Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

Chalepensin is a pharmacologically active furanocoumarin compound found in rue, a medicinal herb. Here we have investigated the inhibitory effects of chalepensin on cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2A6 in vitro and in vivo.

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH

Mechanism-based inhibition was studied in vitro using human liver microsomes and bacterial membranes expressing genetic variants of human CYP2A6. Effects in vivo were studied in C57BL/6J mice. CYP2A6 activity was assayed as coumarin 7-hydroxylation (CH) using HPLC and fluorescence measurements. Metabolism of chalepensin was assessed with liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS).

KEY RESULTS

CYP2A6.1, without pre-incubation with NADPH, was competitively inhibited by chalepensin. After pre-incubation with NADPH, inhibition by chalepensin was increased (IC50 value decreased by 98%). This time-dependent inactivation (kinact 0.044 min−1; KI 2.64 µM) caused the loss of spectrally detectable P450 content and was diminished by known inhibitors of CYP2A6, pilocarpine or tranylcypromine, and by glutathione conjugation. LC/MS analysis of chalepensin metabolites suggested an unstable epoxide intermediate was formed, identified as the corresponding dihydrodiol, which was then conjugated with glutathione. Compared with the wild-type CYP2A6.1, the isoforms CYP2A6.7 and CYP2A6.10 were less inhibited. In mouse liver microsomes, pre-incubation enhanced inhibition of CH activity. Oral administration of chalepensin to mice reduced hepatic CH activity ex vivo.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

Chalepensin was a substrate and a mechanism-based inhibitor of human CYP2A6. Formation of an epoxide could be a key step in this inactivation. ‘Poor metabolizers’ carrying CYP2A6*7 or *10 may be less susceptible to inhibition by chalepensin. Given in vivo, chalepensin decreased CYP2A activity in mice.

Keywords: chalepensin, CYP2A6, inhibition, mechanism-based, genotype

Introduction

In human liver (HL), cytochrome P450 (P450) 2A6 (CYP2A6) constitutes <1% to 10% of the total P450 content (Shimada et al., 1994) and is the major P450 form responsible for 7-hydroxylation of coumarin (Miles et al., 1990; Raunio et al., 2001). CYP2A6 is involved in the oxidative metabolism of several therapeutic agents including halothane, valproic acid and losigamone and occupies a crucial role in the metabolism of nicotine. In addition, toxins, such as 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) and aflatoxin B1 are also substrates of CYP2A6. In the human fetus, high levels of CYP2A in olfactory mucosa have been linked to developmental toxicity (Gu et al., 2000). Physiological substrates of CYP2A6 include retinoic acid, arachidonic acid and progesterone (Du et al., 2004). Inhibition of CYP2A6 can lead to unwanted drug interactions or to protection against toxins. Similarly, altered metabolism of endogenous substrates can affect endogenous mediator systems.

Inter-individual variations in CYP2A6 activity are found in humans and genetic polymorphism is one of the important causes of these variations. The prevalence of ‘poor metabolizers’ in the Caucasian population is less than 1%, whereas the prevalence in Orientals is more common and can be up to 20% of the population (Mwenifumbo et al., 2005). At present, more than 20 polymorphic alleles of the CYP2A6 gene have been identified. The wild-type allele, CYP2A6*1 encodes the enzyme with full CYP2A6 activity. CYP2A6*2 and *3 encode inactive enzymes and the CYP2A6*4 allele deletes the whole CYP2A6 gene. Among alleles with amino acid substitution in the coding sequence which encode active enzymes, CYP2A6*7 and CYP2A6*10 have been reported to occur predominantly in Asian populations, including Taiwanese. The resulting CYP2A6 variants with different amino acids substitution have distinct catalytic activities towards different substrates and may show correspondingly distinct responses to any inhibitor (Ariyoshi et al., 2001; Nakajima et al., 2006a). The point mutations of CYP2A6*7 and *10 lead to amino acid substitutions of Ile471Thr in CYP2A6.7 and both Ile471Thr and Arg485Leu in CYP2A6.10. The coumarin 7-hydroxylation (CH) activity of recombinant CYP2A6.7 was 63% of that of CYP2A6.1 (CYP2A6) and the stability of CYP2A6.7 at 37°C was less than that of CYP2A6 (Ariyoshi et al., 2001). Nicotine oxidation activity of CYP2A6.7 was undetectable. For 8-hydroxylation of 1,7-dimethylxanthine, the Vmax of CYP2A6.7 and CYP2A6.10 was 12% and 13% of that of CYP2A6 respectively (Kimura et al., 2005). However, the inactivation of these variants by mechanism-based inhibitors has not been reported.

The furanocoumarin structure has been recognized as a common feature of one major class of mechanism-based inhibitors of CYP2A6. However, not all furanocoumarin derivatives caused this type of inhibition (Koenigs and Trager, 1998). For example, 8-methoxypsoralen (methoxsalen) but not 8-hydroxypsoralen caused mechanism-based inhibition. Chalepensin [3-(1′,1′-dimethylallyl)-psoralen, Figure 1] is a furanocoumarin from Ruta graveolens L. (Yuin Siang), known as rue, and has been widely used not only in Asia but also in Europe for the treatment of headache, wounds and rheumatics (Miguel, 2003). However, rue has been used as an emmenagogue and abortificient in Brazil and Spain and has caused fetal death in pregnant mice (de Freitas et al., 2005). Chalepensin appeared to be the active component causing this type of anti-fertility toxicity (Kong et al., 1989). Chalepensin induced cytotoxicity in A-549 (lung), MCF-7 (breast), HT-29 (colon) and A-498 (kidney) carcinoma cell lines with ED50 values of 13.8–37.4 µM (Anaya et al., 2005).

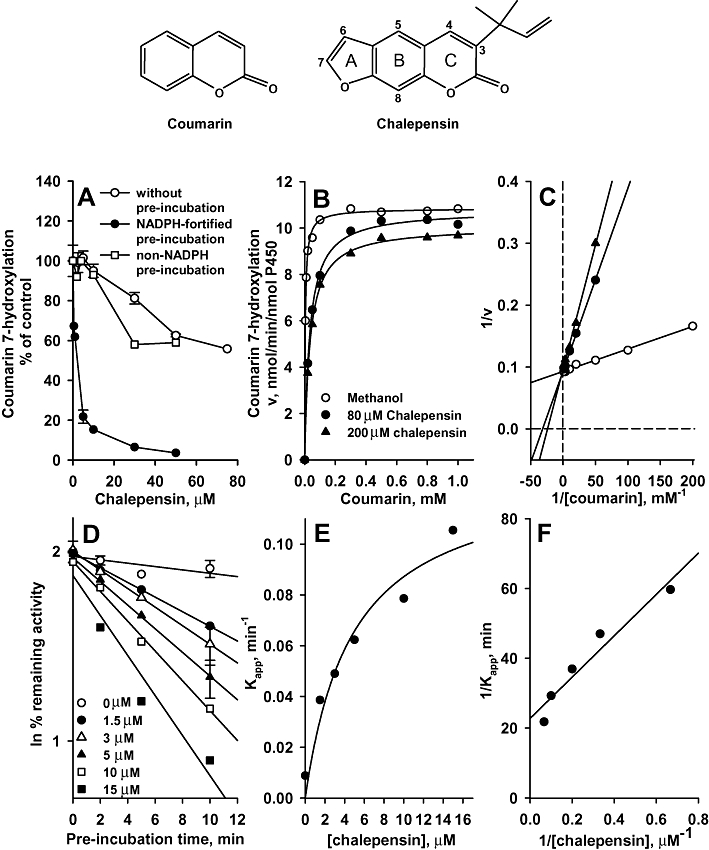

Figure 1.

At the top of the figure are shown the chemical structures of coumarin and chalepensin. In (A), Inhibition of coumarin 7-hydroxylation (CH) activity of recombinant CYP2A6 by chalepensin without pre-incubation or with pre-incubation in the presence or absence of a NADPH-generating system. E. coli membranes expressing CYP2A6 had CH activity of 5.11 nmol·min−1·nmol−1 P450. (B) v versus S plot. Chalepensin concentration employed were 0, 80 and 200 µM. (C) The Lineweaver-Burke plot. Chalepensin concentration employed were 0, 80 and 200 µM. (D) Time-dependent enhancement of the inhibitory effect of chalepensin on CYP2A6 activity. The percentage of remaining activity was related to the activity at time 0 (100%) of the vehicle control incubation. (E) The plot of inactivation rate versus chalepensin concentration. (F) The double-reciprocal plot of the relationship between inactivation rate and chalepensin concentration. Data represent the mean and mean ± SEM value of two and three separate experiments with duplicates respectively. P450, cytochrome P450.

We therefore assessed chalepensin as a substrate or as an inhibitor of CYP2A6. The inhibitory mechanism(s) and kinetics were characterized using human CYP2A6 genetic variants, expressed in E. coli and HL microsomes. The inhibitory effect of chalepensin on CYP2A in vivo was studied in mice. This species provides a useful model of human CYP2A6, because mouse Cyp2a5 has a similar amino acid sequence and is the major contributor to CH activity and nicotine oxidation in mice (Damaj et al., 2007). Thus, in vitro and in vivo effects of chalepensin on CH activity were studied in male C57BL/6J mice.

Methods

Chemicals and antibodies

Chalepensin was isolated and purified from the ethanol extract of aerial part of Rutagraveolens L. and structure of chalepensin was identified by NMR analysis (Reisch et al., 1968; Sayed et al., 2000). The purity of chalepensin was higher than 99% by NMR and HPLC analyses, Coumarin, glucose-6-phospate, glucose-6-phospate dehydrogenase, glutathione, 7-hydroxycoumarin, NADPH, tranylcypromine, and pilocarpine were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Acrylamide and N,N′-methelyn-bis-acrylamide (Bis) were purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc. (Hercules, CA, USA). Rabbit polyclonal antibody against human CYP2A6 was kindly provided by Dr. P. Souček (Praha, Czech Republic). Horseradish peroxide conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG was purchased from pierced Chemical Co. (PIERCE protein product-Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA).

Site-directed point mutation and preparation of bacterial membranes expressing CYP2A6 variants

A bicistronic CYP2A6*1 construct consisting of the coding sequence of a P450 followed by that of NADPH-P450 reductase was generously provided by Professor Fred P. Guengerich (Nashville, TN, USA). Polymorphic CYP2A6 was introduced into wild-type CYP2A6*1 cDNA by the primer-directed enzymatic amplification method following the instruction manual of Stratagene Co. (La Jolla, CA, USA) (Saiki et al., 1988). Oligonucleotide primer sets used for the site-directed mutagenesis were designed as a primer containing a mutated base and the sequence of mutated construct were determined (Mwenifumbo et al., 2005). Bicistronic CYP2A6* constructs were transformed to E. coli DH5α by electroporation using Gene Pulser II with Pulse Controller Plus following the instruction manual (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). P450 expression and membrane preparation were performed following the methods of Daigo et al. (2002) and Parikh et al. (1997) respectively.

Preparation of liver microsomes and cytosol, and enzyme assays

Experiments using HL samples were according to a protocol approved by the Department of Surgery and Residual Sample Bank in Taipei Veteran General Hospital (Taipei). Patients gave informed consent for experimental use of resected tissues and all tissues were coded to ensure anonymity. Samples of liver, free of tumour by histological examination, from hepatectomies of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma were collected. All patients (men, 68–87 years old) undergoing hepatectomy were without medication and fasted for at least 8 h, with only glucose or saline solutions given. In this study cohort, none of the sample donors received medication potentially affecting CYP2A6, such as pilocarpine, methoxsalen or rifampicin (Di et al., 2009). Results of histological examination revealed no tumour involvement.

All animal care and experimental protocols involving animals were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Research Institute of Chinese Medicine. Male C57BL/6J mice (5 weeks old, weighing 14–17 g) were purchased from the National Laboratory Animal Center, Taipei. Before experimentation, mice were allowed a 1-week acclimation period at the animal quarters with air conditioning, free access to laboratory rodent chow (no. 5P14; PMI Feeds Inc., Richmond, IN, USA) and water, with an automatically controlled photoperiod of 12 h light per day. Chalepensin was dissolved in corn oil and administered to mice through gastrogavage and the control group received the same amount of corn oil. Mice were killed by CO2 asphyxiation 24 h after the last treatment. Livers were removed, sectioned and stained with haematoxylin and eosin for histological examination. Liver sections (0.05 g) was deproteinized with perchloric acid and the chalepensin content was determined by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS) analysis and liver concentrations were calculated, using a liver density of 1.051 ± 0.013 g·mL−1 (Overmoyer et al., 1987).

Human liver microsomes and mouse liver microsomes and cytosols were prepared by differential centrifugation at 4°C following the method of Guengerich (1994) and Alvares and Mannering (1970) respectively. P450 content was determined using the spectrophotometric method, as described by Omura and Sato (1964). CH activity was determined in reaction mixtures containing, 0.1–0.2 mg·mL−1 microsomal protein or 20 pmol P450·mL−1 of recombinant CYP2A6 variants. Products of CH were analysed by HPLC with a fluorescence detector (Souček, 1999). 7-Ethoxycoumarin O-deethylation activity was determined following the method of Greenlee and Poland (1978) and glutathione S-transferase activity was determined following the method of Habig et al. (1974). Microsomal and cytosolic protein concentrations were determined by the method of Lowry et al. (1951).

Immunoblot analyses

Immunoblot analysis of microsomal CYP2A6 was performed using rabbit polyclonal antibody against human CYP2A6. Microsomal proteins (20 µg) were separated by electrophoresis on a 7.5% (w/v) polyacrylamide gel (Laemmli, 1970) and electrotransferred from the slab gel to a nitrocellulose membrane (Towbin et al., 1979). The immunoreactive proteins were detected using goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase and stained with a chemiluminescence detection kit (Perkin Elmer Life and Anal. Sci., Shelton, CA, USA). Microsomal CYP2A6 protein content was quantified by linear regression analysis of bacterial membranes expressing CYP2A6.1 (0.2–1.0 pmol P450, r = 0.958). Band density was analysed by densitometry using ImageMaster (Pharmacia Biotech Ltd, Uppsala, Sweden)

Partition ratio determination

The partition ratio was estimated using the enzyme titration method (Silverman, 1995). Bacterial membranes expressing CYP2A6 (20 pmol P450·mL−1) were pre-incubated with chalepensin for 30 min in the presence of NADPH to ensure extensive inhibition. The remaining activity was plotted as the function of the molar ratio of chalepensin to CYP2A6. The turnover number (partition ratio + 1) was estimated as the intersection on the X-axis of lines established by regression of the linear portion within the low and high molar ratios of chalepensin to P450.

Liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry analyses of chalepensin metabolites

Chalepensin oxidation was performed in a reaction mixture containing 20 pmol P450, 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 0.2 mM chalepensin and a NADPH-generating system (Chou et al., 2010). The final volume of this incubation mixture was 0.5 mL and reaction was stopped by the addition of 50 µL of 0.3 M perchloric acid after incubation at 37°C for 30 min in a shaker. After centrifugation at 13 800×g for 5 min at room temperature, the supernatant was injected into an LC/MS system. LC/MS was carried out to measure the exact mass using Q-TOF mass spectrometer. Separation of chalepensin oxidation metabolites was performed using a HPLC system (Agilent 1200 series, Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a C18 column (Phenomenex, Synergi Polar-RP, 2.0 × 150 mm, 4 µm) at ambient temperature. Metabolites were eluted by a mobile phase consisting of a gradient mixed from solvent A (0.1% formic acid) and solvent B (acetonitrile) as follows: 0–1 min, 90% A and 10% B; 1–10 min, a linear gradient 22 min, a linear gradient from 50% A to 5% A and then return to the initial condition at a flow rate of 0.3 mL·min−1. An Agilent 6510 Q-TOF mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with dual electrospray ionization source was used. The TOF mass spectrometric data were acquired in the positive ion model. The conditions for mass spectra were as follows: ion spray voltage, 4.5 kV; MS TOF fragment or voltage, 150 V; MS TOF skimmer voltage, 65 V; and gas temperature, 300°C. MSn spectra were analysed using UPLC (Accela, ThermoFischer, GA, USA) equipped with a C18 column (Thermo BioBasic, 2.1 × 150 mm, 5 µm) and an LTQ mass spectrometer (Velos, ThermoFischer). The electrospray voltage was 4.0 kV. Metabolites were eluted by a mobile phase consisting of a gradient mixed from solvent A (0.1% formic acid) and solvent B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile) as follows: 0–3 min, 100% A; 3–20 min, a linear gradient from 100% A to 5% A and 95% B at a flow rate of 0.25 mL·min−1. The exact m/z-values of fragments of protonated glutathione conjugate were determined at electrospray and in source collision-induced dissociation fragmentation voltages of 4.0 kV and 15–50 V respectively (Exactive Orbitrap®, ThermoFischer).

Data and kinetic analyses

The concentration of chalepensin required for 50% inhibition of catalytic activities (IC50) was calculated by curve fitting (Grafit, Erithacus Software Ltd, Staines, UK). For competitive inhibition, kinetics of P450 activities were analysed following Michaelis–Menten methods. Values of velocities (v) at various substrate concentrations (S) were fitted by nonlinear least-squares regression, without weighting, following the equation for competitive inhibition: v = Vmax×S/{S+Km×[1 + (I/Ki)]} (Sigma Plot, Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, CA, USA). Vmax, Ki and I are the maximal velocity, inhibitor constant and chalepensin concentration respectively. The initial estimates of Ki values were obtained from Lineweaver-Burke plots. For mechanism-based inhibition, the inactivation rates (Kapp) at different chalepensin concentrations were determined as the slopes calculated by linear regression analysis of the plot of the ln [percent of remaining activity] against pre-incubation time. The kinact (maximal inactivation rate constant of chalepensin) and KI (chalepensin concentration required for half-maximal inactivation) values were estimated from nonlinear regression from the equation ln2Kapp = (kinactI)/(I +KI) with the initial values calculated from the double reciprocal plot of inactivation rate versus chalepensin concentration (Silverman, 1995).

Significance of group differences between values from control and treated animals was evaluated by Student's t-test; P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

The metabolism-dependence and kinetic analysis of the CYP2A6 inhibition by chalepensin

Pre-incubation with chalepensin alone, that is, without NADPH, inhibited CYP2A6-catalysed CH activity with an IC50 value of 82.2 ± 8.3 µM (Figure 1A). Pre-incubation of CYP2A6, with chalepensin and a NADPH-generating system, induced greater inhibition and the IC50 of chalepensin decreased to 1.4 ± 0.1 µM. The inhibitory effect of chalepensin on another CYP2A6 activity, 7-ethoxycoumarin O-deethylation, was tested (Yun et al., 1991) and here also pre-incubation with NADPH decreased the IC50 of chalepensin from 196.8 ± 42.0 to 14.9 ± 1.6 µM. For CH activity, Michaelis–Menten kinetic analysis generated a Km of 3.8 ± 0.3 µM and Vmax of 10.9 ± 0.1 nmol·min−1·nmol−1 P450, as control values in the absence of NADPH pre-incubation (Figure 1B). In the presence of 80 and 200 µM chalepensin, the Km values were increased to 33 ± 2 and 35 ± 1 µM respectively. In contrast, the Vmax values in the presence of chalepensin were minimally changed (at 80 µM, 10.8 ± 0.2 and at 200 µM, 10.1 ± 0.1 nmol·min−1·nmol−1 P450) (Figure 1B). The Lineweaver-Burke plot revealed that chalepensin competitively inhibited CYP2A6-catalysed CH activity (Figure 1C), with a Ki value of 15.0 ± 2.0 µM.

Pre-incubation with NADPH and chalepensin induced a time-dependent inactivation of CH activity with kinact of 0.049 ± 0.008 min−1 and apparent KI of 3.3 ± 1.3 µM (Figure 1D,E). Linear regression analysis of the double reciprocal plots for inactivation rate and chalepensin concentration generated kinact and apparent KI values for CYP2A6 of 0.044 min−1 and 2.6 µM respectively (Figure 1F).

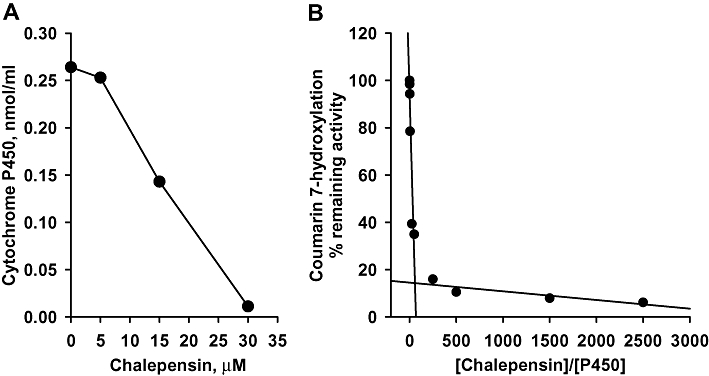

Protein inactivation and partition ratio

The binding of chalepensin to CYP2A6 did not immediately change the absorbance the cytochrome using wavelength scanning (data not shown). However, incubation of CYP2A6 with chalepensin at 37°C for 10 min did induce loss of cytochrome P450, as measured spectrophotometrically, and this decrease showed concentration-dependence (Figure 2A). After incubating CYP2A6 with increasing concentrations of chalepensin for 30 min to ensure inactivation was complete, titration of the remaining CH activity of CYP2A6 generated the partition ratio (representing the molar ratio of chalepensin metabolized per CYP2A6 inactivated) of 56 (the turnover number appeared to be 57, Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

(A) Loss of spectrophotometrically detected cytochrome P450 (P450) from recombinant CYP2A6 by pre-incubation with chalepensin in the presence of a NADPH-generating system. (B) The plot of remaining activity versus the molar ratio of chalepensin to CYP2A6. Solid lines represent the best fit as determined by linear regression analysis. Data represent the mean of two separate experiments with duplicated determinations in each experiment. The variations between two experiments were less than 10%.

Chalepensin-induced inhibition of activities in CYP2A6 and human liver microsomes was competitively antagonized by pilocarpine, tranylcypromine or glutathione

Pilocarpine is known to be a substrate for CYP2A6 and a competitive inhibitor of its activity (Kinonen et al., 1995; Endo et al., 2007) and tranylcypromine has been recognized as a potent competitive inhibitor of CYP2A6 (Draper et al., 1997). Using pre-incubation of CYP2A6 with chalepensin and NADPH, addition of either pilocarpine or tranylcypromine blocked the mechanism-based inhibition by chalepensin, in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 3A).

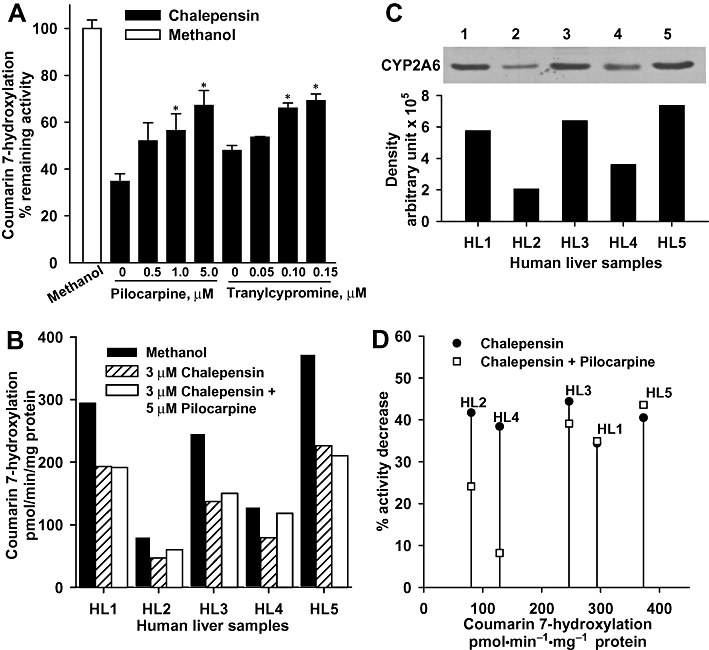

Figure 3.

(A) Effect of pilocarpine or tranylcypromine on chalepensin-mediated inactivation of CYP2A6. Recombinant human CYP2A6 was incubated concurrently with 3 µM chalepensin and increasing concentrations of pilocarpine or tranylcypromine for 10 min at 37°C in the presence of NADPH-generating system. After pre-incubation, 20 µM coumarin was added and the remaining CH activity was determined. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of three separate experiments with duplicates. The same volume of methanol (vehicle) was added as a control. *P < 0.05, significantly different from the value in the absence of pilocarpine or tranylcypromine. (B) Effect of pilocarpine on the chalepensin-mediated inhibition of microsomal CH activity of human liver (HL) samples. (C) Protein level of CYP2A6 in the microsomal fraction was immuno-detected using rabbit polyclonal antibody against human CYP2A6 as described in the Methods. (D) Decrease of CH activity as a function of the original activities in HL samples after pre-incubation with NADPH and 3 µM chalepensin alone or concurrently with 3 µM chalepensin and 5 µM pilocarpine. CH, coumarin 7-hydroxylation.

In five HL samples, microsomal CH activity (expressed as nmol·min−1·mg−1 protein) showed up to fivefold variation between individuals (Figure 3B), whereas the microsomal CYP2A6 content determined immunochemically ranged over 9.7 (HL1), 3.4 (HL2), 10.7 (HL3), 6.0 (HL4) and 12.4 (HL5) pmol·mg−1 protein (Figure 3C). These two measures were linearly correlated (r = 0.961). Pre-incubation of HL microsomes with 3 µM chalepensin in the presence of a NADPH-generating system resulted in 34–44% decrease of CH activity (Figure 3B). However, adding pilocarpine to this pre-incubation protected the CH activity in three of the HL samples, with 76% (HL2) and 92% (HL4) and 61% (HL3) of the original CH activity surviving (Figure 3B,D). However, the presence of 5 µM pilocarpine was not enough to compete with chalepensin for the inhibition of CH activity in HL1 and HL5 samples, which had higher contents of CYP2A6 and higher CH activity.

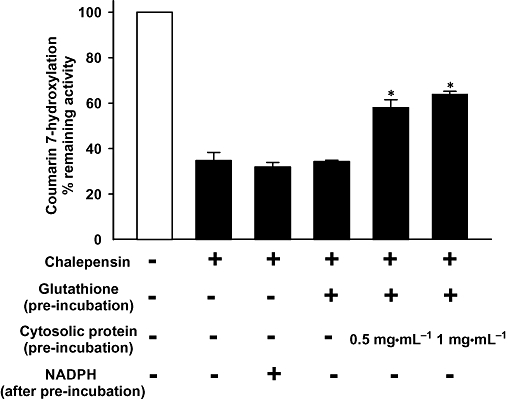

Tests with two variants of CYP2A6 showed that chalepensin decreased CH activity of CYP2A6.7 in a concentration-dependent manner but with an IC50 higher than 100 µM but with CYP2A6.10, the CH activity was not affected at all on pre-incubation with chalepensin (Figure 4). To prevent the depletion of NADPH during pre-incubation, additional NADPH was added after pre-incubation. The activity remaining was the same, with or without additional NADPH supply (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Inhibition of CH activities of recombinant CYP2A6.7 and CYP2A6.10 after pre-incubation with NADPH and chalepensin. In the absence of chalepensin, CH activity in membranes expressing CYP2A6.7 and CYP2A6.10 were 1.79 and 0.05 nmol·min−1·nmol−1 P450 after pre-incubation with vehicle respectively. Data represent the mean of two separate experiments with duplicate determinations in each experiment. The variations between two experiments were less than 10%. CH, coumarin 7-hydroxylation; P450, cytochrome P450.

Figure 5.

Decreased inhibitory effect of chalepensin (3 µM) on CYP2A6 by incubation with glutathione and glutathione S-transferase. Effects of chalepensin on CH activity of CYP2A6 was determined under various incubation conditions as indicated in the figure. For the conjugation reaction, glutathione (5 mM) and mouse liver cytosol (a source of glutathione S-transferase activity: 10.1 µmol·min−1·mg−1 protein) were included in the pre-incubation mixture and incubated at 37°C for 10 min. The same concentration of methanol was present in the control incubation. After pre-incubation, the remaining CH activity was determined with or without additional 0.1 mM NADPH. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of three or four determinations. *P < 0.05 significantly different from inactivation with chalepensin only. CH, coumarin 7-hydroxylation.

Adding glutathione alone to the pre-incubation mixture did not reduce the inactivation of CYP2A6, but inactivation could be prevented by the addition of glutathione with mouse liver cytosol as a source of glutathione S-transferase. Our preparation of mouse liver cytosol had a glutathione S-transferase activity of 10.1 µmol·min−1·mg−1 protein towards 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene.

Identification of the oxidized metabolites of chalepensin and its glutathione conjugates

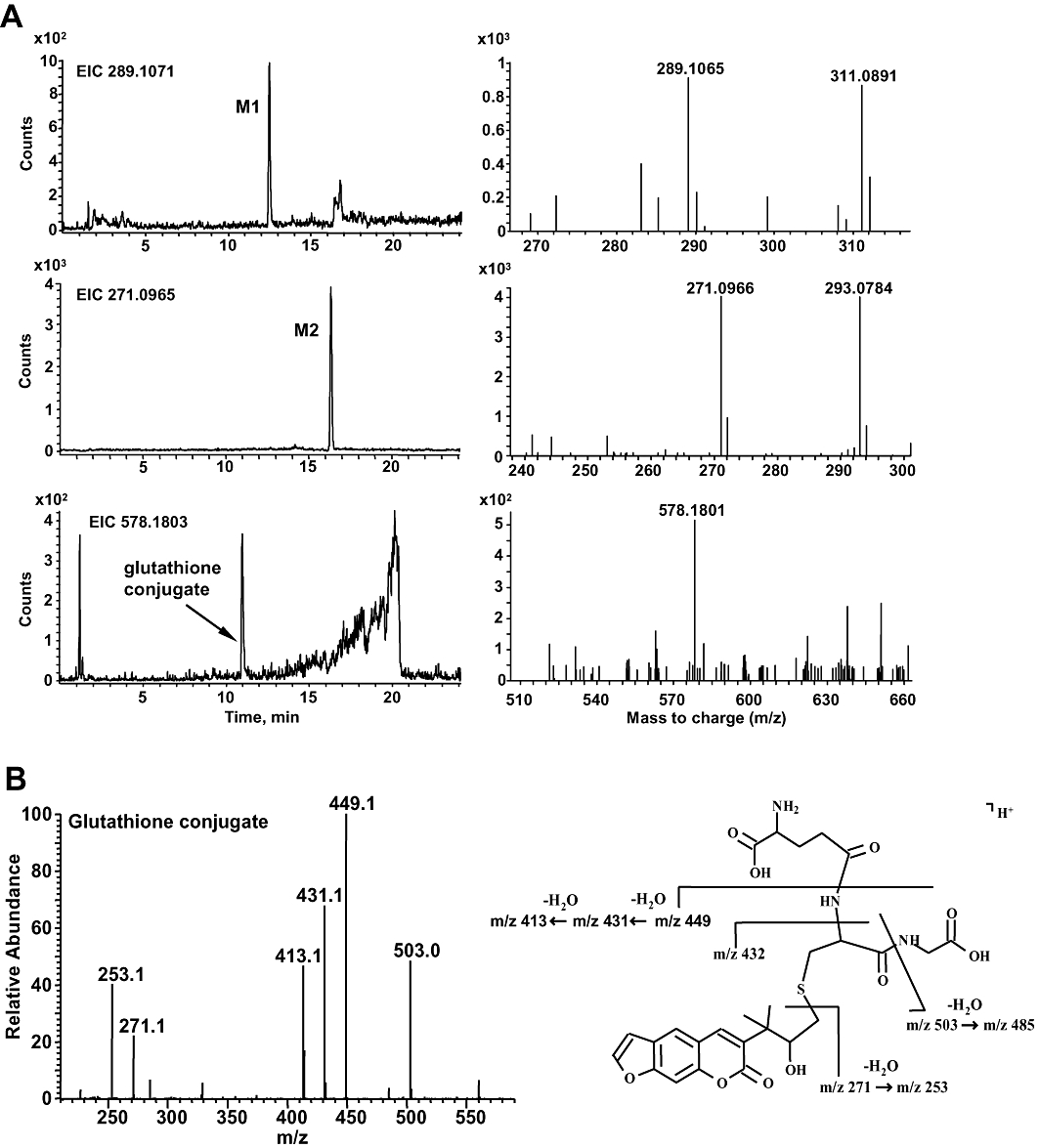

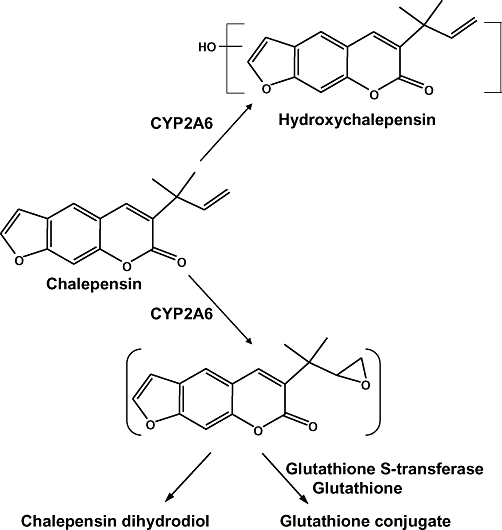

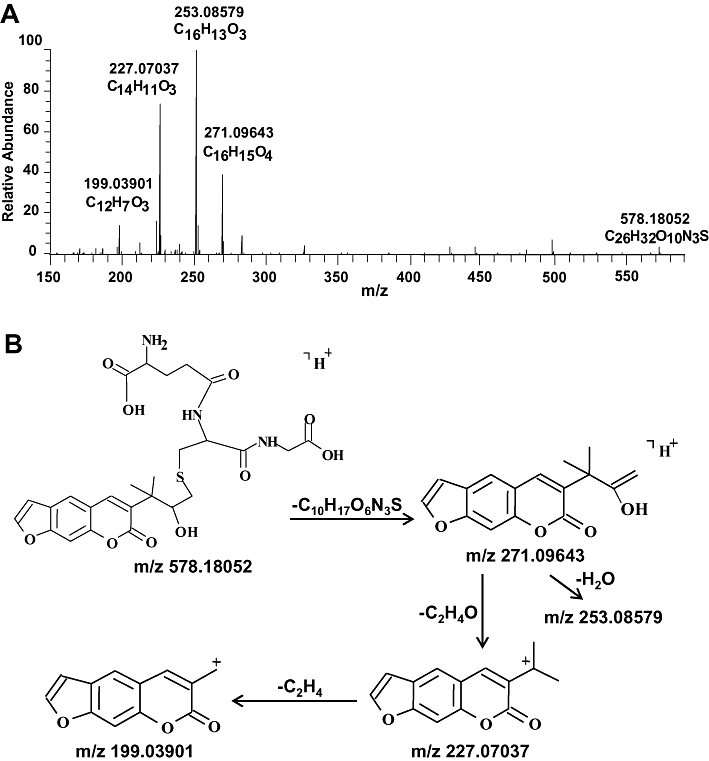

Two metabolites (M1, M2) were identified from LC/MS analyses of the products generated from CYP2A6-catalysed oxidation of chalepensin. M1, which appeared at 12.6 min in the chromatogram had the [M+H]+ ion at m/z of 289.1065, indicating the formation of a dihydrodiol metabolite (Figures 6A and 9). The sodium salt of M1 with the [M+H]+ ion at m/z 311.0891 was detected. Metabolite M2, which appeared at 16.3 min in the chromatogram had a [M+H]+ ion at m/z of 271.0966, indicating the formation of monohydroxylated metabolite. The sodium salt of M2 with the [M+H]+ ion at m/z of 293.0784 was observed. To elucidate the generation of dihydrodiol metabolite from the unstable epoxide metabolite, mouse liver cytosol was used as a source of glutathione S-transferase for the conjugation of epoxide with glutathione. The theoretical [M+H]+ ion at m/z of 578.1803 corresponds to the mass of chalepensin with the addition of one molecule of glutathione and one hydroxyl group. The glutathione conjugate with a [M+H]+ ion at m/z of 578.1801 appeared at 11.0 min in the chromatogram. Further MSn analysis showed the fragmentation ions of 199 and 171, consistent with the presence of hydroxychalepensin and chalepensin dihydrodiol with the parent compound, chalepensin (Table 1). The MS/MS fragmentation pattern of the glutathione conjugate indicated the conjugation of glutathione with epoxide to form the hydroxy-glutathione chalepensin (Figure 6B). Determination of the m/z-values of the collision-induced fragmentation ions of protonated glutathione conjugate (m/z = 578.18052) mainly generated ions with m/z of 271.09643, 253.08579, 227.07037 and 199.03901 (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

(A) LC/MS chromatograms of chalepensin and its metabolites. The base peak chromatograms were obtained from LC/MS analysis of the metabolite formation in the incubation of CYP2A6 with 0.2 mM chalepensin in the presence of a NADPH-generating system. Panels on the left show the LC-TOF MS chromatograms of selected precursor ions with [M+H]+ m/z at 255.1016 (chalepensin), 289.1071 (M1) and 271.0965 (M2). The formation of a glutathione conjugate with [M+H]+ m/z at 578.1803 was detected in another reaction mixture containing additional mouse liver cytosol and glutathione. The corresponding TOF MS spectra are shown on the right. (B) The MS/MS spectrum and proposed electrospray ionized fragments of hydroxy-glutathione chalepensin. LC/MS, liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry.

Figure 9.

Proposed metabolic pathways of chalepensin.

Table 1.

The m/z of LC/ESI-MSn of the oxidation and glutathione conjugation products of chalepensin oxidation catalysed by P450 2A6

| Fragmentation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | [M+H]+ | MS/MS | MS3 | MS4 |

| Chalepensin | 255 | 199 | 171,155, 143,127,115 | n.d. |

| 213 | 185,157,141,129,115 | |||

| Hydroxychalepensin | 271 | 227 | 199 | 171,155,143,127,115 |

| Chalepensin dihydrodiol | 289 | 271 | 227 | 199,171 |

| Hydroxy-glutathione chalepensin | 578 | 449 | 431,413,271,253 | |

| 431 | 413,253 | 225a | ||

| 271 | 253 | |||

| 227 | ||||

| 503,413,253 | ||||

The fragment shown in the result of MS4 analysis was the fragmentation from the fragment with m/z of 253 of MS3 analysis.

ESI, electrospray ionization; LC/MS, liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry; n.d., not determined; P450, cytochrome P450.

Figure 7.

(A) Mass spectrum of protonated hydroxy-glutathione chalepensin ([M+H]+), recorded with Orbitrap® instrument. Glutathione conjugation of the epoxidation metabolite of chalepensin was performed as described in the Methods. (B) Proposed collision-induced dissociation fragments of hydroxy-glutathione chalepensin.

In vitro and in vivo inactivation of CYP2A in C57BL/6J mice

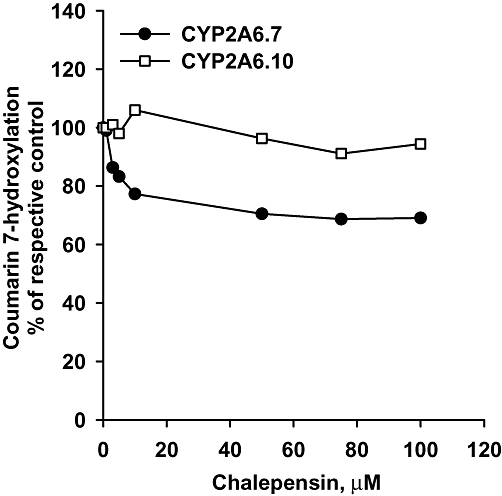

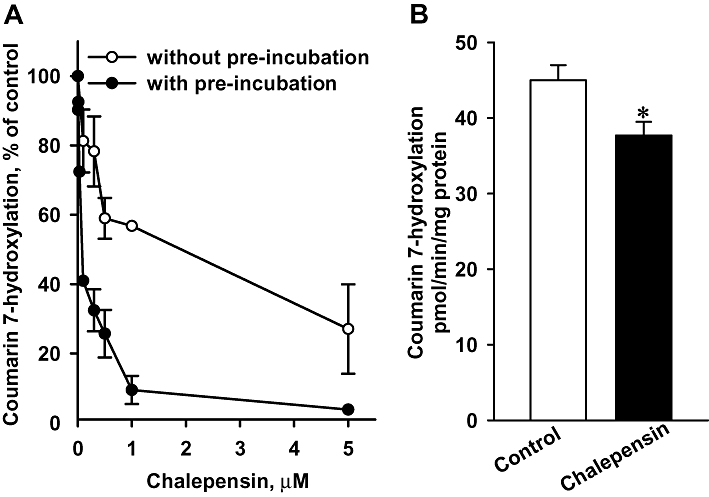

In vitro analysis using mouse liver microsomes showed that chalepensin inhibited CH activity with an IC50 value of 1.13 ± 0.15 µM without NADPH pre-incubation (Figure 8A). With NADPH pre-incubation, the IC50 value of chalepensin was reduced to 0.10 ± 0.01 µM. Because herbal medicines are generally used for 1 week in general and the contents of chalepensin in the subcritical extracts of rue leaves (6.6%) and stem (13%) (Stashenko et al., 2000), mice were treated with a daily dose of 10 mg·kg−1 by gastrogavage for 1 week. In chalepensin-treated mice, determination of hepatic content of chalepensin revealed that there were 1.36 ± 0.07 nmol chalepensin (g liver)−1, which was equivalent to 1.43 ± 0.08 µM assuming a density of 1.051 g·mL−1 (Overmoyer et al., 1987). Mouse body and liver weights were not affected by chalepensin treatment. Histological examination of liver section stained by haematoxylin and eosin staining of liver resection did not reveal any abnormalities (data not shown). Chalepensin treatment in vivo significantly decreased CH activity in mouse liver measured ex vivo by 16% (Figure 8B).

Figure 8.

(A) In vitro inhibition of microsomal CH activity from mouse liver, by chalepensin with or without NADPH pre-incubation. Data represent the mean ± SEM of three mice. (B) Effect of chalepensin on CH activity in C57BL/6J mice in vivo. Mice were treated with 10 mg·kg−1·day−1 chalepensin for 7 days. Data represent the mean ± SEM of eight and six mice in control and chalepensin-treated groups respectively. *P < 0.05, significantly different from control. CH, coumarin 7-hydroxylation.

Discussion and conclusions

Furanocoumarins are widely distributed in the plant kingdom including a variety of medicinal plants and foods (Anderson and Voorhees, 1980). Derivatives in this group showed distinct pharmacological effects and toxicities (Koenigs and Trager, 1998; Guo and Yamazoe, 2004). Due to their structural similarity to coumarin, some furanocoumarins have been identified as mechanism-based inhibitors of the wild-type CYP2A6. The differences in the side chain of furanocoumarin derivatives resulted in differential inhibitory effects and mechanisms. Our results demonstrated that the pharmacologically active herbal ingredient, chalepensin, was both a substrate and a mechanism-based inhibitor of CYP2A6. After pre-incubation of CYP2A6 with chalepensin in the presence of NADPH, the inhibitory effect of chalepensin on CH activity was markedly enhanced, indicating that this enhanced inhibition was dependent on metabolism of chalepensin. Similarly, enhanced inhibition was also observed when 7-ethoxycoumarin was used as a CYP2A6 substrate. The decrease of CH activity of CYP2A6 induced by chalepensin was accompanied by a corresponding loss in spectral content of P450, which is consistent with a mechanism-based inhibition. In the absence of pre-incubation with NADPH, chalepensin competitively inhibited CYP2A6 activity, using coumarin as a substrate, with an increased Km and unchanged Vmax. After pre-incubation with NADPH, the mechanism-based inhibition of CYP2A6 activity by chalepensin was blocked by competition with another CYP2A6 substrate, pilocarpine, in a concentration-dependent manner. These results indicate that chalepensin was able to bind to or bind very close to the substrate binding site(s) of CYP2A6 for coumarin and pilocarpine. In the presence of NADPH, the efficiency of enzyme inactivation by chalepensin, calculated as the ratio of kinact to KI was 16 min−1 mM−1. This value was smaller than that of a well-known potent inactivator of CYP2A6, another furanocoumarin, 8-methoxypsoralen (methoxsalen; Koenigs et al., 1997). Chalepensin is 3-(1′,1′-dimethylallyl)-psoralen and although the presence of the 1′,1′-dimethylallyl group may provide an additional epoxidation site, this bulky addition may cause steric hindrance and reduced the inactivation efficiency. However, the partition ratio for the inactivation by chalepensin was comparable with that by other furanocoumarins showing mechanism-based inhibition (Koenigs and Trager, 1998). The IC50 value of chalepensin for mechanism-based inhibition was only about 4% to 10% of the ED50 values for causing cytotoxicity in carcinoma cell lines (Anaya et al., 2005) and it is thus possible that inactivation of CYP2A6 may occur during the pharmacological and toxicological events caused by chalepensin. Chalepensin-induced toxicity through CYP2A6 inactivation may be of significance especially in target organs expressing CYP2A6, such as liver, ovary, uterus and testis (Nakajima et al., 2006b). It will be of interest to elucidate the contribution of this inactivation to chalepensin-induced toxicity towards the reproductive system.

In five HL samples, the individual CYP2A6 activities and protein levels varied over a fivefold range. However, microsomal CH activities were linearly related to the CYP2A6 protein levels in these liver samples. HL samples 2 and 4 had lower levels of CYP2A6 protein than HL samples 1, 3 and 5. In terms of chalepensin metabolism and the consequent mechanism-based inhibition, pilocarpine at 5 µM was an effective inhibitor of chalepensin metabolism and diminished the inhibitory effects in two HL samples, HL 2 and 4, but was not effective in HL 1, 3 and 5. Inhibition in HL microsomes is more complex than that with the recombinant CYP2A6. Individual differences in response can be attributed to several factors including the presence of other P450 forms, genetic polymorphism, medical care and disease. In addition, the IC50 value for a competitive inhibition is dependent on enzyme level. Thus, the higher CYP2A6 content could be one of the possible factors for the lack of efficient competition by pilocarpine. The variations of CH activities in these liver samples were less than 44% when activities were expressed as product formation rate per nmole CYP2A6. Chalepensin caused similar inhibition (34–44% decreases) in these liver samples, suggesting that either chalepensin was at a saturating concentration or a similar metabolic efficiency for the formation of the active intermediates in all these liver samples. Although human blood and tissue samples were not available for genotype analysis, our studies of bacterial membranes expressing CYP2A6 genetic variants revealed that the IC50 values of chalepensin for CH activities of CYP2A6.7 and CYP2A6.10 were greater than that of CYP2A6. This result suggested that ‘poor metabolizers’ carrying CYP2A6*7 and *10 genotypes may be less affected by chalepensin-mediated inactivation of CYP2A6.

As found in the metabolism of methoxsalen, hydroxy and dihydrodiol metabolites of chalepensin were formed and identified by LC/MS analysis. The dihydrodiol metabolite was presumably generated from the hydrolysis of an unstable epoxide intermediate (see Figure 9). Such epoxide formation was further supported by the detection of a metabolite with the exact mass of the [M+H]+ equivalent to the addition of a monohydroxy group and a glutathione when the reaction mixture contained both glutathione and cytosol (as a source of glutathione S-transferase). After glutathione conjugation, the mechanism-based inhibitory effect of chalepensin was reduced, whereas glutathione alone did not prevent this inhibition. These results indicated that chalepensin could be oxidized by CYP2A6 to form an epoxide intermediate, which may then react with CYP2A6 and cause inactivation.

Molecular modelling and spectral analyses of furanocoumarins structurally related to methoxsalen suggested that there was a higher possibility of epoxidation at the furano moiety, as the carbonyl oxygens of coumarin and methoxsalen were oriented to form hydrogen bond with Asn297 and the loss of aromaticity was monitored from the spectral property (Koenigs and Trager, 1998; Yano et al., 2005). However, recent report of the detection of interstrand DNA adducts indicated the possibility of bond formation between methoxsalen and nucleotide through both the furan and coumarin rings of methoxsalen, in the presence of UVA irradiation (Cao et al., 2008). This in turn suggested the accessibility of both the furano and coumarin rings to the active site of CYP2A6. Study of a pyranocoumarin, decursinol angelate, suggested that the butenyl moiety of the angeloyl group at the pyrano moiety was accessible for epoxidation to cause mechanism-based inhibition (Yoo et al., 2007). Thus, in our experiments, apart from the possible epoxidation of the furano moiety, the 1′,1′-dimethylallyl group of chalepensin may also provide another epoxidation site. Fragmentation of psoralen (furanocoumarin) generated a main product ion with m/z of 131, which was not found in psoralen dihydrodiol due to the dihydrodiol formation at furan ring (Koenigs and Trager, 1998; Gu et al., 2009). Unexpectedly, this ion was not found in the fragmentation ions of chalepensin. Different ionization methods and the presence of the dimethylallyl side chain may change the fragmentation of the furanocoumarin core. The sequential fragmentation ions with m/z of 199 and 171 of chalepensain were found in chalepensin and its hydroxylated and dihydrodiol metabolites, indicating that the core structure of chalepensin seems to be preserved. As only one glutathione conjugate was detected, there could be only one site for epoxidation. Determination of the exact m/z-values of glutathione conjugate fragmentation ions indicated that epoxidation occurred at the dimethylallyl side chain. The fragmentation was comparable for the exact m/z-values of dihydrodiol metabolite (data not shown). The chemical structure of this putative chalepensin epoxide could be further identified from large scale purification of chalepensin dihydrodiol or from a protein adduct.

Consistent with the inhibition of human CYP2A6, the inhibition of mouse liver microsomal CH activity by chalepensin also showed metabolism-dependence. The IC50 of chalepensin in mouse liver microsomes was only 1% and 10% of those of recombinant CYP2A6 with or without NADPH pre-incubation respectively. These findings showed that mouse Cyp2a5 was more sensitive to the inhibition by chalepensin than human CYP2A6. After treatment of mice with chalepensin in vivo, our results demonstrated that the corresponding liver microsomes from had CH activity significantly lower (16% decrease) than control untreated mice. This result revealed the extent of chalepensin inhibition of CYP2A in vivo. However, the in vivo treatment of mice resulted in a hepatic chalepensin concentration of 1.43 µM, which was higher than the IC50 value for the inhibition in vitro. The lower than expected level of inhibition of CH activity by chalepensin treatment in vivo may be due to other in vivo factors, such as the glutathione conjugation of the epoxide metabolite. The susceptibility of human CYP2A6 to chalepensin-mediated inhibition in vivo needs further investigation. Adverse effects due to CYP2A6 inactivation may need to be noted in patients taking chalepensin-containing herbs, such as rue. Details of the time- and dose-dependence as well as the modulatory mechanism in mice are being investigated now.

In summary, our results revealed that chalepensin was a suicide substrate of CYP2A6 and inactivated CYP2A6 in a mechanism-based manner. CYP2A function was decreased by chalepensin in vitro and in vivo. It revealed a potential xenobiotic interaction, which may result in either a beneficial effect, such as chemoprevention against tobacco toxicity or the herb–drug interaction for those drugs whose clearance is mainly dependent on CYP2A6. The inactivation of CYP2A6 was diminished by glutathione conjugation of an active metabolic intermediate, possibly the epoxide, derived from chalepensin. ‘Poor metabolizers’ carrying CYP2A6*7 and *10 genotypes may be less susceptible to chalepensin-mediated inactivation of CYP2A6.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants (NSC97-2320-B-077-009-MY3 and NSC99-2918-I-077-001) from the National Science Council, Taipei, Taiwan.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CH

coumarin 7-hydroxylation

- HL

human liver

- LC/MS

liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry

- NNK

4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone

- P450

cytochrome P450

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest are declared by the authors.

Supporting Information

Teaching Materials; Figs 1–9 as PowerPoint slide.

References

- Alvares AP, Mannering GJ. Two substrate kinetics of drug-metabolizing enzyme system of hepatic microsomes. Mol Pharmacol. 1970;6:206–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anaya AL, Macias-Rubalcava M, Cruz-Ortega R, Garcia-Santana C, Sánchez-Monterrubio PN, Hernández-Bautista BE, et al. Allelochemicals from Stauranthus perforatus, a Rutaceous tree of Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. Phytochem. 2005;66:487–494. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson TF, Voorhees JJ. Psoralen photochemotherapy of cutaneous disorders. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1980;20:235–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.20.040180.001315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariyoshi N, Sawamura Y, Kamataki T. A novel single nucleotide polymorphism altering stability and activity of CYP2A6. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2001;281:810–814. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao H, Hearst JE, Corash L, Wang Y. LC-MS/MS for the detection of DNA interstrand cross-links formed by 8-methoxypsoralen and UVA irradiation in human cells. Anal Chem. 2008;80:2932–2938. doi: 10.1021/ac7023969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou YC, Chung YT, Liu TY, Wang SY, Chau GY, Chi CW, et al. The oxidative metabolism of dimemorfan by human cytochrome P450 enzymes. J Pharm Sci. 2010;99:1063–1077. doi: 10.1002/jps.21866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daigo S, Takahashi Y, Fujieda M, Ariyoshi N, Yamazaki H, Koizumi W, et al. A novel mutant allele of the CYP2A6 gene (CYP2A6*11) found in a cancer patient who showed poor metabolic phenotype towards tegafur. Pharmacogenetics. 2002;12:299–306. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200206000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damaj MI, Siu ECK, Sellers EM, Tyndale RF, Martin BR. Inhibition of nicotine metabolism by methoxsalen: pharmacokinetic and pharmacological studies in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320:250–257. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.111237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di YM, Chow VDW, Yang LP, Zhou S. Structure, function, regulation and polymorphism of human cytochrome P450 2A6. Curr Drug Metab. 2009;10:754–780. doi: 10.2174/138920009789895507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper AJ, Madan A, Parkinson A. Inhibition of coumarin 7-hydroxylase activity in human liver microsomes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;341:47–61. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.9964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du L, Hoffman SMG, Keeney DS. Epidermal CYP2 family cytochrome P450. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;195:278–287. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo T, Ban M, Hirata K, Yamamoto A, Hara Y, Momose Y. Involvement of CYP2A6 in the formation of a novel metabolite, 3-hydroxypilocarpine, from pilocarpine in human liver microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2007;35:476–483. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.013425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Freitas TG, Augusto PM, Montanari T. Effect of Ruta graveolens L. on pregnant mice. Contraception. 2005;71:74–77. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenlee WF, Poland A. An improved assay of 7-ethoxycoumarin deethylase activity: induction of hepatic enzyme activity in C57BL/6J and DBA/2J mice by phenobarbital, 3-methylcholanthrene and 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1978;205:596–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J, Su T, Chen Y, Zhang QY, Ding X. Expression of biotransformation enzymes in human fetal olfactory mucosa: potential roles in developmental toxicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2000;165:158–162. doi: 10.1006/taap.2000.8923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Si D, Gaob J, Zeng Y, Liu C. Simultaneous quantification of psoralen and isopsoralen in rat plasma by ultra-performance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry and its application to a pharmacokinetic study after oral administration of Haigou Pill. J Chromatogr B. 2009;877:3137–3143. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guengerich FP. Preparation of microsomal and cytosolic fractions. In: Hayes AW, editor. Principles and Methods of Toxicology. 3rd edn. New York: Raven Press; 1994. pp. 1267–1268. [Google Scholar]

- Guo LQ, Yamazoe Y. Inhibition of cytochrome P450 by furanocoumarins in grapefruit juice and herbal medicines. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2004;25:129–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habig WH, Pabst MJ, Jascoby WB. Glutathione S-transferase: the first enzymatic step in mercapturic acid formation. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:7130–7139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M, Yamazaki H, Fujieda M, Kiyotani K, Honda G, Saruwatari J, et al. CYP2A6 is a principal enzyme involved in hydroxylation of 1,7-dimethylxanthine, a main caffeine metabolite, in humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005;33:1361–1366. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.004796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinonen T, Pasanen M, Gynther J, Poso A, Jrvinen T, Alhava E, et al. Competitive inhibition of coumarin 7-hydroxylation by pilocarpine and its interaction with mouse CYP2A5 and a human CYP2A6. Brit J Pharmacol. 1995;116:2625–2630. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb17217.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenigs LL, Trager WF. Mechanism-based inactivation of P450 2A6 by furanocoumarins. Biochemistry. 1998;37:10047–10061. doi: 10.1021/bi980003c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenigs LL, Peter RM, Thompson SJ, Rettie AE, Trager WF. Mechanism-based inactivation of human liver cytochrome P450 2A6 by 8-methoxysoralen. Drug Metab Dispos. 1997;25:1407–1415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong YC, Lau CP, Wat KH, Ng KH, But PPH, Cheng KF, et al. Antifertility principle of Ruta graveolens. Planta Med. 1989;55:176–178. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-961917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Roseborough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RL. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel ES. Rue (Ruta L., Rutaceae) in traditional Spain: frequency and distribution of its medicinal and symbolic applications. Economic Botany. 2003;57:231–244. [Google Scholar]

- Miles JS, McLaren AW, Forrester LM, Glancey MJ, Lang MA, Wolf CR. Identification of the human liver cytochrome P450 responsible for coumarin 7-hydroxylase activity. Biochem J. 1990;267:365–371. doi: 10.1042/bj2670365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwenifumbo JC, Myers MG, Wall TL, Lin S-K, Sellers EM, Tyndale RF. Ethnic variation in CYP2A6*7, CYP2A6*8 and CYP2A6*10 as assessed with a novel haplotyping method. Pharmacogenetic Genomic. 2005;15:189–192. doi: 10.1097/01213011-200503000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima M, Fukami T, Yamanaka H, Higashi E, Sakai H, Yoshida R, et al. Comprehensive evaluation of variability in nicotine metabolism and CYP2A6 polymorphic alleles in four ethnic populations. Clin Pharmacol Thera. 2006a;80:282–297. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima M, Itoh M, Sakai H, Fukami T, Katoh M, Yamazaki H, et al. CYP2A13 expressed in human bladder metabolically activates 4-aminobiphenyl. Int J Cancer. 2006b;19:2520–2526. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omura T, Sato R. The carbon monoxide-binding pigment of liver microsomes. I. Evidence for its hemoprotein nature. J Biol Chem. 1964;239:2370–2378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overmoyer BA, McLaren CE, Brittenham GM. Uniformity of liver denzity and nonheme (storage) iron distribution. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1987;111:549–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh A, Gillam EMJ, Guengerich FP. Drug metabolism by Escherichia coli expressing human cytochrome P450. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:784–788. doi: 10.1038/nbt0897-784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raunio H, Rautio A, Gullstn H, Pelkonen O. Polymorphisms of CYP2A6 and its practical consequences. Brit J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;52:357–363. doi: 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01500.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisch J, Szendrei K, Minker E, Novák I. Chalepensin, gravelliferon-methyläther und 3-(1′,1′-dimethylallyl)-herniarin aus den wurzeln von Ruta graveolens. Tetrahedron Lett. 1968;41:4395–4396. [Google Scholar]

- Saiki RK, Gelfand DH, Stoffel S, Schartf SJ, Higuchi R, Horn GT, et al. Primer-directed enzymatic amplification of DNA with a thermostable DNA polymerase. Science. 1988;239:487–491. doi: 10.1126/science.2448875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayed KE, Al-Said MS, El-Feraly FS, Ross SA. New quinoline alkaloids from Ruta chalepensis. J Nat Prod. 2000;63:995–997. doi: 10.1021/np000012y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada T, Yamazaki H, Mimura M, Inui Y, Guengerich FP. Interindividual variations in human liver cytochrome P-450 enzymes involved in the oxidation of drugs, carcinogens and toxic chemicals: studies with liver microsomes of 30 Japanese and 30 Caucassians. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;270:414–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman RB. Mechanism-based enzyme inactivators. Methods Enzymol. 1995;249:240–283. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)49038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souček P. Novel sensitive high-performance liquid chromatographic method for assay of coumarin 7-hydroxylation. J Chromatogr B. 1999;734:23–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stashenko EE, Acosta R, Martníez JR. High-resolution gas-chromatographic analysis of the secondary metabolites obtained by subcritical-fluid extraction from Colombian rue (Ruta graveolens L.) J Biochem Biophys Method. 2000;43:379–390. doi: 10.1016/s0165-022x(00)00079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano JK, Hsu MH, Griffin KJ, Stout CD, Johnson EF. Structures of human microsomal cytochrome P450 2A6 complexed with coumarin and methoxsalen. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:822–823. doi: 10.1038/nsmb971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo HH, Lee MW, Kim YC, Yun CH, Kim DH. Mechanism-based inactivation of human cytochrome P450 2A6 by decursinol angelate isolated from Angelica Gigas. Drug Metab Dispos. 2007;35:1759–1765. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.016584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun CH, Shimada T, Guengerich FP. Purification and characterization of human liver microsomal cytochrome P-450 2A6. Mol Pharmacol. 1991;40:679–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.