Abstract

Aim

It has been previously shown that community refinement of glaucoma referrals is an efficient way to investigate and treat glaucoma suspects. The potential for false negatives has not been explored previously and we describe a scheme in which effort has been made to both assess and control for this, and report on its success.

Methods

Trained optometrists were recruited to examine and investigate the patients referred with suspected glaucoma, with a view to decreasing false-positive rates in accordance with an agreed protocol. The randomly selected notes of 100 patients referred onward to the Hospital Eye Service (HES) by trained, accredited optometrists, and the notes and optic disc images of 100 randomly selected patients retained in the community were examined in order to determine the efficiency and safety of the scheme.

Results

The scheme resulted in a 53% reduction in the total number of referrals to HES with a cost saving of £117 per patient. Analysis of patients referred resulted in a diagnosis of glaucoma or retention of patients in HES with suspected glaucoma in 83% and a good correlation between the hospital and optometric measurements. Analysis of notes and optic nerve images of patients not referred indicated no compromise on patient safety.

Conclusion

This study suggests that suspected glaucoma can be successfully refined in the community with benefits to both the patient and the hospital. We also suggest that such a scheme may be safe as well as cost-effective, a conclusion that has not as yet been reached by any other study.

Keywords: referral refinement, glaucoma, optometry

Introduction

The primary care optometrist is an important source of referrals to the Hospital Eye Service (HES) of suspected cases of primary open angle glaucoma (POAG), accounting for more than 90% of all referrals.1, 2 This common condition is insidious and diagnosis in the asymptomatic stage is vital if the patient has to benefit from early treatment.3 A large percentage of new referrals to HES and an even greater percentage of follow-up visits are cases of suspected glaucoma, but a significant number, around 36–60%, of these referrals do not result in a diagnosis of glaucoma.2, 4, 5

The proportion of false positives among referred patients is linked with the number and quality of various assessments performed by the referring optometrist, including optic disc analysis and visual fields.4 Efforts to increase the quality of referrals have included the provision of guidelines to local optometrists, but examination of the referrals made this way showed poor adherence to the guidelines, and that such guidelines did not significantly decrease the proportion of false-positive referrals.6 The National Eye Care Service Steering Group has recommended new referral pathways, which include assessment of suspected glaucoma patients by specially trained optometrists with an interest in glaucoma.7

The burden of processing false-positive cases of glaucoma by HES results in increasing waiting times for new and follow-up appointments and has financial implications both for the hospital and for the patient. When considering that up to 50% of glaucoma is undiagnosed in industrialised countries, the potential burden of properly assessing all glaucoma suspects becomes even more challenging.8, 9 Community refinement of glaucoma referrals by trained optometrists was trialled in Manchester and resulted in a 40% reduction in referrals to the Manchester Royal Eye Hospital, as well as a cost saving to the NHS.10 In this scheme, the patients were filtered through a system of trained optometrists and either referred onward to the HES or returned to the optometrist or GP that had initiated the referral. False-negative rates were not examined by the team involved, although audit of the system did reveal significant reductions in false-positive rates.

We report a variation in the Manchester scheme applied to the patient population of Carmarthenshire, the Carmarthenshire Glaucoma Referral Refinement Scheme (CGRS), in which patients deemed not to warrant onward referral to HES were reviewed by a smaller group of trained optometrists with optic disc imaging facilities after 12 months as a form of additional refinement, and were either referred at that stage or discharged back to the source of referral. The results of the first 4 years of the CGRS are presented herein to include an audit of 100 cases referred to HES from the CGRS. We also examine 100 cases of those patients who, following reassessment (negative refinement), were deemed not in need of onward HES referral.

Materials and methods

Optometrists based in Carmarthenshire submitting sight-test claims were invited by post to apply for the CGRS. Interested parties completed the Welsh Eye Care Initiative modular accreditation followed by further training via formal lecture, direct-patient examination, and feedback with emphasis on disc assessment. This training was undertaken by a group of consultant ophthalmologists and other senior eye specialists. In all, 17 optometrists qualified for inclusion and a further 2 were added during the course of the scheme.

Accredited optometrists were trained to use contact applanation tonometry (Perkins Hand Held or Goldman slit lamp mounted), indirect ophthalmoscopy (78D), and perform a suprathreshold visual-field test with one of the following instruments: Dicon 400 (Eyetech Optical Ltd, Slough, UK), Henson Bowl Perimeter (Buchmann UK Ltd, Kent, UK), Humphrey Visual-Field Analyzer (600 or 700 series; Carl Zeiss Ltd, Welwyn Garden City, UK), on all patients referred through the scheme. Assessment as part of the CGRS included, in chronological order:

Best-corrected visual acuity

Suprathreshold visual-field test with Humphrey, Henson, or equivalent machine

Anterior-chamber depth measurement by Van Herrick's or Redmond Smith method, along with any abnormalities of the anterior segment noted

Intraocular pressure (IOP) measurement by either Perkins or Goldmann tonometry

Dilated disc assessment, with special consideration being given to disc size, vertical cup disc ratio (CDR), cup type, observation on ISNT rule being broken or not, and any focal abnormalities of the disc or surrounding region.

Following assessment in this manner, the patient was then referred to the HES if certain criteria were fulfilled. The ‘all-Wales' criteria were utilised as follows:

Single referral criteria

IOP of ≥26 mm Hg on two occasions

Visual-field defect on two occasions

Pathological disc cupping or asymmetry of ≥0.2.

Combined referral criteria

IOP >22 and visual-field defect

Suspect optic disc defect and visual-field defect

IOP >22 and suspect optic discs.

Additional referral criteria

Optic disc change or haemorrhage

Signs of secondary glaucoma

Pigment dispersion

Pseudoexfoliation and uveitis

Rubeosis

Angle closure (if history suggests immediate referral is recommended).

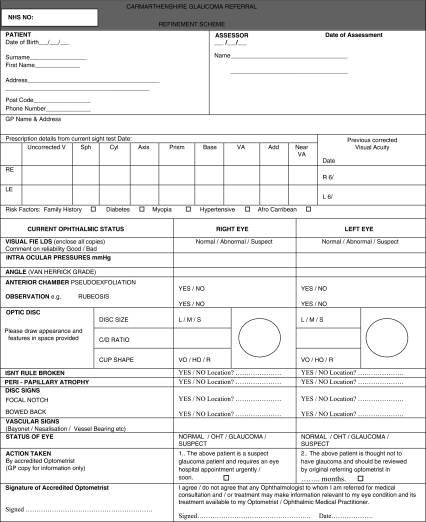

This information was incorporated onto a special form (Figure 1), and if the above criteria were met onward referral to HES was initiated. If the criteria were not met, the patients were reanalysed at 12 months by a smaller group of trained optometrists whose practices had disc-imaging facilities, and reassessed. If patients were again ineligible for onward referral, they would be referred back to the originating source. A monoscopic image of the optic disc along with a copy of the completed form was forwarded to the HES in 100 cases for further examination as part of the study.

Figure 1.

An example of the proforma sheet used in the Carmarthenshire Glaucoma Refinement Scheme (CGRS).

Both branches of the scheme were audited, the patients who had been referred to HES and those who had been discharged under the scheme, via the information sheet and optic disc photograph. A total of 100 patients in each group were analysed and evaluated in terms of their adherence to the scheme protocols and in terms of their predictive vale. In addition, a blind analysis of all 100 optic disc images was undertaken by three consultant ophthalmologists and the results compared with those obtained by the referring optometrist.

Results

Of a total of 1736 patients who passed through the CGRS in the first 4 years of its operation, 811 were referred onward to HES and 925 discharged back to the care of the primary care optometrist and/or GP, having been reviewed at 12 months. A total of 100 patients in each group were analysed in order to compare the findings between HES and the referring CGRS optometrists. Table 1 shows a comparison between the hospital's and referrer's diagnoses. It can be seen here that of all referrals to HES from the CGRS, 83% were either diagnosed immediately with glaucoma or retained in the clinic for follow-up investigation. Of the 14 ‘normals', only 5 were immediately discharged, indicating that the remaining 9 patients were suspicious enough to warrant further attention.

Table 1. An overview of diagnostic agreement between HES and referring optometrist.

| Diagnosis | Referred assessment (%) | Hospital assessment (%) |

|---|---|---|

| POAG | 25 | 22 (9 NTG) |

| OHT | 14 | 16 |

| Suspect | 59 | 45 |

| DNA | 1 | |

| Other | 2 | 2 (Cataract) |

| Normal | 0 | 14 |

Table 2 compares the agreement between HES and CGRS optometrists with regard to IOP, which can be seen as a close agreement. Visual-field abnormalities were diagnosed in 51% of the referred cases, compared with 43% in the HES group. Table 3 shows the equivalent figures for CDR, which displayed the least agreement. As can be seen, referring optometrists tended to overestimate the CDR when compared with HES.

Table 2. A comparison of IOP values between referring CGRS optometrists and HES.

| IOP | Referred (%) | Hospital (%) |

|---|---|---|

| <22 | 52 | 57 |

| 22–30 | 38 | 36 |

| >30 | 10 | 5 |

| Not assessed | 2 (1 DNA) |

Table 3. A comparison of cup:disc ratio values between referring CGRS optometrists and HES.

| CDR | Referred (%) | Hospital (%) |

|---|---|---|

| <0.3 | 7 | 14 |

| 0.3–0.5 | 28 | 30 |

| >0.5 | 65 | 52 |

| 4 not documented |

Of those patients not referred to HES, totalling 925, 100 had optic disc photographs sent to the hospital along with completed refinement scheme forms. A total of 100 such forms, of patients not referred, were analysed by the authors and all were found to have followed the agreed protocols. The optic disc photographs were also shown to three hospital consultants, devoid of any accompanying information, and they were asked to grade the quality of the image (acceptable or unacceptable for diagnostic purposes). They were also asked to note whether the discs appeared normal, suspicious, or obviously pathological. These three opinions were averaged and compared with those of the referring optometrist. In all, 98% of the images were deemed acceptable and 2% were of insufficient quality for proper assessment. Of the 98 acceptable images, consultant ophthalmologists were in agreement with the referring optometrist 50% of the time, suggested overestimation of CDR 35% of the time, with the remaining 15% of images displaying underestimation. Of these 15 patients, 2 showed changes that merited recall to the HES for further investigation. Neither of these was started on ocular antihypertensives. This translates as a false-negative rate of between 3 and 10%.

Discussion

Screening for glaucoma is made much more difficult as there is no single ‘simple, safe, precise and validated screening test' available as defined by the 1998 UK National Screening Committee. Using this definition, most screening programmes fall short of the standards required.11 Moreover, opinions vary as to what the current gold standard is for the diagnosis of glaucoma. One of the most widely accepted methods to detect and assess glaucoma is to perform a comprehensive eye examination for all patients who attend the clinic irrespective of the complaints they present with.12 The Royal College of Ophthalmologists have acknowledged the difficulties of applying gold standard screening principles for the detection of glaucoma and asserted that ‘any formal screening programme will not identify every subtle glaucoma at a stage at which a glaucoma specialist might identify the disorder'.7 Despite this, efforts must be made to adhere as closely as possible to these principles, and we believe the CGRS fulfils these recommendations.

Having run successfully for 4 years, the CGRS has resulted in numerous benefits for all concerned. The benefits for the patients include faster assessment and a single appointment during which all necessary investigations are performed, which is not usually the case in the HES. To the optometrist the scheme provides clear guidelines for the referral of suspected cases of glaucoma to HES, as well as the added bonus of increased training for the interested parties in using a 78-D lens and analysing optic discs. Equally importantly, the benefit to HES is a 53% decrease in the absolute number of patients referred with suspected glaucoma with a not inconsiderable cost saving per patient. The financial analysis of the scheme is summarized in Table 4. These figures are based on a current cost of £210 per outpatient seen in the clinic as a new referral and £65 for a follow-up visit. Another assumption is that an average of 2.3 clinic visits are made before a decision to discharge a patient referred with suspected glaucoma is arrived at. Using these parameters it is calculated that there is an overall saving of £117 per patient passing through the CGRS.

Table 4. Financial analysis of the CGRS.

| Savings | Costs | Explanation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training and audit | 3708 | ||

| Optometrists fees | 65 952 | £38 per patient | |

| Admin | Minimal | ||

| Handling of claims | Minimal | ||

| HES non-referred cases | 273 800 | 925 × 2.3 visits* | |

| Total | 273 800 | 69 660 |

An average of 2.3 clinic visits is made before a decision to discharge a glaucoma patient is arrived at.

These factors would be expected to result in decreased waiting times for other new and follow-up patients, although these figures were not formally analysed.

In screening, to avoid missing cases requires a highly sensitive test (or tests). However, when the cut-off value is set to maximize sensitivity, the trade-off is a loss of specificity. In this situation, diagnostic facilities are in danger of being swamped by patients labelled as having a positive result on a screening test who do not have the condition of interest. Each of the individual tests within the screening methods used in this refinement has well-established sensitivity and specificity values. However, the aim of the refinement scheme is not necessarily to accurately diagnose glaucoma, but to include glaucoma suspects, to ensure that the disease is not missed and to improve quality of referral. Only 25% of referrals sent onward to HES were sent through as purported ‘glaucoma'. Of all, 75% of referrals were for ‘suspect' glaucoma. There is no gold standard for suspect glaucoma, merely an index of suspicion that merits further investigation when assessed by an experienced ophthalmologist. Retention in the clinic implies a shared index of suspicion and therefore, for our purposes, retention in the clinic is an appropriate, if crude, way of assessing accuracy in this pilot, both for glaucoma and for suspect glaucoma. Retention analysis of the results concludes a sensitivity to correctly assess as glaucoma or suspect or OHT of 95.3% and a specificity of 87.3%. The positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were noted as 85.6% and 96.0%, respectively. Of the 14 false positives identified by HES, as discussed, 9 were retained for further testing. If these are included in the analysis, the specificity rises to 95.0% and the PPV to 95.8%. In this case ‘false positives' are defined as those cases sent onward by the scheme for HES assessment that were not defined as suffering from glaucoma or OHT, and ‘false negatives' are those cases retained in the community without a diagnosis of glaucoma that would have been best served by being directed towards HES as they had features of either glaucoma or OHT.

The PPV and NPV indicate that our scheme is extremely safe. In comparison with the Manchester scheme,10 we have altered the referral pathway in an attempt to quantify and decrease the number of false-negative results, with the principle of a second visit at 12 months providing an important safety net. Examination of 100 optic nerve head images did indicate that although some were of a quality unsuitable for accurate diagnosis, the vast majority (98%) was acceptable. Further analysis by consultant ophthalmic surgeons indicated a tendency for optometrists allied to the scheme to overestimate rather than underestimate CDR (35% vs 15%), thus indicating a healthy bias towards cautionary assessment of optic nerve head images. It must be mentioned at this stage that stereoscopic photographs for the assessment of glaucoma have been shown to have less inter-observer variation than monoscopic images, although the difference was not large.13 In particular, the smaller the CDR, the greater the tendency to overestimate. This does, however, indicate room for improvement in the training of optometrists to interpret optic nerve head images.

Obviously, the greatest difference between the CGRS and the Manchester scheme is the fact that in our scheme there is a second follow-up appointment a year after the first if referral is not deemed necessary. It is worth considering at this stage the alternative schemes that exist elsewhere in the country. The West Kent scheme encourages all optometrists contemplating a referral to adhere to certain guidelines, which, if special tests are completed, results in a payment of £10. An interesting variant, run in Bradford, involves a shared-care approach in which glaucoma and ocular hypertension are initially assessed by HES and all subsequent follow-up visits are undertaken by community optometrists who have completed a 1-day accreditation course. If the condition of the patient becomes unstable at any follow-up visit, a re-referral to HES is then initiated. Variants of this shared-care approach are demonstrated by schemes set up in Hull and Peterborough, but interestingly it was in Bristol that an effort was made to compare hospital and optometric follow-up of these patients by running the new and the old schemes at the same time.14 Our scheme therefore, along with the Manchester and West–Kent scheme, is the most closely related, with ours providing arguably the most developed model for safeguarding patient safety and being the only such scheme in which the proforma contains an optic disc outline for accurate ratio recording.

Further increasing safety though is always desirable, and a logical extension to this scheme would be to extend optic nerve head imaging and analysis by HES to all patients categorized as unsuitable for formal referral to the hospital. There are, however, several drawbacks with this plan. First, the cost of making optic nerve head imaging facilities more widespread would either be prohibitive and result in a diminishing saving on financial gain analysis, or result in some trained optometrists being excluded from the CGRS. There is no doubt, however, that the cost of this specialist equipment is being driven downwards and what currently may be considered an expensive diagnostic luxury may be more widely available, and more cheaply, in a relatively short space of time. A second consideration is that HES personnel would need to routinely analyse the forms and pictures generated via this amendment to the scheme as a virtual clinic, which in itself diminishes the time and cost savings accrued by HES in not assessing these patients in outpatient clinics, but would allow for quality assurance issues to be addressed.

In answer to these concerns, it may be possible to further filter those patients categorised as unnecessary referrals to HES by analysing the optic disc for further features that are likely to represent glaucomatous damage.15 Analysis could include factors such as race, CDR of >0.65 associated with asymmetry of >0.2, as well as other typical features in order to produce a reduced pool of patients requiring disc photography for virtual review. We would expect these measures to reduce the false-negative rate yet further, although stereoscopic disc photographs may prove to be a further advancement in accurately assessing cupping in a ‘virtual clinic' setting.13

An examination of a proportion of those patients sent onward by the CGRS to HES showed significant agreement between the two sets of IOP readings, although again CDR tended to be overestimated by the referring optometrist. The mild discrepancy between detection of visual-field abnormalities (43% by optometrists vs 51% by the HES) may be due to a lack of uniformity in visual-field analysis instruments between assessors. Although the Humphrey Central 30-2 SITA is accepted as the gold standard in visual field analysis, many optometric practices did not have this mode of examination and it is possible that standardizing field analysis in this way may lead to even greater correlation between optometric and HES analysis of the visual field. There is, however, likely to be a significant cost drawback in standardising field analysis in this way.

As detailed in the Manchester study,10 it is possible that the timely and efficient analysis of suspected glaucoma cases by the CGRS may result in an increased number of referrals to the scheme by optometrists who feel that they no longer need to do so many of their own investigations before deciding whether to refer. Indeed, if this proves to be correct, the overall cost of the scheme would increase and again threaten the financial stability of the project. The benefit of reduced waiting times for seeing new and follow-up patients would, however, still be maintained in this eventuality.

Conclusion

The CGRS has reduced the number of patients attending HES for suspected glaucoma by 53%. There are associated benefits for both the hospital and the patient for reduced referral rates of patients with suspected glaucoma, including reduced waiting times for new and follow-up appointments, as well as a significant cost saving of £117 per patient. Our scheme was also the first to look at false-negative rates, which were found to be between 3 and 10%. Our scheme was based on the Manchester glaucoma refinement scheme,10 with the added precautionary measure of a repeat visit to the accredited optometrists in the refinement scheme at 12 months for those patients not referred onto HES. An analysis of a portion of those patients referred and the completed proforma and optic disc images of those retained in the community confirmed a very similar analysis of patient variables between the trained optometrists and HES personnel. We believe that our study of 100 subjects suggests the benefits of a glaucoma refinement scheme and has indicated that such a scheme may be safe, but acknowledge that a larger sample size would have demonstrated this conclusion with greater certainty. Although further analysis of similar projects would undoubtedly provide more powerful information with regard to longer-term results, the model provided here is a variant that could be used to set up schemes elsewhere that have the added benefit of a safety net to catch potential false-negative glaucoma suspects. With the added burden that is already being shouldered by the HES in light of recent published NICE guidelines, such schemes may have an increasingly important role in glaucoma screening and management.16

We believe that our study is the first to demonstrate that a refinement scheme in which patients with suspected glaucoma are referred to HES by primary care optometrists and further assessed by trained, accredited optometrists is a simple, safe and efficient way of referring glaucoma suspects, where those patients who are not referred are not placed at significant clinical risk.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Harrison RJ, Wild JM, Hobley AJ. Referral patterns to an ophthalmic outpatient clinic by general practitioners and ophthalmic opticians and the role of these professionals in screening for ocular disease. BMJ. 1988;297:1162–1167. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6657.1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RD, O'Brien C. Accuracy of referral to a glaucoma clinic. Ophthal Physiol Opt. 1997;17:7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative Normal Tension Glaucoma Study Group Comparison of glaucomatous progression between untreated patients with normal tension glaucoma and patients with therapeutically reduced intraocular pressures. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;126:487–497. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(98)00223-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuck MW, Crick RP. Efficiency of referral for suspected glaucoma. BMJ. 1991;302:998–1000. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6783.998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RD, O-Brien C. The diagnostic outcome of new glaucoma referrals. Ophthal Physiol Opt. 1997;17:3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernon SA, Ghosh G. Do locally agreed guidelines for optometrists concerning the referral of glaucoma suspects influence referral practice. Eye. 2001;15:458–463. doi: 10.1038/eye.2001.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Eye Care Service Steering Group 2004 . http://www.vision2020uk.org.uk/core_files/220404eyecare%20report.doc .

- Coffey M, Reidy A, Wormald R, Xian WX, Wright L, Courtney P. Prevalence of glaucoma in the west of Ireland. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77:17–21. doi: 10.1136/bjo.77.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell P, Smith W, Attebo K, Healey PR. Prevalence of open angle glaucoma in Australia – The Blue Mountains eye study. Ophthalmology. 1996;103:1661–1669. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(96)30449-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henson DB, Spencer AF, Harper R, Cadman EJ. Community refinement of glaucoma referrals. Eye. 2003;17:21–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez A, Rabindranath K, Fraser C, Vale L, Blanco AA, Burr JM. Screening for open angle glaucoma: a systematic review of cost-effectiveness studies. J Glaucoma. 2008;17:159–168. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31814b9693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas R, Parikh R, Paul P, Muliyil J. Population based screening versus case detection. Ind J Ophthalmol. 2002;50:233–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan JE, Sheen NJ, North RV, Choong Y, Ansari E. Digital imaging of the optic nerve head: monoscopic and stereoscopic analysis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:879–884. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.046169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer IC, Spry PG, Gray SF, Baker IA, Menage MJ, Easty DL, et al. The Bristol shared care glaucoma study: study design. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1995;15:391–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster PJ, Burhmann R, Quigley HA, Johnson GJ. The definition and classification of glaucoma in prevalence surveys. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:238–242. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.2.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nice Guidelines . http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG85FullGuideline.pdf .