Abstract

Air, sea and land transport networks continue to expand in reach, speed of travel and volume of passengers and goods carried. Pathogens and their vectors can now move further, faster and in greater numbers than ever before. Three important consequences of global transport network expansion are infectious disease pandemics, vector invasion events and vector-borne pathogen importation. This review briefly examines some of the important historical examples of these disease and vector movements, such as the global influenza pandemics, the devastating Anopheles gambiae invasion of Brazil and the recent increases in imported Plasmodium falciparum malaria cases. We then outline potential approaches for future studies of disease movement, focussing on vector invasion and vector-borne disease importation. Such approaches allow us to explore the potential implications of international air travel, shipping routes and other methods of transport on global pathogen and vector traffic.

1. Introduction

For most of human history, regional and continental populations have been relatively isolated from each other. Only comparatively recently has there been extensive contact between peoples, flora and fauna from both old and new worlds (Diamond, 1998). The movement of disease has proved a major force in shaping world history, as wars, crusades, diasporas and migrations have carried infections to susceptible populations. Until World War II, more war victims died of microbes introduced by the enemy, than of battle wounds (Karlen, 1995). More often than not, the victors in past wars were not those armies with the best weapons and generals, but those bearing the deadliest pathogens (Zinsser, 1943;Diamond, 1998).

Initially, new infectious diseases could spread only as fast and far as people could walk. Then as fast and far as horses could gallop and ships could sail. With the advent of truly global travel, the last five centuries have seen more new diseases than ever before become potential pandemics (Karlen, 1995). The current reach, volume and speed of travel are unprecedented, so that human mobility has increased in high-income countries by over 1000-fold since 1800 (Wilson, 1995, Wilson, 2003). Aviation, in particular, has expanded rapidly as the world economy has grown, though worries about its potential for spreading disease began with the advent of commercial aviation (Massey, 1933). Passenger numbers have grown at nearly 9% per annum since 1960 and are expected to increase at more than 5% per annum for at least the next 10 years, with airfreight traffic showing similar changes (Upham et al., 2003). Similarly, globalization of the world economy has also resulted in a shipping traffic increase of over 27% since 1993 (Zachcial and Heideloff, 2003).

The efficiency, speed and reach of modern transport networks puts people at risk from the emergence of new strains of familiar diseases, or from completely new diseases (Guimera et al., 2005). Additionally, the global growth of economic activity, tourism and human migration is leading to ever more cases of the movement of both disease vectors and the diseases they carry.

This contribution reviews examples of past movement of three categories of disease through global transport networks: (i) pandemics; (ii) disease vector invasions; and (iii) vector-borne diseases. For each, we review examples of past events and their current status, while for sections (ii) and (iii), we put forward novel approaches for the modelling and prediction of future events.

2. Global Transport Networks and Pandemics

The past 500 years have provided numerous examples of how the establishment and expansion of worldwide transport networks has facilitated global pandemics of communicable diseases. Here we briefly review a selection of the world's major pandemics, their potential future threat and examine the development of approaches for their prediction and control.

2.1. Plague

More than 200 million people are thought to have been killed by bubonic plague in three major pandemics between the 14th and 17th centuries (Duplaix, 1988; Eckert, 2000). The plague bacillus, Yersinia pestis, was transmitted from infected rodents, often rats, by flea bites (Lounibos, 2002). Historical data show occasional major outbreaks of plague separated by long, plague-free periods (Keeling and Gilligan, 2000).

Many medical historians believe that the “Black Death” that killed a third of Europe's central and northern populations in the mid 14th century was brought about by bubonic plague. This view, however, has recently been questioned (Scott and Duncan, 2004). The Black Death arrived in Sicily in 1347 and within two years had swept northwards to Scandinavia, at a time when rats appear to have been absent from much of Europe (Twigg, 1984, Twigg, 2003). Even if introduced at ports, rat populations could not feasibly have colonized such large areas so quickly. New examination of contemporary accounts, and local parish records, reveal patterns of death that are consistent with a directly transmitted infection among family members and neighbours, with symptoms consistent with some sort of viral haemorrhagia. The real ‘vector’ appears to have been man: occasional introductions to certain nearby towns and villages coincided with the arrival of travellers on foot or horseback (Scott and Duncan, 2004). People at the time were aware of the effectiveness of isolation and quarantine within affected households, which would not have prevented infection spread by rats and fleas. It seems that only the limited transport and movement patterns of the time prevented even greater impacts on the European human population.

Whether caused by plague or some other pathogen, the Black Death found an entirely susceptible population, devoid of resistance. Its first sweep across Europe afflicted two-thirds of Europe's population before subsiding, though it remained endemic. Population regrowth and renewed travel then reignited the disease, causing further epidemics in 1361, 1371 and 1382, afflicting half, one-tenth and one-twentieth of the population respectively (Zinsser, 1943).

The most recent confirmed plague pandemic occurred early last century, with outbreaks principally in port cities, reflecting the dominant mode of international travel at the time. Initially originating in China, plague-infected rats were transported around the world in sailing vessels, sparking major epidemics at international ports such as Sydney, Bombay, San Francisco and Rio de Janeiro (Duplaix, 1988). The limited spread inland from port cities remains a mystery, but the control of rats and modernization of housing, food storage and sanitation, have been suggested as preventing large-scale inland rat migration (Zinsser, 1943). Spread did occur from San Francisco, however, resulting in plague becoming endemic in prairie dog colonies of Western USA, causing occasional human cases even today (Markel, 2005).

Bubonic plague is now principally regarded as a disease of only historical importance. There are, however, more frequent reports of increasing incidence locally (Barretto et al., 1994; Kumar, 1995), importation (Perlman et al., 2003), and of antibiotic-resistant strains (Galimand, 1997). Plague is thus re-emerging as a significant public health concern. Since the last pandemic, plague's geographic range has expanded, posing new threats to previously unaffected regions (Gage and Kosoy, 2005) and resulting in hundreds of cases in at least 14 countries (World Health Organization, 2003). Although recent outbreaks have been quickly controlled limiting case numbers, resultant economic disruptions have been severe. India's 1994 outbreak resulted in just 52 deaths, but over 1 billion USD in economic costs, demonstrating how vulnerable the global economy can be to the threat of infectious diseases (Cash and Narasimhan, 2000).

2.2. Cholera

Cholera is caused by an intestinal infection with the bacterium, Vibrio cholerae, leading to severe dehydration, shock and often-rapid death (Sack et al., 2004). The bacterium can survive for long periods in water and is commonly transmitted by contaminated water, or food that has been washed in such water. Accounts of cholera-like diseases go back as far as the times of Hippocrates and Buddha (Reidl and Klose, 2002). Over the past 185 years, Vibrio cholerae has escaped seven times from its endemic heartland in West Bengal, India, to result in pandemics (Sack et al., 2004). It first started as an epidemic outbreak in 1817 in India, but soon started spreading, in part due to British ship and troop movements, carrying the infection north and east to China, Japan and Indonesia (Reidl and Klose, 2002). The disease also spread along trade routes to the west as far as southern Russia (Karlen, 1995). Each successive pandemic increased in extent and severity, reflecting the expanding reach of the global transport system and increased movements of people, particularly on religious pilgrimages (Rogers, 1919). The 1830s saw Russian troops, English ships, Irish immigrants and Canadian exploration carry Vibrio cholerae to the Baltic, England, Ireland, Canada, USA and Mexico (Curtin, 1995). Its arrival in Mecca in 1831 in time for the Muslim pilgrimage is thought to have sparked over 40 epidemics by 1912 (McNeill, 1976). Statistically, the impact of cholera epidemics was rarely severe, with only a small percentage of populations affected, but it developed a fearsome reputation through seemingly bypassing all attempts at quarantine and because it attacked rich as well as poor (McNeill, 1976). Not until John Snow's work on cholera clusters in London in the 1850s, and later acceptance of ‘germ’ theories of disease, did a proper understanding and effective control develop (McNeill, 1976).

Cholera continues to affect many parts of the world. The most recent, and current, pandemic has resulted in the disease becoming endemic in much of Africa (Naidoo and Patric, 2002; Weir and Haider, 2004), South America (Seas et al., 2000; Chevallier et al., 2004) and southern Asia (Phukan et al., 2004; Weir and Haider, 2004), with antibiotic resistance on the rise (Sack et al., 2004). Newly found serotypes of Vibrio cholerae are likely to be the source of the next cholera pandemic, having already resulted in 30 000 cases in just a few months in Dhaka, Bangladesh (Faruque et al., 2003).

2.3. Influenza

The influenza virus is remarkable for the rapidity with which it can spread, the brevity of immunity it confers and its genetic variability (McNeill, 1976; Ferguson et al., 2003a). Despite an often-low fatality rate, the large number of cases makes influenza pandemics and epidemics a major health problem (Palese, 2004). Around 20% of children and 5% of adults worldwide develop symptomatic influenza each year (Nicholson et al., 2003). During the 20th century, influenza was the principal infectious disease to be influenced by the growing global transport network and to display pandemic behaviour. Three major pandemics occurred in 1918, 1957 and 1968 (Cox and Subbarao, 2000).

In 1918, the confluence of American with both European and African troops in northern France, and the emergence of new virus strains, provided the milieu for an epidemic of unprecedented scope (McNeill, 1976). The 1918 influenza pandemic killed around 40 million people in a year (Oxford, 2004), and resulted in an almost 10-year drop in the calculated average life expectancy of the global population (Palese, 2004). This disease is now used as a worst-case scenario for pandemic preparedness planning (Mills et al., 2004). Three influenza viruses with different haemagglutin surface proteins (H1, H2, H3) were responsible for the pandemics of the 20th century. Although it is theoretically possible to create vaccines against any new influenza virus given enough time and production capacity, the genetic instability of the virus means it can evolve quickly, thereby escaping the effects of newly developed vaccines (McNeill, 1976).

The 1957 pandemic originated in mainland China and traversed the globe within six months. This speed was attributable both to a haemagglutin surface protein shift from previous viruses, leaving the global population susceptible to infection; and to the availability of regular air and sea travel via which secondary epidemic sources were established (Thomas, 1992). Before it became widely epidemic in many countries, a vaccine had been developed and produced in sufficient quantities to reduce the incidence and intensity of influenza in developed countries with available vaccine, yet it still claimed over 70 000 lives in the US and many more elsewhere (Palese, 2004). In 1968, another strain was isolated in Hong Kong, and quickly spread around the world causing thousands of deaths, even though antibodies remaining from the 1957 pandemic were thought to have moderated the severity of infections (Cox and Subbarao, 2000). Epidemics continue to occur regularly (Viboud et al., 2004), as do movements of the virus through the global transportation system, causing outbreaks even on aircraft (Marsden, 2003).

Much remains unknown about influenza and the viruses that cause it; how they arise, how the shift to new strains occurs and whether the viruses migrate between northern and southern hemispheres to become epidemic in cold-weather seasons (Cox and Subbarao, 2000). The recent emergence of the avian influenza virus in south-east Asia has led many to fear that the next global pandemic is imminent (Webby and Webster, 2003; Fouchier et al., 2005; Webster and Hulse, 2005). At the time of writing, the H5N1 virus has infected at least 88 people, killing 51 of them (Webster and Hulse, 2005). Should the virus mutate sufficiently to enable sustained human-to-human transmission (Ungchusak et al., 2005), modern transport (Enserink, 2004) and the size of the currently susceptible global population means it could kill millions more than any previous pandemic if adequate preventative measures are not in place (Osterholm, 2005a, Osterholm, 2005b; Oxford, 2005).

2.4. HIV/AIDS

The spread of the HIV/AIDS pandemic worldwide is a travel story whose episodes can be traced by molecular tools and epidemiology (Lemey et al., 2003; Perrin et al., 2003). The exact origin of the HIV/AIDS virus remains unknown, but sero-archaeological studies have documented human infections with HIV prior to 1970 (Mann, 1989). Phylogenetic analysis has indicated that multiple interspecies transmissions from simians introduced two genetically distinct types of HIV into the human population: HIV-1 from chimpanzees and HIV-2 from sooty mangabeys (Lemey et al., 2003). While HIV-2 is mainly restricted to West Africa and is thought to have originated in Guinea-Bissau (Lemey et al., 2003), HIV-1 has spread globally from the first zoonotic transmission from chimpanzee to people around 70 years ago in central Africa (Jonassen et al., 1997; Russell et al., 2000; Perrin et al., 2003).

Data suggest that the current pandemic started in the mid-1970s and by 1980, through air travel, sea travel and human migration, had spread to between 100 000 and 300 000 people on at least five continents (Mann, 1989). Studies have also shown that certain groups of mobile and sexually active individuals are important in seeding local epidemics, including immigrants, intravenous drug users, tourists, truck drivers, military troops and seamen (Perrin et al., 2003; Salit et al., 2005). This is illustrated by the first documented infections in Europe, caused by a Norwegian seaman infected through heterosexual contact in a West African seaport, returning to infect his wife, who transmitted the infection to her daughter (Jonassen et al., 1997). The role of international travel in the spread of HIV was also highlighted by the case of ‘Patient Zero’, a Canadian flight attendant who travelled extensively worldwide. Analysis of several of the early AIDS cases showed that the infected individuals were the attendant's direct or indirect sexual contacts and could be traced to several different American cities, thereby demonstrating the role of international travel in spreading the virus (Karlen, 1995).

According to UNAIDS estimates, 39.4 million people were living with HIV at the end of 2004, causing around 3 million deaths a year in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), the worst-hit region (UNAIDS, 2004). The disease's spread can be linked to a variety of factors. In the United States, the rapid spread of AIDS between 1984 and 1990 can be modelled accurately using air traffic flows between cities (Gould, 1995, Gould, 1999). The non-homogenous distribution of the global pandemic both between and within countries reflects levels of social vulnerability and mobility (Bronfman et al., 2002). Infection rates are usually higher in urban areas; rural areas, especially in Africa, are affected by the levels of mobility and migration which enable the virus to shift from urban to rural centres, and tend to mean that infection rates are higher near main roads and in trading centres than in isolated villages (Lagarde et al., 2003).

2.5. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a coronavirus that adapted from animal hosts to become readily transmissible between humans (Peiris et al., 2004). Southern China has produced one plague pandemic and two influenza pandemics over the last 150 years (McNeill, 1976), and SARS represents the fourth global pandemic originating from the region. SARS probably first emerged in Guangdong province around November 2002 among those in contact with the live-game trade (Peiris et al., 2004). Although unproven, it seems likely that animal to human interspecies transmission occurred at ‘wet markets’ where a wide range of live poultry, fish, reptiles and other mammals are sold (Peiris et al., 2004).

On 21 February 2003, a physician from Guangdong spent a single day in a Hong Kong hotel, during which time he transmitted an infection to 16 other guests. These guests seeded outbreaks in Hong Kong, Toronto, Singapore and Vietnam, and within weeks SARS infected over 8000 people in 26 countries across 5 continents (Peiris et al., 2004). The WHO invoked traditional public health measures to contain the outbreak, including heightened vigilance, screening of travellers and isolation and quarantine of affected individuals and their close contacts. At the same time, advanced technologies identified the causative agent and informed prevention and treatment options (Skowronski et al., 2005). The exhaustive effort resulted in cessation of transmission by early July 2003.

While the number of fatalities was small (<800) (Skowronski et al., 2005) in comparison with other pandemics, the speed and extent of the proliferation of SARS highlighted the potential for modern globalized economic activity and an ever-expanding air travel network to spread infectious diseases. It also demonstrated how a new and poorly understood disease, with no vaccine and no effective cure, can adversely affect economic growth, trade, tourism and social stability, especially when its perceived risk is many times higher than its actual risk (Heymann, 2004). The economic impact of SARS has been estimated at between US$30–140 billion (Skowronski et al., 2005), largely as a consequence of reduced travel and investment in Asia. SARS also showed how inadequate surveillance and response capacity in a single country can have an impact upon global public health security (Heymann, 2004). While the pandemic ended in late 2003, the fact that three years later there is no vaccine and that the animal reservoir of the disease remains to be identified conclusively (though civet cats are thought to be the source; Song et al., 2005), means a return of SARS cannot be ruled out (Skowronski et al., 2005).

2.6. Bioterrorism

While bioterrorism has been at the forefront of public health planning since the 11 September 2001 attacks on New York, it has a long history. One of the earliest documented uses of biological weaponry occurred in 1346 when wars and plague were decimating the Middle East. A three-year siege of the Crimean walled-port of Jaffa by the Tatars was finally ended soon after plague-infected corpses were catapulted over the city walls, seeding epidemics which led to its downfall (Karlen, 1995).

Today, the list of agents posing major public health risks if acquired and effectively disseminated in a bioterrorist attack is relatively short (Kortepeter and Parker, 1999). This is counterbalanced by the potential of such agents to challenge our abilities to limit the numbers of casualties. The most threatening of infectious agents include botulism, influenza, plague, tularaemia, viral haemorrhagic fevers (e.g. Ebola, Marburg and Lassa fevers), anthrax and smallpox (Lane et al., 2001; Madjid et al., 2003). In the minds of most military and counterterrorism planners, anthrax and smallpox represent the greatest bioterror threats (Kortepeter and Parker, 1999).

Anthrax is one of the great infectious diseases of antiquity, and some of the plagues described in the Bible may have been outbreaks of this disease in cattle and humans (Cieslak and Eitzen, 1999). Caused by infection with Bacillus anthracis, it has little potential for person-to-person transmission, and most endemic cases are contracted cutaneously through contact with infected herbivores. As a weapon, it would most likely be delivered by aerosol as seen in 2001 in the US Postal Service attacks (Dewan et al., 2002; Greene et al., 2002) and, consequently, acquired by inhalation. Without rapid treatment, death may occur in as many as 95% of cases (Cieslak and Eitzen, 1999). Although a licensed vaccine and efficient therapy exists, the short incubation period and rapid progression of the disease means identification and treatment of any exposed populations is likely to present a major challenge.

Smallpox is a viral disease spread by inhalation of air droplets or aerosols and is unique to humans (Henderson, 1999). It has played a major part in shaping human history, repeatedly killing millions in Europe in epidemics throughout the 16th century before immunity arose to reduce its severity (Alibek, 2004). Europeans then inadvertently introduced smallpox to the New World, where it aided in wiping out whole ancient civilizations that had no immunity (McNeill, 1976; Karlen, 1995). Aggressive global vaccination programmes led to the eradication of naturally occurring smallpox in 1977. The consequent halt to routine vaccination means that today the world's population again has little immunity to the disease (Lane et al., 2001). Smallpox's case mortality rate of around 30% and its high transmissibility make it a potentially potent bioweapon and although officially just two samples exist, the existence of other sources, particularly from the 1970s Soviet research programme, cannot be ruled out (Lane et al., 2001). In the face of such a possible threat, funding of research examining the scale of possible casualties and optimal control strategies has been increased massively, and various high-profile modelling studies have been undertaken (Meltzer et al., 2001; Halloran et al., 2002; Kaplan et al., 2002; Bozzette, 2003; Ferguson et al., 2003b; Grais et al., 2003b). The following section looks at the approaches and findings of such studies.

2.7. Predicting, Modelling and Controlling Future Pandemics

Numerous approaches have been developed which attempt to capture the possible future movements of newly emergent communicable diseases through global and local transport networks (Thomas, 1992; Haggett, 2000). The growth and movement of an epidemic or pandemic is governed principally by the number of secondary cases generated by an initial or primary case in an entirely susceptible population (the reproductive number of the disease, R0), and the average time taken for the secondary cases to be infected by a primary case (Bailey, 1967; Anderson and May, 1991). Splitting modelled populations into susceptible, infected and recovered categories forms the basis of much epidemic and pandemic modelling and has provided qualitative insights into the epidemiology of a wide range of pathogens. To obtain quantitative predictions for risk assessment and policy formulation, however, refinement of such basic concepts is required to account for complex biological and behavioural factors, including the variation of infectiveness and susceptibility within a population, and the mixing, movement and socio-economic structure of the population at risk (Ferguson et al., 2003b).

While the movements of pandemics are notoriously unpredictable (Thomas, 1992), those models that can be calibrated using data from previous epidemic events are perhaps the ones that stand the best chance of being used to predict the spread of communicable diseases in the future, enabling the construction of early warning systems and forming a basis for planning control strategies (Haggett, 2000). Such an approach was demonstrated by Rvachev and Longini (1985) who showed the diffusion of the 1968–1969 influenza pandemic to be predictable through a model based on the air travel network of the time. Incidence data from the pandemic origin, Hong Kong, were used to estimate model parameters, such as contact level between susceptible and infectious individuals, time taken in latent and infectious states and the fraction of people susceptible to the virus. Annual average daily air passenger numbers between 52 cities were then used to derive probabilities of travel between the cities. Finally, the seasonality of influenza was taken into account by applying a scaling factor to northern and southern hemisphere city contact level parameters to mimic the hemispheric swing of influenza epidemics. This model was later updated and refined to provide the basis for predictive models of the spread of influenza, smallpox, SARS and other infectious agents through the global transportation network (Longini et al., 1986; Dye and Gay, 2003; Grais et al., 2003a, Grais et al., 2003b; Vogel, 2003; Hufnagel et al., 2004).

Given the vast range of complicating factors, no model can be expected to predict the spread of an infectious disease pandemic with complete accuracy. Modelling can, however, identify possible efficient interventions from a range of available scenarios, taking into account the range of uncertainties of key epidemiological parameters (Ferguson et al., 2003b). Models can also find use during actual outbreaks, as was shown in the real-time statistical modelling of the 2001 UK foot-and-mouth epidemic (Ferguson et al., 2001; Keeling et al., 2003). Haggett (2000) outlines a number of important points relevant to the future control of epidemics and pandemics: (i) pandemic control will rely less and less on conventional spatial barriers as the global transport network continues to expand, (ii) the speed of modern transport means prompt surveillance and rapid reporting now play a critical role in preventing the spatial spread of a disease, (iii) mathematical models will become central in identifying aberrant behaviour in disease trends and (iv) the high cost of surveillance makes sampling design and the development of cost-effective monitoring and testing approaches vital to effective epidemic early warning systems.

3. Global Transport Networks and Disease Vector Invasions

Aircraft and ships are believed to be directly responsible for rapid expansion in the range of many plants and animals via inadvertent transport (Perrings et al., 2005), including some of the world's principal disease vectors (Lounibos, 2002). Here we briefly review some of the major invasion events facilitated by transport, and demonstrate some approaches to the prediction of future disease vector invasions.

3.1. Aedes aegypti

Ae. aegypti is known to be a vector of numerous human pathogens, and is the principal vector of both yellow and dengue fever viruses. Though the mosquito is now established throughout the tropical and sub-tropical regions of the world, it was located solely in West Africa until the 15th century (Lounibos, 2002). At some point, the insect adapted to anthropogenic breeding sites, such as water storage jars in ships (Lounibos, 2002). This ability enabled it to take full advantage of the growing slave trade from West Africa to reach the new world or to invade Portugal and Spain before its proliferation elsewhere on European ships. Ae. aegypti consequently became established across the tropical and temperate regions of the Americas, where caused yellow fever epidemics at port cities (Haggett, 2000). Intensive control and eradication schemes in the 1950s and 1960s reduced its extent (Gubler, 2004a). Gradual resurgence following the end of these control campaigns has resulted in the species once again becoming widespread across the Americas, and associated with the emergence of dengue and dengue haemorrhagic fever (Gubler and Clark, 1995). Ae. aegypti also invaded tropical Asia, where its dispersal has again been associated with a rise in dengue and dengue haemorrhagic fever incidence (Gubler and Clark, 1995).

3.2. Anopheles gambiae

Perhaps the most devastating introduction of a disease vector of recent times was that of An. gambiae, the most efficient vector of Plasmodium falciparum malaria, from West Africa to Natal in North-Eastern Brazil by either steamship or aircraft in 1930 (Soper and Wilson, 1943; Lounibos, 2002). An. gambiae proved extremely well suited to parts of Brazil where the temperature, humidity and precipitation patterns match closely malaria endemic regions of East Africa (Killeen et al., 2002; Killeen, 2003). Its gradual spread over 10 years into 54 000 km2 of Northeast Brazil led to extensive malaria epidemics, costing 16 000 lives and around 3 billion USD (modern day estimate) in healthcare, drugs and the vector eradication programme (Killeen et al., 2002). These epidemics were based solely on the greater vectorial capacity of An. gambiae relative to local mosquito species, as malaria was already endemic in Brazil. Similarly, high mortality rates were seen on Mauritius when An. gambiae was introduced accidentally in 1866, sparking major malaria epidemics (Lounibos, 2002). Control efforts ended the epidemics, but low-level and localized rural transmission continues.

3.3. Aedes japonicus

Ae. japonicus was first recorded in the states of New York and New Jersey, USA in 1998 (Peyton et al., 1999). Native to Japan, Southern China and Korea where the larvae develop in natural and artificial containers, its likely mode of introduction was through tyre shipments. Since the initial introduction, the mosquito has spread to Connecticut (Mustermann and Andreadis, 1999), Maryland, Pennsylvania and Ohio (Lounibos, 2002). The discovery of wild-caught Ae. japonicus infected with West Nile virus (WNV) (Turell et al., 2001) and the mosquito's competence as a vector of Japanese encephalitis suggest that it could become of public health importance in North America. Ae. japonicus was also recently detected in Orne Departement in Northern France and in New Zealand, demonstrating its potential to expand into Europe and Australasia (Laird et al., 1994; Schaffner et al., 2003).

3.4. Aedes albopictus

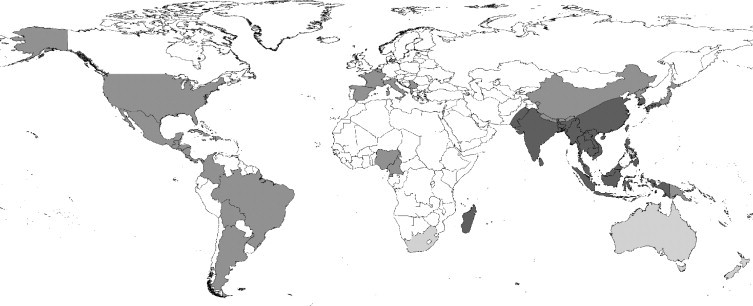

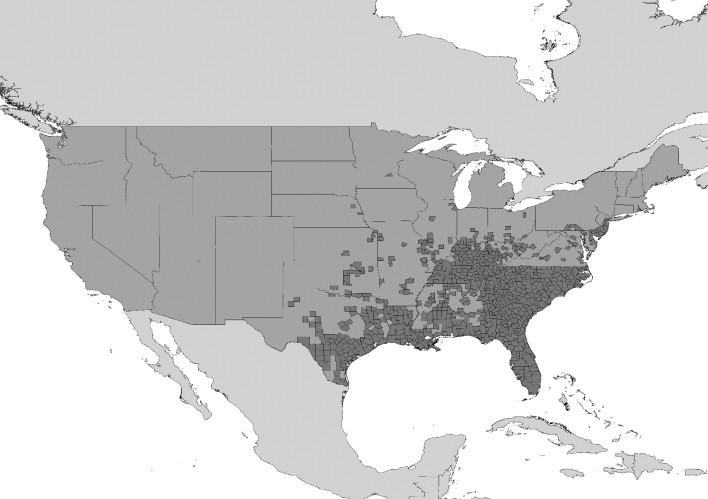

The Asian tiger mosquito, Ae. albopictus, is a competent vector of 22 arboviruses, including West Nile, dengue and yellow fever viruses (Gubler, 2003; Gratz, 2004). Although Ae. aegypti is the principal vector of dengue fever, recent outbreaks of the disease in the absence of Ae. aegypti have implicated Ae. albopictus as a competent vector (Gratz, 2004; Effler et al., 2005). The range expansion of Ae. albopictus from its Old World distribution (Figure 1 ) over the past 75 years is perhaps the best documented of any vector invasion. The mosquito spread from its range initially to the Pacific Islands (Gratz, 2004) in the 1930s and then, within the last 20 years, to other countries in both the Old and New Worlds (Moore and Mitchell, 1997; Gratz, 2004). This is thought to have been through ship-borne transportation of eggs and larvae in tyres (Reiter and Sprenger, 1987; Reiter, 1998). The spread of Ae. albopictus throughout the Eastern USA from its discovery in Harris County, Texas, in 1985 has been monitored extensively (Moore and Mitchell, 1997; Moore, 1999). Figure 2 shows its extent in 2000.

Figure 1.

The Old World distribution of Ae. albopictus (dark grey); countries reporting established breeding populations of Ae. albopictus in the last 30 years (middle grey); countries reporting Ae. albopictus interception at ports (light grey). Data sources: Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN) (http://www.ciesin.org/docs/001-613/map15.gif), supplemented with information from literature sources (Gratz, 2004; Gubler, 2003; Lounibos, 2002; Medlock et al., 2005; Moore, 1999; Moore and Mitchell, 1997).

Figure 2.

Counties of the United States of America reporting the presence of Ae. albopictus in 2000. (Adapted from US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); URL: http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/arbor/albopic_97_sm.htm.)

3.5. Predicting Future Disease Vector Invasions

Developing approaches to highlight routes of the greatest risk of invasion by disease vectors within the global transport network is an important prerequisite to planning effective control and disinsection efforts. Although distance may no longer represent a significant barrier to vector traffic, climate at the point of entry still presents a fundamental constraint to establishment, since poikilothermic arthropods are very sensitive to the weather. Here we review an approach, first outlined in Tatem et al. (2006a), based on air and sea traffic volume as well as climatic data, and tested against the movements of Ae. albopictus to examine how well these factors predicted its spread.

3.5.1. Data Sources

Major international seaport names, locations and estimated number of ships per annum between each were obtained from Drake and Lodge (2004). The data consisted of the estimated number of ship visits in 2000 to the 243 most frequently visited ports. Flight data on total passenger numbers moving between major airports in the year 2000 (assuming 100% aircraft capacity) using statistics supplied by all scheduled airlines were obtained from OAG Worldwide Ltd. The database contained data on the world's top 100 airports by traffic, plus the principal airport of 178 other countries if otherwise not included in the top 100. Data on a total of 7129 routes between 278 international airports in the year 2000 were therefore available. Gridded meteorological data (New et al., 2002) at 10′ spatial resolution 1961–1990 were obtained and averaged to produce a synoptic year. The mean, maximum and minimum temperature, rainfall and humidity measurements were extracted to produce nine climatology surfaces.

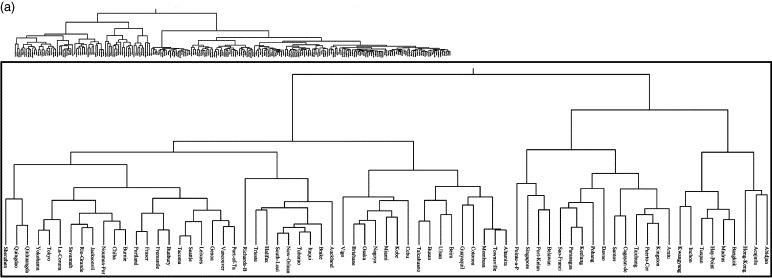

3.5.2. Climatic Dendrograms

Dendrograms are visual representations of the results of hierarchical clustering (described below) that are commonly used in the fields of evolution and genetics, and occasionally in an environmental context (Sugihara et al., 2003; Rogers and Robinson, 2004). Here, dendrograms are used to provide a climatic representation of the global air and sea transportation networks, a method first outlined in Tatem et al. (2006a). The dendrograms provide a way of restructuring the world as a disease vector may see it, given unlimited transport opportunities, with certain spatially distant sea/airports linked closely because of their climatic similarities, while spatially proximate ports may appear poorly linked if their climates differ significantly.

To create global sea and air transport network dendrograms, the locations of the 243 ports and 278 airports were superimposed onto the nine climatology surfaces and each 10′ spatial resolution grid square covering the seaport/airport location identified. To ensure that a representative climate was included, where possible, up to eight land pixels surrounding each seaport/airport grid square were also identified, forming a 3×3 grid square window centred on the airport/port. This requirement was not met for airports located coastally or on small islands or for the majority of seaports. In these cases, reduced numbers of land pixels were extracted. Any seaports/airports located on islands too small to be represented by the climatology surfaces were eliminated from the analysis (reducing the sample size to 241 seaports and 259 airports). The selected grid square data from the nine climatology surfaces thus formed the climate ‘signatures’ used in the analyses. These signatures represented a quantitative description of the climatic regime at each seaport and airport, in terms of temperature, rainfall and humidity.

Both the lack of sufficient co-variance information in the majority of seaport/airport signatures and the location of many seaports/airports on small islands dictated that only ‘Euclidean’ distances could be used as a measure of climatic similarities. Euclidean distance is defined as the shortest straight-line distance between two points: in this case it is the distance between the centroids of the port climate signatures in nine-dimensional space (ERDAS, 2003). Euclidean distances between the centroid of each seaport/airport signature and the centroids of every other seaport/airport signature were calculated to derive separate seaport and airport climate dissimilarity matrices. A simple test using other distance measures (e.g. divergence, Jefferies-Matusita; ERDAS, 2003) showed no obvious changes in the dendrogram architecture from the Euclidean one used here.

The climate dissimilarity matrices were subject to hierarchical clustering using an agglomerative algorithm (Webb, 2003). Hierarchical clustering procedures are the most commonly used method of summarising data structure (Webb, 2003). The clustering process produces a hierarchical tree, which is a nested set of partitions represented by a tree diagram, or dendrogram. The clustering results here were translated into dendrograms based on centroid linkage. Figures 3a and b show the climatic dendrograms for the major seaports and airports, respectively.

Figure 3.

(a) Climatic similarity dendrograms for the major seaports of the World and (b) climatic similarity dendrograms for the major airports of the World. In both figures the inset close-up shows the branches of significance to the dispersal of Ae. Albopictus.

The seaport and airport locations were overlaid on the (historical) Ae. albopictus distribution map (Figure 1) and were classified as either inside or outside the distribution. Those seaports/airports within the distribution were located on the relevant dendrogram (Figure 3). The dendrogram branch which encompassed at least 90% of the seaports/airports was designated as defining the limits of the ‘climatic envelope’ of Ae. albopictus, i.e. the range of climatic conditions within which it can survive. This allowed for the fact that Ae. albopictus has both temperate (diapausing) and tropical (non-diapausing) races with distinct environmental requirements and different original geographical distributions (Hawley et al., 1987). Thus, the 90% cut-off on the seaports dendrogram (Figure 3a) encompassed a single branch, but contained two major sub-branches, with the remaining 10% of ports displaying quite distinct environments (Mormugao, New-Mangalore and Kuching). Ninety percent of airports within the pre-expansion distribution of Ae. albopictus can be encompassed in a single branch of the airport dendrogram (Figure 3b), but temperate and tropical races are again distinguishable within this branch. Those seaports/airports not within its historical distribution, but linked by a dendrogram branch within the climatic envelope were therefore identified as being similar enough climatically for there to be a risk of establishment.

3.5.3. Risk Routes

Given that ship/aircraft volume on a transport route, as well as climatic similarity between origin and destination port, is important in determining invasion risk (Lounibos, 2002; Drake and Lodge, 2004; Normile, 2004), the transport and Euclidean climatic distance matrices were used to obtain a relative measure of importation and establishment risk to those seaports/airports identified as being at-risk within the dendrogram. Each matrix was rescaled independently to a range of 0–1 and the results for the climatic matrix then inverted so that values near to 1 represented similar climates and values close to 0 represented dissimilar ones. Values in the two rescaled matrices for any pair of ports—one with and one without the invading species in question—were then multiplied together to estimate the relative risk of invasion and establishment. As an example, the rescaled climatic distance between Chiba, Japan and Richards Bay, South Africa was 0.9703, reflecting similar climatic regimes, while the rescaled traffic volume on the route was just 0.0012, a low-traffic volume in global terms. When these are multiplied, we arrive at a disease vector invasion risk of 0.00116, which is low in comparison to the risk value of 0.35 for the Chiba to New Orleans, USA, route and may partly explain why Ae. albopictus invaded New Orleans successfully, but not Richards Bay (to date).

Table 1 details the top 20 shipping routes (from over 20 000 possible routes) and Table 2 shows the air travel routes (from over 6000 possible routes) identified as having the highest relative risk of Ae. albopictus invasion. The values relative to route 1 and the recorded details of this mosquito's spread are included in both tables. There is correspondence between the predicted risk routes in Table 1 and the global invasions or interception of Ae. albopictus. Three of the top 10 shipping routes run from Japan to the south-east United States, where some of the earliest breeding populations of Ae. albopictus were found and identified as originating from Japan (Lounibos, 2002). Genoa, the destination of five more routes from Japan in the top 20, was one of the earliest European cities to report Ae. albopictus establishment in 1990 (Romi et al., 1999); the vector has since become the most important local nuisance mosquito (Gratz, 2004). Of the remaining routes in Table 1, interceptions of Ae. albopictus in tyre shipments from Japan to Australasia have been made in both Brisbane (Kay et al., 1990) and Auckland (Laird, 1990; Laird et al., 1994), but the species appears not to have become established there, probably due to strict inspection and fumigation policies (Lounibos, 2002). No documented evidence exists of invasion by Ae. albopictus of Fraser and Vancouver (Canada). On the basis of Fraser's and Vancouver's climatic similarities to, and the seaborne traffic levels from, Japan, these ports should be considered at high risk, especially as Ae. albopictus has already been intercepted at nearby Seattle (CDC, 1986).

Table 1.

Ae. albopictus top twenty shipping risk routes

| Rank | From | To | Ae. albopictus intercepted? | Ae. albopictus established? | Risk relative to route 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chiba | Japan | New Orleans | USA | Y | Y | 1.00 |

| 2 | Chiba | Japan | Genoa | Italy | Y | Y | 0.99 |

| 3 | Chiba | Japan | Fraser | Canada | N | ? | 0.92 |

| 4 | Chiba | Japan | Brisbane | Australia | Y | ? | 0.83 |

| 5 | Chiba | Japan | Auckland | NZ | Y | ? | 0.67 |

| 6 | Chiba | Japan | South Louisiana | USA | Y | Y | 0.65 |

| 7 | Yokohama | Japan | Fraser | Canada | N | ? | 0.64 |

| 8 | Kobe | Japan | Fraser | Canada | N | ? | 0.59 |

| 9 | Chiba | Japan | Miami | USA | Y | Y | 0.59 |

| 10 | Yokohama | Japan | Genoa | Italy | Y | Y | 0.59 |

| 11 | Chiba | Japan | Vancouver | Canada | N | ? | 0.57 |

| 12 | Kobe | Japan | Genoa | Italy | Y | Y | 0.53 |

| 13 | Osaka | Japan | Fraser | Canada | N | ? | 0.51 |

| 14 | Yokohama | Japan | Brisbane | Australia | Y | ? | 0.51 |

| 15 | Chiba | Japan | Freemantle | Australia | Y | ? | 0.50 |

| 16 | Tokyo | Japan | Genoa | Italy | Y | Y | 0.46 |

| 17 | Osaka | Japan | Genoa | Italy | Y | Y | 0.45 |

| 18 | Tokyo | Japan | Fraser | Canada | N | ? | 0.44 |

| 19 | Kobe | Japan | Brisbane | Australia | Y | ? | 0.44 |

| 20 | Kobe | Japan | New Orleans | USA | Y | Y | 0.44 |

Table 2.

Ae. albopictus top twenty air travel risk routes

| Rank | From | To | Ae. albopictus intercepted? | Ae. albopictus established? | Risk relative to route 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tokyo N | Japan | Honolulu | Hawaii (USA) | Y | Y | 1.00 |

| 2 | Osaka K | Japan | Honolulu | Hawaii (USA) | Y | Y | 0.48 |

| 3 | Nagoya | Japan | Honolulu | Hawaii (USA) | Y | Y | 0.30 |

| 4 | Tokyo N | Japan | Seattle | USA | Y | ? | 0.29 |

| 5 | Tokyo N | Japan | Brisbane | Australia | Y | ? | 0.14 |

| 6 | Fukuoka | Japan | Honolulu | Hawaii (USA) | Y | Y | 0.13 |

| 7 | Seoul | South Korea | Honolulu | Hawaii (USA) | Y | Y | 0.12 |

| 8 | Tokyo H | Japan | Honolulu | Hawaii (USA) | Y | Y | 0.10 |

| 9 | Taipei C | Taiwan | Seattle | USA | Y | ? | 0.10 |

| 10 | Tokyo N | Japan | Portland | USA | Y | ? | 0.09 |

| 11 | Nagoya | Japan | Portland | USA | Y | ? | 0.09 |

| 12 | Guam | Guam | Honolulu | Hawaii (USA) | Y | Y | 0.09 |

| 13 | Kuala Lumpur | Malaysia | Brisbane | Australia | Y | ? | 0.08 |

| 14 | Tokyo N | Japan | Noumea | New Caledonia | 0.08 | ||

| 15 | Taipei C | Taiwan | Brisbane | Australia | Y | ? | 0.08 |

| 16 | Taipei C | Taiwan | Honolulu | Hawaii (USA) | Y | Y | 0.07 |

| 17 | Osaka K | Japan | Seattle | USA | Y | ? | 0.07 |

| 18 | Port Moresby | P.N.G. | Brisbane | Australia | Y | ? | 0.06 |

| 19 | St Denis | Reunion | Dzaoudzi | Mayotte | 0.06 | ||

| 20 | Bangkok | Thailand | Brisbane | Australia | Y | ? | 0.05 |

The relative importance of sea traffic volume and local climate in the establishment of Ae. albopictus was estimated by examining the 69 ports within the invasion risk group. Twenty-one ports are within the original range of Ae. albopictus, but of the other 47, to-date just over half are in regions reported to be colonized by this species or where breeding populations have been found. Within this group of 47 ports, the average climatic distances of the 24 invaded and 23 non-invaded ports were identical, but sea traffic volumes were 2.43 times greater in the former than the latter (41.84 ship visits per annum per route for invaded ports and 17.24 for non-invaded ones), with the difference found to be significant (, ). Sea traffic volumes, therefore, appear to make an important contribution to relative invasion risk. This result corroborates recent theories regarding direct linkage between biological invasion success and propagule pressure (Vila and Pujadas, 2001; Levine and D’Antonio, 2003; Normile, 2004; Lockwood et al., 2005).

Although air travel was not implicated in the spread of Ae. albopictus, 8 of the 20 highest risk air routes link the original range of Ae. albopictus with Honolulu in Hawaii, where this species has established (Mitchell, 1995) (Table 2). The large air traffic volume running from Tokyo to Hawaii identifies this route as providing over double the risk of invasion as the others in Table 2. Details on Hawaiian ports were not available in the sea traffic database. In every one of the top 20 high-risk air routes, Ae. albopictus has been either intercepted or found breeding at the destinations listed.

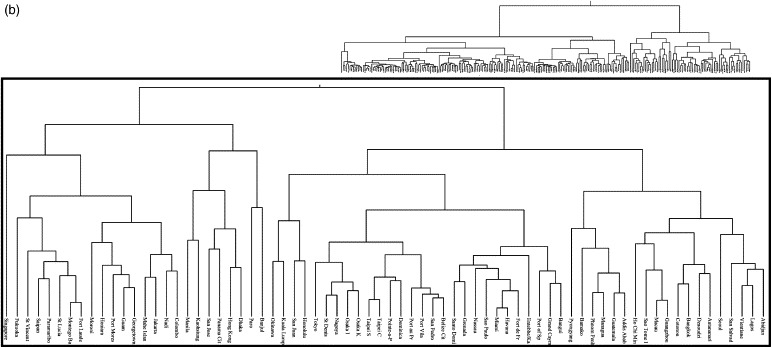

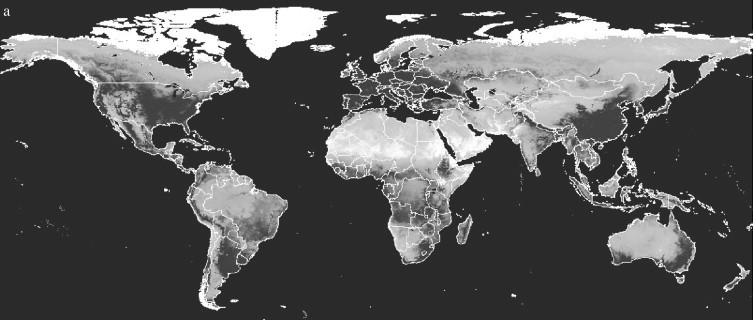

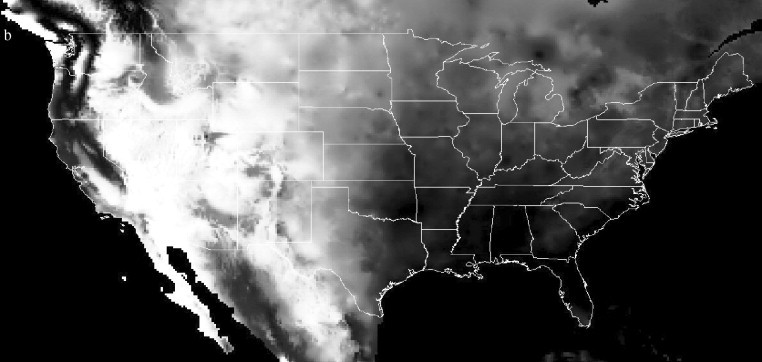

3.5.4. Climatic Distance Images

In addition to determining at which seaport or airport an accidentally introduced disease vector is likely to become established, it is important to identify the areas to which vectors may subsequently spread. An initial assessment of this can be undertaken by examining the climatic distance of the surrounding area from the disease vector's origin. This was tested for Ae. albopictus, again using gridded climatologies (New et al., 2002). Given that the origin of the invasive Ae. albopictus was found to be Japan (Moore, 1999; Gratz, 2004), and the above analysis found Chiba to be the likely origin port, the climatic signature of Chiba was used to calculate a global climatic distance image at 10′ spatial resolution. In this analysis, the ‘Mahalanobis’ distance rather than the Euclidean distance of every 10′ pixel from Chiba's signature was calculated. The Mahalanobis distance differs from Euclidean distance as it accounts for the correlations of the dataset by examining the similarity between each signature's covariance matrix (ERDAS, 2003). The results are shown in Figure 4a , with a close-up of the USA in Figure 4b. Comparison with maps of known Ae. albopictus invasion (Figure 1, Figure 2; Lounibos, 2002) shows good correspondence, demonstrating the broad applicability of the approach in estimating future disease vector movement. The dark regions (indicating climatic similarity to Chiba) across Europe and in South Africa, Australia and New Zealand, indicate that given the opportunity provided by transport networks, Ae. albopictus may spread yet further. Future work on invasion risk should focus on the incorporation of data on land transport routes, human population distribution and how these relate spatially to endemic disease regions.

Figure 4.

Mahalanobis climatic distance from Chiba Port, Japan, for (a) the world and (b) the United States of America. Darker shades represent areas with climates more similar to that of Chiba.

4. Global Transport Networks and Vector-Borne Diseases

This section reviews briefly the movement and emergence of vector-borne diseases through global human transport, and outlines approaches for highlighting areas at risk from future events.

4.1. Yellow Fever

Outlined in detail in Rogers et al., (this volume, pp. 181–220), yellow fever represents a major public health problem in many regions of tropical Africa and South America, and used to be a disease that was regularly exported elsewhere (Haggett, 2000). The enforcement by the World Health Organization of yellow fever vaccination requirements for travel to endemic regions, and consequent minimal movement of the disease, demonstrates the effectiveness of global control measures. Despite advances in preventative measures and the existence of a reliable vaccine, yellow fever outbreaks and epidemics have increased in recent years, particularly in Africa (Mutebi and Barrett, 2002). Many of these epidemics have been caused by the large-scale movements of susceptible individuals into high yellow fever risk zones and by the neglect of control procedures (Mutebi and Barrett, 2002).

4.2. Dengue

Outlined in detail in Rogers et al., (this volume, pp. 181–220), dengue fever and dengue haemorrhagic fever are probably the fastest spreading diseases of the modern day (Gubler and Clark, 1995; Gubler, 2002). The past 30 years has seen a marked global emergence and re-emergence of epidemic dengue, with more frequent and larger epidemics associated with more severe disease (Mackenzie et al., 2004). Fuelled by the expansion of the range of its principal vector, Ae. aegypti (Lounibos, 2002), the expansion of the range of what may be an urban–rural bridge vector, Ae. albopictus (Lounibos, 2002; Gratz, 2004), large-scale global urbanization (Gubler, 2004b; Tatem and Hay, 2004) and increasing movement by air of people incubating its infections (Upham et al., 2003), dengue is fast becoming the most important arboviral disease of humans (Mackenzie et al., 2004). The global air transport network is not only aiding the spread of both dengue vectors and virus serotypes within tropical regions suitable for transmission, but also facilitating a substantial increase of imported cases elsewhere (Jelinek, 2000; Frank et al., 2004; Effler et al., 2005; Shu et al., 2005).

4.3. West Nile Virus

WNV is a mosquito-borne flavivirus native to Africa, Europe and Western Asia (Hayes, 2001). It circulates mainly among birds, but can infect many species of mammals, amphibians and reptiles (Dauphin et al., 2004; Kilpatrick et al., 2005). The appearance of WNV in New York in 1999 and its subsequent spread westwards across the United States (Petersen and Hayes, 2004) and into Central America represents the best-documented movement of a disease in recent times (Granwehr et al., 2004). Spread by many different species of mosquitoes and the movement of birds, it is less influenced by human transportation networks than other diseases discussed in this review, but its arrival in the US in 1999 is thought to be associated with some form of commerce or human travel. With changing climate, coupled with increased human movement and spread of exotic mosquitoes via global transport networks, the risks of further WNV outbreaks are a distinct possibility (Granwehr et al., 2004; Medlock et al., 2005).

4.4. Malaria

General socio-economic improvement, combined with wetland drainage and other water resource development, improved housing, better animal husbandry and wider availability of quinine resulted in the decline of indigenous malaria in high-income countries during the 19th and 20th centuries (Hay et al., 2004). In contrast, increasing tourism and human migration has meant that malaria continues to be imported into high-income countries, which have been classified as free of malaria transmission. Numbers vary, but it is estimated that as many as 40 000 cases of malaria a year occur in Europe alone (Toovey and Jamieson, 2003). This influx of infected travellers poses two major hazards: (i) a returning traveller who has acquired malaria may be diagnosed incorrectly, as malaria may be unfamiliar to a physician in a country without indigenous malaria, resulting in high P. falciparum case-fatality rates (Muentener et al., 1999; Ryan et al., 2002; Spira, 2003). (ii) Favourable climatic conditions may make autochthonous transmission possible through local vectors (Isaäcson, 1989; Layton et al., 1995; Gratz et al., 2000).

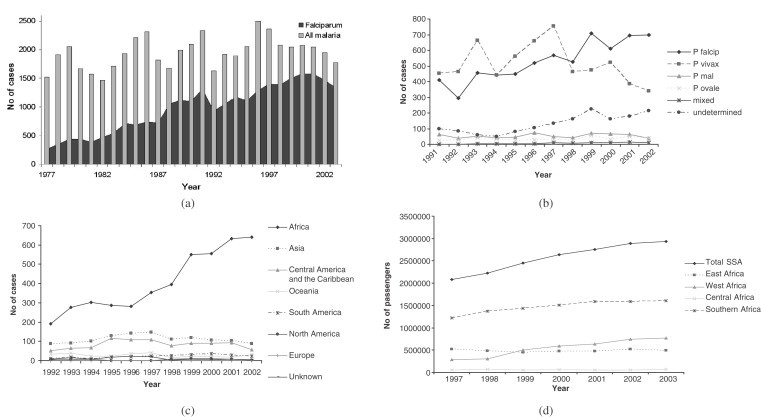

4.4.1. Imported Malaria Trends

The last 25 years have seen both the numbers and types of malaria imported to high-income countries change significantly. Figures 5a and b highlight the trends in imported cases to the UK and USA, respectively. Figure 5a shows that the UK consistently had 1500–2500 cases of malaria every year reported since 1977. However the proportion of P. falciparum malaria has risen substantially (Malaria Reference Laboratory, 2004). Figure 5b demonstrates that while the USA has fewer imported malaria cases annually than the UK, the trend towards increasing numbers of P. falciparum cases continues. The rise in P. falciparum cases in the USA is mirrored by a substantial rise in cases acquired in Africa (Figure 5c). The precise causes of the decline in imported Plasmodium vivax cases and increase in those of P. falciparum in the UK and USA are difficult to determine given the myriad of factors involved in transmission, including changes over time of levels and types of antimalarial use, malaria prevalence, travel activities and reporting efficiency. What is clear, however, is that over the past few decades, travel from the UK and USA to SSA, where P. falciparum malaria is highly endemic, has risen steadily. Analysis of UK Civil Aviation Authority (UKCAA) statistics shows that the number of passengers travelling on flight routes between SSA and the UK rose by around a million between 1997 and 2003 (Figure 5d), with the largest rises on routes from West Africa, where the highest levels of P. falciparum malaria endemicity are found (see Guerra et al., this volume, pp. 157–179).

Figure 5.

(a) Graph showing the number of UK imported malaria cases 1977–2002 (Data source: UK Health Protection Agency (UKHPA)); (b) Graph showing the number and type of USA imported malaria cases 1991–2002 (Data source: Shah et al., 2003); (c) Graph showing the acquisition region of USA imported malaria cases 1992–2002 (Data source: Shah et al., 2003); and (d) Graph showing the number of passengers travelling on air routes between the UK and SSA, broken down by SSA region 1997–2003 (Data source: UK Civil Aviation Authority (UKCAA)).

4.4.2. Drug Resistance

The increasing level of malaria movement also has the effect of enhancing the possibility and speed of drug-resistant malaria spread. Since the first reports of chloroquine resistance 50 years ago, drug-resistant malaria has posed a major and increasing problem in malaria control (Hastings and Mackinnon, 1998; Anderson and Roper, 2005; Hastings and Watkins, 2005). Chloroquine resistance is now worldwide, while resistance to newer drugs is appearing in many regions, especially in South-east Asia, where multidrug resistance is a major public health problem (Wongsrichanalai et al., 2002; Roper et al., 2004). The growth in global travel and human migration is assumed to have caused this spread, with the speed of spread of resistance mirroring its expansion. Though chloroquine remained effective for some 20 years before signs of resistance emerged, it is unlikely that a similar period of grace can be realistically expected for recently deployed treatments given the current levels of global travel (Hartl, 2004).

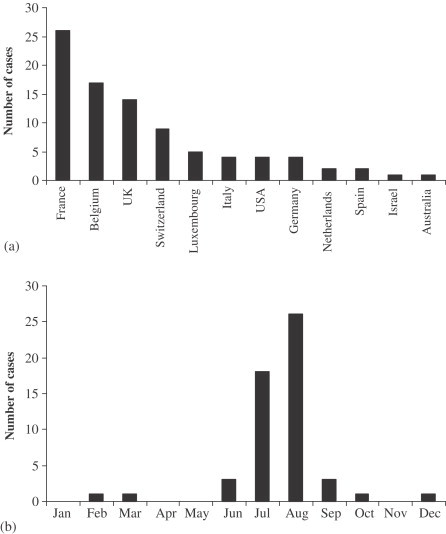

4.4.3. Airport Malaria

Airport malaria is acquired through the bite of an infected tropical Anopheline mosquito taken on persons whose geographical history firmly excludes exposure to the vector in its natural habitat (Isaäcson, 1989). Between 1969 and 1999, 87 suspected cases were recorded, with almost all being P. falciparum and occurring in the proximity of Paris, Brussels and London airports (Giacomini and Brumpt, 1989; Isaäcson, 1989; Danis et al., 1996; Giacomini, 1998; Gratz et al., 2000), indicative of their air links and sufficient, if only seasonal, climatic similarity with SSA (Tatem et al., 2006b). Figure 6 summarises the locations and time of year of these probable airport malaria cases. An. gambiae s.l. mosquitoes have been shown to survive long haul flights (Misao and Ishihara, 1945; Russell, 1987, Russell, 1989). For example, in a three-week period in 1994, it was estimated that 2000–5000 Anopheline mosquitoes were imported into France by 250–300 aircraft arriving from malaria-endemic regions of Africa, at the rate of 8–20 Anopheline mosquitoes per flight (Gratz et al., 2000). The ever expanding global transport network, increased travel to malaria-endemic countries and a decline in aircraft disinsection (Gratz et al., 2000), mean the numbers of malaria-infected Anopheles arrivals will only increase, resulting in more cases of airport malaria.

Figure 6.

(a) Countries in which confirmed or probable cases of airport malaria have been reported. (b) Month in which suspected European airport malaria cases occurred (where date is provided). (Data taken from Alos et al., 1985; Csillag, 1996; Danis et al., 1996; Giacomini, 1998; Giacomini and Brumpt, 1989; Giacomini and Mathieu, 1996; Giacomini et al., 1995; Gratz et al., 2000; Guillet et al., 1998; Hemmer, 1999; Holvoet et al., 1982; Isaäcson, 1989; Isaäcson and Frean, 2001; Jafari et al., 2002; Karch et al., 2001; Kruger et al., 2001; Lusina et al., 2000; Majori et al., 1990; Mangili and Gendreau, 2005; Mantel et al., 1995; Mouchet, 2000; Praetorius et al., 1999; Shpilberg et al., 1988; Signorelli and Messineo, 1990; Smith and Carter, 1984; Thang et al., 2002; Toovey and Jamieson, 2003; Van den Ende et al., 1996; Whitfield et al., 1984.)

4.5. Predicting Future Vector-Borne Disease Movement

The establishment of a vector-borne disease in a new area from an endemic region can be caused either by movement of an infected host and availability of competent vectors in the new area, or the invasion, if only temporarily, of an infected vector. Here, we extend the methodology outlined in Section 3.5 and review the approaches outlined in Tatem et al. (2006b) to examine the latter in terms of a basic exploratory analysis of the monthly risks of P. falciparum malaria-infected An. gambiae importation by plane from Africa, causing consequent autochthonous transmission. While globally, the movement of P. vivax malaria-infected mosquitoes may occur more frequently and pose more of an invasion risk to many regions, it is the movement of P. falciparum-infected Anopheles that has resulted in numerous airport malaria cases. Additionally, the possible effects of invasion of malaria endemic regions by An. gambiae have been seen in the devastating malaria epidemics in Brazil and Mauritius (Lounibos, 2002). The likelihood, however, of a more than very temporary establishment of P. falciparum or An. gambiae through air travel to Europe and many other locations remains low. Unsuitable year-round climate, An. gambiae's intolerance of urban areas (Hay et al., 2005) and competition from local mosquitoes that are inefficient vectors of P. falciparum all provide barriers to establishment.

Malaria caused by P. vivax and vectored predominantly by Anopheles atroparvus was a common cause of death in the marshes or wetlands of England during the 19th and 20th centuries (Kuhn et al., 2003), with the last autochthonous cases reported in 1953 (Crockett and Simpson, 1953). Although malaria has been eradicated in the UK, re-introduction is theoretically possible (Hay et al., 2000). This risk is negligible, however, as the majority of the former habitats of An. atroparvus have disappeared and returning travellers are rapidly diagnosed and treated, and in any case rarely live near suitable vector habitats (Kuhn et al., 2003). This is supported by the analyses presented above and the fact that not one of the 52 000 imported malaria cases reported since 1953 has led to a secondary case. The growth of travel to Africa therefore presents a negligible risk of the establishment of malaria in the UK.

The approach described here follows on from that described in Section 3.5 and full details are given in Tatem et al. (2006b). Monthly gridded climatologies were acquired (New et al., 2002) and used to create climatic signatures for each airport, for each month of the year. Climate dissimilarity matrices were created for each month, and these were clustered hierarchically to create 12 global airport dendrograms, one for each month of the year. Airport malaria cases represent instances where imported infected mosquitoes have caused autochthonous malaria transmission and, therefore, were used to define climatic suitability thresholds on each dendrogram. Malaria seasonality maps for Africa (Tanser et al., 2003) were used to identify the timing of the principal malaria transmission season at each SSA airport to identify when exported Anopheles were most likely to be malarious. Finally, the situation in 2000 was examined using the air traffic database described in Section 3.5, and future risks of opening new air routes were examined by analysing climatic similarities between airports and synchrony with malaria transmission seasons.

Table 3 shows the 18 routes identified as at risk for P. falciparum-infected mosquito importation and consequent autochthonous transmission for 2000. Comparison with Figure 6 shows excellent correspondence with the timing and location of actual suspected cases of infected-mosquito importation and autochthonous transmission. The relative risks suggest that the high traffic volumes on the Abidjan to Paris route in August, when both have sufficiently similar climates and Côte d’Ivoire is experiencing its principal malaria transmission season, makes this the most likely route for airport malaria occurrence.

Table 3.

Year 2000 air travel risk routes for possible temporary P. falciparum-infected An. gambiae invasion and subsequent autochthonous transmission

| Rank | From | To | Month | Risk relative to route 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Abidjan | Côte d’Ivoire | Paris Charles de Gaulle | France | August | 1.00 |

| 2 | Accra | Ghana | Amsterdam Schippol | Netherlands | July | 0.26 |

| 3 | Entebbe/Kampala | Uganda | Brussels | Belgium | July | 0.26 |

| 4 | Accra | Ghana | Amsterdam Schippol | Netherlands | September | 0.22 |

| 5 | Abidjan | Côte d’Ivoire | Brussels | Belgium | August | 0.21 |

| 6 | Accra | Ghana | Rome Fiumicino Apt | Italy | September | 0.18 |

| 7 | Abidjan | Côte d’Ivoire | Zurich | Switzerland | July | 0.17 |

| 8 | Accra | Ghana | Rome Fiumicino | Italy | August | 0.17 |

| 9 | Abidjan | Côte d’Ivoire | London Gatwick | United Kingdom | August | 0.12 |

| 10 | Cotonou | Benin | Brussels | Belgium | August | 0.06 |

| 11 | Libreville | Gabon | Rome Fiumicino | Italy | July | 0.06 |

| 12 | Cotonou | Benin | Paris Charles de Gaulle | France | August | 0.05 |

| 13 | Lome | Togo | Brussels | Belgium | August | 0.05 |

| 14 | Accra | Ghana | London Gatwick | United Kingdom | July | 0.05 |

| 15 | Entebbe/Kampala | Uganda | London Gatwick | United Kingdom | July | 0.04 |

| 16 | Libreville | Gabon | Dubai | United Arab Emirates | July | 0.03 |

| 17 | Abidjan | Côte d’Ivoire | Frankfurt | Germany | August | 0.01 |

| 18 | Entebbe/Kampala | Uganda | London Heathrow | United Kingdom | July | 0.01 |

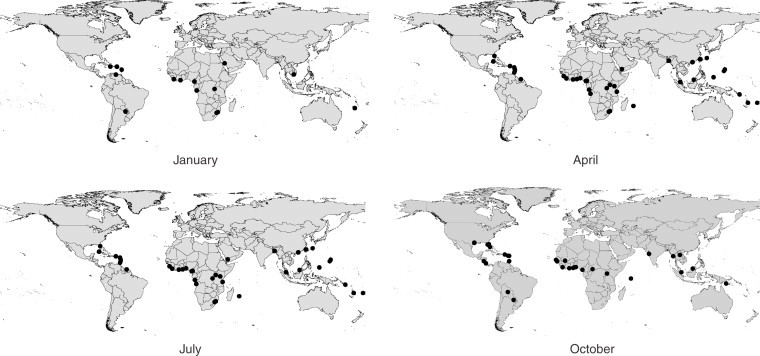

Figure 7 shows those sets of SSA airports and non-SSA airports similar enough climatically in January, April, July and October for P. falciparum-infected mosquito invasion. The results indicate that many airports in other regions of the world are more favourable climatically for Anopheles survival, and for many more months of the year than European destinations. The concentration of major airports in the temperate north means that July (summer in this region) on Figure 7 shows the largest number of potentially suitable destinations climatically, mainly linked to West African airports, including those in Europe where most SSA air traffic is directed, causing cases of airport malaria in the summer months particularly in unusually hot and humid periods. The other three months on Figure 7 show considerably fewer at risk airports, though throughout the year, Caribbean and Central American airports are highlighted consistently, indicating that their climates vary in synchrony most closely with the cycle of African malaria transmission seasons.

Figure 7.

Non-SSA airports that are similar enough climatically to the SSA airports within their primary malaria transmission season for possible P. falciparum-infected Anopheles invasion to occur.

The current heavy bias of SSA air traffic to European destinations has resulted in around two cases a year of airport malaria in the summer months, when particularly hot and humid conditions can be suitable for temporary Anopheles survival, and occur in synchrony with West African transmission seasons. The effects of opening up new air routes from malaria-endemic African countries to non-European destinations, where conditions are more suitable for Anopheles survival and are synchronous with African malaria transmission seasons year-round, could therefore have serious and largely unexpected consequences.

5. Conclusions

Increases in global travel are occuring simultaneously with many other processes that favour the emergence of disease (Wilson, 1995). Travel is a potent force in disease emergence and spread, whether it is aircraft moving human-incubated pathogens, or insect vectors, great distances in short times, or ships transporting used tyres containing mosquito eggs. The speed and complexity of modern transport make both geographical space and the traditional ‘drawbridge’ strategy of disease control and quarantine increasingly irrelevant (Haggett, 2000). With no apparent end in sight to the continued growth in global air travel and shipborne trade, we must expect the continued appearance of communicable disease pandemics, disease vector invasions and vector-borne disease movement. Approaches that can model, predict and explain such events can be used to focus surveillance and control efforts efficiently. This review has shown that the risk of movement of infectious diseases and their vectors through the global transportation network can be predicted to provide such information. Future challenges must focus on incorporating information on temporal variations in passenger numbers, stopover risks, intra-species competition, human populations at risk, breeding site availability, possible climate change, disinsection and land transport, as well as quantifying the relative importance of all types of transport for vector and disease movement.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to David Bradley, Dennis Shanks, Robert Snow, Marius Gilbert, Sarah Randolph, Willy Wint, Carlos Guerra, Briony Boon, Rebecca Freeman-Grais and the series editors for comments on this manuscript. SIH and AJT are funded by a Research Career Development Fellowship (to SIH) from the Wellcome Trust (#069045). We are especially grateful to John Drake for the generous supply of sea traffic data.

References

- Alibek K. Smallpox: a disease and a weapon. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2004;8S2:S3–S8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson R.M., May R.M. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1991. Infectious Diseases of Humans: Dynamics and Control. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson T.J.C., Roper C. The origins and spread of antimalarial drug resistance: lessons for policy makers. Acta Tropica. 2005;94:269–280. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey N.T.J. Wiley; London: 1967. The Mathematical Approach to Biology and Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- Barretto A., Aragon M., Epstein R. Bubonic plague outbreak in Mozambique 1994. Lancet. 1994;345:983–984. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90730-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozzette S. A model for smallpox vaccination policy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;348:416–425. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa025075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfman M.N., Leyva R., Negroni M.J., Rueda C.M. Mobile populations and HIV/AIDS in Central America and Mexico: research for action. AIDS. 2002;16:S42–S49. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200212003-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash R.A., Narasimhan V. Impediments to global surveillance of infectious diseases: consequences of open reporting in a global economy. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2000;78:1358–1367. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC Aedes albopictus infestation—United States. Epidemiologic Notes and Reports Update. 1986;35:649–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevallier E., Grand A., Azais J.-M. Spatial and temporal distribution of cholera in Ecuador between 1991 and 1996. European Journal of Public Health. 2004;14:274–279. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/14.3.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cieslak T.J., Eitzen E.M. Clinical and epidemiologic principles of anthrax. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 1999;5:552–555. doi: 10.3201/eid0504.990418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox N.J., Subbarao K. Global epidemiology of influenza: past and present. Annual Reviews of Medicine. 2000;51:407–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.51.1.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockett G.S., Simpson K. Malaria in neighbouring Londoners. British Medical Journal. 1953;21:1141. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.4846.1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin P.D. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1995. Death by Migration: Europe's Encounter with the Tropical World in the Nineteenth Century. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danis M., Mouchet J., Giacomini T. Autochthonous and introduced malaria in Europe. Medecine et Maladies Infectieuses. 1996;26:393–396. doi: 10.1016/s0399-077x(96)80181-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauphin G., Zientara S., Zeller H., Murgue B. West Nile: worldwide current situation in animals and humans. Comparative Immunology Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2004;27:343–355. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewan P.K., Fry A.M., Laserson K., Tierney B.C., Quinn C.P., Hayslett J.A., Broyles L.N., Shane A., Winthrop K.L., Walks I., Siegel L., Hales T., Semenova V.A., Romero-Steiner S., Elie C., Khabbaz R., Khan A.S., Hajjeh R.A., Schuchat A. Inhalational anthrax outbreak among postal workers, Washington, DC, 2001. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2002;8:1066–1072. doi: 10.3201/eid0810.020330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond J. Vintage; London: 1998. Guns, Germs and Steel: A Short History of Everybody for the Last 13000 Years. [Google Scholar]

- Drake J.M., Lodge D.M. Global hot spots of biological invasions: evaluating options for ballast-water management. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 2004;271:575–580. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duplaix N. Fleas. The lethal leapers. National Geographic. 1988;173:114–136. [Google Scholar]

- Dye C., Gay N. Modeling the SARS epidemic. Science. 2003;300:1884–1885. doi: 10.1126/science.1086925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert E. The retreat of plague from central Europe, 1640–1720: a geomedical approach. Bulletin of Historical Medicine. 2000;74:1–28. doi: 10.1353/bhm.2000.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effler P.V., Pang L., Kitsutani P., Vorndam V., Nakata M., Ayers T., Elm J., Tom T., Reiter P., Rigau-Perez J.G., Hayes J.M., Mills K., Napier M., Clark G.C., Gubler D.J. Dengue fever, Hawaii, 2001–2002. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005;11:742–749. doi: 10.3201/eid1105.041063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enserink M. Looking the pandemic in the eye. Science. 2004;306:392–394. doi: 10.1126/science.306.5695.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERDAS . 7th edn. ERDAS Inc; Atlanta: 2003. ERDAS Field Guide. [Google Scholar]

- Faruque S.M., Chowdhury N., Kamruzzaman M. Reemergence of epidemic Vibrio cholerae Q139, Bangladesh. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2003;9:1116–1122. doi: 10.3201/eid0909.020443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson N.M., Donnelly C.A., Anderson R.M. The foot and mouth epidemic in Great Britain: pattern of spread and impact of interventions. Science. 2001;292:1150–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1061020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson N.M., Galvani A.P., Bush R.M. Ecological and immunological determinants of influenza evolution. Nature. 2003;422:428–433. doi: 10.1038/nature01509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson N.M., Keeling M.J., Edmunds W.J., Gani R., Grenfell B.T., Anderson R.M., Leach S. Planning for smallpox outbreaks. Nature. 2003;425:681–685. doi: 10.1038/nature02007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouchier R., Kuiken T., Rimmelzwaan G., Osterhaus A. Global task force for influenza. Nature. 2005;435:419–420. doi: 10.1038/435419a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank C., Schoneberg I., Krause G., Claus H., Ammon A., Stark K. Increase in imported dengue, Germany, 2001–2002. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004;10:903–906. doi: 10.3201/eid1005.030495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage K.L., Kosoy M.Y. Natural history of plague: perspectives from more than a century of research. Annual Review of Entomology. 2005;50:505–528. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.50.071803.130337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galimand M. Multidrug resistance in Yersinia pestis mediated by transferable plasmid. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;337:677–680. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709043371004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacomini T. Malaria in airports and their neighbourhoods. Revue du Praticien. 1998;48:264–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacomini T., Brumpt L.C. Passive dissemination of Anopheles by means of transport: its role in the transmission of malaria (historical review) Revue Histoire Pharmacie. 1989;36:164–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould P.R. The geography of AIDS: study of human movement and the expansion of an epidemic. La Recherche. 1995;280:36–37. [Google Scholar]

- Gould P.R. Syracuse University Press; Syracuse: 1999. Becoming a Geographer. [Google Scholar]

- Grais R.F., Ellis J.H., Glass G.E. Assessing the impact of airline travel on the geographic spread of pandemic influenza. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;18:1065–1072. doi: 10.1023/a:1026140019146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grais R.F., Ellis J.H., Glass G.E. Forecasting the geographical spread of smallpox cases by air travel. Epidemiology and Infection. 2003;131:849–857. doi: 10.1017/s0950268803008811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granwehr B.P., Lillibridge K.M., Higgs S., Mason P.W., Aronson J.F., Campbell G.A., Barrett A.D.T. West Nile virus: where are we now? Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2004;4:547–556. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz N.G. Critical review of the vector status of Aedes albopictus. Medical and Veterinary Entomology. 2004;18:215–227. doi: 10.1111/j.0269-283X.2004.00513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz N.G., Steffen R., Cocksedge W. Why aircraft disinsection? Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2000;78:995–1004. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene C.M., Reefhuis J., Tan C., Fiore A.E., Goldstein S., Beach M.J., Redd S.C., Valiante D., Burr G., Buehler J., Pinner R.W., Bresnitz E., Bell B.P. Epidemiologic investigations of bioterrorism-related anthrax, New Jersey, 2001. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2002;8:1048–1055. doi: 10.3201/eid0810.020329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubler D.J. The global emergence/resurgence of arboviral diseases as public health problems. Archives of Medical Research. 2002;33:330–342. doi: 10.1016/s0188-4409(02)00378-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubler D.J. Aedes albopictus in Africa. Lancet. 2003;3:751–752. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00826-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubler D.J. The changing epidemiology of yellow fever and dengue, 1900 to 2003: full circle? Comparative Immunology Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2004;27:319–330. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubler D.J. Cities spawn epidemic dengue viruses. Nature Medicine. 2004;10:129–130. doi: 10.1038/nm0204-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubler D.J., Clark G.C. Dengue/dengue hemorrhagic fever: the emergence of a global health problem. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 1995;1:55–57. doi: 10.3201/eid0102.952004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]