Abstract

Introduction

Self poisoning is a public health problem in Sri Lanka. A new laundry detergent consisting of a sachet each of 1.2g of potassium permanganate (KMNO4) and 12.5g of oxalic acid has become a popular agent amongst the youth for self poisoning.

Method

Prospective clinical data and major outcomes were recorded in all patients admitted to a referring and a referral hospital. Serial biochemistry was performed in 20 patients. Post-mortem examinations were performed in some patients.

Results

There were 115 patients. Majority developed symptoms of the gastrointestinal tract within the first 24 hours. There were 18 deaths. Ingestion of oxalic acid was associated with a case fatality ratio (CFR) of 25.4% (95% CI 14-39) while ingestion of both KMNO4 and oxalic acid was associated with a CFR of 9.8% (95% CI 3.2-21). Ingestion of more than one sachet was associated with a significantly higher risk of death (risk ratio 13.26, (95% CI 3.2-54; p<0.05). Majority of the deaths occurred within an hour since ingestion. Post-mortem examinations revealed mucosal ulceration in the majority of deaths.

Discussion

This case series brings to light an emerging epidemic of fatal self poisoning in Sri Lanka from a compound that is not regulated. As deaths occur soon after ingestion medical management of these patients is bound to be difficult.

Conclusion

This case series highlights a fatal mode of self poisoning that could be controlled through regulation of the manufacture and sale of the product.

Introduction

Self poisoning is a major public health problem in rural Sri Lanka with an estimated 315 to 364 per 100,000 population per year attempting self poisoning each year1-3. Seventy five percent of poisoning deaths in patients under 25years are due to ingestion of paraqaut and oleander while 80% of deaths in patients over 25 years are due to ingestion of pesticides, organophosphorus compounds in particular contributing to 40% of deaths 4 in some areas of the Island.

Self poisoning due to newer agents is a continually evolving problem and introduces new challenges particularly if there is a lack of prior human data on clinical features, biochemical abnormalities and case fatality or if existing data is not effectively communicated to clinicians or regulators.

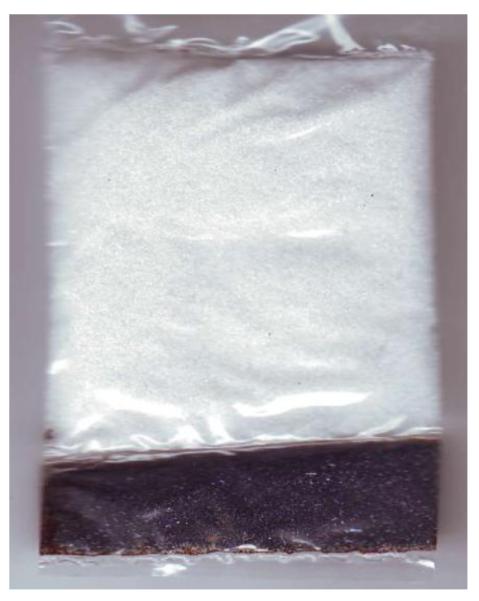

As part of an ongoing cohort study we noted a number of admissions following ingestion of a laundry detergent during 2006. This laundry detergent is marketed as two sachets (figure 1), containing 1.2g of Potassium permanganate (KMNO 4) and 12.5g of oxalic acid by many small scale manufacturers and is available under several trade names. The manufacturers recommend that clothes should be soaked in KMNO4 for 2 hours and washed with dissolved oxalic acid afterwards. This laundry detergent has become popular as a remover of stains over the other commercially available products and traditionally had been used to remove fungus from clothes. We report the first case series of an emerging problem of self poisoning with a newer household laundry detergent in Southern Sri Lanka.

Figure1.

Laundry detergent sachet. Top half contains 12.5g of oxalic acid, the bottom half contains 1.2g of KMNO4

Potassium permanganate (CAS 7722-64-7) is an antiseptic and astringent agent with powerful oxidizing effects, recommended as a disinfectant and a fixative and stain in microscopy. The crystalline and concentrated forms are corrosive due to the release of potassium hydroxide when they come in contact with water. Potassium permanganate may also oxidize ferrous (Fe2+) to ferric (Fe3+) of haemoglobin, the resultant methaemoglobinaemia is incapable of carrying oxygen effectively, leading to functional anaemia and cellular hypoxia. The quoted oral rat LD 50 for KMNO4 is 1090mg/Kg5.

Oxalic acid (CAS 6153-56-6) is a colourless, crystalline, toxic organic compound used as a reducing agent in photography, bleaching and dust removal. Human reports of clinical toxicology are relatively rare but include local corrosive effects, formation of oxalate calcium complex resulting in hypocalcaemia and renal toxicity The quoted oral rat LD50 for oxalic acid is 7500mg/kg6 .

Method

Study design, setting and patients

Prospective data was collected from a primary hospital and a tertiary referral hospital to establish case fatality ratio (CFR) and clinical signs and to minimise the effects of referral bias. Prospective clinical information (symptoms (table 1), pulse rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate and biochemical data (table1)) was collected on all patients presenting to a large referral hospital in South of Sri Lanka (General Hospital Karapitiya (GHK)) with a history of poisoning with the laundry detergent between January 2007 and September 2008. This study was nested into an ongoing cohort of all human self poisoning which has ethical approval from Ethical Review Committees of Sri Lanka Medical Association (SLMA) and University of Ruhuna. Exposure was confirmed by positive identification of the product labels. Demographic details including the time of ingestion, amount ingested and co ingestants, clinical observations and major outcomes were recorded by on site study physicians twice daily on specifically designed data collection forms until death or discharge and data were fed into a purpose designed clinical database on a handheld computer. Serial blood and urine samples were taken from consenting patients for the estimation of renal and liver function.

Table 1.

symptoms, signs and biochemistry of prospective admissions

| KMNO4+ Oxalic acid N=51 |

KMNO4 N=13 |

Oxalic acid N=51 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ingested Amount* | KMNO41.2g (IQR 1.2- 2.4) |

OA 12.5g (IQR 12.5-25). |

1.2g (1.2- 12.2) |

12.5g (IQR 12.5- 12.5). |

| Age* | 24 (IQR 20-28) | 19(16-34) | 24(19-37.5) | |

| Hospital Stay Days* | 4 (IQR 4-5) | 4(IQR4-5) | 4 (IQR 4-5). | |

| Deaths and CFR (95%CI) |

5, 9.8(3.2-21) | 0 | 13, 25.4(14-39) | |

| Epigastric pain nausea, vomiting (%) |

95 | 73 | 60 | |

| Haematemesis (%) | 10 | 0 | 16 | |

| Weakness and headache (%) |

20 | 27 | 30 | |

| Serum creatinine* | 1.7(0.91-4.4) | NA | NA | |

| SGPT* (IU/L) | 25.5(10-43.5) | NA | NA | |

| Na* (mmol/L) | 135(130-144) | NA | NA | |

| K* (mmol/L) | 4.1(3.8-4.2) | NA | NA | |

| Laryngeal oedema | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Skin burns | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

median and inter quartile range.; SGPT= serum glutamic pyruvic transferase; NA= not available; 95%CI= 95% confidence Interval

At the district hospital Hiniduma (DHH), medical officer in charge (MAK) has been collecting prospective data independent of the main cohort described above. Major outcomes, basic demography, transfer patterns and post mortem findings of patients presenting with self poisoning with the detergent were incorporated in to the study. All transferred patients were followed up at the GHK.

A retrospective review of post-mortem records was undertaken in 4 other referring hospitals of the south (District Hospital Akuressa- DHA, District Hospital Morawaka- DHM and District Hospital Deniyaya- DHD and a large General Hospital Matara –GHM) to establish if the problem is widespread in the province. We also searched the database of 20000 prospective admissions with self poisoning in 2 other provinces of Sri Lanka to determine whether the problem was localised to the province.

Results

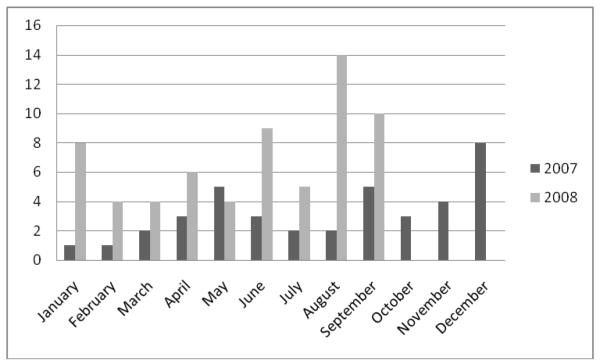

At the referral hospital (GHK) there were 1995 patients with self poisoning admitted during the study period. Laundry detergent was ingested by 103 (61 females) patients accounting for 5.2% of all cases admitted with self poisoning to GHK during the study period. During the first 10 months in 2007, there were 24 patients while during the same period in 2008, there were 64 patients (figure 2). All survivors had a median blood pressure of 116/76mmHg (IQR110-120), pulse of 83(IQR77-88), median respiratory rate of 19(IQR18-20) and median Glasgow Coma Scale of 15 on admission to hospital.

Figure 2.

Cases of self poisoning with the laundry detergent admitted to GHK during 2007 and 2008

Combined, GHK and DHH received 115 patients with self poisoning with the laundry detergent. 42 patients dissolved the contents in water while the remainder ingested the solid form of the detergent. 113 patients ingested this detergent for deliberate self harm while a pregnant patient ingested it as an abortifacient and there was one accidental ingestion. Majority of the patients developed symptoms of the gastrointestinal tract within the first 24 hours (table1). There were 18 deaths (12 at DHH and 6 at GHK). 51 patients ingested both KMNO4 and oxalic acid of whom 5 died. 51 ingested oxalic acid alone and 13 patients died. 13 patients ingested KMNO4 alone and there were no deaths. Ingestion of oxalic acid was associated with an overall CFR of 25.4% (95% CI 14-39) while ingestion of both KMNO4 and oxalic acid was associated with an overall CFR of 9.8% (95% CI 3.2-21). 12 out of 26 patients admitted to DHH died (CFR (46.2% (95% CI 27.9-65.2)).

Number of sachets ingested was accurately recordable in 93 patients. 35 patients ingested two or more sachets of both KMNO4 and oxalic acid and 16 patients died. 58 patients ingested one or less and only 2 died. Ingestion of more than one sachet is associated with a significantly higher risk of death (risk ratio 13.26, (95% CI 3.2-54; p<0.05).

The retrospective survey identified 21 additional deaths at three other hospitals of the South. All these deaths occurred within a few hours since ingestion. DHA recorded no deaths. The main database did not reveal patients in the other provinces.

At DHH eleven patients died within one hour of ingestion in transit to the hospital while the 12th patient who was admitted soon after ingestion with an un-recordable blood pressure died within 20 minutes of admission. At GHK, 4 patients died within 24 hours of ingestion. One patient developed ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation as the immediate cause of death. Patients who died within 24 hours were all hypotensive (<70mmHg) on admission. Two patients died at 11 and 13 days post ingestion with renal failure and septicaemia.

Post-mortem examination was performed in all acute deaths (16). There was macroscopic evidence of superficial oesophageal erosions, orophyarynx and larynx in all the patients. Some patients had pale and swollen kidneys. One patient had cerebral oedema and two had congested lungs. One patient had bleeding in to the pericardium and adrenal glands.

Serial biochemistry was performed in 20 consenting patients who ingested both KMNO4 and oxalic acid. Median serum creatinine was 1.7mg/dL ( IQR 0.91 - 4.4- normal range: 0.5-1.3mg/dL) on day 2. Median serum creatinine on day 3 was 1.15mg/L (IQR 0.86-4.1). 35% of patients had red cells in urine on day 2 and 3 post ingestion. 28% had evidence of renal failure (raised creatinine over 1.3mg/L) by the third day of self ingestion. Two patients required haemodialysis and both survived. Serum Na, K, and SGPT remained within normal limits. All survivors were treated symptomatically with intravenous fluid replacement, pain relief with paracetamol and proton pump inhibitors when indicated.

Discussion

This case series brings to light an emerging epidemic of self poisoning due to a new laundry detergent freely available over the counter in Sri Lanka. An examination of databases which includes data from other regions of Sri Lanka shows that these poisonings were localised to the southern province. This detergent has become popular as the variation of presentations between referral hospitals suggests that there may be geographic localisation within the province.

Most deaths occurred early at the primary hospital and were associated with high amounts of ingestion of oxalic acid. The lower rate of death in the referral hospital probably reflects a survivor bias due to smaller ingestions. Only 2 deaths occurred after 24 hours. Late causes of death and morbidity were contributed by renal failure, a well recognised effect of calcium oxalate 7,8

The major contributor to death appears to be oxalic acid as none in the KMNO4 group died while 13 in the oxalic acid group and 5 in the KMNO4 + oxalic acid group died.

Given the short interval between ingestion and death, a cardiac cause is likely, possibly from severe hypocalcaemia due to the formation of calcium oxalate complexes. This has been reported in human cases of ethylene glycol poisoning 9,10 and is supported by the fact that no apparent cause of death being found in post-mortem and documentation of fatal cardiac arrhythmia in one of our cases. However, we could not estimate serum calcium levels in these patients.

A further mechanism may be direct mitochondrial toxicity and severe tissue hypoxia. Calcium oxalate has been shown to be a mitochondrial poison in experimental models11,12 . It could be assumed that oxalic acid can induce mitochondrial toxicity in other organs leading to death. We could not estimate serum lactate levels or an anion gap to support this possibility. Acute laryngeal oedema and hypoxia that was seen in one of the cases may be another possibility.

Sub lethal doses of oxalic acid and KMNO4 taken in combination lead to renal failure 2 to 3 days after ingestion which in the majority settle with supportive care, only a few requiring dialysis.

Renal failure associated with oxalic acid ingestion is most likely due to a tubular defect as the majority improved with supportive care. Konta et al reported a case of reversible renal tubular dysfunction with electron microscopic evidence of deposition of oxalate crystals in the tubular epithelium7.

There were no deaths in the KMNO4 group. There have been a few reports of deaths in the literature. Ong et al reported a fatal case of KMNO4 due to disseminated intravascular coagulation, hepatic necrosis, Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS)and renal failure 6 days after ingestion13. While Middleton et al reported a fatal case due ingestion of 20g of KMNO4 who developed ARDS, cardiovascular collapse and haemorrhagic pancreatitis14. Methaemoglobinaemia(Meth-Hb) is a well known side effect of KMNO4 ingestion 15. We did not have the facility to estimate Meth-Hb levels. Meth-Hb formation is unlikely to have been a significant contributor to the deaths as there were only two deaths in patients who ingested KMNO 4 with oxalic acid.

Anecdotally there seemed to be a significant rise in the number of cases being seen over time. This was supported by the documented increase seen during our study. We believe that this increase is real as there has been no change in referral policy during that time. Sri Lanka has a history of poisonings that escalate quickly to epidemic proportions. The most notable being yellow oleander (Thevetia peruviana) which escalated from an index case in 1979 to account for 25% of poisoning admissions in some areas 16. There are a number of social and cultural factors that drive such outbreaks but ease of access remains an important determinant of use. Unlike oleander it is likely that this outbreak can be terminated with appropriate regulatory action. Within Sri Lanka the restriction of pesticides with similar case fatality rates has been associated with a reduction of overall suicide deaths 17. Roberts et al in their paper also demonstrated that banning of pesticides can reduce pesticide specific deaths (e.g.endosulfan) as importing these chemicals are highly regularized17. These actions have occurred in a framework of regulatory control for pesticides. While this level of regulatory control does not exist for household goods in Sri Lanka, measures should be taken and implemented to ban this laundry detergent without delay. Appropriate regulatory scrutiny of other household products too should be implemented.

Limitations

We were unable to perform serial biochemistry in all the patients. Histological examination of heart, lungs and kidneys would have added information on the cause of death. We could not estimate blood levels of oxalic acid or KMNO4 due to lack of laboratory facilities. However analytical validation of history within our cohort has been shown to be accurate in the past.

Conclusions

Ingestion of this new laundry detergent can be fatal. Majority of deaths occur soon after ingestion and medical treatment for this group of patients appears to be futile. However, adherence to basic and advanced life support should be emphasized and initiation of supportive care along with correction of metabolic abnormalities should be performed. Patients who survive 24 hours may develop self-limiting renal failure but deaths are rare. Number of cases has doubled in two years and regulation of manufacture and sale of this product may be necessary to prevent further deaths.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the research assistants attached to the South Asian Clinical Toxicology Research Collaboration (SACTRC). SACTRC is funded by Wellcome Trust & Australian National Health and Medical Research Council International Collaborative Capacity Building Research Grant (GR071669MA ) IG is funded by AusAID grant no ALA 000379.

References

- 1.Eddleston M, Sudarshan K, Senthilkumaran M, et al. Patterns of hospital transfer for self-poisoned patients in rural Sri Lanka: implications for estimating the incidence of self-poisoning in the developing world. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84(4):276–82. doi: 10.2471/blt.05.025379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manuel C, Gunnell DJ, van der Hoek W, Dawson A, Wijeratne IK, Konradsen F. Self-poisoning in rural Sri Lanka: small-area variations in incidence. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Hoek W, Konradsen F. Analysis of 8000 hospital admissions for acute poisoning in a rural area of Sri Lanka. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2006;44(3):225–31. doi: 10.1080/15563650600584246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eddleston M, Gunnell D, Karunaratne A, de Silva D, Sheriff MH, Buckley NA. Epidemiology of intentional self-poisoning in rural Sri Lanka. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:583–4. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.6.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The physical and chemical theoritical chemistry laboratory, Oxford University [Accessed 15.02.2009];Chemical and other safety information. safety data for potassium permanganate. at. http://msds.chem.ox.ac.uk/PO/potassium_permanganate.html.

- 6.The physical and chemical theoritical chemistry laboratory, Oxford University [Accessed 15.02.2009];Chemical and other safety information. safety data for oxalic acid. at. http://msds.chem.ox.ac.uk/OX/oxalic_acid_dihydrate.html.

- 7.Konta T, Yamaoka M, Tanida H, Matsunaga T, Tomoike H. Acute renal failure due to oxalate ingestion. Intern Med. 1998;37(9):762–5. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.37.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hess R, Bartels MJ, Pottenger LH. Ethylene glycol: an estimate of tolerable levels of exposure based on a review of animal and human data. Arch Toxicol. 2004;78(12):671–80. doi: 10.1007/s00204-004-0594-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Introna F, Jr., Smialek JE. Antifreeze (ethylene glycol) intoxications in Baltimore. Report of six cases. Acta Morphol Hung. 1989;37(3-4):245–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simpson E. Some aspects of calcium metabolism in a fatal case of ethylene glycol poisoning. Ann Clin Biochem. 1985;22(Pt 1):90–3. doi: 10.1177/000456328502200110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao LC, Honeyman TW, Cooney R, Kennington L, Scheid CR, Jonassen JA. Mitochondrial dysfunction is a primary event in renal cell oxalate toxicity. Kidney Int. 2004;66(5):1890–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McMartin KE, Wallace KB. Calcium oxalate monohydrate, a metabolite of ethylene glycol, is toxic for rat renal mitochondrial function. Toxicol Sci. 2005;84(1):195–200. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ong KL, Tan TH, Cheung WL. Potassium permanganate poisoning--a rare cause of fatal self poisoning. J Accid Emerg Med. 1997;14(1):43–5. doi: 10.1136/emj.14.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Middleton SJ, Jacyna M, McClaren D, Robinson R, Thomas HC. Haemorrhagic pancreatitis--a cause of death in severe potassium permanganate poisoning. Postgrad Med J. 1990;66(778):657–8. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.66.778.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahomedy MC, Mahomedy YH, Canham PA, Downing JW, Jeal DE. Methaemoglobinaemia following treatment dispensed by witch doctors. Two cases of potassium permanganate poisoning. Anaesthesia. 1975;30(2):190–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1975.tb00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eddleston M, Ariaratnam CA, Meyer WP, et al. Epidemic of self-poisoning with seeds of the yellow oleander tree (Thevetia peruviana) in northern Sri Lanka. Trop Med Int Health. 1999;4(4):266–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1999.00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts DM, Karunarathna A, Buckley NA, Manuweera G, Sheriff MH, Eddleston M. Influence of pesticide regulation on acute poisoning deaths in Sri Lanka. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81(11):789–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]