Abstract

In natural history studies of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, women have a lower risk of disease progression to cirrhosis. Whether gender influences outcomes of HCV in the post-transplant setting is unknown. All patients transplanted for HCV-related liver disease from 2002–2007 at 5 U.S. transplant centers were included. The primary outcome was development of advanced disease, defined as biopsy-proven bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis. Secondary outcomes included death, graft loss, and graft loss with advanced recurrent disease. 1,264 patients were followed for a median of 3.0 years (IQR 1.8–4.7) −304 (24%) were female. The cumulative rate of advanced disease at 3-years was 38% for females and 33% for males (p=0.31) but after adjustment for recipient age, donor age, donor anti-HCV positivity, post-transplant HCV treatment, cytomegalovirus infection and center, female gender was an independent predictor of advanced recurrent disease (HR, 1.31; 95%CI, 1.02–1.70; p=0.04). Among women, older donor age and treated acute rejection were the primary predictors of advanced disease. The unadjusted cumulative 3–year rates of patient and graft survival were numerically lower in females than males, 75% vs. 80% and 74% vs. 78%, and in multivariable analyses, female gender was an independent predictor for death (HR, 1.30; 95%CI, 1.01–1.67; p=0.04) and graft loss (HR, 1.31; 95%CI, 1.02–1.67; p=0.03).

Conclusion

Female gender represents an under-recognized risk factor for advanced recurrent HCV disease and graft loss. Further studies are needed to determine whether modification of donor factors, immunosuppression, and post-transplant therapeutics can equalize HCV-specific outcomes in women and men.

Keywords: HCV outcomes, fibrosis, HCV treatment

INTRODUCTION

Natural history studies of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection have long established that chronic liver disease progresses at unequal rates between women and men. In two large studies, each including over 1,000 HCV-infected individuals, females experienced a slower rate of fibrosis progression per year(1) and a lower overall incidence of end-stage liver disease compared to men.(2) In vitro models supporting the anti-fibrinogenic effects of estrogen on hepatic stellate cells have provided a biologically plausible explanation for this gender effect in the non-transplant setting.(3, 4)

Whether gender affects the outcomes of HCV-infected patients in the post-transplant setting remains unknown. While several studies evaluating post-transplant outcomes have shown no significant gender effect,(5–8) there is a paucity of studies specifically investigating gender differences among HCV-infected liver transplant recipients, especially with respect to risk of recurrent cirrhosis. However, a recent multicenter Italian study with long-term histological follow-up identified female gender as a risk factor for severe recurrent HCV disease.(9) Moreover, a study of all liver transplants in the United States from 1992 through 1998 found that women transplanted for HCV-related liver disease experienced increased rates of graft loss compared with women without HCV infection – whereas this difference was not evident among HCV-infected versus non-HCV-infected men(10) – suggesting that an important interaction between gender and chronic HCV infection may exist.

Identifying key recipient, donor and transplant-related factors that affect the natural history of HCV disease post-transplantation is critical to the development of new strategies to attenuate fibrosis progression and prevent graft loss from HCV. Therefore, the ConsoRtiUm to Study Health Outcomes in HCV Liver Transplant Recipients (CRUSH-C) sought to specifically examine gender differences in HCV outcomes.

METHODS

Patient Population and Data Variables

This study included all patients transplanted for HCV-related liver disease from March 1, 2002 through December 31, 2007 at five experienced transplant centers (CRUSH-C) in the United States – 1) University of California, San Francisco, 2) Baylor University Medical Center, 3) New York Presbyterian Hospital-Columbia, 4) University of Colorado, and 5) Virginia Commonwealth University. Only adult patients receiving their first liver transplant were included. HCV status was determined using anti-HCV or HCV RNA tests. Patients were excluded if they had_documentation of viral clearance immediately after transplant in the absence of post-transplant antiviral treatment, graft loss < 31 days after liver transplant, or coinfection with human immunodeficiency virus. This study was approved by the institutional review boards at each of the five centers.

Recipient demographic and virologic data were retrospectively collected from electronic health records and manual chart review. Acute cellular rejection was defined as biopsy-proven rejection requiring treatment with high-dose bolus corticosteroids or anti-lymphocyte therapy. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection was defined as CMV infection requiring anti-CMV therapy. The dates and outcome of HCV treatment were determined via manual chart review and achievement of sustained virologic response (SVR) was based on documented undetectable HCV RNA at least six months after treatment discontinuation. Data regarding donor characteristics, warm ischemia time, and cold ischemia time were obtained from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS)/Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) registry.

Immunosuppression

Each center used a standard immunosuppression regimen, however, immunosuppression regimens were not uniform among the sites. The specific immunosuppression-related variables collected were (i) the use of tacrolimus versus cyclosporine at last follow-up and (ii) the use of corticosteroids as maintenance immunosuppression for > 3 months after the date of transplantation.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome of our study was advanced recurrent HCV disease, which was defined as the first date of bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis on biopsy. The secondary outcome measures were 1) patient mortality, 2) graft loss, and 3) graft loss with advanced recurrent HCV disease, defined as graft loss from complications of advanced liver disease (e.g., variceal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis) in the setting of documented advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis. Patients without histologic follow-up were excluded from the analysis for the primary outcome, but included in the analyses for all other outcomes. Since the cause of graft loss was missing in 45/342 graft failures (13%), a sensitivity analysis was performed assuming that all patients with an unknown cause of graft failure who had documented advanced HCV-disease died from complications of advanced recurrent disease.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical comparisons of the medians and proportions of baseline characteristics between women and men were calculated using Wilcoxon and Chi-square tests, respectively. Any characteristic that was significantly different between the two groups with a p-value <0.05 was evaluated in the final multivariable models. Gender, the primary predictor of interest, was forced into all models.

Survival rates were computed using Kaplan-Meier methods and compared using logrank tests. Univariable Cox proportional hazards analysis was first performed to identify factors independently associated with the outcome of interest. Those variables that yielded a hazard ratio associated with p <0.2 were evaluated for inclusion in the final multivariable model. Multivariable Cox regression models were built using backwards elimination of variables that were not significantly associated with the outcome of interest using a p <0.05. Post-transplant HCV treatment and episodes of treated acute rejection were treated as time-varying covariates. Clinically relevant interactions between gender and recipient age, recipient race, creatinine, HCC status, cytomegalovirus infection, episodes of rejection, and post-transplant antiviral treatment were evaluated in the final model at a p <0.2. To account for the effects of differing immunosuppression regimens as well as other potential unmeasured center-specific confounders, all final models were adjusted for center effect by including center as a covariate in the analyses. All tests of significance were 2-sided at a p-value <0.05.

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 11 software (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

A total of 1,369 [334 (24%) females, 1,035 (76%) males] adult HCV-infected liver transplant recipients were initially evaluated. Thirteen (4%) females and 31 (3%) males were excluded because their graft failed within 31 days of transplantation (p=0.42). An additional 17 (5%) females and 44 (4%) males were excluded because they were not at risk for HCV recurrence given that they were aviremic post-transplant in the absence of anti-viral treatment (p=0.50).

Of the 1,264 patients included in this study, 304 (24%) were female and 960 (76%) were male. There was no difference in the proportion of females and males transplanted per year (data not shown). Median follow-up was 2.9 years [interquartile range (IQR) 1.6–4.4 years] for females and 3.1 years (IQR 1.9–4.8 years) for males (p=0.09). Recipient, donor, and transplant-related characteristics are listed in Table 1. Baseline recipient characteristics were comparable between genders except for age at transplant, proportion of Caucasian, Hispanic, or Asian race, proportion undergoing living donor liver transplantation, and proportion having hepatocellular carcinoma at the time of transplant. Female recipients were more likely to receive a gender-mismatched allograft than males, but other donor characteristics including age, African-American race, and HCV status, were similar. Rates of treated acute rejection differed significantly between the two groups: 80 (26%) females versus 190 (20%) males required at least one bolus of corticosteroids; but 8 (3%) females versus 36 (4%) males were treated at least once with antilymphocyte therapy. Other characteristics evaluated but not significantly different between the two groups included body mass index at transplantation, cold ischemic time, and immunosuppressive medication at last follow-up.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of HCV-infected Liver Transplant Recipients and Their Donors

| Characteristics | Female (n=304) | Male (n=960) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recipient Characteristics | |||

| Age, median (IQR), years | 53.4 (49.1–59.0) | 53.0 (49.0–56.6) | 0.02 |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian, No. (%) | 172 (57) | 648 (68) | 0.001 |

| Hispanic, No. (%) | 70 (23) | 166 (17) | 0.03 |

| African-American, No. (%) | 37 (12) | 88 (9) | 0.13 |

| Asian, No. (%) | 13 (4) | 17 (2) | 0.01 |

| Other, No. (%) | 12 (4) | 41 (4) | 0.87 |

| Living donor liver transplant, No (%) | 30 (10) | 56 (6) | 0.02 |

| Body mass index, median (IQR) | 27.6 (24.2–31.5) | 27.6 (24.9–31.1) | 0.89 |

| Laboratory MELD score at transplant, median (IQR) | 18 (14–24) | 18 (13–23) | 0.38 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma, No. (%) | 93 (31) | 423 (44) | <0.001 |

| Donor Characteristics | |||

| Donor age, median (IQR), years | 42 (25–53) | 41 (26–52) | 0.73 |

| Donor African-American race, No. (%) | 41 (14%) | 130 (14%) | 0.99 |

| Positive donor hepatitis C antibody, No. (%) | 20 (7) | 71 (8) | 0.61 |

| Donor male gender, No. (%) | 139 (47%) | 627 (67%) | <0.001 |

| Cold ischemic time, median (IQR), hours | 7.5 (5.3–9.5) | 7.7 (5.6–9.6) | 0.32 |

| Post-transplant Characteristics | |||

| Maintenance immunosuppression medications | |||

| Tacrolimus use at last follow-up, No. (%) | 178 (59%) | 603 (63%) | 0.18 |

| Cyclosporine use at last follow-up, No. (%) | 75 (25%) | 260 (27%) | 0.41 |

| Corticosteroids at last follow-up, No. (%) | 142 (47%) | 407 (42.4%) | 0.19 |

| # Episodes of treated acute rejection* | |||

| 0, No. (%) | 217 (71) | 742 (77) |

.03 .03 |

| 1, No. (%) | 57 (19) | 172 (18) | |

| ≥2, No. (%) | 30 (10) | 46 (5) | |

| Post-transplant anti-HCV treatment, No. (%) | 96 (32) | 285 (30) | 0.53 |

| Sustained virologic response, No. (%)† | 22 (23) | 69 (24) | 0.80 |

| Cytomegalovirus infection, No. (%) | 32 (11) | 124 (13) | 0.27 |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; No., number; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease

Treated with either pulse-dosed steroids or anti-lymphocyte therapies

Of the patients who received anti-HCV therapies after transplant

Advanced Disease

Biopsy data were available for 90.6% of patients, with an equal proportion of females and males missing biopsy data (8.9% and 9.6%, respectively; p=0.72). Both females and males had a median of 3 biopsies per patient (p=0.82). The median times to first biopsy were similar between females and males (112 days vs. 130 days; p=0.93) as were the median times from the first biopsy to the subsequent biopsy documenting advanced fibrosis (or, for patients who did not have advanced fibrosis, to the last biopsy) [456 days vs. 458 days; p=0.60].

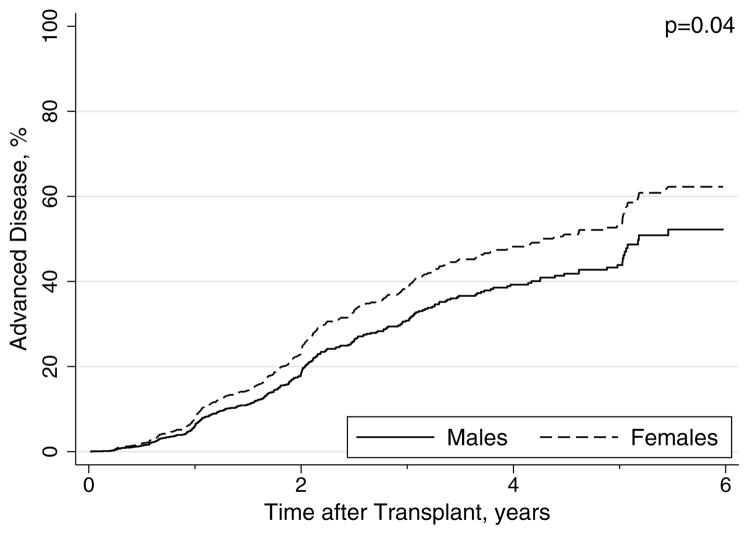

Median time to advanced fibrosis was 4.6 years for females compared with 5.2 years for males (p=0.31 logrank). Of the patients with available biopsy data, the cumulative rates of advanced disease at 1, 3, and 5 years were 6%, 38%, and 54% for females compared with 8%, 33%, and 45% for males in unadjusted analysis. However, after adjustment for other factors associated with advanced fibrosis, females had a significantly higher rate of advanced recurrent HCV disease relative to males (HR, 1.31; 95%CI, 1.02–1.70; p=0.04; Table 2; Figure 1). Other independent predictors of advanced disease were older recipient age, older donor age, HCV antibody positive donor, and treated CMV infection (Table 2). Receipt of post-transplant antiviral treatment prior to advanced fibrosis was protective (Table 2). In an exploratory analysis of factors associated with advanced fibrosis among female transplant recipients, the most important predictors were donor age (HR per year, 1.01; 95%CI, 1.00–1.03; p=0.07) and treated acute rejection before advanced fibrosis (HR, 1.56; 95%CI, 1.00–2.46; p=0.05).

Table 2.

Univariable and Multivariable Analyses of Predictors Associated with Advanced Fibrosis

| Covariates | Univariable* HR (95% CI) | p | Multivariable‡ HR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender | 1.14 (0.89–1.46) | 0.31 | 1.32 (1.02–1.71) | 0.04 |

| Recipient Age (per year) | 0.98 (0.96–0.99) | 0.008 | 0.98 (0.96–0.998) | 0.03 |

| Recipient African-American Race | 1.61 (1.18–2.20) | 0.003 | - | - |

| Living donor transplant‡ | 0.62 (0.36–1.05) | 0.08 | - | - |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 0.77 (0.61–0.97) | 0.03 | - | - |

| Donor age (per 10 years) | 1.22 (1.14–1.30) | <0.001 | 1.24 (1.15–1.33) | <0.001 |

| Donor cause of death (stroke/ other) | 1.47 (1.18–1.85) | 0.001 | - | - |

| Positive donor HCV antibody | 1.80 (1.22–2.66) | 0.003 | 1.51 (1.01–2.26) | 0.046 |

| Post-transplant antiviral treatment | ||||

| before advanced fibrosis | 0.61 (0.46–0.80) | <0.001 | 0.73 (0.54–0.99) | 0.04 |

| Treated CMV infection | 1.78 (1.34–2.37) | <0.001 | 1.70 (1.26–2.31) | 0.001 |

Includes all covariates associated with the outcome with a p-value <0.2. Gender, the predictor of interest, was forced into the model.

Other covariates that were evaluated were: renal function, cold/warm ischemia time, HBV co-infection, donor gender, episodes of rejection before fibrosis.

Adjusted for center effect

Compared with deceased donor liver transplant

Figure 1.

Adjusted Rates of Advanced Fibrosis By Gender in HCV-infected Liver Transplant Recipients.

Mortality

Death occurred in 308 (24.4%) patients with significantly more females (28.6%) dying compared with males (23.0%) [p=0.048]. Cumulative rates of survival at 1, 3, and 5 years post-transplant were 87%, 75%, and 66% for females and 92%, 80%, and 73% for males (p=0.04 logrank). In univariable analysis, we observed an increased risk of death for females compared to males (HR, 1.30; 95%CI, 1.01–1.67; p=0.04), and this significant difference persisted after adjustment for other factors associated with survival (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable Analyses of Predictors Associated with Mortality and Overall Graft Loss

| Covariates | Graft Loss*†‡ HR (95% CI) | p | Mortality*†‡ HR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender | 1.31 (1.02–1.67) | 0.03 | 1.33 (1.03–1.72) | 0.03 |

| Recipient Age (per year) | - | - | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 0.02 |

| Recipient African-American Race | 1.44 (1.03–2.00) | 0.03 | 1.56 (1.11–2.19) | 0.01 |

| Serum creatinine at transplant | 1.11 (1.00–1.22) | 0.045 | 1.11 (1.01–1.23) | 0.04 |

| Donor age (per 10 years) | 1.20 (1.12–1.29) | <0.001 | 1.21 (1.13–1.30) | <0.001 |

| Receipt of post-transplant antiviral treatment | 0.64 (0.49–0.84) | 0.001 | 0.56 (0.42–0.75) | <0.001 |

| Treated CMV infection | 1.63 (1.24–2.16) | 0.001 | 1.59 (1.18–2.14) | 0.002 |

Adjusted for center effect

Includes all covariates associated with the outcome with a p-value <0.2. Gender, the predictor of interest, was forced into the model.

Other covariates that were evaluated were: renal function, living versus deceased donor transplantation, donor cause of death, positive donor HCV antibody, cold/warm ischemia time, HBV co-infection, donor gender, episodes of rejection before fibrosis.

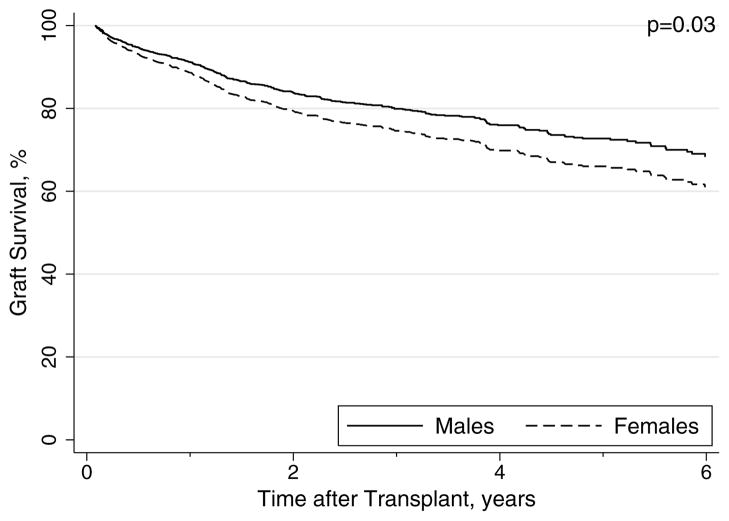

Overall and HCV-Specific Graft Survival

Graft failure occurred in 93 (31%) females and 249 (26%) males during the study period (p=0.11). Compared to males, females experienced a trend toward decreased graft survival at 1 (87 vs 90%), 3 (74 vs. 78%), and 5 years (71 vs. 64%) [p=0.08 logrank]. In univariable analysis, a similar trend was seen with female gender associated with a 23% increased risk of graft loss (HR, 1.23; 95%CI, 0.97–1.57; p=0.09). After adjustment for other recipient, donor and transplant-related factors in multivariable models, the association between female gender and graft failure increased, with a 30% increased risk of graft failure compared to male gender and was statistically significant (Table 3; Figure 2). Among female recipients, donor age (HR per year, 1.01; 95%CI, 1.00–1.03; p=0.02) and treated CMV infection (HR, 1.89; 95%CI, 1.08–3.30; p=0.03) emerged as independent predictors of graft loss.

Figure 2.

Adjusted Rates of Graft Survival by Gender in HCV-infected Liver Transplant Recipients

The reason for graft failure was known for 297/342 (87%) of graft failures. There were equal proportions of unknown causes of graft failure between females and males (13% for both; p=0.93). Of the recipients whose cause of graft failure was known, 39 (13%) females and 83 (9%) males experienced graft failure with advanced recurrent HCV disease (p=0.02). Cumulative rates of graft survival free from advanced HCV-disease at 1-, 3-, and 5-years were 97%, 91%, and 82% for females compared with 97%, 92%, and 88% for males (p=0.02 logrank). In multivariable models of graft failure with advanced HCV-disease, females experienced a substantially increased risk of graft failure with advanced HCV-disease (HR, 1.71; 95%CI, 1.14–2.58; p=0.01). A sensitivity analysis was performed assuming that all patients with an unknown cause of graft failure who had documented advanced HCV-disease died from complications of advanced recurrent disease. In this analysis, the female gender effect was somewhat attenuated (HR, 1.39; 95%CI, 0.94–2.05; p=0.10).

Association between recipient gender, donor gender, and outcomes

Detailed evaluation of the association between recipient gender, donor gender, and each outcome was performed. In univariable analysis, donor female gender was not significantly associated with advanced fibrosis, mortality, overall graft failure, or HCV-specific graft failure (Table 4). Bivariable analyses were then used to assess the contribution of both recipient gender and donor gender together on each outcome. In these analyses, donor gender was again not significantly associated with each of the four outcomes, but there was a trend toward a significant association between donor female gender and HCV-specific graft failure (Table 4). Lastly, in multivariable analyses, there was no association between donor gender and advanced fibrosis, mortality, or graft failure. However, donor gender was associated with a 41% decreased risk of HCV-specific graft failure (HR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.39–0.89; p=0.01) and therefore included in the final multivariable model.

Table 4.

Univariable, Bivariable, and Multivariable Analyses of the Association between Recipient Gender, Donor Gender, and Outcomes

| Outcome | Univariable | p | Bivariable | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced Fibrosis | ||||

| Recipient female gender | 1.14 (0.89–1.46) | 0.30 | 1.15 (0.89–1.49) | 0.28 |

| Donor female gender | 1.00 (0.80–1.26) | 0.98 | 0.98 (0.77–1.24) | 0.86 |

| Mortality | ||||

| Recipient female gender | 1.30 (1.01–1.66) | 0.04 | 1.31 (1.01–1.69) | 0.04 |

| Donor female gender | 1.10 (0.87–1.39) | 0.41 | 1.05 (0.83–1.33) | 0.67 |

| Overall graft loss | ||||

| Recipient female gender | 1.23 (0.97–1.57) | 0.09 | 1.25 (0.98–1.60) | 0.08 |

| Donor female gender | 1.04 (0.83–1.30) | 0.72 | 1.00 (0.80–1.26) | 0.99 |

| HCV-specific graft loss | ||||

| Recipient female gender | 1.56 (1.06–2.27) | 0.02 | 1.72 (1.16–2.56) | 0.007 |

| Donor female gender | 0.77 (0.52–1.14) | 0.20 | 0.70 (0.47–1.04) | 0.08 |

DISCUSSION

In this large, multi-center cohort study of 1,264 U.S. patients transplanted for HCV-related liver disease, rates of advanced recurrent disease, mortality, overall and HCV-specific graft loss were significantly higher in women than in men. Additionally, recipient female gender was consistently found to be an independent predictor of each of these four clinically relevant outcomes. Our results confirm and extend the findings of Belli, et al, who initially reported this gender difference in recurrent HCV disease in a study that included 93 females from three centers in Italy.(9) Further validation of our findings is a recently published analysis of UNOS data from the post-MELD era by Thuluvath et al that found that HCV-infected females experienced an increased risk of death compared to HCV-infected male recipients.(11) Importantly, our large, U.S.-based center-level study, which includes detailed biopsy data and post-transplant events (e.g., episodes of acute rejection, HCV treatment), offers a potential explanation for this gender difference in mortality – women die more frequently than men secondary to more aggressive recurrent HCV.

Although women were slightly older than men at transplant, had an increased likelihood of undergoing living donor transplantation, had lower rates of hepatocellular carcinoma, and higher rates of acute rejection, our multivariable analyses demonstrate that these differences alone did not account for the gender difference in outcomes. Nor did the gender of the donor significantly affect the association between recipient gender and outcomes in either bivariable or multivariable analyses, with the exception of HCV-specific graft loss where female donor gender strengthened the female recipient gender effect. Futhermore, as there were no gender differences among those who were excluded from our study for early graft loss (<31 days) or HCV aviremia, cohort selection bias is less likely to have contributed to the observed female gender effect.

Could our findings reflect a gender-specific etiologic effect on HCV-disease progression? Certainly. Epidemiologic studies have shown that women infected with chronic HCV experience slower fibrosis progression and lower rates of cirrhosis than men.(1, 12) Liver transplantation may “naturally select” for those women with chronic HCV who have genetic, virologic, and immunologic factors that lead to a higher risk of cirrhosis and also more rapidly progressive disease post-transplantation. Our study was not designed to test this hypothesis, but studies of HCV-infected patients evaluating cirrhotic females versus non-cirrhotic females versus males may shed further light on this issue.

Regardless of etiology, understanding the specific factors contributing to this gender difference is critical to improving post-transplant outcomes for all HCV-infected recipients. Our findings suggest that women may need to be monitored more closely for disease progression than under current practice. In particular, given our analyses demonstrating that donor age and treated acute rejection are the dominant predictors of poor outcome among females, women receiving older donor liver grafts or have had early acute rejection may need to be targeted for earlier post-transplant antiviral therapy or receive less aggressive treatment for acute rejection.

Interestingly, we found that antiviral therapy prior to the development of advanced fibrosis was associated with a 27% decreased risk of advanced fibrosis compared with patients who did not receive antiviral therapy prior to this outcome. While some studies have reported that the benefit of post-transplant antiviral treatment in HCV-infected liver transplant recipients is generally limited to those who achieve SVR,(13, 14) exploratory analyses of our data revealed that the protective effect was independent of SVR. Furthermore, antiviral therapy in the post-transplant setting in our cohort was protective against death and graft loss, a finding that is similar to the survival benefit seen in other more recently published studies.(15, 16) Although we found no significant differences in the baseline characteristics of the patients who received treatment compared with those who did not, whether our findings represent a true protective effect of treatment as opposed to a bias towards treating healthier patients certainly warrants further investigation. However, caution in interpreting these treatment-related associations in our study is needed, as we lack detailed information regarding dose, duration and tolerability of antiviral therapy in the treated patients, and these factors may influence treatment benefits.

There are several limitations to our study. Certain post-transplant metabolic factors, notably diabetes, have been shown to be important predictors of recurrent disease progression, but accurate information on post-transplant diabetes and insulin resistance are difficult to ascertain in a retrospective study such as ours. Second, the cause of graft failure was missing in 13% of our cohort, but without any evidence of a selection bias by gender. However, our sensitivity analysis confirmed a hazard of similar direction and magnitude of HCV-specific graft failure associated with female gender, and this does not change the association between gender and overall graft failure that we observed. In addition, while liver biopsies were not performed as part of a standard protocol among each of five centers, there were no gender differences in the median number of biopsies, time to the first biopsy, time from the first biopsy to the biopsy showing advanced fibrosis, so it is unlikely that this limitation accounts for the gender effect. These limitations underscore the importance of a developing a future prospective multi-center study to confirm our findings using this retrospective cohort as a stepping stone.

We acknowledge that there are inherent limitations to this multi-center study owing mainly to the heterogeneity of the centers’ practices for post-transplant care with respect to immunosuppression and HCV treatment. We carefully evaluated cyclosporine versus tacrolimus-based regimens in our multivariate models and found that their effect on the association between gender and each of the four outcomes was qualitatively similar to models that were adjusted for center effect. Therefore, we elected to adjust each multivariate model for center effect alone, as this statistical technique has the advantage of accounting for such recognized differences in addition to other potential confounders that we could not measure directly.

However, the multi-center nature of this study is also its strength. CRUSH-C is the largest and most contemporary cohort to examine gender effects on the natural history of HCV following transplantation. Given the relatively small numbers of outcomes among the female subgroup of HCV-infected transplant recipients, prior smaller, single-center studies were extremely limited in performing adjusted analyses to assess the relationship between female gender and HCV-specific outcomes.

In conclusion, female gender represents an important risk factor for advanced recurrent HCV disease and graft loss. Our retrospective study provides provocative evidence to support a long-term, prospective cohort study using standard immunosuppression regimens, protocol liver biopsies, and post-transplant treatment algorithms to determine whether modification of donor factors, immunosuppression, and post-transplant therapeutics may serve to equalize HCV-specific outcomes in women and men. Clearly, gender is important in post-transplant outcomes for HCV-infected liver transplant recipients but whether gender-specific algorithms for post-transplant management can optimize outcomes remains to be determined.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: Supported by the National Institutes of Health (T32 DK060414, JCL) and the University of California San Francisco Liver Center (P30 DK026743, JCL, NAT).

List of abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- CRUSH-C

Consortium to Study Health Outcomes in HCV Liver Transplant Recipients

- HR

hazard ratio

- IQR

interquartile range

- OPTN

Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network

- SVR

sustained virologic response

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

Footnotes

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest exist.

References

- 1.Poynard T, Bedossa P, Opolon P. Natural history of liver fibrosis progression in patients with chronic hepatitis C. The OBSVIRC, METAVIR, CLINIVIR, and DOSVIRC groups. Lancet. 1997 Mar 22;349(9055):825–32. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)07642-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas DL, Astemborski J, Rai RM, Anania FA, Schaeffer M, Galai N, et al. The natural history of hepatitis C virus infection: host, viral, and environmental factors. JAMA. 2000 Jul 26;284(4):450–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.4.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yasuda M, Shimizu I, Shiba M, Ito S. Suppressive effects of estradiol on dimethylnitrosamine-induced fibrosis of the liver in rats. Hepatology. 1999 Mar;29(3):719–27. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yuan Y, Shimizu I, Shen M, Aoyagi E, Takenaka H, Itagaki T, et al. Effects of estradiol and progesterone on the proinflammatory cytokine production by mononuclear cells from patients with chronic hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol. 2008 Apr 14;14(14):2200–7. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Velidedeoglu E, Mange KC, Frank A, Abt P, Desai NM, Markmann JW, et al. Factors differentially correlated with the outcome of liver transplantation in hcv+ and HCV- recipients. Transplantation. 2004 Jun 27;77(12):1834–42. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000130468.36131.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neumann UP, Berg T, Bahra M, Puhl G, Guckelberger O, Langrehr JM, et al. Long-term outcome of liver transplants for chronic hepatitis C: a 10-year follow-up. Transplantation. 2004 Jan 27;77(2):226–31. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000101738.27552.9D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Machicao VI, Bonatti H, Krishna M, Aqel BA, Lukens FJ, Nguyen JH, et al. Donor age affects fibrosis progression and graft survival after liver transplantation for hepatitis C. Transplantation. 2004 Jan 15;77(1):84–92. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000095896.07048.BB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iacob S, Cicinnati VR, Hilgard P, Iacob RA, Gheorghe LS, Popescu I, et al. Predictors of graft and patient survival in hepatitis C virus (HCV) recipients: model to predict HCV cirrhosis after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2007 Jul 15;84(1):56–63. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000267916.36343.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belli LS, Burroughs AK, Burra P, Alberti AB, Samonakis D, Camma C, et al. Liver transplantation for HCV cirrhosis: improved survival in recent years and increased severity of recurrent disease in female recipients: results of a long term retrospective study. Liver Transpl. 2007 May;13(5):733–40. doi: 10.1002/lt.21093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forman LM, Lewis JD, Berlin JA, Feldman HI, Lucey MR. The association between hepatitis C infection and survival after orthotopic liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2002 Apr;122(4):889–96. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thuluvath PJ, Guidinger MK, Fung JJ, Johnson LB, Rayhill SC, Pelletier SJ. Liver transplantation in the United States, 1999–2008. Am J Transplant. 2010 Apr;10(4 Pt 2):1003–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kenny-Walsh E. Clinical outcomes after hepatitis C infection from contaminated anti-D immune globulin. Irish Hepatology Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1999 Apr 22;340(16):1228–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904223401602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Angelico M, Petrolati A, Lionetti R, Lenci I, Burra P, Donato MF, et al. A randomized study on Peg-interferon alfa-2a with or without ribavirin in liver transplant recipients with recurrent hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2007 Jun;46(6):1009–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samuel D, Bizollon T, Feray C, Roche B, Ahmed SN, Lemonnier C, et al. Interferon-alpha 2b plus ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C after liver transplantation: a randomized study. Gastroenterology. 2003 Mar;124(3):642–50. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berenguer M, Palau A, Aguilera V, Rayon JM, Juan FS, Prieto M. Clinical benefits of antiviral therapy in patients with recurrent hepatitis C following liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2008 Mar;8(3):679–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.02126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Veldt BJ, Poterucha JJ, Watt KD, Wiesner RH, Hay JE, Rosen CB, et al. Insulin resistance, serum adipokines and risk of fibrosis progression in patients transplanted for hepatitis C. Am J Transplant. 2009 Jun;9(6):1406–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]