Abstract

Background

Type 2 diabetes has been described a coronary heart disease (CHD) “risk equivalent”. We tested whether cardiovascular and all-cause mortality rates were similar between participants with prevalent CHD versus diabetes in an older adult population in whom both glucose disorders and pre-existing atherosclerosis are common.

Methods

The Cardiovascular Health Study is a longitudinal study of men and women (n= 5784) aged ≥65 years at baseline who were followed from baseline (1989/92-93) through 2005 for mortality. Diabetes was defined by fasting plasma glucose ≥7.0 mmol/L or use of diabetes control medications. Prevalent CHD was determined by confirmed history of myocardial infarction (MI), angina, or coronary revascularization.

Results

Following multivariable adjustment for other cardiovascular disease risk factors and subclinical atherosclerosis, CHD mortality risk was similar between participants with CHD alone vs. diabetes alone (hazard ratio [HR]=1.04, 95% CI, 0.83-1.30). The proportion of mortality attributable to prevalent diabetes (Population Attributable Risk Percent =8.4%) and prevalent CHD (6.7%) was similar in women, but the proportion of mortality attributable to CHD (16.5%) as compared with diabetes (6.4%) was markedly higher in men. Patterns were similar for cardiovascular disease mortality. By contrast, the adjusted relative hazard of total mortality was lower among participants with CHD alone (HR =0.85, 95% CI, 0.75-0.96) as compared with those who had diabetes alone.

Conclusions

Among older adults, diabetes alone confers a similar risk for cardiovascular mortality as established clinical CHD. The public health burden of both diabetes and CHD is substantial, particularly among women.

Keywords: type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, longitudinal studies, older adults

Coronary heart disease is the leading cause of death in persons with diabetes. Insulin resistance, a defining feature of type 2 diabetes, is associated with a cluster of metabolic and biochemical abnormalities including hyperglycemia, hypertension, atherogenic dyslipidemia, inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and impaired fibrinolysis.1 Each of these abnormalities promotes the development of atherosclerosis and clinical cardiovascular diseases. Longitudinal epidemiologic studies report a similar incidence of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality between persons who have diabetes without evidence of prior coronary heart disease and persons who have coronary heart disease without prior diabetes.2-6 As a result, diabetes is often termed a coronary heart disease “risk equivalent”. However, the growing incidence of type 2 diabetes in young adults and adolescents7 requires that any claims about diabetes as a coronary heart disease risk equivalent be qualified by the age of the affected person.

Determining whether diabetes in a coronary heart disease risk equivalent in older adults who have a high prevalence of glucose disorders as well as subclinical coronary heart disease is particularly important because guidelines by the American Diabetes Association8, the National Cholesterol Education Program9 and others recommend aggressive treatment of cardiovascular risk factors in persons with diabetes. While therapies available to treat the major risk factors for coronary heart disease are generally safe and effective, older adults are disproportionate consumers of prescription as well as over the counter medications.10 Because of the substantial financial burden imposed by the use of multiple medications and the challenges associated with managing a complicated pharmacologic regimen, recommendations to add additional medications should be scientifically justified.

The objective of our study was to test whether diabetes was a coronary heart disease “risk equivalent” in older (age≥65 years) adults. We tested the hypothesis that mortality from coronary heart disease, total cardiovascular disease (including stroke), and all-causes was similar in older adults who have prevalent diabetes but no coronary heart disease (“diabetes alone”) as compared with older adults who were free from prevalent diabetes (“coronary heart disease alone”). We investigated whether any observed differences persisted once we accounted for comorbid cardiovascular risk factors—including the prevalence of subclinical cardiovascular disease.11, 12 Finally, to assess the public health burden of both conditions, we calculated the fraction of mortality that could theoretically be attributed to prevalent diabetes and prevalent coronary heart disease, assuming the associations are causal (i.e., population attributable risk percent).13

Methods

The Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) is a prospective cohort study of risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke in men and women aged ≥65 years at baseline. Between 1989 and 1990, eligible adults were identified by randomly sampling Medicare eligibility lists in 4 US communities (Sacramento, CA, Baltimore, MD, Forsyth County, NC and Pittsburg, PA). Among eligible adults, 57% or 5201 participants (57% women) enrolled. Using similar recruitment procedures in 1992-93, 687 black participants were added to the original sample resulting in a cohort that was 18% black overall (n = 931). Clinical examinations took place in1989-90 and annually thereafter through 1999. Details of CHS recruitment and design are published.14, 15 Institutional review board approval was obtained at each of the participating institutions and the coordinating center. Participants on whom prevalent diabetes status could not be determined due to missing information on blood glucose levels (n=64) or diabetes medication use (n=6), or missing or inadequate fasting times (n=34) at baseline, were excluded from this analysis. The final analysis sample included 5,784 participants.

Measurements

The baseline examination included a home interview and detailed clinic physical examination. Participants completed standardized questionnaires and interviews to assess demographic characteristics, cardiovascular disease risk factors, and lifestyle risk factors.14, 16 Medications were assessed by inventory.17 Following a 9-hour fast, seated blood pressure, electrocardiography (ECG), venipuncture and anthropometric measures were collected using standard procedures and equipment. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP, respectively) was measured in duplicate and averaged. Hypertension was defined as SBP≥140 mmHg or DBP≥90 mmHg or a physician diagnosis of hypertension plus the use of antihypertensive medications. Plasma and serum were frozen at −70° C and shipped to the CHS Central Laboratory (University of Vermont, Burlington, VT) for analysis and processed according to standard methods.18 Cystatin-based estimates of glomerular filtration rate (eGFRcys) were calculated as 76.7 × cystatin C-1.18.19 Participants who were free from prevalent clinical cardiovascular disease were identified as having subclinical disease if they had any of the following measurements: ankle-brachial index <0.9; internal carotid artery wall thickness >80th percentile; common carotid wall thickness >80th percentile; carotid stenosis >25%; major ECG abnormalities based on Minnesota code; and Rose questionnaire positive for claudication or angina in the absence of a clinical diagnosis of angina or claudication.11, 12

Prevalent Diabetes and coronary heart disease

Fasting serum glucose was measured at baseline in all participants without medically treated diabetes (Ektacham 700 Analyzer, Eastman Kodak Corp). Prevalent diabetes was defined based on fasting blood glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL (7 mmol/L), or use of oral hypoglycemic medication or insulin. Because the supplemental cohort of 687 black participants did not have a 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test, only fasting glucose levels and medication use are used to define diabetes in this study. We carried out one sensitivity analysis restricting the definition of prevalent diabetes to participants who were using medications in an attempt to reduce potential misclassification of participants who had a single randomly elevated fasting glucose. We carried out a second sensitivity analysis restricting the sample to the original cohort measured in 1989-90 who had an oral glucose challenge.

Methods for diagnosing prevalent coronary heart disease at baseline have been described. In brief, prevalent coronary heart disease was defined as any of the following: validated physician-diagnosed myocardial infarction; history of coronary angioplasty or coronary artery bypass surgery; sublingual nitroglycerin use; or evidence of previous myocardial infarction based on the presence of major Q waves or the combination of minor Q waves and ST-T wave changes on ECG.16 We conducted secondary analyses defining prevalent coronary heart disease based only on prevalent myocardial infarction.

Mortality Ascertainment and Follow-Up

Mortality follow-up in this report is adjudicated through June 30, 2005. Participants (or their next of kin in the event of death) were contacted semi-annually by phone to report cardiovascular events and hospitalizations. Mortality was confirmed through reviews of obituaries, medical records, death certificates, and the Health Care Financing Association health care utilization database for hospitalizations. Fatal coronary heart disease was identified if participants had chest pain within 72 hours of death or a history of ischemic heart disease on their abstracted medical record. Total cardiovascular disease mortality included the following: fatal coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease or other atherosclerotic vascular disease. All cause mortality was determined as death from all causes including coronary heart disease. Follow-up time was calculated as the difference between the baseline visit and the last known contact, death or June 30, 2005.

Analysis

Participants were categorized into 4 groups based on prevalent diabetes and coronary heart disease status at baseline: (1) no diabetes or coronary heart disease, (2) diabetes alone, (3) coronary heart disease alone, and (4) both coronary heart disease and diabetes. Means and standard deviations (SD) or proportions of participant demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline were evaluated by these 4 categories of prevalent disease status. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used to display the association of baseline disease status with fatal coronary heart disease, total cardiovascular disease mortality, and all-cause mortality. Prior to modeling, we tested for heterogeneity in the association of prevalent disease with each mortality outcome by sex and race, by evaluating the statistical significance of multiplicative interaction terms in models that also included lower order terms. We found no evidence of significant statistical interaction and so tabulated analyses are presented pooled by sex and race.

We used multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression to model the association between baseline disease status and mortality. Model 1 was adjusted for age at baseline, sex, race, education, physical activity levels, BMI, hypertension status, smoking status (current vs. never and former vs. never), total cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol. Model 2 was adjusted additionally for our composite measure of subclinical atherosclerosis. To be consistent with research conducted by Evans et al20 and Lee et al,21 we evaluated CHS participants with diabetes alone as the referent group, allowing for direct and easily interpretable comparisons between the 2 groups of interest for our hypothesis testing: participants with diabetes alone vs. participants with coronary heart disease alone. Analyses were repeated using prevalent myocardial infarction in place of prevalent coronary heart disease. To explore the impact of potential misclassification of diabetes arising from relying solely on fasting glucose and medication use, we repeated the analyses after restricting to the 4,992 participants in the original cohort who could be additionally classified on the basis of an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) performed in 1989-90. In these analyses, participants were considered to have diabetes if they had a 2-hour blood glucose level of ≥200mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L), a fasting glucose level ≥ 126 mg/dL (7 mmol/L), or reported use of oral hypoglycemic medication or insulin. To assess the public health burden of prevalent diabetes and coronary heart disease, we estimated the proportions of coronary heart disease, cardiovascular disease, and all-cause mortality potentially attributable to combinations of prevalent diabetes and coronary heart disease by calculating population attributable risk proportions. For each outcome, population attributable risk proportion (PAR%) was calculated as: pd(RR-1/RR), where pd is the proportion of cases exposed and RR is the relative risk estimated by a Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for age, race, sex, education, physical activity levels, BMI, hypertension status, smoking status (current vs. never and former vs. never), total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol and subclinical atherosclerosis.13 Confidence intervals for PAR%s were calculated using the bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method with 1,000 replications.22 Statistical significance for all analyses was determined at two-tailed p<0.05. All analyses were conducted using STATA version 10.0 (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX).

Results

At baseline, 3,997 participants were free from both prevalent coronary heart disease and diabetes (69.1%), 868 (15%) had coronary heart disease alone, 659 (11.4%) had diabetes alone, and 260 (4.5%) had both diabetes and coronary heart disease (Table 1). As compared with participants who had diabetes alone, participants with coronary heart disease alone were older, and smaller proportions of participants were female and black. The distribution of cardiovascular disease risk factors varied by prevalent disease status; the only consistent pattern was that participants having neither diabetes nor coronary heart disease had the most favorable risk factor profile. The prevalence of subclinical atherosclerosis was highest among participants with coronary heart disease (88% in those with coronary heart disease and concurrent diabetes; 85% with coronary heart disease alone), followed by participants with diabetes alone (77%) and lowest in participants with neither (61%).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Population Stratified by Prevalent Diabetes/Coronary Heart Disease Status.

| No Diabetes/No Coronary Heart Disease | Diabetes alone | Coronary Heart Disease alone | Coronary Heart Disease and Diabetes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 3,997 | 659 | 868 | 260 |

| Age, years | 72.5 ± 5.5 | 72.9 ± 5.5 | 74.1 ± 5.8 | 72.6 ± 5.3 |

| Sex (% female) | 61.5 | 53.4 | 46.5 | 43.9 |

| Race (% black) | 13.6 | 25.8 | 13.4 | 20.4 |

| Education (% < high school education) | 26.7 | 37.1 | 32.8 | 36.1 |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Current (%) | 12.6 | 10.9 | 10.8 | 7.7 |

| Former (%) | 40.1 | 41.3 | 46.7 | 51.2 |

| Physical activity (kcal/wk) | 1190.8 ± 1574.6 | 1050.0 ± 1569.0 | 1171.3 ± 1581.4 | 1082.3 ± 1782.7 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.3 ± 4.6 | 28.8 ± 5.0 | 26.4 ± 4.5 | 28.2 ± 4.9 |

| Hypertension (%) | 54.2 | 72.1 | 63.4 | 72.3 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 135.7 ± 21.5 | 142.1 ± 21.7 | 135.9 ± 22.9 | 135.8 ± 20.9 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 71.0 ± 11.2 | 72.0 ± 12.0 | 69.4 ± 11.7 | 67.6 ± 11.1 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 212.5 ± 38.1 | 207.2 ± 43.6 | 210.8 ± 39.8 | 201.0 ± 40.3 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 56.5 ± 16.0 | 48.4 ± 12.8 | 51.0 ± 14.7 | 44.8 ± 13.5 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 130.1 ± 35.0 | 126.3 ± 38.8 | 132.8 ± 35.0 | 123.0 ± 37.1 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 115 (89-154) | 146 (104-201) | 123 (94-162) | 150 (112-210) |

| Fibrinogen, mg/dL | 319.9 ± 64.3 | 333.5 ± 74.9 | 328.9 ± 68.4 | 345.2 ± 78.6 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 2.3 (1.2-4.1) | 3.5 (2.0-7.3) | 2.8 (1.3-4.7) | 3.8 (2.2-9.0) |

| White blood cell, count | 6.1 ± 1.9 | 6.8 ± 2.9 | 6.5 ± 2.2 | 7.2 ± 2.3 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 14.0 ± 1.4 | 14.2 ± 1.5 | 14.1 ± 1.5 | 14.1 ± 1.6 |

| eGFR cystatin, ml/min/1.73 m2 | 79.3 ± 18.8 | 77.5 ± 22.1 | 72.2 ± 19.5 | 70.5 ± 21.7 |

| Subclinical Cardiovascular Disease (%) | 61 | 77 | 85 | 88 |

IQR = interquartile range

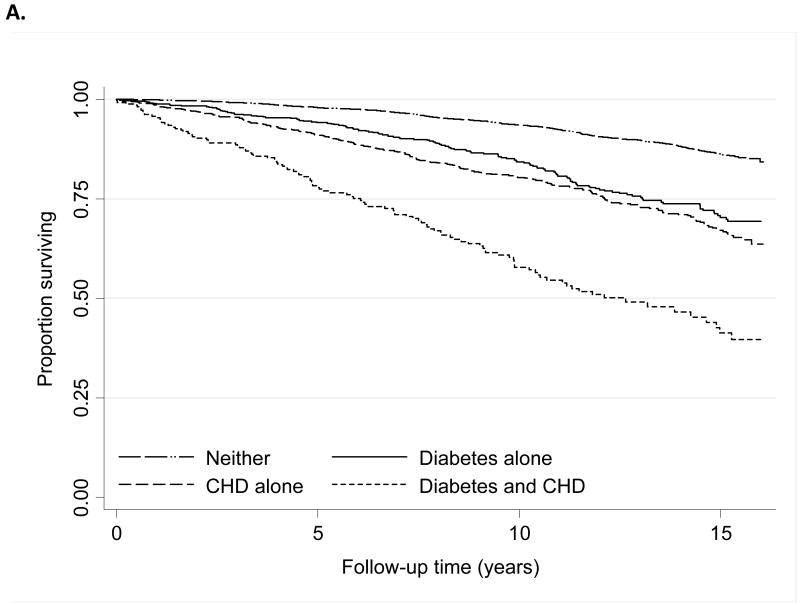

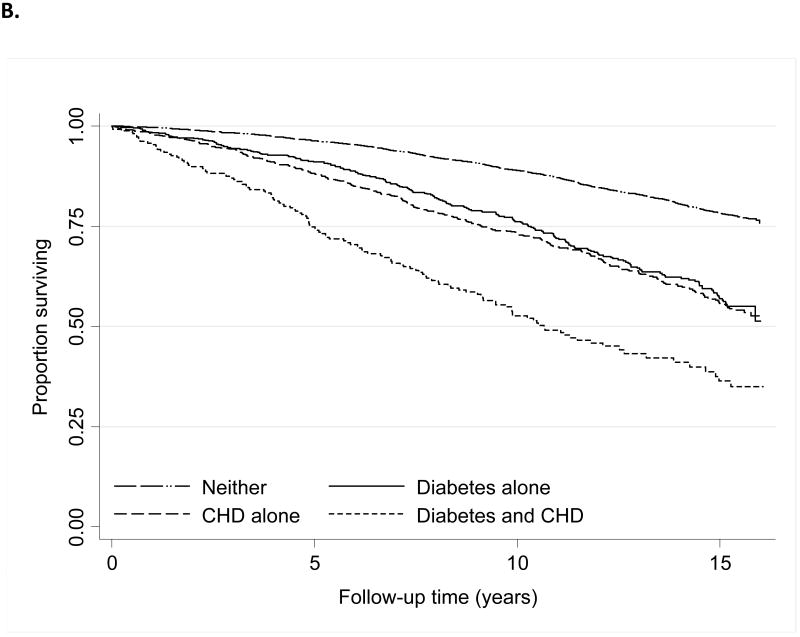

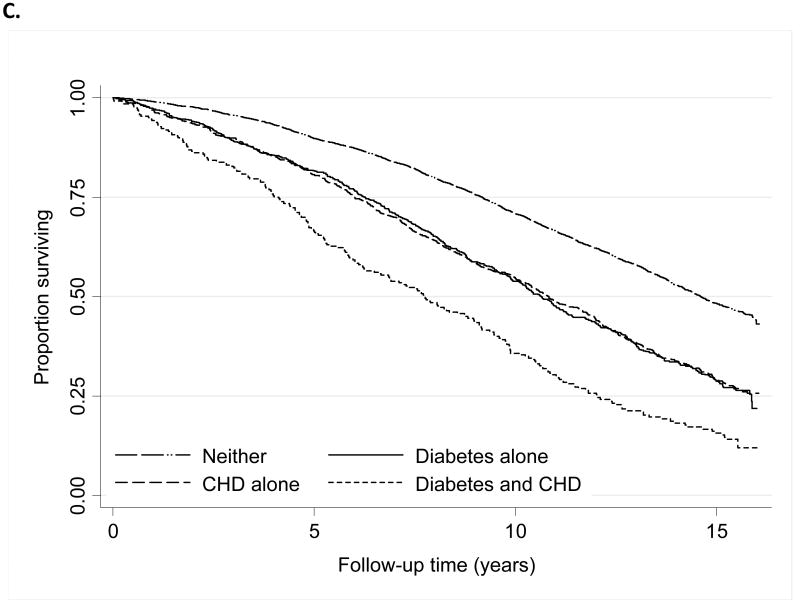

Over a mean follow-up of 11.3 years, 881 (15%), 1354 (23%), and 3402 (59%) participants experienced mortality from fatal coronary heart disease, all cardiovascular causes, and all causes, respectively. Kaplan-Meier curves of survival by prevalent disease category display the most favorable survival among participants free from diabetes and coronary heart disease, intermediate for participants with either diabetes or coronary heart disease alone, and lowest among participants with coronary heart disease and diabetes (Figure 1). We observed similar patterns by sex (data not shown).

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier Association of baseline prevalent diabetes and coronary heart disease status with mortality from Coronary Heart Disease (A), Cardiovascular Disease (B) and Total Mortality (C).

Crude mortality rates for each mortality outcome were similar between participants with diabetes alone and coronary heart disease alone (Table 2). Following adjustment for baseline demographic characteristics, health behaviors, comorbid cardiovascular disease risk factors and subclinical atherosclerosis differences in coronary heart disease or cardiovascular disease mortality between participants with coronary heart disease alone and diabetes alone were not statistically significant. However, the adjusted all-cause mortality hazard ratio was lower among participants with coronary heart disease alone, as compared with diabetes alone. Additional adjustment for CRP and serum creatinine resulted in little additional change in the hazard ratio comparing participants with coronary heart disease alone to those with diabetes alone (HR=0.84, 95% CI, 0.74, 0.95).

Table 2. Association between Baseline Diabetes/Coronary Heart Disease Status and Mortality.

| No Diabetes/No Coronary Heart Disease (n=3997) | Diabetes alone (n=659)* | Coronary Heart Disease alone (n=868) | Diabetes and Coronary Heart Disease (n=260) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coronary Heart Disease Mortality | ||||

| No Events | 425 | 132 | 213 | 111 |

| Rate per 1000 Person-Years | 8.9 | 20.1 | 24.5 | 53.7 |

| Unadjusted † | 0.41 (0.34-0.50) | 1.0 | 1.21 (0.97-1.50) | 2.88 (2.24-3.71) |

| Model 1‡ | 0.48 (0.39-0.59) | 1.0 | 1.08 (0.87-1.36) | 2.89 (2.23-3.74) |

| Model 2 | 0.52 (0.42-0.63) | 1.0 | 1.04 (0.83-1.30) | 2.73 (2.11-3.55) |

| Cardiovascular Disease Mortality | ||||

| No Events | 710 | 211 | 304 | 129 |

| Rate per 1000 Person-Years | 14.8 | 32.1 | 35.0 | 62.4 |

| Unadjusted | 0.43 (0.37-0.50) | 1.0 | 1.08 (0.90-1.28) | 2.10 (1.68-2.61) |

| Model 1 | 0.50 (0.43-0.59) | 1.0 | 0.99 (0.82-1.18) | 2.15 (1.72-2.69) |

| Model 2 | 0.53 (0.45-0.63) | 1.0 | 0.95 (0.79-1.14) | 2.05 (1.63-2.57) |

| Total Mortality | ||||

| No Events | 2095 | 468 | 620 | 219 |

| Rate per 1000 Person-Years | 43.8 | 71.3 | 71.3 | 105.9 |

| Unadjusted | 0.57 (0.51-0.63) | 1.0 | 0.99 (0.88-1.11) | 1.63 (1.39-1.91) |

| Model 1 | 0.61 (0.55-0.68) | 1.0 | 0.87 (0.77-0.99) | 1.66 (1.41-1.96) |

| Model 2 | 0.63 (0.57-0.70) | 1.0 | 0.85 (0.75-0.96) | 1.61 (1.36-1.90) |

Diabetes and no Coronary Heart Disease is the referent category (Hazard Ratio = 1.0)

Hazard ratio (95% Confidence interval)

Model 1: Adjusted for baseline age, sex, race, and education, physical activity, BMI, hypertension status, smoking status (current vs. never and former vs. never), total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol; Model 2: Adjusted for model 1 + subclinical atherosclerosis

Findings for each mortality outcome were similar in women and men (p interaction coronary heart disease mortality= 0.14; cardiovascular disease mortality=0.32; total mortality=0.88); thus indicating the absence of interaction. Among women, the adjusted hazard ratios comparing women with coronary heart disease alone vs. diabetes alone for coronary heart disease mortality (HR=0.78, 95% CI, 0.55-1.11) and cardiovascular disease mortality (HR=0.84, 95% CI, 0.64-1.11) did not differ significantly, whereas the HR for total mortality (HR=0.80, 95% CI, 0.67-0.97) was consistent with findings in the pooled sample that showed a slight protective association for women with coronary heart disease alone vs. diabetes alone. Among men, the hazard ratios for coronary heart disease, cardiovascular disease, and total mortality comparing men with coronary heart disease alone to those with diabetes alone were 1.23 (95% CI, 0.91, 1.66), 1.00 (95% CI, 0.78-1.28), and 0.90 (95% CI, 0.76-1.07), respectively.

When we repeated our analyses restricting prevalent coronary heart disease to the 49% of participants who had myocardial infarction only, we observed similar overall patterns of association in relation to cardiovascular disease mortality and total mortality (data not shown). However, myocardial infarction alone as compared with diabetes alone conferred a modest but statistically significantly elevated hazard for coronary heart disease mortality in unadjusted (HR=1.38, 95% CI, 1.09-1.74) and cardiovascular risk factor adjusted models (HR = 1.29, 95% CI, 1.01-1.64). Once subclinical atherosclerosis was included in the models, all statistically significant differences were eliminated (HR = 1.18, 95% CI, 0.93-1.50). There was again no evidence of statistical interaction by gender for any of the mortality outcomes (all interaction p values >0.25) and stratum specific estimates for women and men were similar.

Next, we restricted our analysis to the 4,992 participants in the original cohort who could be classified using the more stringent diabetes definition that included OGTTdata. There were 3,164 participants who were free from coronary heart disease and diabetes, 847 with diabetes alone, 682 with coronary heart disease alone and 299 with both diabetes and coronary heart disease. In models adjusted for baseline age, sex, race, education, physical activity, BMI, hypertension, smoking status, total and HDL cholesterol, the risk of coronary heart disease mortality was significantly higher among participants with coronary heart disease alone than among those with diabetes alone (HR=1.25, 95% CI, 1.00-1.56). However, when the index of subclinical atherosclerosis was added to the models, the hazard ratio attenuated to non-significance (HR=1.15, 95% CI, 0.91-1.43 for coronary heart disease alone vs. diabetes alone). All other patterns were the same as those presented in Table 2 in the full sample.

Population attributable risk percentages (PAR%), stratified by sex, are presented in Table 3. Among women, a similar proportion of coronary heart disease, cardiovascular disease and total mortality was attributable to prevalent diabetes alone vs. coronary heart disease alone. By contrast, a higher proportion of each mortality outcome was attributable to prevalent coronary heart disease as compared with prevalent diabetes among men. There was little difference for total mortality. When we restricted prevalent coronary heart disease to myocardial infarction only, prevalent diabetes accounted for nearly double the coronary heart disease mortality than did prevalent myocardial infarction (which was relatively less common). Among men, patterns were similar when prevalent coronary heart disease was restricted to myocardial infarction. There was no difference the proportion total mortality attributable to prevalent diabetes or coronary heart disease in men, but again prevalent diabetes appeared to make a larger contribution than myocardial infarction alone in women.

Table 3. Proportion of Mortality Attributable* to Prevalent Diabetes and Coronary Heart Disease or Myocardial Infarction.

| Women | Men | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes alone | Coronary Heart Disease alone | Diabetes and Coronary Heart Disease | Diabetes alone | Coronary Heart Disease alone | Diabetes and Coronary Heart Disease | |

| Coronary Heart Disease Mortality | 8.4 (4.0-11.9) | 6.7 (1.0-10.9) | 8.9 (6.2-11.7) | 6.4 (2.6-9.3) | 16.5 (10.7-20.9) | 11.2 (8.6-14.0) |

| Cardiovascular Disease Mortality | 6.9 (3.5-9.7) | 6.3 (1.8-9.5) | 5.6 (3.9-7.4) | 7.6 (4.5-10.3) | 13.3 (8.5-17.1) | 8.3 (6.2-10.5) |

| Total Mortality | 5.0 (3.1-6.7) | 3.5 (0.9-5.5) | 3.0 (2.0-3.9) | 5.0 (2.7-7.0) | 6.1 (3.1-9.0) | 4.7 (3.5-5.9) |

| Diabetes alone | Myocardial Infarction alone | Diabetes and Myocardial Infarction | Diabetes alone | Myocardial Infarction alone | Diabetes and Myocardial Infarction | |

|

| ||||||

| Coronary Heart Disease Mortality | 8.2 (3.8-11.7) | 4.8 (1.8-7.5) | 8.8 (6.1-11.7) | 5.6 (1.7-8.7) | 10.4 (7.0-13.7) | 10.9 (8.4-13.7) |

| Cardiovascular Disease Mortality | 6.6 (3.1-9.3) | 3.6 (1.3-5.7) | 5.5 (3.8-7.3) | 7.0 (3.7-9.7) | 8.4 (5.4-11.1) | 8.1 (5.9-10.3) |

| Total Mortality | 4.8 (2.9-6.5) | 1.6 (0.3-2.9) | 3.0 (2.0-3.8) | 4.8 (2.4-6.8) | 4.5 (2.6-6.1) | 4.6 (3.4-5.8) |

Population attributable risk percent calculated as: Pd(RR − 1)/(RR); RR=relative risk estimates from a Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for baseline age, race, education, physical activity, BMI, hypertension status, smoking status (current vs. never and former vs. never), total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol and subclinical atherosclerosis using no diabetes and no Coronary Heart Disease as the referent; Pd is the proportion of cases exposed.

Discussion

Our findings indicate that diabetes is a coronary heart disease risk equivalent for future cardiovascular mortality among older adults, but that prevalent coronary heart disease may present a lower risk for total mortality than prevalent diabetes. Restricting prevalent coronary heart disease to those with established myocardial infarction (i.e., excluding angina and coronary revascularization) demonstrated a relatively higher risk of future cardiovascular mortality. Prevalent diabetes accounted for a relatively equal proportion of coronary heart disease mortality in older women, thus making the “risk equivalency” argument even stronger in women than in men. Conversely, a larger proportion of mortality was attributable to prevalent coronary heart disease and prevalent myocardial infarction in men. Our findings are similar to those reported in middle-aged populations. While decreasing glucose tolerance is common with aging, the prevalence of diabetes in older adults is clearly not benign.

Prior studies, including one conducted in this cohort,23 have shown that prevalent diabetes confers a higher relative risk for mortality in women than in men.24 While the absence of statistically significant effect modification in the present analysis suggests that prevalent coronary heart disease and prevalent diabetes confer similar risks for future cardiovascular mortality in men and women, we do demonstrate that the public health burden associated with diabetes is relatively higher in women as compared with men. Due in large part to the higher prevalence of diabetes as compared with prevalent coronary heart disease or myocardial infarction in women, a roughly equal proportion of cardiovascular and total mortality is attributable to diabetes and coronary heart disease in women.

Differences in the association of prevalent coronary heart disease with mortality when prevalent disease is restricted to myocardial infarction suggests that disease severity underlies some of the differences previously noted in other cohorts. In a middle-aged sample from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study, prevalent myocardial infarction was associated with a 75 to 86% elevated risk of non-fatal or fatal coronary heart disease and cardiovascular disease mortality as compared with participants who had prevalent diabetes alone and no prior myocardial infarction;21 effect estimates for coronary heart disease including angina or revascularization were not reported. Adults who experience myocardial infarction, as compared with those who are intervened upon with procedures or who are experiencing symptomatic ischemia as angina may have less severe disease or slower progressing disease than their counterparts. We noted that the significant elevated risk of cardiovascular mortality was eliminated once we accounted for other cardiovascular risk factors and subclinical atherosclerosis.

Our findings demonstrate that older adults who have both diabetes and coronary heart disease have a uniquely elevated risk of mortality. A comparison of crude coronary heart disease mortality rates in persons with diabetes alone (20.1 per 1000 person-years), coronary heart disease alone (24.5 per 1000 person-years) or both (53.7 per 1000 person-years) suggest that the mortality rate in participants who have both conditions is greater than additive. By contrast, while mortality from all cardiovascular causes and all causes is elevated among participants with both diabetes and coronary heart disease at baseline that affect was not greater than what would have been expected based on the sum of both rates. Patterns were similar when prevalent myocardial infarction was studied. Older adults with both diabetes and coronary heart disease are at markedly elevated risk of experiencing mortality from coronary heart disease.

After accounting for additional demographic, behavioral and clinical cardiovascular disease risk factors, all-cause mortality was lower in participants with prevalent coronary heart disease alone, compared with diabetes alone. That we observed these differences after statistical adjustment for established cardiovascular risk factors suggests that the differences we observed are due to higher non-cardiovascular disease mortality in adults with diabetes. The elevated total mortality rate among older adults with diabetes as compared with those with coronary heart disease may be partially explained by inflammation and renal dysfunction.

Adults with diabetes are more likely to die from renal disease, certain cancers, and infections such as influenza and pneumonia than adults without diabetes.23, 25 Life expectancy for older adults (age>65 years) with diabetes is estimated to be 4 years shorter than adults without diabetes.26 The persistent statistically significant lowered hazard ratio in adults with coronary heart disease versus those with diabetes following adjustment for C-reactive protein and creatinine suggests that additional pathophysiologic processes may be associated with elevated mortality in persons with diabetes.

We did not have measures of duration of prevalent coronary heart disease or diabetes at baseline, so our findings reflect the average effect of these prevalent conditions in older adults. Newly diagnosed coronary heart disease and diabetes are likely to have different implications than longer standing disease. In a community sample of Scottish adults,20 those with an incident myocardial infarction during follow-up had an elevated risk of subsequent cardiovascular mortality (RR=2.93, 95% CI, 2.54-3.41) and all-cause mortality (RR=1.35, 95% CI, 1.25-1.44) compared with those newly diagnosed with diabetes, following adjustment for age and sex. The authors were unable to account for the presence of comorbid cardiovascular risk factors, which we observed to account for some proportion of elevated risk in adults with diabetes as compared with those who had coronary heart disease.

Strengths and Limitations

Our findings are based on a large sample of community-dwelling older adults whose health and cardiovascular disease status was well characterized at baseline. Prevalent diabetes at baseline was determined based on measured fasting glucose and medication inventory at the baseline, which decreases the misclassification compared with self-reporting of medication use.17 However, we did rely on a single elevated fasting glucose to define diabetes, which may misclassify participants who had a randomly high fasting glucose on a given day. Because our entire cohort did not have an oral glucose tolerance test at baseline, we may have missed some cases of type 2 diabetes, particularly among those participants who had impaired fasting glucose at baseline (glucose>100 mg/dL). A validation study in the ARIC cohort demonstrated that nearly two-thirds of adults ages 57-73 who have IFG have either diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance based on 2-hour challenge values.27 If we misclassified some participants as having only coronary heart disease or neither coronary heart disease nor diabetes, mortality risk across groups would appear more similar, thus biasing our estimates towards the null.

Participants who may have developed incident non-fatal coronary heart disease or incident diabetes prior to our mortality outcomes were not censored or re-classified but were analyzed in their original disease status group. We chose not to update risk based on incident myocardial infarction or diabetes because incident disease falls along the causal pathway between their prevalent disease status and mortality. Such an analysis addresses an important question; however, non-fatal myocardial infarction was not validated in our cohort so we cannot carry out that analyses.

Prevalent coronary heart disease was rigorously defined and all self-reports were verified by medical records and baseline ECGs in an attempt to correct for under- and over-reporting.16 Similarly, incident mortality outcomes were prospectively ascertained and validated with low loss to follow-up. Standardized assessment of other risk factors allowed evaluation of the contribution of concomitant risk factors on the mortality comparison between our two groups of interest. Conversely, we were unable to determine the duration of diabetes or coronary heart disease at baseline, which may have resulted in variation in disease severity that could not be controlled for in multivariable analysis that adjusted for other cardiovascular disease risk factors. While we could have determined incident diabetes during the follow-up period, we were unable to capture incident non-fatal coronary heart disease because the CHS cohort did not validate recurrent non-fatal events in individuals with prevalent coronary heart disease at baseline. To present a comparable analysis, we restricted our comparisons to prevalent diabetes and coronary heart disease at baseline. Because non-fatal cardiovascular events were not validated, our analysis was restricted to fatal cardiovascular disease. Thus, our findings cannot be extended to cardiovascular morbidity.

Conclusions

Diabetes in older adults confers substantial mortality from cardiovascular causes at a rate that is similar to existing coronary heart disease. The public health burden of both prevalent conditions is substantial in older adults—with relatively equal contributions from prevalent diabetes and prevalent coronary heart disease in women. Thus, current recommendations to intensively treat elevated cholesterol and blood pressure in persons with diabetes8, 9 are warranted, and may be particularly important in older adults.

Acknowledgments

The research reported in this article was supported by contract numbers N01-HC-85079 through N01-HC-85086, N01-HC-35129, N01 HC-15103, N01 HC-55222, N01-HC-75150, N01-HC-45133, grant number U01 HL080295 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, with additional contribution from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. A full list of principal CHS investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.chs-nhlbi.org/pi.htm.

Footnotes

Author statement: None of the authors has any conflicts of interest to report. All authors had access to the data and contributed to the drafting the manuscript.

The abstract was presented at the 67th Annual American Diabetes Association Scientific Sessions in Chicago, IL 2007

References

- 1.Haffner SM. Epidemiology of insulin resistance and its relation to coronary artery disease. American Journal of Cardiology. 1999;84(1A):11J–14J. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00351-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Juutilainen A, Lehto S, Ronnemaa T, Pyorala K, Laakso M. Type 2 diabetes as a “coronary heart disease equivalent”: an 18-year prospective population-based study in Finnish subjects. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(12):2901–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.12.2901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lotufo PA, Gaziano JM, Chae CU, et al. Diabetes and all-cause and coronary heart disease mortality among US male physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(2):242–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.2.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whiteley L, Padmanabhan S, Hole D, Isles C. Should diabetes be considered a coronary heart disease risk equivalent?: results from 25 years of follow-up in the Renfrew and Paisley survey. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(7):1588–93. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.7.1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schramm TK, Gislason GH, Kober L, et al. Diabetes patients requiring glucose-lowering therapy and nondiabetics with a prior myocardial infarction carry the same cardiovascular risk: a population study of 3.3 million people. Circulation. 2008;117(15):1945–54. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.720847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haffner SM, Lehto S, Ronnemaa T, Pyorala K, Laakso M. Mortality from coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in nondiabetic subjects with and without prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(4):229–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807233390404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fagot-Campagna A, Saaddine JB, Flegal KM, Beckles GLA. Diabetes, Impaired Fasting Glucose, and Elevated HbA1c in U.S. Adolescents: The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(5):834–837. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Standards of medical care in diabetes--2009. Diabetes Care. 2009;32 1:S13–61. doi: 10.2337/dc09-S013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Circulation. 2004;110(2):227–39. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133317.49796.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qato DM, Alexander GC, Conti RM, Johnson M, Schumm P, Lindau ST. Use of Prescription and Over-the-counter Medications and Dietary Supplements Among Older Adults in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300(24):2867–2878. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuller L, Borhani N, Furberg C, et al. Prevalence of subclinical atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease and association with risk factors in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;139(12):1164–79. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuller L, Fisher L, McClelland R, et al. Differences in prevalence of and risk factors for subclinical vascular disease among black and white participants in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18(2):283–93. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.2.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rockhill B, Newman B, Weinberg C. Use and misuse of population attributable fractions. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(1):15–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P, et al. The Cardiovascular Health Study: design and rationale. Ann Epidemiol. 1991;1(3):263–76. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(91)90005-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tell GS, Fried LP, Hermanson B, Manolio TA, Newman AB, Borhani NO. Recruitment of adults 65 years and older as participants in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1993;3(4):358–66. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(93)90062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Psaty BM, Kuller LH, Bild D, et al. Methods of assessing prevalent cardiovascular disease in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5(4):270–7. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(94)00092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Psaty BM, Lee M, Savage PJ, Rutan GH, German PS, Lyles M. Assessing the use of medications in the elderly: methods and initial experience in the Cardiovascular Health Study. The Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):683–92. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90143-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cushman M, Cornell ES, Howard PR, Bovill EG, Tracy RP. Laboratory methods and quality assurance in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Clin Chem. 1995;41(2):264–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stevens LA, Coresh J, Schmid CH, et al. Estimating GFR using serum cystatin C alone and in combination with serum creatinine: a pooled analysis of 3,418 individuals with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51(3):395–406. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans JM, Wang J, Morris AD. Comparison of cardiovascular risk between patients with type 2 diabetes and those who had had a myocardial infarction: cross sectional and cohort studies. Bmj. 2002;324(7343):939–42. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7343.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee CD, Folsom AR, Pankow JS, Brancati FL For the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study Investigators. Cardiovascular Events in Diabetic and Nondiabetic Adults With or Without History of Myocardial Infarction. Circulation. 2004;109(7):855–860. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000116389.61864.DE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Efron B, Tibshirani R. An introduction to the bootstrap. London, New York: Chapman & Hall Ltd.; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kronmal RA, Barzilay JI, Smith NL, et al. Mortality in pharmacologically treated older adults with diabetes: the Cardiovascular Health Study, 1989-2001. PLoS Med. 2006;3(10):e400. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanaya AM, Grady D, Barrett-Connor E. Explaining the Sex Difference in Coronary Heart Disease Mortality Among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002;162:1737–1745. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.15.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Marco R, Locatelli F, Zoppini G, Verlato G, Bonora E, Muggeo M. Cause-specific mortality in type 2 diabetes. The Verona Diabetes Study Diabetes Care. 1999;22(5):756–761. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.5.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gu K, Cowie CC, Harris MI. Mortality in adults with and without diabetes in a national cohort of the U.S. population, 1971-1993. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(7):1138–1145. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.7.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmidt MI, Duncan BB, Vigo A, et al. Detection of Undiagnosed Diabetes and Other Hyperglycemia States: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(5):1338–1343. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.5.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]