Abstract

Introduction:

Menthol cigarette smokers may find it harder to quit smoking than smokers of nonmenthol cigarettes.

Methods:

We conducted a systematic review of published studies examining the association between menthol cigarette smoking and cessation. Electronic databases and reference lists were searched to identify studies published through May 2010, and results were tabulated.

Results:

Ten studies were located that reported cessation outcomes for menthol and nonmenthol smokers. Half of the studies found evidence that menthol smoking is associated with lower odds of cessation, while the other half found no such effects. The pattern of results in these studies suggest that the association between smoking menthol cigarettes and difficulty quitting is stronger in (a) racial/ethnic minority populations, (b) younger smokers, and (c) studies carried out after1999. This pattern is consistent with an effect that relies on menthol to facilitate increased nicotine intake from fewer cigarettes where economic pressure restricts the number of cigarettes smokers can afford to purchase.

Conclusions:

There is growing evidence that certain subgroups of smokers find it harder to quit menthol versus nonmenthol cigarettes. There is a need for additional research, and particularly for studies including adequately powered and diverse samples of menthol and nonmenthol smokers, with reliable measurement of cigarette brands, socioeconomic status, and biomarkers of nicotine intake.

Introduction

In 2009, the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act was enacted, giving the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) the authority to regulate tobacco products. One of its early interventions was to ban the addition of candy and fruit flavors to cigarettes. Menthol, the most common characterizing flavor additive in cigarettes, was not banned. Instead, the FDA Tobacco Products Scientific Committee has indicated that it will review the evidence on the public health impact of menthol as an additive to cigarettes before making a policy recommendation on this issue.

Menthol is a compound extracted from mint oils or produced synthetically (Ahijevych & Garrett, 2004; Kluger, 1996) that activates cold-sensitive neurons in the mammalian nervous system (Reid, Babes, & Pluteanu, 2002). Due to its cooling and counterirritant properties, it is used in a variety of products as an anesthetic (e.g., applied topically to relieve aches and pains), cooling agent (e.g., medication to treat sunburns), or to sooth minor throat irritation (e.g., cough medicine). Menthol is added to some cigarette brands to produce a characteristic menthol taste (“Menthol” cigarettes), and these menthol brands are marketed as such to consumers. “NonMenthol” or “Regular” cigarettes, even if they contain menthol in low quantities, are not characterized by or branded with emphasis on their menthol content (Wayne & Connolly, 2004). From 1990 through 2005, menthol cigarettes accounted for 25%–27% of the domestic U.S. cigarette market (Federal Trade Commission, 2007), and in recent years, menthols have become the preferred type of cigarette among almost half of 12- to 17-year-old cigarette smokers (48% in 2008, Office of Applied Studies, 2009).

For most smokers, successfully quitting smoking is a major challenge, largely because smokers become addicted to the psychoactive effects of nicotine delivered by cigarettes. It has been suggested that the cooling properties of menthol may facilitate greater smoke (and therefore nicotine) inhalation and potentially create even greater difficulty for smokers attempting to quit.

One particular challenge in reviewing this issue stems from evidence that use of menthol cigarettes is not evenly spread across the population of smokers in the United States. For example, 83% of African American cigarette smokers smoke menthol cigarettes, compared to 24% of non-Hispanic white smokers (Office of Applied Studies, 2009). Menthol cigarettes are also used more frequently by female, younger, and low-income smokers (Office of Applied Studies, 2009). Analysis of the effects of menthol on smoking cessation, therefore, should take into account likely differences between menthol and nonmenthol smokers and might investigate how menthol effects differ in different subgroups. This paper aims to summarize and review the cumulative evidence from studies that have assessed whether smokers of mentholated cigarettes find it harder to quit smoking than smokers of regular (nonmenthol) cigarettes.

Methods

We identified relevant studies by conducting a Pubmed search using the keywords, “menthol” AND “smoking” AND “cessation”, by reviewing an online bibliography prepared by the U.S. National Cancer Institute in 2009, that included 343 peer-reviewed research articles related to menthol cigarette smoking (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2009), by reviewing Web sites of relevant scientific organizations and by reviewing the reference sections of relevant papers. We identified all studies that directly compared smoking cessation rates or proportions between smokers of menthol cigarettes and smokers of regular cigarettes. Each identified study was reviewed by at least two authors, and where available, key descriptive and outcome data from each study were extracted and coded in tabular form. The aim of this narrative review was to reach conclusions based on analysis of the pattern of methods and results across differing studies. Quantitative pooling of results was not feasible given the heterogeneity of study designs and methods.

Results

We identified 10 studies that compared smoking cessation rates or proportions between mentholated and regular cigarette smokers. The key descriptive and outcome data from each identified study is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main Characteristics and Findings of Published Studies Comparing Smoking Cessation Outcomes in Menthol and Nonmenthol Cigarette Smokers

| Author (publication year)/study years | Location | N M/NM | N—W/AA/Hisp/Other | Cigarettes/day (M/NM) | Design | Intervention? | Definition (of a quitter) | Evidence of M effect? | Comments |

| Fu et al. (2008)/2006 | United States—VA pharmacy databases | Total = 1,343 M = 342 (25%)/NM = 1,001 (75%) M age = 56 (10.3) | All smokers: Caucasian: 76% AA: 14% Other: 10% | Total: 25 M: 20 NM: 30 | Cross-sectional analysis at end of interventional trial | Intervention aimed to stimulate repeat quit attempts All participants had previously failed using NRT or bupropion |

Seven-day point prevalence, self-reported | No overall effect of M on abstinence. Some evidence of increased quitting among menthol smokers, restricted to intervention group, with lower menthol quitting in controls. | Older sample. One significant interaction between menthol status and treatment group only, not significant after Bonferroni correction |

| Gundersen et al. (2009)/2005 | USA representative sample of smokers (National Health Interview Survey) | Total = 7,815 M = 2,133 (27%)/NM = 5682 (73%) M age = 49 (0.23) | White: 6007 (21% M) AA: 891 (70% M) H: 917 (26% M) | 1–10 = 45.6% 11–20 = 37.6% >20 = 16.8% | Cross-sectional survey. Analysis on smokers who had tried to quit | None | Ever-smoker (>100 lifetime cigs.) who is no longer a smoker | Yes, but different for whites (M > quitting) and non-Whites (M < quitting). Adj. OR for non-Whites = 0.55 (0.43–0.710) | The quit attempt could have been anytime in the past. |

| Cropsey et al. (2009)/2004–2006 | Women’s prison in Virginia | N=233 M=159 NM=74 M age = 34 | W = 109 (49% M) AA = 124 (95% M) (all female) | W = 20 AA = 14 | Retrospective analysis of trial cohort. | Randomized trial of NRT plus group, versus wait list control | Seven-day point prevalence by self-report (and exhaled CO < 3 ppm) at 6 weeks and 12 months. | No effect of menthol | Relatively small sample of incarcerated women (only six AA nonmenthol smokers) |

| Gandhi et al. (2009)/2001–2005 | Outpatient Smokers’ Clinic Central New Jersey | Total = 1688 M = 778 (46%) /NM = 910 (54%) M age = 42 (13.3) | 1086/374/149/79 64%/22%/9%/5% | Total sample: 21 M: 19 NM: 23 | Clinic cohort, followed up at 4 weeks and 6 months. | Tailored Smoking cessation treatment with meds and counseling | Self-report of not smoking in previous 7 days at 4 weeks and 6 -month follow-up. Biochemical verification in those attending at 4 weeks. | Yes, but restricted to non-whites. Also related to SES. For AAs at 6 months, Adj. OR = 0.48 (0.25–0.9) | Cigarettes/day lower in AA and H menthol smokers. Follow-up rate= 74% at 4 weeks and 58% at 6 months. |

| Okuyemi et al. (2007)/2003–2004 | Kansas | 755 light smokers (<11 cigarettes/day) M age = 45.1 (SD = 10.7) | 0/755/0/0 | M: 7.5 NM: 7.8 | Clinical trial cohort followed up at 6m. | Nicotine gum × motivational interviewing trial (factorial) | Seven-day point prevalence, verified by CO/salivary cotinine at 6-month follow-up | Yes, unadjusted: 11.2% vs. 18.8% | M not significant in fully adjusted model (overadjusted by using number ofappointments attended?) (Nollen et al. 2006); M effect stronger in age < 50 |

| Okuyemi et al. (2003)/1999–2000 | Kansas | 600 smokers (471/129) M age = 44 | 0/600/0/0 | M: 18 NM: 18 | Clinical trial cohort followed up at 6m. | Bupropion versus placebo randomized controlled trial | Seven-day point prevalence, verified by CO/salivary cotinine | Yes, in subgroup. At 6 weeks in age < 50: OR (NM) 2.02 (1.03–3.95) | No significant effect at 6 months or in age > 50 |

| Murray et al. (2007)/1986–2001 | United States | Total = 5,883 M = 1,216 (21%)/NM = 4,671 (79%) M age = 48.4 (SD = 6.8) | White:95.2% AA: 3.8% H: 0.6% | Overall average 26 cigarettes/day Pack-years: M: 38.18 NM: 40.1 |

Clinical trial cohort followed up 5 and 14 years after enrollment | 12-week group intervention plus nicotine gum (repeatable for 5 years) or usual care | Smoking at all in past 12 months | Three categories: sustained quitter, intermittent smoker, continuing smokers; no menthol effect | Only 114 AA menthol smokers in the study. |

| Pletcher et al. (2006)/1985–2000 | Birmingham, Chicago, Minneapolis, and Oakland | 1535 smokers (972/563) M age= 25.1 (3.6) | 657/878/0/0 | M: 10 NM: 15 | Prospective cohort study | No |

Sustained cessation: not current smoker at last 2 visits Relapse: smoker → nonsmoke → smoker at last exam |

Yes Sustained cessation: Adj. OR = 0.71(0.49-1.02) Relapse: Adj. OR = 1.89 (1.17–3.05) |

Long-term study, not in context of a quit attempt |

| Muscat et al. (2002)/1981–1999 | Hospitals in New York, Washington DC, and Pennsylvania | Total = 19545 NM = 16540 (85%)M = 3005 (11%) 56%–72% aged > 54 | W = 17,637 (89%) AA = 1906 (11%) | W: NM = 29 M = 28 AA NM = 21 M = 18 |

Cross-sectional case-control study based on convenience sample of cases (lung cancer) and controls (other medical patients) | No intervention | Ever smoked daily for a year and not smoked daily in past year. | No effect on quitting OR = 1.1 |

Older and relatively affluent sample, with unusually low menthol rate in AAs (34%). Definition of abstinence relatively lenient. Possible effect of illness on quitting. |

| Hyland et al. (2002)/1988–1993 | 22 communities in North America |

N = 13,268 (age 25–64) M = 3,184 (24%)/NM = 10,084 (76%) 23% Whites smoke M, 57% AAs smoke M. 51% ages < 45 |

All smokers: Caucasian: 10,004 (75%) AA: 878 (7%) Hispanic: 693 (5%)Other: 294 (2%) Canadian: 1,382 (10%) |

Total sample: 23.2/day | Prospective population cohort survey, followed up after 5 years. | Randomized community intervention trial | Self-report of no cigarette use in past 6 months at 5-year follow-up. | No. (e.g., adjusted RR for quitting by AA menthol smokers = 1.04.) | M smokers more likely to have 2+ prior quit attempts. No data on whether participants triedto quit. |

Note. M = menthol; NM = nonmenthol; OR= odds ratio; RR= relative risk; adj. = adjusted for other baseline variables; CO = exhaled carbon monoxide concentration; AA= African American; W = white (non-Hispanic); H = Hispanic/Latino; M age = mean age of sample; SES = Socioeconomic status; NRT = Nicotine Replacement Therapy.

Overall, the results of these studies were mixed, with 5/10 studies finding evidence of lower quit rates among menthol smokers and 5/10 finding no evidence of differential quit rates. None of the studies found a significant overall effect of menthol on smoking cessation at the last study follow-up point, after controlling for other relevant measured variables.

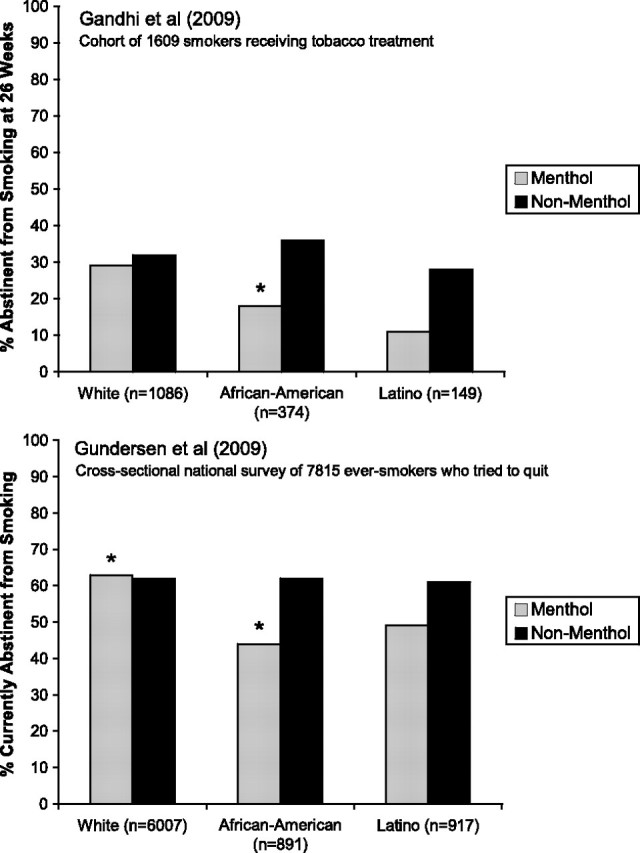

None of the studies found a significant negative effect of menthol cigarettes on smoking cessation in non-Hispanic white smokers and one (Gundersen, Delnevo, & Wackowski, 2009) found evidence of a higher quit rate among white menthol smokers. In all four of the studies that found a direct negative association between menthol cigarettes and quitting (Gandhi, Foulds, Steinberg, Lu, & Williams, 2009; Gundersen et al., 2009; Okuyemi et al., 2003; Okuyemi, Faseru, Cox Sanderson, Bronars, & Ahluwalia, 2007), the significant effects were confined to non-White (primarily African American) subsamples of the population. In the other study (Pletcher et al., 2006), the main significant effect was on relapse rates after achieving abstinence (higher relapse rate among menthol smokers), rather than on abstinence per se. The two studies by Okuyemi and colleagues focused exclusively on African American smokers, and in both, the menthol effect was stronger in younger (under age 50) smokers. The studies by Gandhi, Foulds, Steinberg, Lu, & Williams (2009) and Gundersen et al. (2009), however, both analyzed effects on Non–Latino-Whites, African Americans and Latinos. Although these studies were based in entirely different contexts (Gandhi et al. [2009] was based in a treatment-seeking clinic population in New Jersey; Gundersen et al. [2009] studied a representative national sample of smokers who had ever tried to quit), they found a remarkably similar pattern of results, as shown in Figure 1 below. Gandhi et al. (2009) found significantly lower adjusted quit rates among Latino and African American menthol smokers relative to nonmenthol smokers at the 4-week follow-up, and this effect remained significant for African American smokers at 6 months, whereas there was no overall quitting disadvantage for white menthol smokers (relative to white nonmenthol smokers). Gundersen et al. (2009) found a significantly lower adjusted quit rate for menthol smokers among racial/ethnic minorities (African Americans and Latinos collapsed into a single group), but a significant quitting advantage for white menthol smokers relative to white nonmenthol smokers.

Figure 1.

Percentage of smokers attempting to quit who achieve abstinence, by cigarette type and race/ethnicity in the Gandhi et al. (2009) and Gundersen et al. (2009) studies. “*” Indicates a significant difference in abstinence rate between menthol and nonmenthol smokers within race/ethnicity grouping after adjusting for other variables.

All four of the studies finding an association between menthol and lower quit rates were carried out since 1999 (Gandhi et al., 2009; Gundersen et al., 2009; Okuyemi et al., 2003, 2007), whereas the three large studies finding no menthol effects collected data in the 1980s (Hyland, Garten, & Giovino, 2002; Murray, Connett, Skeans, & Tashkin, 2007; Muscat, Richie, & Stellman, 2002).

Discussion

The pattern of results from studies examining the association between mentholated cigarette smoking and smoking cessation is mixed. However, there does appear to be broadly consistent evidence that menthol smoking is more prevalent in racial/ethnic minority populations and that menthol smokers tend to smoke fewer cigarettes per day than regular cigarette smokers (e.g., Giovino et al., 2004 and most studies in Table 1). There are also trends suggesting that the association between smoking menthol cigarettes and greater difficulty quitting is stronger in (a) racial/ethnic minority populations, (b) younger smokers, and (c) after the year 1999, as opposed to the 1980s.

One possibility, consistent with this pattern of results, is that the effect of menthol on quitting smoking is only apparent in circumstances where the smoker has been forced to reduce their cigarette consumption, with the most obvious influence being socioeconomic factors. The price of cigarettes has increased in many parts of the United States since the 1990s. Young smokers, and racial/ethnic minority smokers tend to be less affluent and are thus more affected by the increased prices, forcing them to consume fewer cigarettes per day (as is found in most studies in these groups). One possible mechanism explaining the menthol effect is that these smokers may increase their total nicotine intake per cigarette to obtain their preferred dose of nicotine from fewer cigarettes. The menthol effect on cessation may stem from the cooling effects of menthol facilitating such “compensatory” smoking and allowing these smokers to obtain a larger and perhaps more reinforcing nicotine “hit” per cigarette. There is some evidence that smokers of menthol cigarettes tend to obtain higher levels of carbon monoxide (CO), nicotine, and cotinine per cigarette smoked (Clark, Gautam, & Gerson, 1996; Ahijevych & Parsley, 1999; Benowitz, Herrera, & Jacob, 2004; Perez-Stable, Herrera, Jacob, & Benowitz, 1998; Williams et al., 2007). Gandhi et al. (2009) reported that the association between menthol smoking and lower quit rates was stronger among unemployed than full-time employed smokers, regardless of race/ethnicity, which is consistent with the model proposed above.

Adolescent smokers are a group that could be particularly sensitive to the menthol effect mechanism being proposed here as their cigarette consumption is often restricted by parental/school/legal rules as well as by financial constraints. There are no studies comparing quit rates between adolescent menthol and nonmenthol smokers. However national surveys of adolescent smokers that included indirect measures of dependence have consistently found that menthol smokers, compared to nonmenthol smokers, are significantly more likely to smoke within an hour of waking and that menthol smokers are more likely than nonmenthol smokers to experience cravings after not smoking for a few hours (Hersey et al., 2006; Wackowski & Delnevo, 2007).

Ahijevych, Weed, and Clarke (2004) conducted an experimental test of the theory that menthol enables smokers to inhale more nicotine per cigarette when forced to reduce daily cigarette consumption. This study examined smoking behavior in 25 women (13 African American) while they resided at a research center for 6 days and were given access to either: (a) their usual number of cigarettes, (b) cigarettes restricted to 50% of normal, or (c) 167% of their normal consumption. In this study, all 13 of the African American women smoked menthols, as did a third of the white women. There were significantly higher percentage increases in exhaled CO levels among menthol smokers compared to nonmenthol smokers in the increased and restricted conditions. Also, African American menthol smokers had significantly higher percentage increases in exhaled CO compared with white menthol smokers in the restricted condition. This study also identified “efficient smokers” by their high baseline cotinine/cigarette ratio and found that their nicotine intake per cigarette increased even more in the “restricted” condition. Specifically, the pre-post cigarette “boost” in blood nicotine went up from 32 to 47 ng/ml. The typical blood nicotine boost from smoking a cigarette is about 10–15 ng/ml (Foulds et al., 1992; Patterson et al., 2003). All but one of these “efficient” smokers were menthol smokers. The data from this study are consistent with the theory that menthol smokers increase their smoke (CO and nicotine) intake per cigarette more than nonmenthol smokers when access to cigarettes is restricted. It may be that the large rapid increases in blood nicotine concentration resulting from this more “efficient” style of smoking (blood nicotine boost of 47 ng/ml per cigarette in the the study by Ahijevych et al., 2004) produces more reinforcement per cigarette and consequently greater difficulty quitting.

This hypothetical model explaining how menthol may influence smoking cessation needs to be evaluated in further studies. If true, one might expect the putative menthol effect on cessation to become stronger over time as cigarette prices and smoking restrictions have increased dramatically since the beginning of the 21st century and when the United States is in a period of economic recession.

Other factors may also be involved. For example, there is evidence that menthol may itself inhibit nicotine metabolism, causing greater nicotine exposure per unit inhaled (Benowitz et al., 2004). In addition, the studies to date have mainly assumed that the only factor that differs between the brands being smoked is the mentholation. In reality, each cigarette sub-brand can vary on a number of additional dimensions, including filter ventilation, standardized machine-measured nicotine yield, and cigarette length. It has been noted that a very high proportion of African American smokers smoke specific brands (e.g., Newport) with little filter ventilation, and relatively high machine-measured nicotine yield, whereas whites tend to smoke ventilated low or medium machine-measured nicotine yield cigarettes such as Marlboro/Marlboro Lights (Melikian, Djordjevic, Chen, & Richie 2007; Okuyemi, Ebersole-Robinson, Nazir, & Ahluwalia, 2004). Rose and Behm (2010) recently presented the reanalyses of two clinical trials examining the association between abstinence, menthol preference, and various other variables. They found that among menthol smokers, preference for higher nicotine-yield cigarettes was strongly related to lower socioeconomic status and that this mediated the link between menthol smoking and low quit rates (6-month point abstinence among menthol smokers of high yield cigarettes = 11% as compared with 26% for high yield nonmenthol smokers, p = .005 when adjusting for other covariates). They also found significantly higher baseline cotinine per cigarette in menthol versus nonmenthol smokers.

Consistent with Rose and Behm’s (2010) findings, Farrelly, Loomis, and Mann (2007) found that over the years 1994–2004, U.S. inflation-adjusted cigarette prices increased by over 50%, and this was associated with increased consumption of higher machine-measured nicotine yield cigarettes, with this effect being larger for menthol versus nonmenthol cigarettes. This data, derived from analyses of over 800,000 cigarette purchases at U.S. supermarkets, is consistent with the idea that as cigarette prices increase, menthol cigarettes are particularly consumed in a manner that facilitates greater nicotine absorption per cigarette.

It should be noted that most of the studies to date have not been designed specifically to evaluate the effects of menthol on cessation, and even the relatively large studies (e.g., Hyland et al., 2002 and Murray et al., 2007) suffered from a lack of statistical power to detect within-race effects, partly because such a low proportion of African Americans smoke nonmenthol brands. Future analyses of existing and ongoing national survey datasets (e.g. National Health Interview Survey, National Health And Nutrition Examination Survey) may help clarify this issue. Where possible, such analyses should include an assessment of the effects of socioeconomic status (via measures of income, financial assets, employment status, and education), nicotine/smoke intake (e.g., via biomarkers such as CO and cotinine), and also indicators of cigarette price (which can be estimated from the person's home state and preferred brand). Future studies should collect adequate measurement of cigarette brand and sub-brand smoked (including whether it is a menthol brand), brand switching, the socioeconomic status of participants, and their biomarker concentrations. This is also true for clinical trials not necessarily designed to assess the effects of menthol on cessation.

In conclusion, research to date finds little evidence of an association between menthol cigarette smoking and increased difficulty quitting among middle-aged (and older) white smokers. However, recent studies have consistently found that racial/ethnic minority smokers of menthol cigarettes have a lower quit rate than comparable smokers of regular cigarettes, particularly among younger smokers. This pattern of results is consistent with an effect that relies on menthol to facilitate increased nicotine intake from fewer cigarettes where economic pressures restrict the number of cigarettes smokers can afford to purchase.

Funding

No specific funding was provided for this paper, but the authors were recently supported as follows: JF was supported by grants from New Jersey Department of Health & Senior Services and Rutgers Community Health Foundation; MJP was supported by a grant to the Kaiser Foundation Research Institute, N01-HC-48050, from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and MWH was supported by grants from the American Cancer Society and the Florida Department of Health.

Declaration of Interests

J.F. has worked as a consultant for pharmaceutical companies involved in the manufacture of smoking cessation products (Pfizer, GSK, Novartis).

References

- Ahijevych K, Garrett BE. Menthol pharmacology and its potential impact on smoking behavior. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6(Suppl_1):S17–S28. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001649469. doi:10.1080/14622200310001649469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahijevych K, Parsley LA. Smoke constituent exposure and stage of change in Black and White women cigarette smokers. Addictive Behaviors. 1999;24:115–120. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00031-8. doi:10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahijevych K, Weed H, Clarke J. Levels of cigarette availability and exposure in Black and White women and efficient smokers. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior. 2004;77:685–693. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.01.016. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2004.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL, Herrera B, Jacob P., III Mentholated cigarette smoking inhibits nicotine metabolism. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2004;310:1208–1215. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.066902. doi:10.1124/jpet.104.066902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark PI, Gautam S, Gerson LW. Effect of menthol cigarettes on biochemical markers of smoke exposure among black and white smokers. Chest. 1996;110:1194–1198. doi: 10.1378/chest.110.5.1194. doi:10.1378/chest.110.5.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cropsey KL, Weaver MF, Eldridge GD, Villaobos GC, Best AM, Stitzer ML. Differential success rates in racial groups: Results of a clinical trial of smoking cessation among female prisoners. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009;11:690–697. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp051. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntp051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrelly MC, Loomis BR, Mann NH. Do increases in cigarette prices lead to increases in sales of cigarettes with high tar and nicotine yields? Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9:1015–1020. doi: 10.1080/14622200701491289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Trade Commission. Federal Trade Commission Cigarette Report for 2004 and 2005. 2007. Retrieved May 14, 2010, from http://www.ftc.gov/reports/tobacco/2007cigarette2004-2005.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Foulds J, Stapleton J, Feyerabend C, Vesey C, Jarvis M, Russell MAH. Effect of transdermal nicotine patches on cigarette smoking: A double blind crossover study. Psychopharmacology. 1992;106:421–427. doi: 10.1007/BF02245429. doi:10.1007/BF02245429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu SS, Okuyemi KS, Partin MR, Ahluwalia JS, Nelson DB, Clothier BA, et al. Menthol cigarettes and smoking cessation during an aided quit attempt. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2008;10:457–462. doi: 10.1080/14622200801901914. doi:10.1080/14622200801901914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi KK, Foulds J, Steinberg MB, Lu SE, Williams JM. Lower quit rates among African American and Latino menthol smokers at a tobacco treatment clinic. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2009;63:360–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01969.x. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovino GA, Sidney S, Gfroerer JC, O’Malley PM, Allen JA, Richter PA, Cummings KM. Epidemiology of menthol cigarette use. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6(Suppl. 1):S67–S81. doi: 10.1080/14622203710001649696. doi:10.1080/14622203710001649696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen DA, Delnevo CD, Wackowski O. Exploring the relationship between race/ethnicity, menthol smoking, and cessation in a nationally representative sample of adults. Preventive Medicine. 2009;49:553–557. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.10.003. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersey JC, Ng SW, Nonnemaker JM, Mowery PM, Thomas KY, Vilsaint MC, Allen JA, Haviland ML. Are menthol cigarettes a starter product for youth? Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2006;8:403–413. doi: 10.1080/14622200600670389. doi:10.1080/14622200600670389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland A, Garten S, Giovino GA. Mentholated cigarettes and smoking cessation: Findings from COMMIT. Tobacco Control. 2002;11:135–139. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.2.135. doi:10.1136/tc.11.2.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluger R. Ashes to ashes: America's hundred-year cigarette war, the public health, and the unabashed triumph of Philip Morris. New York: Knopf; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Melikian AA, Djordjevic MV, Chen S, Richie J. Effect of delivered dosage of cigarette smoke toxins on levels of urinary biomarkers of exposure. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention. 2007;16:1408–1415. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-1097. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray RP, Connett JE, Skeans MA, Tashkin DP. Menthol cigarettes and health risks in Lung Health Study data. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9:101–107. doi: 10.1080/14622200601078418. doi:10.1080/14622200601078418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muscat JE, Richie JP, Stellman SD. Mentholated cigarettes and smoking habits in whites and blacks. Tobacco Control. 2002;11:368–371. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.4.368. doi:10.1136/tc.11.4.368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nollen NL, Mayo MS, Sanderson , Cox L, Okuyemi KS, Choi WS, Kaur H, Ahluwalia JS. Predictors of quitting among African American light smokers enrolled in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21:590–595. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00404.x. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00404.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Applied Studies. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2009. Results from the 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National findings (DHHS Publication No. SMA 09-4434, NSDUH Series H-36) Retrieved May 19, 2010, from http://oas.samhsa.gov. [Google Scholar]

- Okuyemi KS, Ahluwalia JS, Ebersole-Robinson M, Catley D, Mayo MS, Resnicow K. Does menthol attenuate the effect of bupropion among African American smokers? Addiction. 2003;98:1387–1393. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00443.x. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuyemi KS, Ebersole-Robinson M, Nazir N, Ahluwalia JS. African-American menthol and nonmenthol smokers: Differences in smoking and cessation experiences. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2004;95:1208–1211. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuyemi KS, Faseru B, Cox Sanderson L, Bronars CA, Ahluwalia JS. Relationship between menthol cigarettes and smoking cessation among African American light smokers. Addiction. 2007;102:1979–1986. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02010.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson F, Benowitz N, Shields P, Kaufmann V, Jepson C, Wileyto P, et al. Individual differences in nicotine intake per cigarette. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2003;12:468–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Stable EJ, Herrera B, Jacob P, III, Benowitz NL. Nicotine metabolism and intake in Black and White smokers. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280:152–156. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pletcher MJ, Hulley BJ, Houston T, Kiefe CI, Benowitz N, Sidney S. Menthol cigarettes, smoking cessation, atherosclerosis, and pulmonary function. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166:1915–1922. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1915. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.17.1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid G, Babes A, Pluteanu F. A cold- and menthol-activated current in rat dorsal root ganglion neurones: Properties and role in cold transduction. Journal of Physiology. 2002;545:595–614. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.024331. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2002.024331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JE, Behm F. M. Menthol smokers, SES and quit smoking outcome. Paper presented at the 2010 Annual Meeting of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, Baltimore, MD, POS5–58, p.148. Retrieved from http://www.srnt.org/conferences/2010/pdf/2010_Program.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2009. Bibliography of literature on menthol and tobacco. Accessed online on May 19, 2010, retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/TobaccoProductsScientificAdvisoryCommittee/UCM204340.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Wayne FG, Connolly GN. Application, function, and effects of menthol in cigarettes: A survey of tobacco industry documents. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6:S43–S54. doi: 10.1080/14622203310001649513. doi:10.1080/14622203310001649513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wackowski O, Delnevo CD. Menthol cigarettes and indicators of tobacco dependence among adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:1964–1969. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.12.023. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JM, Gandhi KK, Steinberg ML, Foulds J, Ziedonis ZM, Benowitz NL. Higher nicotine and carbon monoxide levels in menthol smokers with and without schizophrenia. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9:873–881. doi: 10.1080/14622200701484995. doi:10.1080/14622200701484995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]