Abstract

MECP2 mutations are responsible for two different phenotypes in females, classical Rett syndrome and the milder Zappella variant (Z-RTT). We investigated whether Copy Number Variants (CNVs) may modulate the phenotype by comparison of array-CGH data from two discordant pairs of sisters and four additional discordant pairs of unrelated girls matched by mutation type. We also searched for potential MeCP2 targets within CNVs by ChIP-chip analysis. We did not identify one major common gene/region, suggesting that modifiers may be complex and variable between cases. However, we detected CNVs correlating with disease severity that contain candidate modifiers. CROCC (1p36.13) is a potential MeCP2 target in which a duplication in a Z-RTT and a deletion in a classic patient were observed. CROCC encodes a structural component of ciliary motility that is required for correct brain development. CFHR1 and CFHR3, on 1q31.3, may be involved in the regulation of complement during synapse elimination and were found to be deleted in a Z-RTT but duplicated in two classic patients. The duplication of 10q11.22, present in two Z-RTT patients, includes GPRIN2, a regulator of neurite outgrowth and PPYR1, involved in energy homeostasis. Functional analyses are necessary to confirm candidates and to define targets for future therapies.

Keywords: Rett syndrome, Copy Number Variants, modifier genes

Introduction

Rett syndrome (RTT, OMIM#312750) is an X-linked neurodevelopmental disorder predominantly affecting females. In the classic form, after a period of normal development (6-18 months), patients show growth retardation and regression of speech and purposeful hand movements, with appearance of stereotyped hand movements, microcephaly, autism, seizures.1, 2 RTT syndrome has a wide spectrum of clinical phenotypes including: the Zappella variant (Z-RTT), the early onset seizure variant and the congenital variant.3 Z-RTT, firstly described by M. Zappella in 1992, represents the most common RTT variant. Z-RTT is characterized by a recovery of the ability to speak in single words or third person phrases and by an improvement of purposeful hand movements.4, 5 Z-RTT patients also show milder intellectual disabilities (up to IQ of 50) and often normal head circumference, weight and height respect to classic RTT.5

De novo mutations in the MECP2 gene (Xq28) account for the majority of girls with classic RTT (95-97%) and for about half of cases with Z-RTT.5 The other two variants have been associated with different loci, with mutations in CDKL5 (Xp22) found in the early onset seizure variant and mutations in FOXG1 (14q13) found in the congenital variant.6-8

Only a few MECP2-mutated familial cases have been reported so far. Some cases have been explained by skewing of X-inactivation towards the wild-type allele in an asymptomatic carrier.9-11 In others cases, germline mosaicism has been a possible explanation.12-14

X-chromosome inactivation (XCI) is one important candidate factor modulating RTT phenotype. However, studies performed on blood yielded conflicting results. In 2007, Archer et al. performed the first systematic study of XCI in a large cohort of patients and found a correlation between the degree and direction of XCI in leucocytes and RTT severity.15 However, it has been shown that XCI may vary remarkably between tissues.16,17 Thus, the extrapolations of results based on sampling peripheral tissues, such as lymphocytes, to other tissues, such as brain, may be misleading. The few studies performed on human RTT brain tissues suggest that balanced XCI patterns are prevalent.16, 18-21 However, XCI has been investigated in a limited number of brain regions and no definitive conclusions can be drawn. In addition, previous studies demonstrated that other factors such as MECP2 mutation type and environment can influence RTT phenotype.5, 22,23 Since available data cannot fully explain RTT variability, it is likely that a combination of different factors cooperate in a complex manner to modulate the phenotype. In favor of this hypothesis, there are cases of RTT sisters with identical MECP2 mutation, balanced X-inactivation, similar environments and discordant phenotype (one classic and one Z-RTT sister).9,12

Copy Number Variations (CNVs) are segments of DNA ranging from kilobases (Kb) to multiple megabases (Mb) in length that contain a variable number of copies compared with the reference genome sequence. It has been demonstrated that CNVs are associated with detectable differences in transcript levels for genes within the CNV breakpoints that are predicted to have causative, functional effects in some cases. CNVs have been reported to be associated with human diseases such as neurological and autoimmune disorders and cancer.24-33 CNVs, to a greater extent than Single Nuclotide Polimorphisms (SNPs), represent an important source of variability in both phenotypically normal subjects and individuals with diseases.34, 35 It is therefore reasonable to hypothesize that CNVs can modulate the phenotypic expression of RTT syndrome.

In order to test this hypothesis, we analyzed by array-CGH two pairs of RTT sisters and four additional pairs of unrelated RTT girls matched by mutation type showing discordant phenotype (classic and Z-RTT). Complementary analysis of ChIP-chip data was also performed to identify hypothetical MeCP2 targets included in the identified CNVs.

Patients and Methods

Patients

From the Italian RTT database and biobank (www.biobank.unisi.it) we recruited two rare familial cases with two RTT sisters with discordant phenotype: one classic (#897 and #138) and one Z-RTT (#896 and #139).36 Blood DNA from these cases were screened by both denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (DHPLC) and multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) techniques to identify MECP2 mutations. The first pair carry a large MECP2 deletion in exon 3 and exon 4, while the second pair have a late truncating MECP2 mutation: c.1157del32. Clinical descriptions of these patients have been reported in previous manuscripts.9,12 Furthermore, we selected four additional pairs (#565/601, #185/119, #421/109, #402/368) of unrelated RTT patients with discordant severity of RTT phenotype (classic and Z-RTT) and the same MECP2 mutation (c.1163del26, p.R306C, c.1159del44, p.R133C) (Table 1 and 2). Chromosome X inactivation (XCI), tested using the assay as modified from Pegoraro et al., revealed that all patients show balanced XCI except for case #421 displaying a skewed XCI.37 All cases included in the bank have been clinically evaluated by the Medical Genetics Unit of Siena. Patients were classified in classic and RTT variant according to the international criteria.2, 38

Table 1.

CNVs classified as “likely modifiers” since they correlate with phenotypic RTT severity.

| Polymorphic CNVs | Breakpoints (bp) |

Gene content |

MeCP2_B promoter hits rank |

MeCP2_C promoter hits rank |

897 C/ 896 Z (Ex 3/4 del) |

138 C/ 139 Z (c.1157del32) |

565 C/ 601 Z (c.1163del26) |

185 C/ 119 Z (p.R306C) |

421 C/ 109 Z (c.1159del44) |

402 C/ 368 Z (p.R133C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1p36.13{426 kb} | 16,698,906- 17,124,554 |

ESPNP | 13822 | 22690 | Dup Z | Del C | ||||

| MSTP9 | - | - | ||||||||

| CROCC | 658 | 16300 | ||||||||

| 1q31.3{55 kb} | 195,011,34- 195,065,867 |

CFHR1 | 23144 | 7651 | Dup C | Amp C/ Del Z |

||||

| CFHR3 | 20253 | 6994 | ||||||||

| 1q42.12{139 kb} | 223,731,55- 223,870,819 |

ENAH | 18604 | 13553 | Dup Z | |||||

| 2p25.2{400 kb} | 3,060,975- 3,460,506 |

TSSC1 | 941 | 3174 | Del Z | |||||

| TTC15 | 20740 | 21641 | ||||||||

| 2q37.3{141 kb} | 242,514,59- 242,655,973 |

/ | - | - | Del Z | |||||

| 3q13.12{281 kb} | 110,116,09- 110,397,433 |

GUCA1C | 19293 | 6167 | Dup Z | |||||

| MORC1 | 18317 | 20394 | ||||||||

| C3orf66 | 12136 | 8147 | ||||||||

| 5p15.33{85 kb} | 763,944- 848,744 |

ZDHHC11 | 4349 | 13284 | Dup Z | |||||

| 6q27{210 kb} | 168,114,26- 168,324,002 |

MLLT4 | - | - | Dup Z | |||||

| C6orf54 | 2389 | 6671 | ||||||||

| KIF25 | 8778 | 3159 | ||||||||

| FRMD1 | 15800 | 10530 | ||||||||

| 7p21.3{89 kb} | 11,720,901- 11,809,763 |

THSD7A | 8520 | 8160 | Del Z | |||||

| 8q21.3{87 kb} | 87,136,222- 87,222,795 |

PSKH2 | 19413 | 9491 | Dup C | |||||

| ATP6VOD2 | 22858 | 4087 | ||||||||

| 10q11.22{172 kb} | 46,396,163- 46,568,496 |

GPRIN2 | 17343 | 23312 | Dup Z | Dup Z | ||||

| PPYR1 | 16722 | 9812 | ||||||||

| 14q32.33{125 kb} | 105,708,20- 105,833,372 |

SLK | 14769 | 10236 | Del Z | |||||

| COL17A1 | 4292 | 2579 | ||||||||

| 15q14{49 kb} | 32,523,241- 32,572,315 |

/ | - | - | Del Z | |||||

| 16p11{200 kb} | 34,399,543- 34,539,890 |

/ | - | - | Dup Z | |||||

| 22q13.2{49 kb} | 41,237,731- 41,287,060 |

SERHL | - | - | Dup Z | |||||

| SERHL2 | - | - |

Abbreviations: Amp, amplification; CNVs, copy number variants; C, classic; Del, deletion; Dup, duplication; Z, Z-RTT

Bold numbers are in the top 10% of MeCP2 promoter hits.

Table 2.

CNVs classified as “unlikely modifiers” since they were apparently not associated with phenotypic severity.

| Polymorphic CNVs | Breakpoints (bp) |

Gene content | MeCP2_B promoter hits rank |

MeCP2_C promoter hits rank |

897 C/ 896 Z (Ex 3/4 del) |

138 C/ 139 Z (c.1157del32) |

565 C/ 601 Z (c.1163del26) |

185 C/ 119 Z (p.R306C) |

421 C/ 109 Z (c.1159del44) |

402 C/ 368 Z (p.R133C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1q44{58 kb} | 246,794,522- 246,852,126 |

OR2T34 | 22567 | 14244 | Dup Z | Del C | Del C | Del Z | ||

| OR2T10 | 22348 | 8566 | ||||||||

| 2p11{494 kb} | 89,401,838- 89,895,566 |

*IGKV1-16D | - | - | Del Z | |||||

| 3q26{104 kb} | 163,997,228- 164,101,776 |

/ | - | - | Del C | Del Z | Del C/ Del Z |

|||

| 3q29{36 kb} | 196,905,767- 196,942,158 |

MUC20 | 17727 | 12873 | Dup C | DupC/ DupZ |

Dup C | Dup C | ||

| 4q13.2{108 kb} | 69,057,735- 69,165,814 |

UGT2B17 | 21719 | 18336 | Dup C | Del Z | Del C | |||

| 6p21.32{65 kb} | 29,939,288- 30004,636 |

HCG4P6 | Del C | Del Z | ||||||

| 6p21.33{77 kb} | 32,595,402- 32,672,983 |

HLA-DRB5 | Dup Z | Amp C | Amp C/ Amp Z |

|||||

| HLA-DRB1 | 11824 | 21879 | ||||||||

| 8p11.23{143 kb} | 39,356,595- 39,499,752 |

ADAM5P | 14070 | 2916 | Dup C | Dup C | *Amp Z | Amp C/ Amp Z |

Amp C/ Amp Z |

|

| 10q11.22{144 kb} | 47,017,598- 47,161,232 |

/ | - | - | Dup C | Dup Z | Dup Z | |||

| 14q11{860 kb} | 18,624,383- 19,484,013 |

OR11H13P | Del C | Dup C | ||||||

| OR4Q3 | 23539 | 330 | ||||||||

| OR4M1 | 24054 | 4686 | ||||||||

| OR4N2 | 23383 | 7030 | ||||||||

| OR4K2 | 21957 | 3567 | ||||||||

| OR4K5 | 21814 | 7944 | ||||||||

| OR4K1 | 23684 | 162 | ||||||||

| 15q11.2{727 kb} | 18,810,004- 19,537,035 |

/ | - | - | Del C | Del C | Del Z | Del C | ||

| 16p11.2{220 kb} | 28,732,295- 28,952,218 |

ATXN2L | - | - | Dup C | Dup Z | ||||

| TUFM | 7097 | 3848 | ||||||||

| SH2B1 | 12675 | 12680 | ||||||||

| ATP2A1 | 15182 | 23566 | ||||||||

| RABEP2 | 10298 | 16794 | ||||||||

| CD19 | 18469 | 15604 | ||||||||

| NFATC2IP | 23326 | 1627 | ||||||||

| SPNS1 | 1393 | 20317 | ||||||||

| LAT | 15145 | 14271 | ||||||||

| 17q21.31{163 kb} | 41,544,224- 41,706,870 |

KIAA1267 | - | - | Amp C/ Dup Z |

Dup Z | Dup Z | |||

| 22q11.23{30 kb} | 22,681,995- 22,712,211 |

GSTT1 | 9984 | 14237 | Dup Z | Dup C | Dup Z |

C: classic; Z: Z-RTT; Del: deletion; Dup: duplication; Amp: amplification.

16 isoforms

Genomic DNA isolation

Blood samples were obtained after informed consent. Genomic DNA of the patients was isolated from an EDTA preserved peripheral blood sample using the QIAamp DNA Blood Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Qiagen SPA, Milano, IT). Genomic DNA from normal male and female controls was obtained from Promega (Promega Italia SRL, Milano, IT). Ten micrograms (μgs) of genomic DNA from the patient (test sample) and the control (reference sample) were sonicated. Test and reference DNA samples were subsequently purified using affinity column purification (DNA Clean and Concentrator, Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) and the appropriate DNA concentrations were determined by a DyNA Quant™ 200 Fluorometer (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ. USA).

Array Comparative Genomic Hybridization

Array CGH analysis was performed using commercially available oligonucleotide microarrays containing approximately 99,000 60-mer probes with an estimated average resolution of 65 Kb. Probe locations are assigned according to position on the human reference genome as shown of UCSC genome browser - NCBI build 36/hg18, March 2006 (http://genome.ucsc.edu).

DNA labeling was performed according to the Agilent Genomic DNA Labeling Kit Plus using the Oligonucleotide Array-Based CGH for Genomic DNA Analysis 2.0v protocol (Agilent Technologies Italia SpA, Milano IT). 3.5 μgs of genomic DNA from patients with classical RTT and Z-RTT was mixed with Cy5-dNTP while 3.5 μgs of genomic DNA from a control sample with known CNVs was mixed with Cy3-dNTP, as previously reported.39 The array was disassembled and washed according to the manufacturer protocol with wash buffers supplied with the Agilent 105A kit. The slides were dried and scanned using an Agilent G2565BA DNA microarray scanner (Agilent Technologies).

Array-CGH image and data analysis

Image analysis was performed using the CGH Analytics software v. 5.0.14 using the default settings (Agilent Technologies). The software automatically first determines the fluorescence intensities of the spots for both fluorochromes performing background subtraction and data normalization, then compiles the data into a spreadsheet that links the fluorescent signal of every oligo on the array to the oligo name, its position on the array and its position in the genome. The linear order of the oligos is reconstituted in the ratio plots consistent with an ideogram. The ratio plot is arbitrarily assigned such that gains and losses in DNA copy number at a particular locus are observed as a deviation of the ratio plot from a modal value of 1.0.

Analysis of MeCP2 bound promoters within defined CNVs

Chromatin immunopreceipitation microarray (ChIP-chip) analysis of genome-wide promoters was performed in a previous study.40 Briefly, MeCP2 ChIP was performed on two replicate human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cultures differentiated by 48h treatment with phorbal 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and hybridized to a commercial genome wide promoter microarray (Nimblegen, Wisconsin, USA). In this 1.5 kb promoter array, tiled oligonucleotide probes extend 1.3 kb upstream and 0.2 kb downstream of the transcriptional start sites of 24,275 human transcripts. Statistical analysis of promoter ChIP-chip data indicated that 2600-4300 promoters were bound by MeCP2 with 1524 promoters common to two replicate hybridizations. Promoters were ranked according to MeCP2 binding “hits” based on ChIP-chip log2 values for the two arrays (MeCP2_B and MeCP2_C). In this way, 1 represents the strongest MeCP2 bound promoter out of 24,275 annotated genes. The data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession no. GSE9568).

Analyses of phenotypically discordant RTT pairs resulted in 29 CNVs that included 67 candidate genes which could potentially modify RTT phenotype. The MeCP2 promoter rankings were compared for the list of 67 candidate genes using all gene aliases. MeCP2 promoter levels could not be identified for 24 of the 67 CNV genes because these genes were not annotated on the NimbleGen promoter array.

Results

Overall, we indentified 29 CNVs, 28 of them corresponding to known polymorphic regions and one on 3q13.12 corresponding to an apparently private rearrangement duplicated in only one Z-RTT patient (#119) (Table 1 and 2). Among the 29 CNVs, we considered 14 of them as “unlikely modifiers” since they were apparently not associated with phenotypic severity (Table 2). These include regions containing olfactory receptors and class II HLA molecules that are not expected to directly correlate with the phenotypic variability related to classic/Z-RTT phenotype. The remaining 15 CNVs were considered as “likely modifiers” (Table 1). In three cases the copy number change was consistent with severity differences in at least two pairs of RTT patients (Table 1) (Fig. 1). Genes included in these potential modifier regions are listed and described in Table 3.

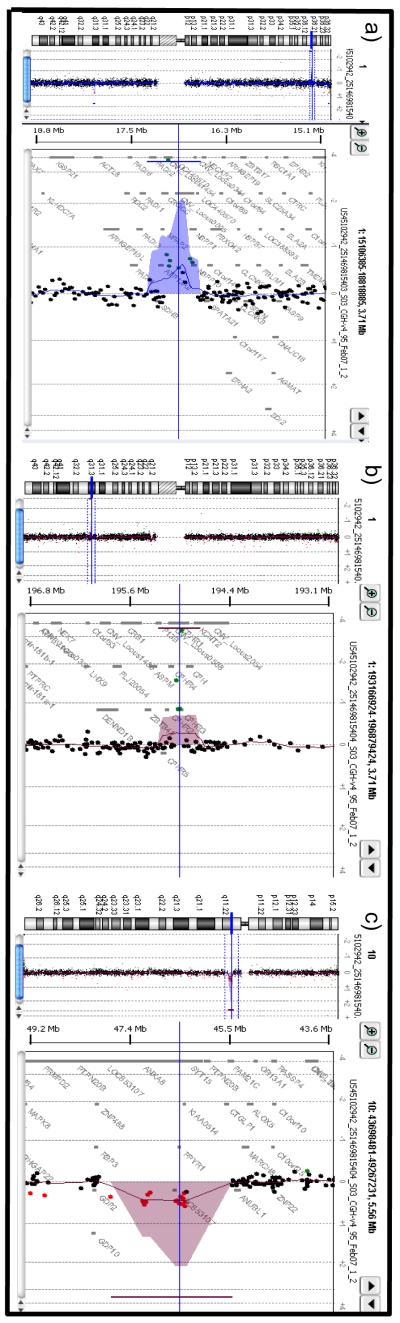

Figure 1.

Array-CGH ratio profiles. a) Array-CGH ratio profiles of CNV on 1p36.13 of #402 classic RTT patient. On the left, the chromosome 1 ideogram. On the right, the log 2 ratio of the chromosome 1 probes plotted as a function of chromosomal position. Copy number loss shifts the ratio to the left. b) Array-CGH ratio profiles of CNV on 1q31.3 of #368 Z-RTT patient. On the left, the chromosome 1 ideogram. On the right, the log 2 ratio of the chromosome 1 probes plotted as a function of chromosomal position. Copy number loss shifts the ratio to the left. c) Array-CGH ratio profiles of CNV on 10q11.22 of #139 Z-RTT patient. On the left, the chromosome 10 ideogram. On the right, the log 2 ratio of the chromosome 10 probes plotted as a function of chromosomal position. Copy number gain shifts the ratio to the right.

Table 3.

Genes included in potential modifier regions.

| Position | Gene | Description | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chr1: 16,890,300- 16,919,239 |

ESPNP | espin pseudo gene, non- coding RNA |

Unknown |

| Chr1: 16,954,395- 16,959,139 |

MSTP9 | macrophage stimulating, pseudogene 9, non-coding RNA |

Unknown |

| Chr1: 17,121,032- 17,172,061 |

CROCC | ciliary rootlet coiled-coil, rootletin |

Ciliary rootlet formation |

| Chr1: 195,055,484- 195,067,942 |

CFHR1 | complement factor H- related |

Complement regulation |

| Chr1: 195,010,553- 195,029,496 |

CFHR3 | complement factor H- related |

Complement regulation |

| Chr1: 223,741,157- 223,907,468 |

ENAH | enabled homolog (Drosophila) |

Involvement in a range of processes dependent on cytoskeleton remodelling and cell polarity such as axon guidance and lamellipodial and filopodial dynamics in migrating cells. |

| Chr2: 3,171,750- 3,360,605 |

TSSC1 | tumor suppressing subtransferable candidate 1 |

Possible involvement in tumor suppression |

| Chr2: 3,362,453- 3,462,349 |

TTC15 | tetratricopeptide repeat domain 15. |

Possible involvement in autophagy |

| Chr3: 110,109,340- 110,155,310 |

GUCA1C | guanylate cyclase activator 1C |

Ca(2+)-sensitive regulation of guanylyl cyclase |

| Chr3: 110,159,777- 110,319,658 |

MORC1 | MORC family CW-type zinc finger 1 |

Possible role in spermatogenesis |

| Chr3: 110,379,702- 110,386,794 |

C3orf66 | chromosome 3 open reading frame 66, non- coding RNA |

Unknown |

| Chr5: 848,722- 904,101 |

ZDHHC11 | zinc finger, DHHC-type containing 11 |

Probable palmitoyltransferase activity |

| Chr6: 167,970,520- 168,115,552 |

MLLT4 | myeloid/lymphoid or mixed-lineage leukemia |

Involvement in adhesion system, probably together with the E-cadherin-catenin system, which plays a role in the organization of homotypic, interneuronal and heterotypic cell- cell adherens junctions |

| Chr6: 168,136,351- 168,140,606 |

C6orf54 | chromosome 6 open reading frame 54 |

Unknown |

| Chr6: 168,161,402- 168,188,618 |

KIF25 | kinesin family member 25 | Possible involvement in microtubule- dependent molecular transport of organelles within cells and movement of chromosomes during cell division. |

| Chr6: 168,199,313- 168,222,688 |

FRMD1 | FERM domain containing 1 | Unknown |

| Chr7: 11,380,696- 11,838,349 |

THSD7A | thrombospondin, type I, domain containing 7A |

Interaction with alpha(V)beta(3) integrin and paxillin to inhibit endothelial cell migration and tube formation. |

| Chr8: 87,129,807- 87,150,967 |

PSKH2 | protein serine kinase H2 | CAMK Ser/Thr protein kinase |

| Chr8: 87,180,318- 87,234,433 |

ATP6VOD2 | ATPase, H+ transporting, lysosomal 38kDa, V0 subunit d2 |

Subunit of the integral membrane V0 complex of vacuolar ATPase that is responsible for acidifying a variety of intracellular compartments in eukaryotic cells, thus providing most of the energy required for transport processes in the vacuolar system. May play a role in coupling of proton transport and ATP hydrolysis. |

| Chr10: 46,413,552- 46,420,574 |

GPRIN2 | G protein regulated inducer of neurite outgrowth 2 |

Possible role in the control growth of neurites |

| Chr10: 46,503,540- 46,508,326 |

PPYR1 | pancreatic polypeptide receptor 1 |

It belongs to a family of receptors for neuropeptide Y involved in a diverse range of biological actions including stimulation of food intake, anxiolysis, modulation of circadian rhythm, pain transmission and control of pituitary hormone release. |

| Chr10: 105,717,460- 105,777,332 |

SLK | STE20-like kinase (yeast) | Possible mediation of apoptosis and actin stress fiber dissolution. |

| Chr10: 105,781,036- 105,835,628 |

COL17A1 | collagen, type XVII, alpha 1 |

It encodes the alpha chain of type XVII collagen that is a structural component of hemidesmosomes, multiprotein complexes at the dermal-epidermal basement membrane zone mediating adhesion of keratinocytes to the underlying membrane. |

| Chr22: 41,226,540- 41,238,510 |

SERHL | serine hydrolase-like | Possible role in normal peroxisome function and skeletal muscle growth in response to mechanical stimuli. |

| Chr22: 41,279,869- 41,300,332 |

SERHL2 | serine hydrolase-like 2 | Probable serine hydrolase. May be related to muscle hypertrophy. |

To determine if the CNVs found in phenotypically discordant RTT pairs contained possible MeCP2 target genes, we compared promoter rankings of MeCP2 binding using promoter-wide ChIP-chip analysis.40 The ranking from total number of genes from 1 to 24,134 is shown for two replicate MeCP2-ChIP microarrays (MeCP2 B and MeCP2 C promoter hits rank, Tables 1 and 2). Genes with promoters in the top 10% of MeCP2 promoter hits for at least one replicate are indicated in bold. Among CNVs classified as “likely modifiers”, ChIP-chip analysis identified potential MeCP2 target genes within the 1p36.13 (CROCC gene whose duplication was found in the Z-RTT # 896 and deletion in the classic form #402) and the 2p25.2 (TSSC1 gene whose deletion was found in the Z-RTT #896) regions. Among CNVs classified as “unlikely modifiers”, ChIP-chip analysis identified potential MeCP2 target genes on 14q11 (OR4Q3 and OR4Q1, deleted in a classic patient #138 and duplicated in another classic patient #421) and on 16p11.2 (NFATC2IP and SPNS1, duplicated in both a classic #897 and a Z-RTT patient #368).

Discussion

In order to test the hypothesis that genes contained within common CNVs may modulate the RTT phenotype, we analyzed by array-CGH two pairs of RTT sisters and four additional pairs of unrelated RTT girls matched by MECP2 mutation type showing discordant phenotype: classic and Z-RTT. Our study did not identify a single major common modifier gene/region, suggesting that genetic modifiers may be complex and variable between cases (Tables 1 and 2). In total we found 29 CNVs that were divided into two groups: “likely modifiers” and “unlikely modifiers” (Tables 1 and 2).

Among the first group, the rearrangement on 1p36.13 includes CROCC (ciliary rootlet coiled-coil) that represents an interesting potential modifier gene. This gene is duplicated in the Z-RTT patient # 896 and deleted in the classical patient # 402, suggesting that change in its expression may modulate RTT outcome. Moreover, according to ChIP-chip analysis, CROCC could be a potential MeCP2 target gene (Table 1). CROCC encodes for a major structural component (Rootletin) of the ciliary rootlet, a cytoskeletal-like structure in ciliated cells which originates from the basal body at the proximal end of a cilium and extends proximally toward the cell nucleus.41 In non-ciliated cells, a miniature ciliary rootlet is located at the centrosome and does not project a fibrous network into the cytoplasm.41 Rootletin is expressed in retina, brain, trachea and kidney.41 Cilia generate specialized structures that perform critical functions of several broad types: sensation, development, fluid movement, sperm motility, and cell signaling. Their functional significance in tissues is reflected in the severity and diversity of pathologies caused by defects in cilia. These include anosmia, retinitis pigmentosa and retinal degeneration, polycystic kidney disease, diabetes, neural tube defects and neural patterning defects, chronic sinusitus and bronchiectasis, obesity, heterotaxias, polydactyly, and infertility.42 Defects in cilia are therefore underlying causes of several diseases with pleiotropic symptoms.43 Several pleiotropic disorders (Bardet-Biedl syndrome, Alstrom syndrome, Meckel-Gruber syndrome and Joubert syndrome) caused by disruption of the function of cilia present mental retardation or other cognitive defects as part of their phenotypic spectrum.44 The presence of cilia in different types of neurons supports the notion that dysfunction in specific neuronal populations might explain, at least in part, such defects.42, 45 If MeCP2 acts as a positive regulator of CROCC, it can be hypothesized that higher protein levels due to the presence of three copies of the gene may counteract the MECP2 mutation, while lower protein level due to single gene copy may worsen the phenotype.

The CFHR gene family members (CFHR1 and CFHR3) located on 1q31.3 are duplicated in classic girls ( #185 and #402) and deleted in Z-RTT (#368), suggesting that the phenotype may benefit from the reduced expression of these proteins involved in complement regulation.46 The complement system is a tightly controlled component of the host innate immune defence. Imbalances in regulation of this system contribute to tissue injury and can result in autoimmune diseases. In particular, CFHR1 and CFHR3 was previously associated with hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) and age related macular degeneration (AMD).47-49 It is well known that the immune system participates in the development and functioning of the CNS and an immune etiology for RTT and autism has been recently hypothesized.50 Interestingly, complement proteins have been demonstrated to be fundamental for CNS synapse elimination.51 Morphological studies in postmortem brain samples from RTT individuals described a characteristic neuropathology which included decreased dendritic arborization, a reduction in dendritic spines, and increased packing density.52 It is therefore possible that the protein product of CFHR could be involved in the regulation of synaptic connections and that these genes could influence RTT severity.

The duplication on 10q11.22, present in two Z-RTT patients (#139 and #368), includes two interesting candidate modifier genes: GPRIN2 and PPYR1. GPRIN2 is highly expressed in the cerebellum and interacts with activated members of the Gi subfamily of G protein α subunits and acts together with GPRIN1 to regulate neurite outgrowth.53 PPYR1, also named as neuropeptide Y receptor or pancreatic polypeptide 1, is a key regulator of energy homeostasis and directly involved in the regulation of food intake. Previous studies have reinforced the potential influence of PPYR1 on body weight in humans.54 Moreover, it has been demonstrated that PPYR1 knockout mice display lower body weight and reduced white adipose tissue.55 Thus, a higher level of PPYR1 expression due to gene duplication may correlate with the higher body weight characterizing Z-RTT patients in respect to classic RTT.5 In contrast, a recent study demonstrated that 10q11.22 gain is associated with lower body mass index value in the Chinese population.56 However this CNV is much larger respect to the one reported here and includes two additional genes.56

The 3q13.12 duplication found in a Z-RTT patient (#119) encompasses about 280 Kb and does not contain interesting candidate RTT modifier genes. GUCA1C encodes for a granulate cyclise activating protein expressed in retina and MORC1 encodes for a testis-specific protein with a putative role in spermatogenesis. However it is known that CNVs can also induce altered expression of genes that lie near the boundaries of the CNV and that this effect can be as far as 2–7 Mb away from the breakpoints.57 Therefore we cannot totally exclude a role for this CNV in modulating RTT phenotype.

The 1q42.12 region, duplicated in one Z-RTT patient (#896), includes ENAH. This gene was identified as a mammalian homolog of Drosophila Ena and initially named Mena (Mammalian enabled).58 It localizes to cell-substrate adhesion sites and sites of dynamic actins assembly and disassembly. It is a member of the Ena/VASP family that also includes VASP and EVL in vertebrates. Work carried out in Drosophila, C. elegant and mice showed that these proteins participate in axonal outgrowth, dendrite morphology, synapse formation and also function downstream of attractive and repulsive axon guidance pathways.59-61 Previous evidence shows that knocking out the three murine genes encoding ENA/VASP proteins results in a blockade of axon fibre tract formation in the cortex in vivo, and that failure in neuritis initiation is the underlying cause of the axonal defects.62,63 ENAH therefore represents an interesting potential gene modifier in RTT. Further investigations are necessary in order to test whether the duplication of ENAH gene in Z-RTT #896 effectively corresponds with increased mRNA levels in brain and whether this mechanism is confined to one pair of discordant girls or is a common mechanism in Z-RTT possibly throughout SNP modulation.

The intersection of CNV and MeCP2 promoter binding analyses was useful in identifying potential modifier genes for further investigation. However, genes with MeCP2 bound promoters were not apparently enriched within the CNVs in the “likely” versus “unlikely” modifier categories. MeCP2 binding is found more frequently in non-promoter regions when analyzed by genomic tiling microarray to selected regions, so the analysis of promoters only in identifying potential MeCP2 target genes was a limitation of this study.40 Further studies to detect MeCP2 binding genome-wide in human neurons by Chip sequencing may reveal additional insights.

A second limitation of this study is that the number of patients is too low to perform a statistically significant analysis of CNVs in classic and Z-RTT and this is principally due to the difficulty in recruiting Z-RTT cases. Furthermore, mRNA expression analysis of genes within CNVs has not been performed because of a lack of sufficient blood RNA samples. However, an analysis of transcript levels in blood would not be conclusive because the genes within likely modifier CNVs exhibit tissue-specific expression in tissues other than blood cells. Our studies do suggest genes for further studies in animal models or in new cellular models such as neurons derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS).

Moreover this study indicates possible candidate genes to test for functional SNPs in array-CGH negative cases. In fact this study is focused on CNVs but SNPs could also play an important role in determining RTT phenotypic variability. By candidate gene approach, this has been already demonstrated for the p.Val66Met polymorphism in BDNF, even if with contrasting results.64,65 The recent feasibility of exome sequencing will allow to yield important results that will further improve the understanding of RTT phenotypic variability.

In conclusion, we present a novel approach for investigating genetic modifiers for RTT severity by identifying CNVs different between pairs with discordant phenotype: classic and Z-RTT. Further investigation using gene expression and/or statistical analysis in a larger number of patients will be necessary to confirm these data and to define targets for future therapeutic intervention.

Acknowledgments

We would first like to thank Rett patients and their families. This work was supported by “Cell Lines and DNA Bank of Rett syndrome, X mental retardation and other genetic diseases” (Medical Genetics-Siena) - Telethon Genetic Biobank Network (Project No. GTB07001C to AR)” and NIH R01HD041462 to J.M.L.

References

- 1.Trevathan E, Moser HW. Diagnostic criteria for Rett syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1988;23:425–428. doi: 10.1002/ana.410230432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neul J, Kaufmann W, Glaze D, Christodoulou J, Clarke A, Bahi-Buisson N, et al. Rett Syndrome: Revised Diagnostic Criteria and Nomenclature. Annals of Neurology. 2010 doi: 10.1002/ana.22124. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mencarelli MA, Spanhol-Rosseto A, Artuso R, Rondinella D, De Filippis R, Bahi-Buisson N, et al. Novel FOXG1 mutations associated with the congenital variant of Rett syndrome. J Med Genet. 2010;47:49–53. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.067884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zappella M. The Rett girls with preserved speech. Brain Dev. 1992;14:98–101. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(12)80094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Renieri A, Mari F, Mencarelli MA, Scala E, Ariani F, Longo I, et al. Diagnostic criteria for the Zappella variant of Rett syndrome (the preserved speech variant) Brain Dev. 2009;31:208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weaving L, Christodoulou J, Williamson S, Friend K, McKenzie O, Archer H, et al. Mutations of CDKL5 cause a severe neurodevelopmental disorder with infantile spasms and mental retardation. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:1079–1093. doi: 10.1086/426462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scala E, Ariani F, Mari F, Caselli R, Pescucci C, Longo I, et al. CDKL5/STK9 is mutated in Rett syndrome variant with infantile spasms. J Med Genet. 2005;42(2):103–107. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.026237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ariani F, Hayek G, Rondinella D, Artuso R, Mencarelli MA, Spanhol-Rosseto A, et al. FOXG1 is responsible for the congenital variant of Rett syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zappella M, Meloni I, Longo I, Hayek G, Renieri A. Preserved Speech Variants of the Rett Syndrome: Molecular and Clinical analysis. Am J Med Genet. 2001;104:14–22. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hardwick SA, Reuter K, Williamson SL, Vasudevan V, Donald J, Slater K, et al. Delineation of large deletions of the MECP2 gene in Rett syndrome patients, including a familial case with a male proband. Eur J Hum Genet. 2007;15:1218–1229. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amir RE, Van den Veyver IB, Schultz R, Malicki DM, Tran CQ, Dahle EJ, et al. Influence of mutation type and X chromosome inactivation on Rett syndrome phenotypes. Ann Neurol. 2000;47:670–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scala E, Longo I, Ottimo F, Speciale C, Sampieri K, Katzaki E, et al. MECP2 deletions and genotype-phenotype correlation in Rett syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143:2775–2784. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans JC, Archer HL, Whatley SD, Clarke A. Germline mosaicism for a MECP2 mutation in a man with two Rett daughters. Clin Genet. 2006;70:336–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mari F, Azimonti S, Bertani I, Bolognese F, Colombo E, Caselli R, et al. CDKL5 belongs to the same molecular pathway of MeCP2 and it is responsible for the early-onset seizure variant of Rett syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:1935–1946. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Archer H, Evans J, Leonard H, Colvin L, Ravine D, Christodoulou J, et al. Correlation between clinical severity in patients with Rett syndrome with a p.R168X or p.T158M MECP2 mutation, and the direction and degree of skewing of X-chromosome inactivation. J Med Genet. 2007;44:148–152. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.045260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zoghbi HY, Percy AK, Schultz RJ, Fill C. Patterns of X chromosome inactivation in the Rett syndrome. Brain Dev. 1990;12:131–135. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(12)80194-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharp A, Robinson D, Jacobs P. Age- and tissue-specific variation of X chromosome inactivation ratios in normal women. Hum Genet. 2000;107:343–349. doi: 10.1007/s004390000382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anvret M, Wahlstrom J. Rett syndrome: random X chromosome inactivation. Clin Genet. 1994;45:274–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1994.tb04157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LaSalle JM, Goldstine J, Balmer D, Greco CM. Quantitative localization of heterogeneous methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MeCP2) expression phenotypes in normal and Rett syndrome brain by laser scanning cytometry. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1729–1740. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.17.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shahbazian MD, Sun Y, Zoghbi HY. Balanced X chromosome inactivation patterns in the Rett syndrome brain. Am J Med Genet. 2002;111:164–168. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibson JH, Williamson SL, Arbuckle S, Christodoulou J. X chromosome inactivation patterns in brain in Rett syndrome: implications for the disease phenotype. Brain Dev. 2005;27:266–270. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nag N, Mellott TJ, Berger-Sweeney JE. Effects of postnatal dietary choline supplementation on motor regional brain volume and growth factor expression in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Brain Res. 2008;1237:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lonetti G, Angelucci A, Morando L, Boggio EM, Giustetto M, Pizzorusso T. Early environmental enrichment moderates the behavioral and synaptic phenotype of MeCP2 null mice. Biol Psychiatry. 67:657–665. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aitman TJ, Dong R, Vyse TJ, Norsworthy PJ, Johnson MD, Smith J, et al. Copy number polymorphism in Fcgr3 predisposes to glomerulonephritis in rats and humans. Nature. 2006;439:851–855. doi: 10.1038/nature04489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mamtani M, Rovin B, Brey R, Camargo JF, Kulkarni H, Herrera M, et al. CCL3L1 gene-containing segmental duplications and polymorphisms in CCR5 affect risk of systemic lupus erythaematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1076–1083. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.078048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hollox EJ. Copy number variation of beta-defensins and relevance to disease. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2008;123:148–155. doi: 10.1159/000184702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fellermann K, Stange DE, Schaeffeler E, Schmalzl H, Wehkamp J, Bevins CL, et al. A chromosome 8 gene-cluster polymorphism with low human beta-defensin 2 gene copy number predisposes to Crohn disease of the colon. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:439–448. doi: 10.1086/505915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singleton AB, Farrer M, Johnson J, Singleton A, Hague S, Kachergus J, et al. alpha-Synuclein locus triplication causes Parkinson’s disease. Science. 2003;302:841. doi: 10.1126/science.1090278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ibanez P, Bonnet AM, Debarges B, Lohmann E, Tison F, Pollak P, et al. Causal relation between alpha-synuclein gene duplication and familial Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 2004;364:1169–1171. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stefansson H, Rujescu D, Cichon S, Pietilainen OP, Ingason A, Steinberg S, et al. Large recurrent microdeletions associated with schizophrenia. Nature. 2008;455:232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature07229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diskin SJ, Hou C, Glessner JT, Attiyeh EF, Laudenslager M, Bosse K, et al. Copy number variation at 1q21.1 associated with neuroblastoma. Nature. 2009;459:987–991. doi: 10.1038/nature08035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frank B, Hemminki K, Meindl A, Wappenschmidt B, Sutter C, Kiechle M, et al. BRIP1 (BACH1) variants and familial breast cancer risk: a case-control study. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:83. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karypidis AH, Olsson M, Andersson SO, Rane A, Ekstrom L. Deletion polymorphism of the UGT2B17 gene is associated with increased risk for prostate cancer and correlated to gene expression in the prostate. Pharmacogenomics J. 2008;8:147–151. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iafrate AJ, Feuk L, Rivera MN, Listewnik ML, Donahoe PK, Qi Y, et al. Detection of large-scale variation in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2004;36:949–951. doi: 10.1038/ng1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Redon R, Ishikawa S, Fitch KR, Feuk L, Perry GH, Andrews TD, et al. Global variation in copy number in the human genome. Nature. 2006;444:444–454. doi: 10.1038/nature05329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sampieri K, Meloni I, Scala E, Ariani F, Caselli R, Pescucci C, et al. Italian Rett database and biobank. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:329–335. doi: 10.1002/humu.20453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pegoraro E, Schimke RN, Arahata K, Hayashi Y, Stern H, Marks H, et al. Detection of new paternal dystrophin gene mutations in isolated cases of dystrophinopathy in females. Am J Hum Genet. 1994;54:989–1003. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hagberg B, Hanefeld F, Percy A, Skjeldal O. An update on clinically applicable diagnostic criteria in Rett syndrome. Comments to Rett Syndrome Clinical Criteria Consensus Panel Satellite to European Paediatric Neurology Society Meeting, Baden Baden, Germany, 11 September 2001. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2002;6:293–297. doi: 10.1053/ejpn.2002.0612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sampieri K, Amenduni M, Papa FT, Katzaki E, Mencarelli MA, Marozza A, et al. Array comparative genomic hybridization in retinoma and retinoblastoma tissues. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:465–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.01070.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yasui DH, Peddada S, Bieda MC, Vallero RO, Hogart A, Nagarajan RP, et al. Integrated epigenomic analyses of neuronal MeCP2 reveal a role for long-range interaction with active genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19416–19421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707442104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang J, Liu X, Yue G, Adamian M, Bulgakov O, Li T. Rootletin, a novel coiled-coil protein, is a structural component of the ciliary rootlet. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:431–440. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200207153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee JH, Gleeson JG. The role of primary cilia in neuronal function. Neurobiol Dis. 38:167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McClintock TS, Glasser CE, Bose SC, Bergman DA. Tissue expression patterns identify mouse cilia genes. Physiol Genomics. 2008;32:198–206. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00128.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Badano JL, Mitsuma N, Beales PL, Katsanis N. The ciliopathies: an emerging class of human genetic disorders. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2006;7:125–148. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Han YG, Alvarez-Buylla A. Role of primary cilia in brain development and cancer. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 20:58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Male DA, Ormsby RJ, Ranganathan S, Giannakis E, Gordon DL. Complement factor H: sequence analysis of 221 kb of human genomic DNA containing the entire fH, fHR-1 and fHR-3 genes. Mol Immunol. 2000;37:41–52. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(00)00024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hughes AE, Orr N, Esfandiary H, Diaz-Torres M, Goodship T, Chakravarthy U. A common CFH haplotype, with deletion of CFHR1 and CFHR3, is associated with lower risk of age-related macular degeneration. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1173–1177. doi: 10.1038/ng1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Raychaudhuri S, Ripke S, Li M, Neale BM, Fagerness J, Reynolds R, et al. Associations of CFHR1-CFHR3 deletion and a CFH SNP to age-related macular degeneration are not independent. Nat Genet. 42:553–555. doi: 10.1038/ng0710-553. author reply 555-556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jozsi M, Licht C, Strobel S, Zipfel SL, Richter H, Heinen S, et al. Factor H autoantibodies in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome correlate with CFHR1/CFHR3 deficiency. Blood. 2008;111:1512–1514. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-109876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Derecki NC, Privman E, Kipnis J. Rett syndrome and other autism spectrum disorders--brain diseases of immune malfunction? Mol Psychiatry. 15:355–363. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stevens B, Allen NJ, Vazquez LE, Howell GR, Christopherson KS, Nouri N, et al. The classical complement cascade mediates CNS synapse elimination. Cell. 2007;131:1164–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Armstrong DD. Neuropathology of Rett syndrome. J Child Neurol. 2005;20:747–753. doi: 10.1177/08830738050200090901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iida N, Kozasa T. Identification and biochemical analysis of GRIN1 and GRIN2. Methods Enzymol. 2004;390:475–483. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)90029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kamiji MM, Inui A. Neuropeptide y receptor selective ligands in the treatment of obesity. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:664–684. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sainsbury A, Schwarzer C, Couzens M, Fetissov S, Furtinger S, Jenkins A, et al. Important role of hypothalamic Y2 receptors in body weight regulation revealed in conditional knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8938–8943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132043299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sha BY, Yang TL, Zhao LJ, Chen XD, Guo Y, Chen Y, et al. Genome-wide association study suggested copy number variation may be associated with body mass index in the Chinese population. J Hum Genet. 2009;54:199–202. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2009.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Merla G, Howald C, Henrichsen CN, Lyle R, Wyss C, Zabot MT, et al. Submicroscopic deletion in patients with Williams-Beuren syndrome influences expression levels of the nonhemizygous flanking genes. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:332–341. doi: 10.1086/506371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gertler FB, Niebuhr K, Reinhard M, Wehland J, Soriano P. Mena, a relative of VASP and Drosophila Enabled, is implicated in the control of microfilament dynamics. Cell. 1996;87:227–239. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81341-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lanier LM, Gates MA, Witke W, Menzies AS, Wehman AM, Macklis JD, et al. Mena is required for neurulation and commissure formation. Neuron. 1999;22:313–325. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lin YL, Lei YT, Hong CJ, Hsueh YP. Syndecan-2 induces filopodia and dendritic spine formation via the neurofibromin-PKA-Ena/VASP pathway. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:829–841. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200608121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li W, Li Y, Gao FB. Abelson, enabled, and p120 catenin exert distinct effects on dendritic morphogenesis in Drosophila. Dev Dyn. 2005;234:512–522. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kwiatkowski AV, Rubinson DA, Dent EW, van Veen J. Edward, Leslie JD, Zhang J, et al. Ena/VASP Is Required for neuritogenesis in the developing cortex. Neuron. 2007;56:441–455. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dent EW, Kwiatkowski AV, Mebane LM, Philippar U, Barzik M, Rubinson DA, et al. Filopodia are required for cortical neurite initiation. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1347–1359. doi: 10.1038/ncb1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nectoux J, Bahi-Buisson N, Guellec I, Coste J, De Roux N, Rosas H, et al. The p.Val66Met polymorphism in the BDNF gene protects against early seizures in Rett syndrome. Neurology. 2008;70:2145–2151. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000304086.75913.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zeev BB, Bebbington A, Ho G, Leonard H, de Klerk N, Gak E, et al. The common BDNF polymorphism may be a modifier of disease severity in Rett syndrome. Neurology. 2009;72:1242–1247. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000345664.72220.6a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]