Abstract

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) has a 3000 years' history of human use. A literature survey addressing traditional evidence from human studies was done, with key result that top 10 TCM herb ingredients including Poria cocos, Radix polygalae, Radix glycyrrhizae, Radix angelica sinensis, and Radix rehmanniae were prioritized for highest potential benefit to dementia intervention, related to the highest frequency of use in 236 formulae collected from 29 ancient Pharmacopoeias, ancient formula books, or historical archives on ancient renowned TCM doctors, over the past 10 centuries. Based on the history of use, there was strong clinical support that Radix polygalae is memory improving. Pharmacological investigation also indicated that all the five ingredients mentioned above can elicit memory-improving effects in vivo and in vitro via multiple mechanisms of action, covering estrogen-like, cholinergic, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antiapoptotic, neurogenetic, and anti-Aβ activities. Furthermore, 11 active principles were identified, including sinapic acid, tenuifolin, isoliquiritigenin, liquiritigenin, glabridin, ferulic acid, Z-ligustilide, N-methyl-beta-carboline-3-carboxamide, coniferyl ferulate and 11-angeloylsenkyunolide F, and catalpol. It can be concluded that TCM has a potential for complementary and alternative role in treating senile dementia. The scientific evidence is being continuously mined to back up the traditional medical wisdom.

1. Introduction

Cognitive impairment or dementia in elderly is associated with many disorders [1]. Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the principal type of dementia and represents about 70% of the dementia patients.

The pathologic hallmarks of AD are senile plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, dystrophic neurites, and neuronal loss. The development of AD may be due to the improper biochemical processing of amyloid precursor protein (APP) leading to subsequent accumulation of β-amyloid (Aβ). The amyloid and tangle cascade hypothesis is the dominant explanation for the pathogenesis of AD [2]. Other relevant factors, including cholinergic dysfunction [3], neuroinflammation [4, 5], oxidative stress [6], and disturbance of neuronal plasticity [7], age-related loss of sex hormones [8, 9], are important and contribute to the understanding of AD pathology.

The 2nd most common form of dementia is vascular dementia (VD) or multi-infarct dementia, which accounts for about 15% of dementia cases [10, 11]. VD may follow after a succession of acute cerebrovascular events or, less commonly, a single major stroke. The compromised cerebrovascular circulation causes ischemia that leads to damage of the brain structure, for example, formation of white matter lesions or silent brain infarctions. VD is often related to the loss of fine motor control besides memory impairment.

Currently, there is no effective treatment for AD, although many treatment strategies exist [12]. Clinically, cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists are first-line pharmacotherapy for mild-to-moderate AD, with high nonresponse rate 50–75% [13].

Lots of folk plants in traditional medicine are being used in age-related brain disorders for improvement of memory and cognitive function [14–16]. In China, a number of herb ingredients known from Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) have a long history of use for mental health. In this study, we exploited the empirically driven TCM lore and surveyed scientific data to back up the cognitive benefits, claimed by TCM.

2. Ancient Records on TCM for Cognitive Decline

The term “senile dementia” refers to a clinical syndrome seen in the elderly characterized by impairment of memory and cognition. So in a search of the ancient literature of TCM, the etiology, pathogenesis, and treatment for “dementia or amnesia” have been used for the survey in detail.

2.1. Etiology and Pathogenesis

2.1.1. Deficiency of Energy

Deficiency of energy is similar to “Qi” deficiency in TCM. According TCM lore Qi is the essential substance that makes up the body and maintains various physiological activities, similar to flow of energy in the body. The energy is mainly from the kidney, heart, and spleen, especially from the kidney. In TCM, the energy from the kidney is called kidney essence which can produce marrow including cerebral marrow, spinal cord, and bone marrow. The cerebral marrow can nourish the brain and maintain the physiological functions of the brain. If the kidney essence is insufficient, the production of cerebral marrow will be reduced, leading to various symptoms, such as headache, dizziness, amnesia, and retard response [17].

2.1.2. Blood Stasis

Normally the blood is pumped by the heart to flow in the vessels. If blood circulation is stagnated or slowed down by certain factors such as cold, emotional disorder, aging, consumptive disease, and overstrain, it will result in retention of blood flow in the vessels or organs, a pathological condition named blood stasis. The cognitive function will decline, due to long-term global hypo-perfusion in cerebral blood flow or acute focal stroke in memory-related cerebral parenchyma [17].

2.1.3. Toxin

As the function of internal organs in the elderly decline, the balance between host defense and external toxins in the body is disrupted. Pathological or physiological products occur and form toxin including waste of “water” and “endogenous fire”, which result from the poor digestion, accumulates into phlegm and retention of fluid, and caused by mental disorder, attack from pathological factors, and imbalance within the body, respectively. If such toxins can not be eliminated quickly the blood circulation and mental acuity will be affected, eventually contributing to the onset of dementia.

2.2. Therapy of TCM

TCM has a long history for preventing and treating cognitive decline. Although AD is a modern disease entity and has no direct analogue in the ancient Chinese medicine literature, disorders of memory and cognitive deficit are referred to throughout the classical literature. For example, in Sheng Nong Ben Cao Jing (Han dynasty, 1-2 century), the earliest pharmacopeia existing on materia medica in China, some TCM ingredients such as Yuan Zhi (Thinleaf milkwort), Ren Shen (Ginseng), Huang Lian (Golden thread), and Long Yan (Longan) were recorded to ameliorate the decline of people's memory.

In this study, 27 ancient TCM books were selected, which could be divided into 3 types, namely, Pharmacopoeias, formulae monographs and renowned TCM doctor's case studies.

A database was established to determine the frequency of herbs in these documents. Totally 236 formulae for improving cognitive function were identified among 27 books mentioned above (Table 1); 139 herbs were gathered from those 236 formulae and 10 TCM herbs were prioritized due to the highest frequency over 50 times (Table 2).

Table 1.

TCM formulae selected from ancient Chinese documents.

| Classification | Book name | Dynasty | Formulae amount |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacopoeia | Sheng Ji Zhong Lu | Song (10–13 century) | 45 |

| Tai Ping Hui Min He Ji Ju Fang | Song (10–13 century) | 2 | |

| Tai Ping Sheng Hui Fang | Song (10–13 century) | 2 | |

| Pu Ji Fang | Ming (14–17 century) | 2 | |

| Yi Fang Lei Ju | Ming (14–17 century) | 2 | |

| Yi Zong Jin Jian | Qing (17–19 century) | 9 | |

|

| |||

| Formulae monographs | Zhou Hou Fang | Jin (3-4 century) | 1 |

| Qian Jin Yao Fang | Tang (7–10 century) | 3 | |

| Ren Zhai Zhi Zhi Fang Lun | Song (10–13 century) | 3 | |

| Fu Ren Da Quan Liang Fang | Song (10–13 century) | 1 | |

| Shi Zhai Bai Yi Xuan Fang | Song (10–13 century) | 5 | |

| Shi Yi De Jiu Fang | Yuan (13-14 century) | 4 | |

| Qi Xiao Liang Fang | Ming (14–17 century) | 29 | |

| Gu Jin Yi Jian | Ming (14–17 century) | 1 | |

| She Sheng Zhong Miao Fang | Ming (14–17 century) | 1 | |

| Zheng Zhi Bao Jian | Qing (17–19 century) | 1 | |

| Ji Yan Liang Fang | Qing (17–19 century) | 4 | |

|

| |||

| Medical edition | Yan Yonghe's medical edition | Song (10–13 century) | 13 |

| Chen Wuze's medical edition | Song (10–13 century) | 9 | |

| Dan Xi Xin Fa | Yuan (13-14 century) | 4 | |

| Shou Shi Bao Yuan | Ming (14–17 century) | 21 | |

| Jing Yue Quan Shu | Ming (14–17 century) | 21 | |

| Zheng Ti Lei Yao | Ming (14–17 century) | 2 | |

| Lei Zheng Zhi Chai | Qing (17–19 century) | 16 | |

| Bian Zheng Lu | Qing (17–19 century) | 16 | |

| Zha Bing Yuan Liu Xi Zhu | Qing (17–19 century) | 2 | |

| Yi Xue Zhong Zhong Can Xi Lu | Modern (20 century) | 7 | |

|

| |||

| Sum | 236 | ||

Table 2.

Top 10 memory-improving TCM herbs.

| Chi name | English name | Latin name | Part | Plant | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fu Ling | Poria | Poria cocos | Sclerotium | Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf | 182 |

| Ren Shen | Ginseng | Radix et rhizoma ginseng | Root, stem | Panax ginseng C. A. Mey. | 169 |

| Yuan Zhi | Thinleaf milkwort | Radix polygalae | Root | Polygala tenuifolia willd. Polygala sibirica L. | 139 |

| Gan Cao | Licorice | Radix et rhizoma glycyrrhizae | Root, stem | Glycyrrhiza inflata Bat. Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. Glycyrrhiza grabra L. | 100 |

| Dang Gui | Chinese Angelica | Radix Angelica sinensis | Root | Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels | 84 |

| Shi Chang Pu | Grassleaf sweelflag rhizome | Rhizoma acori tatarinowii | Stem | Acorus tatarinowii Schott. | 80 |

| Suan Zao Ren | Spina date seed | Semen ziziphi spinosae | Seed | Ziziphus jujuba Mill.var.spinosa. (Bunge) Hu ex H.F. Chou | 79 |

| Shu Di Huang | Prepared rehmannia root | Radix rehmanniae | Root | Rehmannia glutinosa Libosch. | 62 |

| Mai Dong | Dwarf lilyturf tuber | Radix ophiopogonis | Root | Ophiopogon japonicus (L.f.) Ker-Gawl. | 62 |

| Sheng Jiang | Fresh ginger | Rhizoma zingiberis | Stem | Zingiber officinale Rosc. | 53 |

(Note: data are cited from Pharmacopoeia of PR China 2005).

According to specification documented in Chinese Pharmacopeia [18], (i) Poria cocos is a diuretic with capacity to invigorate spleen function and calm the mind. Clinically, it is applicable for memory decline due to spleen deficiency and phlegm blockage; (ii) Radix polygalae is able to anchor the mind and eliminate the phlegm, and indicated in forgetfulness and insomnia; (iii) Radix glycyrrhizae is a qi tonic to invigorate the stomach and spleen, resolve phlegm, and clear away heat and toxin; (iv) Radix Angelica sinensis, as a vital blood tonic and antithrombotic agent, is especially used to treat stroke and poststroke vascular dementia induced by blood stasis; (v) Radix rehmanniae is another tonic used to reinforce kidney essence and marrow. Because of functionality to invigorate the energy, activate blood circulation, or eliminate the toxin, these herbs can be prescribed along or combined to exhibit a good therapeutic effect for senile dementia, for example, Zhi Ling Tang [19].

3. Evidence-Based Efficacy of TCM Herbs on Cognitive Decline

3.1. Poria cocos

Poria cocos (Chinese name: Fu Ling) is the dried sclerotium of the fungus, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf (Fam. Polyporaceae).

3.1.1. Functionality/Efficacy

There is suggestive evidence that P. cocos is memory improving regardless of absence of available clinical reports. Pharmacological research exhibited that the water extract of P. cocos enhanced hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP) and improved scopolamine-induced spatial memory impairment in rats ([20, 21], Table 3).

Table 3.

Memory-improving and neuro-protective effects of Poria cocos.

| Test | Test materials/dose | Test model | Endpoints/biomarkers | Effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vivo | Extracts 20–100 mg/kg | Scopolamine-treated rats | Eight-arm radial maze | Improve spatial memory | [20] |

| Extracts 250–500 mg/kg | Innate rats | Electro-physiology Spike amplitude | Enhance hippocampal LTP | [21] | |

| Methanol extracts 200 mg/mL | Ellman ChE | ChE activity | Inhibit ChE by 27.8% | [22] | |

| Aqueous extracts 0.2 mg/mL | Innate ICR mice | AChE activity | Inhibit AChE by 13.9% | [23] | |

|

| |||||

| In vitro | Aqueous extracts 31–250 μg/mL | Brain neurons–neonatal rats | Cytosolic [Ca2+] i | Regulate bi-directly [Ca2+] i | [24] |

Long-term potentiation (LTP); choline esterase (ChE); acetylcholinesterase (AChE).

3.1.2. Mechanism of Action

Its cognitive action has been ascribed to slight cholinesterase (ChE) or acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibition and bidirectional regulation on cytosolic free calcium ([22–24], Table 3).

3.1.3. Active Principles

The responsible actives for the cognitive benefits are unclear for the time being. Triterpene acids and polysaccharides are principal constituents of P. cocos, responsible for diverse bioactivities, including antitumor, anti-inflammatory, nematicidal, antioxidant, antirejection, antiemetic effects, as inhibitors against DNA topoisomerases, phospholipase A2. Besides, lecithin and choline present in the fungus are beneficially nutritional substance [25–29].

3.2. Radix polygalae

Radix polygalae is the root Polygala tenuifolia Willd. or P. sibirica L. (Fam. Polygalaceae), used as a cardiotonic and cerebrotonic, sedative and tranquilliser, and for amnesia, neuritis, and insomnia [30, 31].

3.2.1. Functionality/Efficacy

There is strong support that thinleaf milkwort root is memory improving. BT-11, the extract of dried root of Radix polygalae, was developed in Korea as a functional diet with cognitive enhancing activity. Elderly with subjective memory impairment and mild cognitive impairment ascend with oral BT-11 at 300 mg/d for 4–8 weeks. Except for mild dyspepsia, no adverse events were reported [32, 33].

3.2.2. Mechanism of Action

A number of investigations also sustained that Radix polygalae extracts functioned to promote neuronal proliferation and neurite outgrowth in normal brain and improve memory impaired by scopolamine, stress, nucleus basalis magnocellularis-lesioning operation via a variety of molecular pathways, including increasing glucose utilization and inhibiting AChE activity. Besides nootropic effects, Radix polygalae extracts protected neurons against insults induced by NMDA, glutamate, and Aβ ([34–39], Table 4(a)). In addition, anti-inflammatory activity probably contributed to the cognitive and neuroprotective efficacy, as Radix polygalae extracts inhibited interleukin-1 (IL-1)-mediated tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α secretion, and ethanol-induced IL-1 secretion by astrocytes [40, 41].

Table 4.

(a) Memory-improving and neuro-protective effects of Radix polygalae

| Test | Test materials/dose | Test model | Endpoint/biomarkers | Effects | Mechanisms | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinic | Extracts 300 mg/d, 4 w | Healthy Korean elderly with subjective memory impairment and mild cognitive impairmentdouble-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, parallel study | Korean version of California verbal learning testSelf-ordered pointing test | Improve verbal memory No adverse events, except mild dyspepsia | N.A. | [32, 33] |

|

| ||||||

| In vivo | Extracts i.p., 2 mg/kg | Innate rats | Nestin/BrdU Tuj1/BrdU | Improve memory Promote neuro-genesis | Promote proliferation Promote neurite outgrowth | [34] |

| Extracts | Stress-treated rats | Glucose utilization Cell adhesion molecule | Improve memory | Increase glucose utilization Increase total NCAM | [35] | |

| Extracts 2 g/kg, 1–3 w | NBM-lesioning rats | Neurological test Step-through test | Improve memory | N.A. | [36] | |

| Extracts i.p., 10 mg/kg | Scopolamine-treated rats | Passive avoidance test water maze test AChE | Improve memory | Inhibit AChE | [36] | |

|

| ||||||

| In vitro | Extracts 0.5–5 μg/mL | Rat primary neurons exposed to Glutamate or Aβ | Cell viability | Protect neurons | N.A. | [37] |

| Extracts 0.05–5 μg/mL | Rat cerebellar granule neurons exposed to NMDA | Glutamate release (Ca2+)i/ROS | Protect neurons | N.A. | [38] | |

| Extracts 0.1–100 μg/mL | Rat cortical neurons exposed to Aβ 25–35 | Axonal length Neuro-filament-H/MAP-2Cell viability | Activate axonal extension Protect neurons | N.A. | [39] | |

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE); bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU); microtubule-associated protein-2 (MAP-2); nucleus basalis magnocellularis (NBM); neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM); N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA); reactive oxygen species (ROS); β amyloid (Aβ); not available (N.A.); intraperitoneally (ip.).

(b) Memory-improving and neuro-protective effects of active components from Radix polygalae

| Test | Test materials/dose | Test model | Endpoints/biomarkers | Effects | Mechanisms | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vivo | Sinapic acid 10–100 mg/kg | Scopolamine-treated rats | Radial maze test | Improve memory | N.A. | [42, 43] |

| Sinapic acid 3–100 mg/kg, 1 h | Scopolamine-treat mice Basal forebrain lesioning mice | Step-through test Ach/ChAT | Improve memory | N.A. | [49] | |

| Tenuifolin 20–80 mg/kg, 15 d | Aged mice Dysmnesia mice | Step-down test Y maze trial AChE,NE,DA,5-HT | Improve memory | Increase NE and DA Inhibit AChE | [45] | |

| Tenuigenin 18.5–74 mg/kg | Aβ 1-40-treated rats ibotenic acid-treated rats | Step-through test AchE, ChAT | Improve memory | Cholinergic | [46] | |

| Acylated oligosaccharides1–10 mg/kg | Scopolamine-treated rats | Step-through test | Improve memory | Cholinergic | [44] | |

|

| ||||||

| In vitro | Tenuigenin 1–4 μg/mL | APP-transfected SH-SY5Y cells | Fluorescence resonance energy transfer | Inhibit Aβ secretion | Inhibit BACE1 | [47] |

| Onjisaponin 10 μM | Serum deficiency or glutamate-treated PC12 cells | Cell survival | Protect PC 12 cells | N.A. | [48] | |

Acetylcholine (Ach); acetylcholinesterase (AChE); choline acetyltransferase (ChAT); 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT); dopamine (DA); norepinephrine (NE); beta-site APP cleaving enzyme (BACE); amyloid precursor protein (APP); β amyloid (Aβ); not available (N.A.).

3.2.3. Active Principles

Phytochemically, Radix polygalae mainly contains a variety of active constituents, including saponins, xanthones, and acylated oligiosaccharides [42–44].

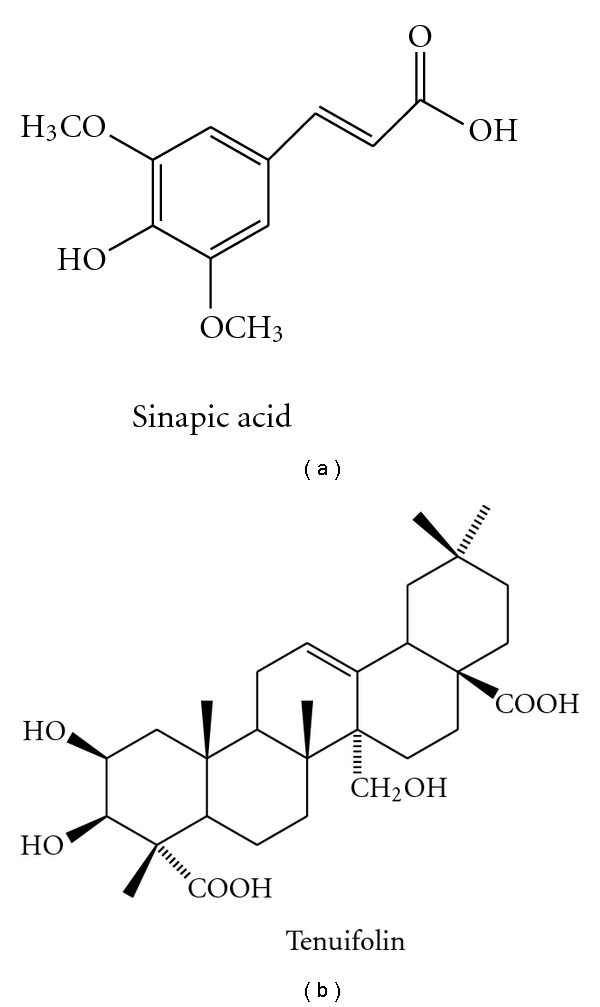

Saponins, especially tenuifolin isolated from tenuigenin might reinforce cognitive performance in aged and dysmnesia mice, via elevating levels of dopamine (DA) and norepinephrine (NE), and inhibiting AChE activity (Figure 1). Meanwhile, onjisaponin indicated cytoprotective activity in PC12 cells, exposed to serum deficiency or glutamate. In addition, tenuigenin facilitated memory in rats, damaged by Aβ 1–40 or ibotenic acid, via enhancing cholinergic function, or inhibiting Aβ secretion ([45–48], Table 4(b)).

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of sinapic acid and tenuifolin.

Few phytochemical principles have been isolated and identified as CNS active components. Besides tenuifolin, sinapic acid [49], a common moiety of tenuifoliside B and 3, 6′-disinapoylsucrose, reversed memory deficit induced by scopolamine and basal forebrain lesion (Table 4(b), Figure 1).

3.3. Radix et Rhizoma Glycyrrhizae

Radix et rhizoma glycyrrhizae is the dried root and rhizome, generally derived from a different plant species, with similar properties, including Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch., G. inflata Bat., or G. glabra L. (Fam. Leguminosae).

3.3.1. Functionality/Efficacy

The extracts of Radix glycyrrhizae reversed the cognitive deficits induced by diazepam, scopolamine, and beta-amyloid peptide 25–35 in mice at doses of 75, 150, and 300 mg/kg per oral, or diet containing either 0.5 or 1% extract, through anti-AChE and antioxidant activities. In addition, roasted licorice extracts elicited neuroprotection against brain damage after transient forebrain ischemia in Mongolian gerbils, behind which antioxidant activity was also implicated, for example, maintaining superoxide dismutase (SOD)1 level in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells ([50–54], Table 5).

Table 5.

Memory-improving and neuro-protective effects of Radix et rhizoma glycyrrhizae.

| Test | Test materials /dose | Test model | Endpoint/biomarkers | Effects | Mechanisms | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vivo | Extracts 75–300 mg/kg, 7d diet 0.5 or 1%, 6w | Diazepam treated mice | Elevated plus-maze test | Improve memory | Cholinergic | [50] |

| Scopolamine treated mice | passive avoidance test | [51] | ||||

| Aβ 25–35 treated mice | passive avoidance testMorris water-maze test TBARS/Catalase/AChE | Improve memory | Quench oxidative stress Inhibit AChE | [52] | ||

| Aqueous extracts 150 mg/kg, 7d n-hexane extracts 5 mg/kg, 3d | Innate mice | AChE | Inhibit AChE | N.A. | [53] | |

| Methanol extract 50–100 mg/kg, 21d | IR treated Mongolian gerbils | Cu, Zn-SOD1CA1 pyramidal cells | Protect neurons | Restore Cu, Zn-SOD1 | [54] | |

| Liquiritigenin 2.3–21 mg/kg, 7d | Aβ (25–35)-treated rats | Morris water maze testReference memory taskProbe taskTwo-way shuttle avoidance taskMAP, Nissle, Notch-2 | [55] | |||

|

| ||||||

| In vivo | Isoliquiritigenin 5–20 mg/kg, 7d | MCAO-treated rats | MDASOD,GSH-Px, CatalaseNa+-K+-ATPase, ATPEnergy charge, total adenine nucleotides | Protect brain | Promote energy metabolismInhibit oxidative stress | [56] |

| Glabridin 1–4 mg/kg, 3d | Innate Mice | ChE | Improve memory | Inhibit ChE | [57] | |

| Glabridin 5–25 mg/kg | IR-treated rats Staurosporine-treated neurons | MDA, GSH and SODBax, caspase-3,bcl-2 | Protect neurons | Inhibit apoptosisInhibit oxidative stress | [58] | |

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE); cholinesterase (ChE); thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARS); superoxide dismutase (SOD); malondialdehyde (MDA); glutathione (GSH); microtubule-associated protein (MAP) 2; middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO); β amyloid (Aβ); Ischemia-reperfusion (IR); not available (N.A.).

3.3.2. Mechanism of Action and Active Principles

Radix glycyrrhizae contains glycyrrhizin, glycyrrhizic acid, glabridin and derivatives, glabrol, glabrene, 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, glucoliquiritin apioside, prenyllicoflavone A, shinflavone, shinpterocarpin, 1-methoxyphaseollin, salicylic acid, and derivatives, as well as other saponins, flavonoid glycosides, and flavonoids.

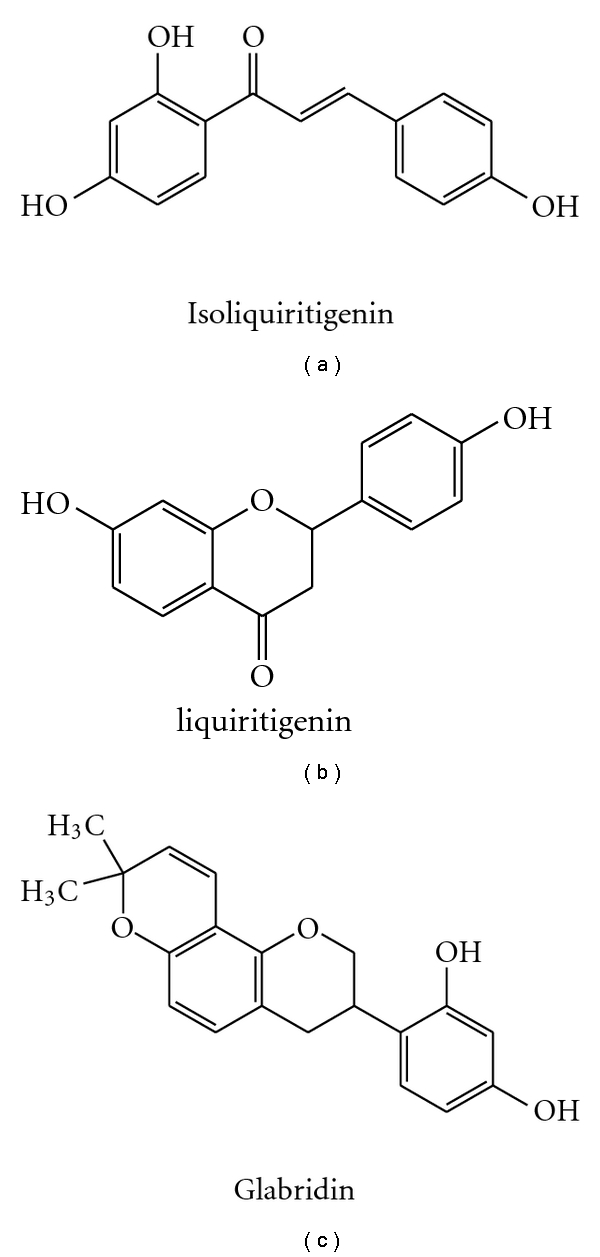

Isoliquiritigenin, liquiritigenin, and glabridin have been identified from the Radix glycyrrhizae to be possible bioactive compounds ([55–58], Table 5, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of isoliquiritigenin, liquiritigenin, and glabridin.

Isoliquiritigenin also has the protective potential against transient middle cerebral artery occlusion-induced focal cerebral ischemia in rats, at the doses of 5, 10, and 20 mg/kg. Its protection may be attributed to amelioration of cerebral energy metabolism and antioxidant property.

Liquiritigenin, a plant-derived highly selective estrogen receptor β agonist has been identified to alleviate the cognitive recession in the elders.

Glabridin appears to be an active isoflavone as it improved learning and memory in mice at 1, 2, and 4 mg/kg, through targeting at ChE. Glabridin had a protective effect on cerebral ischemia injury, and neuron insult induced by staurosporine at 5, 25 mg/kg (i.p). Its underlying mechanism is probably linked to antioxidant and antiapoptotic activity.

Glabrene also could be beneficial to memory due to estrogen-like activities, like isoliquiritigenin, liquiritigenin, and glabridin [59–61].

3.4. Radix Angelica sinensis

Radix Angelica sinensis (Chinese: Danggui, Dong quai, Donggui; Korean Danggwi), is the dried root of Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels (Umbelliferae).

3.4.1. Functionality/Efficacy

Behaviour test displayed that Radix Angelica sinensis extracts ameliorated scopolamine and cycloheximide, but not p-chloroamphetamine-induced amnesia at 1 g/kg bw. In addition in vitro study showed that Radix Angelica sinensis extracts prevented the neurotoxicity induced by Aβin Neuro 2A cells, at the doses ranging 25–200 μg/mL, through antioxidant pathway ([62, 63], Table 6(a)). Furthermore, estrogenic activity of Angelica sinensis will probably help alleviate peri- or postmenopausal symptoms including cognitive decline in women [64, 65].

Table 6.

(a) Memory-improving and neuro-protective effects of Radix Angelica sinensis

| Test | Test materials/dose | Test model | Endpoint/biomarkers | Effects | Mechanisms | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vivo | Extracts 1 g/kg | scopolamine-treated rats cycloheximide-treated rats | Step-through test | Improve memory | N.A. | [62] |

| In vitro | Extracts 25–200 μg/ml | Aβ-treated Neuro 2A cells | MTT assay/ΔΨm ROS/LPO/GSH | Protect neurons | Quench oxidative stress | [63] |

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT); Lipid peroxidation (LPO); mitochondrial transmembrane potential (ΔΨm); β amyloid (Aβ); glutathione (GSH); not available (N.A.).

(b) Memory-improving and neuro-protective effects of active components from Radix Angelica sinensis

| Test | Test materials/dose | Test model | Endpoint/biomarkers | Effects | Mechanisms | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vivo | Ferulic acid s.c., 5 mg/kg/d, 6 d | dl-buthionine-(S,R)-Sulfoximine treated mice | Object recognition test Oxidative carbonyl protein | Improve memory | Elevate carbonyl protein | [66] |

| Ferulic acid 28 d | Trimethyltin-treated mice | Y-maze testPassive avoidance testChAT | Improve memory | Activate ChAT | [67] | |

| Ferulic acid i.p., 20–80 mg/kg, 3 d | Glutamate-treated mice | Behavioral test histopathology [(3)H]-labeled glutamate bcl-2/caspase-3 | Protect brain | NMDA receptor antagonist | [68] | |

| Ferulic acid 0.006%, 4 w | Aβ1-42-treated mice | Step-through test Y-maze test Water maze test GFAP/IL-1 β | Improve memoryProtect brain | Suppress astrocytes immunoreactivities | [69] | |

| Ferulic acid 50–100 mg/kg | Scopolamine-treated rats Cycloheximide-treated rats | Step-through test | Improve memory | Cholinergic Enhance CBF | [70] | |

| Z-ligustilide 10–40 mg/kg, 4 w | CCAO-treated rats | Morris water maze Neurons/astrocytes count MDA/SOD/ChAT/AChE | Improve memory | Inhibit oxidative stress Cholinergic | [71] | |

| Z-ligustilide 20–80 mg/kg | MCAO-treated rats | TTC staining Brain swelling Behavioural score | Protect brain | N.A. | [72] | |

| Z-ligustilide 5–20 mg/kg | IR-treated ICR mice | TTC staining MDA/GSH-Px/SOD Bcl-2/Bax/caspase-3 | Protect brain | Inhibit oxidative stress Inhibit apoptosis | [73] |

Choline acetyltransferase (ChAT); cerebral blood flow (CBF); glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP); interleukin-1 (IL-1); glutathione peroxidase (GSH-PX); 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC); subcutaneously (s.c.); ischemia-reperfusion (IR); superoxide dismutase (SOD); malondialdehyde (MDA); acetylcholinesterase (AChE); common carotid arteries occlusion (CCAO); middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO); β amyloid (Aβ); N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA); not available (N.A.).

3.4.2. Mechanism of Action and Active Principles

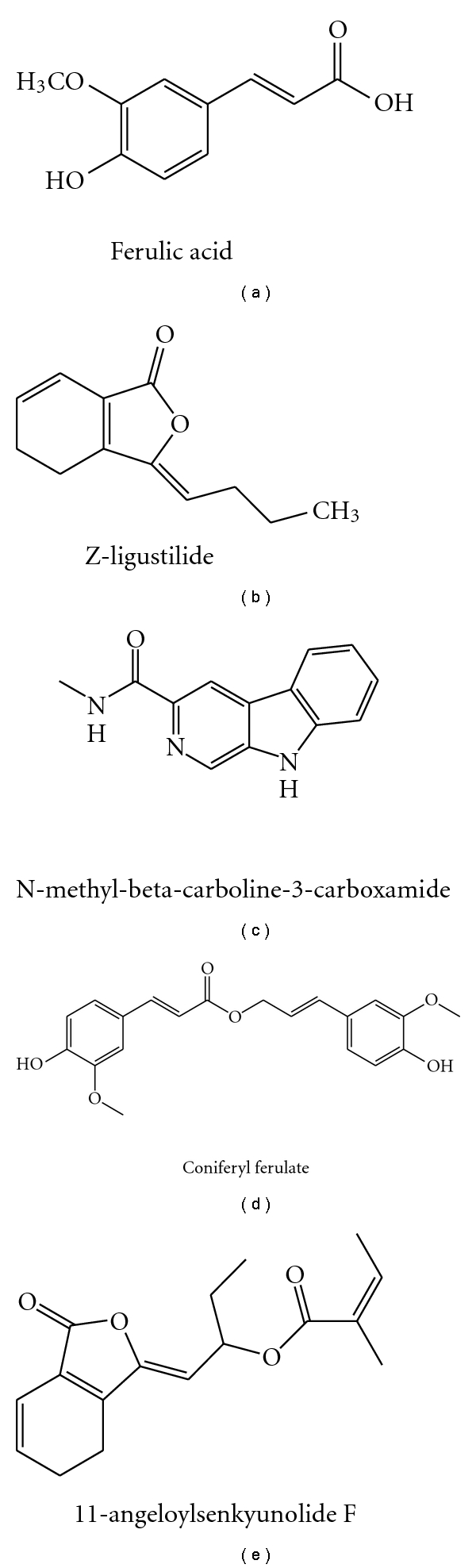

Ferulic acid has been identified to be an active principle because it may reverse memory deficits induced by a variety of toxins, including dl-buthionine-(S,R)-sulfoximine, trimethyltin, glutamate, Aβ1-42, scopolamine, and cycloheximide. Multiple mechanisms are probably implicated into its cognitive benefits, including inhibition on oxidative stress, activation of ChAT or enhance the cholinergic activities, competitive N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonism, suppression on immunoreactivities of the astrocyte, and facilitation of cerebral blood flow ([66–70], Table 6(b), Figure 3).

Z-ligustilide has been identified to be another active component from volatile of Radix Angelica sinensis. It may protect brain and cognition especially against focal and global ischemia induced by permanent common carotid arteries occlusion (CCAO) and transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) [71–73], (Table 6(b), Figure 3).

Additionally, N-methyl-beta-carboline-3-carboxamide, Coniferyl ferulate, and 11-angeloylsenkyunolide F were identified to be anti-AD components probably by inhibiting Aβ1-40 induced toxicity and AChE activity ([62, 74], Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Chemical structures of ferulic acid, Z-ligustilide, N-methyl-beta-carboline-3-carboxamide, coniferyl ferulate, and 11-angeloylsenkyunolide F.

3.5. Radix rehmanniae

Radix rehmanniae is the roots of Rehmannia glutinosa Libosch., family Scrophulariaceae.

3.5.1. Functionality/Efficacy

There have been growing evidences that Radix rehmanniae extract possesses significant neuroprotective activity ([75, 76], Table 7).

Table 7.

Memory-improving and neuro-protective effects of Radix rehmanniae.

| Test | Test materials/dose | Test model | Endpoint/biomarkers | Effects | Mechanisms | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vivo | Extracts 4.5–9.0 g/kg | MSG-treated rats | Morris maze test Step-down test c-fos, NGF expression | Improve memory | Motivate hippocampal c-fos /NGF expression | [75] |

| Extracts 4.5–9.0 g/kg | MSG-treated rats | Morris maze test Step-down test NMDA-R1, GABA-R Glutamine, GABA levels | Improve memory | Motivate hippocampal NMDA-R1/GABA-R expression adjust Glutamine/GABA levels | [77] | |

|

| ||||||

| In vitro | Extracts 0.1–1.0 mg/mL, 1–3 d | C6 glioblastoma cells | GDNF gene expression | Stimulate GDNF expression | Up-regulate cPKC/ERK1/2 pathways | [76] |

|

| ||||||

| In vivo | Catalpol i.p., 10 mg/kg, 10 d | LPS-treated mice | MMPNF-κB | Improve memoryInhibit inflammation | Inhibit NF-κB activation protect mitochondrial function | [78] |

| Catalpol 2.5–10 mg/kg, 2 w | D-galactose-treated mice | Passive avoidance test LDH, GSH-ST, GS, CK | Improve memory | Inhibit oxidative stress Maintain energy metabolism | [79–81] | |

| Catalpol i.p., 1–10 mg/kg | IR-treated Gerbils | Bcl-2, Bax, NO | Protect CA1 neuronsImprove memory | Inhibit apoptosis Inhibit oxidative stress | [82–84] | |

| Catalpol i.p., 5 mg/kg, 10 d | Aged rats | GAP-43/synaptophysin PKC, BDNF | Protect neuroplasticity | Up-regulate PKC and BDNF (hippocampus) | [85] | |

|

| ||||||

| In vitro | Catalpol 0.5 mM, 1 h | MPTP-treated neurons | Cells Viability, MAO-B, ROS, MCI, MMP, MPT | Protect neurons | Protect mitochondriaMaintain MAO-B activity | [86] |

| Catalpol 0.5 mM, 30 min | Aβ1-42-treated Cortical neurons-glia | Cells Viability TNF-α, iNOS, NO, ROS | Protect neurons | Inhibit inflammation | [87] | |

| Catalpol 0.25–5 mg/ml | Primary rat cortical neurons | Cells Viability NF-200 antigen | Enhance axonal growthNo impact on survival | N.A. | [88] | |

| Catalpol 0.1–100 μg/ml | OGD-treated PC12 cells | Bcl-2, caspase-3/MMP SOD, GSH-Px | Inhibit apoptosis | Retain Bcl-2 and MMP suppress caspase-3 activation maintain SOD and GSH-Px | [89] | |

| Catalpol 0.1–1.0 mM | H2O2-treated PC12 cells | Bcl-2 cytochrome c caspase | Protect neuronsInhibit apoptosis | Prevent cytochrome c release Inactivate caspase cascade | [90] | |

| Catalpol 0.05–0.5 mM | H2O2-treated astrocytes | Cells Viability ROS | Inhibit oxidative stress | maintain glutathione Scavenge ROS | [91] | |

| Catalpol 0.3–275.9 μM, 24 h | OGD-treated mice astrocytes | Cell survival/MMP ROS, NO, iNOS, MDASOD, GSH-Px, GSH | Protect astrocytes | Inhibit oxidative stress | [92] | |

Nerve growth factor (NGF); oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD); lactate dehydrogenase (LDH); glutathione S-transferase (GSH-ST); glutamine synthetase (GS); creatine kinase (CK); mitochondrial complex I (MCI); mitochondrial membrain potential (MMP); mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT); brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF); γ-amiobutyic acid (GABA); lactate dehydrogenase (LDH); nitric oxide (NO); inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS); nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB); protein kinase C (PKC); 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP); monosodium glutamate (MSG); lipopolysaccharide (LPS); ischemia-reperfusion (IR); monoamine oxidase (MAO); tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α; reactive oxygen species (ROS); superoxide dismutase (SOD); malondialdehyde (MDA); glutathione (GSH); glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px); glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF).

3.5.2. Mechanism of Action

Radix rehmanniae extract improved learning and memory in rats with Monosodium-glutamate-(MSG-) injured thalamic arcuate nucleus at 4.5, and 9.0 g/kg, through adjusting glutamates and γ-amiobutyic acid (GABA) levels, as well as increasing the expression of hippocampal c-fos, nerve growth factor (NGF), NMDA receptor 1, and GABA receptor. Moreover, Rehmannia extract stimulated glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) gene expression in C6 glioblastoma cells, through upregulating cPKC and ERK 1/2 pathways ([76, 77], Table 7).

3.5.3. Active Components

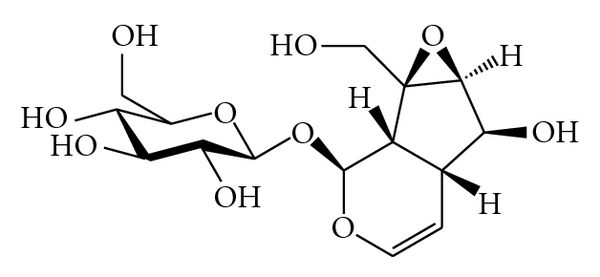

Catalpol, an iridoid glycoside, was isolated from the fresh Radix rehmanniae. It exists broadly in many plants all over the world and has many biological functions such as anti-inflammation, promoting of sex hormones production, protection of liver damage, and reduction of elevated blood sugar.

Recently, catalpol has been identified as a vital active with robust cognitive potential (Figure 4). Behaviour studies exhibited that catalpol reversed brain damage and memory deficits in mice induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and D-galactose and in gerbils by cerebral ischemia. The nootropic and neuroprotective efficacy of catalpol probably resulted from a variety of underlying molecular mechanisms (Table 7).

Figure 4.

Chemical structure of catalpol.

Antioxidant activity: catalpol promoted endogenous antioxidant enzyme activities, superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), and antioxidant glutathione (GSH), cut down malondialdehyde (MDA) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation in PC12 cells and astrocytes primary cultures, exposed to oxygen and glucose deprivation or H2O2, and in senescent mice induced by D-galactose [79–81, 86, 89, 91, 92].

Anti-inflammatory activity: catalpol significantly reduced the release of ROS, TNF-α, nitric oxide (NO) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression after Aβ (1–42)-induced microglial activation in primary cortical neuron-glia cultures, and LPS-induced nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) activation in mice [78, 87].

Neurogenetic activity: catalpol can enhance axonal growth of cortical neurons cultured in vitro from 24 h newly born rat, at 1–5 mg/mL and ameliorate age-related presynaptic proteins decline (synaptophysin and GAP-43), and neuroplasticity loss in the hippocampus of the aged rats, by upregulating protein kinase C (PKC) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [85, 88].

Antiapoptotic activity: catalpol not only suppressed the downregulation of Bcl-2, upregulation of Bax, and the release of mitochondrial cytochrome c to cytosol, but also attenuated caspase-3 activation, poly-ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) cleavage, and eventually protected against H2O2-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells and in the ischemic dorsal hippocampus of gerbils subject to CCAO [82–84, 90].

In addition, the function to stimulate the production of adrenal cortical hormones, which increases the production of sex hormones, is likely implicated into the cognitive benefit of catalpol in menopausal women [92].

4. Discussion and Conclusion

TCM has a long history of human use for mental health. The current literature survey addressing traditional evidence from human studies has been primarily carried out. The top 10 TCM herb ingredients were identified. Poria, thinleaf milkwort, licorice, Chinese Angelica, and Rehmannia were further prioritized to have the highest potential benefit to dementia intervention, due to their highest frequency of use in 236 formulae collected from 29 ancient Pharmacopoeias, ancient formula books, or historical archives on ancient renowned TCM doctors, over the past 10 centuries.

In TCM philosophy, AD is assumed to be induced by kidney essence vacuity and toxin (turbid phlegm). The amnestic mild cognitive impairment in elderly population has been disclosed in a clinical investigation to correlate with kidney essence vacuity and turbid phlegm blocking upper orifices. The whole cognitive function may worsen because of the aggravation of kidney essence vacuity, deficiency of blood and qi, phlegm and heat toxin and may eventually lead to multiple cognitive domains impairment, even dementia [93].

Based on the history of use, there is strong clinical support that Radix polygalae is memory improving since its efficacy has been demonstrated in elderly with mild cognitive decline [32, 33]. There is suggestive evidence that Poria cocos, Radix glycyrrhizae, Radix Angelica sinensis, or Radix rehmanniae are memory improving, though modern clinical reports concerning the four herbs are absent yet.

Furthermore, pharmacological investigations in 39 animal studies and 18 in vitro studies also indicated that the five ingredients can elicit memory-improving effects via multiple mechanisms of action, covering estrogen-like, cholinergic, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antiapoptotic, Neurogenetic, and anti-Aβ activities. These mechanisms are in well accordance with modern pharmacotherapy for AD and VD, by prescribing ChEIs, anti-inflammatory mediations, antioxidants, estrogen, neurotrophic factors, and nootropics, depending on difference situations.

In the meantime, 11 active molecules have also been identified, including sinapic acid, tenuifolin, isoliquiritigenin, liquiritigenin, glabridin, ferulic acid, Z-ligustilide, N-methyl-beta-carboline-3-carboxamide, coniferyl ferulate and 11-angeloylsenkyunolide F, and catalpol. Most of them are lipophilic compounds with comparatively low-molecular weight (200 ~ 700) and likely to be absorbed into blood and distributed to brain according to Lipinski rule of 5 [94]. The 11 compounds can serve as active markers for characterisation and standardization of corresponding TCM herbal extracts and pharmacokinetics markers for bioavailability study. In drug discovery, these phyto-chemicals can also be used as candidates to optimize derivatives [95].

Taken together, it is concluded that TCM could have a complementary and alternative role in preventing and treating cognitive disorder in the elderly. The scientific evidence is being continuously mined to back up the traditional medical wisdom and product innovation in the healthcare sectors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Domenic Caravetta from Unilever R&D Shanghai and Dr. Jan Koek from Unilever R&D Vlaardingen for reviewing the paper.

References

- 1.Nestler EL, Hyman SE, Malenka RC. Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience. New York, NY, USA: McGraw-Hill; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dominguez DI, Strooper BD. Novel therapeutic strategies provide the real test for the amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2002;23(7):324–330. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(02)02038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sugimoto H. The new approach in development of anti-Alzheimer’s disease drugs via the cholinergic hypothesis. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 2008;175(1–3):204–208. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rojo LE, Fernández JA, Maccioni AA, Jimenez JM, Maccioni RB. Neuroinflammation: implications for the pathogenesis and molecular diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Archives of Medical Research. 2008;39(1):1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Praticò D, Trojanowski JQ. Inflammatory hypotheses: novel mechanisms of Alzheimer’s neurodegeneration and new therapeutic targets? Neurobiology of Aging. 2000;21(3):441–445. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00141-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markesbery WR. Oxidative stress hypothesis in Alzheimer’s disease. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 1997;23(1):134–147. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(96)00629-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Savioz A, Leuba G, Vallet PG, Walzer C. Contribution of neural networks to Alzheimer disease’s progression. Brain Research Bulletin. 2009;80(4-5):309–314. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gleason CE, Cholerton B, Carlsson CM, Johnson SC, Asthana S. Neuroprotective effects of female sex steroids in humans: current controversies and future directions. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2005;62(3):299–312. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4385-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atwood CS, Bowen RL. The reproductive-cell cycle theory of aging: an update. Experimental Gerontology. 2010;46(2-3):100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ott A, Breteler MMB, Van Harskamp F, et al. Prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia: association with education. The Rotterdam study. British Medical Journal. 1995;310(6985):970–973. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6985.970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ritchie K, Lovestone S. The dementias. Lancet. 2002;360(9347):1759–1766. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11667-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parihar MS, Hemnani T. Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis and therapeutic interventions. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 2004;11(5):456–467. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson CN, Roland A, Upton N. New symptomatic strategies in Alzheimer’s disease. Drug Discovery Today: Therapeutic Strategies. 2004;1(1):13–19. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adams M, Gmünder F, Hamburger M. Plants traditionally used in age related brain disorders—a survey of ethnobotanical literature. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2007;113(3):363–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anekonda TS, Reddy PH. Can herbs provide a new generation of drugs for treating Alzheimer’s disease? Brain Research Reviews. 2005;50(2):361–376. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howes MJ, Houghton PJ. Plants used in Chinese and Indian traditional medicine for improvement of memory and cognitive function. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2003;75(3):513–527. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(03)00128-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu X, Du J, Cai J, et al. Clinical systematic observation of Kangxin capsule curing vascular dementia of senile kidney deficiency and blood stagnation type. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2007;112(2):350–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission. Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China (2005) Vol. 1. Beijing, China: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yan L, Liu B, Guo W, et al. A clinical investigation on zhi ling tang for treatment of senile dementia. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2000;20(2):83–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hatip-Al-Khatib I, Egashira N, Mishima K, et al. Determination of the effectiveness of components of the herbal medicine Toki-Shakuyaku-San and fractions of Angelica acutiloba in improving the scopolamine-induced impairment of rat’s spatial cognition in eight-armed radial maze test. Journal of Pharmacological Sciences. 2004;96(1):33–41. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fpj04015x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smriga M, Saito H, Nishiyama N. Hoelen (Poria cocos WOLF) and ginseng (Panax Ginseng C.A. MEYER), the ingredients of a chinese prescription DX-9386, individually promote hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo . Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 1995;18(4):518–522. doi: 10.1248/bpb.18.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oh MH, Houghton PJ, Whang WK, Cho JH. Screening of Korean herbal medicines used to improve cognitive function for anti-cholinesterase activity. Phytomedicine. 2004;11(6):544–548. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin Z, Xiao Z, Zhu D, Yan Y, Yu B, Wang Q. Aqueous extracts of FBD, a Chinese herb formula composed of Poria cocos, Atractylodes macrocephala, and Angelica sinensis reverse scopolamine induced memory deficit in ICR mice. Pharmaceutical Biology. 2009;47(5):396–401. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen W, An W, Chu J. Effect of water extract of Poria on cytosolic free calcium concentration in brain nerve cells of neonatal rats. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 1998;18(5):293–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang Q, Jin Y, Zhang L, Cheung PCK, Kennedy JF. Structure, molecular size and antitumor activities of polysaccharides from Poria cocos mycelia produced in fermenter. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2007;70(3):324–333. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang HM, Lee SK, Shin DS, et al. Dehydrotrametenolic acid selectively inhibits the growth of H-ras transformed rat2 cells and induces apoptosis through caspase-3 pathway. Life Sciences. 2006;78(6):607–613. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.05.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu SJ, Ng LT, Lin CC. Antioxidant activities of some common ingredients of traditional chinese medicine, Angelica sinensis, Lycium barbarum and Poria cocos . Phytotherapy Research. 2004;18(12):1008–1012. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sekiya N, Goto H, Shimada Y, Endo Y, Sakakibara I, Terasawa K. Inhibitory effects of triterpenes isolated from Hoelen on free radical-induced lysis of red blood cells. Phytotherapy Research. 2003;17(2):160–162. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin Z, Zhu D, Yan Y, Yu B. Herbal formula FBD extracts prevented brain injury and inflammation induced by cerebral ischemia-reperfusion. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2008;118(1):140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang H, But PP. Pharmacology and Applications of Chinese Material Medica. 1-2. Singapore: World Scientific; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duke JA, Ayensu ES. Medicinal Plants of China. 2nd edition. 1-2. Algonac, Mich, USA: Reference Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jung H, Lee JY, Kim SH, Shin KY, Lee GH, Suh YH. Effect of functional diet Polygala tenuifolia Willdenow extract [BT-11] on memory function of healthy general population. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;17(9):p. S526. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim SH, Jung HY, Yi JS, et al. Effect of functional diet BT-11 [Polygala tenuifolia Willdenow] on subjective memory impairment and mild cognitive impairment in older people. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;16:p. S477. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park HJ, Lee K, Heo H, et al. Effects of Polygala tenuifolia root extract on proliferation of neural stem cells in the hippocampal CA1 region. Phytotherapy Research. 2008;22(10):1324–1329. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shin KY, Won BY, Heo C, et al. BT-11 improves stress-induced memory impairments through increment of glucose utilization and total neural cell adhesion molecule levels in rat brains. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2009;87(1):260–268. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen YL, Hsieh CL, Wu PHB, Lin JG. Effect of Polygala tenuifolia root on behavioral disorders by lesioning nucleus basalis magnocellularis in rat. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2004;95(1):47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park CH, Choi SH, Koo JW, et al. Novel cognitive improving and neuroprotective activities of Polygala tenuifolia willdenow extract, BT-11. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2002;70(3):484–492. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee HJ, Ban JY, Koh SB, et al. Polygalae radix extract protects cultured rat granule cells against damage induced by NMDA. American Journal of Chinese Medicine. 2004;32(4):599–610. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X04002235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Naito R, Tohda C. Characterization of anti-neurodegenerative effects of Polygala tenuifolia in Aβ(25–35)-treated cortical neurons. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2006;29(9):1892–1896. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim HM, Lee EH, Na HJ, et al. Effect of Polygala tenuifolia root extract on the tumor necrosis factor-α secretion from mouse astrocytes. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1998;61(3):201–208. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(98)00040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koo HN, Jeong HJ, Kim KR, et al. Inhibitory effect of interleukin-1α-induced apoptosis by Polygala tenuifolia in Hep H2 cells. Immunopharmacology and Immunotoxicology. 2000;22:531–544. doi: 10.3109/08923970009026010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun XL, Ito H, Masuoka T, Kamei C, Hatano T. Effect of Polygala tenuifolia root extract on scopolamine-induced impairment of rat spatial cognition in an eight-arm radial maze task. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2007;30(9):1727–1731. doi: 10.1248/bpb.30.1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yabe T, Iizuka S, Komatsu Y, Yamada H. Enhancements of choline acetyltransferase activity and nerve growth factor secretion by Polygalae radix-extract containing active ingredients in Kami-untan-to. Phytomedicine. 1997;4(3):199–205. doi: 10.1016/S0944-7113(97)80068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ikeya Y, Takeda S, Tunakawa M, et al. Cognitive improving and cerebral protective effects of acylated oligosaccharides in Polygala tenuifolia . Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2004;27(7):1081–1085. doi: 10.1248/bpb.27.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang H, Han T, Zhang L, et al. Effects of tenuifolin extracted from radix polygalae on learning and memory: a behavioral and biochemical study on aged and amnesic mice. Phytomedicine. 2008;15(8):587–594. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen Q, Cao YG, Zhang CH. Effect of tenuigenin on cholinergic decline induced by β-amyloid peptide and ibotenic acid in rats. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica. 2002;37(12):913–917. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jia H, Jiang Y, Ruan Y, et al. Tenuigenin treatment decreases secretion of the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid β-protein in cultured cells. Neuroscience Letters. 2004;367(1):123–128. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.05.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li C, Yang J, Yu S, et al. Triterpenoid saponins with neuroprotective effects from the roots of Polygala tenuifolia . Planta Medica. 2008;74(2):133–141. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1034296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karakida F, Ikeya Y, Tsunakawa M, et al. Cerebral protective and cognition-improving effects of sinapic acid in rodents. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2007;30(3):514–519. doi: 10.1248/bpb.30.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dhingra D, Parle M, Kulkarni SK. Memory enhancing activity of Glycyrrhiza glabra in mice. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2004;91(2-3):361–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parle M, Dhingra D, Kulkarni SK. Memory-strengthening activity of Glycyrrhiza glabra in exteroceptive and interoceptive behavioral models. Journal of Medicinal Food. 2004;7(4):462–466. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2004.7.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ahn J, Um M, Choi W, Kim S, Ha T. Protective effects of Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. on the cognitive deficits caused by β-amyloid peptide 25–35 in young mice. Biogerontology. 2006;7(4):239–247. doi: 10.1007/s10522-006-9023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dhingra D, Parle M, Kulkarni SK. Comparative brain cholinesterase-inhibiting activity of Glycyrrhiza glabra, Myristica fragrans, ascorbic acid, metrifonate in mice. Journal of Medicinal Food. 2006;9(2):281–283. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2006.9.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hwang IK, Lim SS, Choi KH, et al. Neuroprotective effects of roasted licorice, not raw form, on neuronal injury in gerbil hippocampus after transient forebrain ischemia. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2006;27(8):959–965. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu RT, Zou LB, Fu JY, Lu QJ. Effects of liquiritigenin treatment on the learning and memory deficits induced by amyloid β-peptide (25–35) in rats. Behavioural Brain Research. 2010;210(1):24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhan C, Yang J. Protective effects of isoliquiritigenin in transient middle cerebral artery occlusion-induced focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Pharmacological Research. 2006;53(3):303–309. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cui YM, Ao MZ, Li W, Yu LJ. Effect of glabridin from Glycyrrhiza glabra on learning and memory in mice. Planta Medica. 2008;74(4):377–380. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1034319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yu XQ, Xue CC, Zhou ZW, et al. in vitro and in vivo neuroprotective effect and mechanisms of glabridin, a major active isoflavan from Glycyrrhiza glabra (licorice) Life Sciences. 2008;82(1-2):68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hillerns PI, Zu Y, Fu YJ, Wink M. Binding of phytoestrogens to rat uterine estrogen receptors and human sex hormone-binding globulins. Zeitschrift fur Naturforschung, Section C. 2005;60(7-8):649–656. doi: 10.1515/znc-2005-7-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tamir S, Eizenberg M, Somjen D, Izrael S, Vaya J. Estrogen-like activity of glabrene and other constituents isolated from licorice root. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2001;78(3):291–298. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(01)00093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Somjen D, Knoll E, Vaya J, Stern N, Tamir S. Estrogen-like activity of licorice root constituents: glabridin and glabrene, in vascular tissues in vitro and in vivo . Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2004;91(3):147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hsich MT, Lin YT, Lin YH, Wu CR. Radix Angelica sinensis extracts ameliorate scopolamine- and cycloheximide-induced amnesia, but not p-chloroamphetamine-induced amnesia in rats. American Journal of Chinese Medicine. 2000;28(2):263–272. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X00000313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huang SH, Lin CM, Chiang BH. Protective effects of Angelica sinensis extract on amyloid β-peptide-induced neurotoxicity. Phytomedicine. 2008;15(9):710–721. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Circosta C, De Pasquale R, Palumbo DR, Samperi S, Occhiuto F. Estrogenic activity of standardized extract of Angelica sinensis . Phytotherapy Research. 2006;20(8):665–669. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lau CBS, Ho TCY, Chan TWL, Kim SCF. Use of dong quai (Angelica sinensis) to treat peri- or postmenopausal symptoms in women with breast cancer: is it appropriate? Menopause. 2005;12(6):734–740. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000184419.65943.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mamiya T, Kise M, Morikawa K. Ferulic acid attenuated cognitive deficits and increase in carbonyl proteins induced by buthionine-sulfoximine in mice. Neuroscience Letters. 2008;430(2):115–118. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim MJ, Choi SJ, Lim S-T, et al. Ferulic acid supplementation prevents trimethyltin-induced cognitive deficits in mice. Bioscience, Biotechnology and Biochemistry. 2007;71(4):1063–1068. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yu L, Zhang Y, Ma R, Bao L, Fang J, Yu T. Potent protection of ferulic acid against excitotoxic effects of maternal intragastric administration of monosodium glutamate at a late stage of pregnancy on developing mouse fetal brain. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;16(3):170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yan JJ, Cho JY, Kim HS, et al. Protection against β-amyloid peptide toxicity in vivo with long-term administration of ferulic acid. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2001;133(1):89–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hsieh MT, Tsai FH, Lin YC, Wang WH, Wu CR. Effects of ferulic acid on the impairment of inhibitory avoidance performance in rats. Planta Medica. 2002;68(8):754–756. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-33800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kuang X, Du JR, Liu YX, Zhang GY, Peng HY. Postischemic administration of Z-Ligustilide ameliorates cognitive dysfunction and brain damage induced by permanent forebrain ischemia in rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2008;88(3):213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Peng HY, Du JR, Zhang GY, et al. Neuroprotective effect of Z-Ligustilide against permanent focal ischemic damage in rats. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2007;30(2):309–312. doi: 10.1248/bpb.30.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kuang X, Yao Y, Du JR, Liu YX, Wang CY, Qian ZM. Neuroprotective role of Z-ligustilide against forebrain ischemic injury in ICR mice. Brain Research. 2006;1102(1):145–153. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.04.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ho CC, Kumaran A, Hwang LS. Bio-assay guided isolation and identification of anti-Alzheimer active compounds from the root of Angelica sinensis . Food Chemistry. 2009;114(1):246–252. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cui Y, Yan Z, Hou S, Chang Z. Effect of radix Rehmanniae preparata on the expression of c-fos and NGF in hippocampi and learning and memory in rats with damaged thalamic arcuate nucleus. Zhong Yao Cai. 2004;27(8):589–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yu H, Oh-Hashi K, Tanaka T, et al. Rehmannia glutinosa induces glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor gene expression in astroglial cells via cPKC and ERK1/2 pathways independently. Pharmacological Research. 2006;54(1):39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2006.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cui Y, Yan ZH, Hou SL, Chang ZF. Effect of Shu Di-huang on the transmitter and receptor of amino acid in brain and learning and memory of dementia model. Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi. 2003;28(9):862–866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhang A, Hao S, Bi J, et al. Effects of catalpol on mitochondrial function and working memory in mice after lipopolysaccharide-induced acute systemic inflammation. Experimental and Toxicologic Pathology. 2009;61(5):461–469. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang X, Zhang A, Jiang B, Bao Y, Wang J, An L. Further pharmacological evidence of the neuroprotective effect of catalpol from Rehmannia glutinosa . Phytomedicine. 2008;15(6-7):484–490. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang XL, An LJ, Bao YM, Wang JY, Jiang B. d-galactose administration induces memory loss and energy metabolism disturbance in mice: protective effects of catalpol. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2008;46(8):2888–2894. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhang XL, Jiang B, Li ZB, Hao S, An LJ. Catalpol ameliorates cognition deficits and attenuates oxidative damage in the brain of senescent mice induced by d-galactose. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2007;88(1):64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li DQ, Duan YL, Bao YM, Liu CP, Liu Y, An LJ. Neuroprotection of catalpol in transient global ischemia in gerbils. Neuroscience Research. 2004;50(2):169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Li DQ, Li Y, Liu Y, Bao YM, Hu B, An LJ. Catalpol prevents the loss of CA1 hippocampal neurons and reduces working errors in gerbils after ischemia-reperfusion injury. Toxicon. 2005;46(8):845–851. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Li DQ, Bao YM, Li Y, Wang CF, Liu Y, An LJ. Catalpol modulates the expressions of Bcl-2 and Bax and attenuates apoptosis in gerbils after ischemic injury. Brain Research. 2006;1115(1):179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.07.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Liu J, He QJ, Zou W, et al. Catalpol increases hippocampal neuroplasticity and up-regulates PKC and BDNF in the aged rats. Brain Research. 2006;1123(1):68–79. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bi J, Wang XB, Chen L, et al. Catalpol protects mesencephalic neurons against MPTP induced neurotoxicity via attenuation of mitochondrial dysfunction and MAO-B activity. Toxicology in Vitro. 2008;22(8):1883–1889. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jiang B, Du J, Liu JH, Bao YM, An LJ. Catalpol attenuates the neurotoxicity induced by β-amyloid (1-42) in cortical neuron-glia cultures. Brain Research. 2008;1188(1):139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.07.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wan D, Zhu HF, Luo Y, Xie P, Xu XY. Study of catalpol promoting axonal growth for cultured cortical neurons from rats. Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi. 2007;32(17):1771–1774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wang Z, An LJ, Duan YL, Li YC, Jiang B. Catalpol protects rat pheochromocytoma cells against oxygen and glucose deprivation-induced injury. Neurological Research. 2008;30(1):106–112. doi: 10.1179/016164107X229894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jiang B, Liu JH, Bao YM, An LJ. Catalpol inhibits apoptosis in hydrogen peroxide-induced PC12 cells by preventing cytochrome c release and inactivating of caspase cascade. Toxicon. 2004;43(1):53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2003.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bi J, Jiang B, Liu JH, Lei C, Zhang XL, An LJ. Protective effects of catalpol against H2O2-induced oxidative stress in astrocytes primary cultures. Neuroscience Letters. 2008;442(3):224–227. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Li Y, Bao Y, Jiang B, et al. Catalpol protects primary cultured astrocytes from in vitro ischemia-induced damage. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 2008;26(3-4):309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Miao YC, Tian JZ, Shi J, et al. Correlation between cognitive functions and syndromes of traditional Chinese medicine in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Bao. 2009;7(3):205–211. doi: 10.3736/jcim20090302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Giménez BG, Santos MS, Ferrarini M, Fernandes JP. Evaluation of blockbuster drugs under the rule-of-five. Pharmazie. 2010;65(2):148–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Boultadakis A, Liakos P, Pitsikas N. The nitric oxide-releasing derivative of ferulic acid NCX 2057 antagonized delay-dependent and scopolamine-induced performance deficits in a recognition memory task in the rat. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2010;34(1):5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]