Abstract

Objective:

To determine the effects of parenteral omega 3 fatty acids (10% fatty acids) on respiratory parameters and outcome in ventilated patients with acute lung injury.

Measurements and Main Results:

Patients were randomized into two groups – one receiving standard isonitrogenous isocaloric enteral diet and the second receiving standard diet supplemented with parenteral omega 3 fatty acids (Omegaven, Fresenius Kabi) for 14 days. Patients demographics, APACHE IV, Nutritional assessment and admission category was noted at the time of admission. No significant difference was found in nutritional variables (BMI, Albumin). Compared with baseline PaO2/FiO2 ratio (control vs. drug group: 199 ± 124 vs. 145 ± 100; P = 0.06), by days 4, 7, and 14, patients receiving the drug did not show a significant improvement in oxygenation (PaO2/FiO2: 151.83 ± 80.19 vs. 177.19 ± 94.05; P = 0.26, 145.20 ± 109.5 vs. 159.48 ± 109.89; P = 0.61 and 95.97 ± 141.72 vs. 128.97 ± 140.35; P = 0.36). However, the change in oxygenation from baseline to day 14 was significantly better in the intervention as compared to control group (145/129 vs. 199/95; P < 0.0004). There was no significant difference in the length of ventilation (LOV) and length of ICU stay (LOS). There was no difference in survival at 28 days. Also, there was no significant difference in the length of ventilation and ICU stay in the survivors group as compared to the non survivors group.

Conclusions:

In ventilated patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome, intravenous Omega 3 fatty acids alone do not improve ventilation, length of ICU stay, or survival.

Keywords: Acute lung injury, enteral diet, length of stay, mechanical ventilation, oxygenation, parenteral Omega 3 fatty acids

Introduction

Advances in the ventilatory management of acute lung injury (ALI) and ARDS over the past decade have been dramatic. In particular, the use of a low-tidal volume (6 mL/kg predicted body weight) and plateau pressure-limited strategy has been demonstrated to reduce mortality from 40% to 31%.[1] Further, a large, multicenter, randomized, controlled trial,[2] demonstrated the equivalence of higher and lower levels of positive end-expiratory pressure. Over this time, a number of nonventilatory therapies for ALI/ARDS have been investigated. Many of these have not proven to be effective, while others appear more promising, lipids being one of them.

The lipid emulsions generally used in the parenteral nutrition of critically ill patients are rich in long-chain triglycerides (LCT), especially linoleic acid (polyunsaturated series 6 fatty acid; PUFA n-6, 18:2 n-6). These fatty acids, aside from producing adverse metabolic effects (transitory hyperlipidemias), can alter pulmonary gas exchange due to their potentially proinflammatory properties. The MCT/LCT emulsions are oxidized faster and provide fewer amounts of PUFAs than LCT emulsions. Thus, MCT/LCT emulsions have been associated with a lower risk of lipid peroxidation and fewer alterations of membrane structures.[3] Polyunsaturated fatty acids of the n-3 series (PUFA n-3) are precursors of biologically active substances, e.g., the series 3 and 5 eicosanoids. These molecules use the same metabolic routes and compete for the same elongases and desaturases as linoleic and arachidonic, but ultimately they are mediators that have a much less active biological profile than linoleic acid derivatives.[4]

In 146 patients with ARDS treated with an enteral diet rich in eicosapentaenoic acid, γ-linolenic, and antioxidants, an improved PaO2/FiO2 ratio, a reduction in pulmonary inflammatory response, frequency of new organ failures, days of mechanical ventilation and length of stay in ICU were observed.[5] In 100 patients with acute pulmonary injury receiving a similar enteral diet, oxygenation was better, pulmonary compliance improved, and there was less need for mechanical ventilation.[6] The administration of lipid emulsions has been associated with changes in pulmonary function that depends on pulmonary disease, dose, duration, speed of administration, and kind of infused lipids.[7,8] A meta-analysis of 12 randomized controlled trials comparing standard enteral nutrition with antioxidant nutrition found decreased rates of infection but again no effect on mortality.[9]

Many patients with ARDS require sedation/analgesia and muscle relaxation, inducing intestinal ileus and making intolerance to enteral nutrition. It has been hypothesized that adding n-3 to a MCT/LCT mixture used in enteral nutrition, should be beneficial because of the reduced amount of PUFA, would be less toxic than a lipid emulsion based on soybean oil, and that the addition of fish oil would be protective because of its anti-inflammatory properties.[4] A study which evaluated the hemodynamic changes and variations in pulmonary gas exchange that occurred in patients with ARDS given an intravenous lipid emulsion enriched with n-3 fatty acids could not show any benefit.[10] In unselected critically ill medical patients, fish oil supplementation that increased the n-3/n-6 PUFA ratio to 1:2 did not affect inflammation or clinical outcome, compared to parenteral lipid nutrition with an MCT/LCT emulsion.[11] A small study showed that while the LCT emulsion induced no deleterious effects on oxygenation in ARDS patients, the LCT/MCT emulsion improved the PaO2/FiO2 ratio and had a further beneficial effect on oxygen delivery.[12] The present study evaluated the effects of an intravenous lipid emulsion enriched with n-3 fatty acids in ventilated patients with acute lung injury.

Materials and Methods

This single-center, placebo-controlled, investigator blind, prospective, randomized clinical trial was approved by the institutional ethics committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their next of kin.

All patients admitted to the medical ICU of this hospital between July 1 and December 31 2009 were screened for eligibility. We studied 86 consecutive patients with suspected ARDS in the first 48 hours of admission .The inclusion criteria were: Bilateral pulmonary infiltrates of sudden onset in the chest radiograph, PaO2/FiO2 less than 200, and pulmonary capillary pressure less than 18 mm Hg.[13] Patients were excluded for age younger than 18 or older than 80 years, pregnancy, liver failure (bilirubin > 3), HIV positivity, leukopenia (<3500 mm3), thrombocytopenia (<100,000 mm3), acute bleeding, severe renal insufficiency (creatinine >2.5 mg/dl) or need for renal dialysis, signs of heart failure, transplantation, multiple blood transfusions, participation in other clinical trials simultaneously or in the last 60 days, treatment with nitrous oxide or corticoids (prednisolone 2 mg/kg/d or equivalent), multiple organ failure, severe dyslipidemia, propofol treatment, head injury, cerebral hemorrhage, receiving immunosuppressive regimen, radiation, allergy to any of the constituents of nutritional products.

Patients were divided into two groups:

Group 1: Standard diet (high fat, low carbohydrate kitchen feed)

Group 2: Standard diet + parenteral Omega 3 fatty acids, Omegaven® (Fresenius Kabi), an emulsion of 10% fish oil, for 14 days. This resulted in an n-3/n-6 ratio of 1:2 in the intervention group.

Patients in each stratum were assigned to the intervention or control group by the institutional intensivists, by use of a computer-generated block randomization list inaccessible to the investigators.

All participants were started on enteral feeding through a nasogastric tube within 24 hrs of ICU admission. Enteral feeding was administered continuously, and the daily enteral intake was recorded. Conventional modes of ventilation were used in all cases, including assist control ventilation (pressure mode), pressure support ventilation (Evita 4, Drager, Lubeck, Germany). The main goals of mechanical ventilation were an oxygen saturation of ≥90%, peak airway pressure of ≤35 cm H2O, and tidal volume of ≤6 mL/kg. Levels of PEEP and FIO2 were adjusted to achieve these goals. Ventilation settings and decisions regarding readiness for extubation were left to the discretion of the investigators who were blinded to the nutritional prescription.

Following data were collected:

Demographic data: Age, sex, weight, height, body mass index (BMI), and diagnostic category for ICU admission (medical, surgical, trauma)

Assessment of oxygenation and respiratory function: ABG at baseline, 4, 7, and 14 days or discharge from ICU. Ventilatory settings, TV , PEEP were also recorded simultaneously

Assessment of metabolic and nutritional variables: Harris Benedict equation was used to calculate the predicted energy expenditure according to anthropometric variables. Albumin levels were assessed at baseline and on days 4, 7, and 14.

Since the study medication was approved for therapeutic use, additional parameters of drug safety were not analyzed as outcome measures. As inhibition of platelet function is an established possible side effect of fish oil, the total quantity of transfused packed red cells/platelets, and bleeding events were recorded.

Primary outcome measures included changes in oxygenation and breathing patterns assessed at days 4, 7, and 14.

Secondary outcomes included length of ventilation, length of ICU stay, length of hospital stay, and in hospital mortality.

Data will be presented as mean, standard deviation, median values, and mode as appropriate.

Demographic data were compared across with standard t tests or one way analysis of variance for all continuous variables. All P values were two sided, significance was assigned at a threshold of 0.05. A t test was used to compare a continuous variable (e.g., PaO2/FiO2 ratio, length of stay). A contingency table (Fishers or chi-square test) was used to compare a categorical variable (e.g., survivor vs. nonsurvivors). Survival was evaluated with the Kaplan–Meir curve.

Results

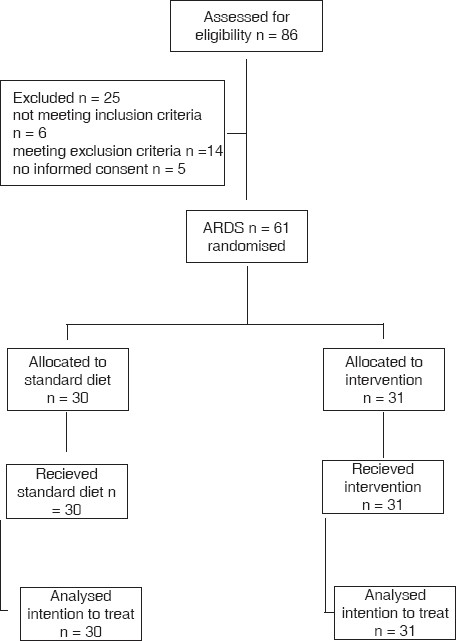

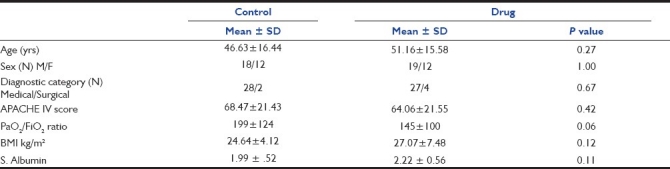

Of the 86 patients screened, 61 were enrolled [Figure 1]. Of the remainder, 30 patients received the standard diet and 31 patients received the drug in addition to standard diet. Baseline data were not significantly different [Table 1]. PaO2/FiO2 ratio was better in the control group to start with but still not significantly different from the drug group. BMI was nearly in the ideal range for both groups. Albumin levels were low at baseline and did not correlate with patient response over time, reinforcing the poor diagnostic and prognostic value of albumin in critical care illness.

Figure 1.

Consort diagram showing conduct of the study

Table 1.

Baseline patient values

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measures

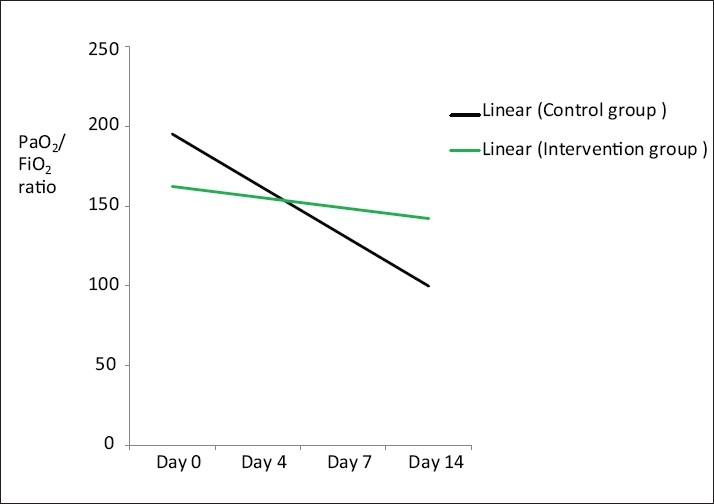

Oxygenation shown in Table 2 was no different in the two groups at days 4, 7, or 14. However ,the observed fall in PaO2/FiO2 ratio in the control group from baseline to day 14 was significantly higher as compared to the drug group (199 to 95 vs. 145 to 128, P = 0.0004) [Figure 2].

Table 2.

Gas exchange values (PaO2/FiO2 Ratio)

Figure 2.

Trend line showing significant difference (P < 0.0004) in oxygenation (PaO2/FiO2 ratio) between the intervention and control group at day 14.

Secondary outcome measures

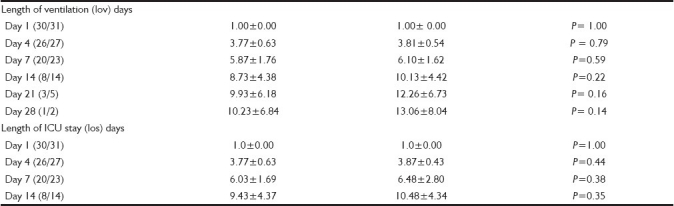

LOV and LOS, Table 3, was no different between the two groups.

Table 3.

Outcome variables

Survivors were more in the drug group (24 vs. 17) at 28 days; Table 4. At 28 days; LOV and LOS were same in the two groups, both for survivors and non survivors.

Table 4.

Outcome variables at 28 days

Overall survival was better in the drug group (22 vs. 16) Table 5. Length of hospital stay was shorter in the survivors group that received the drug compared to the survivors in the control group (21.5 ± 13.49 vs. 26.63 ± 18.22) but not statistically significant (P = 0.32).

Table 5.

Outcome variables for hospital stay

Discussion

In our opinion, this is the first study to examine the impact of parenteral Omega 3 fatty acids on ventilatory parameters and clinical outcome of ARDS patients who were otherwise fed enterally. Supplementation of enteral nutrition with fish oil for 14 days could not be proven to affect the examined ventilatory parameters or measures of clinical outcome in these patients. Only a significant increase in oxygenation could be shown at day 14. The hypothesis had been that inflammatory and subsequent anti-inflammatory reactions would be reduced,[14,15] resulting in clinical benefit. This expectation had been based on results of clinical studies.[16–19] The majority of such studies showing a benefit from intravenous supplementation of fish oil had been performed in surgical patients.

There may be several reasons why the expected effects of fish oil supplementation could not be demonstrated in this study. First, control patients were more severely ill in terms of PaO2/FiO2 ratio though the APACHE scoring was comparable. Second, the choice of lipids for standard care could partially explain why fish oil supplementation was not efficacious. In most clinical studies showing a benefit for fish oil, pure LCT lipids had been used in the control groups. LCT lipids, however, have been demonstrated to exert inflammatory and immunosuppressive influence on septic patients.[20] Parenteral Omega 3 fatty acids have been shown to improve glucose control and decrease inflammatory markers in COAD and after major surgery patients.[21,22] In the present study, standard diet containing 50% MCT and 50% LCT was used, which reduced the average daily dose of linoleic acid to less than 0.3 g/kg. Thus, the expected effects of modifying the LCT/MCT ratio may not have been detected because the standard nutrition itself had fewer immunological side effects. Third, the route of use and specific composition of n-3 PUFAs could be important for their immunomodulatory effect. Enteral application of a mixture of fish oil, canola and borage oil, which – in contrast to fish oil alone – contains a substantial amount of gamma-linolenic acid, has shown to improve outcome parameters in acute lung injury[6] and acute respiratory distress syndrome.[5] It may also be that this PUFA composition and its enteral application carry more benefit than the parenteral application of fish oil.

Adverse events

Considering their mechanism of action, one could logically expect two principal side effects of n-3-PUFAs: Impaired hemostasis (due to reduced synthesis of thromboxane) and reduced immune function. Bleeding events did not occur more frequently in the intervention group. The anti-inflammatory potential of fish oil may be harmful. No influence of fish oil supplementation on nutritional status, as assessed by weight and albumin (data not shown), was observed. In effect, the present study produced no evidence that fish oil supplementation is harmful for the critically ill.

Limitations

Some limitations of the present study merit consideration. Sample-size estimates were based on data from a previous study in a less heterogeneous population. To compensate for greater variability, much larger sample sizes could well have been necessary to detect an effect of fish oil supplementation. The dose of fish oil may have been insufficient to produce an immunomodulatory effect. However, the intervention in this study was aimed at altering the n-3/n-6 PUFA ratio to 1:2. This aim was generally achieved with a daily fish oil dose of 0.1 g/kg. Favorable effect of fish oil have been demonstrated with daily doses as low as 0.1–0.2 g/kg (17).

Conclusions

In comparison to standard enteral nutrition, supplementation with parenteral fish oil did not change parameters of ventilation or clinical outcome in selected ARDS patients.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1301–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brower RG, Lanken PN, MacIntyre N, Matthay MA, Morris A, Ancukiewicz M, et al. Higher versus lower positive end-expiratory pressures in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:327–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halliwell B, Chiricos S. Lipid peroxidation: Its mechanism, measurement and significance. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;57(5 Suppl):715S–24S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/57.5.715S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calder PC. Long-chain n-3 fatty acids and inflammation: Potential application in surgical and trauma patients. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2003;36:433–46. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2003000400004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gadek JE, DeMichele SJ, Karlstad MD, Pacht ER, Donahoe M, Albertson TE, et al. Effect of enteral feeding with eicosapentaenoic acid, gamma-linolenic acid, and antioxidants in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: Enteral Nutrition in ARDS Study Group. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1409–20. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199908000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singer P, Theilla M, Fisher H, Gibstein L, Grozovski E, Cohen J. Benefit of an enteral diet enriched with eicosapentaenoic acid and gamma-linolenic in ventilated patients with acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1033–8. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000206111.23629.0A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mathru M, Dries DJ, Zecca A, Fareed J, Rooney MW, Rao TL. Effect of fast vs slow intralipid infusion on gas exchange, pulmonary hemodynamics, and prostaglandin metabolism. Chest. 1991;99:426–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.99.2.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hwang TL, Huang SL, Chen MF. Effects of intravenous fat emulsion on respiratory failure. Chest. 1990;97:934–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.97.4.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beale RJ, Bryg DJ, Bihari DJ. Immunonutrition in the critically ill: A systematic review of clinical outcome. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:2799–805. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199912000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sabater J, Masclans JR, Sacanell J, Chacon P, Sabin P, Planas M. Effects on hemodynamics and gas exchange of omega-3 fatty acid-enriched lipid emulsion in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): A prospective, randomized, double-blind, parallel group study. Lipids Health Dis. 2008;7:39. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-7-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friesecke S, Lotze C, Köhler J, Heinrich A, Felix SB, Abel P. Fish oil supplementation in the parenteral nutrition of critically ill medical patients: A randomized controlled trial. Intensive Care Medicine. 2008;34:1411–20. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faucher M, Bregeon F, Gainnier M, Thirion X, Auffray JP, Papazian L. Cardiopulmonary effects of Lipid Emulsions in Patients with ARDS. Chest. 2003;124:285–91. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.1.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, Carlet J, Falke K, Hudson L, et al. The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS: Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:818–24. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.7509706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wendel M, Paul R, Heller AR. Lipoproteins in inflammation and sepsis.II: Clinical aspects. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:25–35. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0433-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayer K, Schaefer MB, Seeger W. Fish oil in the critically ill: From experimental to clinical data. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2006;9:140–8. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000214573.75062.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wichmann MW, Thul P, Czarnetzki HD, Morlion BJ, Kemen M, Jauch KW. Evaluation of clinical safety and beneficial effects of fish oil containing lipid emulsion (Lipoplus, MLF541): Data from a prospective, randomized, multicenter trial. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:700–6. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000257465.60287.AC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heller AR, Rossler S, Litz RJ, Stehr SN, Heller SC, Koch R, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids improve the diagnosis-related clinical outcome. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:972–9. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000206309.83570.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berger MM, Chiolero RL, Tappy L, Revelly JP, Geppert J, Franke C, et al. Safety of fish oil containing parenteral nutrition after abdominal aorta aneurysm surgery. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:S32. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsekos E, Reuter C, Stehle P, Boeden G. Perioperative administration of parenteral fish oil supplements in a routine clinical setting improves patient outcome after major abdominal surgery. Clin Nutr. 2004;23:325–30. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2003.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayer K, Fegbeutel C, Hattar K, Sibelius U, Kramer HJ, Heuer KU, et al. Omega-3 vs.omega-6 lipid emulsions exert differential influence on neutrophils in septic shock patients: Impact on plasma fatty acids and lipid mediator generation. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:1472–81. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1900-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsuyama W, Mitsuyama H, Watanabe M, Oonakahara K, Higashimoto I, Osame M, et al. Effects of Omega – 3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in COAD. Chest. 2005;128:3817–27. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.6.3817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wendel M. Impact of TPN including omega 3 fatty acids after major surgery. e-SPEN. 2007;2:e103–1. [Google Scholar]