Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate, in extremely low gestational age newborns (ELGANs), relationships between indicators of early postnatal hypotension and cranial ultrasound indicators of cerebral white matter damage imaged in the nursery and cerebral palsy diagnoses at 24 month follow-up.

Methods

The 1041 infants in this prospective study were born at < 28 weeks gestation, were assessed for 3 indicators of hypotension in the first 24 postnatal hours, had at least one set of protocol cranial ultrasound scans, and were evaluated with a structured neurologic exam at 24 months corrected age. Indicators of hypotension included: 1) lowest mean arterial pressure (MAP) in the lowest quartile for gestational age; 2) treatment with a vasopressor; and 3) blood pressure lability, defined as the upper quartile of the difference between each infant’s lowest and highest MAP. Outcomes included indicators of cerebral white matter damage, i.e. moderate/severe ventriculomegaly or an echolucent lesion on cranial ultrasound, and cerebral palsy diagnoses at 24 months gestation. Logistic regression was used to evaluate relationships among hypotension indicators and outcomes, adjusting for potential confounders.

Results

Twenty-one percent of surviving infants had a lowest blood pressure in the lowest quartile for gestational age, 24% were treated with vasopressors, and 24% had labile blood pressure. Among infants with these hypotension indicators, 10% percent developed ventriculomegaly and 7% developed an echolucent lesion. At 24-months follow-up, 6% had developed quadriparesis, 4% diparesis, and 2% hemiparesis. After adjusting for confounders, we found no association between indicators of hypotension, and indicators of cerebral white matter damage or a cerebral palsy diagnosis.

Conclusions

The absence of an association between indicators of hypotension and cerebral white matter damage and or cerebral palsy suggests that early hypotension may not be important in the pathogenesis of brain injury in ELGANs.

Keywords: hypotension, mean arterial blood pressure, cranial ultrasound, ventriculomegaly, echolucent lesion, cerebral palsy, extremely preterm infants

Introduction

In a multi-center study, we found that more than 80% of extremely low gestational age newborns (ELGANs) were given some treatment to increase blood pressure,1 perhaps because it has been posited that hypotension causes brain damage in preterm newborns.2 One indicator of brain damage, cranial ultrasound abnormalities, has been associated with systemic hypotension in several studies. 3–9 However, the majority of published studies found no such association.10–22 Conflicting results have also been obtained from studies of the association between hypotension and cerebral palsy.22–25 Moreover, there appears to be uncertainty about whether treatments for hypotension in preterm newborns are beneficial or harmful.9, 21 In summary, the literature is unclear about the relationship between systemic hypotension, its treatment, and brain damage in preterm newborns.

The ELGAN Study provided the opportunity to evaluate relationships between three indicators of hypotension during the first 24 postnatal hours, cranial ultrasound lesions observed during initial hospitalization, and a cerebral palsy diagnosis 24 months later.

Methods

The ELGAN Study was designed to identify characteristics and exposures that increase the risk of structural and functional neurological disorders in ELGANs (Extremely Low Gestational Age Newborns).26 During the years 2002–2004, women whose babies were delivered before 28 weeks gestation at one of 14 participating institutions were asked to enroll in the study. The project was overseen by the National Institutes of Health, the institutional review boards of the 14 participating institutions, and an external Performance Monitoring and Safety Board (members appointed by the National Institutes of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke) at Children’s Hospital Boston. All variables and outcomes were defined prospectively. The original ELGAN Study included training for research personnel prior to the start of the study, and multiple training sessions were held to ensure consistent approaches to data collection. As such, this is a secondary analysis of prospectively acquired data from the original sample of 1506 infants, born in 14 level III neonatal intensive care units in the United States.

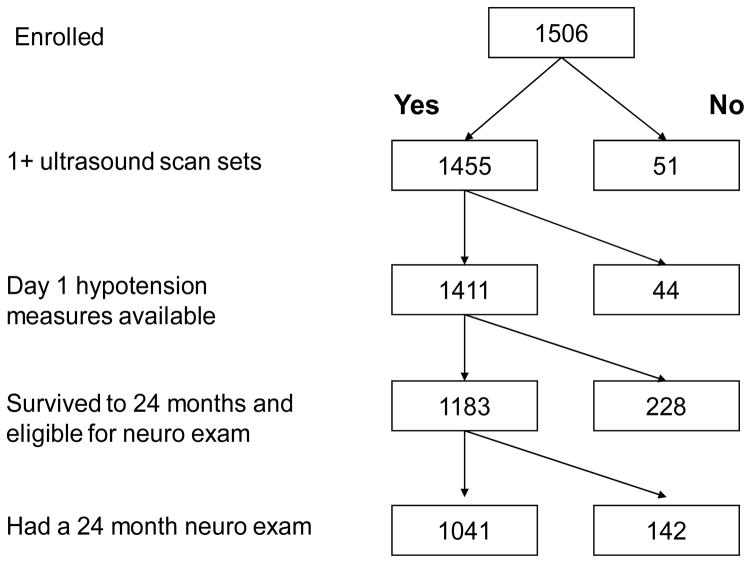

The sample of 1041 infants who are the subjects of this analysis had all three day-1 hypotension measures, one or more protocol ultrasound sets, and a neurologic exam at 24 months corrected age (Figure 1). To assess bias, we compared characteristics of the infants who returned for a developmental assessment to those of the 142 infants who were eligible but did not return. Infants who returned for 24 month follow-up tended to be born later in gestation but were more likely to have one of the indicators of hypotension.

Figure 1.

Sample for analyses of hypotension indicators and ultrasound lesions and cerebral palsy

Demographic, pregnancy and delivery variables

The clinical circumstances that led to each maternal admission and ultimately to each preterm delivery were operationally defined using data from a structured maternal interview and data abstracted from the medical record.27 Characteristics and exposures which were evaluated as potential confounders are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Maternal characteristics, indicators of hypotension, and indicators of white matter damage and cerebral palsy diagnoses (row percents).

| Characteristics of the mother | Hypotension indicators | Indicators of white matter damage | Cerebral palsy | N | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Q§ | Vaso¶ | Labile† | VM | EL | Q | D | H | |||

| Years of education | < 12 | 25 | 23 | 22 | 11 | 8 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 161 |

| 12 (HS) | 21 | 21 | 25 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 267 | |

| >12 to <16 | 19 | 21 | 27 | 14 | 10 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 240 | |

| College grad | 19 | 26 | 23 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 187 | |

| > 16 | 22 | 33 | 21 | 11 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 152 | |

| Married | Yes | 19 | 25 | 22 | 11 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 609 |

| No | 23 | 23 | 27 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 432 | |

| Black race | Yes | 26 | 25 | 30 | 11 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 278 |

| No | 19 | 24 | 21 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 747 | |

| Public insurance | Yes | 23 | 22 | 29 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 397 |

| No | 19 | 25 | 21 | 11 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 624 | |

| Primigravida | Yes | 22 | 27 | 21 | 10 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 410 |

| No | 20 | 22 | 26 | 11 | 8 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 605 | |

| Multi-fetal gestation | Yes | 20 | 30 | 19 | 11 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 354 |

| No | 21 | 21 | 26 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 687 | |

| Pre- pregnancy BMI | < 18.5 | 21 | 22 | 28 | 9 | 7 | 9 | 4 | 0 | 76 |

| 18.5, <25 | 19 | 24 | 23 | 11 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 506 | |

| 25, <30 | 23 | 26 | 26 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 207 | |

| ≥ 30 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 13 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 211 | |

| Vaginitis | Yes | 20 | 21 | 29 | 13 | 8 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 143 |

| No | 21 | 24 | 23 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 870 | |

| Aspirin | Yes | 21 | 30 | 23 | 18 | 14 | 19 | 2 | 0 | 57 |

| No | 21 | 23 | 24 | 10 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 953 | |

| Pregnancy complication | PTL | 20 | 25 | 22 | 13 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 464 |

| pPROM | 21 | 23 | 23 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 230 | |

| Preeclampsia | 18 | 18 | 26 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 137 | |

| Abruption | 25 | 24 | 32 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 113 | |

| Cx insuffcncy | 23 | 35 | 22 | 9 | 7 | 15 | 5 | 0 | 55 | |

| Fetal Indicatn | 19 | 21 | 18 | 10 | 12 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 42 | |

| Mod/severe chorioamnionitis | Yes | 19 | 20 | 23 | 12 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 343 |

| No | 22 | 26 | 24 | 10 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 606 | |

| Antenatal steroids | Yes | 21 | 26 | 24 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 672 |

| No | 15 | 20 | 24 | 10 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 255 | |

| Magnesium | No | 31 | 24 | 24 | 19 | 11 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 112 |

| Tocolysis | 20 | 27 | 22 | 9 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 562 | |

| Sz prophylax | 21 | 18 | 28 | 6 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 133 | |

| Max number of infants | 216 | 252 | 247 | 105 | 73 | 64 | 37 | 19 | 1041 | |

| Row percent | 21 | 24 | 24 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 2 | ||

Low Q: lowest MAP recorded in the first 24 hours, in the lowest quartile for gestational age

Vaso: treatment for hypotension with a vasopressor in the first 24 hours with any vasopressor (dopamine, dobutamine, and epinephrine)

Labile: labile blood pressure, defined as the upper quartile of the difference in the lowest and highest MAP

VM= Moderate/Severe ventriculomegaly; EL=Echolucenct lesion

Q= Quadriparesis; D= Diparesis; H=Hemiparesis

PTL=Preterm labor; pPROM=Preterm premature rupture of fetal membranes

Newborn variables

Gestational age estimates were based on a hierarchy of the quality of available information. Most desirable were estimates based on the dates of embryo retrieval, intrauterine insemination or fetal ultrasound before the 14th week (62%). When these were not available, reliance was placed sequentially on a fetal ultrasound at 14 or more weeks (29%), date of the last menstrual period without fetal ultrasound (7%), and gestational age recorded in the log of the neonatal intensive care unit (1%). The birth weight Z-score and head circumference Z-score represent the number of standard deviations the infant’s weight or head circumference are above or below the mean of infants at the same gestational age in a standard data set.28

Hypotension indicators

The ELGAN Study recorded three mean arterial blood pressures--the lowest, highest, and mode (most common)--during the first 24 postnatal hours. Because no single definition of hypotension is widely accepted,1, 20 we examined three indicators of hypotension: 1) lowest mean arterial pressure (MAP) in the lowest quartile for gestational age (23–24, 25–26, and 27 weeks); 2) treatment for hypotension with a vasopressor (dopamine, dobutamine, or epinephrine); and 3) blood pressure lability, defined as the upper quartile of the difference between the lowest and highest MAP.

The first definition of hypotension, “lowest MAP in the lowest quartile for gestational age” is based on the distribution of the lowest recorded MAPs in the sample. The second definition, “vasopressor treatment”, is an operational definition that derives from the assumption that hypotension was important enough to treat, regardless of how the clinician arrived at that decision. The third definition, “blood pressure lability”, makes use of the lowest and highest blood pressures in the sample, and reflects the portion of the sample with the greatest variability in recorded MAPs.

Clinicians and researchers frequently use MAP (in mmHg) less than gestational age (in weeks) as a definition for hypotension.20, 29 Using that definition, approximately two-thirds of infants in this cohort were “hypotensive” making it difficult to evaluate its potential impact. Similarly, since 75% of the cohort received volume expansion in the first 24 postnatal hours, volume expansion was not used as an indicator of hypotension in this study.

We did not specify a priori the method for measuring blood pressure (oscillometry or intra-arterial catheter) or a frequency with which pressures were to be recorded and research personnel who abstracted data were unaware of the method.

Cranial ultrasound evaluation

In this sample of ELGANs, moderate/severe ventriculomegaly and an echolucent lesion were better predictors of cerebral palsy and developmental delay than echodensity.30, 31 In addition, the inter-reader agreement was higher for moderate/severe ventriculomegaly and an echolucent lesion than for echodensity.30 Therefore, we chose moderate/severe ventriculomegaly and an echolucent lesion as indicators of white matter damage; hereafter, all references to “indicators of white matter damage” indicate moderate/severe ventriculomegaly and/or an echolucent lesion on postnatal ultrasound.

The three sets of protocol scans were defined by the postnatal day on which they were obtained. Protocol 1 scans were obtained between the first and fourth day (N=784), protocol 2 scans were obtained between the fifth and fourteenth day (N=973), and protocol 3 scans were obtained between the fifteenth day and the 40th week (N=1011). Seven hundred eleven infants in this sample of 1041 had all three sets of ultrasound studies.

Details about the methods for obtaining ultrasound scans, efforts to minimize observer variability, and strategies aimed at achieving concordance in the reading of the ultrasound scans are described elsewhere.32 All ultrasound scans were read by two independent sonologists who were not provided clinical information. When the two readers differed in their recognition of moderate/severe ventriculomegaly or an echolucent lesion, the films were sent to a third (tie-breaking) reader who was unaware of the first two sonologists reports.

Neurologic assessment

A developmental assessment was offered to all survivors at 24 months corrected gestational age. Of the study participants alive at 24 months, 88% were evaluated with a neurologic exam. The developmental assessment included a 31-item structured neurologic examination administered by staff who were trained and certified using a multi-media training video.33 Due to the low frequency of non-spastic cerebral palsy in infants less than 2 years of age, we focused on the spastic forms of cerebral palsy (quadriparesis, diparesis, or hemiparesis) using a previously published algorithm.34 The referenced algorithm includes monoparesis under the classification hemiparesis, and triparesis under the classification quadriparesis.

Data analysis

We evaluated the null hypothesis that infants with an indicator of hypotension during the first 24 postnatal hours were no more likely than their peers to have an indicator of white matter damage or a cerebral palsy diagnosis.

To identify potential confounders, we compared the distribution of characteristics and exposures among children who had each hypotension indicator to the distribution among those who did not. We then compared the distribution of these characteristics and exposures among children who did and did not have each of the outcomes.

Characteristics and exposures of the pregnancy, delivery, and postnatal period were treated as potential confounders if they had been considered potential confounders previously, or were associated in this dataset with both the exposure (a hypotension indicator) and the outcome (a cranial ultrasound lesion or cerebral palsy diagnosis) with a p-value ≤ 0.25. The only exception to the foregoing was that we did not treat SNAP-II (Score for Neonatal Acute Physiology-II) as a potential confounder because lowest MAP in the first 12 hours is a component of SNAP-II.35 We fit 15 separate multivariate logistic regression models, one for each of the five outcomes with each of the three hypotension indicators. In order to study the most homogeneous outcomes, we compared children with each CP diagnosis to those without CP. Each model included a hospital strata term to account for the possibility that infants born at a particular hospital were more like each other than like infants born at other hospitals. We describe the strength of the association between indicators of hypotension and indicators of white matter damage and cerebral palsy diagnosis, by calculating odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), adjusting for confounders.

Results

For the parent study sample of 1506 infants, hypotension measures and cranial ultrasound scans were available for 1411 (94%). At 24 months adjusted age, 1183 (84%) of these infants were alive, and 1041 (88%) of these were evaluated with the structured neurologic exam (Figure 1). To evaluate whether there was bias due to the exclusion of the 142 infants lost to follow-up, we compared characteristics of mothers and infants who returned for a developmental assessment to those of mothers and infants who were eligible but did not return. Infants who returned for 24 month follow-up tended to be born to mothers with at least a college education, and were more likely to have a hypotension indicator (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of mothers and children who survived to 24 months adjusted age, comparing those included in this study and those not included (column percents).

| Maternal or infant characteristic | Included in study | Not included | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal education | College or more | 34 | 22 |

| HMO/private insurance | Yes | 62 | 54 |

| 10+ prenatal care visits | Yes | 30 | 27 |

| Conception assistance | Yes | 22 | 17 |

| White race | Yes | 59 | 54 |

| Antenatal corticosteroid | Complete course | 65 | 57 |

| Partial Course | 25 | 35 | |

| None | 11 | 7 | |

| Cesarean delivery | Yes | 66 | 65 |

| Sex | Male | 52 | 52 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 23–24 | 20 | 23 |

| 25–26 | 46 | 47 | |

| 27 | 34 | 30 | |

| Birth weight (grams) | ≤ 750 | 37 | 37 |

| 751–1000 | 44 | 38 | |

| > 1000 | 19 | 25 | |

| Ventriculomegaly | Yes | 10 | 8 |

| Echolucent lesion | Yes | 7 | 5 |

| Lowest quartile MAP | Yes | 21 | 15 |

| Vasopressor | Yes | 24 | 21 |

| Labile MAP | Yes | 24 | 18 |

| Maximum number of infants | 1041 | 142 |

Lowest quartile MAP: lowest MAP recorded in the first 24 hours, in the lowest quartile for gestational age

Vasopressor: treatment for hypotension in the first 24 hours, using any vasopressor (dopamine, dobutamine, epinephrine)

Labile MAP: labile blood pressure, defined as the upper quartile of the difference between the lowest and highest MAP

While the frequency of lowest blood pressure in the lowest quartile was 25% for the entire cohort, it was only 21% in the cohort for these analyses. Twenty-four percent were treated with vasopressor, and 24% had labile blood pressure. In the NICU, 10% developed moderate/severe ventriculomegaly and 7% developed an echolucent lesion. At 24-months, 6% had developed quadriparesis, 4% diparesis, and 2% hemiparesis.

Social, demographic, and pregnancy characteristics (Table 2)

We created Tables 1 and 2 to examine potential confounders of relationships between indicators of hypotension and indicators of cerebral white matter damage and cerebral palsy diagnoses. Black race and public insurance were associated with a slightly higher rate of blood pressure lability, but infants whose mother had these characteristics were no more likely than their peers to develop cranial ultrasound lesions or a cerebral palsy diagnosis. Infants of multi-fetal gestation were more likely singletons to receive vasopressors, but were no more likely than their peers to develop one of the outcomes of interest. Maternal vaginitis was associated with blood pressure lability and with both ventriculomegaly and quadriplegia. Similarly, infants whose mothers used aspirin were more likely to have received vasopressors and more likely to develop ventriculomegaly, an echolucent lesion, and quadriplegia. However, these associations were based only on 57 women-infant dyads exposed to antenatal aspirin. Infants exposed antenatally to magnesium had lower risks of blood pressure in the lowest quartile for gestational age, and were less likely to develop ventriculomegaly, an echolucent lesion, quadriparesis, and hemiparesis.

Infant characteristics (Table 3)

Table 3.

Infant characteristics, indicators of hypotension, and indicators of white matter damage and cerebral palsy diagnosis (row percents).

| Characteristics of the infant | Hypotension indicator | Indicators of white matter damage | Cerebral palsy | N | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Q§ | Vaso¶ | Labile† | VM | EL | Q | D | H | |||

| Sex | Male | 21 | 26 | 25 | 12 | 8 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 544 |

| Female | 20 | 22 | 23 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 497 | |

| Type of gestation | Singleton | 21 | 21 | 26 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 690 |

| Multiple | 20 | 30 | 20 | 11 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 351 | |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 23–24 | 19 | 35 | 28 | 14 | 10 | 13 | 8 | 3 | 209 |

| 25–26 | 20 | 12 | 24 | 11 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 480 | |

| 27 | 24 | 20 | 21 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 352 | |

| Birth weight (grams) | ≤ 750 | 20 | 29 | 28 | 11 | 7 | 9 | 5 | 3 | 383 |

| 751–1000 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 8 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 458 | |

| ≥ 1000 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 13 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 200 | |

| BW Z-score* | < -2 | 25 | 21 | 32 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 56 |

| ≥ -2, < -1 | 20 | 24 | 29 | 11 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 141 | |

| ≥ -1 | 21 | 24 | 22 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 844 | |

| HC Z-score* | < - 2 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 82 |

| ≥ -2, < -1 | 21 | 21 | 24 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 234 | |

| ≥ -1 | 20 | 24 | 23 | 12 | 8 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 690 | |

| SNAP-II | < 20 | 13 | 16 | 21 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 536 |

| 20–39 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 10 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 256 | |

| ≥ 30 | 35 | 44 | 31 | 17 | 8 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 232 | |

| Max number of infants | 216 | 252 | 247 | 105 | 73 | 64 | 37 | 19 | 1041 | |

| Row percent | 21 | 24 | 24 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 2 | ||

Low Q: lowest MAP recorded in the first 24 hours, in the lowest quartile for gestational age

Vaso: treatment for hypotension with a vasopressor in the first 24 hours with any vasopressor (dopamine, dobutamine, and epinephrine)

Labile: labile blood pressure, defined as the upper quartile of the difference in the lowest and highest MAP

VM=Moderate/Severe ventriculomegaly; EL=Echolucenct lesion

Q=Quadriparesis; D= Diparesis; H=Hemiparesis

SNAP-II=Score for Neonatal Acute Physiology II

Infants of low gestational age were more likely than their gestationally-older peers to receive vasopressors and to have labile blood pressure, and were slightly more likely to develop ventriculomegaly, an echolucent lesion, or a cerebral palsy diagnosis. A birth weight Z-score < -1 was associated with both labile blood pressure and hemiparesis.

Univariate relationships among hypotension indicators, indicators of white matter damage and cerebral palsy diagnoses. (Table 4)

Table 4.

Frequencies of indicators of hypotension, and indicators of white matter damage and cerebral palsy diagnosis (row percents).

| Exposures & outcomes | Lowest Q§ | Vaso- pressor¶ | Labile MAP† | Ultrasound | Cerebral palsy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VM | EL | Q | D | H | N | |||||

| Lowest Q§ | Yes | 44 | 42 | 13 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 216 | |

| No | 19 | 19 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 825 | ||

| Vasopressor¶ | Yes | 38 | 30 | 12 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 252 | |

| No | 15 | 22 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 789 | ||

| Labile MAP† | Yes | 37 | 31 | 10 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 247 | |

| No | 16 | 22 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 794 | ||

| Ventriculo-megaly | Yes | 26 | 29 | 23 | 28 | 28 | 9 | 9 | 105 | |

| No | 20 | 24 | 24 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 936 | ||

| Echolucent lesion | Yes | 18 | 22 | 25 | 40 | 33 | 7 | 12 | 73 | |

| No | 21 | 24 | 24 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 968 | ||

| Quadriparesis | Yes | 22 | 23 | 27 | 44 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 64 | |

| No | 21 | 24 | 24 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 977 | ||

| Diparesis | Yes | 19 | 24 | 22 | 24 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 37 | |

| No | 21 | 24 | 24 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 1004 | ||

| Hemiparesis | Yes | 26 | 26 | 16 | 47 | 47 | 0 | 0 | 19 | |

| No | 21 | 24 | 24 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 1022 | ||

| Maximum N | 216 | 252 | 247 | 105 | 73 | 64 | 37 | 19 | 1041 | |

| Row percent | 21 | 24 | 24 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 2 | ||

Low Q: lowest MAP recorded in the first 24 hours, in the lowest quartile for gestational age

Vaso: treatment for hypotension with a vasopressor in the first 24 hours with any vasopressor (dopamine, dobutamine, and epinephrine)

Labile: labile blood pressure, defined as the upper quartile of the difference in the lowest and highest MAP

VM= Moderate/Severe ventriculomegaly; EL=Echolucenct lesion

Q= Quadriparesis; D= Diparesis; H=Hemiparesis

The indicators of hypotension are highly related. Among children with a lowest blood pressure in the lowest quartile for gestation, 44% received a vasopressor, and 42% had labile blood pressure. In contrast, among those who did not have a blood pressure in the lowest quartile for gestational age, only 19% received a vasopressor and 19% had labile blood pressure.

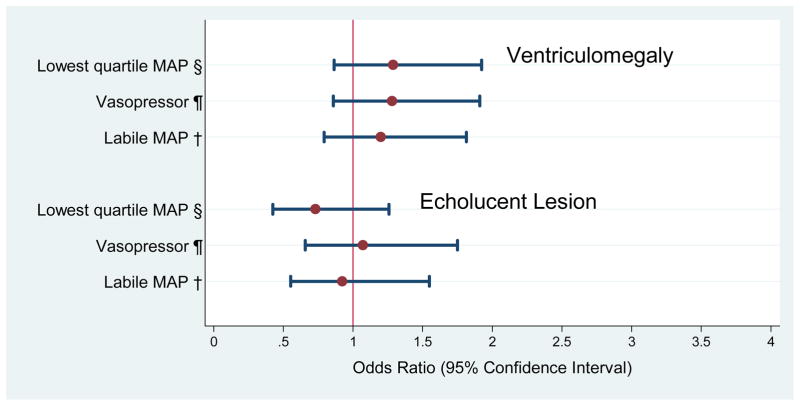

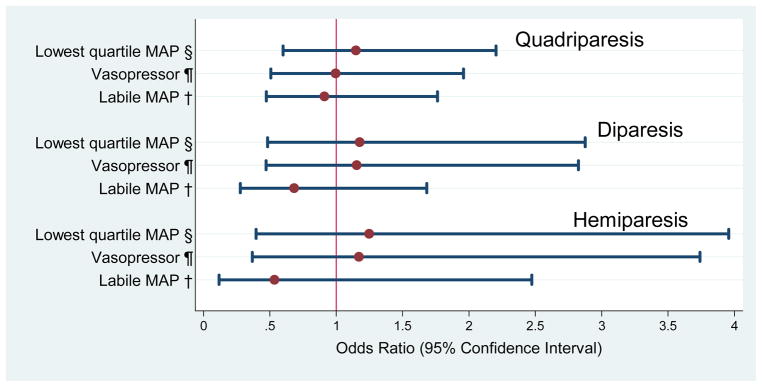

Multivariate relationship (Figures 2 and 3)

Figure 2.

Odds ratios (and 95% confidence intervals) of the risk of indicators of white matter damage obtained with logistic regression models that incorporate indicators of hypotension during the first 24 postnatal hours and potential confounders.*

*Adjustment is made for black race, public insurance, primagravida, male sex, gestational age 23–24 weeks, birth weight Z-score < -1, multi-fetal gestation, delivery for preeclampsia or fetal indication and receipt of magnesium. A hospital strata term is included to account for the possibility that infants born at a particular hospital are more like each other than like infants born at other hospitals.

§Low Q: lowest MAP recorded in the first 24 hours in the lowest quartile for gestational age

¶Vaso: treatment for hypotension with a vasopressor in the first 24 hours with any vasopressor (dopamine, dobutamine, and epinephrine)

†Labile: labile blood pressure, defined as the upper quartile of the difference in the lowest and highest MAP

Figure 3.

Odds ratios (and 95% confidence intervals) of the risk of cerebral palsy types obtained with logistic regression models that incorporate indicators of hypotension during the first 24 postnatal hours and potential confounders.*

*Adjustment is made for black race, public insurance, primagravida, male sex, gestational age 23–24 weeks, birth weight Z-score < -1, multi-fetal gestation, delivery for preeclampsia or fetal indication and receipt of magnesium. A hospital strata term is included to account for the possibility that infants born at a particular hospital are more like each other than like infants born at other hospitals.

§Low Q: lowest MAP recorded in the first 24 hours in the lowest quartile for gestational age

¶Vaso: treatment for hypotension with a vasopressor in the first 24 hours with any vasopressor (dopamine, dobutamine, and epinephrine)

†Labile: labile blood pressure, defined as the upper quartile of the difference in the lowest and highest MAP

Univariate analyses (Tables 2 and 3) identified black race, public insurance, primigravida, male sex, gestational age 23–24 weeks, birthweight Z-score < -1, multi-fetal pregnancy, delivery for preeclampsia or fetal indication, receipt of magnesium, and SNAP-II, as potential confounders. After adjusting for confounders, we found no association between any of the three indicators of hypotension and the two indicators of white matter damage (figure 2) or any of three cerebral palsy diagnoses (figure 3). SNAP-II was not included in multivariate analyses for the reasons cited in the Data analysis section.

Discussion

In a large sample of ELGANs, we found little evidence for an association between hypotension indicators and indicators of white matter damage or a cerebral palsy diagnosis. Our findings cast doubt on the concept that early postnatal hypotension, in isolation, causes brain damage in ELGANs. In addition, we did not find support for the notion that vasopressors benefit preterm neonates with early postnatal hypotension.36

Prior studies favoring an association between hypotension and brain ultrasound lesions3–9 had relatively small sample sizes, decreasing the likelihood that potential confounders could be adequately controlled. Most of the studies favoring an association between hypotension and cerebral palsy acquired data retrospectively, 9, 21, 23, 24 increasing the possibility of ascertainment bias, and the one prospective study with a design comparable to ours failed to demonstrate such an association.25 Our findings are in agreement with the majority of published studies, which found no convincing relationship between hypotension and brain ultrasound images10–22 or cerebral palsy.22, 25

The hypothesis that “early postnatal hypotension causes white matter damage in preterm infants” is predicated on two related concepts. The first is that cerebral white matter damage is a consequence of ischemia. The second is that ischemia results from systemic hypotension. Since the late 1970s, when Hans Lou published his historically important studies of preterm infants, in which early systemic hypotension was correlated with low cerebral blood flow and brain injury, neonatologists have been concerned about the adverse effects of early systemic hypotension on the fragile preterm brain.37, 38 Since that time, it has become increasingly clear that the etiology of brain damage in preterm newborns is multifactorial.15, 39, 40 Our study and others suggest that systemic hypotension, as an isolated clinical event, is an insufficient indicator of white matter damage in preterm newborns, and by extension, an insufficient indicator of cerebral ischemia.

We offer a number of possible explanations for why early postnatal hypotension might not increase the risk of white matter damage or cerebral palsy in extremely preterm infants. First, a relatively low blood pressure on the first day of life might be part of the normal physiologic transition from intrauterine to extrauterine life. Second, “hypotension”, as described here, might not lead to cerebral ischemia. Third, if “hypotension” does cause ischemia, then it does not occur with enough frequency or severity to be associated with white matter damage or cerebral palsy at 2 years. Fourth, if hypotension is associated with white matter damage, then our crude methods for obtaining blood pressure measurements are insufficient for clinical decision-making regarding cerebral perfusion.

Our study has several limitations. First, we did not pre-specify a protocol for measuring blood pressure; some measurements were obtained by intra-arterial catheters, while others were obtained by oscillometry. Overestimates of blood pressure, which frequently accompany the use of oscillometry, might have attenuated associations between hypotension indicators and ultrasound lesions or cerebral palsy.41, 42 Second, our findings may have been confounded by the frequent use of volume expansion. Any inferences from our findings should be limited to cohorts in which volume expansion is used frequently, as three-fourths of study infants were treated with volume expansion in the first 24 postnatal hours. Third, we might have failed to identify hypotension-related white matter damage because cranial ultrasound fails to detect some of the white matter damage that is later identified with magnetic resonance imaging.43

The strengths of our study include the prospective collection of data from a large multicenter cohort, defined by gestational age (rather than birth weight).44 This study derives from a large sample of ELGANs from several regions of the United States, increasing the validity and generalizability of our findings.45, 46 We assessed brain damage using both structural and functional outcomes that were assessed with a high degree of reliability, enhancing the validity of these assessments. In addition, the identification of ultrasound lesions required the agreement of two independent readers, decreasing the likelihood of inter-observer variability. Finally, follow up data were collected by examiners trained in the standardized administration of the neurologic exam, and these examiners were unaware of the child’s clinical history.33

Prior studies that provided evidence for an association between low blood pressure and white matter damage or cerebral palsy were smaller than ours, and less likely to adequately adjust for confounders. This underscores the importance of our findings, as prior “positive” studies, may have created a distorted perception of the strength of antecedent risks.45, 46 Thus, we support the recommendation of others, that randomized trials be used to evaluate the benefit of treatments to raise blood pressure in extremely preterm neonates.47 Perhaps the most important implication for clinicians is that our study and others fail to find support for the hypothesis that white matter damage is associated with low blood pressure in the early postnatal period.

In conclusion, in a cohort of preterm infants, the majority of whom were treated with volume expanders, we found little evidence for an association between early indicators of postnatal hypotension and two indicators of cerebral white matter damage and cerebral palsy diagnoses at 24 months corrected gestational age.

Abbreviations

- ELGAN

extremely low gestational age newborn

- IVH

intraventricular hemorrhage

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- CP

cerebral palsy

- CUS

cranial ultrasound

Participating institutions (site principal investigators, sonologists, and neuro-developmental examiners)

Baystate Medical Center, Springfield MA (Bhavesh Shah, Frederick Hampf, Herbert Gilmore, Susan McQuiston)

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston MA (Camilia R. Martin, Jane Share)

Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Boston MA (Linda J. Van Marter, Sara Durfee)

Children’s Hospital Boston, Boston MA (Alan Leviton, Kristen Ecklund, Samantha Butler, Haim Bassan, Adré Duplessis, Cecil Hahn, Omar Khwaha, AK Morgan, Janet S. Soul)

DeVos Children’s Hospital, Grand Rapids MI (Mariel Portenga, Bradford W. Betz, Steven L. Bezinque, Joseph Junewick, Wendy Burdo-Hartman, Lynn Fagerman, Kim Lohr, Steve Pastynrnak, Dinah Sutton)

Floating Hospital for Children at Tufts Medical Center, Boston MA (Cynthia Cole/John Fiascone, Roy McCauley, Paige T. Church, Cecelia Keller, Karen Miller)

Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston MA (Robert Insoft, Kalpathy Krishnamoorthy)

Michigan State Univeristy, E Lansing MI (Nigel Paneth)

North Carolina Children’s Hospital, Chapel Hill NC (Carl Bose, Lynn A. Fordham, Lisa Bostic, Janice Wereszczak, Diane Marshall, Kristi Milowic, Carol Hubbard)

Sparrow Hospital, Lansing MI (Padmani Karna, Ellen Cavenagh, Victoria J. Caine, Padmani Karna, Nicholas Olomu, Joan Price)

University of Chicago Hospital, Chicago IL (Michael D. Schreiber, Kate Feinstein, Leslie Caldarelli, Sunila E. O’Conno, Michael Msall, Susan Plesha-Troyke)

University Health Systems of Eastern Carolina, Greenville NC (Stephen Engelke, Ira Adler, Sharon Buckwald, Rebecca Helms, Kathyrn Kerkering, Scott S. MacGilvray, Peter Resnik)

U Mass Memorial Health Center, Worcester, MA (Francis Bednarek, Jacqueline Wellman, Robin Adair, Richard Bream, Alice Miller, Albert Scheiner, Christy Stine)

Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center and Forsyth Medical Center, Winston-Salem NC (T. Michael O’Shea, Barbara Specter, Deborah Allred, Don Goldstein, Gail Hounshell, Robert Dillard, Cherrie Heller, Debbie Hiatt, Lisa Washburn)

William Beaumont Hospital, Royal Oak MI (Daniel Batton, Chung-ho Chang, Karen Brooklier, Melisa Oca)

Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven CT (Richard Ehrenkranz, Cindy Miller, Nancy Close, Elaine Romano, Joanne Williams)

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

This study was supported by a cooperative agreement with the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (5U01NS040069-05) and a program project grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (5P30HD18655). There are no conflicts of interest, and no relationships that would in any way influence or bias this study.

Hypotension.BSID Bibliography

- 1.Laughon M, Bose C, Allred E, et al. Factors associated with treatment for hypotension in extremely low gestational age newborns during the first postnatal week. Pediatrics. 2007;119:273–80. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.du Plessis AJ. The role of systemic hemodynamic disturbances in prematurity-related brain injury. J Child Neurol. 2009;24:1127–40. doi: 10.1177/0883073809339361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weindling AM, Wilkinson AR, Cook J, et al. Perinatal events which precede periventricular haemorrhage and leukomalacia in the newborn. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1985;92:1218–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1985.tb04865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miall-Allen VM, de Vries LS, Whitelaw AG. Mean arterial blood pressure and neonatal cerebral lesions. Arch Dis Child. 1987;62:1068–9. doi: 10.1136/adc.62.10.1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watkins AM, West CR, Cooke RW. Blood pressure and cerebral haemorrhage and ischaemia in very low birthweight infants. Early Hum Dev. 1989;19:103–10. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(89)90120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fok TF, Davies DP, Ng HK. A study of periventricular haemorrhage, post-haemorrhagic ventricular dilatation and periventricular leucomalacia in chinese preterm infants. J Paediatr Child Health. 1990;26:271–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1990.tb01070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Low JA, Froese AB, Galbraith RS, et al. The association between preterm newborn hypotension and hypoxemia and outcome during the first year. Acta Paediatr. 1993;82:433–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1993.tb12717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Shea TM, Kothadia JM, Roberts DD, et al. Perinatal events and the risk of intraparenchymal echodensity in very-low-birthweight neonates. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1998;12:408–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.1998.00134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuint J, Barak M, Morag I, et al. Early treated hypotension and outcome in very low birth weight infants. Neonatology. 2008;95:311–316. doi: 10.1159/000180113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trounce JQ, Shaw DE, Levene MI, et al. Clinical risk factors and periventricular leucomalacia. Arch Dis Child. 1988;63:17–22. doi: 10.1136/adc.63.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Vries LS, Regev R, Dubowitz LM, et al. Perinatal risk factors for the development of extensive cystic leukomalacia. Am J Dis Child. 1988;142:732–5. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1988.02150070046023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bejar RF, Vaucher YE, Benirschke K, et al. Postnatal white matter necrosis in preterm infants. J Perinatol. 1992;12:3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gronlund JU, Korvenranta H, Kero P, et al. Elevated arterial blood pressure is associated with peri-intraventricular haemorrhage. Eur J Pediatr. 1994;153:836–41. doi: 10.1007/BF01972894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Souza SW, Janakova H, Minors D, et al. Blood pressure, heart rate, and skin temperature in preterm infants: Associations with periventricular haemorrhage. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1995;72:F162–7. doi: 10.1136/fn.72.3.f162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perlman JM, Risser R, Broyles RS. Bilateral cystic periventricular leukomalacia in the premature infant: Associated risk factors. Pediatrics. 1996;97:822–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiswell TE, Graziani LJ, Kornhauser MS, et al. Effects of hypocarbia on the development of cystic periventricular leukomalacia in premature infants treated with high-frequency jet ventilation. Pediatrics. 1996;98:918–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baud O, Ville Y, Zupan V, et al. Are neonatal brain lesions due to intrauterine infection related to mode of delivery? Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:121–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb09363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cunningham S, Symon AG, Elton RA, et al. Intra-arterial blood pressure reference ranges, death and morbidity in very low birthweight infants during the first seven days of life. Early Hum Dev. 1999;56:151–65. doi: 10.1016/s0378-3782(99)00038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dammann O, Allred EN, Kuban KC, et al. Systemic hypotension and white-matter damage in preterm infants. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2002;44:82–90. doi: 10.1017/s0012162201001724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Limperopoulos C, Bassan H, Kalish LA, et al. Current definitions of hypotension do not predict abnormal cranial ultrasound findings in preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2007;120:966–77. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Batton B, Zhu X, Fanaroff J, et al. Blood pressure, anti-hypotensive therapy, and neurodevelopment in extremely preterm infants. J Pediatr. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.09.017. First published online Nov 19 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pellicer A, del Carmen Bravo M, Madero R, et al. Early systemic hypotension and vasopressor support in low birth weight infants: Impact on neurodevelopment. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1369–76. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldstein RF, Thompson RJ, Jr, Oehler JM, et al. Influence of acidosis, hypoxemia, and hypotension on neurodevelopmental outcome in very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 1995;95:238–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy DJ, Hope PL, Johnson A. Neonatal risk factors for cerebral palsy in very preterm babies: Case-control study. BMJ. 1997;314:404–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7078.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hunt RW, Evans N, Rieger I, et al. Low superior vena cava flow and neurodevelopment at 3 years in very preterm infants. J Pediatr. 2004;145:588–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Shea TM, Allred EN, Dammann O, et al. The ELGAN study of the brain and related disorders in extremely low gestational age newborns. Early Hum Dev. 2009;85:719–25. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2009.08.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McElrath TF, Hecht JL, Dammann O, et al. Pregnancy disorders that lead to delivery before the 28th week of gestation: An epidemiologic approach to classification. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;27:27. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yudkin PL, Aboualfa M, Eyre JA, et al. New birthweight and head circumference centiles for gestational ages 24 to 42 weeks. Early Hum Dev. 1987;15:45–52. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(87)90099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dempsey EM, Barrington KJ. Diagnostic criteria and therapeutic interventions for the hypotensive very low birth weight infant. J Perinatol. 2006;26:677–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Shea TM, Kuban KC, Allred EN, et al. Neonatal cranial ultrasound lesions and developmental delays at 2 years of age among extremely low gestational age children. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e662–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuban KC, Allred EN, O’Shea TM, et al. Cranial ultrasound lesions in the NICU predict cerebral palsy at age 2 years in children born at extremely low gestational age. J Child Neurol. 2009;24:63–72. doi: 10.1177/0883073808321048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuban K, Adler I, Allred EN, et al. Observer variability assessing US scans of the preterm brain: The elgan study. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37:1201–8. doi: 10.1007/s00247-007-0605-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuban KC, O’Shea M, Allred E, et al. Video and CD-ROM as a training tool for performing neurologic examinations of 1-year-old children in a multicenter epidemiologic study. J Child Neurol. 2005;20:829–31. doi: 10.1177/08830738050200101001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuban KC, Allred EN, O’Shea M, et al. An algorithm for identifying and classifying cerebral palsy in young children. J Pediatr. 2008;153:466–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richardson DK, Corcoran JD, Escobar GJ, et al. SNAP-II and SNAPPE-II: Simplified newborn illness severity and mortality risk scores. J Pediatr. 2001;138:92–100. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.109608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dempsey EM, Barrington KJ. Evaluation and treatment of hypotension in the preterm infant. Clin Perinatol. 2009;36:75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lou HC, Lassen NA, Friis-Hansen B. Low cerebral blood flow in hypotensive perinatal distress. Acta Neurol Scand. 1977;56:343–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1977.tb01441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lou HC, Lassen NA, Friis-Hansen B. Impaired autoregulation of cerebral blood flow in the distressed newborn infant. J Pediatr. 1979;94:118–21. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(79)80373-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leviton A, Pagano M, Kuban KC, et al. The epidemiology of germinal matrix hemorrhage during the first half-day of life. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1991;33:138–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1991.tb05092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Collins MP, Lorenz JM, Jetton JR, et al. Hypocapnia and other ventilation-related risk factors for cerebral palsy in low birth weight infants. Pediatr Res. 2001;50:712–9. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200112000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Shea J, Dempsey EM. A comparison of blood pressure measurements in newborns. Am J Perinatol. 2009;26:113–6. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1091391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Troy R, Doron M, Laughon M, et al. Comparison of noninvasive and central arterial blood pressure measurements in elbw infants. J Perinatol. 2009;29:744–9. doi: 10.1038/jp.2009.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Inder TE, Anderson NJ, Spencer C, et al. White matter injury in the premature infant: A comparison between serial cranial sonographic and MR findings at term. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:805–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arnold CC, Kramer MS, Hobbs CA, et al. Very low birth weight: A problematic cohort for epidemiologic studies of very small or immature neonates. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134:604–13. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dickersin K. The existence of publication bias and risk factors for its occurrence. Jama. 1990;263:1385–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hall R, de Antueno C, Webber A. Publication bias in the medical literature: A review by a canadian research ethics board. Can J Anaesth. 2007;54:380–8. doi: 10.1007/BF03022661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dempsey EM, Barrington KJ. Treating hypotension in the preterm infant: When and with what: A critical and systematic review. J Perinatol. 2007;27:469–78. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]