Abstract

Emergency medicine research conducted under the exception from informed consent (EFIC) regulation enables critical scientific advancements. When EFIC is proposed, there is a requirement for broad community consultation and public disclosure regarding the risks and benefits of the study. At the present time, no clear guidelines or standards exist for conducting and evaluating the community consultation and public disclosure.

This preliminary study tested the feasibility and acceptability of a new approach to community consultation and public disclosure for a large-scale EFIC trial by engaging community members in designing and conducting the strategies. The authors enrolled key community members (called Community Advocates for Research, or CARs) to use community-based participatory methods to design and implement community consultation and public disclosure.

By partnering with community members who represent target populations for the research study, this new approach has demonstrated a feasible community consultation and public disclosure plan with greater community participation and less cost than previous studies. In a community survey, the percentage of community members reporting having heard about the EFIC trial more than doubled after employing the new approach. This article discusses initial implementation and results.

INTRODUCTION

In 1996, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the Food and Drug Administration established the Final Rule, federal regulations 45 CFR 46 and 21 CFR 50.24, to address human subjects protection under very limited and specific research study conditions.1 The Final Rule pertains when it is not possible to obtain informed consent from a potential participant or a legally authorized representative for a study conducted under acute and life-threatening conditions with a narrow intervention window, and which offers potential benefit to the participant. To conduct such research, community consultation and public disclosure (CC/PD) are required to inform the community from which study participants are likely to be drawn, invite public comment, provide a mechanism to opt out of participation, and disseminate study results into the community. In essence, bi-directional communication is the core goal of community consultation and awareness the goal of public disclosure.2 Institutional review boards (IRBs) and principal investigators (PIs) have struggled with appropriate strategies that are time- and dollar-efficient, yet genuinely open channels of communication between the university and the community. While CC/PD are not a proxy for informed consent, the ethical principle of respect for persons compels a community consultation strategy that parallels the traditional individual informed consent procedure by providing culturally and educationally relevant information and a forum for discussion and questions. This preliminary study examines feasibility (i.e. can the model be implemented?), acceptability, and effectiveness (i.e., can the model strategies accomplish CC/PD goals in ways that are acceptable to investigators, IRB members, and community members?) of this new approach.

COMMON STRATEGIES FOR CC/PD

Successful communication with the community is not only demanded by the Final Rule but imperative to establishing and sustaining a trusting relationship with the community that the academic health center serves. It requires not only sharing of information about the study (public disclosure) but also bidirectional exchange (community consultation). Community consultation is a very different requirement for investigators and IRBs.3 Community consultation should be an information transfer regarding the proposed study and the risks and benefits. There is an exchange of ideas and understandings, and bi-directional communication between the investigators and the community.3,4 This process is “intended to ensure that the relevant communities contribute to the decision-making process…” and researchers obtain community feedback for the study.5 Some of the concerns investigators experience when planning community consultations are determining culturally appropriate (i.e., reach the target group), effective (i.e., actively engage the target group), and adequate (i.e., provide enough information) forums for this bi-directional communication.6 Often, because each traditional community consultation strategy has limitations, a combination of strategies is used.7,8,9 The commonly used strategies include newspaper ads, call-in lines, public forums, presentations, posters and patient notices in clinics, and television and radio announcements. 8

The challenge of community consultation and public disclosure is to do it well without exorbitant expenditure of research personnel time and dollars, and with minimal time necessary for IRB review.10 In addition, EFIC studies are usually multi-site, and each site’s IRB and research team devises specific local community consultation strategies.7,8,11 Table 1 lists the most common methods used for CC/PD in EFIC research and their potential limitations.

Table 1.

Common Community Consultation/Public Disclosure Strategies and Potential Limitations

| Community Consultation Strategy | Limitations |

|---|---|

Media Channels

|

Breadth of reach but not depth of information Do not know who is actually reached Timing determined by paper/radio/TV Can only address general issues Cannot focus message to sub groups Greater expense Language dependent Requires individuals to take action to provide input |

| Random digit dialing | “Hit and miss” households Many households do not have land lines Calls to cell phones may charge respondent, reducing response rates |

| Town hall meetings | Reaches whoever shows up Traditionally not well attended Do not know if attendees truly represent the larger community |

Join existing community group agendas

|

Cannot reach all groups May require targeted or limited message |

| Hotline, call-in | Requires staff and increases cost Limited access Usually addresses one person at a time |

| Website | Limited bi-directional communication May not be accessible to some subgroups (elderly, low literacy, etc.) Language dependent |

| Social networking site | Requires moderator and increases cost Cannot control content |

| Posters, flyers, bus placards | Limited amount of information can be provided Passive, no interaction Cannot determine reach or impact Reading level, language limitations Limited distribution or visibility |

Community Consultation Strategies for an Ongoing EFIC Trial

As an academic health center with a long history of emergency medicine research, our institution has participated in several EFIC research studies requiring CC/PD. Yet, as other institutions that conduct EFIC research have found, it is a struggle to do CC/PD well, with little definition of what is considered adequate. In a current EFIC study, the community consultation plan used several of the strategies shown in Table 1. The goal was to reach several groups that had a higher probability of being participants in the study, but to also reach the general population, who were also potential participants. It was considered that only 50% of the participants would have a prior health history making them likely to have an event and be enrolled. In addition to the problems listed in Table 1, we found that the cost of several media strategies limited their use. For example, one week of radio ads cost approximately $17,000. Table 2 shows our local costs per CC/PD strategy. One of the most cost-effective strategies was the placement of placards on the bus transit system; however, reach was limited to those who ride the bus and requires individuals to take action (call in or email) to obtain more information or share their opinions with the university. One cost that is difficult to quantify is personnel time to post flyers, make contacts for town halls, schedule meetings, and provide invitations to the meetings. The research staff for this EFIC study recorded over 1,000 man-hours spent in the design, implementation, conduct, and reporting of the CC/PD to the IRB.

Table 2.

Community Consultation Ads and Site-Specific Local Costs

| Strategy | Local Cost |

|---|---|

| Radio advertisements – 1 week | Approximately $17,000 |

| Metro newspaper advertisements | $2,000–5,000 per ad (depending on length & day) |

| TV advertisement | $10,000 |

| Local bi-weekly coupon mailing pack | Approximately $20,000 |

| Bus placards | $100/10 buses |

As in the literature, our study’s costs and strategies demonstrate that community consultation is a serious commitment of time and money.12 Completing this requirement to the satisfaction of the site IRB can be a hurdle for emergency medicine researchers who might not have experience in ways to effectively reach the community.

Considering the lack of proven methods for conducting CC/PD and concerns regarding the effectiveness, timeliness, and cost, a new model of university-community collaboration was developed. This model identifies, trains, and mobilizes key community leaders in new roles as “community advocates for research” (CARs) to support the ethical goals of CC/PD, and engages their specific target communities in bi-directional communication.

RECRUITMENT, MEETINGS, AND TRAINING

CARs Recruitment

This study was approved by our university IRB. For this preliminary study, ten individuals were recruited to be CARs. Because we were planning to gather information from the CARs during the study, they were considered study participants and were given and signed informed consent documents. These individuals were chosen because: 1) they had knowledge and understanding of the EFIC target population and its culture, traditions, beliefs, and/or disease condition of the research; 2) they had established communication channels with the target populations; and 3) they had respected positions within the community. The EFIC study that was underway involved seizure patients. It was anticipated that 50% of the individuals who would be enrolled in the study would have a history of seizures, while the other half would have no prior history. The CARs were therefore selected from both seizure advocacy organizations and groups thought to be at higher risk for seizures, as well as from organizations serving the general population. The enrollment processes for the CARs included investigator and staff meetings with potential CARs, phone calls, and then attendance at an orientation meeting where the EFIC study background, goals, and plans were presented.

Meetings

Quarterly meetings with research staff and CARs were planned. These meetings included training sessions scheduled to last 2.5 to 3 hours. In order to allow for the university team to learn more about the community and to promote the study within that community’s organization, meetings were held at organizations represented by the CARs. Although quarterly meetings were held during the first nine months, the CARs decided that more frequent bi-monthly meetings would be more effective in building the network, retaining and maintaining CARs, facilitating bi-directional communication between the university and community partners, and updating the community about the ongoing EFIC trial; therefore, the subsequent meetings were scheduled bi-monthly.

Training & Education

The community members asked to be in the study were selected because of their knowledge of the community. Because we were testing a new model of community consultation, we selected CARs who were educated in areas including social sciences, humanities, and health. Only one had prior human research experience. The university researchers conducted a series of educational sessions for the CARs, including: the history and current status of human subjects research protection, community roles in research from participant to community-based participatory research, and understanding seizures for lay people. The seizure training was conducted by a CAR who was a nurse and advocate with a seizure foundation. The background of EFIC research and requirements for CC/PD were also discussed.

DATA COLLECTION

Community Surveys

Baseline data were necessary for us to understand the level of community awareness about the ongoing EFIC trial. The first community survey was conducted immediately after enrolling the CARs, and a second survey was conducted eleven months later after the CARs had assisted with PD for the first trial and had conducted CC/PD for a second EFIC trial. These anonymous surveys of adults were developed in collaboration with the CARs to ensure language and cultural appropriateness. The CARs were trained regarding conduct of the surveys.

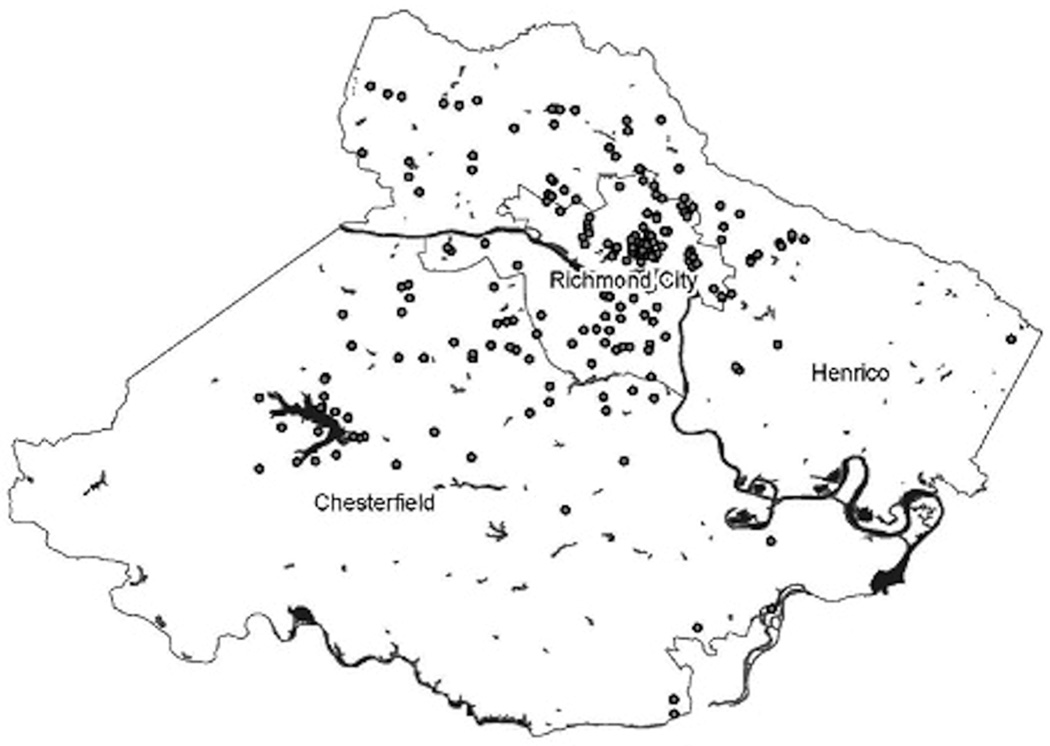

Following IRB approval of the surveys, the CARs distributed the surveys within their communities. CARs were allowed to define their own communities and the samples. Each CAR was asked to distribute and collect up to 50 surveys. Surveys included demographic questions and knowledge about the EFIC trial(s). The first survey also asked participants to report the closest street intersection to their home to allow mapping of respondents. These locations were then mapped using ArcGIS9.1.3 (see Figure 1). The figure shows the distribution and reach of survey respondents enrolled by the CARs.

FIGURE 1. GIS Mapping of Nearest Intersection to Participant’s Home.

The intersection closest to participants’ homes was recorded in the first survey. The first EFIC trial was conducted within city limits. The second EFIC trial targeted the city and surrounding counties. The figure shows the reach of CARs for the first study, and how their reach includes the surrounding counties. Participants are noted by dots; dots may represent more than one individual.

GIS = geographic information system; EFIC = exception from informed consent; CARs = community advocates for research

CC/PD Working Group

After receiving the training sessions described and using community-based participatory research methods, CARs were asked to develop a working definition and specific strategies for CC/PD and describe how it should be conducted. To assist this discussion, the researchers provided CARs with a list of key questions from the literature on CC/PD. Although, research staff was available to answer questions, the CARs were allowed to independently develop their own definitions and strategies. Results were presented to and agreed upon by the joint university research-CAR group.

CC/PD for Two Trials

Community consultation and IRB approval had occurred for the first EFIC trial approximately three months before the start of the CAR study. The CARs assisted with ongoing public disclosure for the first EFIC trial. For a second new EFIC trial that started during our study, the CARs screened the educational slide presentation and brochures to be used for the CC/PD for that trial. The CARs helped schedule, invite, and organize community consultation meetings within their communities. This allowed exploration of how CARs affect the CC/PD activities of both EFIC trials.

RESULTS

The 10 CARs include three women, one Hispanic, five African Americans, and four whites. To date, we have retained all ten of these CARs over the past fifteen months.

Community Surveys

The CARs conducted two surveys within their communities. The results for the two surveys are shown in Table 3. After the CARs conducted the outreach activities for the first trial, surveys showed a significant increase in the proportion of individuals having heard about the trial (8.4% of 390 in first survey and 21.5% of 325 in second survey, Z = 4.709; one-tail confidence level = 100%), and this higher proportion was similar for the second trial that used CARs (23.9% of 325).

Table 3.

Results of Community Surveys

| Survey 1 Fall 2009 | Survey 2 Fall 2010 | |

|---|---|---|

| Completed surveys | 390 | 325 |

| Ethnicity/race | 5.4% Hispanic, 43.1% black or African American, 46.7% white, 3% American Indian or Alaskan Native | 5% Hispanic, 56.5% black or African American, 33.6% white, 8.3% American Indian or Alaskan Native |

| Sex | 34.6% Male | 52.5% Male |

| Had heard about EFIC Trial 1 | 8.4% | 21.5% |

| Had heard about EFIC Trial 2 | N/A | 23.9% |

| Had heard about the Tuskegee | N/A | 46.1% |

| Syphilis Trial |

EFIC = exception from informed consent

During the first survey, survey respondents were asked to provide the intersections closest to their homes for mapping. The closest intersection point was chosen to avoid asking participants to report their addresses. The CARs reported that this question concerned survey respondents, who questioned why this information was needed. After discussion with the CARs, this question was omitted from the second survey. Figure 1 shows the map with the closest intersection point for the survey respondents. The first EFIC trial was conducted in the city limits that covers 62.5 square miles and has a resident population of 200,000, which grows to over a million during the work week. This map shows that although the CARs were initially selected for the first EFIC trial that was conducted only in the city limits, their communities included members in surrounding counties. CARs were allowed to define their communities, and told researchers that they had multiple communities with which they engage, including work, membership in organizations, and their neighborhoods. This led to the development of a community assessment tool that identifies the types, demographics, and communication methods for each CAR community. This proved to be critical information in planning the CC/PD for the second EFIC trial, because the target area was not only the city but also the surrounding counties. The survey also provided several other key pieces of information. As the initial activity for CARs, the survey prompted the discussion of community mistrust of the university, provided CARs hands-on experience with research practices, and provided an opportunity for researchers to discuss issues of scientific integrity, including data collection, storage, analysis, and human subjects protection. This activity was also the catalyst for the discussion regarding strategies for reporting our research results back to the community. It was decided that CARs would distribute a results brochure, including the map of intersection points.

Community Perspectives on CC/PD

The CARs were asked to identify the challenges that EFIC research poses for their communities. They reported that people in the community are nervous about researchers having the ability to conduct research on them without their consent. They also recognized that convening people to hear about a trial and provide input about that trial is difficult. The CARs reported that the key to successful community consultation is an open dialogue, and that due to the communities’ mistrust of the university, having a familiar face and trusted community member assist with the CC/PD plans would help reach the goals of CC/PD.

The CARs also reported the concern that some researchers may stereotype specific groups. For example, the CARs noted that some researchers believe that homeless individuals (a population at risk for being in the EFIC trial) have low intellect and are unable to engage in meaningful dialogue with researchers. CARs working with this population found this to be untrue. The homeless population actively listened to the community consultation and asked insightful questions. CARs suggested that ongoing university interaction with the community will help future community consultation efforts, and that the community will be more involved if the community feels respected, is taken seriously, and is heard. CARs noted that the researchers have the responsibility to provide as much education as possible, but they could assist by getting as many people as possible to as many meetings as possible in a timely manner.

The CARs were asked how to measure and track community consultation. They reported that if CC was successful, the CARs would hear people in their communities talking about the study and that community members would contact the CARs for more information. It is interesting to note that CARs thought that there is never enough public disclosure. CARs reported that public disclosure needed to be ongoing because the community changes over time and the community is inundated with information. Ongoing public disclosure would remind the community about the research and their potential role in the research. Finally, the CARs asked the researchers “How do you [the university] know when community consultation is working?” To date this has not been clearly answered.

The CARs reported that the best community consultation strategies are the same communication methods used for other information. This includes community meetings, phone calls, conference calls, phone trees (electronic messages), websites, e-mail, mail, newspapers, reader boards, and flyers. However, the content for the community consultation needs to be broad, not only including why the trial is being conducted, what it involves, and the risks, but also other key points. First, informed consent must be clearly explained, and what exception from this consent means and when it can be used must be discussed. Second, individuals should be informed that they do not have to participate, and that they can refuse to be in any study. For EFIC research, the community should have an easily accessible mechanism of informing researchers that they do not want to participate. Third, individuals should be told how their rights and safety are being protected. Finally, not only for EFIC research, but for other studies as well, research results should be reported back to the community in terms that they can understand.

Participation in CC/PD

The first EFIC trial had begun prior to the recruitment of the CARs. Therefore, CARs were not involved in the community consultation. They did assist with later ongoing public disclosure by hosting several meetings. For the second EFIC trial that started during our study, the PI presented educational slides for community consultation to the CARs. The CARs provided suggestions for improving the format, content, and language of the materials to improve understandability. The CARs decided to engage with the second EFIC trial for CC/PD. The CARs learned about the trial and then opened the dialogue with their communities, but it was understood that specific clinical information about the trial had to come from the researchers. The CARs also discussed that the role of the CAR was to be a conduit for information, rather than an advocate or recruiter for the study. The CARs assisted with planning, and inviting community members to meetings, either specifically to hear about the trial, or as an addition to a pre-arranged meeting. Table 4 shows differences between the community consultation for trials 1 and 2.

Table 4.

Comparing Two EFIC trials

|

EFIC Trial |

Time from IRB approval of the CC/PD plan to completion |

Researcher man-hours required to organize, advertise, and conduct CC/PD meetings |

|---|---|---|

| Trial 1 | 8 months | 1,000 |

| Trial 2 | 2 months | 120 |

Feedback from the university researcher for the second EIC trial summarizes the benefits of this model:

“I gave the {study} flyer to the person organizing the meeting and they posted it or sent it via e-mail as part on an invitation. I would say the most time-consuming aspect of these consultations and events was making the arrangements – the numerous phone calls back and forth to set things up. This was particularly labor-intensive for groups I contacted directly and wasn’t nearly as bad when dealing with the CARS since you introduced me to them at the meeting ….and they knew what I wanted to talk about. So the existence of the CARS made my job easier at finding groups in the community to describe the {study} trial to. Thanks to your organization of CARS, the community consultation aspect for EFIC in the trial was accomplished in only a couple months.”

DISCUSSION

Community-based participatory research strategies have been used throughout the study for researchers and community members to jointly define roles, responsibilities, needs, and directions for the CARs. These CARs have now participated in ongoing public disclosure for the initial EFIC trial and have now also been involved in enhancing initial CC/PD for a new second EFIC trial. This second study has been able to utilize the original CARs by recognizing that individuals represent multiple communities including neighborhoods, work places, and activities. Investigators need to identify the target groups and communities for their study to determine targets for the community consultation9 and work with those groups. The CARs were able to identify relevant groups and determine appropriate strategies to reach into the communities once the focus of the second study was explained to them.

Specific strategies used by CARs to reach into their communities included: group meetings (both study-specific town halls and ongoing community groups that meet regularly), individual information transfer incorporated into daily interaction, community newsletter and newspaper articles, church notices, and distribution of flyers and study brochures. While these strategies appear to be similar to previous community consultation activities, there are key differences. The CAR strategies are ongoing interconnected activities rather than isolated events, and they represent a wide variety of individuals and communities within a geographic region. These strategies provide mechanisms to distribute information that is consistent across communities, but may be tailored in delivery method or focus within specific communities. CARs decreased the research staff time required to post flyers, hold meetings, and distribute brochures. The first study (without CARs) took an estimated 1,000 man-hours for conducting community consultation; however, the second study employing CARs took only 120 research staff man-hours to accomplish community consultation. Perhaps most importantly, CARs provide an “insider’s” introduction to the community, which increases participation and trust. Therefore, to date, the CARs approach has been found to be feasible and acceptable to researchers and the communities with which we worked.

Community consultation for research can also occur in non-EFIC studies, where community input is sought before a study is conducted. Dickert and Sugarman suggested four ethical goals of community consultation that would apply for this research.13 The first is enhanced protection: community consultation may identify risks or hazards that were not previously considered and may offer potential protections to mitigate these risks. It offers enhanced benefits that may include improvement of infrastructure, delivery of services, or recognition of community-based research questions. Community consultation provides legitimacy by giving communities with an interest or a stake in the research (e.g., communities where the trial will occur) an opportunity to express their views and concerns at a time when changes could be made to the protocol or the protocol even canceled due to significant community concerns. Finally, it provides shared responsibility where the community may bear some degree of moral responsibility for the research, and in some instances may take on some responsibilities for conducting the study. They propose these goals as markers to guide the researchers in designing their plans and in identifying their strategies for community consultation. 13 CARs can provide opportunities for this bidirectional communication for both EFIC research as well as other types of research.

Putting it all together: blending ethical goals, community-based participatory research strategies, and CC/PD

The ethical goals of community consultation correlate well with strategies of community-based participatory research,14 and effectively achieve the goals of community consultation. Table 5 shows the links between these ethical goals and community-based participatory research principles within the CARs model.

Table 5.

Community Consultation Goals and Community-Based Participatory Research

| CC Ethical Goal13 | Definition | CBPR strategy14 | CAR Project Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enhanced protection |

Identifying risks for individuals & communities not previously known & suggesting potential protections |

Integrated sources of knowledge |

Each CAR represents unique populations & concerns relevant to current EFIC study |

| Enhanced benefit | Identifying enhanced benefits to participants, population & community |

Achievement of common goals |

Ongoing education to CARs which facilitate dissemination into their target communities Community concerns are quickly addressed, education is formatted & disseminated in community context |

| Legitimacy | Giving parties with an interest in the research opportunity to express concerns when changes can be made |

Active engagement and shared decision- making Integrated sources of knowledge Multiple channels of dissemination |

Communications are designed by CARs for their communities CARs “hosted” community consultation events within their communities Flyers and brochures distributed directly within communities |

| Shared responsibility |

Consulted communities may share some moral responsibility and take on some aspects of research |

Active engagement and shared decision- making Iterative data collection & analysis |

Bi-directional communications about the study are on ongoing Attendance at meetings is increased which engages community members to actively think about the research study and its impact |

CC = community consultation; CBPR = community-based participatory research; CAR = community advocates for research; EFIC = exception from informed consent

LIMITATIONS

This is a preliminary study of a new model to engage community members as CARs. We have looked at this model for CC/PD activities specifically for EFIC studies, and therefore, it may not be generalizable to other types of research. Evaluation of the CAR model with other community-based research in order to note utility, benefits, and drawbacks needs to be conducted. There is no defined method for determining the effectiveness of CC/PD. We have shown increased awareness about the EFIC study in the community using the CAR model, but true reach and understanding are harder to measure. Process evaluation for this model is still underway, and although we could show a shorter time to complete community consultation and fewer man-hours required, other influences were also present. These included an IRB that had recently gone through the process of approving a previous EFIC trial, and the development of a formal university IRB policy for the steps to approval of this type of research.

It takes time to recruit, train, and coordinate a CAR network. Having a network pre-established, as was possible for the second trial, allows quick activation of the network. Therefore, establishing and maintaining a CAR model and using the model network for EFIC and other types of research will allow the community members to be ready when an EFIC trial is being considered.

EFIC trials tend to take place in academic health centers, many of which are part of the Clinical Translational Science Award (CTSA) program of the NIH. While emergency medicine researchers are likely not experts in community engagement or strategies for community-based participatory research, if CTSAs, their universities likely already have community engagement and research programs that can inform the CC/PD strategies. Even if not a CTSA, most universities have key individuals or units within their institutions that have ongoing programs connecting to the community, such as an Office of Community Engagement, Service-Learning Office, or Community Outreach Unit of the hospital. The individuals in these areas can provide valuable guidance and insight regarding how to partner with communities in developing, evaluating, and accomplishing effective CC/PD.

CONCLUSIONS

To date, compared to the traditional community consultation plan used before, the community advocates for research have: 1) provided community specific information on best ways to engage the community in dialogue; 2) increased the number of individuals reporting knowledge about the trials; 3) remained active; 4) provided a feasible method to reach community members; and 5) at least preliminarily, shown that an established Community Advocates for Research network is a cost-effective and time-efficient method for genuine community consultation. Early results also demonstrate that this model using community participatory principles aligns closely with community consultation ethical goals.

Investigators and IRBs need to know the specific target community that could be effected by the exception from informed consent trial and ask what community consultation strategies will work for a specific study.4 The community assessment tool developed in this study will assist with tracking communities represented by the community advocates for research and allow future studies to engage community advocates for research with specific community characteristics.

By merging community-based participatory research strategies with the goals of community consultation and public disclosure, the scope and reach of communication and information flow can be increased. The scope of community consultation means reaching more specific communities more effectively, and reach means the partnership truly exchanges information in specific communities that have been historically difficult to reach, allowing community members to understand the study, and researchers to gain a better understanding of the concerns of that community. Additionally, and perhaps more significantly, we are building capacity for future research partnerships both within our university and our community.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the Community Advocates for Research and our research staff for their contributions and hard work.

Funding Sources: The project was supported by grant 5RC1NR011536-02 from the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIH. Additional resources were provided by NIH 1UL1RR037990-1.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations: Outreach Scholarship Conference, Raleigh, North Carolina, October 2010; International Conference on Urban Health, New York, New York, October 2010

Disclosures: The authors have no disclosures or conflicts of interest to report

REFERENCES

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services Code of Federal Regulation, Protection of Human Subjects: informed consent and waiver of informed consent requirements in certain emergency research: final rules 21 CFR Part 50.24 and 45 CFR Part 46.101. Fed Reg. 1996;61:51497–51533. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biros MH. Research without consent: exception from and waiver of informed consent in resuscitation research. Sci Eng Ethics. 2007;13:361–369. doi: 10.1007/s11948-007-9020-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biros M. Research without consent: current status, 2003. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42:550–564. doi: 10.1067/s0196-0644(03)00490-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ernst A, Fish S. Exception from informed consent: viewpoint of institutional review boards–balancing risks to subjects, community consultation, and future directions. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:1050–1055. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morris M. An ethical analysis of exception from informed consent regulations. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:1113–1119. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.03.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah A, Sugarman J. Protecting research subjects under the waiver of informed consent for emergency research: experiences with efforts to inform the community. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:72–78. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kremers MS, Whisnant DR, Lowder LS, Gregg L. Initial experience using the food and drug administration guidelines for emergency research without consent. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33:224–229. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(99)70399-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bulger E, Schmidt T, Cook A, et al. The random dialing survey as a tool for community consultation for research involving the emergency medicine exception from informed consent. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:341–350. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biros MH, Fish SS, Lewis RJ. Implementing the food and drug administration’s final rule for waiver of informed consent in certain emergency research circumstances. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:1272–1282. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nelson M, Schmidt T, DeIorio N, McConnell KJ, Griffiths D, McClure K. Community consultation methods in a study using exception to informed consent. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2008;12:417–425. doi: 10.1080/10903120802290885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baren J, Biros M. The research on community consultation: an annotated bibliography. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:346–352. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt T, Delorio N, McClure K. The meaning of community consultation. Am J Bioethics. 2006;6:30–32. doi: 10.1080/15265160600685804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dickert N, Sugarman J. Ethical goals of community consultation in research. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1123–1127. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.058933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shore N, Wong KA, Seifer SD, Grignon J, Gamble V. Introduction to Special Issue: Advancing the Ethics of Community-Based Participatory Research. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2008;3(2):1–4. doi: 10.1525/jer.2008.3.2.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]