Abstract

Airway smooth muscle (ASM) cells have been reported to contribute to the inflammation of asthma. Because the thiazolidinediones (TZDs) exert anti-inflammatory effects, we examined the effects of troglitazone and rosiglitazone on the release of inflammatory moieties from cultured human ASM cells. Troglitazone dose-dependently reduced the IL-1β–induced release of IL-6 and vascular endothelial growth factor, the TNF-α–induced release of eotaxin and regulated on activation, normal T expressed and secreted (RANTES), and the IL-4–induced release of eotaxin. Rosiglitazone also inhibited the TNF-α–stimulated release of RANTES. Although TZDs are known to activate peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor-γ (PPARγ), these anti-inflammatory effects were not affected by a specific PPARγ inhibitor (GW 9662) or by the knockdown of PPARγ using short hairpin RNA. Troglitazone and rosiglitazone each caused the activation of adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK), as detected by Western blotting using a phospho-AMPK antibody. The anti-inflammatory effects of TZDs were largely mimicked by the AMPK activators, 5-amino-4-imidazolecarboxamide ribose (AICAR) and metformin. However, the AMPK inhibitors, Ara A and Compound C, were not effective in preventing the anti-inflammatory effects of troglitazone or rosiglitzone, suggesting that the effects of these TZDs are likely not mediated through the activation of AMPK. These data indicate that TZDs inhibit the release of a variety of inflammatory mediators from human ASM cells, suggesting that they may be useful in the treatment of asthma, and the data also indicate that the effects of TZDs are not mediated by PPARγ or AMPK.

Keywords: shRNA, anti-inflammatory, PPARγ, IL-1β, TNF-α

CLINICAL RELEVANCE.

The results of this study indicate that two classes of drugs used to treat diabetes also inhibit the release of inflammatory mediators from human airway smooth muscle cells, suggesting that these drugs may be useful in the treatment of asthma.

Airway inflammation is a key feature of asthma. The airways of asthmatic patients are infiltrated with lymphocytes and eosinophils, and the expression of numerous cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors is elevated (1–3). An increasing body of evidence suggests that airway smooth muscle (ASM) cells contribute to the production of these inflammatory mediators. Upon activation, cultured human ASM (HASM) cells secrete large amounts of eotaxin, regulated on activation, normal T expressed and secreted (RANTES), IL-6, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), IL-8, monocyte chemoattractant protein–1 (MCP-1), MCP-2, and MCP-3 (4–7). In vivo, the expression of eotaxin is increased in guinea-pig ASM after allergen challenge (8), and both eotaxin and RANTES are highly expressed in the smooth muscle layer of the airways in patients with asthma (3, 4, 9). A recent study also showed that the mediators produced by human ASM promoted the differentiation of eosinophils from blood progenitor cells (10). Thus, ASM is an important component in the airway inflammation of asthma, and inhibiting the inflammatory activity of these cells could be beneficial in the treatment of asthma.

A group of synthetic compounds called thiazolidinediones (TZDs) that includes troglitazone, rosiglitazone, pioglitazone, and ciglitazone are extensively used as oral antidiabetic agents because of their insulin-sensitizing actions (11). However, emerging evidence indicates that this class of drugs also has potent anti-inflammatory effects. In vitro, these drugs inhibit the release of various cytokines from activated lymphocytes (12), monocytes (13), endothelial cells (14), microglia, and Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate-differentiated THP-1 cells (a human monocytic cell line) (15). In vivo, rosiglitazone and pioglitazone also effectively inhibit airway inflammation in various murine models of asthma (16, 17). Most importantly, in a recent clinical trail, the inhalation of rosiglitazone improved lung function, and also reduced sputum IL-8 concentrations in steroid-resistant patients with asthma (18). In cultured HASM cells, troglitazone was shown to attenuate the TNF-α–induced production of eotaxin and MCP-1 expression (19), whereas ciglitazone prevented the IL-1β–induced production of granulocyte-macrophage colony–stimulating factor and granulocyte–colony stimulating factor (20). Thus this inhibitory effect of TZDs on airway inflammation may in part be mediated through effects on ASM. However, the extent to which TZDs can inhibit the effects of other proinflammatory stimuli and the release of other cytokines and chemokines remains to be established. To address this issue, we examined the effects of troglitazone and rosiglitazone on TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-4–stimulated IL-6, VEGF, RANTES, and eotaxin release from cultured HASM cells.

TZDs are high-affinity ligands for peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor-γ (PPARγ), a transcription factor that belongs to the nuclear receptor superfamily. Studies in other cell types, using a potent, specific, and irreversible PPARγ antagonist, GW 9662 (21), revealed anti-inflammatory effects of TZDs that were PPARγ-dependent (22, 23). PPARγ is constitutively expressed in HASM cells (20, 24), and its expression is increased in patients with asthma (25). PPARγ was proposed to mediate the anti-inflammatory effects of TZDs in HASM cells (19, 20). To test this hypothesis, we treated HASM cells with GW 9662 before the addition of troglitazone or rosiglitazone. We also examined the effects of the short hairpin RNA (shRNA) knockdown of PPARγ on the responses to these TZDs. Surprisingly, we observed no role of PPARγ in the anti-inflammatory effects of TZDs. Consequently, we examined the hypothesis that adenosine monophosphate-activated kinase (AMPK), a key cellular energy sensor and regulator, may contribute to the anti-inflammatory effects of TZDs. We considered a role for AMPK because (1) TZDs can activate AMPK (26, 27), and (2) the activation of AMPK by 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleoside (AICAR) or by metformin inhibits inflammatory cytokine production from other cell types (28–34). In vivo, AICAR is also effective at alleviating inflammation in experimental murine colitis (35) and models of asthma (36). To examine the role of AMPK, we measured the TZD-induced activation of AMPK in HASM, assessed the ability of AMPK agonists to mimic the effects of TZDs, and determined the ability of two AMPK inhibitors, Ara A and Compound C, to block the effect of TZDs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

HASM cells were isolated and cultured as previously reported (37). All experiments were performed under serum-free, hormone-supplemented conditions, as described elsewhere (37). Cells from passages 3–6 were used in this study.

Treatment with Cytokines

Cells were grown to confluence and serum-starved for 24 hours. Cells were then treated with recombinant human IL-1β, IL-4, or TNF-α (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Troglitazone (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO), rosiglitzone (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), AICAR (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), and metformin (Sigma Chemical Co.) were added 1 hour before the cytokines. GW 9662 (Cayman Chemical) and the AMPK antagonists, adenine 9-β-D-arabinofuranoside (Ara-A; Sigma), and Compound C (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), were added 1 hour before the TZDs. Supernatants were collected 24 hours after stimulation with cytokine.

ELISA

ELISA assays for VEGF, IL-6, RANTES, and eotaxin were performed using Duoset ELISAs (R&D Systems), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cytokine concentrations were normalized to cell numbers in the same well (assessed by the crystal violet technique (38); see the online supplement for details).

Western Blotting

The activation of AMPK was assessed by its phosphorylation at Thr172, using AMPKα and phospho-AMPKα (Thr172) antibodies (Cell Signaling) (see online supplement for details). The phosphorylation of Thr172 is required for the kinase activity of AMPK (39, 40). Similarly, the activation of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) was assessed by its phosphorylation, using a phospho-specific antibody (Cell Signaling) (41, 42).

PPARγ shRNA

Short hairpin RNA against human PPARγ (the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) accession number NM_138712) was delivered via vectors in lentivirus particles (Mission Lentiviral Transduction Particles; Sigma Chemical Co.) (see online supplement for details). Four shRNA constructs targeting different regions of the gene sequence were used to ensure optimized knockdown. A nontargeting shRNA construct was used as a negative control. For RNA interference Consortium (TRC) clone numbers and sequences, see the online supplement. After transduction, stable cell lines expressing the shRNAs were selected with puromycin and expanded in 6-well plates. The level of PPARγ knockdown was assessed by Taqman, using primers from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase as the normalization control.

Activation of Nuclear Factor–κB

Cytosolic and nuclear fractions of HASM cells were prepared as described by others (43) (see online supplement for details). Protein (10 μg) from each sample was separated on 10% Tris-glycine gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and immunoblotted with nuclear factor (NF)–κB p65 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) or β-actin (Cell Signaling) antibodies.

Glucocorticoid-Responsive Element–Dependent Luciferase Reporter Transfection

HASM cells were transfected with 5 μg of a glucocorticoid-responsive element–dependent luciferase reporter (GRE-luc) (Clontech, Mountain View, CA), as previously described (44). Cells were either left untreated, or treated with troglitazone, dexamethasone (DEX), or DEX and troglitazone together. Cells were harvested, and luciferase was measured (44) 1 hour later.

Statistical Analysis

The effects of TZDs and of the inhibitors or shRNA knockdown were assessed according to one-way ANOVA or factorial ANOVA. The Fisher's Least Significant Difference test was used for post hoc comparisons. Student t tests were used to confirm the effects of cytokines compared with untreated cells. Statistical analyses were performed with Statistica 6 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Results are presented as mean ± SE. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

TZDs Inhibit the Release of Inflammatory Mediators from HASM Cells

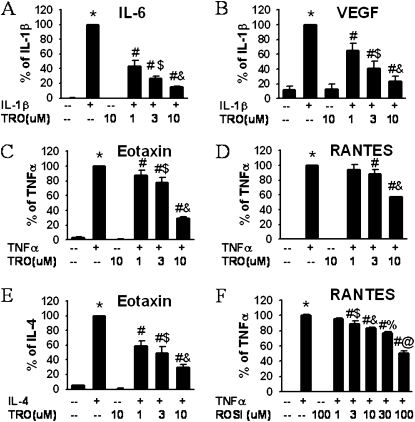

To evaluate the effects of TZDs, cells were stimulated with IL-1β, TNF-α, or IL-4 in the presence or absence of TZDs. Unstimulated HASM cells produced small amounts of IL-6, VEGF, eotaxin, and RANTES (Figures 1A–1F). Troglitazone and rosiglitazone at the maximum dose used here did not affect this baseline secretion (Figures 1A–1F). IL-1β (1 ng/ml) caused a significant increase in the production of IL-6 and VEGF. Troglitazone significantly inhibited this release at a 1-μM concentration, and even further at 3 μM and 10 μM (Figures 1A and 1B). Statistical analyses confirmed that this inhibition was dose-dependent. To confirm that the anti-inflammatory effect of TZDs was not stimulus-specific, we activated cells with two other cytokines, TNF-α and IL-4. TNF-α (10 ng/ml) markedly increased the release of eotaxin (Figure 1C) and RANTES (Figure 1D), and again these increases were inhibited by troglitazone in a dose-dependent manner. IL-4 (3 ng/ml) also induced the release of eotaxin, and this induction was attenuated by troglitazone (Figure 1E). To determine if other TZDs exerted similar effects, we repeated a limited number of these experiments using rosiglitazone. Consistent with the results from troglitazone, rosiglitazone also inhibited the TNF-α–induced release of RANTES, albeit over a somewhat higher dose range (1–100 μM) (Figure 1F). Neither rosiglitazone nor troglitazone had any effect on cell viability, as assessed by Trypan blue staining (data not shown). Taken together, the data indicate that TZDs exert broad anti-inflammatory effects in HASM cells, inhibiting the release of multiple mediators in response to multiple stimuli.

Figure 1.

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs) dose-dependently reduced the release of inflammatory mediators from human airway smooth muscle (HASM) cells. ELISA results are from HASM cell supernatants collected 24 hours after stimulation with IL-1β (1 ng/ml) (A, B), TNF-α (10 ng/ml) (C, D, F), or IL-4 (3 ng/ml) (E). Cells were treated with troglitazone (TRO) (A–E) or rosiglitazone (ROSI) (F). Results are presented as mean ± SE of data from cells from three or four donors, and under each condition, experiments were performed in triplicate or quadruplicate. Values were normalized to cell numbers in each well. *P < 0.05 compared with untreated cells. #P < 0.05 compared with cells treated with stimulator (IL-1β, IL-4, or TNF-α) alone. $P < 0.05 compared with cells treated with IL-1β or TNF-α plus 1 μM or 3 μM troglitazone, respectively. %,@P < 0.05 compared with cells treated with TNF-α plus 10 μM or 30 μM rosiglitazone, respectively. RANTES, regulated on activation, normal T expressed and secreted; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Role of PPARγ

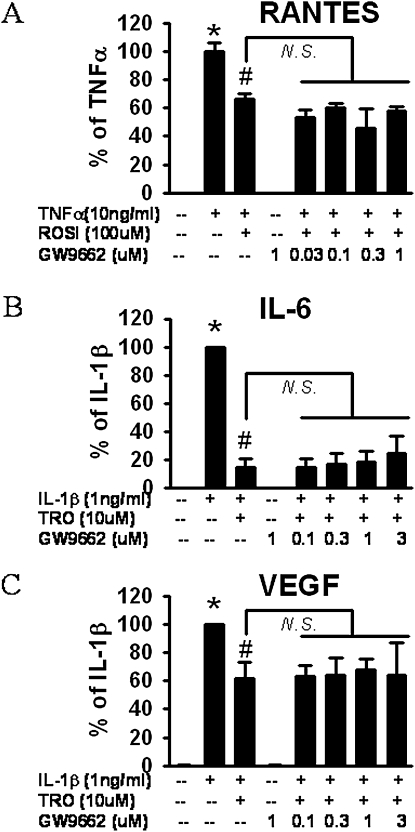

Because TZDs are high-affinity ligands for PPARγ (45, 46), we tested whether the anti-inflammatory effects of troglitazone and rosiglitazone on HASM cells were mediated by PPARγ. We used a potent and specific PPARγ antagonist, GW 9662 (21). Because 1 μM of GW8662 inhibits more than 90% of PPARγ-induced monocyte differentiation to osteoclasts (47), we chose to use this dose. Again, TNF-α dramatically increased the release of RANTES from HASM (Figure 2A), and this increase was significantly blocked by 100 μM rosiglitazone. Pretreatment with GW 9662, over a wide range of concentrations (0.03–1 μM), had no effect of the response to rosiglitazone (Figure 2A). Because others used even higher concentrations of GW 9662 to inhibit PPARγ (48), we increased the GW 9662 concentration to 3 μM in subsequent studies with troglitazone, but even at this concentration, GW 9662 failed to block the effects of troglitazone on the IL-1β–induced release of IL-6 or VEGF (Figures 2B and 2C). The data suggest that the anti-inflammatory effects TZDs in HASM are likely not mediated via PPARγ.

Figure 2.

Effect of the proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) inhibitor, GW 9662, on the inhibition of RANTES (A), IL-6 (B), or VEGF (C) release from HASM cells by TZDs, according to ELISA. Increasing doses of GW 9662 were administered 2 hours before stimulation with TNF-α (A) or IL-1β (B, C). Troglitazone (TRO) (A, B) or rosiglitazone (ROSI) (C) were added 1 hour before the administration of cytokines. Results are presented as mean ± SE of data from three donors; each studied in duplicate, and normalized to cell number in each well. *P < 0.05 compared with untreated cells. #P < 0.05 compared with cells treated with IL-1β or TNF-α alone. N.S., no significance.

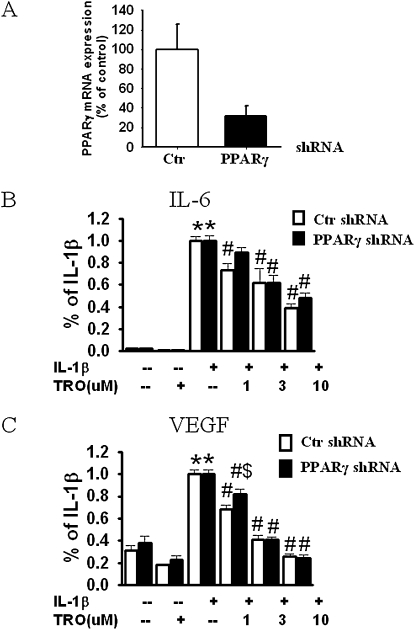

To address the role of PPARγ further, we used RNA interference techniques to knockdown the specific expression of the PPARγ gene, and then examined the effects of TZDs on the release of inflammatory mediators. ShRNA is a sequence of RNA that forms a hairpin structure, and is processed intracellularly into small interference RNA. The lentiviral transduction particle targeting PPARγ gave us an approximately 10–30% transduction efficiency in cultured human ASM, as assessed by the percentage of viable cells after puromycin selection following transduction. The positively transduced cells were expanded for subsequent studies. Four different constructs targeting different regions of the PPARγ gene were used to ensure an optimized knockdown.

All constructs caused a knockdown of PPARγ mRNA expression, as measured by real-time PCR, although their efficacy varied. The average knockdown was 68.6% ± 10.3%, and varied from 84.8% ± 8.26% to 23.6% ± 2.7%, depending on the construct. The data in Figure 3A show the pooled results obtained with all four constructs. As already described, we observed a dose-dependent inhibition of the IL-1β–induced production of IL-6 and VEGF in troglitazone-treated cells. No significant difference in the effects of troglitazone was evident between the PPARγ versus control shRNA-treated cells (Figures 3B and 3C).

Figure 3.

PPARγ knockdown does not prevent the anti-inflammatory effects of TZDs in HASM cells. (A) PPARγ mRNA level in HASM cells that were transduced with lentivirus transduction particles containing nontarget short hairpin RNA (shRNA) (control; Ctr) or PPARγ-target shRNA. Successfully transduced cells were selected by puromycin, expanded, and used in this study. (B, C) Pooled results of all four constructs from two donor cell lines. Results are normalized to maximal release of cytokine with IL-1β stimulation from the same donor treated with control shRNA, and are presented as mean ± SE. *P < 0.05 compared with untreated groups. #P < 0.05 compared with IL-1β–stimulated groups with the same shRNA treatment. $P < 0.05 compared with control shRNA with the same treatment.

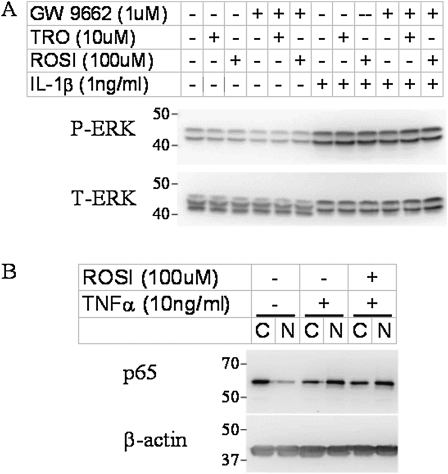

Role of ERK and NF-κB

TZDs may mediate the anti-inflammatory effects on ASM by interfering with the activation of ERK or NF-κB. Rosiglitazone suppresses TNF-α and IFN-γ induced phosphorylation of ERK in human microvascular endothelial cells (14), and ERK is known to be required for the induction of some of the cytokines and chemokines examined in this study (49, 50). To determine whether TZDs exert their anti-inflammatory action in HASM cells via the suppression of ERK, we assessed the phosphorylation of ERK in cells stimulated with IL-1β in the presence or absence of TZDs (Figure 4A). Our data show that troglitazone, rosiglitazone, and GW 9662 alone did not change the phosphorylation of ERK. Stimulation with IL-1β for 15 minutes dramatically increased the phosphorylation of ERK. The choice of this time point was based on previous observations (51). The increased phosphorylation of ERK was not blocked by pretreatment with either troglitazone or rosiglitazone.

Figure 4.

Representative Western blot shows the effects of TZDs on IL-1β–induced phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) (A) and on TNF-α–induced activation of nuclear factor (NF)–κB (B) in HASM cells. Cells were treated for 15 minutes with IL-1β (A) or for 30 minutes with TNF-α (B). TZDs were administered 30 minutes before cytokines, and GW 9662 was administered 30 minutes before TZDs, if used. Twenty micrograms (A) or 10 μg (B) of protein per sample were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE gel. The activation of NF-κB was assessed by p65 translocation from the cytosolic (C) to the nuclear (N) fraction. P-ERK: phosphorylated ERK; T-ERK: total ERK.

Evidence also indicates that TZDs can modulate the activation of NF-κB under some circumstances (52, 53), and the activation of NF-κB by TNF-α and IL-1β is known to play a role in the induction of inflammatory gene expression in HASM cells (54, 55). To determine if the anti-inflammatory effects of TZDs in HASM cells are attributable to their effects on the activation of NF-κB, we assessed the impact of TZDs on the TNF-α–induced translocation of NF-κB p65. NF-κB p65 translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus upon activation, where it induces the transcription of a variety of inflammatory genes (56). Our data (Figure 4B) show that the majority of p65 was in the cytoplasm in untreated cells. Stimulation with TNF-α caused a reduction in cytosolic p65 and an increase in nuclear p65. This translocation was not prevented by rosiglitazone. Similar results were obtained with troglitazone (data not shown). These data indicate that the anti-inflammatory effects of TZDs in HASM are not likely attributable to their modulation of NF-κB activation.

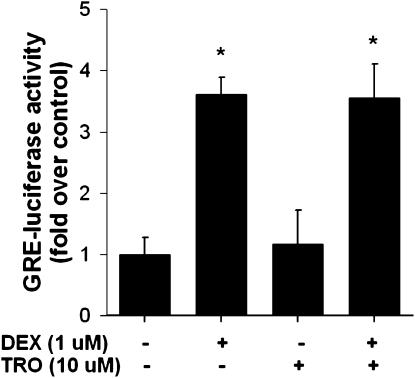

Role of Glucocorticoid Receptor Activation

Because TZDs were shown to be weak agonists of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) (57), we tested the hypothesis that the anti-inflammatory effects of TZDs were mediated via the activation of the GR. Compared with untreated cells, the treatment of HASM cells with DEX caused a robust, approximately 3.5-fold increase in luciferase expression in cells treated with a GRE-dependent luciferase reporter. In contrast, troglitazone had no effect, and did not alter the effects of DEX (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Luciferase expression in untreated HASM cells and in cells treated with dexamethasone (DEX, 1 μM), troglitazone (TRO, 10 μM), or DEX + TRO for 1 hour and transfected with glucocorticoid-responsive element–dependent (GRE) luciferase. Results are presented as mean ± SE of data from three cell wells per treatment. Experiments were performed on cell lines derived from two different donors. *P < 0.05 versus no treatment.

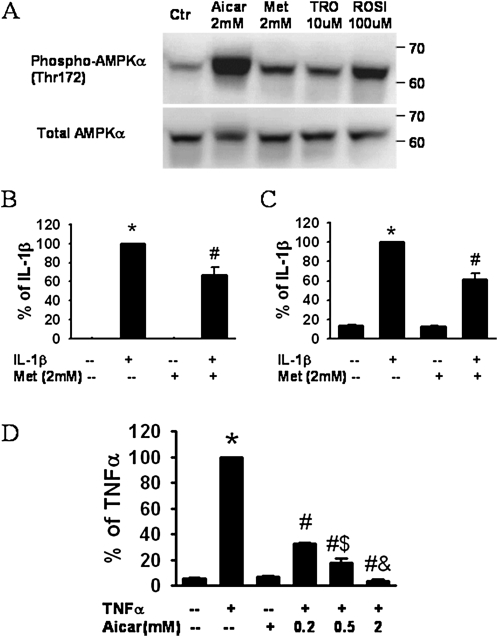

Role of AMPK

Because other studies demonstrated that TZDs can activate AMPK (26, 27), we examined the hypothesis that the anti-inflammatory effects of TZDs on HASM cells are mediated through AMPK. Consistent with previous reports in other cell types, we observed a significant increase in AMPK phosphorylation after treatment with troglitazone (10 μM) or rosiglitazone (100 μM) (Figure 6A), whereas total AMPK was not affected. The AMPK activators, AICAR (58) and metformin (59), were used as positive controls (Figure 6A). To determine whether the activation of AMPK could mimic the effects of TZDs, we also examined the effects of AICAR and metformin on the release of inflammatory mediators. Metformin (2 mM) significantly inhibited the IL-1β–induced release of both IL-6 (Figure 6B) and VEGF (Figure 6C), although it did not affect the basal release of these moieties. Similar results were obtained with AICAR (data not shown). We also examined the effects of AICAR on the TNF-α–induced release of eotaxin (Figure 6D). AICAR had no effect on the basal release of eotaxin from HASM cells, but caused a dose-dependent reduction in the TNF-α–stimulated release of eotaxin.

Figure 6.

(A) Western blot of HASM cell lysates shows phosphorylated and total adenosine monophosphate-activated kinase (AMPK) after incubation with the AMPK agonists, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleoside (AICAR) and metformin (Met), or the TZDs troglitazone (TRO) and rosiglitazone (ROSI). Concentrations of (B) IL-6, (C) VEGF, and (D) eotaxin in HASM cell supernatants collected 24 hours after stimulation with IL-1β (1 ng/ml) (B, C) or TNF-α (10 ng/ml) (D), in the presence or absence of metformin (B, C) or AICAR (D). Results are presented as mean ± SE of data from cells of three donors, each assayed in duplicate and normalized to the cell number in each well. *P < 0.05 compared with untreated cells. #P < 0.05 compared with cells stimulated with IL-1β or TNF-α alone. $P < 0.05 compared with cells stimulated with TNF-α plus 0.2 mM or 0.5 mM AICAR, respectively.

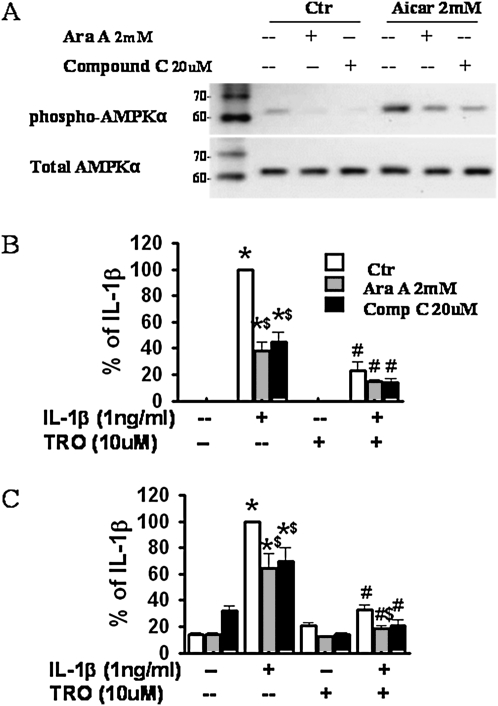

To determine whether the observed effects of TZDs were mediated via the activation of AMPK, we treated cells with two chemically dissimilar AMPK inhibitors, Ara A (2 mM) (60) and Compound C (20 μM) (59), before the administration of TZDs. One hour of pretreatment with Ara A or Compound C significantly reduced both the basal and AICAR-induced phosphorylation of AMPK (Figure 7A), confirming the efficacy of these inhibitors. However, neither Ara A nor Compound C reversed the ability of troglitazone to suppress the IL-1β–induced release of IL-6 (Figure 7B) and VEGF (Figure 7C). Interestingly, in the absence of troglitazone, both Ara A and Compound C reduced the IL-1β–induced release of IL-6 (Figure 7B) and VEGF (Figure 7C), indicating that either elevated (Figures 6B–6D) or reduced (Figures 7B and 7C) activation of AMPK can affect the release of inflammatory moieties from HASM, and suggesting the existence of an optimal energy state for the inflammatory potential of these cells. Neither AICAR, metformin, Ara A, nor Compound C had any effect on cell numbers (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Effects of the AMPK inhibitors, Ara A and Compound C, on the release of proinflammatory mediators from HASM cells. (A) Representative Western blot shows phosphorylated and total AMPK in lysates of control HASM cells and cells treated with the AMPK agonist, AICAR, in the presence or absence of AMPK inhibitors Ara A and Compound C. (B, C) ELISA results for IL-6 (B) and VEGF (C) in supernatants of HASM cells treated with IL-1β and/or troglitazone (TRO), in the presence or absence of Ara A and Compound C. Results are presented as mean ± SE of data from cells of three donors, each studied in duplicate. *P < 0.05 compared with untreated groups. #P < 0.05 compared with IL-1β–treated groups with the same AMPK inhibitors (Ara A and Compound C). $P < 0.05 compared with cells with IL-1β alone or IL-1β plus 10 μM TRO treatment.

DISCUSSION

Our data indicate that the TZDs, troglitazone and rosiglitazone, cause a dose-dependent inhibition of the release of inflammatory mediators from HASM cells. However, these anti-inflammatory effects are likely not mediated through PPARγ, and they do not involve the inhibition of ERK or activation of NF-κB. Our data also indicate that both troglitazone and rosiglitazone can activate AMPK in HASM cells, and that changes in AMPK activity can affect the inflammatory response of cells. However, our data suggest that the anti-inflammatory effects of TZDs in HASM cells are likely not mediated through the activation of AMPK.

Our results are consistent with a previous study (19) showing that troglitazone reduced the TNF-α–induced production of MCP-1 and eotaxin from HASM. Our study extends those data in several ways (Figure 1). First, we showed that another TZD, rosiglitazone, exerts similar effects. Second, we showed that these TZDs inhibited responses not only to TNF-α, but also to IL-1β and IL-4. Finally, we showed that TZDs also inhibit the release of IL-6, VEGF, and RANTES. Taken together, our results indicate that the anti-inflammatory effects of TZDs in HASM cells are not drug-dependent or stimulus-dependent, suggesting a broad anti-inflammatory effect that may be useful in the treatment of asthma.

In this study, both troglitazone and rosiglitazone exerted anti-inflammatory effects (Figure 1). The dose range over which the TZDs exhibited these effects was similar to what was reported in other studies of the anti-inflammatory effects of TZDs (14, 61). However, at equal concentrations, troglitazone was somewhat more effective than rosiglitazone (Figure 1). In contrast, rosiglitazone binds to PPARγ at approximately 100-fold lower concentrations than troglitazone (46), suggesting that the anti-inflammatory effects of these TZDs in HASM are not mediated by their binding to PPARγ. Data using the specific PPARγ antagonist, GW 9662, also support a PPARγ-independent role for troglitazone and rosiglitazone in inhibiting the release of inflammatory mediators from HASM cells (Figure 2). GW 9662 irreversibly binds with PPARγ through the covalent modification of Cys285 in the ligand-binding domain, and decreases its function (21). GW 9662 completely antagonizes rosiglitazone-induced gene transcription in a cell-based reporter assay, as well as adipocyte differentiation in cell culture (21). However, in our study, using a concentration that was previously reported to cause a substantial inhibition of PPARγ-mediated events (62), GW 9662 did not reverse the ability of troglitazone or rosiglitazone to suppress the IL-1β–induced or TNF-α–induced release of inflammatory mediators from HASM cells (Figure 2). To confirm these results, we knocked down PPARγ mRNA expression according to RNA interference techniques, using a lentivirus shRNA delivery system. Our data show that the reduction of PPARγ expression did not affect the ability of troglitazone to inhibit the IL-1β–induced release of IL-6 or VEGF from HASM cells (Figure 3). Other studies also suggest the existence of PPARγ-independent anti-inflammatory effects of TZDs (15). These results are also consistent with data obtained by others using PPARγ-deficient macrophages. In those studies, the deletion of PPARγ did not alter the inhibitory effects of troglitazone on the LPS-induced secretion of TNF-α and IL-6 (63, 64). Taken together, the data support the hypothesis that the anti-inflammatory effects of TZDs in HASM cells are independent of PPARγ.

AMPK plays a key role in maintaining cellular energy balance. It is activated in response to decreased intracellular ATP and an elevated AMP/ATP ratio. Its activation restores energy balances by turning on ATP-generating pathways, and turning off ATP-consuming pathways, via the phosphorylation of downstream kinases and important transcription factors (65). Although AMP can dramatically increase its kinase activity (66), other compounds and drugs also activate AMPK. AICAR is an adenosine analogue. It becomes phosphorylated in the cytoplasm to AICAR monophosphate, and mimics the ability of AMP to activate AMPK (67). Metformin activates AMPK (59) without altering the cellular AMP/ATP ratio. Because TZDs were shown to activate AMPK in other systems (26, 27), and because the activation of AMPK can exert anti-inflammatory effects (30), we examined the role of AMPK in the anti-inflammatory effects of TZDs in HASM cells. Consistent with other reports, we observed a phosphorylation of AMPK by rosiglitazone and troglitazone in HASM cells (Figure 6A). Two AMPK agonists, AICAR and metformin, also mimicked the effects of TZDs, inhibiting the release of IL-6, VEGF, and eotaxin (Figures 6B–6D). To our knowledge, this is the first report of the anti-inflammatory effects of these agents in ASM cells.

To examine the role of TZD-induced AMPK activation further, we used two chemically dissimilar inhibitors to block the AMPK pathway, Compound C (59) and Ara A (60), at doses reported by others to inhibit the activation of AMPK (68–71). Both antagonists prevented the AICAR-induced activation of AMPK, as assessed by the Thr172 phosphorylation of AMPK (Figure 7A), indicating that they were active at the concentrations administered. Both compounds were also shown to inhibit the TZD-induced activation of AMPK in other cell types (72, 73). However, they did not reverse the effects of TZDs on the release of inflammatory mediators from HASM cells (Figures 7B and 7C). These data suggest that the effects of TZDs we observed are likely not mediated by AMPK. Surprisingly, our data also show that the two AMPK antagonists, Ara A and Compound C, were anti-inflammatory on their own (Figures 7B and 7C). The inhibition of AMPK leads to cell death (69) and the suppression of proliferation (74) in some cell types, but we did not observe any change in cell numbers during our experiments, indicating that the reduction in the release of inflammatory mediators was not the result of decreased cell numbers. Similar to our observations that AMPK agonists (Figure 6) suppressed as well as AMPK inhibitors suppressed the release of cytokine from HASM cells (Figure 7), others showed that the proliferation of other cell types is blocked by AICAR (75) or by other conditions that lead to the activation of AMPK, such as glucose depletion (76), and also by the AMPK inhibitor Compound C (69, 77). The data suggest an energy optimum that, if disturbed in either direction, impairs cell function. However, the nonspecific effects of these AMPK antagonists were reported elsewhere (78), and we cannot rule out the possibility that such effects may contribute to these apparent anti-inflammatory effects.

Other pathways were also implicated in effects of TZDs. For example, TZDs were shown to be weak agonists of the GR (57). Activation of the GR by DEX involves some anti-inflammatory effects that resemble those of TZDs in HASM cells. For example, DEX (3–10 nM) causes a reduction in the TNF-α–induced release of RANTES and eotaxin that is similar in magnitude to that induced by TRO (10 μM) (55, 79), suggesting that TZDs may mediate their anti-inflammatory effects in HASM via the activation of GR. However, our data do not support such a mechanism of action for TZDs in HASM cells. We found no increase in the GRE-driven expression of luciferase in HASM cells treated with TRO at a concentration that caused a robust inhibition of cytokine and chemokine release (Figure 1), although DEX caused a robust increase (Figure 5). Other data also contradict the idea that TZDs might act via the activation of GR. For example, DEX, even at very high concentrations, causes only a small inhibition of IL-1β stimulated the release of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor from HASM cells, whereas the TZD, ciglitazone, virtually abolished it (20, 54). Similarly, DEX exerts no effect on the IL-13–stimulated release of eotaxin (54), although TRO causes a marked inhibition of the IL-4–induced release of eotaxin (Figure 1).

In conclusion, our data indicate that TZDs inhibit the release of a variety of inflammatory moieties from HASM stimulated with IL-1β, TNF-α, or IL-4, indicating that TZDs exert broad anti-inflammatory effects. These effects appear to be independent of PPARγ. Our data indicate that AMPK agonists also inhibit the release of inflammatory mediators from HASM cells, perhaps by altering energy homeostasis within cells, but that the activation of AMPK by TZDs does not appear to be the major mechanism for their anti-inflammatory effects in HASM cells.

Supplementary Material

This study was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants HL-084044 and HL097032, and by National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences grants ES-013307, ES-00002, and HL-084044 (S.A.S.).

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-04450C on September 24, 2010

Author Disclosure: R.A.P. has served as a scientific consultant for Astra-Zeneca ($1,001–$5,000), Merck ($1,001–$5,000), and GlaxoSmithKline ($1,001–$5,000), has served on scientific advisory boards for BioMarck ($1,001–$5,000), Cytokinetics ($1,001–$5,000), and Epigenesis ($1,001–$5,000), has received lecture fees from Astra-Zeneca ($1,001–$5,000), and has received industry-sponsored grants from Immune Control ($10,001–$50,000), Astra-Zeneca ($10,001–$50,000), and the National Institutes of Health (more than $100,001). S.A.S. has served on an advisory board for Schering Plough ($1,001–$5,000), has received lecture fees from Merck Pharmaceutical Co. ($1,001–$5,000) and Merck Frost Canada (up to $1,000), and has received industry-sponsored grants from the National Institutes of Health (more than $100,001). None of the other authors have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Barnes PJ. The cytokine network in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Invest 2008;118:3546–3556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Afshar R, Medoff BD, Luster AD. Allergic asthma: a tale of many T cells. Clin Exp Allergy 2008;38:1847–1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bousquet J, Chanez P, Lacoste JY, Barneon G, Ghavanian N, Enander I, Venge P, Ahlstedt S, Simony-Lafontaine J, Godard P, et al. Eosinophilic inflammation in asthma. N Engl J Med 1990;323:1033–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghaffar O, Hamid Q, Renzi PM, Allakhverdi Z, Molet S, Hogg JC, Shore SA, Luster AD, Lamkhioued B. Constitutive and cytokine-stimulated expression of eotaxin by human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;159:1933–1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faffe DS, Flynt L, Mellema M, Moore PE, Silverman ES, Subramaniam V, Jones MR, Mizgerd JP, Whitehead T, Imrich A, et al. Oncostatin M causes eotaxin-1 release from airway smooth muscle: synergy with IL-4 and IL-13. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005;115:514–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tliba O, Panettieri RA Jr. Noncontractile functions of airway smooth muscle cells in asthma. Annu Rev Physiol 2009;71:509–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tliba O, Amrani Y, Panettieri RA Jr. Is airway smooth muscle the “missing link” modulating airway inflammation in asthma? Chest 2008;133:236–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li D, Wang D, Griffiths-Johnson DA, Wells TN, Williams TJ, Jose PJ, Jeffery PK. Eotaxin protein and gene expression in guinea-pig lungs: constitutive expression and upregulation after allergen challenge. Eur Respir J 1997;10:1946–1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berkman N, Krishnan VL, Gilbey T, Newton R, O'Connor B, Barnes PJ, Chung KF. Expression of RANTES mRNA and protein in airways of patients with mild asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;154:1804–1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fanat AI, Thomson JV, Radford K, Nair P, Sehmi R. Human airway smooth muscle promotes eosinophil differentiation. Clin Exp Allergy 2009;39:1009–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mauvais-Jarvis F, Andreelli F, Hanaire-Broutin H, Charbonnel B, Girard J. Therapeutic perspectives for type 2 diabetes mellitus: molecular and clinical insights. Diabetes Metab 2001;27:415–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt S, Moric E, Schmidt M, Sastre M, Feinstein DL, Heneka MT. Anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative actions of PPAR-gamma agonists on T lymphocytes derived from MS patients. J Leukoc Biol 2004;75:478–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang C, Ting AT, Seed B. PPAR-gamma agonists inhibit production of monocyte inflammatory cytokines. Nature 1998;391:82–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lombardi A, Cantini G, Piscitelli E, Gelmini S, Francalanci M, Mello T, Ceni E, Varano G, Forti G, Rotondi M, et al. A new mechanism involving ERK contributes to rosiglitazone inhibition of tumor necrosis factor–alpha and interferon-gamma inflammatory effects in human endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2008;28:718–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woster AP, Combs CK. Differential ability of a thiazolidinedione PPARgamma agonist to attenuate cytokine secretion in primary microglia and macrophage-like cells. J Neurochem 2007;103:67–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Narala VR, Ranga R, Smith MR, Berlin AA, Standiford TJ, Lukacs NW, Reddy RC. Pioglitazone is as effective as dexamethasone in a cockroach allergen–induced murine model of asthma. Respir Res 2007;8:90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee KS, Park SJ, Kim SR, Min KH, Jin SM, Lee HK, Lee YC. Modulation of airway remodeling and airway inflammation by peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor gamma in a murine model of toluene diisocyanate–induced asthma. J Immunol 2006;177:5248–5257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spears M, Donnelly I, Jolly L, Brannigan M, Ito K, McSharry C, Lafferty J, Chaudhuri R, Braganza G, Bareille P, et al. Bronchodilatory effect of the PPAR-gamma agonist rosiglitazone in smokers with asthma. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2009;86:49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nie M, Corbett L, Knox AJ, Pang L. Differential regulation of chemokine expression by peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor gamma agonists: interactions with glucocorticoids and beta2-agonists. J Biol Chem 2005;280:2550–2561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel HJ, Belvisi MG, Bishop-Bailey D, Yacoub MH, Mitchell JA. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in human airway smooth muscle cells has a superior anti-inflammatory profile to corticosteroids: relevance for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease therapy. J Immunol 2003;170:2663–2669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leesnitzer LM, Parks DJ, Bledsoe RK, Cobb JE, Collins JL, Consler TG, Davis RG, Hull-Ryde EA, Lenhard JM, Patel L, et al. Functional consequences of cysteine modification in the ligand binding sites of peroxisome proliferator activated receptors by GW9662. Biochemistry 2002;41:6640–6650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo Y, Yin W, Signore AP, Zhang F, Hong Z, Wang S, Graham SH, Chen J. Neuroprotection against focal ischemic brain injury by the peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor–gamma agonist rosiglitazone. J Neurochem 2006;97:435–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu MK, Lee JC, Kim JH, Lee YH, Jeon JG, Jhee EC, Yi HK. Anti-inflammatory effect of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma on human dental pulp cells. J Endod 2009;35:524–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pang L, Nie M, Corbett L, Knox AJ. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in human airway smooth muscle cells: role of peroxisome proliferator–activated receptors. J Immunol 2003;170:1043–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benayoun L, Letuve S, Druilhe A, Boczkowski J, Dombret MC, Mechighel P, Megret J, Leseche G, Aubier M, Pretolani M. Regulation of peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor gamma expression in human asthmatic airways: relationship with proliferation, apoptosis, and airway remodeling. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:1487–1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fryer LG, Parbu-Patel A, Carling D. The anti-diabetic drugs rosiglitazone and metformin stimulate AMP-activated protein kinase through distinct signaling pathways. J Biol Chem 2002;277:25226–25232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.LeBrasseur NK, Kelly M, Tsao TS, Farmer SR, Saha AK, Ruderman NB, Tomas E. Thiazolidinediones can rapidly activate AMP-activated protein kinase in mammalian tissues. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2006;291:E175–E181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Myerburg MM, King Jr JD, Oyster NM, Fitch AC, Magill A, Baty CJ, Watkins SC, Kolls JK, Pilewski JM, Hallows KR. AMPK agonists ameliorate sodium and fluid transport and inflammation in cf airway epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2010. Jun;42(6):676–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jhun BS, Jin Q, Oh YT, Kim SS, Kong Y, Cho YH, Ha J, Baik HH, Kang I. 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide riboside suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced TNF-alpha production through inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT activation in RAW 264.7 murine macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2004;318:372–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao X, Zmijewski JW, Lorne E, Liu G, Park YJ, Tsuruta Y, Abraham E. Activation of AMPK attenuates neutrophil proinflammatory activity and decreases the severity of acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2008;295:L497–L504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peairs A, Radjavi A, Davis S, Li L, Ahmed A, Giri S, Reilly CM. Activation of AMPK inhibits inflammation in MRL/LPR mouse mesangial cells. Clin Exp Immunol 2009;156:542–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giri S, Khan M, Nath N, Singh I, Singh AK. The role of AMPK in psychosine mediated effects on oligodendrocytes and astrocytes: implication for Krabbe disease. J Neurochem 2008;105:1820–1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hattori Y, Suzuki K, Hattori S, Kasai K. Metformin inhibits cytokine-induced nuclear factor kappaB activation via AMP-activated protein kinase activation in vascular endothelial cells. Hypertension 2006;47:1183–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuo CL, Ho FM, Chang MY, Prakash E, Lin WW. Inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-induced inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression by 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide riboside is independent of AMP-activated protein kinase. J Cell Biochem 2008;103:931–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bai A, Yong M, Ma Y, Ma A, Weiss C, Guan Q, Bernstein C, Peng Z. Novel anti-inflammatory action of 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleoside with protective effect in DSS-induced acute and chronic colitis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2010;333:717–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim TB, Kim SY, Moon KA, Park CS, Jang MK, Yun ES, Cho YS, Moon HB, Lee KY. Five-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-beta-4-ribofuranoside attenuates poly (i:C)-induced airway inflammation in a murine model of asthma. Clin Exp Allergy 2007;37:1709–1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Panettieri RA, Murray RK, DePalo LR, Yadvish PA, Kotlikoff MI. A human airway smooth muscle cell line that retains physiological responsiveness. Am J Physiol 1989;256:C329–C335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bosse Y, Thompson C, Stankova J, Rola-Pleszczynski M. Fibroblast growth factor 2 and transforming growth factor beta1 synergism in human bronchial smooth muscle cell proliferation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2006;34:746–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hawley SA, Davison M, Woods A, Davies SP, Beri RK, Carling D, Hardie DG. Characterization of the AMP-activated protein kinase kinase from rat liver and identification of threonine 172 as the major site at which it phosphorylates AMP-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem 1996;271:27879–27887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stein SC, Woods A, Jones NA, Davison MD, Carling D. The regulation of AMP-activated protein kinase by phosphorylation. Biochem J 2000;345:437–443. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderson NG, Maller JL, Tonks NK, Sturgill TW. Requirement for integration of signals from two distinct phosphorylation pathways for activation of MAP kinase. Nature 1990;343:651–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seger R, Krebs EG. The MAPK signaling cascade. FASEB J 1995;9:726–735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Menzies BE, Kenoyer A. Signal transduction and nuclear responses in Staphylococcus aureus–induced expression of human beta-defensin 3 in skin keratinocytes. Infect Immun 2006;74:6847–6854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bhandare R, Damera G, Banerjee A, Flammer JR, Keslacy S, Rogatsky I, Panettieri RA, Amrani Y, Tliba O. Glucocorticoid receptor interacting protein-1 restores glucocorticoid responsiveness in steroid-resistant airway structural cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2010;42:9–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lehmann JM, Moore LB, Smith-Oliver TA, Wilkison WO, Willson TM, Kliewer SA. An antidiabetic thiazolidinedione is a high affinity ligand for peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor gamma (PPAR gamma). J Biol Chem 1995;270:12953–12956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Young PW, Buckle DR, Cantello BC, Chapman H, Clapham JC, Coyle PJ, Haigh D, Hindley RM, Holder JC, Kallender H, et al. Identification of high-affinity binding sites for the insulin sensitizer rosiglitazone (BRL-49653) in rodent and human adipocytes using a radioiodinated ligand for peroxisomal proliferator–activated receptor gamma. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1998;284:751–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bendixen AC, Shevde NK, Dienger KM, Willson TM, Funk CD, Pike JW. IL-4 inhibits osteoclast formation through a direct action on osteoclast precursors via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001;98:2443–2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Polikandriotis JA, Mazzella LJ, Rupnow HL, Hart CM. Peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor gamma ligands stimulate endothelial nitric oxide production through distinct peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor gamma–dependent mechanisms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2005;25:1810–1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moore PE, Church TL, Chism DD, Panettieri RA Jr, Shore SA. IL-13 and IL-4 cause eotaxin release in human airway smooth muscle cells: a role for ERK. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2002;282:L847–L853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wuyts WA, Vanaudenaerde BM, Dupont LJ, Demedts MG, Verleden GM. Involvement of p38 MAPK, Jnk, p42/p44 ERK and NF-kappaB in IL-1beta–induced chemokine release in human airway smooth muscle cells. Respir Med 2003;97:811–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laporte JD, Moore PE, Abraham JH, Maksym GN, Fabry B, Panettieri RA Jr, Shore SA. Role of ERK MAP kinases in responses of cultured human airway smooth muscle cells to IL-1beta. Am J Physiol 1999;277:L943–L951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hisada S, Shimizu K, Shiratori K, Kobayashi M. Peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor gamma ligand prevents the development of chronic pancreatitis through modulating Nf-kappaB–dependent proinflammatory cytokine production and pancreatic stellate cell activation. Rocz Akad Med Bialymst 2005;50:142–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Remels AH, Langen RC, Gosker HR, Russell AP, Spaapen F, Voncken JW, Schrauwen P, Schols AM. PPARgamma inhibits NF-kappaB–dependent transcriptional activation in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2009;297:E174–E183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Birrell MA, Hardaker E, Wong S, McCluskie K, Catley M, De Alba J, Newton R, Haj-Yahia S, Pun KT, Watts CJ, et al. Ikappa-B kinase-2 inhibitor blocks inflammation in human airway smooth muscle and a rat model of asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;172:962–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ammit AJ, Lazaar AL, Irani C, O'Neill GM, Gordon ND, Amrani Y, Penn RB, Panettieri RA Jr. Tumor necrosis factor–alpha–induced secretion of RANTES and interleukin-6 from human airway smooth muscle cells: modulation by glucocorticoids and beta-agonists. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2002;26:465–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Karin M, Ben-Neriah Y. Phosphorylation meets ubiquitination: the control of NF-[kappa]B activity. Annu Rev Immunol 2000;18:621–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Matthews L, Berry A, Tersigni M, D'Acquisto F, Ianaro A, Ray D. Thiazolidinediones are partial agonists for the glucocorticoid receptor. Endocrinology 2009;150:75–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sullivan JE, Brocklehurst KJ, Marley AE, Carey F, Carling D, Beri RK. Inhibition of lipolysis and lipogenesis in isolated rat adipocytes with AICAR, a cell-permeable activator of AMP-activated protein kinase. FEBS Lett 1994;353:33–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhou G, Myers R, Li Y, Chen Y, Shen X, Fenyk-Melody J, Wu M, Ventre J, Doebber T, Fujii N, et al. Role of AMP-activated protein kinase in mechanism of metformin action. J Clin Invest 2001;108:1167–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Henin N, Vincent MF, Van den Berghe G. Stimulation of rat liver AMP-activated protein kinase by AMP analogues. Biochim Biophys Acta 1996;1290:197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guyton K, Zingarelli B, Ashton S, Teti G, Tempel G, Reilly C, Gilkeson G, Halushka P, Cook J. Peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor-gamma agonists modulate macrophage activation by Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacterial stimuli. Shock 2003;20:56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brodbeck J, Balestra ME, Saunders AM, Roses AD, Mahley RW, Huang Y. Rosiglitazone increases dendritic spine density and rescues spine loss caused by apolipoprotein E4 in primary cortical neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008;105:1343–1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moore KJ, Rosen ED, Fitzgerald ML, Randow F, Andersson LP, Altshuler D, Milstone DS, Mortensen RM, Spiegelman BM, Freeman MW. The role of PPAR-gamma in macrophage differentiation and cholesterol uptake. Nat Med 2001;7:41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chawla A, Barak Y, Nagy L, Liao D, Tontonoz P, Evans RM. PPAR-gamma dependent and independent effects on macrophage-gene expression in lipid metabolism and inflammation. Nat Med 2001;7:48–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hardie DG. AMP-activated/Snf1 protein kinases: conserved guardians of cellular energy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2007;8:774–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Suter M, Riek U, Tuerk R, Schlattner U, Wallimann T, Neumann D. Dissecting the role of 5′-AMP for allosteric stimulation, activation, and deactivation of AMP-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem 2006;281:32207–32216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Corton JM, Gillespie JG, Hawley SA, Hardie DG. 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleoside: a specific method for activating AMP-activated protein kinase in intact cells? Eur J Biochem 1995;229:558–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Musi N, Hayashi T, Fujii N, Hirshman MF, Witters LA, Goodyear LJ. AMP-activated protein kinase activity and glucose uptake in rat skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2001;280:E677–E684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vucicevic L, Misirkic M, Janjetovic K, Harhaji-Trajkovic L, Prica M, Stevanovic D, Isenovic E, Sudar E, Sumarac-Dumanovic M, Micic D, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase-dependent and -independent mechanisms underlying in vitro antiglioma action of compound C. Biochem Pharmacol 2009;77:1684–1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hwang JT, Lee M, Jung SN, Lee HJ, Kang I, Kim SS, Ha J. AMP-activated protein kinase activity is required for vanadate-induced hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha expression in Du145 cells. Carcinogenesis 2004;25:2497–2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Katsiougiannis S, Tenta R, Skopouli FN. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase by adiponectin rescues salivary gland epithelial cells from spontaneous and interferon-gamma–induced apoptosis. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:414–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lamontagne J, Pepin E, Peyot ML, Joly E, Ruderman NB, Poitout V, Madiraju SR, Nolan CJ, Prentki M. Pioglitazone acutely reduces insulin secretion and causes metabolic deceleration of the pancreatic beta-cell at submaximal glucose concentrations. Endocrinology 2009;150:3465–3474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bourron O, Daval M, Hainault I, Hajduch E, Servant JM, Gautier JF, Ferre P, Foufelle F. Biguanides and thiazolidinediones inhibit stimulated lipolysis in human adipocytes through activation of AMP-activated protein kinase. Diabetologia 2010;53:768–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Park HU, Suy S, Danner M, Dailey V, Zhang Y, Li H, Hyduke DR, Collins BT, Gagnon G, Kallakury B, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase promotes human prostate cancer cell growth and survival. Mol Cancer Ther 2009;8:733–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rattan R, Giri S, Singh AK, Singh I. 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-beta-D-ribofuranoside inhibits cancer cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo via AMP-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem 2005;280:39582–39593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Okoshi R, Ozaki T, Yamamoto H, Ando K, Koida N, Ono S, Koda T, Kamijo T, Nakagawara A, Kizaki H. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase induces p53-dependent apoptotic cell death in response to energetic stress. J Biol Chem 2008;283:3979–3987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Baumann P, Mandl-Weber S, Emmerich B, Straka C, Schmidmaier R. Inhibition of adenosine monophosphate–activated protein kinase induces apoptosis in multiple myeloma cells. Anticancer Drugs 2007;18:405–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Emerling BM, Viollet B, Tormos KV, Chandel NS. Compound C inhibits hypoxic activation of HIF-1 independent of AMPK. FEBS Lett 2007;581:5727–5731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Seidel P, Merfort I, Hughes JM, Oliver BG, Tamm M, Roth M. Dimethylfumarate inhibits NF-{kappa}B function at multiple levels to limit airway smooth muscle cell cytokine secretion. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2009;297:L326–L339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.