Abstract

There are limited data on the frequency of foregone health service use in defined populations. Here we describe Thai patterns of health service use, types of health insurance used and reports of foregone health services according to geo-demographic and socioeconomic characteristics.

Data on those who considered they had needed but not received health care over the previous year were obtained from a national cohort of 87,134 students from the Sukhothai Thammathirat Open University (STOU). The cohort was enrolled in 2005 and was largely made up of young and middle-age adults living throughout Thailand.

Among respondents, 21.0 percent reported use of health services during the past year. Provincial/governmental hospitals (33.4 percent) were the most attended health facilities in general, followed by private clinics (24.1 percent) and private hospitals (20.1 percent). Health centres and community hospitals were sought after in rural areas. The recently available government operated Universal Coverage Scheme (UCS) was popular among the lower income groups (13.6 percent), especially in rural areas. When asked, 42.1 percent reported having foregone health service use in the past year. Professionals and office workers frequently reported ‘long waiting time’ (17.1 percent) and ‘could not get time off work’ (13.7 percent) as reasons, whereas manual workers frequently noted it was ‘difficult to travel’ (11.6 percent).

This information points to non-financial opportunity cost barriers common to a wide array of Thai adults who need to use health services. This issue is relevant for health and workplace policymakers and managers concerned about equitable access to health services.

INTRODUCTION

Health service use is an important determinant of health status. Thailand is an interesting case among developing countries because of its concern about health inequalities, recently introducing a Universal Coverage Scheme (UCS) to finance access to health services. In order to provide evidence on equity in access to healthcare, studies need to continue to monitor differential health outcomes and the differential use of health services as the Thai universal coverage era unfolds. Lessons learned about the impacts of universal health coverage on health inequalities in Thailand will be useful for other developing countries (Knaul and Frenk 2005; Obermann et al. 2006; Tangcharoensathien et al. 2007; Yiengprugsawan et al. 2007).

There was a health service transition in Thailand before the UCS (Tangcharoensathien and Jongudomsuk 2004). The CSMBS (Civil Servant Benefit Scheme) was established in 1978 covering government or state enterprise employees and their dependents. The SSS (Social Security Scheme) was founded in 1990 as a tripartite contributory scheme among employers, employees and the government. The 1997 Constitution of Thailand states that access to health services is a basic right of Thai citizens. The UCS began in April 2001 as a pilot program and was implemented nationwide by October 2002, covering over 70 percent of the population by 2005. The scheme provides outpatient and inpatient services from primary health care facilities following a referral system. The token UCS service fees were dropped altogether in 2006. A study by the National Health Security Office and ABAC-KSC Internet Poll Research Centre which conducted surveys on perspectives of the scheme among UCS members showed that more than 80 percent reported satisfaction with the UCS (Vasavid et al. 2004).

There are limited studies focusing on the national population in Thailand which report on the numbers of adults who think they need but do not receive healthcare (Damrongplasit and Melnick 2009). Consumer preferences of health service enabled by socioeconomic status explained differences in health service use (Suraratdecha et al. 2005). However, bypassing lower-level health services could result in catastrophic and impoverishing consequences for poorer households (Limwattananon et al. 2007; Somkotra and Lagrada 2009). Using data from our large national Open University cohort, this paper has two objectives: firstly to describe patterns of health service use and types of health insurance used to pay for health services, and secondly to describe patterns of foregone health service use by demographic, socioeconomic and geographic characteristics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data were obtained from 87,134 students from the Sukhothai Thammathirat Open University (STOU) who completed a baseline survey in 2005. The questionnaire covers a wide range of information including demographic-socioeconomic-geographic information on health status, health risk behaviors, social networks, and family background. A detailed description of the study including baseline characteristics of the STOU cohort participants compared to the population of Thailand was already reported elsewhere (Sleigh et al. 2008). STOU has played an important role in Thai development for the last 25 years. Based in Nonthaburi, near Bangkok’s airport, it enrolls approximately 200000 students each year. Of these, 60-70 thousand are new students and the rest have been studying for one semester or more. Overall, 60 percent of students finish their degrees and those that do take on average about 7 years.

Student contact details (names and addresses) were provided by STOU administration after the study reported in newsletter, radio and TV announcements to all students. The students were then contacted by mail. There was no coercion and the STOU President and study leaders reassured the participants that their personal responses were confidential and will never be revealed to others at the individual level or have any influence on academic progress at STOU. The students were motivated by being fully informed about the purposes of the Thai health-risk transition study and that they could contribute to knowledge useful to public health in Thailand. A periodic cohort newsletter provides information back to participants on study progress and any interesting results that emerge. A four year follow-up is underway in 2009.

Information on health service use and health insurance coverage were gathered using the following questions: “In the past 12 months, have you used any health services?” “How did you cover the costs of your medical treatment in the past 12 months?” Multiple responses were allowed. Foregone health service use and reasons for it were also asked: “In the past 12 months, have you considered using health services but did not use them?” “If yes, why did you not use health services?” Multiple responses were allowed. Demographic, socioeconomic, and geographic characteristics were examined.

This study aimed to describe patterns of health insurance and health service use and examine their relation to the following demographic characteristics: age (divided into 5 groups: 15-19, 20-29, 30-29, 40-49 and 50 and over); sex; marital status (married and non-married); socioeconomic characteristics including 6 income brackets (less than 3000, 3001-7000, 7001-10000, 10000-20000, more than 20000 Baht per month); 5 occupations (professionals, managers, office assistants, manual workers, and others), and place of residence (Bangkok, urban and rural areas).

Informed written consent was obtained from all participants, and ethics approval was obtained from Sukhothai Thammathirat Open University Research and Development Institute (protocol 0522/10) and the Australian National University Human Research Ethics Committee (protocol 2004344).

RESULTS

The survey response rate was 44 percent; 54 percent were females and the median age was 29 years. The Planning Division of STOU provided the following information on the first year STOU students in 2005. Students are working Thais and broadly represent the general population: 45 percent were male, 31 percent were married at enrolment, and 95 percent were Buddhist. Age breakdown for was as follows: 14 percent was less than 21 years, 53 percent was 21-30 years, 15 percent was 31-35 years, 16 percent was 36-45 years, and 3.5 percent was more than 45 years. Monthly incomes of STOU students tend to be rather low: less than 3000 Baht (40 Baht = 1USD in 2005) for 21 percent, and with a median of 6000 Baht. The regional profile of STOU students in 2005 reveals that 32 percent lived in greater Bangkok, 4 percent in Central Thailand, 16 percent in the North of the country, 20 percent in the Northeast, 9 percent in the East, 5 percent in the West, and 13 percent in the South.

Table 1 presents the main characteristics of the sample. The majority of students included in the analysis were relatively young, with 80 percent being between 20 and 39 years old. Only 2.5 percent were aged over 50 years. There were more females in the sample and 54.9 percent reported they were not married. Socioeconomic characteristics reported here were monthly income and occupation. Roughly 10 percent of respondents reported earned less than 3 000 Baht per month, half of the sample earned between 3 000 and 10 000 Baht per month. About 10 percent earned more than 20 000 Baht per month. Close to a quarter of respondents reported working as professionals and skilled workers. The majority (31.2 percent) were office assistants. Approximately 15 percent reported their occupation as manual worker. Overall our cohort members have higher incomes than the general population (NSO 2006). Questions on location of residence revealed that 17.2 percent live in Bangkok, 24.5 percent in the Central region, 18.2 percent in the North, 20.9 percent in the Northeastern region, 6.2 percent in the East, and 13.1 percent in the South. Seventeen percent of respondents resided in Bangkok, 36.5 percent in urban areas in other regions and 45.9 percent in rural areas.

Table 1.

Frequency and percentage of demographic, socioeconomic and geographic characteristics among cohort members

| Characteristics of cohort members | Percent | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age (years) | |||

| 15-19 | 2.9 | 2 502 | |

| 20-29 | 50.7 | 44 207 | |

| 30-39 | 31.3 | 27 309 | |

| 40-49 | 12.6 | 10 948 | |

| >=50 | 2.5 | 2 150 | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 45.3 | 39 482 | |

| Female | 54.7 | 47 642 | |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 42.2 | 36 727 | |

| Not-married | 54.9 | 47 843 | |

|

| |||

| Socioeconomic characteristics | |||

| Monthly income (Baht/month) | |||

| <=3000 | 10.8 | 9 372 | |

| 3001-7000 | 30.1 | 26 260 | |

| 7001-10000 | 22.7 | 19 976 | |

| 10001-20000 | 23.6 | 20 564 | |

| >20001 | 10.3 | 8 952 | |

| Occupation | |||

| Professionals/skilled workers | 23.1 | 14 289 | |

| Senior/middle managers | 4.5 | 3 871 | |

| Office assistants | 31.2 | 32 595 | |

| Manual workers | 15.2 | 15 874 | |

| others | 14.4 | 15 061 | |

|

| |||

| Geographic characteristics | |||

| Regions of residence | Bangkok | 17.1 | 14 862 |

| Central | 24.5 | 21 160 | |

| North | 18.2 | 15 750 | |

| Northeast | 20.9 | 18 035 | |

| East | 6.2 | 5 326 | |

| South | 13.1 | 11 292 | |

|

| |||

| Urban not Bangkok | 36.5 | 31 775 | |

| Rural | 45.9 | 39 957 | |

Comparing respondents (44 percent) to the overall STOU students enrolled in 2005, the sex distribution was quite similar. However, approximately 53 percent of cohort members compared to 67 percent of overall STOU students were aged less than 30 years. Approximately 10 percent of cohort members earned less than 3000 Baht per month compared to 20 percent in overall new enrolled STOU students. Another difference was in geographical distribution between the cohort and overall students especially in Bangkok and Central areas (17.1 percent in Bangkok and 24.5 percent in Central) compared to overall newly enrolled STOU students (32 percent in Bangkok and 4 percent in Central Thailand).

Table 2 shows that 78.5 of respondents reporting having used health services during the past 12 months. More than one response of health service use was allowed. Roughly one-thirds reported using provincial/government hospitals (33.4 percent), followed by private clinics (24.1 percent) and private hospitals (21.8 percent). Use of health centres and community hospitals combined was roughly 25 percent. Almost one-thirds of students reported using self-payment (31.6 percent), followed by non-government employers insurance schemes (26.7 percent) and civil servant/state enterprise insurance (24.8 percent). The UCS was used by 13.6 percent of the sample, much lower than among the general population. Foregone use was reported by 42.1 percent of respondents. Reasons reported included: ‘had to wait for too long’ (17.1 percent); ‘could not get time off work’ (13.7 percent); ‘too expensive’ (13.0 percent); and ‘too difficult to travel’ (11.6 percent).

Table 2.

Frequency and percentage of health insurance coverage, use of health services, forgone use and reasons among cohort members

| Use and foregone use of health services | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Use of services | |||

| No | 18 332 | 21.0 | |

| Yes | 68,439 | 78.5 | |

|

|

|||

| Health services | |||

| Government clinics | 4 164 | 4.8 | |

| Community hospitals | 9 359 | 10.7 | |

| Health centres | 12 841 | 14.7 | |

| No services used | 17 541 | 20.1 | |

| Private hospitals | 19 022 | 21.8 | |

| Private clinics | 21 034 | 24.1 | |

| Provincial/government hospitals | 29 078 | 33.4 | |

|

|

|||

| Health insurance | |||

| Private health insurance | 3 653 | 4.2 | |

| Universal Coverage Scheme (UCS) | 11 847 | 13.6 | |

| Civil servant/state enterprise | 21 644 | 24.8 | |

| Non-government employer | 23 232 | 26.7 | |

| Self payment | 27 516 | 31.6 | |

|

| |||

| Foregone use | |||

| No | 36 685 | 42.1 | |

| Yes | 47 472 | 54.5 | |

|

|

|||

| Reasons (if yes) | |||

| Do not like health provider | 2 105 | 2.4 | |

| Could not get away from family | 2 646 | 3.0 | |

| Scared of going | 4 229 | 4.9 | |

| Too expensive | 5 302 | 6.1 | |

| Not satisfied with services | 6 629 | 7.6 | |

| Too difficult to travel | 10 121 | 11.6 | |

| Could not get time off work | 11 926 | 13.7 | |

| Had to wait for too long | 14 905 | 17.1 | |

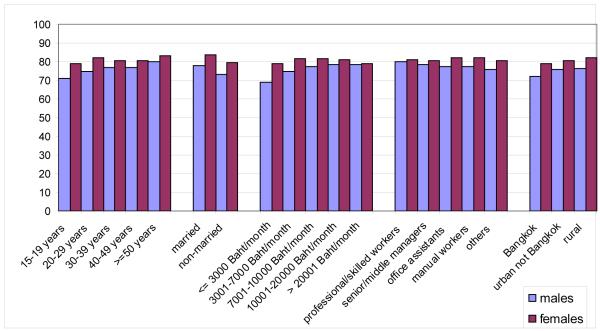

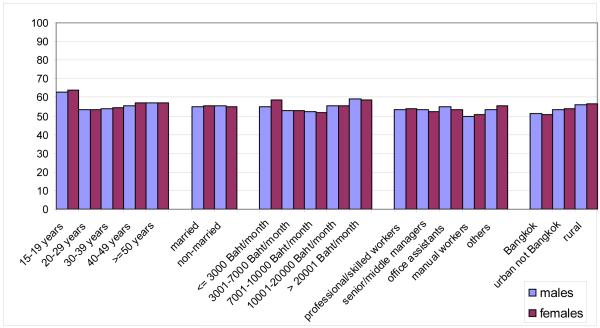

Figure 1 shows that the proportion of those who had used a health service during the past year ranged from 70-82 percent across various socio-economic and demographic groups with females more likely to report using health services across all groups. Overall the similarity in health service use was striking for the various age, income, marital status, occupation and geographic locations compared. However, those in the age range 15-19 years, who are single, have an income lower than 3,000 Baht/month and reside in Bangkok were the least likely to report any health service use compared to other groups. Figure 2 shows that roughly 50-65 percent reported foregone health service use during the past 12 months and the patterns across compared socio-demographic groups showed substantial similarities. However, those in the youngest group, lowest income group and residing in rural areas reported more foregone health service use than other groups. The next section explores further such use of health services by demographic, socioeconomic and geographic characteristics.

Figure 1.

Percentage of health service use by demographic, socioeconomic, geographic characteristics among cohort members

Figure 2.

Percentage of foregone health service use by demographic, socioeconomic, geographic characteristics among cohort members

Table 3 shows that across different age groups, use of provincial/governmental hospitals was the most popular especially in the older age groups (37.8 percent of those aged 40-49 and 41.3 percent of those aged over 50). The youngest age group reported using provincial hospitals (31.0 percent), private clinics (27.3 percent) and health centres (24.4 percent). The use of provincial hospitals and private clinics was strongly associated with income and occupation. The lowest income group used health centres (26.2 percent) more relative to other income groups. On the opposite end, the highest income group had the highest use of private hospitals (34.0 percent of this income group). Office assistants reported using provincial hospitals (36.3 percent) and community hospitals (36.2 percent) almost equally. Geographically, in Bangkok, the use of private hospitals was the most popular (37.8 percent) and provincial/governmental hospitals (36.8 percent) in other urban areas. In rural areas, the use of provincial hospitals (33.1 percent) stood out but the use of health centres (24.1 percent) and community hospitals (17.5 percent) were higher relative to other areas.

Table 3.

Percentage of health service types by demographic, socioeconomic and geographic characteristics among cohort members

| Characteristics | Government clinics |

Community hospitals |

Health centres |

Private hospitals |

Private clinics |

Provincial/ Government hospitals |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Age (years) | 15-19 | 4.3 | 13.9 | 24.4 | 14.5 | 27.3 | 31.0 |

| 20-29 | 4.6 | 11.0 | 16.4 | 23.2 | 27.9 | 32.1 | |

| 30-39 | 4.9 | 10.3 | 13.2 | 21.9 | 20.7 | 33.2 | |

| 40-49 | 5.0 | 10.1 | 10.6 | 18.3 | 17.9 | 37.8 | |

| >=50 | 6.1 | 9.3 | 9.7 | 18.2 | 18.2 | 41.3 | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 4.8 | 10.7 | 14.6 | 18.1 | 19.3 | 35.0 | |

| Female | 4.8 | 10.8 | 14.9 | 24.9 | 28.2 | 32.1 | |

| Status | |||||||

| Married | 4.8 | 11.5 | 14.4 | 21.5 | 22.8 | 36.1 | |

| Non-married | 4.7 | 10.3 | 14.9 | 22.2 | 25.3 | 31.4 | |

|

| |||||||

| Monthly income (Baht/month) |

<=3000 | 5.6 | 15.0 | 26.2 | 10.5 | 25.6 | 31.3 |

| 3001-7000 | 4.9 | 12.1 | 20.6 | 20.2 | 28.5 | 31.5 | |

| 7001-10000 | 4.9 | 9.5 | 11.5 | 24.2 | 23.8 | 35.4 | |

| 10001-20000 | 4.7 | 10.2 | 9.2 | 22.5 | 20.6 | 37.2 | |

| >20000 | 3.4 | 8.4 | 8.6 | 34.0 | 19.4 | 29.1 | |

| Occupation | |||||||

| Professionals and skilled workers |

5.3 | 11.8 | 14.3 | 23.8 | 23.4 | 34.6 | |

| Senior and middle managers |

4.9 | 8.8 | 12.8 | 27.9 | 23.9 | 32.1 | |

| Office assistants | 5.2 | 36.2 | 13.7 | 22.1 | 23.9 | 36.3 | |

| Manual workers | 4.7 | 19.5 | 17.9 | 26.1 | 26.0 | 30.0 | |

| Others | 4.2 | 18.2 | 16.5 | 19.6 | 24.9 | 33.2 | |

|

| |||||||

| Areas | |||||||

| Bangkok | 5.1 | 1.8 | 4.4 | 37.8 | 20.8 | 26.7 | |

| Urban not Bangkok | 5.2 | 6.4 | 7.7 | 24.4 | 24.4 | 36.8 | |

| Rural | 4.3 | 17.5 | 24.1 | 13.9 | 25.2 | 33.1 | |

Table 4 shows that across age groups, the youngest age group had a majority reporting using self-payment possibly financed by parents (38.3 percent), the UCS (36.0 percent), or civil servant/state enterprise insurance schemes (27.8 percent) which also include dependents. In the lowest income group, 41.4 percent used the UCS, followed by self-payment (37.0 percent). In the middle income groups, 37.6 percent of those who earned 3001-7000 Baht/month and 33.1 percent of those who earned 7001-10000/month used non-governmental employer schemes. For those in higher income groups 44.1 percent of those earning 10001-20000 and 35.1 percent of those earning more than 20000 Baht/month used the civil servant/state enterprise scheme. Across all the geographic areas, self-payment was the most prominent payment method, followed by non-government employer beneficiaries; 32.7 percent in Bangkok and 27.7 percent in urban areas. For cohort members residing in rural areas the UCS constituted almost 20 percent of health service payments.

Table 4.

Percentage of health insurance usage by demographic, socioeconomic and geographic characteristics among cohort members

| Characteristics | Private health insurance |

UCS | Civil servant/ State enterprise |

Non-government employer |

Self payment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Age (years) | 15-19 | 3.6 | 36.0 | 8.8 | 10.9 | 38.3 |

| 20-29 | 3.7 | 17.6 | 15.4 | 32.9 | 33.7 | |

| 30-39 | 4.9 | 8.2 | 32.9 | 24.4 | 28.6 | |

| 40-49 | 4.8 | 6.9 | 42.5 | 14.3 | 28.4 | |

| >=50 | 3.8 | 8.0 | 44.5 | 8.7 | 33.7 | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 4.3 | 13.2 | 30.4 | 20.6 | 26.8 | |

| Female | 4.2 | 14.0 | 20.3 | 31.7 | 35.5 | |

| Status | ||||||

| Married | 4.3 | 8.0 | 36.3 | 24.4 | 29.3 | |

| Non-married | 4.2 | 17.6 | 16.5 | 28.3 | 33.3 | |

|

| ||||||

| Monthly income (Baht/month) |

<=3000 | 3.3 | 41.4 | 5.4 | 6.1 | 37.0 |

| 3001-7000 | 2.6 | 20.2 | 9.8 | 37.6 | 34.3 | |

| 7001-10000 | 3.4 | 6.0 | 31.2 | 33.1 | 28.7 | |

| 10001-20000 | 4.9 | 2.7 | 44.1 | 21.8 | 27.6 | |

| >20000 | 10.3 | 2.9 | 35.1 | 18.6 | 33.4 | |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Professionals and skilled workers |

4.4 | 11.5 | 28.2 | 29.5 | 31.5 | |

| Senior and middle managers |

6.4 | 10.1 | 25.4 | 30.6 | 32.6 | |

| Office assistants | 3.4 | 7.8 | 32.9 | 31.4 | 28.3 | |

| Manual workers | 4.2 | 16.9 | 13.4 | 40.2 | 32.2 | |

| Others | 4.1 | 16.4 | 23.5 | 21.6 | 34.8 | |

|

| ||||||

| Areas | ||||||

| Bangkok | 7.0 | 6.4 | 17.7 | 32.7 | 35.6 | |

| Urban not | 4.6 | 9.2 | 27.4 | 27.7 | 31.0 | |

| Bangkok Rural |

2.8 | 19.7 | 25.4 | 23.6 | 30.6 | |

Cross analysis between types of health services used and the type of health insurance (data not shown here) points out those covered by non-government employer insurance schemes reported using private hospitals (48.8 percent) much more than other types of health services; compared to Civil servant/state enterprise employees who reported the most use of provincial/government hospitals (64.7 percent). Those eligible for private health insurance unsurprisingly were patrons of private hospitals (66.2 percent). For those eligible for the UCS, health facilities used were those in the public sector such as provincial/government hospitals (46.4 percent) and health centres (44.6 percent). Those with self-payment sought most services from private clinics (53.3 percent).

Table 5 reveals the principle reasons for not using health services. Across age groups, those in the prime working age (20-39 years) as well as females reported their reason for not using health services as ‘long waiting time’ and ‘could not get time off work’. However, ‘could not get time off work’ was reported at a particularly low rate by those in the lowest income group (2-3 times less than other income group). Across income groups, the proportion of those reporting reasons being ‘too expensive’ and ‘difficult to travel’ were high among lowest income group but generally declined as income increased.

Table 5.

Percentage of reasons* for not using health services by demographic, socioeconomic and geographic characteristics among cohort members

| Characteristics | Too expensive | Not satisfied with services |

Difficult to travel |

Could not get time off work |

Long waiting time |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Age (years) | 15-19 | 6.1 | 4.8 | 9.8 | 9.6 | 11.8 |

| 20-29 | 6.8 | 8.0 | 12.9 | 15.5 | 17.1 | |

| 30-39 | 5.4 | 7.9 | 10.6 | 12.6 | 17.8 | |

| 40-49 | 5.1 | 6.2 | 9.5 | 11.2 | 16.9 | |

| >=50 | 4.9 | 5.5 | 10.0 | 7.5 | 16.5 | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 5.7 | 7.9 | 11.8 | 12.3 | 16.8 | |

| Female | 6.4 | 7.4 | 11.5 | 14.9 | 17.3 | |

| Status | ||||||

| Married | 5.2 | 7.5 | 10.0 | 12.9 | 17.6 | |

| Non-married | 6.7 | 7.7 | 12.8 | 14.3 | 16.6 | |

|

| ||||||

| Monthly income (Baht/month) |

<=3000 | 7.8 | 8.4 | 12.5 | 5.1 | 17.2 |

| 3001-7000 | 7.2 | 8.1 | 12.1 | 15.4 | 17.8 | |

| 7001-10000 | 5.9 | 8.0 | 12.6 | 16.5 | 18.1 | |

| 10001-20000 | 5.0 | 7.0 | 10.8 | 14.4 | 16.8 | |

| >20000 | 4.3 | 5.5 | 9.5 | 12.6 | 14.0 | |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Professionals and skilled workers |

6.8 | 8.4 | 12.3 | 17.1 | 18.8 | |

| Senior and middle managers |

6.5 | 8.7 | 12.3 | 15.2 | 18.4 | |

| Office assistants | 6.0 | 7.5 | 11.9 | 16.6 | 17.9 | |

| Manual workers | 7.8 | 9.1 | 13.4 | 16.7 | 18.4 | |

| Others | 6.3 | 7.4 | 11.1 | 11.8 | 16.6 | |

|

| ||||||

| Areas | ||||||

| Bangkok | 8.9 | 7.4 | 13.6 | 15.6 | 16.6 | |

| Urban not Bangkok | 6.3 | 7.8 | 10.9 | 14.1 | 18.1 | |

| Rural | 4.9 | 7.6 | 11.5 | 12.7 | 16.5 | |

includes the five most common reasons reported

‘Long waiting time’ (e.g., 18.8 percent in professionals and skilled workers) and ‘could not get time-off work’ (e.g., 17.1 percent in professionals and skilled workers) were the two primary reasons across all occupation groups. For manual workers, however, reporting reasons of ‘too expensive’ and ‘difficult to travel’ were much higher than for other occupational groups. Bangkok and other urban residents often report not using health services due to ‘long waiting time’ and ‘could not get time off work’.

DISCUSSION

The STOU cohort data have the advantage of being large, national and representative of a dynamic, young and middle-age section of Thai society. This group exhibits a wide range of health status, health risk behaviours and health service use so allowing us to explore the association of different outcomes over time. The STOU cohort was socioeconomically a little better-off than the general Thai population, which is also shown in the pattern of health insurance and types of health service use. The cohort is also more highly educated than the general population (Open University students) giving them access to more health-related information. On the use of health services, provincial/governmental hospitals were the most attended health facilities in general, followed by private clinics and private hospitals especially in the higher income groups. Health centres and community hospitals, which were associated with the UCS policy, were sought after in rural areas. Self-payment was the most reported health insurance-related payment. Provincial/government hospitals were particularly utilised by those having Civil servant/state enterprise insurance and private hospitals by those covered by non-governmental employer schemes.

Our findings add to the limited literature on foregone use of health services. Long waiting time, inability to get time off work, and difficulty of travel were major reasons for reporting foregone health service use. This information pointed to continuing barriers in use of health services in Thailand. This study highlighted time pressure and opportunity cost as main reasons for foregone health service use. Other studies have also shown that time pressure, with longer work hours and faster work pace, creates disincentives for uptake of health services (Parslow et al. 2004; D’Souza et al. 2005; Strazdins and Loughrey 2007). School-age populations also forego care and barriers for them can include lack of information, lack of access, and poor insurance coverage (Elliott and Larson 2004). Those older aged, minorities, single parents, and disabled persons also forego care due to sociophysical barriers (Ford et al. 1999). A study in China also found that increased travel distance and time could lead to decreased visits to specialists and an increasing reliance on generalists (Chan et al. 2006). Individual and household characteristics thus could explain the pattern of foregone health service use.

There are some cautious notes regarding representation of cohort members and interpretation of results. Cohort members are a subset of STOU students with some differences in geo-demographic distribution. The cohort members also might not represent the Thai population but do shed some light on middle aged adults and their challenges regarding foregone health service use. Despite most cohort members having health insurance, self-payment constitute one-third in method of payment. As there is no information on seriousness of illness, we speculate these to be minor illnesses that some foregone illness episode may have been of a minor nature.

Both use and foregone use of health services reflect the multidimensional nature of socioeconomic status (occupation, income, and education). This study has shown that health service use was associated with types of health insurance which related to occupation types. However, barriers to use of health services included ability to pay as well as opportunity costs such as travel time as reported by manual workers. In addition for professionals and other office workers, long waiting time and inability to get time off work prevented them from using health services. As Thailand’s UCS progresses in its coverage, research could usefully extend the focus on other non-financial barriers such as cost of travelling and long waiting time which might prevent the use of health services when needed. Use of services not covered by the UCS benefit package, and bypassing of designated providers, are known to be major causes of catastrophic expenditures and impoverishment (Limwattananon et al. 2007). For policymakers, this paper has highlighted the need to pay attention to non-financial barriers to ensure equitable access to healthcare for the diverse Thai working population.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the International Collaborative Research Grants Scheme with joint grants from the Wellcome Trust UK (GR071587MA) and the Australian NHMRC (268055). We thank the staff at Sukhothai Thammathirat Open University (STOU) who assisted with student contact and the STOU students who are participating in the cohort study. We also thank Dr Bandit Thinkamrop and his team from Khon Kaen University for guiding us successfully through the complex data processing. Also thanks to Matthew Kelly for language editing of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Chan L, Hart LG, Goodman DC. Geographic access to health care for rural Medicare beneficiaries. J Rural Health. 2006;22(2):140–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2006.00022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza RM, Strazdins L, Clements MS, Broom DH, Parslow R, Rodgers B. The health effects of jobs: status, working conditions, or both? Aust N Z J Public Health. 2005;29(3):222–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2005.tb00759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damrongplasit K, Melnick GA. Early results from Thailand’s 30 Baht Health Reform: something to smile about. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(3):w457–66. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.w457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott BA, Larson JT. Adolescents in mid-sized and rural communities: foregone care, perceived barriers, and risk factors. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35(4):303–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford CA, Bearman PS, Moody J. Foregone health care among adolescents. Jama. 1999;282(23):2227–34. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaul FM, Frenk J. Health insurance in Mexico: achieving universal coverage through structural reform. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24(6):1467–76. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.6.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limwattananon S, Tangcharoensathien V, Prakongsai P. Catastrophic and poverty impacts of health payments: results from national household surveys in Thailand. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85(8):600–6. doi: 10.2471/BLT.06.033720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NSO . Key statistics of Thailand 2006. National Statistical Office; Bangkok: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Obermann K, Jowett MR, Alcantara MO, Banzon EP, Bodart C. Social health insurance in a developing country: the case of the Philippines. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(12):3177–85. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parslow RA, Jorm AF, Christensen H, Broom DH, Strazdins L, D’Souza RM. The impact of employee level and work stress on mental health and GP service use: an analysis of a sample of Australian government employees. BMC Public Health. 2004;4:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-4-41. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-4-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleigh AC, Seubsman SA, Bain C. Cohort profile: The Thai Cohort of 87,134 Open University students. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37(2):266–72. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somkotra T, Lagrada LP. Which households are at risk of catastrophic health spending: experience in Thailand after universal coverage. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(3):w467–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.w467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strazdins L, Loughrey B. Too busy: why time is a health and environmental problem. N S W Public Health Bull. 2007;18(11-12):219–21. doi: 10.1071/nb07029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suraratdecha C, Saithanu S, Tangcharoensathien V. Is universal coverage a solution for disparities in health care? Findings from three low-income provinces of Thailand. Health Policy. 2005;73(3):272–84. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangcharoensathien V, Jongudomsuk P, editors. From policy to implementation: historical events during 2001-2004 of universal coverage in Thailand. National Health Security Office; Nonthaburi: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tangcharoensathien V, Limwattananon S, Prakongsai P. Improving health-related information systems to monitor equity in health: lessons from Thailand. In: McIntyre D, Mooney G, editors. The Economics of Health Equity. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vasavid C, Tisayaticom K, Patcharanarumol W, Tangcharoensathien V. Impact of universal health care coverage on the Thai households. In: Tangcharoensathien V, Jongudomsuk P, editors. From Policy to Implementation: historical events during 2001-2004 of universal coverage in Thailand. National Health Security Office; Nonthaburi: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Yiengprugsawan V, Lim LL-Y, Carmichael GA, Sidorenko A, Sleigh ACS. Measuring and decomposing inequity in self-reported morbidity and self-assessed health in Thailand. Int J Equity Health. 2007;6(1):23. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-6-23. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-6-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]