Abstract

Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) was identified as a crucial molecule for regulating immune responses, inflammatory processes as well as influencing the cardiovascular system. S1P mediates differentiation, proliferation and migration during vascular development and homoeostasis. S1P is a naturally occurring lipid metabolite and is present in human blood in nanomolar concentrations. S1P is not only involved in physiological but also in pathophysiological processes. Therefore, this complex signalling system is potentially interesting for pharmacological intervention. Modulation of the system might influence inflammatory, angiogenic or vasoregulatory processes. S1P activates G-protein coupled receptors, namely S1P1–5, whereas only S1P1–3 is present in vascular cells. S1P can also act as an intracellular signalling molecule. This review highlights the pharmacological potential of S1P signalling in the vascular system by giving an overview of S1P-mediated processes in endothelial cells (ECs) and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs). After a short summary of S1P metabolism and signalling pathways, the role of S1P in EC and VSMC proliferation and migration, the cause of relaxation and constriction of arterial blood vessels, the protective functions on endothelial apoptosis, as well as the regulatory function in leukocyte adhesion and inflammatory responses are summarized. This is followed by a detailed description of currently known pharmacological agonists and antagonists as new tools for mediating S1P signalling in the vasculature. The variety of effects influenced by S1P provides plenty of therapeutic targets currently under investigation for potential pharmacological intervention.

LINKED ARTICLES

This article is one of a set of reviews submitted to BJP in connection with talks given at the September 2010 meeting of the International Society of Hypertension in Vancouver, Canada. To view the other articles in this collection visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01167.x, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01235.x and http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01366.x

Keywords: atherogenesis, endothelial cell, FTY720, inflammation, lipoproteins, permeability, sphingosine-1-phosphate, vascular smooth muscle cell, vascular tone

Introduction

Lipids are not only major structural cell membrane compounds but also ‘bioactive’ compounds. One group of ‘bioactive lipids’ is the sphingolipids. They are structural components of membranes. In addition, sphingolipids act as potent agonistic signalling molecules on cell-surface G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs). Furthermore, sphingolipids are intracellular signalling molecules. In the past two decades, more and more physiological and pathophysiological processes were reported to be regulated by sphingolipids and many studies were conducted in order to unravel the underlying mechanisms (Fyrst and Saba, 2010). Sphingolipids are a large class of compounds derived from the aliphatic amino alcohol sphingosine. Phosphorylation of sphingosine leads to sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P). S1P induces a large variety of biological responses in different cell types. S1P is detected in both higher and lower organisms. This highlights the functional and structural importance of S1P. There is more and more evidence that S1P might play an interesting role in vascular physiology and pathophysiology. S1P is a potent anti-inflammatory substance and mediates a variety of cellular events such as differentiation, proliferation and migration. These effects are observed in vascular development/maturation and in vascular homoeostasis. S1P plays a crucial role in the development of vascular lesions and progression of atherosclerosis.

The purpose of the current review is to summarize the knowledge of S1P-mediated actions in the vascular system. A better understanding of the vascular effects of S1P should open the possibility for therapeutic intervention in the S1P and S1P receptor system under different vascular disease conditions.

S1P metabolism: generation, degradation, transport and storage

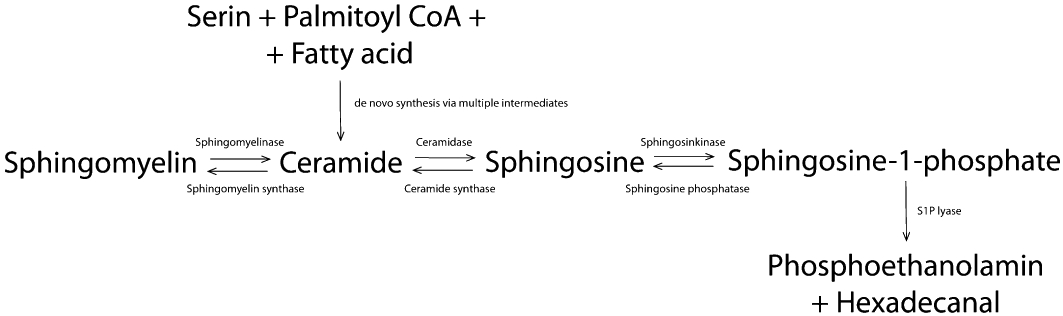

Over 300 different sphingolipids are currently known to exist (Merrill et al., 1993). They have distinct head groups and they all contain a long chain (sphingoid) base backbone. The production of sphingolipids is complex and represents a reversible degradation of sphingomyelin. Here, we just want to summarize important aspects, because several other reviews have already addressed this topic in more extensive detail (Le Stunff et al., 2002; Futerman and Riezman, 2005; Hannun and Obeid, 2008). For the generation of S1P, the catabolism of ceramide is necessary. This could be done by degradation of sphingomyelin by sphingomyelinase leading to ceramide or by de novo synthesis via multiple intermediates starting by Serin, palmitoyl coenzyme A and fatty acids. Ceramide is further converted by enzymatic action of ceramidase resulting in sphingosine. S1P is synthesized through phosphorylation of sphingosine by sphingosine kinases (Sphks) (Figure 1). Two different isoforms of Sphk exist: Sphk1 and Sphk2 (Liu et al., 2002). They share overall homology but display different catalytic properties, subcellular locations, tissue distribution and temporal expression patterns (Limaye, 2008; Pitson, 2011). The catabolism of S1P is characterized by reversible degradation via S1P-selective phosphatase (SPP) or irreversible degradation by S1P lyase. SPP dephosphorylates S1P to sphingosine. SPP activity on the extracellular side of the plasma membrane is expected to reduce S1P receptor signalling activity by depletion of S1P, whereas intracellular SPP influences the second messenger function of S1P (Brindley, 2004). The irreversible degradation process by S1P lyase produces hexadecanal and phosphoethanolamine (Figure 1). S1P lyase is predominantly localized in the endoplasmatic reticulum facing the cytosol and appears to have a purely intracellular function (Ikeda et al., 2004).

Figure 1.

Ceramide is formed either de novo from serine, palmitoyl coA and fatty acid, or from breakdown of membrane-resident sphingomyelin. Ceramide is further converted to sphingosine, which could be phosphorylated to S1P. Degradation of S1P could be reversible by dephosphorylation or irreversible by S1P lyase. S1P, sphingosine-1-phosphate.

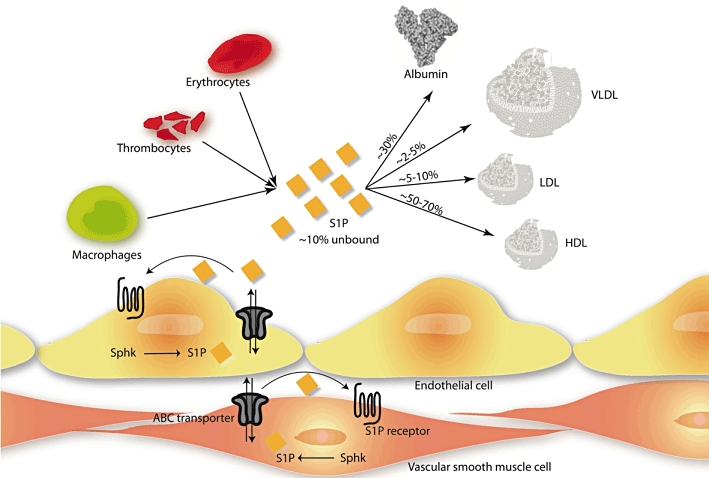

The major sources of S1P in the vascular system are haematopoietic cells such as erythrocytes, platelets, mast cells and leukocytes (Pappu et al., 2007; Hla et al., 2008). Erythrocytes, which lack both SPP and S1P lyase, appear to be able to buffer the S1P concentration in blood by controlled storing/release processes (Hanel et al., 2007; Bode et al., 2010). Vascular endothelial cells (ECs) also secrete S1P (Venkataraman et al., 2008). With a plasma concentration of S1P in the nanomolar range (Zhang et al., 2005), the concentration is much higher than the half-maximum concentration needed to stimulate its receptors. Potentially, vascular cells are exposed to saturated concentrations of S1P. However, the intensive interaction of S1P with lipoproteins decreases the apparent active concentration. S1P resides on serum albumin (SA) to about 30% and on lipoproteins, mainly involving high-density lipoprotein (HDL) (50–70%), followed by low-density lipoprotein (LDL) (5–10%) and then finally very low-density lipoprotein (2–5%) (Figure 2) (Murata et al., 2000; Okajima, 2002; Nofer et al., 2004). Recently, it could be shown that HDL is able to extract more S1P from erythrocytes than SA (Bode et al., 2010), pointing out a currently unidentified binding protein present in HDL.

Figure 2.

S1P is secreted by different blood cells, e.g. erythrocytes, thrombocytes and macrophages, or by endothelial cells (ECs). Once secreted, most of the S1P is uptaken by serum albumin or various serum lipoproteins. Intracellular-produced S1P in ECs or vascular smooth muscle cells could be transported across the membrane by ABC transporters. HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; Sphk, sphingosine kinase; S1P, sphingosine-1-phosphate; VLDL, very low-density lipoprotein.

S1P as an intracellular signalling molecule and ligand for extracellular receptors

S1P has diverse biological functions. Several lines of evidence suggest that S1P can function not only as a ligand for extracellular GPCR but also as an intracellular second messenger, which regulates calcium mobilization, cell proliferation and survival (Auge et al., 2000). This hypothesis is confirmed by findings that yeast responds to S1P but does not express S1P receptors (Gottlieb et al., 1999). Furthermore, it could be shown, that microinjection of S1P increases the intracellular S1P level resulting in calcium mobilization, whereas extracellular S1P has no effect on calcium release (Van Brocklyn et al., 1998). Other researchers confirmed these findings by showing that sphinganine (dihydro-S1P) cannot reproduce all the effects of S1P, although apparently activate all S1P receptors (Morita et al., 2000). It seems obvious that intracellular S1P has second messenger functions. Furthermore, S1P can be transported across lipid bilayers by ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters (Hla et al., 2008). Intracellularly produced S1P can activate its receptors on the cell surface but furthermore, extracellular S1P level could be decreased by intracellular transport (Spiegel and Milstien, 2003b) (Figure 2).

S1P receptors in vascular cells under physiological and pathophysiological conditions

Five GPCRs, which specifically bind S1P with a Kd of 8–26 nM (Lee et al., 1998; Van Brocklyn et al., 1999), are known and have been cloned so far: S1P1–5 (Chun et al., 2002). S1P receptors use G-protein signalling pathways, whereas different subtypes preferentially activate different G-proteins (summarized in Table 1). The receptors are involved in many physiological or pathophysiological processes, including cancer, nervous system function, autoimmune disease or multiple sclerosis (Birgbauer and Chun, 2006; Gardell et al., 2006; Brinkmann, 2007). The S1P receptors have been found to be expressed prevalently in many tissues and cell types (Table 1) (Kluk and Hla, 2002), in particular in the cardiovascular system (Mazurais et al., 2002; Alewijnse et al., 2004; Michel et al., 2007). The characterization of knockout mice (−/−) provided a very intensive insight in the special role for S1P receptors (Table 1): S1P1−/− are lethal in utero and show defects in the vascular maturation (Liu et al., 2000). Moreover, endothelial-specific S1P1−/− is lethal in utero, too (Allende et al., 2003). S1P2−/− were reported to develop an epileptic seizure (MacLennan et al., 2001) and also cause deafness (Herr et al., 2007; Kono et al., 2007). S1P3−/− appears to be without any obvious vascular phenotype (Ishii et al., 2001). S1P1–3 has a redundant or cooperative function for regular and mature vascular development during embryogenesis (Kono et al., 2004). Triple S1P1–3−/− shows vascular defects earlier than those in S1P1−/− alone (Kono et al., 2004).

Table 1.

S1P receptor expression and signalling pathways

| Receptor | Tissue expression | Knock out mice | G-protein coupling | Signalling pathway | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1P1 | Brain, lung, spleen, heart, vasculature, kidney | Lethal (key role in angiogenesis, neurogenesis, immune cell trafficking, endothelial barrier, vascular tone) | Gi/0 | (−): AC, (+): ERK, PI3K/Akt, eNOS, Rac | (Takuwa et al., 2008) |

| S1P2 | Widespread | Born with no apparent anatomical or physiological defects, but develop spontaneous, sporadic and occasionally lethal between 3 and 7 weeks of age | Gi/0, Gs, Gq, G12/13 | (−): AC (+): AC, PLC, JNK, p38, Rho, Rac | (Takuwa et al., 2008) |

| S1P3 | Heart, lung, spleen, kidney, intestine, diaphragm, cartilage | No obvious phenotype | Gi/0, Gq, G12/13 | (−): AC (+): ERK, PLC, Akt, eNOS, Rac, Rho | (Ishii et al., 2001; Takuwa et al., 2008) |

| S1P4 | Immune compartments/leukocytes, airway smooth muscle | ND | Gi/0, Gs, G12/13 | (+): AC, ERK, PLC, Rho | |

| S1P5 | White matter tracts of CNS, oligodendrocytes, myelinating cells | No deficits in myelination | Gi/0, G12/13 | (−): AC, ERK (+): JNK, p54JNK | (Jaillard et al., 2005) |

S1P2/3 double knockout mice encounter an embryonic lethality, although double-null survivors lack any phenotype. For more details and references see text.

ND, no data; (+), activation; (−) inhibition.

A great deal of knowledge about the S1P receptor function has been derived from studies focusing the immune system (Goetzl et al., 2004; Lin and Boyce, 2006; Wymann and Schneiter, 2008). Here, in the present review, only the importance for the vascular system is to be addressed. S1P receptors are essential for vascular development (Allende and Proia, 2002; Saba and Hla, 2004), and they regulate functions of the major cell types in the arterial vessels. Especially ECs and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) are activated by S1P. In particular, the ECs interact with blood cells, including leukocytes and macrophages. In the vascular system, S1P1–3 is expressed in ECs and VSMCs, whereas different results exist for the expression of S1P4–5 (Michel et al., 2007). Some researchers found S1P4–5 expression in arterial and venous VSMCs, whereas others found only S1P1–3. From a histological analysis in S1P1−/−, it has been shown very well that S1P1 is not essential for vascular ECs differentiation, proliferation, migration or tube formation during vascular genesis. Furthermore, S1P1 has no obvious effects on sprouting and branching of vessels during angiogenesis. However, there was a relevant defect in the association of VSMCs resulting in a weakened vasculature with disrupted and leaky vessels (Allende and Proia, 2002). These observations indicate a crucial role of S1P1 in vascular development (Allende and Proia, 2002; Sanchez and Hla, 2004). Kluk and Hla suggest that a higher proliferative capacity of rat intimal VSMC expresses greater levels of S1P1 than seen in adult medial cells (Kluk and Hla, 2001). There are some reports that expression of S1P1 receptors is variable and regulated in different vascular cell types. Vascular endothelian growth factor (VEGF) induces S1P1 expression in ECs (Igarashi et al., 2003). Furthermore, S1P1 is up-regulated in ECs exposed to S1P and thrombin, indicating a role in wound healing (Takeya et al., 2003). An up-regulation of S1P1 in ECs after hypoxia suggests a possible role in cerebrovascular pathophysiology (Hayashi et al., 2003; Waeber et al., 2004). Others found a correlation of S1P1 expression in different mouse strains with intimal hyperplasia. Inoue and co-workers could show that mice with a higher expression of S1P1 develop intimal hyperplasia following arterial injury (Inoue et al., 2007). In neointima, an early increase in S1P1/3 levels is observed. Pharmacological antagonization of both receptor subtypes then reduces neointima formation (Wamhoff et al., 2008).

S1P2 has an essential role in angiogenesis. S1P2−/− in mouse embryogenic fibroblasts (MEFs) leads to a more rapid proliferation in comparison with that of wild-type MEFs (Goparaju et al., 2005). Lorenz and co-workers identified a vascular dysfunction in S1P2−/− with an apparent decrease in overall vascular tone and contractile responsiveness, an elevation of regional blood flow and a decrease in vascular resistance (Lorenz et al., 2007). Skoura et al. demonstrate an induction of S1P2 in ECs during hypoxia. A development of retinal neovascularization is inhibited in S1P2−/− (Skoura et al., 2007). After arterial injury, antagonism of S1P2 results in a more robust neointima formation. The same effect is observed for S1P2−/− mice. Thus, there is definitive evidence that S1P2 activation protects against intimal hyperplasia (Shimizu et al., 2007). This is further confirmed by Wamhoff et al. who show that S1P2 antagonizes VSMC proliferation and phenotypic modulation in response to S1P in vitro or in vivo after arterial injury (Wamhoff et al., 2008). Recently, it could be shown that S1P2 signalling inhibits macrophage recruitment and therefore play an important role during inflammation. Michaud et al. investigated the effects of S1P2 during peritonitis and could show that S1P2−/− mice have enhanced macrophage recruitment (Michaud et al., 2010). Two other groups investigated the effects of S1P2 in atherosclerotic processes (Skoura et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2010). Both groups showed that S1P2 signalling is involved in atherosclerotic inflammation processes and they found a greatly attenuated atherosclerosis in ApoE−/−/S1P2−/− mice compared with ApoE−/− mice (Skoura et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2010). S1P2 seems to retain plaque macrophages (Skoura et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2010) and these macrophages from ApoE−/−/S1P2−/− mice displayed a reduced cytokine expression (Wang et al., 2010). Furthermore, ECs from double knockout mice have a diminished MCP-1 expression and an elevated endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) phosphorylation (Wang et al., 2010). Pharmacological antagonism of S1P2 in wild-type mice reduced the cytokine level in plasma (Skoura et al., 2011) and diminished the plaque size in ApoE−/−/S1P2+/+ mice (Wang et al., 2010). These data strongly indicates the role of S1P2 in atherogenesis and therefore S1P2 might be a novel therapeutic target for atherosclerosis. The physiological and pathophysiological potentials of S1P2 have been extensively reviewed by Skoura (Skoura and Hla, 2009). Furthermore, it could be shown that S1P receptors have an impact on adult angiogenesis (for a review, see Hla, 2004). These observations concern the physiological and pathophysiological importance of S1P receptors in the vascular system (reviewed by Takuwa et al., 2008; Means and Brown, 2009).

Intracellular signalling pathways and cross-talk with other receptor systems

The intracellular signalling pathways, which are regulated by S1P receptors, include the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway as are MEK, ERK1/2, p38, c-jun N-terminal kinase, phospholipase C and D, adenylyl cyclase, inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate, phosphoinositide 3 (PI3) kinase as well as focal adhesion kinase (Pyne and Pyne, 2000; Young and Van Brocklyn, 2006).

At least for S1P1 it is reported that homo- and heterodimers can exist with S1P2/3. S1P has no effect on receptor dimer formation (Van Brocklyn et al., 2002). The signalling cascade of S1P receptors is further linked to various pathways of cytokines and growth factors. This multivalency allows influencing, modulating and regulating inflammatory and proliferative signals within the cell. Tanimoto and co-workers identified a trans-activation of VEGF receptor by S1P (Tanimoto et al., 2002). They could show that inhibition of tyrosine kinase activity of VEGF receptor reduces the S1P-stimulated eNOS phosphorylation in the cells. Others also show a VEGF/S1P receptor cross-talk in a different manner. They describe that VEGF sensitizes the vascular endothelium to effects of lipid mediators like S1P by promoting the S1P1 induction in ECs (Igarashi et al., 2003). A recent study proposed a signalling complex of S1P and VEGF receptors (Bergelin et al., 2010). Other groups (Alderton et al., 2001; Hobson et al., 2001; Rosenfeldt et al., 2001; Hanafusa et al., 2002; Waters et al., 2003; Baudhuin et al., 2004; Tanimoto et al., 2004; Usui et al., 2004) found an interaction of S1P signalling with PDGF or the PDGF receptor in different models. The mode of interaction is specified in various ways. Pyne's group proposed a signalling complex of the S1P1 with the PDGF receptor (Alderton et al., 2001; Waters et al., 2003), whereas others describe a PDGF receptor trans-activation by intracellular phosphorylation after activation of S1P1(2,3) (Tanimoto et al., 2004) or rather S1P3 (Baudhuin et al., 2004). Spiegel's group describes a sequential interaction model, where platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor activation by PDGF results in Sphk activation leading to high intracellular S1P levels, which activates S1P1 after trans-membrane transport (Hobson et al., 2001; Rosenfeldt et al., 2001). Hanafusa et al. also found a proliferative capacity of S1P, but not as second messenger for PDGF (Hanafusa et al., 2002). Usui and co-workers describe an activation of PDGFA/B gene transcription after S1P1/3 activation (Usui et al., 2004). Furthermore, a cross-talk of S1P with the endothelial growth factor receptor (Tanimoto et al., 2004; Balthasar et al., 2008) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) receptor (Sauer et al., 2004; Xin et al., 2004a; Watterson et al., 2007; Igarashi et al., 2009) was described. Xin and co-workers were able to elegantly demonstrate that a possible heterologous S1P receptor desensitization by activation of purinoceptors in renal mesangial cells is possible (Xin et al., 2004b).

Biological functions of S1P on ECs and VSMCs in the vascular system

There are numerous reports that S1P regulates diverse biological functions in the vascular system. S1P is not only involved in physiological processes, but also in pathophysiological mechanisms. S1P functions as a receptor-active mediator as well as an intracellular signalling molecule with stimulatory or inhibitory roles in the migration and proliferation of ECs and VSMCs, regulation of vascular tone, endothelial barrier integrity, apoptosis, and inflammatory processes. S1P affects adhesion of leukocytes on activated ECs, followed by transmigration and cytokine production. All of these processes are reviewed in depth in the following paragraphs.

Regulation of the vascular tone

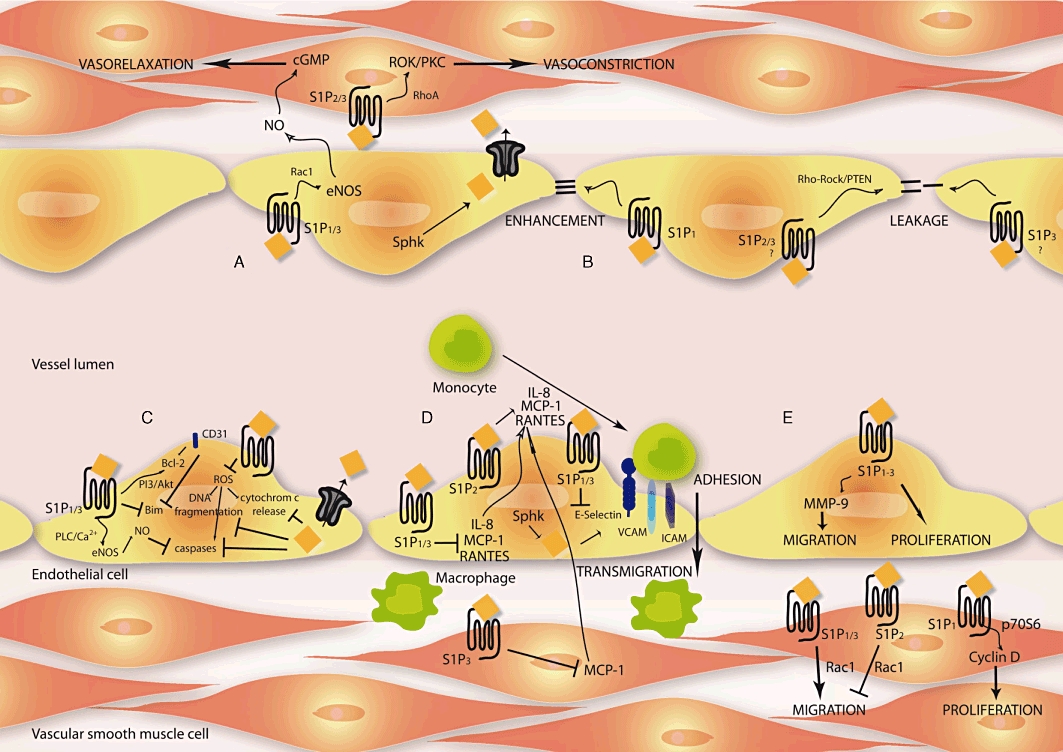

S1P regulates vascular tone and organ perfusion in different organs, e.g. heart, brain and kidney. The effects described seem partly contradictory, because not only vasoconstriction but also vasorelaxation is described in response to S1P. Moreover, the effects differ in magnitude and amplitude and were dependent on the different vascular regions (Michel et al., 2007). In rats, S1P constricts small arteries such as mesenteric, cerebral and renal arteries, but has no real effect on the aorta or carotid/femoral arteries (Bischoff et al., 2000; Salomone et al., 2003; 2008; Hedemann et al., 2004; Hemmings et al., 2004; Murakami et al., 2010). In vivo studies show similar effects. Infusion of S1P reduced rat mesenteric and renal blood flow (Bischoff et al., 2000). In the S1P-mediated vasoconstriction, S1P3 is involved (Salomone et al., 2003; 2008;). Salomone and co-workers found no contribution of S1P2 in the regulation of cerebrovascular constriction and pointed out unselective inhibitory effects of the proposed S1P2 antagonist JTE013 (Salomone et al., 2008). Recently, others found a S1P2-mediated vasoconstriction via Ras homolog gene family member A (RhoA) activation in murine pulmonary circulation using JTE013 and S1P2−/− mice (Szczepaniak et al., 2010). Vasorelaxing properties in response to S1P were also described. Phenylephrine-preconstricted aortic rings from rats and mice show vasorelaxation after S1P treatment (Nofer et al., 2004; Tolle et al., 2005; Roviezzo et al., 2006). This effect is thought to be regulated by S1P3 (Nofer et al., 2004; Tolle et al., 2005; Murakami et al., 2010). Recently, it could be shown that in rat coronary artery, anandamide induces relaxation via a mechanism requiring Sphk1 and S1P/S1P3 (Mair et al., 2010). Others investigated the effect of Sphk and S1P lyase in the regulation of vascular tone (Bolz et al., 2003; Peter et al., 2008; Mulders et al., 2009). The signal transduction underlying the effects of vascular tone regulation is reviewed elsewhere (Hemmings, 2006; Igarashi and Michel, 2009). In summary, while S1P-induced vasoconstriction has mainly been found in small vessels, S1P-induced dilatation has been found in both small and large vessels. The vessel size and the pattern of S1P receptors in different vascular beds may relate to the vasoactive effects of S1P (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Diverse biological functions are regulated by S1P: (A) vascular relaxation and constriction, (B) endothelial integrity, (C) apoptosis, (D) monocyte adhesion/transmigration and inflammatory response, and (E) migration and proliferation. Arrows indicate activation and capped line inhibition. For more detailed information and references, see text. eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; ICAM, inducible cell adhesion molecule; IL-8, interleukin 8; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; MMP-9, matrix metalloproteinase-9; PI3, phosphoinositide 3; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homology; RANTES, regulated upon activation, normal t-cell expressed, and secreted; ROCK, Ras homolog gene family member-associated protein kinase; ROS, reactive oxygen species; Sphk, sphingosine kinase; VCAM, vascular cell adhesion molecule.

Endothelial integrity

The intimal-located ECs in the vasculature are important to maintain barrier integrity and therefore regulate diapedesis of blood cells and other molecules. The permeability of this barrier is balanced by extracellular cell–cell and cell–matrix forces as well as intracellular cytoskeleton configuration by actin–myosin interactions. S1P induces a formation of actin lamellipodia and membrane ruffles as well as an increase in actin assembly leading to an enhanced barrier function (Garcia et al., 2001). Recently, Brown and co-workers provide deep insights in the molecular basis of responses of the cytoskeleton (Brown et al., 2010). Different studies were able to show that S1P maintains EC barrier integrity primarily by S1P1 activation (Garcia et al., 2001; Feistritzer and Riewald, 2005; Singleton et al., 2005), which strengthens EC junction. The transmonolayer electrical resistance is increased by S1P in the pulmonary microvascular endothelium (Schaphorst et al., 2003). Furthermore, S1P1−/− studies encourage the necessary role of S1P1 for maintaining EC barrier, because S1P1−/− (Liu et al., 2000) and endothelial-specific S1P1−/− were lethal in utero (Allende and Proia, 2002). In vivo studies confirm the important role of S1P1 because it could be shown that S1P1 antagonism enhances pulmonary capillary leakage (Sanna et al., 2006). Different signalling pathways are involved in the regulation of cell junction assembly such as the zonula occludens protein-1 (Lee et al., 2006), Ca2+ (Mehta et al., 2005), PI3 kinase, Tiam1/Rac1 (Garcia et al., 2001; Schaphorst et al., 2003), VE-cadherin (Sanchez et al., 2007) and β-catenin (Sun et al., 2009; Lucke and Levkau, 2010). In contrast to the protective effects of S1P1, different studies ruled out S1P2 as being responsible for any weakening of the endothelial barrier. S1P2 activation resulted in disruption of adherens junctions by inhibition of VE-cadherin, stimulation of stress fibres and increased paracellular permeability via the Rho-Ras homolog gene family member-associated protein kinase and phosphatase and tensin homology pathway (Sanchez et al., 2007). The role of S1P3 in endothelial barrier function is controversial. Some authors rule out a protective function of S1P3 activation (Garcia et al., 2001; Lucke and Levkau, 2010), while others found S1P3 to be a negative regulator of barrier integrity (Gon et al., 2005; Singleton et al., 2006). A recent study by Zhang et al. using agonists and antagonists of S1P receptor signalling observed that only S1P1 activation in ECs is responsible for the protective action of S1P on microvessel permeability, although S1P1–3 is present in intact venules (Zhang et al., 2010). Various reports summarize the understanding of the receptor-basis of endothelial permeability changes in more detail (Liu et al., 2001; McVerry and Garcia, 2004; 2005; Peng et al., 2004; Singleton et al., 2006; Rosen et al., 2007; Wang and Dudek, 2009) (Figure 3B).

Apoptosis

Pathological mechanisms in the vasculature are often associated with endothelial dysfunction that leads to an increased cell turnover rate and hence ECs undergo apoptosis. S1P is a potent factor preventing apoptosis in ECs by inhibition of caspases, cytochrome c release and DNA fragmentation (Cuvillier et al., 1996; 1998;). Furthermore, HDL-associated S1P mediates survival benefits in mice cardiomyocytes and isolated hearts administrated to ROS (Tao et al., 2010). The protective function of S1P is not only based on its receptor activation and downstream G-protein mediated signalling pathways (Radeff-Huang et al., 2004), but also by S1P as an intracellular signalling molecule.

One known important inhibitory factor of endothelial apoptosis is nitric oxide (NO). Via activation of the PI3/Akt pathway, eNOS phosphorylation leads to enhanced NO production (Rossig et al., 2001). NO mediates its protective function by nitrosylation of a cysteine residue in the catalytic centre of caspases and therefore leads to an enzyme inactivation. Kwon and co-workers could show that the protective effects of S1P were dependent on S1P1/3 activation whereas inhibition of NO synthase reversed the effect (Kwon et al., 2001). Others demonstrated cytoprotective effects of S1P via S1P1–3 (Donati et al., 2007; Hofmann et al., 2009; Nieuwenhuis et al., 2009). A cytokine that promotes apoptosis in many cell types is the tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) via TNF-receptor 1 activation. Xia et al. demonstrated that human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) are resistant to TNFα-induced apoptosis by activation of intracellular Sphk (Xia et al., 1999b). Furthermore, the authors could show that in a spontaneously transformed ECs line where TNFα failed to induce Sphk, exogenous S1P protects the cells from TNFα-induced apoptosis (Xia et al., 1999b). Others confirmed these findings by demonstrating that an overexpression of Sphk suppresses apoptosis in a pertussis toxin (PTX)-independent manner (Olivera et al., 1999). SPP−/− in mice resulted in a resistance to growth inhibition induced by TNFα (Johnson et al., 2003). Next, it could be shown that the junctional molecule CD31 (PECAM-1) is involved in EC survival. Overexpression of Sphk leads to an up-regulation and dephosphorylation of CD31 (Limaye et al., 2005). CD31-mediated anti-apoptotic effects are PI3/Akt-dependent and associated with the up-regulation of the B-cell lymphoma gene 2 (Bcl-2) and down-regulation of bisindolylmaleimide (Bcl-2 interacting mediator of cell death) (Limaye et al., 2005). Another apoptosis-inducible factor in vascular disease is the increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the vasculature. It could be shown that S1P protects ECs apoptosis via inhibition of ROS. H2O2-induced phosphorylation of p38 could be reversed by S1P pretreatment (Moriue et al., 2008). The effects of S1P regarding EC apoptosis mechanisms are summarized in Figure 3C.

Influence of S1P on leukocyte adhesion

The activation of the endothelium and monocyte recruitment from the blood flow is necessary for an inflammatory response in the sub-endothelial space. Cytokines such as RANTES and MCP-1 are released by activated platelets, monocytes, macrophages, VSMCs or ECs, resulting in enhanced leukocyte recruitment to the endothelium (Sheikine and Hansson, 2004). For the monocyte/EC interaction adhesion molecules, e.g. E-selectin, inducible cell adhesion molecule and vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM) on the surface of EC must increase (Berliner et al., 1995). Different studies could show inhibitory effects of S1P on leukocyte adhesion, an initial step for diapedesis and progression of inflammatory response. Nofer et al. demonstrated that HDL-associated lysophospholipids inhibit TNFα-induced expression of E-selectin in a partially S1P3-mediated manner (Nofer et al., 2003). Others demonstrated an activation of eNOS after TNFα treatment via S1P receptors, inhibition of E-selectin expression and adhesion of cells (De Palma et al., 2006). These results were confirmed by Kimura and co-workers who show an S1P3-mediated interaction with the scavenger receptor B type I (SR-BI) (Kimura et al., 2006a). Other studies identified S1P1 signalling involved in the inhibition of leukocyte adhesion. A stable long-term S1P1−/− decreased the expression of CD31, VE-cadherin and E-selectin in HUVECs after lipopolysaccharide and TNFα stimulation (Krump-Konvalinkova et al., 2005). Others demonstrated an S1P1-mediated inhibitory effect of S1P on monocyte/EC interaction in diabetic non-obese diabetic mice (Whetzel et al., 2006). Besides the inhibitory function of S1P on the expression of adhesion molecules, S1P also suppressed the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. It could be shown by our own group that S1P is able to inhibit MCP-1 production in VSMCs in a redox-sensitive manner via S1P3 (Tolle et al., 2008). Bolick and co-workers demonstrated that S1P prevents TNFα-mediated monocyte adhesion by inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokine production in a S1P1-mediated way (Bolick et al., 2005). Others show an inhibitory potential of S1P on TNFα-induced secretion of RANTES in human bronchial SMCs (Kawata et al., 2005). Furthermore, cross-activation of the potent anti-inflammatory cytokine TGF-β via the S1P3 attenuates the expression of pro-inflammatory genes like inducible NO synthase, secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2) and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) in mesangial cells (Xin et al., 2004a).

However, in addition to the inhibitory signals of S1P described to reduce leukocyte adhesion, there has also been evidence for promoting adhesion molecule expression in ECs (Kimura et al., 2006b) and stimulating the release of MCP-1 and interleukin-8 (IL-8) (Lin et al., 2006). Furthermore, intracellular-produced S1P by Sphk1 stimulates VCAM-1 and E-selectin via activation of the transcription factor NFκB (Xia et al., 1998; Rizza et al., 1999; Shimamura et al., 2004). A recent study by Weis et al. also demonstrates stimulatory potential of S1P on E-selectin expression and monocyte adhesion (Weis et al., 2010), which is in agreement with others (Lee et al., 2004; Lin et al., 2007). In addition, Sphk1 activation contributes to induction of cyclooxegenase-2 and production of prostaglandine E2 (PGE2), and PGE2 release could be further augmented by knockdown of S1P-degrading enzymes (Pettus et al., 2003). In line with this was the finding that a chronic and marked overexpression of Sphk1 promotes a pro-inflammatory phenotype in cultured ECs (Limaye et al., 2009). Inconsistently, others found a S1P-independent pathway of TNFα-induced production of adhesion molecules (Miura et al., 2004). Further studies are needed to clarify the inhibitory and/or stimulatory effects of S1P on adhesion, and elucidate the underlying mechanisms (Figure 3D).

Effects of S1P on inflammation and plaque instability

Adherence of leukocytes on activated ECs is followed by transmigration into the sub-endothelial space where they promote the inflammatory response (Weber et al., 2008). Pro- and anti-atherogenic potentials has been described for S1P. S1P increases the production of IL-8 and MCP-1 in HUVECs (Lin et al., 2006) and human alveolar ECs (Milara et al., 2009). S1P enhances the survival of human T-lymphoblastoma cell lines in a S1P1/3-dependent manner (Goetzl et al., 1999). S1P induces the production of MMPs (Langlois et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2005; Sun et al., 2010), which may result in a degradation of extracellular matrix, thinning of the cap and plaque rupture in atherosclerotic lesions.

However, in mouse models it could be shown that treatment with FTY720, an S1P analogue, significantly reduces atherosclerotic plaques (Keul et al., 2007; Nofer et al., 2007). In addition, S1P regulates the expression of adhesion molecules and therefore influences the leukocyte and monocyte number in lesions, whereas both activation and inhibition have been described (Lee et al., 2004; Whetzel et al., 2006; Kimura et al., 2006b; Lin et al., 2007). Recently, authors demonstrated an involvement of S1P2 in macrophage migration, a finding which shows that S1P2 inhibits macrophage migration in vitro (Michaud et al., 2010). Furthermore, S1P2−/−/ApoE−/− leads to inhibition of pro-inflammatory signalling in atherosclerotic plaque macrophages (Skoura et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2010). Atheroprotective effects of S1P may also be triggered by selective attenuation of toll-like receptor 2 (Duenas et al., 2008). Furthermore, the S1P receptors rebalance alterations in the coagulation pathway (Ruf et al., 2009) and therefore decrease the risk of thrombosis. Moreover, HDL may act as a sensor to balance inflammatory signals in the vascular wall (Norata and Catapano, 2005; Norata et al., 2008). Actually, different groups investigated the potential of S1P1, necessary for lymphocyte egress. A transgenic overexpression of S1P1 in immature thymocytes leads to perivascular accumulation (Zachariah and Cyster, 2010) and knockin mice with mutated internalization motif of S1P1 suffer from delayed lymphopaenia after S1P1 activation (Thangada et al., 2010). Furthermore, Sphk activity is required for lymphatic egress (Pham et al., 2010). The pro- and anti-inflammatory potential of S1P is summarized in Figure 3D.

Migration and proliferation of ECs and VSMCs in the vasculature

S1P regulates proliferation and motility as well as directional migration of a variety of cells, including ECs and VSMCs (Kimura et al., 2000; Kluk and Hla, 2001). Cell migration and proliferation are not only essential processes involved in embryogenesis but also in inflammation, wound healing, tumour growth and angiogenesis. Studies using transfected rat hepatoma cell line HTC4 cells could show that S1P2/3 activation mediates cell proliferation (An et al., 2000). Others identified S1P1/3 as being essential in EC proliferation (Kimura et al., 2000). S1P1 overexpression in VSMCs leads to activation of p70S6 kinase and cyclin D expression and thus results in VSMC proliferation (Kluk and Hla, 2001; 2002). Recently, S1P was measured in the plasma of patients with Fabry disease (Brakch et al., 2010). The S1P level is a positive correlating factor for left-ventricular hypertrophy and arterial intima-media thickening in these patients (Brakch et al., 2010). Besides positive proliferation signal, anti-proliferative responses can be mediated, too. S1P2−/− MEFs proliferate more rapidly than wild-type MEFs (Goparaju et al., 2005). Currently, it is indeed difficult to describe the relevant receptors for cell proliferation. There are reports that one S1P receptor subtype can stimulate proliferation in some cells, while inhibiting it in others (An et al., 2000; Goparaju et al., 2005). This dilemma has however not yet been solved. The currently available information is somewhat confusing. A very similar problem is observed when investigating the relevance of S1P receptor signalling in cell migration. Several groups have reported both stimulatory and inhibitory potentials of S1P on migration. Kimura and co-workers could show a S1P1/3-dependent migration of human ECs (Kimura et al., 2000), which was confirmed by two other groups (Panetti et al., 2000; Boguslawski et al., 2002). S1P influences the migratory events necessary for the formation of blood vessels (Argraves et al., 2004). Furthermore, it could be shown, that S1P is able to activate membrane-type 1 MMP in ECs representing a link between homoeostasis and cell migration (Langlois et al., 2004). Recently, Anelli et al. identified Sphk1 as an important determinant of S1P-induced migration and tube formation in ECs in vitro (Anelli et al., 2010). Contrary effects were obtained by others, who found an inhibitory potential of S1P on the migration of ECs and VSMCs. S1P inhibits the PDGF-induced chemotaxis of human VSMCs (Bornfeldt et al., 1995). Furthermore, it could be shown that the inhibitory effects of S1P on migration are important for early heart development (Wendler and Rivkees, 2006). Tamama et al. demonstrated inhibition of VSMC migration by HDL-associated S1P (Tamama et al., 2005). The inhibitory actions were diminished by S1P2-specific siRNA (Damirin et al., 2007) and an S1P2 antagonist could enhance VSMC and EC migration (Osada et al., 2002). This is supported by findings of Takashima and co-workers who showed that S1P2 mediates inhibition of Rac, therefore leading to a suppression of VSMC migration (Takashima et al., 2008). In vivo studies confirmed these findings. In S1P2−/−, large neointimal lesions developed after ligation of the carotid artery (Shimizu et al., 2007). Furthermore, VSMCs have an enhanced migration rate in response to S1P, compared with VSMCs in wild-type mice (Shimizu et al., 2007). The authors concluded that S1P2 normally suppresses VSMC migration in arteries, and that S1P regulates neointimal development. Others also found an increased migration rate after inhibiting S1P2 (Inoue et al., 2007). Ryu et al. elucidate a negative or positive regulation of Rac activity, which is critically involved in S1P-mediated migration of VSMCs and ECs (Ryu et al., 2002). Recently, authors demonstrated that soluble forms of VEGF receptors were physiologically released, and that this contributes to blood vessel stabilization. The authors showed that the VEGF receptors promote mural cell migration in a paracrine pathway, where the S1P1-mediated activation of eNOS is involved (Lorquet et al., 2010). The S1P-mediated effects on migration and proliferation on ECs and VSMCs are summarized in Figure 3E.

Conflictive effects of S1P and HDL-associated S1P

One pathological feature of vascular disease is atherosclerosis which reflects a complex interaction of inflammatory signals within the vessel wall (Weber et al., 2008). In the last several years, it has become evident that inhibition of inflammation might be one important therapeutic option in atherosclerosis treatment. S1P was identified as a potent anti-inflammatory and anti-atherogenic molecule. These findings are mostly based on HDL-associated S1P. Authors who reported that intracellular S1P stimulates the expression of adhesion molecules in ECs (Xia et al., 1998) reported later an inhibition of adhesion molecules by HDL via inhibiting Sphk activity (Xia et al., 1999a). Kimura et al. demonstrate HDL-induced cytoprotective action of S1P in human ECs (Kimura et al., 2001). Later, it could be shown by the same authors that S1P stimulates VCAM, whereas HDL inhibits it – demonstrating both stimulatory and inhibitory signals for expression of adhesion molecules mediated by S1P receptors (Kimura et al., 2006b). HDL-mediated inhibition of adhesion molecules was dependent on a co-receptor, namely SR-BI (Kimura et al., 2006a). Consistently, others found an HDL-mediated anti-apoptotic action on ECs (Nofer et al., 2001). Additionally, S1P inhibited VSMC migration (Bornfeldt et al., 1995; Tamama et al., 2001) and stimulated endothelial function (Lee et al., 1999; Igarashi and Michel, 2001; Kwon et al., 2001). Our own group could show that sphingolipids were anti-inflammatory by reducing MCP-1 production in VSMCs (Tolle et al., 2008).

However, the role of S1P is complex and has pro-atherogenic potential, too. S1P seems to be an atherogenic factor by enhancing VSMC proliferation and migration (Sachinidis et al., 1999; Boguslawski et al., 2002; Xu et al., 2002). Furthermore, TNFα activates Sphk and the increasing S1P level leads to the stimulation of adhesion molecule expression in ECs (Xia et al., 1998). An activation of Sphk by oxidized LDL resulted in VSMC proliferation (Auge et al., 1999; Kimura et al., 2001). In addition, S1P has pro-atherogenic potential by stimulation of platelet aggregation (Yatomi et al., 1997) and anti-apoptotic actions on T-cells and leukocytes (Cuvillier et al., 1996).

In summary, these observations suggest not only different roles of intracellular versus extracellular S1P effects, but also a free S1P versus lipoprotein-associated S1P effect. Recently, it could be shown that the HDL-unbound S1P content correlates with the severity of coronary artery disease (CAD) (Sattler et al., 2010). The authors provide evidence that the HDL-unbound S1P contents in the plasma of patients with acute myocardial infarction (MI) and stable CAD (sCAD) are higher than in healthy controls. Furthermore, they showed a negative association of unbound S1P content and HDL-bound S1P in healthy controls, which is lost in patients with MI and sCAD (Sattler et al., 2010).

A report by Okajima provides evidence that intracellular S1P acts as an atherogenic mediator, whereas extracellular S1P delivered anti-atherogenic potential by activating S1P receptors (Okajima, 2002). To determine pro- or anti-atherosclerotic effects in different vascular regions, it has to be precisely defined which receptor subtypes are involved as well as which of the various expression patterns are present. Some findings support the role of S1P as an intracellular messenger to promote cell survival and proliferation. The cytoprotective effect of S1P seems to be S1P receptor independent, because the effects were neither blocked by PTX nor reproducible by sphinganine (Cuvillier et al., 1996; Olivera et al., 1999). But in addition, other reports demonstrate pro-survival effects of S1P mediated by its receptors. It could be shown that cytokine-induced apoptosis in rat islet cells could be blocked by an S1P receptor antagonist (Laychock et al., 2006). Other studies using the siRNA approach diminished the cell survival effects of S1P in ECs (Kwon et al., 2001). The complexity of the system increases even further by findings of S1P ‘inside-out-signaling’ (Takabe et al., 2008). This topic of the oppositional effect of S1P and lipoprotein-associated S1P is also addressed in many recently published reviews (Hla, 2004; Alewijnse and Peters, 2008; Sattler and Levkau, 2009; Tolle et al., 2010). The effects of S1P on atherogenesis may differ depending on its source – extracellular versus intracellular – (Spiegel and Milstien, 2003a), concentration, binding proteins – HDL-associated S1P – (Argraves and Argraves, 2007) and the expression pattern of the vascular cells (Daum et al., 2009).

S1P receptor agonists and antagonists

S1P and its receptors have diverse physiological and pathophysiological properties and are involved in many cellular processes as described previously. Therefore, targeting S1P receptors with pharmacological agonists and antagonists is not only of interest for in vitro studies to discriminate specific effects by different S1P receptors, but also in regard to ascertaining the potential of therapeutic treatment of diseases. In the last few years, many agonists/antagonists of the S1P receptors could be developed and for some of them, besides animal studies, clinical data are also available (Table 2). In the following paragraph, each known substance is analyzed in detail. Only substances with current clinical potential are reviewed here.

Table 2.

Agonists/antagonists of S1P receptors

| Agonist / antagonist | Receptor | Animal studies | Clinical studies | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTY720 | S1P1/3/4/5 | Yes | Yes | Mandala et al., 2002 |

| AAL-R | S1P1/3/4/5 | ND | ND | Brinkmann et al., 2002 |

| KRP-203 | S1P1 | Yes | ND | Fujishiro et al., 2006a; Song et al., 2008 |

| AUY954 | S1P1 | Yes | Yes | Pan et al., 2006 |

| RG3477 | S1P1 | Yes | Yes | Bolli et al., 2010 |

| SEW2871 | S1P1 | Yes | ND | Sanna et al., 2004 |

| CYM-5442 | S1P1 | Yes | ND | Gonzalez-Cabrera et al., 2008 |

| W146 | S1P1 | Yes | ND | Sanna et al., 2006 |

| Compound 5 | S1P1 | Yes | ND | Yonesu et al., 2009; 2010; |

| JTE013 | S1P2 | Yes | ND | Osada et al., 2002 |

| TY-52156 | S1P3 | Yes | ND | Murakami et al., 2010 |

| VPC23019 | S1P1/3 | ND | ND | Davis et al., 2005 |

| VPC44116 | S1P1/3 | Yes | ND | Foss et al., 2007 |

For more details concerning clinical studies and more references, see text.

ND, no data.

FTY720 (Novartis, Basel, Switzerland)

FTY720 was first synthesized in 1992 by structural modifications of a fungal metabolite from Isaria sinclairii. Later, it could be shown that FTY720 is a prodrug, phosphorylated in vivo by Sphk2, but not Sphk1 (Allende et al., 2004; Kharel et al., 2005). FTY720-phosphate (FTY720-P) is biologically active and a structural analogue of S1P. It binds to S1P1–5, except for S1P2 (Brinkmann et al., 2002; Mandala et al., 2002). Receptor binding of FTY720 seems not to mimic S1P as a natural ligand on all S1P receptor subtypes. Sensken and co-workers reported that FTY720-P selectively activates Gi and antagonizes Gq coupling at S1P3 and therefore selectively activates only one signalling pathway (Sensken et al., 2008). Although it is an agonist of S1P1, it behaves like a functional antagonist, causing ubiquitination and degradation of the receptor (Graler and Goetzl, 2004; Oo et al., 2007). Therefore, FTY720 is able to desensitize S1P-mediated processes, e.g. angiogenesis and tumour vascularization (LaMontagne et al., 2006). The two proposed models of the molecular mechanism of FTY720 are summarized by Kihara and Igarashi (Kihara and Igarashi, 2008). FTY720 has been developed for the prevention of kidney graft rejection and autoimmunity. FTY720 has potent immunosuppressive activity (Budde et al., 2003; Kahan et al., 2003) by inhibiting T-cell proliferation (Wolf et al., 2009). Precise mechanisms how FTY720 works as an immunosuppressant are reviewed elsewhere (Baumruker et al., 2007; Graler, 2010). Animal studies ruled out any beneficial effect of FTY720 by prolonging allograft survival in animal solid organ transplantation models (Hwang et al., 1999; Kimura et al., 2003). In 2006, phase II and III clinical trials for the prevention of kidney graft rejection have been completed. The trial failed to demonstrate superior effects of FTY720 over other known immunosuppressive drugs (Salvadori et al., 2006; Tedesco-Silva et al., 2006). Several side effects need to be investigated further (Salvadori et al., 2006; Tedesco-Silva et al., 2006). Studies in rats provide evidence that treatment with FTY720 reduced ischaemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) and prevented acute renal failure (Delbridge et al., 2007b). Furthermore, it could be shown that renal fibrosis – as a result of IRI – could be reduced by FTY720 treatment (Delbridge et al., 2007a). The renoprotective effects seem to be S1P1-mediated. FTY720 and SEW2871, as selective S1P1 agonists, reduced IRI in mice (Bajwa et al., 2010). Ongoing trials are being investigated whether or not FTY720 might also be beneficial towards other diseases like multiple sclerosis (Kappos et al., 2006; 2010; Baumruker et al., 2007; Foster et al., 2007; Miron et al., 2008; O'Connor et al., 2009; Comi et al., 2010), cancer (LaMontagne et al., 2006; Peyruchaud, 2009) or skin disease (Herzinger et al., 2007). Within 2011, there will be a Food and Drug Administration approval for FTY720 as a drug in the treatment of multiple sclerosis.

KRP-203 (Kyorin Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan)

KRP-203 is a novel immunosuppressant with structural similarities to FTY720, but selectively activates S1P1 (Shimizu et al., 2005). KRP-203 prolonged allograft survival but attenuated side effects seen by FTY720. In an orthotopic aortic transplantation model, changing from cyclosporine treatment to a mycophenolate mofetil/KRP-203 combination therapy reduced vasculopathy in the animals (Fujishiro et al., 2006b). In another study by the same group, KRP-203 in combination with sub-therapeutic doses of cyclosporine not only prolonged allograft survival but also rather improved graft kidney function in a rat model (Fujishiro et al., 2006a). Other researches confirmed these findings and could show that a KRP-203 markedly improved immune responses in a rat heart transplantation model (Suzuki et al., 2006). The authors speculated that a combination therapy of mycophenolic acid with KRP-203 might have a therapeutic potential in an immunosuppressant strategy. Further studies addressing the potential of KRP-203 are summarized by Takebe et al. (Takabe et al., 2008).

AUY954 (Novartis, Basel, Switzerland)

The amino carboxylate analogue of FTY720 – AUY954 – is a selective agonist of S1P1. In a rat heart transplantation model, AUY954 prevents allograft rejection (Pan et al., 2006). Due to its selectivity and pharmacokinetic profile, AUY954 might have a potential for therapeutic treatment.

RG3477 (Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd.)

RG3477 (ACT-128800, Compound 8bo) is a potent and selective agonist of S1P1 (Bolli et al., 2010). Pharmacokinetic studies ruled out that it is orally active and showed that it has a rapid decrease within 36 h in the plasma. Meanwhile, RG3477 has undergone toxicity testing and is evaluated in clinical trials for autoimmune disease and organ transplantation respectively (Bolli et al., 2010). First entry-into-humans studies show promising results for single doses per day (Brossard et al., 2009).

SEW2871 (Maybridge, Tintagel, Cornwall, UK)

SEW2871 is structurally unrelated to S1P but a selective agonist for S1P1 (Sanna et al., 2004). It induces internalization and recycling of S1P1 (Jo et al., 2005) without activating S1P3, and therefore SEW2871 does not cause bradycardia (Brinkmann et al., 2004). Another study could show that SEW2871 treatment protects kidneys against ischaemia/reperfusion injury in animals (Awad et al., 2006). Furthermore, it preserves renal function, reduces immune cell infiltration and decreases the severity of acute tubular necrosis (Lien et al., 2006).

CYM-5442

CYM-5442 is a potent agonist of S1P1 and binds separate from the binding side for S1P on the receptor (Gonzalez-Cabrera et al., 2008). Alongside the characterization of this substance in vitro where it shows a full agonism for S1P1 internalization, phosphorylation and ubiquitination, the in vivo treatment in mice induces lymphopaenia (Gonzalez-Cabrera et al., 2008).

W146

A potent and selective chiral antagonist of S1P1 is W146 (Sanna et al., 2006). The in vivo activity could be elucidated in a capillary leakage model with mice (Sanna et al., 2006). The administration of W146 induced loss of capillary integrity while not affecting blood lymphocyte numbers (Sanna et al., 2006).

Compound 5

Yonesu and co-workers synthesized chemical compounds, which function as S1P1 antagonists and show anti-angiogenesis activity (Yonesu et al., 2009). Synthesis of derivatives of these non-S1P-analogues yielded effective S1P1 antagonists, which were named compounds 1 to 5 (Yonesu et al., 2010). One derivate, compound 5, shows S1P1-mediated antagonistic effects on migration, proliferation and tube formation in HUVECs and moreover inhibits S1P-induced hypertension in rats (Yonesu et al., 2010).

JTE013 (Central Pharmaceutical Research Institute, Osaka, Japan)

A selective S1P2 antagonist is JTE013 (Kawasaki et al., 2001). To date, only a few animal studies on this have been carried out. One study investigates the effect of JTE013 in a wound-healing model. Co-administration of S1P with S1P2 antagonism with JTE013 enhances the wound-healing effect of S1P in diabetic mice (Kawanabe et al., 2007). A study in 2008 ruled out that JTE013 does not appear to be selective. The authors investigated cerebrovascular constriction in peripheral arteries of either rat or mouse (Salomone et al., 2008). The inhibitory effects of JTE013 were also present in S1P2−/−, pointing out an unrelated antagonism to the S1P2, too (Salomone et al., 2008). The concentration of the antagonist used was similar to that found in previous studies (Osada et al., 2002; Ohmori et al., 2003). These findings indicate the need for new, more selective S1P2 antagonists to verify the involvement of this receptor subtype in vascular responses.

TY-52156

Lately, a new selective S1P3 antagonist, TY-52156, was developed (Murakami et al., 2010). Besides the data in vitro, first in vivo experiments show evidence that oral treatment of TY-52156 might reduce S1P3-dependent bradycardia in rats (Murakami et al., 2010).

VPCs

Numerous S1P analogues were synthesized and tested as unselective competitive S1P1 and S1P3 antagonists (Davis et al., 2005). Furthermore, two structural-related S1P1/3 agonists exist: VPC23153 and VPC24191. These substances are only used for pharmacological purposes for in vitro assays. There is no information on the use in animal models so far.

Because of its great therapeutical potential, researchers are still investigating the production and characterization of novel highly selective S1P receptor agonists and antagonists that might help to distinguish subtype-specific S1P receptor signal transduction in vitro and in vivo. More pharmacological agonists and antagonists of the S1P receptor subtypes have been reviewed recently (Rosen et al., 2008; 2009; Marsolais and Rosen, 2009; Im, 2010).

Therapeutic effects and pharmacological relevance in pharmaceutical intervention of S1P signalling in the vascular system

FTY720

Because S1P could not be administrated orally, it is difficult to study the effects in long-term experiments; FTY720 overcomes that problem, because it is orally available. Thus, in 1999 Hwang and co-workers provided first evidence that FTY720 treatment might have positive implication on atherogenesis in a cardiac transplantation model (Hwang et al., 1999). Later, Nofer et al. used a model with LDL−/− mice to investigate the effect of FTY720 on the progression of atherosclerosis (Nofer et al., 2007). S1P receptor activation by FTY720 induces a functional change of lymphocytes and macrophages leading to inhibition of atherosclerosis progression (Nofer et al., 2007). This seems to be in agreement with data from Singer and co-workers who showed that FTY720 increases homing of macrophages to lymphatic tissue (Singer et al., 2005). In another study, FTY720 reduces atherosclerotic plaque size in an ApoE−/− mouse model fed with a high cholesterol diet (Keul et al., 2007). Both groups showed in accordance with each other that FTY720 treatment reduced atherosclerosis, whereas the definitive mechanism is still elusive. However, other researchers could not confirm these findings in a further published study. The authors did not find changes in atherosclerotic levels due to FTY720 feeding in a model with ApoE−/− mice (Klingenberg et al., 2007). Their model varies from that of Keul and co-workers (Keul et al., 2007) in the use of diets having reduced amounts of cholesterol, where only a moderate atherosclerosis is observed. Further effects of FTY720 on the vascular system were described. Our own group could show that FTY720 induces NO-dependent vasorelaxation of rat aortic rings in a S1P3-mediated manner (Tolle et al., 2005). Walter et al. also demonstrated a S1P3-dependent action of FTY720 (Walter et al., 2007). Patient-derived endothelial progenitor cells, which were stimulated with FTY720, improved blood flow recovery in a mouse model of hind limb ischaemia (Walter et al., 2007). Butler et al. demonstrated EC migration-stimulating effects of FTY720 (Butler et al., 2004). Others describe a beneficial effect on vascular permeability. FTY720 blocked the VEGF-induced increase in vascular permeability in mice (Sanchez et al., 2003). Recently, it could be shown that FTY720 was able to prevent ischaemia/reperfusion injury in a rat heart model and the cardioprotective effect involves the Pak1/Akt signalling (Egom et al., 2010). Anti-inflammatory potential has also been described for FTY720. In renal mesangial cells, the cytokine-induced expression of sPLA2 is suppressed (Xin et al., 2007). At the same time, others found an inhibitory effect of FTY720 on cytosolic PLA2 secretion in a phosphorylation- and S1P receptor-independent manner (Payne et al., 2007). Recently, FTY720-P is considered to be a cytoprotective substance in human fibroblast by inhibiting apoptosis via S1P3 (Potteck et al., 2010). This seems to be in contrast to many other studies, which demonstrated an apoptotic-induced effect of FTY720 (Matsuda et al., 1999; Yasui et al., 2005; Hung et al., 2008). But, for these cytotoxic effects, S1P receptor independent pathways have been proposed (Brinkmann et al., 2001).

Besides all of these described beneficial effects of FTY720 on the vascular system, harmful effects using therapeutic concentrations have also been described. FTY720 impairs important endothelial functions by inhibiting S1P-mediated endothelial healing (Krump-Konvalinkova et al., 2008).

A new utility to investigate S1P response in vitro and in vivo is offered through the identification of the first pan-antagonist of S1P receptors. Recently, Valentine et al. characterized two unsaturated phosphate enantiomers of FTY720: (R)- and (S)-FTY720-vinylphosphonate (Valentine et al., 2010). The authors could show that the (S) enantiomer failed to activate any of the five S1P receptors. It is a full antagonist of S1P1/3/4 and a partial antagonist of S1P2/5 (Tigyi et al., 2010; Valentine et al., 2010).

Selective S1P1 agonists

Selective S1P1 agonists might have a therapeutical potential for the treatment of a variety of diseases, in particular immune-mediated diseases. Only few in vivo studies exist, which address the therapeutical potential of selective S1P1 receptor agonists. Theoretically, the side effects of FTY720 like bradycardia should be eliminated, because they seem to be S1P3 mediated. Studies with AUY954 could show that the selective S1P1 agonist is able to prevent allograft rejection in a rat heart transplantation model (Pan et al., 2006), but no human clinical studies are available to date. One selective S1P1 agonist, RG3477, is currently being evaluated in clinical trials for organ transplantation and autoimmune disease (Bolli et al., 2010). The recent study of Bajwa and co-workers (Bajwa et al., 2010) provide a therapeutic potential of selective S1P1 agonists for the treatment of acute kidney injury.

Anti-S1P antibody

In 2006, a highly specific monoclonal antibody against S1P (Sphingomab, LT1002) has been developed and is an effective inhibitor of tumour-associated angiogenesis in several murine mouse models (Visentin et al., 2006). Furthermore, the antibody blocks EC migration and capillary formation as well as inhibited blood vessel formation (Visentin et al., 2006). Treatment of mice with established breast, ovarian or lung adenocarcinoma xenograft tumours with an anti-S1P antibody significantly reduces tumour volumes (Visentin et al., 2006). Sphingomab functions as a molecular sponge that absorbs S1P, which would stimulate EC migration, proliferation and tumour-supportive neovascularization. Further investigations could show that the S1P antibody inhibits angiogenesis and sub-retinal fibrosis in a mouse model (Caballero et al., 2009). After successful characterization of this murine monoclonal antibody LT1002, a humanized variant (Sonepcizumab, LT1009) could be generated with potential clinical use (O'Brien et al., 2009). The authors could show that both LT1002 and LT1009 have a high affinity and specificity for S1P and that LT1009 – as humanized antibody – might have a therapeutic potential in patients where pathological S1P levels are involved in disease progression (O'Brien et al., 2009).

Decreasing versus increasing S1P content

A new approach has been based on the principle of reducing free S1P content in the blood flow (as described previously with the anti-S1P antibody) using other clean-up technologies for S1P. Recently, phosphate-capture molecule (Phos-tag) strategies were used to enrich S1P out of plasma samples which could be detected by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry and quantified using an internal standard (Morishige et al., 2010). The authors proposed a routine method for analysing S1P level in many clinical samples.

In contrast to the depletion strategy of S1P, the stimulation of S1P signalling is also beneficial, as based on the anti-apoptotic actions of S1P described previously. Diab et al. found recently that the stimulation of S1P signalling was sufficient to counteract the deleterious effects of ceramide in emphysema (Diab et al., 2010). A local increase of the S1P content could be obtained by the use of S1P-containing microparticles. The authors proposed a promising strategy for therapeutical stimulation of post-ischaemic angiogenesis (Qi et al., 2010).

Sphk inhibitors

To date, different studies exist that propose a beneficial effect of Sphk inhibition in anti-tumour therapy (French et al., 2003). Therefore, in 2008 Takabe and co-workers validated natural products as inhibitors of Sphk, which might have therapeutic potential (Takabe et al., 2008). Others used a synthetic synthesis strategy to evaluate sphingosine analogues as inhibitors of Sphk (Wong et al., 2009). Concerning the effect of Sphk inhibition in other diseases than cancer, e.g. vascular disease and inflammation, only few data exist so far. Recently, Mathews et al. identified a new class of Sphk inhibitors (Mathews et al., 2010). They synthesized amide-based compounds and evaluated a potent dual Sphk inhibitor, a potent selective Sphk1 and a moderately potent selective Sphk2 inhibitor as potential drug targets for the treatment of hyper-proliferative diseases and inflammation (Mathews et al., 2010). For future proposal, more in vitro and in vivo data are necessary in order to understand the pharmacological potential by inhibiting Sphk in vascular disease. Sphk controls the cellular S1P level by affecting the equilibrium of anti-apoptotic S1P and its pro-apoptotic ceramide. The ratio of these metabolites has been considered to be critical for proliferation, survival and apoptosis of cells (Wymann and Schneiter, 2008), which predicts a role of Sphk in vascular remodelling processes seen in atherogenesis for example.

Conclusion and perspectives

The intensive research over the last several years could unmask several signalling pathways of sphingolipids, in particular S1P. Knockout studies ruled out important control function, e.g. in regard to angiogenesis, cardiovascular function and the immune system. S1P agonists/antagonists, antibodies against S1P as well as inhibitors for metabolic enzymes in S1P production/degradation have been developed and might be potential therapeutical targets for intervention. However, the overlapping expression of S1P receptor subtypes and redundant signalling pathways have complicated the assignment of specific functions to specific S1P receptors. Furthermore, the many contrary data available allow us to assume that fine-tuned regulation of S1P signalling is crucial for a physiological response. Just cite few: (i) Sphk activation protects ECs from apoptosis, but these Sphk-mediated protective effects were reversed by a dramatic increase in intracellular Sphk activity in ECs (Limaye et al., 2009); (ii) short-term administration of S1P1 agonists enhances EC barrier function but prolonged exposure dramatically impaired vascular leakage (Shea et al., 2010); (iii) S1P acts as intracellular and extracellular molecule; and (iv) cross-talk of S1P receptors with other signalling pathways.

All of these facts hamper intervention with minimized side effects, and only subtype-selective S1P receptor activation along with potency and efficacy of the substances ensure drug safety. Nevertheless, advantages and risks lay close together. Antagonism of S1P1 results in lymphocyte homing and silencing of immune reactions but might be toxic by enhancing vascular permeability causing pulmonary oedema (Sanna et al., 2006).

It is tempting to speculate whether or not medical chemistry incorporating high selectivity might be a successful therapeutical intervention, but a new concept in counter-vascular pathologies would still become apparent.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (MvdG; 339/5-1, 339/6-2, 339/6-3), Sonnenfeld Stiftung (MT, JP) and Deutsche Hochdruckliga (MS).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ABC

ATP-binding cassette

- ApoE

apolipoprotein E

- Bcl-2

B-cell lymphoma gene 2

- Bim

bisindolylmaleimide

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- Compound

5, 4-[(4-butoxyphenyl)thio]-2′-[4-(heptylthio)methyl]-2-hydroxyphenyl hydroxymethyl biphenyl-3-sulfonate

- CYM5442

2-(4-(5-(3,4-diethoxyphenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-3-yl)-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-yl amino ethanol

- EC

endothelial cell

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- EGF

endothelial growth factor

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- FAK

focal adhesion kinase

- FTY720

2-amino-2-(4-octylphenethyl) propane-1,3-diol

- FTY720-P

2-amino-2-(4-octylphenethyl) propane-1,3-diol phosphate

- GPCR

G-protein coupled receptor

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- HUVEC

human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- ICAM

inducible cell adhesion molecule

- IL-8

interleukin 8

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- IP3

inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate

- IRI

ischemia-reperfusion injury

- JNK

c-jun N-terminal kinase

- JTE013

1-[1,3-dimethyl-4-(2-methylethyl)-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridin-6-yl]-4-(3,5-dichloro-4-pyridinyl)-semicarbazide

- KRP-203

2-amonio-4-(2-chloro-4-(3-phenoxyphenylthio)phenyl)-2-(hydroxymethyl)butyl hydrogen phosphate

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MCP-1

monocyte chemoattractant protein-1

- MEF

mouse embrogenic fibroblast

- MEK

mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal regulated kinase kinase

- MI

myocardial infarction

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- NO

nitric oxide

- NOS

nitric oxid synthase

- PDGF

platelet-derived growth factor

- PE

phenylephrine

- PGE2

prostaglandine E2

- PLA2

phospholipase A2

- PI3

phosphoinositide 3

- PTEN

phosphatase and tensin homology

- PTX

pertussis toxin

- RANTES

regulated upon activation, normal t-cell expressed, and secreted

- Rho

Ras homolog gene family member

- ROCK

Ras homolog gene family member-associated protein kinase

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SA

serum albumin

- SEW2871

5-[4-phenyl-5-(trifluoromethyl)-2-thienyl]-3-[3-(trifluoromethyl) phenyl]-1,2,4-oxadiazole

- Sphk

sphingosine kinase

- S1P

sphingosine-1-phosphate

- sPLA2

secretory phospholipase A2

- SPP

sphingosine-1-phosphate phosphatase

- SR-BI

scavenger receptor class B type I

- TGF-ß

transforming growth factor-ß

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor α

- TLR

toll-like receptor

- TY-52156

1-(4-chlorophenylhydrazono)-1-(4-chlorophenylamino)-3,3-dimethyl-2-butanone

- VCAM

vascular cell adhesion molecule

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VLDL

very low density lipoprotein

- VPC23019

(R)-phosphoric acid mono-[2-amino-2-(3-octyl-phenylcarbamoyl)-ethyl] ester

- VPC23153

(R)-phosphoric acid mono-[2-amino-2-(6-octyl-1H-benzoimiazol-2-yl)-ethyl] ester

- VPC24191

(R)-phosphoric acid mono-[2-amino-3-(4-octyl-phenylamino)-propyl] ester

- VSMC

vascular smooth muscle cell

- W146

(R)-3-amino-4-(3-hexylphenylamino)-4-oxobutylphosphonic acid

- ZO-1

zonula occludens protein-1

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting Information

Teaching Materials; Figs 1–3 as PowerPoint slide.

References

- Alderton F, Rakhit S, Kong KC, Palmer T, Sambi B, Pyne S, et al. Tethering of the platelet-derived growth factor beta receptor to G-protein-coupled receptors. A novel platform for integrative signaling by these receptor classes in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:28578–28585. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102771200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alewijnse AE, Peters SL. Sphingolipid signalling in the cardiovascular system: good, bad or both? Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;585:292–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.02.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alewijnse AE, Peters SL, Michel MC. Cardiovascular effects of sphingosine-1-phosphate and other sphingomyelin metabolites. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;143:666–684. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allende ML, Proia RL. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors and the development of the vascular system. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1582:222–227. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00175-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allende ML, Yamashita T, Proia RL. G-protein-coupled receptor S1P1 acts within endothelial cells to regulate vascular maturation. Blood. 2003;102:3665–3667. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allende ML, Sasaki T, Kawai H, Olivera A, Mi Y, van Echten-Deckert G, et al. Mice deficient in sphingosine kinase 1 are rendered lymphopenic by FTY720. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:52487–52492. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406512200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An S, Zheng Y, Bleu T. Sphingosine 1-phosphate-induced cell proliferation, survival, and related signaling events mediated by G protein-coupled receptors Edg3 and Edg5. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:288–296. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anelli V, Gault CR, Snider AJ, Obeid LM. Role of sphingosine kinase-1 in paracrine/transcellular angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis in vitro. FASEB J. 2010;24:2727–2738. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-150540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argraves KM, Argraves WS. HDL serves as a S1P signaling platform mediating a multitude of cardiovascular effects. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:2325–2333. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R700011-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argraves KM, Wilkerson BA, Argraves WS, Fleming PA, Obeid LM, Drake CJ. Sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling promotes critical migratory events in vasculogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:50580–50590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404432200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auge N, Nikolova-Karakashian M, Carpentier S, Parthasarathy S, Negre-Salvayre A, Salvayre R, et al. Role of sphingosine 1-phosphate in the mitogenesis induced by oxidized low density lipoprotein in smooth muscle cells via activation of sphingomyelinase, ceramidase, and sphingosine kinase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21533–21538. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auge N, Negre-Salvayre A, Salvayre R, Levade T. Sphingomyelin metabolites in vascular cell signaling and atherogenesis. Prog Lipid Res. 2000;39:207–229. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(00)00007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad AS, Ye H, Huang L, Li L, Foss FW, Jr, Macdonald TL, et al. Selective sphingosine 1-phosphate 1 receptor activation reduces ischemia-reperfusion injury in mouse kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290:F1516–F1524. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00311.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajwa A, Jo S-K, Ye H, Huang L, Dondeti KR, Rosin DL, et al. Activation of sphingosine-1-phosphate 1 receptor in the proximal tubule protects against ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:955–965. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009060662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthasar S, Bergelin N, Lof C, Vainio M, Andersson S, Tornquist K. Interactions between sphingosine-1-phosphate and vascular endothelial growth factor signalling in ML-1 follicular thyroid carcinoma cells. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008;15:521–534. doi: 10.1677/ERC-07-0253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudhuin LM, Jiang Y, Zaslavsky A, Ishii I, Chun J, Xu Y. S1P3-mediated Akt activation and cross-talk with platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) FASEB J. 2004;18:341–343. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0302fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumruker T, Billich A, Brinkmann V. FTY720, an immunomodulatory sphingolipid mimetic: translation of a novel mechanism into clinical benefit in multiple sclerosis. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2007;16:283–289. doi: 10.1517/13543784.16.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergelin N, Lof C, Balthasar S, Kalhori V, Tornquist K. S1P1 and VEGFR-2 form a signaling complex with extracellularly regulated kinase 1/2 and protein kinase C-alpha regulating ML-1 thyroid carcinoma cell migration. Endocrinology. 2010;151:2994–3005. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berliner JA, Navab M, Fogelman AM, Frank JS, Demer LL, Edwards PA, et al. Atherosclerosis: basic mechanisms. Oxidation, inflammation, and genetics. Circulation. 1995;91:2488–2496. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.9.2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birgbauer E, Chun J. New developments in the biological functions of lysophospholipids. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:2695–2701. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6155-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff A, Czyborra P, Meyer Zu Heringdorf D, Jakobs KH, Michel MC. Sphingosine-1-phosphate reduces rat renal and mesenteric blood flow in vivo in a pertussis toxin-sensitive manner. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:1878–1883. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bode C, Sensken SC, Peest U, Beutel G, Thol F, Levkau B, et al. Erythrocytes serve as a reservoir for cellular and extracellular sphingosine 1-phosphate. J Cell Biochem. 2010;109:1232–1243. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boguslawski G, Grogg JR, Welch Z, Ciechanowicz S, Sliva D, Kovala AT, et al. Migration of vascular smooth muscle cells induced by sphingosine 1-phosphate and related lipids: potential role in the angiogenic response. Exp Cell Res. 2002;274:264–274. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolick DT, Srinivasan S, Kim KW, Hatley ME, Clemens JJ, Whetzel A, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate prevents tumor necrosis factor-{alpha}-mediated monocyte adhesion to aortic endothelium in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:976–981. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000162171.30089.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolli MH, Abele S, Binkert C, Bravo R, Buchmann S, Bur D, et al. 2-imino-thiazolidin-4-one derivatives as potent, orally active S1P1 receptor agonists. J Med Chem. 2010;53:4198–4211. doi: 10.1021/jm100181s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolz SS, Vogel L, Sollinger D, Derwand R, Boer C, Pitson SM, et al. Sphingosine kinase modulates microvascular tone and myogenic responses through activation of RhoA/Rho kinase. Circulation. 2003;108:342–347. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000080324.12530.0D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornfeldt KE, Graves LM, Raines EW, Igarashi Y, Wayman G, Yamamura S, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate inhibits PDGF-induced chemotaxis of human arterial smooth muscle cells: spatial and temporal modulation of PDGF chemotactic signal transduction. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:193–206. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.1.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]