Abstract

Seminomas and nonseminomas (embryonal carcinomas, yolk sac tumors, teratomas, choriocarcinomas, mixed germ cell tumors) are the major histologic types of testicular germ cell tumors (TGCT). TGCTs composed of both seminomatous and nonseminomatous elements have been coded as their nonseminoma component in the World Health Organization (WHO) classification. In the late 1980's, a provisional International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O) morphology code for mixed germ cell tumors was introduced. Using data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program and two population-based German cancer registries, we examined the impact of MGCT classification on TGCT trends. Cases were identified using ICD-O topography (ICD-9: 186; ICD-10: C62) and morphology codes (seminoma = 9060-9062, 9064; embryonal carcinoma = 9070; yolk sack tumor = 9071; teratoma = 9080-9084, 9102; choriocarcinoma = 9100, 9101; MGCT = 9085; all nonseminoma = 9065-9102). As MGCTs and teratoma are often grouped as a single histologic group, we analyzed teratoma both including and excluding MGCTs. Between 1988 and 2007, incidence rates of MGCT in the U.S. increased 407%. Rates of teratoma including MGCT increased 80% while rates of teratoma excluding MGCT decreased 71%. Rates of embryonal carcinoma [-40%] and choriocarcinoma [-22%] also declined, suggesting that the code for MGCT is now being used for any mixed histology. Similar declines in incidence were observed in the German comparison populations. The declines in incidence of teratoma (excluding MGCT), embryonal carcinoma and choriocarcinoma in the US data since 1988 are likely due, in part, to increases in classifying any TGCT with mixed histology as MGCT. These results suggest that analysis of trends in specific histologic types of nonseminoma should be interpreted cautiously.

Keywords: testicular germ cell tumors, mixed germ cell tumors, histology, incident trends

Introduction

Testicular germ cell tumors (TGCT) are the most common malignancy among United States (US) men aged 15 to 34 years (Altekruse et al., 2010). TGCTs are histologically classified as seminomas and nonseminomas according to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O) (Fritz et al., 2000). Nonseminomas can be further subdivided into embryonal carcinomas, teratomas, yolk sac tumors and choriocarcinomas based on morphologic codes (Egevad et al., 2007; Parkin et al., 1998). According to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification, TGCTs composed of both seminomatous and nonseminomatous elements have been coded as their nonseminoma component (mixed embryonal carcinoma and teratoma, mixed teratoma and seminoma, and choriocarcinoma and teratoma/embryonal carcinoma), however, they have also been collectively categorized as ‘tumors of more than one histologic type’ (Woodward et al., 2004). A provisional field test morphology code (9085) for Mixed Germ Cell Tumors (MGCT) was introduced in the 1st and 2nd versions of ICD-O (Percy et al., 1990). Starting in the late 1980's in the US, the MGCT morphology code was increasingly used and it became a standard morphology code in the ICD-O 3rd version (Fritz et al., 2000). To examine the impact of this classification scheme on trends in TGCT in the US, we analyzed data from the National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program and two population-based cancer registries in Germany.

Materials and Methods

Incidence data for TGCT in the US were obtained from the SEER Program, a population-based cancer registry system (SEER 2010). Data that include approximately 10% of the US population, covering the years 1973-2007, were drawn from the nine original SEER registries (Connecticut, Hawaii, Iowa, New Mexico, Utah, San Francisco-Oakland, Detroit, Seattle-Puget Sound, and Atlanta).

Incident cases among men 15-49 years old were identified using ICD-O topography (ICD-9: 186; ICD-10: C62) (World Health Organization, 1977, 1992) and morphology codes (seminoma = 9060-9062, 9064; embryonal carcinoma = 9070; yolk sac tumor = 9071; teratoma = 9080-9084, 9102; choriocarcinoma = 9100, 9101; MGCT = 9085; all nonseminoma = 9065-9102). As MGCTs and teratoma have often been classified as a single histologic group (9080-9085), we analyzed teratoma both including and excluding morphology code 9085. Spermatocytic seminomas (code 9063) were not included in the analysis because they occur primarily among older men and are considered to have a distinct pathogenesis. Yolk sac tumors (code 9071) were not included in the analysis because they occur primarily in young boys and our analyses were limited to TGCT cases among 15-49 year olds.

Statistical Analysis

The SEER*Stat statistical package was used to calculate US TGCT incidence rates, age-adjusted to the US 2000 standard population. Rates were calculated for 5-year time periods to provide more stable estimates due to the small number of tumors in some groups. Rates were plotted by calendar year of diagnosis using a logarithmic scale for the ordinate.

For comparison with the results from the US SEER registries we used population-based incidence data from the Federal State of Saarland in West Germany covering the years 1973 to 2007 and pooled population-based incidence data from three cancer registries in East Germany covering the years 1963 to 2007. The histology-specific incidence trends from these databases were recently reported by Stang et al. (Stang et al., 2009). The same histologic subgroups were used to compare trends in incidence between the US SEER registries and the East and West German registries. Age-adjusted TGCT incidence rates were calculated using the US 2000 standard population and age-specific incidence rates from the German population-based registries.

The percent change (PC) in nonseminoma histology-specific rates was calculated over the specified time periods (1988-2007 for US and West Germany and 1983-2007 for East Germany) by taking the difference between the average rate of the first two years and the average rate of the last two years. The difference is then divided by the average rate of the first two years and multiplied by 100.

Results

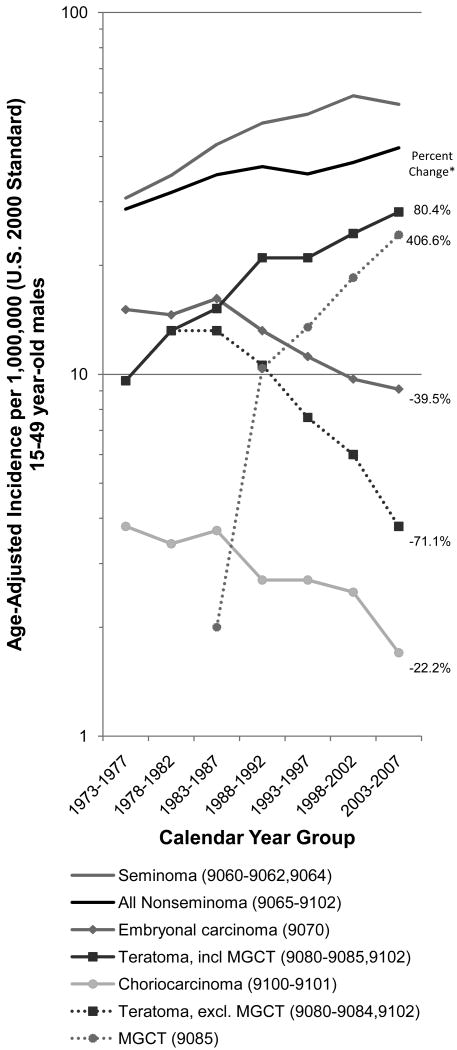

Between 1973 and 2007, 18,770 TGCTs (10,433 seminomas, 8,337 nonseminomas) were recorded in the SEER-9 registries among men 15-49 years of age. Of the nonseminomas, there were 2,944 embryonal carcinomas (35.3%), 2,442 MGCTs (29.3%), 2,145 teratomas excluding MGCTs (25.7%), 689 choriocarcinomas (8.3%), and 117 nonseminomas not further classified (code 9065) (1.4%). Age-specific TGCT incidence trends by histologic group are shown in Figure 1. The average annual percentage change (APC) in incidence over the entire time period (1973-2007) increased for seminoma [APC = 1.94, 95% CI = 1.57, 2.31] and remained relatively constant for nonseminoma [APC = 1.09, 95% CI = 0.81, 1.37].

Figure 1.

Age-adjusted incidence trends for TGCT histologic groups in SEER-9 registries, United States, 1973-2007.

*Percent change in age-adjusted incidence rate from 1988 to 2007.

In the SEER registry the first use of the MGCT morphology code occurred in 1984 with sporadic use through 1987 (72 cases recorded between 1984 and 1987). As of 1988, the MGCT code was commonly being used (Figure 1). Based on the percent change in incidence rates from 1988-2007 (Table 1), the rates for teratoma including MGCT increased 80.4%. During the same time period, the incidence rates for teratoma (excluding MGCT) decreased 71.1%, while MGCT rates increased 406.6%. The incidence rates for embryonal carcinoma [percent change (PC) = -39.5%] and choriocarcinoma [PC = -22.2%] declined from 1988 to 2007 as well. For all histologic subtypes the patterns were similar when stratified by race (white, black, other) and age at diagnosis (15-24, 25-34 and 35-49 years).

Table 1.

Percent change in nonseminoma histology specific TGCT incidence rates for 15-49 year-old males from population-based US and German cancer registries.

| US-SEER9 | West Germany (Saarland) | East Germany | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age-adjusted ratea | Age-adjusted ratea | Age-adjusted ratea | ||||||||||

| No. tumors | 1988-1992 | 2003-2007 | PC | No. tumors | 1988-1992 | 2003-2007 | PC | No. tumors | 1983-1987 | 2003-2007 | PC | |

| Embryonal carcinoma (9070) | 1536 | 13.2 | 9.1 | -39.5% | 77 | 5.9 | 7.7 | 37.9% | 761 | 13.5 | 9.0 | -35.6% |

| Teratoma, incl MGCT (9080-9085, 9102) | 3357 | 21.0 | 28.1 | 80.4% | 187 | 14.2 | 14.0 | 92.4% | 1240 | 16.9 | 19.3 | 9.4% |

| Choriocarcinoma (9100-9101) | 342 | 2.7 | 1.7 | -22.2% | 21 | 4.0 | 0.8 | -79.4% | 164 | 2.9 | 1.7 | -56.2% |

| Teratoma, excl MGCT (9080-9084,9102) | 984 | 10.6 | 3.8 | -71.1% | 159 | 13.9 | 10.5 | -8.5% | 841 | 16.0 | 9.6 | -43.6% |

| MGCT (9085) | 2373 | 10.4 | 24.3 | 406.6% | 28 | 0.3 | 3.5 | 1071.0% | 399 | 0.9 | 9.7 | 835.3% |

PC = Percent change in histology specific TGCT incidence rates from 1988-2007 for US and West Germany and from 1983-2007 for East Germany.

Age-adjusted incidence rate per 1,000,000 adjusted to 2000 US standard population, restricted to males age 15-49 years.

The percent change was also calculated from 1988-2007 for West Germany and from 1983-2007 for the East Germany (Table 1). Consistent with the percent change in incidence rates in the SEER data for the years 1988-2007, there were large increases in the incidence of MGCT over the observed time periods for both East [PC = 835.3%] and West [PC = 1071.0%] Germany. Similar to the decrease in incidence rates of embryonal carcinoma, choriocarcinoma and teratoma excluding MGCT in the US data, the incidence rates for embryonal carcinoma in East Germany as well as choriocarcinoma and teratoma excluding MGCT in both East and West Germany decreased (Table 1).

Discussion

We evaluated trends in specific histologic subtypes of nonseminoma TGCT and found that starting in the late 1980's the incidence rates of embryonal carcinoma, choriocarcinoma and teratoma excluding MGCT were declining in US and German population-based cancer registries. During the same time period we observed large increases in incidence rates for MGCT in all three cancer registries.

The change in histology coding pattern for nonseminomatous TGCT makes it difficult to evaluate subtype specific trends in nonseminoma because it appears that the MGCT categorization has evolved to include more than just tumors with teratoma and seminoma (Collins & Pugh, 1964). This is the first study that we know of that highlights the impact of changing histology code usage on trends in nonseminoma TGCT. Further, the change in histology coding patterns identified in the SEER cancer registry was confirmed in two German population-based cancer registries. The largest decline in rates of choriocarcinoma and embryonal carcinoma occurred during the intervals 1983-1987 and 1988-1992. It is unlikely that the rates of specific TGCT histologies changed dramatically in such a short time period, rather it is likely that changes in the ICD-O coding schema (tumors previously coded as embryonal carcinomas and choriocarcinomas are now being coded as MGCTs), increased awareness of the availability of the MGCT code on the part of the pathologists, increased understanding of teratomas, and improved identification of multiple cell types as a result of the introduction of immunohistochemistry with monoclonal antibodies have all led to the changing trends over time demonstrated by our data. Collectively the changing trends suggest that MGCT is being used for all mixed histologies, whether they are tumors with combinations of nonseminoma histologies or tumors with both seminomatous and nonseminomatous elements.

SEER data are descriptive only and as such do not allow for any assessment of etiology/causality. Given that this study is an analysis of registry data, it is subject to limitations incurred with the use of such data including the potential for incomplete data, lack of secondary review of histopathologic diagnoses and minor inconsistencies in tumor classification as a result of changing staging systems over time. Further, our results highlight another potential limitation of registry data: inconsistencies in histologic tumor classification as a result of changing ICD codes and coding practice over time.

In summary, the declines in incidence of teratoma (excluding MGCT), embryonal carcinoma and choriocarcinoma in the US data since 1988 are likely due, in part, to increases in classifying any TGCT with mixed histology as MGCT. Similar declines in incidence were observed in the German comparison populations. These results suggest that any analysis of trends in specific histologic subtypes of nonseminoma should be interpreted with caution.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute and by a grant of the German Science Foundation (DFG) [grant number STA621/6-1]. The analysis was undertaken in collaboration with C. Stegmaier (Saarland Cancer Registry) and R. Stabenow (Common Cancer Registry).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest of financial disclosures.

References

- Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou P, Waldron W, Ruhl J, Howlader N, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Eisner MP, Lewis DR, Cronin K, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Stinchcomb DG, Edwards BK, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2010. pp. 1975–2007. [Google Scholar]

- Collins DH, Pugh RCB. Classification and frequency of testicular tumours. Br J Urol. 1964;36(Suppl):1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egevad L, Heanue M, Berney D, Fleming K, Ferlay J. Chapter 4: Histologic groups. In: Curado MP, Edwards B, Shin HR, Storm H, Ferlay J, Heanue M, Boyle P, editors. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents. IX. IARC Press; Lyon, France: 2007. pp. 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz A, Percy C, Jack A, Shanmugaratnam K, Sobin LH, Parkin MD, Whelan S. International classification of disease for oncology (ICD-O) 3rd. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Parkin DM, Ferlay J, Shanmugaratnam K, Sobin L, Teppo L, Whelan SL. Chapter 4: Histological groups. In: Parkin DM, Shanmugaratnam K, Sobin L, Ferlay J, Whelan SL, editors. Histologic groups for comparative studies. IARC Press; Lyon, France: 1998. pp. 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Percy C, Van Holten V, Muir C. International classification of disease for oncology (ICD-O) 2nd. World Health Organization; Geneva: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Stang A, Rusner C, Eisinger B, Stegmaier C, Kaatsch P. Subtype-specific incidence of testicular cancer in Germany: a pooled analysis of nine population-based cancer registries. Int J Androl. 2009;32:306–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2007.00850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer.gov). (2010) SEER*Stat Database: Incidence - SEER 9 Regs Research Data, Nov 2009 Sub (1973-2007) <Katrina/Rita Population Adjustment> - Linked To County Attributes - Total U.S., 1969-2007 Counties, National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch, released April 2010, based on the November 2009 submission.

- Woodward PH, Heidenreich A, Looijenga LHJ, Oosterhuis JW, McLeod DG, Moller H, Manivel JC, Mostofi FK, Heilemariam S, Parkinson MC, Grigor K, True L, Jacobsen GK, Oliver TD, Talerman A, Kaplan GW, Ulbright TM, Sesterhenn IA, Rushton HG, Michael H, Reuter VE. Chapter 4: Testicular Germ Cell Tumours. In: Eble JN, Sauter G, Epstein JI, Sesterhann IA, editors. World Health Organization Classifcation of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs. IARC Press; Lyon, France: 2004. pp. 217–278. [Google Scholar]