Abstract

Stimulation of Ag-specific inducible Treg can enhance resolution of autoimmune disease. Conventional methods to induce Treg often require induction of autoimmune disease or subjection to infection. Reovirus adhesin, protein σ1 (pσ1), can successfully facilitate tolerance when fused to a tolerogen. We tested whether myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) fused to pσ1 (MOG-pσ1) can stimulate Ag-specific Treg. We show that C57BL/6 mice treated nasally with MOG-pσ1 fail to induce MOG-specific Abs and delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) responses and resist EAE. Such resistance was attributed to stimulation of Foxp3+ Treg, as well as Th2 cells. MOG-pσ1’s protective capacity was abrogated in IL-10−/− mice, but restored when adoptively transferred with MOG-p σ1-induced Treg. As a therapeutic, MOG-pσ1 diminished EAE within 24 h of nasal application, unlike recombinant MOG (rMOG), pσ1, or pσ1+rMOG, implicating the importance of Ag specificity by pσ1-based therapeutics. MOG-pσ1-treated mice showed elevated IL-4, IL-10, and IL-28 production by CD4+ T cells, unlike rMOG treated or control mice that produced elevated IFN-γ or IL-17, respectively. These data show the feasibility of using pσ1 as a tolerogen platform for Ag-specific tolerance induction and highlight its potential use as an immunotherapeutic for autoimmunity.

Keywords: Autoimmunity, EAE, Mucosal immunity, Treg

Introduction

Mimicking some aspects of multiple sclerosis, EAE is a T-cell-dependent inflammatory disease highly reproducible in rodents subsequent immunization of susceptible strains with TCR-reactive peptides [1–3]. T-cell recognition of these peptides eventually causes a progressive demyelination [3], further amplified by inflammatory macrophage [4–6] and neutrophil infiltration [7–9]. IL-17 is believed to be the principal mediator of the inflammation observed in EAE [10–14]. However, intervention with regulatory T cells, most commonly by inducible CD25+ CD4+ T cells, can reverse IL-17 action via the production of IL-10 [15–17] and other regulatory cytokines [18–21]. Alternatively, IL-28 has recently been shown to confer protection via Foxp3+ CD25−CD4+ T cells when Treg were lost upon coneutralization of CD25 and TGF-β [16]. Moreover, IL-4- and/or IL-13-producing Th2 cells can also dampen IL-17 and confer variable levels of protection [18–20].

Experimental delivery of auto-Ags has been successfully used to treat autoimmunity by inducing tolerance. Such treatments can result in immune deviation via Th2 cell cytokines, TGF-β-producing Th3 cells, Treg, or other regulatory CD4+ or CD8+ T-cell subsets producing IL-10 [21–25]. Nonetheless, such approaches are generally compromised because of the unavailability of Ags or large and multiple doses of Ags required to achieve T-cell unresponsiveness. Thus, improved methods for tolerance induction are needed.

Past studies have shown that M cells, uniquely specialized epithelial cells responsible for mucosal sampling of the gut and nasal passages, are required for tolerance induction [26]. To enhance Ag uptake, we adapted protein sigma 1 (pσ1) from reovirus type 3, a protein known to bind to M cells [15, 27], as a targeting moiety for tolerance induction. When OVA was genetically fused to pσ1, referred to as OVA-pσ1, tolerance was obtained even in the presence of potent mucosal adjuvants, cholera toxin or CpG-ODN [15, 27]. Likewise, the addition of proteolipid protein peptide (PLP130–151) to OVA-pσ1 was also effective in stimulating Ag-specific tolerance and protection against PLP-induced EAE [16].

Here, we show that a single dose of a pσ1 fusion protein comprising the extracellular domain for myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) peptide29–146, referred to as MOG-pσ1, but not recombinant (rMOG) alone, when administered to mice, entirely prevents CNS pathology and clinical manifestation of MOG35–55-induced EAE via production of IL-10 and IL-28 by Treg and IL-4 and IL-28 by Foxp3+ Th2 cells. We show that IL-10 production is essential to mediate MOG-pσ1-induced tolerance for protection against EAE, as evidenced by the inability to prevent EAE in MOG-pσ1-dosed IL-10−/− mice. Remarkably, treatment of C57BL/6 mice at the peak of the disease with a single nasal dose of MOG-pσ1 resulted in dramatic and immediate remission from EAE possibly due to the recruitment or conscription of Treg. This intervention was again found to be Ag-specific, further suggesting the use of pσ1-based therapeutics as an ideal treatment for autoimmune diseases.

Results

MOG-pσ1-mediated protection against EAE is abated in IL-10−/− mice

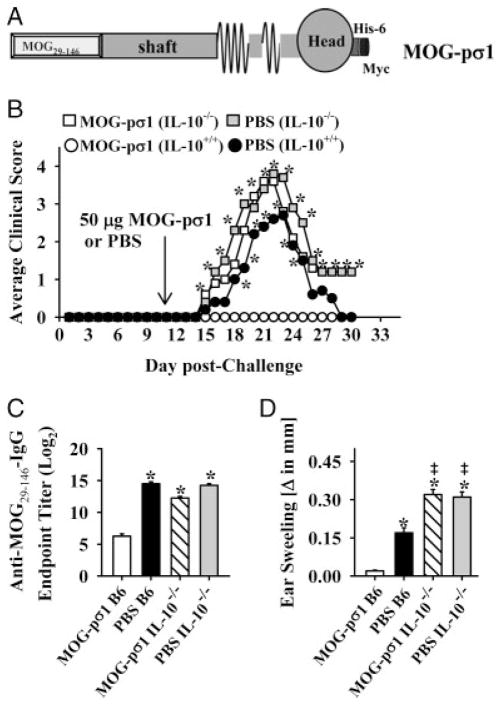

The extracellular domain of MOG (MOG29–146) was genetically fused to pσ1, termed MOG-pσ1 (Fig. 1A), and its efficacy against EAE was tested in susceptible C57BL/6 mice. To determine whether IL-10 is essential for MOG-pσ1-mediated protection against acute EAE, studies were performed administering MOG-pσ1 during EAE in both WT and IL-10−/− mice. IL-10−/− and WT mice were challenged with MOG35–55 on day 0 and treated with 50 μg of MOG-pσ1 or with PBS on day 11 post-challenge (p.ch). As expected, MOG-pσ1 treatment of WT mice completely suppressed development of clinical disease (Fig. 1B and Table 1). Clinical manifestations of EAE exhibited by PBS- or MOG-pσ1-treated IL-10−/− mice were more severe than the disease in PBS-dosed WT mice (Fig. 1B and Table 1). The average peak clinical score in MOG-pσ1- and PBS-dosed IL-10−/− mice was nearly 4 in contrast to PBS-dosed WT mice. On day 21 p.ch, serum samples were collected from each group to measure circulating IgG anti-MOG Ab levels. In contrast to MOG-pσ1-dosed WT mice that showed significant reduction in MOG-specific serum IgG Ab levels, PBS-dosed WT mice, as well as MOG-pσ1-and PBS-dosed IL-10−/− mice, exhibited significantly enhanced serum IgG anti-MOG Ab titers (p<0.001; Fig. 1C). MOG-pσ1-dosed WT mice were unresponsive to the delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) challenge with MOG35–55 peptide, whereas PBS-dosed WT mice and IL-10−/− mice dosed with MOG-pσ1 or PBS developed MOG3–55-specific DTH responses (p<0.001; Fig. 1D). Consistent with the more pronounced EAE, IL-10−/− mice, independent of treatment, developed significantly higher MOG35–55-specific DTH responses than PBS-dosed WT mice (p<0.05; Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

MOG-pσ1-mediated protection against EAE is abated in IL-10−/− mice. (A) Schematic representation of MOG-pσ1 from the N-terminus: MOG29–146, pσ1 (shaft and head), 6 histidine-tag, and Myc Ag-tag. (B) C57BL/6 WT and IL-10−/− mice were treated with PBS or 50 μg MOG-pσ1 11 days after MOG35–55-induced EAE. The graph shows an average of 10–11 mice per group from two experiments. (C) Serum samples were collected from these mice at the peak of the disease (day 21 p.ch), and IgG anti-MOG endpoint Ab titers were determined by ELISA. Mean+SEM of 5 individual mice per group is depicted from one experiment. (D) MOG35–55-specific DTH responses were measured in MOG-pσ1- and PBS-dosed and challenged WT and IL-10−/− mice on day 28 p.ch. Mean+SEM of 5 individual mice per group is depicted from one experiment. *p<0.001 (one-way ANOVA followed by the posthoc Tukey test for differences in clinical scores and Ab variations) versus MOG-pσ1-dosed C57BL/6 mice.

Table 1.

MOG-pσ1 is unable to confer protection against EAE in IL-10−/− micea)

| Treatmentb) | EAE/totalc) | Onsetd) | Max. scoree) | CSf) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBS IL-10+/+ | 10/10 | 16.3±1.79* | 3 | 20.8 |

| MOG-pσ1 IL-10+/+ | 0/10 | 0±0 | 0 | 0 |

| PBS IL-10−/− | 11/11 | 14.64±1.15* | 4 | 33.9 |

| MOG-pσ1 IL-10−/− | 11/11 | 14.7±1.88* | 4 | 29.2 |

p<0.001 for PBS versus MOG-pσ1-dosed mice.

C57BL/6 (IL-10+/+) and IL-10−/− mice were challenged as described in the Materials and methods section.

Mice were treated nasally 11 days after challenge with 50 μg of MOG-pσ1 or with PBS (Fig. 1).

Number of mice with EAE/total in group.

Mean day±SD of clinical disease onset.

Maximum (max.) daily clinical score.

Cumulative scores (CS) were calculated as the sum of all scores from disease onset to day 30 post-challenge, divided by the number of mice in each group.

MOG-pσ1 stimulates the induction of CD25+CD4+ Treg

To learn the types of regulatory T-cell-induced subsequent nasal application of MOG-pσ1, FACS analysis was performed on WT mice previously dosed nasally with 50 μg of MOG-pσ1 or with PBS prior to EAE induction. Lymphocytes isolated at the peak of the clinical disease (day 20 p.ch) from their head and neck lymph nodes (HNLNs), mesenteric LNs (MLNs), and spleens were cultured for 72 h with MOG35–55 and evaluated for regulatory T-cell phenotype by FACS. MOG-pσ1-protected mice generated >50% more Foxp3+CD25+CD4+ T cells, as well as Foxp3+ CD25−CD4+ T cells, than diseased PBS-dosed mice (p<0.001; Table 2). Moreover, >75% of these Foxp3+CD25+CD4+ T cells produced IL-10, whereas just as many Foxp3+CD25−CD4+ T cells produced IL-4, and a smaller, but a significant portion, produced TGF-β. CTLA-4 expression did not differ between the Foxp3+CD4+ T cells among PBS- and MOG-pσ1-dosed mice. Examining for expression of alternative molecules associated with regulatory T cells, nearly a twofold enhancement in expression of the ecto-nucleotidase CD73 by CD25+ and CD25−Foxp3+CD4+ T cells isolated from MOG-pσ1-protected mice was observed when compared to similar cells from PBS-dosed diseased mice (Table 2); however, no notable differences were observed in ecto-nucleotidase CD39 expression. Thus, MOG-pσ1 stimulates the production of Treg.

Table 2.

Characterization of lymphocytes from combined LNs and spleens of PBS- and MOG-pσ1-dosed C57BL/6 micea)

| Treatmentb) | CD25+CD4+ Tregc) | CD25−CD4+ T cellsc) |

|---|---|---|

| MOG-pσ1 | 27.19±1.23* | 74.6±3.18 |

| Foxp3+ | 96.28±2.47 | 23.18±1.58* |

| Foxp3+ Treg | Foxp3+CD25− T cells | |

| TGF-β+ | 3.69±0.41 | 9.22±1.08* |

| CTLA-4+ | 27.48±1.31 | 2.56±1.12 |

| IL-10+ | 77.17±2.17* | 7.57±1.78 |

| IL-4+ | 15.68±1.29* | 76.29±1.84* |

| CD73+ | 64.2±2.58* | 22.6±1.25* |

| CD39+ | 3.72±0.48 | 2.89±1.42 |

| PBS | 11.9±1.18 | 89.73±3.28 |

| Foxp3+ | 89.74±3.98 | 8.18±0.73 |

| Foxp3+ Treg | Foxp3+CD25− T cells | |

| TGF-β+ | 3.44±0.47 | 2.02±0.34 |

| CTLA-4+ | 25.82±0.86 | 3.07±1.28 |

| IL-10+ | 11.54±1.09 | 4.28±2.69 |

| IL-4+ | 4.53±0.71 | 5.62±1.12 |

| CD73+ | 33.9±3.29 | 10.7±0.48 |

| CD39+ | 2.83±0.48 | 2.18±0.74 |

Mean+SEM of combined HNLNs, MLNs, and spleens from three mice per group is presented.

p<0.001 for PBS versus MOG-pσ1-dosed mice.

C57BL/6 mice were induced with EAE as described in the Materials and methods section.

Mice were nasally dosed 21 days prior to challenge with 50 μg of MOG-pσ1 or with PBS.

Percentages of Treg and CD25−CD4+ T cells were analyzed by FACS on day 20 p.ch. CD25+CD4+ and CD25−CD4+ T cells are presented as a proportion of CD4+ T cells.

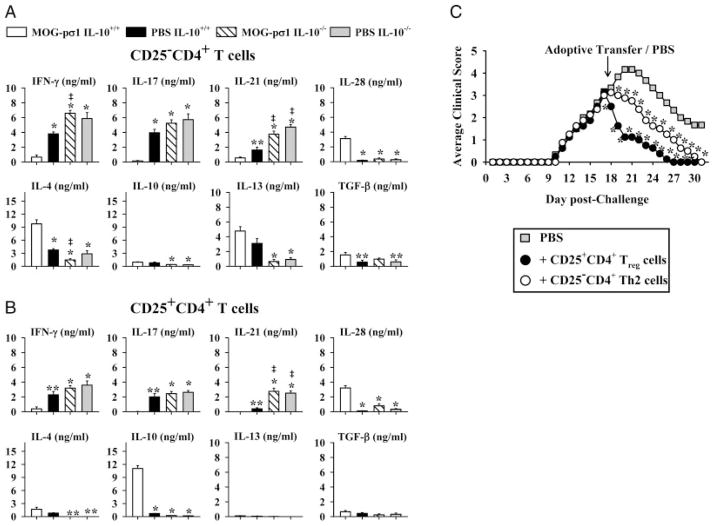

MOG-pσ1-induced Treg show preferential production of IL-10 and IL-28

To determine the responsible cytokines induced by the MOG-pσ1, cytokine analyses were performed on purified CD25−CD4+ and CD25+CD4+ T cells isolated at the peak of the clinical EAE (around day 20 p.ch) from HNLNs, MLNs, and spleens of mice previously dosed with MOG-pσ1 or PBS and subsequently subjected to EAE challenge 1 wk later. CD25+CD4+ and CD25−CD4+ T cells were isolated from MOG-pσ1- or PBS-dosed WT and IL-10−/− mice and restimulated with MOG35–55 for three days. CD25−CD4+ T cells obtained from MOG-pσ1-dosed WT mice did not produce IL-17, but secreted marginal amounts of IL-21 and IFN-γ (Fig. 2A). In contrast, a similar population from PBS-dosed mice produced mostly IL-17 and IL-21, as evident by >28-fold and ~3-fold enhancement, respectively, when compared to MOG-pσ1-dosed mice (p<0.001; Fig. 2A). On the other hand, CD25−CD4+ T cells from MOG-pσ1-dosed mice produced elevated levels of IL-4 and IL-28 by 2.6- and 10-fold more, respectively, than those same T cells from PBS-dosed mice (p<0.001; Fig. 2A). In a similar fashion, MOG-pσ1-induced Treg from WT mice showed significant elevations in IL-10 and IL-28 by 16- and 29-fold, respectively, when compared to Treg from diseased WT mice (p<0.001) with concomitant reductions in IFN-γ by 5.9-fold, IL-17 by 44-fold, and IL-21 by >400-fold (p<0.05; Fig. 2B). There were no significant changes in IL-13 production among WT mice (Fig. 2). Consistent with the observed enhanced clinical disease, both CD25−CD4+ and CD25+CD4+ T cells from PBS and MOG-pσ1-dosed IL-10−/− mice showed elevations in proinflammatory cytokine production evident by the increased IFN-γ, IL-17, and IL-21 with minimal IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, and IL-28 production (Fig. 2A and B). These results demonstrate that MOG-pσ1-mediated protection is associated with enhanced production of IL-4, IL-10, and IL-28 with concomitant inhibition of Th17-and Th1-type cytokines, and such responses fail to develop in IL-10−/− mice.

Figure 2.

IL-10-producing cells are essential for MOG-pσ1-mediated protection. (A) CD25−CD4+ T cells and (B) CD25+CD4+ T cells were purified from C57BL/6 WT and IL-10−/− mice that were dosed with 50 μg of MOG-pσ1 or PBS on day -7, challenged with EAE on day 0, and T cells isolated 21 days after EAE challenge. These were restimulated in vitro with MOG35–55 in the presence of irradiated APCs. Cytokine levels (mean+SEM from triplicate cultures of two experiments) in culture supernatants were measured by ELISA 3 days after culture, and values are corrected for cytokine levels produced by unstimulated cells. *p<0.001; ** p<0.05 versus MOG-pσ1-dosed C57BL/6 mice, ‡p<0.05 versus PBS-dosed C57BL/6 mice (one-way ANOVA followed by the posthoc Tukey test for differences in cytokine production). (C) EAE was induced in IL-10−/− mice at day 0, and at day 17 mice were treated with PBS or adoptively transferred with 6 × 105 CD25+CD4+ or CD25−CD4+ T cells isolated at >95% purity from WT mice treated 14 days earlier with MOG-pσ1. Average of 5 mice per group and data are representative of two experiments; *p<0.05 versus PBS-dosed mice (one-way ANOVA followed by the posthoc Tukey test for differences in clinical scores).

Protection is restored upon adoptive transfer with IL-10-producing Treg

To determine whether MOG-pσ1-primed Treg or CD25−CD4+ T cells can restore protection in IL-10−/− mice, these purified T-cell subsets were isolated from MOG-pσ1-treated WT mice and adoptively transferred into diseased IL-10−/− mice near the peak of EAE (17 days p.ch.). In contrast to PBS-dosed control mice, recipient mice given Treg showed an immediate remission of EAE, totally recovering by day 27 (p<0.05, Fig 2C). Adoptive transfer of CD25−CD4+ T cells also resulted in a amelioration of clinical disease, but was delayed relative to the impact by Treg (Fig. 2C).

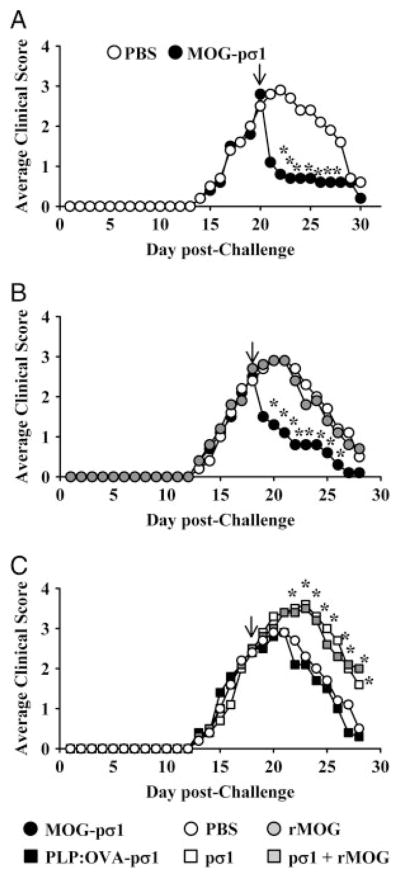

Single nasal MOG-pσ1 dose immediately abates ongoing EAE in an Ag-dependent fashion

Results, thus far, show that nasally applied MOG-pσ1 can stimulate the induction of Treg as well as their adoptive transfer can confer protection against EAE. However, the potency of MOG-pσ1 as a therapeutic remains untested. As such, mice were induced with EAE, and upon peak of the clinical disease, they were treated nasally with 50 μg of MOG-pσ1 or PBS. Remarkably, significant and nearly three-fold reduction in clinical symptoms were observed in MOG-pσ1-treated mice within 24 h after treatment (p<0.05; Fig. 3). This immediate and dramatic drop in EAE clinical disease by MOG-pσ1-treated mice was followed by an 8-day recovery phase in which MOG-pσ1-treated mice exhibited no further EAE.

Figure 3.

MOG-pσ1 treatment suppresses ongoing EAE. (A) C57BL/6 mice were dosed nasally with 50 μg of MOG-pσ1 or PBS at the peak of clinical disease (arrow; 20 days p.ch. with MOG35–55 peptide). Data are representative of six experiments. C57BL/6 mice previously challenged with MOG35–55 were treated 18 days later (arrow) with (B) PBS, or 50 μg MOG-pσ1 or rMOG; or (C) PBS, 50 μg pσ1, 50 μg rMOG+50 μg pσ1, or with 100 μg PLP:OVA-pσ1. Data are representative of two experiments, and the average of 5–10 mice per group is depicted: *p<0.05 versus PBS-treated mice (one-way ANOVA followed by the posthoc Tukey test for differences in clinical scores).

To determine whether this dramatic improvement in clinical disease after MOG-pσ1 treatment was due to the pσ1, mice challenged with MOG35–55 peptide to induce EAE were nasally treated with 50 μg MOG-pσ1, rMOG, or pσ1; 50 μg of rMOG+ 50 μg of pσ1; or 100 μg PLP:OVA-pσ1 on day 18 after EAE induction (Fig. 3B and C). Mice were monitored daily for the development of clinical disease. Treatment with MOG-pσ1 reversed EAE, and the mice reproducibly underwent dramatic remission of disease within the first 24 h (Fig. 3B). In contrast, mice treated with PBS, rMOG, PLP:OVA-pσ1, pσ1 alone, or rMOG+pσ1 showed no intervention upon clinical disease (Fig. 3B and C). In fact, mice given pσ1 or pσ1+rMOG developed more severe clinical symptoms than PBS-dosed mice (Fig. 3C). Thus, these results show the Ag specificity by MOG-pσ1-mediated therapy since rMOG, Ag-fused or simply pσ1 alone, could not alleviate EAE.

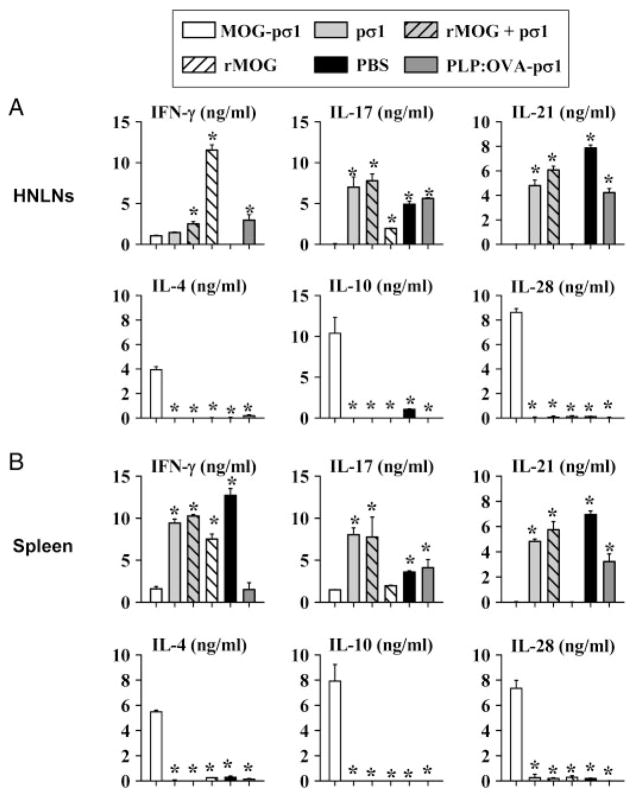

MOG-pσ1 confers protection via the stimulation of regulatory/Th2-type cytokines

Aditional analyses were performed to assess the type of regulatory/Th2-type cytokines induced following MOG-pσ1 intervention upon EAE. Total HNLN and splenic CD4+ T cells were isolated and restimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 mAbs. Both HNLN (Fig. 4A) and splenic (Fig. 4B) CD4+ T cells showed elevations in IL-4, IL-10, and IL-28 production with concomitant reductions in IL-17, IL-21, and IFN-γ when compared to PBS-treated mice. Interestingly, rMOG-treated mice, while also showing reduced IL-17 and IL-21, showed preferential enhancement of IFN-γ, but the anti-inflammatory cytokine levels remained unaltered (Fig. 4A and B). Treatment with pσ1, rMOG+pσ1, or PLP:OVA-pσ1 continued to present elevated Th1 and Th17 cell responses and no anti-inflammatory cytokines (Fig. 4A and B). Thus, these collective data show that MOG-pσ1 can act therapeutically to treat EAE and stimulate the induction of varied regulatory and Th2 cell subsets, producing IL-4, IL-10, and IL-28 to dampen proinflammatory cytokines, IFN-γ, IL-17, and IL-21, and reverse disease course.

Figure 4.

MOG-pσ1-induced therapy is regulatory/Th2 cell-dependent. Total CD4+ T cells were isolated 1 wk after intervention from (A) HNLNs and (B) spleens from mice treated with MOG-pσ1, pσ1, rMOG+pσ1, rMOG, PBS, or PLP:OVA-pσ1 (from Fig. 3) and restimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 mAbs for 3 days. Cytokine (IFN-γ, IL-17, IL-21, IL-4, IL-10, and IL-28) levels in cell culture supernatants were measured by ELISA, and values are corrected for cytokine levels from unstimulated cells. Data are representative of two experiments, and results depict mean+SEM of 5–6 mice per group; *p<0.05 versus MOG-pσ1-dosed C57BL/6 mice (one-way ANOVA followed by the posthoc Tukey test for differences in cytokine production).

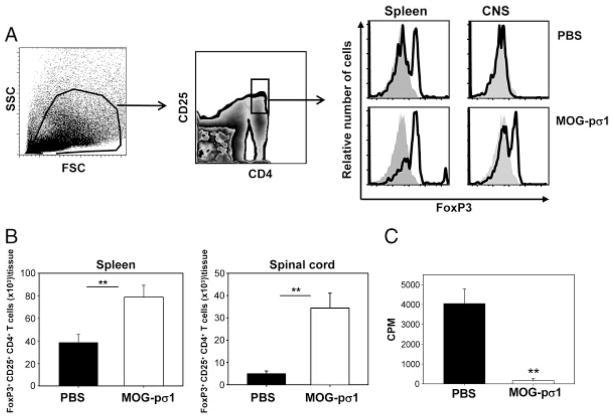

MOG-pσ1 treatment increases the number of Treg in the CNS

MOG-pσ1 can readily reduce EAE within 24 h of treatment, suggesting possible recruitment of Treg into the CNS. To test this possibility, mice with EAE were treated with MOG-pσ1 or PBS, and 24 h later, mice splenic, and spinal cord lymphocytes were evaluated for their induction of Treg (Fig. 5A and B). MOG-pσ1 enhanced the number of Treg in both the CNS and periphery, suggesting that this vaccine can inhibit further inflammatory T-cell infiltration into the CNS. To test their functionality, splenic CD4+ T cells purified from MOG-pσ1-treated mice and restimulated with MOG35–55 in a proliferation assay showed depressed proliferation relative to those CD4+ T cells from PBS-treated mice (Fig. 5C). Thus, MOG-pσ1 recruits and expands Treg to resolve EAE.

Figure 5.

MOG-pσ1 induces an upregulation of Foxp3+ cells. C57BL/6 mice were nasally dosed with PBS or MOG-pσ1 at the peak of EAE, and splenic and CNS lymphocytes were evaluated 24 h later. (A) Left and middle panels show gating strategy to identify Treg using splenic lymphocytes. Right panel shows Foxp3 expression (solid line) by gated CD25+CD4+ T cells versus isotype control (shaded histographs). (B) Total number of Foxp3+ Treg in the spleens and spinal cords from PBS- or MOG-pσ1-treated mice; the mean+SEM of five individual mice per group is depicted; and the data are representative of three experiments. (C) Total splenic CD4+ T cells from PBS- or MOG-pσ1-dosed mice were MOG35–55-restimulated for 4 days, and proliferation was assessed by [3H]-thymidine uptake. Depicted is the mean+SEM of quadruplicate cultures from two experiments. **p<0.01 versus PBS-treated mice (one-way ANOVA followed by the posthoc Tukey test for differences in Treg percentages and CD4+ T-cell proliferation).

Discussion

EAE is a severe neurological disorder initiated by myelin-reactive encephalitogenic T cells that secrete proinflammatory mediators to activate cells locally in the CNS and recruit peripheral inflammatory cells that ultimately attack myelin [28–30]. Significant efforts have been focused on treating EAE by stimulating myelin-specific tolerance [31–34], as well as bystander effect [19, 30]. Additionally, successful downregulation of autoimmune responses has been reported following multiple mucosal administrations of autoreactive Ags chemically coupled [31, 35] or genetically fused [32] to cholera toxin B subunit, or harbored encephalitogenic peptides within IgG CDR3 [33, 34]. In either case, multiple and larger doses of the therapeutic were required for intervention. Along these lines, we have shown that protection against relapsing–remitting EAE can be achieved by just a single nasal dose of pσ1-based tolerogen, PLP:OVA-pσ1 [16]. PLP:OVA-pσ1 prevents development of fully pronounced EAE by inducing Treg that specifically downregulate encephalitogenic PLP139–151-activated T cells. Interestingly, a single 50 μg nasal dose of MOG-pσ1 is entirely protective against development and clinical manifestation of MOG35–55-induced EAE. This protective effect is MOG-specific, as evidenced by the striking reduction in serum anti-MOG IgG Ab titers and the virtual lack of MOG35–55-specific DTH responses. Likewise, protection is attributed to enhanced production of IL-4, IL-10, and IL-28 with consequential depression of proinflammatory Th1- and Th17-type cytokines. Even more striking is a rapid and significant improvement from EAE of mice given a single nasal dose of MOG-pσ1 at the peak of EAE. Again, this intervention appears to be MOG specific since when mice were treated with pσ1 alone or coadministered with rMOG, the EAE became more severe, implicating the importance of tolerogen being covalently attached to pσ1 [15, 16]. While currently it is unclear how MOG-pσ1 reverses EAE at the peak of disease, Treg appear to be circulating in diseased mice, as evidenced in analysis of peripheral lymphoid tissues (Fig. 5A and B), and these seem to be recruited into in the spinal cord subsequent MOG-pσ1 treatment (Fig. 5A and B). Alternatively, MOG-pσ1 may be having a selective impact upon encephalitogenic CD4+ T cells, as suggested in our earlier study showing OVA-pσ1-mediated apoptosis of OVA transgenic CD4+ T cells [15]. Current studies are focusing on distinguishing between these possibilities and determining how such Treg are recruited into CNS.

Protection against EAE was abated in IL-10−/− mice, consistent with previous reports showing that IL-10−/− mice induced with EAE develop more severe disease [36, 37]. Further evaluation of diseased MOG-pσ1-treated IL-10−/− mice revealed significant enhancement in rMOG-specific IgG Ab titers and MOG35–55-specific DTH responses when compared to MOG-pσ1-protected WT mice. The reduction of IL-4 secretion by IL-10−/− mice may be related to the activation of proinflammatory Th1 and Th17 cells, as suggested by others [12, 38]. Furthermore, the relevance of IL-10 in our system was confirmed by the capacity of IL-10- producing CD4+ T cells to restore protection in IL-10−/− mice.

In addition, the induced CD25−CD4+ T cells from the MOG-pσ1-treated mice produced mostly IL-4, consistent with our findings when OVA or PLP139–151 tolerogens were used [15, 16]. IL-4, being a major Th2-type cytokine, inhibits the differentiation of Th17 cells [12, 38] and negatively regulates IFN-γ production [39]. IL-4 appears to support IL-10-dependent protection against EAE, as observed in MOG-pσ1-dosed C57BL/6 mice via induction of Th2 cells and in vivo IL-4 neutralization studies showing partial loss of PLP:OVA-pσ1’s protective capacity against EAE [16]. Alternatively, IL-4 production induced by IL-10 may be important in the development of Treg, as previously suggested by the enhanced conversion of CD25−CD4+ T cells into Treg [40].

A significant finding from these collective studies was the observation that both CD25−CD4+ and CD25+CD4+ T-cell subsets produced IL-28 after MOG-pσ1 treatment. IL-28 previously was shown to mediate protection against PLP139–151-dependent EAE when Treg were neutralized with consequential reductions in IL-10 production [16]. IL-28-treated DC acquire a phenotype characterized by the high expression of MHC I and II, but downregulate costimulatory molecules; these IL-28-treated DC have been shown to promote IL-2-dependent proliferation of Treg [41]. Thus, these results show that IL-28 exhibits anti-encephalitogenic potential when produced by regulatory T cells.

Interestingly, an upregulation of CD73 by Foxp3+ T cells was observed after treatment with MOG-pσ1. CD73 (ecto-5′-nucelotidase) is an enzyme that catalyzes dephosporylation of purine and pyrimidine ribo- and deoxyribonucleoside monophosphates to their corresponding nucleotides [42] and can mediate costimulatory signaling for T-cell activation and/or be required for the penetration through the blood brain barrier [43]. Recently, CD73, together with another ecto-nucleotidase, CD39, which converts ATP into AMP, has been implicated in the suppressive function of Treg [43, 44].

In summary, these studies further demonstrate that the genetic modification of pσ1 renders it tolerogenic to both the fused protein Ag [15, 16] and itself [15]. The advancement of this tolerance platform allows the development of strategies based upon pσ1-mediated interventions that can be ubiquitously applied to treat other autoimmune diseases. This is evident here by showing that a single nasal dose of MOG-pσ1 confers complete protection against EAE, unlike rMOG or other unrelated pσ1 fusion proteins. Protection by MOG-pσ1 was due to induction of MOG-specific tolerance mediated by IL-10-secreting Foxp3+ Treg and supported by IL-4-producing CD25−CD4+ T cells, both of which showed enhanced expression of ecto-5′ nucleotidase CD73. Both T-cell subsets also produced varying amounts of IL-28. As a consequence of these regulatory/Th2 cell subsets, MOG-pσ1 markedly reduced the expansion of encephalitogenic CD4+ T cells, inhibiting the production of proinflammatory Th1- and Th17-type cytokines. Interestingly, mice dosed with MOG-pσ1 showed a dramatic increase in the number of Treg infiltrating the CNS. Remarkably, the treatment of mice at the peak of EAE with a single nasal dose of MOG-pσ1 resulted in dramatic and immediate remission from EAE, eventually making a pσ1-based system very attractive for inducing tolerance as a treatment against a wide variety of autoimmune diseases.

Materials and methods

Preparation of MOG-pσ1 and r MOG

Protein σ1 and PLP:OVA-pσ1 were prepared, as previously described [15, 16]. To generate MOG-pσ1 fusion protein, a synthetic gene encoding extracellular domain (amino acids 29–146) of murine MOG [45] was synthesized (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ) and framed upstream of pPICσ1-1, a yeast his-tag expression cassette featuring the whole pσ1 coding region. The junction between the MOG and pσ1 featured a flexible linker (Pro-Gly) to minimize steric hindrance between the components. To produce rMOG, MOG29–146 was amplified and cloned into pPICB vector as an EcoRI-Kpn fragment. Constructs were sequenced, expressed in the yeast Pichia pastoris, and recombinant proteins were extracted and purified, as previously described [15, 16]. Proteins were assessed for purity and quality by Coomassie-stained polyacrylamide gels and by Western blot analysis, using a anti-His-tag mAb (Invitrogen) or a polyclonal rabbit anti-pσ1 Ab (produced in-house).

Mice

Female six-week-old C57BL/6N mice (Frederick Cancer Research Facility, National Cancer Institute; Frederick, MD) were used throughout the study. IL-10−/− mice breeder pairs were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory to establish our breeding colony. All mice were maintained at the Montana State University Animal Resources Center under pathogen-free conditions in individual ventilated cages under HEPA-filtered barrier conditions and were fed sterile food and water ad libitum. All animal care and procedures were in accordance with institutional policies for animal health and well-being.

MOG-pσ1-based therapies and EAE induction

Mice were given nasally a single 50 μg dose of MOG-pσ1, as described in the text. For EAE, mice were challenged s.c. in flank with 150 μg of MOG35–55 peptide in 100 μl of CFA (Sigma-Aldrich) containing 4 mg/mL Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Difco Laboratories,, Detroit, MI, USA) on day 0. On day 7, mice received a second 150 μg dose of MOG35–55 peptide in CFA containing 1.5 mg/mL of M. tuberculosis. On days 0 and 2, mice received i.p. 200 ng of Bordetella pertussis toxin (List Biological Laboratories, Campbell, CA) [10]. Mice were monitored and scored daily for disease progression [19, 20]: 0, normal; 1, a limp tail; 2, hind limb weakness; 3, hind limb paresis; 4, quadriplegia; 5, death.

Ab ELISA

Serum sample collection was performed, as previously described [15]. rMOG-specific endpoint Ab titers were measured by ELISA, as previously described [15], using 5.0 μg of purified rMOG as coating Ag. Specific reactivity to rMOG was determined using HRP conjugates of goat anti-mouse IgG- and IgA-specific Abs (1.0 μg/mL; Southern Biotechnology Associates; Birmingham, AL), and ABTS (Moss, Pasadena, CA) enzyme substrate. The absorbances were measured at 415 nm on a Kinetics Reader model ELx808 (Bio-Tek Instruments).

Measurement of DTH responses

To measure MOG35–55-specific DTH responses in vivo [15], 10 μg of MOG35–55 in 20 μL were injected into the left ear pinna, and PBS alone (20 μL) was administered to the right ear pinna as a control. Ear swelling was measured 24 h later with an electronic digital caliper. The DTH response was calculated as the increase in ear swelling after Ag injection following subtraction of swelling in the control site injected with PBS.

Isolation of mononuclear cells from CNS

Spinal cords were flushed out by hydrostatic pressure from saline perfused mice. The tissue was homogenized in cold HBSS buffer with the plunger of a syringe, filtered through a 70 mm cell strainer to obtain a single cell suspension, and centrifuged; pellets from 4 to 5 mice were pooled, resuspended in 70% Percoll, and overlaid with 30% Percoll. After centrifugation at 1000 × g for 25 min, the cell monolayer at the interphase was collected for flow cytometric staining.

CD4+ T-cell analyses and adoptive transfer

Spleens, MLNs, and HNLNs were removed 18–21 days after EAE induction from PBS-, MOG-pσ1-, and rMOG-dosed mice. Lymphocytes, as previously described [15, 16], were resuspended in complete medium (CM) and cultured in 24-well tissue plates at 5 × 106 cells/ml in complete medium alone or in the presence of MOG35–55 (30 μg/mL) for 3–5 days at 37°C. Bead-isolated CD4+, CD25+CD4+, or CD25−CD4+ T cells isolated to >95% purity were cultured for the total of 3 days in the presence of 1:1 ratio of T-cell-depleted splenic feeder cells with or without Ag restimulation [16]. To assess cytokine production by Treg following MOG-pσ1 intervention, CD25+CD4+ and CD25−CD4+ T cells (2 × 105/mL) were stimulated in vitro with anti-CD3 mAb-coated wells (10 μg/mL; BD Pharmingen) and soluble anti-CD28 mAb (5 μg/mL; BD Pharmingen) for 3 days. Capture ELISA was employed to quantify the levels of IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-13, IL-17, IL-21, IL-28, and TGF-β produced by lymphocytes, as previously described [16].

To assess Treg function, 1 × 105 purified CD4+ T cells were restimulated with 20 μg/mL MOG35–55 in the presence of equal number of irradiated feeder cells for 4 days, and cultures were pulsed with 1.0 μCi/well [3H]-thymidine during the last 12 h of culture. Incorporated radioactivity in harvested samples was measured as previously described [22].

To assess resortative capacity of WT Treg and Th2 cells in IL-10−/− mice, WT mice were dosed with MOG-pσ1, and their total CD4+ T cells from spleens, HNLNs, and MLNs were obtained (negative CD4+ T cell isolation kit, Dynal Biotech ASA, Oslo, Norway). CD25+CD4+ and CD25−CD4+ T cells were further isolated from total CD4+ T cells with >94 and 97% purity, respectively, by positive selection using CELLection Biotin Binder Kit (Dynal Biotech; Invitrogen) and biotin-conjugated anti-mouse CD25 mAb (clone PC61; eBioscience; San Diego, CA), according to the manufacture’s instructions. These purified T-cell subsets were subsequently adoptively transferred with 6 × 105 Treg or CD25−CD4+ T cells by i.v. injection into IL-10−/− recipients with EAE at peak of disease.

FACS analysis

Single-cell lymphocyte suspensions were prepared, as described above. Cells were stained for FACS analysis using conventional methods. T-cell subsets were analyzed using fluorochrome-conjugated mAbs for CD4, CD25, B220, CTLA-4 (all from BD Pharmingen), and PE-conjugated CD73 (eBioscience), and biotinylated TGF-β (R&D Systems). Purified rabbit polyclonal CD39 Ab was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology and biotinylated in-house. Intracellular staining for Foxp3 was accomplished using FITC-, PE-Cy5-, or PE-anti-Foxp3 mAb (clone FJK-16s; eBioscience); intracellular or staining for IL-4 or IL-10 was accomplished using PE- or APC-anti-IL-10 or anti-IL-4 mAbs (all from BD Pharmingen).

Statistical analysis

The ANOVA followed by the posthoc Tukey test was applied to show differences in clinical scores and variations in Ab and cytokine level production in treated versus PBS mice. Mann–Whitney U test was used for statistical analysis of DTH response; p-values <0.05 are indicated.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms Nancy Kommers for her assistance in preparing this manuscript. This work is supported by U.S. Public Health Service Grant R01 AI-078938 and, in part, by Montana Agricultural Station and U.S. Department of Agriculture Formula Funds. Department of Immunology & Infectious Diseases’ flow cytometry facility was, in part, supported by the NIH/National Center for Research Resources, Centers of Biomedical Excellence P20 RR-020185, and an equipment grant from the M. J. Murdock Charitable Trust.

Abbreviations

- DTH

delayed-type hypersensitivity

- HNLNs

head and neck lymph nodes

- MLNs

mesenteric LNs

- MOG

myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein

- p.ch

post-challenge

- pσ1

protein sigma one

- rMOG

recombinant MOG

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Correale J, Farez M, Gilmore W. Vaccines for multiple sclerosis: progress to date. CNS Drugs. 2008;22:175–198. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200822030-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gold R, Linington C, Lassmann H. Understanding pathogenesis and therapy of multiple sclerosis via animal models: 70 years of merits and culprits in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis research. Brain. 2006;129:1953–1971. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuchroo VK, Anderson AC, Waldner H, Munder M, Bettelli E, Nicholson LB. T cell response in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE): role of self and cross-reactive antigens in shaping, tuning, and regulating the autopathogenic T cell repertoire. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:101–123. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.081701.141316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cua DJ, Sherlock J, Chen Y, Murphy CA, Joyce B, Seymour B, Lucian L, et al. Interleukin-23 rather than interleukin-12 is the critical cytokine for autoimmune inflammation of the brain. Nature. 2003;421:744–748. doi: 10.1038/nature01355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang DR, Wang J, Kivisakk P, Rollins BJ, Ransohoff RM. Absence of monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 in mice leads to decreased local macrophage recruitment and antigen-specific T helper cell type 1 immune response in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 2001;193:713–726. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.6.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Budingen HC, Tanuma N, Villoslada P, Ouallet JC, Hauser SL, Genain CP. Immune responses against the myelin/oligodendrocyte glycoprotein in experimental autoimmune demyelination. J Clin Immunol. 2001;21:155–170. doi: 10.1023/a:1011031014433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McColl SR, Staykova MA, Wozniak A, Fordham S, Bruce J, Willenborg DO. Treatment with anti-granulocyte antibodies inhibits the effector phase of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 1998;161:6421–6426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nygardas PT, Maatta JA, Hinkkanen AE. Chemokine expression by central nervous system resident cells and infiltrating neutrophils during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in the BALB/c mouse. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:1911–1918. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200007)30:7<1911::AID-IMMU1911>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ransohoff RM, Kivisakk P, Kidd G. Three or more routes for leukocyte migration into the central nervous system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:569–581. doi: 10.1038/nri1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hofstetter HH, Ibrahim SM, Koczan D, Kruse N, Weishaupt A, Toyka KV, Gold R. Therapeutic efficacy of IL-17 neutralization in murine experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Cell Immunol. 2005;237:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Komiyama Y, Nakae S, Matsuki T, Nambu A, Ishigame H, Kakuta S, Sudo K, et al. IL-17 plays an important role in the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2006;177:566–573. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park H, Li Z, Yang XO, Chang SH, Nurieva R, Wang YH, Wang Y, et al. A distinct lineage of CD4 T cells regulates tissue inflammation by producing interleukin 17. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1133–1141. doi: 10.1038/ni1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steinman L. A brief history of T(H)17, the first major revision in the T(H)1/T(H)2 hypothesis of T cell-mediated tissue damage. Nat Med. 2007;13 :139–145. doi: 10.1038/nm1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sutton C, Brereton C, Keogh B, Mills KH, Lavelle EC. A crucial role for interleukin (IL)-1 in the induction of IL-17-producing T cells that mediate autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1685–1691. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rynda A, Maddaloni M, Mierzejewska D, Ochoa-Repáraz J, Maslanka T, Crist K, Riccardi C, et al. Low-dose tolerance is mediated by the microfold cell ligand, reovirus protein sigma1. J Immunol. 2008;180:5187–5200. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rynda A, Maddaloni M, Ochoa-Repáraz J, Callis G, Pascual DW. IL-28 supplants requirement for Treg cells in protein sigma1-mediated protection against murine experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) PLoS One. 2010;5:e8720. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stephens LA, Malpass KH, Anderton SM. Curing CNS autoimmune disease with myelin-reactive Foxp3+ Treg. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:1108–1117. doi: 10.1002/eji.200839073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jun S, Gilmore W, Callis G, Rynda A, Haddad A, Pascual DW. A live diarrheal vaccine imprints a Th2 cell bias and acts as an anti-inflammatory vaccine. J Immunol. 2005;175:6733–6740. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ochoa-Repáraz J, Riccardi C, Rynda A, Jun S, Callis G, Pascual DW. Regulatory T cell vaccination without autoantigen protects against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2007;178:1791–1799. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ochoa-Repáraz J, Rynda A, Ascón MA, Yang X, Kochetkova I, Riccardi C, Callis G, et al. IL-13 production by regulatory T cells protects against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis independently of autoantigen. J Immunol. 2008;181:954–968. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.2.954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Endharti AT, Rifa IM, Shi Z, Fukuoka Y, Nakahara Y, Kawamoto Y, Takeda K, et al. Cutting edge: CD8+CD122+ regulatory T cells produce IL-10 to suppress IFN-γ production and proliferation of CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:7093–7097. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kochetkova I, Golden S, Holderness K, Callis G, Pascual DW. IL-35 stimulation of CD39+ regulatory T cells confers protection against collagen II-induced arthritis via the production of IL-10. J Immunol. 2010;184:7144–7153. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kochetkova I, Trunkle T, Callis G, Pascual DW. Vaccination without autoantigen protects against collagen II-induced arthritis via immune deviation and regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2008;181:2741–2752. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rifa’i M, Kawamoto Y, Nakashima I, Suzuki H. Essential roles of CD8+CD122+ regulatory T cells in the maintenance of T cell homeostasis. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1123–1134. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiner HL. Oral tolerance: immune mechanisms and the generation of Th3-type TGF-β-secreting regulatory cells. Microbes Infect. 2001;3:947–954. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(01)01456-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujihashi K, Dohi T, Rennert PD, Yamamoto M, Koga T, Kiyono H, McGhee JR. Peyer’s patches are required for oral tolerance to proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:3310–3315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061412598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suzuki H, Sekine S, Kataoka K, Pascual DW, Maddaloni M, Kobayashi R, Fujihashi K, et al. Ovalbumin-protein sigma 1 M-cell targeting facilitates oral tolerance with reduction of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:917–925. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Denic A, Johnson AJ, Bieber AJ, Warrington AE, Rodriguez M, Pirko I. The relevance of animal models in multiple sclerosis research. Pathophysiology. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Faria AM, Maron R, Ficker SM, Slavin AJ, Spahn T, Weiner HL. Oral tolerance induced by continuous feeding: enhanced up-regulation of transforming growth factor-beta/interleukin-10 and suppression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Autoimmun. 2003;20:135–145. doi: 10.1016/s0896-8411(02)00112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Faria AM, Weiner HL. Oral tolerance: therapeutic implications for autoimmune diseases. Clin Dev Immunol. 2006;13:143–157. doi: 10.1080/17402520600876804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun JB, Rask C, Olsson T, Holmgren J, Czerkinsky C. Treatment of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by feeding myelin basic protein conjugated to cholera toxin B subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7196–7201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yuki Y, Byun Y, Fujita M, Izutani W, Suzuki T, Udaka S, Fujihashi K, et al. Production of a recombinant hybrid molecule of cholera toxin-B-subunit and proteolipid-protein-peptide for the treatment of experimental encephalomyelitis. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2001;74:62–69. doi: 10.1002/bit.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Legge KL, Gregg RK, Maldonado-Lopez R, Li L, Caprio JC, Moser M, Zaghouani H. On the role of dendritic cells in peripheral T cell tolerance and modulation of autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2002;196:217–227. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu P, Gregg RK, Bell JJ, Ellis JS, Divekar R, Lee HH, Jain R, et al. Specific T regulatory cells display broad suppressive functions against experimental allergic encephalomyelitis upon activation with cognate antigen. J Immunol. 2005;174:6772–6780. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aspord C, Thivolet C. Nasal administration of CTB-insulin induces active tolerance against autoimmune diabetes in non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;130:204–211. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01988.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bettelli E, Das MP, Howard ED, Weiner HL, Sobel RA, Kuchroo VK. IL-10 is critical in the regulation of autoimmune encephalomyelitis as demonstrated by studies of IL-10- and IL-4-deficient and transgenic mice. J Immunol. 1998;161:3299–3306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Neill EJ, Day MJ, Wraith DC. IL-10 is essential for disease protection following intranasal peptide administration in the C57BL/6 model of EAE. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;178:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harrington LE, Hatton RD, Mangan PR, Turner H, Murphy TL, Murphy KM, Weaver CT. Interleukin 17-producing CD4+ effector T cells develop via a lineage distinct from the T helper type 1 and 2 lineages. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1123–1132. doi: 10.1038/ni1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moore KW, O’Garra A, de Waal Malefyt R, Vieira P, Mosmann TR. Interleukin-10. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:165–190. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.001121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skapenko A, Kalden JR, Lipsky PE, Schulze-Koops H. The IL-4 receptor α-chain-binding cytokines, IL-4 and IL-13, induce forkhead box P3-expressing CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells from CD4+CD25− precursors. J Immunol. 2005;175:6107–6116. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.6107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mennechet FJ, Uze G. Interferon-λ-treated dendritic cells specifically induce proliferation of FOXP3-expressing suppressor T cells. Blood. 2006;107:4417–4423. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thompson LF, Ruedi JM, Glass A, Low MG, Lucas AH. Antibodies to 5′-nucleotidase (CD73), a glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol-anchored protein, cause human peripheral blood T cells to proliferate. J Immunol. 1989;143:1815–1821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mills JH, Thompson LF, Mueller C, Waickman AT, Jalkanen S, Niemela J, Airas L, et al. CD73 is required for efficient entry of lymphocytes into the central nervous system during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9325–9330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711175105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dwyer KM, Deaglio S, Gao W, Friedman D, Strom TB, Robson SC. CD39 and control of cellular immune responses. Purinergic Signal. 2007;3:171–180. doi: 10.1007/s11302-006-9050-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Linares D, Echevarria I, Mana P. Single-step purification and refolding of recombinant mouse and human myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein and induction of EAE in mice. Protein Expr Purif. 2004;34:249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]