Abstract

Objectives

The purposes of this article are: (1) to systematically examine racial disparities in access to and use of cardiac care units (CCUs) in acute-care hospitals; and (2) to assess racial differences in post-hospital mortality following CCU stays.

Design

Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I: Epidemiologic Follow-up Study of adults aged 25 and older at baseline are analyzed to track CCU use and survival after hospitalization over 20 years (N=4227). Estimates are derived from Cox proportional-hazards models with time-dependent covariates and from negative binomial and tobit regression analyses. All analyses adjust for disease severity, hospitalization history, and resources.

Results

Black adults were less likely than White adults to be admitted to a CCU, even after adjusting for morbidities, health behaviors, previous hospitalization experience, and socioeconomic status. Comparing Black and White adults admitted to CCUs, Black adults spent fewer days and a smaller proportion of their hospital stay in CCUs. Black adults also had fewer CCU stays over the 20-year period and were more likely to die post-discharge, although the latter result was mediated by disease severity.

Conclusions

Higher morbidity, lower admission rates, fewer stays, and shorter stays reveal that racial inequality is far-reaching and exists even in such highly-specialized units as CCUs. The fact that Black individuals’ greater post-discharge mortality was mediated by disease severity illustrated that even among high-risk individuals, the accumulation of morbidity factors (beyond cardiac problems) is a salient concern. Overall findings demonstrate that the accumulation of disadvantage for Black adults is not confined to discretionary medical measures, but also exists in critical care for serious health problems.

Keywords: racial disparities, health care access, cardiac care, prospective cohort study

Introduction

Heart disease remains a major cause of death worldwide, especially in developed nations, but proper treatment can substantially reduce comorbidity and premature mortality. In large complex societies, health disparities emerge such that disadvantaged groups face a higher prevalence of disease and greater risks associated with a given condition. For example, the age-adjusted prevalence of cardiovascular disease is substantially higher for African American (hereafter Black) than for White adults, and Black adults are more likely than White adults to die prematurely from it (Rosamond et al. 2008).

Many factors contribute to the racial disparity in cardiovascular mortality in the USA, and access to cardiac intensive care units (ICUs) in hospitals is one of the major contributing factors (Lillie-Blanton et al. 2002). Although one might not expect racial differences in access to cardiac care units (CCUs) due to their highly specialized nature, Black persons are less likely than White individuals to undergo invasive, diagnostic, or therapeutic cardiac procedures (Ford et al. 2000, Lillie-Blanton et al. 2002, LaVeist et al. 2003). Explaining these racial disparities in cardiac care is an issue of high priority (Smedley et al. 2003), especially because they do not appear to reflect patient preferences (Kressin et al. 2004). Prior research has documented racial disparities in cardiac procedures among those already admitted to CCUs, but less attention has been given to studying disparities in CCU access. Are Black adults less likely than White adults to be admitted to a CCU? Do these disparities affect post-discharge mortality? This study addresses these questions by using a prospective, population-based national sample spanning 20 years of observation.

Conceptual framework

Two conceptual frameworks are useful for the present investigation of racial disparities. First, the inverse care law has long been identified to describe the pervasive nature of disparities: people with the greatest needs are frequently the ones who receive the least – or least adequate – care (Hart 1971). The emphasis of the inverse care law is on the recurrent inequality for disadvantaged members of a society; early disadvantage leads to a cascade of problems, which is quite similar to the thrust of cumulative disadvantage theory (Dannefer 2003). For Black adults, the inverse care law means that limited access and lower utilization of medical care may accelerate health problems (Mayberry et al. 1999, Smedley et al. 2003, D’Anna et al. 2010). Thus, Black adults generally face worse health and less access to care (National Center for Health Statistics 2006).

An alternative explanation may be referred to as the response to unmet need. There is a clear acknowledgment of how disadvantaged groups may indeed have greater needs due to a lack of early access, but the question is whether medical care services address these needs at a later point, even if in a sub-optimal way. Identifying responses to unmet (or pent-up) need requires more than examining racial differences in admission; assessment should cover the gamut of system responses, from admission to post-hospitalization mortality. Minority persons generally have lower rates of primary care use and hospital admission than White individuals (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 2003, Ferraro et al. 2006) and are more likely to be hospitalized for preventable causes (Laditka and Laditka 2006). Further down the stream of care, however, this may actually result in longer hospital stays than for White adults – albeit for a select minority population (Shi 1996, Ferraro and Shippee 2008). Whether this phenomenon extends to CCUs has not been determined, but system response – a vital injection of health resources – is an important public policy issue in addressing disparities in health care.

More generally, the conceptual frameworks differ in how far disadvantage accumulates. Are inequalities established early and set in motion over the life course or can resources and use of medical care alter the trajectory of early disadvantage? This question is given priority in cumulative inequality theory, which posits that structural inequity influences life trajectories but that the distribution of risks and resources may interrupt the cascade of disadvantage (Ferraro et al. 2009). For the present analysis, we assume that disadvantage due to minority status increases health risks while reducing access to resources. The net result is that early inequalities are likely amplified in later life unless resources are mobilized to compensate for greater risk exposure. This paper asks whether life trajectories are modifiable when exposed to early disadvantage. Can CCUs soften the blow of long-term disadvantage or are they simply another vehicle for exacerbating inequality?

Cardiac care unit (CCU) as a critical research site

In developed nations, a serious illness or injury may result in admission to a critical care unit, frequently referred to as an ICU (Society of Critical Care Medicine 2009). The CCU (or cardiac ICU) is one of the more common specialized units and provides care primarily for patients admitted for heart disease. Heart attack, angina, congestive heart failure, and arrhythmia are the most common reasons for CCU admission (Society of Critical Care Medicine 2009). In many respects, CCUs serve as a critical last line of defense in heart health and recovery; consequently, racial disparities in admission and treatment are of great concern. Furthermore, if one seeks to identify system response to pent-up need, CCUs represent one of the downstream sites where evidence may be located.

There are also selection processes that may influence the extent of racial disparities in CCU use. Admission to CCUs is limited to acute cardiac cases and Black adults have a higher rate of sudden cardiac death prior to hospitalization (Gillum 1997). This means that racial disparities may be less than one would expect based on the inverse care law and perhaps attributable to health condition and resources than to race per se. Indeed, some studies find no evidence of racial disparities in cardiac care after adjusting for insurance status, comorbidity, disease severity, and other potential confounders (Carlisle et al. 1997, Leape et al. 1999). Failure by some studies to adequately control for these additional variables led Klick and Satel (2006) to assert that racial disparities in health care are a myth, and that treatment bias by medical personnel is negligible or non-existent. We agree that adjustment for these controls is essential, but assert that racial differences in the pathways to CCU care merit further study to accurately gauge inequality. Moreover, intentional bias by medical personnel may be rare, but racial disparities can also result from institutional forms of bias (Williams and Rucker 2000, Krieger 2003).

Prior research and contributions

Many previous studies of Black/White differences in CCU use are compelling but limited for addressing the range of outcomes considered here. Most studies focus on the receipt of specific cardiac care procedures rather than admission to and duration in CCUs or ICUs (Lillie-Blanton et al. 2002). Among those analyses that do consider admission as an outcome, many do not include race (Rosenthal et al. 1998, Miller et al. 2000). This is partially due to the fact that information on race is limited or non-existent in hospital and Medicare data (Hasnain-Wynia et al. 2004, Kawachi et al. 2005).

Among the studies that have examined racial differences, Williams et al. (1995) found that Black patients generally had shorter stays and utilized fewer resources in comparison to White patients. These differences persisted after adjusting for patient characteristics and insurance status, suggesting ‘undertreatment’ for Black patients (or overtreatment for White patients). This finding is important and intriguing, but Williams and colleagues focused on all-cause admission to ICUs, which entails a substantial case mix. Such heterogeneity may affect the outcome measures in ways that obscure Black/White differences. The present study confronts the case-mix concern by focusing on admission, number of stays, and duration of stay in a CCU for a condition that is a leading cause of death: heart disease.

The present study is also distinctive in other respects. Specifically, we employ analyses of longitudinal data in order to analyze the processes leading to disparities in access to and use of CCUs. Long-term panel studies, such as used here, offer opportunities to study multiple admissions in a life course framework (Kuh and Ben-Shlomo 1997). Moreover, with actual admission dates, we can identify the timing of CCU admission in each subject’s life.

Additionally, rather than analyze hospitalized persons only, a common practice in many previous studies, this investigation prospectively examines racial differences in CCU admission and duration of stay, as well as survival after hospitalization. This allows, on the one hand, for an investigation of racial selectivity in admissions – both CCU and non-CCU admissions – as a key mechanism in the accumulation of racial disparities over time. On the other hand, it also provides an opportunity to study mortality as a longer-term outcome of cumulative inequality. Research in this latter area is inconsistent: some studies find that Black adults have higher post-hospital mortality following heart-related procedures (Groeneveld et al. 2003), whereas other studies show no racial differences (Kamalesh et al. 2005).

Finally, many previous studies of CCU length of stay aggregate across stays to create a summary stay measure. By contrast, we explore whether first CCU admissions are distinct from subsequent ones. This also enables us to identify the role of non-CCU admissions on the likelihood of CCU admission.

We address three research questions.

-

Are Black adults less likely to be admitted to the CCU during the 20-year period?

Despite Black/White differences in risk exposure and morbidity, we anticipate a lower rate of admission for Black adults. When answering this research question, the analyses (a) adjust for morbidity, socioeconomic status (SES), and receipt of heart-related procedures; and (b) distinguish first from subsequent CCU admissions. In addition, we examine the timing of the first admission and total number of CCU admissions.

-

Once admitted to the CCU, do Black adults have shorter stays than White adults?

Given the competing expectations described above (inverse care law and response to unmet need), we do not advance an hypothesis. Beyond the simple duration of each stay, we also examine whether the ratio of the days spent in the CCU in relation to the total days for the stay is smaller for Black adults than for White adults. We interpret high values on this ratio to reflect more aggressive and sustained care, especially after adjusting for comorbidity.

-

Is post-hospital survival shorter for Black adults compared to White adults?

Given the accumulation of health-related disadvantages for Black adults over the life course, we expect that Black adults will die at younger ages after the CCU stay compared to their White counterparts.

Methods

Sample

Data are from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I (NHANES I) and its Epidemiologic Follow-up Study (NHEFS) for those participants who were given the ‘detailed component’ of the interview, including the Health Care Needs Questionnaire at baseline (1971–1975) and the medical examination. The baseline NHANES I is a multi-stage stratified probability sample of non-institutionalized Americans ages 24–75 years at baseline. The subjects were followed-up with three additional interviews: the second (Wave 2) conducted between 1982 and 1984; the third in 1987 (Wave 3), and the fourth in 1992 (Wave 4).

Measurement of hospitalization

At each NHEFS follow-up, respondents or proxies were asked if the subject had any overnight hospitalizations since the previous interview. Participants provided data on length of stay, reason for stay, and approximate date. After gaining consent from the respondent (or proxy respondent), researchers attempted to match the reported stays with hospital records. A reported stay was categorized as a match only if the reason given for the hospitalization was consistent with facility records (e.g., subject admitted for myocardial infarction, and subject reported hospitalized for heart attack). The use of proxy respondents allowed deceased and impaired subjects to be included in the matching process. NHEFS identified 2604 stays from proxy interviews for deceased respondents.

Hospital stays that were reported by the respondent but could not be confirmed or matched with facility records were eliminated from the analyses. Most of the discrepancy between respondent reports and hospital records lies with the respondent or proxy reports of frequent hospitalizations. For instance, one NHEFS respondent reported 50 stays, but only 47 hospital records were matched. There are relatively few cases with 10 or more stays (90% of the NHEFS sample reported seven or fewer stays). Even among the persons with a large number of hospital stays, the discrepancy is most often one or two stays. Indeed, 90.2% of all reports from respondents were accurate within one visit and 95.5% within two visits. Accounting for all discrepancies in the record-linkage process, there are matched records for 77% of all self- or proxy-reported hospital stays. Racial differences in the likelihood of a matching record for each reported hospitalization were examined, but no significant differences were observed.

Recorded hospital stays provided information on date of admission, date of discharge, discharge destination, and diagnosis (based on the International Classification of Diseases [ICD]-9 codes; National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 2007). Hospitalizations for childbirth, mental health facility stays, and nursing home stays were excluded from the analyses. Overall, 15,281 hospitalizations were confirmed for 4229 persons over 20 years. The sample was composed of 3737 White and 492 Black respondents at baseline. Of those, about 19% had a CCU stay during the 20-year period (15% Black and 19% White). The locations of hospitals were not identified in the data set. All analyses presented below are adjusted for weighting and clustering in the complex sample design using Stata 10.0 (StataCorp 2008).

Measurement of outcome variables

Admission to CCU was measured using two variables: admission to CCU during first hospitalization and admission to CCU during any hospitalization within the 20-year period. Each of the admission variables consists of two components: a dichotomous variable regarding whether the respondent had ever had a CCU stay and a duration variable of the number of days from enrollment in the study until a CCU stay.

Number of CCU stays is a count variable that reflects the number of CCU stays for each respondent.

Number of CCU days is a count of number of days in a CCU for each stay. This variable was created for CCU stay during first hospitalization (number of days for first stay) and a CCU stay during any hospitalization within 20 years (number of days for a particular hospitalization).1

Ratio of CCU days to total days during the first stay was measured by dividing the number of days spent in a CCU during their first hospital stay by the total days (CCU plus non-CCU) spent in the hospital during the same admission.

Post-hospital mortality

Mortality data were collected from brief interviews conducted with proxies of deceased respondents. In addition, matches were made for all participants in the baseline survey to the National Death Index, the Social Security AdmFinistration Mortality File, and the enrollment file of the Health Care Financing Administration. To study racial differences in age at death, we created a binary vital-status variable (0, 1) and a duration variable that refers to the number of days from last discharge to death or to the final interview (persons who died in the hospital were assigned a duration score of 0.1).

Measurement of covariates

Demographic variables included race, gender, and age. Black and female are binary variables (scored with 1 equal to the name of the variable, 0 otherwise). (No other racial or ethnic group identified appeared in numbers sufficient for statistical analysis; thus, the analysis examines Black/White differences only.) Age was coded in years reported at the baseline survey, ranging from 24 to 75.

Variables for SES included education (seven categories, with 0 equal to less than 8 years of schooling and seven representing a post-college education), household income (12 categories, 1 equal to less than $1000 and 12 greater than $25,000), Medicaid status, private health insurance, and regular physician (from whom the subject regularly received care).

To account for treatment differences that may affect stay duration, we also included a measure of receiving heart-related procedures when hospitalized (1 = yes; 0 = otherwise). The measure was developed from the ICD-9 procedure codes, with codes 350.1–379.9 categorized as heart-related.

To account for hospitalizations prior to the start of the study (i.e., left censoring), we included a variable that represents an urgent hospitalization prior to the baseline survey. Recent emergency hospitalization was a self-reported measure of whether an emergency hospitalization occurred within the last year. It was coded as a binary variable (1 = yes; 0 = otherwise).

Morbidity measures included self-reported conditions and the Charlson comoribity index. Self-reported measures were derived from a checklist administered at each survey and based on the following question: ‘Has a doctor ever told you that you have: “cancer”, … “diabetes”, … etc’. Each condition was coded as a binary variable including cancer, diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, kidney disorder, and hipfracture.

The Charlson index was measured for each hospital episode and is used to differentiate low- and high-risk morbidity among hospital patients. Researchers have used ICD diagnosis codes in a modified version of the index to study outcomes of medical care (Goldstein et al. 2004). Following this procedure, we use the 10 possible available diagnoses in the data and give each diagnosis its appropriate score.2 Each respondent’s score was summed to provide a Charlson comorbidity indicator for their first stay. Higher scores reflect more serious morbidity.

Health-related factors included a number of lifestyle indicators known to be related to health, such as heavy drinking, smoking (in the past and in the present), and obesity. Heavy drinkers were defined as those who averaged 14 or more drinks per week. Smokers were identified by self-reported consumption of cigarettes, cigars, and pipe tobacco at the time of the interview. Past smokers were defined as those who reported ever smoking cigars, pipes, or at least 100 cigarettes but no longer smoked. Obesity was defined as body mass index greater than or equal to 30 (kilograms/meters2) according to National Health Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) guidelines (NHLBI Obesity Education Initiative Expert Panel 1998). Finally, for selected analyses we account for the influence of prior hospitalizations by identifying whether a respondent had a hospital stay prior to a CCU stay (1 = yes, 0 = no) and number of hospital stays (1–78).

Analytic strategy

The analysis was divided into three main stages. First, we used Cox proportional-hazards models to examine racial differences in CCU admission during first hospitalization, estimated for the total sample and by race (Cleves et al. 2004). To account for changing health status during the 20-year observation period, we used time-dependent covariates for serious illnesses (cancer, diabetes, heart disease, and hypertension). To further explore racial differences in admission to CCU, we estimated racial differences in the total number of CCU stays. Since the number of CCU days was a count variable with a skewed distribution, we used negative binomial regression models that are appropriate for overdispersed count data (Long 1997). Also, we used ordered logistic regression to estimate predicted probabilities by race of zero, one, or two CCU stays.

Second, to examine racial differences in days spent in a CCU, we utilized negative binomial regression models to predict CCU days during one’s first hospitalization (Long 1997); these models were estimated for the total sample and by race, adjusting for all covariates. Interval regression was used for the ratio of days spent in the CCU to total days during first hospitalization. Interval regression is a derivation of tobit regression, which accounts for censoring of the dependent variable’s distribution (Hardin 2005). It is suitable for ratio variables and can also account for the complex sample design (StataCorp 2008). We also examined racial differences in the number of CCU stays over the entire study duration.

Finally, with information on the exact date of discharge and date of death, Black/White differences in age at death were estimated with Cox proportional-hazards models (Cleves et al. 2004). These analyses make use of Charlson comorbidity index for each hospital episode. The analyses presented below are for all-cause mortality and are conducted for the hazard of dying after the first CCU stay. Supplemental analyses were also explored with the subsequent stays, but we found that statistical power was not sufficient for testing racial differences.

Results

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics for the total sample and by race. Black adults had a relative risk of CCU admission during their first hospital stay that was about 31% less than for White adults, despite their higher prevalence of heart-disease and hypertension. Also, Black adults were less likely to ever have a CCU stay during the 20-year period compared to White adults (15% vs. 19%, respectively). Once admitted, Black adults had a significantly shorter stay in a CCU during their first hospitalization compared to White adults (0.13 vs. 0.29 days; p<0.05). Black adults also spent a significantly shorter portion of their time in a CCU during first hospitalization relative to their total first stay compared to their White counterparts (2% vs. 4%; p<0.05). Similarly, Black adults had fewer CCU stays, averaging 0.238 stays while White adults had 0.308 stays.

Table 1.

Means and standaxrd deviations of variables by race, National health and nutrition examination Survey I: epidemiologic follow-up study.

| Dependent variables | Range | Total | Black | White |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Had CCU stay during first hospital stay | 0–1 | 0.077a,b | 0.055 | 0.080*c |

| Days until first hospital stay | 21–8021 | 5919.845 (1749.209) | 5585.158 (2037.568) | 5961.529*** (1705.629) |

| CCU days during first hospitalization | 0–70 | 0.274 (1.647) | 0.133 (.718) | 0.292* (1.731) |

| Ratio of CCU days during first stay/total days for first stay | 0–1 | 0.035 | 0.020 | 0.037* |

| Number of CCU stays | 0–13 | 0.30 (0.821) | 0.238 (0.747) | 0.308** (0.830) |

| Days alive post-discharge | 0.1–7771 | 2320.96 (2175.08) | 1929.631 (2084.301) | 2372.537*** (2181.801) |

| Independent variables | ||||

| Status characteristics and resources | ||||

| Black | 0–1 | 0.116 | ||

| Age | 24–75 | 50.989 (13.829) | 51.152 (14.149) | 50.968 (13.789) |

| Female | 0–1 | 0.536 | 0.546 | 0.535 |

| Education | 0–7 | 3.586 (1.551) | 2.886 (1.597) | 3.677*** (1.521) |

| Income | 1–12 | 7.550 (2.762) | 5.943 (2.986) | 7.762*** (2.660) |

| Medicaid | 0–1 | 0.035 | 0.093 | 0.027*** |

| Private insurance | 0–1 | 0.854 | 0.699 | 0.874*** |

| Regular physician | 0–1 | 0.877 | 0.796 | 0.887*** |

| Heart-related procedures | 0–1 | 0.049 | 0.045 | 0.049 |

| Recent emergency hospitalization | 0–1 | 0.326 | 0.319 | 0.327 |

| Rural | 0–1 | 0.432 | 0.290 | 0.451*** |

| Morbidity | ||||

| Cancer | 0–1 | 0.028 | 0.016 | 0.030** |

| Diabetes | 0–1 | 0.061 | 0.099 | 0.056*** |

| Heart disease | 0–1 | 0.086 | 0.128 | 0.080*** |

| Hypertension | 0–1 | 0.259 | 0.371 | 0.245*** |

| Kidney | 0–1 | 0.025 | 0.034 | 0.024 |

| Hip fracture | 0–1 | 0.009 | 0.002 | 0.010 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 0–6 | 0.442 (0.855) | 0.667 (1.057) | 0.413*** (0.821) |

| Health related factors | ||||

| Heavy drinker | 0–1 | 0.119 | 0.096 | 0.123* |

| Current smoker | 0–1 | 0.424 | 0.516 | 0.397*** |

| Past smoker | 0–1 | 0.249 | 0.180 | 0.278*** |

| Obese | 0–1 | 0.258 | 0.327 | 0.249*** |

| Hospitalization experience | ||||

| Hospital stay prior to CCU | 0–1 | 0.108 | 0.098 | 0.110 |

| Number of hospital stays | 1–78 | 3.612 (3.795) | 3.485 (3.452) | 3.629 (3.837) |

| N | 4229 | 492 | 3737 | |

Notes: Results are weighted and adjusted for clustering using Stata 10.0. Significance tests for categorical variables are based on the Pearson χ2-statistic; tests for continuous variables are based on the t-statistic.

Mean (Standard deviation).

The standard deviations of dichotomous variables are omitted because they are a function of the mean. All dichotomous variables are scored zero and one (0 = no or otherwise).

Statistical significance between the Black and White subsamples.

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001.

As expected, status resources differed between the Black and White respondents. Education and income differences were substantial, and Black adults were more likely than White adults to be receiving Medicaid and less likely to have private insurance and attend a regular physician. Black persons were significantly less likely than White persons to reside in rural areas but had more comorbidities upon admission. Also, importantly, Black adults compared to White adults were significantly more likely to have heart disease (13% vs. 8%, respectively) and hypertension (37% vs. 25%, respectively) upon admission. Black adults were also more likely to be obese and smokers.

Table 2 displays the significant predictors of the likelihood of being admitted to a CCU during first hospitalization, accounting for time-dependent covariates for serious health conditions (cancer, diabetes, heart disease, and hypertension). For the total sample, Black adults were less likely than White adults to be admitted to a CCU (HR = 0.43, 95% CI: 0.221–0.846). In addition, persons more likely to be admitted were older, without private insurance, had a recent emergency hospitalization, hypertensive, without kidney problems, and either current or past smokers.

Table 2.

Event history analysis for admission to cardiac intensive care unit among hospitalized respondents: National health and nutrition examination Survey I: epidemiologic follow-up study.

| Total | Black | White | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Black | 0.433*a (0.221–0.846)b | ||

| Age | 1.057*** (1.043–1.072) | 1.025 (0.925–1.135) | 1.061*** (1.046–1.074) |

| Private insurance | 0.626** (0.446–0.878) | 1.135 (0.431–2.993) | 0.587*** (0.450–0.766) |

| Recent emergency hospitalization | 1.269*** (1.101–1.464) | 0.330 (0.044–2.471) | 1.368***c (1.219–1.535) |

| Hypertension | 1.386** (1.081–1.777) | 0.332 (0.022–5.103) | 1.454*** (1.094–1.932) |

| Kidney | 0.428*** (0.298–0.626) | d | 0.421*** (0.297–0.597) |

| Current smoker | 1.771*** (1.235–2.497) | 0.276 (0.070–1.092) | 1.862***c (1.282–2.706) |

| Past smoker | 1.262* (1.012–1.574) | 0.718 (0.268–1.923) | 1.236** (1.025–1.491) |

| Wald χ2 | 1886.94 | 4084.46 | 1775.36 |

| df | 21 | 17 | 20 |

| N | 3988 | 437 | 3551 |

Note: Analyses also control for sex, education, income, Medicaid, regular physician, rural residence, cancer, diabetes, heart disease, hip fracture, heavy drinking, and obesity. These variables were not significant predictors of mortality and are omitted from the table for concise presentation.

Hazard ratios.

Confidence intervals.

t-Test indicates coefficients are significantly different for Black and White subjects.

Estimates could not be generated due to insufficient number of Black respondents with kidney trouble.

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001.

Among Black adults, regular physician and heart-related procedures upon hospitalization were significant predictors after implementing time-dependent covariates for morbidity. For White adults, the pattern of findings was similar to those for the total sample.

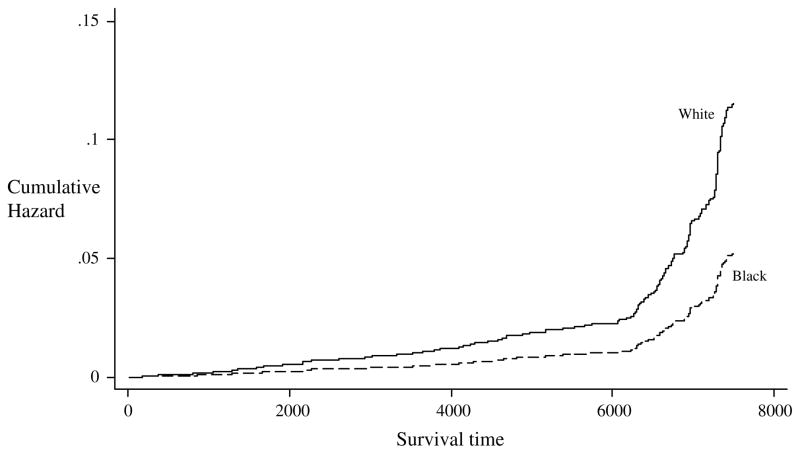

The cumulative hazard in the likelihood of a CCU admission increased over time and is displayed graphically in Figure 1. Even after controlling for incident morbidity and socioeconomic characteristics, Black persons were less likely than White persons to be admitted to a CCU.3

Figure 1.

Adjusted likelihood of admission to cardiac intensive care unit for 3988 hospitalized Black and White adults (controlling for all predictors).

Table 3 presents multivariate analyses for number of CCU days during the first hospitalization and the ratio of days in the CCU relative to the overall number of days during the first hospitalization. Black adults had significantly shorter stays compared to their White counterparts (IRR = 0.333, 95% CI 0.22–0.51) = about 67% lower after adjusting for other variables, including Charlson comorbidity index. Older adults, men, those not on Medicaid, those who had heart-related procedures, those with heart-related conditions and diabetes, with greater comorbidity, and current smokers had longer CCU stays. Similar predictors were observed in sub-sample analysis by race, with several exceptions. Note that Black adults had shorter stays if they reported lower income, were on Medicaid, did not have a physician, or if they were past smokers.

Table 3.

Parameter estimates for number of CCU days and ratio of CCU days during first stay for Black and White adults: National health and nutrition examination Survey I: epidemiologic follow-up study.

| Number of CCU days

|

First CCU stay/first general stay

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Black | White | Total | Black | White | |

| Black | 0.288***a (0.190–0.436) | −0.392***b (0.087) | ||||

| Age | 1.045*** (1.030–1.060) | 1.065*** (1.020–1.111) | 1.043*** (1.027–1.060) | 0.013*** (0.003) | 0.022** (0.010) | 0.013*** (0.003) |

| Female | 0.347*** (0.250–0.483) | 0.078** (0.011–0.546) | 0.375***c (0.271–0.519) | −0.325*** (0.059) | −0.680*** (0.175) | −0.304***c (0.054) |

| Education | 0.994 (0.913–1.081) | 1.002 (0.547–1.835) | 0.997 (0.925–1.075) | −0.001 (0.014) | 0.082 (0.075) | −0.003 (0.013) |

| Income | 0.997 (0.893–1.114) | 0.798* (0.636–1.002) | 0.995 (0.900–1.099) | −0.005 (0.012) | −0.068 (0.045) | −0.003 (0.010) |

| Medicaid | 0.217*** (0.078–0.608) | 0.000*** (0.000–0.000) | 0.254**c (0.079–0.821) | −0.397* (0.206) | −4.721*** (0.458) | −0.337c (0.227) |

| Private insurance | 0.696** (0.515–0.941) | 1.056 (0.382–2.920) | 0.676** (0.485–0.942) | −0.041 (0.033) | −0.074 (0.159) | −0.041 (0.048) |

| Regular physician visits | 1.540** (1.089–2.179) | 8.999*** (2.679–30.227) | 1.399*c (0.968–2.023) | 0.140** (0.060) | 0.849*** (0.312) | 0.105*c (0.064) |

| Heart-related procedures | 7.123*** (5.052–10.044) | d | 7.362*** (5.026–10.784) | 0.927*** (0.082) | 0.954*** (0.267) | 0.938*** (0.082) |

| Rural | 1.162 (0.794–1.700) | 0.614 (0.105–3.594) | 1.141 (0.795–1.638) | −0.015 (0.052) | 0.043 (0.188) | −0.021 (0.056) |

| Recent emergency hospitalization | 1.270 (0.828–1.947) | 0.737 (0.300–1.812) | 1.336 (0.892–2.000) | 0.099 (0.078) | 0.013 (0.174) | 0.114 (0.078) |

| Morbidity | ||||||

| Cancer | 0.711 (0.386–1.310) | d | 0.592*c (0.350–1.001) | −0.079 (0.159) | 0.884** (0.417) | −0.159c (0.143) |

| Diabetes | 1.222 (0.820–1.819) | 0.408 (0.123–1.359) | 1.259 (0.829–1.913) | 0.054 (0.131) | −0.053 (0.235) | 0.042 (0.128) |

| Heart disease | 1.351 (0.885–2.061) | 0.739 (0.126–4.343) | 1.413 (0.850–2.347) | 0.297** (0.116) | 0.057 (0.351) | 0.298** (0.133) |

| Hypertension | 1.515** (1.027–2.236) | 2.206* (0.954–5.102) | 1.509** (1.027–2.217) | 0.065 (0.082) | 0.064 (0.156) | 0.068 (0.080) |

| Kidney | 1.341 (0.692–2.598) | 0.000*** (0.000–0.000) | 1.553c (0.855–2.821) | 0.036 (0.145) | −4.380*** (0.789) | 0.084c (0.143) |

| Hip fracture | 1.053 (0.644–1.722) | 0.014*** (0.003–0.075) | 1.045c (0.628–1.739) | 0.300 (0.230) | 0.274 (0.569) | 0.294 (0.231) |

| Comorbidity index | 1.556*** (1.283–1.887) | 1.693*** (1.189–2.409) | 1.535*** (1.188–1.985) | 0.078*** (0.027) | 0.148 (0.092) | 0.074** (0.038) |

| Health related factors | ||||||

| Heavy drinker | 1.284 (0.747–2.206) | 7.972** (1.029–61.773) | 1.148c (0.650–2.025) | 0.046 (0.098) | 0.722*** (0.194) | 0.015c (0.102) |

| Current smoker | 1.663*** (1.347–2.053) | 0.493 (0.064–3.773) | 1.822*** (1.492–2.226) | 0.124* (0.064) | −0.324* (0.183) | 0.155**c (0.061) |

| Past smoker | 1.035 (0.670–1.599) | 0.372** (0.143–0.970) | 1.109c (0.662–1.858) | 0.006 (0.095) | −0.091 (0.199) | 0.019 (0.098) |

| Obese | 1.093 (0.712–1.678) | 1.416 (0.196–10.203) | 1.052 (0.653–1.695) | 0.032 (0.067) | 0.058 (0.298) | 0.036 (0.081) |

| Constant | 0.015*** (0.004–0.059) | 0.002*** (0.000–0.017) | 0.016*** (0.004–0.074) | −2.222*** (0.151) | −3.003*** (0.711) | −2.210*** (0.178) |

| χ2 | 2301.67 | 20092.79 | 2046.66 | 2598.58 | 2583.76 | 2416.83 |

| df | 22 | 21 | 21 | 22 | 21 | 21 |

| N | 4185 | 480 | 3705 | 4181 | 479 | 3702 |

Note: Negative binomial regression is used to estimate the number of CCU days, and interval regression is used to estimate the ratio of CCU days during first stay to total days during first stay.

Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) and confidence intervals are presented for number of CCU days;

Unstandardized coefficients and standard errors are presented for first CCU stay/first general stay;

t-Test indicates coefficients are significantly different for Black and White subjects (p<0.05);

Estimates are not presented due to insufficient number of cases among Black adults.

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001.

Similar patterns were observed in the ratio of CCU days during first hospitalization to days during overall first stay. Black adults, compared to White adults, spent a significantly smaller proportion of time in the CCU during their hospital stay. In addition, older adults, men, those who had a regular physician, and those not on Medicaid spent a larger proportion of their time in the CCU. As expected, adults who had heart-related procedures and greater comorbidity spent more days in a CCU as well as a greater proportion of their time in the CCU.4

Turning to Table 4, the negative binomial regression for number of CCU stays showed that Black adults also had significantly fewer stays over the two decades than did White adults (IRR = 0.626, 95% CI 0.45–0.89). Specifically, the expected count of stays for Black adults was 63% that of White individuals. Older individuals, men, those who had heart-related procedures, those who experienced a recent emergency hospitalization, those with diabetes and heart disease, those with hypertension, those who were current smokers, and those who had a stay prior to CCU were more likely to have more CCU stays.

Table 4.

Negative binomial regression for number of CCU stays for Black and White adults: National health and nutrition examination Survey I: epidemiologic follow-up study.

| Total | Black | White | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Black | 0.626**a(0.445–0.881)b | ||

| Age | 1.025*** (1.016–1.033) | 1.012 (0.992–1.031) | 1.026*** (1.018–1.034) |

| Female | 0.720*** (0.632–0.820) | 0.346* (0.147–0.811) | 0.738***c (0.642–0.847) |

| Regular physician | 1.037 (0.822–1.309) | 1.573* (0.946–2.617) | 0.988c (0.756–1.292) |

| Recent emergency hospitalization | 1.183*** (1.051–1.333) | 1.039 (0.482–2.243) | 1.198*** (1.063–1.350) |

| Morbidity | |||

| Diabetes | 1.543* (1.000–2.382) | 2.305* (1.127–4.714) | 1.443 (0.927–2.245) |

| Heart disease | 1.507* (1.034–2.197) | 1.613 (0.511–5.089) | 1.467* (0.999–2.154) |

| Hypertension | 1.380*** (1.131–1.685) | 1.325 (0.823–2.134) | 1.382*** (1.122–1.702) |

| Kidney | 1.041 (0.773–1.404) | 0.341* (0.137–0.846) | 1.125c (0.852–1.486) |

| Hip fracture | 1.170 (0.623–2.198) | 0.000*** (0.000–0.000) | 1.142c (0.609–2.140) |

| Health related factors | |||

| Current smoker | 1.206** (1.059–1.373) | 0.716 (0.354–1.447) | 1.241*** (1.098–1.404) |

| Hospitalization experience | |||

| Hospital stay prior to CCU | 8.393** (7.316–9.628) | 12.414*** (6.482–23.773) | 8.197***c (6.995–9.605) |

| Constant | 0.042*** (0.018–0.095) | 0.033*** (0.006–0.191) | 0.040*** (0.015–0.103) |

| df | 21 | 20 | 20 |

| χ2 | 7382.19 | 19763.07 | 8242.66 |

| Observations | 4208 | 485 | 3723 |

Note: Analyses control for all covariates presented in Table 1. Only significant predictors are presented above.

Incidence rate ratio (IRR);

Confidence interval;

t-Test indicates coefficients are significantly different for Black and White subjects (p<0.05).

p<0.05;

p <0.01;

p <0.001.

Among Black adults, men, those who had a regular physician, those with diabetes, those who did not have kidney problems or hip fracture, and those who had a stay prior to CCU had more stays. Among White adults, age, gender, having heart-related procedures, experiencing a recent emergency hospitalization, heart disease hypertension, current smoker and having a stay prior to CCU were significant predictors of number of CCU stays.

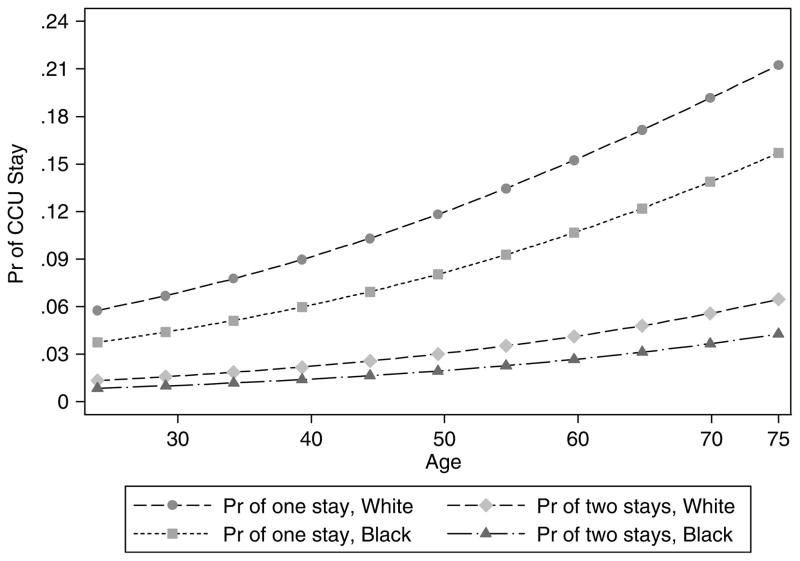

Based on ordinal logistic regression, Figure 2 graphically depicts the probability of one or two CCU stays for Black and White adults. The probability is graphed over age to examine whether disparities grow over the life course. Two findings are especially noteworthy. First, whether for first or second stay, the racial disparity is greater for older people than for younger people – the racial gap increases by age. Second, the racial disparity is greater for first stay than for second (and subsequent) stays. Generally speaking, Black adults were 38% less likely than White adults to have higher numbers of stays. Based on predicted probabilities compared to White adults, Black adults had 6% higher probability of having no CCU stays, 4% lower probability of having one CCU stay, and only 1% lower probability for having two CCU stays. In sum, the racial disparity was largest for having one CCU stay and increased over the life course. Initial access to CCU care is a key resource in combating accumulating racial inequality, and older Black people have particularly low odds of admission.

Figure 2.

Predicted probabilities of CCU stays for Black and White adults (adjusting for all predictors).

Finally, we examined racial differences in age-adjusted post-CCU mortality. These results are based on Cox proportional-hazards models of mortality and are presented in Table 5. We present two models, where model A controls for all predictors except Charlson comorbidity while model B accounts for comorbidities for the admission. Findings show that post-CCU mortality for Black adults was about 1.5 times the rate for White adults (HR = 1.532, p<0.01). As expected, older respondents and men and those with lower education, lower income, lacking private insurance, and who had a recent emergency hospitalization also had higher risk of dying. Both heart trouble and hypertension raised mortality risk.

Table 5.

Event history analysis for post-hospital mortality for adults with one CCU stay: National health and nutrition examination Survey I: epidemiologic follow-up study.

| Model A | Model B | |

|---|---|---|

| Black | 1.532**a (1.086–2.162)b | 1.324 (0.926–1.893) |

| Age | 1.086*** (1.074–1.099) | 1.077*** (1.063–1.091) |

| Female | 0.629*** (0.472–0.839) | 0.624*** (0.454–0.858) |

| Education | 0.943** (0.895–0.995) | 0.981 (0.927–1.039) |

| Income | 0.951* (0.900–1.005) | 0.963 (0.918–1.010) |

| Private insurance | 0.758* (0.570–1.009) | 0.703** (0.520–0.951) |

| Recent emergency hospitalization | 1.294* (0.990–1.690) | 1.171 (0.936–1.466) |

| Morbidity | ||

| Heart disease | 1.728*** (1.374–2.173) | 1.539** (1.023–2.313) |

| Hypertension | 1.467*** (1.145–1.879) | 1.502*** (1.179–1.913) |

| Health related factors | ||

| Charlson comorbidity | 1.590*** (1.491–1.696) | |

| Wald χ2 | 2639.31 | 4458.68 |

| df | 20 | 21 |

| N | 1233 | 1233 |

Note: Analyses control for all covariates presented in Table 1. Only significant predictors are presented above.

Hazard ratios;

Confidence intervals.

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001

The second equation reveals that after accounting for Charlson comorbidity index during the CCU stay, average age at death did not differ between Black and White adults. Although this suggests mediation, we performed tests of mediation (Baron and Kenny 1986) including Sobel’s (1982) test with the following formula:

where a = raw (unstandardized) regression coefficient for the association between independent variable and mediator; sa = standard error of a; b = raw coefficient for the association between the mediator and the dependent variable (when the independent variable is also a predictor of the dependent variable), and sb = standard standard error of b.

The test indicates that both mediation effects were significantly different from 0; thus, taken with other analyses, this demonstrates that accounting for Charlson comorbidity fully mediated the relationship between race and post-CCU mortality.

Discussion

Is there reason to believe that Black adults’ health disadvantages accumulate over the life course, as reflected in admission to and time spent in CCUs? We addressed this issue using 20 years worth of hospital records for a national sample of US adults. Based on our findings, a significant racial gap in access to CCUs exists, with Black adults less likely to be admitted and having a lower probability of one or more CCU stays than White adults. Once admitted, significant disparities persist: Black adults have fewer CCU stays, spend fewer days in the CCU, and overall have a smaller proportion of their hospital stay in a CCU.

The racial gaps observed here have been described by Hart (1971) and Fiscella and Shin (2005) as the inverse care law, which asserts that vulnerable populations receive less, or lower quality, care. Although these data do not permit us to address quality of care, we found fewer and shorter CCU stays for Black adults than for White adults of comparable socioeconomic standing and with similar levels of morbidity. This may be because Black people are more likely to be admitted at an advanced stage of disease development and to be treated by physicians with limited access to the most sophisticated facilities (Bach et al. 1999). Our findings indicate that Black adults’ limited opportunities for treatment extend beyond all-cause hospitalization to critical care for heart disease. The fact that these risks amplify over the life course (see Figures 1 and 2) provides further evidence of the difficulty in overcoming the detrimental effects of stratification; the initial disadvantages of minority status, coupled with lack of resources and opportunities, leads to further disadvantage for Black adults.

We also tested for the potential compensatory mechanism of unmet need. Unlike the case for all-cause hospitalization (Ferraro and Shippee 2008), we found no evidence that length of stay in the CCU was higher for Black adults than for White adults; rather, Black adults had lower likelihood of admission and shorter stays.

Despite the racial disparities in entrée and stay duration, we observed that the racial disparity shrunk for those persons who had two or more stays (Figure 2). This further illustrates that CCU stay during the first hospitalization is a pivotal resource for both Black and White adults. From a policy standpoint, the concern should be reducing and eliminating racial disparities for first stays as well as the early antecedents of heart disease.

The analyses also revealed that post-CCU mortality was higher for Black adults, but this difference was fully mediated by comorbidity. Coupling the findings on multiple CCU admissions and post-CCU mortality, the overall pattern reveals support for the inverse care law early in the process but a leveling of racial differences in the latter stages of care – a response to unmet need. Black people are disadvantaged in terms of CCU access, but the magnitude of the disparity shrinks after even one CCU admission.

Although most studies have examined utilization of cardiac procedures (Lillie-Blanton et al. 2002), to our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study to track racial differences from a community sample to CCU admission, length of CCU stay, and post-CCU mortality. Our findings built upon repeated calls for definitive information identifying the mechanisms of racial disparities in medical care in order to reduce inequality (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2000, Smedley et al. 2003). The racial disparity in access to CCUs is clear, reflecting a broader pattern of disadvantage that starts before admission to the medical system (Williams et al. 1995).

With regard to conceptual frameworks, the results provide limited support for the two perspectives (inverse care law and response to unmet need) and highlight the importance of early access for effective cardiac care. Theoretically, we see a need for a perspective that is more sensitive to the contingencies involved in care over the life course rather than generalizations that are constant over it. Cumulative inequality theory is one such attempt to specify the contingencies, but it is a preliminary step only. Racial and ethnic disparities are substantial and pervasive, but they change as a result of medical care. How they change merits more attention in future research, and this requires more studies that track people over longer periods of care.

We conclude that the chain of risks leading to CCU admission is distinct for Black and White adults. As part of lingering disadvantages related to race, Black individuals experience a chain of cultural and economic risks that influence their health care access (Kressin et al. 2004).

These experiences include discrimination, lack of communication between the patient and physician, and medical mistrust. As a result of these challenges, Black adults enter the health care system disadvantaged, yet are discharged quicker, adding to the accumulation of risks. In the context of generally lower SES, Black people have a higher prevalence of hypertension and heart disease, more comorbidity upon admission, and shorter CCU stays. The racial disparity is also evident in higher post-CCU mortality for Black adults, but the present research shows that this difference is actually due to their higher comorbidity.

The present study is limited in several respects. First, despite the relatively large sample, we were not able to systematically examine racial differences in specific CCU stays after the first hospitalization (due to insufficient statistical power). Second, these data span 20 years of observation but may not reflect the current level of racial disparity in CCU access. Third, these data do not permit us to identify characteristics of the hospitals in which these CCUs were located. Integrating organizational and ecological data may yield important insights on where the disparities are greatest.

The findings point to an accumulation of risks over the life course, and illustrate how timing of hospital utilization is distinct for Black and White adults. Black adults have shorter CCU stays than White adults after controlling for health status, health care utilization, and other characteristics. Higher morbidity, lower admission rates, fewer stays, and shorter stays reveal that racial disparity is far-reaching and exists even in such highly specialized units as CCUs. Black adults also have higher post-CCU mortality, but this may be attributed to their higher comorbidity, suggesting the gravity of accumulated unmet need. Finally, the disparities identified herein exist independently of insurance status, income, education, and other predictors that influence health and access to quality medical care (Smedley et al. 2003). As such, there is substantial evidence of cumulative racial inequality in accessing some of the most advanced facilities for treating heart disease.

Key findings.

Black adults are less likely than White adults to be admitted to a CCU and spend fewer days once admitted.

Mortality following CCU admission was higher for Black than for White adults, but the racial disparity was accounted for by differences in disease severity.

Black adults are disadvantaged in terms of CCU access, but the magnitude of the Black/White disparity shrinks after even one CCU admission.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by a grant (AG 11705) from National Institute on Aging and National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities to the second author. We thank Ann Howell, Shalon Irving, Jessica Kelley-Moore, Jori Sechrist, Markus H. Schafer, Nathan D. Shippee, and Karen S. Yehle for their helpful comments on the manuscript. Data were made available by the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research, Ann Arbor, MI. Neither the collector of the original data nor the Consortium bears any responsibility for the analyses or interpretations presented here.

Footnotes

We explored racial differences in CCU stay during second hospitalizations but did not have sufficient statistical power to undertake those analyses.

The scoring is as follows: metastatic tumor is given a six, diabetes with end-organ damage, moderate or severe renal disease, non-metastatic solid tumor, leukemia, lymphoma, and hemiplegia were given a two, and myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, dementia chronic pulmonary disease, connective tissue disease, ulcer disease, mild liver disease, and diabetes were scored as one.

We performed supplementary multivariate analyses to examine racial differences in ever having a CCU stay, but omitted them because the findings are similar to CCU admission during first hospitalizations: Black adults were significantly less likely to be admitted to CCU during the 20-year period compared to White adults.

We also examined racial differences in number of days during any CCU (analyses not shown), controlling for all predictors. We found that Black adults spent about half the number of days in the CCU as White adults; the expected count of CCU days for Black individuals was about half that of White individuals (IRR = 0.49, 95% CI 0.354–0.68).

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National healthcare disparities report. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bach PB, et al. Racial differences in the treatment of early stage lung cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;341 (16):1198–1205. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910143411606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51 (2):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlisle D, Leake BD, Shapiro MF. Racial and ethnic disparities in the use of cardiovascular procedures: associations with types of health insurance. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87 (2):263–267. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.2.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleves MA, Gould WW, Gutierrez RG. An introduction to survival analysis using Stata. College Station, TX: Stata Corporation; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- D’Anna LH, Ponce NA, Siegel JM. Racial and ethnic health disparities: evidence of discrimination’s effects across the SEP spectrum. Ethnicity and Health. 2010;15 (2):121–143. doi: 10.1080/13557850903490298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannefer D. Cumulative advantage/disadvantage and the life course: cross fertilizing age and social science theory. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2003;58B:S327–S337. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.6.s327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro KF, Shippee TP. Black and White chains of risk for hospitalization over 20 years. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2008;49 (2):193–207. doi: 10.1177/002214650804900206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro KF, Shippee TP, Schafer MH. Cumulative inequality theory for research on aging and the life course. In: Bengtson VL, Gans D, Putney NM, Silverstein M, editors. Handbook of theories of aging. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 413–435. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro KF, et al. The color of hospitalization over the life course: cumulative disadvantage in Black and White? Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2006;61B (6):S299–S306. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.6.s299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiscella K, Shin P. The inverse care law: implications for healthcare of vulnerable populations. Journal of Ambulatory Care Management. 2005;28 (4):304–312. doi: 10.1097/00004479-200510000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford E, Newman H, Deosaransingh K. Racial and ethnic differences in the use of cardiovascular procedures: findings from the California Cooperative Cardiovascular Project. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90 (7):1128–1134. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.7.1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillum RF. Sudden cardiac death in Hispanic American and African Americans. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87:1461–1466. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.9.1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein LB, et al. Charlson index comorbidity adjustment for ischemic stroke outcome studies. Stroke. 2004;35:1941–1945. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000135225.80898.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groeneveld PW, Heidenreich PA, Garber AM. Racial disparity in cardiac procedures and mortality among long-term survivors of cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2003;108:286–291. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000079164.95019.5A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin J. Obtaining robust standard errors for tobit [online] College Station, TX: StatCorp; 2005. [Accessed 13 November 2010]. Available from: http://www.stata.com/support/faqs/stat/tobit.html. [Google Scholar]

- Hart JT. The inverse care law. Lancet. 1971;1 (7696):405–412. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)92410-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasnain-Wynia R, Pierce D, Pittman MA. Who, when, and how: the current state on race, ethnicity, and primary language data collection in hospitals. Commonwealth Fund; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kamalesh M, et al. Diabetes status and racial differences in post-myocardial infarction mortality. American Heart Journal. 2005;150 (5):912–919. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, Daniels N, Robinson DE. Health disparities by race and class: why both matter. Health Affairs. 2005;24 (2):343–352. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klick J, Satel S. The health disparities myth: diagnosing the treatment gap. Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kressin NR, et al. Racial differences in cardiac catheterization as a function of patients’ beliefs. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94 (12):2091–2097. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N. Does racism harm health? Did child abuse exist before 1962? On explicit questions, critical science, and current controversies: an ecosocial perspective. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93 (2):194–199. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuh D, Ben-Shlomo Y. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laditka JN, Laditka SB. Race, ethnicity and hospitalization for six chronic ambulatory care sensitive conditions in the USA. Ethnicity & Health. 2006;11 (3):247–263. doi: 10.1080/13557850600565640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVeist TA, et al. The cardiac access longitudinal study. A study of access to invasive cardiology among African American and White patients. Journal of American College of Cardiology. 2003;41 (7):1159–1166. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leape LL, et al. Underuse of cardiac procedures: do women, ethnic minorities, and the uninsured fail to receive needed revascularization? Annals of International Medicine. 1999;130 (3):183–192. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-3-199902020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillie-Blanton, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in cardiac care: the weight of the evidence. Menlo Park, CA: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Long SJ. Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry RM, Mili F, Vaid IGM. Racial and ethnic differences in access to medical care: a synthesis of the literature. Menlo Park, CA: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Miller RS, et al. Outcomes of trauma patients who survive prolonged lengths of stay in the intensive care unit. Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 2000;48 (2):229–234. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200002000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2006, with chartbook on trends in the health of Americans. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Accessed 13 November 2010];International classification of diseases, ninth revision, clinical modification (ICD-9-CM) 2007 [online]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/otheract/icd9/abticd9.htm.

- NHLBI Obesity Education Initiative Expert Panel. Clinical guidelines on identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: the evidence report. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, Heart Lung and Blood Institute; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rosamond W, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2008 update. A report from the American Heart Association statistics committee and stroke statistics subcommittee. Circulation. 2008;117:e25–e146. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal GE, et al. Use of intensive care units for patients with low severity of illness. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1998;158 (10):1144–1151. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.10.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L. Patient and hospital characteristics associated with average length of stay. Health Care Management Review. 1996;21 (2):46–61. doi: 10.1097/00004010-199605000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal treatment confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic intervals for indirect effects in structural equations models. In: Leinhart S, editor. Sociological methodology. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Society of Critical Care Medicine. [Accessed 13 November 2010];Cardiac ICU. 2009 [online]. Available from: http://www.icu-usa.com/cardiac.html.

- StataCorp. Stata statistical software: release 10.0. College Station, TX: Stata Corporation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2010: understanding and improving health. 3. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Rucker TD. Understanding and addressing racial disparities in health care. Health Care Financing Review. 2000;21 (4):75–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JF, et al. African American and White patients admitted to the intensive care unit: is there a difference in therapy and outcome? Critical Care Medicine. 1995;23 (4):626–636. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199504000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]