Abstract

Members of the genus Bifidobacterium can be found as components of the gastrointestinal microbiota, and are believed to play an important role in maintaining and promoting human health by eliciting a number of beneficial properties. Bifidobacteria can utilize a diverse range of dietary carbohydrates that escape degradation in the upper parts of the intestine, many of which are plant-derived oligo- and polysaccharides. The gene content of a bifidobacterial genome reflects this apparent metabolic adaptation to a complex carbohydrate-rich gastrointestinal tract environment as it encodes a large number of predicted carbohydrate-modifying enzymes. Different bifidobacterial strains may possess different carbohydrate utilizing abilities, as established by a number of studies reviewed here. Carbohydrate-degrading activities described for bifidobacteria and their relevance to the deliberate enhancement of number and/or activity of bifidobacteria in the gut are also discussed in this review.

Keywords: Carbohydrate metabolism, Prebiotic, Probiotic, Carbohydrate, Bifidobacterial metabolism, Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003, Glycosyl hydrolases

Introduction

For an average individual the human gastrointestinal tract (GIT) is a natural habitat for approximately 1011–1012 microorganisms per gram of luminal content, collectively forming the gut microbiota with a total biomass of more than 1 kg in weight [39, 138, 156]. Metagenomic analyses allowed estimates of the total number of bacterial species that may be contained within the intestinal microbiota, ranging from approximately 500 to 1,000 distinct bacterial species [25, 34], to between 15,000 and 36,000 different species [29]. A very recent study on the minimal human gut metagenome has estimated that an individual harbours at least 160 prevalent bacterial species [99], which are also found in other individuals and which together form a complex community that colonizes the oral cavity, stomach, and small and large intestines in varying numbers [22, 58, 82]. The total number of bacterial cells is at least 10 times more than the sum of all human cells in a body [39], while the collective genome of all these bacterial cells, also termed the microbiome, consists of at least 150 times more genes than the total number of genes present in the human genome [99].

The bacterial colonization of the human GIT commences immediately after birth and is dependent on many factors, including the method of delivery (i.e. caesarian or vaginal) and feeding type of the infant (breast or formula feeding), supplementary or follow-on diet, exposure to antibiotics, hygiene conditions, and frequency and nature of illnesses, particularly gastrointestinal infections [27]. Various reports have shown that the majority of the fecal microbial population of breast-fed infants consists of bifidobacteria, with minor fractions represented by Escherichia coli,Bacteroides species and clostridia (for a review see [50]. Previous molecular analyses of the GIT microbiota composition in healthy adults have demonstrated that most of the endogenous microorganisms are members of just two phyla, Firmicutes and Bacteroides [25, 29, 41]. Likewise, a very recent culture-independent study, which was based on sequence analysis of amplified microbial ribosomal RNA-encoding genes [16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA)], revealed that the human GIT microbiota of an adult is exclusively comprised of members that belong to five bacterial phyla: Firmicutes (79.4%), Bacteroides (16.9%), Actinobacteria (1%), Proteobacteria (0.1%) and Verrucomicrobia (0.1%), and that most belong to the genera Faecalibacterium, Bacteroides, Roseburia, Ruminococcus, Eubacterium, Coprabacillus and Bifidobacterium [130]. However, human intestinal tract chip analysis revealed that members of the Bacteroides phylogenetic group may be more abundant than those of the Firmicutes in young individuals [102], a finding which is in agreement with those published by a recent metagenomic study [99]. In addition, various studies have shown that the adult human microbiota is specific to each individual, and furthermore depends on age, diet, genetic background, physiological state, microbial interactions and environmental factors [22, 33, 102, 134, 148].

Human studies have unveiled substantial differences in the gut microbiota composition of individuals [16, 25, 135] and such differences have been linked to variations of human physiology or predisposition to disease. Research on the gut microbiota composition in humans, as supported by work in gnotobiotic mouse models, has revealed the existence of a mutualistic relationship between humans and the gut microbiota, which acts as a virtual organ to (1) influence maturation of the immune system [76, 90], (2) defend against gastrointestinal pathogens and modulate responses following epithelial cell injury [35, 42]; for a review see [104], (3) affect the host’s energy balance through fermentation of non-digestible dietary fibre and anaerobic metabolism of peptides and proteins [3] as well as contributes to mammalian adiposity by regulating the metabolic network [4, 88], and (4) execute biotransformations that we are ill-equipped to perform ourselves, including processing and turn-over of xenobiotics [84, 115].

Bifidobacteria are among the prevalent groups of culturable anaerobic bacteria within the human and animal gastrointestinal tract, and among the first to colonize the human GIT, where they are thought to exert health-promoting actions, such as protective activities against pathogens via production of antimicrobial agents (e.g. bacteriocins) and/or blocking of adhesion of pathogens, and modulation of the immune response (for a review see [105]. Certain bifidobacteria are, because of these perceived health-promoting activities, commercially exploited as probiotic microorganisms. Growth and metabolic activity of probiotic bacteria, including bifidobacteria, can be selectively stimulated by various dietary carbohydrates, which for that reason are called “prebiotics” [32, 150]. In this respect it is important to mention that over 8% of the identified genes in most studied bifidobacterial genomes are predicted to be involved in carbohydrate metabolism, which is about 30% more than what the majority of other GIT microorganisms dedicate towards utilization of such compounds [57, 59, 124, 151]. There are relatively few publications that review characterized carbohydrate hydrolases of Bifidobacterium sp. [141, 142, 145]. Therefore, this review will focus on the currently available knowledge on bifidobacterial carbohydrate metabolism, covering the utilization of monosaccharides, disaccharides, oligosaccharides and polysaccharides.

Prebiotics and synbiotics as a tool to improve human health

As mentioned previously, the growth and metabolic activity of beneficial gut bacteria, such as bifidobacteria, can be selectively stimulated by non-digestible carbohydrates, termed “prebiotics”. A number of clinical studies on prebiotics and synergistic combinations of pro- and prebiotics, termed synbiotics [17], have shown that they improve general health and reduce disease risk (reviewed by [111]. However, more studies are needed to better understand the protective mechanism of prebiotics. A combination of galactooligosaccharides (GOS) and fructooligosaccharides (FOS) has been reported to reduce the incidence of atopic dermatitis and infectious episodes in infants during the first six months of life [1] and modulate the early phase of a vaccine-specific immune response in mice [154]. In addition, prebiotic short-chain FOS or FOS increases numbers of bifidobacteria and the Eubacterium rectale-Clostridium coccoides group in in vitro pH-controlled anaerobic faecal batch cultures [117]. Another paper recently reported that administration of FOS changes the composition of microbiota, by increasing bifidobacterial and lactobacilli counts in caecum and large intestine, and improves intestinal barrier function by upregulated expression of trefoil factor-3 and MUC2 gene [109]. Consumption of GOS has also been shown to prevent the incidence and symptoms of travelers’ diarrhea [13, 24]. Recent studies on irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) treatment with trans-GOS have shown that administration of this prebiotic reduces IBS symptoms and increase the overall quality of life in patients [100, 127]. These compelling results on the beneficial effects of prebiotics also imply that characterization of carbohydrate-modifying enzymes produced by health-promoting bacteria is important as such knowledge will facilitate the development of novel and perhaps more effective and/or selective prebiotics [141].

Bifidobacteria

Bifidobacteria, as mentioned above, are considered to play a key role in human health. Tissier (1900) was the first to report on the isolation of a Bifidobacterium species (then named Bacillus bifidus communis) from faeces of a breast-fed infant. Bifidobacteria are Gram-positive, heterofermentative, non-motile, non-spore forming microorganisms. Due to the fact that bifidobacteria produce lactic acid as one of their main fermentation end products, they are often included in the lactic acid bacteria (LAB), even though they are phylogenetically distinct, belonging to the high G+C content (ranging from 42 to 67%) Gram-positive bacteria [6]. The family Bifidobacteriaceae includes the genera Gardnerella and Bifidobacterium, and belongs to the phylum and cognominal class of Actinobacteria, within which they form a distinct order—the Bifidobacteriales. The phylum Actinobacteria also comprises, among others, Actinomycetaceae, propionibacteria, corynebacteria, mycobacteria and streptomyces [103, 149]. Thirty-nine species have been assigned to the genus Bifidobacterium, including recent additions such as Bifidobacterium tsurumiense [91] isolated from hamster dental plaque, Bifidobacterium mongoliense isolated from airag, a traditional Mongolian fermented horse milk product [160], Bifidobacterium crudilactis extracted from French raw milk and raw milk cheeses [20], Bifidobacterium psychraerophilum, originating from pig intestine [128], and three bifidobacterial species, Bifidobacterium bombi [52], Bifidobacterium actinicoloniformis and Bifidobacterium bohemicus [51], isolated from the digestive tract of different bumblebee species (Table 1). Furthermore, it seems that many bifidobacteria are still to be discovered as suggested by various metagenomic studies [11, 137]. A number of such bifidobacterial strains have been commercially exploited and are usually available on the market as functional components of dairy-based probiotic drinks (Table 2).

Table 1.

Currently recognized Bifidobacterium species

| Bifidobacterial species | Animal origin | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| B. actinicoloniformis | Bumblebee intestine | [51, 106] |

| B. adolescentis | Adult intestine | [106] |

| B. angulatum | Human faeces, sewage | [119] |

| B. animalis | [71] | |

| subsp. animalis | Chicken, rat, rabbit and calf faeces; river; | ex [120] |

| subsp. lactis | Fermented milk | ex [77] |

| B. asteroides | Hindgut of honeybee | [122] |

| B. bifidum | Adult intestine, human faeces, vagina | [93] |

| B. bohemicus | Bumblebee intestine | [51] |

| B. bombi | Bumblebee intestine | [52] |

| B. boum | Bovine rumen; piglet faeces | [121] |

| B. breve | Infant intestine, faeces, vagina | [106] |

| B. catenulatum | Child and adult intestine, vagina | [119] |

| B. choerinum | Pig faeces | [121] |

| B. coryneforme | Hindgut of honeybee | [9] |

| B. crudilactis | Raw milk and raw milk cheese | [20] |

| B. cuniculi | Rabbit faeces | [121] |

| B. dentium | Human dental caries, faeces, human vagina | [119] |

| B. gallicum | Adult intestine | (Lauer, 1990) |

| B. gallinarum | Chicken cecum | [159] |

| B. indicum | Bees; river | [122] |

| B. longum | Child and adult intestine, vagina | [72] |

| subsp. infantis | Infant intestine, vagina | ex [106] |

| subsp. suis | ex [73] | |

| subsp. longum | Child and adult intestine, vagina | ex [106] |

| B. magnum | Rabbit faeces; sewage | [123] |

| B. merycicum | Rumen | [7] |

| B. minimum | Sewage | [9] |

| B. mongoliense | Fermented mare’s milk product | [160] |

| B. pseudocatenulatum | Child faeces | [121] |

| B. pseudolongum | [165] | |

| subsp. globosum | Pig, chicken, calf and rat faeces, rumen | ex [9] |

| subsp. pseudolongum | Pig, chicken, calf and rat faeces, rumen | ex [78] |

| B. psychraerophylum | Porcine caecum | [128] |

| B. pullorum | Chicken faeces | [133] |

| B. ruminantium | Rumen | [7] |

| B. saeculare | Rabbit faeces | [8] |

| B. scardovii | Adult faeces | [44] |

| B. subtile | Sewage | [9] |

| B. thermophilum | Pig chicken and calf faeces, bovine rumen (B. ruminale) | [78] |

| B. thermacidophilum | Anaerobic digester | [23] |

| B. tsurumiense | Hamster dental plaque | [91] |

Adapted from [10]

ex indicates the author, who described or named a microorganism the first, by giving it a name, which a later author reclassified

Table 2.

Partial list of commercialized probiotic strains of Bifidobacterium sp

| Strain | Source |

|---|---|

| Bifidobacterium lactis Bb-12 | Chr. Hansen, Inc. (Denmark) |

| Bifidobacterium lactis FK120 | Fukuchan milk (Japan) |

| Bifidobacterium lactis HN019 (DR-10) | New Zealand Dairy Board (New Zealand) |

| Bifidobacterium lactis LKM512 | Fukuchan milk (Japan) |

| Bifidobacterium (animalis) lactis (same as BL Regularis) | Danone (France) |

| Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum BB536a | Morinaga Milk Industry Co., Ltd. (Japan) |

| Bifidobacterium longum subps. longum BB-46 | Chr. Hansen, Inc. (Denmark) |

| Bifidobacterium longum subps. longum SBT-2928a | Snow Brand Milk Products Co., Ltd (Japan) |

| Bifidobacterium breve strain Yakult | Yakult (Japan) |

| Bifidobacterium species 420 | Danlac (Canada) |

Species identification is as reported by the manufacturer, which may not reflect the current taxonomic status

The ‘human’ group of bifidobacterial species includes mainly those that were detected in the intestine or feces of adults or infants, and includes Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum, Bifidobacterium catenulatum, Bifidobacterium adolescentis, Bifidobacterium longum, Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium angulatum and Bifidobacterium dentium [153].

Like most intestinal bacteria, bifidobacteria are saccharolytic and are believed to play an important role in carbohydrate fermentation in the colon. Physiological data confirm that bifidobacteria can indeed ferment various complex carbon sources such as gastric mucin, xylo-oligosaccharides, (trans)-galactooligosaccharides, soy bean oligosaccharides, malto-oligosaccharides, fructo-oligosaccharides, pectin and other plant derived-oligosaccharides, although the ability to metabolize particular carbohydrates is species- and strain-dependent [17]. In general, gut bacteria degrade polymeric carbohydrates to low molecular weight oligosaccharides, which can subsequently be degraded to monosaccharides by the use of a wide range of carbohydrate-degrading enzymes. In the case of bifidobacteria, these monosaccharides are converted to intermediates of the hexose fermentation pathway, also called fructose-6-phosphate shunt or ‘bifid’ shunt [18, 118], and ultimately converted to short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and other organic compounds, some of which may be beneficial to the host. SCFAs, which are high in caloric content, for example, are adsorbed by the colonocytes and epathocytes, where they are metabolized and used as energy source. Besides that, SCFAs stimulate sodium and water adsorption in the colon and are known for their ability to induce enzymes that promote mucosal restitution [14].

Bifidobacterial genomes

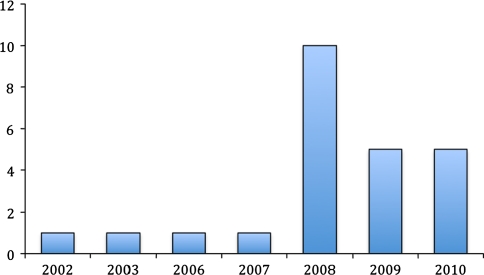

The genus Bifidobacterium sp. currently includes 39 characterized species (Table 1). The genomes of 24 different strains representing 10 bifidobacterial species have been subjected to sequence analysis, although only 10 genomes have been completely annotated (Fig. 1, Table 3). The fact that 20 bifidobacterial genomes have been sequenced during the last 3 years is a clear reflection of the significantly increased scientific interest in this particular group of bacteria, and is aimed at revealing the genetic basis for their health effects, and their colonization and persistence in the human gastrointestinal tract.

Fig. 1.

Number of partially and completely sequenced Bifidobacterium sp. genomes available in GenBank (October 2010)

Table 3.

General features of completely sequenced Bifidobacterium genomes

| Species | Genome size (bp) | GC content (%) | Genes | Proteins | Source | GeneBank no. | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. adolescentis ATCC15703 | 2,089,645 | 59 | 1,701 | 1,631 | Human GIT | NC_008618 | Unpublished |

| B. adolescentis L2-32 | 2,385,710 | 59 | 2,499 | 2,428 | Infant | NZ_AAXD00000000 | Unpublished |

| B. animalis subsp. lactis HN019 | 1,915,892 | 60 | 1,632 | 1,578 | Infant | NZ_ABOT00000000 | Unpublished |

| B. animalis subsp. lactis DSM10140 | 1,938,483 | 60 | 1,629 | 1,566 | French Yogurt | NC_012815 | [5] |

| B. animalis subsp. lactis AD011 | 1,933,695 | 60 | 1,604 | 1,528 | Infant faeces | NC_011835 | [53] |

| B. animalis subsp. lactis Bl-04 | 1,938,709 | 60 | 1,631 | 1,567 | Adult faeces | NC_012814 | [5] |

| B. animalis subsp. lactis Bb12 | 1,942,198 | 61 | 1,624 | NA | Fermented milk | CP001853 | [30] |

| B. angulatum DSM20098 | 2,007,108 | 59 | 1,811 | 1,748 | Human faeces | NZ_ABYS00000000 | Unpublished |

| B. bifidum NCIMB41171 | 2,186,140 | 62 | 1,888 | 1,833 | Adult faeces | NZ_ABQP00000000 | Unpublished |

| B. bifidum PRL2010 | 2,214650 | 59 | 1,848 | NA | Human GIT | CP001840 | [136] |

| B. breve UCC2003 | 2,422,668 | 59 | 1,868 | 1,590 | Infant faeces | Unpublished | [61] |

| B. breve DSM20213 | 2,297,799 | 58 | 2,309 | 2,251 | Human faeces | NZ_ACCG00000000 | Unpublished |

| B. dentium ATCC27678 | 2,642,081 | 58 | 2,500 | 2,430 | Dental caries | NZ_ABIX00000000 | Unpublished |

| B. dentium ATCC27679 | 2,633,776 | 58 | 2,402 | 2,336 | Urogenital tract | NZ_AEEQ01000000 | Unpublished |

| B. dentium Bd1 | ~2,600,000 | 59 | ~2,270 | NA | Dental caries | NC_013714 | [139, 152] |

| B. longum subsp. longum DJO10A | 2,375,792 | 60 | 2,062 | 1,990 | Human GIT | NC_010816 | [63] |

| B. longum supsp. longum NCC2705 | 2,256,640 | 60 | 1,798 | 1,727 | Human GIT | NC_004307 | [124] |

| B. longum subsp. longum subsp. infantis ATCC15697 | 2,832,748 | 59 | 2,588 | 2,416 | Infant GIT | NC_011593 | [126] |

| B. longum subsp. longum JDM301 | 2,477,838 | 59 | 2,035 | 1,958 | Human faeces | NC_014169 | [161] |

| B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC55813 | 2,372,858 | 60 | 2,171 | 2,109 | Infant GIT | NZ_ACHI00000000 | Unpublished |

| B. longum subsp. infantis CCUG52486 | 2,453,376 | 59 | 2,296 | 2,240 | Infant GIT | NZ_ABQQ00000000 | Unpublished |

| B. pseudocatenulatum DSM20438 | 2,304,808 | 56 | 2,220 | 2,151 | Human faeces | NZ_ABXX00000000 | Unpublished |

| B. catenulatum DSM16992 | 2,058,429 | 56 | 2,011 | 1,950 | Human faeces | NZ_ABXY00000000 | Unpublished |

| B. gallicum DSM20093 | 2,016,380 | 57 | 2,045 | 1,983 | Human faeces | NZ_ABXB00000000 | Unpublished |

The first complete genome sequence of B. longum subsp. longum NCC2705 was published in 2002 [124]. Ten other bifidobacterial genomes including those of B. longum subsp. longum DJO10A [63], and B. longum subsp. longum JDM301 [161], B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC15697 [126], B. adolescentis ATCC15703, four B. animalis subsp. lactis (DSM10140, AD011, Bl-04 and Bb12) [5, 30, 53], B. bifidum PRL2010 [136], B. dentium Bd1 [152] and the unpublished genome of B. breve UCC2003 strain have been completely sequenced and annotated (Table 3). An additional 12 bifidobacterial genome drafts are currently present in the database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) [131]. Furthermore, several additional genomes from Bifidobacterium species/strains (B. breve M-16 V, B. breve Yakult, B. breve UCC2003, B. animalis subsp. lactis (strains DN-173010 and BB-12). B. longum subsp. longum BB536 and B. longum subsp. infantis M-63) are at various stages of completion [65]. All completely and partially annotated bifidobacterial genomes range in size from 1.9 to 2.9 Mb, on which 1,604–2,588 genes have been identified and annotated (see Table 3). The predicted functions encoded by these bifidobacterial genome sequences have provided genetic evidence that bifidobacteria are prototrophic and are very well adapted for colonization of the (human) gastrointestinal tract (Table 4).

Table 4.

Protein distribution by COG functional categories of genomes from bifidobacteria and other groups of human intestinal bacteria (October 2010)

| COG description | % in Bifidobacteriuma | % in Bacteroidesa | % in Lactobacillusa | % in Actinobacteriaa | % in Bacteriaa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Translation | 6.3993 | 3.4093 | 6.9565 | 3.371 | 4.2968 |

| RNA processing nd modification | 0.0758 | 0 | 0 | 0.0229 | 0.0148 |

| Transcription | 6.5036 | 4.6561 | 7.343 | 7.1218 | 5.9643 |

| Replication, recombination and repair | 6.5131 | 4.4224 | 6.1353 | 4.3295 | 4.8261 |

| Chromatin structure and dynamics | 0 | 0.0195 | 0 | 0.0104 | 0.0269 |

| Cell cycle control, mitosis and meiosis | 1.204 | 0.565 | 1.256 | 0.6397 | 0.765 |

| Nuclear structure | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Defense mechanisms | 2.4649 | 2.143 | 2.2222 | 1.1668 | 1.259 |

| Signal transduction mechanisms | 3.2328 | 3.4288 | 2.7536 | 3.2459 | 3.9952 |

| Cell wall/membrane biogenesis | 3.6405 | 6.5848 | 4.3961 | 2.885 | 4.3931 |

| Cell motility | 0.0948 | 0.0584 | 0.2899 | 0.1722 | 1.4575 |

| Cytoskeleton | 0.0095 | 0 | 0 | 0.0145 | 0.0116 |

| Extracellular structures | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0154 |

| Intracellular trafficking and secretion | 0.7774 | 1.4027 | 1.0628 | 0.6363 | 1.7757 |

| Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones | 2.5218 | 1.9287 | 2.5121 | 2.2143 | 2.929 |

| Energy production and conversion | 2.3606 | 3.1366 | 3.6232 | 4.8755 | 4.8217 |

| Carbohydrate transport and metabolism | 8.7505 | 5.1822 | 8.8889 | 5.1296 | 4.9545 |

| Amino acid transport and metabolism | 9.5942 | 4.5782 | 7.4396 | 6.9266 | 7.2726 |

| Nucleotide transport and metabolism | 3.1191 | 1.5196 | 3.6232 | 1.6305 | 1.7769 |

| Coenzyme transport and metabolism | 2.3132 | 2.5716 | 1.401 | 2.8294 | 2.97 |

| Lipid transport and metabolism | 1.8771 | 1.5391 | 1.7391 | 5.0221 | 2.8606 |

| Inorganic ion transport and metabolism | 4.3989 | 4.8704 | 4.2029 | 4.3659 | 4.5898 |

| Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism | 0.493 | 0.8572 | 0.5797 | 4.5415 | 2.2675 |

| General function prediction only | 10.0588 | 8.5525 | 10.5797 | 11.4499 | 10.4609 |

| Function unknown | 4.8066 | 4.0327 | 6.9082 | 4.8 | 6.14 |

| Not in COGsb | 18.7903 | 34.5412 | 16.087 | 22.5988 | 20.1551 |

aThese data were retrieved from NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/)

bNot in COGs category includes mainly hypothetical protein

Bifidobacterial carbohydrate metabolism

The ability of gut commensals to degrade complex carbohydrates for which their host lacks digestive capacity has been well established. These complex carbohydrates can be dietary compounds (such as resistant starches, cellulose, hemicellulose, glycogen, galactan, xylan, pullulan, pectins and gums), host-derived compounds (such as mucin, glycosphingolipids, chondroitin sulphate, hyaluronic acid and heparin) [43], or carbon sources produced by other members of the GIT microbial community [60]. The amount and nature of the non-digestible carbohydrates present in someone’s diet is expected to have a direct impact on the metabolic activity, number and composition of the human GIT microbiota [156]. Gut microorganisms can utilize a diverse range of nutritional sources that escape degradation in the upper part of the GIT, as evidenced by the clear enrichment (certainly when comparing this to the human genome) for genes encoding enzymes that metabolize plant-derived oligo- and polysaccharides [156]. As expected, the genomes of gut commensals also carry more genes involved in mucin degradation than genomes of microorganisms from other environments [156].

The gene content of a bifidobacterial genome seems to reflect its adaptation to the human GIT environment, as is evident from the presence of genes that encode a variety of carbohydrate-modifying enzymes, such as glycosyl hydrolases, sugar ABC transporters, and PEP-PTS (PEP—phosphoenolpyruvate; PTS—phosphotransferase system) components, all of which are required for the metabolism of plant- and host-derived carbohydrates [5, 53, 63, 124]. As mentioned above a large proportion of the genes in a given bifidobacterial genome is predicted to be involved in sugar metabolism (Table 4), and approximately half of these are devoted to carbohydrate uptake, by means of ABC transporters, permeases and proton symporters, rather than through PEP-PTS transport [151].

The B. longum subsp. longum DJO10A genome was shown to contain 52 genes representing an estimated 10 ABC transporter systems, responsible for the uptake of various carbohydrates, as well as a putative glucose-specific PEP-PTS uptake system [67]. In silico analysis of the B. longum subsp. longum NCC2705 genome revealed 13 different ATP-binding cassette transporters and a single PEP-PTS system [95]. Transport of ribose, maltose, lactose, FOS, α-glucosides, raffinose, mannose-containing oligosaccharides, xylose and xylosides is thought to be facilitated by ABC-type systems in this microorganism, while glucose is internalized using a glucose-specific PEP-PTS [95]. The B. breve UCC2003 genome is reported to contain four PEP-PTS systems, one of which is a fructose-inducible fructose/glucose-uptake PTS system (encoded by the fru operon) [75]. In contrast to the sequenced B. longum and B. breve strains, B. animalis subsp. lactis, whose genome is significantly smaller than that of B. longum, has a lower number of genes involved in the utilization of carbon sources, does not encode PEP-PTS systems and contains only two genes specifying carbohydrate-specific ATP-binding proteins typical of ABC transporters [5]. This genome reduction of industrially exploited B. animalis subsp. lactis strains may be caused by a typical genomic evolution process common to microorganisms submitted to extended cultivation under artificial conditions such as those of industrial batch fermentation [63]. The human intestine is one of such environments, where large amounts of energy sources and metabolic intermediates produced by other members of microbiota are available for utilization.

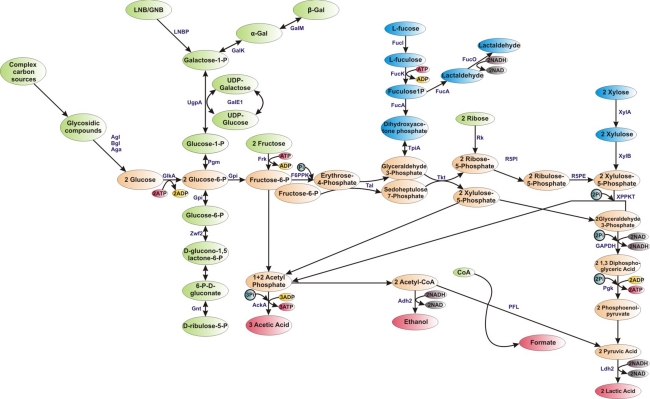

As mentioned above, bifidobacteria degrade hexose sugars through a particular metabolic pathway, termed the “bifid shunt”, where the fructose-6-phosphoketolase enzyme (EC 4.1.2.2) plays a key role (Fig. 2) [18]. This enzyme is considered to be a taxonomic marker for the family of Bifidobacteriaceae [28]. Additional enzymes are needed to channel various diet- and host-derived carbon sources into this so-called “bifid shunt” (Fig. 2), which allows bifidobacteria to produce more energy in the form of ATP from carbohydrates than the fermentative pathways operating in, for example, lactic acid bacteria, because the bifidobacterial pathway yields 2.5 ATP molecules from 1 mol of fermented glucose, as well as 1.5 mol of acetate and 1 mol of lactate [94]. In contrast, the homofermentative group of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) produces 2 mol of ATP and 2 mol of lactic acid from 1 mol of glucose, whereas heterofermentative LAB produce 1 mol each of lactic acid, ethanol and ATP per 1 mol of fermented glucose [116]. The ratio of lactate to acetate formed by bifidobacteria may vary depending on the carbon source utilized and also on the species examined [94].

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of carbohydrate degradation through “bifid shunt” in bifidobacteria. Abbreviations: AckA, acetate kinase; Adh2, aldehyde-alcohol dehydrogenase 2; Aga, α-galactosidase; Agl, α-glucosidase; Bgl, β-glucosidase; GalE1, UDP-glucose 4-epimerase; GalK, galactokinase; GalM, galactose mutarotase; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase C; GlkA, glucokinase; Gnt, 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase; Gpi, glucose 6-phosphate isomerase; Frk, fruktokinase; F6PPK, fructose-6-phosphoketolase; FucI, L-fucose isomerase; FucK, L-fuculose kinase; FucA, L-fuculose-1P aldolase;FucO, lactaldehyde reductase; Ldh2, lactate dehydrogenase; LNBP, lacto-N-biose phosphorylase;Pgk, phosphoglyceric kinase; Pgm, phosphoglucomutase; Pfl, formate acetyltransferase; Rk, ribokinase; R5PI, ribose-5-phosphate isomerase; R5PE, ribulose-5-phosphate epimerase; Tal, transaldolase; Tkt, transketolase; TpiA, triosephosphate isomerase;UgpA, UTP-glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase; XPPKT, xylulose-5-phosphate/fructose-6-phosphate phosphoketolase; XylA, xylose isomerase;XylB, xylulose kinase; Zwf2, glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase; Pi, phosphate

Carbohydrate metabolic abilities may vary considerably between bifidobacterial strains [70], as was confirmed by recent studies (Table 5). However, many of the characterized strains can utilize ribose, galactose, fructose, glucose, sucrose, maltose, melibiose and raffinose, but generally cannot ferment L-arabinose, rhamnose, N-acetylglucosamine, sorbitol, melezitose, trehalose, glycerol, xylitol and inulin (Table 5). Only a minority of the sugars utilized by bifidobacteria are believed to be internalized via a PEP-PTS [19, 75], while uptake of most of the remaining, more complex sugars is possibly facilitated through the use of specific ABC transporters [124]. Following internalization such carbohydrates can then be hydrolysed, phosphorylated, deacetylated and/or transglycosylated by dedicated intracellular enzymes (Table 6) [142, 151].

Table 5.

The fermentative characteristics of several species from the genus Bifidobacterium

| Strain name | L-Arabinose | D-Ribose | D-Xylose | D-Galactose | D-Fructose | D-Mannose | D-Glucose | L-Rhamnose | N-acetylglucosamine | Sorbitol | Salicin | D-Lactose | Cellobiose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. breve UCC2003* | − | + | − | + | + | ± | + | − | ± | − | ± | + | + |

| B. breve JCM7017* | − | + | NA | + | + | NA | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| B. breve JCM7019* | − | + | NA | ± | + | NA | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| B. breve NCFB2258* | − | + | NA | + | + | NA | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| B. breve NCIMB8815* | − | + | NA | + | + | NA | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| B. breve NCTC11815* | − | ± | NA | + | + | NA | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| B. breve NCFB2257* | − | + | NA | + | + | NA | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| B. longum subps. longum NCC2705 | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | NA |

| B. tsurumiense OMB115 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + |

| B. boum JCM1211 | − | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| B. thermacidophilum JCM11165 | + | − | − | + | + | ± | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| B. indicum JCM1302 | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | + |

| B. dentium JCM1195 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + |

| B. psychraerophilum LMG21775 | + | NA | + | NA | NA | − | NA | NA | NA | NA | + | NA | + |

| B. psychraerophilum YIT11814 | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | + |

| B. minimum JCM5821 | − | NA | − | NA | NA | − | NA | NA | NA | NA | − | NA | − |

| B. minimum YIT4097 | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| B. asteroides JCM8230 | + | NA | ± | NA | NA | ± | NA | NA | NA | NA | + | NA | + |

| B. coryneforme JCM5819 | + | NA | + | NA | NA | − | NA | NA | NA | NA | + | NA | + |

| B. indicum JCM1302 | + | NA | − | NA | NA | ± | NA | NA | NA | NA | + | NA | + |

| B. crudilactis LMG 23609 | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | NA | + | NA |

| B. mongoliense YIT10443 | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | + |

| B. mongoliense YIT10738 | + | − | − | + | ± | ± | + | − | − | − | − | + | − |

| Strain name | Melibiose | Melezitose | Turanose | Sucrose | Maltose | Trehalose | Raffinose | Mannitol | Glycerol | Xylitol | Starch | Glycogen | Inulin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. breve UCC2003* | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | NA | − | − | + | + | − |

| B. breve JCM7017* | NA | NA | NA | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| B. breve JCM7019* | NA | NA | NA | − | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| B. breve NCFB2258* | NA | NA | NA | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| B. breve NCIMB8815* | NA | NA | NA | − | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| B. breve NCTC11815* | NA | NA | NA | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| B. breve NCFB2257* | NA | NA | NA | ± | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| B. longum subps. longum NCC2705 | + | NA | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | NA | NA |

| B. tsurumiense OMB115 | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | − |

| B. boum JCM1211 | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | − |

| B. thermacidophilum JCM11165 | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | − |

| B. indicum JCM1302 | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | ± | − | − | − | − | − |

| B. dentium JCM1195 | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | − |

| B. psychraerophilum LMG21775 | NA | + | NA | + | − | NA | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| B. psychraerophilum YIT11814 | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| B. minimum JCM5821 | NA | − | NA | NA | + | NA | − | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| B. minimum YIT4097 | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − |

| B. asteroides JCM8230 | NA | − | NA | NA | ± | NA | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| B. coryneforme JCM5819 | NA | − | NA | NA | + | NA | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| B. indicum JCM1302 | NA | − | NA | NA | ± | NA | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| B. crudilactis LMG 23609 | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| B. mongoliense YIT10443 | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | − |

| B. mongoliense YIT10738 | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | ± | + | − |

Symbols: +, positive; −, negative; ± weak growth; NA, no information available;*, unpublished data from K. Pokusaeva & D. Van Sinderen. (Adapted from [125]

Table 6.

Putative carbohydrate-modifying enzymes identified in the genome sequences of Bifidobacterium

| EC number | Enzyme name | B. adolescentis ATCC15703 | B. adolescentis L2-32 | B. angulatum DSM20098 | B. animalis subps. lactis AD1011 | B. animalis subps. lactis BI-04 | B. animalis subps. lactis HN019 | B. bifidum NCUMB41171 | B. breve DSM20213 | B. catenulatum DSM16992 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hexosyltraspherases | ||||||||||

| EC:2.4.1.1 | Phosphorylase | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | NA | 1 | 1 | – | 1 |

| EC:2.4.1.7 | Sucrose phosphorylase. | 1 | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | 1 | 1 |

| EC:2.4.1.18 | 1,4-alpha-glucan branching enzyme | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | NA | – | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| EC:2.4.1.25 | 4-alpha-glucanotransferase | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | NA | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| EC:2.4.1.230 | Kojibijose phosphorylase | – | – | – | – | NA | – | – | – | – |

| Phosphotrasferases | ||||||||||

| EC:2.7.1.12 | Gluconokinase. | 1 | 1 | – | – | NA | – | – | – | 1 |

| EC:2.7.1.15 | Ribokinase. | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | NA | 1 | – | 2 | 1 |

| EC:2.7.1.17 | Xylulokinase. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | NA | 1 | – | – | 1 |

| EC:2.7.1.31 | Glycerate kinase. | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | NA | – | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| EC:2.7.1.4 | Fructokinase. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | NA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| EC:2.7.1.6 | Galactokinase. | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | NA | 1 | 1 | 6 | 1 |

| EC:2.7.6.1 | Ribose-phosphate diphosphokinase. | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Glycosyl hydrolases | ||||||||||

| EC:3.2.1.1 | α-amylase. | 1 | 1 | – | 1 | – | 1 | – | 1 | – |

| EC:3.2.1.10 | Oligo-1,6-glucosidase. | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | 2 | – |

| EC:3.2.1.14 | Chitinase | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| EC:3.2.1.18 | Exo-alpha-sialidase | – | – | – | – | NA | – | – | 1 | – |

| EC:3.2.1.20 | Alpha-glucosidase. | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| EC:3.2.1.21 | Beta-glucosidase. | 5 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | – | 4 | 4 |

| EC:3.2.1.22 | Alpha-galactosidase. | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| EC:3.2.1.23 | Beta-galactosidase. | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| EC:3.2.1.24 | Alpha-mannosidase | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | 1 | |

| EC:3.2.1.25 | Beta-mannosidase | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | – | – |

| EC:3.2.1.26 | Beta-fructofuranosidase | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | 1 | 1 |

| EC:3.2.1.31 | Beta-glucuronidase | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| EC:3.2.1.35 | Hyaluronoglucosaminidase | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | – |

| EC:3.2.1.37 | Xylan-1,4-beta- xylosidase | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | – | – | 3 |

| EC:3.2.1.4 | Cellulase | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | 1 |

| EC:3.2.1.41 | Pullulunase | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | NA | – | – | 1 | – |

| EC:3.2.1.45 | Glucosylceramidase | 1 | 1 | – | 2 | 2 | 2 | – | – | 1 |

| EC:3.2.1.51 | Alpha-L-fucosidase | – | – | – | – | NA | – | – | – | – |

| EC:3.2.1.52 | Beta-N-acetylhexosaminidase | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | NA | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| EC:3.2.1.54 | Cyclomaltodextrinase | – | – | – | – | NA | – | – | 1 | – |

| EC:3.2.1.55 | Alpha-N-arabinofuranosidase | 2 | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | – | 3 |

| EC:3.2.1.78 | Mannan endo-1,4-beta-mannosidase | – | – | – | 1 | NA | 1 | – | – | – |

| EC:3.2.1.86 | 6-phospho-beta-glucosidase | – | – | – | – | NA | – | 1 | – | – |

| EC:3.2.1.89 | Arabinogalactan endo-1,4-beta-galactosidase | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| EC:3.2.1.93 | Trehalose-6-phosphate hydrolase | 3 | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | – | – |

| EC:3.2.1.96 | Mannosyl-glycoprotein endo-beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase | – | – | – | – | NA | – | – | – | – |

| Isomerases | ||||||||||

| EC:5.3.1.1 | Triosephosphate isomerase | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | NA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| EC:5.3.1.4 | L-arabinose isomerase | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | NA | 1 | – | – | 1 |

| EC:5.3.1.5 | Xylose isomerase | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | NA | 1 | – | – | 1 |

| EC:5.3.1.6 | Ribose-5-phosphate isomerase | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | NA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| EC:5.3.1.9 | Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | NA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| EC number | Enzyme name | B. dentium ATCC27678 | B. gallicum DSM20093 | B. longum subps. longum ATCC15697 | B. longum subsp. Infantis ATCC55813 | B. longum subsp. Infantis CCUG52486 | B. longum subsp. longum DJO10A | B. longum subsp. longum NCC2705 | B. pseudocatenulatum DSM20438 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hexosyltraspherases | ||||||||||

| EC:2.4.1.1 | Phosphorylase | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| EC:2.4.1.7 | Sucrose phosphorylase. | 1 | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| EC:2.4.1.18 | 1,4-alpha-glucan branching enzyme | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| EC:2.4.1.25 | 4-alpha-glucanotransferase | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| EC:2.4.1.230 | Kojibijose phosphorylase | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Phosphotrasferases | ||||||||||

| EC:2.7.1.12 | Gluconokinase. | 1 | – | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | |

| EC:2.7.1.15 | Ribokinase. | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| EC:2.7.1.17 | Xylulokinase. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| EC:2.7.1.31 | Glycerate kinase. | 1 | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| EC:2.7.1.4 | Fructokinase. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| EC:2.7.1.6 | Galactokinase. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| EC:2.7.6.1 | Ribose-phosphate diphosphokinase. | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Glycosyl hydrolases | ||||||||||

| EC:3.2.1.1 | α-amylase. | – | – | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | |

| EC:3.2.1.10 | Oligo-1,6-glucosidase. | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| EC:3.2.1.14 | Chitinase | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | |

| EC:3.2.1.18 | Exo-alpha-sialidase | – | – | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | |

| EC:3.2.1.20 | Alpha-glucosidase. | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| EC:3.2.1.21 | Beta-glucosidase. | 12 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | |

| EC:3.2.1.22 | Alpha-galactosidase. | 5 | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| EC:3.2.1.23 | Beta-galactosidase. | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | |

| EC:3.2.1.24 | Alpha-mannosidase | 1 | – | 2 | 2 | – | 3 | 3 | – | |

| EC:3.2.1.25 | Beta-mannosidase | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| EC:3.2.1.26 | Beta-fructofuranosidase | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| EC:3.2.1.31 | Beta-glucuronidase | 1 | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | – | – | |

| EC:3.2.1.35 | Hyaluronoglucosaminidase | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| EC:3.2.1.37 | Xylan-1,4-beta- xylosidase | 2 | 1 | – | – | 1 | 1 | – | 4 | |

| EC:3.2.1.4 | Cellulase | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | |

| EC:3.2.1.41 | Pullulunase | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | |

| EC:3.2.1.45 | Glucosylceramidase | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | |

| EC:3.2.1.51 | Alpha-L-fucosidase | 1 | – | 3 | – | – | – | – | – | |

| EC:3.2.1.52 | Beta-N-acetylhexosaminidase | – | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| EC:3.2.1.54 | Cyclomaltodextrinase | – | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | |

| EC:3.2.1.55 | Alpha-N-arabinofuranosidase | 3 | – | – | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| EC:3.2.1.78 | Mannan endo-1,4-beta-mannosidase | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| EC:3.2.1.86 | 6-phospho-beta-glucosidase | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| EC:3.2.1.89 | Arabinogalactan endo-1,4-beta-galactosidase | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | – | |

| EC:3.2.1.93 | Trehalose-6-phosphate hydrolase | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | |

| EC:3.2.1.96 | Mannosyl-glycoprotein endo-beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | – | |

| Isomerases | ||||||||||

| EC:5.3.1.1 | Triosephosphate isomerase | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| EC:5.3.1.4 | L-arabinose isomerase | 1 | 1 | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| EC:5.3.1.5 | Xylose isomerase | 1 | 1 | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| EC:5.3.1.6 | Ribose-5-phosphate isomerase | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| EC:5.3.1.9 | Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

Data were obtained from sequenced Bifidobacterium genomes using find function in JGI-IMG; ± , present/absent; NA no available information

Analysis of recently sequenced bifidobacterial genomes disclosed intriguing insights into the relationship between these bacteria and their human host. For example, B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC15697 isolated from infant feces was demonstrated to possess a 43 kb gene cluster responsible for transport and utilization of non-digestible human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs), which may explain why this micro organism predominates in the gut of breast-fed infants [126]. B. animalis subsp. lactis strains and B. breve UCC2003, on the other hand, do not appear to encode the genes that allow HMO degradation, but instead are able to degrade complex plant-derived oligosaccharides, a clear indication of niche-specific adaptation [5, 87, 98, 113]. In addition, analysis of the recently sequenced and annotated genome of B. bifidum PRL2010 strain, isolated from an infant stool, revealed a set of chromosomal loci that targets host-derived glycans [136]. These O-linked glycans are known to be present in highly glycosilated proteins, also called mucins, produced by intestinal epithelial tissue.

Carbohydrate-modifying enzymes in Bifidobacterium sp.

Enzymes are single- or multi-chain proteins that catalyze specific chemical reactions [162], and are classified into six different classes with each enzyme assigned a unique four-figure code (EC number; IUB 1984), based on the nature of the catalyzed chemical reaction. Oligo- and polysaccharides can be modified by a range of different enzymes like hexosyl- and phosphotransferases, hydrolases and isomerases. Glycosyl hydrolases (also called glycoside hydrolases) appear to be the most critical group of enzymes for bifidobacteria, which allows them to adapt to and exist in the host environment through hydrolysis of complex dietary and host-produced carbohydrates.

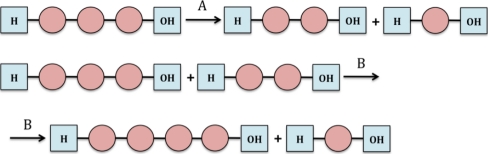

Glycoside hydrolases (EC 3.2.1.x) are a widespread group of enzymes, which hydrolyze the glycosidic bond between two or more carbohydrates, or between a carbohydrate and a non-carbohydrate moiety in the presence of water. The IUB-MB enzyme nomenclature of glycoside hydrolases (GH) is based on substrate specificity and occasionally on their molecular mechanism, and does not take the structural features of these enzymes into account. A classification of glycoside hydrolases in families based on amino acid sequence similarities has been proposed a couple of years ago (http://afmb.cnrs-mrs.fr/CAZY/index.html). Usually, hydrolysis of the glycosidic bond is performed by two catalytic residues of the enzyme: a general acid (proton donor) and a nucleophile/base. Depending on the spatial position of these catalytic residues, hydrolysis occurs via overall retention or inversion of the anomeric configuration [15]. Retaining glycoside hydrolases use a double displacement mechanism to catalyze hydrolysis with retention of configuration at the anomeric center, which can also yield elongated oligosaccharides with new types of linkages, a reaction which is termed transglycosylation [163]; Fig. 3). When a high concentration of sugar is used in the reaction, retaining enzymes can use the carbohydrate molecule as an incoming nucleophile instead of water, which results in the exchange of the sugar residues and can lead to the formation of new oligosaccharides with a higher degree of polymerization [142]. Inverting glycoside hydrolases always use water as the acceptor molecule (single displacement mechanism) and are therefore incapable of performing transglycosylation [142].

Fig. 3.

Schematic representation of a hydrolysis reaction (a) and a transglycosylation reaction (b) performed by glycosyl hydrolases. Circles represent a sugar moiety (adapted from [141]

Among the currently characterized bifidobacterial glycoside hydrolases are α-galactosidases (GH family 36), β-galactosidases (GH family 2 or 42), or enzymes active towards gluco-oligosaccharides, such as α-glucosidases and sucrose phosphorylases (both enzymes belong to GH family 13) (Table 6). As mentioned above, due to the typical mechanism of action the retaining enzymes can also be used for the formation of glycosidic linkages instead of hydrolysis. Oligosaccharides synthesized in this manner may be used as a prebiotic if they are selectively metabolized by probiotic (bifido)bacteria present in the colon.

β-galactosidases represent the most common (Table 6) as well as the best studied group of bifidobacterial glycosyl hydrolases with transglycosylic activity that can be used for the synthesis of prebiotic substances from lactose [101]. This enzymatic activity is essential for bifidobacteria as it allows them to grow on milk or milk-derived substrates, including lactose, lactose-derived (trans)galactooligosaccharides that contain β-galactosidic linkages [142]. The β-galactosidase hydrolytic and transglycosylic activities have been demonstrated and described for various bifidobacterial species, including those of B. angulatum [101], B. adolescentis [40], B. bifidum [37, 49, 80], B. longum [45, 110], B. longum subsp. infantis [46, 80] and B. pseudolongum [101]. B. bifidum NCIMB41171 encodes four different β-galactosidases with apparently different biochemical characteristics and with hydrolytic as well as transglycosylic activities [36, 37]. The ability of these enzymes to hydrolyze different substrates (e.g. β-D-(1 → 6) galactobiose, β-D-(1 → 4) galactobiose, β-D-(1 → 4) galactosyllactose and N-acetyllactosamine) contributes in a different way to the physiology of this microorganism [36] and provides advantageous properties for a better adaptation in a carbohydrate-rich GIT environment. Oral administration of galactooligosaccharides, produced by different β-glucosidases isolated from B. bifidum NCIMB41171 [140], significantly increases bifidobacterial numbers in the stool of healthy individuals, suggesting that these carbohydrates have bifidogenic properties and can successfully be used as prebiotic [21]. In addition, the characterized β-galactosidase from B. bifidum NCIMB 41171 was shown to degrade human milk oligosaccharides lacto–N–tetraose (LNT) and lacto–N–neotetraose more rapidly than lactose [79].

Interestingly, galacto-N-biose (GNB)/lacto-N-biose (LNB) I phosphorylase (GLNBP) was shown to be responsible for LNB degradation in all B. longum subsp. longum, B. longum subsp. infantis, B. breve, and B. bifidum, strains, which are the predominant species in infant intestines [55, 164]. Therefore, LNB is presumed to be a natural prebiotic for bifidobacteria [56]. The use of recombinant GLNBP from B. bifidum for large scale production of GNB, LNB and their derivatives, has recently been achieved [155, 166] and it will be very interesting to determine their prebiotic potential. In this content, it is worthy mentioning that studying bifidobacterial carbohydrate-degrading enzymes is not only important in order to identify and understand preferable bifidobacterial substrates, but also from a perspective of discovering novel selective (bifidogenic) prebiotics.

Likewise, the retaining enzymatic activity of α-glucosidase, which exhibits both α-glycosydic and transglycosydic activities, was shown to be commonly present in Bifidobacterium sp. [98, 143]. AglA and AglB from B. adolescentis DSM20083 have been shown to synthesize oligosaccharides from trehalose and sucrose, and maltose, sucrose and melizitose, respectively [143]. Two α-glucosidases (Agl1 and Agl2) from B. breve UCC2003 were demonstrated to exhibit transglycosylation activity towards sugars commonly found in honey—palatinose, trehalulose, trehalose, panose and isomaltose [98].

The vast majority of available bifidobacterial genomes are predicted to encode a sucrose phosphorylase belonging to the hexosyltransferase group of enzymes (EC:2.4.1.7; Table 6). Several studies have shown that sucrose phosphorylase from B. adolescentis DSM20083 [144], B. animalis subsp. lactis [132] and B. longum subsp. longum [54] can hydrolyze sucrose in the presence of free phosphate with the release of glucose-1-phosphate and fructose molecules, thus bypassing the ATP-requiring step of the glucose phosphorylation/hexokinase reaction in preparation for entry into the “Bifid shunt” (Fig. 3). In addition, these characterized sucrose phosphorylases were shown to display transglycosylation activity with glucose-1-phosphate as a donor and monomeric sugars, such as D- and L-arabinose, D- and L-arabitol, and xylitol in the case of B. longum subsp. longum [144], as acceptors.

Bifidobacterial fructofuranosidases are intracellular glycosyl hydrolases involved in the hydrolysis of the β-2,1 glycosydic bond between glucose-fructose, and/or fructose-fructose moieties present in fructooligosaccharides, which are generally found in fruits and vegetables. Even though comparative bifidobacterial genome analysis suggests that most sequenced Bifidobacterium sp. encode one and in some cases two β-fructofuranosidases (Table 6), only a small number of such enzymes have so far been biochemically characterized, such as the β-fructofuranosidases produced by B. adolescentis [81], B. animalis subsp. lactis [26, 48], B. breve UCC2003 [113] and B. longum subsp. infantis [47, 157]. Most, but not all, of the characterized β-fructofuranosidases exhibit hydrolytic activity towards various fructooligosaccharides, sucrose and inulin.

Certain bifidobacteria have the capacity to ferment arabinofuranosyl-containing oligosaccharides derived from plant cell wall polysaccharides, such as arabinan, arabinogalactan and arabinoxylan, through the action of arabinoxylan arabinofuranohydrolases. Growth of B. adolescentis DSM 20083on xylose and arabinoxylan-derived oligosaccharides was shown to induce the production of two different arabinofuranohydrolases [146]. Also different B. longum subsp. longum strains, including B667, were shown to produce arabinofuranohydrolases during growth on arabinoxylan [12, 69], although these enzymes do not appear to be a typical feature in bifidobacterial genomes. Nevertheless, arabinan, arabinogalactan and arabinoxylan are considered potential prebiotics that support growth of certain bifidobacterial strains [147].

α-galacto-oligosaccharides derived from soymilk and galactomannan can be hydrolyzed by α-galactosidases produced by Bifidobacterium sp. Typical α-galacto-oligosaccharides, that can be utilized by bifidobacteria are the disaccharide melibiose, the trisaccharide raffinose and the tetrasaccharide stachyose. Analysis of sequenced bifidobacterial genomes suggests that the majority of bifidobacterial strains encode at least one copy of an α-galactosidase-encoding gene. In spite of this, α-galactosidases, capable of catalyzing hydrolysis as well as transglycosylation of α-galacto-oligosaccharides, have only been studied in four bifidobacterial species, i.e. B. adolescentis [62, 146], B. bifidum [38], B. breve [167] and B. longum subsp. longum [31].

Starch, pullulan and amylopectin were demonstrated to be utilized by 11 different bifidobacterial strains out of 42 tested, most of which belong to the B. breve species [114]. This interesting observation indicates that the capacity to degrade these polymeric carbon sources may be a species-specific feature for B. breve. So far there are only two biochemically characterized bifidobacterial α-amylase activities reported. One is produced by B. adolescentis Int-57 [64], while the other is represented by the ApuB enzyme produced by B. breve UCC2003 [87]. The latter enzyme was demonstrated to have both amylopullulanase and α-amylase activities [87].

Human milk is a complex mixture of non-digestible oligosaccharides that help maintaining “healthy” gut microflora in infants (for a review see [168]. Human milk contains between 5–23 g/L of over 200 structurally different human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) [85]. Only members of Bifidobacterium and Bacteroides were shown to be able to utilize HMOs [68]. Among the bifidobacterial species, B. bifidum and B. longum subsp. infantis were shown to utilize the HMOs most efficiently. In contrast, B. breve and B. longum subsp. longum grow on these oligosaccharides to a lesser extent, while B. animalis and B. adolescentis are incapable of degrading HMOs [66]. Interestingly, all strains from the above study were obtained from international bacterial culture collections and thus they may have been extensively cultivated in synthetic media, which may have lead to the loss of genetic traits involved in HMO utilization. The 40 kb HMO gene cluster of B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 encodes four putative glycosidases, represented by a predicted galactosidase, fucosidase, sialidase and hexosaminidase, as well as a number of transporters that are believed to be required for utilization of HMO [126]. Another study described the gene operon lnpABCD which encodes lacto-N-biose I/galacto-N-biose metabolic pathway responsible for the intestinal colonization of bifidobacteria through utilization of lacto-N-biose I from human milk oligosaccharides or galacto-N-biose from mucin sugars [86]. B. bifidum, on the other hand, is believed to produce α-fucosidases and a lacto-N-biosidase for extracellular degradation of HMO with the concomitant release of lacto-N-biose, which can then be utilized intracellularly [55, 158]. B. longum subsp. longum and B. breve can utilize free lacto-N-neotetraose, one of the dominant components of HMOs, whereas B. breve also consumes various monomers that become available following extracellular HMO degradation [66, 158]. These different HMO utilization abilities seem to indicate niche-specific adaptation and cross-feeding abilities among various bifidobacterial species and strains.

Several recent studies have demonstrated that complex carbohydrates such as mucin, secreted by human epithelial cells, and pectin oligosaccharides, found in cell walls of plants, can also be utilized by certain Bifidobacterium sp. [2, 79, 92, 112].

Carbohydrate metabolism in B. breve UCC2003

B. breve UCC2003, an isolate from nursling stool [113], is presumed to represent a typical member of the natural microbiota of an infant intestine. B. breve UCC2003 encodes various carbohydrate-modifying enzymes that degrade, modify or create glycosidic bonds (Table 7). Only a small number of these glycosidases are found extracellularly (e.g. the amylopullulanase [87, 114] and the endogalactanase [88, 89], while the remainder is expected to be present as cytoplasmic enzymes (e.g. β-fructofuranosidase [113], β-1,4-glucosidase (K. Pokusaeva, M. O’Connell-Motherway, A. Zomer, J. MacSharry, G. F. Fitzgerald and D. Van Sinderen, submitted for publication), α-1,6-glucosidases [98] and ribokinase [97]).

Table 7.

Characterized sugar metabolic genes in B. breve UCC2003

| Gene/gene operon | Encoded enzyme | Substrate | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| fos operon | β-fructofuranosidase | FOS, sucrose | [113] |

| fru operon | Enzyme EII of PTS-PEP system | Fructose | [75] |

| apuB | Amylopullulanase | Starch, amylopectin, glycogen, pullulan | [89] |

| galA | Endogalactanase | Potato galactan | [88, 89] |

| agl1 | α-glucosidase | Panose, isomaltose, isomaltotriose, sucrose isomers | [98] |

| agl2 | α-glucosidase | Panose, isomaltose, isomaltotriose, sucrose isomers | [98] |

| rbs operon | Ribokinase | Ribose | [97] |

| cld operon | β-1,4-glucosidase | Cellobiose, cellodextrins | (Accepted for publication; Pokusaeva et al. 2010) |

Analysis of the ribose-induced transcriptome of B. breve UCC2003 revealed that the rbsACBDK gene cluster is responsible for the metabolism of ribose, a pentose sugar that can be found in the human gut [97]. Generation and phenotypic analysis of an rbsA insertion mutant established that the rbs gene cluster is essential for ribose utilization, and that its transcription is regulated by a LacI-type regulator encoded by rbsR, located immediately upstream of rbsA. In addition, the rbsK gene of the rbs operon of B. breve UCC2003 was shown to specify a ribokinase (EC 2.7.1.15), which specifically directs its phosphorylating activity towards D-ribose, converting this pentose sugar to ribose-5-phosphate [97].

Moreover, transcription of the recently characterized cldEFGC gene cluster of B. breve UCC2003 was shown to be induced upon growth on cellodextrins, implicating these genes in the metabolism of carbon sources that become available upon the degradation of cellulose by other representatives of the human colon microbiota (K. Pokusaeva, M. O’Connell-Motherway, A. Zomer, J. MacSharry, G. F. Fitzgerald and D. Van Sinderen, submitted for publication). Phenotypic analysis of a B. breve UCC2003::cldE insertion mutant confirmed that the cld gene cluster is exclusively required for cellodextrin utilization by this bacterium. The cldC gene of the cld operon of B. breve UCC2003 is the first described bifidobacterial β-glucosidase exhibiting hydrolytic activity towards various cellodextrins.

Control of carbohydrate metabolism in bifidobacteria

Besides carbohydrate metabolizing activities mentioned above, a fructose PEP-PTS system, which phosphorylates fructose at the C-6 position, was identified and characterized in B. breve UCC2003 [75]. This latter study also suggested that carbon catabolite control operates in this bacterium by a mechanism that appears to be different from known mechanisms. The expression level of the rbs operon, responsible for ribose uptake and metabolism, was shown to be decreased by approximately twofold when the culture was grown in a combination of glucose and ribose, suggesting that expression of the rbs operon was down-regulated to some degree by catabolite repression in the presence of a highly metabolizable sugar such as glucose [97]. Transcription of the fos operon, encoding β-fructofuranosidase from B. breve UCC2003, was also demonstrated to be dependent on secondary carbohydrate availability [113] as this operon was observed to be overexpressed when cells were grown on Actilight (an oligofructose) or sucrose, but not in the presence or combination of sucrose and glucose, or a combination of fructose and sucrose. Another interesting observation is that B. longum subsp. longum NCC2705 exhibits a lactose-over-glucose preference representing an example of reverse CCR, the mechanism of which is as yet not fully understood [96]. Selective substrate preference and different carbon catabolite control mechanisms between different bacterial as well as bifidobacterial strains indicate niche-specific adaptations between these different groups.

Many of the gene clusters involved in sugar metabolism contain LacI-type regulators, which suggest that the transcription of such gene clusters are subject to substrate-dependent repression [63, 83, 107, 108, 124, 126]. However, in just a few cases the precise action of the LacI-type regulator has been investigated in bifidobacteria [97, 132]. The RbsR protein, which controls ribose utilization through the regulation of the rbs operon of B. breve UCC2003, is presumed to act as an effective transcriptional repressor in the absence of the effector molecule, D-ribose, thereby preventing transcription [97]. Transcription of rbs is induced, thus facilitating ribose metabolism, in the presence of D-ribose, which decreases the affinity of RbsR for its specific DNA operator in the promoter region of the rbs operon. This control mechanism is similar to RbsR regulation in E. coli [74]. In contrast, the binding activity RbsR from B. subtilis and Corynebacterium glutamicum does not appear to be affected by D-ribose [83, 129]. Similarly, a LacI-type regulator was identified adjacent to the cld operon, which was demonstrated to be involved in transport and hydrolysis of cellodextrins in B. breve UCC2003 (K. Pokusaeva, M.O’Connell-Motherway, J. MacSharry, G. F. Fitzgerald and D. Van Sinderen, submitted for publication).

The above findings suggest that bifidobacteria employ LacI-type repressors to control transcription of many of its genes involved in carbohydrate metabolism, but that these genes are also subject to an as yet uncharacterized CCR system. The latter system requires further research in order to expand our knowledge and understanding on sugar metabolism and its hierarchical control.

Conclusions

Prebiotics have become part of the expanding functional food market. For development of new prebiotics and for understanding as to why certain oligo- and polysaccharides can or cannot be used as prebiotics, a better understanding about the carbohydrate-hydrolyzing enzymes encoded by Bifidobacterium sp. is needed. So far only a relatively small number of bifidobacterial glycosyl hydrolases have been characterized in detail [142]. The genome sequences from different Bifidobacterium strains has and will continue to provide us with theoretical information on putative carbohydrate—modifying enzymes and sugar transport systems, which may help these bacteria to adapt to the gastrointestinal environment and to interact with their human host. Characterization of novel glycosyl hydrolases with hydrolytic and transglycosylation activities will allow us to identify substrates that may act as novel prebiotics. More thorough research has to be performed to prove the functions of these predicted bifidobacterial enzymes and to determine their working mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

The Alimentary Pharmabiotic Centre is a research centre funded by Science Foundation Ireland (SFI), through the Irish Government’s National Development Plan. The authors and their work were supported by SFI (grant numbers 02/CE/B124 and 07/CE/B1368).

References

- 1.Arslanoglu S, Moro GE, Schmitt J, Tandoi L, Rizzardi S, Boehm G. Early dietary intervention with a mixture of prebiotic oligosaccharides reduces the incidence of allergic manifestations and infections during the first two years of life. J Nutr. 2008;138:1091–1095. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.6.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashida H, Maki R, Ozawa H, Tani Y, Kiyohara M, Fujita M, Imamura A, Ishida H, Kiso M, Yamamoto K. Characterization of two different endo-alpha-N-acetylgalactosaminidases from probiotic and pathogenic enterobacteria, Bifidobacterium longum and Clostridium perfringens. Glycobiology. 2008;18:727–734. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwn053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Backhed F, Ding H, Wang T, Hooper LV, Koh GY, Nagy A, Semenkovich CF, Gordon JI. The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:15718–15723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407076101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Backhed F, Manchester JK, Semenkovich CF, Gordon JI. Mechanisms underlying the resistance to diet-induced obesity in germ-free mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:979–984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605374104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barrangou R, Briczinski EP, Traeger LL, Loquasto JR, Richards M, Horvath P, Coute-Monvoisin AC, Leyer G, Rendulic S, Steele JL, Broadbent JR, Oberg T, Dudley EG, Schuster S, Romero DA, Roberts RF. Comparison of the complete genome sequences of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis DSM 10140 and Bl-04. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:4144–4151. doi: 10.1128/JB.00155-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biavati B. Bifidobacteria. In: Biavati B, Bottazzi V, Morelli L, Schiavi C, editors. Microorganisms as health supporters. Novara: Mofin-Alce; 2001. pp. 10–33. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biavati B, Mattarelli P. Bifidobacterium ruminantium sp. nov. and Bifidobacterium merycicum sp. nov. from the rumens of cattle. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1991;41:163–168. doi: 10.1099/00207713-41-1-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biavati B, Mattarelli P, Crociani F. Bifidobacterium saeculare: a new species isolated from feces of rabbit. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1991;14:389–392. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biavati B, Scardovi V, Moore W. Electrophoretic patterns of proteins in the genus Bifidobacterium and proposal of four new species. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1982;32:358. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biavati B, Vescovo M, Torriani S, Bottazzi V. Bifidobacteria: history, ecology, physiology and applications. Ann Microbiol. 2000;50:117–132. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boesten RJ, Schuren FH, Vos WM. A Bifidobacterium mixed-species microarray for high resolution discrimination between intestinal bifidobacteria. J Microbiol Methods. 2009;76:269–277. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crittenden R, Karppinen S, Ojanen S, Tenkanen M, Fagerstrom R, Matto J, Saarela M, Mattila-Sandholm T, Poutanen K. In vitro fermentation of cereal dietary fibre carbohydrates by probiotic and intestinal bacteria. J Sci Food Agric. 2002;82:781–789. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cummings JH, Christie S, Cole TJ. A study of fructo oligosaccharides in the prevention of travellers’ diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1139–1145. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Argenio G, Mazzacca G. Short-chain fatty acid in the human colon. Relation to inflammatory bowel diseases and colon cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;472:149–158. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-3230-6_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davies G, Henrissat B. Structures and mechanisms of glycosyl hydrolases. Structure. 1995;3:853–859. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00220-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Filippo C, Cavalieri D, Di Paola M, Ramazzotti M, Poullet JB, Massart S, Collini S, Pieraccini G, Lionetti P. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:14691–14696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005963107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vrese M, Schrezenmeir J. Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 2008;111:1–66. doi: 10.1007/10_2008_097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vries W, Stouthamer AH. Pathway of glucose fermentation in relation to the taxonomy of bifidobacteria. J Bacteriol. 1967;93:574–576. doi: 10.1128/jb.93.2.574-576.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Degnan BA, Macfarlane GT. Transport and metabolism of glucose and arabinose in Bifidobacterium breve. Arch Microbiol. 1993;160:144–151. doi: 10.1007/BF00288717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delcenserie V, Gavini F, Beerens H, Tresse O, Franssen C, Daube G. Description of a new species, Bifidobacterium crudilactis sp. nov., isolated from raw milk and raw milk cheeses. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2007;30:381–389. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Depeint F, Tzortzis G, Vulevic J, I’Anson K, Gibson GR. Prebiotic evaluation of a novel galactooligosaccharide mixture produced by the enzymatic activity of Bifidobacterium bifidum NCIMB 41171, in healthy humans: a randomized, double-blind, crossover, placebo-controlled intervention study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:785–791. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.3.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dethlefsen L, Eckburg PB, Bik EM, Relman DA. Assembly of the human intestinal microbiota. Trends Ecol Evol. 2006;21:517–523. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dong X, Xin Y, Jian W, Liu X, Ling D. Bifidobacterium thermacidophilum sp. nov., isolated from an anaerobic digester. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50(Pt 1):119–125. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-1-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drakoularakou A, Tzortzis G, Rastall RA, Gibson GR. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized human study assessing the capacity of a novel galacto-oligosaccharide mixture in reducing travellers’ diarrhoea. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64:146–152. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2009.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eckburg PB, Bik EM, Bernstein CN, Purdom E, Dethlefsen L, Sargent M, Gill SR, Nelson KE, Relman DA. Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science. 2005;308:1635–1638. doi: 10.1126/science.1110591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ehrmann MA, Korakli M, Vogel RF. Identification of the gene for beta-fructofuranosidase of Bifidobacterium lactis DSM10140(T) and characterization of the enzyme expressed in Escherichia coli. Curr Microbiol. 2003;46:391–397. doi: 10.1007/s00284-002-3908-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fanaro S, Chierici R, Guerrini P, Vigi V. Intestinal microflora in early infancy: composition and development. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2003;91:48–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2003.tb00646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Felis GE, Dellaglio F. Taxonomy of Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria. Curr Issues Intest Microbiol. 2007;8:44–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frank DN, St Amand AL, Feldman RA, Boedeker EC, Harpaz N, Pace NR. Molecular-phylogenetic characterization of microbial community imbalances in human inflammatory bowel diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:13780–13785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706625104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garrigues C, Johansen E, Pedersen MB. Complete genome sequence of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BB-12, a widely consumed probiotic strain. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:2467–2468. doi: 10.1128/JB.00109-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garro MS, Giori GS, Valdez GF, Oliver G. Alpha-D-Galactosidase (EC 3.2.1.22) from Bifidobacterium longum. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1994;19:16–19. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gibson GR. Prebiotics as gut microflora management tools. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:S75–S79. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31815ed097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gibson GR, Beatty ER, Wang X, Cummings JH. Selective stimulation of bifidobacteria in the human colon by oligofructose and inulin. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:975–982. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90192-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gill SR, Pop M, Deboy RT, Eckburg PB, Turnbaugh PJ, Samuel BS, Gordon JI, Relman DA, Fraser-Liggett CM, Nelson KE. Metagenomic analysis of the human distal gut microbiome. Science. 2006;312:1355–1359. doi: 10.1126/science.1124234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gilmore MS, Ferretti JJ. Microbiology. The thin line between gut commensal and pathogen. Science. 2003;299:1999–2002. doi: 10.1126/science.1083534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goulas T, Goulas A, Tzortzis G, Gibson GR. Comparative analysis of four beta-galactosidases from Bifidobacterium bifidum NCIMB41171: purification and biochemical characterisation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;82:1079–1088. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1795-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goulas T, Goulas A, Tzortzis G, Gibson GR. Expression of four beta-galactosidases from Bifidobacterium bifidum NCIMB41171 and their contribution on the hydrolysis and synthesis of galactooligosaccharides. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;84:899–907. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goulas T, Goulas A, Tzortzis G, Gibson GR. A novel alpha-galactosidase from Bifidobacterium bifidum with transgalactosylating properties: gene molecular cloning and heterologous expression. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;82:471–477. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1750-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hattori M, Taylor TD. The human intestinal microbiome: a new frontier of human biology. DNA Res. 2009;16:1–12. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsn033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hinz SW, Broek LA, Beldman G, Vincken JP, Voragen AG. Beta-galactosidase from Bifidobacterium adolescentis DSM20083 prefers beta(1, 4)-galactosides over lactose. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;66:276–284. doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1745-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hold GL, Pryde SE, Russell VJ, Furrie E, Flint HJ. Assessment of microbial diversity in human colonic samples by 16S rDNA sequence analysis. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2002;39:33–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2002.tb00904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hooper LV. Bacterial contributions to mammalian gut development. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hooper LV, Midtvedt T, Gordon JI. How host-microbial interactions shape the nutrient environment of the mammalian intestine. Annu Rev Nutr. 2002;22:283–307. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.011602.092259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoyles L, Inganas E, Falsen E, Drancourt M, Weiss N, McCartney AL, Collins MD. Bifidobacterium scardovii sp. nov., from human sources. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2002;52:995–999. doi: 10.1099/00207713-52-3-995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hsu CA, Lee SL, Chou CC. Enzymatic production of galactooligosaccharides by beta-galactosidase from Bifidobacterium longum BCRC 15708. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:2225–2230. doi: 10.1021/jf063126+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hung MN, Lee BH. Purification and characterization of a recombinant beta-galactosidase with transgalactosylation activity from Bifidobacterium infantis HL96. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;58:439–445. doi: 10.1007/s00253-001-0911-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Imamura L, Hisamitsu K, Kobashi K. Purification and characterization of beta-fructofuranosidase from Bifidobacterium infantis. Biol Pharm Bull. 1994;17:596–602. doi: 10.1248/bpb.17.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Janer C, Rohr LM, Pelaez C, Laloi M, Cleusix V, Requena T, Meile L. Hydrolysis of oligofructoses by the recombinant beta-fructofuranosidase from Bifidobacterium lactis. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2004;27:279–285. doi: 10.1078/0723-2020-00274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jorgensen F, Hansen OC, Stougaard P. High-efficiency synthesis of oligosaccharides with a truncated beta-galactosidase from Bifidobacterium bifidum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2001;57:647–652. doi: 10.1007/s00253-001-0845-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kelly D, King T, Aminov R. Importance of microbial colonization of the gut in early life to the development of immunity. Mutat Res. 2007;622:58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Killer J, Kopecny J, Mrazek J, Koppova I, Havlik J, Benada O, Kott T (2010) Bifidobacterium actinocoloniiforme sp. nov. and Bifidobacterium bohemicum sp. nov., two new bifidobacteria from the bumblebee digestive tracts. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Killer J, Kopecny J, Mrazek J, Rada V, Benada O, Koppova I, Havlik J, Straka J. Bifidobacterium bombi sp. nov., from the bumblebee digestive tract. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2009;59:2020–2024. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.002915-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim JF, Jeong H, Yu DS, Choi SH, Hur CG, Park MS, Yoon SH, Kim DW, Ji GE, Park HS, Oh TK. Genome sequence of the probiotic bacterium Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis AD011. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:678–679. doi: 10.1128/JB.01515-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim M, Kwon T, Lee HJ, Kim KH, Chung DK, Ji GE, Byeon ES, Lee JH. Cloning and expression of sucrose phosphorylase gene from Bifidobacterium longum in E. coli and characterization of the recombinant enzyme. Biotechnol Lett. 2003;25:1211–1217. doi: 10.1023/a:1025035320983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kitaoka M, Tian J, Nishimoto M. Novel putative galactose operon involving lacto-N-biose phosphorylase in Bifidobacterium longum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:3158–3162. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.6.3158-3162.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kiyohara M, Tachizawa A, Nishimoto M, Kitaoka M, Ashida H, Yamamoto K. Prebiotic effect of lacto-N-biose I on bifidobacterial growth. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2009;73:1175–1179. doi: 10.1271/bbb.80697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]