Abstract

We review the current status of the role and function of the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in the etiology of autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and the interaction of nuclear and mitochondrial genes. High lactate levels reported in about one in five children with ASD may indicate involvement of the mitochondria in energy metabolism and brain development. Mitochondrial disturbances include depletion, decreased quantity or mutations of mtDNA producing defects in biochemical reactions within the mitochondria. A subset of individuals with ASD manifests copy number variation or small DNA deletions/duplications, but fewer than 20 percent are diagnosed with a single gene condition such as fragile X syndrome. The remaining individuals with ASD have chromosomal abnormalities (e.g., 15q11-q13 duplications), other genetic or multigenic causes or epigenetic defects. Next generation DNA sequencing techniques will enable better characterization of genetic and molecular anomalies in ASD, including defects in the mitochondrial genome particularly in younger children.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorders (ASD), mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations and depletion, oxidative stress, nuclear genes, lactate/pyruvate ratios, genetic causation.

Leo Kanner described autism in 1943 in 11 children manifesting withdrawal from human contact as early as age 1 year postulating origins in prenatal life [1]. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV-Text Revised (DSM-IV-TR) described autism as a complex neurobehavioral disorder characterized by deficiencies in social interaction, impaired communication skills and repetitive stereotypic behavior with onset prior to 3 years of age [2]. Several conditions including full-syndrome autism (Autistic Disorder), Asperger Syndrome and Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS) are now grouped as Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) also known as Pervasive Developmental Disorders (PDDs) [2-4].

Symptoms of ASD usually begin in early childhood with evidence of delayed development before age 3 years. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends autism screening for early identification and intervention by at least age 12 months and again at 24 months. Rating scales helpful in establishing the diagnosis are Autism Diagnostic Interview- Revised (ADI-R) and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) in combination with clinical presentation [5, 6].

GENETIC CONTRIBUTIONS TO AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDERS

The etiology of ASD is complex and encompasses the roles of genes, the environment (epigenetics) and the mitochondria. Mitochondria are cellular organelles that function to control energy production necessary for brain development and activity. Researchers are increasingly identifying mitochondrial abnormalities in young children with ASD since the most severe cases present early with features of ASD. Better awareness and more accurate and detailed genetic and biochemical testing are now available for the younger patient presenting with developmental delay or behavioral problems.

Epidemiologic and family studies suggest that genetic risk factors are present. Monogenic causes are identifiable in less than 20 percent of subjects with ASD. The remaining subjects have other genetic or multigenic causes and/or epigenetic influences which are environmental factors altering gene expression without changing the DNA sequence [7-10]. Epigenetic factors in ASD have been reviewed by Grafodatskaya et al. [11]. The recurrence risk for ASD varies by gender for the second child to be affected (4% if the first child affected is female and 7% if a male). The recurrence rate increases to 25-30% if the second child is also diagnosed with ASD. Studies have shown that among identical twins, if one child has ASD, then the other has a 60 to 95% chance of being affected.

Fragile X syndrome and tuberous sclerosis are the most common single gene conditions associated with ASD. The commonest chromosomal abnormality in non-syndromal autism is duplication of the 15q11-q13 region, accounting for 5% of patients with autism. Large microdeletions in chromosome 16p11.2 and 22q regions account for another 1% of cases [12]. The rapid rise in the incidence of ASD in the past 30 years, apart from improved identification, points to environmental factors acting on essentially unchanged genetic predispositions involving nuclear and mitochondrial DNA since de novo changes in genes are unlikely to occur so quickly. Specific genetic and cytogenetic conditions associated with ASD are summarized in a recent review [13].

The role and importance of genetic testing for individuals with ASD is well recognized [14] with various studies showing yields of 6% to 40% with newer testing methods [15, 16]. Early studies by Miles and Hillman [15] tested 94 children clinically diagnosed with ASD and found that 6 of 94 (6%) had identifiable genetic disorders. Herman et al. [17] later found genetic causes in 7 of 71 (10%) subjects with ASD. Schaefer and Lutz [16] used a three- tier clinical genetic approach to identify causes in 32 clinically diagnosed children with ASD, and reported positive genetic findings in 13 subjects (40%). These included 5% with a high resolution chromosomal abnormality, 5% with fragile X syndrome, 5% with Rett syndrome (MECP2 gene defects in females), 3% with PTEN gene mutations in those with a head circumference > 2.5 SD, approximately 10% with other genetic syndromes (e.g., tuberous sclerosis) and 10% with small deletions or duplications identified using chromosomal microarrays.

High resolution chromosome analysis detects 3 to 5 megabase-sized abnormalities; however, new technology using DNA or chromosomal microarrays can identify abnormalities 100 times smaller. Therefore, microdeletions and duplications may now be identified with microarrays in individuals with ASD who previously had normal cytogenetic testing. Children with ASD show a higher prevalence of microdeletions and duplications, particularly involving chromosome regions 1q24.2, 3p26.2, 4q34.2, 6q24.3 and 7q35 including those with non-syndromal ASD [18]. Therefore, if cytogenetic analysis is negative in clinically diagnosed ASD, testing for microdeletions and duplications with newer techniques is warranted.

Shen and coworkers [19] studied genetic testing results from a cohort of 933 patients with ASD including G-banded karyotypes, fragile X testing and chromosomal microarrays. They reported abnormal karyotypes in 19 of 852 patients (2.2.%), abnormal fragile X testing in 4 of 861 patients (0.5%) and microarray identified deletions or duplications in 154 of 848 patients (18.2%). Fifty-nine of 154 subjects (38.3%) were associated with known genomic disorder variants with possible significance to ASD. With the exception of recurrent deletions or duplications of chromosome 16p11.2 [20] and chromosome 15q13.2q13.3 [21], most copy number changes were unique.

Wang et al. [22] reported the results from a genome-wide association study of 3,101 subjects representing 780 families with affected children and a second cohort of 1,204 affected subjects along with 6,491 controls. All of their subjects were of European ancestry. They found a strong association with six nucleotide polymorphisms between cadherin 10 (CDH10) and cadherin 9 (CDH9) genes. The latter two genes encode neuronal cell-adhesion molecules. These findings were replicated in two independent cohorts and demonstrate an association with susceptibility to ASD.

Sebat et al. [23] studied 165 individuals with autism grouped into 118 simplex families without a family history of autism and 47 multiplex families with multiple affected siblings and compared them with control groups without autism. They reported that 10.2% (12 of 118) of simplex families showed copy number variants (CNVs), 2.6% (2 of 77) with CNVs in individuals with autism from multiplex families and 1% (2 of 196) with CNVs among normally developing children. The majority of CNVs were of the deletion type. Thus, CNVs were significantly more common in the sporadic form of autism than in those with a family history due to single gene mutations not detectable by DNA deletion or duplication analysis.

As a result of research into nucleotide sequences, microdeletions and duplications in children with ASD can now be identified including syntaxin binding protein 5 (STXBP5) and neuronal leucine rich repeat 1 (NLRR1) genes. Syntaxin 5 regulates synaptic transmission at the presynaptic cleft and is known to inhibit synapse formation. Syntaxin 1 protein is increased in those with high functioning autism. The role of NLRR1 at the synaptic level is unknown but is thought to be related to neuronal growth [24].

An autism genome-wide copy number variation study reported by Glessner et al. [25] in a large cohort of ASD cases compared with controls showed that NRXN1 and CNTN4 genes play a role. They also described new susceptibility genes, NLGN1 and ASTN2 which encode neuronal cell-adhesion molecules and other genes involved in the ubiquitin pathways (UBE3A, PARK2, RFWD2 and FBXO40), two important gene networks expressed in the central nervous system.

Next generation DNA sequencing is currently underway, allowing for rapid and efficient detection of mutations at the nuclear and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) level in human investigations and becoming part of clinical workup. Heteroplasmy or the existence of multiple mtDNA types within cells of an individual, is detectable using standard molecular genetic techniques which focus on hypervariable regions of the mitochondrial genome. With high-throughput next generation sequencing of the complete human mtDNA, which is faster and more powerful, accurate detection of heteroplasmy can be made throughout the mitochondrial genome not just in the hypervariable regions located in the cytoplasm of the cell enabling the study of correlation with diseases.

Recently, Li et al. [26] sequenced the mitochondrial genome of 131 healthy individuals of European ancestry. They identified 37 heteroplasmies at 10% frequency or higher in 32 individuals and located at 34 different sites of the mtDNA indicating that variation commonly occurs in mtDNA. These variations may impact on energy levels and influence brain development and function. Next generation sequencing should provide novel insights into genome-wide aspects of mtDNA variation or heteroplasmy useful in the study of human disorders including autism.

With a significant percentage of children with autism presenting with metabolic abnormalities (e.g., high lactate levels) and other biochemical disturbances, identification of mitochondrial disorders is critical for early treatment. Long standing mitochondrial dysfunction can lead to major health complications and damage. If identified early, mitochondrial disorders can be managed with improved longevity and quality of life. Medical intervention and therapies are now available to specifically target the biochemical defect in the mitochondria and to improve function and bioenergy utilization and diminish the neurological insults that would occur if left untreated.

MITOCHONDRIAL ROLE IN AUTISM

Metabolic Effects

Inborn errors of metabolism may contribute to at least 5% of cases with ASD [27]. Deficiency of certain enzymes in metabolic disorders leads to an accumulation of substances that can cause toxic effects on the developing brain, contributing to ASD. A common example is phenylketonuria, an autosomal recessive condition leading to excessive phenylalanine levels, mental retardation and ASD, if not diet-controlled. Other related conditions include purine metabolism errors (adenylosuccinase deficiency and adenosine deaminase deficiency), creatine deficiency syndromes, Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome, biotinidase deficiency and histidinemia. Early screening and treatment of these conditions may have a positive impact in preventing disease progress. For example, the prevalence of individuals affected with phenylketonuria has decreased from 20% to 6% with early detection during infancy and dietary intervention to control phenylalanine intake [28, 29]. Once mitochondrial abnormalities are better elucidated, similarly preventive intervention may become available.

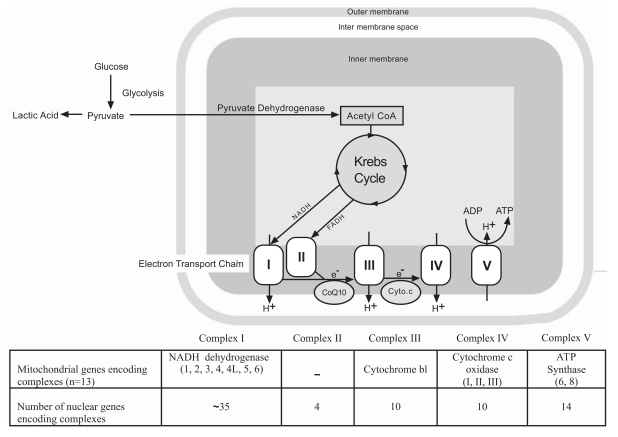

Mitochondria are intracellular organelles in the cytoplasm known as the power houses of the cell. They play a crucial role in adenosine 5’-triphosphate (ATP) production through oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). The latter process is carried out by the electron transport chain made up of Complex I (NADH: Ubiquinone oxidoreductase or dehydrogenase), Complex II (Succinate:Ubiquinone oxidoreductase), Complex III (Coenzyme Q:Cytochrome c reductase or cytochrome bc1 complex), and Complex IV (Cytochrome c oxidase) required to convert food sources to cellular energy. The electron transport system is situated in the inner membrane of the mitochondria and contains proteins encoded by both nuclear and mitochondrial DNA [30]. About 100 proteins coded by both mitochondrial and nuclear genes are required for assembly of the complexes for the respiratory chain [31, 32]. The mitochondrial genome encodes 13 of these 100 proteins [33] (see Fig. 1).

Fig. (1).

Mitochondrial Structure and Function.

Human mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is a circular double stranded DNA molecule contained within the mitochondrion and inherited solely from the mother. The evolutionary antecedents are bacterial plasmids. Each mitochondrion contains 2-10 mtDNA copies organized into nucleoids [33]. This organization is important to carry out segregation, replication and transcription of mtDNA [33, 34]. In humans, 100-10,000 separate copies of mtDNA are usually present per cell, although an ovum contains about 50,000-5,000,000 mitochondria [33-35] each containing mtDNAs, while sperm cells only have about 50-100 mitochondria each.

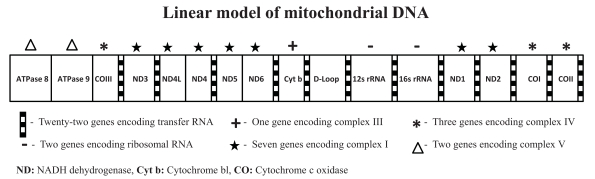

Mitochondria are dynamic organelles that fuse and produce fission by changing shapes and size throughout the life of the cell. Thus far, the mitochondria cannot yet be accurately quantified but mtDNA can be analyzed. In mammals, each double-stranded circular mtDNA molecule consists of 15,000-17,000 base pairs containing a total of 37 genes (for production of 13 oxidative phosphorylation proteins used to generate ATP, 22 genes for transfer RNA and two for ribosomal RNA) (see Fig. 2). When a mutation arises in a cellular mtDNA, it creates a mixed intracellular population of mutant and normal molecules known as heteroplasmy. When a cell divides, it is a matter of chance whether the mutant mtDNAs will be partitioned into one daughter cell or another. Therefore, over time, the percentage of mutant mtDNAs in different cell lineages can drift toward either pure mutant or normal (homoplasmy), a process known as replicative segregation, which then impacts on cellular energy and human diseases [36-38].

Fig. (2).

Linear Model of the Mitochondrial DNA Molecule.

Mitochondrial disorders may present in early childhood or later in life. Human mitochondrial diseases due to homoplasmy for all mutant mtDNA copies often present early in childhood. Heteroplasmy may involve only a few mutant copies with the remaining copies being unaffected. Individuals with heteroplasmic mutational disorders may not display symptoms until adulthood or after many cell divisions, whereby a threshold number of abnormal mitochondria with mutant alleles result in disease. The disease Neuropathy with muscle weakness, Ataxia, and Retinitis Pigmentosa (NARP) is caused by T8993G heteroplasmic mtDNA mutations. When heteroplasmy is present in less than 10 percent of copies, NARP findings are usually absent. At 10-70 percent, adult onset NARP is present, and at 70-100 percent childhood Leigh syndrome occurs. Other examples of known mitochondrial diseases include Myoclonic Epilepsy with Ragged Red Fibers (MERRF) and the disorder known as Mitochondria Encephalomyopathy, Lactic Acidosis, and Stroke-like episodes (MELAS) (summarized by Wallace [37, 38]).

In the mitochondria ATP production, free oxygen radicals and reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced and then normally removed from the cells by anti-oxidant enzymes. When the production of ROS and free radicals exceeds the limit, oxidative stress occurs, that is, ROS combine with lipids, nucleic acids and proteins in the cells leading to cell death by apoptosis or necrosis [39]. Since brain cells have limited antioxidant activity, a high lipid content and high requirement for energy, it is more prone to the effects of oxidative stress [40].

Coleman and Blass in [41] were the first to link to bioenergy metabolism disturbances with ASD. They reported lactic acidosis in four children with autism. Later, Laszlo et al. [42] reported increased serotonin, lactic acid and pyruvate levels in children with autism. Lombard [43] then proposed that mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation defects could cause abnormal brain metabolism in children with autism, leading to lactic acidosis and decreased serum carnitine levels. Conversely, Correia et al. [44] studied 196 children with autism and found that 17% had high lactic acid levels and 53 had an elevated lactate to pyruvate ratio. Additionally, muscle biopsies performed in 30 of the children with autism showed a mitochondrial defect in 7 of the children. Muscle biopsies studied by Tsao and Mendell [45] in two unrelated girls with autism showed partial complex I deficiency and coenzyme Q10 deficiency in one girl and partial deficiency of complexes II, III and IV in the other. Both girls had normal serum amino acids, ammonia, lactate, urine organic acids and normal karyotyes as well as negative DNA studies for Rett and fragile X syndromes.

Recently, Shoffner and colleagues [46] studied 28 children diagnosed with ASD for mitochondrial diseases and found high levels of lactate, pyruvate and alanine in the blood, urine and cerebrospinal fluid in 14 of the children. Using muscle biopsies, they identified a mitochondrial complex I defect in 50% (14/28) of the affected children, combined complex I and III defects in 18% (5/28), combined complex I, III and IV defects in 18% (5/28) and isolated complex V defects in 14% (4/28). Seventy-one percent (20/28) of the children had abnormal oxidative phosphorylation after performing protein assessment studies on selected subunits for complexes I, II, III and IV. Their results suggested an even greater link between ASD and impairment in mitochondrial function. (see Table 1 for a summary of known mitochondrial and nuclear gene defects in ASD).

Table 1.

Reports of Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) Involving Mitochondrial and Nuclear Gene Defects

| References | Number of Subjects with ASD | Sample | MitochondrialComplex Defects | MitochondrialGene Defects | Nuclear Gene Defects | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laszlo et al., 1994 | 30 | Blood | Chromosome 18q deletion(1 of 30 subjects) | LA ↑ (13 of 30 subjects);Pyruvate ↑ (9 of 30 subjects) | ||

| Graf et al., 2000 | 1 | Blood, Muscle | I, IV | tRNALys(G8363A) | ||

| Fillano et al., 2002 | 12 | Muscle | I, III, IV, V (7 of 8 subjects) | mtDNA deletion (5 of 12 subjects);mtDNA defect (3 of 12 subjects) | ||

| Filipek et al., 2003 | 2 | Muscle | III | Chromosome 15q11-q13 duplication(2 of 2 subjects) | Carnitine ↓(2 of 2 subjects);Plasma alanine ↑ (1 of 2 subjects);Lactate ↑ (1 of 2 subjects);CPK ↑ (1 of 2 subjects) | |

| Pons et al., 2004 | 5 | Muscle | I, II, III, IV | tRNALeu (A3243G)(2 of 5 subjects) | Plasma lactate ↑ (2 of 3 subjects);CSF lactate ↑ (1 of 1 subject) | |

| Ramoz et al., 2004 | 411 | Blood | SNP (rs2056202 and rs2292813)in SLC25A12 of chromosome 2q31(197 of 411 subjects) | |||

| Oliveira et al., 2005 | 69 | Muscle | I, IV, V | No mutations seen | Plasma lactate ↑ (14 of 69 subjects) | |

| Segurado et al., 2005 | 174 | Blood,Buccal cells | SNP (rs2056202 and rs2292813)in SLC25A12 (158 of 174 subjects) | |||

| Correia et al., 2006 | 210 | Muscle | Multiple complex defects | Normal SLC25A12 | LA ↑ (36 of 210 subjects) | |

| Tsao & Mendell, 2007 | 2 | Muscle | II, III, IV | SNP (rs2056202 ) in SLC25A12 | CoQ10 ↑ deficiency (1 of 2 subjects) | |

| Weissman et al., 2008 | 25 | Blood, Muscle | I (16 of 23 subjects),II (2 of 23 subjects), III (5 of 23 subjects),IV (1 of 23 subjects) | mtDNA deletion(7 of 25 subjects) | Plasma lactate ↑ (19 of 25 subjects); Plasma pyruvate ↑ (9 of 17 subjects); Plasma CPK ↑ (8 of 25 subjects) | |

| Silverman et al., 2008 | 355 | Blood | SNP (rs2056202 and rs2292813)in SLC25A12 (170 of 355 subjects) | |||

| Shoffner et al., 2010 | 28 | Muscle, BloodCSF, Urine | I (14 of 28 subjects);I+III (5 of 28 subjects); V (4 of 28 subjects);I+III+IV (20 of 28 subjects) | mtDNA deletion(1 of 20 subjects) | Plasma lactate ↑;CoQ10 deficiency (1 of 14 subjects) | |

| Giulivi et al., 2010 | 10 | Blood | Decreased NADH oxidase (8 of 10 subjects);I (6 of 10 subjects);IV (3 of 10 subjects);V (4 of 10 subjects) | mtDNA over-replication (5 of 10 subjects);Cytochrome b1 gene deletion (2 of 10 subjects) | Succinase oxidase (6 of 10 subjects);Pyruvate dehyrogenase (8 of 10 subjects) | |

| Ezugha et al., 2010 | 1 | I, IV | 1Mb deletion in chromosome 5q14.3 |

CPK = creatine phosphokinase; LA = lactic acidosis; CSF = cerebral spinal fluid.

Mitochondrial Gene Defects

Early cases reported by Graf and colleagues [47] provide examples of mtDNA mutations and enzyme defects. They described a brother and sister with mtDNA G8363A transfer RNA (tRNAlys) mutations. The 3 year old boy met the diagnostic criteria for autism at 4 years of age and showed a 60% mutation rate in muscle tissue and 61% in blood. His mitochondrial markers of lactate and pyruvate levels were normal following a carbohydrate loading test. The activity of the mitochondria respiratory chain (MRC) was measured for complexes I, II, III, IV and citrate synthetase. This boy had high activity for mitochondrial enzyme levels suggested by ratios of complex I to citrate synthetase, but normal activity for complexes II, III and IV. His sister at age 6 years was diagnosed with Leigh syndrome, a neurometabolic disorder affecting the brain and manifesting between 3 months and 2 years of age due to mutations of mtDNA or nuclear genes involving mainly complex I. She was found to have the same mtDNA mutation but present at an 86% level in the muscle and 82% in blood, with increased lactate levels and low mitochondrial enzyme activity. This study of G8363A mtDNA mutations in autism stresses the importance of biochemical mitochondrial markers and mtDNA mutations requiring further investigations.

In addition, Pons et al. [48] followed five unrelated children with ASD and reported abnormal respiratory chain enzyme activity. A mtDNA gene mutation at position A3243G was found in four of the five children. High cerebral lactic acid levels were identified using brain magnetic resonance spectroscopy in three of the five subjects. One child with ASD had an older sister with the mtDNA deletion syndrome (MDS), that is, a decreased quantity of mtDNA with a reduced number of mtDNA molecules per cell. MDS is an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by a quantitative defect in the copy number or amount of mtDNA and recently linked to two nuclear genes, dGK and TK2. The sister had no depletion of the mtDNA or mutations in the two nuclear genes. However, they did have mtDNA depletion in the skeletal muscle at a 72% level. These findings highlight the importance of the A3243G mtDNA mutation in ASD and the investigators proposed that mutations or depletion of mtDNA should be investigated in other children presenting with ASD.

Oliveira et al. [49] reported to date the only population-based ascertainment of children with ASD and mitochondrial dysfunction. They identified high lactate levels in 14 of 69 children with ASD. High lactate-to-pyruvate level ratios occurred in 11 of the 14 children; deltoid muscle biopsies were performed in the 11 children for respiratory chain abnormalities. Point mutations were examined in the mtDNA at positions G8363A, A3243G, T3271C, T3256C, and T8356C, as well as mtDNA levels or depletions. While 5 of the 11 children showed definite mitochondrial respiratory disorders, using the clinical and laboratory diagnostic criteria reported by Bernier et al. [50], but no mtDNA genetic defects were observed. Later, Oliveira et al. [51] reported on genetic and associated medical conditions occurring in children with ASD and showed 5 percent with chromosome disorders, 4 percent with mitochondrial disorders, 3 percent with single gene disorders, 3 percent with infectious diseases, 3 percent with genomic syndromes or birth defects and the remaining cases having idiopathic (unknown) causes. Their study further confirmed the role of the electron transport chain in the mitochondria and autism. Although they did not find large deletions in the mitochondrial DNA, lack of analysis for microdeletions, mutations and depletion of mtDNA were limitations of the study.

An interesting study by Fillano et al. [52] further illustrates the importance of the mitochondria in children with features of ASD. They evaluated 12 children with HEADD syndrome (hypotonia, epilepsy, autism and developmental delay) for mitochondrial abnormalities by examining electron transport chain respiratory activity, mitochondrial structure and deletions or point mutations of mtDNA genes or the amount of mtDNA present. They documented decreased activity of the mitochondrial respiratory complexes (I, III, IV and V) mainly in enzymes encoded by mtDNA, in seven of eight subjects studied. However, seven individuals had normal mitochondrial structure while five had decreased or depleted amounts of mtDNA. Lastly, structural defects in the mitochondria were found in three of the four subjects studied. Interestingly, seven children with mitochondrial enzyme defects had no mutations or structural defects in the mitochondria and only one child with a mutation had no enzyme defects. Thus, it is too preliminary to hypothesize that enzyme defects are independent of mtDNA mutations or structural defects. The presence of enzyme defects at a later age is unknown. More studies are required to follow these children into later life. In this study, mtDNA point mutations were not seen although a 7.4kb mtDNA mutation was observed in a child. Later, Pons et al. [48] found that 72% of the mtDNA genome was absent or depleted in a child with PDD having a history of mtDNA depletion syndrome in an older sister. The use of newer genetic techniques such as mtDNA microarrays and sequencing along with related nuclear genes (coding and non-coding RNA) will be useful to characterize the mitochondrial genome for depletion status or mutations.

Relationship of Nuclear Genes

Studies reviewed by Smith et al. [53] linked nuclear genes and mtDNA in ASD, for example, the nuclear gene, SLC23A12. This most important gene located on chromosome 21q31 encodes a calcium-binding carrier protein used by the mitochondria. It is involved in the exchange of the amino acid aspartate for glutamate in the inner membrane of the mitochondria for use in the electron transport chain. Ramoz et al. [54] identified two single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs-rs2056202 and rs2292813) in the SLC25A12 gene associated with ASD in their study of 411 families. This association was confirmed by Seguarado et al. [55] and by Silverman et al. [56].

A recent study by Ezugha et al. [57] of a 12-year old male with dysmorphic facies, intellectual disability, autism, epilepsy and leg weakness identified decreased activity of mitochondrial complexes I and IV. A 1 Mb deletion was found on chromosome 5q14.3 band. They suggested that the features seen in this child were consistent with mitochondrial dysfunction and a nuclear gene is located on chromosome 5 coding for protein involved in activity of these mitochondrial complexes. Correia et al. [44] also studied the linkage of this gene in an additional 241 families and found high lactate levels and lactate/pyruvate ratios. However, they did not find SNPs for the SLC23A12 gene in their families with autism. Also, Chien et al. [58] studied 465 individuals with ASD but did not find any SNP changes in the SLC23A12 gene.

Role of the Nuclear Genome in Mitochondrial DNA Replication, Maintenance and Depletion

Mitochondrial DNA replication and maintenance is regulated by enzymes which are proteins encoded by nuclear DNA genes [59]. One such nuclear gene is DNA polymerase gamma 1 (POLG1) which codes for mitochondrial DNA polymerase [60]. This gene is involved in the production of mtDNA and has been linked to various mitochondrial conditions. Therefore, mutations in nuclear genes required for mtDNA replication may affect mtDNA function.

Studies have examined the role of nuclear genes in causing depletion of the mtDNA genome and tissue specific conditions [61, 62]. Mandel and colleagues [61] observed neuronal symptoms with increased lactic acid levels in 19 children with deoxyguanosine kinase dGUOK gene mutations and hepatic failure with reductions in activity of mitochondrial complexes I, II and IV. However, the enzyme activity for complex II, which is encoded by nuclear DNA, was normal in these patients. Furthermore, quantitative mtDNA analysis showed a reduced mtDNA/nuclear DNA ratio of 8-39% in liver specimens from seven of the children.

The main supply for dNTPs required for energy comes from the deoxynucleoside salvage pathway regulated by two mitochondrial enzymes dGK and TK2, encoded by the nuclear genome [63, 64]. Hence, Mandel et al. [61] examined nuclear genes and found that dGK was mutated in patients with reduced mtDNA/nuclear DNA ratios. A similar study by Saada et al. [62] in two of four individuals with known mitochondrial depleted myopathy showed a mutation in the TK2 nuclear gene. These two studies further supported that nuclear genes are linked to mtDNA but more research is needed to determine their role in autism and for identification of mtDNA genetic defects, mutations or for the mtDNA depletion status associated with related nuclear genome defects.

Polymerase gamma (POLG1) is an important polymerase enzyme responsible for mtDNA replication and base excision repair [60]. The nuclear gene encoding the POLG1 enzyme is located on chromosome band 15q25 [65, 66]. Any mutation in this gene will impact mtDNA replication and repair processes. Interestingly, in humans, maternal disomy 15 (both chromosome 15s from the mother) is seen in about 25% of subjects with Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS), the most common known syndromic cause of morbid obesity in humans [67]. PWS is frequently associated with ASD particularly in those subjects with PWS due to maternal disomy 15 and associated with a lower metabolic rate [68]. Therefore, maternal disomy 15 in PWS could also influence the activity of the POLG1 gene. Studies have shown that mutations or disturbances of the POLG1 gene cause deletions of mtDNA genes. Additionally, autism is linked to defects of human chromosome 15q11-q13 region including inverted duplications found in about 5% of cases with autism [12]. Filipek et al. [69] further reported that subjects with 15q11-q13 duplications and ASD have increased mitochondria and mitochondrial respiratory chain blockage at complex IV, but lactate levels were not significantly elevated. While this study did not examine for mtDNA mutations, it established a link between genes in the nucleus specifically on chromosome 15q11-q13 and an interplay with mitochondrial function in subjects with autism.

Van Goethem et al. [70] showed that autosomal dominant progressive external opthalmoplegia (adPEO) is due to POLG1 gene mutations leading to mtDNA deletions. Apart from POLG1, the autosomal dominant type of PEO has been linked to the TWINKLE gene on chromosome 10q [35] and the ANT1 gene on chromosomal 4q [71]. These nuclear gene mutations are known to cause mtDNA disturbances.

POLG1 has been linked to many conditions apart from adPEO. For example, it causes autosomal recessive PEO, sensory-ataxic neuropathy, dysarthria and opthalmoplegia (SANDO), juvenile spino-cerebellar ataxia-epilepsy syndrome (SCAE) and Alpers-Huttenlocher hepatopathic poliodystrophy. These encephalomyopathies are caused by abnormal nuclear mitochondrial intergenomic cross-talk linked to POLG1 gene mutations and to mtDNA deletions. This strong link between nuclear genes and the mtDNA genome is further supported by a prevalence of 2% of individuals in the general population carrying this nuclear gene defect [59].

Another nuclear gene that can cause multiple mtDNA abnormalities including duplications, deletions and point mutations is thymidine phosphorylase (TP) [72, 73]. The TP nuclear gene is located on chromosome 22q13 [74] and encodes the cytosolic enzyme regulating pyrimidine nucleoside levels through phosphorolytic thymidine catabolism to thymidine and ribose [75]. Mitochondria neurogastrointestinal encephalopathy (MNGIE) results from loss of TP activity. Hence, the above studies have shown that mutations of nuclear genes TK2, DGK, PLOG, TWINKLE, ANT1 and TP can cause deletions and depletions of mtDNA, their involvement and frequency in ASD requires further investigation.

Finally, oxidative stress and gene methylation (epigenetics) are both considered to play a role in producing ASD. Oxidative stress in brain cells due to genetic or environmental causes, leads to decreased methionine synthase activity [76]. Methionine synthase action involves two processes: a) dopamine-stimulated phospholipid methylation which is required for synchronizing normal brain activity during attention; and b) DNA methylation which silences gene activity. During DNA methylation a methyl group is added to the cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) site and the methylated cytosine is converted to 5-methylcytosine; thus, inactivating gene expression. This is a normal process. One can propose that the important interaction between methionine metabolism and methylation with overall reactions of folate and B12 metabolism is regulated by mitochondrial reduction/oxidative reactions controlling nuclear gene methylation (epigenetics or methylomics) and glutathione metabolism. When disturbed, this process contributes to ASD [77]. When methionine synthase activity is impaired, children may manifest attentional impairment and other symptoms from defective gene expression leading to ASD.

Deth et al. [78] further reported the involvement of various genes in the process of methylation with the most important being methyl-CpG-binding (MeCP2) protein. Abnormal MeCP2 protein is linked to Rett syndrome and ASD [79]. MeCP2 participates in gene silencing by binding to the methylated genes in the brain. Any mutation of this gene impacts on the expression status of known methylated genes and therefore interferes with epigenetics.

Oxidative stress is also known to cause deletions of the mtDNA genes in mice models [80]. For example, chronically-administered intraperitoneal injections of the chemotherapeutic agent, doxorubicin, in mice has resulted in a 4kb deletion of the mtDNA in heart muscle. In addition, Lu et al. [81] indirectly confirmed these findings by reporting mtDNA deletions in ageing skin from humans with increased free oxygen radicals and reactive oxygen species and further support the basis for examining mtDNA or gene deletions in ASD.

To further evaluate for mitochondrial dysfunction and mtDNA abnormalities, Giulivi et al. [82] recently studied lymphocytes from 10 children with ASD and 10 controls aged 2 to 5 years. The outcome measures included oxidative phosphorylation capacity at the cell level, mtDNA copy number, mitochondrial rate of hydrogen peroxide production, and plasma lactate and pyruvate levels. The majority of the children with ASD (6 of 10) had lower mitochondrial complex I activity than found in controls. Higher plasma pyruvate levels occurred in 8 of 10 children with ASD compared with controls consistent with a lower pyruvate dehydrogenase activity. Hence, children with ASD had higher mitochondrial rates of hydrogen peroxide production than in controls. Mitochondrial genome studies showed mitochondrial DNA overreplication in 5 children with ASD and mtDNA deletions involving the segment coding for cytochrome b in 2 children with ASD. Therefore, the children with ASD were more likely to have mitochondrial dysfunction, mtDNA overreplication, and/or mtDNA deletions than typically developing children.

In summary, the role of the mitochondria and mitochondrial defects are discussed in relationship to ASD. Several studies have linked autism to defects in oxidative phosphorylation encoded by mtDNA along with interaction of nuclear genes. Individuals with the ASD phenotype clearly show genetic-based primary mitochondrial disease. Further studies with the latest genetic technology such as next generation sequencing, microarrays, bioinformatics and biochemical assays will be required to determine the prevalence and type of mitochondrial defects in ASD. Elucidation of molecular abnormalities resulting from mitochondrial or genetic defects in individuals with ASD may lead to better treatment options and outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge the families with autism who stimulated the undertaking of this review. This study was supported by the Kansas Center for Autism Research and Training (KCART) and grant NICHD HD02528. We thank Carla Meister for her expert preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kanner L. Autistic psychopathy in childhood. Nervous Child. 1943;2:217–250. [Google Scholar]

- 2.APA. Diagnostics and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington D.C: American Psychiatric Association Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson CP, Myers SM. Identification and evaluation of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2007;120(5):1183–1215. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, Cook EH, Jr., Leventhal BL, DiLavore PC, Pickles A, Rutter M. The autism diagnostic observation schedule-generic: a standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2000;30(3):205–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Le Couteur A, Lord C, Rutter M. Autism Diagnostic Interview - Revised (ADI-R) Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lord C, DiLavore PC, Risi S. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bailey A, Le Couteur A, Gottesman I, Bolton P, Simonoff E, Yuzda E, Rutter M. Autism as a strongly genetic disorder: evidence from a British twin study. Psychol. Med. 1995;25(1):63–77. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700028099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chakrabarti S, Fombonne E. Pervasive developmental disorders in preschool children. JAMA. 2001;285(24):3093–3099. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.24.3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le Couteur A, Bailey A, Goode S, Pickles A, Robertson S, Gottesman I, Rutter M. A broader phenotype of autism: the clinical spectrum in twins. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 1996;37(7):785–801. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1996.tb01475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piven J. The biological basis of autism. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1997;7(5):708–712. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(97)80093-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grafodatskaya D, Chung B, Szatmari P, Weksberg R. Autism spectrum disorders and epigenetics. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2010;49(8):794–809. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schroer RJ, Phelan MC, Michaelis RC, Crawford EC, Skinner SA, Cuccaro M, Simensen RJ, Bishop J, Skinner C, Fender D, Stevenson RE. Autism and maternally derived aberrations of chromosome 15q. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1998;76(4):327–336. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19980401)76:4<327::aid-ajmg8>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benvenuto A, Moavero R, Alessandrelli R, Manzi B, Curatolo P. Syndromic autism: causes and pathogenetic pathways. World J. Pediatr. 2009;5(3):169–176. doi: 10.1007/s12519-009-0033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Fishawy P, State MW. The genetics of autism: key issues, recent findings, and clinical implications. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 2010;33(1):83–105. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miles JH, Hillman RE. Value of a clinical morphology examination in autism. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2000;91(4):245–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schaefer GB, Lutz RE. Diagnostic yield in the clinical genetic evaluation of autism spectrum disorders. Genet. Med. 2006;8(9):549–556. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000237789.98842.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herman GE, Henninger N, Ratliff-Schaub K, Pastore M, Fitzgerald S, McBride KL. Genetic testing in autism: how much is enough? Genet. Med. 2007;9(5):268–274. doi: 10.1097/gim.0b013e31804d683b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miles JH, McCathren RB, Stichter J, Shinawi M. Autism Spectrum Disorders. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/pubmed . [accessed July 21].

- 19.Shen Y, Dies KA, Holm IA, Bridgemohan C, Sobeih MM, Caronna EB, Miller KJ, Frazier JA, Silverstein I, Picker J, Weissman L, Raffalli P, Jeste S, Demmer LA, Peters HK, Brewster SJ, Kowalczyk SJ, Rosen-Sheidley B, McGowan C, Duda AW, 3rd Lincoln SA, Lowe KR, Schonwald A, Robbins M, Hisama F, Wolff R, Becker R, Nasir R, Urion DK, Milunsky JM, Rappaport L, Gusella JF, Walsh CA, Wu BL, Miller DT. Clinical genetic testing for patients with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):e727–735. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernandez BA, Roberts W, Chung B, Weksberg R, Meyn S, Szatmari P, Joseph-George AM, Mackay S, Whitten K, Noble B, Vardy C, Crosbie V, Luscombe S, Tucker E, Turner L, Marshall CR, Scherer SW. Phenotypic spectrum associated with de novo and inherited deletions and duplications at 16p11.2 in individuals ascertained for diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. J. Med. Genet. 2010;47(3):195–203. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.069369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller DT, Shen Y, Weiss LA, Korn J, Anselm I, Bridgemohan C, Cox GF, Dickinson H, Gentile J, Harris DJ, Hegde V, Hundley R, Khwaja O, Kothare S, Luedke C, Nasir R, Poduri A, Prasad K, Raffalli P, Reinhard A, Smith SE, Sobeih MM, Soul JS, Stoler J, Takeoka M, Tan WH, Thakuria J, Wolff R, Yusupov R, Gusella JF, Daly MJ, Wu BL. Microdeletion/duplication at 15q13.2q13.3 among individuals with features of autism and other neuropsychiatric disorders. J. Med. Genet. 2009;46(4):242–248. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.059907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang K, Zhang H, Ma D, Bucan M, Glessner JT, Abrahams BS, Salyakina D, Imielinski M, Bradfield JP, Sleiman PM, Kim CE, Hou C, Frackelton E, Chiavacci R, Takahashi N, Sakurai T, Rappaport E, Lajonchere CM, Munson J, Estes A, Korvatska O, Piven J, Sonnenblick LI, Alvarez Retuerto AI, Herman EI, Dong H, Hutman T, Sigman M, Ozonoff S, Klin A, Owley T, Sweeney JA, Brune CW, Cantor RM, Bernier R, Gilbert JR, Cuccaro ML, McMahon WM, Miller J, State MW, Wassink TH, Coon H, Levy SE, Schultz RT, Nurnberger JI, Haines JL, Sutcliffe JS, Cook EH, Minshew NJ, Buxbaum JD, Dawson G, Grant SF, Geschwind DH, Pericak-Vance MA, Schellenberg GD, Hakonarson H. Common genetic variants on 5p14.1 associate with autism spectrum disorders. Nature. 2009;459(7246):528–533. doi: 10.1038/nature07999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sebat J, Lakshmi B, Malhotra D, Troge J, Lese-Martin C, Walsh T, Yamrom B, Yoon S, Krasnitz A, Kendall J, Leotta A, Pai D, Zhang R, Lee YH, Hicks J, Spence SJ, Lee AT, Puura K, Lehtimaki T, Ledbetter D, Gregersen PK, Bregman J, Sutcliffe JS, Jobanputra V, Chung W, Warburton D, King MC, Skuse D, Geschwind DH, Gilliam TC, Ye K, Wigler M. Strong association of de novo copy number mutations with autism. Science. 2007;316(5823):445–449. doi: 10.1126/science.1138659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakamura K, Anitha A, Yamada K, Tsujii M, Iwayama Y, Hattori E, Toyota T, Suda S, Takei N, Iwata Y, Suzuki K, Matsuzaki H, Kawai M, Sekine Y, Tsuchiya KJ, Sugihara G, Ouchi Y, Sugiyama T, Yoshikawa T, Mori N. Genetic and expression analyses reveal elevated expression of syntaxin 1A ( STX1A) in high functioning autism. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;11(8):1073–1084. doi: 10.1017/S1461145708009036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glessner JT, Wang K, Cai G, Korvatska O, Kim CE, Wood S, Zhang H, Estes A, Brune CW, Bradfield JP, Imielinski M, Frackelton EC, Reichert J, Crawford EL, Munson J, Sleiman PM, Chiavacci R, Annaiah K, Thomas K, Hou C, Glaberson W, Flory J, Otieno F, Garris M, Soorya L, Klei L, Piven J, Meyer KJ, Anagnostou E, Sakurai T, Game RM, Rudd DS, Zurawiecki D, McDougle CJ, Davis LK, Miller J, Posey DJ, Michaels S, Kolevzon A, Silverman JM, Bernier R, Levy SE, Schultz RT, Dawson G, Owley T, McMahon WM, Wassink TH, Sweeney JA, Nurnberger JI, Coon H, Sutcliffe JS, Minshew NJ, Grant SF, Bucan M, Cook EH, Buxbaum JD, Devlin B, Schellenberg GD, Hakonarson H. Autism genome-wide copy number variation reveals ubiquitin and neuronal genes. Nature. 2009;459(7246):569–573. doi: 10.1038/nature07953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li M, Schonberg A, Schaefer M, Schroeder R, Nasidze I, Stoneking M. Detecting heteroplasmy from high-throughput sequencing of complete human mitochondrial DNA genomes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010;87(2):237–249. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manzi B, Loizzo AL, Giana G, Curatolo P. Autism and metabolic diseases. J. Child Neurol. 2008;23(3):307–314. doi: 10.1177/0883073807308698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dennis M, Lockyer L, Lazenby AL, Donnelly RE, Wilkinson M, Schoonheyt W. Intelligence patterns among children with high-functioning autism, phenylketonuria, and childhood head injury. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 1999;29(1):5–17. doi: 10.1023/a:1025962431132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reiss AL, Feinstein C, Rosenbaum KN. Autism and genetic disorders. Schizophr. Bull. 1986;12(4):724–738. doi: 10.1093/schbul/12.4.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schon EA, Manfredi G. Neuronal degeneration and mitochondrial dysfunction. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111(3):303–312. doi: 10.1172/JCI17741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DiMauro S, Schon EA. Mitochondrial respiratory-chain diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348(26):2656–2668. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weissman JR, Kelley RI, Bauman ML, Cohen BH, Murray KF, Mitchell RL, Kern RL, Natowicz MR. Mitochondrial disease in autism spectrum disorder patients: a cohort analysis. PLoS One. 2008;3(11):e3815. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spelbrink JN. Functional organization of mammalian mitochondrial DNA in nucleoids: history, recent developments, and future challenges. IUBMB Life. 2010;62(1):19–32. doi: 10.1002/iub.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wiesner RJ, Ruegg JC, Morano I. Counting target molecules by exponential polymerase chain reaction: copy number of mitochondrial DNA in rat tissues. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1992;183(2):553–559. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)90517-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spelbrink JN, Li FY, Tiranti V, Nikali K, Yuan QP, Tariq M, Wanrooij S, Garrido N, Comi G, Morandi L, Santoro L, Toscano A, Fabrizi GM, Somer H, Croxen R, Beeson D, Poulton J, Suomalainen A, Jacobs HT, Zeviani M, Larsson C. Human mitochondrial DNA deletions associated with mutations in the gene encoding Twinkle, a phage T7 gene 4-like protein localized in mitochondria. Nat. Genet. 2001;28(3):223–231. doi: 10.1038/90058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wallace DC. Mitochondrial genes and disease. Hosp. Pract. (Off Ed) 1986;21(10):77–87. 90–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wallace DC. Mitochondrial diseases in man and mouse. Science. 1999;283(5407):1482–1488. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5407.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wallace DC. Bioenergetics and the epigenome: interface between the environment and genes in common diseases. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2010;16(2):114–119. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kannan K, Jain SK. Oxidative stress and apoptosis. Pathophysiology. 2000;7(3):153–163. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4680(00)00053-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Juurlink BH, Paterson PG. Review of oxidative stress in brain and spinal cord injury: suggestions for pharmacological and nutritional management strategies. J. Spinal. Cord. Med. 1998;21(4):309–334. doi: 10.1080/10790268.1998.11719540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coleman M, Blass JP. Autism and lactic acidosis. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 1985;15(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/BF01837894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laszlo A, Horvath E, Eck E, Fekete M. Serum serotonin, lactate and pyruvate levels in infantile autistic children. Clin. Chim. Acta. 1994;229(1-2):205–207. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(94)90243-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lombard J. Autism: a mitochondrial disorder? Med. Hypotheses. 1998;50(6):497–500. doi: 10.1016/s0306-9877(98)90270-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Correia C, Coutinho AM, Diogo L, Grazina M, Marques C, Miguel T, Ataide A, Almeida J, Borges L, Oliveira C, Oliveira G, Vicente AM. Brief report: High frequency of biochemical markers for mitochondrial dysfunction in autism: no association with the mitochondrial aspartate/glutamate carrier SLC25A12 gene. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2006;36(8):1137–1140. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0138-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsao CY, Mendell JR. Autistic disorder in 2 children with mitochondrial disorders. J. Child Neurol. 2007;22(9):1121–1123. doi: 10.1177/0883073807306266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shoffner J, Hyams L, Langley GN, Cossette S, Mylacraine L, Dale J, Ollis L, Kuoch S, Bennett K, Aliberti A, Hyland K. Fever plus mitochondrial disease could be risk factors for autistic regression. J. Child Neurol. 2010;25(4):429–434. doi: 10.1177/0883073809342128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Graf WD, Marin-Garcia J, Gao HG, Pizzo S, Naviaux RK, Markusic D, Barshop BA, Courchesne E, Haas RH. Autism associated with the mitochondrial DNA G8363A transfer RNA(Lys) mutation. J. Child Neurol. 2000;15(6):357–361. doi: 10.1177/088307380001500601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pons R, Andreu AL, Checcarelli N, Vila MR, Engelstad K, Sue CM, Shungu D, Haggerty R, de Vivo DC, DiMauro S. Mitochondrial DNA abnormalities and autistic spectrum disorders. J. Pediatr. 2004;144(1):81–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2003.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oliveira G, Diogo L, Grazina M, Garcia P, Ataide A, Marques C, Miguel T, Borges L, Vicente AM, Oliveira CR. Mitochondrial dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders: a population-based study. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2005;47(3):185–189. doi: 10.1017/s0012162205000332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bernier FP, Boneh A, Dennett X, Chow CW, Cleary MA, Thorburn DR. Diagnostic criteria for respiratory chain disorders in adults and children. Neurology. 2002;59(9):1406–1411. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000033795.17156.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oliveira G, Ataide A, Marques C, Miguel TS, Coutinho AM, Mota-Vieira L, Goncalves E, Lopes NM, Rodrigues V, Carmona da Mota H, Vicente AM. Epidemiology of autism spectrum disorder in Portugal: prevalence, clinical characterization, and medical conditions. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2007;49(10):726–733. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fillano JJ, Goldenthal MJ, Rhodes CH, Marin-Garcia J. Mitochondrial dysfunction in patients with hypotonia, epilepsy, autism, and developmental delay: HEADD syndrome. J. Child Neurol. 2002;17(6):435–439. doi: 10.1177/088307380201700607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith M, Spence MA, Flodman P. Nuclear and mitochondrial genome defects in autisms. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009;1151:102–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2008.03571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ramoz N, Reichert JG, Smith CJ, Silverman JM, Bespalova IN, Davis KL, Buxbaum JD. Linkage and association of the mitochondrial aspartate/glutamate carrier SLC25A12 gene with autism. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2004;161(4):662–669. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Segurado R, Conroy J, Meally E, Fitzgerald M, Gill M, Gallagher L. Confirmation of association between autism and the mitochondrial aspartate/glutamate carrier SLC25A12 gene on chromosome 2q31. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2005;162(11):2182–2184. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Silverman JM, Buxbaum JD, Ramoz N, Schmeidler J, Reichenberg A, Hollander E, Angelo G, Smith CJ, Kryzak LA. Autism-related routines and rituals associated with a mitochondrial aspartate/glutamate carrier SLC25A12 polymorphism. Am. J. Med. Genet. B. Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2008;147(3):408–410. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ezugha H, Goldenthal M, Valencia I, Anderson CE, Legido A, Marks H. 5q14.3 deletion manifesting as mitochondrial disease and autism: case report. J. Child Neurol. 2010;25(10):1232–1235. doi: 10.1177/0883073809361165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chien WH, Wu YY, Gau SS, Huang YS, Soong WT, Chiu YN, Chen CH. Association study of the SLC25A12 gene and autism in Han Chinese in Taiwan. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2010;34(1):189–192. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Spinazzola A, Zeviani M. Disorders of nuclear-mitochondrial intergenomic signaling. Gene. 2005;354:162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Graziewicz MA, Longley MJ, Copeland WC. DNA polymerase gamma in mitochondrial DNA replication and repair. Chem. Rev. 2006;106(2):383–405. doi: 10.1021/cr040463d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mandel H, Szargel R, Labay V, Elpeleg O, Saada A, Shalata A, Anbinder Y, Berkowitz D, Hartman C, Barak M, Eriksson S, Cohen N. The deoxyguanosine kinase gene is mutated in individuals with depleted hepatocerebral mitochondrial DNA. Nat. Genet. 2001;29(3):337–341. doi: 10.1038/ng746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Saada A, Shaag A, Mandel H, Nevo Y, Eriksson S, Elpeleg O. Mutant mitochondrial thymidine kinase in mitochondrial DNA depletion myopathy. Nat. Genet. 2001;29(3):342–344. doi: 10.1038/ng751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jullig M, Stott NS. Mitochondrial localization of Smad5 in a human chondrogenic cell line. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;307(1):108–113. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang L, Limongelli A, Vila MR, Carrara F, Zeviani M, Eriksson S. Molecular insight into mitochondrial DNA depletion syndrome in two patients with novel mutations in the deoxyguanosine kinase and thymidine kinase 2 genes. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2005;84(1):75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Clayton DA. Nuclear-mitochondrial intergenomic communication. Biofactors. 1998;7(3):203–205. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520070307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pinz KG, Bogenhagen DF. Characterization of a catalytically slow AP lyase activity in DNA polymerase gamma and other family A DNA polymerases. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275(17):12509–12514. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.17.12509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Butler MG. Prader-Willi syndrome: current understanding of cause and diagnosis. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1990;35(3):319–332. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320350306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Butler MG, Theodoro MF, Bittel DC, Donnelly JE. Energy expenditure and physical activity in Prader-Willi syndrome: comparison with obese subjects. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2007;143(5):449–459. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Filipek PA, Juranek J, Smith M, Mays LZ, Ramos ER, Bocian M, Masser-Frye D, Laulhere TM, Modahl C, Spence MA, Gargus JJ. Mitochondrial dysfunction in autistic patients with 15q inverted duplication. Ann. Neurol. 2003;53(6):801–804. doi: 10.1002/ana.10596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Van Goethem G, Dermaut B, Lofgren A, Martin JJ, Van Broeckhoven C. Mutation of POLG is associated with progressive external ophthalmoplegia characterized by mtDNA deletions. Nat. Genet. 2001;28(3):211–212. doi: 10.1038/90034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kaukonen J, Juselius JK, Tiranti V, Kyttala A, Zeviani M, Comi GP, Keranen S, Peltonen L, Suomalainen A. Role of adenine nucleotide translocator 1 in mtDNA maintenance. Science. 2000;289(5480):782–785. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hirano M, Silvestri G, Blake DM, Lombes A, Minetti C, Bonilla E, Hays AP, Lovelace RE, Butler I, Bertorini TE, et al. Mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalomyopathy (MNGIE): clinical, biochemical, and genetic features of an autosomal recessive mitochondrial disorder. Neurology. 1994;44(4):721–727. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.4.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nishigaki Y, Marti R, Hirano M. ND5 is a hot-spot for multiple atypical mitochondrial DNA deletions in mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalomyopathy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2004;13(1):91–101. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mancuso M, Filosto M, Bonilla E, Hirano M, Shanske S, Vu TH, DiMauro S. Mitochondrial myopathy of childhood associated with mitochondrial DNA depletion and a homozygous mutation (T77M) in the TK2 gene. Arch. Neurol. 2003;60(7):1007–1009. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.7.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Focher F, Spadari S. Thymidine phosphorylase: a two-face Janus in anticancer chemotherapy. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 2001;1(2):141–153. doi: 10.2174/1568009013334232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.James SJ, Cutler P, Melnyk S, Jernigan S, Janak L, Gaylor DW, Neubrander JA. Metabolic biomarkers of increased oxidative stress and impaired methylation capacity in children with autism. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004;80(6):1611–1617. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Naviaux RK. Mitochondrial control of epigenetics. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2008;7(8):1191–1193. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.8.6741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Deth R, Muratore C, Benzecry J, Power-Charnitsky VA, Waly M. How environmental and genetic factors combine to cause autism: A redox/methylation hypothesis. Neurotoxicology. 2008;29(1):190–201. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Loat CS, Curran S, Lewis CM, Duvall J, Geschwind D, Bolton P, Craig IW. Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 polymorphisms and vulnerability to autism. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7(7):754–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2008.00414.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Adachi K, Fujiura Y, Mayumi F, Nozuhara A, Sugiu Y, Sakanashi T, Hidaka T, Toshima H. A deletion of mitochondrial DNA in murine doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993;195(2):945–951. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lu CY, Lee HC, Fahn HJ, Wei YH. Oxidative damage elicited by imbalance of free radical scavenging enzymes is associated with large-scale mtDNA deletions in aging human skin. Mutat. Res. 1999;423(1-2):11–21. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(98)00220-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Giulivi C, Zhang YF, Omanska-Klusek A, Ross-Inta C, Wong S, Hertz-Picciotto I, Tassone F, Pessah IN. Mitochondrial dysfunction in autism. JAMA. 2010;304(21):2389–2396. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]