). The majority of deaths were verified thru online searches and less than 20% were identified thru proxy contact alone.15 Failed attempts to contact a study participant were followed by phone interviews with alternative contacts which were provided by participants at baseline and updated at each phone contact.

Covariates

We obtained information on physician diagnosis of major co-morbid conditions (coronary artery disease, stroke, cancer, hypertension and diabetes) by self-report during a computer assisted telephone interview. Participants were asked about smoking status, education, family income, and health insurance status. Hypertension was defined as either self-reported use of antihypertensive medications or a SBP ≥ 140 mm Hg or a DBP ≥ 90 mm Hg measured during the home examination, where SBP and DBP were the average of two measures taken in the seated position. We defined diabetes as a fasting glucose ≥126, or a non-fasting glucose ≥200 or current use of either oral hypoglycemic pills or insulin.

Statistical Analysis

Categories of BMI were created based on the World Health Organization classification scheme: 18.5–24.9 kg/m2; 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 (referent group), 30.0–34.9 kg/m2, 35.0–39.9 kg/m2 and ≥ 40.0 kg/m2.12, 16 Waist circumference categories were created after stratifying participants by sex and were based on the WHO diagnosis of abdominal obesity12, 16 with 4 separate categories similar to BMI: < 88 cm in women and < 102 cm in men (referent group), 80–87.9 cm in women and 94–101.9 cm in men, 88–97.9 cm in women and 102–111.9 cm in men, 98–107.9 cm in women and 112–121.9 cm in men, and ≥ 108 cm in women and ≥ 122 cm in men.

Baseline characteristics were compared by BMI and waist circumference categories using ANOVA and χ2 tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively and overall P values are reported. Kaplan-Meier curves were constructed to estimate the survival probabilities for all-cause mortality by BMI and waist circumference categories. Cox’s Proportional Hazards models were used to estimate the association between measures of obesity and all-cause mortality. The assumptions of the Cox proportional hazards models were examined by plotting the natural log of the cumulative hazard of all cause mortality by the natural log of time. Several proportional hazards models were created to examine the effects of adjustment for covariates. Model 1 adjusted for age, gender and race. Model 2 added the albumin-creatinine ratio (log transformed), eGFR, systolic blood pressure, presence of co-morbid conditions (coronary heart disease, stroke, hypertension and diabetes), smoking status, high density lipoproteins (HDL) and low density lipoproteins (LDL), educational attainment, family income, health insurance status, and access to health care to Model 1. Age, log transformed urine albumin-creatinine ratio, eGFR, systolic blood pressure and HDL and LDL were fitted in the model as continuous variables. To explore potential confounding by body composition, models were also constructed to examine the combined effects of BMI and waist circumference on time to death. Model 3 mutually adjusted for BMI and waist circumference in addition to all of the covariates in Model 2.

We also examined BMI and waist circumference as linear predictors of mortality by fitting both BMI and waist circumference in the model as continuous variables. Interactions between BMI and waist circumference on their respective associations with mortality were examined using Cox proportional hazards models. Effect modification by CKD stage (stages 1–2 and stages 3–4) was explored by placing interaction terms in separate models with BMI or waist circumference as the independent predictor of mortality and adjusting for all covariates. To illustrate the interaction between BMI on the association between waist circumference and all-cause mortality, adjusted hazard ratios (model 2) by waist circumference categories were plotted against BMI as a continuous variable. Due to the strong confounding effects of cigarette smoking and pre-existing disease on the associations between adiposity measures and mortality, analyses were repeated after excluding all current smokers and also after excluding participants who died during the first year of follow-up.

Results

Among the 27,288 REGARDS participants meeting the inclusion criteria, 5,805 (21.7%) were defined as having CKD and included in the analyses. Stage 1–2 CKD was present in 2,922 (50.3%), stage 3–4 in 2,883 (49.7%). Characteristics of participants by BMI and waist circumference categories are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Participants in the highest BMI category were younger and more likely to be female and African-American compared to the lower BMI categories. In addition, this group was less likely to have a history of prior stroke, coronary heart disease or cancer or be a current smoker compared to the lower BMI categories. Participants in the highest waist circumference category were also younger and more likely to be female and African-American compared to the lower waist circumference categories. However, the prevalence of prior stroke, coronary heart disease and cancer were fairly similar across the waist circumference categories.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population by BMI Categories

| BMI Categories in kg/m2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | 18.5–24.9 | 25.0–29.9 | 30.0–34.9 | 35.0–39.9 | ≥ 40 |

| No.** | 1250 (21.5) | 2023 (34.8) | 1364 (23.5) | 714 (12.3) | 454 (7.8) |

| Age (Years) | 72.4 +/− 9.8 | 70.3 +/− 9.2 | 76.8 +/− 9.1 | 65.3 +/− 8.8 | 63.2 +/− 8.4 |

| % Male | 48.3 | 55.0 | 47.6 | 40.1 | 28.2* |

| % African-American | 34.2 | 42.0 | 51.9 | 56.9 | 63.7* |

| Waist Circumference | |||||

| Men (cm) | 88.2 +/− 8.8 | 97.6 +/− 7.6 | 107.4 +/− 8.0 | 119.3 +/− 9.5 | 131.0 +/− 11.6 |

| Women (cm) | 77.1 +/− 8.4 | 88.2 +/− 8.7 | 98.4 +/− 9.4 | 107.2 +/− 9.8 | 119.0 +/− 12.7 |

| % Diabetes | 18.8 | 32.3 | 45.2 | 57.3 | 58.8* |

| % Hypertension | 68.7 | 76.0 | 82.2 | 85.7 | 88.1* |

| % Prior Stroke | 12.4 | 10.8 | 10.0 | 11.2 | 9.5 |

| % Coronary Disease | 31.9 | 32.5 | 33.0 | 32.5 | 24.7 |

| % Cancer | 18.1 | 19.7 | 18.8 | 13.8 | 12.2* |

| % Current smoker | 21.4 | 14.2 | 13.6 | 11.8 | 10.9* |

| % Stroke Belt | 31.8 | 33. | 34.2 | 34.6 | 33.7 |

| % Stroke Buckle | 23.3 | 18.9 | 20.2 | 20.7 | 24.0 |

| % Income <$20,000/year | 25.7 | 24.8 | 28.2 | 29.6 | 40.0* |

| % < High School | 15.5 | 16.8 | 19.0 | 18.9 | 22.5* |

| % No health insurance | 4.8 | 4.6 | 5.6 | 8.3 | 8.8* |

| CKD | |||||

| % Stages 1–2 | 47.2 | 46.0 | 52.9 | 58.5 | 57.5* |

| % Stages 3–4 | 52.8 | 54.0 | 47.1 | 41.5 | 42.5 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 130.1 +/− 19.9 | 132.4 +/− 18.6 | 133.7 +/− 17.9 | 134.7 +/− 19.2 | 136.2 +/− 18.2 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 66.1 +/− 23.4 | 66.4 +/− 24.1 | 69.2 +/− 24.7 | 73.4 +/− 26.6 | 74.0 +/− 28.8 |

| ACR (mg/g) | 3.7 +/− 1.6 | 3.7 +/− 1.6 | 3.9 +/− 1.6 | 4.1 +/− 1.6 | 4.1 +/− 1.7 |

| Serum albumin (g/dl) | 4.1 +/− 0.4 | 4.2 +/− 0.3 | 4.1 +/− 0.4 | 4.1 +/− 0.3 | 4.0 +/− 0.3 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 13.3 +/− 1.6 | 13.4 +/− 1.6 | 13.3 +/− 1.6 | 13.2 +/− 1.6 | 12.8 +/− 1.7 |

| HDL(mg/dl) | 55.1 +/− 18.1 | 48.8 +/− 15.7 | 47.4 +/− 14.9 | 46.8 +/− 14.8 | 47.5 +/− 14.2 |

| LDL (mg/dl) | 107.7 +/− 35.1 | 111.2 +/− 36.5 | 110.5 +/− 35.6 | 109.5 +/− 36.4 | 110.7 +/− 34.6 |

Note: Continuous data shown as mean +/− standard deviation, categorical data as percentage

p<0.001; +Ln(ACR)

values given in parentheses are percentages

BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; ACR, albumin-creatinine ratio; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; SBP, systolic blood pressure

Conversion factors for units: eGFR in ml/min/1.73 m2 to ml/s/1.73 m2; serum albumin and hemoglobin in g/dL to g/L, x10; LDL and HDL in mg/dL to mmol/L, x0.02586.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population by Sex Specific Waist Circumference Categories

| Sex Specific Waist Circumference Categories in cm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | < 80 (♀); < 94 (♂) |

80–87.9(♀); 94– 101.9 (♂) |

88–97.9 (♀); 102– 111.9 (♂) |

98–107.9(♀); 112– 121.9 (♂) |

≥ 108(♀); ≥ 122 (♂) |

| No.** | 1281 (15.8%) | 1224 (27.4%) | 1386 (23.9%) | 997 (17.2%) | 917 (15.8%) |

| Age (Years) | 70.8 +/− 10.0 | 70.3 +/− 9.4 | 69.4 +/− 9.2 | 67.7 +/− 9.5 | 65.4 +/− 8.8 |

| % Male | 62.9 | 58.4 | 46.8 | 36.8 | 26.5* |

| % African-American | 37.3 | 40.8 | 45.2 | 52.7 | 60.1* |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||

| Men | 24.7 +/− 2.8 | 27.9 +/− 2.7 | 30.6 +/− 3.0 | 34.1 +/− 3.6 | 39.3 +/− 6.3 |

| Women | 23.4 +/− 2.8 | 26.6 +/− 3.1 | 29.7 +/− 3.7 | 33.6 +/− 4.5 | 39.7 +/− 6.3 |

| % Diabetes | 20.9 | 27.6 | 37.4 | 46.3 | 61.5* |

| % Hypertension | 69.3 | 74.7 | 79.5 | 83.3 | 87.0* |

| % Prior Stroke | 11.2 | 10.8 | 9.5 | 11.0 | 12.7 |

| % Coronary Disease | 30.7 | 32.5 | 32.4 | 33.6 | 30.1 |

| % Cancer | 17.3 | 20.8 | 20.2 | 16.5 | 12.9 |

| % Current smoker | 16.7 | 15.0 | 15.9 | 14.3 | 12.3 |

| % Stroke Belt | 30.9 | 33.2 | 33.4 | 37.2 | 33.4 |

| % Stroke Buckle | 22.7 | 18.6 | 18.8 | 22.0 | 21.5 |

| % Income <$20,000/year | 22.7 | 23.4 | 27.3 | 28.4 | 39.2* |

| % < High School | 15.1 | 14.3 | 19.6 | 17.2 | 24.0* |

| % No health insurance | 5.6 | 4.2 | 4.6 | 6.7 | 8.1* |

| CKD | |||||

| %Stages 1–2 | 50.0 | 47.6 | 47.8 | 52.2 | 56.6* |

| %Stages 3–4 | 50.0 | 52.4 | 52.2 | 47.8 | 43.4 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 130.4 +/− 19.0 | 131.7 +/− 18.4 | 133.1 +/− 18.6 | 133.7 +/− 18.7 | 136.0* +/− 19.3 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 67.5 +/− 23.2 | 67.2 +/− 24.0 | 66.8 +/− 24.6 | 69.8 +/− 26.0 | 72.3* +/− 27.4 |

| ACR (mg/g) | 3.8 +/− 1.58 | 3.7 +/− 1.56 | 3.8 +/− 1.62 | 3.9 +/− 1.62 | 4.1* +/− 1.62 |

| Serum albumin (g/dl) | 4.2 +/− 0.36 | 4.2 +/− 0.35 | 4.1 +/− 0.34 | 4.1 +/− 0.36 | 4.0* +/− 0.34 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 13.5 +/− 1.6 | 13.5 +/− 1.6 | 13.4 +/− 1.6 | 13.0 +/− 1.6 | 12.9* +/− 1.6 |

| HDL (mg/dl) | 53.9 +/− 17.9 | 49.1 +/− 16.4 | 47.8 +/− 15.0 | 48.3 +/− 14.6 | 47.5* +/− 15.1 |

| LDL (mg/dl) | 107.9 +/− 34.2 | 111.2 +/− 37.2 | 112.0 +/− 36.0 | 109.8 +/− 36.2 | 109.1 +/− 35.5 |

Note: Continuous data shown as mean +/− standard deviation, categorical data as percentage

p<0.001; +Ln(ACR)

values given in parentheses are percentages

BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; ACR, albumin-creatinine ratio; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; SBP, systolic blood pressure

Conversion factors for units: eGFR in ml/min/1.73 m2 to ml/s/1.73 m2; serum albumin and hemoglobin in g/dL to g/L, x10; LDL and HDL in mg/dL to mmol/L, x0.02586.

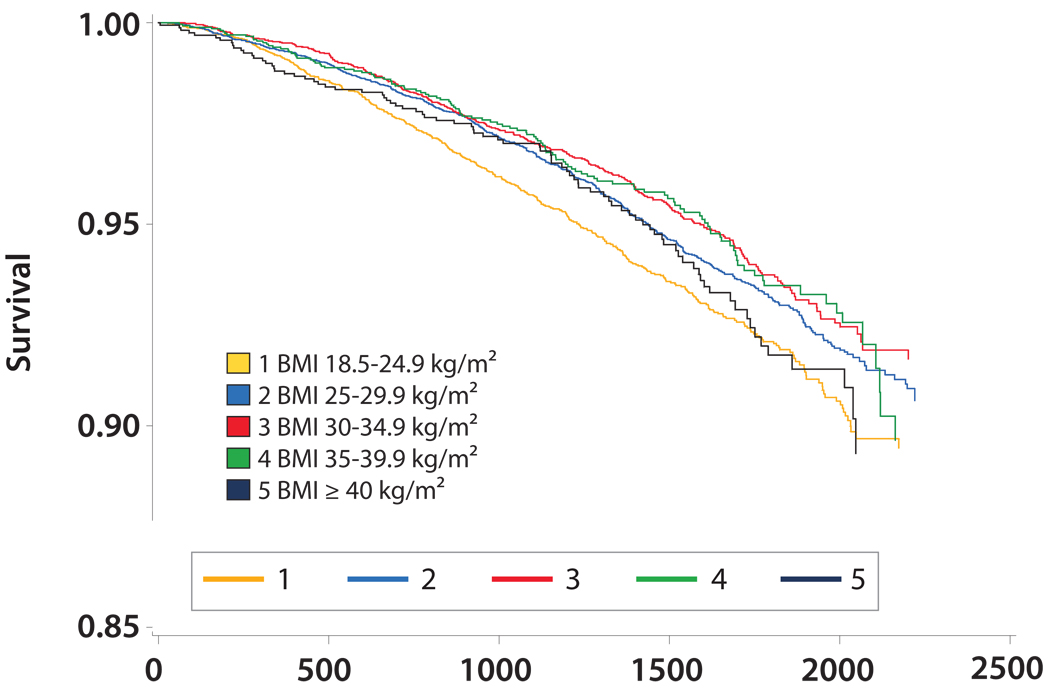

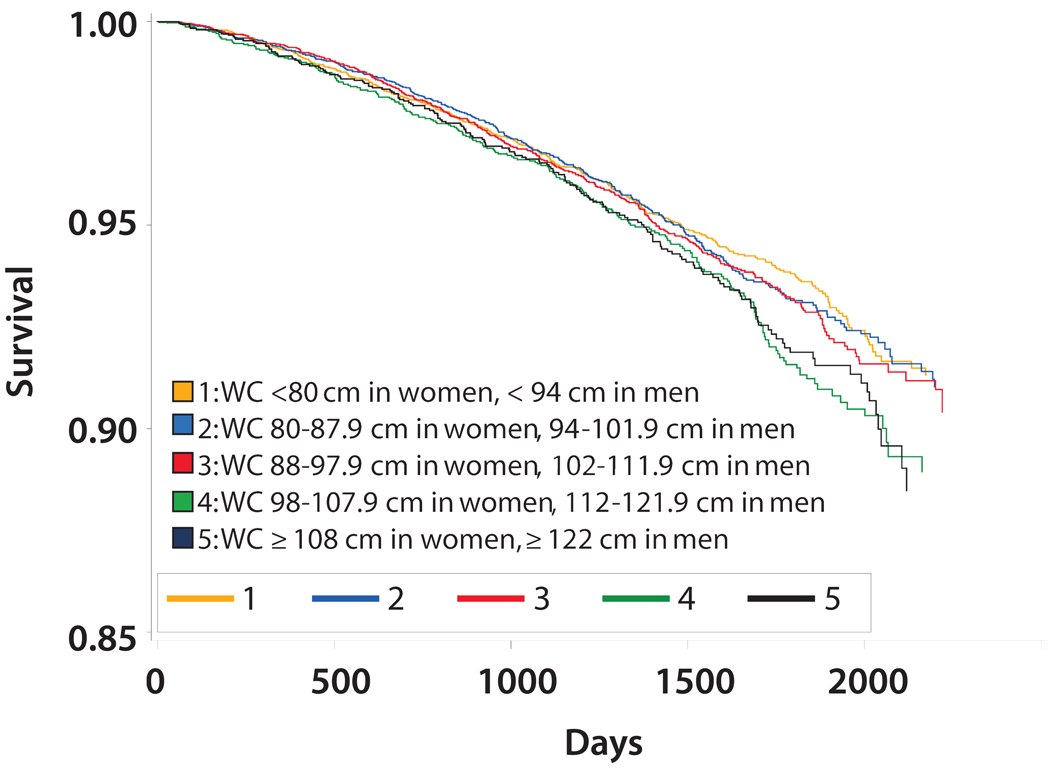

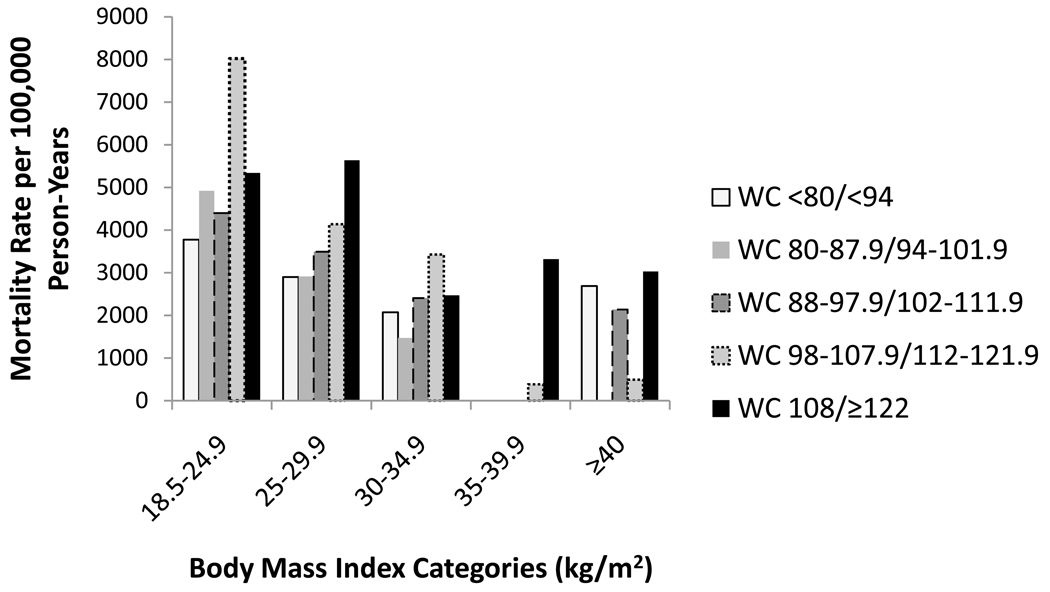

Overall, 686 deaths (11.8%) occurred during a median follow-up of 4.0 years. The mean BMI was lower among participants with CKD who died compared to surviving participants (29.2 kg/m2 +/− 6.2 vs. 30.3 kg/m2 +/− 6.5; p<0.05). In contrast, mean waist circumference was higher among participants with CKD who died compared to individuals with CKD who survived (101.9 cm +/− 15.8 vs. 99.2 cm +/− 15.6; p<0.05). Figures 2 and 3 show Kaplan-Meier curves demonstrating overall survival by BMI and waist circumference categories, respectively. Overall survival was lowest with BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 (Figure 2) while overall survival appeared lowest among waist circumference categories ≥ 98 cm in women and ≥ 112 cm in men (Figure 3). Figure 4 shows mortality rates for the five BMI categories by waist circumference categories. The highest mortality rates per 100,000 person-years were noted in BMI categories < 30 kg/m2. Within these BMI categories, mortality rates were generally higher among participants in the upper waist circumference categories.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier Curve for Overall Survival by BMI Categories

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier Curve for Overall Survival by Waist Circumference (WC) Categories

Figure 4.

Distribution of Mortality Rates per 100,000 Person-years by BMI (kg/m2) and Sex Specific (Women/Men) Waist Circumference (WC) Categories

Table 3 shows the adjusted hazard ratios for all-cause mortality by BMI categories. After adjustment for age, sex and race, both the lowest (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) and highest BMI category (≥40 kg/m2) were associated with a significantly increased hazard rate of mortality compared to the referent category (BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2). After further adjustment for all covariates including waist circumference, the lowest BMI category was associated with a higher hazard rate of mortality compared to the referent group (HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 0.96–1.69) but the 95% confidence interval included 1.00. In contrast, all BMI categories with BMI ≥ 30.0 kg/m2 were associated with reduced hazard rates of mortality compared to the referent group, with all 95% confidence intervals including 1.00.

Table 3.

Mortality among Participants with Baseline Stages 1–4 CKD by BMI Categories

| HR(95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI Categories | Number (%) | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

| 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 | 1250 (21.5%) | 1.25 (1.03–1.51) | 1.13 (0.89–1.44) | 1.27(0.96–1.69) |

| 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 | 2023 (34.8%) | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) |

| 30.0–34.9 kg/m2 | 1364 (23.5%) | 0.97 (0.78–1.20) | 1.07 (0.82–1.38) | 0.84 (0.62–1.13) |

| 35.0–39.9 kg/m2 | 714 (12.3%) | 1.21 (0.93–1.59) | 1.25 (0.88–1.77) | 0.81 (0.52–1.26) |

| ≥ 40.0 kg/m2 | 454 (7.8%) | 1.44 (1.03–2.00) | 1.58 (1.03–2.43) | 0.95 (0.54–1.65) |

Model 1 adjusts for age, sex and race.

Model 2 extends Model 1 to include CKD stage and co-morbidities (coronary heart disease, stroke, cancer, hypertension and diabetes), smoking status, educational attainment, household income, health insurance, urine albumin/creatinine ratio, estimated glomerular filtration, systolic blood pressure, HDL and LDL.

Model 3 extends Model 2 to mutually adjust for BMI and waist circumference in all models

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio

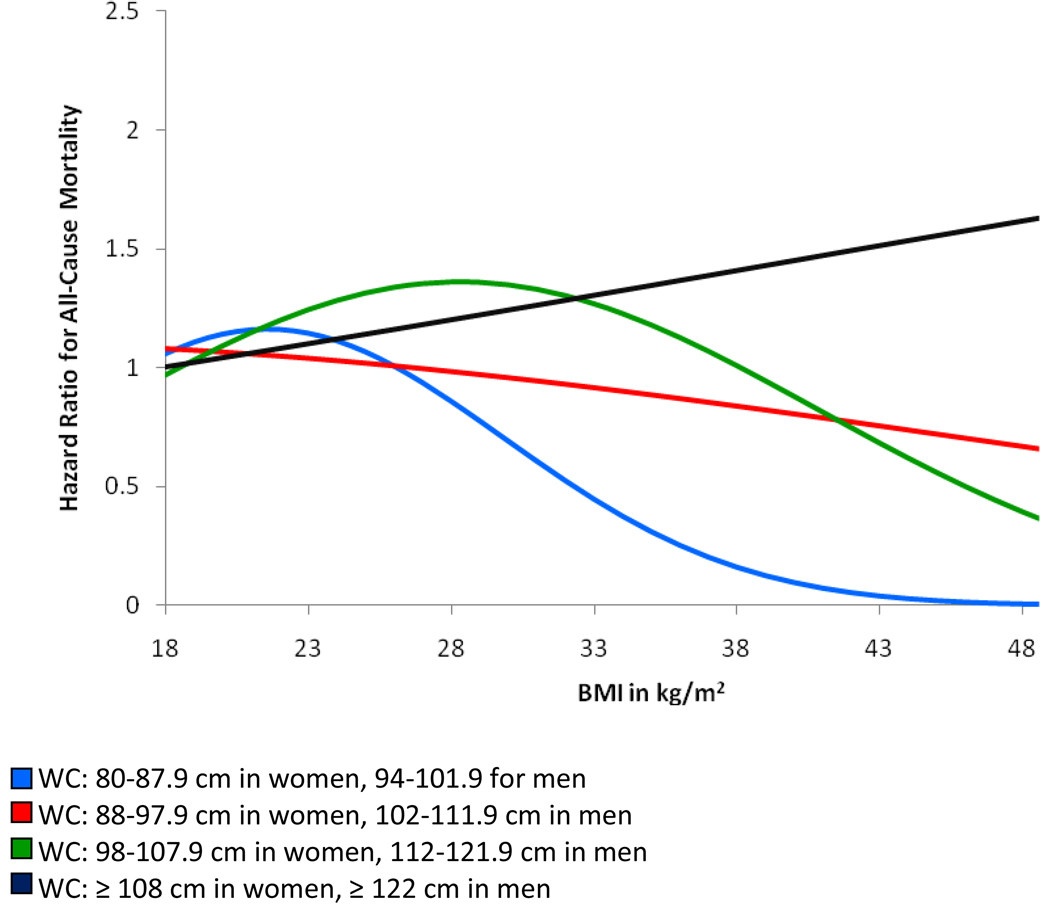

The association between waist circumference and all-cause mortality was fairly linear and hazard rates of mortality were significantly higher for waist circumference categories ≥ 98 cm in women and ≥ 112 cm in men compared to the referent waist circumference category (< 80 cm in women and < 94 cm in men) after adjustment for age, sex and race (Table 4). Adjustment for all covariates including BMI strengthened these associations with an approximate two-fold increased hazard rate for all-cause mortality noted for waist circumference categories ≥ 108 cm in women and ≥ 122 cm in men (HR, 2.09; 95% CI, 1.26–3.46) compared to the referent waist circumference category. Figure 5 shows the association between waist circumference categories and all-cause mortality across the spectrum of BMI. Compared to the referent waist circumference category (< 80 cm in women and < 94 cm in men), the hazard rate of mortality for the highest waist circumference category (≥ 108 cm in women and ≥ 122 cm in men) increased linearly across the BMI continuum. Hazard ratios for all-cause mortality were lowest for waist circumference categories 80–107.9 cm in women and 94–121.9 cm in men at the far right end of the BMI distribution compared to the waist circumference referent category.

Table 4.

Mortality among Participants with Baseline Stages 1–4 CKD by Waist Circumference Categories

| HR (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| waist circumference Category |

Number (%) | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

| < 80 cm (⍰); < 94 cm (♂) | 914 (15.8%) | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) |

| 80–87.9 cm (♀); 94–101.9 cm (♂) | 1591 (27.4%) | 1.02 (0.81–1.30) | 0.93 (0.71–1.23) | 1.04 (0.77–1.41) |

| 88–97.9 cm (♀); 102–111.9 cm (♂) | 1386 (23.9%) | 1.04 (0.81–1.35) | 1.05 (0.80–1.39) | 1.29 (0.92–1.81) |

| 98–107.9 cm (♀); 112–121.9 cm (♂) | 997 (17.2%) | 1.46 (1.12–1.90) | 1.27 (0.93–1.74) | 1.72 (1.12–2.62) |

| ≥ 108 cm (♀); ≥ 122 cm (♂) | 917 (15.8%) | 1.58 (1.18–2.10) | 1.57 (1.12–2.21) | 2.09 (1.26–3.46) |

Model 1 adjusts for age, sex and race.

Model 2 extends Model 1 to include CKD stage and co-morbidities (coronary heart disease, stroke, cancer, hypertension and diabetes), smoking status, educational attainment, household income, health insurance, urine albumin/creatinine ratio, estimated glomerular filtration, systolic blood pressure and HDL and LDL.

Model 3 extends Model 2 to mutually adjust for BMI and waist circumference in all models

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio

Figure 5.

Hazard Ratios for All-Cause Mortality by Waist Circumference (WC) Categories Across the Spectrum of BMI with Referent WC Category WC < 80 cm in Women and < 94 cm in Men

No interactions were noted by CKD stages on the associations between BMI and all-cause mortality or between waist circumference and all-cause mortality in fully adjusted models. In sensitivity analyses, the exclusion of participants who died during the first year showed very similar results. Furthermore, limiting the analyses to non-smoking participants did not substantially change the associations between BMI and mortality but associations between waist circumference categories and all-cause mortality were strengthened (data not shown). In the full adjusted model which included both BMI and waist circumference as continuous variables, each 1-cm increase in waist circumference was associated with a 2% increased mortality risk (95% CI, 1.01–1.04), every 1-kg/m2 increase in BMI was associated with a 3% decreased mortality risk (95% CI, 0.94–0.99).

Discussion

This study demonstrates substantial differences in the association between BMI and waist circumference and all-cause mortality in adults with CKD. Consistent with previous studies in older adults or adults with co-morbid conditions including stage 5 CKD,3, 6, 17, 18 BMI < 25 kg/m2 was associated with an increased hazard ratio of mortality compared to BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2. We noted that further adjustment for waist circumference led to a reduced risk of mortality among BMI categories ≥ 30 kg/m2 compared to a BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2. In contrast, a graded and increased mortality risk was noted across increasing waist circumference categories after adjustment for BMI and other covariates.

The current findings are supported by several prior studies which examined the effects of obesity measures on mortality risk with mutual adjustment for BMI and waist circumference in older populations.17–19 In the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS), which followed 5200 men and women aged 65 years and older for over 9 years, BMI was inversely associated with mortality risk after adjustment for waist circumference while the opposite was noted for waist circumference after adjustment for BMI and all other covariates.17 Mortality risk associated with waist circumference in adults with CKD was examined using pooled data from participants of the Atherosclerosis in Communities (ARIC) and CHS studies with stage 3–4 CKD (1,669 individuals total). Risk of cardiac events (myocardial infarction or cardiovascular death) after an average of 9.3 years of follow-up was 36% (95% CI, 1.02–1.85) higher among individuals with the largest waist-to-hip ratio (≥ 1.02 and 0.96 in men and women, respectively) compared to the group with the lowest waist/hip ratio (≤ 0.95 and 0.87 in men and women, respectively).20 In contrast, no significant association was present between overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2) or obesity (≥30 kg/m2) and cardiac events when compared to BMI 20–24.9 kg/m2. Our findings are also consistent with a study by the Calabria Registry of Dialysis and Transplantation Working Group that examined both waist circumference and BMI as predictors of mortality among 537 patients receiving dialysis.6 In this study, BMI was inversely associated with reduced all-cause mortality while a linear and direct association was noted between waist circumference and all-cause mortality. After adjustment for BMI and other covariates, every 10 cm increase in waist circumference was associated with a 23% (95% CI, 1.02–1.47) increase in all-cause mortality. In contrast, every 1 kg/m2 increase in BMI was associated with an 11% decrease in mortality after adjustment for waist circumference and covariates. Similar findings were noted for cardiovascular mortality.6

Clinical guidelines have previously suggested that both BMI and waist circumference should be considered when assessing a patient’s risk for adiposity-related disease.21 Thus, the findings of this study support previous recommendations for assessment of obesity and its associated cardiovascular risk. Caution should be made when interpreting the observation that a higher BMI is associated with a reduced mortality risk compared to a lower or “ideal” BMI within a population given the absence of information on waist circumference, especially since waist circumference may be elevated among adults within an ideal range of BMI. In the general population, abdominal obesity (a waist circumference > 88 cm in women and > 102 cm in men), is strongly associated with multiple cardiovascular risk factors including hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia among adults with BMI < 35 kg/m2.22, 23

As no significant interaction was noted between BMI or waist circumference and CKD stages, it should be noted that classification of CKD stages 1–2 was based on urine albumin and creatinine values measured in a single spot urine sample. Approximately 1/3 of adults with microalbuminuria measured in one spot urine sample will not have microalbuminuria in a repeated sample.14 Thus, misclassification of CKD stages 1–2 is likely. In addition, the follow-up period for this study was less than 5 years and may have been too short to adequately assess mortality risk among a low risk group such as adults with CKD stages 1–2 where mortality risk was approximately half the risk among adults with stages 3–4 CKD. In addition, we did not have information on cause of death and events were limited to all-cause mortality. The strengths of this study include a very large cohort of adults with CKD with a diversity of socioeconomic backgrounds. The REGARDS study was limited to black and white race/ethnicity and additional studies are needed to investigate associations between body composition and mortality in other racial/ethnic groups with CKD. Although waist circumference does correlate highly with abdominal fat in adults with CKD,7 another limitation of this study is the lack of direct measures of body composition.

In conclusion, among adults with CKD, BMI by itself may not be a useful measure to determine mortality risks associated with adiposity because it reflects multiple components. Some of these components are directly associated with increased risk of mortality (abdominal adiposity) and other components are not (muscle mass). In contrast, waist circumference reflects abdominal adiposity alone and may be a useful measure to determine mortality risk associated with obesity in adults with CKD, especially when used in conjunction with BMI.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the participating investigators and institutions for their valuable contributions: The University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama (Study PI, Statistical and Data Coordinating Center, Survey Research Unit): George Howard DrPH, Leslie McClure PhD, Virginia Howard PhD, Libby Wagner MA, Virginia Wadley PhD, Rodney Go PhD, Monika Safford MD, Ella Temple PhD, Margaret Stewart MSPH, J. David Rhodes BSN; University of Vermont (Central Laboratory): Mary Cushman MD; Wake Forest University (ECG Reading Center): Ron Prineas MD, PhD; Alabama Neurological Institute (Stroke Validation Center, Medical Monitoring): Camilo Gomez MD, Susana Bowling MD; University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (Survey Methodology): LeaVonne Pulley PhD; University of Cincinnati (Clinical Neuroepidemiology): Brett Kissela MD, Dawn Kleindorfer MD; Examination Management Services, Incorporated (In-Person Visits): Andra Graham; Medical University of South Carolina (Migration Analysis Center): Daniel Lackland DrPH; Indiana University School of Medicine (Neuropsychology Center): Frederick Unverzagt PhD; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health (funding agency): Claudia Moy Ph.D.

Support: This research project is supported by a cooperative agreement U01 NS041588 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke or the National Institutes of Health. Representatives of the funding agency have been involved in the review of the manuscript but not directly involved in the collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data. Additional funding was provided by an investigator-initiated grant-in-aid from Amgen Corporation. Amgen did not have any role in the design and conduct of the study, the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or the preparation or approval of the manuscript. The manuscript was sent to Amgen for review prior to submission for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data were presented in a poster at the American Society of Nephrology meeting October 30, 2009, San Diego, California (H Kramer).

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Flegal KM, Graubard BI, Williamson DF, Gail MH. Cause-specific excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity. JAMA. 2007;298(17):2028–2037. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.17.2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kuwae N, Wu DY, et al. Associations of body fat and its changes over time with quality of life and prospective mortality in hemodialysis patients. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(2):202–210. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johansen KL, Young B, Kaysen GA, Chertow GM. Association of body size with outcomes among patients beginning dialysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(2):324–332. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leavey SF, McCullough K, Hecking E, Goodkin D, Port FK, Young EW. Body mass index and mortality in 'healthier' as compared with 'sicker' haemodialysis patients: Results from the dialysis outcomes and practice patterns study (DOPPS) Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16(12):2386–2394. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.12.2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zoccali C. The obesity epidemics in ESRD: From wasting to waist? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(2):376–380. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Postorino M, Marino C, Tripepi G, Zoccali C CREDIT (Calabria Registry of Dialysis and Transplantation) Working Group. Abdominal obesity and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in end-stage renal disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(15):1265–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanches FM, Avesani CM, Kamimura MA, et al. Waist circumference and visceral fat in CKD: A cross-sectional study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52(1):66–73. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kramer H, Tuttle KR, Leehey D, et al. Obesity management in adults with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(1):151–165. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuttle KR, Sunwold D, Kramer H. Can comprehensive lifestyle change alter the course of chronic kidney disease? Semin Nephrol. 2009;29(5):512–523. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howard VJ, Cushman M, Pulley L, et al. The reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study: Objectives and design. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25(3):135–143. doi: 10.1159/000086678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warnock DG, McClellan W, McClure LA, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and anemia among participants in the reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke (REGARDS) cohort study: Baseline results. Kidney Int. 2005;68(4):1427–1431. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2002: Reducing risk, promoting healthy life. 2002

- 13.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification and stratification. Am.J.Kidney Dis. 2002;39:S46–S64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warnock DG, Muntner P, McCollough PA, et al. Kidney function, albuminuria, and all-cause mortality in the REGARDS (reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke) study. Am.J.Kidney Dis. 2010;56(5):861–871. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geneva: World Health Organization; 1998. Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic: Report of a WHO consultation on obesity, geneva, june 3–5, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Ross R. Body mass index is inversely related to mortality in older people after adjustment for waist circumference. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(12):2112–2118. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koster A, Leitzmann MF, Schatzkin A, et al. Waist circumference and mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(12):1465–1475. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bigaard J, Tjonneland A, Thomsen BL, Overvad K, Heitmann BL, Sorensen TI. Waist circumference, BMI, smoking, and mortality in middle-aged men and women. Obes Res. 2003;11(7):895–903. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elsayed EF, Sarnak MJ, Tighiouart H, et al. Waist-to-hip ratio, body mass index, and subsequent kidney disease and death. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52(1):29–38. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.02.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults--the evidence report. national institutes of health. Obes Res. 1998;6 Suppl 2:51S–209S. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=med4&AN=9813653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Ross R. Body mass index, waist circumference, and health risk: Evidence in support of current national institutes of health guidelines. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(18):2074–2079. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.18.2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balkau B, Deanfield JE, Despres JP, et al. International day for the evaluation of abdominal obesity (IDEA): A study of waist circumference, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes mellitus in 168,000 primary care patients in 63 countries. Circulation. 2007;116(17):1942–1951. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.676379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]