Abstract

Background

Individuals with hip or knee osteoarthritis (OA) are referred to orthopaedic surgeons if considered by their GP as potential candidates for total joint replacement (TJR). It is not clear which patients end up having this surgery.

Aim

The aim of the study was to investigate symptom variation in individuals with OA newly referred by GPs to an orthopaedic surgeon for consideration for TJR, and to determine the predictors of having this procedure.

Design and setting

A longitudinal study of patients at a regional orthopaedic centre with follow-up at 3, 6, and 12 months by postal questionnaire.

Method

GP referrals of patients with OA to orthopaedic surgeons were consecutively sampled. Of the 431 eligible patients, 257 (59.6%) were recruited. Validated measurement tools were used to measure pain, physical functioning, severity of OA, and health-related quality of life.

Results

Over half the participants were in constant pain, taking pain medication more than once per day. Only 67 of 134 (50%) hip and 40 of 123 (33%) knee patients had a TJR within 12 months. Those who had a replacement had been diagnosed with OAfora shorter time, reported more frequent pain, were more likely to use a walking stick, and had worse pain, stiffness, and physical functioning.

Conclusion

Many individuals considered for TJR ultimately may not have surgery, and more effective strategies of management need to be developed between primary and secondary care to achieve better outcomes and to improve quality of care.

Keywords: longitudinal survey, general practice, osteoarthritis, outcome assessment, referral and consultation, total hip replacement, total knee replacement

INTRODUCTION

Osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the most common musculoskeletal diseases in the UK and the main reason for undergoing total joint replacement (TJR). High levels of pain, reduced physical function, and poor quality of life are prevalent in individuals with OA.1-3

Joint replacement forsevere OA of the hip or knee is regarded as an effective treatment,4-6 and is one of the most common operations in the UK.7 GPs determine whether patients are potential candidates for TJR in their referral to orthopaedic surgeons.

A study of new attenders in primary care with hip pain found that pain and restriction of internal rotation of the hip are the major clinical predictors of being placed on the waiting list for total hip replacement (THR).8 The criteria as to why individuals are put on the waiting list forjoint replacement are not clear cut.9-11 The basis for the decision, whether it is radiological, clinical, or includes measuring pain levels and physical function, appears to vary between surgeons and hospitals.

Several studies have looked at the determinants of having TJR and found the worse the pain and disability, the higher the likelihood is of being placed on the waiting list,8 and that better general health and the patient's willingness to consider TJR increased the likelihood of undergoing TJR.12 Other predictors of THR due to OA that have been reported are: radiological grade, mean global patient assessment, and need for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.13 Studies have found that women are less likely to undergo TJR than men,14 and younger individuals with a full knee range of motion are less likely to undergo total knee replacement (TKR).15

There is little published research investigating the biomedical and psychosocial differences between patients who are referred in primary care by the GP and those who are considered candidates for a TJR. This study set out to investigate differences between individuals with OA newly referred to an orthopaedic surgeon for consideration for TJR; to identify differences in individuals who were put on the waiting list for TJR; and to identify the predictors of having a THR orTKR.

METHOD

Participants and sampling

This was a longitudinal study with data collected by postal questionnaire at baseline, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months. This paper reports on baseline and 12 month data. All new GP referral letters to 10 orthopaedic surgeons in a regional orthopaedic centre in the north west of England were read on a weekly basis, to identify individuals over 18 years of age with a confirmed diagnosis of OA who were considered potentially suitable for TJR. A patient-recruitment form was used to record patient information details and the reason for referral. Recruitment of participants took place from September 2006 to June 2007, with follow-up continuing until July 2008.

How this fits in

GPs play an important role in which patients are referred for consideration of total joint replacement (TJR). It is not clear which patients ultimately end up having a TJR. This UK longitudinal study demonstrates differences between patients who have and have not had TJR in terms of symptoms, management of osteoarthritis, and predictors of TJR.

The sample size was based on detecting a difference in the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) pain score between individuals with OA having and not having TJR. Previous research shows that the meanWOMAC pain score was 11.2 (standard deviation [SD] 3.5) in individuals undergoing surgery.16 A 12.5% better WOMAC pain score of 9.8 (SD 3.5) requires 100 per group of those having surgery and those not having surgery. Assuming 20% attrition at follow-up, a total sample size of 250 participants was required.

Measures

The WOMAC,17 a disease-specific measurement tool, was used to collect data about pain, stiffness, and physical functioning. To measure health-related quality of life, the Medical Outcomes Short-Form (SF-36) version 2 was used.18,19 The Oxford Hip Score and Oxford Knee Score were used to measure the severity of OA and for evaluating the outcome following surgery.20-23 All the measures have good reliability, validity, and responsiveness to detect change overtime.17-25

In this article, only data collected at baseline on pain, stiffness, and physical functioning have been used in the analysis. Items on the baseline questionnaire also collected demographic data. Information on medication; services and treatments for osteoarthritis; and consultation outcome, was collected at baseline and at each follow-up point.

Analysis

Data were entered into and analysed using SPSS (version 15). Data were summarised for the sample of baseline responders as a whole, and separately by surgical outcome for the sample of those successfully followed-up to 12 months using frequencies and percentages or means and SDs as appropriate. Differences between those subsequently having TJR surgery and those not having TJR surgery were tested using Pearson's χ2 test (or the Fisher-Freeman-Halton exact test) where necessary) for nominal variables, the χ2 test for trend for ordinal variables, the Mann-Whitney U test for skewed interval/ratio variables, and unpaired t-tests for interval/ratio variables with approximately normal distributions. The level of statistical significance used was α = 0.05.

Binary logistic regression was used to determine which baseline covariates were significantly associated with subsequently having a TJR, with hip patients and knee patients considered separately. Univariable logistic regression was used first to estimate unadjusted odds ratios for having TJR compared with not having TJR. Some of the categorical variables had to be recategorised due to small cell counts. Covariates with unadjusted odds ratios that were significant at a conservative P<0.25, to include predictors that may not have appeared to have been important in isolation,26 were considered in multivariable logistic regression. There was no evidence of multicollinearity in terms of statistical tolerance or condition indices estimated using multiple linear regression.27 Multivariable logistic regression with forwards stepwise selection of variables was then used to estimate adjusted odds ratios for highly discriminating variables, in an exploratory approach.

RESULTS

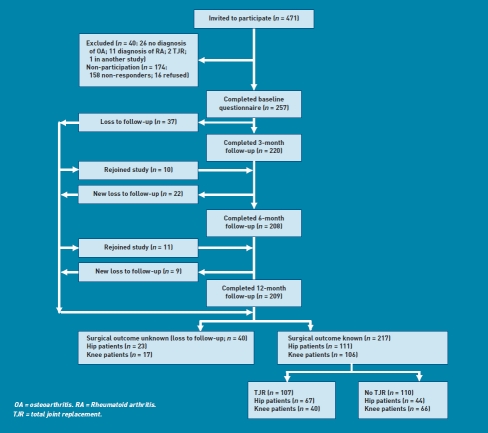

Of the 471 patients initially considered from referral letters (from 338 GPs), 40 were excluded as ineligible (Figure 1), including 11 with confirmed diagnoses or rheumatoid arthritis, leaving 431 eligible patients. Of these, 257 (59.6%) consented to take part in the study. The 174 non-responders were similar in terms of age (mean 64.7 years, SD 11.0 years), sex (female 54.6%), and type of OA (hip OA 53.4%, knee OA 46.6%) to those who participated in the study.

Figure 1.

Numbers of participants and non-participants during the study.

By follow-up at 12 months, there were 209 participants remaining (18.7% attrition) (Figure 1). Confirmed surgical outcomes were known for 217 of 257 patients (84.4%), with 107 having and 110 not having a joint replaced.

Just over half of the 257 participants who completed the baseline questionnaire had hip OA (52.1%) compared with knee OA (47.9%). Mean age was 65.1 years (range 35-88years), most were female (54.9%), and almost two-thirds (65.4%) had one or more comorbidities (Table 1). Comorbidities were more common among knee patients (74.0%) than hip patients (57.5%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants by surgical outcome for total joint replacement

|

n (%), unless otherwise specified |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample (n = 257) | TJR (n = 107) | No TJR (n = 110) | Loss to follow-up (n = 40) | P-value for TJR vs no TJR | |

| Type of osteoarthritis | 0.001 | ||||

| Hip | 134(52.1) | 67 (62.6) | 44 (40.0) | 23 (57.5) | |

| Knee | 123(47.9) | 40 (37.4) | 66 (60.0) | 17(42.5) | |

| Location of osteoarthritis | |||||

| Single hip | 64 (24.9) | 33 (30.8) | 23 (20.9) | 8 (20.0) | |

| Single knee | 57 (22.2) | 15(14.0) | 30 (27.3) | 12(30.0) | |

| Single hip and knee | 12(4.7) | 3 (2.8) | 5 (4.5) | 4(10.0) | |

| Both hips | 36(14.0) | 22 (20.6) | 9 (8.2) | 5(12.5) | |

| Both knees | 45(17.5) | 20(18.7) | 22 (20.0) | 1 (2.5) | |

| Both hips and knees | 20 (7.8) | 8(7.5) | 9 (8.2) | 3(7.5) | |

| Single hip and both knees | 14(5.4) | 4 (3.7) | 8(7.3) | 2(5.0) | |

| Single knee and both hips | 9 (3.5) | 2(1.9) | 4(3.6) | 3(7.5) | |

| Age | |||||

| All patients, mean (SD) years | 65.1 (SD10.2) | 64.6 (SD 10.3) | 65.2 (SD 10.0) | 66.1 (SD10.7) | 0.665 |

| Hip patients, mean (SD) years | 64.7 (SD 10.5) | 63.9 (SD 10.8) | 64.1 (SD10.5) | 67.8 (SD 9.7) | 0.901 |

| Knee patients, mean (SD) years | 65.7 (SD 9.9) | 65.9 (SD 9.6) | 66.0 (SD 9.6) | 63.8 (SD 11.8) | 0.975 |

| <55 years | 44(17.1) | 19(17.3) | 19(17.3) | 6(15.0) | 0.36 |

| 55-74 years | 166(64.6) | 73 (68.2) | 68(61.8) | 25 (62.5) | |

| ≥75 years | 47(18.3) | 15(14.0) | 23 (20.9) | 9 (22.5) | |

| Sex, female | |||||

| All patients | 141 (54.9) | 63 (58.9) | 58(52.7) | 20 (50.0) | 0.413 |

| Hip patients | 79 (59.0) | 43 (64.2) | 24 (54.7) | 12(52.2) | 0.255 |

| Knee patients | 62 (50.4) | 20 (50.0) | 34(51.5) | 8(47.1) | 0.721 |

| Marital status | 0.007 | ||||

| Married/living together | 192(74.7) | 76(71.0) | 90(81.8) | 26 (65.0) | |

| Divorced | 15(5.8) | 10(9.3) | 1 (0.9) | 4(10.0) | |

| Widowed | 40(15.6) | 20(18.7) | 14(12.7) | 6(15.0) | |

| Single | 10(3.9) | 1 (0.9) | 5 (4.5) | 4(10.0) | |

| Occupational status | 0.561 | ||||

| Retired | 142(55.9) | 58 (54.7) | 60(55.0) | 24(61.5) | |

| Currently working | 81 (31.9) | 37 (34.9) | 33 (30.3) | 11 (28.2) | |

| Currently not working | 13(5.1) | 6(5.6) | 5 (4.5) | 2(5.1) | |

| Medically disabled | 17(6.7) | 5 (4.7) | 10(9.2) | 2(5.1) | |

| In education | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | |

| Not specified | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Ethnicity | 0.312 | ||||

| White | 254 (99.6) | 106(99.1) | 109(100.0) | 39.0(100.0) | |

| Other | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | |

| Not specified | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Comorbiditya | |||||

| Hypertension | 82(31.9) | 31 (29.0) | 35(31.8) | 16(40.0) | 0.649 |

| Diabetes | 27(10.5) | 8(7.5) | 10(9.1) | 9(22.5) | 0.666 |

| Asthma | 30(11.7) | 12(11.2) | 14(12.7) | 4(10.0) | 0.732 |

| Depression | 23 (8.9) | 6(5.6) | 13(11.8) | 4(10.0) | 0.105 |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 15(5.8) | 4 (3.7) | 8(7.3) | 3(7.5) | 0.255 |

| Angina | 16(6.2) | 5 (4.7) | 11 (10.0) | 0 | 0.133 |

| Bronchitis | 7 (2.7) | 1 (0.9) | 6(5.5) | 0 | 0.119 |

| Other | 66 (25.7) | 27 (25.2) | 30 (27.3) | 9(22.5) | 0.844 |

| One or more comorbidities | |||||

| All patients | 168(65.4) | 63 (58.9) | 78(70.9) | 27 (67.5) | 0.063 |

| Hip patients | 77 (57.5) | 34 (50.7) | 27(61.4) | 16(69.6) | 0.163 |

| Knee patients | 91 (74.0) | 29 (72.5) | 51 (77.3) | 11 (64.7) | 0.447 |

Participantmay have reported one ormore comorbidity. SD = standard deviation. TJR = total joint replacement.

Among the study sample of 217 who had full follow-up, hip patients were more likely to have had surgery than knee patients (χ2 = 11.10, degrees of freedom [df] = 1, P = 0.001). Compared with those not having TJR, those who had a TJR were less likely to be married or living together (71.0% versus 81.8%) and more likely to be divorced (9.3% versus 0.9%) or widowed (18.7% versus 12.7%; P = 0.007). Those not having a TJR appeared more likely to have one or more comorbidities (70.9% versus 58.9%), but the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.063).

All patients were relatively similar in their use of services and treatments (Table 2). Around one-third of all individuals had seen a physiotherapist at some time. However, a higher percentage (9.1%) of those not having surgery had seen a rheumatologist than those having surgery (4.7%). Around one-quarter of hip and knee OA patients were taking glucosamine at baseline.

Table 2.

Use of services and treatments at baseline for osteoarthritis at baseline for total joint replacement

| Use of services for OA, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Services | TJR (n = 107) | No TJR (n = 110) |

| Other specialists seen regarding OA | ||

| Physiotherapist | 38(35.5) | 33 (30.0) |

| Other hospital doctor | 12 (11.2) | 6(5.5) |

| Acupuncturist | 12 (11.2) | 11 (10.0) |

| Occupational therapist | 9 (8.4) | 6(5.5) |

| Rheumatologist | 5 (4.7) | 10(9.1) |

| Osteopath | 2(1.9) | 6(5.5) |

| Chiropractor | 2(1.9) | 5 (4.5) |

| Nurse | 1 (0.9) | 4(3.6) |

| Pain clinic specialist | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Treatments received | ||

| Exercise | 33 (30.8) | 40 (36.4) |

| Glucosamine | 28(26.2) | 24(21.8) |

| Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) | 25 (23.4) | 21 (19.1) |

| Heat/cold packs | 21 (19.6) | 23 (20.9) |

| Relaxation/massage | 17 (15.9) | 13 (11.8) |

| Physiotherapy treatments/sessions | 9 (8.4) | 13(11.8) |

| Hydrotherapy | 8(7.5) | 2(1.8) |

| Complementary therapies | 7(6.5) | 1 (0.9) |

| Self-help/discussion group | 0 | 3(2.7) |

| Paid privately for treatments | 29 (27.1) | 29 (26.4) |

OA = osteoarthritis. TJR = total joint replacement.

The 257 participants had been suffering from OA for a mean of 107.5 months (range 2 months to 40 years; Table 3). Just under half (47.0%) required assistance with activities of daily living, and just over a half (53.9%) used a walking stick. More than half (56.1%) described their pain as ‘always present’, one-third as often present (34.0%), and most (91.4%) reported waking up at night due to pain. More than half (59.8%) were taking pain medication more than once a day.

Table 3.

Baseline clinical descriptors of osteoarthritis by surgical outcome for total joint replacement

|

n (%), unless otherwise specified |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical descriptor | Total sample (n = 257) | TJR (n = 107) | No TJR (n = 110) | Loss to follow-up (n = 40) | P-value for TJR vs no TJR |

| Duration, mean (SD) months | |||||

| All patients | 107.5 (SD 112.7) | 79.8 (SD 73.5) | 134.8 (SD 135.3) | 126.0 (SD 135.0) | 0.037 |

| Hip patients | 96.2 (SD 108.8) | 73.5 (SD 63.6) | 141.8 (SD 159.5) | 94.2 (SD 106.4) | 0.243 |

| Knee patients | 120.9 (SD 116.4) | 91.1 (SD88.9) | 130.1 (SD 118.9) | 177.8 (SD 166.5) | 0.176 |

| Assistance with activities of daily living | |||||

| All patients | 119(47.0) | 48 (45.7) | 47(43.1) | 24(61.5) | 0.702 |

| Hip patients | 62 (46.6) | 27 (40.9) | 19 (43.2) | 16 (69.6) | 0.812 |

| Knee patients | 57 (47.5) | 21 (53.8) | 28(43.1) | 8(50.0) | 0.338 |

| Uses walking stick | |||||

| All patients | 137(53.9) | 63 (58.9) | 48 (44.9) | 26(65.0) | 0.04 |

| Hip patients | 70(52.2) | 38(56.7) | 18(40.9) | 14(60.9) | 0.063 |

| Knee patients | 67(55.8) | 25(62.5) | 30 (47.6) | 12(70.6) | 0.16 |

| Best description of frequency of pain | 0.002 | ||||

| Always present | 142 (56.1) | 67 (63.8) | 55 (50.5) | 20 (51.3) | |

| Often present | 86 (34.0) | 35 (33.3) | 35 (32.1) | 16 (41.0) | |

| Sometimes present | 23(9.1) | 3(2.9) | 17(15.6) | 3(7.7) | |

| Present very little | 2 (0.8) | 0 | 2(1.8) | 0 | |

| Missing data | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Waking at night due to pain | 0.205 | ||||

| Not at all | 22 (8.6) | 8(7.5) | 12 (10.9) | 2(5.1) | |

| 1 or 2 nights per week | 25(9.8) | 10 (9.4) | 11 (10.0) | 4(10.3) | |

| Some nights | 84 (32.9) | 32 (30.2) | 39(35.5) | 13(33.3) | |

| Most nights | 124(48.6) | 56 (52.8) | 48 (43.6) | 20(51.3) | |

| Missing data | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Frequency of pain medication | 0.037 | ||||

| >Once/day | 149 (59.8) | 68 (64.8) | 55 (51.4) | 26 (70.3) | |

| Daily | 40 (16.1) | 16 (15.2) | 19 (17.8) | 5(13.5) | |

| <1 month | 34(13.7) | 13(12.4) | 19(17.8) | 2 (5.4) | |

| ≥1 month | 14(5.6) | 5 (4.8) | 7(6.5) | 2 (5.4) | |

| Never | 12(4.8) | 3(2.9) | 7(6.5) | 2 (5.4) | |

| Missing data | 8 | 2 | 3 | 3 | |

| Current treatment | |||||

| Acetaminophen | 105 (40.9) | 26 (24.3) | 36 (32.7) | 11 (27.5) | |

| COX-2 inhibitors | 7(2.7) | 3 (2.8) | 4(3.6) | 2(5.0) | |

| NSAIDS | 117(45.5) | 42 (39.3) | 62 (56.4) | 16(40.0) | |

| Weak opioids | 121 (47.1) | 55(51.4) | 59 (53.6) | 22(55.0) | |

| Strong opioids | 1 (0.4) | 0(0) | 1 (0.9) | 0(0) | |

| Topical NSAIDs | 7(2.7) | 2(1.9) | 4(3.6) | 3(7.5) | |

| None | 19 (7.4) | 3 (2.8) | 9 (8.2) | 2(5.0) | |

COX = cyclooxygenase. NSAIDs = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. SD = standard deviation. TJR = total joint replacement.

Among the study sample of 217 who had full follow-up, pain at baseline was more frequently reported by those who had a TJR (P = 0.002). Use of a walking stick was higher among OA patients having a TJR (58.9%), while of those not having surgery, both hip OA and knee OA patients had the longest duration of OA (mean 141.8 and 130.1 months respectively).

In patients with hip OA, baseline visual analogue scale (VAS) pain scores (P = 0.001), WOMAC stiffness scores (P < 0.001), WOMAC physical function scores (P = 0.001), and Oxford Hip Scores (P < 0.001) were significantly worse among those having had a THR, as to a lesser extent, were WOMAC pain scores (P = 0.025; Table 4).

Table 4.

Baseline pain, function, and health status for hip and knee patients by surgical outcome for total joint replacement

| Outcome score, mean (SD) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale | Total sample (n = 257) | TJR (n = 107) | No TJR (n = 110) | Loss to follow-up (n = 40) | P-value for TJR vs no TJR |

| VAS pain (0 = no pain to 10 = worse pain) | |||||

| Hip patients | 6.5(2.0) | 7.0(1.6) | 5.5(2.4) | 6.8(1.9) | 0.001 |

| Knee patients | 6.4(2.2) | 7.1 (1.8) | 5.8(2.3) | 6.8(2.0) | 0.003 |

| WOMAC pain (0 = no pain to 20 = extreme pain) | |||||

| Hip patients | 10.9 (3.6) | 11.5 (3.6) | 9.9 (3.6) | 10.9 (3.5) | 0.025 |

| Knee patients | 10.7(3.4) | 11.7(2.9) | 10.1 (3.8) | 10.8(2.5) | 0.034 |

| WOMAC physical function (0 = no difficulty to 68 = extreme difficulty) | |||||

| Hip patients | 38.4(12.0) | 41.8(10.7) | 34.1 (11.7) | 36.5(13.5) | 0.001 |

| Knee patients | 35.9 (12.1) | 39.1 (11.2) | 34.0 (13.1) | 35.8(9.4) | 0.044 |

| WOMAC stiffness (0 = no stiffness to 8 = extreme stiffness) | |||||

| Hip patients | 4.8(1.6) | 5.3 (1.3) | 4.2(1.5) | 4.6 (1.9) | <0.001 |

| Knee patients | 4.8(1.7) | 5.2(1.5) | 4.6(1.8) | 4.6(1.4) | 0.05 |

| Oxford (12 = least difficulties to 60 = most difficulties) | |||||

| Oxford Hip Score | 39.7(8.6) | 42.3(7.7) | 36.4(8.4) | 38.3(9.6) | <0.001 |

| Oxford Knee Score | 39.1 (8.7) | 41.7 (8.3) | 37.4(9.2) | 39.8(6.4) | 0.018 |

| SF-36 paina | |||||

| Hip patients | 30.7 (19.5) | 25.9 (18.3) | 37.9 (19.4) | 30.9 (19.8) | 0.001 |

| Knee patients | 35.0(20.4) | 31.7(19.9) | 37.0(20.7) | 35.3(20.5) | 0.157 |

| SF-36 physical function | |||||

| Hip patients | 27.3(20.9) | 22.7(17.8) | 36.0(23.5) | 24.2(19.6) | 0.005 |

| Knee patients | 27.3 (19.9) | 20.4(17.5) | 32.6 (21.1) | 22.8(14.5) | 0.002 |

| SF-36 role limitation (physical) | |||||

| Hip patients | 23.3 (10.2) | 21.3 (9.6) | 27.4(10.0) | 21.5 (10.5) | 0.002 |

| Knee patients | 23.9(10.4) | 21.0(9.6) | 26.1 (10.8) | 22.5(8.7) | 0.016 |

| SF-36 role limitation (mental) | |||||

| Hip patients | 33.7(13.4) | 31.4(14.0) | 36.3(11.9) | 33.6 (13.4) | 0.029 |

| Knee patients | 33.8(14.2) | 32.0 (13.6) | 35.8(15.2) | 30.4(9.9) | 0.141 |

| SF-36 mental health | |||||

| Hip patients | 60.1 (16.3) | 59.6 (16.0) | 61.9 (13.4) | 58.3 (21.2) | 0.521 |

| Knee patients | 60.2(17.9) | 59.3(17.3) | 62.0(18.6) | 55.3(16.3) | 0.317 |

| SF-36 social function | |||||

| Hip patients | 53.2(29.6) | 51.7(29.4) | 60.3(26.5) | 44.0 (32.2) | 0.079 |

| Knee patients | 56.6 (28.3) | 54.2 (28.6) | 59.1 (28.9) | 52.9 (25.6) | 0.359 |

| SF-36 energy and vitality | |||||

| Hip patients | 40.8(18.1) | 39.5 (18.7) | 44.4(16.4) | 37.6 (18.6) | 0.147 |

| Knee patients | 39.7 (17.9) | 40.7(18.1) | 38.8(17.8) | 40.8(18.7) | 0.671 |

| SF-36 health perceptions | |||||

| Hip patients | 58.3(22.9) | 60.6(22.7) | 59.3(22.7) | 49.5(22.7) | 0.885 |

| Knee patients | 51.3 (23.2) | 50.4(23.2) | 52.5 (21.9) | 48.5 (28.7) | 0.725 |

| SF-36 change in health | |||||

| Hip patients | 33.5 (21.4) | 32.0 (22.8) | 34.6 (17.7) | 37.5 (22.8) | 0.459 |

| Knee patients | 35.0 (19.7) | 34.4 (22.4) | 35.2 (18.6) | 35.3 (17.8) | 0.721 |

All SF-36 scores: lower scores indicate worse outcomes. SF-36 = Short Form-36. TJR = total joint replacement. VAS = visual analogue scale. WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index

Comparing patients with hip OA who had a THR with those who did not have a baseline THR, SF-36 scores were significantly lower (worse) in surgical patients for pain, physical function, and role limitation (physical; P = 0.001; P = 0.005; P = 0.002 respectively), and, to a lesser extent, for role limitation (mental; P = 0.029; Table 4). Other baseline SF-36 scores tended to be lower among those who had surgery, but not significantly so.

In patients with knee OA, baseline VAS pain scores were again significantly worse among those having TKR (P = 0.003); and to a lesser extent there were also significantly worse scores for WOMAC pain (P = 0.034), stiffness (P = 0.050), and physical function (P = 0.044); and Oxford Knee Scores (P = 0.018).

Comparing patients who had TKR with those who did not, baseline SF-36 scores were significantly lower (worse) for physical function in surgical patients (P = 0.002), and for role limitation (physical; P = 0.016) to a lesser extent. Other SF-36 scores at baseline, including the pain score, tended to be loweramong those who had surgery, but not significantly so.

Among patients with hip OA, several baseline variables had unadjusted odds ratios of surgery at P<0.003 (VAS pain score, WOMAC physical function and stiffness, Oxford Hip Score, and SF-36 pain, physical function, and role limitation [physical]). Forwards stepwise logistic regression resulted in a final exploratory model using four variables. Adjusted for the other variables in the model, high (worse) WOMAC stiffness scores were most strongly associated with having surgery (P = 0.001). Having one or more comorbidities (P = 0.016) was associated with not having THR, although this was not significantly associated taken on its own (P = 0.273). Using a walking stick was almost significantly associated with having THR (P = 0.053) when adjusted for the other variables, but not in isolation (P = 0.105). Low (worse) SF-36 role limitation (physical) scores were almost significantly associated with having THR (P = 0.062; Table 5).

Table 5.

Odds ratios of total hip replacement for characteristics at baseline for 111 hip osteoarthritis patients with full follow-up

| Baseline covariate | n | Unadjusted odds ratio (95%CI) | P-value | Adjusted odds ratio (95%CI)a | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Separated, divorced, widowed | 111 | 1.78 (0.73 to 4.35) | 0.209 | ||

| One or more comorbidities | 111 | 0.65 (0.30 to 1.41) | 0.273 | 0.29(0.11 to 0.79) | 0.016 |

| Uses walking stick | 111 | 1.89 (0.88to 4.09) | 0.105 | 2.56 (0.99 to 6.61) | 0.053 |

| Pain always present | 111 | 2.00 (1.02 to 4.80) | 0.045 | ||

| VAS pain score (0 = no pain to 10 = worse pain) | 110 | 1.46 (1.18to 1.80) | <0.001 | ||

| WOMAC pain score (0 = no pain to 20 = extreme pain) | 111 | 1.13 (1.02 to 1.26) | 0.027 | ||

| WOMAC physical function score (0 = no difficulty to 68 = extreme difficulty) | 111 | 1.06 (1.03 to 1.10) | 0.001 | ||

| WOMAC stiffness score (0 = no stiffness to 8 = extreme stiffness) | 111 | 1.69 (1.26 to 2.27) | <0.001 | 1.82(1.27 to 2.61) | 0.001 |

| Oxford Hip Score (12 = least difficulties to 60 = most difficulties) | 110 | 1.10 (1.05 to 1.16) | 0.001 | ||

| SF-36 painb | 111 | 0.97 (0.95 to 0.99) | 0.002 | ||

| SF-36 physical function | 111 | 0.97 (0.95 to 0.99) | 0.002 | ||

| SF-36 role limitation (physical) | 111 | 0.94 (0.90 to 0.98) | 0.003 | 0.95(0.91 to 1.00) | 0.062 |

| SF-36 role limitation (mental) | 110 | 0.97 (0.94 to 1.00) | 0.026 | ||

Forward stepwise final model: likelihood ratio χ2 = 28.74, df = 4, P<0.001; receiver operating characteristic area under the curve = 0.76, P<0.001; Nagelkerke pseudo-R2 = 0.32; 58/66 having total joint replacement (TJR) correctly predicted (sensitivity = 87.9%), 27/42 not having TJR correctly predicted (specificity = 64.3%), 85/108 surgical outcomes correctly predicted (correct prediction rate = 78.7%).

All SF-36 scores: lower scores indicate worse outcomes. SF-36 = Short Form-36. VAS = visual analogue scale. WOMAC =Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index.

For patients with knee OA, unadjusted odds ratios of TKR for baseline variables were less significant, the most significant being SF-36 physical function (P = 0.004) and VAS pain score (P = 0.008). Forwards stepwise logistic regression only selected one variable: low (worse) SF-36 physical function scores were significantly associated with having TKR (P = 0.002; Table 6).

Table 6.

Odds ratios of total knee replacement for characteristics at baseline for 106 knee osteoarthritis patients with full follow-up

| Baseline covariate | n | Unadjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI)a | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Separated, divorced, widowed | 106 | 1.67 (0.64 to 4.38) | 0.300 | ||

| One ormore comorbidities | 106 | 0.78 (0.32 to 1.91) | 0.580 | ||

| Uses walking stick | 103 | 1.83 (0.82 to 4.32) | 0.142 | ||

| Pain always present | 104 | 1.29 (0.64 to 3.57) | 0.538 | ||

| VAS pain score (0 = no pain to 10 = worse pain) | 103 | 1.33 (1.08 to 1.64) | 0.008 | ||

| WOMAC pain score (0 = no pain to 20 = extreme pain) | 106 | 1.14 (1.01 to 1.28) | 0.038 | ||

| WOMAC physical function score (0 = no difficulty to 68 = extreme difficulty) | 106 | 1.04 (1.00 to 1.07) | 0.049 | ||

| WOMAC stiffness score (0 = no stiffness to 8 = extreme stiffness) | 106 | 1.27 (1.00 to 1.62) | 0.053 | ||

| Oxford Knee Score (12 = least difficulties to 60 =most difficulties) | 105 | 1.06 (1.01 to 1.11) | 0.021 | ||

| SF-36 painb | 106 | 0.99 (0.97 to 1.01) | 0.191 | ||

| SF-36 physical function | 106 | 0.97 (0.94 to 0.99) | 0.004 | 0.96 (0.94 to 0.99) | 0.002 |

| SF-36 role limitation (physical) | 106 | 0.95 (0.91 to 0.99) | 0.019 | ||

| SF-36 role limitation (mental) | 106 | 0.98 (0.96 to 1.01) | 0.196 | ||

Forward stepwise final model: likelihood ratio χ2 = 11.62, df = 1, P = 0.001; receiver operating characteristic area under the curve = 0.60, P = 0.092; Nagelkerke pseudo-R2 = 0.15; 15/38 having total joint replacement (TJR) correctly predicted (sensitivity = 39.5%), 50/62 not having TJR correctly predicted (specificity = 80.6%), 65/100 surgical outcomes correctly predicted (correct prediction rate = 65.0%).

All SF-36 scores: lower scores indicateworse outcomes. SF-36 = Short Form-36. VAS = visual analogue scale. WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index.

For the 110 individuals who did not undergo TJR, the most common outcome among the 44 hip patients was to continue to monitor the affected joint (34. 1%), while among the 66 knee patients the consultation outcome was no treatment or operation (18.2%; Table 7). Eleven patients (16.7%) with knee OA had an arthroscopy

Table 7.

Treatment options for 110 patients not having total joint replacement: 12 month follow-up data

| Outcome/treatment following consultation with surgeon, n (%) | Hip OA patients (n = 44a) | Knee OA patients n = 66a) | Total (n = 110) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monitor hip/knee | 15(34.1) | 6(9.1) | 21 (19.1) |

| No treatment/no operation | 7(15.9) | 12(18.2) | 19(17.3) |

| Indicated joint to be replaced (no surgery within follow-up time) | 8(18.2) | 9(13.6) | 17(15.5) |

| Injection | 4(9.1) | 9(13.6) | 13(11.9) |

| Recommended physiotherapy | 2 (4.5) | 9(13.6) | 11 (10.0) |

| Arthroscopy | N/A | 11 (16.7) | 11 (10.0) |

| Patient feels not ready | 3 (6.8) | 8(12.1) | 11 (10.0) |

| Further investigation | 1 (2.3) | 4(6.1) | 5 (4.5) |

| Not able to have operation due to other health problem | 3 (6.8) | 1(1.5) | 4 (3.6) |

| Age — too young | 1 (2.3) | 2 (3.0) | 3 (2.7) |

| Exercise | 1 (2.3) | 2 (3.0) | 3 (2.7) |

| Patient not able to have operation due to personal reasons | 2 (4.5) | 0 | 2(1.8) |

| Referral to another specialist | 2 (4.5) | 0 | 2(1.8) |

| Hydrotherapy | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Weight management | 0 | 1(1.5) | 1 (0.9) |

Six hip and eight knee OA patients had more than one outcome following consultation. OA = osteoarthritis.

DISCUSSION

Summary

This study demonstrates that in patients with OA newly referred for consideration of TJR, only 50% ended up having THR within a year, and among knee patients, only 33% had a TKR. Arthroscopy was provided for 17% of knee OA patients despite the evidence for the lack of effectiveness for this procedure.28 The findings provide evidence that patients who report worse pain and poorer physical functioning are more likely to have TJR than those with less severe symptoms.

The role of GPs in referral of patients for consideration of surgery is important, and GPs may need to review their referrals of patients in light of the findings from this study.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study are the adequate sample size, acceptable participation rate of 61%, with few demographic differences compared with non-responders, and a 12-month follow-up. However, the consultation outcome of the non-responders is not known, so this is a study limitation. From previous experience, a 20% attrition rate was predicted, and this study had a rate of 18%. The selection of patients was done systematically, ensuring that all eligible patients were recruited.

The limitations of this study were that some patients may have just wanted a second opinion and despite being referred for consideration of a TJR were not actually considering surgery or were not suitable candidates; this was a patient self-reported study, using validated measurement tools and not based on objective functional and clinical measures; and the recruitment of patients was from one regional centre where patients were seen by any one of 10 orthopaedic surgeons, who may use different criteria forsurgery, compared with each other and compared with surgeons elsewhere in the UK. This study only followed up patients for 12 months, and a longer follow-up period may have been useful to determine if some of the patients ultimately had a TJR. However, the approximate waiting time for TJR at the time of this study was around 100 days so it would have been likely that those who were eligible forsurgery would have had the TJR.

Comparison with existing literature

The decision as to whether a patient has a joint replacement is complex, with studies highlighting the factors that influence an individual's decision to have TJR. Hudaketal discuss ‘medical brokering’, involving physicians who determine the ‘best-abled’ rather than the appropriate candidate, and this occurs where demand for TJR exceeds available resources.11 Patients' symptoms and information sources were two factors influencing decision making, but in addition there was a weighing up of the costs and benefits of having a joint replacement.29 There are also sex differences in willingness to undergo surgery, with women preferring to endure pain rather than risk surgery.30

In the UK, there has been limited work on patients' consideration of surgery. One study found that some individuals who were suitable for hip replacement would not accept surgery if offered;31 this study also examined whether referral for consideration of surgery is dependent on the patient's willingness to undergo surgery. An individual's willingness to consider TJR has been found to be the strongest predictor of time to first TJR.12

Around 12% of participants in this study who were offered a TJR were not ready to undergo the procedure, with a qualitative study on a subsample of these individuals showing that patients may decide not to have TJR, therefore going against medical recommendation.32

Past negative experiences with surgery, and health professionals' advice or apathy linked with past experience, reinforced an individual's decision against having THR.33

There is evidence that TKR has been either overused or underused.34,35 The negative attitude of some medical physicians towards the value of knee replacement may influence this underuse.35 This might be one explanation why a minority of individuals ultimately had TKR in this study.

There is evidence of wide variation in orthopaedic surgeons' decision for TJR,36,37 and a lack of consensus on patient characteristics for TJR.11 Currently in the UK, there is little guidance about who should have TJR. Guidance by the National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions on behalf of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommends that referral forjoint replacement should be made before there is prolonged and established limitation and severe pain.38 However, this study has shown that there was clear variation in the characteristics of patients referred to the orthapaedic surgeons.

Implications for clinical practice

Given the extent of variation in surgical outcome observed in this study, it is likely that clear information is needed for patients and GPs considering TJR as an option. If patients do not wish to have surgery, or are not appropriate candidates, other options should be considered, or more management and assessment should be provided within primary care before referral to the orthopaedic surgeon. NICE guidelines recommend that individuals be offered some of the non-surgical options before considering joint surgery.38 Osteoarthritis is a long-term health problem and TJR is an effective way of treating it. Despite being referred by their GP for consideration of TJR, there are many individuals who, after consultation with the orthopaedic surgeon, may not undergo surgery. Therefore, more evidence is required on which to base effective choices and strategies of management, in partnership between primary and secondary care, to ensure the most effective outcomes and the best quality of care for these individuals.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all the patients who took part, Professor Alan Silman and Dr Peter Kay for their advice on the study, and Professor Peter Croft for his comments on the manuscript.

Funding

Gretl A McHugh received a Faculty of Medical and Human Sciences, University of Manchester postdoctoral fellowship.

Ethical approval

LREC approval for the study was grant by Wrightington, Wigan and Leigh Research Ethics Committee (Ref: 06/Q1410/30).

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.Birchfield PC. Osteoarthritis overview. Geriatr Nurs. 2001;22(3):124–130. doi: 10.1067/mgn.2001.116375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Victor CR, Ross F, Axford J. Capturing lay perspectives in a randomized control trial of a health promotion intervention for people with osteoarthritis of the knee. J Eval Clin Prac. 2004;10(1):63–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2003.00395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McHugh GA, Luker KA, Campbell M, et al. A longitudinal study exploring pain control, treatment and service provision for individuals with end-stage lower limb osteoarthritis. Rhuematology. 2007;46(4):631–637. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fitzpatrick R, Shortall E, Sculpher M, et al. Primary total hip replacement surgery: a systematic review of outcomes and modelling of cost-effectiveness associated with different prosthesis. Health Technol Assess. 1998;2(20):1–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawker G, Wright J, Coyte P, et al. Health-related quality of life after knee replacement. Results of the knee replacement patient outcomes research team study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(2):163–173. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199802000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Frost S, et al. Evidence for the validity of patient- based instrument for assessment of outcome after revision hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(8):1125–1129. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.83b8.11643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hospital Episode Statistics Online. Total procedures and interventions 2009-2010. http://www.hesonline.nhs.uk/Ease/servlet/ContentServer?siteID=1937&categoryID=210 (accessed 19 May 2011) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birrell F, Afzal C, Nahit E, et al. Predictors of hip joint replacement in new attendersin primary care with hip pain. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53(486):26–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tennant A, Fear J, Pickering A, et al. Prevalence of knee problems in the population aged 55 years and over: identifying the need for knee arthroplasty. BMJ. 1995;310(6990):1291–1293. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6990.1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fitzpatrick R, Norquist JM, Reeves BC, et al. Equityand need when waiting for total hip replacement surgery. J Eval Clin Prac. 2004;10(1):3–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2003.00448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hudak PL, Grassau P, Glazier RH, et al. Not everyone who needs one is going to get one: the influence of medical brokering on patient candidacy for total joint arthroplasty. Med Decis Making. 2008;28(5):773–780. doi: 10.1177/0272989X08318468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawker GA, Guan J, Croxford R, et al. A prospective population-based study of the predictors of undergoing total joint arthroplasty. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(10):3212–3220. doi: 10.1002/art.22146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gossec L, Tubach F, Baron G, et al. Predictive factors of total hip replacement due to primary osteoarthritis: a prospective 2 year study of 505 patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(7):1028–1032. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.029546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hawker GA, Wright JG, Coyte PC, et al. Differences between men and women in the rate of use of hip and knee arthroplasty. N Eng J Med. 2000;342(14):1016–1022. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004063421405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeni JA, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Clinical predictors of elective total joint replacement in persons with end-stage knee osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:86. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McHugh GA, Campbell M, Silman AJ, et al. Patient waiting for a hip or knee joint replacement: is there any prioritization for surgery? J Eval Clin Pract. 2008;14(3):361–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2007.00866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, et al. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient-relevant outcomes following total hip or knee arthroplasty in osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 1988;15(12):1833–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey: manual and interpretation guide. Boston, MA: The Health Institute New England Medical Centre; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Dewey JE. How to score version 2 of the SF-36® Health Survey. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.NHS Modernisation Agency. Improving orthopaedic services: a guide for clinicians, managers and service commissioners. London: Department of Health; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fitzpatrick R, Morris R, Jajat S, et al. The value of short and simple measures to assess outcomes for patients of total hip replacement surgery. Qual Health Care. 2000;9(3):146–150. doi: 10.1136/qhc.9.3.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Murray D, Carr A. Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80(1):63–69. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.80b1.7859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Frost S, et al. Evidence for the validity of patient-based instrument forassessment of outcome after revision hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(8):1125–1129. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.83b8.11643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jinks C, Jordan K, Croft P. Measuring the population impact of knee pain and disability with the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) Pain. 2002;100(1-2):55–64. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00239-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brazier J, Harper R, Jones NMB. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measures for primary care. BMJ. 1992;305(6846):160–164. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6846.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. 2nd edn. New York: John Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Field A. Discovering statistics using SPSS. 3rd edn. London: Sage Publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirkley A, Birmingham TB, Litchfield RB, et al. A randomized trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(11):1097–1107. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clark JP, Hudak PL, Hawker GA, et al. The moving target: a qualitative study of elderly patients' decision-making regarding total joint replacement surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(7):1366–1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karlson EW, Daltroy LH, Liang MH, et al. Gender differences in patient preferences may underlie differential utilization of elective surgery. Am J Med. 1997;102(6):524–530. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frankel S, Eachus J, Pearson N, et al. Population requirements for primary hip replacement surgery: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 1999;353(9161):1304–1309. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)06451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McHugh GA, Luker KA. Influences on individuals with osteoarthritis in deciding to undergo a hip or knee joint replacement: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31(15):1257–1266. doi: 10.1080/09638280802535129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ballantyne PJ, Gignac MAM, Hawker GA. A patient-centered perspective on surgery avoidance for hip or knee arthritis: lesson for the future. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(1):27–34. doi: 10.1002/art.22472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dieppe P, Basler H-D, Chard J, et al. Knee replacement surgery for osteoarthritis: effectiveness, practice variations, indications and possible determinants of utilization. Rheumatology. 1999;38(1):73–83. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jüni P, Dieppe P, Donovan J, et al. Population requirements for primary knee replacement surgery: a cross-sectional study. Rheumatology. 2003;42(4):516–521. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mancuso CA, Ranawat CS, Esdaile JM, et al. Indications for total hip and total knee arthroplasties: results of orthopaedic surveys. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11(1):34–46. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(96)80159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maillefert JF, Roy C, Cadet C, et al. Factors influencing surgeons' decisions in the indication for total joint replacement in hip osteoarthritis in real life. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(2):255–262. doi: 10.1002/art.23331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions on behalf of NICE. Osteoarthritis: national clinical guideline for care and management in adults. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]