Abstract

Background and Objectives

Nod2 polymorphisms increase the risk for developing Crohn’s disease, characterized by chronic intestinal inflammation. Bacterial peptidoglycan products chronically stimulate Nod2 in the intestine. Recent studies found that chronic Nod2 stimulation in human macrophages downregulates pro-inflammatory cytokines upon Nod2 or Toll-like receptor (TLR) restimulation. Therefore, an emerging hypothesis is that Nod2-mediated cytokine downregulation is required for intestinal homeostasis, but the mechanisms mediating this downregulation are incompletely understood.

Methods

Utilizing primary human macrophages, we examined secretory mediators as a mechanism of Nod2-mediated tolerance by inhibiting their function and assessing tolerance reversal through cytokine secretion. Signaling pathways contributing to secretory mediator induction and Nod2-mediated tolerance were identified through pathway inhibition.

Results

We find that chronic Nod2 stimulation not only cross-tolerizes to TLRs, but also to the IL-1 receptor (IL-1R). Moreover, chronic IL-1β stimulation downregulates Nod2 responses. Accordingly, IL-1β blockade partially reverses Nod2-mediated tolerance. We find that an additional essential mechanism for Nod2-mediated tolerance is the early secretion of the anti-inflammatory mediators IL-10, TGF-β and IL-1Ra. Importantly, the mTOR pathway, involved in cell growth, differentiation and activation, significantly contributes to Nod2-induced anti- as opposed to pro-inflammatory cytokines and to Nod2-mediated tolerance.

Conclusions

Inflammatory responses through the IL-1R are downregulated upon chronic Nod2 stimulation, secretory mediators are a critical mechanism for Nod2-mediated cytokine downregulation, and the mTOR pathway is crucial for Nod2-mediated tolerance. These results further contribute to our understanding of the mechanisms through which Nod2, a protein critical to intestinal homeostasis, downregulates cytokine responses.

Keywords: human, monocytes/macrophages, cytokines

Introduction

Of the genes associated to Crohn's disease (CD) thus far, polymorphisms in nucleotide oligomerization domain 2 (Nod2), a bacterial-sensing protein, confer the greatest risk of developing CD1,2. Acute Nod2 stimulation with muramyl dipeptide (MDP), the minimal bacterial peptidoglycan component specifically activating Nod23, activates NF-κB and MAPK and induces pro-inflammatory cytokines4-6. How Nod2 signaling contributes to intestinal homeostasis is controversial and incompletely understood. Current hypotheses include Nod2 contributions to: 1) microbial defenses, and 2) downregulation of inflammation7,8.

Intestinal immune cells are chronically exposed to bacteria and their products, including Nod2 ligands. Importantly, unlike peripheral macrophages, intestinal macrophages do not secrete cytokines upon stimulation of Nod2, PRR or cytokine receptors, indicating that they are already tolerant to these stimuli9. To understand the mechanisms that lead to this tolerance, we utilized primary peripheral monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM), as monocytes are instructed to become tolerant upon entering the intestine. We previously showed that mimicking intestinal conditions by chronic, as opposed to acute, Nod2 stimulation downregulates pro-inflammatory cytokines upon restimulation with MDP (‘self-tolerance’) or with Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and 4 ligands (‘cross-tolerance’) in MDM10. MDP-pretreated cells from CD-associated Leu1007insC Nod2 homozygote individuals do not exhibit cross-tolerance10. Subsequent studies demonstrated Nod2-mediated tolerance in additional human and murine cells6,11, although not all murine studies observed TLR and Nod2 cross-tolerization12. These differences in species response emphasize the importance of studying Nod2 in human cells10,12. The emerging hypothesis that chronic Nod2 stimulation is important for maintaining intestinal immune homeostasis is supported by findings that MDP administration in vivo protects mice from experimental colitis by down-regulating TLR responses6,9,10. It is thus essential to address the mechanisms leading to Nod2-mediated downregulation of inflammatory responses; these mechanisms have not been well studied. Mechanisms downregulating PRR responses include PRR downregulation and upregulation of either intracellular or secreted inhibitory molecules. We previously showed that Nod2-mediated tolerance is not a result of downregulated TLR2, TLR4 and Nod2 receptors10. However, we found that IRAK-1 kinase activity is downregulated and the intracellular IRAK-1 inhibitory molecule IRAK-M is upregulated in some individuals, and that these pathways partially contribute to Nod2-mediated tolerance10. IRF-4 also contributes to Nod2-mediated tolerance in myeloid cells6. As each of these mechanisms is only partially responsible for tolerance induction, we hypothesized that secretory mediators constitute another important mechanism for this process.

The aim of this study was to further define the extent and mechanisms mediating Nod2-induced tolerance in primary human MDM. We establish that cross-tolerance following chronic Nod2 stimulation extends not only to PRRs, but to the IL-1R. Additionally, we identify that mechanisms contributing to Nod2 tolerance include secreted mediators; specifically, the pro-inflammatory cytokine, IL-1β, as well as the anti-inflammatory mediators IL-10, TGF-β and IL-1Ra. Furthermore, we find that mTOR, a pathway crucial for cell growth and lymphocyte differentiation and activation, differentially regulates Nod2–induced pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators. Importantly, mTOR is essential for the induction of Nod2-mediated tolerance. Our results elucidate mechanisms critical for Nod2-mediated immune regulation under conditions observed in the intestinal environment.

Materials and Methods

Patient recruitment and genotyping

Informed consent was obtained per protocol approved by the Yale University institutional review board. We performed genotyping by TaqMan SNP genotyping (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) or Sequenom platform (Sequenom Inc., San Diego, CA). Unless otherwise stated, we utilized cells from healthy individuals not carrying the Leu1007insC or Glu908Arg Nod2 mutations. Our 103 healthy controls included only one Arg702Trp heterozygote who showed a normal tolerance pattern.

Primary MDM cell culture

Monocytes were purified from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells by negative or positive CD14 selection (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA), purity tested and cultured as described previously10.

MDM stimulation

For tolerance studies, cultured MDM were pretreated with MDP (Bachem, King of Prussia, PA), IL-1β (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), IL-10, TGF-β or IL-1Ra (R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN) for 48h at indicated doses prior to extensive wash and 24h retreatment with MDP, lipid A (Peptides International, Louisville, KY) or IL-1β. To inhibit tolerance, anti-IL-1β, anti-IL-10, anti-TGF-β or anti-IL-1Ra blocking antibodies (R&D Systems) or their combinations, appropriate isotype controls, rapamycin (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA), or DMSO control were added 1h prior to pretreatments. To ensure that antibodies or inhibitors used during pretreatments did not affect cytokine induction during retreatment, separate cells were cultured with corresponding antibodies or inhibitors without pretreatment stimulation, thoroughly washed and retreated. We observed no significant differences in cytokine levels between these samples compared to those without antibody/inhibitor pretreatment. Moreover, in experiments utilizing antibodies or inhibitors, cytokine levels were normalized to cytokines secreted by cells cultured with antibodies or inhibitors alone in the pretreatment phase. Supernatants were assayed for IL-1β (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL), TNF-α, IL-8 or IL-6 (BD Biosciences) or for IL-1Ra, IL-10 and IL-12p40 (R&D Systems) by ELISA.

Statistical analysis

Significance with treatment was assessed using a paired one-tailed Student t test. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Nod2 and IL-1R exhibit dose-dependent self- and cross-tolerance

Intestinal immune cells are chronically exposed to bacterial products and cytokines; it is important to understand how these interactions contribute to intestinal homeostasis. Relatively few reports address cross-talk between cytokines and PRR13,14, and no studies describe downregulation of cytokine receptor responses following Nod2 stimulation. We previously established that acute Nod2 signaling activates IRAK-1 and that chronic Nod2 treatment downregulates IRAK-1 activation10. In addition to PRR signaling, IRAK-1 participates in IL-1R signaling15. We therefore questioned if chronic Nod2 stimulation of MDM downregulates pro-inflammatory cytokines upon IL-1R restimulation.

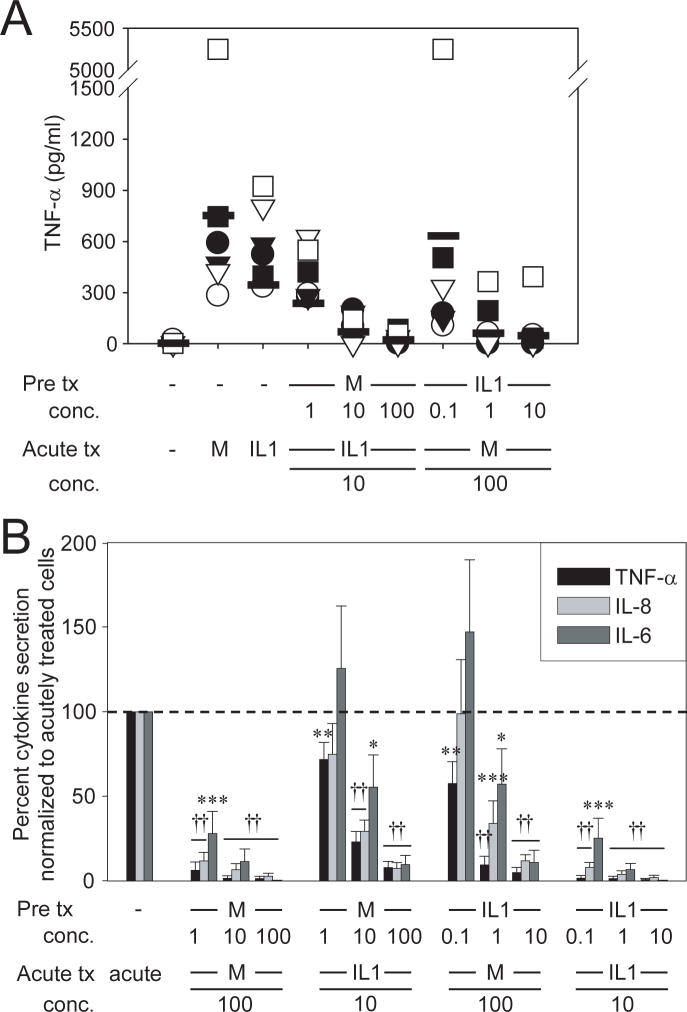

To define the mechanisms mediating induction of tolerance, we conducted our studies in peripheral MDMs from wild-type Nod2 healthy controls under conditions simulating the stimuli encountered as they enter the intestine. We find that pretreatment of MDM with the Nod2 ligand MDP downregulates the secretion of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α in a dose-responsive manner following IL-1β restimulation (Fig 1A). To our knowledge no reports show that IL-1R stimulation alone downregulates PRR responses. However, given shared Nod2 and IL-1R pathways, we questioned if IL-1R also downregulates inflammatory responses through Nod2. We find that IL-1β pretreatment of MDM decreases TNF-α secretion upon MDP restimulation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig 1A). In addition to TNF-α, we examined IL-8 and IL-6 secretion since previous reports observed differential cytokine regulation during endotoxin tolerance16. While MDM pretreatment with the lowest MDP (1μg/ml) or IL-1β (0.1ng/ml) doses showed significant self-tolerance, cross-tolerance to the other ligand at these low doses was observed only for TNF-α secretion (Fig 1B). However, at higher ligand concentrations, IL-1R and Nod2 cross-tolerized to each other for all cytokines assessed (Fig 1B). Therefore, we use 100μg/ml MDP for pretreatment in subsequent studies. Importantly, MDMs from Nod2 CD-associated mutant Leu1007insC homozygote or compound heterozygote patients with CD, which show defective acute MDP responses,4 demonstrated a defect in Nod2 to IL-1R cross-tolerance, whereas IL-1β–induced self-tolerance is normal in these cells, indicating that the defects are present specifically in Nod2-mediated tolerance (Supplementary Fig 1A). Leu1007insC heterozygotes and CD patients with wild-type Nod2 show unimpaired Nod2-induced tolerance (Supplementary Figure 1B and C). Significantly, in MDM from WT Nod2 individuals we observe cross-tolerization between Nod2 and IL-18R, which also signals through IRAK-115 (Supplementary Fig 2). However, Nod2-mediated cross-tolerance to cytokine receptors is not universal, as we do not observe cross-tolerization between Nod2 and TNF-α or IFN-γ-induced pathways (Supplementary Fig 2), cytokine receptors which do not signal through IRAK-1. Therefore, Nod2-mediated tolerance extends not only to TLRs, but also to selective cytokine receptors, and chronic IL-1R and IL-18R stimulation downregulates subsequent Nod2 responses.

Figure 1. Chronic MDP and IL-1β stimulation result in cross-tolerance in a dose-dependent manner.

(A) Human MDM (n=6) were stimulated with 1, 10 or 100μg/ml MDP or 0.1, 1 or 10ng/ml IL-1β for 48h, washed, and restimulated for an additional 24h with 100μg/ml MDP or 10ng/ml IL-1β. Supernatants were assayed for TNF-α. (B) Summarized data for multiple cytokines are represented as the percent TNF-α, IL-8 or IL-6 secretion by MDP- or IL-1β– pretreated cells upon restimulation normalized to that of non-pretreated cells (represented by the dotted line at 100%) +SEM (n=6). Tx, treatment; acute, 24h MDP or IL-1β stimulation; M, MDP. Significance compared to non-MDP-pretreated cells is shown. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001; ††, p<1×10-5. Lines over adjacent bars indicate identical p values for these bars. MDM from an additional n=15 assessed at the highest stimuli doses demonstrated cross-tolerance between Nod2 and IL-1R.

IL-1β autocrine loop blockade reduces Nod2-mediated tolerance in some individuals

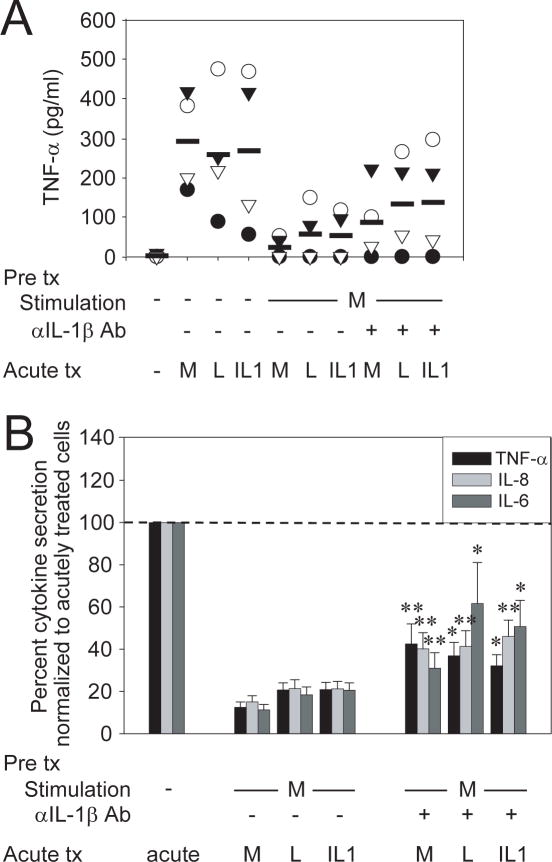

As Nod2 stimulation produces IL-1β, and chronic IL-1R stimulation downregulates Nod2-induced cytokines, we questioned if autocrine IL-1β secretion is a mechanism contributing to Nod2-mediated tolerance. To address this, we inhibited IL-1β-induced signaling during MDP pretreatment of MDM through IL-1β neutralizing antibodies, and then assessed Nod2-mediated tolerance upon Nod2, TLR4 and IL-1R restimulation. We chose these receptors as representative Nod, TLR and cytokine receptors whose signaling is downregulated by Nod2-prestimulation. IL-1β signaling blockade partially reversed Nod2-mediated tolerance, although the degree of tolerance reversal varied between the individuals (Fig 2A) and cytokines tested (Fig 2B). Specifically, the difference in normalized TNF-α, IL-8 and IL-6 levels between Nod2-tolerized cells after IL-1β blockade relative to no IL-1β blockade averaged 20-30% for MDP retreatment (self-tolerance) and 20-50% for lipid A or 14-35% for IL-1β retreatment (cross-tolerance) depending on the cytokine examined (Fig 2B). Taken together, we demonstrate that autocrine IL-1β signaling contributes to Nod2-mediated tolerance.

Figure 2. An IL-1β autocrine loop partially contributes to Nod2-mediated tolerance.

(A) MDM were stimulated with 100μg/ml MDP in the presence or absence of 1μg/ml neutralizing anti-IL-1β antibody for 48h, washed, and restimulated for an additional 24h with 100μg/ml MDP, 0.1μg/ml lipid A or 10ng/ml IL-1β. Supernatants were assayed for TNF-α. The data are representative of 4 of 16 individuals. To ensure that residual anti-IL-1β antibodies used during pretreatment did not carry over and affect cytokine induction during retreatment, cells were prestimulated with anti-IL-1β alone, thoroughly washed and retreated. We observed no significant differences in cytokine levels between these samples compared to those without neutralizing antibody pretreatment. Moreover, cytokine levels in anti-IL-1β–treated samples were normalized to those secreted by cells prestimulated with anti-IL-1β alone. (B) The data for multiple cytokines in the 16 individuals are represented as the percent TNF-α, IL-8 or IL-6 secretion by MDP or MDP + anti-IL-1β pretreated cells upon restimulation normalized to acutely stimulated cells, or to anti-IL-1β–pretreated, washed and acutely stimulated cells, respectively (represented by the dotted line at 100%) +SEM. Tx, treatment; acute, 24h MDP stimulation, lipid A or IL-1β; M, MDP; L, lipid A. Significance of MDP + anti-IL-1β pretreated cells compared to MDP-pretreated cells for each condition is shown. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01.

Chronic Nod2 treatment downregulates IL-10 and IL-1Ra secretion upon Nod2, TLR4 or IL-1R restimulation

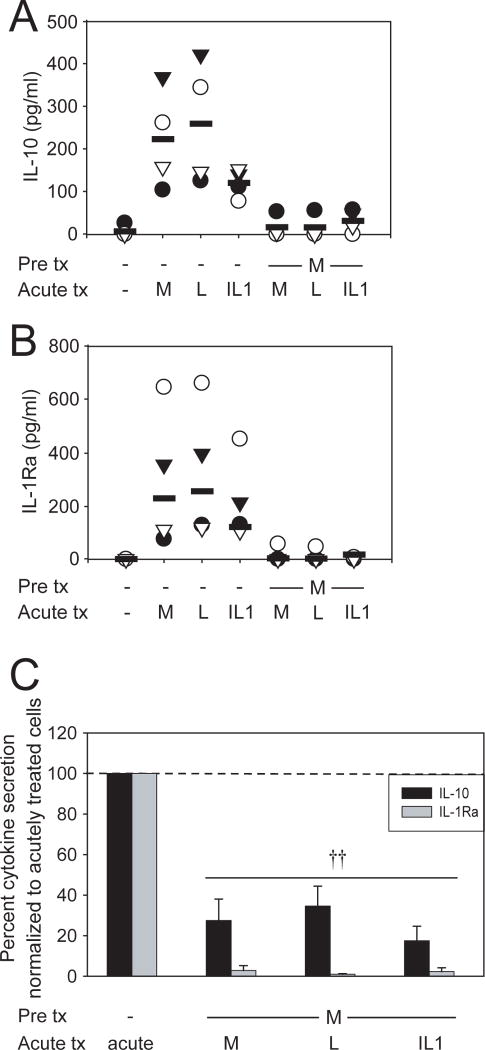

As Nod2-induced IL-1β secretion contributes to Nod2-mediated tolerance, we questioned if MDP stimulation induces additional secreted mediators that mechanistically contribute to the tolerance. The anti-inflammatory mediators IL-10 and TGF-β downregulate pro-inflammatory cytokines in macrophages and PBMCs17. IL-1Ra has been studied mostly in the context of IL-1β inhibition; however, it may have broader anti-inflammatory effects given the importance of IL-1β autocrine loops in amplifying inflammatory responses10,13. Therefore we examined whether chronically MDP-treated MDM maintain secretion of these anti-inflammatory mediators upon Nod2, TLR4 or IL-1R restimulation. We find that acute Nod2 stimulation induces IL-10 (Fig 3A) and IL-1Ra (Fig 3B). We did not detect induction of active TGF-β protein by MDP, lipid A or IL-1β stimulation in serum-containing or in serum-free media. Similar to pro-inflammatory cytokines, upon chronic Nod2 stimulation, IL-10 (Fig 3A&C) and IL-1Ra (Fig 3B&C) levels are significantly decreased following MDP, lipid A or IL-1β restimulation. Therefore, Nod2-mediated tolerance is not the result of sustained anti-inflammatory mediators that downregulate pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Figure 3. Prolonged pretreatment with MDP downregulates induction of IL-10 and IL-1Ra upon subsequent MDM stimulation.

MDM were stimulated with 100μg/ml MDP for 48h, washed, and restimulated for an additional 24h with 100μg/ml MDP, 0.1μg/ml lipid A or 10ng/ml IL-1β. Supernatants were assayed for (A) IL-10 or (B) IL-1Ra. The data are representative of 4 of 8 individuals (IL-10) or 4 of 4 individuals (IL-1Ra). (C) Summarized data for all the individuals assessed are represented as the percent IL-10 or IL-1Ra secretion by MDP pretreated cells upon restimulation normalized to acutely stimulated cells (represented by the dotted line at 100%) +SEM. Tx, treatment; acute, 24h stimulation with MDP, lipid A or IL-1β; M, MDP; L, lipid A. Significance compared to non-MDP-pretreated cells is shown. ††, p<1×10-5.

Blockade of early IL-10, TGF-β and IL-1Ra reverses Nod2-mediated tolerance

While IL-10 and IL-1Ra are downregulated upon chronic MDP treatment, they are secreted upon acute Nod2 stimulation and could therefore induce Nod2-mediated tolerance through an autocrine loop. Therefore, we assessed if blocking these anti-inflammatory mediators during MDP prestimulation reverses Nod2-mediated tolerance upon Nod2, TLR4 or IL-1R restimulation. We first confirmed effective antibody blockade by ensuring that each respective antibody reverses the IL-10-, TGF-β- and IL-1Ra-mediated pro-inflammatory cytokine suppression during MDM stimulation (data not shown). Upon blockade of early anti-inflammatory mediators individually during initial Nod2 stimulation, we find partial tolerance reversal in cells restimulated with MDP, lipid A or IL-1β (Supplementary Fig 3). This tolerance reversal was specific as it was not observed with neutralizing anti-IFN-γ or anti-TNF-α antibodies (Supplementary Fig 4), consistent with the inability of these cytokines to induce tolerance (Supplementary Fig 2). The magnitude of reversal in cytokine downregulation varied among individuals and across cytokines (Supplementary Fig 3). IL-10, TGF-β and IL-1Ra blockade upon acute Nod2 stimulation increased pro-inflammatory cytokines in some individuals (Supplementary Fig 3), indicating that acute anti-inflammatory cytokine induction contributes to suppressing pro-inflammatory responses. The pro-inflammatory cytokine increase during acute stimulation upon inhibitory mediator blockade did not, however, correlate to the degree of tolerance reversal observed in the individuals tested (r2<0.5). Therefore, acute induction of each of the anti-inflammatory mediators IL-10, TGF-β and IL-1Ra partially contributes to Nod2-mediated tolerance.

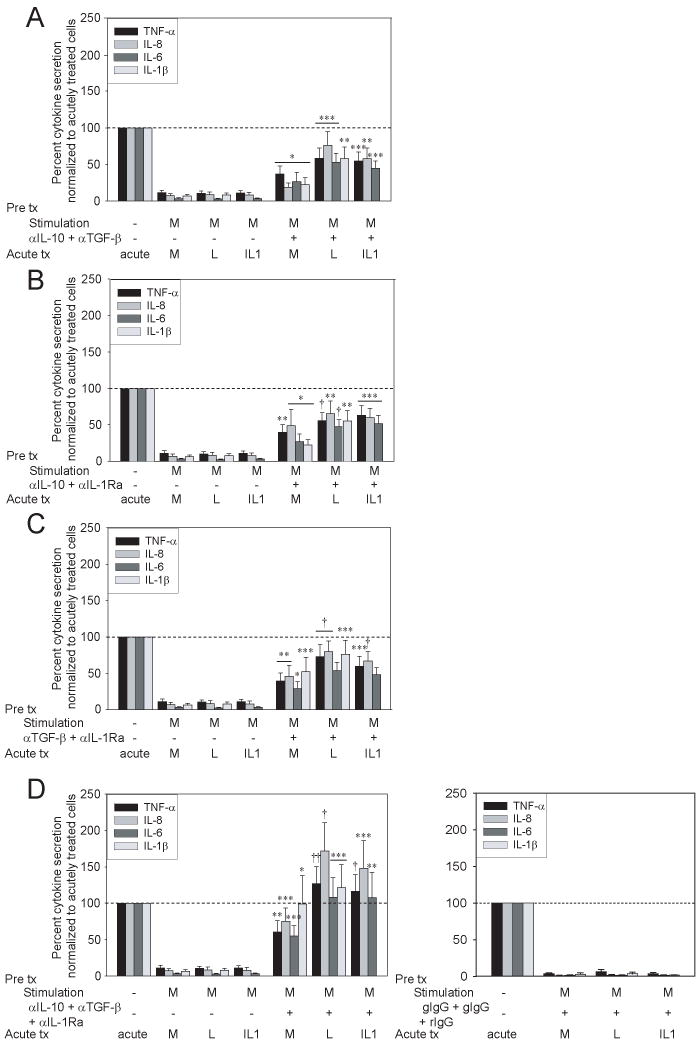

Combined blockade of early IL-10, TGF-β and IL-1Ra signaling significantly enhances Nod2-mediated tolerance reversal

Individual IL-10, TGF-β and IL-1Ra blockade partially reversed Nod2-mediated tolerance. To determine if these anti-inflammatory mediators cooperate in tolerance induction, we investigated the effects of combined blockade of these secretory mediators. Using MDM from the same individuals assessed in Supplementary Fig 3, we find that combined blockade of two anti-inflammatory mediators reversed Nod2-mediated downregulation of TNF-α, IL-8, IL-6 and IL-1β (Fig 4A-C) to a greater degree than blockade of each anti-inflammatory mediator alone. Moreover, relative to blockade of any two mediators, combined blockade of all three anti-inflammatory mediators led to yet more pronounced or complete tolerance reversal; tolerance reversal was not observed with the combined isotype controls (Fig 4D). In summary, early secretion of Nod2-induced IL-10, TGF-β and IL-1Ra cooperate as a critical mechanism in Nod2-mediated tolerance.

Figure 4. Combined blockade of secreted anti-inflammatory mediators reverses Nod2-mediated tolerance.

MDM from the same individuals (n=16) as in Supplementary Fig 3 were stimulated with 100μg/ml MDP in the presence or absence of (A) combined anti-IL-10 (5μg/ml; isotype goat IgG) and anti-TGF-β (25μg/ml; isotype goat IgG) antibodies, (B) combined anti-IL-10 and anti-IL-1Ra (5μg/ml; isotype rabbit IgG) antibodies, (C) combined anti-TGF-β and anti-IL-1Ra antibodies or (D) combined all three antibodies (left) for 48h, washed, and restimulated for an additional 24h with 100μg/ml MDP, 0.1μg/ml lipid A or 10ng/ml IL-1β. The data are represented as the percent TNF-α, IL-8, IL-6 or IL-1β secretion by MDP or MDP + antibody pretreated cells (n=16) upon restimulation normalized to acutely stimulated cells, or to antibody-pretreated, washed and acutely stimulated cells, respectively (represented by the dotted line at 100%) +SEM. Appropriate isotype controls (D, right) are shown. Tx, treatment; acute, 24h MDP, lipid A or IL-1β stimulation; M, MDP; L, lipid A. Significance of treatment in the presence of MDP+blocking antibody-pretreated cells compared to MDP-pretreated cells is shown. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001; †, p<1×10-4; ††, p<1×10-5. Lines over adjacent bars indicate identical p values for these bars.

Treatment of MDM with IL-10, TGF-β and IL-1Ra induces Nod2-mediated tolerance

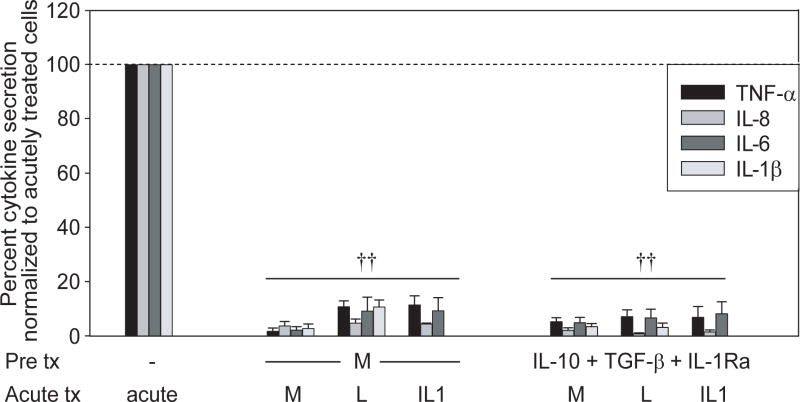

To ensure that the Nod2-mediated tolerance reversal by anti-inflammatory mediator blockade during Nod2 prestimulation is not due to the increased pro-inflammatory environment, but rather to the active tolerance induction by these mediators, we asked if IL-10, TGF-β and IL-1Ra pretreatment of MDM are sufficient to downregulate pro-inflammatory cytokine induction following Nod2, TLR4 or IL-1R restimulation. We selected IL-10 and IL-1Ra concentrations within range of levels induced upon Nod2 stimulation of MDM. We find that MDM pretreatment with IL-10, TGF-β and IL-1Ra in combination for 48h significantly decreases TNF-α, IL-8 or IL-6 upon restimulation with MDP, lipid A or IL-1β (Fig 5). Therefore, combined IL-10, TGF-β and IL-1Ra induced by Nod2 stimulation are both necessary and sufficient for Nod2-mediated tolerance induction.

Figure 5. Prolonged pretreatment with anti-inflammatory mediators downregulates pro-inflammatory cytokines following Nod2, TLR4 or IL-1R restimulation.

MDM were stimulated with 100μg/ml MDP or combined 10ng/ml IL-10, 2ng/ml TGF-β and 10ng/ml IL-1Ra for 48h, washed, and restimulated for an additional 24h with 100μg/ml MDP, 0.1μg/ml lipid A or 10ng/ml IL-1β. The data are represented as the percent TNF-α, IL-8, IL-6 or IL-1β secretion normalized to acutely stimulated cells (represented by the dotted line at 100%) +SEM (n=8). Tx, treatment; acute, 24h stimulation with MDP, lipid A or IL-1β; M, MDP; L, lipid A. Significance of MDP or anti-inflammatory-mediator- pretreated cells compared to acute stimulation for each condition is shown. ††, p<1×10-5. Lines over adjacent bars indicate identical p value for these bars.

The mTOR pathway contributes to differential regulation of anti- and pro-inflammatory cytokines by MDP

To define signaling pathways required for Nod2-mediated tolerance, we next investigated the pathways utilized by Nod2 to preferentially induce anti-inflammatory mediators. First, we examined MAPK pathways, as TLR4 signaling activates the MAPK p38 to induce IL-10 but downregulate IL-12 in murine antigen-presenting cells18. However, we find that p38, ERK, and JNK pathway inhibition during Nod2- and TLR4- stimulation of MDM downregulates both anti- and pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion (Supplementary Fig 5).

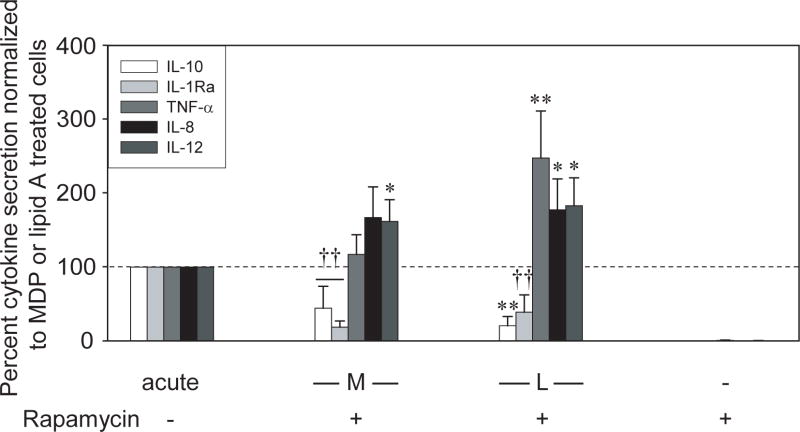

The mTOR pathway contributes to critical cell functions, including lymphocyte differentiation and cell growth19. Significantly, mTOR can play a differential role in pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine regulation such that TLR4-mediated mTOR signaling induces IL-10 and downregulates IL-12 in human monocytes20. However, the mTOR role upon Nod2 activation has not been examined. Rapamycin is a bacterial component that specifically inhibits mTOR activation19,21. We find that rapamycin treatment during MDP stimulation of MDM downregulates anti-, but upregulates pro-inflammatory cytokine induction (Fig 6). Therefore, Nod2-induced mTOR activation differentially regulates anti- and pro-inflammatory cytokines in human MDM.

Figure 6. mTOR signaling differentially regulates Nod2-induced pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators.

MDM from control individuals (n=8) were preincubated with 1μM rapamycin and stimulated with 100μg/ml MDP or 0.1μg/ml lipid A for 24h. The data are represented as the IL-10, IL-1Ra, TNF-α, IL-8, or IL-12p40 secretion upon rapamycin treatment normalized to that of MDP- or lipid A-treated cells (represented by the dotted line at 100%) +SEM. Stimulation of MDM with rapamycin alone did not induce pro- or anti-inflammatory cytokines. Acute, 24h MDP or lipid A stimulation without inhibitors; M, MDP and L, lipid A. Significance compared to acutely stimulated cells without rapamycin treatment is shown. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ††, p<1×10-5. Lines over adjacent bars indicate identical p value for these bars.

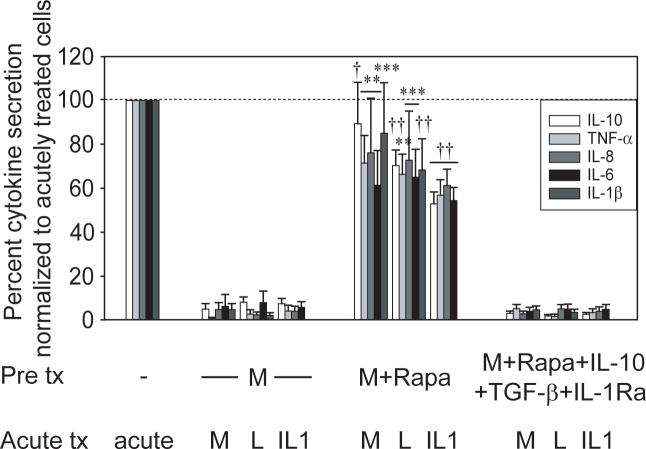

mTOR inhibition reverses Nod2-mediated tolerance

In light of selective inhibitory mediator secretion upon Nod2-induced mTOR activation, we questioned if acute Nod2-induced mTOR signaling is required for Nod2-mediated tolerance. To address this, we inhibited mTOR with rapamycin during MDP pretreatment of MDM and then assessed Nod2-mediated tolerance. Rapamycin inhibition during Nod2 prestimulation significantly reversed Nod2-mediated cytokine downregulation upon restimulation of Nod2, TLR4 and IL-1R (Fig 7). To assess if restoring these anti-inflammatory mediators during pretreatment was sufficient to restore tolerance, we complemented the cells with IL-10, TGF-β and IL-1Ra during the rapamycin + MDP pretreatment period. We find that these mediators reconstituted Nod2-mediated cytokine downregulation (Fig 7). As MDM from Nod2 Leu1007insC homozygote or compound heterozygote individuals show defective Nod2-mediated cross-tolerance (Supplementary Fig 1), we asked if MDM from these individuals have impaired mTOR activation. We find that Nod2 stimulation by MDP leads to phosphorylation of the mTOR substrate p70 S6 kinase20 (Supplementary Fig 6) and of the upstream mTOR activator Akt (data not shown). This activation is defective in MDM from Leu1007insC homozygote and compound heterozygote individuals and the defect persists over time. Importantly, lipid A activation of the mTOR pathway is intact in MDM from these Nod2 polymorphism carriers (Supplementary Fig 6). Taken together, the mTOR pathway is a critical mechanism mediating the decreased inflammatory responses observed upon chronic Nod2 stimulation and mTOR activation is defective in cells from Leu1007insC Nod2 homozygote or compound heterozygote individuals.

Figure 7. mTOR signaling contributes to Nod2-mediated cytokine downregulation following Nod2, TLR4 or IL-1R restimulation.

MDM were pretreated with 100μg/ml MDP in the presence or absence of 1μM rapamycin or rapamycin with combined 10ng/ml IL-10, 2ng/ml TGF-β and 10ng/ml IL-1Ra for 48h, then washed, and restimulated for an additional 24h with 100μg/ml MDP, 0.1μg/ml lipid A or 10ng/ml IL-1β. The data are represented as the percent IL-10, TNF-α, IL-8, IL-6 or IL-1β secretion by MDP (normalized to acutely stimulated cells) or MDP+rapamycin+anti-inflammatory mediator-pretreated cells (normalized to rapamycin-pretreated, washed and acutely stimulated cells) upon restimulation (acutely stimulated cells are represented by the dotted line at 100%) +SEM (n=8; confirmed at 2μM rapamycin dose in an additional n=4). Tx, treatment; acute 24h MDP, lipid A or IL-1β stimulation; M, MDP; L, lipid A; Rapa, rapamycin. Cytokine levels secreted by cells pretreated with rapamycin, washed and acutely stimulated were not significantly different from those of acutely stimulated cells, indicating there was no residual rapamycin effect after the incubation period and washes. Significance of MDP and rapamycin-pretreated cells compared to MDP-pretreated cells for each condition is shown. **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001; †, p<1×10-4; ††, p<1×10-5. Lines over adjacent bars indicate identical p value for these bars.

Discussion

The intestinal immune system must balance inflammatory and tolerant microbial responses to maintain homeostasis. Nod2 mutations confer the strongest genetic risk identified to date towards developing CD1,2. We previously identified a role for Nod2 in tolerance under conditions simulating the intestinal environment; chronic Nod2 stimulation in MDM downregulates pro-inflammatory responses upon Nod2, TLR2 and TLR4 restimulation10. This cytokine downregulation occurs at a transcriptional level (data not shown). We further show that Nod2-mediated tolerance extends not only to TLRs but also to the IL-1R. Importantly, in addition to Nod2 cross-tolerizing to IL-1R, IL-1R prestimulation also downregulates Nod2 responses. Consistent with this, IL-1β autocrine secretion contributes to Nod2-mediated tolerance. In addition to IL-1β, we find that the anti-inflammatory mediators IL-10, TGF-β and IL-1Ra are necessary and sufficient for Nod2-mediated tolerance. Moreover, we establish for the first time that Nod2 signaling activates the mTOR pathway; mTOR activation by Nod2 upregulates anti-inflammatory mediators and simultaneously downregulates pro-inflammatory cytokines. Consistently, we find that mTOR inhibition significantly reverses Nod2-mediated tolerance. Taken together, our results identify critical molecules and signaling pathways required for Nod2-mediated tolerance (Supplementary Fig 7), a process that likely has crucial implications on intestinal immune homeostasis.

We find that Nod2-mediated tolerance is defective in Leu1007insC Nod2 homozygote and compound heterozygote macrophages, but is observed in macrophages from Leu1007insC Nod2 heterozygotes and WT Nod2 CD patients (Supplementary Fig 1). The much greater functional consequence on tolerance in Nod2 homozygotes compared to heterozygotes is consistent with the significantly greater risk of developing CD in Nod2 Leu1007insC homozygotes compared to heterozygotes7. Morever, these results demonstrate that Nod2-mediated tolerance defects are specific to carriers of the Nod2 CD-susceptible polymorphisms, rather than to all CD patients.

In contrast to cross-talk between PRRs, PRR and cytokine receptor cross-tolerization has not been well studied. Rare reports examining IL-1R and TLR4 cross-tolerization show that although TLR4 activation downregulates subsequent IL-1R responses14, IL-1R alone could not downregulate TLR4 responses13. We now report for the first time that Nod2 cross-tolerizes to IL-1R (Fig 1). Furthermore, chronic stimulation through IL-1R alone is sufficient to downregulate subsequent Nod2-induced pro-inflammatory cytokines. Given the importance of IL-1β in intestinal immunity, IL-1β and Nod2 cross-tolerance may have particular importance for mechanisms of intestinal immune homeostasis. IL-18R, which shares signaling pathways with IL-1R, also mediates cross-tolerance with Nod2. In contrast, the cytokines TNF-α and IFN-γ, signaling through pathways distinct from IL-1β and IL-18, do not contribute to Nod2-mediated tolerance (Supplementary Fig 2), thereby demonstrating specificity in PRR and cytokine receptor cross-tolerization. Although categorized as a pro-inflammatory mediator, the ability of IL-1β to downregulate Nod2 signaling demonstrates additional roles for this cytokine. Similar complexity has been observed with Type I interferons and TLR signaling22.

We find that Nod2-induced IL-10, TGF-β and IL-1Ra autocrine secretion, are each mechanisms contributing to Nod2-induced tolerance. Although chronically stimulated cells do not maintain selective expression of these mediators (Fig 3), the early secretion of the mediators is critical for Nod2-mediated tolerance (Fig 4). Selective upregulation of anti-inflammatory mediators as a TLR4-induced tolerance mechanism has been controversial, such that their expression is maintained in some systems23, but downregulated in others24. In our studies, blockade of early secretion of individual anti-inflammatory mediators contributed to tolerance reversal, but tolerance reversal was significantly increased with combined block of these mediators (Fig 4), indicating redundancy in the anti-inflammatory mediator contribution to Nod2-induced tolerance. In contrast, PBMC studies show that IL-10 and TGF-β suffice for endotoxin tolerance induction25. Additionally, IL-10 contributes to tolerance specifically for MyD88-dependent, but not certain MyD88-independent pathways16. We now show IL-10 contributions to tolerance also through the MyD88-independent Nod2 pathway. The importance of IL-10 and TGF-β in intestinal homeostasis is highlighted by studies showing colitis development in mice deficient in these mediators and by human intestinal explant studies in which their depletion induces IFN-γ and tissue damage22. Additionally, a recent report shows that CD-relevant Leu1007insC Nod2 suppresses IL-10 production8, further implicating the role of IL-10 regulation in intestinal homeostasis. The effects of IL-1Ra on tolerance mechanisms have not been extensively studied. With respect to Nod2, a single murine study shows that MDP induces IL-1Ra in vivo26. We now show for the first time that IL-10, TGF-β and IL-1Ra all significantly contribute to Nod2-mediated tolerance.

We now find that Nod2 activates the mTOR pathway in MDM; this activation differentially regulates pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators (Fig 6) and is required during MDP pretreatment to induce Nod2-mediated tolerance (Fig 7). The mTOR pathway has generally been associated with T-cell mediated immunoactivation. Therefore, the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin is utilized to downregulate inflammatory responses through mechanisms such as Treg induction during organ transplantation19, although it breaks T-cell-mediated tolerance in other systems21. Consequently, mTOR inhibition has complex outcomes. Therefore, one must consider that using rapamycin to downregulate T cell responses for therapeutic purposes might adversely affect immunoregulation by reversing PRR-mediated pro-inflammatory downregulation in the intestine.

Nod2 is critical in regulating intestinal immune homeostasis. This is evidenced by Nod2 loss-of-function mutations conferring a high CD risk, increased susceptibility of Nod2-/- mice to experimental colitis27, and chronic Nod2 stimulation preventing colitis in vivo6. It is thus essential to understand Nod2 functions under chronic stimulation; conditions simulating those of the intestinal environment. Tolerance development to bacterial antigens is likely an ongoing process as peripheral macrophages entering the intestine are instructed to become tolerant. The differences in mechanisms and outcomes of Nod2 signaling and endotoxin tolerance across cell lines and primary murine and human cells6,10-13, highlight the importance of examining Nod2 functions in human MDM. Other PRRs and signaling molecules have also been implicated in maintaining the tolerant milieu of the intestine28,29. While these molecules contribute to tolerance and share pathways with Nod2, Nod2 mutations are associated with the greatest genetic risk for developing CD identified to date, thereby implicating a non-redundant role for Nod2 in intestinal immune homeostasis. We identify cross-talk between Nod2 and IL-1R, secretory mediators as a mechanism for Nod2-mediated tolerance, and the importance of mTOR in regulating this tolerance, thereby providing insight into Nod2 contribution to intestinal immune homeostasis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the blood donors; and Fred S. Gorelick and Cathryn Nagler for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America (CA, MH), R01DK077905, DK-P30-34989, and U19-AI082713 (CA)

Abbreviations

- CD

Crohn’s disease

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

- Nod

nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain

- PRR

pattern-recognition receptor

- MDP

muramyl dipeptide

- MDM

monocyte-derived macrophages

- IL-1R

IL-1 receptor

- WT

wild type

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinases

Footnotes

Author contribution: MH and CA contributed to study design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, obtaining funds and study supervision.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hugot JP, Chamaillard M, Zouali H, Lesage S, Cezard JP, Belaiche J, Almer S, Tysk C, O’Morain CA, Gassull M, Binder V, Finkel Y, Cortot A, Modigliani R, Laurent-Puig P, Gower-Rousseau C, Macry J, Colombel JF, Sahbatou M, Thomas G. Association of NOD2 leucine-rich repeat variants with susceptibility to Crohn’s disease. Nature. 2001;411:599–603. doi: 10.1038/35079107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogura Y, Bonen DK, Inohara N, Nicolae DL, Chen FF, Ramos R, Britton H, Moran T, Karaliuskas R, Duerr RH, Achkar JP, Brant SR, Bayless TM, Kirschner BS, Hanauer SB, Nunez G, Cho JH. A frameshift mutation in NOD2 associated with susceptibility to Crohn’s disease. Nature. 2001;411:603–6. doi: 10.1038/35079114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Girardin SE, Boneca IG, Viala J, Chamaillard M, Labigne A, Thomas G, Philpott DJ, Sansonetti PJ. Nod2 is a general sensor of peptidoglycan through muramyl dipeptide (MDP) detection. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8869–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200651200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li J, Moran T, Swanson E, Julian C, Harris J, Bonen DK, Hedl M, Nicolae DL, Abraham C, Cho JH. Regulation of IL-8 and IL-1beta expression in Crohn’s disease associated NOD2/CARD15 mutations. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1715–25. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Netea MG, Ferwerda G, de Jong DJ, Jansen T, Jacobs L, Kramer M, Naber TH, Drenth JP, Girardin SE, Kullberg BJ, Adema GJ, Van der Meer JW. Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-2 modulates specific TLR pathways for the induction of cytokine release. J Immunol. 2005;174:6518–23. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watanabe T, Asano N, Murray PJ, Ozato K, Tailor P, Fuss IJ, Kitani A, Strober W. Muramyl dipeptide activation of nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 2 protects mice from experimental colitis. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:545–59. doi: 10.1172/JCI33145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abraham C, Cho JH. Functional consequences of NOD2 (CARD15) mutations. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:641–50. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000225332.83861.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noguchi E, Homma Y, Kang X, Netea MG, Ma X. A Crohn’s disease-associated NOD2 mutation suppresses transcription of human IL10 by inhibiting activity of the nuclear ribonucleoprotein hnRNP-A1. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:471–9. doi: 10.1038/ni.1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smythies LE, Sellers M, Clements RH, Mosteller-Barnum M, Meng G, Benjamin WH, Orenstein JM, Smith PD. Human intestinal macrophages display profound inflammatory anergy despite avid phagocytic and bacteriocidal activity. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:66–75. doi: 10.1172/JCI19229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hedl M, Li J, Cho JH, Abraham C. Chronic stimulation of Nod2 mediates tolerance to bacterial products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19440–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706097104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kullberg BJ, Ferwerda G, de Jong DJ, Drenth JP, Joosten LA, Van der Meer JW, Netea MG. Crohn’s disease patients homozygous for the 3020insC NOD2 mutation have a defective NOD2/TLR4 cross-tolerance to intestinal stimuli. Immunology. 2008;123:600–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02735.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim YG, Park JH, Shaw MH, Franchi L, Inohara N, Nunez G. The cytosolic sensors Nod1 and Nod2 are critical for bacterial recognition and host defense after exposure to Toll-like receptor ligands. Immunity. 2008;28:246–57. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vogel SN, Kaufman EN, Tate MD, Neta R. Recombinant interleukin-1 alpha and recombinant tumor necrosis factor alpha synergize in vivo to induce early endotoxin tolerance and associated hematopoietic changes. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2650–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.10.2650-2657.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Granowitz EV, Porat R, Mier JW, Orencole SF, Kaplanski G, Lynch EA, Ye K, Vannier E, Wolff SM, Dinarello CA. Intravenous endotoxin suppresses the cytokine response of peripheral blood mononuclear cells of healthy humans. J Immunol. 1993;151:1637–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arend WP, Palmer G, Gabay C. IL-1, IL-18, and IL-33 families of cytokines. Immunol Rev. 2008;223:20–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang J, Kunkel SL, Chang CH. Negative regulation of MyD88-dependent signaling by IL-10 in dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905815106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bogdan C, Paik J, Vodovotz Y, Nathan C. Contrasting mechanisms for suppression of macrophage cytokine release by transforming growth factor-beta and interleukin-10. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:23301–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salmon RA, Guo X, Teh HS, Schrader JW. The p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases can have opposing roles in the antigen-dependent or endotoxin-stimulated production of IL-12 and IFN-gamma. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:3218–27. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200111)31:11<3218::aid-immu3218>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roncarolo MG, Battaglia M. Regulatory T-cell immunotherapy for tolerance to self antigens and alloantigens in humans. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:585–98. doi: 10.1038/nri2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weichhart T, Costantino G, Poglitsch M, Rosner M, Zeyda M, Stuhlmeier KM, Kolbe T, Stulnig TM, Horl WH, Hengstschlager M, Muller M, Saemann MD. The TSC-mTOR signaling pathway regulates the innate inflammatory response. Immunity. 2008;29:565–77. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valle A, Jofra T, Stabilini A, Atkinson M, Roncarolo MG, Battaglia M. Rapamycin prevents and breaks the anti-CD3-induced tolerance in NOD mice. Diabetes. 2009;58:875–81. doi: 10.2337/db08-1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jarry A, Bossard C, Bou-Hanna C, Masson D, Espaze E, Denis MG, Laboisse CL. Mucosal IL-10 and TGF-beta play crucial roles in preventing LPS-driven, IFN-gamma-mediated epithelial damage in human colon explants. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1132–42. doi: 10.1172/JCI32140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Learn CA, Boger MS, Li L, McCall CE. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway selectively controls sIL-1RA not interleukin-1beta production in the septic leukocytes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20234–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100316200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dobrovolskaia MA, Medvedev AE, Thomas KE, Cuesta N, Toshchakov V, Ren T, Cody MJ, Michalek SM, Rice NR, Vogel SN. Induction of in vitro reprogramming by Toll-like receptor (TLR)2 and TLR4 agonists in murine macrophages: effects of TLR “homotolerance” versus “heterotolerance” on NF-kappa B signaling pathway components. J Immunol. 2003;170:508–19. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.1.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Randow F, Syrbe U, Meisel C, Krausch D, Zuckermann H, Platzer C, Volk HD. Mechanism of endotoxin desensitization: involvement of interleukin 10 and transforming growth factor beta. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1887–92. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.5.1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenzweig HL, Martin TM, Planck SR, Galster K, Jann MM, Davey MP, Kobayashi K, Flavell RA, Rosenbaum JT. Activation of NOD2 in vivo induces IL-1beta production in the eye via caspase-1 but results in ocular inflammation independently of IL-1 signaling. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84:529–36. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0108015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han X, Uchida K, Jurickova I, Koch D, Willson T, Samson C, Bonkowski E, Trauernicht A, Kim MO, Tomer G, Dubinsky M, Plevy S, Kugathsan S, Trapnell BC, Denson LA. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor autoantibodies in murine ileitis and progressive ileal Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1261–71. e1–3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S, Medzhitov R. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell. 2004;118:229–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vijay-Kumar M, Sanders CJ, Taylor RT, Kumar A, Aitken JD, Sitaraman SV, Neish AS, Uematsu S, Akira S, Williams IR, Gewirtz AT. Deletion of TLR5 results in spontaneous colitis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3909–21. doi: 10.1172/JCI33084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.